Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the feasibility of a novel positron emission tomography (PET) system that provides near real‐time feedback to an operator who can interactively scan a patient to optimize image quality. The system should be compact and mobile to support point‐of‐care (POC) molecular imaging applications. In this study, we present the key technologies required and discuss the potential benefits of such new capability.

Methods

The core of this novel PET technology includes trackable PET detectors and a fully three‐dimensional, fast image reconstruction engine implemented on multiple graphics processing units (GPUs) to support dynamically changing geometry by calculating the system matrix on‐the‐fly using a tube‐of‐response approach. With near real‐time image reconstruction capability, a POC‐PET system may comprise a maneuverable front PET detector and a second detector panel which can be stationary or moved synchronously with the front detector such that both panels face the region‐of‐interest (ROI) with the detector trajectory contoured around a patient's body. We built a proof‐of‐concept prototype using two planar detectors each consisting of a photomultiplier tube (PMT) optically coupled to an array of 48 × 48 lutetium‐yttrium oxyorthosilicate (LYSO) crystals (1.0 × 1.0 × 10.0 mm3 each). Only 38 × 38 crystals in each arrays can be clearly re‐solved and used for coincidence detection. One detector was mounted to a robotic arm which can position it at arbitrary locations, and the other detector was mounted on a rotational stage. A cylindrical phantom (102 mm in diameter, 150 mm long) with nine spherical lesions (8:1 tumor‐to‐background activity concentration ratio) was imaged from 27 sampling angles. List‐mode events were reconstructed to form images without or with time‐of‐flight (TOF) information. We conducted two Monte Carlo simulations using two POC‐PET systems. The first one uses the same phantom and detector setup as our experiment, with the detector coincidence re‐solving time (CRT) ranging from 100 to 700 ps full‐width‐at‐half‐maximum (FWHM). The second study simulates a body‐size phantom (316 × 228 × 160 mm3) imaged by a larger POC‐PET system that has 4 × 6 modules (32 × 32 LYSO crystals/module, four in axial and six in transaxial directions) in the front panel and 3 × 8 modules (16 × 16 LYSO crystals/module, three in axial and eight in transaxial directions) in the back panel. We also evaluated an interactive scanning strategy by progressively increasing the number of data sets used for image reconstruction. The updated images were analyzed based on the number of data sets and the detector CRT.

Results

The proof‐of‐concept prototype re‐solves most of the spherical lesions despite a limited number of coincidence events and incomplete sampling. TOF information reduces artifacts in the reconstructed images. Systems with better timing resolution exhibit improved image quality and reduced artifacts. We observed a reconstruction speed of 0.96 × 106 events/s/iteration for 600 × 600 × 224 voxel rectilinear space using four GPUs. A POC‐PET system with significantly higher sensitivity can interactively image a body‐size object from four angles in less than 7 min.

Conclusions

We have developed GPU‐based fast image reconstruction capability to support a PET system with arbitrary and dynamically changing geometry. Using TOF PET detectors, we demonstrated the feasibility of a PET system that can provide timely visual feedback to an operator who can scan a patient interactively to support POC imaging applications.

Keywords: GPU reconstruction, interactive PET Imaging, point‐of‐ care application, time‐of‐flight PET

Short abstract

1. Introduction

There is an increasing demand for precision medicine in which a doctor takes into account the individual patient's genotypes and phenotypic expressions.1, 2, 3, 4 In addition to the Omics techniques that are becoming an integral part of standard tests for patient care, molecular imaging technologies are also used to provide in vivo evaluation of diagnosis, disease progression, and targeted therapy.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The value of molecular imaging technologies for guiding therapeutic intervention is currently under evaluation in numerous clinical trials for a broad range of diseases.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 In other applications, therapeutic ligands25, 26, 27, 28 are made visible by a variety of imaging technologies in order to verify and quantify therapeutic interventions. As novel molecular theranostic ligands are designed for a wide range of both targets and routes of administration (e.g., intravenous injection, inhalation, intra‐nasal delivery, etc.),29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 the ease‐of‐use and cost‐effectiveness of conventional imaging systems will need to be improved to support these innovations.

Positron emission tomography (PET) provides in vivo measurement of imaging ligands that are labeled with positron‐emitting radionuclides. Traditional PET scanners employ a large number of gamma‐ray detectors arranged in multi‐ring or planar geometry to provide complete sampling and high sensitivity for whole‐body (WB) PET imaging. Although the WB‐PET systems (including PET/computed tomography (CT) and PET/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) can be used to image any PET tracer in patients, they require (a) a large room for installation and (b) transfer of patients to the scanner room. Thus, WB‐PET systems are not the most cost‐effective solution to support the translation of novel PET theranostic ligands. Furthermore, bringing a patient to a scanner is not always feasible. For example, it is difficult to bring a stroke patient from a neurological intensive care unit to a PET/CT scanner to evaluate the patient's brain metabolic activity. Many groups have developed application‐specific PET systems, such as positron emission mammography (PEM)37, 38, 39 or prostate imager,40, 41 but these tend to be optimized for a single purpose and lack the versatility to support a wide range of applications. Another class of positron imagers is designed for intra‐operative or endoscopic applications,42, 43, 44 and although these systems are compact, they have limited three‐dimensional tomographic imaging capability. A compact and versatile PET scanner that can be brought to bedside or a treatment room to support point‐of‐care (POC) imaging applications would be valuable for the deployment of novel molecular theranostic ligands currently under development as well as radiotracers already approved for clinical use.45, 46

We investigated the feasibility of a compact PET scanner that can provide essential three‐dimensional tomographic imaging capability to support novel molecular theranostic applications in a POC setting including bedside, operating room, or an emergency ambulance using generator‐based PET tracers.47, 48, 49, 50 This technology is not meant to compete with clinical PET scanners that are optimized for WB‐PET imaging applications. Instead, it is designed to image a user‐selected region of interest (ROI) in a patient. Different from other organ‐specific PET scanners that are optimized for a specific body part, the proposed technology is designed to provide maximal flexibility and versatility. One unique feature of this PET technology is its ability to provide near real‐time feedback to an operator who can scan a patient interactively. For conventional PET imagers, an imaging protocol is optimized based on the size of the imaging field of view (FOV) (e.g., whole‐body, brain, or heart), the type of radiopharmaceutical, the amount of radioactivity in the target region(s), or a patient's body weight. Once defined, the image protocol is executed without interruption. In contrast, ultrasound (US) imaging is often carried out interactively by an operator who maneuvers an US sensor to collect images in real‐time until the desired imaging task is completed. This interactive imaging strategy was not originally used for PET imaging partly because of technical issues such as (a) nuclear imaging techniques require longer acquisition time (when compared to US imaging) to collect sufficient number of counts for image formation; (b) tomographic image reconstruction requires significant computation time which prohibits real‐time feedback; (c) changing the system geometry during a scan further complicates the system model and extends the image reconstruction time. Recent advances in PET technologies (such as time‐of‐flight (TOF) PET detectors) and computational resources (such as graphic processing unit (GPU)) offer opportunities to address these obstacles and create a new class of PET imager that may enable innovations in molecular theranostics.

The proposed POC‐PET system consists of a maneuverable PET detector panel that works in conjunction with a second PET detector panel placed on the opposite side of a patient to detect annihilation gamma‐rays from the patient's body. The second PET detector panel can be stationary behind the patient or move synchronously with the maneuverable panel such that the center of both panels always faces the center of the ROI. An operator controls the first detector panel (or together with the second panel) by freehand or a robotic arm, depending on the implementation, to collect data from multiple locations and angles around the desired ROI. A tracking system automatically registers the location and orientation of the PET detector and feeds the information into the list‐mode data stream. A fast image reconstruction engine reads in the coincidence events along with detector information to perform list‐mode image reconstruction using a simplified system matrix computed on‐the‐fly based on the dynamically changing detector location and orientation. As the data are continuously being collected and reconstructed, an updated version of images is displayed on a screen in near real‐time. With this visual feedback, an operator can interactively adjust the detector location and orientation, as well as the imaging protocol, to collect as much or as little data as needed in order to achieve the desired image quality. When sufficient angular sampling and counting statistics are obtained through the user‐controlled trajectory and pace, the operator has visual confirmation of usable images on the screen before halting the acquisition. The recorded data can be reconstructed off‐line later using more sophisticated algorithms and/or a more accurate system matrix to further improve the image quality.

As an operator moves the detector panel around a patient's body, coincidence data may only be collected from selected angles that are constrained by a chair or a bed. It has been demonstrated51, 52 that, in a limited angle PET scanner, TOF information can reduce artifacts in the reconstructed images caused by missing data. Therefore, detectors that have good timing performance are critical to the proposed POC‐PET system in order to compensate for the incomplete sampling and to produce artifact‐free ‐images.

In this paper, we first describe a fast list‐mode image reconstruction framework with TOF reconstruction capability that will enable near real‐time feedback to an operator and support interactive PET imaging operations. We constructed a prototype device to demonstrate the feasibility of a user‐maneuverable, limited‐angle PET system. We also conducted extensive Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate, considering the computation time and image quality, the potential performance and limitations of a POC‐PET system using the interactive imaging strategy.

2. Materials and methods

2.A. Fast image reconstruction framework

The proposed POC‐PET system is designed to provide timely visual feedback to an operator who can interactively scan a patient to achieve the necessary image quality for a desired imaging task. To realize this goal, a fast image reconstruction framework is essential. One of the major computational expenses in image reconstruction is the calculation of the system matrix which can either be pre‐computed or on‐the‐fly. The pre‐computed system matrix allows one to model physical processes more accurately at the expense of computation complexity.53, 54, 55, 56 However, with the proposed interactive scanning strategy, the system geometry is not only patient‐specific but also dynamically changing during a scan. Therefore, the system matrix computation has to keep up with the dynamic scanning operation. Recently, GPU technology was used to accelerate the image reconstruction with promising results.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 For on‐the‐fly system matrix computation, a simplified physics model is often used to fully utilize the massive parallel structure of GPU.57, 58 This approach works well for list‐mode image reconstruction in which response function is calculated for one line‐of‐response (LOR) at a time. Therefore, we implemented a GPU‐based, fully three‐dimensional list‐mode TOF maximum likelihood expectation‐maximization (ML‐EM) image reconstruction algorithm with the system matrix computed on‐the‐fly to support PET systems with arbitrary geometry that may also change dynamically during a scan.

2.A.1. Image reconstruction for PET systems with dynamically changing geometry

Assuming that an operator positions the detector panels at a finite number of locations to scan a patient, we modified the data model of conventional PET image reconstruction slightly to account for the potentially different acquisition times when detectors are at different locations. We use the subscript d = 1, 2,…, N to represent a series of N discrete locations of the POC‐PET detectors. The radioactivity concentration within a voxel is modeled as , where j = 1, …, J (number of voxels). We consider all to be time invariant throughout the scanning procedure. For radionuclides with short half‐lives, we may need additional decay correction to individual data sets. Within the d‐th scanning location, the total number of radioactive decays from a voxel is approximated by a Poisson random variable with its mean equal to , where denotes the time duration for which the maneuverable detector is located at this position. We use to describe the TOF PET detector response function (system matrix), where t denotes TOF bins and i denotes LOR. Considering that the measurements of each LOR at different locations are independent, the image reconstruction task is to minimize the objective function, the negative log‐likelihood, or equivalently the I‐divergence.62 To control the discontinuity in the images associated with the limited sampling angle of the POC‐PET system, we also include a smoothness penalty to the objective function in our image reconstruction framework:

| (1) |

where the parameter controls the overall balance between the data fitting term and the penalty term. The choice of function f affects the behavior of smoothness. For example, the Huber type loss functions are widely used since they smooth out the unwanted noise but preserve transitions in sharp edge areas.63 When we choose function f(x) = logcosh(x) which has a Huber type behavior for computational efficiency, the parameter controls the transition between linear region and quadratic region of the penalty term. When we set β = 0, the penalty function is turned off and the images are reconstructed without regularization.

By using convex decomposition on the log‐sum term, we can form an alternating minimization algorithm:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Here, is the backward projection of the ratio between data and estimated mean, k denotes iteration and m is the index for list‐mode events. As random and scatter counts are also dependent on the location of the moving detectors, denotes the random and scatter counts for the LOR corresponding to the m‐th event at the d‐th location. is the time‐weighted sensitivity image. The estimation of random counts may or may not be available in real‐time (depending on the hardware implementation), but can be estimated off‐line along with scatter estimation. Nevertheless, it is included here for completeness. The time duration at different detector locations needs to be known before the list‐mode data acquired at the particular location can be used for image reconstruction because it affects the sensitivity image term . This requirement could be a speed limiting factor for image reconstruction, but can be avoided by forcing the image reconstruction to start after a fixed amount of time has passed at each location (e.g.,‐ 60 s). On the other hand, if detectors are moved continuously, the computational time for Eq. (4) will be much longer than data acquisition (DAQ) time at each detector location. Therefore, a discrete number of detector locations is preferred in order to minimize the computation time and to provide near real‐time feedback through reconstructed images.

The penalty term is also decoupled using convex decomposition:

| (5) |

where and are the pixel values at voxel j and of the previous iteration, respectively.

Note that when we put (5) in (2), all the sums are over individual image voxels thus giving us an element‐wise updating equation. The decoupled penalty allows us to solve the maximization step using Trust Region Newton's method64 on each individual voxel. This greatly reduces the computation and allows us to easily parallelize the entire image volume computation over a large number of individual threads.

The most computationally intensive part is the calculation of and . The calculation of requires a full backward projection of all LORs for each detector position including data correction items such as attenuation correction and normalization factors. For systems with large geometry, the computation time of may become a limiting factor for providing real‐time feedback. The calculation of requires a full forward projection and a full backward projection over all list‐mode events. Therefore, a fast forward and backward projector is critical for providing real‐time feedback to support the proposed interactive operation.

2.A.2. GPU implementation

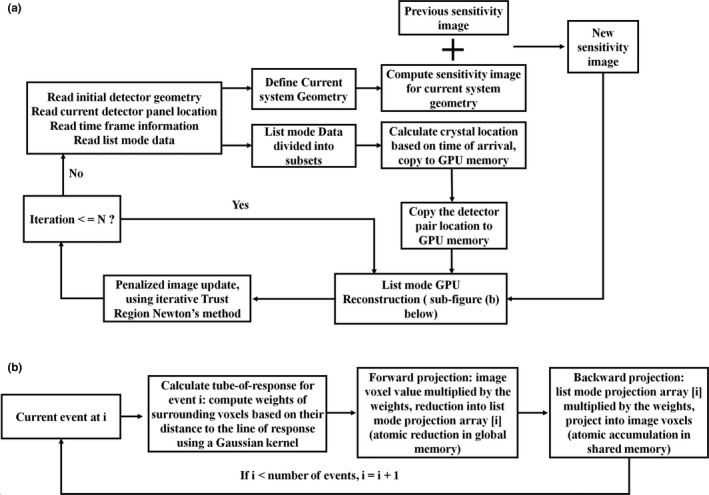

We implemented our list‐mode ML‐EM algorithm on GPU using Nvidia compute unified device architecture (CUDA) programming model for fast image reconstruction. Figure 1 shows the structure and workflow of the reconstruction platform. At each detector panel location, the system geometry is defined by (a) a static detector geometry file in which the crystal locations within the detector panel are defined; (b) a panel location matrix that includes a vector that points to the center of the detector panel and three normal vectors of the detector panel surfaces that describe the orientation of the panel detectors; (c) an absolute time stamp when the detector panels are moved to their current locations, and (d) a time duration within which the detector panels remain static. With this information and the actual arrival time of a list‐mode event, the location of the LYSO crystal pair associated with each coincidence event can be calculated and sent to GPU to compute the system matrix for image reconstruction. To support the interactive scanning operation, initial image reconstruction can start as soon as the acquisition at the first detector location is completed and the detector panels are moved to a new location. The image reconstruction will stop after a pre‐defined number of iterations (N = 10 in this work). When the subsequent DAQ is complete, the new panel location and time information are appended to data files in items (2), (3), and (4) above. The newly acquired list‐mode events are also appended to the existing list‐mode data file. The sensitivity image is recomputed using the new system geometry. Previously reconstructed images are used as the initial value to start a new round of image reconstruction using all list‐mode events acquired thus far. This process repeats until an operator halts the acquisition. At this time, the images will be reconstructed with additional iterations to optimize the image quality.

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of the fully 3‐D GPU‐based list‐mode image reconstruction workflow. The PET detector trajectories are modeled as a series of static positions during the scan. Current system geometry is computed from the initial detector geometry and the current locations of detector panels. Sensitivity image of current system geometry is computed and added to the previous sensitivity image for image reconstruction using all list‐mode events acquired so far. Using the arrival time of each event and the time frame information of each panel location, the crystal positions of each coincidence event are calculated and sent to GPU memory for list‐mode image reconstruction. The image reconstruction will stop after a pre‐defined number of iterations (N = 10 in this work). (b) Flowchart showing list‐mode GPU reconstruction kernel.

To achieve faster speeds and also to fit the massive parallel GPU architecture, a spatial variant Gaussian function was used as the projection kernel to compute the geometric detector response matrix.57, 58 The system matrix was calculated using a tube‐of‐response (TOR)57, 58 approach to provide more flexibility for accurately modeling the system response. The calculation of the projection kernel involves two steps: computing the distance r between the center of a voxel to the line‐of‐response (LOR, connecting the two crystals in coincidence) and computing the weighting function f(r). In our method, we used a Gaussian function shown below to calculate the weight.

| (6) |

where r is the distance from a voxel to the LOR defined by a list‐mode event. is determined by the intrinsic spatial resolution of the system. The intrinsic spatial resolution is determined by the crystal size in the detectors and is assumed to be spatially invariant along the LOR if the detectors in the front and back panels are of the same size. For POC‐PET systems that employ detectors of different sizes in the front and back panels, the intrinsic spatial resolution becomes spatially variant and can be estimated from the crystal sizes and object‐to‐detector distances.65

Time‐of‐flight information is incorporated as an independent Gaussian kernel applied along the direction of the LOR of each event. In the kernel function, l denotes the distance from the voxel center to the center of this Gaussian kernel (TOF center) and denotes the error of the localization of the source. The TOF center is determined by the time difference while its is determined by the CRT of the PET detectors which can be estimated from the quadratic sum of individual detectors’ timing resolution: when the detectors’ timing spectra are Gaussian shaped. The corresponding Gaussian kernel used for reconstruction will be CRT × c / 2 (FWHM), where c is the speed of light.66 In the forward and backward operators, the weights (system matrix) along an LOR are multiplied by this Gaussian kernel; therefore, voxels far away from the TOF center receive little weight.

During forward projection, backward projection, and image update, a group of voxels are simultaneously assigned to different blocks of GPU threads. While within each block, threads loop through all list‐mode events. In forward projection, voxel values are projected to be stored sequentially in the same order as list‐mode events. This increases the memory access speed because coalesced reading and writing operations are achieved. In backward projection, the matched LOR‐driven approach takes advantage of coalesced addressing at the cost of memory writing conflicts in image space. However, these conflicts can be handled by hardware atomic operations in newer generations of GPU devices.67, 68

To further improve the image reconstruction speed, a multi‐GPU approach is used to simultaneously perform the most computationally intensive projections. List‐mode events are divided into different groups and transferred to different GPUs while each GPU keeps a copy of the current iteration of image volume. After one complete forward and backward projection, a global reduction is performed to sum the entire updated image together. After the image update step is finished on a single GPU, the new image volume is then distributed to all GPUs for subsequent iterations of projections.

Our current implementation of the above reconstruction uses prompt events only. Random and scatter events are either pre‐corrected for the experimental data or not included for the simulation study. It also does not compute the normalization term in real‐time. Random coincidences can be estimated by delayed coincidences or block singles rates using hardware as done by several PET scanner manufacturers. This will allow the random correction to be carried out in real‐time as part of the GPU image reconstruction. Scatter correction may be implemented off‐line as part of the final image reconstruction. While this may limit the quantitative accuracy of the images reconstructed in near real‐time, it should not significantly impact the quality of the images providing visual feedback to an operator for the purpose of interactive scanning. The implementation of complete data correction algorithms is beyond the scope of this work and will be left for future studies. We implemented the image reconstruction code on four Nvidia GTX Titan (Maxwell) graphics cards. The three‐dimensional reconstructed volume as well as the image voxel size of this reconstruction software is user selectable.

2.B. A proof‐of‐concept POC‐PET prototype

2.B.1. System description

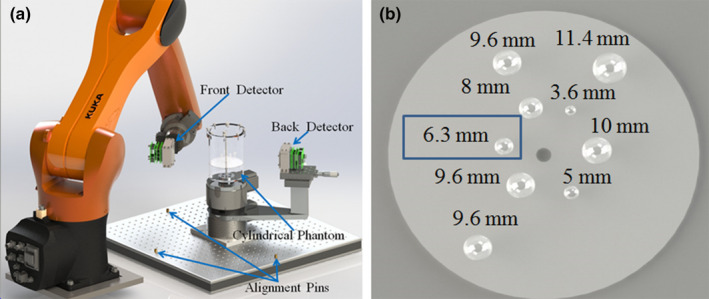

We constructed a proof‐of‐concept prototype device using two typical PET block detectors, as shown in Fig. 2(a). One detector is attached to a rotation stage that is mounted on an optical table. The second detector is mounted to a robotic arm69 (Kuka, KR10R‐11000 sixx) that has six degrees of freedom. Within its reach, the robotic arm can position the detector at arbitrary locations and orientations relative to the first PET detector to collect coincidence events.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic drawing of the prototype POC‐PET system; (b) Illustration of the sizes and distribution of the spherical tumor inserts in the cylindrical phantom. The 6.3 mm tumor highlighted in a blue box is the one that was accidentally filled with air bubbles. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Each of the two block detectors is made of a lutetium‐yttrium oxyorthosilicate (LYSO) crystal array and a Hamamatsu H8500 position sensitive photo multiplier tube (PS‐PMT). The LYSO crystal array consists of 48 × 48 crystals each measuring 1 × 1 × 10 mm3. The array is coupled to the PMT via room temperature vulcanization (RTV) optical glue (RTV615A by Momentive, Newark, OH and RTV615B by GE Silicones, Huntersville, NC). The crystal array and PMT are covered by 0.1 mm thick aluminum foil with black coating (Thorlabs Inc, Newton, NJ, USA) to make the detector lightproof. Custom holders were fabricated to mount the PET detectors on the robotic arm and the rotational stage.

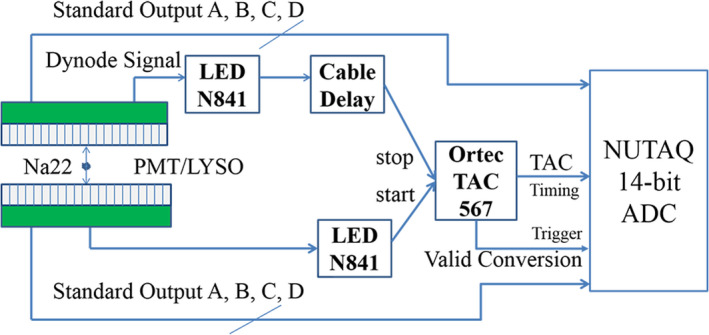

2.B.2. Data acquisition system

The front‐end readout electronics are based on discrete components to multiplex the 64 anode signals of the H8500 PMTs to four position‐encoded signals.70 The multiplexed signals are fed into charge sensitive amplifiers followed by a two‐stage Sallen‐Key filtering circuit. The filtered signals are digitized by a DAQ system (Nutaq Perseus 6010, Quebec City, QC, Canada) with 32 channels of 14‐bit analog‐to‐digital converter at a sampling rate of 125 MHz over ±1.25 V input range.

Coincidence detection was established using a time‐to‐amplitude converter (TAC, ORTEC 567). The last dynode signals of both PMTs were fed into a leading edge discriminator (LED, ORTEC N841). One LED output was connected to the start of the TAC while the other LED output was connected to the stop of the TAC via a long cable to introduce a 10 ns delay. The TAC output was digitized to measure the difference in arrival time of two gamma‐rays detected by the two block detectors. The Valid Conversion signal of the TAC was used to trigger the DAQ system to record the event. Figure 3 shows the setup of the DAQ system.

Figure 3.

The DAQ architecture of the prototype system. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.B.3. Detector characterization

To characterize the CRT, energy resolution, and crystal resolving capability of the prototype system, we first filled a flat plastic chamber with an inner dimension of 60 × 40 × 1.5 mm3 with 64Cu solution to construct a small plane source. The plane source was centered between the two PET detectors (150 mm apart). Using the setup described by Fig. 3, 18.4 million coincidence events were collected. Events were sorted based on the location of interaction within the block detectors to form two flood images. Detector lookup tables were manually created for crystals that can be clearly delineated in the flood images. Energy spectra of individual crystals were measured to create energy lookup tables that define the 511 keV photo peak location (in the unit of ADC output value) for each crystal identifiable in the flood images. The average energy resolution for 511 keV photo peak was calculated among all identifiable crystals in the block detectors. Timing spectra of individual LOR among all identifiable crystals in the two detector blocks were also measured to estimate the CRT. The deviation between the center of each timing spectrum and the delay introduced by the delay cable defines the timing offset for the corresponding LOR; this value was stored in a timing lookup table for each LOR. The three lookup tables (crystal ID, photo peak location, and timing offset) are used to (a) identify the crystal IDs of each coincidence event, (b) apply energy discrimination, and (c) correct for timing offset before images were reconstructed.

2.B.4. Phantom imaging

We performed an imaging study of a small cylindrical phantom using the prototype system, as shown in Fig. 2(a). The cylindrical phantom has an inner dimension of 102 mm in diameter and 150 mm in height. Nine spherical tumors of different diameters were placed in the phantom. Figure 2(b) shows the sizes and distribution of the spherical sources. The cylindrical phantom was filled with 64Cu solution with an activity concentration of 29.7 kBq/ml, which is equivalent to 5.3 kBq/ml of 18F (roughly equivalent to 370 MBq of radioactivity uniformly distributed in a 70 kg person). The choice of 64Cu over 18F for this experiment is due to the longer half‐life of the 64Cu (12.7 h) that permits us to image the phantom over a longer period of time. The radioactivity concentration in the spherical tumors was eight times of that of the background concentration.

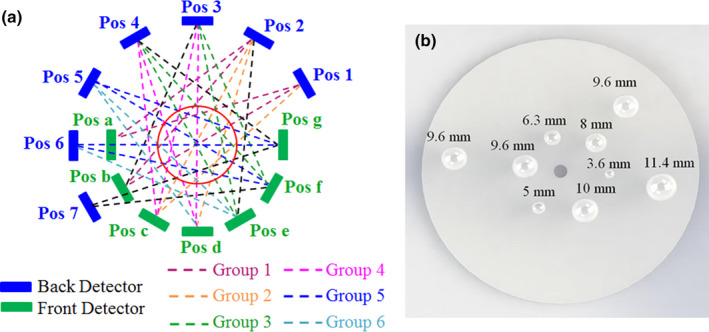

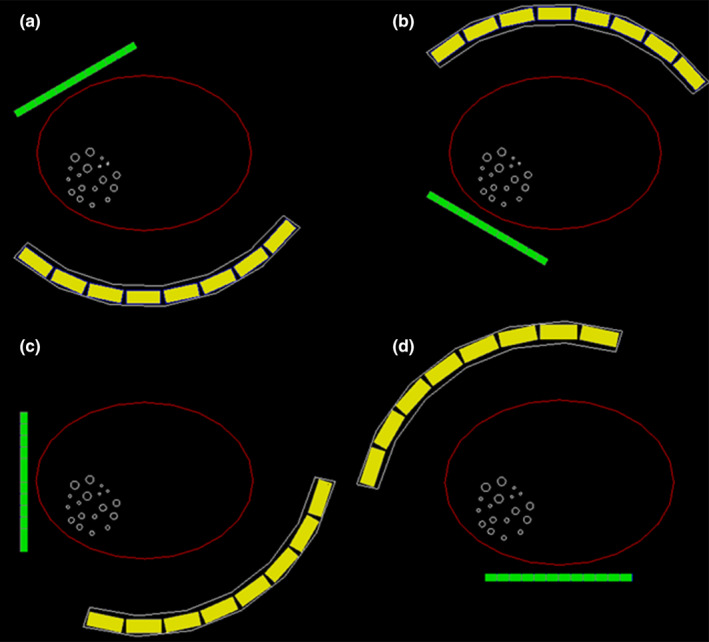

We used the robotic arm and the rotation stage to independently move the front and back detectors to seven different locations as illustrated in Fig. 4(a). Constrained by the reach of the robotic arm and the bench space around the experimental setup, we collected coincidence events from a total of 27 sampling angles for 5 min per angle. The sampling angles between detector pair locations are illustrated by the dash lines in Fig. 4(a).

Figure 4.

(a) An illustration showing the locations of the two PET detectors and the sampling pattern used to image the cylindrical phantom. The blue block denotes the back detector while the green block denotes the front detector. The red circle represents the cylindrical phantom. The coincidence events were acquired at 27 angles by placing both the front and back detectors at seven different positions, as illustrated in dashed line (of all colors); (b) The distribution of nine spherical tumors simulated in the Monte Carlo study. The tumors were each placed at the center slice of the cylindrical phantom. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

List‐mode events were reconstructed based on the flowchart in Fig. 1 first without the TOF information and secondly using TOF information based on the CRT of the system as characterized in the previous section. It should be noted that despite the support of regularization in our image reconstruction framework, all images shown in this work were reconstructed without smoothness penalty (i.e., β = 0 in Eq. (1)) because the choice of regularization parameters significantly impacts the image quality especially when the counting statistics is limited. As a result, we compare non‐regularized images from various system configurations in order to simplify the comparison. The choice of regularization function and the optimization of its parameters are left for future studies.

2.C. Monte Carlo simulation of POC‐PET systems

2.C.1. Simulation of the proof‐of‐concept prototype

We used GATE71 to simulate the above prototype system to evaluate the effect of detector CRT on image quality of POC‐PET systems. The system setup and sample angles in the simulation study were the same as those in Fig. 4(a) except that the front and back detectors are made of an array of 38 × 38 LYSO crystals of 1 × 1 × 10 mm3 each. This is because only the central 38 × 38 LYSO crystals in the prototype device can be clearly delineated [explained in Fig. 6(a) and 6(b)]. Thus, only gamma‐rays detected by these central crystals were used for image reconstruction in the imaging experiments. For consistency, we only simulated block detectors that are made of 38 × 38 LYSO crystal arrays in the GATE studies. The spherical tumor sizes and distribution in the Monte Carlo study were illustrated in Fig. 4(b). Additional system parameters include: (a) energy resolution: 15% FWHM at 511 keV; (b) energy window: 435–650 keV; and (3) CRT: 100, 300, 500, or 700 ps FWHM. The object imaged is defined based on the actual phantom using the following parameters: (a) diameter: 102 mm; (b) height: 150 mm; and (c) material: water. Radioactivity concentration in the background (5.3 kBq/ml of 18F) and the tumor‐to‐background ratio (8:1) are the same as the actual experiment.

We collected coincidence events from the same 27 sampling angles for 5 min each. Coincidences were sorted off‐line using a customized C code with a time window of 4.5 ns. List‐mode events were reconstructed based on the flowchart in Fig. 1 first without the TOF information and subsequently using TOF information from POC‐PET systems that have CRTs of 700, 500, 300, and 100 ps FWHM, as simulated in GATE.

2.C.2. Interactive scanning strategy

To evaluate the proposed interactive scanning strategy, we regrouped the list‐mode data from a simulated POC‐PET system with a CRT of 300 ps FWHM to mimic a POC‐PET system that has two detector panels that each contains two PET block detectors. Of the 27 sampling angles simulated, 22 of them are subdivided into six groups, as illustrated in Fig. 4(a) using color‐coded dashed lines. The number of coincidence events in these six groups was 50.5, 49.6, 50.3, 50.4, 51.3, and 16.8k, respectively. It should be noted that there are only three sampling angles in Groups 2 and 6. We first reconstruct list‐mode events from Group 1 as if this is the data acquired from the first scanning angle. Subsequently, we reconstructed images by adding one more group of events at a time following the sequence of 1→5→3→6→4→2 until we used all six groups of events for image reconstruction.

These reconstructed images represent the near real‐time visual feedback that an operator can receive using the proposed interactive scanning strategy. Based on the visual feedback, the operator can adjust the detector position to collect additional data and enhance the image quality. When the image quality becomes adequate for making a diagnostic decision, the operator can stop the scan and data acquisition.

2.C.3. Simulation of a large POC‐PET system for body imaging

Simulation of a torso phantom (316 × 228 × 160 mm3) was carried out using a POC‐PET system with more detector blocks to enhance the overall system sensitivity. The system is consisted of two detector panels. The front panel comprises 4 × 6 PET detector modules each made of 32 × 32 LYSO crystals (1 × 1 × 10 mm3 each). The back panel is consisted of 3 × 8 PET detector modules each made of 16 × 16 LYSO crystals (3.2 × 3.2 × 20 mm3 each). These 24 modules are arranged in three partial rings of 27.5 cm in radius. Additional system parameters include: (a) energy resolution: 15% FWHM at 511 keV; (b) energy window: 435–650 keV; and (c) CRT: 250 ps FWHM. Derenzo pattern spherical tumors with diameters of 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 mm are placed inside the torso phantom at the center slice. The phantom is imaged from four different angles as shown in Fig. 5. Radioactivity concentration in the background is 5.3 kBq/ml of 18F and the tumor‐to‐background ratio is 8:1.

Figure 5.

Scanning strategy when imaging a body‐sized phantom using a large POC‐PET system. (a) scanning angle 1; (b) scanning angle 2; (c) scanning angle 3; (d) scanning angle 4. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Coincidence events were acquired for 100 s from each of the four angles. To evaluate the feasibility of the proposed interactive scanning strategy under clinical scenarios, we firstly reconstructed list‐mode events from angle 1 only. Subsequently, we reconstructed images by adding events from one additional sampling angle at a time following the sequence of 1→2→3→4 until we used all events for image reconstruction. Contrast recovery coefficient (CRC) was calculated for each spherical tumor in the torso phantom for all four reconstructed images for comparison. Count density, in the i‐th tumor was estimated by drawing a spherical ROI over the center of the tumor and then calculating the mean number of counts in the ROI. The size of each ROI is the same as the corresponding tumor size. The background count density, was determined as the mean number of counts in a square ROI drawn over the torso phantom from ten adjacent slices. The for i‐th sphere was calculated according to the NEMA NU2–200172 definition:

| (7) |

where uptake is 8 in this study. The CRC is described as an average of the tumors of the same diameter.

3. Results

3.A. Proof‐of‐concept POC‐PET prototype

3.A.1. Detector characterization

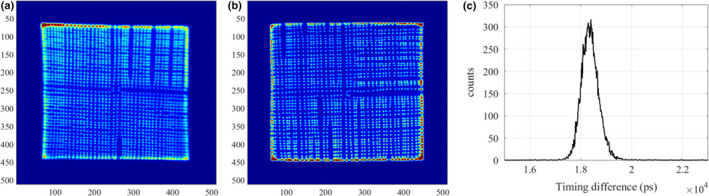

Figure 6(a) and 6(b) show the flood images of two block detectors in the prototype POC‐PET system. In both images, only the central 38 × 38 crystals out of the 48 × 48 LYSO crystal array can be clearly resolved. As a result, only gamma‐ray interactions in the central 38 × 38 crystals were included for coincidence detection and image reconstruction.

Figure 6.

(a) Flood image of the front detector; (b) Flood image of the back detector; (c) Timing spectrum of the central crystals (4‐by‐4) of the front detector against the entire back detector. The measured CRT was around 740 ps FWHM. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 6(c) shows the coincidence timing spectrum between the two PET detectors. The CRT was approximately 740 ps FWHM for the central crystals (4‐by‐4) in the front detector against the back detector. The energy resolution averages ~15% FWHM at 511 keV.

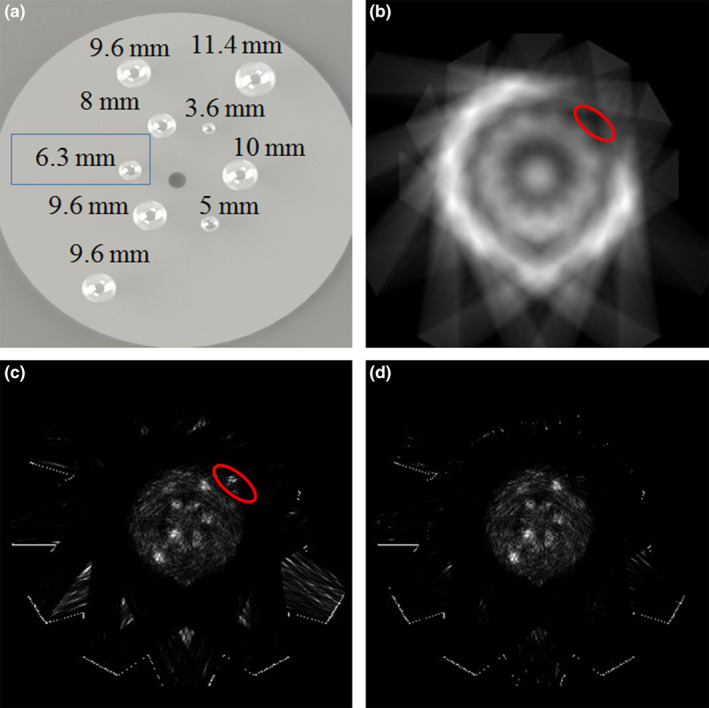

3.A.2. Phantom imaging

Using the 27 sampling angles defined in Fig. 4(a), the sensitivity image of the prototype POC‐PET system is shown in Fig. 7(b). This image clearly demonstrates that the sensitivity of the POC‐PET system is most likely non‐uniform due to limited angular samples and large gaps between adjacent detector locations. Figure 7(c) shows images reconstructed without TOF information. There are visible artifacts due to insufficient sampling. More importantly, there is a hot spot (highlighted by the red circle) outside of the cylindrical phantom where the system sensitivity is low [also highlighted in Fig. 7(b)]. This artifact is likely the result of overcompensation of low sensitivity which amplified contributions from random and/or scattered events. In contrast, Fig. 7(d) shows images reconstructed with TOF information. Despite the relatively poor coincidence timing performance (CRT = 740 ps FWHM), TOF information significantly reduced artifacts in the reconstructed images. A tumor, 6.3 mm in diameter, was not visible in the images [Fig. 7(c) and 7(d)] due to an operator error that led to trapped air bubbles when filling the tumor with radioactivity.

Figure 7.

(a) Illustration of the sizes and distribution of the spherical tumor inserts in the cylindrical phantom; (b) Sensitivity image of the prototype POC‐PET system; (c) Image of a cylindrical phantom containing nine spherical tumors with 8:1 tumor‐to‐background radioactivity concentration, reconstructed without TOF information; (d) Image reconstructed with TOF information. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

It should be noted that there are roughly 320,000 coincidence events from the 27 sampling angles. The image reconstruction time is approximately 48 s for a total of 10 iterations using the GPU‐based list‐mode TOF‐PET reconstruction codes.

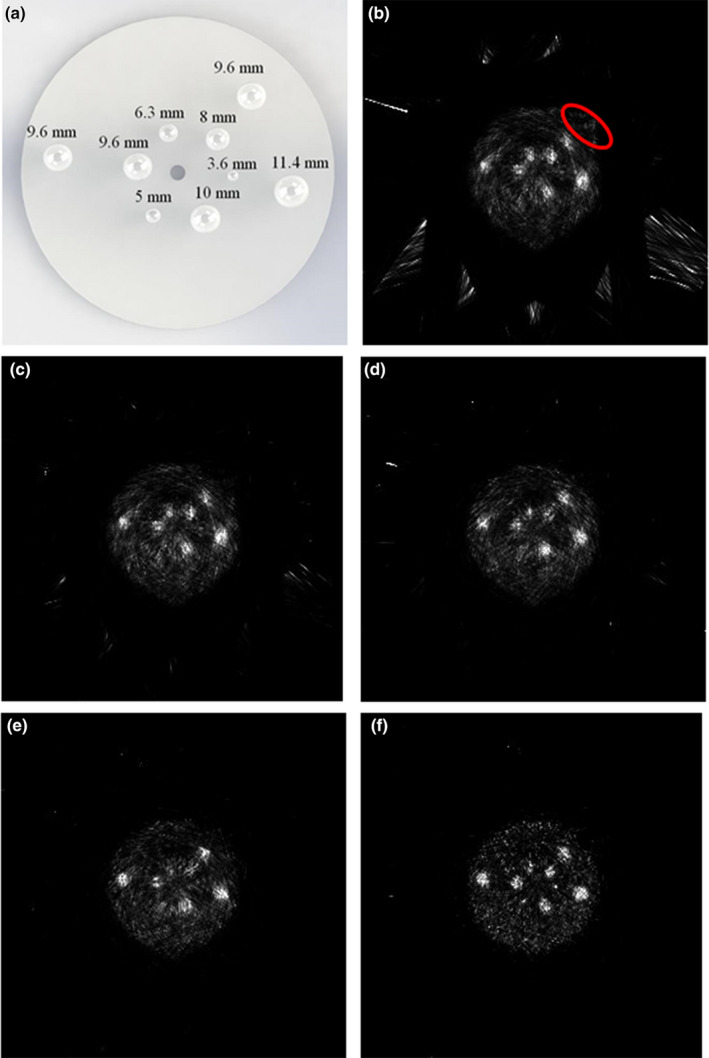

3.B. Monte Carlo simulation of the proof‐of‐concept POC‐PET prototype

Coincidence events from the five POC‐PET systems simulated by GATE were reconstructed by the same GPU‐based list‐mode TOF‐PET reconstruction codes. Results are shown in Fig. 8. From left to right and from top to bottom, the figures are the distribution of nine spherical tumors simulated in the Monte Carlo studies for reference and images reconstructed without TOF information, and when detector CRT was 700, 500, 300, and 100 ps FWHM, respectively. Similar to the experimental results, images reconstructed without TOF information exhibit artifacts due to insufficient sampling and non‐uniform sensitivity. When images are reconstructed with TOF information, artifacts are significantly reduced even with the limited TOF‐PET performance from detectors with CRT = 700 ps FWHM. As expected, POC‐PET systems that are constructed using detectors with faster timing performance (such as those with CRT = 300 ps or 100 ps FWHM) can produce better image quality using the same sampling angles. Alternatively, these systems may produce usable images with fewer number of sampling angles to further reduce the total acquisition time and to improve usability. These potential benefits will require further validation through appropriate Monte Carlo simulation studies in the future. It is worth noting that the 3.6 and 5 mm lesions are clearly visualized in and only in the image with a detector CRT of 100 ps FWHM. This finding warrants further exploration of the benefits of exceptional CRT performance in image quality and lesion detectability in the future.

Figure 8.

Images of the cylindrical phantom measured by the simulated POC‐PET systems. (a) The distribution of nine spherical tumors in the phantom simulated in the Monte Carlo study Images were reconstructed (b) without the TOF information or with a detector CRT of (c) 700 ps FWHM; (d) 500 ps FWHM; (e) 300 ps FWHM; and (f) 100 ps FWHM. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The number of events used for the reconstruction was around 320,000, similar to that from the experimental setup. The reconstruction time is proportional to the number of list‐mode events. To process the image in a 600 × 600 × 224 mm3 voxel rectilinear space, with each voxel a 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 cube, we observed a reconstruction speed of 0.96 × 106 events/s/iteration. Considering the data collection time at each sampling angle was 5 min, the reconstruction speed is fast enough to provide timely visual feedback as data are acquired.

3.C. Interactive scanning strategy

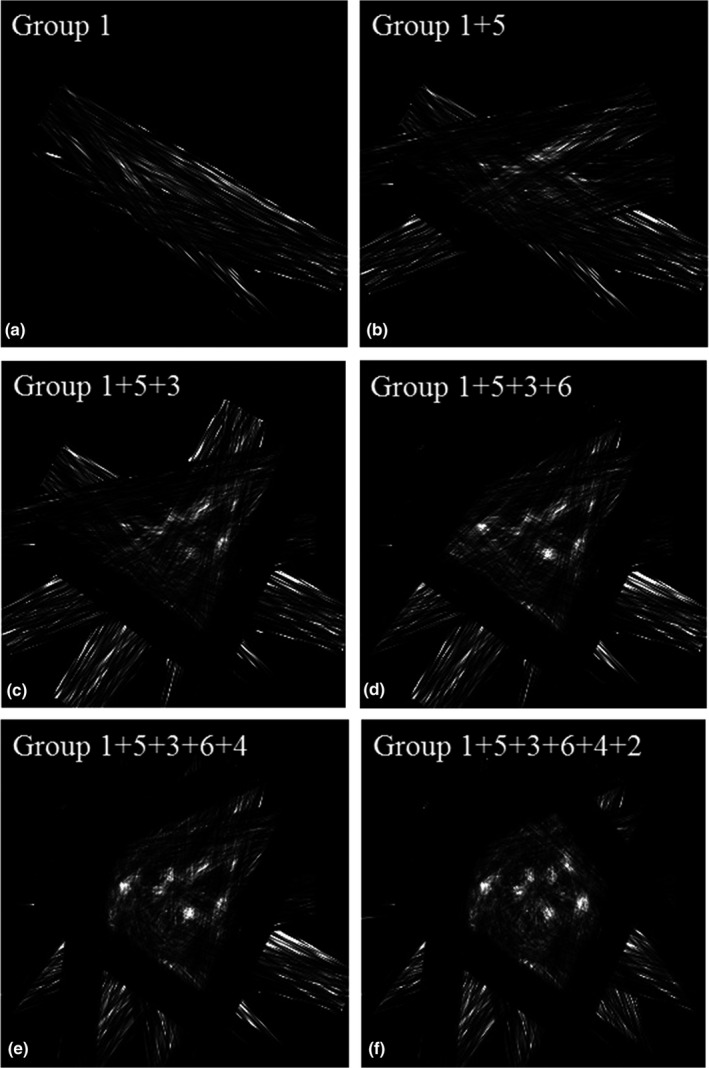

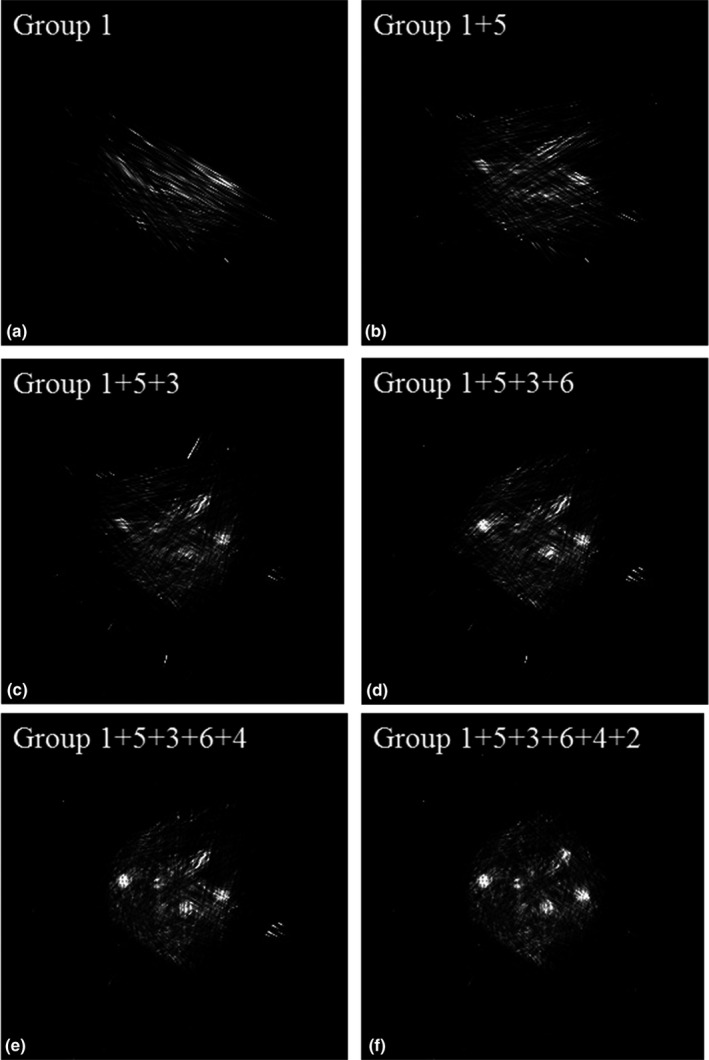

By gradually adding one more group of list‐mode data at a time for image reconstruction, we reconstructed six images following the sequence in Section 2.D. Figure 9 shows the images reconstructed without TOF information, while Fig. 10 shows the corresponding reconstructed images when the detector CRT is 300 ps FWHM.

Figure 9.

Images reconstructed without TOF information using different numbers of groups of data.

Figure 10.

Images reconstructed using different numbers of groups of data when the detector timing resolution was 300 ps FWHM.

Images reconstructed with TOF information clearly show fewer artifacts which allow us to better identify tumors in the phantom that has background activity. The tumors in the phantom can be gradually identified by adding more list‐mode data. A comparison of the images with and without TOF information reveals that four or five groups of data are enough to get a useful image when the detector CRT is 300 ps FWHM while a larger amount of angular sampling is required to achieve reasonable image quality for non‐TOF systems.

As shown in Table 1, the reconstruction time for the images in Fig. 10 is approximately 65 s each for ten iterations including the time for writing images into files. GPU computation time for data from group 1 is 245 ms/iteration and the time increases to 451 ms/iteration for all six groups of data. The sensitivity image computation time is around 18.7 s/group. The total scan time to get the images in Figs. 9 and 10 is around 30 min when both the front and back detector panels contain two PET block detectors each made of a LYSO crystal array of 38 × 38 × 10 mm3 in dimensions. With bigger detector panels, the scan time can be further reduced to be more compatible with clinical work flow.

Table 1.

Reconstruction time for the images shown in Fig. 10. The overall reconstruction time includes the time used for the calculation of sensitivity image, image reconstruction, reading data files, and writing images into a file. The GPU computation time includes the actual calculation time and data transferring time. Times shown in the table are all for ten iterations of list‐mode TOF‐PET image reconstruction

| Images | Overall reconstruction time | GPU computation time |

|---|---|---|

| Figure 10(a): Group 1 | 62.61 s | 2.45 s |

| Figure 10(b): Group 1 + 5 | 63.46 s | 2.93 s |

| Figure 10(c): Group 1 + 5 + 3 | 64.65 s | 3.38 s |

| Figure 10(d): Group 1 + 5 + 3 + 6 | 64.92 s | 3.74 s |

| Figure 10(e): Group 1 + 5 + 3 + 6 + 4 | 65.17 s | 4.15 s |

| Figure 10(f): Group 1 + 5 + 3 + 6 + 4 + 2 | 65.91 s | 4.51 s |

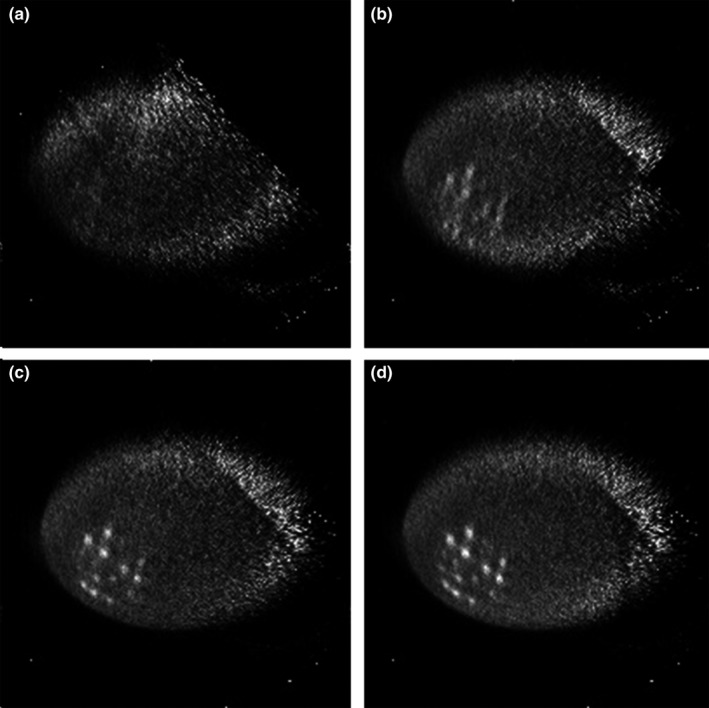

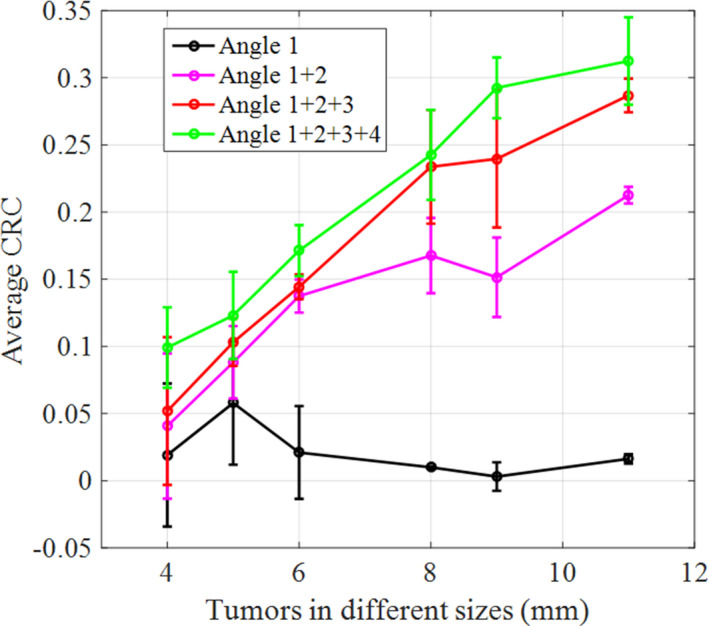

3.D. Simulation of a large POC‐PET system for body‐size phantom imaging

We reconstructed four images (as shown in Fig. 11) following the sequence described in Section 2.C.3. The number of counts used in the reconstruction for the four images are 7.32, 17.31, 23.29, and 33.35 million, respectively. In order to increase the reconstruction speed, we decrease the image volume to be 400 × 400 × 160 mm3, with each image voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. With limited angle tomography, we expected to see and did observe artifacts in the reconstructed images. However, even with a mere three sampling angles and a total DAQ time of 300 s, the image in Fig. 11(c) can still re‐solve most of the tumors. When the number of sampling angles is increased to 4, all the tumors can be clearly identified. Figure 12 shows the calculated average CRC as a function of tumor size. CRC can be improved by employing more sampling angles. With only one sampling angle, it is difficult to re‐solve any tumor in the warm background. When data from a second angle are added, the system starts to identify most of the tumors. The average CRCs were 4.1%, 8.8%, 13.7%, 16.8%, 15.1%, and 21.3%, respectively, for tumors with diameter ranging from 4 to 11 mm in Fig. 11(b). The average CRCs were improved to 5.2%, 10.3%, 14.4%, 23.3%, 24.0%, and 28.7%, respectively, when three groups of data were used for reconstruction as shown in Fig. 12(c). With all four datasets used for reconstruction, the CRCs were 9.9%, 12.3%, 17.1%, 24.3%, 29.2%, and 31.2%, respectively. The sensitivity image calculation time for each sampling angle is 25.8 s. The image reconstruction time increases from 55 s when using data from a single angle to 108 s when using data from all four angles, as reported in Table 2. These results suggest that even for a torso phantom, the simulated POC‐PET system can still provide timely feedback to an operator under a clinical imaging scenario. The overall imaging time can be controlled within 5–7 mins (3–4 sampling angles) to obtain images of fair quality.

Figure 11.

Images reconstructed using list‐mode data from different numbers of sampling angles. (a) Sampling angle 1; (b) Sampling angles 1 + 2; (c) Sampling angles 1 + 2 + 3; (d) Sampling angles 1 + 2 + 3 + 4.

Figure 12.

The average CRC as a function of tumor sizes estimated from the four images in Fig. 11. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 2.

Reconstruction time for the images shown in Figure 11. Times shown in the table are all for ten iterations of list‐mode TOF‐PET image reconstruction

4. Discussion

The dynamically changing geometry and arbitrary trajectory of the maneuverable PET detectors may create additional challenges for scanner normalization. Component‐based normalization73, 74, 75 is a standard technique to model various physical factors that may affect detection efficiency of gamma‐ray detectors. In this preliminary work, all images were reconstructed based on the assumption that all LYSO crystals have the same detection efficiency for 511 keV gamma‐rays. A component‐based normalization that models detector efficiency as a function of incident angle of gamma‐rays will be necessary because the panel detectors may be placed very close to a patient's body and subject to a large variation in detector efficiency. An optimized method to balance the accuracy of normalization and computational speed requires future investigation.

In a conventional PET/CT or PET/MRI scanner, attenuation correction is often calculated from the CT or MR images. For a compact POC‐PET system, attenuation correction may be a challenge if there is not a second modality to provide anatomical information. One potential solution is to estimate the attenuation map of a subject based on data consistency. Ideally, when the PET scanner has very high TOF resolution, it is possible to estimate the attenuation image while simultaneously reconstructing the activity image without using a CT scan.76, 77, 78 Another option is to combine a compact US sensor and the compact POC‐PET system to perform simultaneous PET/US imaging. With the structural image obtained by an US sensor, attenuation correction may be calculated directly if the tissues in the imaging FOV are primarily soft tissues. Alternatively, the US images may be used to co‐register the POC‐PET images with previously acquired CT images of the same patient to calculate attenuation correction factors. Appropriate correction techniques, such as normalization, attenuation, and scatter corrections will need to be developed and validated to ensure the quantitative accuracy of PET images from this type of system.

Many research groups have reported that image reconstruction implemented on GPU devices significantly reduces the computation time.57, 58, 59, 60 Although the same or an even faster speed is achievable using a super computing cluster, a single computer with multiple GPUs will be much more favorable for POC‐PET imaging applications since it can be integrated with a portable device to provide a cost‐effective solution for image reconstruction. In principle, a single GPU has no more than one order of magnitude higher computation power than a multiple core single CPU. Further improvements are needed to achieve even faster image reconstruction capability. With dynamically changing geometry, an important part of the optimization will be to find an efficient on‐the‐fly forward/backward projection engine that can fully utilize the massive parallel structure of GPUs. Compared to off‐line computation of the system matrix in which we can use numerical methods to ensure accuracy, the projection engine used here is a spatially variant Gaussian kernel applied to the LOR connecting the center of the front surfaces of the crystal pair. The choice of such approach is a trade‐off between speed and accuracy. Without sub‐dividing each crystal into small sub‐volumes for an on‐the‐fly system matrix calculation, this method is subject to significant parallax effect when the detector panel is placed very close to a patient. However, when the detector panel is aimed at the center of the organ‐of‐interest, the scanning trajectory may be adjusted to minimize the parallax error at least for gamma‐rays that originate from the target region‐of‐interest.

The LYSO‐PMT based detector in the proof‐of‐concept prototype device is by no means optimized for the proposed applications. Although LYSO crystals of 1 mm cross‐section provided a high intrinsic spatial resolution, the crystals near the edges were not clearly re‐solved and thus cannot be used for coincidence detection. Moreover, its timing resolution (740 ps FWHM) is much worse than the timing resolution of many commercial WB PET/CT scanner.79 This can be easily improved by: (a) optimize the crystal size80 and (b) employ fast silicon photomultiplier (SiPM) based detector technology which can provide both fast timing resolution81, 82, 83 and good crystal resolvability.

The image quality of PET is determined by the counting statistics of data. Thus the minimal acquisition time will depend on the amount of radioactivity in the imaging FOV, the required sampling angles (detector position and orientation), the object size, etc. The answers to these variables are somewhat unpredictable because every radiotracer may have different pharmacokinetics. Every patient may also be imaged for different reasons. The proposed interactive imaging capability offers the operator near real‐time visual feedback in order to place the detector at the most critical positions and orientations to collect as much or as little data as needed. The minimum acquisition time is determined by the specific clinical task that a physician or an operator needs to complete. If the reconstruction time lags behind the minimal acquisition time, then the proposed POC‐PET system will suffer from the accumulated delay and fail to provide near real‐time feedback to the operator. Fortunately, the computational speed of CPU and GPU will continue to improve over time. Therefore, the minimum acquisition time due to counting statistics will likely be the primary limiting factor in the long run, while the computational expenses will not be a major concern in the future.

As noted, sensitivity image calculation is computationally expensive and will preclude the use of continuous freehand movement to scan a patient if real‐time visual feedback is desired. Ideally, we can use a few pre‐defined detector positions and trajectories to support most clinical imaging tasks and to accommodate patients of different characteristics. For example, the detector positions and trajectories can be determined based on patient's gender (male vs female), age (adult vs child), and body mass index (obese vs regular vs slim), or areas to be imaged (abdomen, chest, neck, head, etc.). This can speed up the image reconstruction using a pre‐calculated system matrix and sensitivity image during the scan. For patients of extreme body shape or imaging tasks that are not pre‐defined, we have the option to use partial or complete custom trajectory to further improve the image quality. Moreover, an operator may initiate a scan using a pre‐defined protocol followed by an interactive scanning session to ensure that the quality of the images can meet the requirements for the specific imaging tasks.

Although we achieved usable images without turning on the penalty function in Eq. (1) in our current reconstruction software, proper regularization could further improve the image quality under different imaging conditions, especially when the counting statistics are limited.84 The main focus of this work is to demonstrate the feasibility of a system that can provide near real‐time feedback to the operator to realize interactive imaging capability for point‐of‐care applications. Optimization85 of the regularization and its parameters will be investigated in the future.

An ideal POC‐PET system should include a mechanical design that not only allows flexible and easy placement of the detector panels by an operator, but also provides steady support of the detectors once they are placed at desired locations. More importantly, an appropriate mechanical design with appropriate shielding may also allow an operator to operate the device and benefit from its interactive imaging feature without excessive radiation exposure. A robotic arm (or two arms) that can be guided by hands or a joystick is a readily available solution. With a compact design, the POC‐PET can be moved to the patient's bedside for a variety of applications in point‐of‐care settings. A low‐cost system will permit both a broad installation base and the potential installation of multiple units within a cancer center to support novel molecular theranostic applications. Unlike other special purpose PET systems, this innovative approach affords maximum flexibility – whether the patient is an adult or a child, lying in a bed or sitting in a chair, undergoing a surgical procedure, or receiving radio‐immunotherapy.

5. Conclusion

In this work, we propose a new interactive PET imaging system, with near real‐time image reconstruction capability, using TOF PET detectors. Our preliminary studies (both experimental and Monte Carlo simulation) demonstrate the feasibility of a PET system that can provide near real‐time visual feedback to an operator who can maneuver a PET detector to interactively scan an organ‐of‐interest in a patient to support POC imaging applications.

The fast GPU‐based image reconstruction engine features a reconstruction speed of 0.96 × 106 events/s/iteration to process an image in a 600 × 600 × 224 mm3 voxel rectilinear space, with each voxel a 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 cube. The detectors in the prototype device have a CRT of 740 ps FWHM. The imaging study of a cylindrical phantom experimentally and by Monte Carlo simulation shows that a compact POC‐PET system can identify many lesions smaller than 10 mm in diameter. Even with limited CRT, the reconstructed images feature fewer artifacts that are due to limited angle tomography. Systems with better timing resolution further improved image quality and reduced artifacts.

Results of the Monte Carlo simulation for a body‐size torso phantom show that a POC‐PET system with significant higher sensitivity will allow one to obtain PET images in a ROI from 3 to 4 scanning angles with a total acquisition time of 7 min or less.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Arion F. Chatziioannou and Dr. Zheng Gu from the University of California Los Angeles for providing one of the H8500 PMT; Jonathan Elson for fabricating the detector holders; Prof. Yongjian Liu and Dr. Xiaohui Zhang for providing 64Cu for phantom studies. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Health (R01CA136554), the Department of Energy (DE‐SC0005157), and the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology internal fund. The Washington University Center for High Performance Computing is funded in part by the National Institute of Health (RR022984).

At the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2015 annual meeting in Baltimore, MD, the IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference 2017 in Atlanta, GA, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2018 annual meeting in Philadelphia, PA, our group has presented this novel image approach which resulted in three conference abstracts. This manuscript summarizes our work in the past 3 years that includes both experimental and simulation studies. The materials presented in this manuscript have not been published in any journal article. Moreover, the interactive imaging strategy and the torso phantom data are entirely new and have not been presented anywhere.

J Jiang conducted all Monte Carlo simulation studies, constructed the prototype POC‐PET system, designed and carried out imaging experiments, analyzed and interpreted all the data; K Li developed TOF‐PET list‐mode image reconstruction algorithm, implemented the GPU‐based computational framework, and developed alignment procedures for the robotic system; S Komarov contributed to the physics model for system matrix computation; JA O'Sullivan contributed to the image reconstruction and optimization algorithms; Y‐C Tai contributed to the inception of the technology, overall detector and system design, and the interactive scanning strategy.

References

- 1. Dudley JT, Listgarten J, Stegle O, Brenner SE, Parts L. Personalized medicine: from genotypes, molecular phenotypes and the quantified self, towards improved medicine. Paper presented at: Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing Co‐Chairs. 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. Roden DM. Personalized medicine and the genotype‐phenotype dilemma. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;31:17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robinson PN, Mungall CJ, Haendel M. Capturing phenotypes for precision medicine. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2015;1:a000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lyssenko V, Bianchi C, Del Prato S. Personalized therapy by phenotype and genotype. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl 2):S127–S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Del Vecchio S, Zannetti A, Fonti R, Pace L, Salvatore M. Nuclear imaging in cancer theranostics. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;51:152–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2010;62:1052–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kiessling F, Fokong S, Koczera P, Lederle W, Lammers T. Ultrasound microbubbles for molecular diagnosis, therapy, and theranostics. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacobson O, Chen XY. Interrogating tumor metabolism and tumor microenvironments using molecular positron emission tomography imaging. Theranostic approaches to improve therapeutics. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:1214–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teng FF, Meng X, Sun XD, Yu JM. New strategy for monitoring targeted therapy: molecular imaging. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:3703–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kalia M. Personalized oncology: recent advances and future challenges. Metabolism. 2013;62(Suppl 1):S11–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jivraj N, Phinikaridou A, Shah AM, Botnar RM. Molecular imaging of myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109:397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu M, Shu J. Multimodal molecular imaging: current status and future directions. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018;2018:1382183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liang G, Vo D, Nguyen PK. Fundamentals of cardiovascular molecular imaging: a review of concepts and strategies. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2017;10:8. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang F, Zhu L, Yang K, Park D. Theranostic probes for cancer imaging. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2017;2017:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sogbein OO, Pelletier‐Galarneau M, Schindler TH, Wei L, Wells RG, Ruddy TD. New SPECT and PET radiopharmaceuticals for imaging cardiovascular disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:942960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirao K, Smith GS. Positron emission tomography molecular imaging in late‐life depression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2014;27:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fowler AM. A molecular approach to breast imaging. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruijnen ST, Gent YY, Voskuyl AE, Hoekstra OS, van der Laken CJ. Present role of positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and monitoring of peripheral inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mease RC, Foss CA, Pomper MG. PET imaging in prostate cancer: focus on prostate‐specific membrane antigen. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:951–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoeben BA, Bussink J, Troost EG, Oyen WJ, Kaanders JH. Molecular PET imaging for biology‐guided adaptive radiotherapy of head and neck cancer. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:1257–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shen LH, Liao MH, Tseng YC. Recent advances in imaging of dopaminergic neurons for evaluation of neuropsychiatric disorders. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:259349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Penuelas I, Dominguez‐Prado I, Garcia‐Velloso MJ, et al. PET tracers for clinical imaging of breast cancer. J Oncol. 2012;2012:710561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Waerzeggers Y, Ullrich RT, Monfared P, et al. Specific biomarkers of receptors, pathways of inhibition and targeted therapies: clinical applications. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:S179–S195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quigley H, Colloby SJ, O'Brien JT. PET imaging of brain amyloid in dementia: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu HL, Hua MY, Yang HW, et al. Magnetic resonance monitoring of focused ultrasound/magnetic nanoparticle targeting delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15205–15210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brugarolas P, Sanchez‐Rodriguez JE, Tsai HM, et al. Development of a PET radioligand for potassium channels to image CNS demyelination. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ye D, Sultan D, Zhang X, et al. Focused ultrasound‐enabled delivery of radiolabeled nanoclusters to the pons. J Control Release. 2018;283:143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steichen SD, Caldorera‐Moore M, Peppas NA. A review of current nanoparticle and targeting moieties for the delivery of cancer therapeutics. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;48:416–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wei HM, Liu T, Jiang N, et al. A novel delivery system of cyclovirobuxine d for brain targeting: angiopep‐conjugated polysorbate 80‐Coated liposomes via intranasal administration. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2018;14:1252–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang B, Nichol JL, Sullivan JT. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of AMG 531, a novel thrombopoietin receptor ligand. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:628–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hakimzadeh N, Pinas VA, Molenaar G, et al. Novel molecular imaging ligands targeting matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 for imaging of unstable atherosclerotic plaques. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0187767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kelly JM, Amor‐Coarasa A, Nikolopoulou A, et al. Assessment of PSMA targeting ligands bearing novel chelates with application to theranostics: stability and complexation kinetics of Ga‐68(3 + ), In‐111(3 + ), Lu‐177(3 + .), and (225)AC(3 + ). Nucl Med Biol. 2017;55:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee NK, Kim HS, Kim KH, et al. Identification of a novel peptide ligand targeting visceral adipose tissue via transdermal route by in vivo phage display. J Drug Target. 2011;19:805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nowacki M, Peterson M, Kloskowski T, et al. Nanoparticle as a novel tool in hyperthermic intraperitoneal and pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotheprapy to treat patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:78208–78224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu HB, Li JX, Zhang QZ, et al. A novel small Odorranalectin‐bearing cubosomes: preparation, brain delivery and pharmacodynamic study on amyloid‐beta(25‐35)‐treated rats following intranasal administration. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80:368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu C, Shan W, Liu M, et al. A novel ligand conjugated nanoparticles for oral insulin delivery. Drug Deliv. 2016;23:2015–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raylman RR, Majewski S, Smith MF, et al. The positron emission mammography/tomography breast imaging and biopsy system (PEM/PET): design, construction and phantom‐based measurements. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:637–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bowen SL, Wu Y, Chaudhari AJ, et al. Initial characterization of a dedicated breast PET/CT scanner during human imaging. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1401–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. MacDonald L, Edwards J, Lewellen T, Haseley D, Rogers J, Kinahan P. Clinical imaging characteristics of the positron emission mammography camera: PEM Flex Solo II. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1666–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huh SS, Clinthorne NH, Rogers WL. Investigation of an internal PET probe for prostate imaging. Nucl Instrum Meth A. 2007;579:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huber JS, Derenzo SE, Qi J, Moses WW, Huesman RH, Budinger TF. Conceptual design of a compact positron tomograph for prostate imaging. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2001;48:1506–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stolin AV, Majewski S, Jaliparthi G, Raylman RR. Construction and evaluation of a prototype high resolution, silicon photomultiplier‐based, tandem positron emission tomography system. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2013;60:82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoffman EJ, Tornai MP, Janecek M, Patt BE, Iwanczyk JS. Intraoperative probes and imaging probes. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:913–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raylman RR, Wahl RL. A fiber‐optically coupled positron‐sensitive surgical probe. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jiang J, Li K, Komarov S, et al. Development of a simultaneous PET/Ultrasound imaging system with near real‐time reconstruction capability for point‐of‐care applications. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(suppl. 1):363. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jiang J, Li K, Qi B, et al. Development of a simultaneous PET/Ultrasound imaging system with near real‐time reconstruction capability for point‐of‐care applications. Paper presented at: 2017 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC) 2017.

- 47. Todica A, Brunner S, Boning G, et al. [Ga‐68]‐Albumin‐PET in the monitoring of left ventricular function in murine models of ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy: comparison with cardiac MRI. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saatchi K, Gelder N, Gershkovich P, et al. Long‐circulating non‐toxic blood pool imaging agent based on hyperbranched polyglycerols. Int J Pharm. 2012;422:418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Boros E, Ferreira CL, Patrick BO, Adam MJ, Orvig C. New Ga derivatives of the H2dedpa scaffold with improved clearance and persistent heart uptake. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:1165–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Banerjee SR, Pomper MG. Clinical applications of Gallium‐68. Appl Radiat Isot. 2013;76:2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Surti S, Karp JS. Design considerations for a limited angle, dedicated breast. TOF PET scanner. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:2911–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Surti S, Zou W, Daube‐Witherspoon ME, McDonough J, Karp JS. Design study of an in situ PET scanner for use in proton beam therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:2667–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Keesing DB, Mathews A, Komarov S, et al. Image reconstruction and system modeling techniques for virtual‐pinhole PET insert systems. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:2517–2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mathews AJ, Li K, Komarov S, et al. A generalized reconstruction framework for unconventional PET systems. Med Phys. 2015;42:4591–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smith M. Image Reconstruction for Prostate Specific Nuclear Medicine Imagers. Newport News, VA: Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mathews AJ, Komarov S, Wu HY, O'Sullivan JA, Tai YC. Improving PET imaging for breast cancer using virtual pinhole PET half‐ring insert. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:6407–6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pratx G, Surti S, Levin C. Fast list‐mode reconstruction for time‐of‐flight pet using graphics hardware. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2011;58:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cui JY, Pratx G, Prevrhal S, Levin CS. Fully 3D list‐mode time‐of‐flight PET image reconstruction on GPUs using CUDA. Med Phys. 2011;38:6775–6786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pratx G, Cui J‐Y, Prevrhal S, Levin CS. 3‐D tomographic image reconstruction from randomly ordered lines with CUDA. In GPU Computing Gems Emerald Edition. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2011:679–691. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jiang JY, Shimazoe K, Nakamura Y, et al. A prototype of aerial radiation monitoring system using an unmanned helicopter mounting a GAGG scintillator Compton camera. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2016;53:1067–1075. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Huh SS, Han L, Rogers WL, Clinthorne NH. Real time image reconstruction using GPUs for a surgical PET imaging probe system. Paper presented at: 2009 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record (NSS/MIC); 24 Oct.‐1 Nov. 2009, 2009.

- 62. O'Sullivan JA, Benac J. Alternating minimization algorithms for transmission tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bouman CA. Model Based Image Processing. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lin CJ, Weng RC, Keerthi SS. Trust region Newton method for large‐scale logistic regression. J Mach Learn Res. 2008;9:627–650. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tai YC, Wu H, Pal D, O'Sullivan JA. Virtual‐pinhole PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Conti M. Focus on time‐of‐flight PET: the benefits of improved time resolution. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1147–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Evans JD, Politte DG, Whiting BR, O'Sullivan JA, Williamson JF. Noise‐resolution tradeoffs in x‐ray CT imaging: a comparison of penalized alternating minimization and filtered backprojection algorithms. Med Phys. 2011;38:1444–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. NVIDIA NC . CUDA Documentation v9.2.148. Maxwell Tuning Guide.

- 69. Jiang J, Li K, Wang Q, et al. Initial results from a prototype flat‐panel virtual‐pinhole PET insert system for improving lesion detectability. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(supplement 1):429. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Siegel S, Silverman RW, Shao YP, Cherry SR. Simple charge division readouts for imaging scintillator arrays using a multi‐channel PMT. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1996;43:1634–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Santin G, Strul D, Lazaro D, et al. GATE: a Geant4‐based simulation platform for PET and SPECT integrating movement and time management. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2003;50:1516–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Daube‐Witherspoon ME, Karp JS, Casey ME, DiFilippo FP. PET performance measurements using the NEMA NU 2‐2001 standard. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Badawi RD, Marsden PK. Developments in component‐based normalization for 3D PET. Phys Med Biol. 1999;44:571–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bai B, Li Q, Holdsworth CH, et al. Model‐based normalization for iterative 3D PET image reconstruction. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47:2773–2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Casey M, Gadagkar H, Newport D. A component based method for normalization in volume PET. 1996.

- 76. Defrise M, Rezaei A, Nuyts J. Time‐of‐flight PET data determine the attenuation sinogram up to a constant. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:885–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rezaei A, Defrise M, Nuyts J. ML‐Reconstruction for TOF‐PET with simultaneous estimation of the attenuation factors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2014;33:1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rezaei A, Defrise M, Bal G, et al. Simultaneous reconstruction of activity and attenuation in time‐of‐flight PET. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2012;31:2224–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jakoby BW, Bercier Y, Conti M, Casey ME, Bendriem B, Townsend DW. Physical and clinical performance of the mCT time‐of‐flight PET/CT scanner. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:2375–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Krishnamoorthy S, LeGeyt B, Werner ME, et al. Design and performance of a high spatial resolution, time‐of‐flight PET Detector. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2014;61:1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Brunner SE, Gruber L, Hirtl A, Suzuki K, Marton J, Schaart DR. A comprehensive characterization of the time resolution of the Philips Digital Photon Counter. J Instrum. 2016;11:P11004. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nemallapudi MV, Gundacker S, Lecoq P, et al. Sub‐100 ps coincidence time resolution for positron emission tomography with LSO: Ce codoped with Ca. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:4635–4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cates JW, Levin CS. Advances in coincidence time resolution for PET. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61:2255–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jia X, Liao Y, Zeng D, et al. Statistical CT reconstruction using region‐aware texture preserving regularization learning from prior normal‐dose CT image. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:225020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Liang H, Weller DS. Regularization parameter trimming for iterative image reconstruction. Paper presented at: Signals, Systems and Computers, 2015 49th Asilomar Conference on 2015.