Abstract

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is an optic neuropathy of mitochondrial inheritance, characterised by incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Typically, young male patients present with sequential, severe, rapidly progressive loss of central vision, with characteristic funduscopic findings. However, LHON may present at any age, in both genders, and fundus examination may be normal. Evidence has emerged to support the role of environmental factors in triggering LHON, by disrupting the normal mechanisms of mitochondrial function. We present two clinical cases of LHON of late onset, and provide a literature review on atypical cases of LHON and the role of environmental triggers.

Keywords: neuroopthalmology, ophthalmology, visual pathway, genetics

Background

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is an optic neuropathy (ON) of mitochondrial inheritance, being the most common mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) related disease.1

Over 90% of patients have one of three point mutations in mtDNA, MTND4*LHON11778A, MTND1*LHON3460A and MTND6*LHON14484C2; notably, particular mutations may have implications in clinical manifestations and visual prognosis. However, only 20%–60% of men and 4%–30% of women carriers of mutation will develop ON.1

The incomplete penetrance of the mtDNA mutations in LHON and variable expression of disease suggests a role for non-genetic factors as triggers for LHON. Environmental triggers may contribute to LHON by affecting mitochondrial biogenesis. Increased mtDNA content and efficient mitochondrial biogenesis accounts for the incomplete penetrance pattern in homoplasmic LHON carriers, and environmental agents may cause reduction of mtDNA content.3 Men are more affected than women; the reason remains ill-defined, but oestrogens may play a protective role.4 mtDNA mutations affect subunits of the mitochondrial complex I of the respiratory chain, leading to energy insufficiency and formation of toxic reactive oxidative species; increasing evidence supports the role of chronic oxidative stress as the main factor leading to retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death by apoptosis.1 Environmental factors implicated in LHON include alcohol, head trauma or acute illness and antituberculosis drugs.1 4 5

Case presentation

Patient 1

A 40-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department reporting sudden, painless, rapidly progressive central vision loss with sequential involvement of the fellow eye within 3 weeks from onset. The patient was HIV-positive under highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with nevirapine, tenofovir and emtricitabine; she reported smoking, and was in remission for drug abuse. No family history of blindness was elicited.

On ophthalmological examination, visual acuity (VA) was counting fingers (CF) at 1 m bilaterally (oculus uterque, OU). Pupillary reflexes were symmetrical without relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). On fundus examination, mild, bilateral blurring of the optic disc margin was observed, without vascular or macular changes (figure 1). No improvement in VA was observed at 10-week follow-up. On fundus examination, there had been progression to bilateral optic nerve atrophy. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging documented parapapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) thinning in the temporal sectors (figure 2). Standard automated perimetry (SAP) documented two residual islets of visual field (VF) in OD and complete VF loss in OS.

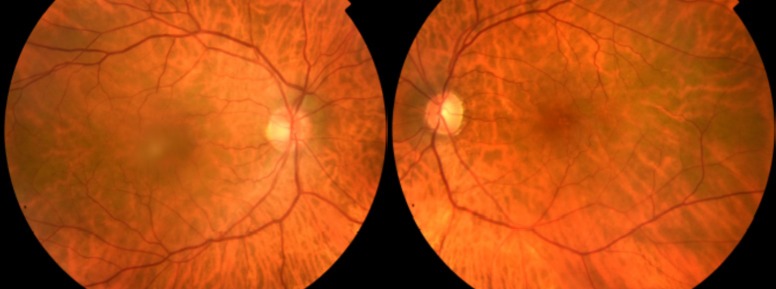

Figure 1.

In patient 1’s fundus photograph at presentation mild, bilateral blurring of the optic disc margins is observed; no macular or vascular changes are observed.

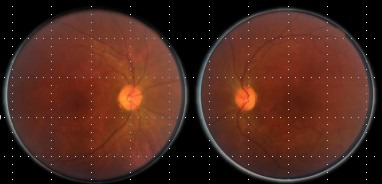

Figure 2.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT Spectralis, Heidelberg) analysis. In patient 1 at 10-week follow-up, bilateral thinning of the parapapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) was observed in the temporal sectors. OD, oculus dexter; OS, oculus sinister.

Patient 2

A 67-year-old Caucasian man was referred to the neuro-ophthalmology specialist for painless central vision loss in oculus sinister (OS) with onset 6 months earlier; sequential involvement of the fellow eye occurred within 6 weeks of onset. Patient history was relevant for bladder carcinoma 8 years earlier, cigarette smoking for 4 years, cataract surgery and ocular hypertension treated with a prostaglandin analogue for 2 years; no family history was elicited.

On ophthalmological examination, VA was 20/100 in oculus dexter (OD) and CF at 0.5 m in OS, without RAPD. On anterior segment slit-lamp examination bilateral pseudophakia was observed; IOP was 16 mm Hg bilaterally. Fundus examination revealed mild optic disc pallor OU, most marked in OS (figure 3). OCT at first visit documented pRNFL thinning in temporal sectors in OS; at 6-month follow-up pRNFL thinning was also noted in OD, and progression was documented in OS (figure 4). SAP assessment at first visit revealed cecocentral scotoma in OS, and at 6-month follow-up OD had developed a cecocentral scotoma and OS had an enlarged central scotoma.

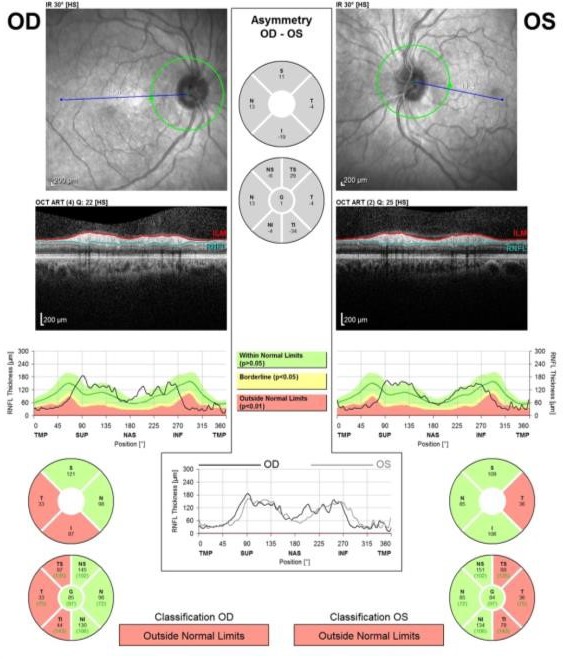

Figure 3.

In patient 2’ fundus photograph at presentation, mild optic disc pallor is observed bilaterally, most marked in oculus sinister.

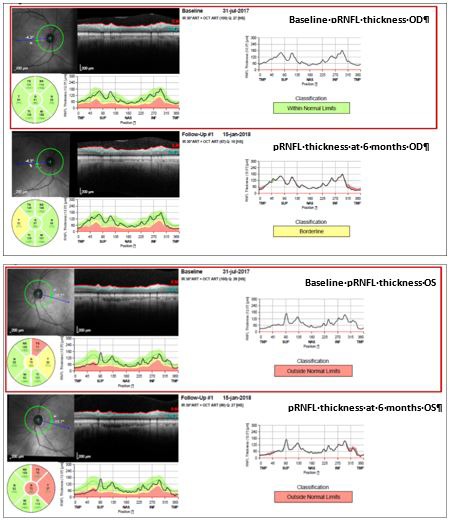

Figure 4.

Patient 2’s spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, showing progressive parapapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) thinning in OU from baseline evaluation. OD, oculus dexter; OS, oculus sinister.

Investigations

Patient 1

Serum HIV viral load was undetectable, with normal CD4+ lymphocyte counts; other infectious serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal, and antinuclear antibody (ANA), perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA), cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA), antiphospholipid antibodies and anti-neuromyelitis optica (anti-NMO) were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed no cytochemical changes, oligoclonal bands or anti-aquaporin (anti-AQP) antibodies. Orbital and head MRI revealed no changes. Targeted mutation analysis for LHON was performed, yielding homoplasmy for MTND1*LHON3460A mutation.

Patient 2

Neurological examination and neuroimaging evaluation yielded no relevant findings. Infectious and autoimmune aetiologies were excluded, and targeted mutation analysis for LHON was performed, with identification of a homoplasmic mutation in MTND4*LHON11778A.

Treatment

Patient 1 was proposed for enrolment in a clinical trial of ibedenone therapy but refused therapy; she was referred to a low-vision specialist.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient 1

At last follow-up visit 12 months from disease onset, patient’s VA remained stable, with stable OCT findings.

Patient 2

At last follow-up visit 15 months from disease onset, the patient’s VA in OD dropped to 20/160, and remained stable in OS.

Discussion

LHON typically presents in male patients between the ages of 15 and 30 years, and family history is often helpful in aiding with diagnosis. However, it has been increasingly known that LHON may present at any age, and LHON should be considered in the differential diagnosis of optic neuropathies irrespective of age, gender, and family history. Different definitions of late-onset LHON have been used in the literature,6–9 but generally LHON has been considered to be a disease affecting patients up to 30 years, according to most publications. Ageing has been shown to be associated with decreased mtDNA copies, and hence increased disruption in mitochondrial biogenesis10 and increased susceptibility to environmental agents. Cigarette smoking has been linked to mitochondrial toxicity and triggering of LHON,11 reducing mtDNA copy numbers and promoting oxidative stress.5 12 Smoking has been shown to cause significant reduction in the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes I and IV in RGCs, causing ATP depletion.5 This mechanism may be due to direct compromise of the complex I activity and due to increased carboxyhemoglobin levels and hence reduced arterial blood oxygen availability.13 In addition, cigarette smoking has been shown to increase the penetrance in LHON12 13 and to be an independent factor for visual failure in LHON13; higher levels of smoking may be associated with increased risk for visual failure.13 Nucleoside-analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) for HIV have also been proposed as triggers through their effects in mitochondrial gamma polymerase enzyme involved in mtDNA replication.14 15; implicated NRTI drugs in LHON have included zidovudine, stavudine and zalcitabine.14–16 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, patient 1 may be the first case in which a possible association between HAART and the 3460 mutation is established; cases previously reported involved carriers of 11 778 and 14 484 mutations.14 15 We hypothesise the late onset of ON in patient 1 was related to the disruptive effects of smoking and NRTI on mitochondrial bioenergetics, already prone to imbalance due to her 3460 mutation but kept in balance by her oestrogen status. Patient’s 2 ON of late onset may be related to senescence and also to recent smoking habits.

Learning points.

The diagnosis of mitochondrial optic neuropathy (ON) requires a high index of suspicion, and should be considered in cases of unexplained bilateral ON irrespective of age, gender, family history and funduscopic appearance;

Environmental factors must be taken into consideration in any patient presenting with ON, as their role in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) pathophysiology remains to be understood;

Highly active antiretroviral therapy therapy for HIV/AIDS is an increasingly recognised risk factor for trigger of LHON, and may be related to other mitochondrial DNA mutations than previously described.

Footnotes

Contributors: NM-C: planning, reporting, conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. RPP: conduct, analysis and interpretation of data. JTF: planning, reporting, conducting, conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data. JPC: planning, conducting, conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Newman NJ, Biousse V. Hereditary optic neuropathies. Eye 2004;18:1144–60. 10.1038/sj.eye.6701591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yates B, Braschi B, Gray KA, et al. . Genenames.org: the HGNC and VGNC resources in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45(D1):D619–25. 10.1093/nar/gkw1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giordano C, Iommarini L, Giordano L, et al. . Efficient mitochondrial biogenesis drives incomplete penetrance in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2014;137(Pt 2):335–53. 10.1093/brain/awt343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wallace DC, Lott MT. Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy: Exemplar of an mtDNA Disease. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017;240:339–76. 10.1007/164_2017_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giordano L, et al. . Cigarette toxicity triggers Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy by affecting mtDNA copy number, oxidative phosphorylation and ROS detoxification pathways. Cell Death and Disease 2015; 6:e 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vincent SJ, Lowe KA, Monsour CS. Never too old: late-onset Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Clin Exp Optom 2018;101:137–9. 10.1111/cxo.12530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dimitriadis K, Leonhardt M, Yu-Wai-Man P, et al. . Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy with late disease onset: clinical and molecular characteristics of 20 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:158 10.1186/s13023-014-0158-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfeiffer ML, Hashemi N, Foroozan R, et al. . Late‐onset Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013;41:690–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Demidenko A, Vakili R, Eggenberger ER, et al. . Late onset Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2008;32:1:41–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang R, Wang Y, Ye K, et al. . Independent impacts of aging on mitochondrial DNA quantity and quality in humans. BMC Genomics 2017;18:890 10.1186/s12864-017-4287-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsao K, Aitken PA, Johns DR. Smoking as an aetiological factor in a pedigree with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:577–81. 10.1136/bjo.83.5.577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sadun AA, Carelli V, Salomao SR, et al. . Extensive investigation of a large Brazilian pedigree of 11778/haplogroup J Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:231–8. 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00099-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirkman MA, Yu-Wai-Man P, Korsten A, et al. . Gene–environment interactions in Leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Brain 2009;132(9):2317–26. 10.1093/brain/awp158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackey DA, Fingert JH, Luzhansky JZ, et al. . Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy triggered by antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus. Eye 2003;17:312–7. 10.1038/sj.eye.6700362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shaikh S, Ta C, Basham AA, et al. . Leber hereditary optic neuropathy associated with antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:143–5. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00716-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moodley A, Bhola S, Omar F, et al. . Antiretroviral therapy-induced Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. South Afr J HIV Med 2014;15:69–71. 10.4102/sajhivmed.v15i2.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]