Introduction

Racial diversity in medicine, and in particular gastroenterology (GI), is a topic that has received a great deal of interest in the last several decades, but is an area with very little published work and research performed to date, as opposed to gender diversity1. The definition of underrepresented in medicine (UIM) (as defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges) means those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population2. Historically, UIM has consisted of the following three racial/ethnic groups: African-American/Black, American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian and Hispanic/Latino. It is predicted that by 2050 over half of the U.S. population will be from a non-Caucasian background, up from 18% in 20173, yet is projected that the U.S. physician workforce will not mirror this same change4. Ultimately, we should strive and want to have a physician workforce that reflects our patient population for whom we care; one such goal should be that the proportion of UIM physicians reflect the proportion of UIMs in the U.S. population. Along these lines, there are a number of important reasons for having a more diverse physician workforce. First, UIMs are more likely to work in underserved communities or areas where access to healthcare may be limited5,6. Second, UIMs can help exchange cultural customs/values which help in patient adherence to treatment recommendations and improve patient experience7. Third, UIMs bring different points of view to the workplace and scholarly activities and teams composed of diverse individuals operate with increased creativity and promote cross-cultural competence8. Lastly, UIMs are more likely to perform research that addresses healthcare disparities and can serve as mentors to younger physicians and students9. Given our changing demographics towards a more diverse U.S. population and the benefits of having a diverse physician workforce, this paper aims to provide an update on current trends as it relates to UIMs in medicine and GI, give an overview of GI societies work in the area of diversity and discuss the role of cultural competency in medical practice.

Data on Faculty, Practice and Trainees

Along all points of the educational pathway there has been very little change, and in some cases a decline, with regards to the number and proportion of UIMs with respect to race/ethnicity. The most concerning trends along this continuum have been at the future physician entry point– medical school. There has been minimal to no change in the proportion of UIM medical school matriculants between 1980 and 2016 despite positions in medical schools increasing by more than one-quarter over this same time period10. Similarily, there is no increase in the proportion of UIM medical school graduates. Over a three decade time period (1980–2012), the number and proportion of Caucasian males has decreased sharply which has been met with increases in the number and proportion of Caucasian women and Asian men and women graduating from medical school11; however, these same increases and trends have not been present for UIMs. More concerning is that during the first decades of the 21st century there is a decrement in the proportion of UIM medical school graduates12 as well as significantly lower four-year medical school graduation rates for UIMs compared to non-UIMs12.

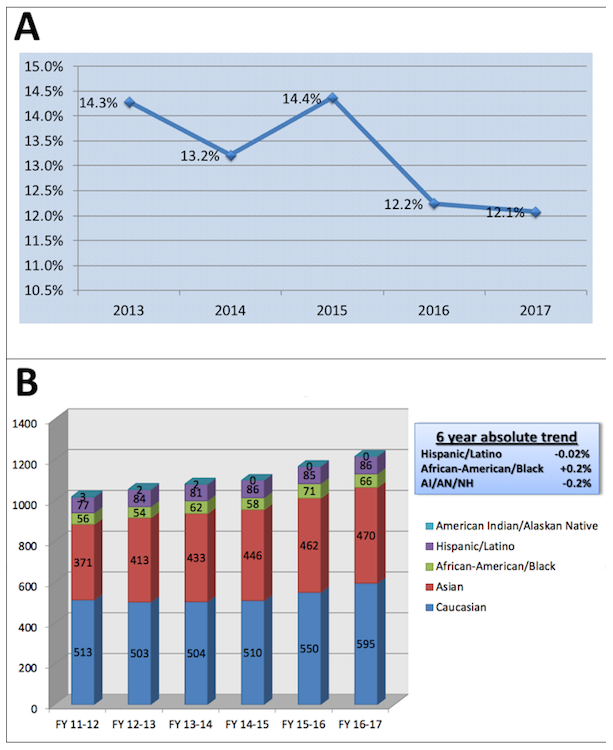

Likewise, concerning trends have also been observed for UIMs in the more differentiated parts of the educational pathway - namely in internal medicine residency and GI fellowship. For internal medicine, there has been a general decline in the number of active internal medicine residents from most UIM groups. Over the last six years, while there has been a relative increase in the number of active internal medicine residents who identify as Hispanic/Latino (+5.3%), relative decreases have been noted for African-Americans/Blacks (−1.1%) and American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) (−17.9%)13. The same changes/trends are also apparent within GI fellowship programs for UIMs. There has been a steady decline in the proportion of UIM GI fellowship applications over the last five years14 (Figure 1A) and during the same timeframe while we note an increase in the number of Caucasian, Asian, and African-American/Black GI fellows, there has been a relative decrease in Latino/Hispanic and AI/AN GI fellows; for example from 2014 to 2017 there have been no AI/AN graduating GI fellows in the U.S. (Figure 1B)13. If such trends continue along this educational pathway it is projected that it will take several decades before the GI physician workforce mirrors the society for whom it cares.

Figure 1.

A. Percentage of underrepresented minorities (URMs) applying to U.S. GI fellowships, 2013-2017. B. Racial representation of GI fellows among U.S. programs, 2011-2017.

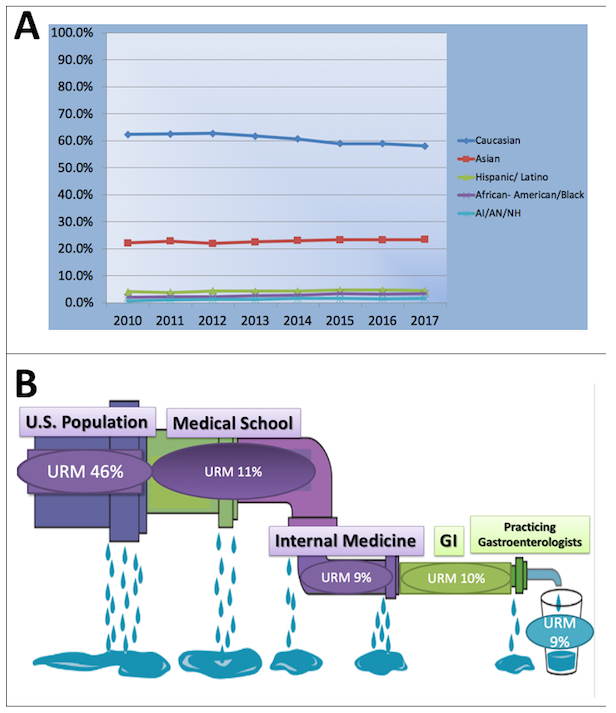

One of the critical steps to improve the UIM educational pathway is to ensure that there is a diverse faculty both at our medical schools and within our GI divisions. Not only does this ensure that there are mentors for UIM students, but there is strong correlation between the proportion of matriculating UIM medical students and the proportion of UIM faculty15. Over the last forty years, there has been tremendous change with respect to academic faculty in terms of race/ethnicity. These changes very much mirror what has been observed in medical schools – a decline in the proportion of Caucasian academic medicine faculty met with a significant increase in the proportion of Asians in academic faculty positions. At the same time, the proportion of UIM faculty has also changed, increasing from 4.1% in 1980 to 10.4% in 2017, with the largest increase noted in Hispanic/Latino faculty. However, there has been no change with respect to the proportion of African-American/Black academic faculty within the last twenty years and AI/AN/Native Hawaiin physicians represent less than 0.2% of all academic faculty positions. Stratification of academic faculty by rank and race/ethnicity during the last forty years also reveals important information regarding trends for UIM faculty recruitment and retention. Importantly, there have been increases observed among the proportion of UIMs at the assistant, associate, and full professor ranks over this time period. On the other hand, the proportion of UIM academic faculty has never exceeded more than 10% at each academic rank and more concerning is that there has been a decline in the proportion of UIMs at junior academic faculty positions in recent years16. Looking more closely at GI divisions, similar patterns are also noted with only 9% of U.S. academic gastroenterologists identifying as UIM and there has been little change in the proportion of UIMs within GI divisions over the last decade17 (Figure 2AB).

Figure 2.

A. Racial represenation of GI faculty among U.S. medical schools, 2010-2017. B. Representation of the decrement in the percentage of underepresented minorities (URMs) from pre-medical school through practicing gastroenterologists in the U.S.

Cultural Competency Curricula

Gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship training programs are charged by their accrediting body with developing policies aimed to recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive workforce18, understanding how essential this is to enriching the learning environment, and to producing a GI workforce that more closely represents the diverse patient population we serve. Provider-patient concordance studies have demonstrated consistently that patients value sharing commonality with their physicians on the dimensions of race and ethnicity, as well as language19. This underscores the need to consider not only a trainee’s identity, but what cultural skillsets they bring, and how we prepare them to provide high quality care that addresses patients’ cultural and linguistic needs in our effort to combat health care disparities.

Cultural competency training in the medical field exists as a multi-level entity. Just as individuals can be culturally aware and competent, institutions and health care systems must also be culturally-competent. This can include training and education on cultural competence, ensuring regionally pertinent translation and interpretation, and creating leadership positions, and committees to lead program execution and monitor success. At the individual level, the GI fellow encounters limited exposure to dedicated cultural competency education. This is likely a result of the limited guidance program directors receive in this area, and sparse literature on this topic tailored specifically to gastroenterology. For this reason GI educators must look beyond the confines of GI-specific material, and think broadly and creatively about how to incorporate cultural competency education as a pertinent and vital component of a strong fellowship training program.

Understanding how culture impacts a patient’s perspective of health and nutrition, and its influence on expression of symptoms and concerns can empower physicians to idenitfy the right diagnosis, and make treatment recommendations that will be better received and adhered to19,20. An example of excellence in cultural competence education was demonstrated in a family medicine residency program21. This included a one-month orientation for intern onboarding to provide in depth exposure to the neighboring community and foster a better understanding of their patients’ experience, and thirty-hours of didactics including discussion on traditional healers and community-oriented primary care. Faculty were also supported with a yearly career development retreat to provide them the necessary tools to serve as educators in this area. In contrast an example without such training is from a GI fellowship training program in New York City21, where trainees worked with standardized patients in one of three clinical scenarios: 1) poor health literacy, 2) disclosing/apologizing for a complication to a patient who mistrusts the healthcare system, and 3) breaking adverse news to a patient with a fatalistic mentality. Educators discovered that the majority of GI trainees (8 of 11 fellows) did not recognize the patient’s limited health literacy, mistrust for the healthcare system, apologize for the complication, or explore the patient’s fatalistic belief system. This strategy highlighted important learning opportunities for GI fellows and areas of focus for teaching faculty.

Intentional integration of cultural competency education into a gastroenterology fellowship training program is both feasible and valuable. Now more than ever we must prepare future gastroenterologists to practice with cultural humility, demonstrate respect and a desire to understand how their patient’s background and experiences shape their health, and impact communication. Tackling specific sociocultural aspects such as health literacy and mistrust of the healthcare system can be done with case-based discussion and standardized patient encounters when possible. Ensuring trainees understand how and when to use linguistic services will encourage this behavior to be the norm and not the exception. Aligning these efforts as core elements of our training programs will help trainees value culturally competent practices, and be well prepared to serve a diverse patient population22.

GI Societies Approaches

The four major U.S. GI societies (AASLD, ACG, AGA and ASGE) have recognized and put efforts to include more women in GI and hepatology and to stimulate and engage young learners into the subspecialty, both with successes. In 2017 at the leadership level, the presidents of the four societies were all women23, a momentous occasion, with cumulatively the AASLD (founded 1950), ACG (founded 1932), AGA (founded 1897), and ASGE (founded 1941) selecting 4, 3, 3, and 5 women presidents, respectively, since their inception. Regarding UIMs, only the AASLD has had a president from an underrepresented group24,25, and thus the improved leadership representation for women have not been realized yet for UIMs. Key elements to engage in for diversity within gastroenteology and hepatology include: (a) exposure to the subspecialty at pre-differentiated stages of a career, (b) showcase viability of the subspecialty for a long career, (c) showcase role models for diversity within the subspecialty, (d) have potential mentors available for mentoring, and (e) create “excitement” about the subspecialty in its practice, lifestyle, and happiness of its practioners. The societies have put forth programs to engage potential and committed GIs in the pipeline, with larger efforts for the post-GI training levels. Pre-GI training, the AGA and ASGE co-managed an NIH-funded R25 grant that paired national GI researchers with UIM undergraduate or medical students for summer research. The ACG manages a similar summer program, and also engages high school students located in the DDW host city or at SNMA, LMSA, and AAIP regional or national meetings for hands-on simulation demonstrations25. Society interactions with those who have committed to or are post GI training are designed to launch and enhance the success of practice, continue engagement with members for ideas, provide a forum to showcase the practice and research, engage in political discussion related to the subspecialty, and assimilate groups within the society to highlight needs towards equity of that subgroup, including engaging a diverse membership. Each of the four societies have created both Women and Diversity Committees that are designed to examine all levels of education and practice, publications, as well as potential and member engagement; an expansive directive but important undertaking for single committees to address the entire operations of a society25. The ASGE has combined its prior Members and Diversity Committees, and created Diversity Awards for members doing research related to ethnicity or gender that are selected by the combined committee25. Leadership development with the aim of diversifying future leadership is a stated goal by the societies. The AGA has a Future Leaders Program, and the ASGE has Leadership, Education & Development (LEAD) and GI Organizational Leadership Development (GOLD) programs for women and young GIs in practice, respectively25. All societies have an International Committee to engage and increase international members. It is evident that the four societies want diverse engagement. At present, women make up an average of 25% of membership23, and UIMs are significantly lower. Engagement at the pre-GI training level may need to be more robust to enhance the pipeline for diversity26.

Conclusions

The clinical and academic practice of gastroenterology and hepatology which spans all ages, gender and ethnic/racial make-up groups in the U.S. remains a viable, exciting and long-term career path for the forseeable future. Practitioners within gastroenterology do not reflect the breadth of patient groups cared for, and efforts to approximate the diversity of patients should be a goal of the specialty. Diversity data from medical school training through faculty ranks and clinical practice show a dearth of UIMs with few in the pipeline (Figure 2B). Cultural sensitivity and competency for all gastroenterology practitioners need to be enhanced for our patient compliance and understanding. The U.S. GI societies have over time created Women and Diversity committees to generate approaches for improving the pipeline and cultivating cultural sensitivity in academia and clinical practice. This start by the U.S. GI societies is welcome and will likely need additional direct attention by societal leadership to implement approaches to achieve the desired goal of diverse representation that mirrors the patient population the specialty cares for.

Acknowledgements:

Supported by the United States Public Health Service (R01 CA206010) and the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute of the University of Michigan (to JMC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The work was presented at the 2018 Digestive Diseases Week annual meeting.

Abbreviations:

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease

- ACG

American College of Gastroenterology

- AGA

American Gastroenterological Association

- ASGE

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- GI

gastroenterology

- SNMA

Student National Medical Association

- LMSA

Latino Medical Student Association

- AAIP

Association of American Indian Physicians

- UIM

underrepresented in medicine

- URM

underrepresented minority

- AAMC

Association of American Medical Colleges

- DDW

Digestive Diseases Week

- AI

American Indian

- AN

Alaskan Native

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

- 1.Schmitt CM, Allen JI. View from the top: perspectives on women in gastroenterology from society leaders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2016;45:371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accessible at https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm/.

- 3.Accessible at www.census.gov/population/www/projections/downloadablefiles.html

- 4.Distribution of U.S. population by race/ethnicity, 2010 and 2050. Accessible at https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/slide/distribution-of-u-s-population-by-raceethnicity-2010-and-2050/

- 5.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA 2008;300:1135–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, et al. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski JJ, Gayle JA. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of underserved populations. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1225–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbrook R Diversity in medicine. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1327–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acosta DA, Poll-Hunter NI, Eliason J. Trends in Racial and Ethnic Minority Applicants and Matriculants to U.S. Medical Schools, 1980–2016. Analysis in Brief. November 2017; Volume 17, Number 3 https://www.aamc.org/download/484966/data/november2017trendsinracialandethnicminorityapplicantsandmatricu.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansell DA, McDonald EK. Bias, Black Lives, and Academic Medicine. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1087–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accessible at https://www.aamc.org/data/facts.

- 13.ACGME Data Resource Book. Accessible at: http://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book

- 14.Accessible at https://www.aamc.org/download/360388/data/gastroenterology.pdf

- 15.Imam M Xierali IM, Fair MA, Nivet MA. Faculty Diversity in U.S. Medical Schools: Progress and Gaps Coexist. Analysis in Brief. December 2016; Volume 16, Number 6 https://www.aamc.org/download/474172/data/december2016facultydiversityinu.s.medicalschoolsprogressandgaps.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.AAMC U.S. Medical School Faculty. Accessible at https://www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster/reports

- 17.Association of American Medical Colleges (2018). Full-Time Faculty in Departments or Divisions of Gastroenterology (Excluding Surgery and Pediatrics) by Race/Ethnicity at All U.S. Medical Schools from 2010 through 2017. Unpublished raw data. [Google Scholar]

- 18.http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRFellowship2019.pdf, Element I.C, p. 5, Common Program Requirements (Fellowship) ©2018 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

- 19.“The Rationale for Diversity in the Health Professions: A Review of the Evidence U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions”, October 2006. https://www.pipelineeffect.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/diversityreviewevidence.pdf

- 20.Fang X, Francisconi CF, Fukudo S, Gerson MJ, Kang JY, Schmulson WMJ, Sperber AD. Multicultural Aspects in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology 2016;150:1344–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betancourt J, Green A, Carrillo J, et al. Cultural Competence in Health Care: Emerging Frameworks and Practical Approaches. The Commonwealth Fund Field Report, October 2002. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2002_oct_cultural_competence_in_health_care__emerging_frameworks_and_practical_approaches_betancourt_culturalcompetence_576_pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashktorab H, Brim H, Kupfer SS, Carethers JM. Racial disparity in gastrointestinal cancer risk. Gastroenterology 2017;153:910–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lok A, Burke CA, Crowe SE, Woods KL. Society leadership and diversity: hail to the women! Gastroenterology 2017;153:618–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/leevy-carroll-m-1920.

- 25.Accessible at: https://www.aasld.org; https://www.gastro.org; https://gi.org; https://www.asge.org

- 26.Carethers JM. Facilitating minority medical education, research, and faculty. Dig Dis Sci 61:1436–1439, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]