Abstract

Background/Purpose:

The main purpose of this study was to extend our previously reported showing potent neuroprotective effect of valproic acid (VPA) in primary midbrain neuro-glial cultures to investigate whether VPA could protect dopamine (DA) neurons in vivo against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced neurodegeneration and to determine the underlying mechanism.

Methods:

Male adult rats received a daily intraperitoneal injection of VPA or saline for two weeks before and after injection of 5, 10, or 15 μg of 6-OHDA into the brain. All rats were evaluated for motor function by rotarod performance. Brain samples were prepared for immunohistochemical staining and for determination of levels of dopamine, dopamine metabolites, and neurotrophic factors.

Results:

6-OHDA injection showed significant and dose-dependent damage of dopaminergic neurons and decrease of striatal dopamine content. Rats in the VPA-treated group were markedly protected from the loss of dopaminergic neurons and showed improvements in motor performance, compared to the control group at the moderate 6-OHDA dose (10 μg). VPA-treated rats also showed significantly increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in the striatum and substantia nigra compared to the levels in control animals.

Conclusion:

Our studies demonstrate for the first time that VPA exerts neuroprotective effects in a rat model of 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson’s disease (PD), likely in part by up-regulation BDNF.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, 6-hydroxydopamine, Parkinson disease, substantia nigra, valproic acid

Introduction

Valproic acid (VPA; 2-propylpentanoic acid) is a simple eight-carbon branched-chain fatty acid and has been frequently used for the treatment of seizures and bipolar mood disorder, as well as for the prophylaxis of migraine.1,2,3 Recent preclinical evidence shows that VPA is neuroprotective and neurotrophic against toxin-elicited neurodegeneration through different mechanisms.4,5,6 Earlier in vitro studies from our laboratories demonstrates that VPA provides neuroprotection against inflammation-related dopaminergic neurodegeneration by: 1) increasing expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and increase of their transcripts in astrocytes in a time-dependent manner;7,8 2) decreasing neuroinflammation through the reduction of release of proinflammatory factors from microglia (Peng et al. 2005).9 VPA was also reported to increase the expression of endogenous α-synuclein protein in primary brain neurons by HDAC inhibition, and thus exhibit neuroprotective effects against glutamate excitotoxicity via increasing the expression of Bcl-2.10 In a subsequent study, it was shown that treatment with VPA in a rat model of PD increased endogenous α-synuclein expression in the substantia nigra and striatum,11 and this action was associated with amplification of histone acetylation in the substantia nigra, indicating enhanced HDAC inhibition.12 Despite these reports, the roles of neurotrophins in VPA-induced beneficial effects in an animal model of PD have not been reported. The present study was undertaken to test if VPA pretreatment can alleviate 6hydroxydopamine-(6-OHDA)-induced dopaminergic neuronal damage and behavioral deficits, and whether these effects are associated with up-regulation of BDNF in the midbrain.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats from a local breeding colony (BioLasco Taiwan Co., Taipei, Taiwan) weighting 200–250 grams at the beginning of treatment were used. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Defense Medical Center according to the Helsinki recommendations and were performed in adherence to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the treatment of animals. All rats were housed in the Laboratory Animal Center of the National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan, which has been certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) since 2007, with temperature/humidity control, a 12:12 h light/dark cycle, and access to food and water ad libitum.

VPA treatment

Rats were pretreated either with VPA at 100 mg/kg, or with physiological saline (0.9% sodium chloride; control group), daily for 2 weeks. Both formulations were given by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at a dose volume of 0.4 mL/kg in the lower quadrant on the right side of the rat’s abdomen. Then rats from each group received a local intracranial injection of 5 μg of 6-OHDA as the low-dose group, 10 μg of 6-OHDA as the moderate-dose group, or 15 μg of 6-OHDA as the high-dose group. After the intracranial injections, all rats were continued on the regimen of VPA or saline i.p. injections for a further two weeks and then sacrificed to obtain brain tissue for further assays.

Intracranial injection of 6-OHDA

The animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. They received injections of 4 μL of vehicle containing 6-OHDA hydrobromide (5, 10, or 15 μg free base) (Sigma Chemicals, Perth, Western Australia) into the right-side medial forebrain bundle (MFB) at the following two sites: −4 mm, ± 0.8 mm, and −8 mm; and −4.4 mm, ± 1.2 mm, and −7.8 mm; anterior/posterior, medial/lateral, and dorsal/ventral from the bregma, respectively.13 During each injection procedure, the needle was left in place for 2 min and then slowly retracted. After 6-OHDA injection, all rats received the same treatment regimens, VPA or saline, as previously for a further 2 weeks and were then sacrificed for the brain tissue studies.

Rat motor function assessment

A rotarod machine (Med Associates, Inc., ENV-576, USA) with automatic timers and falling sensors was used to assess the motor function of the rats. Before the experiment started, every rat was placed on an 8-cm-diameter rotarod and trained until it could stay on the rod for 5 min at the lowest speed (2.5 rpm). All rats were transported to the testing room 1 h before testing. The rotarod started at 2.5 rpm and accelerated to 25 rpm over 5 min during each test session. The retention time of each rat on the rotarod was recorded as an indicator of motor function. If the rat had not fallen from the rod by the end of test, it was removed from the rod and rested for 10 min before the next test. All rats were tested in triplicate for each assay and rested for 10 min between tests. Each was assayed before intraperitoneal injection of VPA or saline, before local injection of 6-OHDA into the brain, and before sacrifice for sampling brain tissue.

Immunohistochemisty

The rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.), and perfused through the heart with cold saline. After perfusion, the brain was removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, then equilibrated with 30% sucrose for 3 days. Frozen coronal sections of the substantia nigra (SN), each of 35-μm thickness, were cut and processed free-floating for immunohistochemistry. Before immunostaining, all brain sections were washed and incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, then treated with blocking buffers containing 10% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and TBS for 2 h. Then brain sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a primary antibody solution containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100, with one of three antibodies: rabbit polyclonal antibody (Imgenex, Littleton, CO; 1:6,000) against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) for detection of dopaminergic neurons; mouse monoclonal antibody (Abd Serotec, Kidlington, UK; 1:2,000) against OX42 antigen for detection of microglia; and mouse monoclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:2,000) against NeuN antigen for detection of neurons. Both biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA; 1:2,000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA; 1:2,000) were as the secondary antibodies. After rinsing, the sections were incubated for 75 min at room temperature in peroxidase-conjugated avidin solution (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Finally, the immunostaining was visualized with a DAB substrate kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) to provide the chromogen. When assessing stained cells, a 10× objective lens was used for marking the nuclei and a 100× oil lens was used for counting cells. For counts of stained cells, the grid area was set at 16,900 μm2 (130 × 130 μm) and the counting frame area was set at 3,600 μm2 (60 × 60 μm). On average, nine sections from each animal were assessed. Stereological assessments were done by an individual blind to the treatment history.

Dopamine biochemistry

The rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.) and their hearts were perfused with cold saline. After perfusion, the brain was immediately removed from the skull, frozen in cold 2-methylbutane (Sigma Chemicals, Perth, Western Australia), and stored in a −80 °C freezer until use.14 Brain samples in each treatment group were collected from striatum, hippocampus, and SN by taking tissue punches in the corresponding areas. These tissues were submerged in 200 μL of antioxidant containing 0.4N perchlorate, 0.05% EDTA, and 0.01% bis-metabisulfite, and homogenized using the Microson ultrasonic cell disruptor (SjiaLab, Shanghai, China). Samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 45 min at 4 °C, supernatants were collected for high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, and the precipitated pellets were collected and resuspended in 200 μL of 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) by sonication, for measurement of total protein concentration by the Lowry method. Dopamine and its metabolites homovanillic acid (HVA) and 2–3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetic acid (DOPAC) were measured with an HPLC-ECD (electrochemical detector) system equipped with an LC-10AD pump (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), an ECD by ESA (Coulochem II, Houston, TX), and a stationary phase C18 column (Thermo, Hypersil gold, 150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5-μm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of 2 mM 1-octanesulfate (OSA), 80 mM sodium phosphate monobasic (NaH2PO4), and 10% acetonitrile (Sigma Chemicals, Perth, Western Australia), and was adjusted to pH 2.76 by using the H3PO4. Column temperature was set at 35 °C with the sample tray at 4 °C. Each sample was run for 12 min using a flow rate of 1 mL/min.15 The DA and HVA levels were expressed as ng/mg tissue protein and the ratio of [HVA]/[DA] was used as indices of DA activity.

Cytokine assay

The brain tissues punched from striatum, hippocampus, and substantia nigra were processed as described in the section on brain preparation for determination of dopamine biochemistry. The collected supernatants were assayed using the ELISA kits for TNF-α (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA) and IL-10 (Bender Medsystem, Vienna, Austria). The cytokine levels in the samples were calculated against the standard curves of each cytokine.

Neurotrophic factors analysis

Brain tissues punched from the regions of rat striatum and SN were homogenized with M-Per lysis buffer (Thermo, Waltham, MA) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and a phosphatase inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). SDS-PAGE and subsequent Western blotting were performed, followed by standard protocols.16 Membranes were incubated in blocking solution containing 5% defatted milk and 0.25% Tween 20 in TBS, and then incubated with the following four primary antibodies: mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 1:30,000), chicken anti-GDNF (Millipore, USA; 1:2,000), chicken anti-BDNF (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:2,000) and rabbit anti TH (Imgenex, Littleton, CO; 1:6,000) to detect the target proteins. Membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA; 1:5,000) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo, Waltham, MA). The densitometries of the immunoreactive bands were quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as averages with standard error of the mean. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used for multiple comparisons of groups. Statistical significance between two groups was assessed by paired or unpaired Student’s t-test, with Bonferroni’s correction. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

VPA protects dopaminergic neurons against 6-OHDA neurotoxicity

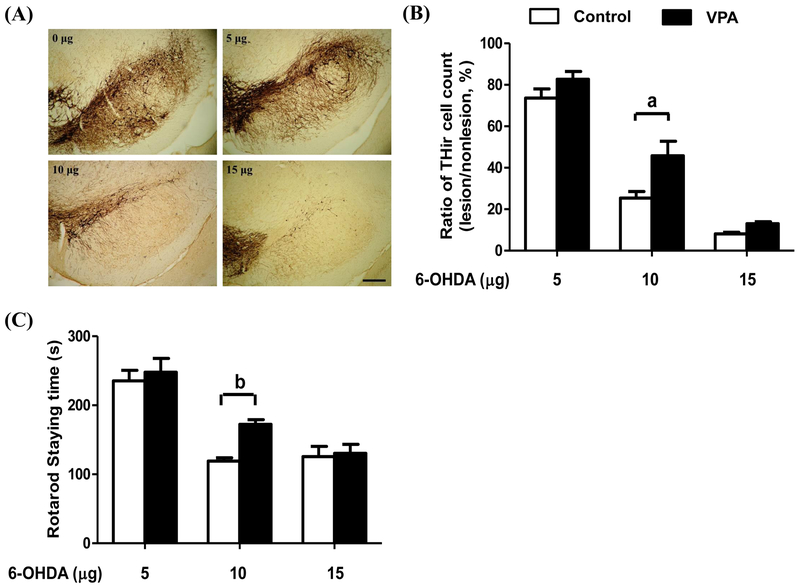

Figure 1 revealed the immunohistochemical analysis with dose-dependent reductions of nigral dopaminergic neurons after an intracranial injection of 6-OHDA. On the lesion side of the substantia nigra in the control group, there was a significant dose-dependent reduction of 26%, 75%, and 90% after an intracranial local injection of 5, 10, and 15 μg of 6-OHDA, respectively, compared with the non-lesion side (Fig. 1A and 1B). Pretreatment of VPA significantly reduced 6-OHDA-induced DA neurodegeneration in the moderate-dose group (10 μg) compared with those without treatment (p < 0.01), but no significant differences were seen in either low (5 μg)- or high (15 μg)-dose groups. Moreover, a significant improvement in rotarod retention time in the moderate-dose group was observed increasing from 119 s vehicle-treated group to 170 s in VPA-treated group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). Similar to the effects on DA neurodegeneration, VPA failed to improve the rotarod performance in the group injected with low- or the high-dose groups. Because the best neuroprotective effect of VPA was observed in rats treated with moderate dose of 6-OHDA, 10 μg of this toxin was used for the rest of this study.

Figure 1.

Tyrosine-hydroxylase immunoreactive (THir) cell counts in rat substantia nigra (A, B) and rotarod performance (C) after an intracranial local injection of different doses of 6-OHDA and valproic acid (VPA) treatment. Immunohistochemical staining of THir cells in substantia nigra (A) demonstrated that 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) induced dose-dependent neurotoxicity in the control group (□) and that the VPA group (■) showed significant protection of THir neurons against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity (B). Rotarod performance (C) demonstrated that VPA treatment (■) significantly improved motor function in the moderate-dose group receiving an intracranial injection of 10 μg of 6-OHDA, but no significant difference was seen at lower (5 μg) or higher (15 μg) doses. The ratio of THir cells was the total number of stained cells on the lesion side divided by those on the non-lesion side of same brain. Bar indicates 250 μm. Statistically significant differences between the groups were detected by one-way ANOVA. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean; n = 6 for each group; a, p < 0.01 compared to the control group.

6-OHDA selectively induces dopaminergic degeneration and increases microglia activation in substantia nigra of rat

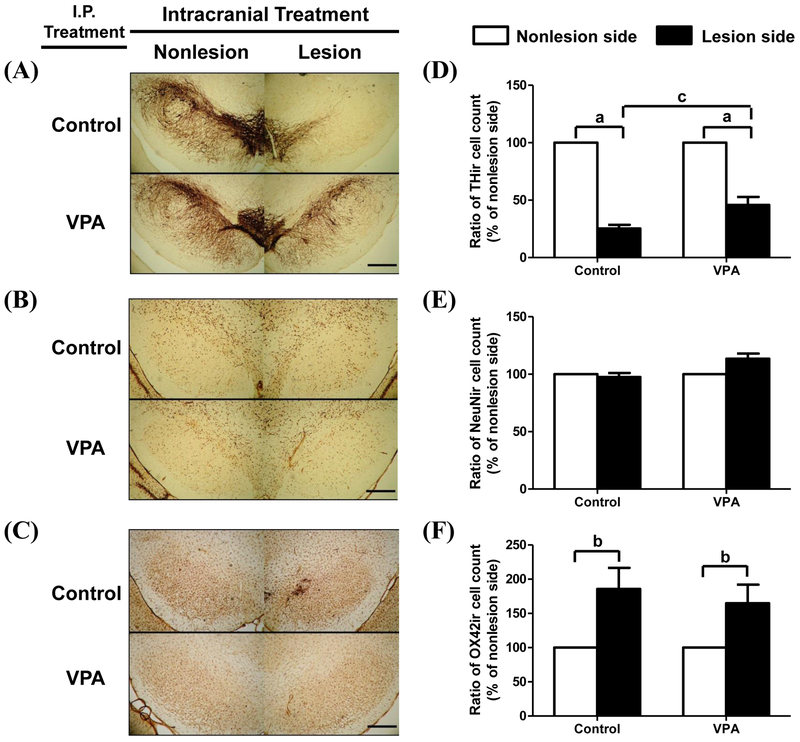

Figure 2 shows that the number of DA neurons in SNc of rat (Fig. 2A and 2D) was significantly reduced by 74.6% in the control group (p < 0.01) and 54.2% in the VPA group (p < 0.01) after intracranial injection of 10 μg of 6-OHDA. VPA treatment was significantly protective against the number of DA neurons loss by 20.4% compared with the control rats. Total neuron numbers within the SNc, defined as the number of nuclei positive for neuronal-nucleus protein (NeuN), was not significantly changed in either group (VPA or control) after intracranial injection of a dose of 10 μg of 6-OHDA (Fig. 2B and 2E). The activated microglia detected by OX42 immunostaining in the same SN region were significantly increased by 185.7% in the control group and 164.8% in the VPA group after intracranial injection of 10 μg of 6-OHDA.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for dopaminergic neurons, total neuron number, and microglia in rat substantia nigra. Cells staining by TH (A), NeuN (B), and OX42 (C) antibodies were detected at bilateral substantia nigra of saline-treated rats (i.p. injection pre- and post-6-OHDA injection) (upper panel, n = 5) or VPA-treated rats (100 mg/kg, i.p. pre-and post- 6-OHDA injection) (lower panel, n = 5). 6-OHDA was administered by intracranial local injection of 10 μg/4 μL at the right MFB. The cells staining with TH (D), NeuN (E), and OX42 (F) antibodies were expressed as the ratio the total cell numbers on the lesion side divided by those on the non-lesion side of same brain, respectively. Lesion side, intracranial injection of 6-OHDA; non-lesion side, intracranial injection of saline. □, control group, rats daily treatment with saline i.p. injected for 4 weeks; ■, VPA group, rats daily treatment with 100 mg/kg of VPA i.p. injected for 4 weeks. Bar indicates 250 μm. Statistically significant differences between groups were detected by one-way ANOVA. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean; n = 5 for each group; a, p < 0.01 compared to non-lesion side; b, p < 0.05 compared to the control group.

Intracranial local injection of 6-OHDA reduces striatal dopamine level

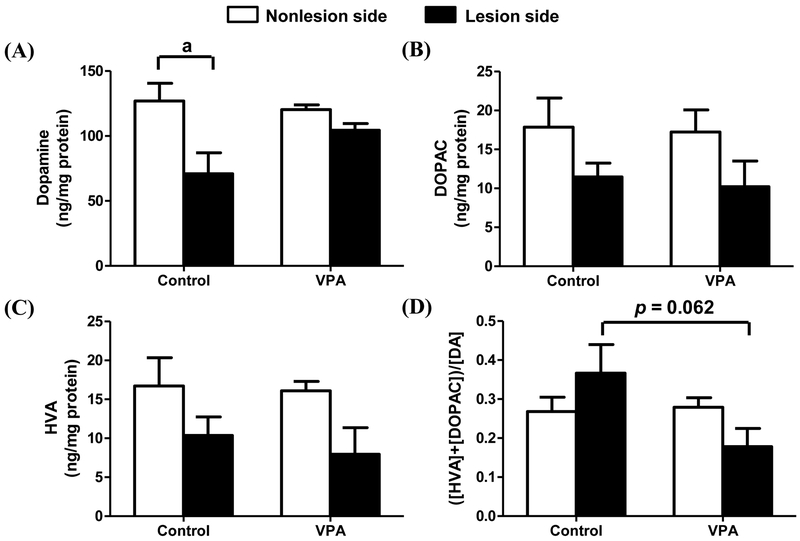

Figure 3 shows that the injection of 6-OHDA significantly lowered the striatal content of dopamine in the lesion side (71 ng/mg protein) compared with the non-lesion side (127 ng/mg protein) (p < 0.05). VPA treatment partially prevented the decrease of the dopamine level on the lesion side (Fig. 3A). The levels of dopamine metabolites, DOPAC and HVA, were also lower on the lesion side of the striatum compared to the non-lesion side. These decreases in both HVA and DOPAC were not affected by VPA treatment. There was a trend of reversing the increased ratio of the HVA+DOPAC/DA by VPA, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. Meanwhile, 6-OHDA also decreased DOPAC and HVA simultaneously, but not reached significant difference between 6-OHDA lesion side and non-lesion side. However, there was a trend of reversing the increased ratio of the HVA+DOPAC/DA by VPA with a marginal significance (p = ?).

Figure 3.

Changes in dopamine and its metabolites in rat striatum. Dopamine (A), DOPAC (B), HVA (C), and a calculated measure of dopamine activity (D) in rat striatum. Rats received pre-and post-treatments consisting of i.p. injection with saline (n = 5) (control group) or VPA (n = 5; 100 mg/kg). Of these, ten were treated by intracranial local injection of a dose of 10 μg of 6-OHDA in 4 μL at the right-side MFB. Statistically significant differences between the groups were detected by one-way ANOVA. Lesion side, intracranial injection of 6-OHDA; non-lesion side, intracranial injection of saline; vertical bars represent standard error of the mean; n = 5 for each group; a, p < 0.05 compared to the non-lesion side.

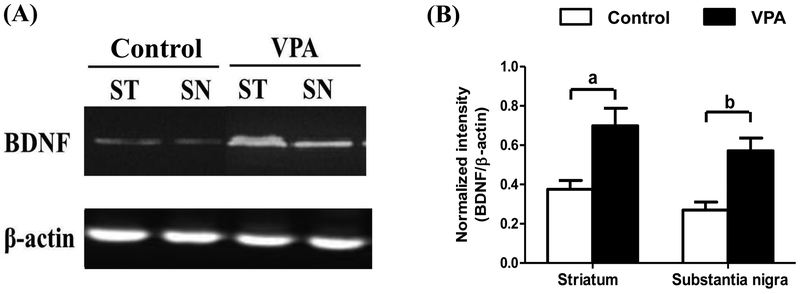

VPA treatment increases BDNF in rat substantia nigra and striatum

The neurotrophic factors BDNF and GDNF were measured in the substantia nigra and striatum by Western blotting analysis. Figure 4 shows that BDNF was significantly increased 1.86 times in the striatum (p < 0.01) and 2.12 times in the substantia nigra (p < 0.01) by VPA treatment compared with the control group (Fig. 4A and 4B). However, the levels of GDNF in the substantia nigra and striatum were not significantly affected by VPA treatment (data not shown).

Figure 4.

VPA treatment increased levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in rat striatum (ST) and substantia nigra (SN). Immunoblotting analysis disclosed that daily treatment with VPA at 100 mg/kg i.p. for 4 weeks significantly increased BDNF in the striatum and substantia nigra compared to rats treated with saline (A and B). Statistically significant differences between the groups were detected by Student’s t-test. Vertical bars represent standard error of the mean; n = 5 for each group; a, p < 0.01 compared to the control group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that local injection of the neurotoxin 6-OHDA into rat midbrain induced dose-dependent dopaminergic neurodegeneration. In addition to showing cell-type-specific dopaminergic neurotoxicity, 6-OHDA also induced significant microglia activation. VPA treatment of rats receiving a moderate dose of 6-OHDA significantly protected dopaminergic neurons against neurotoxin-induced neurodegeneration and preserved motor performance. Biochemical analysis of rat striatum confirmed that 6-OHDA injection significantly reduced dopamine content. The neuroprotective effect of VPA against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity may be partially ascribed to VPA having stimulated the production of BDNF in rat striatum and substantia nigra.

6-OHDA, a well-known neurotoxin, is an analog of DA with a high affinity for the dopamine transporter. When 6-OHDA is taken up by DA neurons, it undergoes prompt auto-oxidation associated with a high rate of free radical formation. It also accumulates in mitochondria, where it inhibits the activity of the electron transport chain by blocking complex I, which eventually leads to DA-neuron apoptosis.17,18 A unilateral local injection of 6-OHDA at rat MFB inducing midbrain DA neurodegeneration and parkinsonian-like syndromes has become a useful animal model of PD for preclinical research.13,19,20 Truong et al.21 have demonstrated that injection of increasing concentrations of 6-OHDA (4, 8, and 16 μg) into the MFB can establish a graded model of different clinical stages of PD. Parkinson disease symptomatology becomes significant and can be observed with as little as 40% dopaminergic cell loss and becomes obvious when cell loss reaches 70%. Our study also demonstrated that the lowest dose of 6-OHDA used here (5 μg) induced mild DA neurodegeneration (26%) and very early disease-related symptoms of PD, while moderate (10 μg) and high (15 μg) doses induced overt DA neurodegeneration (75% and 90%, respectively) and significant difficulties in balance during the rotarod test (Fig. 1). Our dose-response study showed that 10 μg of 6-OHDA injected to the MFB could serve as a useful rodent PD model for testing the efficacy of novel neuroprotective drugs. This is shown by a substantial attenuation of 6-OHDA (10 μg)-elicited DA neuron loss by VPA (Fig. 1). Higher dose of 6-OHDA (15 μg) caused more than 80–90% of loss of DA neurons, which became difficult to clearly show the neuroprotective effect of VPA. Conversely, lower dose (5 μg) of 6-OHDA-elicited DA neuron loss was too small to effectively demonstrate the efficacy of VPA in clinical symptomology of PD.

Two weeks after an injection of 10 μg of 6-OHDA into the right-side MFB of rats, the SNc appeared largely devoid of THir cells (Fig. 2) and the striatum seemed moderately depleted of dopamine (Fig. 3) in rats receiving saline treatment. This was comparable to one of the typical pathological hallmarks seen in the brains of PD patients and such an acute assault on the brain can explain why the moderately lesioned rats showed significant motor deficits in the rotarod test. However, a moderate dose of 6-OHDA significantly reduced the neuronal THir, had no influence on total neuron number, and increased microglia activation (OX42ir cells) in the SN (Fig. 2). This indicates that 6-OHDA is preferentially taken up by DAergic neurons through the DA transporter system, and thus specifically damages DAergic neurons while sparing other neuronal types, but with the co-occurrence of microglia activation. In VPA-treated rats, partial sparing of 6-OHDA-lesioned dopaminergic neurons was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for TH cells in the substantia nigra and quantitative analysis based on band densitometry (Fig. 2). Similar trends observed in this group were reduced dopamine loss in homogenates of striata and recovered motor deficits during rotarod testing (Fig. 1C and 3A). Notably, VPA treatment had neuroprotective effects against 6-OHDA-induced rat dopaminergic neurodegeneration and significantly ameliorated its parkinsonian symptomology, but the exact therapeutic mechanism remains unclear. A growing body of evidence suggests that VPA has multiple molecular targets and cellular pathways contributing both neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects suitable for treating a wide variety of brain disorders. For reviews, see the following.5,22,23,24 In 2011, the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association regarded VPA as one of the most promising investigative priorities for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and meriting future disease-modifying clinical trials for PD.25 However, the study found no differences in local neuroinflammatory responses such as the number of OX42ir cells in the SN or in the expression of proinflammatory factors such as TNFα and IL10 (data not shown) in rats receiving VPA treatment compared with saline treatment. The finding of a trivial anti-inflammatory effect of VPA may be ascribed to a too-low administered dose relative to that required to inhibit the microglial over activation induced by 6-OHDA. Contrasting with the above findings on anti-inflammatory effects, rats receiving VPA treatment had a significant increase in BDNF expression in SN and striatum compared with rats receiving saline. The present results verify that VPA treatment in a rat PD model mimics the findings in vitro,7,26 in that it may partially protect dopaminergic neurons against 6-OHDA-induced neurodegeneration by stimulating secretion of the neurotrophic factor BDNF. Neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and GDNF have been reported to be related to dopaminergic neuron survival and neurogenesis.27,28 A decrease in the expression of these neurotrophic factors might be one of the causes of neurodegenerative diseases.29,30,31 In a previous study, VPA promoted neuronal survival, neurite outgrowth, and neurogenesis to protect neurons against various insults. Multiple mechanisms for this have been proposed, including activation of ERK pathways32 and histone hyperacetylation, which would up-regulate astrocyte GDNF and BDNF gene transcription to protect dopaminergic neurons.26,33 An increase in BDNF can upregulate antioxidant proteins and antioxidant processes in neurons, which reduces oxidative stress by increasing glutathione disulfide reductase expression, thereby decreasing the glutathione disulfide (GSSG) / reduced glutathione (GSH) ratio.34,35 Neurotrophic factors also reduce apoptosis in neurons, an effect mediated through Trk receptors, leading to activation of the PI3-kinase and MAPK pathways.36,37,38 In rat primary astrocyte culture, it was found that both BDNF and GDNF were acutely increased by VPA treatment, but the GDNF level decreased after 24 hours whereas BDNF was still increased after 48 hours.7 This result might partially explain why only BDNF was increased existed in the striatum and substantia nigra after 4 weeks of VPA treatment in vivo. Our results reveal that BDNF, but not GDNF, expression increases in the substantia nigra and striatum under chronic treatment with VPA in rat (Fig. 4). Therefore, by increasing neurotrophic factors in the central nerve system, VPA The effect might increase the expression of neuroprotective genes and thereby protect dopaminergic neurons from 6-OHDA toxicity.26 Unfortunately, the study lacked direct evidence from VPA co-treatment with TrkB-IgG chimera, BDNF scavenging antibody or BDNF receptor antagonist, K252a to prove neuroprotective effect of VPA from BDNF upregulation. However, Tao et al demonstrated that BDNF signaling is required for HDAC inhibitor. In a rat model of inflammatory pain, the analgesic effects of HDAC inhibitors on behavior were blocked by nucleus raphe magnus co-infusion with TrkB inhibitor K252a.[26] Meanwhile, a recent clinical evidence proved that valproate treatment markedly improved functional outcomes in patients with major brain injury from acute MCA infarction.39

In conclusion, this study is the first in vivo demonstration that VPA treatment may have neuroprotective effects by increasing BDNF expression in the substantia nigra and striatum of rat. The study is to demonstrate that VPA treatment may increase expression of one of neurotrophins, BDNF, against 6-OHDA-induced nigrostriatal degeneration in rat. Consistent with previous in vivo studies,8,11,40 VPA treatment significantly reduced 6-OHDA-induced nigrostriatal degeneration and motor dysfunction in rats. Although the evidence of neuroprotective effects of VPA in animal models of PD is growing, much further work is required to verify the underlying mechanisms, in particular, epigenetic effects on HDAC, before VPA can be advanced to the clinic. The graded PD model established by using different doses of 6-OHDA is still one of the acute models and may not recapitulate the progressive course of PD. To bridge this gap between bench and bedside, the neuroprotective effects of VPA must in future be verified appropriately in more clinically translatable animal experiments.

Funding/support statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology grants NSC98-2314-B-016-031-MY1 & 2, NSC100-2314-B-016-001 and NSC 102-2314-B-016-027; the Ministry of National Defense grants MAB101-57 and 103-M082, Taiwan. This research was also supported by the Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Hsinchu Branch grants VHCT-RD-2016-8 and VHCT-RD-2017-6.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Reference

- 1.Henry TR. The history of valproate in clinical neuroscience. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37 Suppl 2:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johannessen CU. Mechanisms of action of valproate: a commentatory. Neurochem Int 2000;37:103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perucca E. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of valproate: a summary after 35 years of clinical experience. CNS Drugs 2002;16:695–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ximenes JCM, Verde ECL, Naffah-Mazzacoratti MDG, Viana GSDB. Valproic acid, a drug with multiple molecular targets related to its potential neuroprotective action. Neurosci Med 2012;3:107–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu CT, Wang Z, Hunsberger JG, Chuang DM. Therapeutic potential of mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid: beyond bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Rev 2013;65:105–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison IF, Dexter DT. Epigenetic targeting of histone deacetylase: therapeutic potential in Parkinson’s disease? Pharmacol Ther 2013;140:34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen PS, Peng GS, Li G, Yang S, Wu X, Wang CC, et al. Valproate protects dopaminergic neurons in midbrain neuron/glia cultures by stimulating the release of neurotrophic factors from astrocytes. Mol Psychiatry 2006;11:1116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen PS, Wang CC, Bortner CD, Peng GS, Wu X, Pang H, et al. Valproic acid and other histone deacetylase inhibitors induce microglial apoptosis and attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Neuroscience 2007;149:203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng GS, Li G, Tzeng NS, Chen PS, Chuang DM, Hsu YD, et al. Valproate pretreatment protects dopaminergic neurons from LPS-induced neurotoxicity in rat primary midbrain cultures: role of microglia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2005;134:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leng Y, Chuang DM. Endogenous alpha-synuclein is induced by valproic acid through histone deacetylase inhibition and participates in neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. J Neurosci 2006;26:7502–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti B, Gatta V, Piretti F, Raffaelli SS, Virgili M, Contestabile A. Valproic acid is neuroprotective in the rotenone rat model of Parkinson’s disease: involvement of alpha-synuclein. Neurotox Res 2010;17:130–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidd SK, Schneider JS. Protective effects of valproic acid on the nigrostriatal dopamine system in a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 2011;194:189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres EM, Lane EL, Heuer A, Smith GA, Murphy E, Dunnett SB. Increased efficacy of the 6-hydroxydopamine lesion of the median forebrain bundle in small rats, by modification of the stereotaxic coordinates. J Neurosci Methods 2011;200:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling ZD, Chang Q, Lipton JW, Tong CW, Landers TM, Carvey PM. Combined toxicity of prenatal bacterial endotoxin exposure and postnatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the adult rat midbrain. Neuroscience 2004;124:619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling Z, Zhu Y, Tong CW, Snyder JA, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Prenatal lipopolysaccharide does not accelerate progressive dopamine neuron loss in the rat as a result of normal aging. Exp Neurol 2009;216:312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews ST, Plaisance EP, Kim T. Imaging systems for westerns: chemiluminescence vs. infrared detection. Methods Mol Biol 2009;536:499–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blum D, Torch S, Lambeng N, Nissou M, Benabid AL, Sadoul R, et al. Molecular pathways involved in the neurotoxicity of 6-OHDA, dopamine and MPTP: contribution to the apoptotic theory in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 2001;65:135–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 2003;39:889–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deumens R, Blokland A, Prickaerts J. Modeling Parkinson’s disease in rats: an evaluation of 6-OHDA lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway. Exp Neurol 2002;175:303–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan H, Sarre S, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. Histological, behavioural and neurochemical evaluation of medial forebrain bundle and striatal 6-OHDA lesions as rat models of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Methods 2005;144:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Truong L, Allbutt H, Kassiou M, Henderson JM. Developing a preclinical model of Parkinson’s disease: a study of behaviour in rats with graded 6-OHDA lesions. Behav Brain Res 2006;169:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang ZF, Fessler EB, Chuang DM. Beneficial effects of mood stabilizers lithium, valproate and lamotrigine in experimental stroke models. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2011;32:1433–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fessler EB, Chibane FL, Wang Z, Chuang DM. Potential roles of HDAC inhibitors in mitigating ischemia-induced brain damage and facilitating endogenous regeneration and recovery. Curr Pharm Des 2013;19:5105–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Leng Y, Tsai LK, Leeds P, Chuang DM. Valproic acid attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia: the roles of HDAC and MMP-9 inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011;31:52–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lauterbach EC, Mendez MF. Psychopharmacological neuroprotection in neurodegenerative diseases, part III: criteria-based assessment: a report of the ANPA committee on research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;23:242–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu X, Chen PS, Dallas S, Wilson B, Block ML, Wang CC, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors up-regulate astrocyte GDNF and BDNF gene transcription and protect dopaminergic neurons. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;11:1123–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman C, Hofer M, Barde Y-a, Juhasz M, Yancopoulos GD, Squinto SP, et al. BDNF is a neurotrophic factor for dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. Nature 1991;350:230–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu JK, Gardaneh M, Iwasiow R, Lanthier P, Gangaraju S, Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M, et al. Astrocyte-secreted GDNF and glutathione antioxidant system protect neurons against 6OHDA cytotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis 2009;33:405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips HS, Hains JM, Armanini M, Laramee GR, Johnson SA, Winslow JW. BDNF mRNA is decreased in the hippocampus of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 1991;7:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogi M, Togari A, Kondo T, Mizuno Y, Komure O, Kuno S, et al. Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth factor concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett 1999;270:45–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howells DW, Porritt MJ, Wong JY, Batchelor PE, Kalnins R, Hughes AJ, et al. Reduced BDNF mRNA expression in the Parkinson’s disease substantia nigra. Exp Neurol 2000;166:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hao Y, Creson T, Zhang L, Li P, Du F, Yuan P, et al. Mood stabilizer valproate promotes ERK pathway-dependent cortical neuronal growth and neurogenesis. J Neurosci 2004;24:6590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasuda S, Liang MH, Marinova Z, Yahyavi A, Chuang DM. The mood stabilizers lithium and valproate selectively activate the promoter IV of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurons. Mol Psychiatry 2009;14:51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spina MB, Squinto SP, Miller J, Lindsay RM, Hyman C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor protects dopamine neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine and N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion toxicity: involvement of the glutathione system. J Neurochem 1992;59:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Zhou Y, Wang C, Wang T, Zheng Z, Chan P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) genetic polymorphism greatly increases risk of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:140–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen N, Lee SB, Lee YS, Lee KH, Ahn JY. Neuroprotection by NGF and BDNF against neurotoxin-exerted apoptotic death in neural stem cells are mediated through Trk receptors, activating PI3-kinase and MAPK pathways. Neurochem Res 2009;34:942–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almeida RD, Manadas BJ, Melo CV, Gomes JR, Mendes CS, Graos MM, et al. Neuroprotection by BDNF against glutamate-induced apoptotic cell death is mediated by ERK and PI3-kinase pathways. Cell Death Differ 2005;12:1329–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang N, Wu L, Cao Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y. The protective activity of imperatorin in cultured neural cells exposed to hypoxia re-oxygenation injury via anti-apoptosis. Fitoterapia 2013;90:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JT, Chou CH, Cho NY, Sung YF, Yang FC, Chen CY, et al. Post-insult valproate treatment potentially improved functional recovery in patients with acute middle cerebral artery infarction. Am J Transl Res 2014;6:820–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monti B, Mercatelli D, Contestabile A. Valproic acid neuroprotection in 6-OHDA lesioned rat, a model for parkinson’s disease. HOAJ Biol. 2012;1:1–4. [Google Scholar]