Abstract

Background

The treatment of patients with glioma depended on the nature of the lesion and on histological grade of the tumor. Positron emission tomography (PET) using 13N-ammonia (NH3), 11C-methionine (MET) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) have been used to assess brain tumors. Our aim was to compare their diagnostic accuracies in patients with suspected cerebral glioma.

Methods

Ninety patients with suspicion of glioma based on previous CT/MRI, who underwent NH3 PET, MET PET and FDG PET, were prospectively enrolled in the study. The reference standard was established by histology or clinical and radiological follow-up. Images were interpreted by visual evaluation and semi-quantitative analysis using the lesion-to-normal white matter uptake ratio (L/WM ratio).

Results

Finally, 30 high-grade gliomas (HGG), 27 low-grade gliomas (LGG), 10 non-glioma tumors and 23 non-neoplastic lesions (NNL) were diagnosed. On visual evaluation, sensitivity and specificity for differentiating tumors from NNL were 62.7% (42/67) and 95.7% (22/23) for NH3 PET, 94.0% (63/67) and 56.5% (13/23) for MET PET, and 35.8% (24/67) and 65.2% (15/23) for FDG PET. On semi-quantitative analysis, brain tumors showed significantly higher L/WM ratios than NNL both in NH3 and MET PET (both P < 0.001). The sensitivity, specificity and the area under the curve (AUC) by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, respectively, were 64.2, 100% and 0.819 for NH3; and 89.6, 69.6% and 0.840 for MET. Besides, the L/WM ratios of NH3, MET and FDG PET in HGG all significantly higher than that in LGG (all P < 0.001). The predicted (by ROC) accuracy of the tracers (AUC shown in parentheses) were 86.0% (0.896) for NH3, 87.7% (0.928) for MET and 93.0% (0.964) for FDG. While no significant differences in the AUC were seen between them.

Conclusion

NH3 PET has remarkably high specificity for the differentiation of brain tumors from NNL, but low sensitivity for the detection of LGG. MET PET was found to be highly useful for detection of brain tumors. However, like FDG, high MET uptake is frequently observed in some NNL. NH3, MET and FDG PET all appears to be valuable for evaluating the histological grade of gliomas.

Keywords: Glioma, 13N-NH3, 18F-FDG, 11C-MET, PET

Background

Primary malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumors represent approximately 2% of total cancers but account for high patient morbidity and mortality, especially in children and adolescents, which pose specific diagnostic and therapeutic challenges to neurologists [1]. Gliomas are the most common primary brain tumors, representing about 81% of all primary malignant CNS neoplasms [2]. The treatment of patients with brain glioma depended on the nature of the lesion and on the accurate pretherapy tumor grading. Brain lesions have overlapping imaging features on conventional computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which are often difficult to make an accurate diagnosis. The interruption of blood brain barrier (BBB) is easily detected on contrast-enhanced MRI and CT which can provide useful information in the diagnosis of brain tumors, such as glioma, meningiomas and lymphoma. However, tumors with intact BBB like low-grade gliomas (LGG) may mimic non-neoplastic lesions (NNL) in morphological neuroimaging modalities. Besides, morphological evaluation is still difficult to assess accurately the tumor grade and the extent of the tumor invasion [3, 4]. Advanced MRI techniques can gain some valuable biochemical information by detecting the concentration of certain metabolites, but its clinical utility is still limited [5, 6]. Positron emission tomography (PET) is a molecular imaging technique allowing in vivo quantitative measurement of biological processes non-invasively, has become an integral part in the diagnostic workup of patients with brain lesions [7, 8].

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is an 18F-labeled glucose analog and has been used to measure glucose metabolism in vivo. Within this context, FDG PET has been commonly used in tumor detection, prediction of malignancy grade, evaluation of therapeutic response, and discrimination between radiation necrosis and tumor recurrence and between benign and malignant lesions [9–11]. However, FDG PET has limitations in the evaluation of brain tumors, due to the high-glucose metabolism in normal brain parenchyma and nonspecific uptake by NNL. 11C-methionine (MET), reflecting amino acid active transport and protein synthesis, is considerably more sensitive than FDG PET for the detection and delineation of brain tumors [12–14]. However, increased uptake of MET has also been reported in lots of NNL [15–17], prompting efforts to develop new oncological PET tracers. Since 2006, we have reported the clinical usefulness of 13N-ammonia (NH3) PET imaging for brain tumors, especially for gliomas, through a series of studies. The results showed that NH3 was a valuable PET tracer to differentiate gliomas from NNL, and to evaluate the histological grade of gliomas [18–22]. Since clinical application of NH3 PET have been restricted to just a few institutions, little information is available on the clinical utility of NH3 PET in the evaluation of brain tumors as compared with FDG PET and MET PET. The purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate the clinical potential of NH3 PET for the diagnosis of brain tumor and differentiating high-grade gliomas, in comparison with MET PET and FDG PET.

Methods

Patients

Ninety patients with suspicion of cerebral gliomas were prospectively enrolled in the study between September 2010 and December 2017. All patients who were referred for PET had an inconclusive diagnosis on previous conventional imaging (CT/MRI), and PET was performed to determine further diagnostic and therapeutic approach. NH3 PET, FDG PET and MET PET were performed within 1 week of each other. Patients remained untreated until the PET study completed. The reference standard was established by histology or clinical and radiological follow-up for at least one year. Histopathological diagnosis, based on the 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, was obtained by operation or stereotactic brain biopsy. We grouped grade III and IV gliomas together as high-grade gliomas (HGG) and grade II and I together as LGG. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee, and all patients gave their written informed consent before their participation in the study.

Radiotracer synthesis

Tracers were produced at our center by commercially available system for the isotope generation (Ion Beam Applications; Cyclone-10, Belgium). NH3 was synthesized according to our published method [18]. MET was produced by the method of Chung et al. [14] and FDG was synthesized by the method of Toorongian et al. [23]. The radiochemical purity of NH3 and MET were > 99% and FDG was > 95%.

PET imaging protocol

All patients were normoglycemic and had fasted for at least 6 h before FDG PET examination. No special dietary instructions were given to the patients before NH3 PET and MET PET examination. PET/CT imaging was acquired with a Gemini GXL 16 scanner (Philips, Netherlands) in 3-dimensional acquisition mode. A dose of 5.18 MBq (0.14 mCi)/kg FDG was injected intravenously and serial scanning was performed, approximately 30 min after the injection with the patient supine, resting, with their eyes closed. In the PET/CT system, non-contrast CT scan was acquired on the dual-slice spiral CT using a slice thickness of 3 mm, a pitch of 1 and a matrix of 512 × 512 pixels. After the CT scan, static brain PET acquisition was performed for 10 min per bed position for one bed with a matrix of 128 × 128 pixels and a slice thickness of 1.5 mm. For NH3 and MET PET, after intravenous injection of 7.4 MBq (0.20 mCi)/kg of NH3 or MET, patients rested in a quiet room and PET was performed 5 min later. The acquisition parameters were the same as that for FDG PET. Finally, PET images were reconstructed by LOR-RAMLA algorithm with low-dose CT images for attenuation correction.

PET image analysis

PET images were interpreted by two experienced nuclear physicians independently, who were blinded to the clinical and anatomical imaging findings and reached a consensus. The tracer uptake of the lesion was evaluated by both visual evaluation and semi-quantitative analysis.

For visual analysis, the degree of tracer uptake by the lesion was visually classified into 3 grades as follows: reduced uptake (−); normal uptake (+−); increased uptake (+), as compared with tracer uptake by the contralateral or surrounding normal brain parenchyma.

For semi-quantitative analysis, a region of interest (ROI) was placed over the entire lesion on the transverse PET image, and the standardized uptake value (SUV) was calculated. For lesions with reduced or equal tracer uptake, the ROI was drawn based on the anatomical information on the brain lesions presented by MRI/CT. White-matter-ROI (10 mm in diameter) was drawn on the side contralateral to the tumor. L/WM ratio was determined by dividing the lesion (L) maximum SUV by the average SUV of the contralateral White-matter (WM).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses except the ROC analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) software. Categorical data were expressed as numbers and frequency (%). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy of NH3, MET and FDG PET for the detection of brain tumor were calculated. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared using Student’s t-test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was adopted to analyze the efficiency of L/WM ratios in the differential diagnosis among different groups. Further, the MedCalc statistics software was used to test for differences in ROC curve of the different. To determine whether tracer uptake of NH3, FDG and MET were related to each other, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used. For all analysis, P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

Characteristics of all 90 patients are summarized in Table 1. Based on reference standard, 67 patients with brain tumor were all histopathologically confirmed by operation (n = 43) or stereotactic brain biopsy (n = 24). These 67 patients included 27 patients with LGG (4 WHO grade I and 23 WHO grade II), 30 patients with HGG (19 WHO grade III and 11 WHO grade IV), and 10 patients with non-glioma tumors. NNL was diagnosed in 23 patients. Further details of each individual patient with non-glioma tumors and NNL are given in Table 2. Among the 23 patients with NNL, 10 patients were histopathologically confirmed by operation (n = 3) or stereotactic brain biopsy (n = 7). The remaining 13 patients were diagnosed by clinical and radiological follow-up for at least one year (29 ± 5.4 months, range 15–47 months). Of them, 4 patients had demyelination or multiple sclerosis treated with corticosteroids, 6 patients had inflammation accepted anti-inflammatory therapies, 2 patients had infarction mainly accepted anticoagulant therapies, 1 patient had hemorrhage mainly treated with blood pressure management, all their neurological symptoms and MRI findings improved during follow-up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all patients

| All | LGG | HGG | Non-glioma tumors | NNL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 90 | 27 | 30 | 10 | 23 | ||

| Age range (mean ± SD, y) | 3–78 (40.0 ± 14.0) | 3–67 (34.0 ± 13.9) | 14–61 (43.5 ± 12.6) | 21–69 (42.0 ± 15.3) | 22–78 (41.6 ± 14.0) | ||

| Sex (M: F) | 3:2 | 19:8 | 16:14 | 3:7 | 16:7 | ||

| Final diagnose | WHO | Grade I | WHO | Grade III | |||

| PA | 4 | AA | 4 | ||||

| WHO | Grade II | AO | 3 | ||||

| DA | 1 | AE | 1 | ||||

| GA | 1 | Astrocytoma 11 | |||||

| OD | 4 | WHO | Grade IV | ||||

| OA | 1 | GBM | 11 | ||||

| Astrocytoma 16 | |||||||

LGG low-grade glioma, HGG high-grade glioma, NNL non-neoplastic lesions, PA pilocytic astrocytoma, DA diffuse astrocytoma, GA gemistocytic astrocytoma, OD oligodendroglioma, OA oligoastrocytoma, AA anaplastic astrocytoma, AO anaplastic oligodendroglioma, AE anaplastic ependymoma, GBM glioblastoma

Table 2.

Details of patient characteristics, results of each PET imaging, and reference criteria for the final diagnosis in patients with non-glioma tumors and non-neoplastic lesions

| Pt. No. | Age range (y) | Locationa | FDG | NH3 | MET | Method of diagnosis | Final diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | L/WMb | Visual | L/WM | Visual | L/WM | |||||

| Non-glioma tumors | ||||||||||

| 1 | 50–55 | Cerebellum | (+) | 2.24 | (+) | 1.72 | (+) | 2.89 | Operation | Metastatic adenocarcinoma |

| 2 | 20–25 | L. basal ganglia region | (−) | 1.32 | (+) | 2.67 | (+) | 3.24 | Biopsy | Germinoma |

| 3 | 35–40 | R. cavernous sinus area | (+) | 2.38 | (+) | 2.30 | (+) | 3.35 | Operation | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 4 | 40–45 | Suprasellar | (−) | 1.07 | (+) | 2.42 | (+) | 2.28 | Operation | Craniopharyngioma |

| 5 | 65–70 | R. parietal | (−) | 1.37 | (+) | 3.75 | (+) | 2.72 | Operation | Meningioma |

| 6 | 60–65 | Cerebellum | (−) | 1.28 | (+) | 3.66 | (+) | 2.78 | Operation | Hemangioblastoma |

| 7 | 25–30 | Cerebellum | (+) | 2.61 | (+) | 2.00 | (+) | 2.00 | Operation | Medulloblastoma |

| 8 | 25–30 | Cerebellum | (+) | 2.32 | (+) | 2.40 | (+) | 2.24 | Operation | Medulloblastoma |

| 9 | 45–50 | L. frontal | (+) | 4.02 | (+) | 3.09 | (+) | 3.00 | Operation | Metastatic tumor |

| 10 | 30–35 | R. frontal | (−) | 1.22 | (−) | 1.60 | (+−) | 1.51 | Operation | DNT |

| Non-neoplastic lesions | ||||||||||

| 11 | 20–25 | L. frontal | (+) | 2.75 | (+−) | 1.68 | (+−) | 1.58 | Follow-up | Inflammation |

| 12 | 40–45 | L. frontal-parietal | (−) | 1.76 | (−) | 1.10 | (−) | 1.00 | Biopsy | Demyelination |

| 13 | 30–35 | R. parietal | (+−) | 2.10 | (+−) | 1.64 | (+) | 2.27 | Follow-up | Demyelination |

| 14 | 25–30 | R. basal ganglia region | (+−) | 2.12 | (+−) | 1.72 | (+−) | 1.50 | Biopsy | Demyelination |

| 15 | 70–75 | Cervical spinal | (+) | 2.88 | (+−) | 1.70 | (+−) | 1.78 | Follow-up | Inflammation |

| 16 | 20–25 | R. cerebellopontine angle | (−) | 1.32 | (+−) | 1.63 | (+−) | 1.55 | Follow-up | Demyelination |

| 17 | 25–30 | R. thalamus | (−) | 1.80 | (+−) | 1.75 | (+−) | 1.77 | Follow-up | Inflammation |

| 18 | 40–45 | R. parietal | (+) | 2.23 | (+−) | 1.72 | (+) | 2.49 | Biopsy | Inflammation |

| 19 | 35–40 | R. cerebellum | (+) | 2.80 | (−) | 1.45 | (−) | 1.38 | Follow-up | Inflammation |

| 20 | 40–45 | Brain stem, R. temporal | (−) | 1.58 | (−) | 1.55 | (+−) | 1.54 | Follow-up | Inflammation |

| 21 | 40–45 | L. pons | (−) | 1.56 | (−) | 1.29 | (−) | 1.31 | Follow-up | Infarction |

| 22 | 50–55 | L. temporal | (+) | 2.49 | (−) | 0.94 | (+) | 2.67 | Operation | Brain abscess |

| 23 | 45–50 | L. parietal | (+) | 3.28 | (−) | 1.63 | (+) | 2.88 | Operation | Brain abscess |

| 24 | 40–45 | R. frontal | (+) | 3.80 | (−) | 1.58 | (+) | 3.04 | Operation | Brain abscess |

| 25 | 20–25 | L. parietal | (−) | 1.10 | (−) | 1.18 | (−) | 1.32 | Biopsy | Demyelination |

| 26 | 30–35 | L. basal ganglia region | (−) | 1.44 | (−) | 1.45 | (−) | 1.40 | Follow-up | Multiple sclerosis |

| 27 | 40–45 | R. cerebellum | (−) | 1.98 | (+−) | 1.79 | (+) | 2.60 | Follow-up | Infarction |

| 28 | 50–55 | L. frontal | (+−) | 2.10 | (+−) | 1.75 | (+) | 1.95 | Biopsy | Inflammation |

| 29 | 78–80 | R. parietal | (−) | 1.06 | (−) | 1.14 | (+) | 1.86 | Follow-up | Hemorrhage |

| 30 | 40–45 | L. frontal and parietal | (+) | 2.70 | (+) | 1.87 | (+) | 3.15 | Biopsy | Inflammation |

| 31 | 40–45 | Pons | (−) | 1.68 | (−) | 1.54 | (−) | 1.38 | Follow-up | Brain abscess |

| 32 | 50–55 | R. basal ganglia region | (−) | 1.58 | (−) | 1.02 | (+) | 1.81 | Follow-up | Infarction |

| 33 | 25–30 | L. thalamus | (−) | 1.52 | (−) | 1.44 | (−) | 1.15 | Biopsy | Demyelination |

a R right, L left, b L/WM Lesion-to-white matte ratio, DNT dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor

Visual analysis

Of the 67 patients with brain tumor, NH3 uptake was a visual grading of (+) in 42 patients (27 HGG, 6 LGG and 9 non-glioma tumor). Of the remaining 25 patients, 13 patients were (+−) and 12 patients were (−). It was interesting to note that, of the 23 patients with NNL, NH3 uptake was (+) only in one patient with inflammatory lesion, Fig. 1. Of the remaining 22 patients, 9 patients were (+−) and 13 patients were (−), Hence, NH3 was positive (+) in 43 patients (42 true positive and 1 false positive) and negative (+ − and -) in 47 patients (22 true negative and 25 false negative), detailed in Table 3. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for the detection of brain tumor, using the visual grading criterion of (+), were 62.7, 95.7, 97.7, 46.8, and 71.1%, respectively.

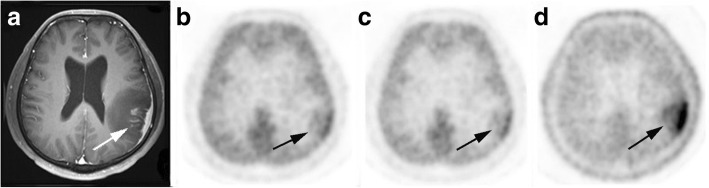

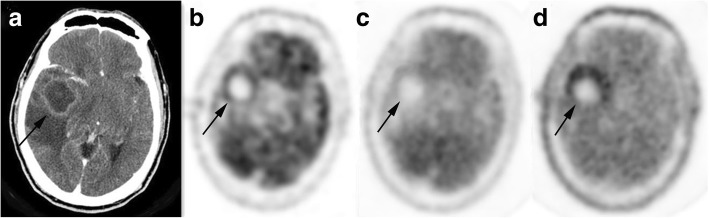

Fig. 1.

A patient aged 40–45 years with cerebral inflammatory lesion. Contrast enhanced MRI (a) shows the left frontal parietal lobe and adjacent meningeal lesion (arrow) was obvious heterogeneous enhanced. Significant higher uptake of 11C-MET (d) and mild increased uptake of 18F-FDG (b) and 13N-NH3 (c) were observed

Table 3.

13N-NH3, 11C-MET and 18F-FDG uptake positive in all lesion groups and mean L/WM ratios in neoplastic lesions, LGG, HGG and NNL

| Group | No. of Patients | Positive, n | L/WM (mean ± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3 | MET | FDG | NH3 | MET | FDG | ||

| Neoplastic lesions | 67 | 42 | 63 | 24 | 2.25 ± 0.69 | 2.96 ± 0.95 | 2.00 ± 0.86 |

| LGG | 27 | 6 | 24 | 1 | 1.76 ± 0.51 | 2.34 ± 0.56 | 1.36 ± 0.35 |

| HGG | 30 | 27 | 30 | 18 | 2.59 ± 0.54 | 3.64 ± 0.90 | 2.59 ± 0.75 |

| Non-glioma tumors | 10 | 9 | 9 | 5 | |||

| NNL | 23 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 1.50 ± 0.27 | 1.88 ± 0.63 | 2.07 ± 0.71 |

LGG low-grade glioma, HGG high-grade glioma, NNL non-neoplastic lesions, L/WM Lesion-to-white matter ratio

Of the 67 patients with brain tumor, MET uptake was a visual grading of (+) in 63 patients (all HGG, 24 LGG and 9 non-glioma tumor), and the remaining 4 patients were (+−). Of the 23 patients with NNL, MET uptake was (+) in 10 patients, and 6 patients were (+−) and 7 patients were (−). Hence, MET was positive in 73 patients (63 true positive and 10 false positive) and negative in 17 patients (13 true negative and 4 false negative). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for the detection of brain tumor, using the visual grading criterion of (+), were 94.0, 56.5, 86.3, 76.5, and 84.4%, respectively.

Of the 67 patients with brain tumor, FDG uptake was a visual grading of (+) in 24 patients (18 HGG, 1 LGG and 5 non-glioma tumor), and 5 patients were (+−) and 38 patients were (−). Among 23 patients with NNL, FDG uptake was (+) in 8 patients (all inflammatory or abscess lesion), and 3 patients were (+−) and 12 patients were (−). Hence, FDG was positive in 32 patients (24 true positive and 8 false positive) and negative in 58 patients (15 true negative and 43 false negative). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for the detection of brain tumor, using the visual grading criterion of (+), were 35.8, 65.2, 75.0, 25.9, and 43.3%, respectively. Representative cases were shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

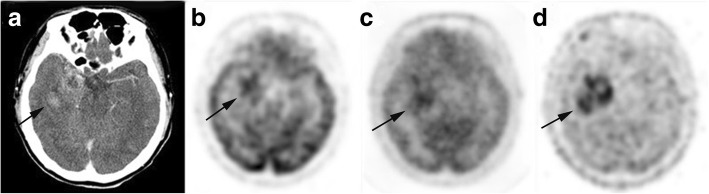

Fig. 2.

A patient aged 40–45 years with glioblastoma. Contrast enhanced CT (a) shows a moderately enhanced lesion in the right temporal lobe (arrow). 18F-FDG (b), 13N-NH3 (c) and 11C-MET (d) were all positive for the lesion, and the tracer accumulation of 11C-MET was higher than that of 13N-NH3 and 18F-FDG

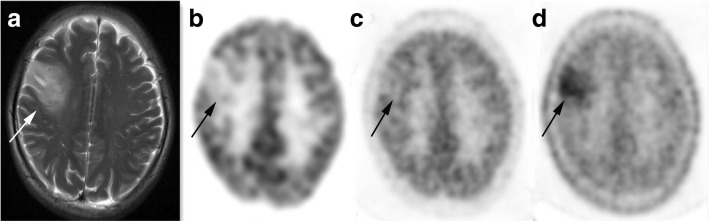

Fig. 3.

A patient aged 30–35 years with grade II glioma. T2-weighted MRI (a) shows a high signal lesion in the right frontal lobe (arrow). Higher uptake of 11C-MET (d), nearly equal uptake of 13N-NH3 (c) and apparently reduced uptake of 18F-FDG (b) were observed

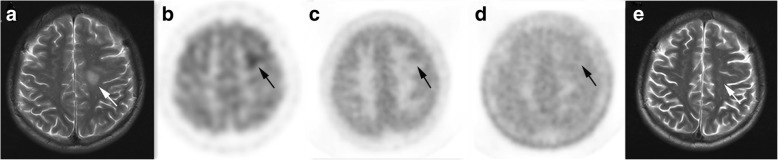

Fig. 4.

A patient aged 20–25 years with cerebral inflammatory lesion. T2-weighted MRI (a) shows a high signal lesion within the left frontal white matter (arrow). The lesion exhibits increased uptake of 18F-FDG (b) with equal uptake of 13N-NH3 (c) and 11C-MET (d) compared with contralateral normal brain parenchyma. Repeated MRI (e) shows that the lesion disappeared

Fig. 5.

A patient aged 50–55 years with brain abscess. The lesion displays obviously increased uptake of 11C-MET (d) and mild increased uptake of 18F-FDG (b) with lower uptake of 13N-NH3 (c) compared with contralateral normal brain parenchyma. Contrast CT (a) shows a ring enhanced lesion in the right temporal lobe (arrow)

Semi-quantitative analysis

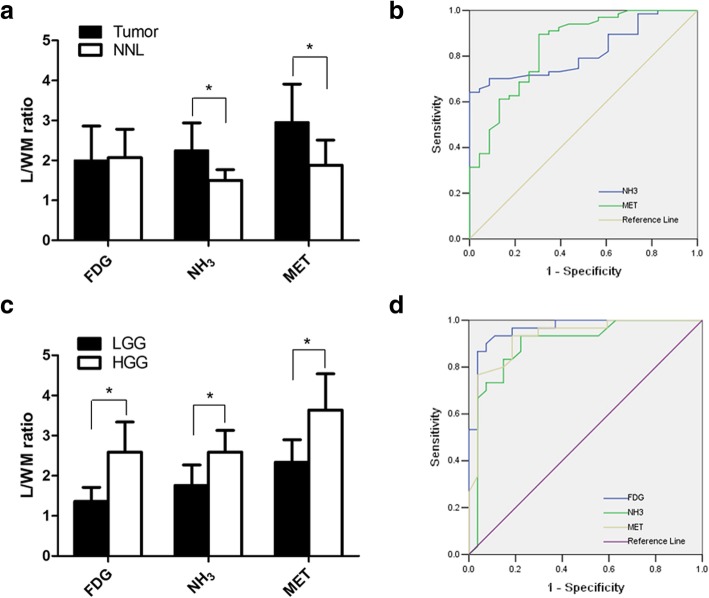

Of the 90 patients (67 had brain tumors and 23 had NNL), the mean L/WM ratios of NH3 and MET PET in brain tumors were both significantly higher than that in NNL (2.25 ± 0.69 vs 1.50 ± 0.27, P < 0.001; 2.96 ± 0.95 vs 1.88 ± 0.63, P < 0.001), but not for FDG (2.00 ± 0.86 vs. 2.07 ± 0.71, respectively; P = 0.733) shown in (Table 3). ROC analysis for differentiation between brain tumors and NNL yielded an optimal L/WM ratio of 1.92 for NH3 (sensitivity, 64.2%; specificity, 100%; PPV, 100.0%; NPV, 48.9%; accuracy, 73.3%; AUC, 0.819; CI [0.734–0.904]), 1.97 for MET (sensitivity, 89.6%; specificity, 69.6%; PPV, 89.6%; NPV, 69.6%; accuracy, 84.4%; AUC, 0.840, CI [0.743–0.937]).

Of the 57 patients with gliomas (27 had LGG and 30 had HGG), the L/WM ratios of NH3, MET and FDG PET in HGG were all significantly higher than that in LGG (2.59 ± 0.54 vs 1.76 ± 0.51, respectively, P < 0.001; 3.64 ± 0.90 vs 2.34 ± 0.56, respectively, P < 0.001; 2.59 ± 0.75 vs 1.36 ± 0.35, respectively, P < 0.001). (Table 3, Fig. 6a). ROC analysis for differentiation between HGG and LGG yielded an optimal L/WM ratio of 2.01 for NH3 (sensitivity, 93.3%; specificity, 77.8%; PPV, 82.4%; NPV, 91.3%; accuracy, 86.0%; AUC, 0.896; CI [0.807–0.986]), 2.74 for MET (sensitivity, 93.3%; specificity, 81.5%; PPV, 84.8%; NPV, 91.7%; accuracy, 87.7%; AUC, 0.928; CI [0.861–0.996]), and 1.65 for FDG (sensitivity, 93.3%; specificity, 92.6%; PPV, 93.3%; NPV, 92.6%; accuracy, 93.0%; AUC, 0.964; CI [0.920–1.000]), respectively. The greatest AUC was obtained for FDG uptake of the parameter L/WM ratio, but no significant differences were found. ROC curves of the three tracers were displayed in Fig. 6b.

Fig. 6.

Graph (a) showing tracer uptake ratios in tumors and NNL. *P < 0.001. b ROC curve analysis of L/WM ratio to differentiate between tumors and NNL (NH3: AUC, 0.819; optimal cutoff, 1.92; MET: AUC, 0.840; optimal cutoff, 1.97). Graph (c) showing the correlation between tracer uptake and glioma grade. *P < 0.001. d ROC curve analysis of L/WM ratio to differentiate between HGG and LGG. Area under curve (AUC) was 0.964 for FDG (optimal cutoff, 1.65), 0.896 for NH3 (optimal cutoff, 2.01) and 0.928 for MET (optimal cutoff, 2.74)

Correlation among three tracer accumulations

Significant correlation was observed among NH3, MET and FDG uptake in gliomas (FDG/NH3: r = 0.726, FDG/MET: r = 0.762, NH3/MET: r = 0.776, all P < 0.001).

Discussion

The major finding of our study is that NH3 PET could differentiate brain tumors from NNL with high specificity, compared with MET and FDG PET. It is interesting to note that only one of the 23 patients with NNL showed slightly high NH3 uptake. This finding suggested that NH3 had the potential to enable differentiation between neoplastic lesions and NNL, which was in good agreement with those reported in our previous studies [20]. However, in present study, NH3 PET detected only 62.7% (42/67) patients with brain tumor, and 77.8% (21/27) of patients with LGG, and 95.7% (22/23) of patients with NNL showed negative results in NH3 PET. This indicates that it is difficult to distinguish LGG from NNL using NH3 PET.

In the detection and delineation of glioma, MET has advantages over FDG, mainly due to its lower uptake in the normal brain tissue. In present study, for the detection of brain tumor, the overall ability of MET is better than NH3 and FDG, with a detection sensitivity of 94.0% versus 62.7% using NH3, and 35.8% using FDG. Given these results, MET PET appears to be superior to NH3 PET and FDG PET for detection of tumor lesions. However, increased uptake of these amino acid tracers is not specific as it has been observed in many NNL, including intracranial hemorrhages, cerebral infarctions, multiple sclerosis and brain abscess [16, 24–27]. In this study, MET PET revealed low specificity for brain tumors, as 10 of 23 NNL (6 patients with inflammatory and abscess lesions, 1 demyelination, 2 infarctions and 1 hemorrhage) showed MET uptake positive. Our results differ from Chung et al. report in benign brain lesions, probably because most of the benign lesions in our study were inflammatory lesions, but none or a small part in theirs study [14]. Mechanism of MET uptake in inflammatory lesions is not clear. One study showed that disruption of the BBB and increased density of inflammatory cells could account for this phenomenon [16].

According to the histological grade, in this present study when grade III and IV gliomas were grouped together as HGG and grade II and I together as LGG, NH3, MET and FDG uptake were all significantly higher in HGG (n = 30) than that in LGG (n = 27). These facts suggest that NH3, FDG and MET all have the potential to reflect degree of glioma differentiation. Some previous studies have also shown that the glucose utilization rate have a positive correlation with the malignancy grade of glioma [9, 10]. However, high FDG uptake has been also observed in NNL. These findings indicate that FDG PET may be not considered useful for differentiation between HGG and NNL. Although NH3 and MET PET seems to be valuable for evaluating the histological grade, the relationship between the tumor uptake of amino acid and histological grade remains controversial. Our findings are different from previous several studies [28–31]. In these studies, MET uptake seems to have no or less value for evaluating glioma malignancy grades. Ogawa et al. reported that there was a wide overlap of MET uptake between LGG and HGG despite statistically significant difference between them [32], thus they indicated that MET PET has greater value in assessing the extent rather than the histological grade of glioma. However, our results are consistent with a study by Singhal et al. who reported there was a significant higher uptake of MET in HGG than in LGG [33]. One of the reasons for the difference of these three radiopharmaceuticals uptake in gliomas may be the different mechanisms of accumulation in the tumor cells. The other interesting observation in our study is that the mean L/WM ratios for NH3, MET, and FDG PET have a statistically significant relationship to each other in cerebral gliomas. To our knowledge, this study is the largest series of head to head comparison among NH3, FDG and MET PET in patient with brain lesions.

Conclusion

NH3 PET has remarkably high specificity for the differentiation of brain tumors from NNL, but low sensitivity for the detection of LGG. MET was found to be highly useful for detection of brain tumors. However, we should keep in mind that like FDG, high MET uptake is frequently observed in some NNL. NH3, MET and FDG PET all appears to be valuable for evaluating the histological grade of gliomas.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Drug Synthesis Department for the preparation of PET tracers, and all nuclear technologists for image collecting and processing in PET/CT center.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Projects of Guangdong Province (No: 2017B020210001 to XSZ and 2016B030307003 to Yao Lu) and the Training Program of the Major Research Plan of Sun Yat-Sen University (No:17ykjc10) to XSZ. Funding supporter played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article. Data and materials during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- CI

95% Confidence interval

- CT

Computed tomography

- FDG

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

- HGG

High-grade gliomas

- LGG

Low-grade gliomas

- MET

11C-methionine

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NH3

13N-ammonia

- NNL

Non-neoplastic lesions

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- ROI

Region of interest

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

Authors’ contributions

QH and LQZ participated in the design of the study, collected the patients’ data, and drafted the manuscript. BZ, XCS and CY processed the figures, helped draft the manuscript, and performed a critical revision of the manuscript. XSZ conceived and designed the study and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, and the need for signed informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Qiao He, Email: heqiao0925@126.com.

Linqi Zhang, Email: zhanglinqi0909@163.com.

Bing Zhang, Email: lihecihange@163.com.

Xinchong Shi, Email: xinchong1985@sina.com.

Chang Yi, Email: ares4310@126.com.

Xiangsong Zhang, Phone: 0086-13711471890, Email: xiangsong_zhang@126.com.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M, Blanda R, Kromer C, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17(Suppl 4):iv1–iv62. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Direksunthorn T, Chawalparit O, Sangruchi T, Witthiwej T, Tritrakarn SO, Piyapittayanan S, Charnchaowanish P, Pornpunyawut P, Sathornsumetee S. Diagnostic performance of perfusion MRI in differentiating low-grade and high-grade gliomas: advanced MRI in glioma, a Siriraj project. J Med Assoc Thail. 2013;96(9):1183–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filss CP, Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Sabel M, Wittsack HJ, Turowski B, Antoch G, Zhang K, Fink GR, Coenen HH, et al. Comparison of 18F-FET PET and perfusion-weighted MR imaging: a PET/MR imaging hybrid study in patients with brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(4):540–545. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.129007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magalhaes A, Godfrey W, Shen Y, Hu J, Smith W. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of brain tumors correlated with pathology. Acad Radiol. 2005;12(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahin N, Melhem ER, Wang S, Krejza J, Poptani H, Chawla S, Verma G. Advanced MR imaging techniques in the evaluation of nonenhancing gliomas: perfusion-weighted imaging compared with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and tumor grade. Neuroradiol J. 2013;26(5):531–541. doi: 10.1177/197140091302600506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaller B. Usefulness of positron emission tomography in diagnosis and treatment follow-up of brain tumors. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(3):437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhal T. Positron emission tomography applications in clinical neurology. Semin Neurol. 2012;32(4):421–431. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D, Kim S, Kim SH, Chang JH, Yun M. Prediction of overall survival based on Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation and 18F-FDG uptake on PET/CT in patients with cerebral gliomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43(5):311–316. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song PJ, Lu QY, Li MY, Li X, Shen F. Comparison of effects of 18F-FDG PET-CT and MRI in identifying and grading gliomas. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2016;30(3):833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyake K, Shinomiya A, Okada M, Hatakeyama T, Kawai N, Tamiya T. Usefulness of FDG, MET and FLT-PET studies for the management of human gliomas. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:205818. doi: 10.1155/2012/205818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasaki M, Kuwabara Y, Yoshida T, Nakagawa M, Fukumura T, Mihara F, Morioka T, Fukui M, Masuda K. A comparative study of thallium-201 SPET, carbon-11 methionine PET and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET for the differentiation of astrocytic tumours. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25(9):1261–1269. doi: 10.1007/s002590050294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato T, Shinoda J, Nakayama N, Miwa K, Okumura A, Yano H, Yoshimura S, Maruyama T, Muragaki Y, Iwama T. Metabolic assessment of gliomas using 11C-methionine, [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose, and 11C-choline positron-emission tomography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(6):1176–1182. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung JK, Kim YK, Kim SK, Lee YJ, Paek S, Yeo JS, Jeong JM, Lee DS, Jung HW, Lee MC. Usefulness of 11C-methionine PET in the evaluation of brain lesions that are hypo- or isometabolic on 18F-FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29(2):176–182. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Matsuda H, Kubota K. Imaging Spectrum and pitfalls of (11)C-methionine positron emission tomography in a series of patients with intracranial lesions. Korean J Radiol. 2016;17(3):424–434. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2016.17.3.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawai N, Okauchi M, Miyake K, Sasakawa Y, Yamamoto Y, Nishiyama Y, Tamiya T. 11C-methionine positron emission tomography in nontumorous brain lesions. No Shinkei Geka. 2010;38(11):985–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakajima R, Kimura K, Abe K, Sakai S. (11)C-methionine PET/CT findings in benign brain disease. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35(6):279–288. doi: 10.1007/s11604-017-0638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiangsong ZWC, Dianchao Y, et al. Usefulness of (13)N-NH (3) PET in the evaluation of brain lesions that are hypometabolic on (18)F-FDG PET. J Neuro-Oncol. 2011;105:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi X, Liu Y, Zhang X, Yi C, Wang X, Chen Z, Zhang B. The comparison of 13N-ammonia and 18F-FDG in the evaluation of untreated gliomas. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(7):522–526. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318295298d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi X, Yi C, Wang X, Zhang B, Chen Z, Tang G, Zhang X. 13N-ammonia combined with 18F-FDG could discriminate between necrotic high-grade gliomas and brain abscess. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40(3):195–199. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiangsong Z, Changhong L, Weian C, Dong Z. PET imaging of cerebral astrocytoma with 13N-ammonia. J Neuro-Oncol. 2006;78(2):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-9069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiangsong Z, Weian C. Differentiation of recurrent astrocytoma from radiation necrosis: a pilot study with 13N-NH3 PET. J Neuro-Oncol. 2007;82(3):305–311. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toorongian SA, Mulholland GK, Jewett DM, Bachelor MA, Kilbourn MR. Routine production of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose by direct nucleophilic exchange on a quaternary 4-aminopyridinium resin. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1990;17(3):273–279. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(90)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Souza MMSR, Jaimini A, et al. Metabolic assessment of intracranial tuberculomas using 11C-methionine and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Nucl Med Commun. 2012;33:408–414. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32834f9b14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs A. Amino acid uptake in ischemically compromised brain tissue. Stroke. 1995;26(10):1859–1866. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.26.10.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirai S, Yabe I, Kano T, Shimizu Y, Sasamori T, Sato K, Hirotani M, Nonaka T, Takahashi I, Matsushima M, et al. Usefulness of 11C-methionine-positron emission tomography for the diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2014;261(12):2314–2318. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7500-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutterer MNM, Putzer D, et al. [18F]-fluoro-ethyl-L-tyrosine PET: a valuable diagnostic tool in neuro-oncology, but not all that glitters is glioma. Neuro-Oncology. 2013;15(3):341–351. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becherer A, Karanikas G, Szabo M, Zettinig G, Asenbaum S, Marosi C, Henk C, Wunderbaldinger P, Czech T, Wadsak W, et al. Brain tumour imaging with PET: a comparison between [18F]fluorodopa and [11C]methionine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(11):1561–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ceyssens S, Van Laere K, de Groot T, Goffin J, Bormans G, Mortelmans L. [11C]methionine PET, histopathology, and survival in primary brain tumors and recurrence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(7):1432–1437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moulin-Romsee G, D'Hondt E, de Groot T, Goffin J, Sciot R, Mortelmans L, Menten J, Bormans G, Van Laere K. Non-invasive grading of brain tumours using dynamic amino acid PET imaging: does it work for 11C-methionine? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(12):2082–2087. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0557-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li DL, Xu YK, Wang QS, Wu HB, Li HS. (1)(1)C-methionine and (1)(8)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT in the evaluation of patients with suspected primary and residual/recurrent gliomas. Chin Med J. 2012;125(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa T, Shishido F, Kanno I, Inugami A, Fujita H, Murakami M, Shimosegawa E, Ito H, Hatazawa J, Okudera T, et al. Cerebral glioma: evaluation with methionine PET. Radiology. 1993;186(1):45–53. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.1.8380108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singhal T, Narayanan TK, Jacobs MP, Bal C, Mantil JC. 11C-methionine PET for grading and prognostication in gliomas: a comparison study with 18F-FDG PET and contrast enhancement on MRI. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(11):1709–1715. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.102533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article. Data and materials during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.