Abstract

Spores of Bacillus subtilis are encased in a protein coat composed of ∼80 different proteins. Recently, we reconstituted the basement layer of the coat, composed of two structural proteins (SpoVM and SpoIVA) around spore-sized silica beads encased in a lipid bilayer, to create synthetic spore-like particles termed ‘SSHELs’. We demonstrated that SSHELs could display thousands of copies of proteins and small molecules of interest covalently linked to SpoIVA. In this study, we investigated the efficacy of SSHELs in delivering vaccines. We show that intramuscular vaccination of mice with undecorated one micron-diameter SSHELs elicited an antibody response against SpoIVA. We further demonstrate that SSHELs covalently modified with a catalytically inactivated staphylococcal alpha toxin variant (HlaH35L), without an adjuvant, resulted in improved protection against Staphylococcus aureus infection in a bacteremia model as compared to vaccination with the antigen alone. Although vaccination with either HlaH35L or HlaH35L conjugated to SSHELs similarly elicited the production of neutralizing antibodies to Hla, we found that a subset of memory T cells was differentially activated when the antigen was delivered on SSHELs. We propose that the particulate nature of SSHELs elicits a more robust immune response to the vaccine that results in superior protection against subsequent S. aureus infection.

Keywords: spore display, Bacillus subtilis, SpoVM, SpoIVA, sporulation, synthetic biology

Delivery of a vaccine on artificial bacteria increased the efficacy of the vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus infection.

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus subtilis is a common Gram-positive, rod-shaped soil bacterium often used in microbiology as a model organism for the study of cellular differentiation and morphogenesis (Higgins and Dworkin 2012; Tan and Ramamurthi 2014). Under nutrient deprivation, B. subtilis divides asymmetrically producing genetically identical yet morphologically distinct daughter cells, consisting of a rod-shaped mother cell harboring an intracellular, roughly spherical, forespore, that undergo different cellular fates in a process called sporulation. A hallmark of sporulation is the deposition of ∼80 spore coat proteins, produced in the mother cell, onto the outer surface of the forespore, creating a thick proteinaceous shell that protects the mature spore from chemical and enzymatic perturbations (Henriques and Moran 2007; McKenney, Driks and Eichenberger 2013). The robust nature of the spore combined with the genetically tractable system in B. subtilis has spurred numerous investigations into applications wherein recombinant proteins are displayed on the surface of the spore via gene fusions to outer spore coat proteins. Such platforms have been useful in displaying enzymes for bioremediation (Wu, Mulchandani and Chen 2008; Hinc et al.2010) and industrial production (Florin et al.1991; Chen et al.2015a,b), small molecules and dyes for whole-cell bio sensing systems (Date, Pasini and Daunert 2010), and antigens for vaccines (Mauriello et al.2004; Duc le et al.2007; Isticato and Ricca 2014; Potocki et al.2017; Dai et al.2018).

Coat morphogenesis in B. subtilis initiates with the assembly of a basement layer around the forespore. The structural component of the basement layer is a protein termed SpoIVA (Roels, Driks and Losick 1992; Price and Losick 1999) that displays a multi-domain architecture (Castaing et al.2014). SpoIVA binds and hydrolyzes ATP to irreversibly polymerize around the forespore to form a stable platform for the proper assembly of the coat (Ramamurthi and Losick 2008; Castaing et al.2013). SpoIVA is tethered to the surface of the forespore via a small 26-aa protein, SpoVM (Levin et al.1993; Ramamurthi, Clapham and Losick 2006), that preferentially localizes to the forespore surface by recognizing its convex shape (Ramamurthi et al.2009; Gill et al.2015; Kim et al.2017). Recently, we reconstituted the basement layer of the coat around spherical supported lipid bilayers (SSLBs; (Bayerl and Bloom 1990; Gopalakrishnan et al.2009)) using purified SpoIVA and synthesized SpoVM peptide in the presence of ATP to create artificial spore-like particles termed synthetic spore husk-encased lipid bilayers (SSHELs; (Wu et al.2015)). By modifying SpoIVA on specific residues with so-called ‘click-chemistry’ reagents, we demonstrated that SSHELs could covalently display thousands of copies of small molecules and proteins of interest and proposed that these particles could be used as a versatile vaccine display platform, since they provided several potential benefits. Principally, SSHELs are composed entirely of defined materials, which eschew the use of a living organism, and can avoid complications arising from horizontal gene transfer or the use of extraneous components that may interfere with the function of a displayed entity.

Here we tested the ability of SSHELs to deliver a candidate vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus infection. Staphylococcus aureus is a leading bacterial pathogen in adult and pediatric populations, and its myriad clinical manifestations include soft-tissue infection, bloodstream infection and life-threatening pneumonia (Sheagren 1984a,b; Lowy 1998). The growing presence of antibiotic resistant strains combined with high morbidity and mortality have warranted novel approaches to combat this community-acquired and nosocomial pathogen (Dufour et al.2002; Gillet et al.2002; Kollef et al.2006). It has been shown that vaccination of mice with an inactive variant of the β-barrel, pore-forming alpha toxin protein (HlaH35L), a key virulence factor in S. aureus pathogenicity (O’Reilly et al.1986; Patel et al.1987), provides protection against S. aureus infection of the lung and skin (Menzies and Kernodle 1994; Bubeck Wardenburg and Schneewind 2008; Ragle and Bubeck Wardenburg 2009; Kennedy et al.2010). To assess the potential for SSHELs to serve as an antigen delivery platform, we created SSHEL::HlaH35L conjugates. We found that vaccination with SSHEL::HlaH35L induced HlaH35L-specific antibody and T cell responses in mice, and provided enhanced protection from S. aureus infection in a murine bacteremia model.

RESULTS

Assembly of SSHEL particles that covalently display a model vaccine

We recently described the in vitro reconstitution of the B. subtilis spore coat atop silica beads to construct synthetic spore-like particles that we termed ‘SSHELs’ (Wu et al.2015). To achieve this, we first applied a single phospholipid bilayer, composed of a mix of synthetic lipids that mimicked the composition of the E. coli plasma membrane, around 1 μm-diameter silica beads to build spherical supported lipid bilayers (SSLBs; Fig. 1A). Next, we added synthesized SpoVM peptide, and incubated the resulting SpoVM-coated SSLBs with purified SpoIVA protein in buffer containing ATP to drive polymerization of SpoIVA around the particles, to create SSHELs. The SpoIVA we employed was a fully functional cysteine-less variant into which we engineered a single N-terminal Cys residue, which we then modified with trans-cyclooctene (TCO) that undergoes a copper-free Diels-Alder ‘click chemistry’ reaction with tetrazine (Liang et al.2012) that allows for the covalent display of proteins on the surface of the SSHELs (Fig. 1A). To evaluate the utility of SSHELs as a vaccine display platform, we chose an inactive variant of S. aureus alpha-hemolysin protein (Hla) in which His35 was substituted with Lys, as a model antigen (Menzies and Kernodle 1994; Bubeck Wardenburg and Schneewind 2008; Kennedy et al.2010). Purified HlaH35L molecules, labeled with the fluorescent dye AlexaFluor488, were modified on free amines with tetrazine and conjugated onto SSHELs via the TCO modification on SpoIVA molecules (Fig. 1A). Epifluorescence microscopy of SSHELs conjugated with fluorescently labeled HlaH35L revealed that tetrazine-modified HlaH35L-AF488, but not HlaH35L-AF488 that was unmodified, coated the particles in a largely uniform pattern (Fig. 1B). Quantification of the fluorescence by flow cytometry and comparison to a known set of standards revealed that each SSHEL displayed a mean of approximately 12 000 molecules of equivalent soluble fluorescence (Fig. 1C). By considering the degree of labeling (see Material and Methods), we calculated that each SSHEL displays a mean of approximately 16 000 HlaH35L molecules (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Assembly of SSHELs that display a vaccine antigen. (A) Schematic of SSHEL assembly. 1 μm-diameter SiO2 beads (gray) are first encased in a phospholipid bilayer (yellow) to create spherical supported lipid bilayers (SSLBs). Next, synthesized SpoVM peptides (red) are added, which spontaneously bind to the SSLBs. The SpoVM-coated SSLBS are then incubated with purified SpoIVA (green) which, when incubated in buffer containing ATP, polymerizes irreversibly around the SSLBs to create SSHEL particles. Below: schematic of the click chemistry reaction in which TCO-derivatized SpoIVA reacts with antigen (blue star) derivatized with tetrazine to covalently display the antigen on the SSHEL surface. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of SSHELs constructed with TCO-derivatized SpoIVA incubated with AlexaFluor488 (AF488)-labeled HlaH35L molecules (left) or AlexaFluor488 (AF488)-labeled HlaH35L molecules derivatized with the cognate click chemistry reagent tetrazine (right). Top: fluorescence from AF488; bottom: overlay, fluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) to visualize particles. (C) Fluorescently labeled standards with a known quantity of AF488 molecules of equivalent soluble fluorescence (gray) and SSHELs displaying fluorescently labeled HlaH35L (green). MESF values are indicated above each peak.

SSHEL-based vaccination elicits protective immunity against S. aureus infection

Bacterial cells, including spores, that display vaccine antigens of interest have been shown to display an immune-stimulatory effect. This is presumably due to certain molecules harbored by the bacterium, termed ‘microbe-associated molecular patterns’ (Barnes et al.2007; Pan, Kim and Yun 2012). Furthermore, the particulate nature of the cells has been proposed to additionally contribute to this effect (Lebre et al.2017). To test the immunogenicity of undecorated SSHEL particles, which contain only silica, synthetic phospholipids, and two proteins, we immunized mice with SSHELs alone, or in combination with two different adjuvants: Monophosphoryl Lipid A (MPL-A: a Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 agonist derived from bacterial LPS) (Drachenberg et al.2001), or CpG ODN (CpG: TLR9-binding synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs) (Ramirez-Ortiz et al.2008). Mice were immunized every 2 weeks either intranasally (IN) or intramuscularly (IM) and dilutions of serum samples collected 2 weeks after each immunization were tested for SpoIVA-specific IgG content by ELISA. In mice vaccinated intranasally, three vaccinations were required to elicit a robust antibody response towards SpoIVA and the inclusion of adjuvant did not significantly alter the amount of anti-SpoIVA IgG detected (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a single vaccination via the IM route induced a strong SpoIVA-specific IgG response that was enhanced with each additional vaccination but not additionally enhanced by adjuvants (Fig. 2B). This suggested intrinsic immune stimulatory properties that we hypothesized could be harnessed to create an adjuvant-free vaccine platform that would elicit specific antibody responses against antigens displayed on its surface.

Figure 2.

Non-adjuvanted SSHELs elicit robust antibody response. SpoIVA-specific serum antibody levels from pooled serum samples of at least five unvaccinated mice (◊) or mice vaccinated intranasally (A) or intramuscularly (B) with SSHELs alone (Δ) or with CpG (•) or MPL-A (▪).

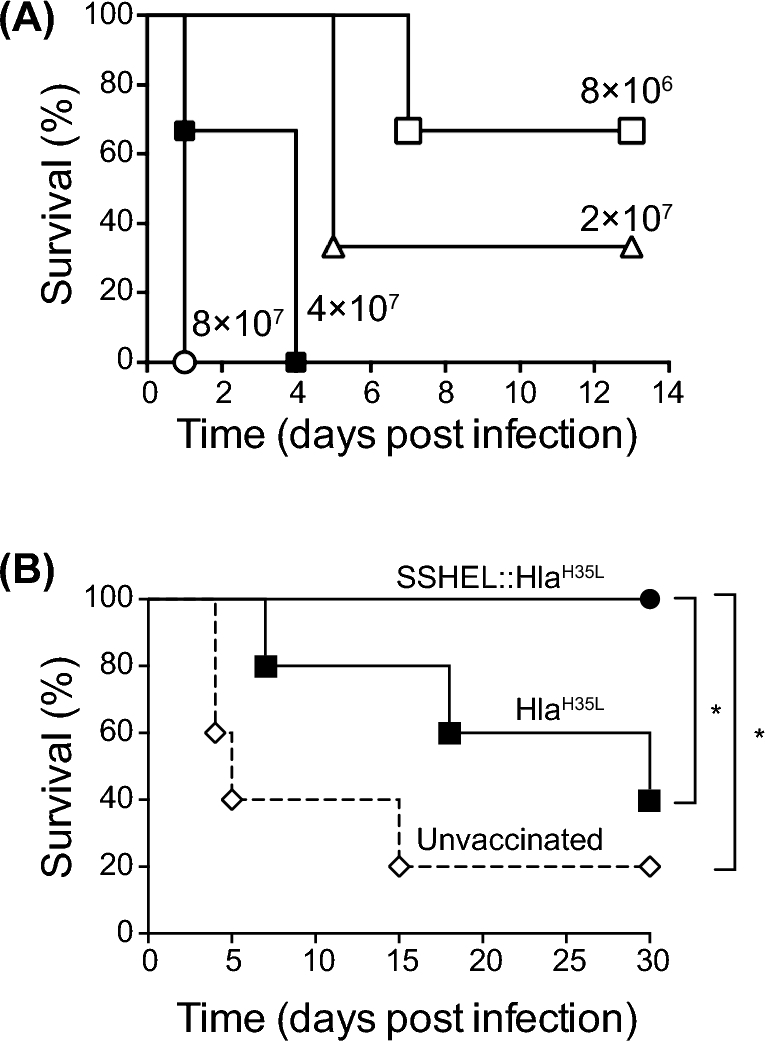

To test the ability of vaccine antigens displayed on SSHELs to protect against subsequent S. aureus infection, we first determined the optimal infection dose of S. aureus via the intravenous route. Infection of mice with 8 × 107 or 4 × 107 colony forming units (CFU) of S. aureus resulted in rapid killing of 100% of the mice in 4 days or less, but reducing the infection dosage to just 2 × 107 or 8 × 106 resulted in killing 33%–66% of mice, respectively (Fig. 3A). Given the relatively narrow infection dosage window that was optimal for delayed killing, we decided to perform challenge experiments after immunization with 3 × 107 CFU of S. aureus. Next, we immunized mice thrice intramuscularly, every 2 weeks, either with purified HlaH35L or with HlaH35L displayed on the surface of SSHELs (SSHEL::HlaH35L). Two weeks following the final immunization, we infected each mouse intravenously with 3 × 107 CFU of S. aureus and assessed the survival of the challenged mice for 30 days after infection. In this bacteremia challenge model, 80% of mock-immunized mice (n = 5) died within 15 days of infection using this inoculum (Fig. 3B). When immunized with pure HlaH35L, 40% of the mice were alive 30 days after challenge, consistent with the previous reports that HlaH35L conferred protection in staphylococcal pneumonia and skin infection models (Bubeck Wardenburg and Schneewind 2008). However, when immunized with SSHEL::HlaH35L, 100% of mice survived 30 days after infection. Interestingly, the total amount of HlaH35L used in the vaccination with SSHEL::HlaH35L was approximately 30-fold lower than the amount used in the vaccination with HlaH35L alone. We therefore conclude that display of the HlaH35L vaccine on SSHELs increased the protective efficacy of the vaccine, despite vaccinating with a lower amount of antigen.

Figure 3.

Display of HlaH35L on SSHELs enhances the protective efficacy of the vaccine in a S. aureus bacteremia infection model. (A) Percent survival of unvaccinated mice upon intravenous infection with 8 × 106 (■), 2 × 107 (Δ), 4 × 107 (▪) or 8 × 107 (○) CFU of S. aureus MRSA USA300 (n = 3 per group). (B) Percent survival of unvaccinated mice (◊), or mice vaccinated with SSHEL::HlaH35L (•) or HlaH35L (▪) upon intravenous infection with 3 × 107 CFU of S. aureus MRSA USA300. (n = 5 per group in one experiment; SSHEL::HlaH35L vs. unvaccinated: P = 0.013 and SSHEL::HlaH35L vs. HlaH35LP = 0.049).

SSHELs elicit a specific antibody response towards a displayed antigen

To test if the increased protective efficacy of SSHEL::HlaH35L was mediated by the humoral arm of the immune system, we assessed the capability of SSHELs to induce an antigen-specific antibody response towards HlaH35L. We therefore immunized the mice three times intramuscularly, every 2 weeks, with SSHELs, SSHEL::HlaH35L or HlaH35L and determined HlaH35L-specific serum IgG levels after each immunization. Immunization with either HlaH35L or SSHEL::HlaH35L, but not SSHELs alone, yielded similar levels of HlaH35L-specific antibodies after each round of immunization (Fig. 4A). To test if the antibodies were capable of neutralizing Hla activity, we incubated purified Hla with 2% rabbit blood cells in the presence of increasing dilutions of serum collected after each vaccination. Serum collected from mice immunized with either HlaH35L or SSHEL::HlaH35L neutralized the hemolytic activity of Hla to a similar extent (Fig. 4B). This data suggests that administration of HlaH35L displayed on SSHELs results in the production of Hla-neutralizing antibodies at least as well as vaccination with purified HlaH35L protein. Thus, the production of neutralizing antibodies alone was insufficient to explain the enhanced protection conferred by delivery of HlaH35L via SSHELs.

Figure 4.

SSHELs displaying HlaH35L elicit the production of Hla-neutralizing antibodies. (A) HlaH35L-specific serum antibody levels from pooled serum samples of five unvaccinated mice (◊), and mice vaccinated intramuscularly with SSHEL (Δ), SSHEL::HlaH35L (•) or with HlaH35L alone (▪) after one (left), two (middle) or three (right) vaccinations. Serum collected 2 weeks after last vaccination. (B) Neutralization of Hla-mediated hemolysis by serum samples collected after first (left), second (middle) and third (right) vaccination. Shown is the hemolytic activity of 1 ug/ml alpha toxin on 2% rabbit red blood cells (o) in the presence of pooled serum collected from at least five mice vaccinated with SSHEL (Δ), SSHEL::HlaH35L (•) or with HlaH35L alone (▪).

Vaccine delivery via SSHELs induced an antigen-specific T cell response

Since serum IgG levels and Hla neutralization were similar regardless of whether we immunized with SSHEL::HlaH35L or HlaH35L (Fig. 4A and B), we wondered if immunization with SSHEL::HlaH35L induced an antigen-specific T cell response that contributed to the improved protection. We therefore isolated splenocytes from mice immunized with either SSHEL::HlaH35L or HlaH35L as described above, and re-stimulated them ex vivo to assess the fraction of memory T cells that were IFNγ+, TNFα+, or IFNγ+ and TNFα+ using flow cytometry. After polyclonal restimulation with anti-CD3/CD28, the fraction of T cells that were IFNγ+, TNFα+ and IFNγ+ and TNFα+ isolated from mice immunized with SSHEL::HlaH35L exhibited a modest increase as compared to mice that were immunized with purified HlaH35L (Fig. 5A–C, center). After antigen-specific restimulation with HlaH35L, the fraction of cells from SSHEL::HlaH35L-immunized mice that were either TNFα+ or IFNγ+ and TNFα+ was significantly increased as compared to cells from mice immunized with HlaH35L (Fig. 5A–C, right). Induction of IL-17+ T cells was not detected (data not shown). Taken together, we conclude that presentation of the HlaH35L vaccine on SSHELs provides superior protection to subsequent S. aureus infection in a bacteremia model and that a T cell-mediated IFNγ and TNFα response may contribute to this protection.

Figure 5.

SSHELs induce an antigen-specific T cell response. (A–C) Frequency of indicated cytokine-secreting cells determined by flow cytometry of splenocytes from unvaccinated mice, and mice vaccinated with HlaH35L or SSEHL::HlaH35L 4 days after infection. Isolated cells were re-stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 or HLAH35L and gated on CD44+ Foxp3− CD4 T cells (n = 3–6 mice/group). Significant differences between groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney test: *: P ≤ 0.04; **: P ≤ 0.0098.

DISCUSSION

The use of bacteria, and especially bacterial spores, as a display platform and delivery vehicle for vaccines has been previously proposed and studied quite extensively (Ning et al.2011; Wang, Wang and Yang 2017; Bartels et al.2018). We suggest that the strategy presented in this report, using synthetic spores termed ‘SSHELs’ that were covalently decorated with vaccine antigens, may be used as an additional strategy in ongoing efforts to deliver vaccines on particles. SSHELs offer several advantages. Primarily, SSHELs are constructed entirely from defined components (silica, phospholipids and two proteins) and do not harbor any genetic material. Thus, concerns about horizontal gene transfer, release of genetically modified organisms into the environment, and the use of extraneous factors contained in a cell that may not be directly required for vaccine delivery are obviated. Second, although we herein reported the delivery of a single antigen, we envision that we could easily adapt the protocol to accommodate the covalent attachment of multiple antigens, in defined ratios, to permit the delivery of several vaccines at once. Finally, as reported previously for spore-displayed vaccines (Huang et al.2008), SSHEL-displayed vaccines can apparently elicit immune responses without the addition of adjuvants to stimulate the immune system. Given the relatively few components used to construct SSHELs, we propose that this feature is due to the particulate, roughly bacterial-sized, nature of the vehicle, which allows for interactions with professional antigen presenting cells that promote appropriate presentation of the vaccine epitopes. Indeed, in our studies, delivery of far fewer vaccine molecules per mouse resulted in the generation of similar levels of antibodies compared to delivery of the antigen alone, suggesting that display of vaccines on SSHELs may result in an intrinsic stimulation of the immune system.

A surprising result of our studies was the observation that, although vaccination of mice with SSHELs displaying HlaH35L produced a similar titer of neutralizing antibodies as vaccination with the antigen alone, vaccination with SSHEL-anchored HlaH35L resulted in a higher protective efficacy of the vaccine to subsequent infection with S. aureus in a bacteremia model. This suggested that an additional component of the immune system, beyond just antibody production, may contribute to this protection. Indeed, we observed that vaccination with SSHEL::HlaH35L resulted in increased activation of effector T cells that were IFNγ+ and TNFα+.

Further work will be needed to establish the relative contribution of antibody- and T cell-mediated immunity to the observed protection, but our results are consistent with the increasing appreciation that protective immunity against S. aureus involves both humoral and cellular responses and critically depends on the balance between IFNγ (Th1)- and IL-17 (Th17)-secreting T cells (Gaidamakova et al.2012; Karauzum et al.2017). Similarly, it was shown previously in a mouse pneumonia infection model that S. aureus induces T cells positive for IFNγ and IL-1β (Bubeck Wardenburg and Schneewind 2008), and that TNFα and IL-6 were induced in humans with culture-verified S. aureus septicemia (Soderquist, Sundqvist and Vikerfors 1992; Soderquist et al.1998). TNFα was also shown to enhance neutrophil killing of opsonized S. aureus (Bates, Ferrante and Beard 1991), possibly by the enhanced production of reactive oxygen species (Guerra et al.2017). Finally, the increase in IFNγ production we observed to correlate with the protective efficacy of SSHEL-delivered vaccine is consistent with the report that injection of purified recombinant IFNγ into mice 2 days prior or 3 days following inoculation with S. aureus significantly enhanced mouse survival, which was correlated to increased phagocytosis and bacterial clearance from liver and kidneys (Zhao, Nilsson and Tarkowski 1998). Thus, the ability of SSHEL-based vaccination to induce both T cell and antibody responses against displayed antigens suggests that it may represent a valuable vaccination strategy for those infections that require protective immunity mediated by both humoral and cellular responses.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Protein purification and labeling

His6-tagged SpoIVA single-cysteine variant was overproduced in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified using Ni2+ affinity chromatography (Qiagen), and subsequently by ion-exchange chromatography (MonoQ; Pharmacia) as described previously (Wu et al.2015). For purification of His6-tagged HlaH35L, hla was PCR-amplified from S. aureus chromosomal DNA and cloned into the pET28a vector (EMD Biosciences) using the 5΄ NcoI and 3΄ XhoI restriction sites. The H35L mutation was introduced into the hla gene using the Quikchange kit (Agilent). His6-HlaH35L was overproduced in exponentially growing E. coli BL21(DE3) in LB medium by addition of 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 37°C. Harvested cells were resuspended in Buffer A (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and disrupted by French press at ca. 12 500 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 30 000 × g and the clarified supernatant was loaded onto a Ni2+-NTA agarose affinity column equilibrated with Buffer A. The column was washed with 20 column volumes of Buffer A containing 20 mM imidazole, and finally eluted with Buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. His6-HlaH35L was next purified by size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex; Pharmacia). For click chemistry conjugation, SpoIVA was labeled with trans-Cyclooctene-PEG3- Maleimide (TCO), and HlaH35L was labeled with Methyltetrazin-PEG3-NHS ester kit as described by the manufacturer (Click Chemistry Tools). In brief, 20-fold molar excess of maleimide or NHS ester reagent was added to the protein samples and incubated overnight at 4°C, and the excess reagent was removed by Zeba Spin Desalting Column (Thermo Scientific). For labeling HlaH35L with AlexaFluor-488, HlaH35L was incubated with 3-fold molar excess of Alexa 488 Succinimidyl Ester (Life Technologies) for 1 h at room temperature and desalted with Zeba Spin Desalting Column prior to labeling with Methyltetrazine. Degree of labeling of AlexaFluor-488 to HlaH35A was estimated using absorbance measurements at A280 and A495, and a correction factor of 0.11 for AlexaFluor-488 dye (Molecular probes). Degree of labeling was calculated to be ∼0.7 AlexaFluor-488 molecules per HlaH35A protein.

SSLB preparation

SSLBs were made largely as previously described (Bayerl and Bloom 1990; Gopalakrishnan et al.2009). In brief, liposomes were produced by the liquid sonication method using 200 μl (10 mg/ml) of defined lipid components to mimic the composition of the E. coli plasma membrane: DOPE wt/wt 67%; DOPG wt/wt 23.2%; cardiolipin wt/wt 9.8% (Avanti), that were first evaporated under vacuum overnight at room temperature and hydrated in 1 ml ultrapure water. Resuspended lipids were subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles between ethanol-dry ice bath and 42°C water bath, followed by sonication until the suspension became transparent. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 13 000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant containing small unilamellar vesicles was retained. Silica beads (1 μm, 10 mg/ml) (PolySciences) were prepared for coating by washing three times each in 1 ml ultrapure water, followed by methanol and 1M NaOH. The beads were rinsed and resuspended in 200 μl ultrapure water. The SSLBs were constructed by mixing the silica beads with 400 μl prepared liposomes and 1 mM CaCl2, and incubated at 42°C for 30 min. After vortexing, SSLBs were collected by centrifugation at 13 000 g for 2 min, washed three times with ultrapure water and resuspended in 1 ml Buffer B (50 mM Tris and 400 mM NaCl at pH7.5).

SSHEL particle construction

SSHELs were constructed largely as described previously (Wu et al.2015). Briefly, SpoVM was synthesized as a 26-amino-acid peptide (Biomatik Corp.) and incubated at 10 μM (final concentration) with 6 mg/ml 1 μm-diameter SSLBs in 200 μl Buffer B, overnight at 25°C following a program of alternate shaking (750 rpm) and resting every 5 min. SpoVM coated SSLBs were collected by centrifugation at 13 000 × g for 1 min, and then incubated with ∼1.5 μM trans-cyclooctene labeled SpoIVA in a final volume of 400 μl Buffer B containing 10 mM MgC2 and 4 mM ATP, overnight at room temperature with gentle inversion covered from light. SSHEL particles were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 400 μl Buffer A (50 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.5) containing ∼1.5 μM methyltetrazine-labeled HlaH35L, and incubated overnight at room temperature with gentle inversion covered from light. SSHEL particles from multiple 400 μl samples were then collected by centrifugation and pooled together and washed thrice with 1 ml Buffer B. SSHELs were visualized using epifluorescence microscopy as previously described (Tan et al.2015). Briefly, 5 μl SSHEL suspensions were placed on a poly-d-lysine Coated Glass Bottom Culture Dish (Mattek Corp.) and covered by 1% agarose pad made with distilled water. Images were viewed and captured with a Delta Vision Core microscope with a Photometrics Coolsnap HQ2 camera (Applied Precision). Median fluorescence intensities for an entire SSHEL particle on a single plane were quantified using SoftWorx software. To estimate the number of Hla copies displayed on each SSHEL, the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of SSHEL particles containing AlexaFluor-488 labeled HlaH35L was measured using a BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva software. The median fluorescence intensities were converted to molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome (MESF) of the SSHELs via a standard curve relating the fluorescence peaks of commercial QuantumTM AlexaFluor-488 beads to their MESF values (Bangs Laboratories, Inc.); the estimated fluorophore to protein ratio (∼0.7) was used for calculating the HlaH35L copy number.

Preparation of inoculum for infection

For bacterial challenges, 20 ml of brain heart infusion broth (BHI, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) were inoculated with a swab of CA-MRSA USA300 (Los Angeles County clone, LAC) from a freshly streaked blood agar plate and culture was grown for 18 h at 37°C with shaking at 230 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at room temperature, the cell pellet was washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in PBS. Aliquots were prepared and stored at −80°C until further use. Aliquots were periodically thawed and plated to confirm CFU/ml after storage.

Animals

Female C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME. Starting age of mice in each experiment was 6 weeks for active vaccination studies. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and fed laboratory chow and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were conducted in compliance with guidelines approved by NIAID Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC).

Vaccination and infection

Mice were vaccinated intramuscularly (IM) into the hind limb three times at 2-week intervals with purified antigen or SSHELs (decorated with antigen, when applicable) in PBS or were left untreated. For S. aureus challenge experiments, mice were infected intravenously (IV) via the lateral tail vein with approximately 3 × 107 CFU of S. aureus USA300 in a volume of 200 μl PBS 2 weeks after last active vaccination. Animals were monitored for mortality and morbidity (weight loss, hunched posture, lethargy and ruffled fur) for up to 30 days post-infection. Non-vaccinated mice served as controls. Statistically significant differences in mortality between groups in bacterial challenge studies were analyzed by Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) Test using PRISM version 6.

ELISA

Blood samples were centrifuged in serum separator tubes and serum samples were stored at −80°C. Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp plates (Nunc) were coated with 100 ng/well of WT Hla (Biological Laboratories), purified HlaH35L, or purified SpoIVA diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked with Starting Block (Thermo Fisher) for 2 h at room temperature. Serum samples were prepared in semi-log dilutions in starting from 1:102 to 1:107 in a 96-well plate using Staring Block as diluent. Plates were washed three times and sample dilutions were applied in 100 μl volume/well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed thrice before applying the conjugate, goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L)-HRP, (Horse Radish Peroxidase) in a 1:2000 dilution. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature, washed as described above and incubated with TMB (3,3΄,5,5΄-tetramethylbenzidine) to detect HRP for 15 min. Optical density at 450 nm was measured using a VersamaxTM plate reader (Molecular Devices CA). Data analysis for full dilution curves was performed using Graph Pad PRISM 7.

Hla toxin neutralization assay

Hla neutralization assays were performed with rabbit red blood cells (RBCs) as previously described (Adhikari et al.2012). Briefly, a concentration of wildtype recombinant Hla that resulted in 100% lysis of RBCs was co-cultured with 2% rabbit RBCs in the presence or absence of serially diluted mouse sera. Cells were centrifuged and absorbance of supernatants was determined at 416 nm in a Beckman Coulter DTX 880 plate reader.

Cell isolation, in vitro stimulation and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of spleens were prepared by mechanical disruption and dispersion through 40-μm pore-size cell strainers. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer (Lonza), washed and once more filtered through 40-μm pore-size cell strainers. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (Life Technologies), at 2 × 106 cells per well in a 96-well plate and incubated in the presence or absence of anti-CDC3/CD28 or HlaH35L at 37°C, 5% carbon dioxide for 4 h in the presence of brefeldin A. Cells were then surface stained and fixed/permeabilized overnight, and intracellular staining was performed the next day. Antibodies against mouse surface and intracellular antigens, and cytokines (eBioscience, Biolegend, and BD Biosciences) were used in 10-color flow cytometry, either biotinylated or directly conjugated. The antibodies used were directed against CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD8 (clone 52–6.7), CD44 (clone IM7), Foxp3 (clone FJK-16s), CD45 (clone 30-F11), TNF-α (clone MP6-XT22), IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2) and IL-17A (clone 17B7). Near-infrared fixable live-dead cell stain (Molecular Probes) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. All data were acquired on a LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star) version 10.1r5.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the K.S.R. lab for comments on the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from the KRIBB Research Initiative Program (Korean Biomedical Scientist Fellowship Program), Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Republic of Korea (M.K.) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (S.K.D.) and National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (K.S.R.).

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Adhikari RP, Karauzum H, Sarwar J et al. Novel structurally designed vaccine for S. aureus alpha-hemolysin: protection against bacteremia and pneumonia. PLoS One 2012;7:e38567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes AG, Cerovic V, Hobson PS et al. Bacillus subtilis spores: a novel microparticle adjuvant which can instruct a balanced Th1 and Th2 immune response to specific antigen. Eur J Immunol 2007;37:1538–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels J, Lopez Castellanos S, Radeck J et al. Sporobeads: The utilization of the Bacillus subtilis endospore crust as a protein display platform. ACS Synth Biol 2018;7:452–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates EJ, Ferrante A, Beard LJ. Characterization of the major neutrophil-stimulating activity present in culture medium conditioned by Staphylococcus aureus-stimulated mononuclear leucocytes. Immunology 1991;72:448–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayerl TM, Bloom M. Physical properties of single phospholipid bilayers adsorbed to micro glass beads. A new vesicular model system studied by 2H-nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys J 1990;58:357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeck Wardenburg J, Schneewind O. Vaccine protection against Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Exp Med 2008;205:287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaing JP, Nagy A, Anantharaman V, Aravind L et al. ATP hydrolysis by a domain related to translation factor GTPases drives polymerization of a static bacterial morphogenetic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:E151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaing JP, Lee S, Anantharaman V et al. An autoinhibitory conformation of the Bacillus subtilis spore coat protein SpoIVA prevents its premature ATP-independent aggregation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2014;358:145–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang T, Sun T et al. Clostridium thermocellum nitrilase expression and surface display on Bacillus subtilis spores. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 2015a;25:381–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang T, Jia J et al. Expression and display of a novel thermostable esterase from Clostridium thermocellum on the surface of Bacillus subtilis using the CotB anchor protein. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2015b;42:1439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Liu M, Pan K et al. Surface display of OmpC of Salmonella serovar Pullorum on Bacillus subtilis spores. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date A, Pasini P, Daunert S. Fluorescent and bioluminescent cell-based sensors: strategies for their preservation. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 2010;117:57–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachenberg KJ, Wheeler AW, Stuebner P et al. A well-tolerated grass pollen-specific allergy vaccine containing a novel adjuvant, monophosphoryl lipid A, reduces allergic symptoms after only four preseasonal injections. Allergy 2001;56:498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duc le H, Hong HA, Atkins HS et al. Immunization against anthrax using Bacillus subtilis spores expressing the anthrax protective antigen. Vaccine 2007;25:346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour P, Gillet Y, Bes M et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in France: emergence of a single clone that produces Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin T, Neale G, Gibson GR et al. Metabolism of dietary sulphate: absorption and excretion in humans. Gut 1991;32:766–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidamakova EK, Myles IA, McDaniel DP et al. Preserving immunogenicity of lethally irradiated viral and bacterial vaccine epitopes using a radio- protective Mn2+-Peptide complex from Deinococcus. Cell Host Microbe 2012;12:117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill RL Jr., Castaing JP, Hsin J et al. Structural basis for the geometry-driven localization of a small protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:E1908–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 2002;359:753–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan G, Rouiller I, Colman DR et al. Supported bilayers formed from different phospholipids on spherical silica substrates. Langmuir 2009;25:5455–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra FE, Borgogna TR, Patel DM et al. Epic immune battles of history: Neutrophils vs. Staphylococcus aureus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017;7:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques AO, Moran CP Jr. Structure, assembly, and function of the spore surface layers. Annu Rev Microbiol 2007;61:555–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D, Dworkin J. Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis sporulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2012;36:131–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinc K, Ghandili S, Karbalaee G et al. Efficient binding of nickel ions to recombinant Bacillus subtilis spores. Res Microbiol 2010;161:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JM, La Ragione RM, Nunez A et al. Immunostimulatory activity of Bacillus spores. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2008;53:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isticato R, Ricca E. Spore surface display. Microbiol Spectr 2014;2: doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TBS-0011-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karauzum H, Haudenschild CC, Moore IN et al. Lethal CD4 T cell responses induced by vaccination against Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Infect Dis 2017;215:1231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AD, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Gardner DJ et al. Targeting of alpha-hemolysin by active or passive immunization decreases severity of USA300 skin infection in a mouse model. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1050–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Tyndall ER, Huang KC et al. Dash-and-Recruit mechanism drives membrane curvature recognition by the small bacterial protein SpoVM. Cell Syst 2017;5:518–526.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollef MH, Morrow LE, Niederman MS et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment patterns among patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 2006;129:1210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebre F, Sridharan R, Sawkins MJ et al. The shape and size of hydroxyapatite particles dictate inflammatory responses following implantation. Sci Rep 2017;7:2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin PA, Fan N, Ricca E et al. An unusually small gene required for sporulation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 1993;9:761–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Mackey JL, Lopez SA et al. Control and design of mutual orthogonality in bioorthogonal cycloadditions. J Am Chem Soc 2012;134:17904–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 1998;339:520–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriello EM, Duc le H, Isticato R et al. Display of heterologous antigens on the Bacillus subtilis spore coat using CotC as a fusion partner. Vaccine 2004;22:1177–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney PT, Driks A, Eichenberger P. The Bacillus subtilis endospore: assembly and functions of the multilayered coat. Nat Rev 2013;11:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies BE, Kernodle DS. Site-directed mutagenesis of the alpha-toxin gene of Staphylococcus aureus: role of histidines in toxin activity in vitro and in a murine model. Infect Immun 1994;62:1843–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning D, Leng X, Li Q et al. Surface-displayed VP28 on Bacillus subtilis spores induce protection against white spot syndrome virus in crayfish by oral administration. J Appl Microbiol 2011;111:1327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly M, de Azavedo JC, Kennedy S et al. Inactivation of the alpha-haemolysin gene of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4 by site-directed mutagenesis and studies on the expression of its haemolysins. Microb Pathog 1986;1:125–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan JG, Kim EJ, Yun CH. Bacillus spore display. Trends Biotechnol 2012;30:610–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AH, Nowlan P, Weavers ED et al. Virulence of protein A-deficient and alpha-toxin-deficient mutants of Staphylococcus aureus isolated by allele replacement. Infect Immun 1987;55:3103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potocki W, Negri A, Peszynska-Sularz G et al. The combination of recombinant and non-recombinant Bacillus subtilis spore display technology for presentation of antigen and adjuvant on single spore. Microb Cell Fact 2017;16:151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KD, Losick R. A four-dimensional view of assembly of a morphogenetic protein during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 1999;181:781–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragle BE, Bubeck Wardenburg J. Anti-alpha-hemolysin monoclonal antibodies mediate protection against Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect Immun 2009;77:2712–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi KS, Losick R. ATP-driven self-assembly of a morphogenetic protein in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Cell 2008;31:406–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi KS, Clapham KR, Losick R. Peptide anchoring spore coat assembly to the outer forespore membrane in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 2006;62:1547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthi KS, Lecuyer S, Stone HA et al. Geometric cue for protein localization in a bacterium. Science 2009;323:1354–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Ortiz ZG, Specht CA, Wang JP et al. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent immune activation by unmethylated CpG motifs in Aspergillus fumigatus DNA. Infect Immun 2008;76:2123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roels S, Driks A, Losick R. Characterization of spoIVA, a sporulation gene involved in coat morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 1992;174:575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheagren JN. Staphylococcus aureus. The persistent pathogen (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 1984a;310:1368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheagren JN. Staphylococcus aureus. The persistent pathogen (second of two parts). N Engl J Med 1984b;310:1437–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderquist B, Sundqvist KG, Vikerfors T. Kinetics of serum levels of interleukin-6 in Staphylococcus aureus septicemia. Scand J Infect Dis 1992;24:607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderquist B, Kanclerski K, Sundqvist KG et al. Cytokine response to staphylococcal exotoxins in Staphylococcus aureus septicemia. Clin Microbiol Infect 1998;4:366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan IS, Ramamurthi KS. Spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Environ Microbiol Rep 2014;6:212–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan IS, Weiss CA, Popham DL et al. A Quality-control mechanism removes unfit cells from a population of sporulating bacteria. Dev Cell 2015;34:682–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang Y, Yang R. Recent progress in Bacillus subtilis spore-surface display: concept, progress, and future. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2017;101:933–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Mulchandani A, Chen W. Versatile microbial surface-display for environmental remediation and biofuels production. Trends Microbiol 2008;16:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu IL, Narayan K, Castaing JP et al. A versatile nano display platform from bacterial spore coat proteins. Nat Commun 2015;6:6777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YX, Nilsson IM, Tarkowski A. The dual role of interferon-gamma in experimental Staphylococcus aureus septicaemia versus arthritis. Immunology 1998;93:80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]