Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are two common protein aggregation diseases. Compelling evidence has shown a link between AD and T2D, which may derive from interspecies cross-sequence interactions between amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), associated with AD, and human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP), associated with T2D. Herein, we present experimental and computational protocols and tools to study the aggregate structures and kinetics, conformational conversion, and molecular interactions of Aβ-hIAPP mixtures. These protocols could be generally applied to other cross-seeding behaviors of amyloid peptides.

Keywords: Amyloid peptides, Aβ, hIAPP, Cross-seeding, Alzheimer disease, Diabetes

1. Introduction

Amyloid peptides can misfold and aggregate into conformationally similar amyloid fibrils consisting of characteristic cross-β-sheet structures. Fibrils formed by different amyloid peptides are associated with more than 20 neurodegenerative and other protein aggregation diseases [1], Among them, Alzheimer disease (AD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) are the two common age-related chronic disorders [2, 3], both affecting millions of people globally. Accumulating evidence has shown that ~81% of AD patients often have a higher risk of developing type II diabetes (T2D), and vice versa [4, 5]. Although the precise mechanisms linking these two disorders are still unclear, the evidence suggests a potential pathological link between AD and T2D.

Considering that amyloid peptides share a common aggregation process and their aggregates share similar structural hallmarks, the AD-T2D link could arise from cross-species interactions between the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) [6, 7] and the human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP or amylin) [8–11], which are associated with AD and T2D, respectively. Several lines of evidences appear to support the hypothesis of the cross-species interaction between Aβ and hIAPP: (1) Aβ and hIAPP coexist in the serum and cerebrospinal fluids with similar concentrations [6]; (2) Aβ co-localizes with hIAPP in pancreatic islet amyloid deposits of T2D patients [7]; and (3) hIAPP and Aβ show high degrees of sequence identity (25%) and similarity (50%), making it possible for them to interact with each other to form hybrid amyloid fibrils [6, 12]. Similar cross-seeding behavior between different amyloid species (Aβ and α-synuclein [13], Aβ and tau [14], and hIAPP and insulin [15]) and even between bacterial curli and amyloid peptides of SEVI, Aβ, and hIAPP have been reported [16]. This fact at least suggests that amyloid cross-seeding sets the scene to reveal some general principles governing heterogeneous protein misfolding and aggregation.

Only a few studies have shown that Aβ and hIAPP may cross-seed fibrillization, but with different cross-seeding efficiencies, strongly depending on experimental conditions (seeding concentrations, sequence specifity, and even agitation) [17–20]. Different seeding abilities of Aβ vs. hIAPP aggregates suggest the existence of different cross-species barriers for different amyloid species to interact with the other and form hybrid amyloids [21]. Given the current state of knowledge of the cross-seeding of amyloid peptides, it still remains unclear how Aβ and hIAPP interact with each other to induce cross-seeding behaviors. Herein, we detail computational and experimental protocols, obtained from our recent works, to probe the aggregation kinetics of Aβ/hIAPP mixtures by fluorescent dye thioflavin-T (ThT), the fibril morphologies by atomic force microscopy (AFM), the secondary structure transformation by circular dichroism (CD), and atomic-scale structures and association by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. This chapter will hopefully provide robust and general strategies to study the cross-species amyloid aggregation by different amyloid peptides, which may help to reveal a possible link between different neurodegenerative diseases.

Understanding the cross-species aggregation mechanisms between Aβ and hIAPP peptides is critical for revealing a potential pathological link between AD and T2D. In this chapter, we report the details of computational and experimental tools, protocols, and conditions to study how Aβ and hIAPP peptides interact with each other and how such cross-sequence interactions affect the structures of their aggregates and pathways. Collective data demonstrate the existence of cross-seeding interaction and aggregation between Aβ and hIAPP, yielding hybrid Aβ – hIAPP amyloid fibrils morphologically similar to pure Aβ or hIAPP fibrils. Further molecular simulations reveal different atomic structures of hybrid Aβ – hIAPP fibrils, indicating that the complex assembly of Aβ and hIAPP produces polymorphic amyloid cross-seeding species through different aggregation pathways. The cross-seeding effects in this work may provide a molecular explanation for a potential link between AD and T2D and hopefully lead to therapeutic advances that could treat different neurodegenerative diseases. Technically, the tools, protocols, and conditions we used for Aβ-hIAPP cross-seeding could be readily applied to other amyloid peptides.

2. Materials

Prepare ultrapure water by purifying deionized water to obtain a sensitivity of 18 MΩ cm at 25 °C; use this ultrapure water for all aqueous solutions. All chemical reagents were purchased at the analytical grade and stored at room temperature (unless indicated otherwise).

2.1. Experimental Materials

Beta-amyloid (Aβ1–42, ≥95.0%) and human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP1–37, ≥95.0%) (American Peptide Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).

l,l,l,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, ≥99.9%).

NaOH solution: 10 mM NaOH in water (see Note 1).

PBS buffer: 10 mM, pH 7.4. Phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) dry powder was purchased in foil pouches. Dissolve each pouch in 1 L of water to yield 10 mM phosphate buffered saline, NaCl 0.138 M, KCl 0.0027 M. Store at 25 °C (see Note 2).

Thioflavin T (ThT) Tris-buffer: 10 μM ThT, pH 7.4. Add about 100 mL water to a 1 L amber bottle. Weigh 1.22 g Tris and transfer it to the bottle. Add water to a volume of 900 mL. Mix and adjust pH to 7.4 by carefully adding concentrated HCl. Make up to 1 L with water to produce a 1 L 10 mM Tris-buffer.

ThT-water solution (2 mM): add 33 mg of ThT powder into 50 mL of water. Dilute 250 μL of this ThT-water solution into 50 mL of Tris-buffer resulting in a final concentration of 10 μM ThT Tris-buffer (see Note 3).

3. Methods

3.1. Purification and Preparation of Peptides

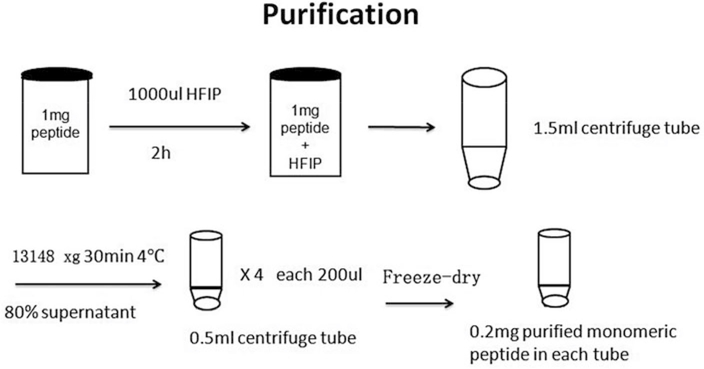

Obtained both Abeta and hIAPP as a lyophilized form and each peptide of 1 mg was stored separately in a small amber glass bottle in a −20 °C refrigerator.

Add 1 mL HFIP into each glass bottle with 1.0 mg Aβ or hIAPP peptide inside and seal the bottle cap with parafilm. Allow the peptide to fully dissolve in HFIP solution for 2 h, followed by 30 min sonication to make peptides in a monomeric state in the solution (see Note 4).

Transfer the 1 mL peptide-HFIP mixture to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, and centrifuge the mixture solution at 13,148 × g for 30 min at 4 °C.

Extract 80% (0.8 mL) of the top solution, save it in four 500-μL micro tubes, each containing 0.2 mL of the top solution.

Freeze the extracted solutions in a −80 °C refrigerator and freeze-dry at −110 °C and 10 mTorr.

Extract 0.2 mg dry peptide powder from the micro tube and lyophilize in a −80 °C refrigerator [22] (see Note 5) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Preparation procedure of amyloid peptide purification

3.2. Peptide Incubation

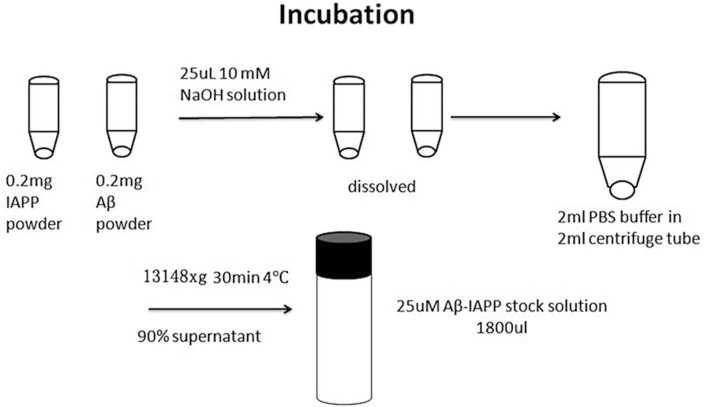

Add 25 μL of 10 mM NaOH solution to 0.2 mg purified Aβ powder in a microfuge tube, and sonicate the mixture for 1 min to obtain a homogeneous Aβ-NaOH solution.

Add 25 μL of 10 mM NaOH solution into 0.2 mg purified hIAPP powder in the micro tube and sonicate the mixture for 1 min at 13,148 × g to obtain a homogeneous hIAPP-NaOH solution (see Note 6).

Add the 25 μL Aβ-NaOH solution into 2 mL of 10 mM PBS buffer solution in 2 mL centrifuge tube at 4 °C, and mix using vortex. Right after mixing, add 25 μL hIAPP-NaOH solution to the previous Aβ-NaOH-PBS solution, and mix using vortex.

Centrifuge the Aβ-hIAPP mixture solution at 13,148 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove any potential oligomers, followed by extracting 90% of the top Aβ-hIAPP solution (1.8 mL) in the monomeric state of both peptides for cross-seeding tests [23] (Fig 2).

Fig. 2.

Procedure of amyloid peptide incubation

3.3. Monitor Amyloid Formation Using Thioflavin T Fluorescence Assay (ThT)

Add 3 mL ThT Tris-buffer to a 1 cm × 1 cm quartz cuvette and install the cuvette in the sample chamber. Measure the emission curve between 470 and 500 nm with an excitation wavelength of 450 nm. The emission curve is used as a background control (see Note 7).

Add 60 μL of incubated peptide solution, obtained from “peptide incubation,” to the ThT Tris-buffer in the cuvette and mix well. Measure the emission curve and subtract the background curve to obtain a true-fluorescence intensity at this time point [24]. Each peptide sample is tested in triplicate (see Note 8).

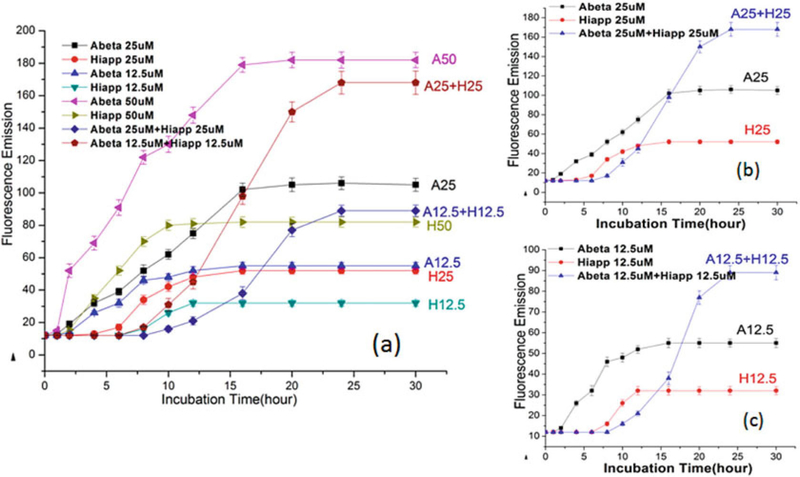

Repeat steps 1–2 at different time points, collect all the data to do the analysis of variance, use graphics software (Excel, Origin et al.) to plot a time-dependent ThT curve to quantify the aggregation kinetics of the cross-seeding of Aβ and hIAPP (Fig. 3a-c).

Fig. 3.

Time-dependent ThT fluorescence curves for pure Aβ, pure hIAPP, and mixed Aβ/hIAPP at different concentration of 12.5 mM, 25 mM, and 50 mM. Reprinted with permission from ref. [23]. (Copyright 2015 ACS Publication)

3.4. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy (CD)

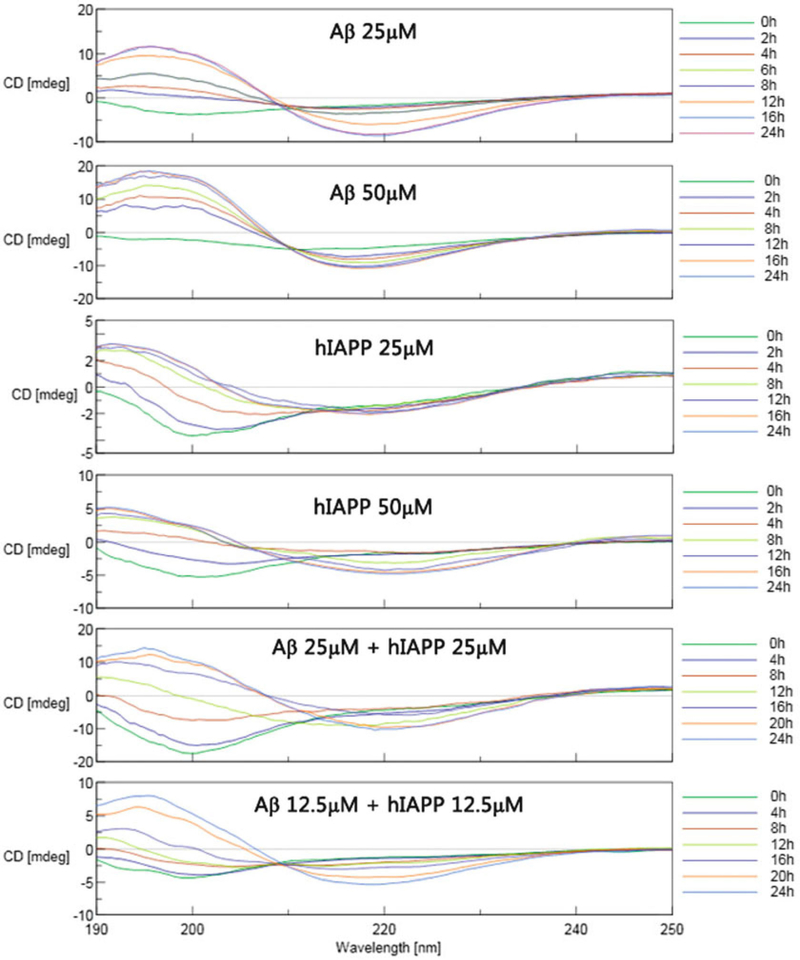

Obtain CD spectra by scanning between 250 and 190 nm at a 0.5 nm resolution and 50 nm/min scan rate. Correct all spectra by subtracting the baseline and report the data as the average of three successive scans for each sample.

Add 160 μL incubated peptide solution into a rectangular quartz cuvette with a 1 mm path length without dilution (see Note 9).

Repeat steps 1–2 at different time points to obtain a time-dependent CD curve to quantify the conformational change of the cross-seeding of Aβ and hIAPP.

The secondary structure contents from the CD spectra can be estimated using the self-consistent method (CDSSTR program) in the CD proanalysis software [25, 26] (Fig. 4a–f).

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent far-UV CD spectra for (a) pure Aβ (25 μm), (b) pure Aβ (50 μm), (c) pure hIAPP (25 μm), (d) pure hIAPP (50 μm), (e) mixed Aβ/hIAPP (25/25 μM), and (f) mixed Aβ/hIAPP (12.5/12.5 μm). Reprinted with permission from ref. [23]. (Copyright 2015 ACS Publication)

3.5. Tapping-Mode Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

All images are acquired in tapping mode as 512 × 512 pixel images at a typical scan rate of 1.0–2.0 Hz with a vertical tip oscillation frequency of 250–350 kHz [27].

Take 20 μL incubated peptide solution and deposit the solution onto a freshly cleaved mica substrate for 1 min.

Gently rinse the surface with 10 mL of ultrapure water to remove salts and loosely bound peptides, dry the surface with compressed air for 1 min, and leave the sample to air-dry before AFM imaging.

Representative AFM images are collected by scanning at least six different locations of different samples (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative AFM images for pure Aβ, pure hIAPP, and mixed Aβ/hIAPP aggregates after incubation for 0, 4, 8,12, and 24 h. Reprinted with permission from ref. [23]. (Copyright 2015 ACS Publication)

3.6. Simulation Protocols

3.6.1. Aβ Pentamer

Obtain the atomic structure of Aβ pentamer from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (ID:2EBG) [28].

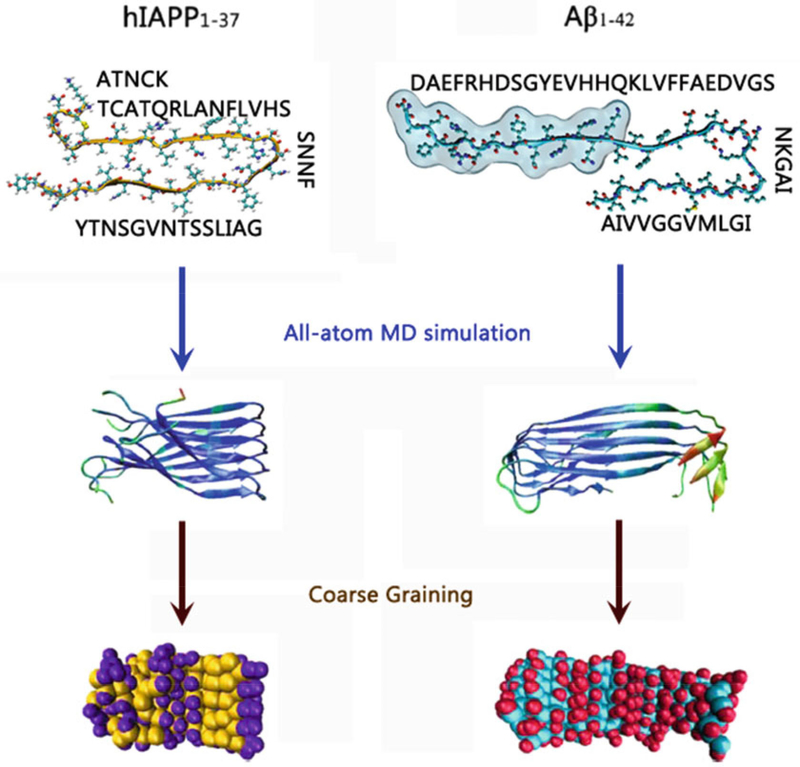

Add the N-terminal missing residues in an in-register manner in the β-sheet conformation using the GaussView program (see Notes 10 and 11, Fig. 6).

Cap the N- and C-termini with NH3+ and COO− groups. Assign the tautomeric state of His residues based on local environment.

Use a 500-step steepest descent (SD) minimization with backbone atoms fixed to relax the initial structure of the Aβ pentamer (see Note 12).

Fig. 6.

All-atom and CG-based structures and sequences of hIAPP and Aβ peptides

3.6.2. hIAPP Pentamer

The initial coordinates of hIAPP monomer were kindly provided by the Tycko lab [29].

Five hIAPP monomers are parallel-packed on top of each other in an in-register manner with inter-peptide distance of 4.7 Å (see Note 11).

Construct the intramolecular disulfide bond between Cys2 and Cys7 at the N-termini of hIAPP peptides. The tautomeric state of His residues is assigned based on local environment in the hIAPP monomer.

Perform a 500-step SD minimization with backbone atoms fixed to refine the overall structure (see Note 12, Fig. 6).

3.6.3. Coarse-Grained Model of Aβ Pentamer

First, perform a 100-ns all-atom explicit-solvent simulation of Aβ to obtain the equilibrium structure of Aβ pentamer in bulk water.

Extract 500 all-atomic structures of the Aβ pentamer from the last 20-ns MD trajectory excluding water molecules. Each Aβ structure is energy minimized with 500-step SD minimization to remove any structural clashes.

Obtain an average structure of Aβ pentamer by averaging the 500 structures above, followed by 500-step SD minimization to refine the average structure.

Use the elastic network method with the Martini force fields (version 2.4) to convert the all-atom average structures of Aβ pentamer into the CG structure of the Aβ pentamer (see Note 13, Fig. 6).

3.6.4. Coarse-Grained Model of hIAPP Pentamer

First, perform 100-ns all-atom explicit-solvent simulation of hIAPP to obtain the equilibrium structure of the hIAPP pen tamer in bulk water.

Extract 500 all-atomic structures of the hIAPP pentamer from the last 20-ns MD trajectory excluding water molecules. Energy minimize each hIAPP structure with 500-step SD minimization to remove any structural derivations.

Obtain an average structure of the hIAPP pentamer by averaging the 500 structures above, followed by a 500-step SD minimization to refine the average structure.

Use the elastic network method with the Martini force fields (version 2.4) to convert the all-atom average structures of the hIAPP pentamer into the CG structure of the hIAPP pentamer (see Note 14, Fig. 6).

3.7. Simulation Methods

3 7.1. Coarse-Grained Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (CG-REMD) Simulations of Hybrid Aβ-hIAPP Assemblies

Separate the CG Aβ and hIAPP pentamers from each other by random intermolecular distances and orientations.

Place the Aβ-hIAPP system in a simulation box of 100 × 100 × 100 Ǻ3 with the three-dimensional periodical boundary condition (3D-PBC).

Fully solvate the simulation system with coarse-grained water molecules with minimal margins of 15 Å from any protein atom to any edge of water box.

Add Cl− and Na+ counterions into the systems to mimic an ionic strength of ~150 mM.

Structurally optimize and relax the resulting system using 5000 steps of the steepest decent minimization.

Heat the energy minimized system gradually from 0 to 310 K by 1-ns MD simulations, constraining the peptide backbones using the NPT ensemble (T = 310 K and P = 1 atm) and under periodic boundary conditions.

For the production run, treat the Aβ-hIAPP system under NPT ensemble and 3D-PBC conditions using CG-REMD simulations with the Gromacs-4.6.5 software package. A total of 40 independent replicas with temperatures ranging from 305 to 410 K should be simulated simultaneously for each Aβ-hIAPP system (see Note 15).

The exchange rate between two replicas is attempted every 1000 integration steps and the acceptance ratio for exchanging replicas varied between 0.20 and 0.25.

Control the temperatures and pressure (1 atm) by the V-rescale and Parrinello-Rahman methods with coupling constants of 1.0 and 12.0 ps, respectively. Conduct the temperature coupling separately for protein and nonprotein atoms (i.e., ions and water molecules).

Leapfrog integrator was utilized to allow an integration time step of 4 fs (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of the CG-REMD simulations

3.7.2. CG Hybrid Aβ-hIAPP Assemblies

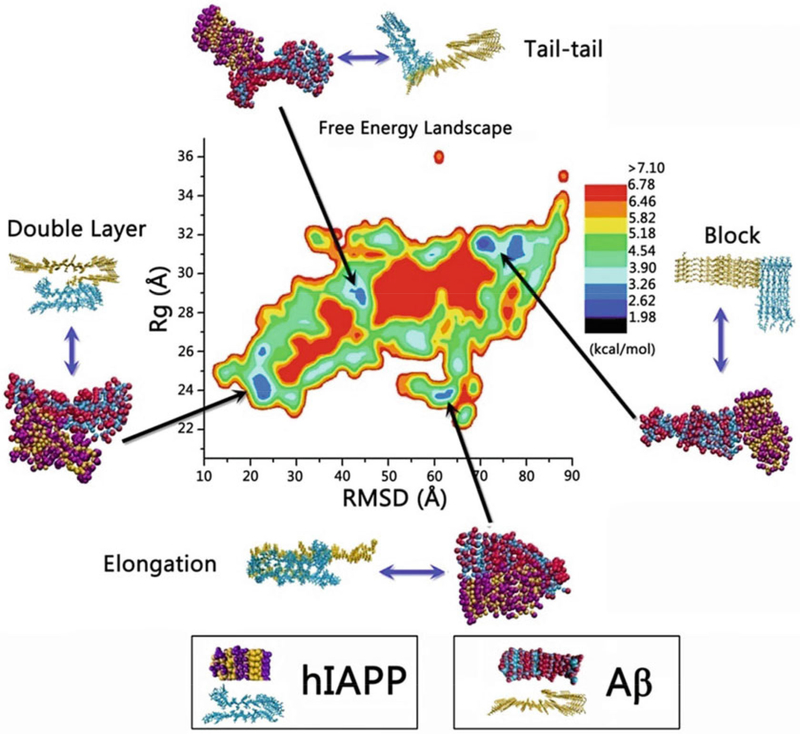

From the CG-REMD simulations, construct the free energy landscape that describes the interaction between hIAPP and Aβ using –RT log(H(x,y)), where H(x,y) is the histogram of two selected reaction coordinates: x is root-mean-square derivation (RMSD) and y is the radius of gyration (Rg) (see Notes 16 and 17).

Based on the free energy landscape, identify the four most populated CG Aβ-hIAPP hetero-assemblies (double-layer, elongation, tail-tail, and block modes) at different energy potential wells (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

CG-based free energy landscape along Aβ and hIAPP aggregation process as a function of two reaction coordinates of RMSD and Rg. Reprinted with permission from ref. [30]. (Copyright 2015 ACS Publication)

3.7.3. Conversion of CG Aβ-hIAPP Models to All-Atom Aβ-hIAPP Stmctures

Based on the most populated CG Aβ-hIAPP hybrids obtained from the CG free energy landscape, we developed a two-step strategy to convert the CG Aβ-hIAPP structures to all-atom Aβ-hIAPP ones.

The first step of backmapping is to generate an initial, all-atom structure. In the CG model, the center of mass of the groups of atoms are represented by a single CG bead as the center of mass location of backbone (Bcom), side chains (Scorn), and/or other peripheral groups (Pcom) for each residue. Then, the centers of mass of all-atom backbones, sidechains, and/or peripheral groups of each residue of the same hIAPP or Aβ peptides are superimposed into Bcom, Scorn, and/or Pcom, and all atoms are assigned coordinates according to standard geometries using GROMACS around these mapped atoms. This backmapping step produces an initial all-atom of A-β-hIAPP structure from the CG one. The resulting structure is then optimized by energy minimization to remove any bad contacts and to correct internal coordinates for all bonded atoms (steps 1 and 2 in Fig. 9, see Note 18).

The second step is to optimize interfacial contacts between Aβ and hIAPP. The resulting all-atom structure obtained from the first stage is further recast into the initial all-atom Aβ or hIAPP models to maximize residue-residue contacts by minor structural adjustments through structural superimposition and rotation, followed by energy minimization. In this way, the structural disorder of the resulting all-atom structures, caused by the high temperatures in CG-based REMD simulation, is minimized (steps 2 and 3 in Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Schematic illustration of the conversion of Aβ-hIAPP cross-seeding assemblies from coarse-grained to all-atom models

3.7.4. All-Atom MD Simulations of Aβ-hIAPP Models

The obtained all-atom Aβ-hIAPP models from the CG models are then subjected to all-atom explicit-solvent simulations to validate the models; perform these simulations using the Gromacs-4.6.5 program with the CHARMM27 force field with CMAP correction and SPCE solvent models [31, 32].

Solvate all-atom Aβ-hIAPP systems in a cubic water box with minimal margin of 15 Ǻ from any protein atom to any edge of the water box. Add Cl− and Na+ ions into the systems to mimic ~150 mM ionic strength.

The resulting systems are structurally optimized and relaxed by 50,000 steps of the steepest decent minimization.

Gradually heat the energy minimized systems from 0 to 310 K by 1-ns MD simulations with constrained peptide backbones.

Conduct MD simulations for 60 ns using the NPT ensemble (T = 310 K and P = 1 atm) and under periodic boundary conditions. The Parrinello-Rahman and the V-rescale methods are used to maintain a constant pressure of 1 atm and a temperature of 310 K.

Constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms by the LINCS method. Short-range Van der Waals (VDW) interactions should be described by the smoothly truncated method via potential shift at 14 Å. Long-range electrostatic interactions should be calculated by the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method with a grid spacing of 0.16 Å and a real-space cutoff of 12 Å.

Integrate the equations of motion using the Leapfrog integrator with a time step of 2 fs. Structures should be saved every 2 ps for analysis.

3.7.5. Structural and Population Analysis of All-Atom Aβ-hIAPP Models

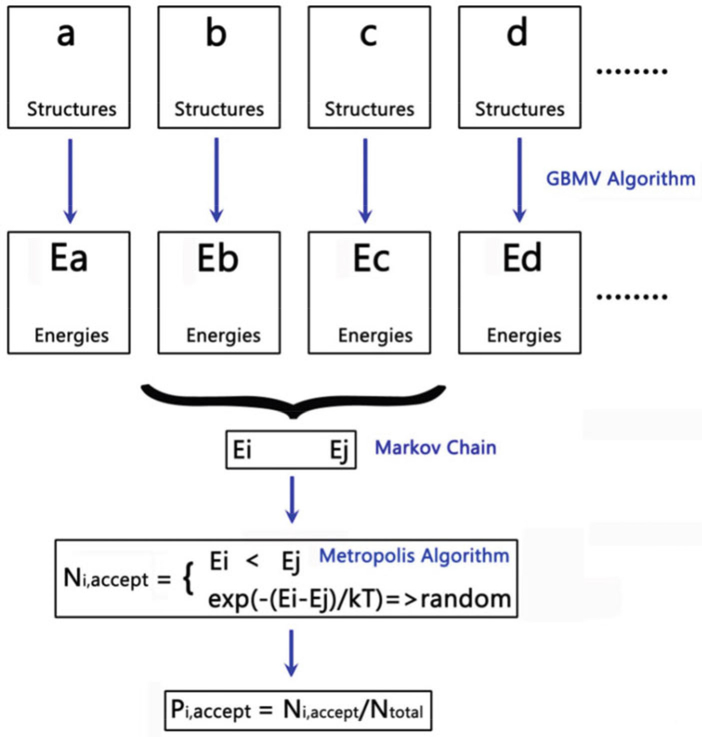

Conduct in-house Monte Carlo simulations to calculate the relative populations for the Aβ-hIAPP models. First, 500 structures per each all-atom Aβ-hIAPP model are extracted from the last 10-ns explicit-water MD trajectories, excluding water molecules [30].

All extracted structures (i.e., all conformers) from all Aβ-hIAPP models are used to construct an energy landscape of Aβ-hIAPP assemblies for evaluating the probability of conformers using an in-house Monte Carlo program as reported in our previous studies [33–35].

Calculate the conformational energies of all conformers using the generalized Born method with molecular volume (GBMV) with the CHARMM force field, where the dielectric constant of 80 is used for water and the hydrophobic solvent accessible surfaces area (SAAS) term factor is set to 0.00592 kcal/mol Å [2], This GBMV free energy calculation generates a Markov chain of all conformers [E1, E2… Ei, …En].

For conformer population analysis, randomly select any two structures from conformers i and j and calculate their conformational energies using the GBMV model. Then, the metropolis algorithm is applied to determine the transition probability (i.e., acceptance probability) from conformer i to conformer j using . After one million step samplings, a total number of “accepted” structures (Ni) for any conformer i is counted, and the relative probability of conformer i occurring in the energy landscape is evaluated as pi = Ni/Ntotal (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Schematic illustration of the calculations of the populations for different Aβ-hIAPP hybrid assemblies

Acknowledgments

J.Z. thanks the financial support from NSF (CBET-1510099 and DMR-1607475), Alzheimer Association (2015-NIRG-341372), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-21528601). The high-performance computational facilities of the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the NIH were mainly used for the simulations. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Prepare fresh NaOH solutions on the same day as Aβ and hIAPP incubation.

PBS solution needs to be filtered by a hydrophilic filter of 0.22 μm pore size prior to use for peptide incubation.

Both dissolution and dilution of peptides use sonication to ensure uniformity of the ThT buffer solution.

HFIP is a powerful solvent to dissolve peptide aggregates into monomers; thus we use HFIP to remove any preexisting peptide aggregates from the originally purchased peptides.

This procedure allows the peptides to be maintained in monomeric, random coil structures at the initial stage of incubation.

Use vortex mixing to ensure the complete dissolution of peptide powders in the micro tube.

The ThT fluorescence assay is considered as a standard method to detect the formation of amyloid fibrils, because ThT can specifically bind to the β-sheet structure of amyloid fibrils, typically yielding a strong fluorescence emission around a wavelength of485 nm.

For ThT measurement at a given time point, the fluorescence intensity difference between a peptide sample and a blank sample indicates the amount of β-sheet structure in the peptide sample solution.

Selection of cuvette path length is important for CD spectra, because appropriate light absorption is required to obtain accurate CD signals. Strong light adsorption increases the photomultiplier voltage resulting in the increase of signal noises, while weak light adsorption often leads to the loss or uncertainty of signal peaks. Both effects will cause inaccurate and unreliable signals.

The N-terminal 1–16 residues (1DAEFRHDS-GYEVHHQK16]are added to the NMR structure of Aβ. The backbone of the added residues is aligned with the initial N-terminal strand of the Aβ structure so that the inter-peptide backbone hydrogen bonds are constructed.

The inter-peptide distance within both Aβ and hIAPPβ-sheets is set to 4.7 Å, which well reproduces the peptide-peptide hydrogen bonds and the β-sheet structure.

The initially constructed structures may contain some unreasonable steric overlaps between sidechains and backbones. The SD minimization with CHARMM27 force field is required to eliminate any bad atom contacts. To minimize the structural disruption of the β-sheet, the backbone atoms in the structure are harmoniously constrained during the SD minimization.

The obtained all-atom structures are converted into the coarse-grained models using the Martini force field (version 2.4) using the martinize.py script (http://md.chem.rug.nl/images/tools/martinize/martinize-2.4/martinize.py). In the coarsegrained models, the secondary structure of the Aβ or hIAPP pentamer is determined by the DSSP algorithm.

Replica exchange simulation requires each replica to contain exactly the same atoms. Thus, caution should be exercised when solvating the system so that the number of water molecules in the simulation box will be strictly controlled by the “genbox” plugin in the Gromacs4.6.5 program with the “–nmol” flag.

The replica temperature distribution is calculated using the web-server of “A temperature predictor for parallel tempering simulations” (http://folding.bmc.uu.se/remd/). The tolerance is le-4, the exchange probability is 0.20, the lowest temperature is 305 K, the highest temperature is 410 K.

The trajectories used to calculate the free energy landscape are extracted from the previous CG-REMD simulations. The equilibrium of the systems is confirmed by studying the Rg distribution profiles of the Aβ-hIAPP cross-seeding assemblies at different simulation intervals.

For cluster analysis, RMSD and Rg data for each structure in the equilibrium trajectories are calculated. The structures with the RMSD and Rg difference less than 1.5 Å are assigned as the same cluster.

The AutoPsf plugin in the VMD program is used to reconstruct all covalent bonds when converting the CG Aβ-hIAPP models to the corresponding all-atom models.

References

- 1.Chiti F, Dobson CM (2006) Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Arum Rev Biochem 75:333–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ (2008) Amyloid-[beta] protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 14(8):837–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeToma AS, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH (2012) Misfolded proteins in Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes. Chem Soc Rev 41(2):608–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janson J, Laedtke T, Parisi JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC (2004) Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53(2):474–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolls MR (2004) The clinical and biological relationship between type II diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimers disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 1 (l):47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreetto E, Yan LM, Tatarek-Nossol M, Velkova A, Frank R, Kapurniotu A (2010) Identification of hot regions of the A beta-IAPP interaction interface as high-affinity binding sites in both cross- and self-association. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed 49 (17):3081–3085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miklossy J, Qing H, Radenovic A, Kis A, Vileno B, Laszlo F, Miller L, Martins RN, Waeber G, Mooser V, Bosnian F, Khalili K, Darbinian N, McGeer PL (2010) Beta amyloid and hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in the pancreas in type 2 diabetes. Neurobiol Aging 31(9):1503–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luca S, Yau W-M, Leapman R, Tycko R (2007) Peptide conformation and supramolecular organization in amylin fibrils: constraints from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 46 (47):13505–13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brender JR, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A (2012) Membrane disruption and early events in the aggregation of the diabetes related peptide IAPP from a molecular perspective. Acc Chem Res 45(3):454–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang MZ, Hu RD, Chen H, Chang Y, Ma J, Liang GZ, Mi JY, Wang YR, Zheng J (2015) Polymorphic cross-seeding amyloid assemblies of amyloid-beta and human islet amyloid polypeptide. Phys Chem Chem Phys 17 (35):23245–23256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M, Hu R, Chen H, Chang Y, Gong X, Liu F, Zheng J (2015) Interfacial interaction and lateral association of cross-seeding assemblies between hIAPP and rIAPP oligomers. Phys Chem Chem Phys 17:10373–10382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolls MR (2004) The clinical and biological relationship between Type II diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 1 (l):47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandal PK, Pettegrew JW, Masliah E, Hamilton RL, Mandal R (2006) Interaction between Aβ peptide and α synuclein: molecular mechanisms in overlapping pathology of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in dementia with Lewy body disease. Neurochem Res 31(9):1153–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stancu I-C, Vasconcelos B, Terwel D, Dewachter I (2014) Models of β-amyloid induced Tau-pathology: the long and “folded” road to understand the mechanism. Mol Neurodegener 9(1):1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu P, Zhang S, Chen M-s, Liu Q, Wang C, Wang C, Li Y-M, Besenbacher F, Dong M (2012) Co-assembly of human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP)/insulin. Chem Commun 48(2):191–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartman K, Brender JR, Monde K, Ono A, Evans ML, Popovych N, Chapman MR (2013) Ramamoorthy A, Bacterial curli protein promotes the conversion of PAP248–286 into the amyloid SEVI: cross-seeding of dissimilar amyloid sequences. PeerJ l:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreetto E, Yan L-M, Tatarek-Nossol M, Velkova A, Frank R, Kapurniotu A (2010) Identification of hot regions of the Aβ-IAPP interaction interface as high-affinity binding sites in both cross- and self-association. Ange Chem Inter Ed 49(17):3081–3085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Nuallain B, Williams AD, Westermark P, Wetzel R (2004) Seeding specificity in amyloid growth induced by heterologous fibrils. J Biol Chem 279(17):17490–17499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan LM, Velkova A, Tatarek-Nossol M, Andreetto E, Kapurniotu A (2007) IAPP mimic blocks Aβ cytotoxic self-assembly: cross-suppression of amyloid toxicity of Aβ and IAPP suggests a molecular link between Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes. Angew Chem Int Ed 46(8):1246–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeliger J, Evers F, Jeworrek C, Kapoor S, Weise K, Andreetto E, Tolan M, Kapurniotu A, Winter R (2012) Cross-amyloid interaction of Aβ and IAPP at lipid membranes. Angew Chem Int Ed 51(3):679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma B, Nussinov R (2012) Selective molecular recognition in amyloid growth and transmission and cross-species barriers. J Mol Biol 421 (2–3):172–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu R, Zhang M, Patel K, Wang Q, Chang Y, Gong X, Zhang G, Zheng J (2014) Cross-sequence interactions between human and rat islet amyloid polypeptides. Langmuir 30 (18):5193–5201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu R, Zhang M, Chen H, Jiang B, Zheng J (2015) Cross-seeding interaction between (β-amyloid and human islet amyloid polypeptide. ACS Chem Neurosci 6(10):1759–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biancalana M, Makabe K, Koide A, Koide S (2009) Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-t-binding to the surface of [beta]-rich peptide self-assemblies. J Mol Biol 385(4):1052–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sreerama N, Woody RW (2000) Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal Biochem 287 (2):252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juszczyk P, Kolodziejczyk A, Grzonka Z (2005) Circular dichroism and aggregation studies of amyloid beta (11–28) fragment and its variants. Acta Biochim Pol 52(2):425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Yu X, Patal K, Hu R, Chuang S, Zhang G, Zheng J (2013) Tanshinones inhibit amyloid aggregation by amyloid-β peptide, disaggregate amyloid fibrils, and protect cultured cells. ACS Chem Neurosci 4(6):1004–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luhrs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Doeli H, Schubert D, Riek R (2005) 3D structure of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta(l-42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sri U S A 102(48):17342–17347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luca S, Yau WM, Leapman R, Tycko R (2007) Peptide conformation and supramolecular organization in amylin fibrils: constraints from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 46 (47):13505–13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang MZ, Hu RD, Chen H, Gong X, Zhou FM, Zhang L, Zheng J (2015) Polymorphic associations and structures of the cross-seeding of A beta(l-42) and hIAPP(l-37) polypeptides. J Chem Inf Model 55(8):1628–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC (2005) GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem 26(16):1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck M, Bouguet-Bonnet S, Pastor RW, MacKerell AD (2006) Importance of the CMAP correction to the CHARMM22 protein force field: dynamics of hen lysozyme. Biophys J 90(4):L36–L38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu X, Zheng J (2011) Polymorphic structures of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid globulomers. PLoS One 6(6):e20575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao J, Hu R, Sciacca MFM, Brender JR, Chen H, Ramamoorthy A, Zheng J (2014) Non-selective ion channel activity of polymorphic human islet amyloid polypeptide (amylin) double channels. Phys Chem Chem Phys 16 (6):2368–2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang MZ, Hu RD, Liang GZ, Chang Y, Sun Y, Peng ZM, Zheng J (2014) Structural and energetic insight into the cross-seeding amyloid assemblies of Human IAPP and Rat IAPP. J Phys Chem B 118(25):7026–7036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]