Abstract

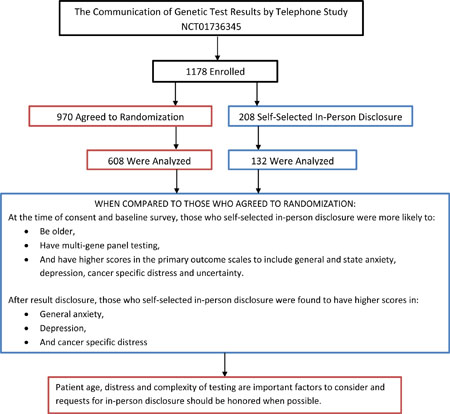

Telephone disclosure of cancer genetic test results is non-inferior to in-person disclosure. However, how patients who prefer in-person communication of results differ from those who agree to telephone disclosure is unclear but important when considering delivery models for genetic medicine. Patients undergoing cancer genetic testing were recruited to a multi-center, randomized, non-inferiority trial (NCT01736345) comparing telephone to in-person disclosure of genetic test results. We evaluated preferences for in-person disclosure, factors associated with this preference and outcomes compared to those who agreed to randomization. Among 1178 enrolled patients, 208 (18%) declined randomization, largely given a preference for in-person disclosure. These patients were more likely to be older (p=0.007) and to have had multi-gene panel testing (p<0.001). General anxiety (p=0.007), state anxiety (p=0.008), depression (p=0.011), cancer-specific distress (p=0.021) and uncertainty (p=0.03) were higher after pre-test counseling. After disclosure of results, they also had higher general anxiety (p=0.003), depression (p=0.002) and cancer-specific distress (p=0.043). While telephone disclosure is a reasonable alternative to in-person disclosure in most patients, some patients have a strong preference for in-person communication. Patient age, distress and complexity of testing are important factors to consider and requests for in-person disclosure should be honored when possible.

Keywords: genetic counseling, cancer genetic testing, result disclosure, telephone disclosure, in-person disclosure preference

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Germline genetic testing for disease predisposition has become standard practice in oncology and is increasingly utilized to identify patients at increased risk across an increasing range of medical disciplines.1–4 Professional societies have recommended that genetic testing be paired with pre- and post-test counseling to optimize informed consent, understanding of results, psychosocial responses and uptake of appropriate preventive behaviors.1,5 Given the complexity of genetic information and potential for false reassurance and psychosocial distress, genetic counseling has traditionally been delivered in-person.6–8

However, with the growing demand for genetic tests, telephone counseling has been increasingly utilized to reduce patient time and travel burdens and improve access to care.7,9–12 In a recent review of genetic counseling practices, telephone disclosure of results (e.g. post-test counseling) is the most common delivery model, and is also used often or exclusively by 8% of genetic counselors.7,13 Two randomized studies comparing telephone counseling to in-person delivery for BRCA1/2 testing both found telephone to be no worse than in-person counseling.14–16 Uptake of testing was lower in both studies among those who received pre-test counseling by telephone. In the more recent COGENT (Communication Of GENetic Test Results by Telephone) study, including a wider range of cancer genetic testing, including multi-gene panel testing, we also found that telephone disclosure was non-inferior to in-person disclosure of genetic test results for immediate post-disclosure outcomes.17

While these data suggest favorable outcomes with telephone disclosure, even in the era of multi-gene testing and even among subgroups with a positive or Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) result, 1–18% of individuals in these studies declined telephone communication. In the COGENT study, 18% declined randomization but remained on study, providing an opportunity to better understand these patients’ characteristics and if their outcomes differ from those willing to receive results by telephone. Here we evaluate factors associated with declining randomization given a preference for in person disclosure in the COGENT Study to better understand who might be negatively impacted by practice changes if telephone disclosure was used exclusively for communication of genetic test results. Second, we evaluate differences in change in cognitive, affective and behavioral outcomes among those who declined randomization given a preference for in-person disclosure as compared to those who were willing to receive results by telephone. We sought to determine if those selecting in-person disclosure represent a vulnerable population with the potential for inferior patient reported outcomes if telephone disclosure was widely adopted.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting and Participants

From December 2012 to October 2015, participants were recruited to the COGENT Study, a multi-center, randomized, non-inferiority trial (NCT01736345) comparing disclosure of genetic test results by telephone with a genetic counselor to usual care (in-person disclosure with a genetic counselor), followed by an opportunity to see a medical provider for medical management recommendations in both arms. Participants were recruited from the clinical cancer genetic programs at The University of Pennsylvania and The Fox Chase Cancer Center (Philadelphia, PA), The MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper (Camden, NJ) and The University of Chicago, and The John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital at Cook County (Chicago, IL). Eligible participants were English-speaking adults who had completed in-person pre-test counseling and were proceeding with cancer genetic testing for hereditary breast, gynecological and/or gastrointestinal cancer syndromes (May 2014).

The Institutional Review Board at all sites approved this study. Participants were recruited after their in-person pre-test counseling session and after the type of testing (Targeted v. Multi-Gene Panel) had been decided by the patient and genetic counselor. Eligible individuals were informed they could enroll and agree to be randomized (Telephone Arm or Standard of Care In-Person Arm) or they could decline randomization if they were not interested in receiving their results by telephone. After written informed consent, participants completed a baseline survey.

Genetic test disclosures were delivered by 22 board-certified genetic or nurse counselors. Standardized theoretically and stakeholder informed communication protocols and visual aids were utilized for all sessions.18,19 Telephone disclosure (TD) sessions were scheduled with a genetic counselor and all participants in the TD arm were recommended to return for a clinic visit with a site medical provider with expertise in cancer genetics to discuss medical management based on their test results. Usual care in-person disclosure (IPD) and self-select in-person disclosure (SSIPD): In-person disclosure sessions with a genetic counselor and medical provider were scheduled as per usual care. Medical management discussions with medical providers occurred during the same visit, after patients received their results with the genetic counselor, consistent with current usual care at all sites. Participants completed a post-disclosure survey (T1) within 7 days after their disclosure.

Outcomes

Outcomes were selected based on our theoretical model, which was informed by the Self-regulation Theory of Health Behavior including factors associated with communication preferences and the risks of telephone communication. These risks include increased distress, decreased understanding of results, and poorer behavioral outcomes.17,18,20

Knowledge of genetic disease was evaluated (T0 and T1) using an adapted 6 item Cancer Genetics Knowledge scale (Cronbach’s α=0.60–0.96)21, as previously described. Individuals undergoing multi-gene panel testing (MGPT) completed an additional 11 items evaluating the benefits, limitations and interpretation of MGPT, adapted from the ClinSeq scale and utilized in related research (Cronbach’s α = 0.57–0.61). 22

State anxiety was measured (T0 and T1) with the 20-item State Inventory of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory 23 (Cronbach’s α=0.96).

General anxiety was assessed (T0 and T1) with the 7-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.86–0.89).24

Cancer-specific distress was evaluated (T0 and T1) with 14 items of Impact of Events Scale (IES).25 We excluded one item lacking face validity in our population (Cronbach’s α=0.88–0.90).

Depression was assessed (T0 and T1) with the 7-item HADS depression subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.82–0.84).24

Uncertainty was assessed (T0 and T1) using a 3-item scale adapted from the Multi-dimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment Question (MICRA) (Cronbach’s α=0.80–0.84).26

Satisfaction with genetic services was measured (T0 and T1) with a 9-item scale evaluating participants’ perceptions of their genetic counseling and testing experience, including cognitive, affective and time/attention items27,18 (Cronbach’s α=0.74–0.81).

Behavioral intention (T0, T1) included behavioral intent for mammography, breast MRI, colonoscopy and prophylactic surgeries (mastectomy and oophorectomy), as applicable. Patients responded on a 7-item Likert scale and could mark not applicable.

Statistical Analysis

The study was designed as a non-inferiority trial, to conclude that TD is as good as, or better than IPD at T1 (post-disclosure) relative to pre-disclosure (i.e. change scores). Our study design and primary results have been described previously.17

For this study, we used t-tests and Fisher’s Exact tests to compare baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between groups defined by willingness to accept randomization. In order to examine multivariable characteristics associated with declining randomization (self-selection to in-person disclosure), we used a random-effects logistic regression of group status (agreed to randomization versus self-selected in-person disclosure) with the demographic and clinical characteristics entered as covariates. We included a random intercept for genetic counselor to account for correlated outcomes within counselor.

In order to compare psychosocial outcomes between groups, we used random-effects multiple linear regressions in which we entered group as an indicator covariate (agreed to randomization versus self-selected in-person disclosure) and controlled for the potential confounders of age and receipt of MGPT. We further included a random intercept to account for genetic counselor effects.

To account for missing data in the regression models, we used the multiple imputation methods of Raghunathan et. al. with 25 imputed datasets.28 The criteria for statistical significance was a p-value<0.05 (two-sided). Analyses were conducted using STATA/MP Version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We used the MI macros in STATA to appropriately combine estimates from the 25 imputed datasets. We evaluated whether findings would be statistically significant using a 20% False Discovery Rate with 36 comparisons for table 2 and 39 comparisons for table 3 (12 scales in table 2, for example, with two time period measurements and one change score measurement, 12*3=36).29

RESULTS

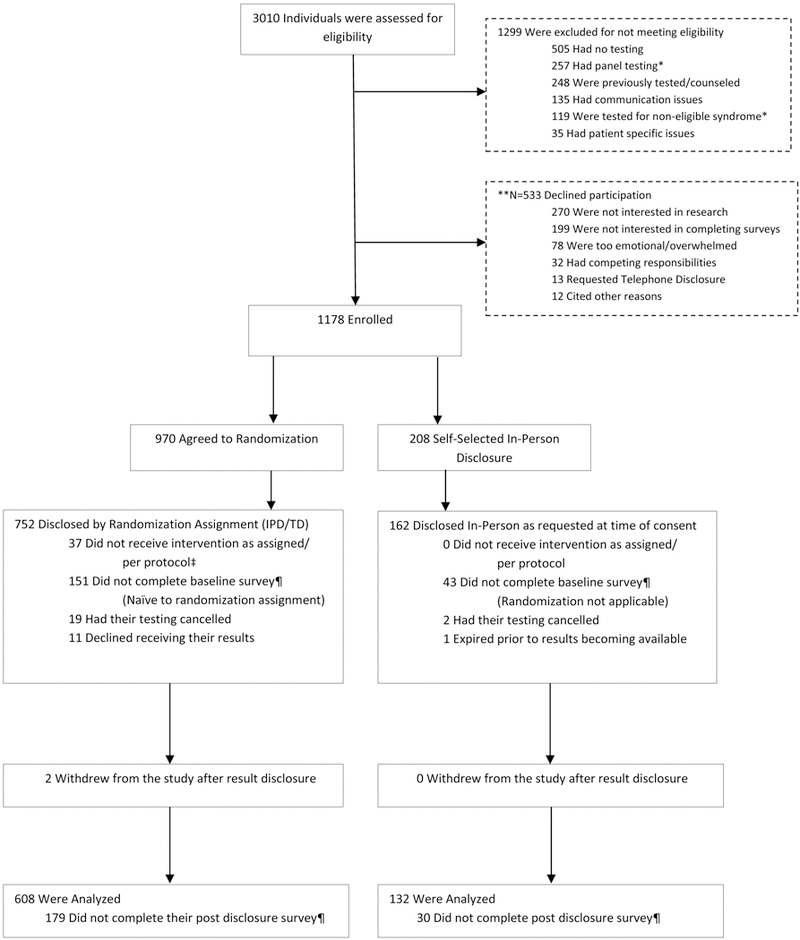

Enrollment, willingness to be randomized and survey completion data are shown in Figure 1. Of 1,178 (69%) consented to the study, 208 (18%) declined randomization. Among those who indicated why they declined randomization (n=126), the majority (82.5%) of participants reported declining given a preference for in-person disclosure or concerns about telephone disclosure. Twelve percent reported declining randomization because they wanted to have a physician or relative present, and only 5.5% declined randomization because they felt that they would have to return to clinic anyway to meet with a physician to discuss their results.

Figure 1 – Consort Diagram.

*Individuals approached prior to Non-BRCA 1/2 and Multigene Testing Adaptation

**Multiple reasons for decline were reported per participant

‡ Reflects individuals who were: disclosed by telephone at participant’s behest (N=31), disclosed by telephone due to illness/financial burden (N=3) and received results in-person with a Non-COGENT provider (N=3)

¶Survey not completed within 0–7 days

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in genetic test result between those who agreed to randomization and those who declined (62% uninformative negative, 13% positive, 9% VUS and 12% true negative among those randomized; 61% uninformative negative, 12% positive, 15% VUS and 11% true negative among those who declined randomization). The remainder had testing cancelled or elected to not receive results.

Table 1 –

Characteristics of participants who completed a baseline survey by willingness to receive results by phone

| Characteristic | Randomized – Willing to

Receive Results by Phone N=819† |

Self-Selected In-Person

Disclosure of Results N=165† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 49 (12.72) | 52 (13.00) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 759 (93%) | 158 (96%) | ||

| Male | 60 (7%) | 7 (4%) | ||

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 681 (83%) | 143 (87%) | ||

| Non-White | 138 (17%) | 22 (13%) | ||

| Ashkenazi Jewish | ||||

| Yes | 127 (16%) | 22 (13%) | ||

| No | 558 (68%) | 112 (68%) | ||

| Not Captured | 134 (16%) | 31 (19%) | ||

| Education | ||||

| Some College or Less | 330 (40%) | 71 (43%) | ||

| College Degree or More | 485 (59%) | 92 (56%) | ||

| Missing | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | ||

| Household Income – yearly | ||||

| $49,999 or less | 183 (22%) | 33 (20%) | ||

| $50,000 - $99,999 | 213 (26%) | 43 (26%) | ||

| $100,000 - $149,999 | 144 (18%) | 30 (18%) | ||

| $150,000 or more | 166 (20%) | 30 (18%) | ||

| Missing | 113 (14%) | 29 (18%) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/Domestic Partner | 569 (69%) | 117 (71%) | ||

| Not Currently Married/In a Domestic Partnership | 250 (31%) | 48 (29%) | ||

| Personal History of Cancer | ||||

| No | 381 (47%) | 71 (43%) | ||

| Yes | 438 (53%) | 94 (57%) | ||

| Breast | 314 (72% | 60 (64%) | ||

| Ovary | 51 (12%) | 16 (17%) | ||

| Single Primary-Non Breast/Ovary | 49 (11%) | 9 (10%) | ||

| Multiple Primaries | 24 (5%) | 9 (10%) | ||

| Testing for Surgical Treatment Decision | ||||

| Yes | 57 (7%) | 14 (8%) | ||

| No | 762 (93%) | 151 (92%) | ||

| Known Genetic Mutation in Family | ||||

| Yes | 186 (23%) | 34 (21%) | ||

| No | 633 (77%) | 131 (79%) | ||

| Number of FDR/SDR with Cancer | 3.70 (2.33) | 3.69 (1.99) | ||

| Had Multi-Gene Testing** | ||||

| Yes | 231 (28%) | 64 (39%) | ||

| No | 588 (72%) | 101 (61%) | ||

| Distance to Site | 35.82 (145.09) | 18.96 (19.78) | ||

| Recruitment Site | ||||

| University of Pennsylvania | 211 (26%) | 35 (21%) | ||

| Fox Chase Cancer Center | 300 (37%) | 90 (55%) | ||

| University of Chicago | 161 (20%) | 15 (9%) | ||

| John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital at Cook County | 50 (6%) | 7 (4%) | ||

| MD Anderson at Cooper University Hospital | 97 (12%) | 18 (11%) | ||

151 in randomized arms did not complete baseline survey; 43 in the self-select in-person disclosure arm did not complete baseline survey

p= 0.007;

p< 0.001

Factors associated with a preference for in-person disclosure

In both univariable and multivariable analyses, patients who opted for in-person disclosure were more likely to be older (mean 52 YO v. 49 YO, OR 1.02, 95% CI (1, 1.04) p=0.014 in multivariable analysis) (Table 1). Additionally, they were more likely to be undergoing MGPT (39% of the SSIPD group v. 28% of the randomized group, OR 3.06, 95% CI (1.59, 5.88) p=0.001 in multivariable analysis). Being in the group for whom panel testing was not offered (e.g. prior to the introduction of panel testing in 2014) was also related to an increased likelihood of selecting in-person disclosure (OR 1.89, 95% CI (1.05, 3.41), p=0.035). While study site was a statistically significant predictor of self-selecting in-person disclosure in univariable analyses (p<0.001), it was not statistically significant in the full model which included a random intercept to account for genetic counselor effects. After adjusting for age and MGPT and within-counselor correlation, baseline knowledge, change in knowledge and knowledge after disclosure did not differ between the groups. However, baseline general anxiety, depression, cancer –specific distress, state anxiety, and uncertainty were significantly higher, while satisfaction with genetic services was lower, in the group who declined randomization as compared to those randomized (Table 2). Further, among the subset of individuals undergoing MGPT, those who selected for in-person disclosure had lower baseline knowledge of multi-gene testing compared to those willing to be randomized (Table 3).

Table 2–

Patient reported outcomes by willingness to receive results by phone

| Agreed to Randomization – Willing to Receive Results by Phone N=819 |

Self-Selected In- Person Disclosure – (e.g. preference for in-person disclosure) N=165 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Score Range |

Timepoint | Score (Standard Error) | Score (Standard Error) | P value |

| Knowledge | 6–28 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 22.78 (0.09) | 22.71 (0.22) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 23.16 (0.11) | 22.73 (0.23) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.38 (0.11) | 0.02 (0.25) | NSS | ||

| General Anxiety | 0–21 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 6.84 (0.13) | 7.56 (0.30) | 0.007 |

| Post Disclosure | 6.72 (0.15) | 7.54 (0.33) | 0.003 | ||

| Change Score | −0.12 (0.12) | −0.02 (0.26) | NSS | ||

| General Depression | 0–21 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 2.79 (0.10) | 3.41 (0.25) | 0.011 |

| Post Disclosure | 3.06 (0.12) | 3.78 (0.28) | 0.002 | ||

| Change Score | +0.27 (0.11) | +0.37 (0.20) | NSS | ||

| State Anxiety | 20–80 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 35.07 (0.44) | 37.46 (1.09) | 0.008 |

| Post Disclosure | 35.56 (0.49) | 36.74 (1.13) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.49 (0.41) | −0.71 (0.88) | NSS | ||

| Cancer Worry | 0–70 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 17.65 (0.48) | 20.19 (1.14) | 0.021 |

| Post Disclosure | 18.80 (0.60) | 21.05 (1.23) | 0.043 | ||

| Change Score | +1.15 (0.50) | +0.86 (0.92) | NSS | ||

| Uncertainty | 0–15 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 6.54 (0.38) | 7.38 (0.59) | 0.030 |

| Post Disclosure | 8.19 (1.24) | 8.63 (1.25) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +1.65 (1.36) | +1.25 (1.39) | NSS | ||

| Satisfaction | 9–45 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 38.39 (0.15) | 38.18 (0.32) | 0.047 |

| Post Disclosure | 37.98 (0.26) | 38.07 (0.50) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.42 (0.26) | −0.11 (0.47) | NSS | ||

| Planning Screening Mammogram | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 5.99 (0.08) | 6.11 (0.13) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 5.84 (0.10) | 6.16 (0.12) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.15 (0.12) | 0.05 (0.14) | NSS | ||

| Planning Screening MRI | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 4.13 (0.14) | 3.94 (0.20) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 4.08 (0.15) | 4.09 (0.23) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.05 (0.16) | +0.15 (0.23) | NSS | ||

| Planning Prophylactic Mastectomy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.30 (0.11) | 3.34 (0.18) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 2.94 (0.15) | 3.05 (0.21) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.36 (0.17) | −0.29 (0.25) | NSS | ||

| Planning Prophylactic Oophorectomy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.92 (0.13) | 4.23 (0.20) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 3.39 (0.21) | 3.29 (0.26) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.53 (0.23) | −0.94 (0.33) | NSS | ||

| Planning Colonoscopy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.27 (0.19) | 3.38 (0.27) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 3.36 (0.34) | 3.55 (0.39) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.09 (0.37) | +0.17 (0.43) | NSS | ||

NSS = Not Statistically Significant - P =>0.05

All p values included adjustment for baseline differences (age and multi-gene panel testing) between non-randomized groups

Assuming a 20% False Discovery, all statistically significant findings in table 2 would still be statistically significant

Only asked in subset of patients when applicable

Table 3–

Patient reported outcomes by willingness to receive results by phone among those who had MGPT

| Agreed to

Randomization- Willing to Receive Results by Phone N=231 |

Self-Selected In- Person Disclosure of Results N=61 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Score Range |

Timepoint | Score (Standard Error) | Score (Standard Error) | P value |

| Knowledge | 6–28 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 22.48 (0.16) | 22.21 (0.36) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 22.88 (0.20) | 21.96 (0.37) | 0.043 | ||

| Change Score | +0.40 (0.18) | −0.25 (0.35) | NSS | ||

| MultiGene Knowledge | 11–54 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 33.52 (0.32) | 32.00 (0.57) | 0.035 |

| Post Disclosure | 30.97 (0.41) | 30.02 (0.70) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −2.55 (0.52) | −1.98 (0.85) | NSS | ||

| General Anxiety | 0–21 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 6.67 (0.24) | 6.64 (0.46) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 6.22 (0.28) | 6.72 (0.55) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.45 (0.21) | +0.08 (0.43) | NSS | ||

| General Depression | 0–21 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 2.78 (0.20) | 3.14 (0.40) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 2.99 (0.21) | 3.50 (.046) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.22 (0.17) | +0.35 (0.30) | NSS | ||

| State Anxiety | 20–80 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 34.00 (0.85) | 35.58 (1.76) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure Change Score |

34.28 (0.86) +0.28 (0.72) |

35.19 (1.78) −0.39 (1.41) |

NSS NSS |

||

| Cancer-specific distress | 0–70 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 17.48 (0.88) | 18.48 (1.76) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 17.73 (1.06) | 18.93 (1.95) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.25 (0.90) | +0.45 (1.30) | NSS | ||

| Uncertainty | 0–15 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 5.63 (0.27) | 6.50 (0.54) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 6.50 (0.41) | 6.47 (0.60) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | +0.87 (0.39) | −0.03 (0.62) | NSS | ||

| Satisfaction | 9–45 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 39.20 (0.28) | 38.96 (0.49) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 39.56 (0.43) | 39.28 (0.66) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | 0.35 (0.44) | +0.32 (0.61) | NSS | ||

| Planning Screening Mammogram | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 6.06 (0.13) | 6.00 (0.20) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 5.95 (0.14) | 6.00 (0.21) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.11 (0.16) | 0.00 (0.20) | NSS | ||

| Planning Screening Breast MRI | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 4.15 (0.21) | 3.56 (0.28) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 4.03 (0.20) | 3.74 (0.33) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.12 (0.25) | +0.19 (0.33) | NSS | ||

| Planning Prophylactic Mastectomy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.05 (0.17) | 2.90 (0.25) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 2.93 (0.20) | 2.92 (0.32) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.12 (0.23) | +0.02 (0.36) | NSS | ||

| Planning Prophylactic Oophorectomy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.57 (0.17) | 3.88 (0.30) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 3.24 (0.26) | 3.29 (0.37) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | −0.33 (0.30) | −0.59 (0.45) | NSS | ||

| Planning Colonoscopy† | 1–7 | Post Pre-Test Counseling | 3.47 (0.17) | 3.88 (0.30) | NSS |

| Post Disclosure | 3.68 (0.17) | 3.96 (0.31) | NSS | ||

| Change Score | 0.21 (0.19) | +0.38 (0.33) | NSS | ||

NSS = Not Statistically Significant - P =>0.05

All p values included adjustment for baseline difference in age between non-randomized groups

Assuming a 20% False Discovery, no findings in table 3 would be statistically significant.

Only asked in subset of patients when applicable

Outcomes by preference for in-person disclosure

After disclosure of results, those who selected for in-person disclosure had significantly higher general anxiety, depression and cancer-specific distress as compared to those who were randomized (Table 2). While they had higher state anxiety, cancer-specific distress and uncertainty at baseline, these did not differ significantly after result disclosure as compared to those willing to receive results by telephone. The groups did not differ significantly in knowledge or intent to perform risk reducing surgeries or screening post-disclosure (Table 2). Among the subset who had MGPT, those who selected for in-person disclosure had significantly lower genetic knowledge post-disclosure, but they did not differ in any other affective or behavioral outcomes (Table 3). Assuming a 20% False Discovery, all statistically significant findings in table 2 would still be statistically significant, but no findings in table 3 would be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

These data, from a large multi-center real-world study, provide evidence that there are some patients who still prefer face-to-face disclosure of their germline genetic test results. To our knowledge, no other study has described how frequently patients prefer in-person disclosure of genetic test results, characteristics of those who have this preference and outcomes as compared to those who are willing to receive results by telephone. These are critical outcomes to understand as there is increasing data from randomized studies to suggest that telephone is a reasonable alternative to face-to-face communication for genetic counseling and disclosure. Of note, in these randomized studies, they did not account for those declining randomization, a group that may have adverse consequences with the widespread adoption of telephone disclosure. In our study, patients who declined randomization largely did so due to a preference for in-person disclosure. We found that patients who are older and undergoing MGPT were more likely to decline the opportunity for telephone disclosure of their results. Further, those who declined telephone disclosure had higher anxiety, depression, cancer-specific distress and uncertainty than those willing to receive results by telephone. We also found that among patients undergoing more complex MGPT, those who requested in-person disclosure had lower genetic knowledge after pre-test counseling. These findings underscore the importance of assessing patient preference for in-person versus telephone disclosure, as patient reported outcomes differ in the groups preferring in-person counseling.

Multi-gene panel testing is increasingly utilized in germline genetic testing, yet patient outcomes with this testing remain relatively limited. Multi-gene panel testing carries a greater risk for uncertainty, including variants of uncertain significance, uncertainty regarding clinical implications and best approaches for screening and risk reduction and unexpected mutations in genes not consistent with the patient’s personal and family history.19,30 Additionally, counseling for multiple genes, risks and the potential for uncertainty can create a greater risk for misunderstanding and confusion 19 Importantly, the first two randomized studies reporting non-inferior outcomes with telephone disclosure did not include Multi-gene panel testing. While we found no significant differences with telephone disclosure in the COGENT study among the subgroup who received MGPT, this was among individuals who were willing to receive results by telephone.17 In this analysis we found that having MGPT is associated with a preference for in-person disclosure highlighting the complexity of counseling for multiple genes or broader sequencing. While we don’t know what their outcomes would have been if telephone disclosure had been the only option provided, these data suggest that maintaining the option for in-person disclosure of results for patients who are undergoing more complex testing may be important to mitigate the potential for increased short-term distress with telephone disclosure. Additionally, utilizing counseling strategies to minimize informational overload 19 and assessing participant understanding with counseling probes may be useful. An additional tool is the “teachback” approach (asking the patient to explain in his or her own words the concept that has just been discussed and the implications) to assess patient understanding, enhance informed decision-making, and provide the opportunity to remedy misunderstanding.19 These techniques could be important strategies with multi-gene and broader sequencing, even in the setting of in-person disclosure.

Although the mean age difference was not large, it suggests a possibility that another group that may benefit from in-person disclosure is older patients, who may have less comfort with genetic concepts. At advanced ages, they may be more likely to have hearing or age-related cognitive changes that could make understanding or adapting to genetic information more challenging. This is not to suggest that older patients should not be permitted to receive results by telephone. They may at the same time have greater barriers to returning for face-to-face visits and could benefit from telephone disclosure. Yet, these data suggest that they are a subgroup that may prefer face-to-face communication and to the extent that a genetic provider can offer this, their preference should be ascertained.

Equally important, patients preferring in-person disclosure had higher levels of anxiety, depression and cancer-specific distress after pre-test counseling. These measures did not change from baseline to post-disclosure, suggesting these may exist prior to counseling and presentation for genetic services. It is possible that this group of patients was aware of their heightened levels of distress and therefore deliberately sought in-person disclosure of their genetic testing results to ensure better psychosocial support. Further, they maintained higher anxiety, depression and cancer-specific distress after in-person disclosure as compared to those who were willing to receive telephone results, even with in-person disclosure. This implies that preserving the option for face-to-face disclosure of results may be beneficial for this group of more anxious or depressed patients, and may lessen the risk of exacerbating their anxiety, depression or distress with telephone disclosure of results. These data support the value of the psychosocial aspects of genetic counseling and the clinical assessment of a patient’s affective state at the time of pre-test counseling 31. While these assessments of affective and cognitive responses are incorporated into our communication protocols for phone and videoconference delivery 20,32, they are likely of value even for in-person counseling, which is consistent with the psychosocial model of genetic counseling.31 Including clinical assessment of affect (e.g. How are you feeling about genetic testing and learning this information?) at the time of pre-test counseling could identify patients who may benefit from in-person disclosure of results.

We acknowledge that many programs use telephone to deliver genetic services for a variety of reasons. For instance, due to travel or time burdens or to increase access to genetic services where genetic providers are not available. In situations where telephone counseling is used frequently, informing patients about their options for in-person services could be important especially for those who are older, undergoing more complex testing or with evidence of distress. Additionally, employing optimal strategies for telephone communication could be critical. Some strategies include scheduling the disclosure session ahead of time to reduce anticipatory anxiety, utilizing visual aids and intermittent verbal assessments of understanding and distress throughout sessions.20 These approaches utilized in the COGENT study were developed based on patient and provider feedback and intensive audio-review of sessions with less favorable outcomes. Following up with a written summary and interpretation of their test results and ensuring that patients have follow-up with a medical provider could also address any potential risks where in-person communication is not possible.

Videoconferencing, which maintains face-to-face communication and enables the genetic counselor to see a patient’s facial expressions and body language, may be an important alternative when remote counseling is the only option (e.g. scenarios where telephone counseling is used exclusively). There are ongoing multi-center studies comparing remote genetic counseling services by telephone to real time videoconferencing services (NCT02517554, NCT02978729). While there may be additional costs for technology associated with videoconferencing, this could be an important alternative for patients who prefer face-to-face communication and who may experience inferior outcomes with telephone disclosure of results.

We acknowledge several limitations to these data. These outcomes represent immediate post-disclosure outcomes only and longitudinal data will be useful to fully understand the impact of using telephone communication and how outcomes may differ for patients with a preference for face-to-face communication. It is possible that there are other important differences in outcomes for this group that are not captured with our selected measures and some participants did not provide a reason for declining randomization. Additionally, all pre-test counseling was completed in person, thus it is possible that preferences would have been different if the pre-test counseling was provided via telephone as patients may just prefer to continue with the method of counseling that they started with initially.

In summary, while telephone disclosure of cancer genetic test results is a reasonable alternative to in-person disclosure for most patients, some patients decline telephone disclosure given a preference for in-person communication. These data suggest that it is important to assess patient preferences for in-person communication and that the population preferring face-to-face communication may differ from those willing to receive results by telephone. Thus, maintaining the option for face-to-face communication remains important when possible and when telephone is the only option for genetic services, special attention to patient understanding and distress is important, particularly in the setting of multi-gene or more complex genetic testing. Equally important, further study of patient, provider and cost outcomes as telephone disclosure is routinely adopted into clinical practice (e.g. effectiveness) could be helpful to optimize standards for delivery of Precision Medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA160847) and the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA006927).

RESEARCH SUPPORT: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA160847).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: All authors report that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION:

Study concept and design: Bradbury, Patrick-Miller, Egleston.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Beri, Bradbury

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Statistical Analysis: Egleston

REFERENCES

- 1.Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy Statement Update: Genetic and Genomic Testing for Cancer Susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 33:3660–7, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman JS, Hahn SE, Catania JW, et al. : Genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer disease: joint practice guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Genet Med 13:597–605, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. : 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 124:2761–96, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tchan M, Savige J, Patel C, et al. : KHA-CARI Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Guideline: Genetic Testing for Diagnosis. Semin Nephrol 35:545–549 e2, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(ACMG) ACoMGaG: Policy Statement: Points to Consider in the Clinical Application of Genomic Sequencing, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Biesecker BB, Boehnke M, Calzone K, et al. : Genetic counseling for families with inherited susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Jama 269:1970–4, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trepanier AM, Allain DC: Models of service delivery for cancer genetic risk assessment and counseling. J Genet Couns 23:239–53, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berliner JL, Fay AM: Risk assessment and genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns 16:241–60, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG: Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: a systematic review. Jama 299:1320–34, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumanis L, Evans JP, Callanan N, et al. : Telephoned BRCA1/2 Genetic Test Results: Prevalence, Practice, and Patient Satisfaction. J Genet Couns, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess KR, Carmany EP, Trepanier AM: A Comparison of Telephone Genetic Counseling and In-Person Genetic Counseling from the Genetic Counselor’s Perspective. J Genet Couns 25:112–26, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenkins J, Calzone KA, Dimond E, et al. : Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genetics in Medicine 9:487–495, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SA, Marvin ML, Riley BD, et al. : Identification of Genetic Counseling Service Delivery Models in Practice: A Report from the NSGC Service Delivery Model Task Force. Journal of Genetic Counseling 22:411–421, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. : Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: a cluster randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 106, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. : Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:618–26, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinney AY, Steffen LE, Brumbach BH, et al. : Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone Delivery of BRCA1/2 Genetic Counseling Compared With In-Person Counseling: 1-Year Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller LJ, Egleston BL, et al. : Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone vs In-Person Disclosure of Germline Cancer Genetic Test Results. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute:djy015-djy015, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick-Miller L, Egleston BL, Daly M, et al. : Implementation and outcomes of telephone disclosure of clinical BRCA1/2 test results. Patient Educ Couns 93:413–9, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Long J, et al. : Development of a tiered and binned genetic counseling model for informed consent in the era of multiplex testing for cancer susceptibility. Genet Med 17:485–92, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick-Miller LJ, Egleston BL, Fetzer D, et al. : Development of a communication protocol for telephone disclosure of genetic test results for cancer predisposition. JMIR Res Protoc 3:e49, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly K, Leventhal H, Marvin M, et al. : Cancer genetics knowledge and beliefs and receipt of results in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals receiving counseling for BRCA1/2 mutations. Cancer Control 11:236–44, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaphingst KA, Facio FM, Cheng MR, et al. : Effects of informed consent for individual genome sequencing on relevant knowledge. Clin Genet 82:408–15, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Speilberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. : Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–70, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 41:209–18, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. : A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol 21:564–72, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieterse AH, van Dulmen AM, Beemer FA, et al. : Cancer genetic counseling: communication and counselees’ post-visit satisfaction, cognitions, anxiety, and needs fulfillment. J Genet Couns 16:85–96, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, et al. : A multivariate technique for multiplying imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology 27:85–95, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57:289–300, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robson M: Multigene Panel Testing: Planning the Next Generation of Research Studies in Clinical Cancer Genetics. Journal of Clinical Oncology 32:1987–1989, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biesecker BB, Peters KF: Process studies in genetic counseling: peering into the black box. Am J Med Genet 106:191–8, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradbury A, Patrick-Miller L, Harris D, et al. : Utilizing Remote Real-Time Videoconferencing to Expand Access to Cancer Genetic Services in Community Practices: A Multicenter Feasibility Study. J Med Internet Res 18:e23, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]