Abstract

Purpose/Objective(s):

To present long-term results of RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927, a randomized lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) trial of 34 Gy in 1 fraction versus 48 Gy in 4 fractions.

Materials/Methods:

This was a phase II multicenter study of medically inoperable non-small cell lung cancer patients with biopsy-proven peripheral T1 or T2 N0M0 tumors, with 1-year toxicity rates as primary endpoint and selected failure and survival outcomes as secondary endpoints. The study opened in September 2009 and closed in March 2011. Final data were analyzed through May 17, 2018.

Results:

Eighty four of 94 patients accrued were eligible for analysis: 39 in arm 1 and 45 in arm 2. Median follow-up time was 4.0 years for all patients, and 6.0 years for those alive at analysis. Rates of grade 3 and higher toxicity were 2.6% in arm 1 and 11.1% in arm 2. Median survival times (in years) for 34 Gy and 48 Gy were 4.1 vs. 4.6, respectively. Five-year outcomes as % (95% CI) for 34 Gy and 48 Gy were: primary tumor failure rate of 10.6 (3.3, 23.1) vs. 6.8 (1.7, 16.9); overall survival of 29.6 (16.2, 44.4) vs. 41.1 (26.6, 55.1); and progression-free survival of 19.1 (8.5, 33.0) vs. 33.3 (20.2, 47.0); respectively. Distant failure as the sole failure or a component of first failure occurred in 6 patients (37.5%) in the 34 Gy arm and in 7 (41.2%) in the 48 Gy arm.

Conclusions:

No excess in late-appearing toxicity was seen in either arm. Primary tumor control rates at 5 years were similar by arm. Median survival times of 4 years for each arm suggest similar efficacy pending any larger studies appropriately powered to detect survival differences.

Keywords: SBRT, early stage, medically inoperable, fractionation, long term follow up

Introduction

Lung stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), also known as stereotactic ablative radiation therapy, is a curative noninvasive treatment for medically inoperable early stage non-small cell lung cancer and involves delivery of very high radiation doses per fraction to small (ie,☒5 cm) discrete targets in the lung without regional micrometastatic spread (ie, without nodal involvement) over few sessions (typically <5).1 A range of SBRT dose/fractionation schedules has been described such that no single regimen has been established as standard. RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00960999) was a phase 2 randomized study that prospectively evaluated 2 dose/fractionation schedules (34 Gy in 1 fraction vs 48 Gy in 4 fractions) to determine whether at 1 year, 1 of them might result in less toxicity while maintaining excellent primary tumor control. The results of this study2 were that 34 Gy in 1 fraction met the prespecified criteria with respect to adverse events (AEs) and primary control and therefore was selected as the appropriate regimen for planned future trials.

Patients enrolled to RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 continued to be followed for tumor control, toxicity, and survival after the initial publication. In the present report, which is an exploratory (ie, noneprotocol specified) analysis, we describe long-term results specifically to understand how potential late events may influence the understanding of each of these SBRT schedules on outcomes in this vulnerable population with lung cancer.

Methods

Patient Eligibility

Detailed eligibility is provided in the previous report(2) but in summary, patients enrolled in this study were 18 years of age or older with a Zubrod performance status score of 0 to 2, judged medically inoperable per protocol-specified criteria, and with early-stage, histologically proven NSCLC defined as American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 6th edition(3) T1 to T2 (≤5 cm) N0M0 after staging by computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) studies. Tumors had to be characterized as “peripheral” per RTOG 0236(4). All patients were required to sign informed consent before being registered on the study.

Treatment planning and delivery

The gross tumor volume (GTV) was outlined on pulmonary CT windows. No additional margin was added for possible microscopic extension (i.e., GTV=CTV). The planning target volume (PTV) definition depended on the method of CT simulation:

Four dimensional CT (4DCT) simulation: an internal target volume (ITV) around the GTV, accounting for tumor motion as defined from the 4D CT dataset, was expanded uniformly by 0.5-cm margin uniformly to generate the PTV;

Non-4DCT simulation: the PTV included the GTV plus an additional 0.5-cm margin in the axial plane and a 1.0-cm margin in the longitudinal plane (craniocaudal).

Patients were randomized to one of two dose/fractionation schemes (arms 1 or 2). Patients on arm 1 received 34 Gy in 1 fraction whereas patients on arm 2 received 4 fractions at 12 Gy per fraction, for a total dose of 48 Gy given over 4 consecutive days. Image guidance capable of confirming the position of the target with each treatment was required. Planning requirements including tumor coverage and normal tissue dose constraints are described in the previous report(2).

Institutional review and accreditation

Prior to enrollment of any patients, the institutional review board for a treatment center was required to review the trial and provide approval for conducting the study. For the purposes of lung SBRT planning and delivery, central credentialing standards for protocol participation were defined by the **** Consortium (ATC), and this included irradiation of a standard chest phantom (supplied by the Radiologic Physics Center, Houston, TX). All sites were also required to obtain central approval of their methods of immobilization, motion assessment and control, and target verification if IMRT was to be used. When a center enrolled its first patient on the trial, central review of the target, normal structure contouring, and dosimetry by the primary investigator or other radiation oncology co-chair was required before treatment delivery and was facilitated by the Image Guided Therapy QA Center at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, to ensure that protocol planning criteria had been met.

Follow-up and endpoints

Patients were seen 6 and 12 weeks after SBRT, then every 3 months for 2 years, every 6 months for next 2 years, and annually thereafter. Comprehensive interval history and physical examination were required at each follow-up visit. Imaging of the chest by CT scan was required at each visit, starting at the 12-week follow-up visit to assess response and toxicity. Follow-up PET scans were recommended for all patients 1 year after SBRT to assess response. Pulmonary function tests (FEV1, DLCO) were conducted at the 12-week visit and then every 6 months for the next 5 years after treatment. Tumors were measured at each follow-up visit using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), and response was graded according to the international criteria proposed in the RECIST Guideline version 1.1(5). Response criteria were not limited to CT assessment but were augmented by PET, biopsy, or both when primary tumor failures or marginal failures were scored. The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of grade 3 or higher adverse events at 1 year that were pre-specified in the protocol; they included cardiac, gastrointestinal, fracture, skin, thoracic, and neurologic disorders. The National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 was used for grading adverse events. Pulmonary function disorders, however, were scored according to the RTOG 0236 schema(4). Secondary endpoints included assessment of primary tumor control, PFS and OS at 1 year, assessment of changes in fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) standardized uptake values (SUV) on PET as a measure of treatment response and outcomes, pulmonary function changes by treatment arm and response, and associations between biomarkers and primary tumor control (PC) and/or grade ≥2 radiation pneumonitis.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint of the original study was the rate of grade ≥3 protocol-specified adverse events (psAEs) at 1 year in each arm. Either study arm was considered promising for further study if the rate of non-psAEs by 1 year exceeded 95% (i.e. the rate of psAEs <5%), and any regimen with a rate of non-psAEs <83% (rate of psAE >17%) was deemed unsafe. The details of sample size justifications may be found in the initial report(2). Primary tumor control (PC) at 1 year was considered as the efficacy endpoint and was defined in the initial report(2). PC was calculated as the proportion of analyzable patients at 1 year (excluding those who died without primary failure) who did not have primary tumor failure (local or marginal). Each experimental regimen was evaluated independently, and a regimen was considered for further evaluation only if both the rate of psAEs <5% (based on the aforementioned 2-stage design) and 1-year PC was ≥90%. If both regimens met both criteria, then the regimen with the lower rate of psAEs would be selected. Analyzable patients were eligible patients who received any protocol treatment and were potentially followed up for at least 1 year. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from registration to date of death (from any cause). Progression-free survival (PFS) was the time from registration to death from any cause, primary failure, involved node failure, regional failure, distant metastasis, or second primary, whichever occurred first. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A 2-sided significance level of .05 was used throughout in the original report. Statistical comparisons of these outcomes were not carried out in analyzing long-term follow up results since this was not part of the original design of the study.

Results

Patient Characteristics

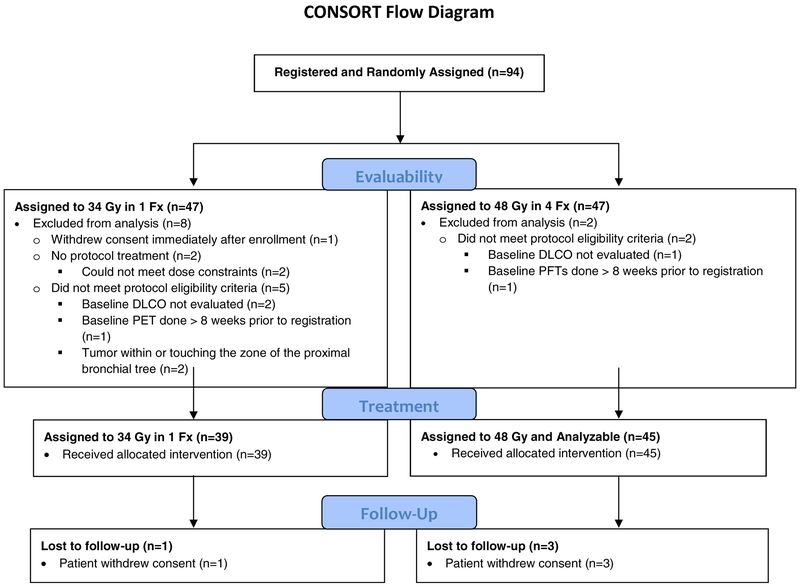

Between September 2009 and March 2011, 94 patients were assigned equally to both arms. A CONSORT diagram is provided in Figure 1. Of these, 84 patients were ultimately eligible, 39 in arm 1 and 45 in arm 2, after 10 cases were excluded for the following reasons by the 34-Gy (n=8) and 48-Gy (n=2) arms, respectively: withdrawal of consent before SBRT in 1 (12.5%) and 0 (0%), baseline DLCO not evaluated in 2 (25%) and 1 (50%), baseline PET not per protocol in 1 (12.5%) and 0 (0%), baseline PFTs not per protocol in 0 (0%) and 1 (50%), tumor location not per protocol 2 (25%) and 0 (%), and did not receive protocol treatment in 2 (50%) and 0 (0%) patients. This analysis used all data received RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 Statistics and Data Management Center through termination of data collection on May 17, 2018. Pretreatment characteristics for evaluable patients were unchanged from the initial report and are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for RTOG 0915

Table 1-.

Selected pretreatment patient and tumor characteristics of patients enrolled on RTOG 0915/NCCTG N

| 34 Gy in 1 fx (n=39) |

48 Gy in 4 fx (n=45) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 75 (57–89) | 75 (52–87) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 16 (41.0%) | 22 (48.9%) |

| Female | 23 (59.0%) | 23 (51.1%) |

| Zubrod Performance Status* | ||

| 0 | 8 (20.5%) | 15 (33.3%) |

| 1 | 22 (56.4%) | 19 (42.2%) |

| 2 | 9 (23.1%) | 11 (24.4%) |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 9 (23.1%) | 16 (35.6%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 23 (59.0%) | 26 (57.8%) |

| Non-small cell lung cancer NOS | 7 (17.9%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Median tumor diameter, cm (min-max) | ||

| Median | 2.0 (1–4.98) | 2.0 (0.08–4.3) |

| T Stage | ||

| T1 | 32 (82.1%) | 40 (88.9%) |

| T2 | 7 (17.9%) | 5 (11.1%) |

| Peak SUV | (n=38) | (n=43) |

| Median (min-max) | 6.5 (1.0–24.6) | 6.3 (1.0–28.0) |

| FEV1 (1/sec) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 1.32 (0.49–2.67) | 1.21 (0.37–3.59) |

| FEV1 (%) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 60.0 (17.0–118.0) | 54.0 (0.7–121) |

| DLCO (%) | (n=36) | (n=45) |

| Median (min-max) | 49.5 (1.5–93.0) | 45.0 (6.2–93.0) |

The median follow-up time was 4.0 years (range 0.1–8.0) for all patients, 3.5 years (range 0.1–8.0) for arm 1 and 4.0 years (range 0.3–7.0) for arm 2. For patients alive at analysis, the median follow up time was 6.0 years (range 1.6–8.0) for all patients, 7.0 years (range 3.2–8.0) for arm 1 and 6.0 years (range 1.6–7.0) for arm 2.

Tumor Response

Comparing arm 1 to arm 2, a complete tumor response was observed in 13 (33.3%) and 19 (42.2%) patients, and a partial response was seen in 14 (35.9%) and 16 (35.6%) patients for arms 1 and 2, respectively. These rates of best observed responses were essentially unchanged since the initial report. The number of patients with a recommended PET assessment at one year was 23 (59%) and 29 (64%) in the 34 Gy and 48 Gy arms, respectively.

Toxicity

The grade 3 and higher treatment-related toxicity profile was unchanged since the previous report. At this analysis, one arm 1 patient (2.6%) and five arm 2 patients (11.1%) were reported to have experienced treatment-related (definitely, probably, or possibly) grade 3 and higher events. With respect to grade 2 or less toxicities compared to the previous report, one patient on the 34 Gy arm which had no treatment-related toxicity reported previously had a grade 1 AE, and one patient on the 48 Gy arm which had previously had a maximum treatment-related AE of grade 1 had since experienced a grade 2 AE. Four arm 2 patients had subsequent grade 3 changes in spirometry. With respect to a selected psAE, there were no new reports of grade 3 or higher chest wall-associated toxicity. No new grade 5 psAEs were reported with longer follow-up. The supplementary appendix shows all grades of reported psAEs by treatment arm.

Patterns of Failure

Table 2 provides details on the patterns of failure. Of note, distant failure as the sole failure or a component of first failure occurred in 6 patients (37.5%) in the 34 Gy arm and in 7 (41.2%) in the 48 Gy arm. Second primary cancers as part of any failure were similar between both arms.

Table 2.

Patterns of failure on RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927

| 34 Gy in 1 fraction (n = 16) |

48 Gy in 4 fraction (n = 17) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pattern of first failure | ||

| Distant* | 3 (18.8%) | 7 (41.2%) |

| Distant, second primary* | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Local | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Local, regional | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Local, regional, distant* | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Second primary | 5 (31.3%) | 7 (41.2%) |

| Pattern of any failure | ||

| Distant† | 3 (18.8%) | 6 (35.3%) |

| Distant, second primary† | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Local | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Local, distant† | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Local, regional | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Local, regional, distant† | 3 (18.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Local, second primary | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Regional, distant† | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Second primary | 4 (25.0%) | 5 (29.4%) |

Arm 1: First site(s): 1 patient with bone, other; 1 patient with brain; 4 patients with contralateral lung.

Arm 2: First site(s): 1 patient with contralateral lung; 1 patient with contralateral lung, pleura, bone; 2 patients with other; 3 patients with pleura.

Arm 1: Any site(s): 1 patient with bone, other; 1 patient with brain; 4 patients with contralateral lung; 1 patient with contralateral lung, brain, other; 1 patient with liver; 1 patient with other.

Arm 2: Any site(s): 1 patient with brain; 2 patients with contralateral lung; 1 patient with contralateral lung, pleura, bone; 1 patient with contralateral lung, pleura, brain; 2 patients with other; 2 patients with pleura; 1 patient with pleura, brain.

Outcomes

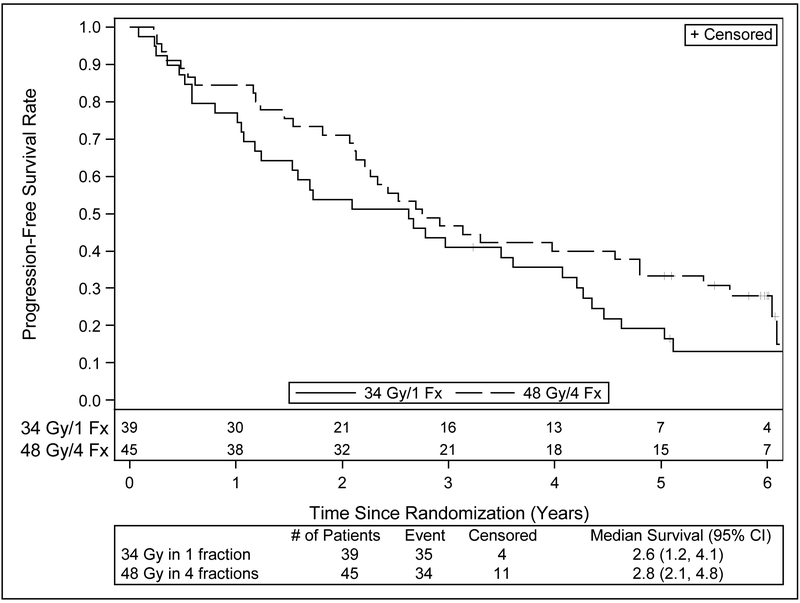

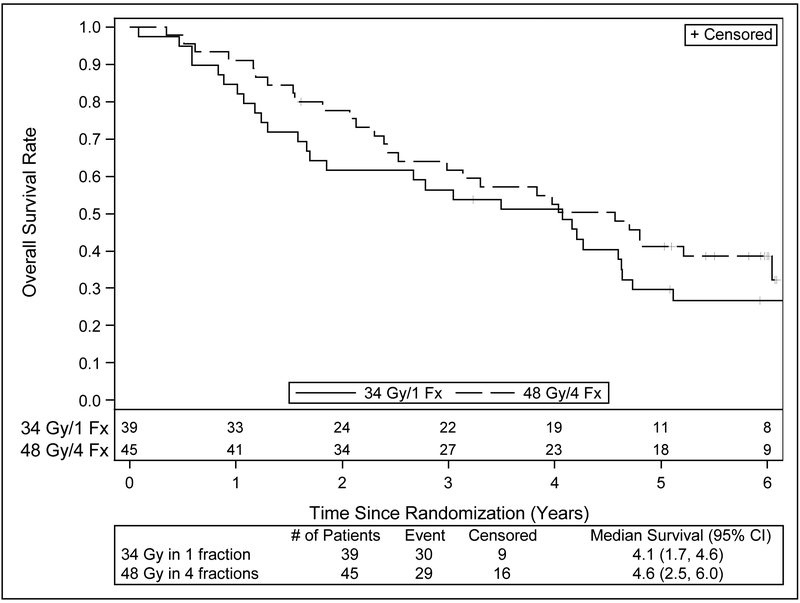

Table 3 provides a summary of outcomes of interest. Figures 2 and 3 present PFS and OS survival curves by treatment arm. Since the previous report, there have been additional failures in all endpoints. Primary tumor failure has been reported in an additional 4 patients on the 34 Gy arm for a total of 5 events; the number of events on the 48 Gy arm is unchanged. This change is also reflected in the number of events for local failure. Two additional patients in the 34 Gy arm have experienced regional failure for a total of 4 events, while the number of events in 48 Gy arm is unchanged at 2 events. Four patients in 34 Gy arm and 4 patients in the 48 Gy arm have experienced distant failure since the previous report, bringing the total number of events to 9 and 10, respectively. Deaths have been reported for an additional 13 and 12 patients, respectively bringing the total number of deaths to 30 (76.9%) on the 34 Gy arm, and 29 (64.4%) on the 48 Gy arm. Progression-free survival events have increased accordingly, to 35 (89.7%) on the 34 Gy arm and 34 (75.6%) on the 48 Gy arm. Approximately one third of the patients’ cause of death was unknown, and another third was related to causes other than cancer or the treatment under study.

Table 3-.

Summary of outcomes with long term follow up of RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927.

| Outcome Measure | 34 Gy in 1 fx Estimate (95% CI) |

48 Gy in 4 fx Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Median OS (years) | 4.1 (1.7,4.6) | 4.6 (2.5,6.0) |

| Median PFS (years) | 2.6 (1.2,4.1) | 2.8 (2.1,4.8) |

| 5 year PTF (%) | 10.6 (3.3,23.1) | 6.8 (1.7, 16.9) |

| 5 year OS (%) | 29.6 (16.2, 44.4) | 41.1 (26.6,55.1) |

| 5 year PFS (%) | 19.1 (8.5,33.0) | 33.3 20.2, 47.0) |

| 5 year Second Primary (%) | 15.5 (6.1,28.9) | 13.3 (5.3,25.1) |

fx=fraction; CI=confidence interval, PTF=primary tumor failure; OS=overall survival; PFS=progression-free survival

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival with long term follow up of RTOG 0915.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall survival with long term follow up of RTOG 0915.

Discussion

RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 was a prospective, randomized phase II trial that evaluated two lung SBRT dose/fractionation schedules in medically inoperable, peripherally located early-stage lung cancer patients. Using a primary endpoint of grade 3 or higher toxicity rates at one year after therapy and then matching those results to the rates of local control achieved by each regimen, 34 Gy in one fraction emerged as the more favorable arm for future study when compared to 48 Gy in 4 fractions because it had the least toxicity for equal efficacy of the two regimens. At the time of its first publication in 2015, the median follow up time for the patients accrued to the study was 30.2 months.

Given that published lung SBRT experience dates back only approximately 20 years and involves few reports that are prospective studies, there is a strong interest in understanding long-term outcomes and toxicity that can be derived from SBRT clinical trials long after completion of their protocol therapy. These long-term analyses are particularly valuable because their data are prospectively derived and thus help not only in understanding cancer control issues, but in identifying potential late toxicities that might impact the medically vulnerable population that is being treated with SBRT. For example, long-term results from RTOG 0236, the first multi-center cooperative group prospective trial in lung SBRT in North America, were presented in abstract form at ASTRO 2014(6) after a median follow up of 4 years, compared to their initial publication in 2010 after a median follow up of 34.4 months(4). Inasmuch as the same principles apply to a long-term analysis of RTOG 0915/ NCCTG N0927, its results are of specific interest since they can also provide insights into single-fraction SBRT outcomes which have not till now been described in the literature.

Since toxicity was the primary endpoint of the original study, the first important finding in the current report is the stability of the toxicity profile over time, with the proportion of grade 3 and higher events remaining stable for both treatment arms and no new grade 4 or 5 events described. A specific psAE of interest in the first report was the rate of chest wall toxicities which did not exceed grade 2 in either arm. This persisted on long-term follow up, with no report of late grade 3 or higher chest wall events. Secondly, primary tumor failure rates have remained modest with time at around 7% in each arm, with the absolute values for each arm being numerically similar, although no statistical comparisons were feasible in this analysis. Of note, these PTF results are comparable to the estimated 5-year result of 7.3% seen in the long-term RTOG 0236 results(6).

Overall patterns of failure remained similar between arms with time, so that distant failure was the dominant such outcome in each arm at a rate of around 30%. This rate echoed once again the long term results of RTOG 0236, where the 5-year disseminated failure rate was 23.6%. The rate of second primary development was proportionally higher in the 48 Gy arm but this likely reflects the effect of small numbers of events among a total of 16 patients with failure.

With respect to survival outcomes, median OS and PFS were similar in each arm at around 4 years. Once again, a parallel is seen in the long term results of RTOG 0236 where the median survival was also 4 years. The biggest difference between the arms was seen in the absolute values for 5-year OS, where the 34 Gy arm was 12% less than the 48 Gy arm. Comparisons of survival data at this time point need caution because the study was not powered to address this question; the observation could easily be a result of the small number of patients remaining in follow up. This drop-off in analyzable patients with time is a reminder of the medically vulnerable nature of this population such that patients have competing risks of death from their significant medical co-morbidities such as COPD. In that respect, a minimum of 1/3 of patients in total had documented non-cancer related deaths in this study. This highlights the main interpretative limitation of this randomized study in that it was not powered for survival. As noted in the original report on RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 (2), the appropriate means for establishing the optimal lung SBRT schedule would be a phase 3 trial using OS as the primary endpoint.

On the specific question of generalizing the use of single-fraction lung SBRT, this long-term follow up report supports the safety and efficacy of this schedule in the management of peripheral inoperable lung tumors, and this appears true when compared to both its study comparator arm of 48 Gy but also in comparison to the long term results of RTOG 0236. In that regard, it can be argued that all three schedules present appropriate choices in the management of early stage disease. Defining the “standard” lung SBRT schedule for peripheral tumors would however require prospective testing. In comparison, for tumors deemed “central”, the role of single fractions remains ill-defined and not recommended, with preliminary reports suggesting toxicity when this schedule is used (7). Additional support for single-fraction therapy can be extrapolated from a retrospective study of 65 patients comparing single-fraction versus multi-fraction lung SBRT for pulmonary oligometastases. Siva et al(8) reported comparable local control, overall survival and toxicity rates between single-fraction [26 Gy prescribed for peripheral targets and 18 Gy for central targets] and multi-fraction SBRT [48 Gy/4 or 50 Gy/5 for peripheral targets and 50 Gy/5 for central targets] treatments in patients with FDG-PET-staged pulmonary oligometastases. More recently, the results of a randomized phase II study of 30 Gy in 1 fraction versus 60 Gy in 3 fractions for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer initiated by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) were presented in abstract form and showed equal toxicity and efficacy between the two arms(9): comparing single-fraction to three-fraction treatment, 8 (16%) and 6 (12%) patients on each arm, respectively, experienced grade 3 thoracic side effects. Neither arm had grade 4 or higher respiratory events. There were no differences in OS or PFS between arms (log-rank P=0.44 and 0.99, respectively). The RPCI investigators also have recently reported on their 8-year retrospective experience comparing the same single-fraction versus three-fraction lung SBRT schedules for 159 tumors and found no differences in outcomes between them (10). Since outcomes of single-fraction therapy appear then to be comparable to fractionated SBRT schedules, patient-specific considerations may encourage broader institutional adoption of single fractions for early stage peripheral lung cancer. Single-fraction SBRT has been noted to favor patients because of its “ease of delivery” (11), while Filippi et al (12) have commented that it use supports “high patient compliance [with therapy], lower costs and high feasibility”.

Conclusions

Long term follow up data for RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927 revealed no excess development of late-appearing toxicity in either arm coupled to persistently high rates of local control. The median OS of 4 years for each arm suggest similar efficacy between each arm. Single-fraction therapy remains an appropriate option for treating early stage inoperable lung cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

The final result of RTOG 0915/NCCTG N0927, a randomized lung stereotactic body radiation therapy trial of 34 Gy in 1 fraction (arm 1) versus 48 Gy in 4 fractions (arm 2), was that 34 Gy emerged as the least toxic regimen but was equally efficacious. Long-term follow-up results show no change by arm in toxicity rates or tumor control with time for similar median survivals, supporting the study’s original conclusions.

Funding:

This project was supported by grants U10CA180868 (NRG Oncology Operations), U10CA180822 (NRG Oncology SDMC), U24CA180803 (IROC), UG1CA189867 (NCORP) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the 59th Annual meeting of ASTRO, September 24, 2017, San Diego, CA; and at the IASLC 18th World Conference on Lung Cancer, October 17, 2017, Yokohama, Japan.

Conflicts of interest: Nothing to disclose Ajlouni, Belani, Choy, Gomez-Suescun, Iyengar, Komaki, McGarry, Olivier, Parker, Singh, Stephans, Urbanic, Videtic and Yom. Dr. Bradley reports grants and personal fees from Mevion Medical Systems, Inc., personal fees and other from Varian Medical Systems. Dr. Chang reports other from Global Oncology One, grants from BMS. Dr. Gopaul reports personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Jansen. Ms. Paulus reports a grant from National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study. Dr. Robinson reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Varian, personal fees and non-financial support from ViewRay, grants from Elekta, other from Radialogica; has a patent ECGI and SBRT for cardiac arrhythmia pending. Dr. Timmerman reports grants from Varian Medical Systems, grants from Elekta Oncology, grants from Accuray, Inc.

References

- 1.Videtic GM, Stephans KL. The role of stereotactic body radiotherapy in the management of non-small cell lung cancer: An emerging standard for the medically inoperable patient? Curr Oncol Rep 2010; 12:235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Videtic GM, Hu C, Singh AK, et al. A randomized phase 2 study comparing 2 stereotactic body radiation therapy schedules for medically inoperable patients with stage I peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: NRG oncology RTOG 0915 (NCCTG N0927). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;93:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorax. Greene, editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA 2010; 303:1070–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmerman RD, Hu C, Michalski, et al. Long-term Results of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy in Medically Inoperable Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1287–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma SJ, Mix M, Rivers C, et al. Mortality following single-fraction stereotactic body radiation therapy for central pulmonary oligometastasis. J Radiosurg SBRT 2017;4:325–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siva S, Kirby K, Caine H, et al. Comparison of single-fraction and multi-fraction stereotactic radiotherapy for patients with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-staged pulmonary oligometastases. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2015;27: 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh AK, Suescun JAG, Stephans KL, et al. A phase 2 randomized study of 2 stereotactic body radiation therapy regimens for medically inoperable patients with node-negative, peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;98:221–222. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma SJ, Serra LM, Syed YA, et al. Comparison of single- and three-fraction schedules of stereotactic body radiation therapy for peripheral early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2018;19:e235–e240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte RI, Crownover R, Murphy MJ, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for lung tumors: Preliminary report of a phase I trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1097–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filippi AR, Badellino S, Guarneri A, et al. Outcomes of single fraction stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for lung metastases. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2014;13:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.