Abstract

Budd–Chiari syndrome is characterized by hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction. We describe an 18-year-old female of known celiac disease presented with progressive abdomen distention and shortness of breath for the last 1 month. Computed tomography of abdomen revealed hepatic vein obstruction. The patient was diagnosed with Budd–Chiari syndrome. Coagulation profile showed an increased homocysteine level. Serum folate level was also decreased. The patient was put on oral anticoagulant with a gluten-free diet. After 4 weeks, the patient showed significant improvement with decreased ascites. The association of Budd–Chiari syndrome with Celiac disease has not yet been fully understood. There have been few reports that described this rare association. Budd–Chiari syndrome should be considered as an important differential in a patient with unexplained ascites and celiac disease.

Keywords: Budd–Chiari syndrome, celiac disease, ascites, hypercoagulable state

Introduction

Budd–Chiari syndrome (BCS) is caused by thrombotic or non-thrombotic obstruction of hepatic veins. Hepatomegaly, ascites, and abdominal pain are the important features of BCS. BCS is extremely rare. According to a recent meta-analysis, the annual incidence of BCS is 0.168–4.09 per million. Moreover, in Asian countries, the reported annual incidence is much less (subgroup meta-analyses showed that the pooled annual incidence of BCS was 0.469 per million in Asia and 2 per million in Europe).1 More than 80% of the patients with BCS are having an underlying hypercoagulable state. Myeloproliferative disorders are the most common cause of hepatic vein obstruction in BCS. We here report a patient of celiac disease (CD) with Budd–Chiari syndrome. In CD, isolated hypertransaminasemia and autoimmune liver disease (primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis) may present. However, BCS is rarely reported in the literature. Some cases have been reported from North Africa and Southern Europe. To our best knowledge, only one case is reported from India previously.2 Herein, we highlight the rare association of the CD with BCS.

Case presentation

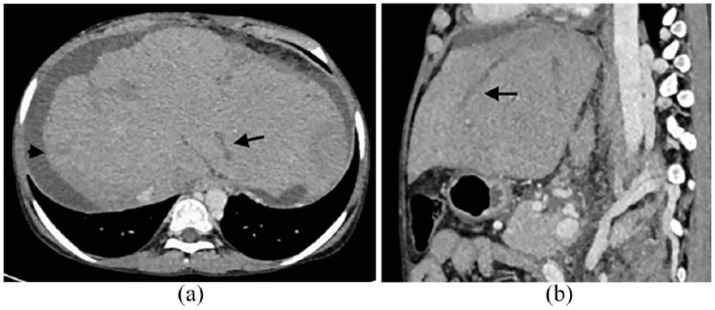

An 18-year-old female of known CD presented to our hospital with chief complaints of abdominal distension, pedal edema, and progressive shortness of breath for the last 1 month. She was adherent to a gluten-free diet until 2 years back. There is no other significant illness in the past. General physical examination showed pallor, mild icterus with bilateral pedal edema. Further examination revealed moderate ascites with a palpable spleen (4 cm below left costal margin). Liver was also palpable 3 cm below right costal margin. Biochemical and hematological investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL, total leukocyte count of 3.02 × 109/L, mean corpuscular volume of 78 fL, and a platelet count of 48 × 109/L. Peripheral blood film showed microcytic hypochromic red blood cells (RBCs). Serum iron and ferritin levels were 21 and 94 µg/dL (normal 40–155 mg/dL and 11–307 µg/dL). Liver function test showed total bilirubin of 3.24 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase 98 U/L (normal: 0–30 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase 73 U/L (normal: 0–35 U/L), and albumin 2.7 g/dL. Ascitic fluid examination revealed total protein 1.4 g/dL, glucose 98 mg/dL, albumin 1 g/dL, and serum-ascitic albumin gradient of 1.7, which was suggestive of portal hypertension. Serum anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies were increased (400 IU/mL, normal <50 IU/mL). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed scalloping of the second part of the duodenum. The duodenal biopsy showed increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, villous atrophy, and crypt hyperplasia. The international normalized ratio (INR) and prothrombin time (PT) were increased to 1.4 and 16.4. Viral markers were negative (HBsAg, anti-HCV). Further analysis revealed normal serum ceruloplasmin level. Slit-lamp microscopy examination was also negative for Kayser–Fleischer ring. Autoimmune markers for liver disease were negative. A Doppler ultrasonography showed caudate lobe hypertrophy with filling defects in all three hepatic veins. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed non-visualization of hepatic veins in hepatic venous phase with caudate lobe hypertrophy with irregular and nodular margins predominantly on the right lobe of the liver, which confirms the diagnosis of BCS (Figure 1(a) and (b)).

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT image (axial and sagittal a, b) obtained during hepatic venous phase shows thrombosis in branches of hepatic vein in left lobe (black arrow), ascites (arrowhead), and non-visualization of hepatic veins in right lobe, suggestive of Budd–Chiari syndrome.

Screening for the hypercoagulable state showed an increased homocysteine level (38 µmol/L, normal: 1.0–15.0). Rest coagulation profile was negative (lupus anticoagulant, protein C and protein S, factor V Leiden mutation, antithrombin III). Serum folate levels were also decreased (2.3 ng/mL, normal: 5–21 ng/mL). Vitamin B-12 levels were normal (345 pg/mL, normal: 211–900 pg/mL). Bone marrow examination was done to rule out myeloproliferative disorders, which was unremarkable. The JAK2 mutation was also absent.

The patient was treated conservatively with oral anticoagulant and diuretics (spironolactone with furosemide). She also started on gluten-free diet, vitamin B-12, folic acid, and iron supplement. 1 month later, the patient had symptomatic improvement with a decrease in ascites. Her hemoglobin was also increased (10 g/dL) with an increase in platelet counts. Her liver functions were also improved (total bilirubin 1.5 g/dL, albumin 3.2 g/dL).

Discussion

CD can present with a series of extraintestinal manifestations like type 1 diabetes mellitus, dermatitis herpetiformis, and autoimmune thyroiditis. Mild non-specific chronic elevated serum aminotransferase is common in CD. However, severe liver disease may present in the form of primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or congenital liver fibrosis. Our patient was a known case of CD for the last 6 years, presented with subacute BCS.

The occurrence of BCS in CD is rare. The first report of CD in BCS was described in 1990.3 Most of the cases described in the literature were from North Africa, middle east, and southern Europe.4–7 Review of the literature showed only two cases reported from another part of the world (India and Argentina).2,8 Our case is the second to be reported from India. Among the previously reported cases, most of the patients presented in their third or fourth decade. The clinical presentation varied among fulminant, acute, subacute, and chronic, with chronic BCS was the commonest presentation. According to a recent study, 61% of the patients of BCS reported with CD, no underlying thrombotic etiology was found.6 However, serum homocysteine levels were elevated in our patient, which might have triggered the development of BCS.

Primary myeloproliferative disorders are the leading cause of BCS. However, 25% of patients may have more than one etiological factor responsible for the hypercoagulable state in BCS. The occurrence of CD with BCS is still not fully elucidated. According to earlier proposed theories, ethnic and environmental factors were responsible for this association because of all cases reported from the same geographical areas. The hypercoagulable state in CD is explained by various theories. Hyposplenism in CD may be responsible for thrombosis. Autoimmune vasculitis, the presence of lymphoma, and malabsorption of vitamin K causing protein C, S, and antithrombin III deficiency are other mechanisms suggested in some reports.9 According to one report, hyperhomocysteinemia secondary to folate deficiency or MTHFR (methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase) gene mutation may lead to thrombosis in BCS.10 Similar to that report, our patient had hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased folate level. In our patient, we could not find other factors responsible for thrombosis like a myeloproliferative disease, protein C, S deficiency, and factor V Leiden. Folate deficiency is common in CD. According to one study, the prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in CD is 20%, with higher homocysteine level seen in severe duodenal involvement.11 A gluten-free diet also has a positive effect in decreasing homocysteine level according to their report. Due to financial constraint, we could not investigate for MTHFR gene mutation in our patient. Since all other possible prothrombotic factors were absent, hyperhomocysteinemia could be an important trigger for the development of BCS in our patient.

To conclude, we present a rare association of BCS and CD. Further studies are required to know the natural history of BCS in CD, the effect of the gluten-free diet on the clinical course of liver disease, and long-term prognosis. Every physician should explore the possibility of Budd-Chiari Syndrome while evaluating a patient of Celiac Disease with unexplained liver disease.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Durga Shankar Meena  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9524-5278

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9524-5278

References

- 1. Li Y, De Stefano V, Li H, et al. Epidemiology of Budd-Chiari syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. Epub ahead of print 7 December 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinre.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kochhar R, Masoodi I, Dutta U, et al. Celiac disease and Budd Chiari syndrome: report of a case with review of literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 21(9): 1092–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boudhina T, Ghram N, Ben Becher S, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome and total villous atrophy in children: apropos of 3 case reports. Tunis Med 1990; 68(1): 59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manzano ML, Garfia C, Manzanares J, et al. Celiac disease and Budd-Chiari syndrome: an uncommon association. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 25(3): 159–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Danalioğlu A, Poturoğlu S, Güngör Güllüoğlu M, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome in a young patient with celiac sprue: a case report. Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14(4): 262–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jadallah KA, Sarsak EW, Khazaleh YM, et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome associated with coeliac disease: case report and literature review. Gastroenterol Rep 2016; 6(4): 308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afredj N, Metatla S, Faraoun SA, et al. Association of Budd-Chiari syndrome and celiac disease. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2010; 34(11): 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aguirrebarrena G, Pulcinelli S, Giovannoni AG, et al. Celiac disease and Budd-Chiari syndrome: infrequent association. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2001; 93(9): 611–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vives MJ, Esteve M, Marine M, et al. Prevalence and clinical relevance of enteropathy associated with systemic autoimmune diseases. Dig Liver Dis 2012; 44(8): 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilcox GM, Mattia AR. Celiac sprue, hyperhomocysteinemia, and MTHFR gene variants. J Clin Gastroenterol 2006; 40(7): 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saibeni S, Lecchi A, Meucci G, et al. Prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in adult gluten-sensitive enteropathy at diagnosis: role of B12, folate, and genetics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3(6): 574–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]