Abstract

Introduction:

Candida species is the common form of opportunistic fungal infections, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. Fluconazole is the first-line therapy for candidiasis as it is affordable and readily available. However, the antifungal resistance pattern in high-risk patients is a major concern.

Aim:

The objective of the present study was to assess the anticandidal activity of curcumin-silver nanoparticles (C-Ag-NPs) against fluconazole-resistant Candida species isolated from HIV patients.

Materials and Methods:

Ten milliliters of 0.1 M silver nitrate (AgNO3) and 3 ml curcumin solution was heated in a water bath for 1 h at 60°C. The formation of the Ag-NPs was determined by color change from light yellow to brownish. The solution was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min and was washed with ethanol and later lyophilized for 24 h to obtain the purified curcumin-Ag-NPs (C-Ag-NPs). A stock of 1 mg/ml of C-Ag-NPs was prepared in deionized water. The agar diffusion test and broth dilution tests were conducted to determine the anticandidal activity of C-Ag-NPs.

Results:

C-Ag-NPs showed a better antifungal activity compared to curcumin and AgNO3 solution. Candida glabrata and Candida albicans were the most inhibited and Candida tropicalis was the least inhibited species. The mean zone diameter was 22.2 ± 0.8 mm, 20.1 ± 0.8 mm, and 16.4 ± 0.7 mm against C. glabrata, C. albicans and C. tropicalis respectively. Other Candida species under the study were also inhibited. Inhibitory activity was dose dependent and it increased with concentration. The minimum inhibitory concentration values for different Candida species ranged from 31.2 μg/ml to 250 μg/ml.

Conclusion:

This is the first report on the antifungal activity of C-Ag-NPs against fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates. C-Ag-NPs can be explored further to identify a potential drug candidate that can be used for the treatment of candidiasis due to fluconazole-resistant strains of Candida species.

Keywords: Antifungal activity, Candida species, curcumin, fluconazole-resistant Candida strains, silver nanoparticle

Introduction

Infections due to Candida species are increasing, as also their resistance to antifungal drugs. The clinical entities of candidiasis vary with immune status. Immunocompromised patients are more prone to develop both superficial and serious life-threatening Candida infections.[1,2] Significant increase in the incidence of candidiasis and the emergence of antifungal resistance[3] contributes to long hospital stay, health-care cost, morbidity and mortality. The increase in resistant strains and adverse reaction of the available antifungals necessitates a search for new targets for new antifungal agents.[4,5] The World Health Organization states that >80% of the world’s population relies on traditional medicine for their primary health-care needs. In view of possible difficulties, strong incentives are there to develop new, cost-effective, nontoxic, broad-spectrum natural fungicides.

Curcuma longa L., commonly known as “turmeric,” belongs to Zingiberaceae family is an ancient coloring spice of Asia and has been conventionally used as an antimicrobial agent as well as an insect repellant.[6,7] The polyphenolic components of C. longa are collectively named curcuminoids, which include mainly diferuloylmethane curcumin (77%), demethoxycurcumin (17%) and bisdemethoxycurcumin (3%).[8] The biological activities of turmeric are attributed to curcumin, a bioactive polyphenol component, predominantly present in turmeric. Several reports of extended-spectrum antimicrobial activity of curcumin are available. Its safety has been proved in animal studies and in Phase I clinical trials, even doses up to 12 g/day were found to be nontoxic.[9] However, its poor bioavailability has been a major drawback of this potentially valuable therapeutic agent. Low aqueous solubility, tendency to degrade in the gastrointestinal tract in the physiological environment, high rate of metabolism, and rapid systemic elimination are the causes for its low bioavailability. Either very low or undetectable levels of curcumin have been noted in blood by oral administration of curcumin. To achieve considerable therapeutic effects on the human body, one has to swallow 24–40 curcumin capsules of 500 mg each. These doses are too high and hence not feasible to be incorporated in clinical trial.[9,10] To utilize the potential benefits of this wonder chemical, approaches based on the use of adjuvants, chelating of curcumin with metals or combining with other dietary agents, have been investigated.

The antifungal effect of curcumin is due to the downregulation of 5,6 desaturase (ERG3) leading to significant reduction in ergosterol of fungal cell. As a result, biosynthetic precursors of ergosterol accumulate, leading to cell death through generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).[11] Reduction in proteinase secretion and alteration of membrane-associated properties of ATPase activity are other possible mechanisms involved in fungicidal action of curcumin.[12] Inhibition of H+-extrusion resulting in intracellular acidification can be possible mechanism for cell death of Candida species.[13] Curcumin inhibits hyphal formation by targeting the global suppressor thymidine uptake 1.[14]

Silver ions have long been known to possess a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activities.[15] Silver is more toxic to microbes and less toxic to mammalian cells. Silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) show good antifungal effects, by producing ROS such as superoxide anion (O2−), hydroxyl radical (OH) and singlet oxygen with subsequent oxidative damage.[16] It has been reported that there is a loss of membrane integrity after treatment with Ag-NPs.[17]

Materials and Methods

Preparation of curcumin solution

Curcumin (≃% w/w) was purchased from Grenera, India. The curcumin solution was prepared according to the standard protocol.[18] Five hundred milligrams of curcumin powder was added to 100 ml of sterile deionized water. The mixture was heated at 80°C for 30 min. The heterogeneous mixture was filtered through Whatman filter paper no. 1 to get a homogeneous solution of curcumin in water.

Preparation of curcumin-silver nanoparticle

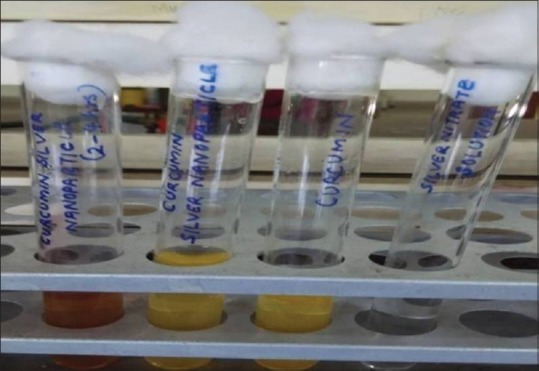

A total of 10 ml of silver nitrate (AgNO3) (Merck-CAS7761-88-8) 0.1 M and 3 ml curcumin solution were mixed in a 50 ml conical flask and heated in a water bath for 1 h at 60°C.[19] The formation of the Ag-NPs was monitored and determined through a change of appearance (color) of the mixture that changed from light yellow to brownish [Figure 1]. The synthesis was further validated using ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy (UV-2450, Shimadzu, Japan). The solution was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min. Then, the product was washed with ethanol and was lyophilized (Free Zone 6, USA) for 24 h to obtain the purified curcumin-Ag-NPs (C-Ag-NPs). A stock of 1 mg/ml of C-Ag-NPs was prepared in deionized water.

Figure 1.

Formation of curcumin silver nanoparticles

Microorganisms

Microbial type culture collection centre (MTCC) strains of Candida species – Candida albicans (MTCC 3017), Candida glabrata (MTCC 3019) and Candida krusei (MTCC 9215) were used. These strains were obtained from MTCC, Chandigarh, India and used as quality controls. Twenty-one fluconazole-resistant Candida strains isolated from different samples of HIV-infected cases were also included in the study. Fluconazole resistance was confirmed by antifungal susceptibility testing according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards.[20] The 21 strains included 5 C. albicans, 5 C. tropicalis, 5 C. krusei, 3 C. glabrata, 2 C. parapsilosis and 1 C. kefyr.

Evaluation of antifungal activity-broth dilution method

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to the fungal strains was determined by the resazurin microtiter method[21] with slight modifications. One hundred microliters of C-Ag-NPs was added into the first row of the sterile 96 well plate. To all other wells, 50 μL of RPMI 1640 broth was added. Serially descending concentrations were prepared with final volume of 50 μL in each well. Ten microliters of resazurin indicator solution was added. Ten microliters of inoculum adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard was added, mixed and incubated at 37°C for 24–48 h. The blue color indicated the inhibition of growth. The lowest concentration which inhibited the visual growth was recorded as MIC. All the analyses were performed in triplicate. Amphotericin B (0.0313–16 μg/ml) and RPMI 1640 broth without antifungal agents were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Evaluation of antifungal activity-agar diffusion method

The antifungal activity against the fungal strains was done according to the CLSI guidelines M44 A, 2008.[20] Wells of standard diameter (5 mm) were bored in the modified MHA using sterile well puncher. A lawn culture was done with inoculum already adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 colony-forming unit/mL). Ten microliters, 20 μL, and 50 μL of Ag-NPs were added to the respective wells. The concentration of C-Ag-NPs in each well was 10 μg, 20 μg, and 50 μg, respectively. Fifty microliters of curcumin and 0.1 M AgNO3 were included as controls. The concentration of curcumin in 50 μL of curcumin solution was 250 μg. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for approximately 18–24 h. The diameter of zones of inhibition produced by varied concentrations of C-Ag-NPs against the test organisms was measured after overnight incubation. Next day, the diameter of zones of inhibition produced by varied concentrations of the extracts against the test organisms was measured.

Results

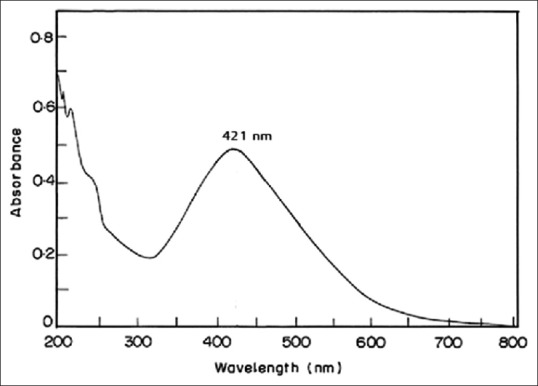

UV-vis spectroscopy is the most common and reliable technique for the preliminary characterization of synthesized nanoparticles and stability of Ag-NPs.[22] Any peak at the range between 400 and 440 nm shows the production of Ag-NPs.[23] In the present study, it showed the peak at 421 nm [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Ultraviolet-visible spectrum

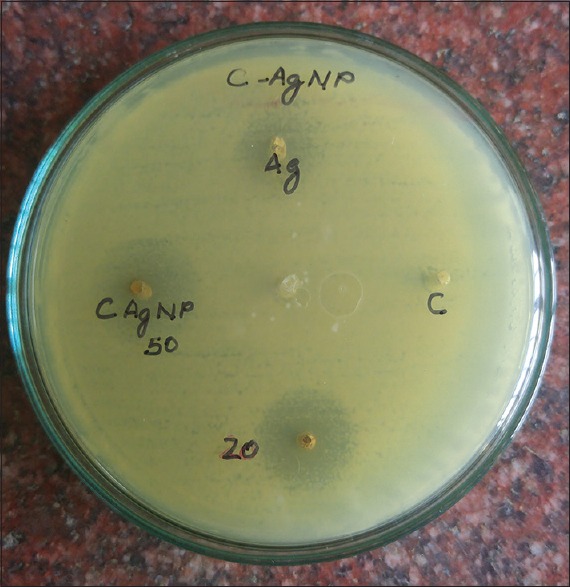

Table 1 and Figure 3 show the antifungal activity of C-AgNP, curcumin, and AgNO3 against the MTCC strains and clinical isolates of Candida species. C-AgNP showed a better antifungal activity compared to curcumin and AgNO3 solution. C. glabrata and C. albicans were the most inhibited. The zone diameter obtained with 50 μL of C-Ag-NPs for C. glabrata and C. albicans was 20.6 ± 0.8 and 20.1 ± 0.8, respectively. C. tropicalis was the least inhibited with a zone of inhibition of 16.4 ± 0.7. An increase in diameter of the zone size was noticed with increase in concentration. Fifty microliters of curcumin solution inhibited the growth of all the MTCC strains tested. However, the diameter of zone of inhibition was lesser than C-Ag-NPs. As in curcumin solution, AgNO3 solution also inhibited all the MTCC strains under study.

Table 1.

The antifungal activity of the C-Ag-NPs against MTCC and fluconazole resistant Candida strains

| Candida species | Concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-AgNPs | Curcumin 50 µl | AgNO3 50 µl | |||

| 10 µl | 20 µl | 50 µl | |||

| Zone diameter (mm) | |||||

| C. albicans (MTCC) | 3.1±0.18 | 10±0.11 | 20.1±0.8 | 1±0.22 | 0.8±0.55 |

| C. albicans | 2.1±0.2 | 9±0.21 | 20±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 | 0.6±0.55 |

| C. glabrata (MTCC) | 5.2±0.42 | 12±0.11 | 20.6±0.8 | 0.8±0.02 | 0.7±0 |

| C. glabrata | 4.2±0.4 | 12±0.18 | 20.5±0.8 | 1.2±0.12 | 0.7±0.03 |

| C.krusei (MTCC) | 3.7±0.63 | 9±0.4 | 15.1±0.3 | 1.6±0.12 | 1.5±0.01 |

| C.krusei | 3.7±0.23 | 9.5±0.3 | 19.5±0.1 | 1.6±0.62 | 1.5±0.01 |

| C. tropicalis | 2.5±0.11 | 8.6±0.02 | 16.4±0.7 | 0.6±0.02 | 0.4±0.85 |

| C. parapsilosis | 1.8±0.2 | 8.1±0.12 | 18.4±0.14 | 1.1±0.14 | 1±0.41 |

| C. kefyr | 2.6±0.02 | 7.8±0.23 | 19.5±0.22 | 0.8±0.02 | 0.9±0.1 |

MTCC: Microbial Type Culture Collection Centre, C-Ag-NPs: Curcumin -silver nanoparticles, AgNO3: Silver nitrate, C. albicans: Candida albicans, C. glabrata: Candida glabrata, C. krusei: Candida krusei, C. tropicalis: Candida tropicalis, C. parapsilosis: Candida parapsilosis, C. kefyr: Candida kefyr

Figure 3.

Anticandidal action of curcumin silver nanoparticles

MIC was calculated as the lowest concentration at which the visual growth was inhibited. The MIC for C. glabrata and C. albicans was 31.2 μg/ml and 62.5 μg/ml, respectively. For C. tropicalis, the MIC was recorded as 250 μg/ml. The MIC values for C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, and C. kefyr were 125 μg/ml, 125 μg/ml and 62.5 μg/ml, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, C-Ag-NPs exhibited an excellent antifungal activity against all the fungal strains tested; however, the inhibitory effects differed with regard to different fungal species. The least inhibited was C. tropicalis. The activity was dose dependent and the inhibition zone diameter increased with increase in concentration of curcumin.

Ungphaiboon et al. showed that the methanol extract of turmeric exhibited antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans and C. albicans with MIC values of 128 and 256 μg/mL, respectively.[24] Another study by Neelofar et al. described excellent anticandidal activity of curcumin against 4 ATCC strains and 10 clinical isolates of Candida species. The MIC values range from 250 to 2000 μg/mL.[12] Curcumin was found to be active against fluconazole-resistant Candida strains. The MIC90 values for sensitive and resistant strains were 250–650 and 250–500 μg/mL, respectively.[13] Previous studies of antifungal activity of C-Ag-NPs against Candida species, especially fluconazole resistant strains, are not available.

Curcumin markedly prevents the adhesion of Candida species to buccal epithelial cells and it was found to be more effective compared to fluconazole.[25] Studies also proved that curcumin-mediated photodynamic therapy can reduce the biofilm biomass of C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis. Synergistic activity was noted with curcumin, fluconazole and amphotericin B against Candida species and can be due to the accumulation of ROS.[11,14]

The low bioavailability of curcumin, low aqueous solubility, tendency to degrade in the gastrointestinal tract in the physiological environment, high rate of metabolism and rapid systemic elimination can be solved by making it react with silver ions. Several antibiotics use silver compounds such as metallic silver, AgNO3, silver sulfadiazine for treatment of burns, wounds and several infections[26] and are available in the market as topical agents. However, there are data regarding toxic effect of silver ions at 5 mM concentration. Hence, by the formation of C-Ag-NPs, the toxic effect due to high concentration can be reduced and also the microbicidal activity can be improved.

Conclusion

It can be concluded from the results of this study that curcumin Ag-NPs are very effective anticandidal agents. Thus, it can contribute in global problem of the emergence of resistance and overcome the limitations, namely, toxicity and health-care costs. The antifungal potential of C-Ag-NPs is high as outlined, and indisputably the prospect is great to develop it as a topical chemotherapeutic agent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hasan F, Xess I, Wang X, Jain N, Fries BC. Biofilm formation in clinical Candida isolates and its association with virulence. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:753–61. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortega M, Marco F, Soriano A, Almela M, Martínez JA, López J, et al. Candida species bloodstream infection:Epidemiology and outcome in a single institution from 1991 to 2008. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:157–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira GH, Müller PR, Szeszs MW, Levin AS, Melhem MS. Five-year evaluation of bloodstream yeast infections in a tertiary hospital:The predominance of non-C albicans Candida species. Med Mycol. 2010;48:839–42. doi: 10.3109/13693780903580121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White JM, Chaudhry SI, Kudler JJ, Sekandari N, Schoelch ML, Silverman S., Jr Nd:YAG and CO2 laser therapy of oral mucosal lesions. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1998;16:299–304. doi: 10.1089/clm.1998.16.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sardi JC, Almeida AM, Mendes, Giannini MJ. New antimicrobial therapies used against fungi present in subgingival sites –A brief review. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:951–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araújo CC, Leon LL. Biological activities of Curcuma longa L. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:723–8. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudrappa T, Bais HP. Curcumin, a known phenolic from Curcuma longa attenuates the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in whole plant and animal pathogenicity models. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:1955–62. doi: 10.1021/jf072591j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chattopadhyay I, Biswas K, Bandyopadhyay U, Banerjee RK. Turmeric and curcumin:Biological actions and medicinal applications. Curr Sci. 2004;87:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin:Problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:807–18. doi: 10.1021/mp700113r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basniwal RK, Buttar HS, Jain VK, Jain N. Curcumin nanoparticles:Preparation, characterization, and antimicrobial study. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:2056–61. doi: 10.1021/jf104402t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma M, Manoharlal R, Negi AS, Prasad R. Synergistic anticandidal activity of pure polyphenol curcumin I in combination with azoles and polyenes generates reactive oxygen species leading to apoptosis. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:570–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neelofar K, Shreaz S, Rimple B, Muralidhar S, Nikhat M, Khan LA, et al. Curcumin as a promising anticandidal of clinical interest. Can J Microbiol. 2011;57:204–10. doi: 10.1139/W10-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan N, Shreaz S, Bhatia R, Ahmad SI, Muralidhar S, Manzoor N, et al. Anticandidal activity of curcumin and methyl cinnamaldehyde. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:434–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma M, Manoharlal R, Puri N, Prasad R. Antifungal curcumin induces reactive oxygen species and triggers an early apoptosis but prevents hyphae development by targeting the global repressor TUP1 in Candida albicans . Biosci Rep. 2010;30:391–404. doi: 10.1042/BSR20090151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger TJ, Spadaro JA, Chapin SE, Becker RO. Electrically generated silver ions:Quantitative effects on bacterial and mammalian cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976;9:357–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.9.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, Kim JH, Park SJ, Lee HJ, et al. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;3:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasrollahi A, Pourshamsian K, Mansourkiaee P. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles on some fungi. Int J Nano Dim. 2011;1:233–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagannathan R, Abraham PM, Poddar P. Temperature-dependent spectroscopic evidences of curcumin in aqueous medium:A mechanistic study of its solubility and stability. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:14533–40. doi: 10.1021/jp3050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manonmani P, Ramar M, Geetha N, Arasu MV, Erusan RR, Mariselvam R, et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using natural products from Acalypha indica (Kuppaimeni) and Curcuma longa (turmeric) on antimicrobial activities. IJPRBS. 2015;4:151–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.CLSI M44- A Reference Method for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts Disc Diffusion-Approved Standard. 2008 Apr; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarker SD, Nahar L, Kumarasamy Y. Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods. 2007;42:321–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sastry M, Patil V, Sainkar SR. Electrostatically controlled diffusion of carboxylic acid derivatized silver colloidal particles in thermally evaporated fatty amine films. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:1404–10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das R, Nath SS, Chakdar D, Gope G, Bhattacharjee R. Preparation of silver nanoparticles and their characterization. J Nanotechnol. 2009;5:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ungphaiboon S, Supavita T, Singchangchai P, Sungkarak S, Rattanasuwan P, Itharat A. Study on antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of turmeric clear liquid soap for wound treatment of HIV patients. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol. 2005;27:269–578. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins CV, da Silva DL, Neres AT, Magalhães TF, Watanabe GA, Modolo LV, et al. Curcumin as a promising antifungal of clinical interest. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:337–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rai M, Yadav A, Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]