Abstract

Common variable immunodeficiency syndrome (CVID) is a heterogeneous disorder characterised by diminished levels of IgG, IgA and/or IgM, and recurrent bacterial infections. Sinopulmonary infections are most commonly reported followed by gastrointestinal (GI) infections. GI tract represents the largest immune organ with abundance of lymphoid cells, its involvement can manifest variably ranging from asymptomatic involvement to florid symptoms and signs. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (DNLH) of the GI tract is characterised by numerous small polypoid nodules of variable size in the small intestine, large intestine or both. It is commonly seen in association to immunodeficiency states such as CVID, IgA deficiency and chronic infections due to Giardia lamblia and Helicobacter pylori and cryptosporidiosis. Repetitive antigenic stimulation leads to lymphoid hyperplasia. We herein describe a case of DNLH of the intestine and another case of duodenal cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection associated with CVID.

Keywords: infections, endoscopy, small intestine

Background

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is characterised by hypogammaglobulinaemia with phenotypically normal B cells. It manifests at variable age with bimodal peak age of presentation with first peak between 1–5 years and another between 18–25 years.1 Respiratory infections are most frequent followed by gastrointestinal (GI) involvement. CVID is also associated with increased risk of granulomatous disease and higher risk of malignancies.2

GI involvement in CVID manifests variably from asymptomatic to chronic malabsorption, giardiasis, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, chronic atrophic gastritis and pernicious anaemia.3 Biopsy from GI tract may show wide variety of morphological changes ranging from villous atrophy, diffuse lymphoid aggregates, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and rarely lymphoma. Clinically, patients can present with vague abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, weight loss, rarely with intestinal obstruction and bleed from large lymphoid nodular aggregates.4

Majority of cases of CVID are sporadic involving mutations in TNFRSF13B gene but rare cases with autosomal recessive or dominant pattern of inheritance have been reported.5

We emphasise the importance of considering CVID in any patient with GI manifestations even in the absence of recurrent bacterial infections. Diagnostic delay results in more morbidity and complications in untreated patients.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 52-year-old man presented with 3 weeks history of watery stools associated with epigastric discomfort. On admission, the patient’s blood pressure, body temperature and pulse rate were 130/80 mm Hg, 36.8°C and 88/min, respectively. On physical examination, his built was average and there were no significant features. The liver and spleen were not palpable.

His family history was unremarkable, and his social history was negative for alcohol and smoking.

Case 2

A 28-year-old man presented with 6 months history of loose stools and generalised abdominal discomfort. He had weight loss of about 3–4 kg. There was no history of travel. There was no history of alcohol and substance abuse. His clinical examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Case 1

Laboratory studies on admission showed the following results: white blood cell count, 6.800/μL; haemoglobin, 13.8 g/dL; platelet count, 284 000/mm3; albumin, 4.26 g/dL; Aspartate transaminase 32 U/L (normal <42); Alanine transaminase 19 U/L (normal <40). Other routine blood tests (kidney function test and thyroid function tests) were normal. Vitamin B12 level was 176.8 pg/mL (normal range: 193–982 pg/mL). Folate level was normal. Serum iron, transferrin saturation and total iron binding capacity were within normal ranges. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 13 mm/h.

Laboratory work-up was carried out considering the possibility of infectious diarrhoea, celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. The stool specimens were negative for ova or parasites. Anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA, antibodies against gliadin and/or endomysium were negative.

Upper GI endoscopy and duodenal biopsy were done to rule out gluten enteropathy. Duodenal histology revealed CMV inclusion bodies (figure 1). Serum electrophoresis showed diminished immunoglobulin level across all subclasses: IgA 0.231 (normal 0.7–4 g/L), IgM 0.222 (normal 0.4–2.3 g/L) and IgG 2.3 (normal 7–16 g/L).

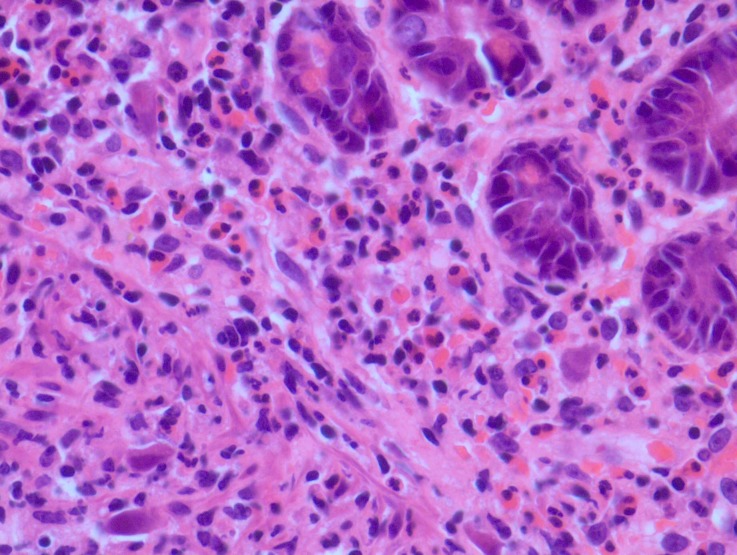

Figure 1.

Duodenal biopsy showing large CMV inclusions.

Case2

Similar to the first case work-up was done considering differential diagnosis as infectious diarrhoea, celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Laboratory investigation showed haemoglobin of 13.5 g/dL, total leucocyte count 11 200/mm3, negative stool microscopy and culture results, and celiac serology and HIV serology were negative. Thyroid profile was normal. Serum immunoglobulin quantification showed IgA 0.15 (normal 0.7–4 g/L), IgM 0.65 (normal 0.4–2.3 g/L) and IgG 2.7 (normal 7–16 g/L).

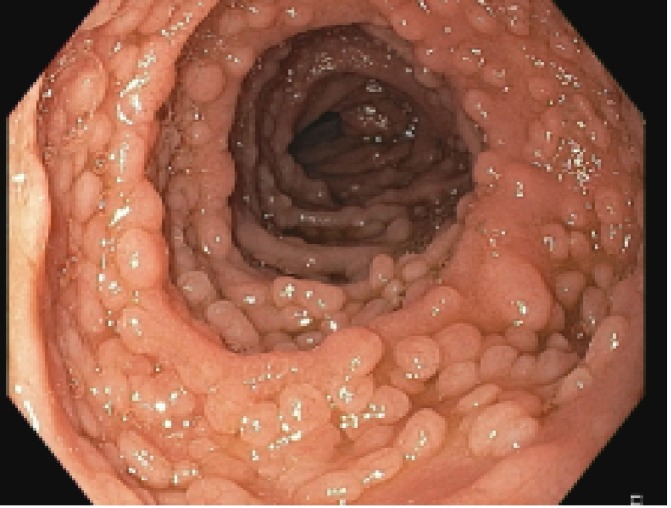

Upper GI endoscopy showed multiple sessile polypoid lesions in first and second part of duodenum and subsequent colonoscopy also revealed similar mucosal lesions throughout the colon as well as terminal ileum (figures 2 and 3). Mucosal biopsies were taken from both duodenum and ileum. Biopsy from terminal ileum showed absent plasma cells with negative staining for CD-138 (figures 4 and 5). Duodenal biopsy showed nodular lymphoid hyperplasia and mild villous blunting (figure 6).

Figure 2.

Endoscopy image showing duodenal polypoid lesions.

Figure 3.

Colonoscopy image showing multiple sessile, polypoid lesions in terminal ileum.

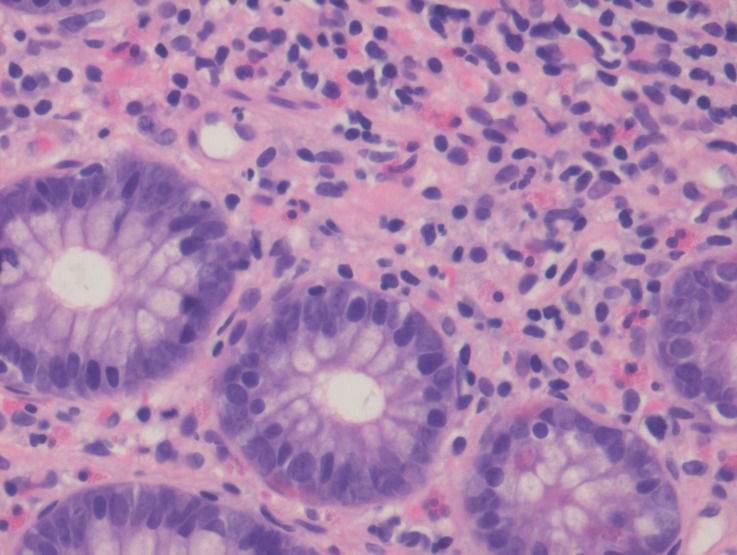

Figure 4.

Ileal biopsy showing absence of plasma cells on haematoxylin and eosin stain.

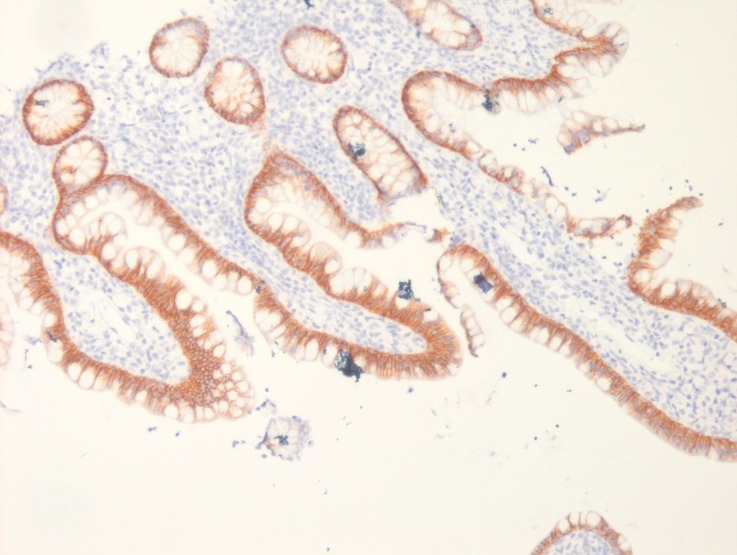

Figure 5.

Ileal biopsy with negative immunohistochemical staining for CD-138.

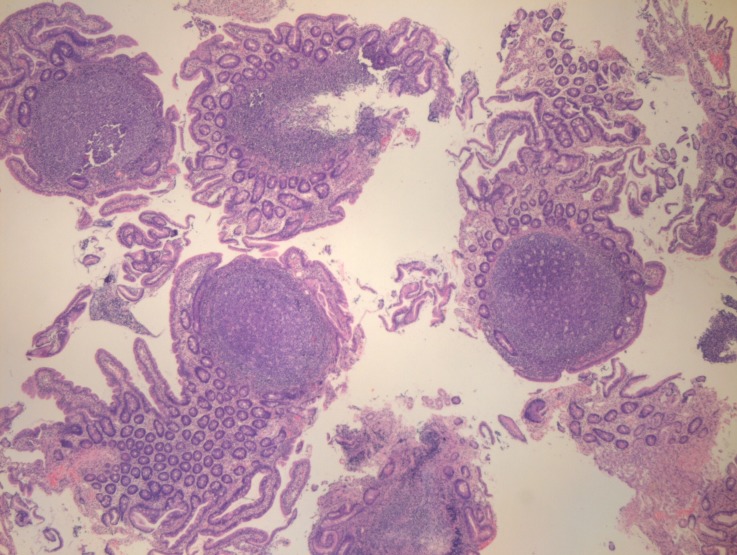

Figure 6.

Duodenal biopsy suggestive of diffuse, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia.

Treatment

First patient received oral gancyclovir and intravenous immunoglobulin, whereas second patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin alone.

Outcome and follow-up

On follow-up at 3 and 6 months, both the patients were asymptomatic on periodic intravenous immunoglobulin infusion.

Discussion

CVID is a heterogeneous disease characterised by diminished levels of immunoglobulin A, IgG and/or IgM and diminished antibody response to vaccination.6 It is also known as acquired hypogammaglobulinaemia as age of onset is usually later.

After selective IgA deficiency, CVID is the second most common immunodeficiency disorder.

Most patients with CVID have respiratory infection as presentation followed by GI symptoms.7

Majority of the patients report at least one episode of respiratory infection.

There is an increased risk of granulomatous disease, joint involvement and malignancies8

Our first case had duodenal CMV infection. CVID predisposes to variety of GI infections due to Giardia lamblia and Helicobacter pylori, and CMV and cryptosporidiosis.

Kralickova P et al, in a retrospective analysis on series of 32 patients with CVID, reported CMV enteritis in three of the patients and all of which responded to treatment.9 Our patient had good clinical response to ganciclovir and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy.

Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (DNLH) results from chronic antigenic stimulation and is seen in immunodeficient as well as immunocompetent individuals. DNLH may be seen in upto 20% of patients with CVID and it may remain asymptomatic or present with abdominal discomfort, chronic diarrhoea, intestinal obstruction and rarely as massive GI bleed.10

Both of our cases presented with diarrhoea.

Nodules in DNLH can vary in size from 2 to 10 mm and can be present in stomach, small intestine (terminal ileum—most common) and colon. The latter may be confused with other polyposis syndrome as in our second case.11

DNLH is associated with increased risk of intestinal and extraintestinal lymphoma. DNLH may resemble lymphoma clinically as well as histologically but can be distinguished from it by polymorphic nature of the infiltrate, the presence of reactive follicles within the lesion, and by use of immunohistochemical or molecular analysis and the absence of significant cytologic atypia.12

Diagnosis of DNLH is based on histology and treatment based on the endoscopic appearance alone may lead to overtreatment of the benign condition. Some authors also recommend capsule endoscopy to evaluate the extent of small bowel involvement and to rule out any associated complication.

In our second case, capsule endoscopy showed the nodular lesions throughout the small bowel.

Surveillance of DNLH with capsule endoscopy and small bowel biopsy has been suggested but there are no clear guidelines on the surveillance interval.13

To conclude, CVID represents a heterogeneous condition, possibility of this entity should be kept in mind during work-up of chronic infection.

Learning points.

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) should be considered as differential while doing work-up for cases with chronic diarrhoea.

CVID can present with variety of gastrointestinal pathologies including CMV infection, diffuse nodular hyperplasia.

Diagnosed cases of CVID respond well to periodic intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Footnotes

Contributors: MN- Manuscript preparation and submission. RS- Editing. SRM- Editing. LL- Pathology slides.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Hogenauer CH, Hammer HF. Maldigestion and malabsorption : Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002, 1775. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lai Ping So A, Mayer L. Gastrointestinal manifestations of primary immunodeficiency disorders. Semin Gastrointest Dis 1997;8:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cooper MD, Schroeder HW. Primary immune deficiency : Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci A, Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 16th edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hermaszewski RA, Webster AD. Primary hypogammaglobulinaemia: a survey of clinical manifestations and complications. Q J Med 1993;86:31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lopez-Herrera G, Tampella G, Pan-Hammarström Q, et al. Deleterious mutations in LRBA are associated with a syndrome of immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90:986–1001. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chapel H, Cunningham-Rundles C. Update in understanding common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVIDs) and the management of patients with these conditions. Br J Haematol 2009;145:709–27. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07669.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wood P, Stanworth S, Burton J, et al. Recognition, clinical diagnosis and management of patients with primary antibody deficiencies: a systematic review. Clin Exp Immunol 2007;149:410–23. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03432.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol 1999;92:34–48. 10.1006/clim.1999.4725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kralickova P, Mala E, Vokurkova D, et al. Cytomegalovirus disease in patients with common variable immunodeficiency: three case reports. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2014;163:69–74. 10.1159/000355957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piaścik M, Rydzewska G, Pawlik M, et al. Diffuse nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract in patient with selective immunoglobulin A deficiency and sarcoid-like syndrome--case report. Adv Med Sci 2007;52:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Postgate A, Despott E, Talbot I, et al. An unusual cause of diarrhea: diffuse intestinal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in association with selective immunoglobulin A deficiency (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:168–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ranchod M, Lewin KJ, Dorfman RF. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract. A study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1978;2:383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bayraktar Y, Ersoy O, Sokmensuer C. The findings of capsule endoscopy in patients with common variable immunodeficiency syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology 2007;54:1034–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]