Summary

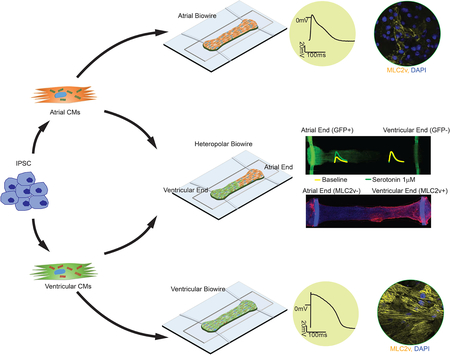

Tissue engineering using cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells holds a promise to revolutionise drug discovery, but only if limitations related to cardiac chamber specification and platform versatility can be overcome. We describe here a scalable tissue cultivation platform that is cell source agnostic and enables drug testing under electrical pacing. The plastic platform enabled on-line, non-invasive, recording of passive tension, active force, contractile dynamics and Ca2+ transients, as well as endpoint assessments of action potentials and conduction velocity. By combining directed cell differentiation with electrical field conditioning, we engineered electrophysiologically distinct atrial and ventricular tissues with chamber-specific drug responses and gene expression. We report, for the first time, engineering of heteropolar cardiac tissues containing distinct atrial and ventricular ends, and demonstrate their spatially confined responses to serotonin and ranolazine. Uniquely, electrical conditioning for up to 8 months enabled modeling of polygenic left ventricular hypertrophy starting from patient cells.

Keywords: Cardiomyocyte, tissue engineering, drug testing, electrophysiology, contractility, atrial, ventricular, heart, calcium transient, action potential, polygenic cardiac disease

Graphical Abstract

Introduction:

Profound physiological differences among species, in action potentials, ion current profiles, and contractile rates, motivate the development of human cardiac tissues for drug testing and disease modelling. Although ideal platforms should yield distinct atrial and ventricular tissues, most approaches using human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC) have focused on generating ventricular myocardium (Ahn et al., 2018; Eschenhagen et al., 2012; Lemoine et al., 2017; Lind et al., 2017a; MacQueen et al., 2018; Nunes et al., 2013; Schaaf et al., 2011; Tulloch et al., 2011); (Lemoine et al., 2018; Lind et al., 2017b; Tiburcy et al., 2017) and assessing adverse ventricular events (Vicente et al., 2015). This has been in part due to the lag in developing reliable chamber-specific hPSC differentiation protocols (Cyganek et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2017). Screening for atrial toxicity is critical, given that atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes (CMs) have distinct properties (Grandi et al., 2011). The ventricles and atria have unique chamber-specific defects and drug-induced myopathies (van der Hooft et al., 2004), making human ventricular myocardium an inadequate platform for discovery of atrial drugs. The atrial-specific platforms are especially important, given that atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, for which current treatment approaches have limited success (Chen et al., 2013; Eisen et al., 2016). Currently used pharmacological agents for treating atrial fibrillation have deadly unwanted side-effects on ventricular CMs which predispose to sudden cardiac death.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) offer the possibility to determine the pathogenesis of cardiac disease as demonstrated with cardiac microtissues used to model cardiomyopathy as a result of sarcomeric protein titin truncations (Hinson et al., 2015) or mitochondrial protein taffazin mutations (Wang et al., 2014). Yet, some of the most common cardiac diseases are complex, polygenic conditions that are strongly influenced by environmental factors. For example, prolonged hypertension leads to cardiac hypertrophy, left ventricular dysfunction and ultimately heart failure. Thus, to model polygenic disease, it is critical to provide a chronic increased workload to the cardiac tissue over a prolonged time period.

Our goal was to develop a versatile resource for the community, a platform that enables creation of electrophysiologically distinct atrial and ventricular tissues, that is capable of providing months long biophysical stimulation of 3D tissues to model a polygenic disease. This platform, termed Biowire II, enables growth of thin, cylindrical tissues, similar to human trabeculae, suspended between two parallel wires which allow simultaneous quantification of force and Ca2+ transients. Using directed differentiation protocols and electrical conditioning, atrial vs. ventricular specification is robustly achieved. We demonstrate the utility of the described resource by constructing ventricular tissues from 6 healthy hPSC lines and 6 iPSC lines derived from patients with prolonged hypertension as well as atrial tissues from 2 healthy hPSC lines. We also performed drug testing with heteropolar biowires constructed with distinct atrial and ventricular ends.

Results:

Generating Heart Tissues from Multiple Cell Sources

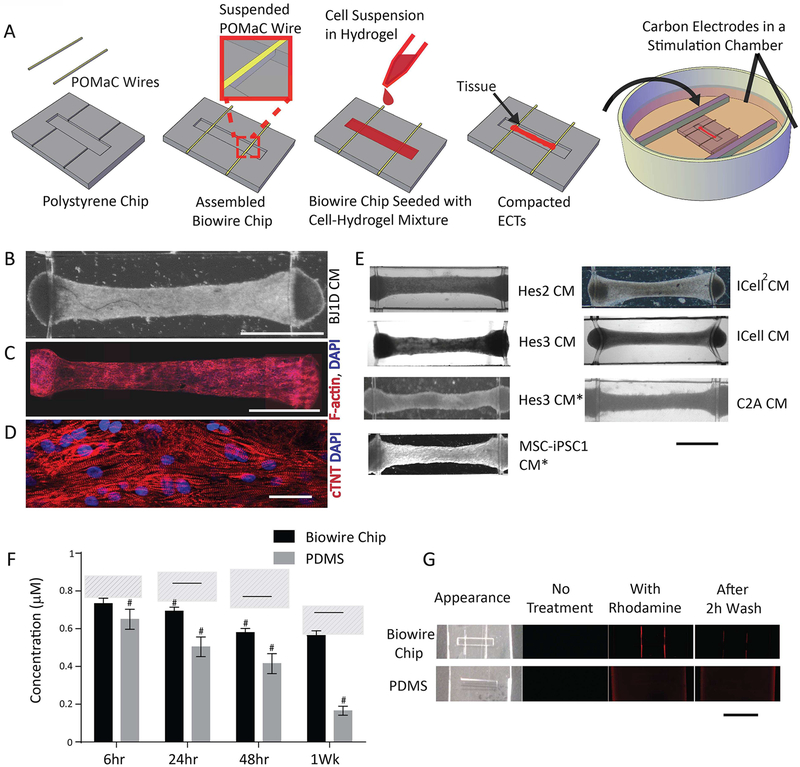

Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A illustrate the general features of our “Biowire” platform which consists of an array of microwells (5mm×1mm×0.3mm) patterned onto polystyrene sheets. Two flexible wires fabricated from a poly(octamethylene maleate (anhydride) citrate) (POMaC) polymer are secured with adhesive glue along either end of the microwells. Myocardial tissues are created by combining CMs (either ventricular or atrial or both) and cardiac fibroblasts (usually at a 10:1 ratio) with hydrogel within the microwells. During the next 7 days, cells undergo “compaction” thereby forming cylindrical trabecular strips (called Biowires II) that are suspended in the microwell but physically attached to the POMaC wires (Supplemental Figure 1A,C,D; Movie 3). Beginning at 1 week, the suspended tissues are electrically conditioned for weeks with electrical field stimulation via a pair of carbon electrodes connected to a stimulator with platinum wires (Supplemental Figure 1A).

Figure 1: The Biowire II platform for micro-scale engineered cardiac tissues.

A) Schematic. Representative tissues in Biowire II platform: B) bright field image (Scale bar=1mm); composite confocal images of C) F-actin and DAPI staining (Scale bar=1mm) and D) troponin-T and DAPI staining (Scale bar=30μm). E) Representative bright field images of tissues from several CM sources; *denotes atrial-specific tissues. (Scale bar=1mm). F) Rhodamine B absorption after incubation in Biowire II or PDMS chips for 6h, 24h, 48h and 1week. # indicates p<0.05 vs. control at each time point. Solid line indicates significant difference between the two groups. Dashed areas represent levels of rhodamine B in control polystyrene tissue culture wells. (Data shown as avg±stdev, n=3, Two-way ANOVA plus Tukey’s test). G) Bright field and fluorescence images of chips without rhodamine B incubation (No Treatment), incubated with rhodamine B for 1wk (With Rhodamine) and incubated with Rhodamine B for 1wk followed by washout for 2h (After 2h Wash). Scale bar=5mm. See also Figure S1 and Movie S1.

A typical Biowire created using ventricular CMs from BJ1D stem cells displays uniform longitudinal alignment of sarcomeric contractile proteins (Figure 1C–D) after 6 weeks in culture. Additional examples of Biowires using CMs obtained from other stem cell sources are presented in Figure 1E while Supplemental Figure 1B lists all the sources of cells used in our studies.

Biowire II Platform Exhibits Reduced Absorption of Hydrophobic Compounds

Most previous 3D cell cultivation platforms have used materials such as PDMS (Huebsch et al., 2016; Mathur et al., 2015; Nunes et al., 2013; Sidorov et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014) (Hinson et al., 2015), which absorb hydrophobic drugs (Toepke and Beebe, 2006) thereby complicating the interpretation of both long-term and short-term drug screening studies. We found that although the fluorescence levels of moderately hydrophobic compound Rhodamine B declined with time in our Biowire chips, they nevertheless remained higher than in PDMS chips when incubation times were24 hours and longer (Figure 1F). Moreover, after 6 hours, the levels of Rhodamine B were not significantly different compared to the tissue plastic well controls. Similarly, the levels of a more hydrophobic compound (Rhodamine 6G) were also higher in our Biowire chips (6.8±0.9nM) compared to PDMS chips (5.4±0.5nM, p=0.0109) when incubation times were reduced to 30 minutes, indicating less absorption by the Biowire chip compared to the PDMS chip in an acute test. The time-dependent reductions in Rhodamine B were associated with the appearance of rhodamine fluorescence throughout the PDMS chips, whereas the fluorescence in our Biowire chips was limited to the POMaC wires. After extensive washout for 2 hours, the fluorescence remained widespread in the PDMS chips while being undetectable in the Biowire chips (Figure 1G).

Stable Non-invasive Force Recordings in Biowires

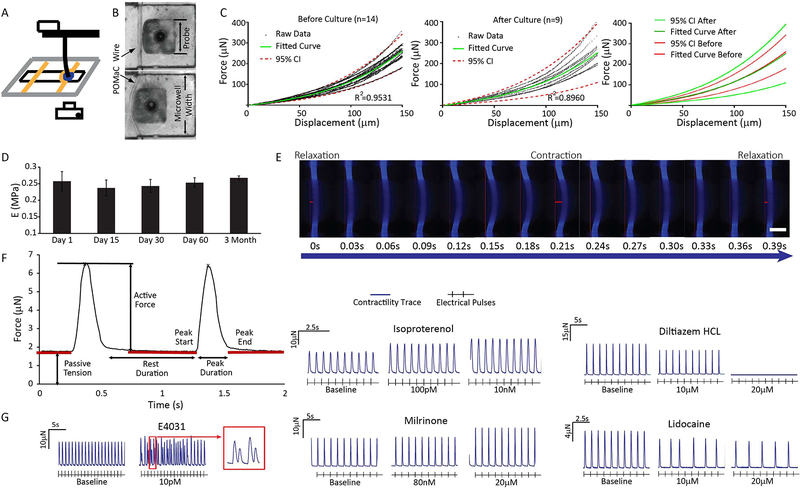

Since Biowires attach to the elastic POMaC wires at the ends of the microwells, it becomes possible to non-invasively estimate the forces generated by Biowires in response to contraction throughout the culture period by assessing the bending properties of the POMaC wires (Movie 4). For calibration, we displaced POMaC wires at their centers (Figure 2A,B). We found that, regardless of the probe cross-sectional area, POMaC wires reproducibly displayed non-linear elastic behavior over the range of wire displacements typically produced by Biowire tissues (Supplemental Figure 1 E–J). These elastic properties of the POMaC wires could be readily modeled using finite element analysis (Supplemental Figure 1H–I). Importantly, the force-displacement curves were unaltered after 6 weeks in culture (Figure 2C) and the Young’s Modulus estimates of the POMaC wires remained unchanged for up to 3 months in culture (Figure 2D).

Figure 2: Biowire II platform enables non-invasive assessment of passive tension and active force.

A) Schematic of apparatus for calibrating POMaC wires using a displacement test. B) POMaC wire configuration prior to contact and after displacement by a 0.5mm probe. C) No differences in mechanical properties of the POMaC wires were detected before and 6 weeks after cell cultivation. D) The Young’s Modulus of POMaC wires was comparable during 3 months of culture with cells and media (avg±stdev, n≥3, one-way ANOVA). E) Time lapse images showing POMaC wire bending by tissue contraction, paced at 1Hz. Scale bar=200μm. Wire bending due to passive tension and active force are illustrated by the red bars. F) Typical forces traces of contracting tissues. G) Representative traces of changes in active force and beat patterns of tissues under stimulation in response to the application of compounds with well-known cardiac actions. Tissues were generated from ventricular Hes3 hESC-CM and BJ1D iPSC-CM. See also Figure S1 and Movie S2

To assess the passive and active forces generated by the Biowires, we took advantage of the intrinsic fluorescence of POMaC wires when illuminated with blue light (λex350nm/λem470nm). Fluorescence imaging of ventricular Biowires during electrical pacing (Figure 2E) revealed that the POMaC wires are typically bent somewhat at baseline, indicating passive tension, and undergo dynamic time-dependent deformations arising from active force generation. Conversion of the wire deformations into force, via our calibration curves, allows for non-invasive estimation of force properties (i.e. resting tension, active force, rates of force development and relaxation) throughout the culture period (Figure 2F).

To illustrate the utility of dynamic force recordings, we examined the effects of several agents with known cardiac effects in ventricular Biowires, created from BJ1D iPSCs and HES3 ESCs (Figure 2G). The results reveal that: the b-adrenoceptor agonist, isoproterenol, increases contractility; the L-type calcium channel blocker, diltiazem, produces negative inotropic effects; the sodium channel blocker, lidocaine, inhibits tissue electrical excitability; the cAMP phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor, milrinone, enhances contractility and the human ether-a-go-go (hERG) channel blocker, E-4031, promotes spontaneous irregular beating patterns consistent with arrhythmias (Figure 2G).

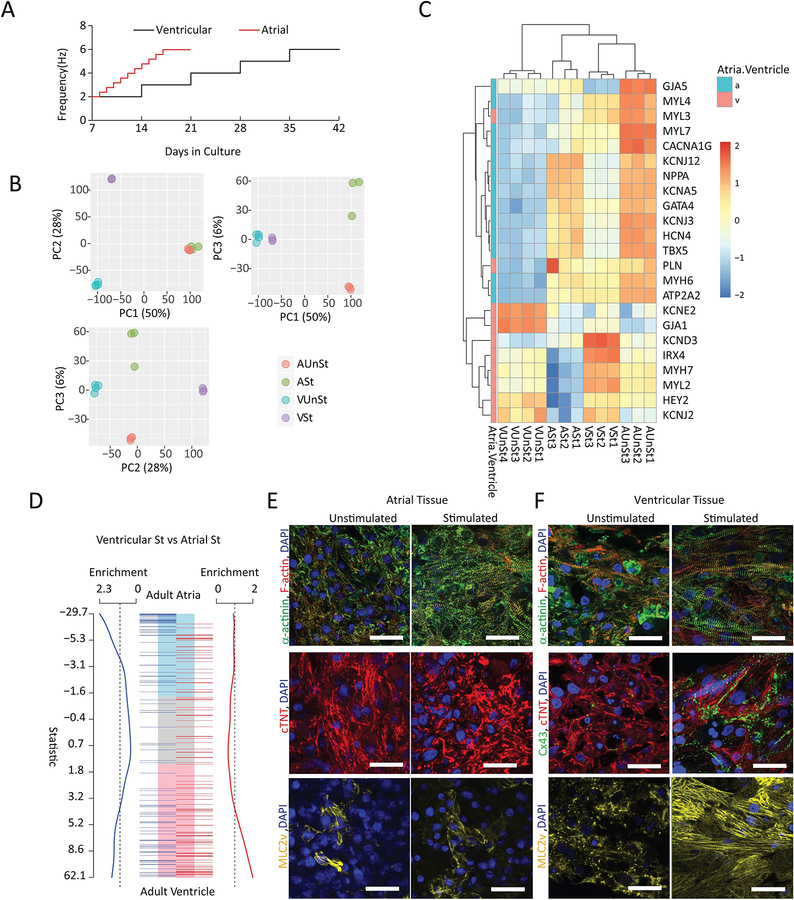

Generating Atrial and Ventricular Biowires

Biowires generated using directed differentiation protocols designed to produce either atrial or ventricular CMs (Lee et al., 2017; Lian et al., 2012) revealed that both types of tissues underwent similar cellular compaction over the first 7 days in culture (Supplemental Figure 2A). CMs appeared to occupy the majority of tissue volume (Supplemental Figure 2F) as in the native myocardium for both types of Biowires. After compaction, Biowires were routinely conditioned using chronic electrical stimulation protocols (Figure 3A) with stimulation rates that were progressively increased over time, in order to promote cardiac maturation, as shown previously (Nunes et al., 2013; Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018). Consistent with shorter refractoriness in atrial myocardium, maximum stimulation rates could be achieved more rapidly in atrial vs. ventricular Biowires (Figure 3A).

Figure 3: Atrial and ventricular tissues exhibit distinct patterns of gene expression and morphology upon chronic electrical conditioning.

A) Electrical conditioning protocols. B) Principal component analyses indicate distinct clustering of atrial versus ventricular tissues with (St) and without (UnSt) electrical conditioning (n=3–4/group). C) Heat maps illustrating differences in expression levels of selected atrial and ventricular functional markers. D) Gene set enrichments based on custom cardiac ontologies for adult ventricle and atria. Electrically conditioned ventricular Biowires are significantly enriched for human ventricular genes, whereas conditioned atrial Biowires are enriched for human atrial genes. In A-D, all tissues were derived from HES3 cells. E) Confocal images of representative atrial and ventricular tissues immunostained for sarcomeric α-actinin and F-actin (first row); connexin-43 (Cx43, only for ventricular tissues) and cardiac troponin-T (second row) and Myosin light chain 2v (MLC2v) (third row). All samples were counterstained with DAPI. Atrial tissues were derived from HES3 hESC-CM and ventricular from BJ1D iPSC-CM. Scale bars=30μm. See also Figure S3, S4.

Principal component analyses (PCA) of RNA sequencing data (63967 genes), after removal of low expressed genes (17620 genes), revealed strongly enhanced atrial or ventricular identities in response to electrical conditioning. Specifically, the first component of the PCA (Figure 3B), which accounted for >50% of the variance in gene expression, segregated atrial from ventricular tissues. The second PCA component (28% of variance) separated stimulated and unstimulated ventricular tissues, while the third component (6% of variance) separated the stimulated and unstimulated atrial tissues. This indicates that the most profound changes due to electrical conditioning were to the ventricle samples and that the gene expression changes induced in the atrial and ventricular cells by stimulation were independent (Figure 3B).

Gene Set Enrichment Analyses (GSEA) and manual curation of the clear transcriptional distinction between atrial and ventricular Biowires, with and without electrical conditioning, identified changes in known markers of cardiac chambers, metabolic and structural gene sets needed for adult heart function (Supplemental Figure 3A–D). Known atrial and atrial-enriched markers (Figure 3C) such as NPPA, GJA5, KCNJ12, MYH6 and MYL4 (Gaborit et al,2007, Asp et al., 2012) were expressed at higher levels in atrial compared to the ventricular Biowires.

We found that electrically conditioned Biowires were enriched for gene expression patterns of the corresponding adult human heart cardiac regions (Figure 3D). Consistent with these results, histological analyses demonstrate that electrical conditioning improves sarcomeric organization for both atrial and ventricular Biowires (Figure 3E,F, Supplemental Figure 2D) while also clearly promoting the expression of maturation genes in ventricular Biowires associated with contraction, Ca2+ handling and electrical properties (Figure 3C, Supplemental Figure 3A), and lipid metabolism (Supplemental Figure 3B).

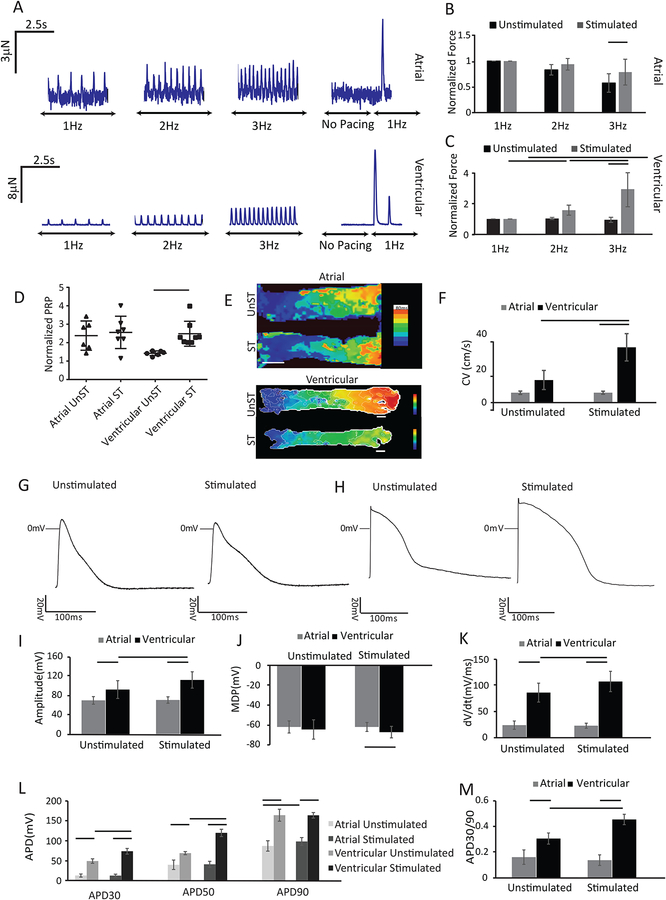

Consistent with adult human atrial muscle (Iwashiro et al., 1997), the atrial Biowires display a relatively flat force-frequency relationship (FFR) with no appreciable post-rest potentiation (PRP) of force, regardless of electrical conditioning, although normalized force amplitudes, measured with 3Hz pacing, are about ~30% larger in conditioned atrial Biowires, compared to the control atrial Biowires (Figures 4A,B,D). By contrast, electrical conditioning of ventricular Biowires increases (p<0.0001) contractile amplitudes, converts the FFR profiles from flat to positive (p<0.0001), Supplemental Figure 4A, and produces prominent PRP of force in ventricular tissues, as seen in adult human ventricles (Figure 4A,C,D). Specifically, post-rest force after pacing at 6Hz was ~2.5 fold higher (p=0.044) than the force at 6Hz pacing (Figure 4D) and was ~21-fold higher (p<0.0001) than the force measured at 1Hz. It is notable that atrial Biowires generate less force than ventricular Biowires (Figure 4A), as expected from the lower contractile protein densities in atrial vs. ventricular Biowires seen with histology (Figure 3E,F).

Figure 4: Atrial and ventricular tissues exhibit distinct functional responses after electrical conditioning.

A) Representative force traces of atrial and ventricular tissues. Summary of active forces normalized to the force at 1Hz for (B) atrial and (C) ventricular tissues with and without electrical conditioning (avg±stdev, n≥7 for atrial and n≥10 for ventricular Biowires, p<0.05 with two way ANOVA). D) Summary results for PRP normalized to the last pacing frequency (n≥6). E) Conduction velocity maps for atrial and ventricular tissues. Scale bars =500μm for atrial and 200μm for ventricular tissue. F) Summary of propagation velocity. (Avg±stdev, n≥4; two way ANOVA). Chamber-specific AP profiles of (G) atrial and (H) ventricular tissues. Summary data of : I) AP amplitudes, J) maximum diastolic potentials (MDP), K) upstroke velocities, L) AP duration measure at 30%, (APD30), 50% (APD50) and 90% (APD90) repolarization, M) APD30/APD90 ratios (APD30/90) (Avg±stdev, n≥3; two way ANOVA). Atrial tissues were created from HES3 hESC-CM and ventricular from BJ1D iPSC-CM. See also Figure S3–S7 and Movie S3, S4.

The electrical properties of Biowires also show distinct tissue specification. With time in culture the excitation threshold voltage (ET) needed to initiate contraction decreased, while the maximum capture rates (MCR) increased for both atrial and ventricular Biowires (Supplemental Figure 2B–C). Moreover, conditioning had no effect (p=0.9830) on conduction velocities (CVs) in atrial (HES3 hESC-CM) tissues (5.6±1.0cm/s without vs. 5.7±0.9cm/s with conditioning) while increasing (p=0.0077) CV from 13.0±5.5cm/s to 31.8±7.9cm/s in ventricular (BJ1D iPSC) Biowires (Figure 4 E&F, Movies 3&4). Similarly, electrical conditioning of atrial Biowires has minimal effects on action potential (AP) properties, while altering most AP parameters (except MDP and APD90), in ventricular tissues (Figure 4G–M). Of particular note, electrically conditioned ventricular tissues possess rapid upstroke velocities and display an early repolarization notch (Figure 4H), as seen in adult human epimyocardium that is linked to developmentally regulated transient outward K+ currents (Figure 4H,K) (Oudit et al., 2001).

Consistent with electrical differences between atrial and ventricular myocardium, the AP profiles in atrial tissues are distinctly different from ventricular tissues (Figure 4 I–M). Of particular note, the APD30/APD90 ratio, which is a distinguishing feature between atrial and ventricular CMs, was 0.45±0.04 for ventricular tissues while being only 0.14±0.04 for atrial tissues, similar to human myocardium (~0.75 for ventricular versus ~0.1 for atrial CMs) (Dawodu et al., 1996; O’Hara et al., 2011).

The Biowires showed high degree of reproducibility in passive tension, active force amplitudes, PRP, MCRs and ETs between batches of conditioned ventricular tissues generated from BJ1D cells (Supplemental Figure 4B–F), as well as with different stem cell sources. For example, while the genetic, structural and functional results described above were recorded in atrial Biowires generated from HES3 stem cells and in ventricular Biowires created from BJ1D cells, conditioned ventricular Biowires generated from HES3 and HES2 CMs exhibit similar positive FFR and undergo similar remodeling with electrical conditioning (Supplemental Figure 4G–N). However, some baseline variability exists between Biowires generated from different cell sources, HES3, iCell and BJ1D stem cells (Supplemental Figure 5A–D) in upstroke velocities and impulse propagation velocities which were lower (p<0.0001) in HES3 derived Biowires (i.e. 25.3±14.0 mV/s and 5.7± 0.9 cm/s) than in BJ1D-derived Biowires (108.8±19.6 mV/s and 31.8±7.9 cm/s). These differences can be explained by the higher MDP in HES3 Biowires, which is expected to reduce Na+ channel availability via channel inactivation. Likewise, conditioned atrial Biowires derived from different stem cells source (i.e. HES3 and MSC-IPS1) also produced relatively similar electrical properties (Supplemental Figure 6). Importantly, standard pharmaceutical agents such as blockers of L-type Ca2+ channels (verapamil) and hERG channels (dofetilide) exhibited predictable responses on APs of ventricular Biowires, (Supplemental Figure 5E–N), thus further establishing their utility in drug testing.

Responses of Atrial vs Ventricular Tissues to Agents Affecting Functional Properties

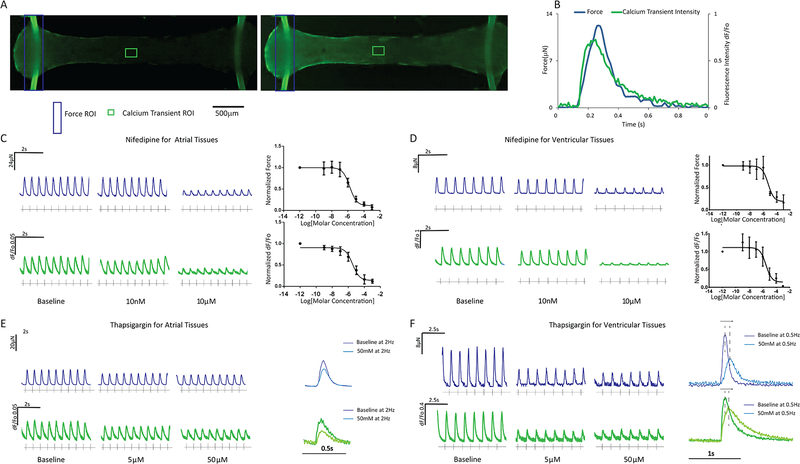

Incubation of Biowires with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators allows the simultaneous measurement of force and Ca2+ in our platform (Figure 5A,B; Movie 5,6), thereby providing opportunities for convenient drug screening. To illustrate this capability (Figure 5C,D), we applied the L-type Ca+ channel blocker, nifedipine which dose-dependently reduced force and Ca2+ transients with similar IC50s in atrial Biowires (IC50=2.0±1.2μM for force and 3.6±1.5μM for Ca2+ transients) versus ventricular Biowires (IC50=4.5±1.4μM for force and 3.1±1.9μM for Ca2+ transients). Similarly, the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor, thapsigargin, dose-dependently decreased force and Ca2+ transient amplitudes (Figure 5E,F) in both atrial and ventricular preparations with higher potency in the ventricle, as expected with SERCA2a inhibition (Davia et al., 1997). Moreover, at low pacing rates, thapsigargin prolonged the time-to-peak and decay rates of both force and Ca2+ in ventricular, but not atrial Biowires, consistent with differences in sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+ handling between atrial and ventricular human myocardium (Blatter, 2017).

Figure 5: Simultaneous force and Ca2+ transient measurements and their responses to drugs in atrial and ventricular tissues.

A) Typical images of biowires loaded with a Ca2+ dye (Fluo-4) before (left) and after (right) field stimulation. B) Representative transients. Typical force (blue) and Ca2+ transients (green) in (C) atrial or (D) ventricular tissues following the treatment with Nifedipine and the associated dose response (avg±stdev, n=3) or treatment with Thapsigargin in (E) atrial or (F) ventricular tissues along with overlays of forces and Ca2+ transients before (baseline) and after Thapsigargin addition. Atrial tissues were derived from HES3 hESC-CM and ventricular from BJ1D iPSC-CM. See also Movie S5 and S6.

As expected (Zang et al., 2005), acetylcholine-dependent K+ currents (i.e. IK,ACH) induced by the Type 2 muscarinic receptor agonist, carbachol, abbreviated APDs in atrial Biowires without affecting these parameters in ventricular tissues (Supplemental Figure 7A–H). Another notable difference between atrial and ventricular myocardium is the presence in atria of KV1.5-dependent ultra-rapidly activated potassium currents, IKur, a current with a high sensitivity to block by 4-aminopyridine (4AP)(Burashnikov and Antzelevitch, 2008). Accordingly, 4AP at low doses (25μM) increased AP amplitudes and prolonged APD30 in the atrial Biowires, without measurable effects on ventricular tissues (Supplemental Figure 7I–P), although higher doses of 4AP did prolong APD, which arise from blockade of the 4AP-sensitive Kv1.4-based transient outwards currents (Ito) found in ventricular myocardium (Castle and Slawsky, 1993; Li et al., 1995).

In Vitro Disease Modeling Using the Biowire Platform

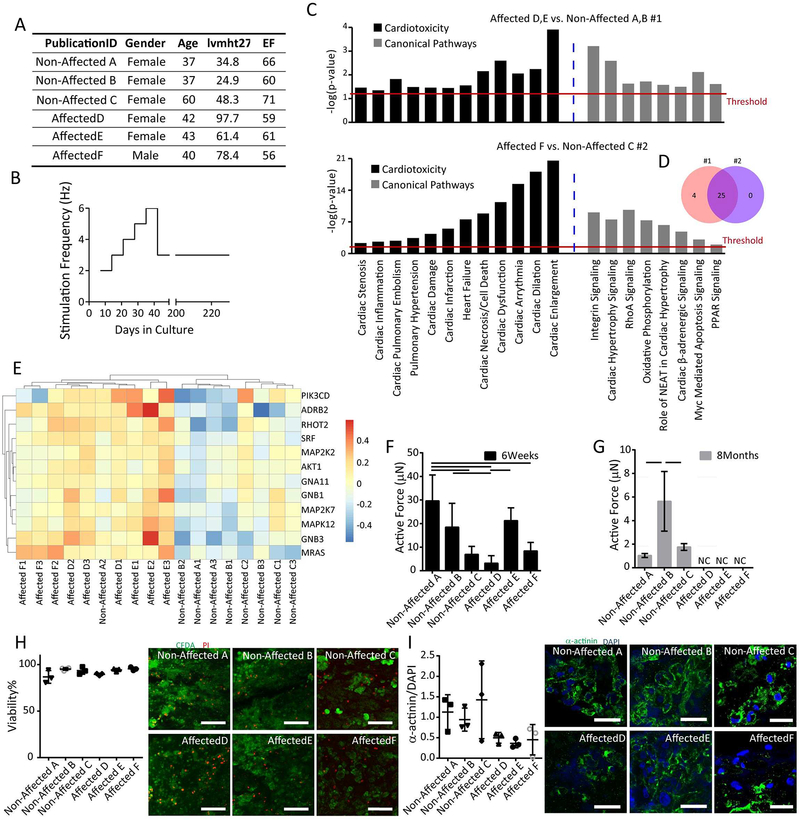

To demonstrate proof-of-concept for the utility of our Biowire platform in disease modeling (Figure 6), iPSCs were obtained from patients enrolled in the NHLBI HyperGEN study, one of the largest epidemiological studies focusing on left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in families with primary hypertension, which started recruiting in 1996 (Williams et al., 2000). We compared ventricular tissues generated from iPSC-CMs obtained from hypertensive participants with clear evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy (Affected group) versus participants without ventricular hypertrophy (Non-Affected group) (Figure 6A).

Figure 6: Biowire II platform enables cardiac disease modelling.

A) Summary of clinical features, hypertrophy index (lvmht27) and ejection fraction (EF), of hypertensive patients contributing iPSCs. B) Long-term electrical conditioning protocol mimicking chronic increased workloads in ventricular tissues created from patient iPSC-CMs. C) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEAs) was performed in two independent experiments (Non-affected A, B vs. Affected D, E; Non-affected C vs. Affected F) revealing enrichment in the Affected groups for genes associated with cardiotoxicity and cardiac related canonical pathways (determined by IPA Tox List analysis). D) Venn diagram indicates overlap of enriched signaling pathways related to cardiotoxicity from the two experiments. The functional categories shown are ones with Benjamini-Hochberg multiple correction p≤0.05. E) Heat map showing a sub-set of genes related to cardiac hypertrophy. F) Active force was reduced in tissues derived from the patients exhibiting left ventricular hypertrophy in response to a prolonged hypertension (Affected D vs. Affected E, p=0.0387) compared to the Non-Affected groups (Non-affected A vs. Affected D, p=0.0006; Non-affected A vs. Affected F, p=0.0023; Non-affected B vs. Affected D, p=0.0382, One way ANOVA with Tukey’s test) after 6 weeks in culture. G) Active force was absent in all tissues from the Affected (Affected D, E and F) versus Non-Affected participants (Non-affected A, B, and C) after 8 months culture period. H) Live (green) and dead (red) staining of tissues at the end of 8 month culture period. Viability was quantified with no significant differences among the groups. Scale bar=100μm; I) Confocal images and quantification of the presence of sarcomeric α-actinin (green) counterstained with DAPI (Blue), Scale bar=30μm (One way ANOVA with Tukey’s test).

Although the underlying basis for the phenotypic differences between the Affected group and Non-Affected group is unknown, hypertension as well as the associated cardiac responses to the increased workloads generally represent a polygenic disorder. Thus, we hypothesized that chronic electrical conditioning protocols, designed to mimic the chronic increases in cardiac workloads arising from hypertension, will uncover differences between the patient groups. Accordingly, tissues were conditioned during the first 6 weeks using our standard ventricular conditioning protocols. Thereafter, electrical stimulation was continued at 6Hz for 1 additional week, after which the stimulation frequency was reduced to 3Hz and maintained for up to 6 months (Figure 6B). Total cultivation times were as long as 8 months.

In contrast to previous studies focusing on monogenic cardiac diseases, modeling of polygenic disease necessitates more comprehensive genetic profiling analysis. Interestingly, profiling of RNA expression in conditioned ventricular Biowires (Figure 6C) after 8 months of culture demonstrates distinct gene expression profiles for Affected versus Non-Affected patients as revealed from gene set enrichment analyses. These studies were performed in two separate batches of Biowires generated from Affected and Non-Affected participants as summarized in Figure 6C. In both batches, enrichment in 25 cardiac toxicity and canonical signaling pathways was consistently uncovered in Biowires from Affected vs Non-Affected patients (Figure 6D), including pathways broadly linked to pathological remodeling in cardiovascular disease such as cardiac enlargement, cardiac dilatation, cardiac dysfunction, heart failure and cardiac hypertrophy signaling (Figure 6C). Analysis of the genes related to cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure within individual replicates of independent experimental groups, further indicates clear upregulation in all samples derived from the Affected participants (Figure 6E), with only one of 3 replicates from one of the Non-Affected participants (Non-Affected A) exhibiting a relatively high expression of the hypertrophy associated genes (Figure 6E).

Consistent with these differences in mRNA expression, long-term culturing for 8 months lead to profound differences in contractile function between Biowires from the Affected participants compared to the Non-Affected, with all 3 Affected samples generating virtually no force compared to the Non-Affected samples (Figure 6F,G). Despite these profound differences in contractile function, no differences in cell viability (Figure H) or cardiomyocyte content (Figure I) were observed in the Biowires from the two groups of participants.

Engineering of Atrio-ventricular Biowires

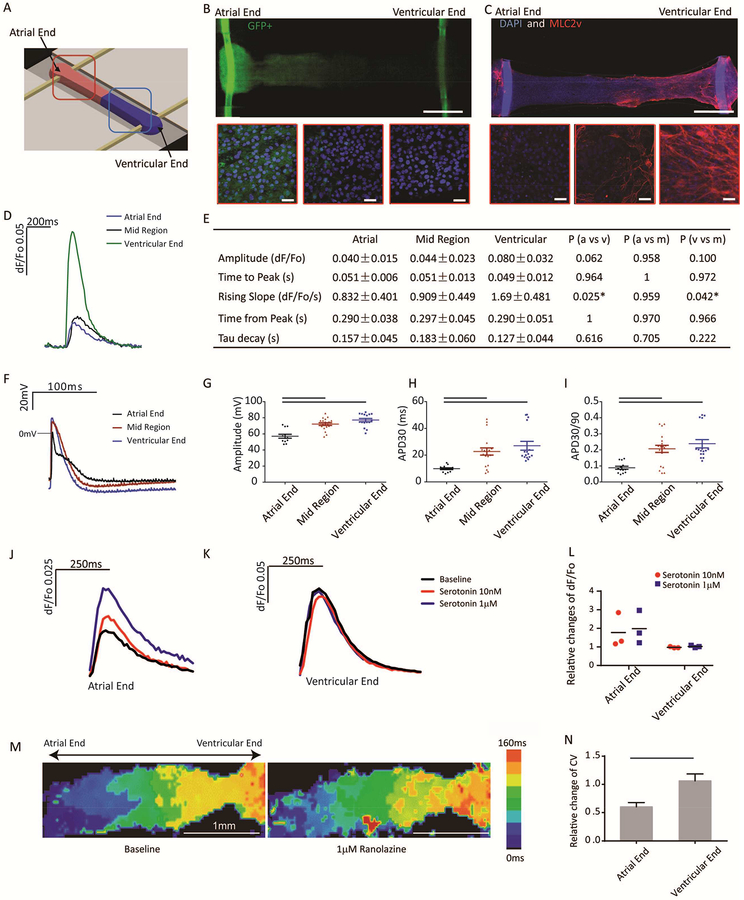

A potential advantage of our Biowire platform is the ability to generate composite cardiac tissues containing atrial and ventricular zones which would allow efficient screening of differential responses to agents with chamber-specific actions. With this in mind, we spatially patterned heteropolar Biowires by adding atrial and ventricular CMs to opposite ends of the microwells (Figure 7A) as validated using GFP fluorescence to identify atrial CMs (Figure 7B) and MLC2v staining to identify ventricular CMs (Figure 7C). As expected, the transition zone between the atrial and ventricular ends was ~200μm wide and showed mixed atrial and ventricular properties (Figure 7B,C). Functionally, Ca2+ transients were larger and rose more rapidly while APs showed distinct properties at the ventricular end compared to the atrial end, with intermediate properties in the transition zone (Figure 7D–I).

Figure 7: Engineering of atrioventricular tissues.

A) Schematics of the experimental set-up. B) Atrial (GFP+) and ventricular (GFP−) CMs are placed at the opposite ends of the Biowires suspended between two POMaC wires exhibiting green autofluorescence. Zoomed images from right-to-left are taken from the atrial end, the mid region (mixed atrial and ventricular) and the ventricular end. (Scale bar=0.5mm,) C) Only ventricular end of the tissues stains positive for myosin light chain 2v (MLC2v). Zoomed-in insets from the atrial end, mid region and ventricular end were compared. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI. POMaC polymer wires exhibit blue autofluorescence (Scale bar = 0.5mm, Insets scale bar=30μm). F) Representative traces of Ca2+ transients from atrial, mid and ventricular region of atrioventricular tissues. E) Quantification of Ca2+ transients. AP F) profiles, G) amplitude H) APD30 and I) APD30/90 from atrial, mid and ventricular regions were compared. Representative traces of Ca2+ transients in response to serotonin at J) the atrial end and K) the ventricular end on the tissue. L) Change in Ca2+ transient amplitude in response to serotonin normalized to the baseline. (n=3, two way ANOVA with Sidak’s test); M) Optical mapping of impulse propagation before and after application of 1μM ranolazine. N) Quantification of the conduction velocity upon ranolazine application after normalization to the baseline (avg±stdev, n=4, p=0.0007, Student’s t test). In J-N, both ends of the tissue were derived from HES3 hESC. See also Movie S7.

To illustrate the utility of such preparations, we examined the effects of the 5-HT agonist, serotonin and the rapid voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker, ranolazine, which are reported to have preferential atrial effects (Burashnikov et al., 2007). Indeed, serotonin increased Ca2+ transients in the atrial, not ventricular, ends of Biowires (Kaumann et al., 1991) (Figure 7J–L), while Ranolazine decreased conduction velocity in atrial regions without affecting ventricular zones, consistent with preferential blockade of Na+ in atrial CMs (Figure 7M–N).

Discussion:

Biowire II platform uniquely combines the benefits of organ-on-a-chip engineering and organoid self-assembly to enable non-invasive, multi-parametric readouts of physiological responses. These capabilities are made possible by the self-assembly of tissues between two parallel POMaC wires, matching the mechanical properties of the native cardiac tissue (10–500kPa (Nagueh et al., 2004; Omens, 1998)) and allowing the force to be continuously measured. The configuration enables cultivation of multiple tissues suspended on only 2 parallel wires, in contrast to the microcantilever approach that requires a pair of silicone posts for a cultivation of a single tissue.

Common platforms for cultivation of 3D cardiac microtissues incorporate PDMS because of its biocompatibility and ease of use (Eschenhagen et al., 2012; Lind et al., 2017a; Nunes et al., 2013; Schaaf et al., 2011; Tulloch et al., 2011) but at the expense of absorption of small hydrophobic molecules (Toepke and Beebe, 2006). Although the Biowire II platform is plastic, the small amount of drug absorption is associated with the POMaC wires and the presence of low absorption polyurethane adhesive (Domansky et al., 2013) used to secure the POMaC wires to the plastic. Fortunately, functional Biowire II devices can also be constructed without the adhesive.

A major advantage of the platform is the ability to continuously and non-invasively measure Ca2+ transients and active force, in combination with other endpoint measurements such as conduction velocity and APs. Future developments will enable simultaneous force, Ca2+ transient and electrical measurements.

Another advantage is a small number of input CMs (i.e. ~0.1 million/tissue) compared with many previous studies requiring 0.5–2 million cells/tissue (Mannhardt et al., 2016; Nunes et al., 2013; Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018). Consequently, although the absolute active force per tissue is significantly lower in the current work compared to that reported in other studies (Jackman et al., 2016; Mannhardt et al., 2016; Riegler et al., 2015; Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018), the force per cross-sectional area (or per cell) is on the order of those reported in other studies (Supplemental Figure 4O). These results suggest a possible community effect, such that the contribution of CM number to the collective contractile force in a tissue is non-linear. Yet, fold increase in the force between 1–3Hz was much higher in the current ventricular preparations, compared to those reported in a recent landmark study (Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018).

Our data indicate that both, distinct directed differentiation protocols and the electrical conditioning contribute to atrial vs. ventricular phenotype divergence in the platform. Electrical conditioning appeared to be particularly effective for ventricular preparations, causing upregulation of high density lipoprotein genes consistent with developmental metabolic changes that decrease the reliance of adult cardiomyocytes on glycolysis, while also strongly promoting sarcomeric organization, the expression of chamber-specific proteins such as MLC2v and generating quiescent tissues at the end of cultivation, in the absence of external stimulation that display a robust positive FFR, PRP, a fast conduction velocity and for the first time displaying notches in the AP profile. Consistent with the native adult atrial muscle physiology (Iwashiro et al., 1997), the atrial Biowires display a relatively flat FFR, minimal PRP and a slower conduction velocity.

By contrast, the minimum diastolic potential of the tissues (−70mV) was still somewhat depolarized compared to the adult myocardium levels (−80 to −90mV)(Drouin et al., 1995), especially in atrial biowires, and this correlated with relatively slow upstroke velocities (~110mV/ms) compared to the adult myocardium (254–303mV/ms), despite being faster than fetal myocardium (5–13mV/ms)(Koncz et al., 2011; Mummery et al., 2003).

Chamber-specific cardiotoxicity is considered to be a major issue (Santini and Ricci, 2001). In this regard, we provide evidence for chamber-specific drug responses. We also observed higher expression levels of KCNJ2 responsible for Kir2.1 protein production and the corresponding IK1 current in ventricular tissues compared to atrial tissues.

The Biowire platform may enable us to fully understand the disease mechanisms responsible for progression from LVH to heart failure. Although all the NHLBI HyperGEN-LVH study patients suffer from prolonged hypertension, associated with marked elevations in cardiac workloads, they present with highly variable LVH. Our blinded studies allowed the identification of three cell lines derived from Affected hypertensive participants with the greatest amount of LVH, vs Non-affected participants with normal LV mass and contractile function. Clearly, the tissues derived from the Non-affected participants were better at resisting the rapid pacing protocol and maintaining contractility, compared to those derived from the Affected participants. The identified RNA expression differences between the two groups reflect the underlying disease phenotype of LVH.

To generate atrio-ventricular Biowires from a single cell source, we used HES3-NKX2–5eGFP/w cells; and to facilitate imaging of cell location we used a combination of GFP+ HES3 atrial CM at one end and BJ1D ventricular cells at the other end. Although, BJ1D cells enabled us to prepare ventricular tissues with high conduction velocities (31.8±7.9cm/s), in the range of adult myocardium (30–100cm/s), HES3 ventricular preparations achieved velocities of only 5.5±1.3cm/s, leading to relatively low conduction velocities of HES3 atrio-ventricular preparations.

The effects of serotonin on the cardiovascular system are complex, consisting of bradycardia or tachycardia, hypotension or hypertension, and vasodilation or vasoconstriction (Saxena and Villalon, 1990). It has been reported to cause positive inotropy in atrial CMs, and no inotropic effect in ventricular CMs (Jahnel et al., 1992). Atrio-ventricular Biowires were able to capture the complex effect of serotonin, revealing the positive inotropic effect of serotonin on the atrial end but not the ventricular end. Ranolazine is currently in clinical trials with Gilead. This drug is largely a Na+ channel blocker, affecting both atria and ventricle, albeit in different ways. There is some controversy related to how and whether it has atrial-selective effects (Jahnel et al., 1992). Conduction velocity significantly slowed down at the atrial end, after introduction of ranolazine, but not at the ventricular end. The half-inactivation voltage of atrial CMs is more negative than ventricular CMs; therefore more sodium channels inactivate at baseline membrane for atrial CMs at stroke or takeoff point compared with ventricular CMs. Because ranolazine is effective on the inactive sodium channel, it affects atrial more than ventricular cells (Burashnikov et al., 2007). Thus heteropolar Biowires enable us to capture the effects of drugs with complex or incompletely understood mechanisms of action.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND REOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Milica Radisic (m.radisic@utoronto.ca).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Lines

Predominantly ventricular cardiomyocytes (CMs) were derived from the human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines HES2 (Female) and HES3-NKX2–5eGFP/w (Female) using the embryoid body (EB) (Yang et al., 2008) differentiation protocol and the human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) line BJ1D (male) (Nunes et al., 2013) using the monolayer differentiation protocols (Lian et al., 2012) as previously described. Ventricular cell populations contained 74.7±6.3% (n=9) of CMs on average, based on cardiac troponin T expression analysis using flow cytometry, at the end of directed differentiation protocols.

C2A hiPSC derived cardiomyocytes were differentiated in EBs as previously described (Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018). Gender information cannot be provided according to the terms used to obtain the line.

iCell and iCell2 cardiomyocytes were purchased from Cellular Dynamics International (CDI) Inc, Madison, Wisconsin and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Gender information should be available from the company upon request.

Induced pluripotent stem cells were derived from the Non-affected A (Female), Non-affected B (Female), Non-Affected C (Female), Affected D (Female), Affected E (Female), and Affected F (Male) patients and differentiated into CMs by CDI. CDI kindly provided these differentiated CMs for the project.

Predominantly atrial CMs were derived from HES3-NKX2–5eGFP/w hESCs and MSC-iPSC1(Park et al., 2008) using an atrial-specific EB differentiation protocol as described (Lee et al., 2017).

Briefly, all trans retinoic acid (0.5 μM, Sigma) was added during the cardiac mesoderm specification stage (days 3–5 of differentiation) to promote atrial cardiogenesis. At day 20 of differentiation, atrial CMs from HES3-NKX2–5eGFP/w hESCs were analyzed and defined based on the proportion of NKX2.5+, cTNT+ and MLC2v− cells using flow cytometry, 79.1±8.0%, n=10. For predominantly atrial CMs from MSC-IPS1 cell lines (Male), 73.2 % ± 7.7% of total cells were atrial CMs (cTNT+ and MLC2V−), n=2 batches. Differentiation cultures were dissociated to single cells for subsequent tissue seeding, as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016).

This study did not have large enough sample size to reach any conclusion on the influence of sex on the study outcome as 5 female and 1 male patient line was used in disease modelling. Thus, the sex analysis was not performed.

For authentication of cells that are expanded and differentiated in house, specifically C2A-CM, BJ1D iPSC, HES2 hESCs, HES3-NKX2–5eGFP/w hESCs and cFB (see below), the samples are sent to the Genetic Analysis Facility, The Centre for Applied Genomics, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, for Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling. The authentication information for commercial cell lines should be available from the manufacturer.

Primary Cultures

Human cardiac fibroblasts, cFBs, (Clonetics™ NHCF-V) were obtained from LONZA. The cells were cultured and passaged according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cFBs were thawed and cultured on 75cm2 tissue culture flasks with FGM™−3 Cardiac Fibroblast Growth Medium-3 BulletKit™. Trypsin/EDTA (Life Technology) was used to detach cells during passaging. Passage 2–5 of cFB was used in the study.

Rat CMs (mixed genders) were isolated from neonatal rat (Sprague Dawley) hearts three days after birth as described (Zhang et al., 2016).

METHOD DETAILS

Device Fabrication

Polystyrene sheet patterned with microwells:

A repeating pattern consisting of rectangular microwells (5mm × 1mm × 300μm, L × W × H) interconnected by two parallel grooves (200μm × 100μm, W × H) was designed using AutoCAD. An SU-8 photoresist master mold was used to produce a negative polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) master mold (Zhang et al., 2016). The PDMS master was used to hot emboss the microwells into a polystyrene sheet (Supplemental Figure 1A).

Polymer wires:

Poly(octamethylene maleate (anhydride) citrate) (POMaC) polymer wires (100μm × 100μm, W × H) were prepared from a pre-polymer as previously described(Zhang et al., 2016). To fabricate the POMaC wires, a PDMS mold with parallel microchannels of the desired dimensions was fabricated from an SU-8 master, as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). The PDMS mold was lightly pressed onto a glass slide and the POMaC pre-polymer solution was perfused through the microchannels by capillary action. The pre-polymer solution was then cured by UV exposure (5100mJ/cm2). Due to the stronger adhesion of the POMaC wires to glass than PDMS, the POMaC wires remained adherent to the glass when the PDMS mold was carefully peeled off the glass slide. The POMaC wires were soaked in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to release them from the glass slide and manually placed into the two parallel grooves patterned into the polystyrene sheet (Supplemental Figure 1A). In some configurations, clear polyurethane 2-part adhesive (SP 1552–2, GS Polymers, Inc.) was used in a minimal quantity to fix the POMaC wires in place.(Domansky et al., 2013)

Hydrogel Preparation

Collagen hydrogel (500μL) was prepared by combining high concentration rat tail collagen (153μL at 9.82mg/mL, Corning) with 15% (v/v) Matrigel (75μL, BD Biosciences), NaHCO3 (50μL at 2.3mM, Sigma), NaOH (5μL at 10mM, Sigma), deionized sterile H2O (167μL) and 1X M199 (50μL, Sigma) to result in a final collagen concentration of 3.0mg/mL.

Electrical Stimulation Chamber Fabrication

Two1/8 inch-diameter carbon rods (Ladd Research Industries) were fixed 1cm apart (inner edge-to-inner edge) to the bottom of a 10cm tissue culture dish using polyurethane 2-part adhesive (Supplemental Figure 1A). The carbon rods were connected to the lead wires of an external electrical stimulator (Grass Technology S88X Square Pulse Stimulator) with platinum wires (Ladd Research Industries).

Generation of Engineered Cardiac Tissues

Strips of polystyrene containing eight microwells were transferred to a 10cm tissue culture dish (Supplemental Figure 1A). The strip surface was rinsed with 5% (w/v) Pluronic Acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and then air dried in the biosafety cabinet. Dissociated cardiac cells and cardiac fibroblasts (LONZA, Clonetics™ NHCF-V) were mixed in a 10:1 (ventricular cardiac cells : fibroblasts) or 10:1.5 (atrial cardiac cells : fibroblasts) cell number ratio, pelleted and resuspended at a concentration of 5.5×107 cells/mL (unless otherwise specified) in a hydrogel. This results in a 74,700 CMs per tissue on average. The cell-hydrogel suspension (2μl per well) was seeded into the polystyrene microwells, to give a final seeding concentration of 1.1×105 cells/microwell or 7.47×104 CMs/microwell. The tissues were cultured for 7 days to allow for remodeling and compaction around the POMaC wires. Daily bright field images of the tissues were taken using an Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope and CellSens software (Olympus Corporation). By Day 7, the tissues synchronously contracted and deflected the POMaC wire with each contraction.

To generate atrioventricular tissues, dissociated atrial cardiac cells and cardiac fibroblasts were mixed in a 10:1.5 cell number ratio. Dissociated ventricular cells and cardiac fibroblasts were mixed in a 10:1.5 cell number ratio. The mixed cells were pelleted and resuspended at a concentration of 5.75×107 cells/mL in collagen hydrogel. When seeding, cell-hydrogel mixture containing atrial CMs (1μL) was seeded on one side of the Biowire II well first, followed by a mixture containing ventricular CMs (1μL) seeded on the other side. After seeding, tissues were cultured for 7 days to allow for remodeling and compaction around the POMaC wires.

Electrical Stimulation Protocols

On Day 7, each strip of 8 tissues was transferred to an electrical stimulation chamber, such that the tissues were positioned between the carbon rods. On Day 7 and weekly thereafter, 4X bright field movies were taken of beating under stimulation at 1Hz. The minimum voltage per cm required to stimulate the synchronized contraction of the tissue (excitation threshold, ET) and the maximum frequency the tissue could achieve in response to the stimulation pulse at twice the ET (maximum capture rate, MCR) were measured and recorded. POMaC is intrinsically fluorescent, hence the deflection of the polymer wire due to tissue contraction was isolated and tracked under the blue fluorescent light. Blue channel movies (10X objective; λex = 350nm, λem = 470nm; 100 frames/s, 5ms exposure) were taken to record the bending movement of the POMaC wire during tissue contraction from 1–3Hz (1Hz increase every 20sec) to measure the force-frequency relationship (FFR). After testing for FFR, the tissue had been stimulated at high frequency (6Hz) for 20sec; stimulation was then turned off and re-initiated at 1Hz to measure the post-rest potentiation (PRP) of the force. To quantify the FFR and PRP, all measurements were normalized to the 1Hz baseline values. All imaging was performed using an Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescent microscope and CellSens software (Olympus Corporation).

The Day 7 electrical excitability assessments were used to determine the long-term stimulation conditions, specifically stimulation voltage (1.5-times the ETavg). Electrical stimulation was continued with weekly monitoring of ET, MCR, FFR, and PRP. Culture media was changed every week.

Electrical stimulation protocol of weekly 1Hz increase in frequency was implemented for ventricular maturation. If average MCR exceeded 4Hz after one week of 2Hz stimulation or exceeded 5Hz after one week of 3Hz stimulation, stimulation frequency can be changed directly from 2Hz to 4Hz or 3Hz to 5Hz to accelerate the process. End point assessments were performed when a positive FFR in the range from 1 to 3Hz was achieved. If a positive FFR was not observed once the frequency reached 6Hz, stimulation continued at 6Hz, until a positive FFR was observed. The stimulation voltage was adjusted weekly to 1.5-times the average ET, down to a minimum voltage of 3.5V/cm. For atrial preparations, a similar procedure was applied with the daily increase of the stimulation frequency by 0.4Hz, from 2Hz to 6Hz, then retaining the stimulation frequency at 6Hz for 1week.

For the ventricular disease model preparation, the experimentalists were blinded to the study groups. Tissues were generated from the Non-affected A, Non-affected B, Non-affected C, Affected D, Affected E, and Affected F CMs. Electrical stimulation started at 2Hz on day 7 post cell seeding and the protocol of 1Hz weekly step-up was used until the frequency reached 6Hz, at which point it was maintained at 6Hz for one week. Subsequently, the frequency was decreased to 3Hz and maintained at that level for the remainder of the cultivation period, up to 6 months. Tissues were assessed after 6 weeks and 8 months of culture.

For atrioventricular preparations, electrical stimulation started at 2Hz on day 7 after seeding and the protocol of 1Hz weekly step-up was used until the frequency reached 6Hz. If average MCR exceeded 4Hz after one week of 2Hz stimulation, or exceeded 5Hz after one week of 3Hz stimulation, stimulation frequency could be changed directly from 2Hz to 4Hz or 3Hz to 5Hz to accelerate the process. The stimulation at 6Hz was maintained for 1 week, at which point it was decreased to 3Hz and maintained for a period of several days until the tissues were used for drug testing.

Atrial and Ventricular Tissue RNA Sequencing

RNA was isolated using a commercially available kit: PicoPure™ RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher, KIT0204) and RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen #79254). RNA sequencing was performed at the Illumina CSPro Next Generation Sequencing facility of the Donnelly Sequencing Centre at the University of Toronto. Alignments were made using the pseudo alignment method from Kallisto (Bray et al., 2016). The transcriptome used was obtained from ESEMBL, human genome build GRCh38.p10, yielding 63967 genes and over 200,000 spliced transcripts. Single end mode with a mean fragment insert size of 270 and SD of 40 bases was used. Counts were quantified from Kallisto output files using Sleuth (Pimentel et al., 2017). Technical and biological variance was calculated using Sleuth to yield test statistics based on a linear model, where the treatment was corrected against the intercept. No batch was present in the dataset as all samples were sequenced across 4 flow cells to generate approximately 20 million reads per sample. Log fold changes were calculated using DESeq2. Heat maps were generated using the R function pheatmap.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Normalized counts of RNA-sequencing data were processed using the R function voom to transform counts into Gaussian distributions. The R function camera was used to calculate gene set enrichments to the Gene Ontology Biological Process gene sets obtained from the Broad Institute and custom ontology files generated from differential expression analysis using the R library limma of deposited human atrial and ventricle gene expression data (GSE2240). The gene matrix table file for gene set enrichment of atria and ventricle gene expression data was generated using custom R scripts. Output from camera gene set enrichment analysis was formatted as a generic table format for graphing and analysis in Cytoscape using custom R scripts. Network graphs of gene set enrichments were generated in Cytoscape using enrichmentmap. Sub-networks were named using clustermaker and word cloud annotating for enrich words with a bonus for adjacent words.

Gene Expression for Patient Derived Cells

Gene expression of ventricular tissues based on two individual hiPSC-CM cell lines (Affected D, E, and F and Non-affected A, B, and C) at the end of 8 month cultivation with electrical conditioning, was assessed as previously described (Aggarwal et al., 2014). Whole transcriptome sequencing was done utilizing the Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit and the Ion Torrent Proton System (Thermofisher Scientific) following manufacturer’s recommendations. Data analysis was performed using Qiagen’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software with the overlay tool IPA-Tox. The feature “Tox List” was set at default parameters to analyze genes contributing to principle component analysis between Affected D, E, and F and Non-affected A, B, and C, focusing on cardiotoxicity.

Elastic Modulus of Polymer Wires

To determine the elastic modulus of the POMaC wires, testing strips (1.5mm × 10mm × 0.1mm) were cured at 5100mJ/mm2, the same condition as used for preparation of Biowire II platform. The tensile test was conducted with a Myograph (Kent Scientific) in the longitudinal direction of strips (n≥3), using a modified ASTM D638–10 Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics as described (Zhang et al., 2016).

To test the long-term POMaC wire stability, the testing strips were placed in a 12-well plate in media (DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin). A transwell insert (Corning) seeded with 1×105 neonatal rat CMs, isolated as described above, was added to each well. Media was changed twice a week and mechanical tests were performed on Day 0, 15, 30, 60 and 90.

Polymer Wire Force-Displacement Curves

The force required to displace the POMaC wire was determined using a microscale mechanical tester, MicroSquisher (CellScale). The 0.1524mm-diameter tungsten probe was modified with custom tips (0.5mm−, 0.7mm−, and 0.8mm-diameter) to recapitulate the tissue diameter and curvature on the POMaC wire. The custom tips (half ellipse, 4:1 diameter ratio) were fabricated from an SU-8 master by soft lithography and attached to the tungsten probe using an adhesive (T-GSG-01 Titan Gel). Four separate 8-well polystyrene strips with POMaC wires were tested per probe tip. The polystyrene strips were soaked in media for 7 days prior to testing. During the test, the polystyrene strip was affixed to a 10cm dish and testing was performed in culture media. The probe tip was placed at one end of microwell and moved towards the POMaC wire at a velocity of 2.5μm/s. The tip displaced the wire at the midsection, applying the force perpendicular to the long axis of the POMaC wire. The force, probe displacement (0–150mm) and time were recorded (n≥55). The experimental data, over the entire range, for each custom tip were fit to a third-degree polynomial equation, generating a force-displacement calibration curve for each custom probe tip (Supplemental Figure 1E).

To assess if cell cultivation around the polymer wire affects the force-displacement curve, a batch of polystyrene chips with POMaC wires were fabricated and divided into two groups. Both groups were incubated in media at 37°C for a week before use. Group one was tested right after the incubation as described above, whereas group two was tested after cell seeding and approximately two months of ventricular tissue conditioning. A probe tip of 0.5mm was used during the tests. Fitted curves, 95% confidence interval curves, and R2 values were calculated with Prism 6.0.

Finite Element Modeling (FEM)

The finite element model simulated the behaviour of the POMAC during mechanical testing. The model included the polymer wire and the indenter; the dimensions and material properties for the FEM components were set to match the conditions during experimental testing. The two ends were constrained by fixed supports and the load was applied to the polymer wire through the indenter. The mesh was made of solid elements, and the number of elements and mesh nodes in the model for the 0.5mm indenter were 11448 and 52622, for the 0.7mm indenter were 15702 and 71225, and for the 0.8mm indenter were 18468 and 83232, respectively. A neo-Hookean, hyperelastic material model was used for the POMAC material to account for the non-linear behavior and the large deformations observed during physical testing. Poisson ratio was assumed to be 0.5.

Active and Passive Force for Cardiac Tissues

Blue channel image sequences were analyzed using a custom MatLab code that traced the maximum deflection of the POMaC wire. Average tissue width (diameter) and width of the tissue on the polymer wire (Tw) were measured from still frames of the 4X bright field video of the tissue in the relaxed position (Supplemental Figure 1C, D). Total (at peak contraction) and passive (at rest) POMaC wire deflections were converted to force measurements (μN) using the force calibration curves described in the previous section. The final readouts for the total and passive tension of tissue were then interpolated according to the Tw and custom tip sizes. The active force was calculated as the difference between the total and passive tension. (Figure 2C). The custom MatLab code was used to calculate the passive tension, active force, contraction and relaxation duration, and upstroke and relaxation velocity.

Absorption Testing

For the acute test, polystyrene strips containing microwells and POMaC wires, with and without the adhesive, were cut into chips (9mm × 9mm × 1mm) containing a single microwell. Chips of the same geometry were also made with PDMS. The polystyrene and PDMS chips were incubated in 650μL Rhodamine 6G (10nM; Sigma-Aldrich) in closed round bottom polypropylene test tubes at room temperature for half an hour. Rhodamine 6G solution without any chip incubating at same condition was used as a control. 200μL of the dye solution was transferred to a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was read using a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices; λex = 526nm, λem = 555nm), (n=12).

For the long-term absorption test, polystyrene strips containing microwells and POMaC wires, with and without the adhesive, were cut into chips (9mm × 9mm × 1mm) containing a single microwell. Chips of the same geometry were also made using PDMS. The polystyrene and PDMS chips were incubated in 1mL Rhodamine B (1μM; Sigma-Aldrich) in a 24 well-plate at 37°C for up to 1wk. Tissue culture treated 24 well-plates were incubated with the dye in the absence of any chips as a control. At 6h, 24h, 48h, and 1wk, 100μL of the dye solution was transferred to a 96-well plate and the fluorescence was read using a SpectraMax i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices; λex = 540nm, λem = 625nm), (n=3). Additionally, fluorescent images of the chips were taken in the absence of treatment, after 1wk of dye incubation, and after 2h of washing following 1wk of dye incubation.

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Tween20, and blocked with 10% FBS. Immunostaining was performed using the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-cardiac Troponin T (cTnT) (ThermoFisher; 1:200), rabbit anti-Connexin 43 (Cx-43) (Abcam; 1:200), mouse anti-α-actinin (Abcam; 1:200), rabbit anti-myosin light chain-2v (Santa Cruz; 1:200), goat anti-caveolin3 (Santa Cruz; 1:100); and the following secondary antibodies: donkey anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam; 1:400), donkey anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 594 (Life Technologies; 1:200) and donkey anti-goat-Alexa Fluor 647 (Life Technologies; 1:200). Phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 660 (Invitrogen; 1:200) was used to stain F-actin fibers. Conjugated vimentin-Cy3 (Sigma; 1:200) was used to stain for vimentin. Confocal microscopy images were obtained using an Olympus FluoView 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Live and dead staining was performed with CFDA (1:1000, Life Technologies) and Propidium Iodide (75:1000, Life Technologies) in PBS. Viability was calculated as the average intensity of CFDA divided by the sum of average intensities of CFDA and PI. (n≥3)

Sarcomere presence was quantified by average intensity of α-actinin divided by the average intensity of DAPI counterstain. (n=3)

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for at least overnight and washed 3-times with PBS. Secondary-fixation was done with 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS for 1 hr. The tissues were dehydrated using an ethanol series from 50% to 100%. Tissues were infiltrated using Epoxy resin and polymerized in plastic dishes at 40°C for 48h. The tissues were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate after sectioning. Imaging was performed using a Hitachi H-7000 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Ltd.) in Microscopy Imaging Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto.

Contractile and Ca2+ Transients

To investigate the contractile effects of various compounds on the tissues, a custom testing chamber was fabricated in a 6-well plate modified with an extraction/injection port connected to a 5mL syringe, a pair of carbon electrodes (set 1cm apart) with platinum wire lead attachments and a custom 3D-printed holder for a polystyrene chip with a single microwell. Prior to testing, the tissue was transferred to the custom testing chamber and placed in the environmental chamber on the microscope stage (37°C, 5% CO2), where it was allowed to equilibrate for 30min in the presence of electrical field stimulation (1Hz, at ET). A bright field video of the tissue was taken before testing to obtain all the necessary measurements for the force calculation. For testing, the voltage was increased to 10% above the ET, and videos were taken of one polymer wire (10X objective). Prior to the test compound injection, media were extracted and injected through the port twice at 10min intervals to pre-condition the tissue to the testing process. Compounds were diluted in media at concentrations 1000-fold higher than the desired final concentration. For compound testing, 1/3rd of the media was extracted from the chamber, the compound was added to the extracted media and then slowly injected back into the testing chamber. After 10–15min, videos in the blue channel were recorded. The procedure was repeated for sequential drug dosages. The videos were analyzed using the custom MatLab software, as indicated for the weekly FFR assessments.

To investigate the relative changes of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, tissues were incubated with the Ca2+ dye Fluo-4 NW (Thermo Fisher) for 30min at 37°C prior to testing. To obtain both Ca2+ transients and contractility readouts consecutively and synchronously, the testing process was performed using both green light channel (λex = 490nm, λem = 525nm) and/or blue channel at 10X or 4X magnification. The ImageJ software (NIH) Stacks plugin was used to determine the average intensity of a region of interest in the tissue located at a distance from the PoMAC wire, wherein the movement artifacts were minimal. The ratio of peak tissue fluorescence intensity to baseline intensity, dF/F0 was calculated to determine the relative changes in intracellular Ca2+ in the presence of the compound. For the consecutive force and Ca2+ transient readouts, contractile measurements were extracted from the blue channel as described before. For the synchronous readouts, the contractile measurements were extracted from the green channel videos using modified version of the ImageJ SpotTracker plugin. Prism 6.0 was used to calculate the IC50.

Intracellular Recordings

Tissues were perfused with 35–37°C Kreb’s Solution (118mM NaCl, 4.2mM KCl, 1.2mM KH2PO4, 1.2mM MgSO4, 1.8mM CaCl2, 23mM NaHCO3, 2mM Na-pyruvate and 20mM glucose, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH 7.4) or DMEM medium. They were paced at twice the ET. The APs were recorded with high impedance microelectrodes (60–90MΩ) filled with 3M KCl, connected to an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Recordings were performed in current clamp mode at 2kHz and signals were analyzed using the Clampfit 10 Data Analysis Module of the pCLAMP™ 10 Electrophysiology Data Acquisition & Analysis Software (Axon Instruments). The movement of the tissue was minimized by perfusing with 10μM blebbistatin (Toronto Research Chemicals) for 20min. The effect of various compounds on the AP was assessed by preparing an appropriate dilution of the compound in Krebs’s Solution or DMEM.

Optical Mapping

Tissues were perfused with 5μM voltage sensitive dye, Di-4-ANEPPS (Invitrogen), in Kreb’s Solution at 35–37 °C for 20min. Dye fluorescence was recorded on an MVX-10 Olympus fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation) equipped with a charged coupled device (CCD) (Cascade 128, Photometrics). The 1cm sensor had 128×128 pixel resolution. Recordings were performed at 500 frames/s with 0 exposure time. Biowires were paced at 1.5–2Hz with a Pulsar 6i Stimulator (FHC, Inc.) at twice the ET.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATSTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6.0. All data are represented as mean ± standard derivation (SD) or standard errors of mean (SEM), which have been indicated in each figure. Indicated sample sizes (n) represent individual tissue samples. For intracellular recordings, sample size (n) represents the number of cells analyzed from more than three independent experiments. No statistical method was used to predetermine the samples size. Disease modelling was conducted in a blinded fashion. Differences between experimental groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-way ANOVA (more than two groups). Experiments with two different variables were analyzed with two-way ANOVA. Normality test (Shapiro-Wilk) and pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Tukey’s post hoc method or Holm-Sidak method or Sidak-Bonferroni method) were used for one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA tests. P<0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The RNA sequencing data has been archived at the short read archive at NCBI. The accession number is GSE114976 for atrial and ventricular tissues (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE114976) and GSE122661 for disease models (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE122661). Other information and requests for data and software may be directed to, and will be fulfilled by the lead contact Dr. Milica Radisic (m.radisic@utoronto.ca).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Related to Figure 1 and Figure 2. Experimental set-up and force-displacement curves for POMaC wires. A) A Petri-dish is fitted with a pair of carbon electrodes and a poly-styrene strip for cultivation of eight cardiac tissues. Position of tissues and polymer wires with respect to carbon electrodes is indicated in the zoomed-in images. B) Summary of experimental conditions, *denotes the preparation for atrial differentiation. C) Measurements of tissue width on the POMaC wire and the tissue diameter. Average tissue diameter is determined from multiple locations. D) The representative image of cross-section from a tissue, scale bar=100μm. Force-displacement curves for the POMaC wire obtained by microscale mechanical testing using custom E) 0.5mm, F) 0.7mm and G) 0.8mm diameter probes. Panels E-G) show the polynomial equation fit and R2 to the experimental data (data presented as mean±stdev, n≥55). Panels H-J) show the finite element model of the polymer wire force-displacement behavior using a neo-Hookean model (purple lines) compared to the experimental data illustrated by the average values (green lines) and 95% confidence intervals (red lines).

Supplemental Figure 5: Related to Figure 4. AP characterization of ventricular tissues generated from different cell lines and responses of BJ1D ventricular tissues to verapamil and dofetilide. HES3, BJ1D and iCell cell lines were assessed with sharp microelectrode recordings performed at the end of cultivation and exhibited some differences in A) AP profiles of HES3, BJ1D and iCell derived CMs respectively. 90% of BJ1D CMs and 39% of iCells had notch in their AP profiles. B) Minimum diastolic potential and C) Upstroke velocity. AP duration at D) 30% repolarization (APD30), 50% repolarization (APD50) and 90% repolarization (APD90). Data presented as mean±SEM, n≥3 tissue, One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test. Numbers in brackets indicate the total number of individual cells sampled. Ventricular tissues (derived from BJ1D hiPSC-CMs) treated with (E-I) verapamil and (J-N) dofetilide. E, J) Representative AP recordings, F, K) AP amplitude; G, L) Minimum diastolic potential; H, M) Upstroke velocity and I, N) APD30, APD50, and APD90. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n=3 tissue, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc comparison of test concentrations to 0 μM. Numbers in brackets indicate the total number of individual cells sampled at each concentration.

Supplemental Figure 6: Related to Figure 4. AP characterization of atrial tissues generated from two different cell lines. MSC-IPS1 A) and HES3 B) cell lines were assessed with sharp microelectrode recordings at the end of cultivation and exhibited some differences in AP profiles, C) AP amplitude, D) Minimum diastolic potential, E) Upstroke velocity and F) AP duration at 30% repolarization (APD30), 50% repolarization (APD50) and 90% repolarization (APD90). Numbers in brackets indicate the total number of individual cells sampled. Data presented as mean ± SEM, n≥4 tissue, One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test.

Supplemental Figure 7: Related to Figure 4. Atrial and ventricular tissues exhibit chamber specific electrophysiological responses to drugs. A) Representative AP of an atrial tissue treated with carbachol. Quantification of B) minimum diastolic potential, C) upstroke velocity, D) duration to 30% repolarization (APD30), to 50% repolarization (APD50) and to 90% repolarization (APD90), for atrial tissues treated with carbachol. (mean±stdev, n≥3, one way ANOVA). E) Representative AP of a ventricular tissue treated with carbachol. Quantification of the F) minimum diastolic potential, G) upstroke velocity, H) APD30, APD50 and APD90, for ventricular tissues treated with carbachol. (mean ± stdev, n≥3, one way ANOVA). I) Representative AP of an atrial tissue treated with 4-aminopyridine (4AP). Quantification of the J) minimum diastolic potential, K) upstroke velocity, L) APD30, APD50 and APD90, for atrial tissues treated with 4AP. (mean ± stdev, n≥3, one way ANOVA). M) Representative AP of a ventricular tissue treated with 4AP. Quantification of the N) minimum diastolic potential, O) upstroke velocity, P) APD30, APD50 and APD90, for ventricular tissues treated with 4AP. (mean±stdev, n≥3, one way ANOVA). Atrial tissues were derived from HES3 hESC-CM and ventricular from BJ1D iPSC-CM.

Supplemental Movie 1. Related to Figure 1. A representative movie of Biowire contraction. The video was recorded from a stimulated BJ1D Biowire paced at 1Hz at 100 frames/s, 5ms exposure by Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope.

Supplemental Movie 2. Related to Figure 2. A representative movie of POMAC wire displacement. This type of recording in blue fluorescence was used to calculate the force based on tracking polymer wire movement. The video was recorded from stimulated BJ1D Biowire paced at 1Hz at 100 frames/s, 5ms exposure by Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope.

Supplemental Movie 3. Related to Figure 4. A representative example of conduction velocity imaging in an atrial Biowire. Atrial HES3 Biowire was stained with a potentiometric dye, Di-4-ANEPPS to measure conduction velocity. The video was recorded at 2ms frame rate, from a Biowire paced at 2Hz, by MVX-10 Olympus fluorescence microscope equipped with a Cascade 128 camera. Electrical wave appears as a brighter color.

Supplemental Movie 4. Related to Figure 4. A representative example of conduction velocity imaging in a ventricular Biowire. Ventricular BJ1D Biowire was stained with a potentiometric dye, Di-4-ANEPPS to measure conduction velocity. The video was recorded at 2ms frame rate, from a Biowire paced at 2Hz, by MVX-10 Olympus fluorescence microscope equipped with a Cascade 128 camera. Electrical wave appears as a brighter color.

Supplemental Movie 5. Related to Figure 5. A representative example of Ca2+ imaging in an atrial Biowire. Stimulated HES3 atrial Biowire was stained by Flou4 to record Ca2+ transients at 2Hz pacing rate. The video was recorded at 91frames/s, 5ms exposure by Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope.

Supplemental Movie 6. Related to Figure 5. A representative example of Ca2+ imaging in a ventricular Biowire. Stimulated BJ1D ventricular Biowire was stained by Flou4 to record Ca2+ transients at 1Hz pacing rate. The video was recorded at 83 frames/s, 5ms exposure by Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope.

Supplemental Movie 7. Related to Figure 7. A representative movie of contraction in an atrioventricular Biowire. The atrial end was made of HES3 atrial cardiomyocytes (shown in green due to the expression of GFP reporter) and ventricular BJ1D cardiomyocytes at the other end, to facilitate imaging. The video was recorded in green fluorescence at 83 frames/s, 5 ms exposure by Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope.

Supplemental Figure 2: Related to Figure 3 and Figure 4. Tissue compaction, electrical excitability properties and structural characterization. A) Atrial and ventricular tissues compact in a similar fashion in the first week after seeding. (n≥8). B) Excitation Threshold (ET); C) Maximum Capture Rate (MCR), for unstimulated and stimulated atrial and ventricular tissues. All data presented as mean ± stdev, n≥8. Red dashed lines represent the average ET and MCR at day 7 after tissue compaction. Atrial tissues were derived from Hes3 ESC-CM and ventricular from BJ1D iPSC-CM. D) Representative TEM image of a stimulated ventricular tissue generated from BJ1D hiPSC-CMs; Scale bar=500nm.Representative confocal image of E) a stimulated ventricular tissue generated from C2A hiPSC-CMs immunostained for caveolin 3 and counterstained with the nuclear stain DAPI, and F) a stimulated ventricular tissue generated from BJ1D hiPSC-CMs immunostained for vimentin, F-actin and counterstained with DAPI; Scale bar=30μm.

Supplemental Figure 3: Related to Figure 3 and Figure 4. Gene expression analysis of atrial and ventricular tissues with and without electrical conditioning. A) Differential expressions of selected ventricular maturation markers. B) Electrical conditioning significantly enhances expression of genes related to high density lipoprotein (HDL) metabolism in ventricular tissues. Network graph representation of enriched ontologies annotated for sub-networks C) Gene ontologies (biological process) that were significantly upregulated with electrical conditioning in atrial Biowires. D) Gene ontologies (biological process) that were significantly upregulated with electrical conditioning in ventricular Biowires. Atrial and ventricular tissues were created from HES3 hESC-CM.

Supplemental Figure 4: Related to Figure 4. Batch-to-batch variability, cell line variability and comparison of active forces achieved by ventricular tissues. Consistency of ventricular tissues generated from four batches of BJ1D hiPSC-CMs. A) A representative trace of an FFR and PRP test. B) Active force (one way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). C) Passive tension from 1 to 3Hz, D) Post-Rest Potentiation (PRP), E) Excitation Threshold (ET) and F) Maximum Capture Rate (MCR). Data presented as mean ± stdev, (n≥4 tissues per experiment). After applying maturation protocol, electrical function was improved for ventricular tissues derived from HES2 and HES3 cell lines in terms of G, H) Active force from 1 to 3Hz; H, L) Normalized active force from 1 to 3Hz; I, M) Excitation Threshold (ET) and J, N) Maximum Capture Rate (MCR); (Data presented as mean ± stdev, n≥3, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). O) Summary of active forces achieved by engineered cardiac tissues derived from human CMs in other publications.

Highlights.

Positive force frequency and post-rest potentiation are achieved in human tissues

Atrial and ventricular tissues have distinct electrophysiology and drug responses

Atrio-ventricular tissues show spatially confined drug responses

Long-term electrical conditioning enables polygenic cardiac disease modelling

A scalable cardiac tissue cultivation platform enables assessment of multiple parameters of tissue function, drug testing and modeling of atrio-ventricular disease.

Acknowledgements: