Abstract

Physicians in most specialties frequently encounter patients with neurologic conditions. For most non-neurologists, postgraduate neurologic education is variable and often limited, so every medical school's curriculum must include clinical learning experiences to ensure that all graduating medical students have the basic knowledge and skills required to care for patients with common neurologic symptoms and neurologic emergencies. In the nearly 20 years that have elapsed since the development of the initial American Academy of Neurology (AAN)–endorsed core curriculum for neurology clerkships, many medical school curricula have evolved to include self-directed learning, shortened foundational coursework, earlier clinical experiences, and increased utilization of longitudinal clerkships. A workgroup of both the Undergraduate Education Subcommittee and Consortium of Neurology Clerkship Directors of the AAN was formed to update the prior curriculum to ensure that the content is current and the format is consistent with evolving medical school curricula. The updated curriculum document replaces the term clerkship with experience, to allow for its use in nontraditional curricular structures. Other changes include a more streamlined list of symptom complexes, provision of a list of recommended clinical encounters, and incorporation of midrotation feedback. The hope is that these additions will provide a helpful resource to curriculum leaders in meeting national accreditation standards. The curriculum also includes new learning objectives related to cognitive bias, diagnostic errors, implicit bias, care for a diverse patient population, public health impact of neurologic disorders, and the impact of socioeconomic and regulatory factors on access to diagnostic and therapeutic resources.

Neurologic disorders are common and are the leading cause of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), accounting for 10.2% of global DALYs and 16.8% of global deaths.1 Diseases of the nervous system accounted for 9% of the primary diagnoses at office visits in the United States in 2014, according to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.2 Of the top 13 causes of DALYs in the United States in 2016, 6 (low back pain, Alzheimer disease, migraine, neck pain, ischemic stroke, and falls) are conditions that require the clinician to be able to perform and interpret a neurologic examination.3 Furthermore, projections suggest that due to aging of the American population, the number of US neurologists will be insufficient to provide care to this growing segment of patients.4

As a result, primary care and emergency physicians are—and will routinely be—called upon to evaluate and manage patients with neurologic disease. In addition, physicians in many other specialties need to recognize neurologic emergencies. Thus, physicians require a firm understanding of the general principles of clinical neurology. The most suitable setting in which to lay the foundation for that understanding is during the clinical phase of medical school.

Although a clinical neurology experience should be required of all medical students, the format of that experience may vary, depending on the organization of the overall curriculum at any given medical school. This document builds upon the 2002 Gelb et al.5 neurology clerkship core curriculum and outlines the key components of a clinical neurology experience. The purpose is not to define the specific structure of that experience or to dictate mandatory content. Rather, this curriculum is intended to provide the principles underlying the required clinical neurology experience and its fundamental content, as well as the procedural and analytical skills that medical students, regardless of their ultimate field of practice, should master by the time they graduate from medical school.

Goals and objectives of the clinical neurology experience

Definition of clinical neurology experience

A clinical neurology experience provides medical students with the opportunity to learn how to care for patients with neurologic symptoms and disorders through practical contact and observation. The experience should be centered on direct patient care, and should also provide formal education sessions and assessments. While most medical schools still provide this experience in a traditional clerkship format, some have introduced nontraditional models such as multidisciplinary clerkships or longitudinal experiences.6 These curriculum guidelines apply to a clinical neurology experience of any type, whether a traditional clerkship or an innovative format.

Goal

To teach the principles and skills necessary to recognize and manage the neurologic diseases a general medical practitioner is most likely to encounter in practice.

Objectives

The goal of teaching students to recognize and manage neurologic disease encompasses 2 categories of objectives: the procedural skills necessary to gather clinical information and communicate it and the analytical skills needed to interpret that information and act on it.

-

To teach and reinforce proficiency in the following procedural skills:

Interviewing to obtain a complete and reliable neurologic history

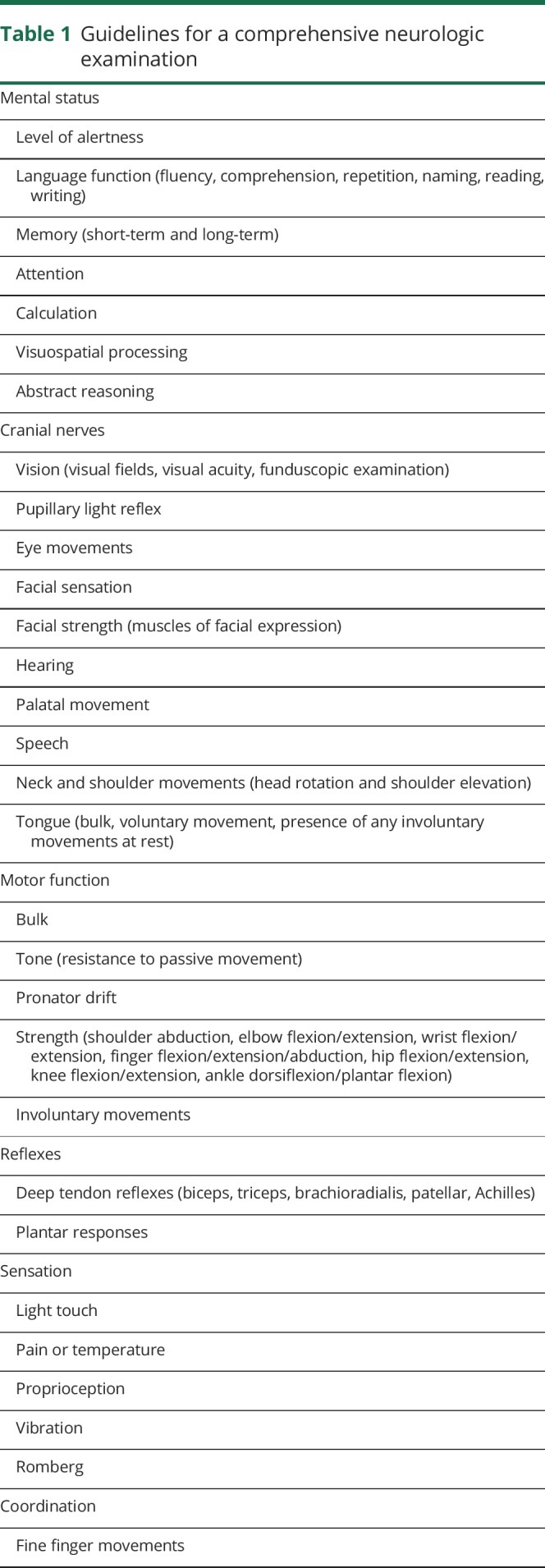

Performing a reliable neurologic examination (table 1)

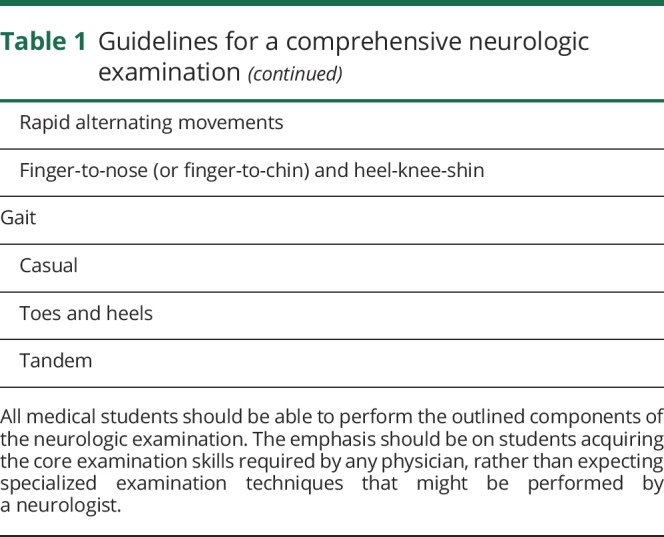

Examining patients with altered level of consciousness or abnormal mental status (table 2)

Delivering a clear, concise, and thorough oral presentation of a patient's neurologic history and examination

Preparing clear, concise, and thorough documentation of a patient's neurologic history and examination

Communicating empathetically with patients and families

[Ideally] Performing a lumbar puncture under direct supervision, or using simulation

-

To teach and reinforce proficiency in the following analytical skills:

Recognizing symptoms that may signify neurologic disease (including disturbances of consciousness, cognition, language, vision, hearing, equilibrium, motor function, somatic sensation, and autonomic function)

Identifying symptoms that may represent neurologic emergencies

Distinguishing normal from abnormal findings on a neurologic examination

Localizing the likely sites in the nervous system where a lesion may produce a patient's symptoms and signs

Formulating a differential diagnosis based on lesion localization, time course, and relevant historical and epidemiologic features

Explaining the indication, potential complications, and interpretation of common tests used in diagnosing neurologic disease

Demonstrating awareness of the principles underlying a systematic approach to the management of common neurologic diseases

Describing timely management of neurologic emergencies

Developing, presenting, and documenting a succinct, appropriate assessment and plan for the neurologic problem list

Recognizing situations in which it is appropriate to request neurologic consultation

Reviewing, interpreting, and applying pertinent medical literature to patient care

Understanding cognitive biases and their implications for diagnostic errors

Developing skills needed to deliver patient-centered, compassionate neurologic care with emphasis on diversity, inclusiveness, and recognition of implicit bias

Applying principles of medical ethics to patient care

Identifying socioeconomic and regulatory issues and other health disparities that may influence accessibility of affordable diagnostic and therapeutic resources

Explaining the public health impact of neurologic disorders

Table 1.

Guidelines for a comprehensive neurologic examination

Table 2.

Guidelines for the neurologic examination in patients with altered level of consciousness

Curriculum content

Any complex topic can be organized in a variety of ways, and there is no perfect order in which to teach the topic. For example, the traditional preclerkship curriculum at many medical schools is organ-based and students learn the anatomy, physiology, histology, and pathophysiology of one organ followed sequentially by instruction on the other organs. Other medical schools employ a discipline-based preclerkship curriculum, in which students study anatomy of all organs throughout the body, followed by the physiology, histology, and so on. Each approach has its advantages and disadvantages.7,8

Similarly, neurology educators have traditionally advocated a variety of approaches to organizing topics when teaching clinical neurology. Some stress the primacy of the neurologic examination and present clinical topics in the context of normal and abnormal examination findings. Others emphasize the importance of localization, and specifically the differentiation between focal and diffuse disease processes. Others maintain that the curriculum should center on a set of “scripts” for addressing a collection of common symptom complexes. Still others advocate pathophysiologic categories as the organizing principle. The following four sections represent alternative ways of organizing the same subject matter. Course directors may choose to emphasize some of these approaches more than others. The current curriculum guidelines are not meant to prescribe a particular way of presenting or organizing the material. However, all of the topics included in the following sections should be covered in some way.

The neurologic examination

As an integral component of the general medical examination:

Perform a pertinent, thorough neurologic examination (table 1)

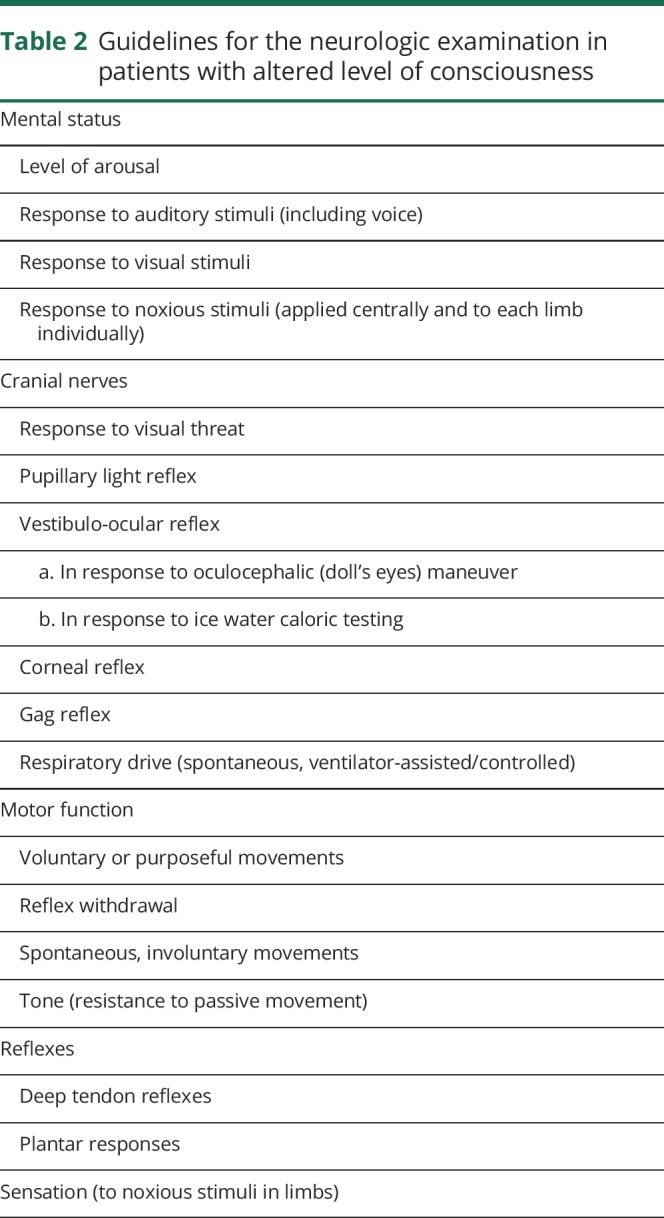

Perform a screening neurologic examination sufficient for detecting major neurologic dysfunction in asymptomatic patients (table 3)

Perform a neurologic examination on patients with an altered level of consciousness (table 2)

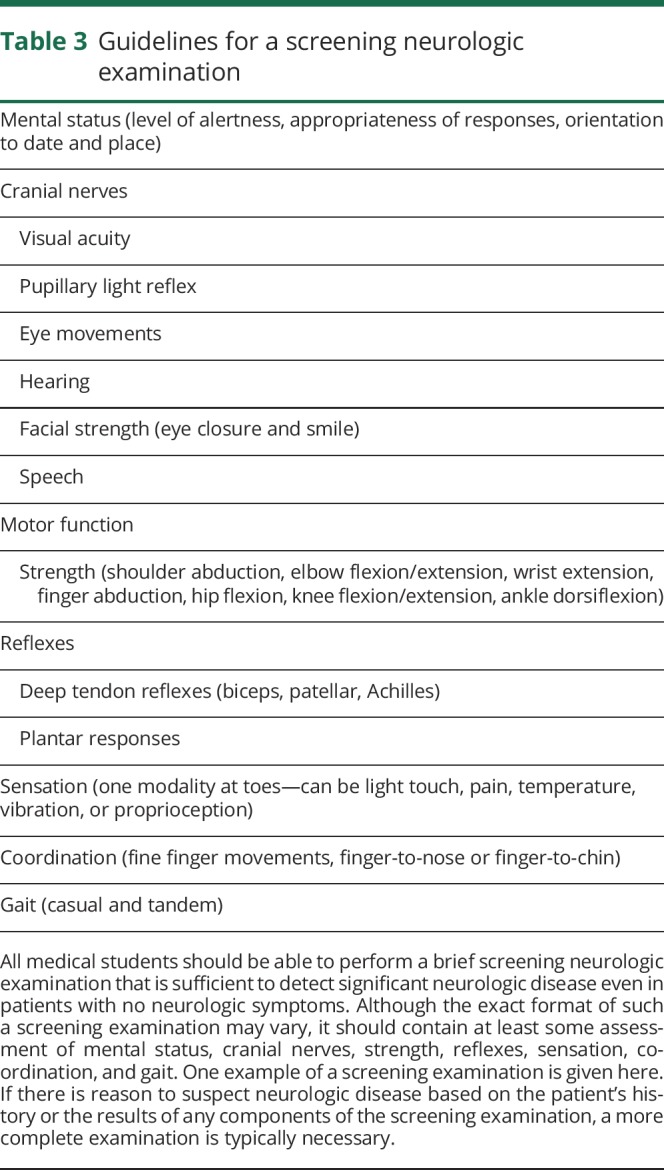

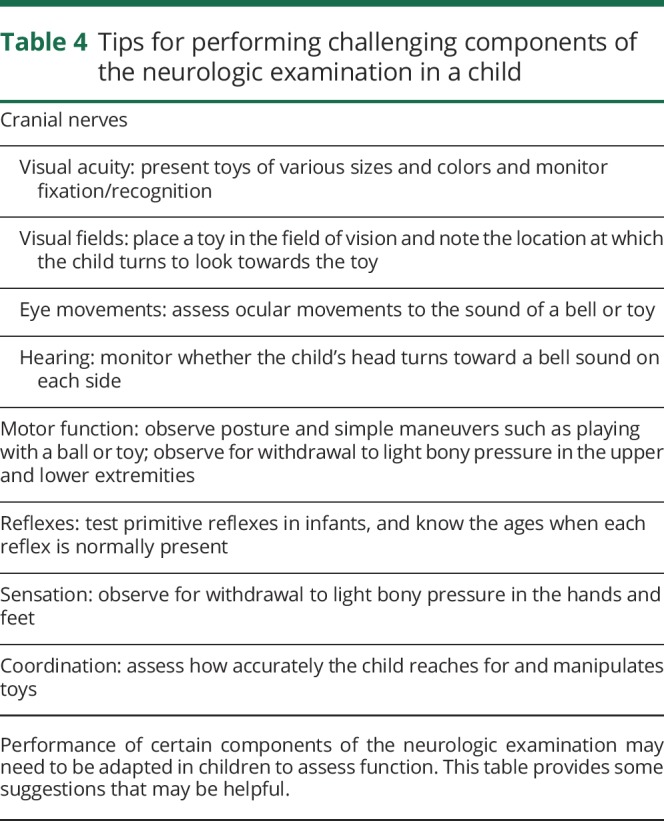

Know how to adapt the neurologic examination in young children (table 4)

Recognize and interpret abnormal findings on the neurologic examination

Demonstrate the use of techniques that ensure patient safety during the examination: some strategies include appropriate hand and instrument cleaning, single use of pins to test sensation, stabilizing position of the patient during muscle strength testing, and standing near the patient during the Romberg and gait examination

Table 3.

Guidelines for a screening neurologic examination

Table 4.

Tips for performing challenging components of the neurologic examination in a child

Localization

General principles differentiating lesions at the following levels:

Cerebral cortical and subcortical structures

Posterior fossa (brainstem and cerebellum)

Spinal cord

Anterior horn cell

Nerve root/plexus

Peripheral nerve (mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy, and mononeuropathy multiplex)

Neuromuscular junction

Muscle

Symptom complexes

A systematic approach to the evaluation and differential diagnosis of patients who present with:

Acute, subacute, or episodic changes in mental status or level of consciousness

Gradual cognitive decline

Aphasia

Headache or facial pain

Neck or back pain

Blurry vision or diplopia

Dizziness

Dysarthria or dysphagia

Weakness (focal or generalized)

Involuntary movements

Numbness, paresthesia, or neuropathic pain

Urinary or fecal incontinence/retention

Unsteadiness, gait disturbance, or falls

Sleep disorders

Delay or regression in developmental milestones

Approach to specific conditions

General principles for recognizing, evaluating, and managing the following neurologic conditions as important prototypes, or potentially disabling or life-threatening conditions:

-

1. Conditions that require prompt response

a. Acute stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or TIA

b. Acute vision loss

c. Brain death

d. CNS infection

e. Encephalopathy (acute or subacute)

f. Guillain-Barré syndrome

g. Head trauma

h. Increased intracranial pressure

i. Neuromuscular respiratory failure

j. Spinal cord dysfunction

k. Status epilepticus

l. Subarachnoid hemorrhage

2. Alzheimer disease

3. Bell palsy

4. Carpal tunnel syndrome

5. Epilepsy

6. Essential tremor

7. Headache (tension, migraine, cluster)

8. Multiple sclerosis

9. Myasthenia gravis

10. Myopathy

11. Parkinson disease

12. Polyneuropathy

Prerequisites for the trainee

Successful completion of the foundational curriculum of medical school should be demonstrated, including clinically relevant neuroanatomy, neuropathophysiology, neuropharmacology, and physical diagnosis.

Personnel needed for the training

Essential personnel

1. Course director (preferably board-certified or board-eligible neurologist)

2. Additional full-time academic faculty

3. Administrative coordinator for the course director

Desirable personnel

1. Adjunct clinical faculty

2. Neurology house staff

3. Advanced practice providers

4. Neuroscience nurses

Facilities needed for the training

Clinical sites (primary institution or other) for both outpatient and inpatient care should be available with adequate time and space to permit patient evaluation, teaching sessions, and performance assessments.

Methods of training

As with curriculum content, there are various teaching formats, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, educational experiences that revolve around actual patient contact have obvious relevance to the clinical issues students will encounter as practicing clinicians, but these experiences cannot be fully standardized. Simulated experiences, in contrast, can be standardized but they are inherently artificial. Patients who are “ideal” from the standpoint of having multiple abnormalities on neurologic examination may have rare neurologic diseases that are not immediately relevant to the types of conditions that most physicians will have to manage. There is no single ideal training format. The fundamental requirement is that at least some of the training must occur in the setting of actual patient care, under the supervision of teachers who specialize in neurology and who can apply the details of the individual patients to teach broader neurologic principles.

Essential

1. Required clinical encounters (appendix 1)

2. Supervised patient care encounters

3. Assessment of oral presentations and documentation

4. Teaching sessions

-

5. Material for independent study, including one or more of the following:

a. Locally generated syllabus

b. Published textbooks/references

c. Online resources

Optional

1. Formal lectures

2. Standardized patients

3. Simulation

Timetable for training

For adequate training, at least 4 weeks during the clinical phase of medical school is necessary. Ideally, students should be required to complete the neurology experience within the first 12 months of the clinical phase (e.g., in the traditional 4-year curriculum, a required, 4-week neurology experience in the third year is optimal).

Methods of summative evaluation of the trainee

Summative evaluation of medical student performance on clinical experiences should be multidimensional and at a minimum should include clinical performance evaluations and a knowledge assessment. Tools to evaluate students may include nationally written standardized examinations, locally developed examinations, locally developed clinical assessment forms with behavioral anchors based on learning objectives, bedside assessment evaluation forms, and oral presentation rubrics.6,9 The following list contains suggestions for various methods of evaluation.

Clinical performance evaluations by the trainers assessing:

1. Oral presentations and documentation

2. Fund of knowledge and clinical reasoning

3. Management skills and professionalism

4. Direct observation of the student interviewing and examining real patients or standardized patients

Examinations including one or more of the following:

1. Written

2. Online

3. Oral

4. Observed

Projects/assignments incorporating one or more of the following:

1. Self-directed learning

2. Evidence-based medicine

3. Graded history and physical

Methods of evaluation of the training process

In order to assess program effectiveness for departmental and institutional purposes, as well as for national accreditation, the clinical experience must be evaluated. This may be accomplished in several ways, which may be institution-specific or based on nationally administered examinations or questionnaires.

A. Student performance on standardized examinations

B. Student evaluations of the trainers

C. Student evaluations of the training experience

Mechanisms for formative feedback

Formative feedback should be timely, frequent, specific, and constructive, focused on performance and not character. Methods include:

A. Informal, spontaneous verbal discussion

B. Scheduled session with supervisors

C. Formal midrotation email or in-person session highlighting strengths and areas for improvement; any student performing below expected level should receive in-person feedback

D. Written comments on performance (e.g., on written presentations, via feedback cards)

E. Verbal comments on oral presentations

Faculty/resident orientation, instruction, and development

Personnel engaged in supervising students must receive information about the clinical experience including the goals, objectives, and expectations, as well as information that will enhance their roles as teachers and evaluators.

A. Annual distribution of course goals, objectives, and curriculum to all teachers

B. Development and review of expectations for residents to be involved with teaching (residents as teachers)

C. Periodic faculty development activities

D. Regular (at least annual) review by course director of student evaluations for faculty and resident performance

E. Biannual or annual report of faculty and resident performance to chair and residency program director, respectively

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the AAN's Education Committee for manuscript review.

Glossary

- DALY

disability-adjusted life-year

Appendix 1. Required clinical encounters for neurology experiences

Background

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) accreditation standards contain the following language:

The faculty of a medical school define the types of patients and clinical conditions that medical students are required to encounter, the skills to be performed by medical students, the appropriate clinical settings for these experiences, and the expected level of medical student responsibility.10

The LCME mandates that a system be established to specify the types of patients or clinical conditions that students must encounter and to monitor and verify the students' experiences with patients so as to remedy any identified gaps. The system, whether managed at the individual clerkship level or centrally, must ensure that all students have the required experiences. For example, if a student does not encounter patients with a particular clinical condition (e.g., because it is seasonal), the student should be able to remedy the gap by a simulated experience (such as standardized patient experiences or online or paper cases), or in another clerkship.

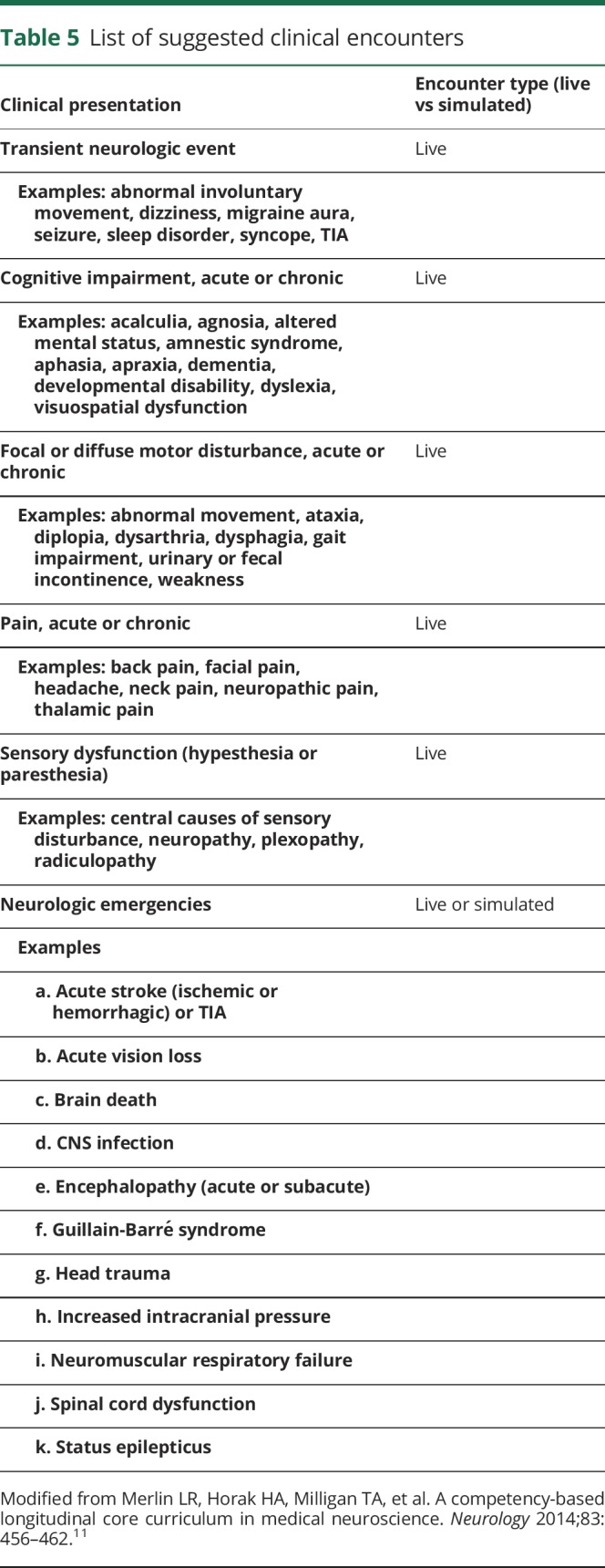

Recognizing that each medical school and clinical neurology experience will have individual needs and objectives, this resource is an American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommendation. It provides support and guidance for required neurology clinical encounter standards that are reflective of the AAN Core Curriculum Guidelines for Required Clinical Neurology Experience. Table 5 contains types of clinical presentations listed in 6 categories. A specific patient may satisfy more than one presentation category. Clerkship directors, in consultation with their local curriculum committees, may select any or all encounters from this list and may select other clinical experiences that are not on this list if they meet local needs.

Table 5.

List of suggested clinical encounters

Original work group members: Tracey Milligan, MD (work group leader); David Geldmacher, MD; Richard Isaacson, BA, MD; Rama Gourineni, MD; Daniel Menkes, MD, FAAN; Imran Ali, MD; Amy Pruitt, MD; James Owens, MD, PhD; Nancy Poechmann (AAN staff).

Updated by Joseph E. Safdieh, MD, FAAN; Yazmin Odia, MD; Douglas Gelb, MD, PhD, FAAN; Raghav Govindarajan, MD, FAAN; Madhu Soni, MD, FAAN.

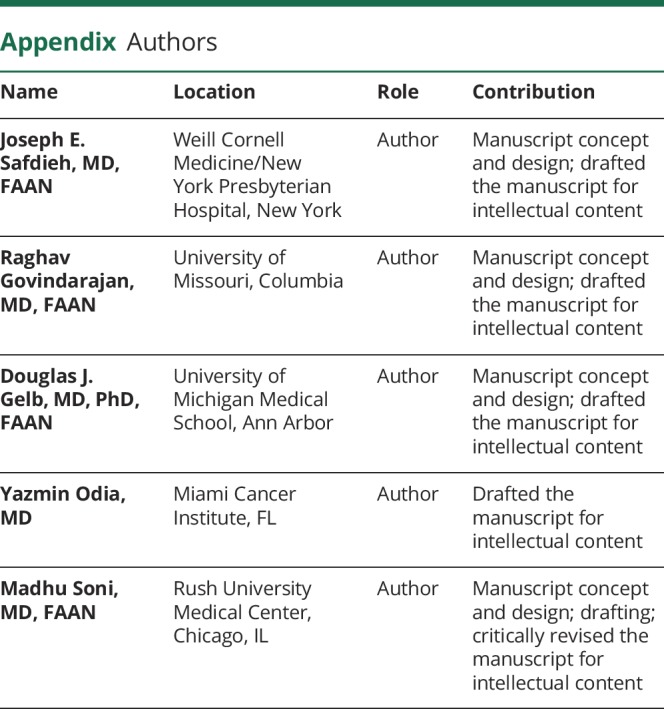

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 599

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

J. Safdieh: royalties from Elsevier, editorial stipend from American Academy of Neurology. R. Govindarajan reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. D. Gelb: royalties from Oxford University Press, UpToDate, and Medlink Neurology, stipend from American Academy of Neurology. Y. Odia and M. Soni report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:877–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. 2015 State and national summary tables. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2015_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed on February 28, 2018.

- 3.Murray CJL, Ballestros K, Echko M, the US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2016: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA 2018;319:1444–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dall T, Storm M, Charkrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology 2013;81:470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelb DJ, Gunderson CH, Henry KA, et al. Consortium of neurology clerkship directors and the undergraduate education subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology: the neurology clerkship core curriculum. Neurology 2002;58:849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safdieh JE, Quick AD, Korb PJ, et al. A dozen years of evolution of neurology clerkships in the United States: looking up. Neurology 2018;91:e1440–e1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brauer DG, Ferguson KJ. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Med Teach 2015;37:312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulasegaram KM, Martimianakis MA, Mylopoulos M, et al. Cognition before curriculum: rethinking the integration of basic science and clinical learning. Acad Med 2013;88:1578–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone RT, Mooney C, Wexler E, et al. Formal faculty observation and assessment of bedside skills for 3rd-year neurology clerks. Neurology 2016;21:10–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school. Available at: lcme.org/publications/#Standards. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 11.Merlin LR, Horak HA, Milligan TA, et al. A competency-based longitudinal core curriculum in medical neuroscience. Neurology 2014;83:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]