Abstract

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that maternal height is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, controlling for and stratified by maternal body mass index (BMI).

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study of all births in California between 2007–2010 (n=1,775,984). Maternal height was categorized into quintiles with lowest quintile (≤20%) as shorter stature and the uppermost quintile (≥80%) representing taller stature. Outcomes included gestational diabetes (GDM), preeclampsia, cesarean, preterm birth (PTB), macrosomia, and low birth weight (LBW). We calculated height/outcome associations among BMI categories, and BMI/outcome associations among height categories, using various multivariable logistic regression models.

Results:

Taller women were less likely to have GDM, nulliparous cesarean, PTB, and LBW; these associations were similar across maternal BMI categories and persisted after multivariable adjustment. In contrast, when stratified by maternal height, the associations between maternal BMI and birth outcomes varied by specific outcomes. e.g., the association between morbid obesity (compared with normal or overweight) and risk of GDM was weaker among shorter women (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.48, 3.28–3.69) than taller women (aOR, 95% CI: 4.42, 4.19–4.66).

Conclusions:

Maternal height is strongly associated with altered perinatal risk even after accounting for variations in complications by BMI.

Keywords: Cesarean, gestational diabetes, maternal height, obesity

Introduction

The obesity epidemic has affected all areas of health in the United States, including birth outcomes. Maternal height is a component of body mass index (BMI) and one which may independently affect birth outcomes.1 However, few studies have examined the potential predictive power of maternal height on perinatal outcomes, relative to the large amounts of research on maternal BMI and weight.2–4 Although maternal height is not a modifiable risk factor, it may reflect both maternal nutritional status during childhood/adolescence5,6 and genetic influences7 which may predispose individuals to altered perinatal outcomes. While there are numerous evidence-based perinatal management guidelines for women with obesity, studies that examine the association of maternal height and BMI with adverse perinatal outcomes are lacking. Knowledge of the impact of maternal height in relation to BMI may therefore provide valuable information to women and obstetric providers in understanding a given woman’s risk for various adverse perinatal outcomes.

Height does appear to play a role in the risk for GDM, which has been associated with shorter maternal stature.8–10 Possible explanations for this variation have ranged from genetic predisposition, to shorter stature as the result of altered fetal metabolic programming,11 to impaired metabolism based on lower mass of metabolically active tissues compared to taller women and subsequent decreased ability to respond appropriately to a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.12 Similarly, shorter maternal height has been associated with greater risk of cesarean delivery,13 particularly among women carrying fetuses with macrosomia, which may be related to an increased risk of cephalopelvic disporportion.14 However, the relationship between maternal height and child birthweight is mixed.15–17 As it is known that maternal obesity is associated with an increased incidence of GDM, cesarean delivery, and macrosomia, it is important to determine how maternal height may alter perinatal risk by BMI, and, conversely, how maternal BMI may alter risk by maternal height.

Therefore, we sought to characterize the independent and joint associations between maternal height and obesity on a variety of birth outcomes. Because we were interested in the potential for effect modification of maternal stature by maternal BMI, we examined height-outcome associations overall and stratified by maternal BMI, and also the converse (i.e., maternal BMI/outcome associations stratified by maternal height). We hypothesized that shorter maternal stature would be a risk factor for adverse birth outcomes related to altered metabolism (i.e., GDM) and primary cesarean delivery, independent of BMI. In addition, we hypothesized that taller maternal stature would be a risk factor for fetal macrosomia, adjusting for maternal BMI.

Materials and Methods:

This was a retrospective cohort study of all births occurring in the state of California between 2007 and 2010 (n=2,094,220). We analyzed the Office of Statewide Health Planning & Development linked vital statistics/patient discharge database, which contains linked vital statistics data and hospital discharge data for all California deliveries. The dataset contains birth and death certificate data linked to maternal hospital discharge data for the nine months prior to birth and maternal/infant hospital discharge data for the year after birth. Mother-baby pairs were linked using probabilistic linkage methods. Details of the dataset have been published elsewhere.18

Exposure variables

Maternal weight data on birth certificates have noted shortcomings19, so we performed data cleaning prior to analysis. Mothers with either missing (N=110,144) or improbable weight, defined as gaining ≥ 80 lbs. or losing ≥30 lbs., (N=11,369) were excluded from the study. Records were also excluded for missing maternal height (N=111,183) and extreme previability (GA < 20 weeks, N=8,734). Our analysis was focused on women of higher BMI, thus women with underweight (BMI < 18.5) were excluded from the analysis (N= 78,806). The final sample included 1,775,984 records.

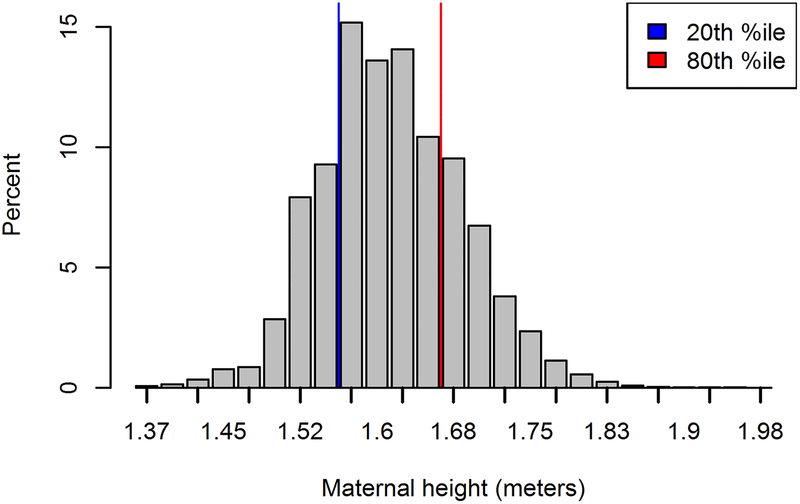

Maternal height and maternal BMI were the key exposure variables. There are limited studies on which to base maternal height classification, which have primarily been among homogenous race/ethnicity groups. In order to better evaluate height related associations among a racially/ethnically diverse population, we chose to categorize maternal height into quintiles, with the lowest quintile (i.e. 20th %ile or less) being classified as shorter-stature, and the uppermost quintile (i.e. ≥ 80th %ile) as taller-stature. Mothers whose height fell into the middle three quintiles (i.e. 21st-79th%ile for height) were classified as average height, which served as the reference group. Maternal BMI was categorized using the WHO BMI categories20: normal weight women (BMI ≥18.5 – <25kg/m2), women who are overweight (≥25.0 – <30), women with obesity (≥30.0 – <40), and women with morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0).

Outcome variables

We were interested in the impact of maternal height and BMI on a range of perinatal outcomes. The specific maternal outcomes we analyzed were: GDM and preeclampsia. Both were defined by International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes, as recorded in the maternal hospital discharge data or on the birth certificate (GDM: 775.0, 648.80, 648.81–648.84; preeclampsia: 401.0, 642.4×, 642.5×, 642.7×). Women with pre-existing diabetes (defined via ICD-9 (410.0×, 642.0×, 642.1×, 642.2×) or the birth certificate) were excluded (N= 18,746) from the denominator of gestational diabetes; those with chronic hypertension (defined via ICD-9 (250×) or the birth certificate) were excluded (N=23,251) from the denominator of gestational hypertension. We analyzed primary cesarean delivery in nulliparous or multiparous women, using mode of delivery as recorded on the birth certificate. Multiparous women with prior cesarean (defined from the birth certificate and ICD-9 codes) were excluded (N=299,979) from the denominator for this outcome.

Infant outcomes were PTB (gestational age <37 completed weeks), macrosomia (birthweight ≥4,000 grams [g]), and low birthweight (LBW) (birthweight <2,500g). Birthweight and gestational age were recorded on the birth certificate. The clinical/obstetric estimate of gestational age was analyzed, as it is more valid than last menstrual period dating.21

Covariates

We controlled for covariates of advanced maternal age (>35 years), maternal educational attainment (≥12 years versus <12), parity (nulliparous versus multiparous), maternal insurance status (private versus public/none), prenatal care initiation (first trimester versus later/none), chronic hypertension status, and chronic diabetes status.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the demographic profile of our sample of California births.

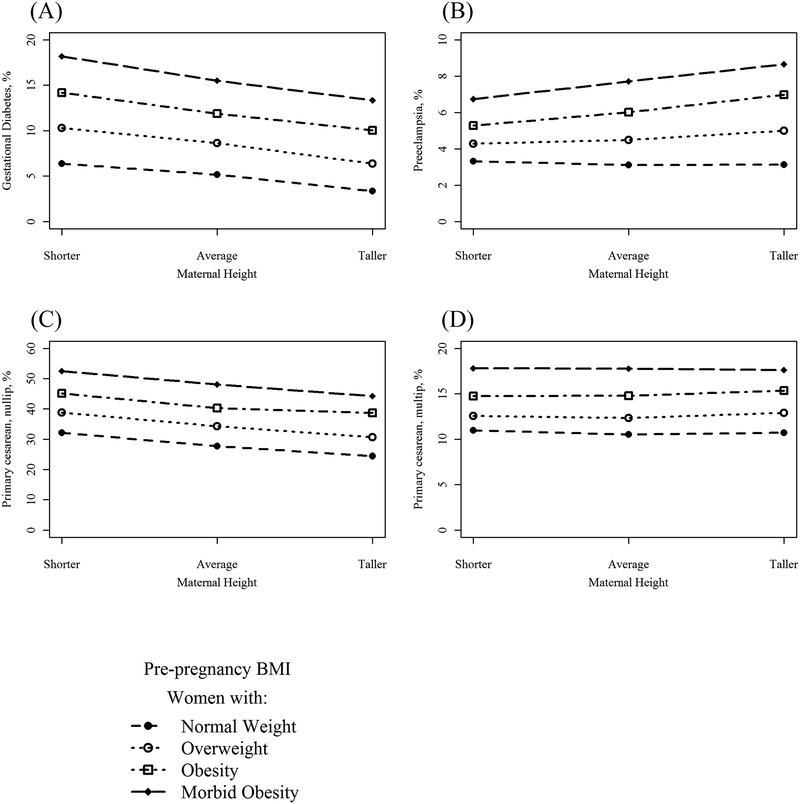

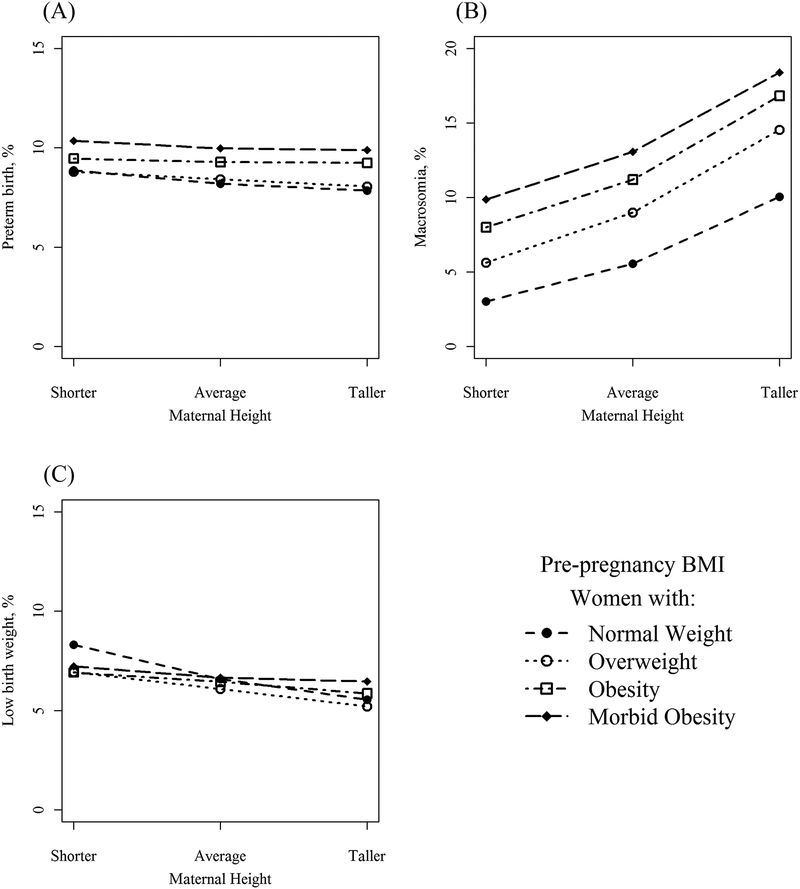

We analyzed unadjusted associations between height and perinatal outcomes, stratified by BMI categories, by graphing the prevalence of each outcome across increasing categories of maternal height. For each outcome, we graphed women with normal-weight, overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity using a unique line.

We employed several multivariable logistic regression modeling approaches to assess the independent and joint association between maternal height and maternal BMI with perinatal outcomes. We controlled for the same covariates in all 3 models. To analyze the independent relationship between height and maternal BMI on perinatal outcomes, we first fit a basic model (model 1) on our analytical sample, with indicator variables for maternal height (referent category: average stature) and maternal body mass index.

To further the understanding of the joint effects of height and BMI, we then fit stratified models. The purpose of these models was to examine height/outcome associations among BMI categories, and then to examine BMI/outcome associations among height categories. In model 2, we fit height models comparing the risk of adverse outcomes among women of shorter or taller stature (referent group for both models: average-stature women), stratified by BMI category. For each outcome, a model was fit comparing shorter-height and taller-height to average-height in women with normal weight, then shorter-height and taller-height to average-height in women with overweight, and so on. This process was repeated within other BMI categories (obesity, morbid obesity), in all cases comparing outcomes in shorter-stature and taller-stature women to the referent category (average-height women of the same BMI category). This enabled us to isolate the relationship between maternal height and outcomes, assessing whether this association varied by BMI status (i.e., effect modification).

Our third and final modeling approach examined the converse association, analyzing the association of maternal BMI category and perinatal outcomes, within height categories. For each outcome, we fit a model among shorter-stature women, with indicator variables for maternal obesity and maternal morbid obesity (referent category: women with normal weight and overweight combined). We repeated this process with average-stature women, then taller-stature women. This enabled us to assess whether the association of maternal obesity and perinatal outcomes differed by maternal height, the other component required to characterize the interrelationship between maternal height, BMI, and adverse birth outcomes.

We obtained human subjects approval from the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University and the California Office of Statewide Planning and Development. Analyses were conducted using Stata (version 14, StataCorp; College Station, TX); figures were prepared using R (version 3.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria).

Results

Our final sample included 1,775,984 women who delivered in California from 2007–2010. Maternal height distribution is shown in Figure 1. Women with a BMI over 25 made up 47.2% of the population, with 26.8% of women meeting criteria for overweight and 20.5% for obesity.

Figure 1.

Distribution of maternal height in California (2007–2010), with height cut points as defined by dataset

Unadjusted prevalence of all outcomes among BMI categories, by increasing height, is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Women who are taller, regardless of BMI, were the least likely to develop GDM (e.g. 10.0% and 14.2% in taller and shorter women, respectively, with obesity, Figure 2A). Among women with obesity and morbid obesity, shorter women were less likely to develop preeclampsia compared to their taller peers (Figure 2B), an association that was not observed among leaner women. Among nulliparous women, taller women had a lower risk of cesarean compared to their average and shorter peers (Figure 2C), but height had no association with cesarean among multiparous women (Figure 2D). Height was generally not associated with the risk of preterm birth, although shorter women with morbid obesity were at the highest risk at 10.4% (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of maternal outcomes. A) Gestational diabetes*; B) preeclampsia**, C) primary cesarean delivery (nulliparous)+; D) primary cesarean delivery (multiparous)*

Figure 3.

Prevalence of neonatal outcomes. A) Preterm birth; B) macrosomia; C) low birth weight.

After multivariable adjustment assessing the independent association between maternal height and perinatal outcomes (Model 1), the relationship between shorter stature and higher odds of GDM (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.20, 1.19–1.22) and primary cesarean, nulliparous (aOR, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.31–1.35) persisted, while taller status had lower risk of these outcomes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable adjusted* association between maternal height and perinatal outcomes (model 1)

| Maternal height | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter stature | Average stature | Taller stature | |

| Gestational diabetes* | 1.20 (1.19, 1.22) | Ref. | 0.81 (0.80, 0.82) |

| Preeclampsia** | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | Ref. | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) |

| Primary CD, nulliparous+ | 1.33 (1.31, 1.35) | Ref. | 0.79 (0.78, 0.80) |

| Primary CD, multiparous | 1.09 (1.07, 1.11) | Ref. | 0.95 (0.94, 0.97) |

| Preterm birth | 1.11 (1.10, 1.13) | Ref. | 0.91 (0.90, 0.92) |

| Macrosomia | 0.63 (0.62, 0.64) | Ref. | 1.71 (1.69, 1.73) |

| Low birth weight | 1.27 (1.25, 1.29) | Ref. | 0.80 (0.79, 0.81) |

Results are adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval). Multivariable logistic regression models controlled for advanced maternal age, maternal education (≥12 years versus <12), parity (nulliparous versus parous), public insurance status, prenatal care initiation in 1st trimester, chronic hypertension, and chronic diabetes. Bold indicates p<0.05.

Denominator excludes women with chronic diabetes.

Denominator excludes women with chronic hypertension.

Denominator excludes women with prior cesarean delivery.

When comparing adjusted odds of adverse outcomes among shorter and taller women to average-height women among maternal BMI categories (model 2), elevated BMI status generally did not confer additional risk beyond the risk associated with height, and in fact, the height-outcome associations attenuated with increasing BMI category. Maternal short stature remained a risk factor for GDM, nulliparous cesarean delivery, PTB (except for women with morbid obesity), and LBW while taller stature remained protective (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs)* comparing adverse perinatal outcomes among shorter and taller women to average-height women (referent group), stratified by BMI status (model 2)

| Shorter | Average | Taller | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational diabetes* | Normal weight women | 1.22 (1.19, 1.25) | Ref. | 0.72 (0.70, 0.74) |

| Overweight women | 1.17 (1.14, 1.20) | Ref. | 0.78 (0.75, 0.80) | |

| Women with obesity | 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) | Ref. | 0.89 (0.86, 0.92) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 1.13 (1.06, 1.21) | Ref. | 0.88 (0.83, 0.93) | |

| Preeclampsia** | Normal weight women | 1.12 (1.09, 1.16) | Ref. | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) |

| Overweight women | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | Ref. | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | |

| Women with obesity | 0.95 (0.92, 0.99) | Ref. | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | Ref. | 1.13 (1.05, 1.22) | |

| Primary CD, nulliparous+ | Normal weight women | 1.38 (1.35, 1.40) | Ref. | 0.75 (0.74, 0.77) |

| Overweight women | 1.33 (1.29, 1.36) | Ref. | 0.77 (0.75, 0.79) | |

| Women with obesity | 1.26 (1.22, 1.31) | Ref. | 0.86 (0.84, 0.89) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 1.17 (1.05, 1.30) | Ref. | 0.82 (0.76, 0.89) | |

| Primary CD, multiparous | Normal weight women | 1.38 (1.35, 1.40) | Ref. | 0.75 (0.74, 0.77) |

| Overweight women | 1.08 (1.05, 1.12) | Ref. | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | |

| Women with obesity | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | Ref. | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 1.03 (0.93, 1.13) | Ref. | 0.92 (0.85, 1.01) | |

| Preterm birth | Normal weight women | 1.15 (1.12, 1.17) | Ref. | 0.89 (0.88, 0.91) |

| Overweight women | 1.10 (1.07, 1.13) | Ref. | 0.90 (0.88, 0.93) | |

| Women with obesity | 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) | Ref. | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | Ref. | 0.89 (0.82, 0.95) | |

| Macrosomia | Normal weight women | 0.56 (0.54, 0.57) | Ref. | 1.76 (1.72, 1.79) |

| Overweight women | 0.60 (0.58, 0.62) | Ref. | 1.70 (1.66, 1.74) | |

| Women with obesity | 0.67 (0.65, 0.69) | Ref. | 1.64 (1.59, 1.68) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 0.77 (0.71, 0.83) | Ref. | 1.51 (1.43, 1.60) | |

| Low birth weight | Normal weight women | 1.36 (1.33, 1.38) | Ref. | 0.79 (0.77, 0.80) |

| Overweight women | 1.21 (1.17, 1.25) | Ref. | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) | |

| Women with obesity | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | Ref. | 0.85 (0.82, 0.88) | |

| Women with morbid obesity | 1.23 (1.11, 1.35) | Ref. | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) |

Models controlled for advanced maternal age, maternal education (≥12 years versus <12), parity (nulliparous versus parous), public insurance status, prenatal care initiation in 1st trimester, chronic hypertension, and chronic diabetes. Bold indicates p<0.05.

Excludes women with chronic diabetes.

Excludes women with chronic hypertension.

Excludes women with prior cesarean delivery.

Having examined height/outcome associations, we next examined the converse in model 3, which analyzed the association between maternal BMI and perinatal outcomes, stratified by maternal height. In comparison to women with normal weight and overweight, the association for GDM and obesity was stronger across increasing categories of maternal height, (e.g., morbid obesity aOR, 95% CI: 3.48, 3.28–3.69 among shorter women; morbid obesity aOR, 95% CI: 4.42, 4.19–4.66 among taller women) (Table 4). This contrasts with model 2, in which the height/outcome association was similar across BMI categories. A similar phenomenon was observed with preeclampsia, where the BMI/outcome association was stronger among women of taller stature as compared to their shorter counterparts. Similarly, the BMI/macrosomia association was stronger in magnitude among shorter stature women, as compared to their taller counterparts. This was also true of LBW, for which obesity and morbid obesity were protective among shorter-stature women, but not among taller women.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs)* comparing adverse perinatal outcomes among women with obesity, and women with morbid obesity, compared to women with no obesity (normal & overweight), stratified by maternal height (model 3).

| Women with normal/overweight | Women with obesity | Women with morbid obesity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational diabetes* | Shorter stature | Ref. | 2.24 (2.18, 2.29) | 3.48 (3.28, 3.69) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 2.42 (2.37, 2.46) | 3.90 (3.76, 4.05) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 2.84 (2.76, 2.93) | 4.42 (4.19, 4.66) | |

| Preeclampsia** | Shorter stature | Ref. | 1.73 (1.67, 1.80) | 2.45 (2.25, 2.66) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 1.99 (1.94, 2.04) | 2.86 (2.72, 3.00) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 2.17 (2.10, 2.25) | 3.20 (3.01, 3.41) | |

| Primary CD, nulliparous+ | Shorter stature | Ref. | 1.67 (1.61, 1.73) | 2.55 (2.32, 2.80) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 1.79 (1.76, 1.83) | 2.92 (2.78, 3.07) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 1.95 (1.89, 2.01) | 2.96 (2.78, 3.16) | |

| Primary CD, multiparous* | Shorter stature | Ref. | 1.34 (1.30, 1.39) | 1.95 (1.79, 2.12) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 1.45 (1.42, 1.49) | 2.08 (1.98, 2.19) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 1.47 (1.42, 1.52) | 1.96 (1.83, 2.10) | |

| Preterm birth | Shorter stature | Ref. | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.21) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 1.14 (1.11, 1.17) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20) | |

| Macrosomia | Shorter stature | Ref. | 1.99 (1.93, 2.06) | 2.98 (2.77, 3.19) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 1.74 (1.71, 1.77) | 2.21 (2.13, 2.30) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 1.66 (1.62, 1.70) | 1.96 (1.87, 2.06) | |

| Low birth weight | Shorter stature | Ref. | 0.90 (0.87, 0.93) | 0.87 (0.80, 0.95) |

| Average stature | Ref. | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) | |

| Taller stature | Ref. | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) |

Models controlled for advanced maternal age, maternal education (≥12 years versus <12), parity (nulliparous versus parous), public insurance status, prenatal care initiation in 1st trimester, chronic hypertension, and chronic diabetes Bold indicates p<0.05.

Excludes women with chronic diabetes.

Excludes women with chronic hypertension.

Excludes women with prior cesarean delivery.

Preliminary data analysis revealed that a large majority of shorter-stature women were Hispanic (71.5%). In addition to controlling for race/ethnicity in multivariable regression models, we conducted a sensitivity analyses restricted to non-Hispanic women. The findings did not differ in terms of direction of association, and were nearly always the same in terms of magnitude of association and statistical significance (data not shown).

Comment

In this large sample of California births, we consistently observed meaningful associations between maternal height and a variety of perinatal outcomes, although the nature of the associations was often complex. This study suggests that the associations between maternal height and outcomes were fairly constant, and did not vary much by maternal BMI category. In contrast, the associations between maternal BMI and birth outcomes did vary both by the specific outcomes and also maternal height category. This highlights that although maternal height is indeed a key prognostic variable in pregnancy and birth, the interpretations are not straightforward.

With regards to specific outcomes, we were able to confirm the association of maternal shorter stature and GDM incidence and add that the disparity is greatest among normal weight women, and attenuated slightly with increasing maternal BMI. This attenuation of height-related risk with increasing BMI may be explained by the fact that maternal weight is highly correlated with GDM and macrosomia, i.e., in the heavier subgroups, these factors other than maternal height play a greater role in influencing the development of these adverse perinatal outcomes.

The greatest impact of these findings may be in relation to women of normal weight. Patients and providers should be aware that shorter women, compared to average height women, are at higher risk for GDM, preeclampsia, nulliparous primary CD, PTB, and LBW.

In adjusted analyses comparing elevated BMI status to normal weight/overweight, among height groups (model 3), associations between BMI and outcomes were strongest for some adverse perinatal events among shorter women (e.g., macrosomia, LBW), and strongest for some outcomes among taller women (e.g., GDM, preeclampsia). This suggests that increasing maternal BMI may be able to “overcome” the protective effect afforded by taller maternal height for conditions such as GDM and primary cesarean. Similarly, although shorter women overall are at decreased risk for macrosomia compared to their average and taller height peers, shorter women with morbid obesity are at almost 3-fold higher risk for macrosomia compared to their shorter peers with normal/overweight BMI. These height and BMI associations are strong and their specific direction and magnitude varies greatly by the outcome. Although both height and BMI are prognostically important, the specific associations are complex and require consideration.

Strengths of this study include a large, diverse population with a well-characterized database, although we cannot generalize our findings to the entire United States perinatal population. Limitations include those imposed by reliance on ICD-9 coding and birth certificate variables, which have variable reliability and validity.23,24 Maternal height and BMI were based on maternal self-report of height and pre-pregnancy weight as recorded on birth certificates, and although maternal height and maternal obesity have separate contributions to birth outcomes, we do acknowledge that maternal height is itself a component of our measure of maternal adiposity (BMI). There are limited studies on the validity of self-reported height and weight on birth certificates as compared to medical records, with the majority showing an agreement of around 75%.19

Conclusion

Maternal height is highly associated with altered perinatal risk in addition to risks associated with variations in maternal weight, and associations vary depending on the outcome. These associations are complex and require additional future research to more fully characterize the mechanisms underlying these associations. Providers and patients should be aware of the association of maternal height on perinatal outcomes, particularly among women of normal weight, to individualize maternal screening in pregnancy and to help optimize outcomes for mothers and infants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of California women delivering in 2008 – 2010 (N [%])

| Total N= 1,775,984 |

Shorter stature ≤ 61” N= 394,516 (22.2%) |

Average stature 62–65” N= 946,051 (53.3%) |

Taller stature ≥ 66” N= 435,417 (24.5%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category | ||||

| Normal weight | 932,588 (52.5) | 190,786 (48.4) | 507,096 (53.6) | 234,706 (53.9) |

| Overweight | 475,144 (26.8) | 119,581 (30.3) | 244,359 (25.8) | 111,204 (25.5) |

| Obese | 317,144 (17.9) | 74,691 (18.9) | 167,998 (17.8) | 74,455 (17.1) |

| Morbid obesity | 45,990 (2.6) | 8,525 (2.2) | 23,948 (2.5) | 13,517 (3.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 483,349 (27.2) | 38,422 (9.7) | 230,653 (24.4) | 214,274 (49.2) |

| Black | 93,017 (5.2) | 10,413 (2.6) | 45,912 (4.9) | 36,692 (8.4) |

| Hispanic | 961,513 (54.1) | 282,025 (71.5) | 532,627 (56.3) | 146,861 (33.7) |

| Asian | 186,719 (10.5) | 55,406 (14.0) | 108,501 (11.5) | 22,812 (5.2) |

| Other | 41,160 (2.3) | 6,680 (1.7) | 23,012 (2.4) | 11,468 (2.6) |

| Nulliparous | 692,895 (39.0) | 140,073 (35.5) | 370,257 (39.1) | 182,565 (41.9) |

| Education (≥12 yrs) | 1,284,575 (72.3) | 228,133 (57.8) | 687,089 (72.6) | 369,353 (84.8) |

| Age (≥35 yrs) | 323,486 (18.2) | 63,286 (16.0) | 170,304 (18.0) | 89,896 (20.7) |

| Non-private insurance | 856,967 (48.3) | 246,183 (62.4) | 457,145 (48.3) | 153,639 (35.3) |

| Prenatal care 1st tri. | 1,459,725 (82.2) | 312,894 (79.3) | 778,992 (82.3) | 367,839 (84.5) |

| Prior cesarean | 299,979 (16.9) | 80,297 (20.4) | 157,728 (16.7) | 61,954 (14.2) |

| Chronic hypertension | 23,251 (1.3) | 3,869 (0.98) | 11,963 (1.3) | 7,419 (1.7) |

| Preexisting diabetes | 18,746 (1.1) | 4,610 (1.2) | 9,693 (1.0) | 4,443 (1.0) |

Funding:

NEM is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (grant number K23HD069520-01A1).

JMS and FMB are supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (grant number R00 HD079658-03).

JBH is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (grant number K01-DK1022857)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Condensation: Maternal height is strongly associated with altered perinatal risk even after accounting for variations in complications by BMI.

References

- 1.Maternal anthropometry and pregnancy outcomes. A WHO Collaborative Study: Introduction. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73 Suppl:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cnattingius S, Villamor E, Johansson S, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2362–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, England L, Wilson HG, Bish C, Satten GA, Dietz P. Percentage of gestational diabetes mellitus attributable to overweight and obesity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Klebanoff MA, Ness RB, Roberts JM. Prepregnancy body mass index and the occurrence of severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Epidemiology. 2007;18(2):234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asao K, Kao WH, Baptiste-Roberts K, Bandeen-Roche K, Erlinger TP, Brancati FL. Short stature and the risk of adiposity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes in middle age: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1632–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Association between leg length and offspring birthweight: partial explanation for the trans-generational association between birthweight and cardiovascular disease: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2003;17(2):148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leary S, Fall C, Osmond C, et al. Geographical variation in relationships between parental body size and offspring phenotype at birth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(9):1066–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Sappenfield W, Sharma AJ, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal overweight and obesity, by nativity, Florida, 2004–2007. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(1):E33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogonowski J, Miazgowski T. Are short women at risk for gestational diabetes mellitus? Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(3):491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang HC, Min HK, Lee HK, Cho NH, Metzger BE. Short stature in Korean women: a contribution to the multifactorial predisposition to gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1998;41(7):778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet. 1993;341(8850):938–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathmann W, Strassburger K, Giani G, Doring A, Meisinger C. Differences in height explain gender differences in the response to the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabet Med. 2008;25(11):1374–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke N, Burke G, Breathnach F, et al. Prediction of Cesarean Delivery in the Term Nulliparous Woman: Results from the Prospective Multi-center Genesis Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazouni C, Rouzier R, Collette E, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict the risk of cesarean delivery in macrosomia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2008;87(5):518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young MF, Nguyen PH, Addo OY, et al. The relative influence of maternal nutritional status before and during pregnancy on birth outcomes in Vietnam. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voigt M, Rochow N, Jahrig K, Straube S, Hufnagel S, Jorch G. Dependence of neonatal small and large for gestational age rates on maternal height and weight--an analysis of the German Perinatal Survey. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(4):425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mavalankar DV, Trivedi CC, Gray RH. Maternal weight, height and risk of poor pregnancy outcome in Ahmedabad, India. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31(10):1205–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snowden JM, Cheng YW, Emeis CL, Caughey AB. The impact of hospital obstetric volume on maternal outcomes in term, non-low-birthweight pregnancies. (1097–6868 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodnar LM, Abrams B, Bertolet M, et al. Validity of birth certificate-derived maternal weight data. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(3):203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ananth CV. Menstrual versus clinical estimate of gestational age dating in the United States: temporal trends and variability in indices of perinatal outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21 Suppl 2:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lain SJ, Hadfield RM, Raynes-Greenow CH, et al. Quality of data in perinatal population health databases: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012;50(4):e7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goff SL, Pekow PS, Markenson G, Knee A, Chasan-Taber L, Lindenauer PK. Validity of using ICD-9-CM codes to identify selected categories of obstetric complications, procedures and co-morbidities. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(5):421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]