Abstract

The presence of callous-unemotional (CU) traits designates a subgroup of antisocial youth at risk for severe, aggressive, and stable conduct problems. As a result, these traits should be considered as part of the criteria for conduct disorder. The present study tests two possible symptom sets (four and nine item criteria sets) of CU traits that could be used in diagnostic classification, assessed using self-report with a sample of 643 incarcerated adolescent (M age = 16.50, SD = 1.63 years) boys (n = 493) and girls (n = 150). Item response theory analysis was employed to examine the unique characteristics of each criterion comprising the two sets to determine their clinical utility. Results indicated that most items comprising the measure of CU traits demonstrated adequate psychometric properties. Whereas the nine item criteria set provided more information and was internally consistent, the briefer four item set was equally effective at identifying youth at-risk for poor outcomes associated with the broader CU construct. Supporting the clinical utility of the criteria sets, incarcerated boys and girls who endorsed high levels of symptoms across criteria sets were particularly at-risk for proactive aggression and violent delinquency.

Keywords: callous-unemotional traits, DSM-5, conduct disorder, aggression and violence, item response theory analysis

Callous-unemotional (CU) traits, defined as a lack of empathy, guilt, and uncaring attitudes, have proven useful in identifying antisocial youth who show a distinct pattern of severe, chronic and aggressive conduct problems that are resistant to traditional interventions (Frick, 2012; Frick & White, 2008). As a result, the criteria for Conduct Disorder (CD) in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) includes a specifier for youth showing significant levels of CU traits called “With Limited Prosocial Emotions” (Frick & Moffitt, 2010). The addition of this CU specifier is expected to provide greater information about current and future impairment and to aid in treatment planning for youth diagnosed with CD (Frick & Nigg, 2012), of whom an estimated 12 to 46% (depending on the assessment method) present with significant CU traits (Kahn, Frick, Youngstrom, Findling, & Youngstrom, 2012; Pardini, Stepp, Hipwell, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Loeber, 2012; Rowe, et al., 2010). For example, the presence of CU traits at school age is predictive of adult criminal behavior and antisocial personality symptoms, after controlling for symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), and childhood-onset CD (Byrd, Loeber, & Pardini, 2012; McMahon et al., 2010). Although there has been significant study into the clinical utility of a CU specifier among community and clinic-referred youth, there has been relatively little systematic investigation into the utility of this diagnostic classification among incarcerated adolescent samples, who likely comprise a large majority of youth with CD (Kahn et al., 2012; Pardini et al., 2012). Furthermore, prior studies support the need for further research to refine the optimal indicators of CU traits.

Within the realm of self-report, the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, 2004) is a popular tool whose scores have consistently demonstrated reliability and validity in identifying antisocial youth at risk for severe current and future impairment (e.g., Roose, Bijttebier, Decoene, Claes, & Frick, 2010). The ICU was one of two measures of CU traits used to develop potential symptom criteria sets for DSM-5 (see Frick & Moffitt, 2010). The first four item criteria set was developed by identifying those items that consistently loaded on the CU dimension of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (Frick & Hare, 2001) in community and clinic-referred samples (Frick, Bodin, & Barry, 2000). The second nine item set was developed based on confirmatory factor analyses of the ICU in four samples, each from a different country and using a different language translation (Essau, Sasagawa, & Frick, 2006; Fanti, Frick, & Georgiou, 2009; Kimonis et al., 2008; Roose et al., 2010). Items loading > .40 on the overarching CU factor and/or being one of the two highest loading items on a subfactor in two or more samples were selected. The association between the two resulting criteria sets and various external criteria (e.g., delinquency, aggression, emotional processing on laboratory tasks) were compared and both sets exhibited expected associations with comparable effect sizes (Frick & Moffitt, 2010). As a result, the shorter four item set was selected for further analyses, which revealed that youth meeting the diagnostic threshold of two or more CU symptoms showed significantly greater impairment on external criteria compared with youth with only one symptom or those with no CU traits. This led Frick and Moffitt (2010) to propose that the CU specifier be diagnosed when youth meeting full diagnostic criteria for CD persistently (over at least 12 months) present with two or more of the four following characteristics in more than one relationship or setting: (1) Lack of Remorse or Guilt: Does not feel bad or guilty when he/she does something wrong (except if expressing remorse when caught and/or facing punishment); (2) Callous-Lack of Empathy: Disregards and is unconcerned about the feelings of others; (3) Unconcerned about Performance: Does not show concern about poor/problematic performance at school, work, or in other important activities; or (4) Shallow or Deficient Affect: Does not express feelings or show emotions to others, except in ways that seem shallow or superficial (e.g., emotions are not consistent with actions; can turn emotions “on” or “off” quickly) or when they are used for gain (e.g., to manipulate or intimidate others).

Importantly, incarcerated youth comprised only 10% of the sample included in the secondary data analyses leading to the new specifier for CD, despite the markedly higher prevalence of CD among justice-involved youth compared with community samples (Garland et al., 2001; Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002). Further, the secondary data analyses did not include incarcerated girls. As a result, the present study advances existing research on the CU specifier by establishing support for the reliability and validity of the four and nine item criteria sets among a unique sample of incarcerated boys and girls. Specifically, the present study aims to (1) compare the psychometric properties of the two criteria sets and the prevalence of their constituent items; (2) provide a more rigorous test of the two criteria sets using a latent-variable statistical approach, item response theory (IRT) analyses. IRT permits an assessment of the unique item characteristics of each CU criterion comprising the sets across the CU latent-trait continuum; and (3) test the validity of specific cut points from the criteria sets using several external criterion measures. IRT advances knowledge about the items comprising the criteria sets by permitting an examination of (a) what level of latent CU trait is necessary to endorse each CU criterion (i.e., difficulty), (b) how well each CU criterion item discriminates between adolescents across the CU latent-trait continuum (i.e., discrimination), and (c) how criteria sets compare with respect to how much information they provide along the CU continuum.

Methods

Participants

The data for the present study is comprised of youth from five studies collected independently but analyzed together. In total, participants were 643 incarcerated adolescents (493 boys, 150 girls) between the ages of 12 and 24 (M = 16.50, SD = 1.63). The sample was ethnically diverse including 37.2% Black (n = 239), 27.4% Hispanic (n = 176), 24.3% White (n = 156), and 11.2% youth self-reporting as “other” race/ethnicity (e.g., bi- or multi-racial; n = 72). Youth were recruited from across eight secure confinement facilities located in the Southwestern (two facilities; N = 273) or Southeastern (six facilities; N = 370) United States. According to Tukey post-hoc comparisons, girls from the Southeastern sample were significantly younger (M = 14.95, SD = 1.29) than boys from the Southwestern (M = 16.48, SD = 0.76; d = 1.17) and Southeastern (M = 16.17, SD = 1.34; d = .90) samples. Girls from the Southwestern sample were significantly older (M = 18.72, SD = 1.93) than girls from the Southeastern sample (d = 2.89) and boys from the Southwestern (d = 1.71) and Southeastern (d = 1.97) samples, F (3,640)=119.68, p<.001. Boys in the Southwestern and Southeastern samples did not differ significantly in age. Consistent with regional differences, cross-tab analysis suggested that there was greater representation of Hispanic youths in the Southwest (10.2% White, 25.3% Black, 48% Hispanic, 16.5% other) and greater representation of White and Black youth in the Southeast (35.1% White, 47.3% Black, 11.4% Hispanic, 6.2% other, χ2(df=3, N=643) = 160.90, p<.001, φ = .49).

Procedures

Parents of all youth enrolled in the studies provided informed consent and youth provided assent for study participation. Given the high proportion of Hispanic youth housed in the Southwestern facilities, Spanish-speaking parents were consented in their native language by a research assistant fluent in Spanish. However, only youth participants who were fluent in English were allowed to participate in the study. As such, no translation was required. All study measures described below were administered to youth in English. University institutional review boards approved all procedures. Full details of the procedures used to recruit the samples are reported in XXX, 2011; XXX, 2012; XXX, 2012 [blinded for review].

Measures

Callous-unemotional traits.

The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU; Frick, 2004) is a 24-item self-report measure designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of CU traits. Items are rated on a four point Likert-type scale (0 = Not at all true to 3 = Definitely true). Several studies support the construct validity of the ICU in community and incarcerated youth (e.g., Kimonis et al., 2008; Roose et al., 2010).

Aggression.

Since data were combined from separate studies conducted by different principal investigators, two sets of criterion measures were used across regional samples. The 40-item self-report Peer Conflict Scale (PCS; Marsee et al., 2011) was administered to the Southeastern samples, and the 24-item abbreviated version of Little and colleagues’ self-report Aggression Inventory (Little, Jones, Henrich, & Hawley, 2003) was administered to the Southwestern samples to measure aggression. PCS items are rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (“Not at all true”) to 3 (“Definitely true”). The 20-item PCS total overt aggression composite, and its two component subscales (i.e., reactive overt and proactive overt) were used in the present study. Prior research supports the factor structure, internal consistency (αs ranging from .82 to .89), and validity of PCS subscale scores among juvenile offenders (Marsee et al., 2011). The abbreviated self-report Aggression Inventory was normed on a sample of adolescents. The overt aggression total score and its component reactive overt (6-item; e.g., If others have angered me, I often hit, kick or punch them; α = .81) and proactive overt (6-item; e.g., I often start fights to get what I want; α = .88) subscales were used in the current study.

Delinquency.

The Self-Reported Delinquency Scale (SRD; Elliott & Ageton, 1980) was administered to the Southeastern samples and a modified version of the Self Report of Offending (SRO; Huizinga, Esbensen, & Weiher, 1991) scale was administered to the Southwestern samples to measure variety of delinquency. Serious offenders tend to engage in a wider range of offending behaviors than less problematic offenders such that variety of offending behaviors provides a consistent and valid estimate of the severity of delinquent activity (Osgood, McMorris, & Potenza, 2002). The SRD lists 36 questions about illegal juvenile acts selected from a list of all offenses reported in the Uniform Crime Report with a juvenile base rate of greater than 1%. For each question the youth is asked to respond with a “yes” or “no” regarding whether he/she has ever done the behavior. A total delinquency composite was created by summing the number of delinquent acts committed (with a possible range of 0–36; α = .89). In addition to the total score, the current study also used the 8-item violent delinquency subscale (e.g., “have you ever been involved in gang fights?”; α = .72). The modified SRO requires participants to report on whether or not they had engaged in seven types of antisocial and illegal activities (e.g., “stolen someone else’s things,” “purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you”), of which the majority inquire about involvement in violent activities specifically (5 items; e.g., “beaten up, mugged, or seriously threatened another person,” “attacked someone with a weapon,” “taken someone else’s things by force”). No youth endorsed that they “raped, attempted to rape, or sexually attacked someone” so this item was excluded. Only the SRO total score was used in the current study and it demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α = .79).

Plan of Analysis

To approximate the clinical decision needed to determine if a symptom is present or absent, ICU criteria were dichotomously coded (0 = item rated below 3; 1 = item rate equal to 3; Frick & Moffitt, 2010). This approach was used on the basis that the middle ratings of 1 (somewhat true) and 2 (very true) are not comparable, such that a rating of “1” on the positively worded items that mostly comprise the CU specifier (e.g., “I am concerned about the feelings of others”), when reverse coded (“2”) would not reflect the absence of that trait as would a rating of “0” (not at all true). Cronbach’s coefficient alphas, item to total scale correlations, and the person separation index (PSI) were used to test the reliability of scores for the CU specifier criteria sets. Item to total scale correlations greater than .30 indicate good discrimination and a Cronbach’s alpha greater than .70 suggests that a self-report instrument is internally consistent (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). A PSI ≥ 1.0 represents greater spread of persons along a continuum, and suggests that the instrument is sensitive enough to distinguish between high and low risk individuals (Wright & Stone, 1999). Frequency analyses were used to determine the prevalence of significant CU traits using the two-symptom threshold.

We applied two-parameter IRT logistic models to the four and nine item criteria sets to define the relation between the criterion items and the underlying unobserved latent construct of interest (CU severity). IRT estimates two parameters for each item within each set: difficulty (threshold) and discrimination (slope). The item difficulty parameters represent the point along the CU latent-trait continuum at which 50% of the sample is likely to endorse an item. Criteria with high thresholds are more severe and are endorsed less frequently (Embretson & Reise, 2000). Discrimination parameters indicate the degree or strength of the relation between the item and the underlying latent-trait with higher values providing greater precision across the latent-trait continuum (Embretson & Reise, 2000). Item characteristic curves (ICCs) were plotted and examined for each of the items within the two criteria sets. The typical ICC has a well-defined S-shape associated with it, and indicates that the probability of endorsing a specific item increases monotonically as the latent-trait increases (Embretson & Reise, 2000). The difficulty parameter shifts the curve from left to right as the item criterion becomes more severe and it represents the point on the continuum at which there is a 50% chance of the criterion being present. The discrimination parameter indicates how steep the slope of the curve is at its steepest point. Item information curves were also generated to indicate the point along the latent-trait continuum that an item is most reliable or conveys the most information. The discrimination parameter is represented by the height of the peak (higher curve = greater information and criterion discrimination) and the difficulty parameter by the location of the curve. All IRT models were analyzed using MPlus statistical software (Muthén & Muthén, 2007), which estimates item parameters via a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors using a numerical integration algorithm. To compare the relative fit of different IRT models (nested and non-nested) we used the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Rupp & Templin, 2010); models with lower BIC and AIC are preferred.

Finally, to test the discriminant validity of scores for each criteria set, participants were categorized by number of criteria endorsed. The following three groups were formed for the four item criteria set: those who endorsed no symptoms (low risk); those who endorsed 1 symptom (moderate risk); and those who endorsed 2 or more symptoms (high risk), reflecting the DSM-5 symptom threshold. The following groups were formed for the nine item criteria set: those who endorsed no symptoms (low risk); those who endorsed between 1 and 3 symptoms (moderate risk); and those who endorsed four or more symptoms (high risk), consistent with Frick and Moffitt (2010). Next, hierarchical multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the validity of the four and nine item criteria sets relative to aggression and delinquency.

Results

Testing the Reliability of the Criteria Sets and Prevalence of Significant CU Traits

Based on the item-to-total scale correlations, findings indicated that item 6 from the four item criteria set and item 13 from the nine item criteria were the least discriminating (Table 1). Overall, Cronbach’s alphas were .46 for the four item criteria set and .73 for the nine item criteria set. The PSI was .67 for the four item set and 2.10 for the nine item set. These findings indicate that increasing the number of items in the nine item set resulted in an internally consistent scale. In this incarcerated adolescent sample, the probability of endorsement for each item ranged from 9.8% to 15.4% for the four item set and from 6.4% to 21.7% for the nine item set (Table 1). The overall prevalence of those endorsing > 2 CU symptoms for the four item set (i.e., DSM-5 CU specifier criteria) was 14.2% with prevalence estimates of 8.8% and 15.8% for girls and boys, respectively. Prevalence estimates did not differ significantly across gender, χ2(2, N = 643) = 5.17, p = .08.

Table 1.

Item Response Theory Parameters for Four and Nine Item Criteria Sets

| Four item criteria set | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item-total scale correlation | Cronbach’s α if item deleted | % Endorsement | Difficulty | SE | Discrimination | SE | |

| 3) I care about how well I do at school or work | 0.303 | 0.359 | 9.8 | 2.617 | .15 | 0.937 | .19 |

| 5) I feel bad or guilty when I do something wrong | 0.328 | 0.321 | 15.3 | 1.297 | .21 | 1.368 | .40 |

| 6) I do not show my emotions to others | 0.095 | 0.543 | 13.7 | 4.679 | .22 | 0.236 | .12 |

| 8) I am concerned about the feelings of others | 0.346 | 0.299 | 15.4 | 1.356 | .23 | 1.174 | .33 |

| Nine item criteria set | |||||||

| Item-total scale correlation | Cronbach’s α if item deleted | % Endorsement | Difficulty | SE | Discrimination | SE | |

| 1) I express my feelings openly | 0.380 | 0.709 | 21.7 | 1.264 | .11 | 0.787 | .12 |

| 3) I care about how well I do at school or work | 0.405 | 0.703 | 9.8 | 1.947 | .20 | 0.933 | .15 |

| 5) I feel bad or guilty when I do something wrong | 0.423 | 0.699 | 15.3 | 1.526 | .15 | 0.934 | .14 |

| 8) I am concerned about the feelings of others | 0.442 | 0.695 | 15.4 | 1.387 | .13 | 1.108 | .17 |

| 13) I easily admit to being wrong | 0.285 | 0.727 | 19.7 | 1.802 | .26 | 0.541 | .09 |

| 15) I always try my best | 0.367 | 0.711 | 6.4 | 2.174 | .23 | 1.043 | .18 |

| 16) I apologize to persons I hurt | 0.469 | 0.691 | 11.9 | 1.488 | .13 | 1.394 | .24 |

| 17) I try not to hurt others’ feelings | 0.463 | 0.695 | 8.7 | 1.680 | .14 | 1.484 | .27 |

| 24) I do things to make others feel good | 0.447 | 0.694 | 14 | 1.511 | .14 | 1.047 | .15 |

IRT Analyses

Four item criteria set.

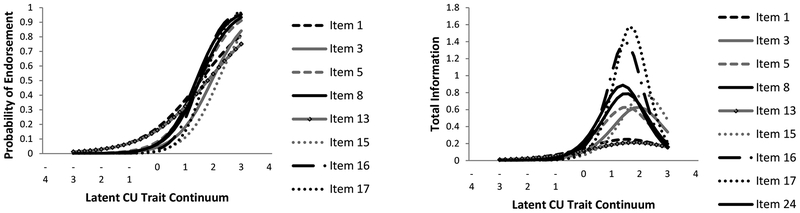

The IRT analysis for the four item criteria set is shown in Table 1. The items were rank ordered from lowest to highest for the difficulty parameter in the following order: item 5, item 8, item 3 and item 6. The criterion that demonstrated the greatest difficulty was item 6, “I do not show my emotions to others,” meaning that higher levels of the latent CU trait are necessary in order to endorse it. For the discrimination parameters, the items were rank ordered from lowest to highest in the following order: item 6, item 3, item 8, and item 5, suggesting that item 5 (“I feel bad or guilty when I do something wrong”) better discriminated adolescents along the CU continuum. The ICCs for the four item criteria set are plotted in Figure 1a and the item information curves are plotted in Figure 1b. Overall, the items provided the greatest amount of information towards the higher end of the CU continuum, indicating that they have a low probability of endorsement across the sample, but are more likely to be endorsed (i.e., higher reliability) among those who possess higher levels of the underlying CU trait. Therefore, all criteria contributed information within the more severe range of the continuum. Item 5 provided the most information and item 6 provided the least amount of information. A post-hoc IRT analysis was performed substituting item 6 with item 1 (“I express my feelings openly”). Based on the BIC (changed from 2034 to 1899) and AIC (changed from 2003 to 1908) model fit indices, the revised model better fit the data compared with the original model. Findings suggested that item 1 had lower difficulty (Dif. = 1.294, SE = .17) and higher discrimination (Dis =.768, SE = .14) than item 6. Moreover, the overall Cronbach’s alpha increased from .461 (items 3,5,6,8) to .591 (items 1,3,5,8).

Figures 1.

(a) Item characteristic curves and (b) Item information curves for the four item criteria set.

Nine item criteria set.

The IRT analysis for the nine item criteria set is also shown in Table 1. Items were rank ordered from lowest to highest for the difficulty parameter in the following order: item 1, item 8, item 16, item 24, item 5, item 17, item 13, item 3, and item 15. Thus, higher levels of the latent CU trait were necessary in order to endorse item 15, “I [do not] always try my best.” For the discrimination parameter, the items were rank ordered from lowest to highest in the following order: item 13, item 1, item 3, item 5, item 15, item 24, item 8, item 16 and item 17, suggesting that item 17 (“I try not to hurt others’ feelings”) best discriminated adolescents along the CU continuum. Figure 2 displays ICCs for each of the items in the nine item criteria set, along with item information curves. Similar to the four item criteria set, items from the nine item set provided the greatest amount of information towards the higher end of the CU latent-trait continuum, meaning that they have a low probability of endorsement across the sample, but are more likely to be endorsed among those with greater levels of CU traits. The items providing the greatest amount of information were items 16 and 17; Items 1 and 13 provided the least amount of information across the CU latent-trait continuum. Additionally, item 13 had a lower item to total scale correlation than item 1. Removing item 13 did not influence the scale’s Cronbach’s alpha (Table 1), suggesting that this item is especially problematic. Furthermore, removing item 13 resulted in better fit of the IRT model based on the BIC (changed from 3995 to 3356) and AIC (changed from 3920 to 3337) model fit indices, and did not change the difficulty and discrimination parameters of the remaining eight items.

Figures 2.

(a) Item characteristic curves and (b) Item information curves for the nine item criteria set.

Testing the Discriminate Validity of the Criteria Sets1

A series of hierarchical multinomial logistic regressions (MLR) were conducted. The first MLRs compared groups formed with the four item criteria set on total aggression and total delinquency scores using data from the Southeastern (Table 2) and Southwestern (Table 3) samples. Additional MLRs were conducted to compare these groups on proactive/reactive aggression and property/violent delinquency using data from the Southeastern sample (Table 2) and proactive/reactive aggression using data from the Southwestern sample (Table 3). Analyses were repeated for groups of youth formed using the nine item criteria set. The low, moderate, and high-risk groups identified based on the two methods were similar, with agreement ranging from approximately 68% for both the low (68.2%) and moderate (68.4%) risk groups to 73% for the high-risk groups. All analyses controlled for age, gender (1 = male; 2 = female), and race/ethnicity (dummy-coded to represent Black or Hispanic youth compared to White youth). Tables 2 and 3 incorporate odd ratios (OR) to compare groups, which reflect the odds likelihood of being in one group over the other on the basis of the level of the independent variable.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis: Southeastern Sample

| Group comparisons based on Odds ratios (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four item criteria set | Nine item criteria set | |||||

| 3 vs 1 | 2 vs 1 | 3 vs 2 | 3 vs 1 | 2 vs 1 | 3 vs 2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender | 3.25* (1.14–9.21) |

1.06 (.48–2.32) |

.95 (.43–2.08) |

11.47** (1.45–90.76) |

1.28 (.68–2.41) |

8.96** (1.12–71.47) |

| African American | 2.53** (1.21–5.27) |

1.03 (.55–1.94) |

.97 (.52–1.83) |

4.27** (1.60–11.34) |

1.50 (.91–2.48) |

2.84* (1.06–7.61) |

| Hispanic | 1.97 (.70–5.55) |

1.72 (.74–4.01) |

.58 (.25–1.36) |

5.60** (1.79–17.46) |

1.14 (.53–2.44) |

4.91** (1.53–15.74) |

| Age | .84 (.66–1.06) |

.88 (.71–1.09) |

1.13 (.92–1.40) |

.98 (.74–1.29) |

1.05 (.89–1.25) |

.95 (.80–1.13) |

| Step 2 a | ||||||

| Total Overt Aggression | 1.08** (1.02–1.12) |

1.02 (.99–1.05) |

1.03 (.99–1.07) |

1.06** (1.03–1.10) |

1.04* (1.02–1.07) |

1.03 (.99–1.06) |

| Total Delinquency | 1.03 (.98–1.08) |

1.01 (.96–1.04) |

1.03 (.97–1.09) |

1.03 (.98–1.08) |

1.01 (.97–1.03) |

1.03 (.98–1.08) |

| Step 2 b | ||||||

| Proactive Aggression | 1.11** (1.05–1.18) |

1.10* (1.03–1.17) |

1.04 (.97–1.12) |

1.07* (1.02–1.12) |

1.06* (1.01–1.11) |

1.02 (.94–1.11) |

| Reactive Aggression | .99 (.93–1.04) |

.94* (.90-.99) |

1.02 (.97–1.08) |

1.01 (.94–1.07) |

.98 (.95–1.02) |

1.01 (.95–1.08) |

| Property Delinquency | .98 (.86–1.12) |

.91 (.81–1.02) |

1.08 (.93–1.25) |

.95 (.82–1.10) |

.98 (.89–1.07) |

.97 (.84–1.13) |

| Violent Delinquency | 1.32** (1.10–1.60) |

1.16 (.97–1.38) |

1.11 (.89–1.38) |

1.48** (1.19–1.85) |

1.06 (.92–1.23) |

1.41** (1.11–1.80) |

Note:

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

Group 1 = low CU; Group 2 = moderate CU; Group 3 = high CU.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analysis: Southwestern Sample

| Group comparisons based on Odds ratios (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four item criteria set | Nine item criteria set | |||||

| 3 vs 1 | 2 vs 1 | 3 vs 2 | 3 vs 1 | 2 vs 1 | 3 vs 2 | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender | 2.62 (.68–10.05) |

.98 (.40–2.37) |

2.68 (.62–11.56) |

3.25 (.70–15.09) |

1.30 (.58–2.93) |

2.49 (.52–11.89) |

| African American | 4.11 (.48–34.96) |

1.01 (.35–2.89) |

4.09 (.43–39.22) |

2.50 (.27–22.87) |

1.47 (.57–3.84) |

1.69 (.18–16.33) |

| Hispanic | 5.05 (.63–40.71) |

1.26 (.47–3.36) |

4.00 (.45–35.78) |

4.88 (.60–40.07) |

1.72 (.69–4.25) |

2.85 (.33–24.52) |

| Age | 1.17 (.82–1.68) |

.98 (.40–2.37) |

1.11 (.84–1.46) |

1.12 (.74–1.69) |

.98 (.77–1.25) |

1.14 (.75–1.74) |

| Step 2 a | ||||||

| Total Overt Aggression | 3.17** (1.82–5.52) |

1.21 (.69–2.12) |

2.33** (1.26–4.29) |

3.49** (1.91–6.36) |

1.30 (.85–1.98) |

2.69** (1.48–4.88) |

| Total Delinquency | 1.09 (.82–1.46) |

1.14 (.90–1.44) |

.96 (.69–1.34) |

1.25 (.87–1.78) |

1.05 (.86–1.29) |

1.18 (.83–1.70) |

| Step 2 b | ||||||

| Proactive Aggression | 2.68* (1.08–7.31) |

1.09 (.54–2.22) |

1.89 (.71–5.05) |

2.66 (.97–7.27) |

1.10 (.54–2.23) |

2.43 (.91–6.48) |

| Reactive Aggression | 1.08 (.54–2.17) |

1.25 (.76–2.08) |

.83 (.37–1.85) |

.83 (.36–1.94) |

1.25 (.75–2.07) |

.67 (.28–1.56) |

Note:

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

Group 1 = low CU; Group 2 = moderate CU; Group 3 = high CU.

Four item criteria set.

Main effects for demographic variables in the MLR for the Southeastern sample approached significance, χ2(8, N = 441) = 14.30, p = .07. Boys and Black youth were somewhat more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared with the low CU group. Including main effects for total aggression and delinquency in step 2a of the MLR improved model fit, χ2(4, N = 441) = 15.49, p < .01. Adolescents with higher overt aggression scores were more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared to the low CU group. Step 2b of the MLR also improved model fit, χ2(8, N = 441) = 26.52, p < .001. Youth scoring higher on proactive aggression were more likely to be classified in the high and moderate CU groups compared with the low CU group. Moreover, youth with higher scores on violent delinquency were more likely to be classified in the high CU compared to the low CU group, and children with lower scores on reactive aggression were more likely to be classified in the moderate than the low CU group.

Results for MLR models for the Southwestern sample are presented in Table 3. Main effects for demographic variables were not significant, χ2(8, N = 228) = 7.99, p = .43. Step 2a improved model fit, χ2(4, N = 228) = 13.02, p = .01, suggesting that youth with higher scores on overt aggression were more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared to the low and moderate CU groups. Including main effects for proactive and reactive aggression in step 2b of MLR also improved model fit, χ2(4, N = 228) = 9.48, p = .05. Youth who scored higher on proactive aggression were more likely to be in the high CU group compared to the low CU group.

Nine item criteria set.

MLR analyses described above were repeated for the nine item criteria set, separately for each sample. Step 1 of the MLR in the Southeastern sample was significant, x2(8, N = 441) = 23.99, p < .01. Boys and minority youths (Black, Hispanic) were more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared to the moderate and low CU groups. Youth scoring high on overt aggression were more likely to be classified in the high and moderate CU groups compared to the low CU group (step 2a; χ2(4, N = 441) = 15.01, p < .01). Youth scoring high on proactive aggression were more likely to be classified in the high and moderate CU groups compared to the low CU group (step 2b; χ2(8, N = 441) = 21.62, p < .01). Step 2b findings also suggested that youth scoring high on violent delinquency were more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared to the low and moderate CU groups.

With respect to the Southwestern sample (see Table 3), main effects for demographic variables were not significant, χ2(8, N = 228) = 10.03, p = .26. Including main effects for overt aggression and delinquency in step 2a of the MLR improved model fit, x2(4, N = 228) = 14.23, p < .01. Youth with higher scores on overt aggression were more likely to be classified in the high CU group compared to the low and moderate CU groups. Step 2b did not improve the fit of the model χ2(4, N = 228) = 7.71, p = .10.

Discussion

The present study provides important information on using a self-report measure of CU traits to identify a subgroup of youth at risk for severe and aggressive antisocial behavior. This study contributes three key findings relevant to understanding the importance of assessing CU traits in general, and use of the DSM-5 specifier “with Limited Prosocial Emotions” for CD, specifically. First, one in seven (14%) adolescent offenders endorsed significant CU traits, based on two or more of the four items that most closely approximate the criteria used in the specifier for CD (Frick & Moffitt, 2010). This suggests that even among youth exhibiting behaviors severe enough to warrant arrest and confinement in correctional residential facilities, only a minority is at risk for the pattern of severe and stable antisocial behavior associated with these traits (Frick & White, 2008; McMahon et al., 2010). Second, the psychometric properties of the two item sets indicated that only the nine item CU criteria set showed acceptable internal consistency using adolescent self-report. Specifically, the “I do not show my emotions to others” item in the four item criteria set showed particularly poor psychometric properties. Results from IRT analyses suggested that while youth who endorsed this item tended to fall in the higher end of the CU latent-trait continuum, this item was poor at discriminating those youth who similarly endorsed other items comprising the four item criteria set. Third, although the nine item criteria set provided more information than the four item set, both sets demonstrated comparable ability in identifying juvenile offenders at risk for total and proactive aggression and violent delinquency, with similar odds ratios.

The overall prevalence of significant CU traits (i.e., endorsing two or more criteria) was somewhat lower among incarcerated girls compared with boys. Although not significant, this trend is consistent with gender differences in self-reported psychopathy scores reported in prior research (Miller, Watts, & Jones, 2011). Also, although differences were not consistent or significant across regional samples, youth self-identifying as Black or Hispanic were more likely to endorse significant CU traits than were White youth. At the item level, only a minority of incarcerated boys and girls endorsed items comprising the two CU criteria sets (roughly < 20%), suggesting that these traits are not normative among adolescents and their presence identifies a distinct subsample of antisocial youth, similar to findings in community samples for children and adolescents with CD (Kahn et al., 2012; Rowe et al., 2010).

Item 6 of the ICU, intended to capture the ‘shallow or deficient affect’ criterion of the DSM-5 specifier, functioned poorly in the IRT analysis.. Substituting item 6 with the better performing item 1 (“I express my feelings openly”) from the nine item criteria set improved model fit, but did not improve upon the identification of youths with problematic outcomes nor did it result in a scale that was as reliable as the nine item criteria set—appearing the most viable option for assessing the youth’s self-reported CU traits. Items tapping unemotionality may require a change in wording to clarify that the youth is capable of turning emotions on and off at will and/or using emotions to get what he or she wants from others, rather than failing to express emotions at all (see Frick & Moffitt, 2010). Others suggest the affective deficit is specific to the experience of sadness and fear (Pardini, Lochman, & Frick, 2003; Stevens, Charman, & Blair, 2001). On the other hand, family observational research suggests that antisocial children high on CU traits are more expressive of negative affect within the family environment than those low on CU traits (Pasalich et al., 2012). It is possible that levels of emotionality in children high on CU traits differ across development, with fluctuations relating to factors such as exposure to particular environmental influences (Kosson, Cyterski, Steuerwald, Neumann, & Walker-Matthews, 2002; Pasalich et al., 2012). An important goal for future research is to refine the indicators of the deficient affect component of CU traits.

Whether using four or nine items, the reliability of scores for the CU specifier criteria sets was greatest at higher levels of the CU latent-trait continuum. This suggests that when adolescents rate a CU criterion as present, this rating is more reliable than when traits are rated as absent. Although the greater number of items in the nine item criteria set provided more information, criteria sets were comparable in terms of identifying antisocial youth at risk for unprovoked aggression employed to achieve a goal (i.e., proactive) and more severe violent delinquent acts, such as engaging in gang fights or beating up or mugging others. Results were similar for an eight item criteria set that removed item 13 (“I easily admit to being wrong”) that functioned poorly in the IRT analysis. Compared with incarcerated youth (boys and girls) reporting one or no symptom(s) on the four item criteria set, youth who self-reported two or more CU symptoms showed significantly greater overt—particularly proactive—aggression, as well as violent delinquency. For the nine item criteria set, youth endorsing four or more symptoms, compared with youth endorsing no symptoms, showed significantly greater total aggression, violent delinquency, and proactive aggression (using the nine item set in the Southeastern sample, eight item set in the Southwestern sample). Youth falling in the moderate risk range (endorsing at least one symptom from the four item set; between 1 and 3 symptoms from the nine item set) scored significantly higher on aggression than youth endorsing no symptoms. This effect was specific to proactive aggression only for the Southeastern sample. Across criteria sets, effect sizes ranged from small for the Southeastern samples to large for the Southwestern samples (Wickens, 1989). Only for the four item set, Southeastern youth endorsing at least one CU symptom showed significantly less reactive aggression compared with youth endorsing no symptoms; however, this effect, which was small in size, was not consistent across samples. Together, these findings suggest that high risk thresholds for both criteria sets (endorsing two or more criteria from the four item set; four or more criteria from the nine item set) are effective in identifying a unique subgroup of incarcerated adolescents that show high levels of aggression and violent delinquency, but that the four item set might more consistently distinguish youth at greater risk for proactive aggression, notwithstanding reliability issues. Future research is necessary to confirm whether these findings generalize to other incarcerated samples, as well as to non-incarcerated youth.

These findings must be interpreted in light of several important study limitations. First, CU traits were assessed solely based on self-report, although the DSM-5 criteria explicitly recognizes the importance of carefully considering multiple sources of information including self- and informant report (e.g., parents, teachers, peers, other family members) from sources who have known the child for a significant period of time when evaluating the specifier (Frick & Moffitt, 2010). In addition, the external validators were all self-reported as well, which could have inflated validity estimates due to shared method variance. While caregiver report is reliable for some forms of psychopathology (Verhulst & van der Ende 1991), existing research suggests that antisocial attitudes and behavior are more reliably assessed using self-report methods, especially among adolescents with severe conduct problems whose families may have had limited recent contact as a result of out-of-home placement (Jolliffe et al., 2003). Second, although all youth included in the present study were arrested and, in most cases adjudicated delinquent, we did not include a formal assessment of CD. However, research with juvenile justice populations suggests that approximately half of juvenile justice-involved youth meet criteria for a current disruptive behavior disorder (i.e., CD, ODD; Garland et al., 2001; Teplin et al., 2002) and this likely underestimates those with a lifetime prevalence of these disorders, providing some confidence that a large majority of incarcerated youths in the present study may have met criteria for CD at some point in their lives. Finally, since different samples were combined for the purposes of the present study, measures of external criteria were not consistent across region and we were unable to disaggregate delinquency into property and violent forms for Southwestern samples as there was an insufficient number of items within the scale to do so. Nonetheless, in combining these samples we were able to examine the CU specifier in a larger sample of incarcerated youth than previously studied with a heterogeneous ethnic composition comprising roughly equal proportions of Black, Hispanic, and White youth.

Within the context of these strengths and limitations, our results provide some additional support for the DSM-5 criteria developed to define significant levels of CU traits in forensic samples of adolescents. This designation could be critical for identifying a unique group of antisocial youths who show more severe current impairment and who are at risk for more severe future impairment. With respect to treatment, research suggests that antisocial youths with CU traits may benefit less from traditional behavioral approaches and may need more intensive, comprehensive and specialized interventions that are tailored to their unique emotional, cognitive, and motivational styles (Frick, 2012; Hawes & Dadds, 2005; Waschbusch et al., 2007). For example, in a study of 177 clinic-referred children, those with CU traits who received an individualized and comprehensive modular intervention—involving medication for ADHD, cognitive-behavioral treatment, parent management training, school consultation, peer relationship development, and crisis management—evinced similar rates of improvement to other children with CD (Kolko & Pardini, 2010). Similarly, adolescent offenders with CU traits treated with an intensive intervention that used reward-oriented approaches, targeted the self-interests of the adolescent, and taught empathy skills were less likely to recidivate in a 2-year follow-up period than offenders with these traits who underwent a standard treatment program in the same correctional facility (Caldwell et al., 2006). Pairing this promising line of treatment research with findings from the present study, and other studies supporting the reliability and clinical utility of assessing CU traits among adolescents using self-report instruments, holds promise for reducing the significant public health burden of this unique subpopulation of youth.

Acknowledgments

Partial funding for this study was provided to Elizabeth Cauffman, Ph.D. from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH01791-01A1) and from the Center for Evidence-Based Corrections at the University of California, Irvine.

Footnotes

The IRT analysis suggested that replacing item 6 with item 1 in the four criteria set and deleting item 13 in the nine criteria set resulted in better model fit. In addition to the multinomial logistic regressions shown in Tables 2 and 3, we also conducted multinomial logistic regressions to compare groups identified using the revised four- and eight-item criteria sets on measures of aggression and delinquency. The findings were mostly consistent with the results shown in Tables 2 and 3. Only one difference emerged; when comparing groups based on the newly created 8-item criteria set (Southwestern sample), youth in the high CU group scored significantly higher on proactive aggression compared with youth in the low CU group (OR = 2.90, p < .05). Ultimately, removing or substituting an individual criterion from either criteria set did not alter the original findings reported in Tables 2 and 3.

References

- Byrd AL, Loeber R, & Pardini DA (2012). Understanding desisting and persisting forms of delinquency: The unique contributions of disruptive behavior disorders and interpersonal callousness. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 53, 371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02504.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell M, Skeem J, Salekin R, & Van Rybroek G (2006). Treatment response of adolescent offenders with psychopathy features: A 2-year follow-up. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 33, 571–596. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, & Ageton S (1980). Reconciling ethnicity and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 45, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, & Reise S (2000). Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Sasagawa S, & Frick PJ (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in community sample of adolescents. Assessment, 13, 454–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Frick PJ, & Georgiou S (2009). Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ (2004). The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. New Orleans: UNO. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ (2012). Developmental pathways to Conduct Disorder: Implications for future directions in research, assessment, and treatment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41, 378–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Bodin SD, & Barry CT (2000). Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in community and clinic-referred samples of children: Further development of the Psychopathy Screening Device. Psychological Assessment, 12, 382–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Hare RD (2001). The Antisocial Process Screening Device. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Moffitt TE (2010). A proposal to the DSM-V childhood disorders and the ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders work groups to include a specifier to the diagnosis of conduct disorder based on the presence of callous-unemotional traits. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & Nigg JT (2012). Current issues in the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Annual Review Of Clinical Psychology, 877–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, & White SF (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 359–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, & Aarons GA (2001). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youth across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes DJ, & Dadds MR (2005). The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Esbensen FA, & Weiher AW (1991). Are there multiple paths to delinquency? Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 82, 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe D, Farrington DP, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Hill KG, & Kosterman R (2003). Predictive, concurrent, prospective and retrospective validity of self-reported delinquency. Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health, 13, 179–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RE, Frick PJ, Youngstrom E, Findling RL, & Youngstrom JK (2012). The effects of including a callous–unemotional specifier for the diagnosis of conduct disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Frick PJ, Skeem J, Marsee MA, Cruise K, Munoz LC, et al. (2008). Assessing callous-unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Journal of the International Association of Psychiatry and Law, 31, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, & Pardini DA (2010). ODD dimensions, ADHD, and callous-unemotional traits as predictors of treatment response in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 713–725. doi: 10.1037/a0020910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson D, Cyterski T, Steuerwald B, Neumann C, & Walker-Matthews S (2002). The reliability and validity of the psychopathy checklist: Youth version (PCL: YV) in non-incarcerated adolescent males. Psychological Assessment, 14, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jones SM, Henrich CC, & Hawley PH (2003). Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Marsee MA, Barry CT, Childs KK, Frick PJ, Kimonis ER, Muñoz LC, et al. (2011). Assessing the forms and functions of aggression using self-report: Factor structure and invariance of the Peer Conflict Scale in youths. Psychological Assessment, 23, 792–804. doi: 10.1037/a0023369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Witkiewitz K, Kotler JS, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2010). Predictive validity of callous-unemotional traits measured in early adolescence with respect to multiple antisocial outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 752–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Watts A, & Jones SE (2011). Does psychopathy manifest divergent relations with components of its nomological network depending on gender? Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 564–569. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th edition) (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally & Bernstein (1994). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw Hill, 3rd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, McMorris BJ, & Potenza MT (2002). Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance: I. Item response theory scaling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Lochman JE, & Frick PJ (2003). Callous/unemotional traits and social-cognitive processes in adjudicated youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Stepp S, Hipwell A, Stouthamer-Loeber M, & Loeber R (2012). The clinical utility of the proposed DSM-5 callous-unemotional subtype of conduct disorder in young girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich D, Dadds MR, Vincent LC, Cooper FA, Hawes DJ & Brennan J (2012). Emotional communication in families of conduct-problem children with high versus low callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41, 302–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose A, Bijttebier P, Decoene S, Claes L, & Frick PJ (2010). Assessing the affective features of psychopathy in adolescence: A further validation of the inventory of callous and unemotional traits. Assessment, 17, 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Maughan B, Moran P, Ford T, Briskman J, & Goodman R (2010). The role of callous and unemotional traits in the diagnosis of conduct disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 51, 688–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp A, & Templin J (2010). Diagnostic Measurement: Theory, Methods, and Applications. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D, Charman T, & Blair RJR (2001). Recognition of emotion in facial expressions and vocal tones in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 16, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, & Mericle AA (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 59, 1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, & van der Ende L (1991). Assessment of child psychopathology: relationships between different methods, different informants and clinical judgment of severity. Acta Psychiatria Scandanavia, 84, 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Carrey NJ, Willoughby MT, King S, & Andrade BF (2007). Effects of methylphenidate and behavior modification on the social and academic behavior of children with disruptive behavior disorders: The moderating role of callous/unemotional traits. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36, 629–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens T (1989). Multiway Contingency Tables Analysis for the Social Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wright BD, & Stone MH (1999). Measurement essentials. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range. [Google Scholar]