Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: healthcare, IEXPAC instrument, inflammatory bowel disease

Abstract

To assess inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients’ experience of chronic illness care and the relationship with demographic and healthcare-related characteristics.

This cross-sectional survey used the Instrument to Evaluate the EXperience of PAtients with Chronic diseases (IEXPAC) questionnaire to identify parameters associated with a better healthcare experience for IBD patients. IEXPAC questionnaire responses are grouped into 3 factors - productive interactions, new relational model, and patient self-management, scoring from 0 (worst) to 10 (best experience). Scores were analyzed by bivariate comparisons and multiple linear regression models.

Surveys were returned by 341 of 575 patients (59.3%, mean age 46.8 (12.9) years, 48.2% women). Mean (SD) IEXPAC score was 5.9 (2.0); scores were higher for the productive interactions (7.7) and patient self-management factors (6.7) and much lower for the new relational model factor (2.2). Follow-up by a nurse, being seen by the same physician, and being treated with a lower number of medicines were associated with higher (better) overall patient experience score, and higher productive interactions and self-management factor scores. A higher productive interactions score was also associated with patients receiving medication subcutaneously or intravenously. Higher new relational model scores were associated with follow-up by a nurse, affiliation to a patients’ association, receiving help from others for healthcare, a lower number of medicines and a higher educational level.

In patients with IBD, a better overall patient experience was associated with follow-up by a nurse, being seen by the same physician, and being treated with a lower number of medicines.

1. Introduction

Patient experience with healthcare is positively associated with clinical effectiveness and patient safety in a wide range of diseases and care settings such as hospitalization and primary care visits.[1] In chronic disease, the delivery of high-quality care significantly improves patients’ experience,[2] with productive patient–professional interactions being critical for patient well-being and the quality of care.[3] Multidisciplinary care teams, which often include nurses and pharmacists, are also required for effective chronic illness management.[4]

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic condition characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and is categorized into ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn Disease (CD). IBD adversely affects health-related quality of life (HRQoL),[5–7] and can have a major impact on the activities of daily living.[8–11] For healthcare, IBD patients require a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach.[12,13] Increased specialized care involving a gastroenterologist, a nurse with experience in the care of IBD patients and other specialists is associated with improved outcomes in IBD.[14–16] However, there is relatively little information regarding patients’ experience with healthcare and perceived needs in IBD and how this relates to specialized healthcare.

Instruments to assess the experience of chronic patients include the 20-item Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC),[17] the Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care (PPIC) survey,[18,19] and the Instrument to Evaluate the Experience of Patients with Chronic Diseases (IEXPAC).[20] The main advantages of the IEXPAC scale are that it accounts for the interaction of patients with healthcare teams, instead of focusing on specific professionals; incorporates a broader notion of integrated care, including social care and patient self-management; and includes new technological interventions and patients’ interactions with other patients.[20]

We previously reported the outcomes of a survey to assess the experience of patients with 4 different chronic conditions: diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, rheumatic disease, or IBD, with healthcare using the IEXPAC questionnaire.[21] In the current work, we focus on the group of patients with IBD, with the objective of assessing their experience with healthcare using the IEXPAC scale, identifying areas of improvement in healthcare and to explore the potential influence of demographic and healthcare-related variables on patients’ experiences.

2. Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey of adult patients (aged >18 years) with IBD who were attending hospital clinics in Spain which assessed patients’ experience of chronic illness care. This patient cohort was part of a larger study of 4 chronic diseases: diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, rheumatic disease and IBD.[21]

A total of 23 gastroenterology units from hospital clinics participated in the study. The survey was handed to the first 25 consecutive patients attending their gastroenterology clinic routinely, regardless of age, gender, disease severity or any other criterion. The survey was conducted between May and September 2017 and was distributed to patients by their treating physician or nurse. The survey was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Investigation Ethics Committee of the Gregorio Marañón Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

Patients were instructed to read the survey and complete it voluntarily and anonymously from home, and to return it by pre-paid mail. Survey documentation included information for patients regarding the anonymous nature of the survey and aggregated data processing, thus ensuring that patient identification was not possible. As accepted by the Clinical Investigation Ethics Committee, the return of completed questionnaires was taken as implied consent to participate in the study. There was no collection of clinical data in this study.

The study protocol, methodology and main outcomes for the overall population have been described elsewhere.[21] Taking the IEXPAC 2015 scale as the starting point, the content of the overall survey was developed for this study with the participation of 4 expert physicians in the treatment of the above-mentioned patients, and was reviewed by members of 3 patients’ associations: the Spanish Association of Patients with Arthritis (CONARTRITIS), the Spanish Association of Patients with Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (ACCU), and the Spanish Federation of Patients with Diabetes (FEDE), and by members of the Spanish AIDS Multidisciplinary Society (SEISIDA), a Spanish Society composed of patients with HIV infection and different healthcare professionals. Patients reviewed the content and appropriateness of the questions and language used, and suggested modifications or additional questions. Except for validated questionnaires including IEXPAC, which were not modified, suggestions from patients were included in the final survey. The study was endorsed by the above-mentioned patients’ associations.

2.1. Survey instrument

The survey included multiple-choice questions that provided information on patients’ demographics, healthcare-related characteristics, follow-up by different specialists or nurses, and treatment characteristics (Supplementary Material). The IEXPAC questionnaire was a specific part of the survey. The first version of the IEXPAC (2015 version 11 + 1) was used in this study.

The IEXPAC questionnaire was developed in 2015 through a thorough process of literature review, with input from an expert panel (including healthcare professionals and social organizations, and experts in quality of healthcare and chronic diseases). Its content, validity and reliability were assessed following pilot and field work involving 356 chronically ill patients.[20]

The questionnaire was designed to be self-administered by patients and consists of 11 items, plus 1 additional item for patients who were hospitalized recently. The items refer to the last 6 months, except the question on hospitalization, which refers to the last 3 years. A description of each item (as presented to patients) is displayed in Table 1. For each item, patients responded using a 5-point Likert scale, that was subsequently transformed using a fixed scoring system: “always” (score 10), “mostly” (score 7.5), “sometimes” (score 5), “seldom” (score 2.5) and “never” (score 0). The scale yields an overall score (sum of individual scores of the 11 items divided by 11) between 0 (worst experience) and 10 (best experience) and allows identification of items in which improvement is needed.

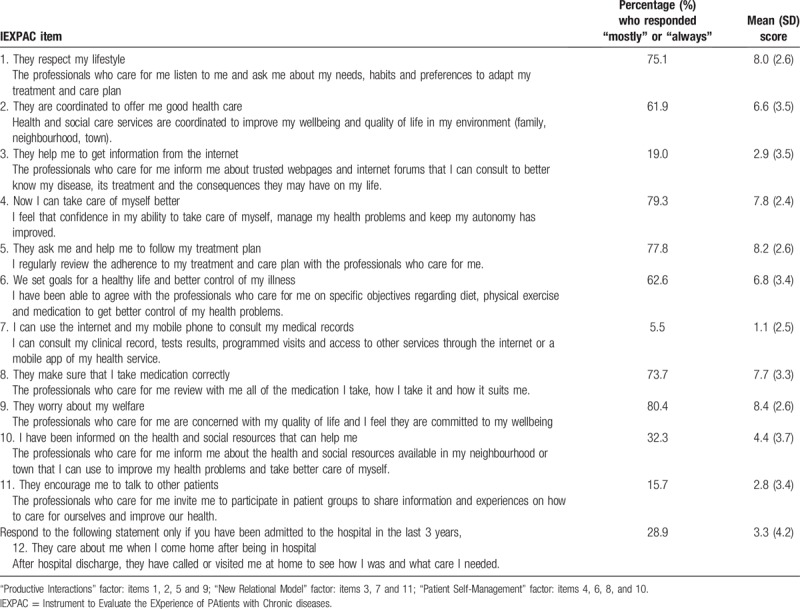

Table 1.

Word-for-word IEXPAC items. Percentage of patients who responded “mostly” or “always” to each item and mean score (standard deviation).

Three factors are derived from the first 11 IEXPAC items. Factor 1 is named “productive interactions” and refers to the characteristics and content of interactions between patients and professionals oriented to improve outcomes. The productive interactions score is the average of the scores from items 1, 2, 5, and 9. Factor 2, the “new relational model”, refers to new forms of patient interaction with the healthcare system, through the internet or with peers. Its score is the average of the scores of items 3, 7, and 11. Finally, Factor 3, named “patient self-management”, refers to the ability of individuals to manage their own care and improve their wellbeing based on healthcare professional-mediated interventions. The patient self-management score is the average of the scores from items 4, 6, 8, and 10. The 12th item refers to continuity after hospitalization and is described separately.

2.2. Statistical analysis

By its nature, this survey is exploratory, and no formal hypothesis or pre-specified sample size was calculated. Taking a conservative approach, we estimated a sample size of 267 patients based on a qualitative variable with 50% as the expected prevalence, a confidence interval of 95% and 6% precision. Assuming that the variables would not be completed correctly by 15% of patients, the total size of the sample to recruit was estimated to be 314 patients. To this number, we added the expected response rate to calculate the final number of surveys. Assuming a 50% response rate, as seen in other surveys,[22,23] we determined that we would need a survey sample size of approximately 628 patients with each background disease.

Descriptive information is displayed as mean and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and frequencies or percentages for qualitative variables. The results of the IEXPAC questionnaire were calculated as overall mean (SD) score and mean (SD) scores of the 3 above-mentioned factors. The distribution of responses to the individual items is also displayed, as well as the sum of the percentages of “always” plus “mostly” responses to each item.

Chi-squared or Fisher exact tests were used for the comparison of proportions and the Student t or the ANOVA test to compare continuous variables. Multiple linear regression models were used to assess the different demographic and healthcare-related variables influencing the IEXPAC overall score and the score for each factor. Beta coefficients with P values are shown. Given the overall descriptive nature of the results, no multiplicity adjustments were made. There was no imputation for missing data.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the sample

The survey was handed to 575 patients with IBD and 341 were returned (response rate: 59.3%). The mean (SD) age of respondents was 46.8 (12.9) years and consisted of approximately equal numbers of men (51.8%) and women (48.2%). The educational level achieved was 30.2% for primary studies, 42.1% for secondary studies including vocational studies, and 27.8% for university or higher. Some 10.1% of patients declared an affiliation with a patients’ association. For their follow-up, 7.8% needed to travel to a Spanish region different from their home region. Nearly three-quarters of patients (73.4%) searched for information about disease characteristics, medication, diet or lifestyle using alternative sources to those provided by healthcare professionals. The most frequently reported sources were web pages specialized in health (56.9%), general web pages (21.7%), general media (18.8%), patients’ societies (19.1%) and other patients (27.9%).

With regard to healthcare-related characteristics, patients visited a mean (SD) of 3.8 (2.1) specialists (including primary care) during the previous year. The specialists most frequently visited by IBD patients were primary care physicians (85.3%), rheumatologists (23.8%), gynecologists (22.9%), dermatologists (19.9%) and orthopedic surgeons (17.6%). For their treating physician, 85.2% of patients declared that they were usually followed up by the same physician (i.e., the same gastroenterologist), 10.6% reported that the physician was sometimes different and 4.2% declared that the physician was frequently different. Regular follow-up by a nurse was reported by 44.3% of patients. For their healthcare, 59.2% declared taking care of themselves, whilst 40.8% received help from others, that is, relatives, friends or caregivers.

Regarding their treatment, patients received a mean (SD) number of 3.5 (2.4) different medications, with 42.2% receiving subcutaneous (SC) or intravenous (IV) medication. During the past 3 years, 50.7% of patients had been hospitalized (for any reason) at least once.

3.2. IEXPAC responses and experience scores

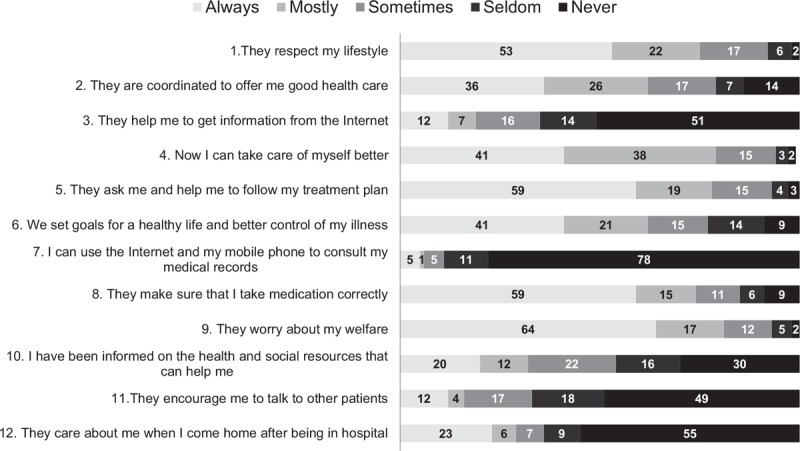

Figure 1 displays the distribution of responses to the 12 IEXPAC items and their mean scores. Table 1 shows the word-for-word items, the proportion who responded “always” or “mostly” to each item and the mean (SD) scores for each item. For the items related to productive interactions (Factor 1) and patient self-management (Factor 3), the proportion of patients who responded “always” or “mostly” was >60% except for one Factor 3 item (“I have been informed on the health and social resources that can help me”). In contrast, the proportion and scores of items relating to new relational model (Factor 2) were low (<20% responded “always” or “mostly”). Of 173 patients who had been hospitalized in the past 3 years, only 50 (28.9%) responded “always” or “mostly” to item 12 (“They care about me when I come home after being in hospital”), whilst 110 (63.6%) reported this “seldom” or “never” happened.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of patients’ responses to IEXPAC items. Numbers in bars represent the percentage who responded to each option.

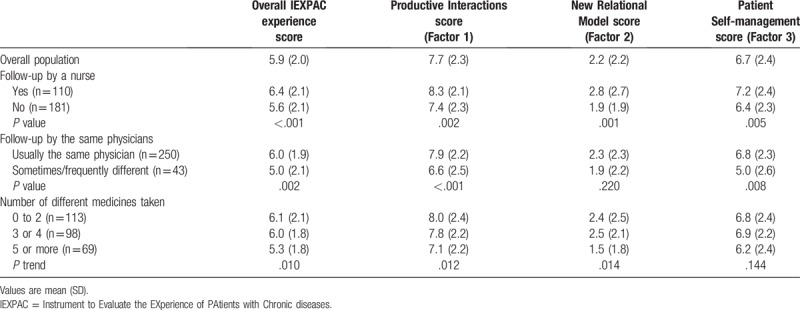

The mean (SD) IEXPAC score was 5.9 (2.0) overall. Scores were higher for the productive interactions and patient self-management factors and much lower for the new relational model factor (Table 2). The overall IEXPAC experience score and the scores for the 3 different factors were significantly higher (indicating a better experience) in patients who were followed-up by a nurse or seen by the same physician (except the new relational model factor); and lower (a worse experience) in those taking a higher number of medicines, especially in patients being treated with 5 or more different drugs (Table 2).

Table 2.

IEXPAC experience scores. Overall score and score of the different healthcare-related factors.

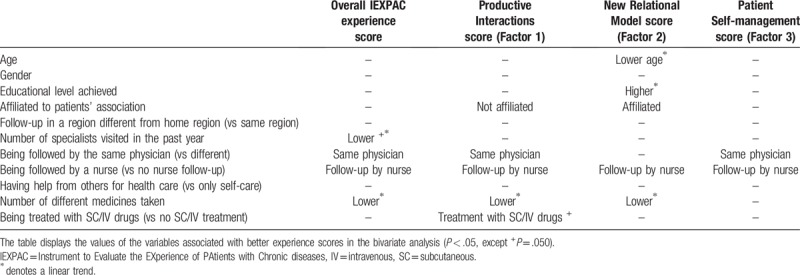

Scores did not differ between men and women or between age quartiles, except for the new relational model, that was higher in younger patients (P linear trend = .039). Patients with a higher educational level and those affiliated with patients’ associations scored higher in the new relational model factor, and patients treated with SC or IV medication had higher productive interactions scores. The specific scores stratified by different variables are displayed in Table 2 and in Supplementary Tables. A summary of bivariate comparisons with statistical significance is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis. Variables associated with better experience scores. See Supplementary Tables for additional information.

3.3. Multivariate analysis

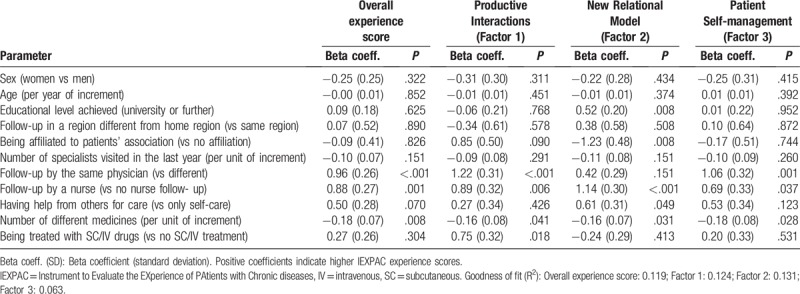

Table 4 shows the results of the multiple linear regression models. Having follow-up by a nurse, being seen by the same physician and treatment with a lower number of medicines, were associated with a better overall experience score, and better productive interactions and self-management factor scores. Treatment with SC or IV medications was associated with a better productive interactions factor score. Finally, follow-up by a nurse, affiliation with a patients’ association, receiving help from others for healthcare, a lower number of medicines and a higher educational level, were associated with a better new relational model factor score (Table 4). The models explained only a small part of the variability (goodness of fit (R2) for the overall IEXPAC score: 0.119, Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis. Multiple logistic regression models for the IEXPAC overall experience score and for the different factors.

4. Discussion

This observational study, which primarily used the IEXPAC questionnaire,[20] identified a series of parameters that were associated with a better experience for IBD patients receiving care in outpatient hospital clinics. A better overall patient experience was associated with follow-up by a nurse, being seen by the same physician, and being treated with a lower number of medicines. These parameters were also associated with higher productive interactions and self-management factor scores. Patients treated with SC or IV medication also had better productive interactions scores. Higher new relational model scores were associated with follow-up by a nurse, affiliation to a patients’ association, receiving help from others for healthcare, a lower number of medicines and a higher educational level. Moreover, patients’ responses to IEXPAC statements identified areas for improvement in healthcare, especially those associated with access to reliable information and services, interaction with other patients and continuity of healthcare after hospital discharge.

The survey was based on 341 responding IBD patients with a mean age of 46.8 years from hospital clinics. This cohort is likely to consist of patients with established IBD as the peak incidence of both UC and CD occurs in the 15 to 29-year age group.[24] The response rate of 59.3% was comparable to those reported for surveys of other chronic diseases, which varied from 53% to 59.2%.[22,23]

The associations found in this study between better IEXPAC scores and several healthcare-related variables are important to drive efforts from a healthcare planning perspective. Firstly, the important role of nurses in the care of IBD patients is emphasized. Consensus statements issued recently by the Nurses European Crohn and Colitis Organisation (N-ECCO) for the care of IBD patients describe the critical and varied roles of nurses in the care of these patients.[25] The effectiveness of an IBD specialist nurse in the management of IBD patients has been described previously and included a reduction in hospital visits and improvement of patients’ satisfaction and information on IBD.[26,27] Moreover, from the patient's perspective, an interview-based survey in Spain of CD patients emphasized the requirement for a dedicated healthcare professional, such as a specialist nurse, to attend to the daily needs of newly-diagnosed patients who are ill-equipped to deal with the uncertainty of the disease course.[28] Thus, our study contributes to reinforce the importance of the nurse's role.

Second, our survey results also suggest the importance of reducing the number of physicians following the patient and that the same specialists follow the patient over time. Emotional links between patient and physician and a trusting relationship are of special importance in improving outcomes in patients with chronic disases.[29–31] Finally, our findings indicate that simplification of treatment regimens, taking a lower number of medicines, can lead to a better experience for patients. We found that patients treated with SC or IV medication had better productive interactions scores, which may be conditioned by closer and more personalized follow-up of these patients. In Spain, patients needing SC or IV drugs are usually followed-up by specialized IBD teams (physicians, nurses and even psychologists) with dedicated space in the clinic, which allows a higher number of quality interactions between patients and healthcare professionals.

The responses of patients to the IEXPAC statements also indicate areas of improvement in healthcare. Low proportions of patients responded “always” or “mostly” to Factor 2 statements (new relational model), and Factor 2 scored much lower than Factors 1 and 3. However, there was an association between “receiving help from others for healthcare” and better new relational model scores. In chronic diseases, such as IBD, with a high personal burden, support from others for healthcare – involving patients’ relatives or other patients – can have a positive impact on how patients confront everyday life and care. However, only 10.1% of patients were affiliated with a patients’ association, although the benefits of affiliation were also shown through higher new relational model scores. This may be due to a lack of encouragement by health professionals, as only 15.7% of patients reported that they were regularly encouraged to participate in patients’ groups. Only about one-fifth of patients (19%) reported that they were guided by health professionals to access information from the internet from trusted sites. However, most patients (73.4%) declared using alternative sources for information about IBD. Information accessed from general web pages or the general media which were accessed by 22% and 19% of patients respectively, may be unsuitable for providing patients with relevant information. Consequently, increased efforts should be made by healthcare professionals to direct patients to trusted sources of information, such as webpages of patients’ associations or scientific societies which contain content and language that has been adapted for use by non-healthcare professionals.

Patients’ responses also describe that, although 50% of patients were hospitalized during the previous 3 years, only 30% of patients declared that they had received a call or a home visit after discharge. This is an area for improvement, as patients with IBD commonly have complications needing hospitalization and these patients require continuous, specialized and personalized care. Because the IBD cohort was recruited in outpatient hospital clinics, the sample probably included patients with difficult-to-treat disease (represented by the fact that 42% of patients were receiving SC or IV medication, likely biological drugs). The role of a multidisciplinary team for the effective management of chronic disease is well recognized.[4] A small Spanish survey of 11 healthcare professionals comprising medical and nursing staff, reported a lack of understanding of the impact of CD on daily life. However, staff were aware of this limitation and advocated the use of a multidisciplinary team for personalized CD care.[32] The need for personalized care for IBD patients has also been highlighted by others. A large European questionnaire-based survey of IBD patients, in cooperation with 25 national IBD associations, found that nearly two-thirds (64%) of respondents (n = 4670) felt that gastroenterologists should ask more probing questions, and over half (54%) considered that they did not get the opportunity to tell their physician something which was potentially important.[10] Indeed, increased patient perception of chronic illness care was reported by IBD patients who had received sub-specialty care, for example, a consultation with a gastroenterologist, recent surgery or hospitalization.[33] This emphasizes the importance of patient-healthcare professional interaction for improved patient experience of care.[3]

The limitations of this study are the same as those identified for postal/written surveys. As this was an anonymous survey, the patient profiles of those who did not return the survey are unknown. No interviewer was present to moderate responses, so respondents could not be questionned further to qualify their answers.[34] The multivariate models explained only a small part of the variability, but factors were identified that, if corrected, have the potential to improve healthcare quality and patient experience. Further research is needed in order to assess whether IEXPAC score improvements are linked directly with improvements in clinical effectiveness and HRQoL.

In conclusion, the IEXPAC scale identified areas of improvement in IBD patients’ healthcare, especially those associated with access to reliable information and services, interaction with other patients and continuity of healthcare after hospital discharge. For IBD patients, this analysis of data using the IEXPAC questionnaire demonstrates that a better overall patient experience was associated with follow-up by a nurse, being seen by the same physician, and being treated with a lower number of medicines. These findings suggest potential actions in redirecting healthcare resources and investment towards more patient-centered healthcare goals. The outcomes of interventions should be explored with future research.

Acknowledgments

The following patients’ associations participated in the design of the overall study and endorsed it: Spanish Association of Patients with Arthritis (CONARTRITIS); Spanish Association of Patients with Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (ACCU); and the Spanish Federation of Patients with Diabetes (FEDE), and by the Spanish AIDS Multidisciplinary Society (SEISIDA). The authors wish to thank all patients who completed the survey, and the IEXPAC working group for providing such valuable tool. Editorial support was provided by Robert A. Furlong PhD and David P. Figgitt PhD, ISMPP CMPP, Content Ed Net, with funding from MSD Spain.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Data curation: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Formal analysis: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Funding acquisition: Luis Cea-Calvo.

Investigation: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Methodology: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Project administration: Luis Cea-Calvo.

Resources: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Software: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Supervision: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Validation: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Visualization: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Writing – Original Draft: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Writing – Review & Editing: Ignacio Marín-Jiménez, Francesc Casellas, Xavier Cortés, Mariana F García-Sepulcre, Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo, Nadia Soto, Ester Navarro-Correal, Roberto Saldaña, Javier de Toro, María J. Galindo, Domingo Orozco-Beltrán.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACCU = Spanish Association of Patients with Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis, CD = Crohn Disease, CONARTRITIS = Spanish Association of Patients with Arthritis, FEDE = Spanish Federation of Patients with Diabetes, HRQoL = Health-Related Quality of Life, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, IEXPAC = Instrument to Evaluate the EXperience of PAtients with Chronic diseases, IV = intravenous, N-ECCO = Nurses European Crohn and Colitis Organisation, PACIC = Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care, PPIC = Patient Perceptions of Integrated Care, SC = subcutaneous, SD = standard deviation, SEISIDA = Spanish AIDS Multidisciplinary Society, UC = ulcerative colitis.

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, New Jersey, USA.

Berta Juliá, Luis Cea-Calvo and Nadia Soto: full-time employees at Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain. Ignacio Marín-Jiménez: research funding (to his institution), consultant, advisory member or lectures from AbbVie, Chiesi, FAES Farma, Falk-Pharma, Ferring, Gebro Pharma, Hospira, Janssen, MSD, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Tillots, and UCB Pharma. Mariana F García-Sepulcre: lectures for MSD, Shire and Takeda. Ester Navarro-Correal: consultancy for MSD, and Takeda, educational presentations for MSD, Janssen, AbbVie and Takeda. María J. Galindo: grant payment (to her institution) from MSD, consultancy for VIIV, MSD, Gilead, Janssen and AbbVie. Domingo Orozco-Beltrán: consultancy and lectures for MSD.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

References

- [1].Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. High-quality chronic care delivery improves experiences of chronically ill patients receiving care. Int J Qual Health Care 2013;25:689–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. The importance of productive patient-professional interaction for the well-being of chronically ill patients. Qual Life Res 2015;24:897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ 2000;320:569–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Casellas F, Arenas JI, Baudet JS, et al. Impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Spanish multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005;11:488–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Haapamäki J, Roine RP, Sintonen H, et al. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease measured with the generic 15D instrument. Qual Life Res 2010;19:919–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Romberg-Camps MJ, Bol Y, Dagnelie PC, et al. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a population-based study in the Netherlands: the IBD-South Limburg cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:2137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pihl-Lesnovska K, Hjortswang H, Ek AC, et al. Patients’ perspective of factors influencing quality of life while living with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Nurs 2010;33:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Devlen J, Beusterien K, Yen L, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease: a patient-reported qualitative analysis and development of a conceptual model. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:545–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lonnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McMullan C, Pinkney TD, Jones LL, et al. Adapting to ulcerative colitis to try to live a ‘normal’ life: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences in the Midlands region of England. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghosh S. Multidisciplinary teams as standard of care in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;27:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee CK, Melmed GY. Multidisciplinary team-based approaches to IBD management: how might “one-stop shopping” work for complex IBD care? Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:825–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nguyen GC, Nugent Z, Shaw S, et al. Outcomes of patients with Crohn's disease improved from 1988 to 2008 and were associated with increased specialist care. Gastroenterology 2011;141:90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Murthy SK, Steinhart AH, Tinmouth J, et al. Impact of gastroenterologist care on health outcomes of hospitalised ulcerative colitis patients. Gut 2012;61:1410–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Law CC, Sasidharan S, Rodrigues R, et al. Impact of specialized inpatient IBD care on outcomes of IBD hospitalizations: a cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:2149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care 2005;43:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Singer SJ, Burgers J, Friedberg M, et al. Defining and measuring integrated patient care: promoting the next frontier in health care delivery. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:112–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Singer SJ, Friedberg MW, Kiang MV, et al. Development and preliminary validation of the patient perceptions of integrated care survey. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:143–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mira JJ, Nuño-Solinís R, et al. Development and validation of an instrument for assessing patient experience of chronic illness care. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:13doi: 10.5334/ijic.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Orozco-Beltrán D, de Toro J, Galindo MJ, et al. Healthcare experience and their relationship with demographic, disease and healthcare-related variables: a cross-sectional survey of patients with chronic disease using the IEXPAC scale. Patient 2018;doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0345-1. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bos-Touwen I, Schuurmans M, Monninkhof EM, et al. Patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].González CM, Carmona L, de Toro J, et al. Perceptions of patients with rheumatic diseases on the impact on daily life and satisfaction with their medications: RHEU-LIFE, a survey to patients treated with subcutaneous biological products. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:1243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Johnston RD, Logan RF. What is the peak age for onset of IBD? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14Suppl 2:S4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kemp K, Dibley L, Chauhan U, et al. Second N-ECCO consensus statements on the european nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:760–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nightingale AJ, Middleton W, Middleton SJ, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a specialist nurse in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hernández-Sampelayo P, Seoane M, Oltra L, et al. Contribution of nurses to the quality of care in management of inflammatory bowel disease: a synthesis of the evidence. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:611–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].García-Sanjuán S, Lillo-Crespo M, Richart-Martínez M, et al. Understanding life experiences of people affected by Crohn's disease in Spain. A phenomenological approach. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Robinson CA. Trust, health care relationships, and chronic illness: a theoretical coalescence. Glob Qual Nurs Res 2016;3: 2333393616664823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilk AS, Platt JE. Measuring physicians’ trust: a scoping review with implications for public policy. Soc Sci Med 2016;165:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].García-Sanjuán S, Lillo-Crespo M, Richart-Martínez M, et al. Healthcare professionals’ views of the experiences of individuals living with Crohn's Disease in Spain. A qualitative study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0190980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Randell RL, Long MD, Martin CF, et al. Patient perception of chronic illness care in a large inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1428–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Safdar N, Abbo LM, Knobloch MJ, et al. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology: survey and qualitative research. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016;37:1272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.