Murder by fake medicine: malaria

Survival is not the case for at least 122,000 African children under 5 y of age who die each year as a result of being treated with fake antimalarial drugs.1 Tens of thousands of others of all ages, with acute malaria and other diseases, are at peril or succumb when the medicines they receive have little or no active pharmaceutical ingredient, contain toxins or are a different compound than indicated on the package.2

To add complexity, resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to artemisinin in Cambodia was first reported in 2008.3 The problem has spread to several countries in the Mekong basin zone. More ominously, a new mutant lineage in the parasite in the same area has outcompeted other mutations, leading to artesunate-piperaquine resistance.4 This is the first evidence of resistance to artemisinin combination treatment—the widely used drug strategy advised by WHO.

At a 2010 meeting at the US National Institutes of Health, called to define a research agenda to deal with the emergence of artemisinin resistance, a presentation was made by a representative from Interpol showing drug raids on facilities making and packaging fake medicines.5 At the same meeting, colleagues from Cambodia and Thailand described the pervasiveness of fake antimalarial drugs in pharmacies in areas near where parasite resistance had been detected.6

A large-scale literature review of the presence of poor quality antimalarials, published in 2012, showed that over 33% of six classes of 3734 antimalarial drug samples tested from South-east Asia and in sub-Saharan Africa were counterfeit, as were over 42% of the artemisinins.7

The pandemic of falsified drugs: far beyond malaria

During the past 15 y, knowledge of an array of falsified drugs has increased greatly among the scientific, public health and lay communities.8,9 Twenty-seven scientific articles mentioning fake drugs were cited on PubMed between 1966 and 2000, 56 between 2000 and 2004, 122 between 2005 and 2009, and 294 between 2009 and 2014.

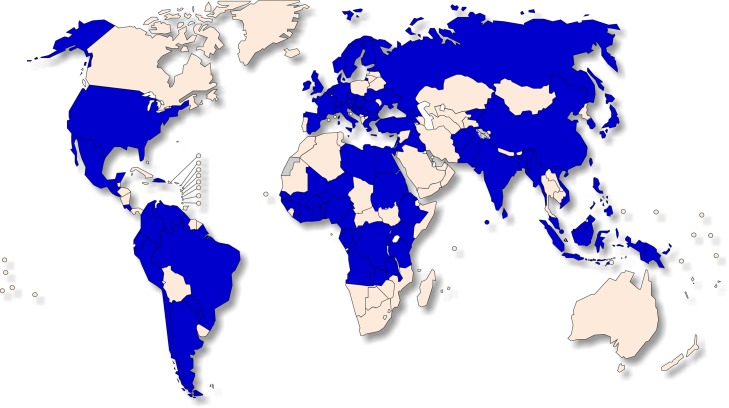

Over 175 countries have now reported poor quality medicines to WHO (Figure 1); the Organization estimates that one in 10 medical products in low-income countries is of poor quality.2 These falsified compounds originate most often from China and India, although many other countries are sites for fabrication and distribution.2,10 The major classes of counterfeit drugs penetrating the legitimate supply chain are anti-infectives, genitourinary (including erectile dysfunction) and cardiovascular.10 Fake vaccines against yellow fever, meningitis and hepatitis B have also been found.

Figure 1.

Countries (blue) in which substandard and falsified medical products have been reported to WHO, 2013–2017.2

Leadership needed

Over the past decade, as the fake drug problem increased, international leadership for protecting the global supply, distribution and use of biologicals was highly fragmented. The International Agency on Drugs and Crime, Interpol and WHO were meeting periodically, but the focus was on intellectual property issues, rather than on public health. For years there was disagreement on terms, with ambiguity and lack of specific actions to stem the rising tide of poor quality products. Very little information was available about methods to define the epidemiology of poor quality compounds, on the various testing systems for assessing drug quality, and on national and international governance and legislation to deal with the problem, especially in low-income countries.8,11

Finally, in 2017, at the Seventieth World Health Assembly, the following definitions were agreed upon after years of meetings and debate:

Falsified medical products: deliberately or fraudulently misrepresenting their identity, composition or source.

Sub-standard medical products: out-of-specification products; these are authorized products by national regulatory authorities, but fail to meet national and/or international quality standards or specifications.

Unregistered or unlicensed medical products: those that have not been assessed or approved by the national or regional regulatory authority for the market in which they are marketed, distributed or used.2

In addition, degraded biological products are those in any of the above categories that have decomposed due to poor storage or handling.

Problem for middle- and high-income countries

The recent importation of the falsified anticancer compound bevacizumab (Avastin®) into the USA and the widely known problem with sildenafil (Viagra®) into higher-income countries indicates no country is free from falsified medicine.12 Japanese citizens rely greatly on the internet to order sildenafil, and over half of those products are falsified.13

It is a hopeful sign that WHO will be taking a more assertive and, possibly, operational role in combating the fake drug pandemic, with the recent publication of the two landmark reports: ‘Global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products’2 and ‘A study on the public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products’.14 The vast array of poor quality drugs being produced and marketed in dozens of poor and rich countries has been reported recently in an excellent WHO Summary study.14

The latter WHO report estimated that of the almost US$300 billion in total pharmaceutical sales in low- and middle-income countries, almost 98% occurs in middle-income countries. US$30.5 billion (10%) of the sales alone are of poor quality products. This estimate does not consider the medical, social and health system costs, which remain to be parsed. A full agenda for action is required if the current dire situation is to be resolved quickly. It is promising that falsified drugs are on the agenda for the 2018 World Health Assembly.

Solutions

Specific actions are needed to stem the tide of poor quality drugs, particularly in low- and middle-income countries—those are at greatest risk. These are:

Designation of a well-financed and supported international leadership organization tasked with developing policies, strategies and specific actions with technical staff that are field-focused. Training of national staff, technology transfer and evidence-based guidelines helping to define local problems, solutions and actions are an immediate priority.

The sustainable development goals should include measurable objectives for good quality drugs, since so many of the objectives rely on medicines to be successful. Each country must aim for at least 90% of all therapeutics and preventives in the country to be of high quality by 2030. This will encourage the establishment of national baseline drug status and achievable targets, particularly for essential drugs. SDG targets will help to solve the poor-quality drug epidemic by application of available technologies and good pharmaceutical vigilance.

Support is needed to accelerate development and comparisons of the most accurate and affordable tools to test for high drug quality at point of sale. Testing technology must be available within the country.

An international convention and strengthened national legislation would facilitate production of high quality drugs, and protect all countries from the criminals and cartels making, distributing and selling life-threatening products. Among many other protections, this would assure prosecution and extradition of criminals, and the smashing of cartels that distribute falsified drugs from one country to another.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services. The use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Financial support: This work was supported by the Fogarty International Center, US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1. Renschler JP, Walters KM, Newton PN et al. Estimated under-five deaths associated with poor-quality antimalarials in sub-Saharan African. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92(6 suppl):119–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. WHO Global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K et al. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med 2008;359(24):2619–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imwong M, Hien TT, Nguyen TT-N et al. Spread of a single multidrug resistant malaria parasite lineage (PfPailin) to Vietnam. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:1022–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dondorp AM, Fairhurst RM, Slutsker L et al. The threat of artemisinin-resistant malaria. N Engl J Med 2011;365(12):1073–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newton PN, Fernandez FM, Plançon A et al. A collaborative epidemiological investigation into the criminal fake astesunate trade in South East Asia. PLoS Med 2008;5: e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Newton PN, Herrington J, Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:488–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herrington JM, Nayyar GML, Breman JG, eds. The global pandemic of falsified medicines: laboratory and field innovations, policies and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg; 2015;92(6 suppl):1–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.The Editorial Board. Stemming the tide of fake medicines. The New York Times 18 May, 2015; A18. http://nyti.ms/1GiM4r6 (accessed 19 June 2018).

- 10. Mackey TK, Liang BA, York P et al. Counterfeit drug penetration into global legitimate medicine supply chains: a global assessment, 2015. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92(6 suppl);1:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Newton PN, Tabernero P, Dwivedi P et al. Falsified medicines in Africa: all talk, no action. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2(9): e509–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mackey TK, Cuomo R, Guerra C et al. After counterfeit Avastin(R) what have we learned and what can be done? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12(5):302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sato D. Counterfeit medicines—Japan and the world. Yakugaku Zasshi (J Pharmaceutical Soc Japan) 2014;134:213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO A study on the public health socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]