Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Pregnancies with congenital heart disease in the foetus have an increased prevalence of pre-eclampsia, small for gestational age and preterm birth, which are evidence of an impaired maternal–foetal environment (MFE).

METHODS

The impact of an impaired MFE, defined as pre-eclampsia, small for gestational age or preterm birth, on outcomes after cardiac surgery was evaluated in neonates (n = 135) enrolled in a study evaluating exposure to environmental toxicants and neuro-developmental outcomes.

RESULTS

The most common diagnoses were transposition of the great arteries (n = 47) and hypoplastic left heart syndrome (n = 43). Impaired MFE was present in 28 of 135 (21%) subjects, with small for gestational age present in 17 (61%) patients. The presence of an impaired MFE was similar for all diagnoses, except transposition of the great arteries (P < 0.006). Postoperative length of stay was shorter for subjects without an impaired MFE (14 vs 38 days, P < 0.001). Hospital mortality was not significantly different with or without impaired MFE (11.7% vs 2.8%, P = 0.104). However, for the entire cohort, survival at 36 months was greater for those without an impaired MFE (96% vs 68%, P = 0.001). For patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, survival was also greater for those without an impaired MFE (90% vs 43%, P = 0.007).

CONCLUSIONS

An impaired MFE is common in pregnancies in which the foetus has congenital heart disease. After cardiac surgery in neonates, the presence of an impaired MFE was associated with lower survival at 36 months of age for the entire cohort and for the subgroup with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease, Cardiac surgery, Foetus, Pregnancy complications, Maternal–foetal environment

INTRODUCTION

The placenta plays a key role in the development of a foetus in a normal maternal–foetal environment (MFE) setting [1, 2]. Poor growth of the foetus, maternal complications and preterm birth (PTB) are signs of an impaired MFE. Gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia (PE), small for gestational age (SGA) and PTB are associated with neonatal mortality and morbidity in newborns without congenital heart disease (CHD). Maturation of organ systems continues throughout late gestation [3]. PE, SGA and PTB (even by a few weeks) result in functional immaturity of multiple organ systems; PE is associated with increased neonatal mortality [4], and SGA is associated with impaired heart and lung function [5–8]. There is increasing evidence that the placenta and MFE are abnormal in many foetuses with CHD [9–11]. Pregnancies with CHD in the foetus have an increased prevalence of PE, SGA and PTB [12–14]. PTB and SGA have been associated with increased early mortality and morbidity after cardiac surgery in neonates [15–17]. We hypothesized that an impaired MFE (defined as the presence of gestational hypertension/PE, SGA or PTB) would have an adverse impact on early and intermediate-term outcomes in neonates undergoing cardiac surgery.

METHODS

The study cohort comprised neonates enrolled in a prospective observational study of the impact of prenatal exposure to environmental toxicants on neuro-developmental outcomes after cardiac surgery. The inclusion criterion was CHD necessitating cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass prior to 44 weeks completed post-conception age. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) a known genetic syndrome, (ii) a major extracardiac anomaly and (iii) language other than English spoken at home. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all the participants.

Details of the prenatal course and perioperative outcomes were documented from medical records. As part of the parent study, surviving subjects underwent neuro-developmental evaluation at 18 months of age. Survival data and vital status were ascertained from medical records and contact with the parents or guardians.

For the purpose of this study, an impaired MFE was considered to be present if one or more of the following occurred: gestational hypertension, PE, SGA or PTB. Gestational hypertension was defined as 2 blood pressure measurements higher than 140/90 mmHg at least 4 h apart at >20 weeks gestational age. PE was defined as gestational hypertension with proteinuria or end-organ (liver or kidney) injury. SGA was defined as birthweight below the 10th percentile for gestational age. PTB was defined as birth prior to 37 weeks gestational age. Placental weight, birthweight and foetal echocardiography data were obtained from prenatal and birth records. Placental weights and foetal echocardiography data were not available for infants followed up prenatally or born at other institutions and for those without a prenatal diagnosis of CHD. The umbilical artery pulsatility index (PI) and the umbilical artery systolic/diastolic ratio (S/D) from the foetal echocardiogram at the last prenatal visit were used to assess placental vascular resistance and potential abnormal perfusion.

Patients were evaluated by a genetic dysmorphologist. Genetic testing was performed as indicated. Neonatal recognition of dysmorphic features may be difficult; therefore, some patients were enrolled for whom the diagnosis of a genetic syndrome was not made until the 18-month neuro-developmental evaluation. Patients were classified as having no definite genetic syndrome or chromosomal abnormality (‘normal’) or as having a definite or suspected genetic syndrome or chromosomal abnormality (‘abnormal/suspected’).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis proceeded in 2 discrete stages, a descriptive phase and an inferential phase. To fully familiarize ourselves with the data, and because of the non-normative nature of many of the distributions, parametric as well as non-parametric measures of central tendency (mean and median) and variability (standard deviation and interquartile range) were computed for all relevant variables in the data set, with a specific emphasis on the MFE variables. When foetuses were used as the unit of analysis, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to test for differences between those with and without impaired MFEs for umbilical artery PI, umbilical artery S/D and placental weight. However, when infants were used as the unit of analysis, both Fisher’s exact test (for gender, race, cardiac diagnosis, genetic anomaly and hospital survival) and Wilcoxon rank-sum difference test were used [for gestational age, birthweight and postoperative length of stay (LOS)], depending on the characteristics of the data. Mortality rates were estimated for babies from impaired and non-impaired MFEs using the Kaplan–Meier survival curves and then compared using log-rank tests, for the cohort as a whole as well as the hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) subsample. Mortality was defined as death at the last follow-up with time 0 defined as the date of birth. The criterion for statistical significance was at an unadjusted α = 0.05 level. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Between 8 September 2011 and 13 August 2015, 140 neonates were enrolled in the primary study. Of these, 135 underwent cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass prior to 44 weeks completed post-gestational age and formed the study population. Subject characteristics of the cohort are listed in Table 1. The cohort was largely male (59%) and Caucasian (77%). The most common cardiac defects were transposition of the great arteries (TGA, 35%) and HLHS (32%). Suspected or definite genetic anomalies were identified in 25% of neonates. Demographic and patient-specific factors are listed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Subject characteristics

| Variables | Impaired (n = 28) |

Non-impaired (n = 107) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Continuous factors | ||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 37.1 (1.3) | 37.1 (36.4–38.0) | 39.1 (0.8) | 39.2 (38.9–39.9) |

| Placental weight (g) | 425.1 (163.8) | 414.0 (340.0–448.0) | 460.1 (116.1) | 450.0 (382.0–516.0) |

| Birthweight (kg) | 2.6 (0.4) | 2.5 (2.3–2.8) | 3.4 (0.4) | 3.4 (3.1–3.6) |

| Postoperative length of stay (days) | 38.1 (65.2) | 20.0 (13.5–26.0) | 14.2 (14.4) | 10.0 (7.0–14.0) |

| Categorical factors | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 23 (82) | 57 (53) | ||

| Female | 5 (18) | 50 (47) | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 17 (61) | 87 (81) | ||

| Black | 4 (14) | 5 (5) | ||

| Other | 7 (25) | 15 (14) | ||

| Hospital mortality | ||||

| Yes | 3 (11) | 3 (3) | ||

| No | 25 (89) | 104 (97) | ||

| Type of CHD | ||||

| HLHS | 13 (46) | 30 (28) | ||

| TGA | 2 (7) | 45 (42) | ||

| TOF | 3 (11) | 7 (7) | ||

| Truncus arteriosus | 1 (4) | 5 (5) | ||

| IAA/VSD | 2 (7) | 5 (5) | ||

| Other | 7 (25) | 15 (14) | ||

| Genetic anomaly | ||||

| None | 21 (75) | 80 (75) | ||

| Suspected | 4 (14) | 15 (14) | ||

| Definite | 3 (11) | 12 (11) | ||

CHD: congenital heart disease; HLHS: hypoplastic left heart syndrome; IAA: interrupted aortic arch; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; TGA: transposition of the great arteries; TOF: tetralogy of Fallot; VSD: ventricular septal defect.

An impaired MFE was present in 28 (21%) subjects. SGA was the most common adverse outcome of an impaired MFE and occurred in 17 of 135 (13%) subjects. It is important to recognize that SGA is not equivalent to low birthweight as the birthweight was ≥2500 g for 8 of 17 (47%) subjects who met the criterion for foetal growth restriction. SGA is defined as a birthweight <10th percentile for gestational age. It is not a specific weight. Low birthweight is commonly defined as a birthweight <2500 g. Depending on the gestational age at birth, a baby may weigh more than 2500 g but still meet the criterion for SGA. The second most common condition associated with impaired MFE was PTB that occurred in 10 of 135 (7%) subjects. Gestational hypertension occurred in 3 of 135 (2%) pregnancies and PE in 7 (5%). In 7 of 28 (25%) pregnancies with an impaired MFE, more than one diagnostic criterion was present.

The last foetal echocardiogram was performed at a median of 36.4 weeks gestational age (30–39 weeks). Umbilical artery PI (n = 108, 1.21 ± 0.36 vs 1.03 ± 0.22, P = 0.012) and the umbilical artery S/D (n = 108, 3.45 ± 1.35 vs 2.84 ± 0.65, P = 0.015) were higher for foetuses with an impaired MFE, consistent with increased placental vascular resistance and altered perfusion. Placental weight (n = 110) was lower for babies with an impaired MFE compared with those without evidence of an impaired MFE (425 ± 164 vs 460 ± 116 g, P = 0.046).

Patients with impaired MFE were more likely to be male and non-Caucasian than those without evidence of impaired MFE (P = 0.009 and P = 0.044, respectively) (Table 1). The occurrence of impaired MFE was similar for all types of CHD, except TGA (P = 0.006). An impaired MFE was identified in 30% of HLHS patients; 29% of those with interrupted aortic arch/ventricular septal defect; 4% of those with TGA; 30% of those with tetralogy of Fallot; 17% of those with truncus arteriosus; and 32% of those with other types of CHD. As would be expected from the diagnostic criteria for an impaired MFE, gestational age and birthweight were lower for babies with an impaired MFE (both P < 0.001). Occurrence of an impaired MFE did not vary if there was a suspected or confirmed genetic anomaly (P = 1.000).

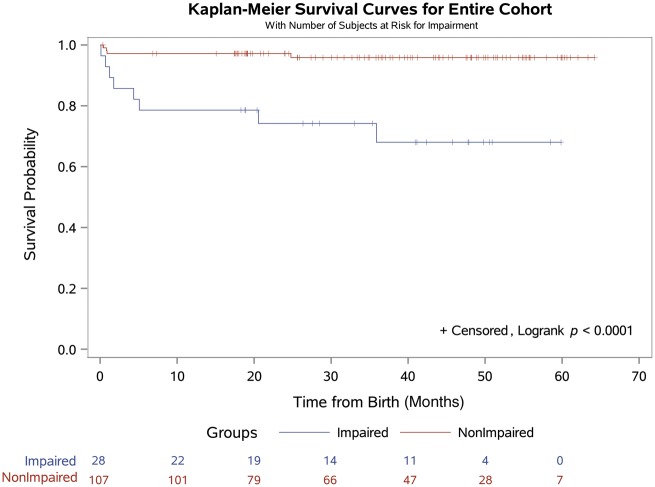

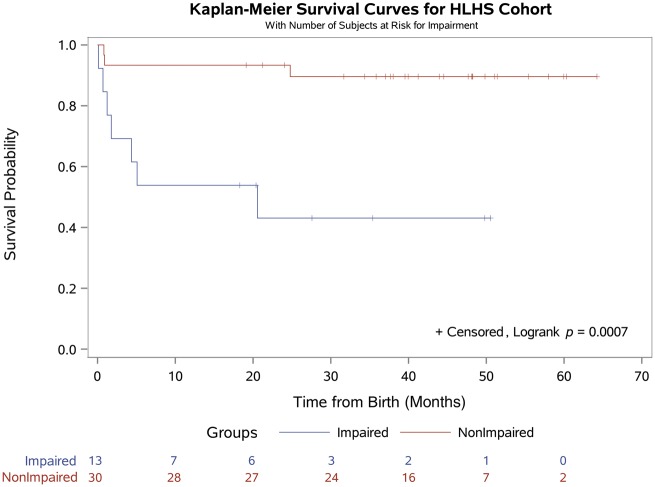

Postoperative LOS was shorter for subjects without an impaired MFE (14 ± 14 vs 38 ± 65 days, P < 0.001). There were 6 early deaths, 3 of 28 (10.7%) among patients with evidence of an impaired and 3 of 107 (2.8%) among those without evidence of an impaired MFE. However, hospital mortality did not differ between the 2 groups (P = 0.104). The survivors have been followed up for a median of 37 months (0.4–64.2 months). There have been 6 late deaths and 5 of 6 occurred in patients with an impaired MFE. For the entire cohort, survival at 36 months was significantly lower for those with impaired MFE compared with a normal MFE (68% vs 96%, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). For patients with HLHS, survival at 36 months was also significantly lower for those with impaired MFE (43% vs 90%, P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Figure 1:

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for the entire cohort (n = 135) stratified by the presence or absence of an impaired maternal–foetal environment.

Figure 2:

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for the subgroup of patients with HLHS (n = 43) stratified by the presence or absence of an impaired maternal–foetal environment. HLHS: hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that an impaired MFE characterized by gestational hypertension, PE, SGA and PTB is common in neonates with complex CHD, and depending on the specific type of CHD, impairment may be present in up to 30% of neonates. The occurrence of impaired MFE was similar for most types of CHD, except TGA. In addition, the presence of a known genetic anomaly did not alter the risk for an impaired MFE. PE and SGA are thought to result from placental dysfunction, and there is evidence that placental malperfusion may also be a cause of PTB [18]. In our study, newborns with impaired MFE had lower placental weights and increased umbilical artery PI, which are markers of placental insufficiency. The possibility of a common mechanism for placental insufficiency and CHD, perhaps related to abnormal angiogenesis, has been suggested by other investigators [12, 19, 20]. Presence of an impaired MFE was associated with prolonged hospitalization after cardiac surgery and significantly worse intermediate-term survival, both for the entire cohort and patients with HLHS. Previous studies have shown that SGA and PTB are associated with increased mortality and morbidity early after cardiac surgery in neonates [15–17]. This study demonstrates that the adverse effects of an impaired MFE extend long after the neonatal period. It is possible that impairment of the MFE results in functional immaturity of multiple organ systems. Furthermore, multiple studies have also shown abnormal structure and function of the heart in foetal growth restriction foetuses, leading to decreased biological reserve and thus lower survival after cardiac surgery in neonates [5, 21].

There is increasing evidence that the MFE and placenta are abnormal in many foetuses with CHD and adversely affect the development of the foetus. We recently collaborated with investigators from Denmark to investigate the impact of CHD on foetal cerebral growth. In a nationwide cohort encompassing all 924 422 live-born Danish singletons from 1997 to 2011, including 5519 with CHD, mean head circumference was smaller in children with CHD [22]. Several subtypes of CHD were associated with smaller head circumferences, including HLHS, other single-ventricle CHD, TGA, tetralogy of Fallot, atrioventricular septal defects and major ventricular septal defects. Overall, the birthweight z-score was modestly smaller than the head circumference z-score in all children with CHD. In the same cohort, we evaluated the associations between all major subtypes of CHD and placental weight at birth, and the association between placental weight and measures of both overall and cerebral growth in foetuses with CHD [9]. Placental weight z-score was associated with birthweight and head circumference z-scores in all subtypes. Interestingly, tetralogy of Fallot, double-outlet right ventricle and major ventricular septal defects were significantly associated with smaller placental size at birth.

Andescavage et al. [10] used 3D volumetric magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate the placenta in foetuses with CHD and showed that impaired placental growth in CHD was associated with younger gestational age and lower birthweight at delivery [10]. They concluded that decreased placental growth in the CHD foetus may be associated with impaired foetal growth and premature delivery, each outcome an independent risk factor for neonatal mortality and morbidity [10]. Cedergren and Kallen [23] evaluated the outcomes of pregnancies with an infant affected by CHD in a prospective population-based cohort study from Sweden (1992–2001). Outcomes for 6346 singleton pregnancies with infants affected by CHD were compared with all delivered women. In the cohort of infants with CHD, there were significantly increased risks of PE, SGA, Caesarean section or instrumental delivery, PTB, meconium aspiration and foetal distress [23]. Foetal thrombotic vasculopathy is characterized by regionally distributed avascular villi and is often accompanied by thrombosis in placental foetal vessels [24]. Jones et al. [25] investigated placental histopathology in foetuses with CHD. Compared with controls, gross pathology of HLHS cases demonstrated significantly reduced placental weight and increased fibrin deposition. Histological examination showed decreased terminal villi, reduced vasculature and increased leptin expression in syncytiotrophoblast and endothelial cells.

It is increasingly being recognized that CHD in the foetus may adversely affect the health of the mother. For example, pregnancies with foetal CHD have an increased prevalence of PE. Brodwall et al. [12] investigated the association between maternal PE and offspring risk of severe CHD using the Medical Birth Registry of Norway, 1994–2009. When adjusting for potential confounders, the risk ratio for severe CHD in the offspring of mothers with any PE was 1.3 (95% confidence interval 1.1–1.5), and in pregnancies with early-onset PE, the risk ratio was 2.8 (95% confidence interval 1.8–4.4). Auger et al. [26] investigated the relationship between CHD and PE using population-based data from Quebec. They found an elevated prevalence of heart defects among infants of women with PE compared with no PE. Women with early-onset PE had significantly greater prevalence of infants with CHD, whereas women with late onset had only marginally greater prevalence [26].

Several studies have shown that foetal CHD impairs foetal growth, which in turn adversely affects surgical outcomes. Malik et al. [27] used data from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study to evaluate live singleton infants born with CHD. After controlling for maternal and infant covariates, infants with CHD were more likely to be SGA than infants without CHD. In the Paediatric Heart Network (PHN) Infant Single Ventricle (ISV) Trial, SGA occurred in 22% of infants with single ventricle (SV) compared with 10% of normal neonates [14]. Graf et al. [16] evaluated the impact of SGA on cardiac surgery outcomes in a cohort of 41 patients in a case–control study. SGA was associated with increased operative mortality [16] as well as an increased incidence of major postoperative complications including prolonged LOS, prolonged mechanical ventilation, postoperative cardiac arrest and postoperative infection. Hospital charges for the patients with SGA were considerably higher than for the control patients. Sochet et al. [17] evaluated the importance of SGA status in the risk assessment of infants with CHD in a cohort of 230 infants undergoing cardiac surgery. Thirty-day mortality was significantly greater in SGA infants (14% vs 3.5%, P < 0.005). Importantly, SGA infants with normal birthweight (> 2500 g) were also at increased risk of 30-day mortality compared with appropriate for gestational age infants (P < 0.045). However, they did not find that SGA status was associated with longer LOS or increased postoperative complications.

PTB is common in CHD and, not surprisingly, is associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse outcomes after surgery for CHD. In the PHN ISV Trial, PTB occurred in 16% of infants with SV compared to 10% of normal neonates [14]. Cnota et al. [28] investigated the impact of gestational age and risk of death using 2000–03 national linked birth/infant death cohort data sets from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). CHD deaths occurred in 4736 infants (0.04%) born between 34 weeks and 40 weeks. There was a significant, negative linear relationship between CHD death rate and gestational age (R2 = 0.97). Laas et al. [13] used data from the French National Perinatal Survey of 2003 to compare the incidence of PTB in infants with and without CHD. Of the infants with CHD, 13.5% were born preterm. The odds of PTB for infants with CHD were 2-fold higher than for the general population primarily due to an increase in spontaneous PTB. The risk of PTB persisted after exclusion of patients with chromosomal or other anomalies. Costello et al. [29] from Boston Children’s Hospital studied 971 consecutive infants with CHD. Compared with a reference group of neonates born at 39–40 completed weeks of gestation, neonates born at earlier gestational ages had significantly increased mortality and tended to require a longer duration of mechanical ventilation. These findings were later confirmed in a multi-institutional study using the Society Thoracic Congenital Heart Surgery National Database [15]. Compared with a 39.5-week gestational age reference group, birth at 37 weeks or earlier gestational age was associated with greater in-hospital mortality. In addition, complication rates were higher and postoperative LOS was significantly prolonged for those born at 37 and 38 weeks of gestation.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The sample size is relatively small, which may limit the ability to identify the risk factors for an impaired MFE. Because the parent study was focused on neuro-developmental outcomes, the study excluded subjects with known genetic syndromes and major extracardiac anomalies that may limit the generalizability. Foetal echocardiography data and placental weights were not available for all subjects. Finally, there are other factors that may impact the risk of an impaired MFE, which were not evaluated including maternal diabetes, tobacco exposure, multiple gestation, advanced maternal age and socio-economic status.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we found that an impaired MFE is common in pregnancies in which the foetus has CHD and encompasses more factors than just low birthweight or PTB. These data support the possibility of a common mechanism for placental insufficiency and CHD. Our findings also support the hypothesis that impairment of the MFE results in functional immaturity and abnormal development of multiple organ systems, leading to decreased biological reserve and thus lower survival after cardiac surgery in neonates. The presence of an impaired MFE was associated with prolonged LOS after surgery and a trend towards increased hospital mortality. Importantly, the impact of an impaired MFE appears to extend for years after the initial surgery. After cardiac surgery in neonates, the presence of an impaired MFE was associated with significantly lower survival at 36 months of age for the entire cohort and for the subgroup with HLHS. At the last follow-up, 67% of the deaths had occurred in babies with an impaired MFE. For all, except 1 death, the impaired MFE was secondary to gestational hypertension/PE or SGA. Future studies are needed focusing on determining the mechanism of an impaired MFE in pregnancies in which the foetus has CHD and on investigation of therapeutic strategies to improve the MFE in these fragile foetuses.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Footnotes

Presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Vienna, Austria, 7–10 October 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cerdeira AS, Karumanchi SA.. Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia and related disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2:a006585.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khankin EV, Royle C, Karumanchi SA.. Placental vasculature in health and disease. Semin Thromb Hemost 2010;36:309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sahni R, Polin RA.. Physiologic underpinnings for clinical problems in moderately preterm and late preterm infants. Clin Perinatol 2013;40:645–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ananth CV, Basso O.. Impact of pregnancy-induced hypertension on stillbirth and neonatal mortality. Epidemiology 2010;21:118–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perez-Cruz M, Cruz-Lemini M, Fernandez MT, Parra JA, Bartrons J, Gomez-Roig MD. et al. Fetal cardiac function in late-onset intrauterine growth restriction vs small-for-gestational age, as defined by estimated fetal weight, cerebroplacental ratio and uterine artery Doppler. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bahtiyar MO, Copel JA.. Cardiac changes in the intrauterine growth-restricted fetus. Semin Perinatol 2008;32:190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sehgal A, Doctor T, Menahem S.. Cardiac function and arterial biophysical properties in small for gestational age infants: postnatal manifestations of fetal programming. J Pediatr 2013;163:1296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sehgal A, Doctor T, Menahem S.. Cardiac function and arterial indices in infants born small for gestational age: analysis by speckle tracking. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:e49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matthiesen NB, Henriksen TB, Agergaard P, Gaynor JW, Bach CC, Hjortdal VE. et al. Congenital heart defects and indices of placental and fetal growth in a Nationwide Study of 924 422 liveborn infants. Circulation 2016;134:1546–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andescavage N, Yarish A, Donofrio M, Bulas D, Evangelou I, Vezina G. et al. 3-D volumetric MRI evaluation of the placenta in fetuses with complex congenital heart disease. Placenta 2015;36:1024–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz A, Ferrer Q, Sanchez O, Ribera I, Arevalo S, Alomar O. et al. Placenta-related complications in women carrying a foetus with congenital heart disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:3271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brodwall K, Leirgul E, Greve G, Vollset SE, Holmstrom H, Tell GS. et al. Possible common aetiology behind maternal preeclampsia and congenital heart defects in the child: a cardiovascular diseases in Norway Project Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2016;30:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laas E, Lelong N, Thieulin AC, Houyel L, Bonnet D, Ancel PY. et al. Preterm birth and congenital heart defects: a population-based study. Pediatrics 2012;130:e829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams RV, Ravishankar C, Zak V, Evans F, Atz AM, Border WL. et al. Birth weight and prematurity in infants with single ventricle physiology: pediatric heart network infant single ventricle trial screened population. Congenit Heart Dis 2010;5:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Costello JM, Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, He X, Hill KD, Cooper DS. et al. Gestational age at birth and outcomes after neonatal cardiac surgery: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Circulation 2014;129:2511–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graf R, Ghanayem NS, Hoffmann R, Dasgupta M, Kessel M, Mitchell ME. et al. Impact of intrauterine growth restriction on cardiac surgical outcomes and resource use. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:1411–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sochet AA, Ayers M, Quezada E, Braley K, Leshko J, Amankwah EK. et al. The importance of small for gestational age in the risk assessment of infants with critical congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young 2013;23:896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Catov JM, Scifres CM, Caritis SN, Bertolet M, Larkin J, Parks WT.. Neonatal outcomes following preterm birth classified according to placental features. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:411 e1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sliwa K, Mebazaa A.. Possible joint pathways of early pre-eclampsia and congenital heart defects via angiogenic imbalance and potential evidence for cardio-placental syndrome. Eur Heart J 2014;35:680–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Llurba E, Sanchez O, Ferrer Q, Nicolaides KH, Ruiz A, Dominguez C. et al. Maternal and foetal angiogenic imbalance in congenital heart defects. Eur Heart J 2014;35:701–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bravo-Valenzuela NJ, Zielinsky P, Huhta JC, Acacio GL, Nicoloso LH, Piccoli A. et al. Dynamics of pulmonary venous flow in fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction. Prenat Diagn 2015;35:249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matthiesen NB, Henriksen TB, Gaynor JW, Agergaard P, Bach CC, Hjortdal VE. et al. Congenital heart defects and indices of fetal cerebral growth in a Nationwide Cohort of 924 422 liveborn infants. Circulation 2016;133:566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cedergren MI, Kallen BA.. Obstetric outcome of 6346 pregnancies with infants affected by congenital heart defects. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;125:211–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saleemuddin A, Tantbirojn P, Sirois K, Crum CP, Boyd TK, Tworoger S. et al. Obstetric and perinatal complications in placentas with fetal thrombotic vasculopathy. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2010;13:459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones HN, Olbrych SK, Smith KL, Cnota JF, Habli M, Ramos-Gonzales O. et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is associated with structural and vascular placental abnormalities and leptin dysregulation. Placenta 2015;36:1078–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Auger N, Fraser WD, Healy-Profitos J, Arbour L.. Association between preeclampsia and congenital heart defects. JAMA 2015;314:1588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malik S, Cleves MA, Zhao W, Correa A, Hobbs CA.. Association between congenital heart defects and small for gestational age. Pediatrics 2007;119:e976–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cnota JF, Gupta R, Michelfelder EC, Ittenbach RF.. Congenital heart disease infant death rates decrease as gestational age advances from 34 to 40 weeks. J Pediatr 2011;159:761–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Costello JM, Polito A, Brown TF, McElrath TF, Graham RR, Thiagarajan EA. et al. Birth before 39 weeks’ gestation is associated with worse outcomes in neonates with heart disease. Pediatrics 2010;126:277–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]