Abstract

This is a protocol for a Cochrane Review (Qualitative). The objectives are as follows:

The overall objective of this QES is to explore and explain probable gender differences in the health literacy of migrants. Exploring possible gender differences in the context of migration will supplement the linked effectiveness review by providing a comprehensive understanding of the role that any gender differences may play in the development, delivery, and ultimately, the effectiveness of interventions for improving the health literacy of female and male migrants. This QES has the following specific objectives.

To explore whether gender differences in the health literacy of migrants exist.

To identify factors that may underlie gender differences in the four steps of health information processing (access, understand, appraise and apply).

To explore and explain gender differences potentially found ‐ or not found ‐ in the effectiveness of health literacy interventions assessed by the linked effectiveness review.

To explain ‐ in a third synthesis ‐ to what extent gender and migration‐specific factors may play a role in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions.

Background

There is some empirical research evidence on the perceived health status and health literacy of migrants, or people with a migrant background (those who have either migrated themselves, or at least one of their parents was a migrant) (Igel 2010). Some have conducted cross‐sectional studies using individual questionnaires or household surveys to collect data on the health status of different migrant groups. Differences have been reported in the health status of people with and those without migrant backgrounds(Igel 2010; Morawa 2014). Differences have also been reported between female and male migrants (Maksimovic 2014; Müller 2017). Research studies on the health status of different migrant groups show differences, particularly in mental health, between female and male migrants. Female migrants reported higher stress levels, anxiety, or symptoms of depression than males (Morawa 2014; Müller 2017). Interestingly, more differences in mental health are reported between female migrants and non‐migrants, but smaller differences between male migrants and non‐migrants, indicating that gender may be an independent determinant of health (Maksimovic 2014; Rask 2016). Other empirical studies have used qualitative methods for data collection (interviews or focus group discussions) and report that both a migrant background and female gender seem to be important determinants of access to health care services, particularly rehabilitation services (Czapka 2016; Schwarz 2015). Migrant‐specific barriers to health care access include language barriers (with resulting communication barriers), lack of knowledge about the health care system in a host country, and culture‐ or religion‐specific barriers (Czapka 2016; Schwarz 2015; Schaeffer 2016). Gender‐specific barriers to health care access are often related to gender roles, such as women's sense of responsibility with regard to child and family care, which can result in a feeling of guilt when using health care services (Schwarz 2015). Other studies also show that female migrants generally report lower self‐perceived health status, but conversely present a healthier lifestyle and higher awareness of healthy living compared to male migrants (Alidu 2017; Igel 2010; Malmusi 2010). Both gender and migration are factors that have received increased attention in relation to their roles as important determinants of health and health literacy (Svensson 2017). However, studies show inconsistencies particularly with regard to the effect size and the direction of a potential gender effect (Schaeffer 2016). Thus, to date it remains unclear how, and in which way, gender affects the health literacy of migrants (Paasche‐Orlow 2005; Pelikan 2013).

In addition, a link can be seen between health literacy and the status of health. Limited health literacy is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A review conducted on the association between health literacy and health outcomes found moderate‐quality evidence that limited health literacy lead to frequent hospitalisation, and difficulties in taking medications appropriately (Berkman 2011). The review also indicated an association between limited health literacy and difficulties in accessing health care services or understanding prescription information (Berkman 2011). Another review researched the association between health literacy and use of health care services focussing on parents' limited health literacy and its effect on their asthmatic children. Factors such as an incomplete high school education and low numeracy skills were associated with parents' limited health literacy, which resulted in limited asthma knowledge and control, difficulties in accessing relevant health information, and overall low self‐efficacy. Consequently, the children of parents who showed limited health literacy had higher rates of hospitalisation and more frequent visits to emergency departments (thus, increased health care utilisation) (Tzeng 2017). Other studies also reported more frequent use of alcohol and tobacco among people with limited health literacy compared to those with a higher level of health literacy (DeWalt 2009; Suka 2015).

Health literacy

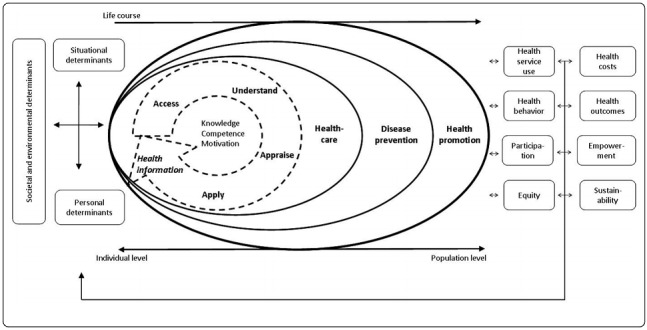

Although there is no universal definition of health literacy, the term is commonly defined as the “knowledge, motivation and competencies of accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health‐related information within the healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion setting, respectively” (Sørensen 2012). This definition of health literacy, and the corresponding integrated model depicting the concept of health literacy, were developed through a systematic review and content analysis of previous definitions and conceptual frameworks of health literacy (Sørensen 2012; Figure 1). According to this definition and its corresponding model, the four steps of health information processing ‐ access, understand, appraise, and apply ‐ are dependent on three vital components, namely possessing the knowledge, motivation and the competence to perform these four steps. In addition, the ability to perform the four steps of health information processing is influenced by personal (e.g. age), situational (e.g. family support), and societal (e.g. culture) determinants. The model indicates that a person should be able to search for and find relevant written or oral health information, find ways to access information, understand and appraise the information found, and, ultimately, to use and apply the information to maintaining or improve health. All steps are considered to be crucial for a person to make informed health‐related decisions (Sørensen 2012). Simultaneously, individual skills and abilities need to match the demands and complexities of the environment (Kickbusch 2013; Parker 2009).

Figure 1.

Integrated model of health literacy (Sørensen 2012)

Thus far, research on health literacy has aimed to assess the level of health literacy across populations, and to identify the main determinants of health literacy. In 2011, a Europe‐wide cross‐sectional population study was conducted in eight countries, including over 8000 participants, using the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS‐EU). The main findings showed that nearly half of the participants (47%) reported limited health literacy (HLS‐EU Consortium 2012). Another study in Germany with 2000 participants that also used the HLS‐EU survey reported limited health literacy in 54% of those surveyed (Schaeffer 2016). It was found that the greatest difficulties among participants with limited health literacy included use of health information to cope with illness or make healthy decisions to prevent illness (Schaeffer 2016). Challenges in navigating the health care system were also reported in relation to limited health literacy (Schaeffer 2016). These findings are especially striking when interpreted with the additional finding that limited health literacy was indicated particularly in migrants. About 20% of Germany’s population are migrants, and research indicates that 71% of migrants in Germany perceive their level of health literacy as limited (IOM 2018; Schaeffer 2016). These findings pose questions about how migrants navigate new health care systems to find and access relevant health information, and how they understand, appraise and use health information to make relevant health‐related decisions in everyday life. People with (perceived) limited health literacy may encounter difficulties navigating health care systems and finding relevant health information. This can increase barriers in communicating with health care providers and using health care services, and may lead to poorer health outcomes (Schaeffer 2016).

Migration

Migration is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that is the reality of every state and millions of people worldwide. Migration is a term for population movement, and is embedded in the social, economic and political areas of life (United Nations 2017).

We will apply the International Organization of Migration (IOM) definition of migration as "the movement of a person or a group of persons, either across an international border, or within a State. It is a population movement, encompassing any kind of movement of people, whatever its length, composition and causes; it includes migration of refugees, displaced persons, economic migrants, and persons moving for other purposes, including family reunification" (IOM 2018).

Recent statistics from the UN International Migration Report (2017) show a steady increase in the movement of people in the past two decades. In 2000, 173 million people moved between or within borders. In 2017, the number reached 258 million migrants. In that year, the largest number of international migrants (moving from one state to another) resided in Asia (80 million), closely followed by Europe (78 million). Among countries with the high numbers of international migrants in 2016 are the USA (50 million), Germany (12 million), and Turkey (3 million). Worldwide, about 48% of migrants were female, and median age of all migrants was 39 years in 2017 (United Nations 2017).

Drivers of migration may include the hope for increased study or work opportunities in another country, as in the case of economic migrants. Movement to another country can result in improved education, income and well‐being (United Nations 2017). Conversely, migration can also be connected to a lack of such opportunities, and reinforce the lack of security. For many people such as refugees and asylum seekers, migration means the escape from a home country due to socio‐economic or political reasons including poverty or persecution (Nuscheler 2013; Schouler‐Ocak 2017). Hence, the reasons for movements are as diverse as the people themselves. Furthermore, migrating people are likely to encounter obstacles upon arrival in the host country, including discrimination, inequalities, and insecurity in different areas of life compared to the native‐born population (United Nations 2017). Asylum seekers are not always immediately recognised as refugees in need of protection, and their legal status in the host country may remain uncertain for many years (IOM 2018). The health care needs of migrant groups can also be highly variable, such as increased physical and mental health care needs for refugees and asylum seekers in particular. In addition, migration poses a great public health challenge to host countries, particularly in terms of providing timely and adequate response to migrants' health care needs, and economic response to provide health care services for migrant groups (Hunter 2016). In a host country, successful migration is achieved when the challenges of connecting diverse people, including different cultures, religions and needs, are met. The interaction of these different cultures in a society is also a vital part of the process of acculturation post‐migration, meaning a person's integration into a new society (Morawa 2014). Acculturation is connected to psychological and social changes that take place when a person tries to learn the language of their host country, and to create social networks as well as integrate cultural and religious aspects, including personal values and morals, and match these to the new society. These challenges are closely related to health and well‐being (Morawa 2014).

Gender

Although there are ongoing discussion on the use of the terms sex and gender, sex typically refers to biological and physiological processes. Gender is widely considered to describe roles, behaviours, identities, and relations (Hammarström 2012). Given the behavioural and relational nature of health literacy, differences between men and women should be addressed as gender differences rather than sex differences (Sandford 1999). Therefore, we will use the term gender to denote results concerning men and women (and if applicable, other genders).

Some literature indicates that certain health risks are more likely to affect women (i.e. sexual violence and abuse, trafficking or pregnancy‐related health risks), while accidents, physical exertion or occupational risks are more likely to affect men (Douki 2007; Llácer 2007; Malmusi 2010; Schouler‐Ocak 2017). The gender‐specific needs that result from these health risks can affect the health information required and how the health information needed will be accessed, processed and translated into health‐promoting behaviour. A relationship between health literacy and gender has been found in a number of empirical studies which report that women typically have slightly better health literacy than men (Christy 2017; Lee 2015;Paasche‐Orlow 2005; Pelikan 2013; van der Heide 2013). Conversely, other studies did not find significant differences between the genders (Jordan 2015; HLS‐EU Consortium 2012; Schaeffer 2016). As a result, consistent and meaningful statements about the relationship between gender and health literacy in the general population are not yet possible. There is also some evidence on the association between gender and health literacy among migrants (Igel 2010; Maksimovic 2014; Morawa 2014; Müller 2017), but findings are mixed and it remains unclear how gender‐specific factors can influence the health literacy of women and men. In addition, the impact of other factors such as culture or religion, on the four steps of health information processing are unclear.

Considering equity in health literacy (PRISMA‐E)

Equity is an aspect of high importance that is not always addressed in systematic reviews (Welch 2015). Health equity is defined as "the absence of avoidable and unfair inequalities in health" (Welch 2012; Whitehead 1992). Inequalities in health can include discrimination or inadequate access to health care services. Reasons behind inequalities include socio‐demographic differences, such as age, sex and gender, or ethnicity (Welch 2015). The integrated model of health literacy draws attention to the importance of health equity at the population level, and highlights how improved health literacy at the individual level will contribute to increased equity and sustainable improvement in public health (Sørensen 2012). We will follow the PRISMA‐E reporting guidelines for systematic reviews to consider equity at every step of our review (Welch 2012; Welch 2015). We will provide a strong rationale on gender and migration as important factors to be considered in health equity when discussing the improvement of health literacy. We will formulate objectives and questions that will enable exploration of gender differences that may contribute to inequalities in health literacy. We will apply an inclusive approach to the study population and ensure inclusion of different groups of migrants. We will consider issues around equity in our synthesis and discussion of findings (Welch 2015). In addition, as a critical part of our methodology, we will use the health literacy model by Sørensen 2012 to look at our findings through an equity lens (Harris 2017; Welch 2015). The integrated model of health literacy will serve as an equity model as it includes gender and ethnicity as personal determinants of health literacy, and culture as a societal and environmental determinant. Thus, migration can be integrated in this model as a personal (i.e. ethnicity), situational (i.e. pre‐, peri‐, and post ‐migration status) or societal and environmental factor (i.e. culture) determining health literacy. Factors such as poor socioeconomic environments and living conditions, access to educational opportunities, and psychological stresses such as chronic work hazards are well examined causal factors leading to health inequalities (Marmot 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Qualitative research aims to explore lived experiences, the way people perceive the world and their surrounding, as well as subjective opinions and views on a specific subject. Ultimately, qualitative research tries to understand behaviour and phenomena that may be difficult to quantify and explain in numbers (Green 2004). Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) is a type of review that synthesises the evidence from qualitative research studies (e.g. studies in which interviews were conducted). A QES does so by collecting and aggregating the evidence from multiple primary qualitative studies. It is current Cochrane policy that a Cochrane QES is linked to a Cochrane effectiveness review that already exists or is being developed concurrently. As specified in the Cochrane Handbook, there are four ways in which a QES can contribute to an effectiveness review: by informing, enhancing, extending or supplementing the evidence (Noyes 2011). This QES will be conducted in parallel to the Cochrane effectiveness review Interventions for improving health literacy in migrants (Baumeister 2018). The effectiveness review will aim to assess interventions for improving health literacy in migrants, and whether female or male participants respond differently to the interventions. This QES will synthesise qualitative evidence from different types of qualitative research studies that try to explore and explain possible gender differences in the health literacy of migrants to supplement the related effectiveness review. The QES will be linked to the effectiveness review by using the conceptual framework of health literacy developed by Sørensen 2012. The synthesised evidence from the QES and the linked effectiveness review may help to validate the applicability of the Sørensen 2012 integrated model of interventions for improving health literacy in migrants, aiming to contribute to a more profound understanding of how interventions can most efficiently be tailored to the needs of female and male migrants. On the basis of the joint results from the two reviews, we will develop a logic model that includes the identified factors that must be taken into account in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions for female and male migrants. The review teams will continuously exchange methodological issues and support each other in the review process.

The synthesised evidence from this QES and the linked effectiveness review may help to inform the development of health literacy interventions in different international health care systems. The synthesised evidence should help to address possible different health care needs of female and male migrants, as many countries have experienced large waves of migration in recent years (United Nations 2017). Migrants' health care needs should be addressed in an appropriate and timely way that is equivalent to the native‐born population of a country (Czapka 2016; Hunter 2016; Nkulu 2016). An appropriate response to migrants' health care needs is dependent on accessibility and availability of health care services and information provided by health care professionals, as well as the proper use of those services and information by health care users. Research on migrant health is highly relevant to gain a better understanding of the specific health care needs of migrants, and how to respond best and most efficiently to those needs. It is also important to identify and address possible gender‐specific differences, and associated factors, that may play a role when effective interventions are to be developed and delivered for the improved access, understanding, appraisal, and use of health information by female and male migrants.

Currently, there is no Cochrane QES on health literacy in migrants. There is one published Cochrane effectiveness review on health literacy focusing on interventions for improving consumers’ online health literacy (Car 2011), and a published Cochrane protocol on interventions improving health literacy in people with kidney disease (Campbell 2016). However, we do not expect overlap among reviews, as health literacy is defined differently, and the phenomena of interest and populations under study differ greatly. Furthermore, gender as a factor potentially influencing health literacy was not examined in these reviews.

Phenomena of interest

Our phenomena of interest in this review are the gender‐specific factors that may be associated with the health literacy of female and male migrants. More specifically, we are interested in the associated factors that are critical to the improvement of a person's health literacy. There may be differences in why and how women and men search for health information, in whether people use available health services, in risk behaviour, in how people experience symptoms and sickness, and in preventive health behaviours (Binder‐Fritz 2014; Schwarz 2015; Schaeffer 2016). We will explore these aspects in female and male migrants through their perceptions and perspectives concerning their own health literacy, and how they may experience and respond differently to health literacy interventions. The interventions for improving health literacy of interest for this review are those addressed by the linked effectiveness review. Interventions may include health‐related educational programmes, or information leaflets adapted to different migrant groups and tailored for specific needs, providing migrants with relevant and understandable or simplified health‐related information. Interventions may target both women and men, or specifically tailored for one gender. We are interested in exploring whether and how gender differences and related factors should be taken into account in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions. We are also interested in how migration‐specific aspects relate to the four steps of health information processing by women and men in a host country. We will explore aspects that are related to knowledge, competencies and motivation to perform these relevant health information processing steps for health literacy.

Objectives

The overall objective of this QES is to explore and explain probable gender differences in the health literacy of migrants. Exploring possible gender differences in the context of migration will supplement the linked effectiveness review by providing a comprehensive understanding of the role that any gender differences may play in the development, delivery, and ultimately, the effectiveness of interventions for improving the health literacy of female and male migrants. This QES has the following specific objectives.

To explore whether gender differences in the health literacy of migrants exist.

To identify factors that may underlie gender differences in the four steps of health information processing (access, understand, appraise and apply).

To explore and explain gender differences potentially found ‐ or not found ‐ in the effectiveness of health literacy interventions assessed by the linked effectiveness review.

To explain ‐ in a third synthesis ‐ to what extent gender and migration‐specific factors may play a role in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions.

Methods

We will follow the methods suggested in the Cochrane Handbook Chapter 20: Qualiative research and Cochrane reviews (Noyes 2011) to conduct this QES and integrate findings from this review with the linked effectiveness review. This QES will supplement the linked effectiveness review by synthesising qualitative evidence that addresses questions on aspects other than effectiveness (Noyes 2011). The QES will supplement the linked effectiveness review by helping to explain its findings particularly regarding possible gender differences in the health literacy of migrants.

Criteria for considering studies for synthesis

The inclusion criteria for study participants and settings listed below are the same as the inclusion criteria of the linked Cochrane effectiveness review to enable integration of the quantitative and qualitative findings in a subsequent synthesis (see "Integration of findings in a subsequent synthesis" in Methods).

Participants

We will include migrants, referring to these people as immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, wandering people, and others who have a direct migration experience (first generation migrants), as defined by the IOM (see Background).

We will include adults aged 18 years or over. We will apply no gender or ethnicity restrictions.

As for the linked effectiveness review, we will exclude studies that provide data only for people from established ethnic minority communities (e.g. Latino Americans in the USA), defined as descendants of migrants who have settled in the respective country at least one generation ago. If data for subgroups, who are explicitly designated as first generation migrants can be extracted, the study will be included. If no clear distinction between the ethnic minority group and the migrant status according to our definition can be made (i.e. when it is not stated which generation of migrants is targeted), the study will be excluded.

Setting

We will include primary qualitative research studies conducted on our phenomena of interest, independent of the country or setting in which they were conducted.

Types of studies

We will consider three types of qualitative research studies. These studies should apply qualitative methods for data collection, such as individual interviews, focus group discussions, participant observations, narrative stories, or case studies (Green 2004). Furthermore, the studies should use qualitative methods for the analysis, interpretation, and presentation of findings. These can include thematic analysis, qualitative content analysis or grounded theory (Green 2004).

Qualitative trial‐sibling studies

We will search for and include qualitative trial‐sibling studies directly related to the studies and interventions included in the linked effectiveness review (Baumeister 2018). Qualitative trial‐sibling studies are studies that were conducted alongside complex intervention studies to provide explanations and help to understand these complex interventions (Noyes 2016).

Unrelated qualitative studies

Because trial‐sibling studies are rather uncommon (Noyes 2016), we will also include unrelated qualitative studies. Such studies are not directly related to the interventions included in the linked effectiveness review (Baumeister 2018), but explore similar interventions in a similar context (Noyes 2016).

Stand‐alone qualitative studies

If trial‐sibling studies and unrelated qualitative studies are very few (thus, unable to address or answer our objectives), or if they are unavailable, we will also include stand‐alone qualitative studies that aim to explore and explain possible gender differences in the health literacy of migrants.

We will also include primary studies using mixed methods approaches (quantitative and qualitative research methods) for data collection, and extract results from the qualitative analyses only. We will exclude studies that did not perform a qualitative analysis of findings.

Criteria for inclusion of unrelated and stand‐alone qualitative studies

To ensure comparability and integration of results between the reviews, unrelated and stand‐alone qualitative studies on health literacy of migrants should have sufficient contextual similarities to the interventions included in the linked effectiveness review by fulfilling the following criteria.

Health literacy explored either as a whole concept, or one of its processing steps, which have to be the same steps examined in the linked effectiveness review.

Same country or region of origin (i.e. middle‐eastern states, Balkan states) as in the studies of the linked effectiveness review.

Same host countries as those included in the studies of the linked effectiveness review.

Same migrant groups (i.e. refugees, asylum seekers) as those included in the studies of the linked effectiveness review.

Similar age range of participants as those included in the linked effectiveness review.

Similar time period of study conduct.

Types of interventions included in the effectiveness review

We will search for trial‐sibling studies of the interventions included in the linked effectiveness review (Baumeister 2018). Interventions that will be included in the effectiveness review can be interventions aiming to:

improve health literacy in different settings (e.g. group‐based education programs for pregnant women on post‐partum care in an immigrant community);

improve health literacy in hard‐to‐reach groups (e.g. telephone interventions to improve patients' engagement in disease management);

improve health professionals' communication skills in consulting patients with limited literacy skills (e.g. teach‐back training, if the effect was measured in migrants);

improve access to health information (e.g. access to telemedicine in rural areas);

improve knowledge or understanding of information about health, disease or treatment (e.g. mitigate effects of limited language proficiency through the provision of information in different languages);

affect the appraisal of health information (e.g. by individually tailoring the information provided); and

improve the use of health information (e.g. monitoring treatment adherence for antibiotics).

Types of outcome measures

Phenomena of interest: We will include studies in which the phenomenon of interest is a description and interpretation of the perceptions and perspectives of women and men concerning their own health literacy, including their description of how they experience health literacy interventions. These descriptions and interpretations shall help identify factors related to gender and migration and that may be associated with health literacy.

Search methods for identification of studies

To identify qualitative trial‐sibling studies directly related to the interventions of the linked effectiveness review, we will first search for indication of such in the publications of the intervention studies included in the effectiveness review. We will search methods and references to identify associated qualitative studies. In cases of uncertainty, we will try to contact the principal trial investigator to ask about the existence of such studies.

Electronic searches

A search strategy specific to this QES (independent of the search strategy for the linked effectiveness review, Baumeister 2018), will be developed by an Information Specialist in consultation with the review authors. The search strategy will contain a study filter for qualitative studies, and will search for qualitative trial‐sibling studies, unrelated qualitative studies as well as stand‐alone qualitative studies. No date, language or geographic restrictions will be applied to the search.

We will search the following electronic databases for eligible studies.

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (OvidSP) (Appendix 1).

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (Appendix 2).

PsycINFO (EbscoHOST) (Appendix 3).

Additional searches

Citation pearl searching

We will search for qualitative trial‐sibling studies of trials included in the linked effectiveness review by conducting a citation pearl search. Citation pearl search means taking the relevant articles from the linked effectiveness review and conducting a separate search using keywords, authors' names, and key terms from titles and abstracts of the relevant articles to identify associated or similar articles.

Hand searching

We will search the reference list of included studies in the linked effectiveness review to identify trial‐sibling studies (snowballing method). We will also search the reference list of included studies of this review for additional relevant studies to find other relevant primary qualitative studies. Furthermore, we will search for meta‐syntheses that address health literacy (either as a general concept, or at least one of its four processing steps) in relation to migration and search their reference lists to identify relevant studies that fit our inclusion criteria.

Grey literature

Should we conduct a broad synthesis of qualitative studies, we will also search for grey literature that is not indexed in the listed databases. Our reasoning is that while we expect to find a fair body of research on health‐related experiences of migrants, not all will have been included in bibliographic databases. Various international/national organisations and institutions conduct qualitative research, particularly with newly arrived refugees on their health status and access to health care in the host country. For example, the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin conducted a study on female refugees, supported by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), using a mixed methods approach. For the qualitative part of this study, focus group discussions were conducted with female refugees from several countries (Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Somalia, and Syria) on their access to and use of (two of four health information processing steps) mental health care within the German health care system (Schouler‐Ocak 2017). This is an example of a report not listed in bibliographic databases that may have relevant findings for our review. Hence, we expect grey literature to be an additional pool of evidence. We will hand search reports and official web sites of different organisations and institutions for relevant reports (Thomas 2008).

We will look for grey literature by searching:

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu) and the Grey Literature Report (www.greylit.org);

publication lists of relevant organisations known to us, including (but not limited to) BAMF, WHO, and IOM;

reference lists of included studies to identify relevant reports;

checking key articles on Google Scholar, to identify whether they were cited by other relevant articles; and

contacting experts for additional relevant articles.

Trials registries

We will search the following trials registries to find studies that use a mixed‐method approach:

EU clinical trials register;

ClinicalTrials.gov; and

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Conference proceedings

We will search conference proceedings of the following conferences:

International Conference for Migration and Development;

First World Congress on Migration, Ethnicity, Race and Health (MERH);

European Public Health Conference (EUPH); and

The Migration Conference.

Data collection and synthesis

Selection of studies

We will conduct the search in all listed databases, collate the results into one database, and remove duplicates. Screening and selection of studies will be done by two review authors (AA, DC) independently in Covidence. If there are discrepancies, a third review author (AB) will be consulted. At the first step, titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search will be screened to identify potentially eligible studies. At the second step, the full‐text of potentially eligible studies will be obtained, and the predefined inclusion criteria will be applied to determine inclusion of studies. Screening and selection of studies, and documentation of results will follow the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009). We will also create a 'Characteristics of included studies’ table (Higgins 2011).

Purposive sampling of studies

We will consider purposive sampling for this QES, depending on the number of included studies (Robinson 2014). Because primary qualitative research studies often include smaller sample sizes of participants, it is recommended using a smaller sample of studies in a QES as well (Booth 2016; Green 2004; Thomas 2008). Previous systematic reviews of qualitative studies have applied purposive sampling because it is presumed that synthesising qualitative evidence from a large number of studies can become too complex, with the risk of losing insight and being unable to track patterns in review findings (Ames 2017; Booth 2016; Campbell 2011). The main purpose of synthesising qualitative evidence is to identify patterns and agreements among concepts found in the studies, which is independent from the number of studies that cover one concept (Thomas 2008). It is suggested to not include more than 40 studies in the sample to be analysed to maintain a manageable selection of studies and prevent apparent patterns from being obscured during the synthesis of findings (Booth 2016; Campbell 2011).

We will sample studies based on the following criteria.

Studies must explore health literacy as the fundamental concept.

The migrant background of the included population should be clearly stated, including that they are first generation migrants.

Results must be clearly assignable to women or men.

A rigorous and rich analysis of the results has been performed.

Results can be assigned to educational level, as education is an important determinant of health literacy.

We will rank studies according to fulfilment of these criteria and demonstrate their eligibility in a table. We will present all relevant, but not included studies, as an additional table.

Data extraction

We will develop a data extraction form adapted to the methodology of the included studies, containing all relevant methodological and contextual information (Booth 2016; Flemming 2017; Noyes 2017a). Data will be extracted independently by two review authors (AA, DC) from the sampled studies. Extracted data will be cross‐checked by the authors to ensure that relevant information was not missed, and that the authors agree on the findings. Should discrepancies occur during the process, a third review author (AB) will be consulted. If required, we will contact study authors for additional information.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two review authors (AA, DC) will independently assess the methodological quality of included studies. A consensus on the quality of each study will be reached by discussion between the review authors following their independent assessments. In case of disagreement, a third review author (AB) will be consulted.

We will use the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) assessment tool because it has been used in other Cochrane syntheses of qualitative evidence, and by the World Health Organization (WHO) for guideline development (Ames 2017; Bohren 2016; Booth 2016; CASP 2017; Flemming 2017; Houghton 2017; Noyes 2017a). We will use the adapted CASP Qualitative Checklist for qualitative reviews, which includes the following 10 questions.

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

Is there a clear statement of findings?

How valuable is the research?

The tool suggests to record "yes", "no" or "can't tell" as answers to each question. The assessment is based on a given set of criteria for each question. The full checklist, including all questions and criteria, can be viewed and downloaded from the official CASP web page. As for previous Cochrane qualitative evidence syntheses, we will first assess the feasibility of the tool on a small number of studies (Ames 2017). In case it is not applicable, we will either adapt the tool, or search for another tool and report this in the "Differences between protocol and review" section of the QES.

Grading the evidence

We will apply the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual) approach to help us assess how much confidence to place in individual review findings. A review finding is a specific output from the synthesis that describes the phenomenon of interest, or an aspect of the phenomenon (Lewin 2015). CERQual is derived from the GRADE for intervention reviews, and was developed by a subgroup of the GRADE Working Group (Lewin 2015). GRADE CERQual provides a transparent and structured method for assessing confidence in qualitative syntheses findings. The tool focuses on four components that assess how much confidence to place in an individual finding. These components include:

Methodological limitations of the included studies.

Relevance of the evidence from included studies to the review question(s).

Coherence (finding patterns) of the review finding.

Richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding (Lewin 2015).

The confidence in a review finding is graded at one of four levels:

High confidence: it is highly likely that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Moderate confidence: it is likely that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Low confidence: it is possible that the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest.

Very low confidence: it is not clear whether the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest (Lewin 2015)

We will prepare a 'CERQual Evidence Profile' for each finding, which will include information on all CERQual component assessments for each finding. We will then prepare a 'Summary of qualitative findings' (SoQF) table to present key findings, including our overall CERQual assessment for each finding. We will follow the methodological guidance on creating evidence profiles and SoQF tables provided by the CERQual working group, and as illustrated and described in Lewin 2018.

Data synthesis

Framework approach

We will use the framework approach to synthesise evidence for this QES. A framework approach enables researchers to structure and conceptualise qualitative findings a priori using the framework (Carroll 2011; Gale 2013; Thomas 2008). The framework method has been used increasingly in multidisciplinary health research when qualitative evidence is synthesised (Gale 2013). Using a framework enables embedding qualitative findings into an existing theoretical framework for the phenomenon of interest. We expect this approach to be helpful to handle large amounts of data and conduct a rigorous synthesis (Thomas 2008). Although this is a rather deductive method, it enables researchers to inductively identify new concepts and topics, which can be incorporated into the framework, and thereby suggest the adaptation of the framework based on these findings (Thomas 2008). Furthermore, framework analysis assists with developing policy‐ and practice‐oriented findings (Green 2004).

We will use the health literacy model developed by Sørensen 2012 as the framework to structure and conceptualise our findings according to the four health information processing steps (access, understanding, appraisal, and use (see Background)). Through the descriptions and interpretations in the primary studies we will develop themes and categories that represent the factors and aspects that can be associated with gender and migration.

We will also use the framework method in the third synthesis to bring together the results of this QES and the linked effectiveness review (Baumeister 2018). The aim of integrating results from both reviews is to develop a logic model that includes the identified gender and migration‐specific factors that should be considered in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions for female and male migrants (see Integration of findings in a subsequent synthesis in Methods).

Supplementing the linked Cochrane effectiveness review with synthesised qualitative findings

The QES review is linked to the Cochrane effectiveness review Interventions for improving health literacy in migrants (Baumeister 2018). The effectiveness review aims to assess interventions for improving health literacy in migrants. Baumeister 2018 also aims to assess whether female or male participants may respond differently to the interventions. To supplement the linked effectiveness review, this QES will synthesise the evidence from primary qualitative studies that try to explore and explain possible gender differences in the health literacy of migrants. It will also attempt to identify factors associated with gender and migration that may play a role in the design, delivery, and effectiveness of health literacy interventions for female and male migrants. The reviews will be conducted in parallel and by the same team of authors. Hence, the review authors will be working in constant exchange with each other regarding the content and methodology of both reviews, and will support each other in the review process.

Integration of findings in a subsequent synthesis

The findings from the reviews will be integrated in a subsequent synthesis, which will help to understand whether, and how, gender differences should possibly be taken into account in the development and delivery of interventions for improving the health literacy of female and male migrants (Harden 2017; Noyes 2017). Whether or not the effectiveness review identifies gender as an important factor influencing the effectiveness of health literacy interventions, the QES will provide a broader, in‐depth explanation to help to understand how and why these interventions have their effects, and to help to explain how gender and associated factors might be taken into account in the design and delivery of health literacy interventions. If no differential effect of gender on the effects of health literacy interventions is found, the QES will also help to identify whether there was a failure of theory, or failure of implementation, in the effectiveness review. Hence, the synthesised evidence from this QES and the linked effectiveness review may ultimately help to validate the applicability of the integrated model of health literacy (Sørensen 2012). On the basis of the joint results from the two reviews, we will develop a logic model that includes the identified factors that should be considered in the development and delivery of health literacy interventions for female and male migrants.

Involving consumers

This review is part of an overarching project, which aims to examine gender‐specific aspects of health literacy in migrants by applying a mixed methods approach. The project is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany.

The involvement of consumers is important to obtain a better understanding of the performance and effectiveness of health literacy interventions, particularly how they reach consumers. We will involve consumers by conducting additional qualitative research to support our review, and particularly the interpretation of our findings. We will conduct gender‐separate focus group discussions with female and male migrants, in which we will present and discuss our findings to reflect on our analysis. The protocol and review will receive feedback from at least one consumer referee in addition to a health professional as part of Cochrane Consumers and Communication’s standard editorial process

In a final symposium for this project, we aim to present our primary and secondary research findings to experts from political and health care contexts, and discuss the impact and implications of our primary and secondary findings for health care decision‐making at the political level, particularly in Germany (Noyes 2017). We expect our findings to contribute to relevant political decisions for the health care of migrants in Germany, and to also provide implications for other health care systems.

Researchers' reflexivity

Reflexivity is an approach of addressing potential biases in qualitative research by reflecting upon one's position within the research process (Green 2004) .To address researchers' reflexivity, we will include this concept in the discussion of the review, and we will reflect upon how our professional and personal backgrounds, as well as our prior understanding of the phenomena of interest, may have affected the collection and synthesis of findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrew Booth (Co‐Convenor, Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group) and Anne Parkhill (Information Specialist with Cochrane Consumers and Communication) for commenting on and helping to develop the search strategy.

We acknowledge the assistance of Bronwen Merner (Managing Editor) who provided guidance during title registration; Sophie Hill and Rebecca Ryan (Co‐ordinating Editors); and Nancy Santesso (Editor) from the Cochrane Consumers and Communication review group who reviewed and commented on the drafts and helped to finalise the protocol.

We acknowledge consumer peer reviewer Jeanine Hourani, and clinical peer reviewer Elisha Riggs, who both reviewed and commented on the protocol.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

| 1 | "TRANSIENTS AND MIGRANTS"/ |

| 2 | migrant*.tw,kf,ot. |

| 3 | (migration* adj3 (background* or human*)).tw,kf,ot. |

| 4 | exp "EMIGRANTS AND IMMIGRANTS"/ |

| 5 | UNDOCUMENTED IMMIGRANTS/ |

| 6 | "EMIGRATION AND IMMIGRATION"/ |

| 7 | (immigrant* or immgrat*).tw,kf,ot. |

| 8 | (emigrant* or emigrat*).tw,kf,ot. |

| 9 | (minorit* adj3 (population* or group*)).tw,kf,ot. |

| 10 | (ethnic* adj3 (population* or group* or patient* or background* or specific* or minorit* or identit*)).tw,kf,ot. |

| 11 | (displaced and (people or person$1)).tw. |

| 12 | VULNERABLE POPULATIONS/ |

| 13 | REFUGEES/ |

| 14 | (foreigner* or asylum* or refugee* or undocumented or non‐native or nonnative or foreign‐born or foreignborn).tw,kf,ot. |

| 15 | (cultur* adj5 (differences* or cross* or background*)).tw,kf,ot. |

| 16 | (border* and crossing).tw. |

| 17 | ((culturall* or linguisticall*) adj3 (diverse* or patient* or parent* or communit* or background* or student* or wom?n or famil*)).tw,kf,ot. |

| 18 | or/1‐17 |

| 19 | ACCESS TO INFORMATION/ |

| 20 | ((access or gain access or obtain or seek out or find or indentify) adj5 (information* or health*)).tw. |

| 21 | COMPREHENSION/ |

| 22 | (understand or comprehend or comprehension).tw. |

| 23 | (appraise or evaluate or process or interpret or assess).tw. |

| 24 | assessment of information.tw. |

| 25 | (apply or decide).tw. |

| 26 | (use* adj3 (information* or health)).tw. |

| 27 | (capacit* adj4 health).tw. |

| 28 | accept*.tw,kf,ot. |

| 29 | DECISION MAKING/ |

| 30 | ((make or making or made or take) adj4 decision*).tw. |

| 31 | ("behavior change" or "behaviour change").tw,kf,ot. |

| 32 | (acting or act or action).tw. |

| 33 | judge*.tw. |

| 34 | or/19‐33 |

| 35 | exp CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION/ or INFORMATION LITERACY/ |

| 36 | HEALTH LITERACY/ |

| 37 | (information* adj3 health*).tw. |

| 38 | (health* adj3 (literac* or servic* or decision* or concept* or competenc* or system* or knowledg* or status or level* or needs or insurance or status or behaviour*)).tw. |

| 39 | or/35‐38 |

| 40 | HEALTH EDUCATION/ or EDUCATIONAL STATUS/ |

| 41 | (health* adj3 education*).tw. |

| 42 | HEALTH SERVICES ACCESSIBILITY/sn [Statistics & Numerical Data] |

| 43 | or/40‐42 |

| 44 | 34 and (39 or 43) |

| 45 | health litera$2.af. |

| 46 | medical literacy.af. |

| 47 | (health and literacy).ti. |

| 48 | (functional and health and literacy).tw. |

| 49 | low‐litera$2.ti. |

| 50 | litera$2.ti. |

| 51 | illitera$2.ti. |

| 52 | READING/ |

| 53 | COMPREHENSION/ |

| 54 | *HEALTH PROMOTION/ |

| 55 | *HEALTH EDUCATION/ |

| 56 | *PATIENT EDUCATION/ |

| 57 | *COMMUNICATION BARRIERS/ |

| 58 | *COMMUNICATION/ |

| 59 | *HEALTH KNOWLEDGE,ATTITUDES,PRACTICE/ |

| 60 | *ATTITUDE TO HEALTH/ |

| 61 | *COMPREHENSION/ and *EDUCATIONAL STATUS/ |

| 62 | (family and literacy).ti. |

| 63 | (drug labeling.af. or PRESCRIPTIONS, DRUG/) and comprehension.af. |

| 64 | ((cancer or diabetes or genetics) and (literacy or comprehension)).ti. |

| 65 | (adult and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy)).af. |

| 66 | (limited and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy)).af. |

| 67 | (patient$1 and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy)).af. |

| 68 | (patient$1 and (comprehension or understanding)).ti. |

| 69 | or/45‐53 |

| 70 | or/54‐68 |

| 71 | 69 and 70 |

| 72 | 18 and 44 |

| 73 | 18 and 71 |

| 74 | 18 and (44 or 71) |

| 75 | QUALITATIVE RESEARCH/ or INTERVIEWS AS TOPIC/ or FOCUS GROUPS/ or NARRATION/ or "QUESTIONNAIRES"/ or SELF REPORT/ or exp ATTITUDES/ or exp TAPE RECORDING/ or NURSING METHODOLOGY RESEARCH/ |

| 76 | (qualitative or ethno$ or emic or etic or phenomenolog$ or hermeneutic$ or heidegger$ or Husserl$ or colaizzi$ or giorgi$ or glaser$ or strauss$ or van kaam$ or van manen$).mp. |

| 77 | (constant compar$ or focus group$ or grounded theory or narrative analysis or lived experience$ or life experience$ or theoretical sampl$ or purposive sampl$ or ricoeur$ or speigelberg$ or merleau$ or maximum variation or snowball$ or field stud$ or field note$ or fieldnote$ or field record$ or content analy$ or unstructured categor$ or structured categor$ or action research or audiorecord$ or taperecord$ or videorecord$ or videotap$ or digitalrecord$ or digitaltap$).mp. |

| 78 | (thematic$ adj3 analy$).mp. |

| 79 | ((participant$ or nonparticipant$ or non‐participant$ or non participant$) adj3 observ$).mp. |

| 80 | ((audio or tape or tapes or taping or video$ or digital$) adj5 (record$ or interview$)).mp. |

| 81 | (findings or interview).tw. |

| 82 | or/75‐81 |

| 83 | 74 and 82 |

| 84 | exp ANIMALS/ not HUMANS/ |

| 85 | review.pt. |

| 86 | meta analysis.pt. |

| 87 | news.pt. |

| 88 | comment.pt. |

| 89 | editorial.pt. |

| 90 | cochrane database of systematic reviews.jn. |

| 91 | comment on.cm. |

| 92 | (systematic review or literature review).ti. |

| 93 | or/84‐92 |

| 94 | 83 not 93 |

Key: tw: text word, kf: keyword heading word, ot: original title, ti: title, pt: publication type, ab: abstract, fs: floating subheading, hw: subject heading word, nm: name of substance word, sh: MeSH subject heading, jn: journal name

Appendix 2. CINAHL search strategy

S75 S71 AND S74

S74 S72 OR S73

S73 TI ( (qualitative or group W0 discussion* or focus W0 group* or themes) ) OR AB ( (qualitative or group W0 discussion* or focus W0 group* or themes) )

S72 (MH "QUALITATIVE STUDIES+")

S71 S18 and (S44 or S70)

S70 S68 AND S69

S69 S54 OR S55 OR S56 OR S57 OR S58 OR S59 OR S60 OR S61 OR S62 OR S63 OR S64 OR S65 OR S66 OR S67

S68 S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 or S49 or S50 or S51 or S52 or S53

S67 TI (patient* and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S66 MW (patient* and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S65 TI (limited and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S64 MJ (adult and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S63 TI (cancer or diabetes or genetics) and (literacy or comprehension)

S62 TX ( (drug labeling or prescriptions, drug) and comprehension )

S61 TI family and literacy

S60 (MM "EDUCATIONAL STATUS") AND TX comprehension

S59 (MM "ATTITUDE TO HEALTH")

S58 (MM "HEALTH KNOWLEDGE")

S57 (MM "COMMUNICATION")

S56 (MM "COMMUNICATION BARRIERS")

S55 (MM "HEALTH EDUCATION")

S54 (MM "HEALTH PROMOTION")

S53 TX comprehension

S52 MH READING

S51 TI illitera*

S50 TI litera*

S49 TI low‐litera*

S48 TX functional and health and literacy

S47 TI health and literacy

S46 TX medical literacy

S45 TX health litera*

S44 S34 and (S39 or S43)

S43 S40 or S41 or S42

S42 (MH "HEALTH SERVICES ACCESSIBILITY")

S41 TX health* N3 education*

S40 (MH "HEALTH EDUCATION") OR (MH "EDUCATIONAL STATUS")

S39 S35 or S36 or S37 or S38

S38 TX health* N3 (literac* or servic* or decision* or concept* or competenc* or system* or knowledg* or status or level* or needs or insurance or status or behaviour*)

S37 TX information* N3 health*

S36 (MH "HEALTH LITERACY")

S35 (MH "CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION") OR (MH "Information Literacy")

S34 S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33

S33 TX judge*

S32 TX acting or act or action

S31 TX "behavior change" or "behaviour change"

S30 TX ((make or making or made or take) N4 decision*)

S29 (MH "DECISION MAKING, FAMILY") OR (MH "DECISION MAKING, PATIENT")

S28 TX accept*

S27 TX capacit* N4 health

S26 TX use* N3 (information* or health)

S25 TX apply or decide

S24 TX assessment of information

S23 TX appraise or evaluate or process or interpret or assess

S22 TX understand or comprehend

S21 TX comprehension

S20 TX (access or gain access or obtain or seek out or find or identify) N5 (information* or health*)

S19 (MH "ACCESS TO INFORMATION")

S18 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17

S17 TX (culturall* or linguisticall*) N3 (diverse* or patient* or parent* or communit* or background* or student* or woman or women or famil*)

S16 TX border* and crossing

S15 TX cultur* N5 (differences* or cross* or background*)

S14 TX (foreigner* or asylum* or refugee* or undocumented or non‐native or nonnative or foreign‐born or foreignborn)

S13 (MH "REFUGEES")

S12 (MH "POPULATION") AND (MH "VULNERABILITY")

S11 TX (displaced and (people or person*))

S10 TX ethnic* N3 (population* or group* or patient* or background* or specific* or minorit* or identit*)

S9 TX minorit* N3 (population* or group*)

S8 TX emigrant* OR TX emigrat*

S7 TX immigrant* OR TX immgrat*

S6 (MH "EMIGRATION AND IMMIGRATION")

S5 MH "IMMIGRANTS, ILLEGAL"

S4 MH "EMIGRANTS AND IMMIGRANTS"

S3 TX migration* N3 (background* or human*)

S2 TX migrant*

S1 MH "TRANSIENTS AND MIGRANTS"

key: TX: all text, TI: title, MH: CINAHL exact subject heading, MM: CINAHL exact major subject headings, MJ: CINAHL word in major subject heading, MW: CINAHL heading word

Appendix 3. PsycINFO search strategy

S76 S72 AND S75

S75 S73 OR S74

S74 DE "QUALITATIVE RESEARCH"

S73 TX qualitative OR TX themes

S72 S18 and (S44 or S71)

S71 S69 and S70

S70 S54 or S55 or S56 or S57 or S58 or S59 or S60 or S61 or S62 or S63 or S64 or S65 or S66 or S67 or S68

S69 S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 or S49 or S50 or S51 or S52 or S53

S68 TI (patient* and (comprehension or understanding))

S67 SU (patient* and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S66 SU (limited and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S65 SU (adult and (educational status or (educational and status) or literacy))

S64 TI (cancer or diabetes or genetics) and (literacy or comprehension)

S63 SU (drug labeling or PRESCRIPTIONS, DRUGS) and comprehension

S62 TX family and literacy

S61 MA COMPREHENSION AND MA EDUCATIONAL STATUS

S60 MA "HEALTH PERSONNEL ATTITUDES"

S59 DE "HEALTH ATTITUDES"

S58 DE "HEALTH KNOWLEDGE" OR DE "HEALTH BEHAVIOR"

S57 DE COMMUNICATION

S56 DE COMMUNICATION BARRIERS

S55 DE HEALTH EDUCATION

S54 DE HEALTH PROMOTION

S53 DE COMPREHENSION

S52 DE READING

S51 TX illitera*

S50 TX literac*

S49 TX low‐litera*

S48 TX functional and health and literacy

S47 TX health and literacy

S46 TX medical literacy

S45 TX health litera*

S44 S34 and (S39 or S43)

S43 S40 or S41 or S42

S42 MA HEALTH SERVICES ACCESSIBILITY

S41 TX health* N3 education*

S40 DE HEALTH EDUCATION OR (DE EDUCATION OR DE STATUS)

S39 S35 or S36 or S37 or S38

S38 TX health* N3 (literac* or servic* or decision* or concept* or competenc* or system* or knowledg* or status or level* or needs or insurance or status or behaviour*)

S37 TX information* N3 health*

S36 DE HEALTH LITERACY

S35 MA CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION OR DE INFORMATION LITERACY

S34 S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33

S33 TX judge*

S32 TX acting or act or action

S31 TX "behavior change" or "behaviour change"

S30 TX ((make or making or made or take) N4 decision*)

S29 DE DECISION MAKING

S28 TX accept*

S27 TX capacit* N4 health

S26 TX use* N3 (information* or health)

S25 TX apply or decide

S24 TX assessment of information

S23 TX appraise or evaluate or process or interpret or assess

S22 TX (understand or comprehend or comprehension)

S21 DE COMPREHENSION

S20 TX (access or gain access or obtain or seek out or find or indentify) N5 (information* or health*)

S19 MA "ACCESS TO INFORMATION"

S18 S1 or S2 or S3 Or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17

S17 TX (culturall* or linguisticall*) N3 (diverse* or patient* or parent* or communit* or background* or student* or woman or women or famil*)

S16 TX border* and crossing

S15 TX cultur* N3 (differences* or cross* or background*)

S14 TX (foreigner* or asylum* or refugee* or undocumented or non‐native or nonnative or foreign‐born or foreignborn)

S13 DE REFUGEES

S12 MA VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

S11 TX (displaced and (people or person*))

S10 TX ethnic* N2 (population* or group* or patient* or background* or specific* or minorit* or identit*)

S9 TX minorit* N2 (population* or group*)

S8 TX emigrant* OR TX emigrat*

S7 TX immigrant* OR TX immgrat*

S6 DE IMMIGRATION

S5 DE HUMAN MIGRATION

S4 MA "EMIGRANTS AND IMMIGRANTS"

S3 TX migration* N3 (background* or human*)

S2 TX migrant*

S1 MA "TRANSIENTS AND MIGRANTS"

Key: TX: all text, TI: title, DE: subject (exact), SU: subjects, MA: MeSH subject heading

Contributions of authors

Angela Aldin developed and wrote the protocol.

Digo Chakraverty proofread and commented on the draft.

Annika Baumeister assisted in developing the protocol.

Ina Monsef developed the search strategies.

Jane Noyes provided methodological guidance during title registration and protocol development.

Tina Jakob proofread and commented on the draft.

Ümran Sema Seven provided expertise on migration research.

Görkem Anapa provided expertise on migration research.

Elke Kalbe proofread and commented on the draft.

Christiane Woopen proofread and commented on the draft.

Nicole Skoetz proofread and commented on the draft.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany.

This review is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 01GL1723.

Declarations of interest

Angela Aldin: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Digo Chakraverty: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Annika Baumeister: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Ina Monsef: None known.

Jane Noyes: None known.

Tina Jakob: None known.

Ümran Sema Seven: None known.

Görkem Anapa: None known.

Elke Kalbe: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Christiane Woopen: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Nicole Skoetz: Award of the grant by Federal Ministry of Education and Research for the University Hospital of Cologne to perform this systematic review does not lead to a conflict of interest.

Notes

This protocol was developed in parallel to the protocol of the linked Cochrane effectiveness review (Baumeister 2018), and by continuous exchange between Angela Aldin (first author of this review) and Annika Baumeister (first author of the linked effectiveness review).

New

References

Additional references

- Alidu L, Grunfeld EA. Gender differences in beliefs about health: a comparative qualitative study with Ghanaian and Indian migrants living in the United Kingdom. BMC Psychology 2017;5(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames HM, Glenton C, Lewin S. Parents' and informal caregivers' views and experiences of communication about routine childhood vaccination: a synthesis of qualitative evidence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011787.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister A, Aldin A, Chakraverty D, Monsef I, Jakob T, Seven ÜS, et al. Interventions for improving health literacy in individuals with a migrant background. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine 2011;155(2):97‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder‐Fritz C, Rieder A. Gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity in the context of health and migration [Zur Verflechtung von Geschlecht, sozioökonomischem Status und Ethnizität im Kontext von Gesundheit und Migration]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt ‐ Gesundheitsforschung ‐ Gesundheitsschutz 2014;57(9):1031‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohren MA, Munthe‐Kaas H, Berger BO, Allanson EE, Tunçalp Ö. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012449] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A. Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Systematic Reviews 2016;5:74. [DOI: 10.1186/s13643-016-0249-x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker‐White G, Britten N, Pill R, et al. Evaluating meta‐ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment 2011;15(43):1‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ZC, Stevenson JK, McCaffery KJ, Jansen J, Campbell KL, Lee VW, et al. Interventions for improving health literacy in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012026] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Car J, Lang B, Colledge A, Ung C, Majeed A. Interventions for enhancing consumers' online health literacy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007092.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of "best fit" framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2011;11(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Apparisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative checklist. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf (accessed 21 January 2019).

- Christy SM, Gwede CK, Sutton SK, Chavarria E, Davis SN, Abdulla R, et al. Health literacy among medically underserved: the role of demographic factors, social influence, and religious beliefs. Journal of Health Communication 2017;22(11):923‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence. Version accessed 4 March 2019. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation.

- Czapka EA, Sagbakken M. "Where to find those doctors?" A qualitative study on barriers and facilitators in access to and utilization of health care services by Polish migrants in Norway. BMC Health Services Research 2016;16(1):460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Hink A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Pediatrics 2009;124(Suppl 3):S265‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douki S, Zineb SB, Nacef F, Halbreich U. Women's mental health in the Muslim world: cultural, religious, and social issues. Journal of Affective Disorders 2007;102(1‐3):177‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;97:79‐85. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.022] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2013;13(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London (UK): Sage Publications Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarström A, Annandale E. A conceptual muddle: an empirical analysis of the use of ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in ‘gender‐specific medicine’ journals. PloS One 2012;7(4):e34193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper 5: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;97:70‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.11.029] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, Hannes K, Harden A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper 6: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;97:39‐48. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.10.023] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- HLS‐EU Consortium. Comparative Report of health literacy in eight EU member states. The European health literacy survey HLS‐EU. http://ec.europa.eu/chafea/documents/news/Comparative_report_on_health_literacy_in_eight_EU_member_states.pdf (accessed 11 October 2018).

- Houghton C, Dowling M, Meskell P, Hunter A, Gardner H, Conway A, et al. Factors that impact on recruitment to randomised trials in health care: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.MR000045] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter P. The refugee crisis challenges national health care systems: Countries accepting large numbers of refugees are struggling to meet their health care needs, which range from infectious to chronic diseases to mental illnesses. European Molecular Biology Organization Reports 2016;17(4):492‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igel U, Brahler E, Grande G. The influence of perceived discrimination on health in migrants. Psychiatrische Praxis 2010;37(4):183‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. Key migration terms. International Organization for Migration 2018. https://www.iom.int/key‐migration‐terms (accessed 1 April 2018).

- Jordan S, Hoebel J. Health literacy of adults in Germany [Gesundheitskompetenz von Erwachsenen in Deutschland]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt ‐ Gesundheitsforschung ‐ Gesundheitsschutz 2015;58(9):942‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I, Pelikan J, Apfel F, Tsouros A. Health literacy: The solid facts. World Health Organization. Regional office for Europe. euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/190655/e96854.pdf (accessed 21 January 2019).

- Lee HY, Lee J, Kim NK. Gender differences in health literacy among Korean adults: do women have a higher level of health literacy than men?. American Journal of Men's Health 2015;9(5):370‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe‐Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE‐CERQual). PLoS Medicine 2015;12:e1001895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, Munthe‐Kaas H, Glenton C, Colvin CJ, et al. Applying GRADE‐CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings‐paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implementation Science 2018;13(Suppl 1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llácer A, Zunzunegui MV, Amo J, Mazarrasa L, Bolůmar F. The contribution of a gender perspective to the understanding of migrants' health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2007;61(Suppl 2):ii4‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimovic S, Ziegenbein M, Graef‐Calliess IT, Machleidt W, Sieberer M. Gender‐specific differences relating to depressiveness in 1st and 2nd generation migrants: results of a cross‐sectional study amongst employees of a university hospital [Geschlechtsspezifische Unterschiede bezüglich Depressivität bei Migranten der ersten und zweiten Generation: Ergebnisse einer Querschnittsuntersuchung an Beschäftigten einer Universitätsklinik]. Fortschritte der Neurologie Psychiatrie 2014;82(10):579‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmusi D, Borrell C, Benach J. Migration‐related health inequalities: showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Social Science and Medicine 2010;71(9):1610‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009;151:264‐9, w64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawa E, Erim Y. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among Turkish immigrants in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2014;11(9):9503‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MJ, Koch E. Gender differences in stressors related to migration and acculturation in patients with psychiatric disorders and Turkish migration background. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2017;19(3):623‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkulu KF, Hurtig AK, Nordstrand A, Ahlm C, Ahlberg BM. Perspectives and experiences of new migrants on health screening in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research 2016;16(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J, Popay J, Pearson A, Hannes K, Booth A. Chapter 20: Qualitative research and Cochrane reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Vol. 5.1.0 [updated March 2011], The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J, Hendry M, Lewin S, Glenton C, Chandler J, Rashidian A. Qualitative "trial‐sibling" studies and "unrelated" qualitative studies contributed to complex intervention reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016;74:133‐43. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.009] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Garside R, Hannes K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series‐paper 1: introduction. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;97:35‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.09.025] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017;97:49‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuscheler F. Internationale Migration. Flucht und Asyl. 2. Vol. 14, Berlin: Springer‐Verlag, 2013. [Google Scholar]