Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common neurological disorders and is one of the main causes of disability. The prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran is reported to range from 5.3 to 89/ 100,000and 7 to 148.1/ 100,000, respectively. There are no systematic and meta-analysis studies on MS in Iran. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran using meta-analysis.

Method

A systematic review of the present study focused on MS epidemiology in Iran based on PRISMA guidelines for systematic review and meta-analysis. We searched eight international databases including Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Google Scholar search engine and six Persian databases for peer-reviewed studies published without time limit until May 2018. Data were analyzed using Comprehensive meta-analysis ver. 2 software. The review protocol has been registered in PROSPERO with ID: CRD42018114491.

Results

According to searching on different databases, 39 (15%) articles finalized. The prevalence of MS in Iran was estimated 29.3/ 100,000 (95%CI: 25.6–33.5) based on random effects model. The prevalence of MS in men and women was estimated to be 16.5/ 100,000 (95%CI: 13.7–23.4) and 44.8/ 100,000 (95%CI: 36.3–61.6), respectively. The incidence of MS in Iran was estimated to be 3.4/ 100,000 (95%CI: 1.8–6.2) based on random effects model. The incidence of MS in men was estimated to be 16.5/ 100,000 (95%CI: 13.7–23.4) and the incidence of MS in women was 44.8/ 100,000 (95%CI: 36.3–61.6). The meta-regression model for prevalence and incidence of MS was significantly higher in terms of year of study (p<0.001).

Conclusions

The results of this study can provide a general picture of MS epidemiology in Iran. The current meta-analysis showed that the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran is high and is rising over time.

1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative and immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the human central nervous system[1–4]. The clinical manifestations of MS include opiate neuritis, central paralysis, sensory imbalance, balance disorder, cognitive impairment, fatigue and sleep disorders[5]. Women are approximately 2–3 times more likely to suffer from MS[6], and most patients are 20 to 50 years old. Residents of Eastern Europe are more likely to suffer from MS compared with residents of Asia, Africa and Latin America[7, 8].

Iran is muslim country in the Middle East with a latitude of 32°00 and a longitude of 53°00 and has 31 provinces. There are various ethnic groups in Iran, including Fars, Kurds, Mazani, Gilak, Lor, Turks, Arabs, and Baluch, and are now united by Iranian culture. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008, around 1.3 million people had MS worldwide, while in 2013, the prevalence of MS was 73 per 100,000 in the world and was 60 per 100,000 in Iran[9, 10]. At the moment, Iran is well known for its high prevalence of MS in the world, whereas 15 years ago, it was assumed based on the MS slope hypothesis that Iran could be a low-risk area for MS with an incidence of less than 5 per 100,000 people[11–13].

Despite numerous studies, the main cause of MS is still unknown. According to a hypothesis, MS carries out an autoimmune attack against self-myelin or oligodendrocytic antigens by macrophages, deadly T cells, Lymphokines, and antibodies when they enter the brain[14]. A combination of genetic and environmental factors such as latitude, vitamin D use, skin color, migration, meal, smoking, occupational exposure to toxins, stress, or even recent studies of specific viral infections such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)[15] and bacterial infections like mycoplasma pneumonia [16, 17] may affect this disease[6, 15–19].

Basic epidemiological information helps to quickly identify, diagnose and control the disease complications[20]. One of the most important goals of meta-analysis, which results from the combination of existing studies, is to increase the volume of samples and the number of studies, to reduce the difference between the available parameters and the confidence interval, which ultimately leads to solving a problem, especially in the field of medicine. In fact, such studies are a vital link between research studies and decision-making at the bedside or policies[21–23].

The prevalence of MS in Iran has been reported to be 5.3–89 per 100,000[2, 5, 10, 11, 13, 21, 22, 24–46]. Considering the above-mentioned issues, controversy in the prevalence of MS, the lack of global access to the precise prevalence of MS in Iran, as well as expressing the final conclusion for policy making and operational planning in Iran, this study was conducted to estimate the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran by systematically reviewing all available documentations and their combination through meta-analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study protocol

The present systematic review focused on MS epidemiology in Iran based on PRISMA guidelines [47](S1 File) for systematic review and meta-analysis. All the steps of research, including search, selection of studies, qualitative assessment, and data extraction were done independently by two researchers. The agreement was reached by group discussion. The protocol of this review registered at: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews(PROSPERO) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) Identifier: CRD42018114491 [48, 49](S2 File).

2.2. Search strategy

The search was performed by two researchers independently. We searched the titles and abstracts of articles in six Persian databases including Scientific Information Database (SID) (http://www.sid.ir/), Barakat Knowledge Network System (http://health.barakatkns.com), (Iranian Research Institute for Information Science and Technology (IranDoc) (https://irandoc.ac.ir), Regional Information Center for Science and Technology (RICST) (http://en.ricest.ac.ir/), Magiran (http://www.magiran.com/), Iranian National Library (http://www.nlai.ir/) and eight international databases including Scopus, PubMed/Medline, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Embase, PsycINFO as well as Google Scholar search engine for peer-reviewed studies published without time limit until May 2018. The keywords used were 'incidence', 'prevalence', 'epidemiology', 'MS', 'multiple sclerosis' and 'Iran'. Boolean operators (AND & OR) were used to search by a combination of words. A sample of search strategy in PubMed database is shown in Appendix 1. The list of references of the studies was searched manually for additional reports.

2.3. Inclusion criteria (PICO)

Inclusion criteria according to PICO (Problem or Population, Interventions, Comparison and Outcome) [50, 51]: (1) Population: all Iranian population, in all age ranges and both genders; (2) Intervention: diagnosis of MS by Poser or McDonald criteria for confirmed MS; (3) Comparison: variable aimed for incidence and prevalence of MS such as gender, province, year of study and etc; (4) Outcome: Estimate the prevalence and incidence of MS.

2.4. Exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were all epidemiological studies on MS. The exclusion criteria included: 1. non-random sample size; 2. sample size other than Iranian population; 3. Articles published in languages other than Persian and English; 4. Not relevant to the subject; 5. qualitative studies; case report; review articles, case reports and interventional studies, and 6. duplicate articles.

2.5. Quality assessment

Researchers assessed the quality of the selected articles using a scoring system based on the 8-item the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomized studies [52] (S2 File). Each question was given a score between 0 and 1. Points 0–5, 6–7 and 8–9 were considered low quality, moderate quality and high quality, respectively. The minimum score for entering the quantitative meta-analysis process was 5 and the articles that acquired the minimum qualitative assessment score entered the process of data extraction and meta-analysis.

2.6. Screening and data extraction

Two independent researchers (Azami M, YektaKooshali MH) screened all the articles retrieved by the search strategy based on title and abstract for eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any contradiction between the two researchers was discussed and finally, a consensus was reached. In addition, if necessary, the full text was examined further for more clarification at this stage. In the next step, the researchers were provided with the full text of eligible articles. Each qualified full text was reviewed independently by two researchers and a third expert (Expert-epidemiologist) was there to provide consultations on disagreements between the two researchers.

Data extraction was done by the researchers using a pre-prepared form. The data for the study included the first author, year of publication, year of study, study setting, location, sample size, geographical area, province, the prevalence of MS and MS diagnostic method, which was extracted independently by two researchers and blinded to the author's name, institute, and journal. If necessity, further information, and raw data were requested by contacting the author (first author, corresponding author or contacting the authors' department) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies into the meta-analysis.

| Ref. | First author, Published Year * | Year of Study | Study Type | Place | Diagnostic criteria | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | Etemadifar M, 2006 | 2004–5 | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | McDonald | 3923255 |

| [67] | Sahraian MA, 2010 | 1999–2010 | Cross-sectional | Tehran | McDonald | 13422366 |

| [55] | Elhami SR, 2011 | 1989–2009 | Population based | Tehran | Poser (up to 2001) McDonald |

14103853 |

| [36] | Heydarpour P, 2013 | 1991–2011 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 14103853 |

| [45] | Saadatnia M, 2007 | 2003–6 | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | McDonald | 3923255 |

| [34] | Etemadifar M, 2010 | 2003–2010 | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | McDonald | 4804458 |

| [59] | Ghandehari K, 2010 | 2009 | Population based | RazaviKhorasan | McDonald | 5593079 |

| [59] | Ghandehari K, 2010 | 2009 | Population based | North Khorasan | McDonald | 811572 |

| [59] | Ghandehari K, 2010 | 2009 | Population based | Southern Khorasan | McDonald | 636420 |

| [2] | Abedini M, 2008 | 2007 | Cross-sectional | Mazandaran | McDonald | 2893087 |

| [35] | Hashemilar M, 2011 | 2005–9 | Population based | East Azerbaijan | McDonald | 3724620 |

| [40] | Moghtaderi A, 2012 | 1996–2006 | Cross-sectional | Sistan and Balouchestan | McDonald | 1346367 |

| [46] | Sharafaddinzadeh N, 2012 | 1997–2009 | Cross-sectional | Khuzestan | McDonald | 4200000 |

| [31] | Etemadifar M, 2013 | 2003–2013 | Population based | Isfahan | McDonald | 4879312 |

| [62] | Kalanie H, 2003 | 1996–2001 | Cross-sectional | Tehran | Poser | |

| [26] | Jajvandian R, 2011 | 2005–2011 | Population based | North Khorasan | - | 867727 |

| [54] | Ebrahimi HA, 2013 | 2013 | Population based | Kerman | - | 2947346 |

| [39] | Moghaddam AH, 2013 | 2013 | Population based | Kerman | McDonald | 207192 |

| [68] | Saman-Nezhad B,2012 | 2012 | Population based | Kermanshah | - | 851405 |

| [25] | Majdinasab N, 2012 | 2005–2011 | Population based | Khuzestan | McDonald | 4531720 |

| [43] | Rezaali S, 2013 | 2011 | Population based | Qom | Poser (up to 2001) and McDonald |

1151672 |

| [61] | Izadi S, 2015 | 2013 | Population based | Fars | - | 4551718 |

| [53] | Ashtari F, 2011 | 2007 | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | ||

| [37] | Maghzi A, 2010 | 2003–2007 | Population based | Isfahan | McDonald’s criteria and 2005 revisions |

4559256 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Isfahan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Isfahan | NR | 4879312 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Tehran) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Tehran | NR | 12183391 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Fars) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Fars | NR | 4596658 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Alborz) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Alborz | NR | 2412513 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Markazi) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Markazi | NR | 1413959 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (ChaharMahaa) | 2006–2013 | Population based | ChaharMahaal and Bakhtiari | NR | 895263 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (East Azerbaijan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | East Azerbaijan | NR | 3724263 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Semnan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Semnan | NR | 631218 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Hamadan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Hamadan | NR | 1758268 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Qom) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Qom | NR | 1151672 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (West Azerbaijan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | West Azerbaijan | NR | 3080576 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014(Yazd) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Yazd | NR | 1074428 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014(Kordestan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Kordestan | NR | 1493645 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014(Ardabil) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Ardabil | NR | 1248488 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Kohgiluyeh) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | NR | 658621 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Mazandaran) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Mazandaran | NR | 3073943 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Guilan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Guilan | NR | 2480874 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Kerman) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Kerman | NR | 2938988 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Khorasan-Razavi) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Razavi Khorasan | NR | 5994402 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Bushehr) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Bushehr | NR | 103949 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Ilam) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Ilam | NR | 557599 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Khuzestan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Khuzestan | NR | 4531720 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Golestan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Golestan | NR | 1777014 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Lorestan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Lorestan | NR | 1754244 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Zanjan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Zanjan | NR | 1015734 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014(Kermanshah) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Kermanshah | NR | 1945227 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Hormozgan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Hormozgan | NR | 1578183 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (North Khorasan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | North Khorasan | NR | 867727 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (South Khorasan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | South Khorasan | NR | 662534 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014(Qazvin) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Qazvin | NR | 1201565 |

| [32] | Etemadifar M, 2014 (Sistan and Baluchestan) | 2006–2013 | Population based | Sistan and Baluchestan | NR | 2534327 |

| [44] | Saadat SMS, 2013 | 2010 | Cross-sectional | Guilan | McDonald | 2480874 |

| [42] | Raiesi R, 2014 | 1991–2011 | Population based | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | McDonald | 895263 |

| [60] | Izadi S, 2015 | 2011 | Population based | Fars | NR | 4596658 |

| [5] | Nedjat S, 2006 | 2006 | Population based | Tehran | NR | 7803883 |

| [71] | Yousefi B, 2017 | 2005–2009 | Population based | East Azerbaijan | McDonald | 3724620 |

| [71] | Yousefi B, 2017 | 2010–2014 | Population based | East Azerbaijan | McDonald | 3909652 |

| [64] | Mazdeh M, 2016 | 2015–2018 | Population based | Hamadan | McDonald | |

| [70] | Tolou-Ghamari Z, 2015 | 2010–2014 | Population based | Isfahan | McDonald | 4879312 |

| [69] | Shahbeigi S, 2012 | 2010–2014 | Population based | 12 different major provinces of Iran | McDonald | 46695319 |

| [63] | Khamarnia M, 2016 | 2010 | Population based | Fars | McDonald | 4596658 |

| [63] | Khamarnia M, 2016 | 2011 | Population based | Fars | McDonald | 4596658 |

| [63] | Khamarnia M, 2016 | 2012 | Population based | Fars | McDonald | 4596658 |

| [13] | Dehghani R, 2015 | 2006 | Population based | All Iran | McDonald | 70495782 |

| [13] | Dehghani R, 2015 | 2011 | Population based | All Iran | McDonald | 75149669 |

| [57] | Eskandarieh Sh, 2017 | 2013 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 12559000 |

| [57] | Eskandarieh Sh, 2017 | 2014 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 12559000 |

| [57] | Eskandarieh Sh, 2017 | 2014 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 12559000 |

| [66] | Sabbagh S, 2017 | 2015–2018 | Population based | Khuzestan | McDonald | 957133 |

| [65] | Mousavizadeh A, 2017 | 2015–2018 | Population based | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | McDonald | 713052 |

| [56] | Eskandarieh Sh, 2017 | 2015 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 13267637 |

| [58] | Eskandarieh Sh, 2018 | 2017 | Population based | Tehran | McDonald | 13441124 |

NR: Not reported

* Repetitive studies have been included and estimated the prevalence and incidence for more than 1 year and also regions. Each data was considered separately because of assessing the slope of prevalence and incidence in the years and estimating which region is the highest or lowest.

2.7. Data analysis

To evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies, Cochran's Q and I2 tests were used. Heterogeneity was defined as I2> 50% and the Cochran's Q test was defined as < 0.05. Therefore, the random effects model was used to estimate the prevalence and incidence of MS with high heterogeneity. To estimate the effect of gender, we used the total number and the number of events (MS) in men and women groups and we calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. In this study, a sensitivity analysis was also performed to verify the stability of the data. In order to find the source of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was conducted in terms of geographic area, year of study, province, and study setting while a meta-regression model was used for the prevalence and incidence of MS in terms of year of studies. Begg and Egger’s tests were used to assess publication bias. Data were analyzed using Comprehensive meta-analysis ver. 2 software. P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics and methodological quality

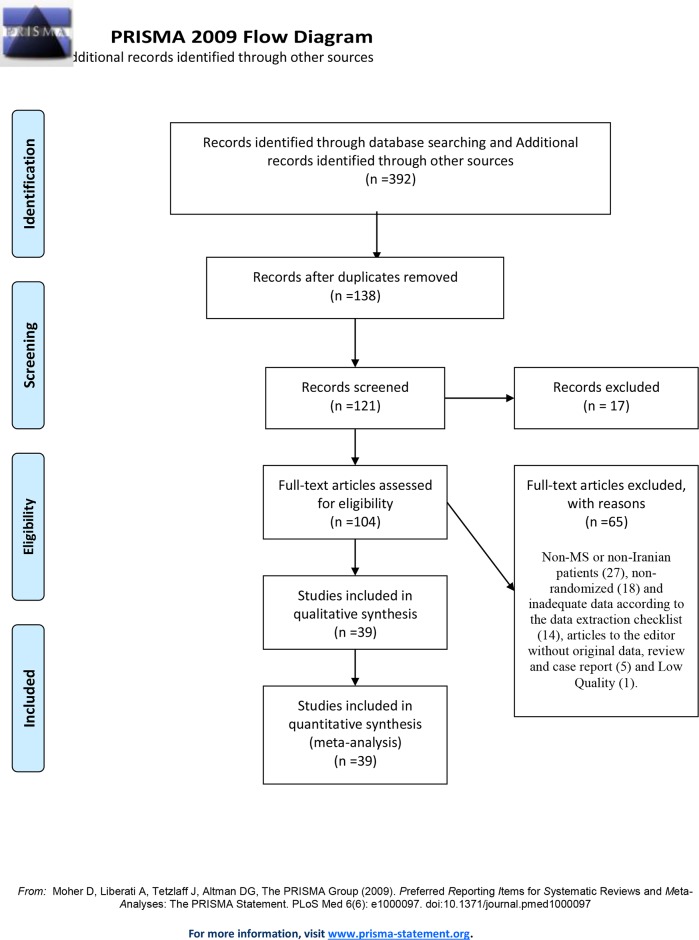

Of 392 studies found in the initial search using the search strategy, 138 potentially relevant studies were found to be eligible for retrieval and evaluation. By examining the full text of the studies, 65 studies were excluded due to non-MS or non-Iranian patients (27), non-randomized (18) and inadequate data according to the data extraction checklist (14), articles to the editor without original data, review and case report (5) and low quality (1). Finally, 39 articles (included 103 studies for prevalence and 34 studies for incidence) entered the meta-analysis process after qualitative assessment. The flow diagram of the identification and selection of studies is illustrated in (Fig 1) and the characteristics of studies are shown in (Table 1) [2, 5, 13, 25, 26, 31–37, 39, 40, 42–46, 53–71].

Fig 1. Study flow diagram.

3.2. Pooled prevalence of MS and sensitivity analysis

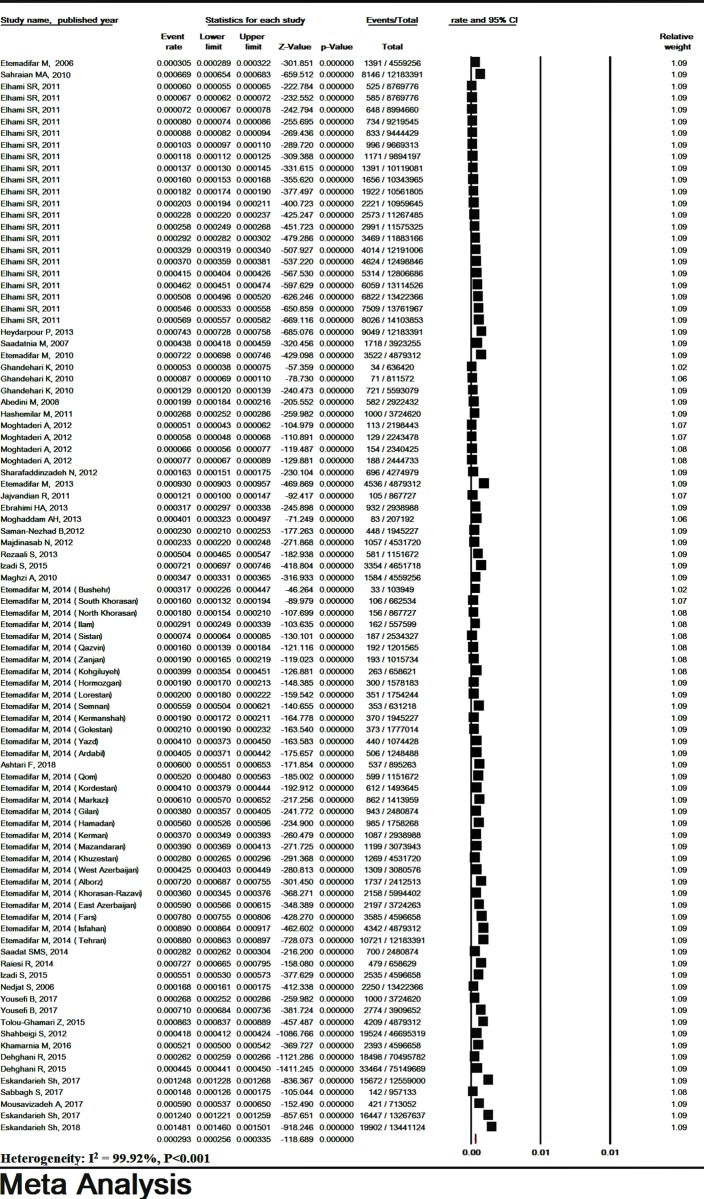

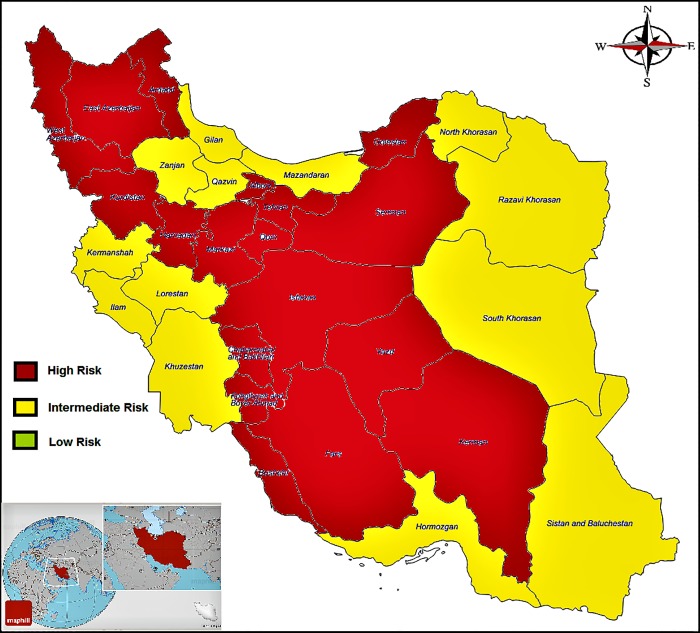

The total heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99.92% and P< 0.001). The prevalence of MS in Iran was estimated to be 29.3/ 100,000 (95% CI: 25.6–33.5) based on random effects model (Fig 2). The lowest and highest prevalence was found in studies in Southern Khorasan in 2009 (5.3/ 100,000) and Isfahan in 2013 (89/ 100,000), respectively (Figs 2 and 3). The sensitivity analysis of the prevalence of MS and its 95% CI was estimated irrespective of one study at a time, and the results showed that the pooled estimate was robust (S1 Fig).

Fig 2. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Iran.

Random effect model.

Fig 3. Distribution of MS in Iran based on geographical classification.

High risk 30/100,000 intermediate risk 5-30/100,000 and low risk 5/100,000 (as Wade scaled prevalence of MS globally [72]).

3.3. Subgroup analysis of MS prevalence based on region, province, study design, and year of study

The Subgroup analysis of MS prevalence in Iran is shown in (Table 2) and (S1–S6 Figs). Significant difference was observed in the prevalence of MS in the geographical regions (P< 0.001) (S2 Fig), province (P< 0.001) (S3 Fig), study design (P = 0.015) (S4 Fig), and year of study (P< 0.001) (S5 Fig).

Table 2. MS prevalence based on region, gender, provinces, year of study and design.

| Variable | Studies (N)* | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | 95% CI | Pooled (Per 100,000) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | All | I2 | P-Value | |||||

| Region | 12 different | 1 | 19524 | 46695319 | - | - | 41.2–42.4 | 42.4 |

| All Iran | 2 | 51962 | 145645451 | 99.97 | < 0.001 | 20.4–57.4 | 34.2 | |

| Center | 47 | 174229 | 368149059 | 99.94 | < 0.001 | 28.6–43.1 | 35.1 | |

| East | 8 | 3756 | 24011421 | 99.62 | < 0.001 | 5.3–18.1 | 9.8 | |

| North | 14 | 11640 | 32250226 | 99.50 | < 0.001 | 18.7–32.0 | 24.5 | |

| South | 13 | 17466 | 40504544 | 99.69 | < 0.001 | 25.6–44.6 | 33.8 | |

| West | 7 | 4237 | 12534786 | 98.01 | < 0.001 | 22.4–41.9 | 30.6 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 45.66, df(Q) = 6, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Gender | Male | 31 | 25711 | 76907082 | 94.77 | <0.0001 | 13.3–20.5 | 16.5 |

| Female | 31 | 74356 | 75432131 | 99.87 | < 0.001 | 36.2–55.4 | 44.8 | |

| Rate ratio of female to male: OR = 3.01 (2.79–2 = 3.24, P<0.001) | ||||||||

| Province | 12 different major provinces of Iran | 1 | 19524 | 46695319 | - | - | 41.2–42.4 | 41.8 |

| Alborz | 1 | 1737 | 2412513 | - | - | 68.7–75.5 | 72.0 | |

| All Iran | 2 | 51962 | 145645451 | 99.97 | < 0.001 | 20.4–57.4 | 34.2 | |

| Ardabil | 1 | 506 | 1248488 | - | - | 37.1–44.2 | 40.5 | |

| Bushehr | 1 | 33 | 103949 | - | - | 22.6–44.7 | 31.7 | |

| Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari | 1 | 537 | 895263 | - | - | 55.1–65.3 | 60.0 | |

| East Azerbaijan | 4 | 6971 | 1508315 | 99.74 | < 0.001 | 25.8–67.4 | 41.7 | |

| Fars | 4 | 11867 | 18441692 | 99.12 | < 0.001 | 52.3–76.9 | 63.4 | |

| Golestan | 1 | 373 | 1777014 | - | - | 19.0–23.2 | 21.0 | |

| Guilan | 2 | 1643 | 4961748 | 97.19 | < 0.001 | 24.5–43.9 | 32.8 | |

| Hamadan | 1 | 985 | 1758268 | - | - | 52.6–59.6 | 56.0 | |

| Hormozgan | 1 | 300 | 1578183 | - | - | 17.0–21.3 | 19.0 | |

| Ilam | 1 | 162 | 557599 | - | - | 24.9–33.9 | 29.1 | |

| Isfahan | 7 | 21302 | 32559015 | 99.79 | < 0.001 | 43.5–79.3 | 58.7 | |

| Kerman | 3 | 2102 | 6085168 | 85.39 | < 0.001 | 31.0–40.4 | 35.4 | |

| Kermanshah | 2 | 818 | 3890454 | 86.51 | < 0.001 | 17.4–25.3 | 21.0 | |

| Khuzestan | 4 | 3164 | 14295552 | 98.11 | < 0.001 | 15.3–26.2 | 20.1 | |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | 4 | 1163 | 2030302 | 96.72 | < 0.001 | 40.3–76.8 | 55.7 | |

| Kordestan | 1 | 612 | 1493645 | - | - | 37.9–44.4 | 41.0 | |

| Lorestan | 1 | 351 | 1754244 | - | - | 18.0–22.2 | 20.0 | |

| Markazi | 1 | 862 | 1413959 | - | - | 57.0–65.2 | 61.0 | |

| Mazandaran | 2 | 1781 | 5996375 | 99.43 | < 0.001 | 14.4–53.9 | 27.9 | |

| North Khorasan | 3 | 332 | 2547026 | 92.70 | < 0.001 | 8.3–18.8 | 12.5 | |

| Qazvin | 1 | 192 | 1201565 | - | - | 13.9–18.4 | 16.0 | |

| Qom | 2 | 1180 | 2303344 | 0 | 0.60 | 48.8–54.2 | 51.2 | |

| Razavi Khorasan | 2 | 2879 | 11587481 | 99.82 | < 0.001 | 7.9–59.0 | 21.6 | |

| Semnan | 1 | 353 | 631218 | - | - | 50.4–62.1 | 55.9 | |

| Sistan and Balouchestan | 5 | 771 | 11761406 | 75.34 | < 0.001 | 5.6–7.5 | 6.5 | |

| South Khorasan | 2 | 140 | 1298954 | 99.77 | < 0.001 | 3.2–27.3 | 9.3 | |

| Tehran | 28 | 146270 | 322611718 | 99.96 | < 0.001 | 20.7–36.7 | 27.6 | |

| West Azerbaijan | 1 | 1309 | 3080576 | - | - | 20.7–36.7 | 27.6 | |

| Yazd | 1 | 440 | 1074428 | - | - | 37.3–45.0 | 41.0 | |

| Zanjan | 1 | 193 | 1015734 | - | - | 16.5–21.9 | 19.0 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 2559.92, df(Q) = 32, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Year of study | < 1990 | 2 | 1110 | 17539552 | 69.13 | 0.072 | 5.7–7.0 | 6.3 |

| 1990–1994 | 5 | 4382 | 47222144 | 97.14 | < 0.001 | 7.6–10.8 | 9.1 | |

| 1995–1999 | 5 | 9763 | 53251981 | 98.62 | < 0.001 | 15.1–21.3 | 17.9 | |

| 2000–2004 | 5 | 20412 | 60955029 | 99.27 | < 0.001 | 27.9–38.6 | 32.8 | |

| 2005–2009 | 20 | 58545 | 182277428 | 99.82 | < 0.001 | 15.5–23.6 | 19.1 | |

| 2010–2014 | 51 | 151690 | 280165726 | 99.81 | < 0.001 | 35.8–45.8 | 40.5 | |

| 2015–2018 | 4 | 36912 | 28378946 | 99.76 | < 0.001 | 50.7–85.0 | 65.6 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 744.07, df(Q) = 6, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Study design | Population based | 82 | 266175 | 627821102 | 99.83 | < 0.001 | 27.0–35.9 | 31.1 |

| Cross-sectional | 10 | 16639 | 41969704 | 99.92 | < 0.001 | 11.7–27.3 | 17.9 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 5.89, df(Q) = 1, P = 0.015 | ||||||||

N: Number; CI: confidence interval

* Some studies have been included and estimated the prevalence and incidence for more than 1 year and also regions. Each data was considered separately because of assessing the slope of prevalence and incidence in the years and estimating which region is the highest or lowest.

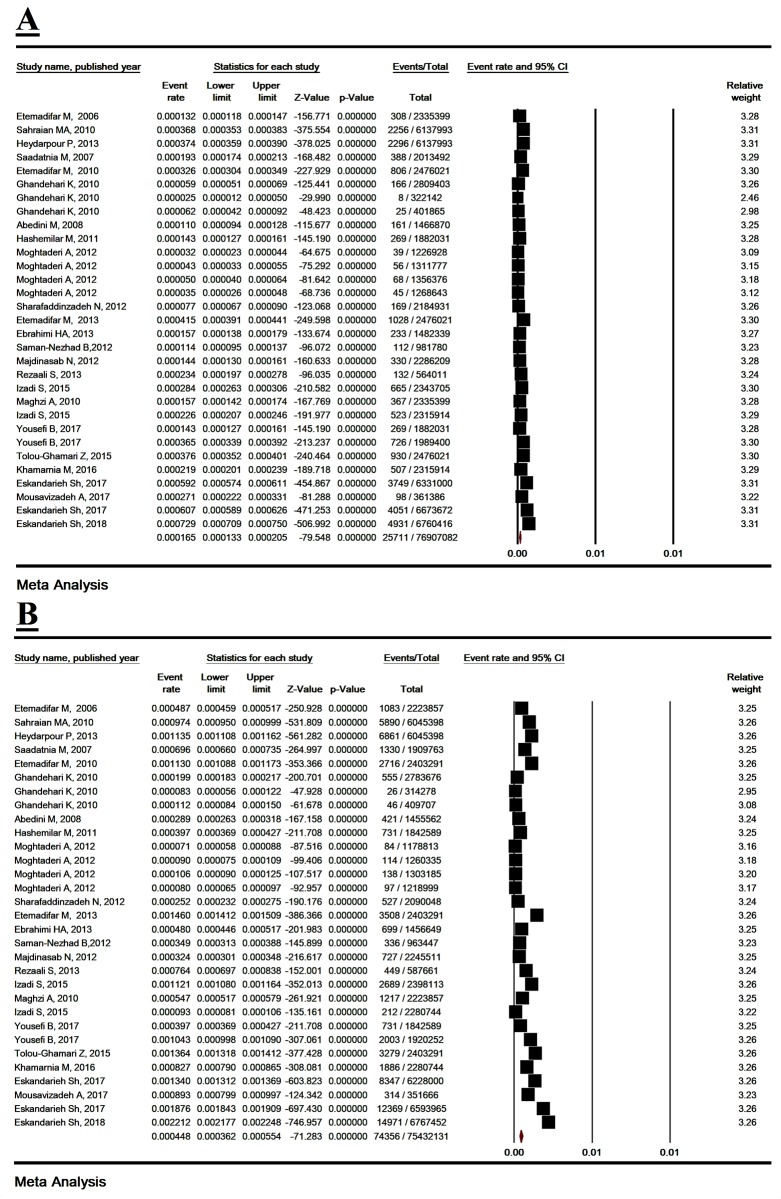

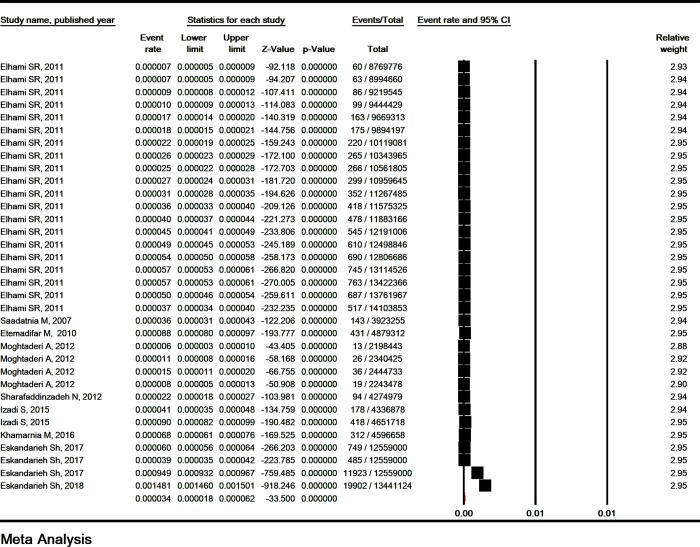

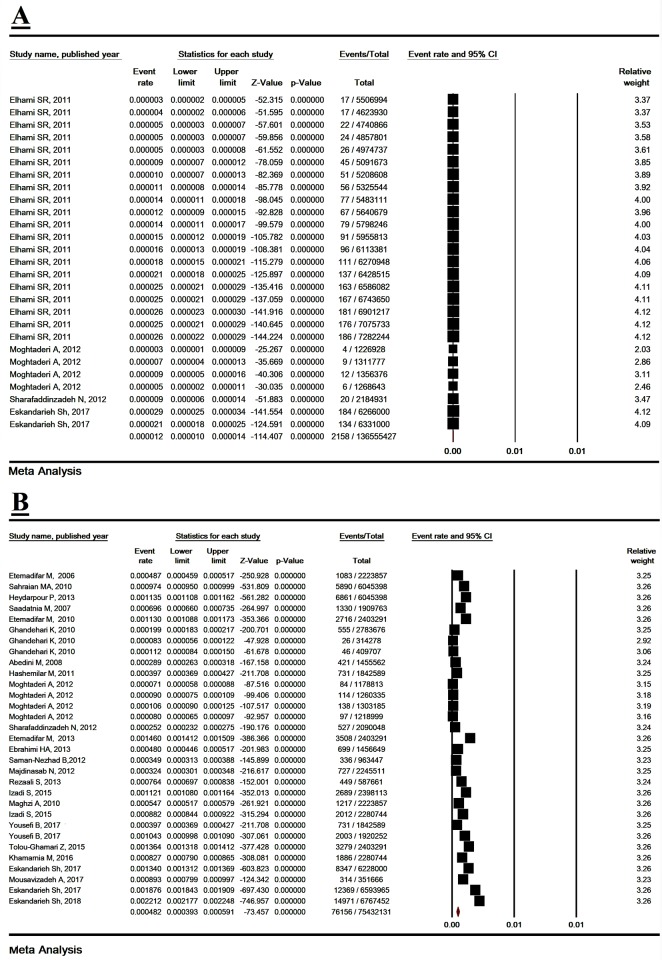

3.4. Prevalence of MS based on gender

The prevalence of MS in men and women was estimated to be 16.5/ 100,000 (95% CI: 13.7–23.4) and 44.8/ 100,000 (95% CI: 36.3–61.6), respectively (Fig 4). The OR female/ male of MS prevalence was estimated to be 3.01 (95% CI: 2.79–3.24, P< 0.001) (Table 2) (S6 Fig).

Fig 4.

The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in men (A) and women (B). Random effect model.

3.5. Pooled incidence of MS and sensitivity analysis

The total heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99.96% and P< 0.001). The incidence of MS in Iran was estimated according to 34 studies to be 3.4/ 100,000 (95% CI: 1.8–6.2) based on random effects model (Fig 5). The sensitivity analysis results are shown in (S7 Fig).

Fig 5. The incidence of multiple sclerosis in Iran.

Random effect model.

3.6. Subgroup analysis of MS incidence based on region, province, study design, and year of study

The Subgroup analysis of MS incidence in Iran is shown in (Table 3). Significant difference was observed in the prevalence of MS in the geographical regions (P < 0.001) (S8 Fig), province (P< 0.001) (S9 Fig) and year of study (P< 0.001) (S10 Fig), but study design was no significant difference (P = 0.123) (S11 Fig).

Table 3. MS incidence based on region, gender, provinces, year of study and design.

| Variable | Studies (N)* | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | 95% CI | Pooled (Per 100,000) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | All | I2 | P-Value | |||||

| Region | Center | 26 | 41134 | 284522333 | 99.97 | < 0.001 | 2.0–7.6 | 3.9 |

| East | 4 | 94 | 9227079 | 67.80 | 0.025 | 0.7–1.4 | 1.0 | |

| South | 4 | 1002 | 17860233 | 98.43 | < 0.001 | 2.9–8.2 | 4.9 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 28.94, df(Q) = 2, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Gender | Male | 31 | 2158 | 136555427 | 99.87 | < 0.001 | 1.0–1.4 | 1.2 |

| Female | 31 | 76156 | 75432131 | 99.87 | < 0.001 | 39.3–59.1 | 48.2 | |

| Rate ratio of female to male: OR = 3.04 (2.85–3.24, P< 0.001) | ||||||||

| Province | Fars | 3 | 908 | 13585254 | 97.40 | < 0.001 | 4.2–9.6 | 6.3 |

| Isfahan | 2 | 574 | 8802567 | 98.81 | < 0.001 | 2.4–13.5 | 5.7 | |

| Khuzestan | 1 | 94 | 4274979 | - | - | 1.8–2.7 | 2.2 | |

| Sistan and Balouchestan | 4 | 94 | 9227079 | 67.80 | 0.025 | 0.7–1.4 | 1.0 | |

| Tehran | 24 | 40560 | 275719766 | 99.97 | < 0.001 | 1.8–7.6 | 3.7 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 49.07, df(Q) = 4, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Year of study | < 1990 | 1 | 60 | 8769776 | - | - | 0.5–0.9 | 0.7 |

| 1990–1994 | 5 | 586 | 47222144 | 93.90 | < 0.001 | 0.8–1.6 | 1.2 | |

| 1995–1999 | 5 | 1402 | 53251981 | 79.37 | < 0.001 | 2.3–2.9 | 2.6 | |

| 2000–2004 | 6 | 2919 | 65291907 | 90.76 | < 0.001 | 3.9–5.0 | 4.4 | |

| 2005–2009 | 11 | 3474 | 76707337 | 98.09 | < 0.001 | 2.2–3.7 | 2.8 | |

| 2010–2014 | 5 | 13887 | 46925376 | 99.96 | < 0.001 | 2.0–56.7 | 10.6 | |

| 2015–2018 | 1 | 19902 | 13441124 | - | - | 146.0–150.1 | 148.1 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 10943.73, df(Q) = 6, P< 0.001 | ||||||||

| Study design | Population based | 27 | 41468 | 289305020 | 98.66 | < 0.001 | 2.0–7.7 | 4.0 |

| Cross-sectional | 7 | 762 | 22304625 | 99.97 | < 0.001 | 0.9–3.8 | 1.8 | |

| Test for subgroup differences: Q = 2.38, df(Q) = 1, P = 0.123 | ||||||||

N: Number; CI: confidence interval

* Some studies have been included and estimated the prevalence for more than 1 year and also regions. Each data was considered separately because of assessing the slope of prevalence in the years and estimating which region is the highest or lowest.

3.7. Incidence of MS based on gender

The incidence of MS in men was estimated to be 16.5/ 100,000 (95% CI: 13.7–23.4) and the incidence of MS in women was 44.8/ 100,000 (95% CI: 36.3–61.6) (Fig 6). The OR female/male of MS incidence was estimated to be 3.04 (2.85–3.24, P< 0.001) (Table 2) (S12 Fig).

Fig 6.

The incidence of multiple sclerosis in men (A) and women (B). Random effect model.

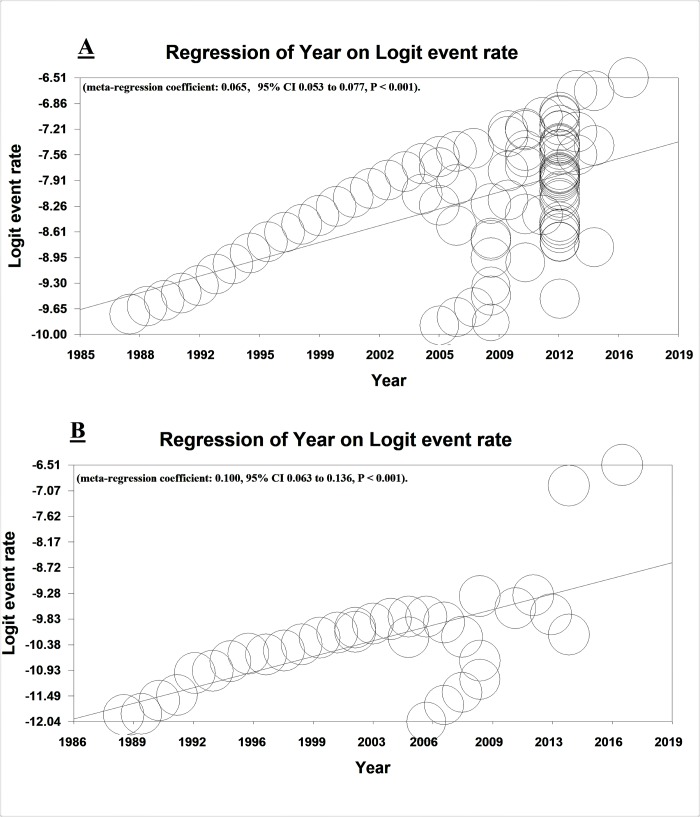

3.8. Meta-regression

The meta-regression model for prevalence and incidence of MS was significantly higher in terms of year of study [(meta-regression coefficient: 0.065, 95% CI 0.053 to 0.077, P< 0.001) for prevalence of MS and (meta-regression coefficient: 0.100, 95% CI 0.063 to 0.136, P< 0.001) for incidence of MS] (Fig 7). Moreover, the meta-regression model for prevalence and incidence of MS based on the year was also studied in men [(meta-regression coefficient: 0.202, 95% CI 0.157 to 0.248, P< 0.001) for prevalence of MS and (meta-regression coefficient: 0.065, 95% CI 0.046 to 0.0840, P< 0.001) for incidence of MS] and women [(meta-regression coefficient: 0.216, 95% CI 0.169 to 0.264, P< 0.001) for prevalence of MS and (meta-regression coefficient: 0.219, 95% CI 0.176 to 0.263, P< 0.001) for incidence of MS] and it was increasing significantly (S13 and S14 Figs).

Fig 7. Meta-regression of MS in Iran according to year of studies.

Prevalence (A) and incidence (B).

3.9. Publication bias

Publication bias in the studies of incidence (Egger< 0.001, and Begg’s< 0.001) and prevalence (Egger< 0.001, and Begg’s = 0.045) of MS was significant (S15 Fig).

4. Discussion

The present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the epidemiology of MS in Iran. According to the results of the present meta-analysis, the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran is estimated to be 29.3/ 100,000 and 3.4/ 100,000, which is more than some Middle Eastern countries (Oman, Libya, Lebanon, Iraq, Kuwait, and Tunisia)[73–78] and less than some other countries (UAE, city of Amman in Jordan and Saudi Arabia) [79–81]. However, it should be noted that most studies in our meta-analysis process were based on data from MS centers, and the lack of recording the information of some people with MS was due to non-compulsory membership in this center and the real prevalence of MS is expected to be greater than this figure. In 2016, Nasr et al. [41] investigated the prevalence of MS among Iranian migrants. The prevalence of MS among Iranian migrants was 21/ 100,000 in Mumbai (India) in 1985 and 433/ 100,000 in British Columbia (Canada) in 2012. In five different studies, the MS prevalence in the studied areas was reported from 1.33 in Mumbai (India) to 240 in British Columbia (Canada)[82–86]. The acculturative stress in migrants may help to relate the onset of illness and migration. The acculturative stress is the tension or pressure associated with the experience of a second culture that may have adverse effects on physical or mental health [87] and shows that stress and anxiety have a potential role in MS development[88]. Nish et al. recently showed in a study that acculturative stress is related to higher inflammatory markers in a Chinese migrant population[89].

In the past, the behavior and distribution of MS disease were associated with latitude and was reported to be lower in areas with a higher latitude. Overall, according to a report by WHO in 2008, the highest reported MS prevalence was in North America and Europe, and the lowest reported MS prevalence was in countries near the equator. However, this pattern is changing and areas with lower prevalence are changing to areas with higher prevalence[10, 15, 18, 90]. In the present study, there was a significant difference between the five geographical regions of Iran in terms of the prevalence and incidence of MS based on the results of the initial studies.

Based on the present meta-analysis, the OR of prevalence and incidence of MS in women was 2.52 and 3.04, respectively compared with men, which was a significant relationship (P< 0.001). This result is similar to the results in previous studies [21, 38, 55, 91–93].

According to the meta-regression model, the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran increased significantly (p< 0.001) with an increase in year of studies[21, 38, 91–93].

Various factors such as the lack of prevention and screening programs can be important factors in increasing the prevalence of the disease. In addition to changes in the pattern of food consumption, food quality has also changed a lot recently [10, 13, 30]. According to the WHO, the use of tobacco, fat, salt and sugar higher than the limit in foods that cause overweight and obesity, industrialization, urbanization and economic development can play a significant role in the development of chronic diseases[94]. In a study in the United States on 8983 MS patients, it was found that 25% of patients were obese and 31.3% were overweight. In addition, 18.2% were at risk of alcohol misuse by themselves or their relatives[95].

Since there are no particular laws and regulations on the purchase and use of chemicals in Iran, they are easily accessible to people and this may increase the risk of diseases such as MS, which is caused by exposure to chemicals. Although in some studies, contact with industrial solvents has been identified as a risk factor for MS, it has not yet been confirmed for sure[96–98].

The existence of particles such as PM10 in the air of Iranian cities[10, 28, 30, 99–102], natural radiation of radon from soil (Ramsar, Iran) [103] and unsupervised use of decorative stones and granite in Iran[27, 104] may increase the risk of MS. However, few studies have been conducted regarding the relationship between the above parameters and MS.

According to the Ministry of Health in Iran, the rate of smoking has risen to about 60 billion cigarettes per year[29, 105]. Inhaling cigarette smoke exacerbates the effect on chronic diseases [106, 107]. According to an ecological study by Dehghani et al. in Iran, the prevalence of illness is higher in provinces where cigarette smoking is higher among males[13]. Since cigarette smoking increases the frequency and duration of respiratory infections and it causes MS relapse[37], the risk of cigarette smoking for MS with an OR of 1.55, 95% CI [1.48–1.62], P<0.001 was confirmed in the recent meta-analysis.

According to the WHO, the prevalence of MS is higher in countries with higher income levels. However, the diseases may progress more in less developed countries due to less access to diagnostic facilities, although the disparity is so high that scarce diagnostic facilities cannot be considered as the main factor[108].

Studies have shown that vitamin D deficiency is inversely related to the risk of MS [109, 110] and its deficiency is an epidemic, which affects 20–25% of the population in Asia, America, Canada, Europe and Australia[111]. This is becoming acuter in the Middle East because of changes in lifestyle conditions and less sunlight[112]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in Iran have reported a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency[91, 92].

The period of MS is often unpredictable, but some factors can predict a patient's prognosis. The indicators of a good prognosis can be female gender, those with a history of disease before the age of 35, those who were only attacked in one area of the brain, those who had no brain stem involvement and patients who had recovered after the attacks[10]. To achieve successful symptom control, multiple controls are needed to prevent or stop the symptoms. Effective communication, training, exercise, professional support, and pharmacological interventions are vital for effective control of multiple sclerosis symptoms.

5. Limitations

1. The insensitivity of internal databases to operators “AND” and “OR” to search for the combination. 2. Since Tehran is the main medical center of many cities and provinces, patients in the studies in Tehran, are not just from Tehran.

3. No separation of rural and urban prevalence of MS

6. Conclusion

The present meta-analysis showed that the prevalence and incidence of MS in Iran is high (as Wade scaled prevalence of MS globally[72]) and is rising over time. The results of this study provide useful information for neurologists and health policy makers and can provide a general overview of MS epidemiology in Iran.

Appendix 1: PubMed search strategy

Exp. 'Epidemiology'

Exp.'Prevalence'

Exp.'Incidence’'

Exp.MS'

Exp.'Multiple Sclerosis '

Exp.'Iran'

1 OR 2 OR 3

4 OR 5

7 AND 8 AND 9

Supporting information

(DOC)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

The OR female to male of MS prevalence (A) and incidence (B).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran in terms of men (A) and women (B).

(TIF)

Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran in terms of men (A) and women (B).

(TIF)

Publication bias for prevalence studies (A) and update (B) multiple sclerosis in Iran.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

Hereby, we express our deepest sense of gratitude to Ilam University of Medical Sciences for their scientific supports.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

About funding, honestly we didn’t fund by any institutions and individual persons.

References

- 1.Ascherio A, Munger K, editors. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: from risk factors to prevention. Seminars in neurology; 2008: Thieme Medical Publishers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abedidni M, Habibi Saravi R, Zarvani A, Farahmand M. Epidemiologic study of multiple sclerosis in Mazandaran, Iran, 2007. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2008;18(66):82–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumelahti M-L, Hakama M, Elovaara I, Pukkala E. Causes of death among patients with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2010;16(12):1437–42. 10.1177/1352458510379244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsaransing GSM, De Keyser J. Benign course in multiple sclerosis: a review. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2006;113(6):359–69. Epub 2006/05/06. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00637.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nedjat S, Montazeri A, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, Nabavi N, Nedjat F. Multiple sclerosis quality of life comparing to healthy people. Iran J Epidemiol. 2006;1(4):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer JM, McCombe PA. Role of gender in multiple sclerosis: clinical effects and potential molecular mechanisms. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;234(1–2):7–18. Epub 2011/04/09. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.03.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Runmarker B, Andersen O. Prognostic factors in a multiple sclerosis incidence cohort with twenty-five years of follow-up. Brain. 1993;116 (Pt 1)(1):117–34. Epub 1993/02/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, Noseworthy J, Carriere W, Baskerville J, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. I. Clinical course and disability. Brain. 1989;112 (Pt 1)(1):133–46. Epub 1989/02/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Mental health, Neurology Disorder: public health challenges [Online]. [cited 2011]; Available from:URL: http://www.worldmsday.org/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2013/05/MS_v10.pdf

- 10.dehghani r, kazemi moghaddam v. Investigation of the possible causes of the increased prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a review. Pars of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences. 2015;13(2):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtzke JF. A reassessment of the distribution of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1975;51(2):110–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtzke JF. Epidemiologic contributions to multiple sclerosis: an overview. Neurology. 1980;30(7 Pt 2):61–79. Epub 1980/07/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehghani R, Yunesian M, Sahraian MA, Gilasi HR, Kazemi Moghaddam V. The Evaluation of Multiple Sclerosis Dispersal in Iran and Its Association with Urbanization, Life Style and Industry. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(6):830–8. Epub 2015/08/11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetz CG. Textbook of clinical neurology: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrie RA. Environmental risk factors in multiple sclerosis aetiology. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(12):709–18. Epub 2004/11/24. 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00933-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Contini C, Seraceni S, Cultrera R, Castellazzi M, Granieri E, Fainardi E. Molecular detection of Parachlamydia-like organisms in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14(4):564–6. Epub 2008/06/20. 10.1177/1352458507085796 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fainardi E, Castellazzi M, Seraceni S, Granieri E, Contini C. Under the microscope: focus on Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5(1):60–70. Epub 2008/02/22. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ascherio A, Munger KL. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Part II: Noninfectious factors. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(6):504–13. Epub 2007/05/12. 10.1002/ana.21141 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milo R, Kahana E. Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(5):A387–94. Epub 2009/11/26. 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olek M. Multiple sclerosis: etiology, diagnosis, and new treatment strategies: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansouri A, Norouzi S, YektaKooshali MH, Azami M. The relationship of maternal subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy and preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2017;19(40):69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saffari M, Sanaeinasab H, Pakpour AH. How to Do a Systematic Review Regard to Health: A Narrative Review. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2013;1(1):51–61. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberati A, Taricco M. How to do and report systematic reviews and meta-analysis Research in Physical & Rehabilitation Medicine Pavia: Maugeri Foundation Books; 2010:137–64. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diane P Calello, Alex Troncoso, Overview of rodenticide poisoning, (2017, December). https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-rodenticide-poisoning.

- 25.Majdinasab N, Nakhostin-Mortazavi A, Alemzadeh-Ansari MH. Epidemiologic features of multiple sclerosis in south-western Iran; in 28th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. Lyon, France, 2012. Mult Scler. 2012 Oct;18(4 Suppl):9–542. [PubMed]

- 26.Jajvandian R, Ali Babai A, Torabzadeh S, Rakhshi N, Nikravesh A. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in North Khorasan province, n orthern Iran; in 5 th Joint Triennial Congress of the European and Americas Committees for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. Mult Scler. 2011. October;17(10 Suppl):S9–524.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehghani R, Fathabadi N, Kardan M, Mohammadi M, Atoof F. Survey of Gamma Dose and Radon Exhalation Rate from Soil Surface of High Background Natural Radiation Areas in Ramsar, Iran. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2013;15(9):81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehghani R, Takht Firuze M, Hossein Dust G, Mosayiebi M, editors. Survey of air quality health based on air quality index in Kashan 2012. The Sixteenth Iranian National Conference on Environmental Health, Tabriz university of medical sciences; 2013.

- 29.Dehghani R, Takht Firuze M, Yeganeh M, Meqdadi M, Musavi G, editors. Study of cigarette smoking in the Ardestan in 2011. The Sixteenth Iranian National Conference on Environmental Health, Tabriz university of medical sciences; 2013.

- 30.Dehghani R, zarghi I, Hajijafari T, Falahnia M, Hosseni M. Investigation into level of iodine in market iodized salt in Kashan, 2010. Journal of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. 2013;5(3):593–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etemadifar M, Abtahi SH, Akbari M, Murray RT, Ramagopalan SV, Fereidan-Esfahani M. Multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran: an update. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1145–7. Epub 2013/12/12. 10.1177/1352458513516531 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etemadifar M, Izadi S, Nikseresht A, Sharifian M, Sahraian MA, Nasr Z. Estimated prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Iran. Eur Neurol. 2014;72(5–6):370–4. Epub 2014/10/25. 10.1159/000365846 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Etemadifar M, Janghorbani M, Shaygannejad V, Ashtari F. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(1):39–44. Epub 2006/06/29. 10.1159/000094235 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etemadifar M, Maghzi AH. Sharp increase in the incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Mult Scler. 2011;17(8):1022–7. Epub 2011/04/05. 10.1177/1352458511401460 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashemilar M, Savadi Ouskui D, Farhoudi M, Ayromlou H, Asadollahi A. Multiple sclerosis in East-Azerbaijan, north west Iran. Neurology Asia. 2011;16(2):127–31. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heydarpour P, Mohammad K, Yekaninejad MS, Elhami SR, Khoshkish S, Sahraian MA. Multiple sclerosis in Tehran, Iran: a joinpoint trend analysis. Mult Scler. 2014;20(4):512 Epub 2013/07/10. 10.1177/1352458513494496 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maghzi AH, Ghazavi H, Ahsan M, Etemadifar M, Mousavi S, Khorvash F, et al. Increasing female preponderance of multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran: a population-based study. Mult Scler. 2010;16(3):359–61. Epub 2010/01/21. 10.1177/1352458509358092 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansouri A, Mojarad MRA, Badfar G, Abasian L, Rahmati S, Kooti W, et al. Epidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii among blood donors in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moghaddam AH, Iranmanesh F, Vakilian A, editors. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Rafsanjan: South of Iran. Multiple Sclerosis Journal; 2013: SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD 1 OLIVERS YARD, 55 CITY ROAD, LONDON EC1Y 1SP, ENGLAND. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moghtaderi A, Rakhshanizadeh F, Shahraki-Ibrahimi S. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in southeastern Iran. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(3):304–8. Epub 2012/06/22. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.05.032 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nasr Z, Majed M, Rostami A, Sahraian MA, Minagar A, Amini A, et al. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Iranian emigrants: review of the evidence. Neurol Sci. 2016;37(11):1759–63. Epub 2016/06/29. 10.1007/s10072-016-2641-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raiesi r, Baiat a, Karami j, Sarkaregar-Ardakani a, Katorani s, Ramezannezhad p, et al. Spatial distribution of multiple sclerosis disease. Journal of Shahrekord Uuniversity of Medical Sciences. 2013;15(4):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezaali S, Khalilnezhad A, Naser Moghadasi A, Chaibakhsh S, Sahraian MA. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Qom: Demographic study in Iran. Iran J Neurol. 2013;12(4):136–43. Epub 2013/11/20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saadat SMS, Hosseininezhad M, Bakhshayesh B, Saadat SNS, Nabizadeh SP. Prevalence and predictors of depression in Iranian patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurological Sciences. 2014;35(5):735–40. 10.1007/s10072-013-1593-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saadatnia M, Etemadifar M, Maghzi AH. Multiple sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:357–75. Epub 2007/05/29. 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79016-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharafaddinzadeh N, Moghtaderi A, Majdinasab N, Dahmardeh M, Kashipazha D, Shalbafan B. The influence of ethnicity on the characteristics of multiple sclerosis: a local population study between Persians and Arabs. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2013;115(8):1271–5. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Editors PLM. Best practice in systematic reviews: the importance of protocols and registration. PLoS Med. 2011;8(2):e1001009 Epub 2011/03/03. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahmmudi Leliy, Shohani Masoumeh, Mohammad Hossein YektaKooshali Milad Azami. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2018. CRD42018114491 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018114491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.JafariNezhad A, YektaKooshali MH. Lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202360 10.1371/journal.pone.0202360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club. 1995;123(3):A12–A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poorolajal J, Cheraghi Z, Irani AD, Rezaeian S. Quality of Cohort Studies Reporting Post the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement. Epidemiol Health. 2011;33:e2011005 Epub 2011/07/01. 10.4178/epih/e2011005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashtari F, Shaygannejad V, Heidari F, Akbari M. Prevalence of Familial Multiple Sclerosis in Isfahan, Iran. Journal of Isfahan Medical School; Vol 29, No 138: 2nd week July 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ebrahimi H, Sedighi B. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis and environmental factors in Kerman province, Iran. Neurology Asia. 2013;18(4):385–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elhami SR, Mohammad K, Sahraian MA, Eftekhar H. A 20-year incidence trend (1989–2008) and point prevalence (March 20, 2009) of multiple sclerosis in Tehran, Iran: a population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(3):141–7. Epub 2011/04/22. 10.1159/000324708 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eskandarieh S, Allahabadi NS, Sadeghi M, Sahraian MAJBn. Increasing prevalence of familial recurrence of multiple sclerosis in Iran: a population based study of Tehran registry 1999–2015. 2018;18(1):15 10.1186/s12883-018-1019-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eskandarieh S, Heydarpour P, Elhami SR, Sahraian MA. Prevalence and Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(5):699–704. Epub 2017/06/01. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eskandarieh S, Molazadeh N, Moghadasi AN, Azimi AR, Sahraian MA. The prevalence, incidence and familial recurrence of multiple sclerosis in Tehran, Iran. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:143 Epub 2018/08/04. 10.1016/j.msard.2018.07.023 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghandehari K, Riasi HR, Nourian A, Boroumand AR. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in north east of Iran. Mult Scler. 2010;16(12):1525–6. Epub 2010/06/11. 10.1177/1352458510372150 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Izadi S, Nikseresht A, Poursadeghfard M. Epidemiology of Multiple Sclerosis in Fars Province. Iranian Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;10(2):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Izadi S, Nikseresht AR, Poursadeghfard M, Borhanihaghighi A, Heydari ST. Prevalence and Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis in Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2015;40(5):390–5. PMC4567597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalanie H, Gharagozli K, Kalanie AR. Multiple sclerosis: report on 200 cases from Iran. Mult Scler. 2003;9(1):36–8. Epub 2003/03/06. 10.1191/1352458503ms887oa . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khammarnia M, Kassani A, Izadi E, Setoodehzadeh FJBMRCB. Registry-Based Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis in Southwestern Iran, 2001–2014. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mazdeh M, Khazaei M, Hashemi-Firouzi N, Ghiasian MJAJoNPP. Frequency of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Among Relatives of MS Patients in Hamadan Society, Iran. 2016;3(1). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mousavizadeh A, Dastoorpoor M, Naimi E, Dohrabpour K. Time-trend analysis and developing a forecasting model for the prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, southwest of Iran. Public Health. 2018;154:14–23. Epub 2017/11/13. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.10.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sabbagh S, Radmehr M, Sanjary H, Nosratzehi MJDPL. Multiple Sclerosis in South Iran: Prevalence and Risk Factors. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sahraian MA, Khorramnia S, Ebrahim MM, Moinfar Z, Lotfi J, Pakdaman H. Multiple sclerosis in Iran: a demographic study of 8,000 patients and changes over time. Eur Neurol. 2010;64(6):331–6. Epub 2010/11/13. 10.1159/000321649 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saman-Nezhad B, Rezaee T, Bostani A, Najafi F, Aghaei A. Epidemiological Characteristics of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in Kermanshah, Iran in 2012% J Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2013;23(104):97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shahbeigi S, Fereshtenejad SM, Jalilzadeh G, Heydari MJN. The Nationwide Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran (P01. 143). 2012;78(1 Supplement):P01. 143–P01. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tolou-Ghamari ZJAoN. Preliminary Study of Differences Between Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Isfahan and its’ Rural Provinces. 2015;2(4). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yousefi B, Vahdati SS, Mazouchian H, Hesari RD. Epidemiological Survey of Multiple Sclerosis in East-Azerbaijan Province, Iran, 2014. Internal Medicine and Medical Investigation Journal. 2017;2(2):42–8. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wade BJ. Spatial analysis of global prevalence of multiple sclerosis suggests need for an updated prevalence scale. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014:124578 Epub 2014/04/03. 10.1155/2014/124578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamout B, Barada W, Tohme RA, Mehio-Sibai A, Khalifeh R, El-Hajj T. Clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis in Lebanon. J Neurol Sci. 2008;270(1–2):88–93. Epub 2008/03/28. 10.1016/j.jns.2008.02.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al-Hashel J, Besterman AD, Wolfson C. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31(2):129–37. Epub 2008/08/22. 10.1159/000151514 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Araji A, Mohammed AI. Multiple sclerosis in Iraq: does it have the same features encountered in Western countries? Journal of the neurological sciences. 2005;234(1):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Radhakrishnan K, Ashok PP, Sridharan R, Mousa ME. Prevalence and pattern of multiple sclerosis in Benghazi, north-eastern Libya. J Neurol Sci. 1985;70(1):39–46. Epub 1985/08/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tharakan JJ, Chand RP, Jacob PC. Multiple sclerosis in Oman. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2005;10(3):223–5. Epub 2005/07/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Romdhane NA, Hamida MB, Mrabet A, Larnaout A, Samoud S, Hamda AB, et al. Prevalence study of neurologic disorders in Kelibia (Tunisia). Neuroepidemiology. 1993;12(5):285–99. 10.1159/000110330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inshasi J, Thakre M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121(7):393–8. Epub 2011/04/06. 10.3109/00207454.2011.565893 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bohlega S, Inshasi J, Al Tahan AR, Madani AB, Qahtani H, Rieckmann P. Multiple sclerosis in the Arabian Gulf countries: a consensus statement. J Neurol. 2013;260(12):2959–63. Epub 2013/03/19. 10.1007/s00415-013-6876-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.El-Salem K, Al-Shimmery E, Horany K, Al-Refai A, Al-Hayk K, Khader Y. Multiple sclerosis in Jordan: A clinical and epidemiological study. J Neurol. 2006;253(9):1210–6. Epub 2006/05/02. 10.1007/s00415-006-0203-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wadia NH, Bhatia K. Multiple sclerosis is prevalent in the Zoroastrians (Parsis) of India. Annals of neurology. 1990;28(2):177–9. 10.1002/ana.410280211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guimond C, Dyment DA, Ramagopalan SV, Giovannoni G, Criscuoli M, Yee IM, et al. Prevalence of MS in Iranian immigrants to British Columbia, Canada. J Neurol. 2010;257(4):667–8. Epub 2009/12/17. 10.1007/s00415-009-5417-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ahlgren C, Lycke J, Oden A, Andersen O. High risk of MS in Iranian immigrants in Gothenburg, Sweden. Mult Scler. 2010;16(9):1079–82. Epub 2010/07/31. 10.1177/1352458510376777 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berg-Hansen P, Moen SM, Sandvik L, Harbo HF, Bakken IJ, Stoltenberg C, et al. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis among immigrants in Norway. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2015;21(6):695–702. 10.1177/1352458514554055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guimond C, Lee JD, Ramagopalan SV, Dyment DA, Hanwell H, Giovannoni G, et al. Multiple sclerosis in the Iranian immigrant population of BC, Canada: prevalence and risk factors. Mult Scler. 2014;20(9):1182–8. Epub 2014/01/15. 10.1177/1352458513519179 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeVylder JE, Oh HY, Yang LH, Cabassa LJ, Chen F-p, Lukens EP. Acculturative stress and psychotic-like experiences among Asian and Latino immigrants to the United States. Schizophrenia research. 2013;150(1):223–8. 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Azimian M, Shahvarughi-Farahani A, Rahgozar M, Etemadifar M, Nasr Z. Fatigue, depression, and physical impairment in multiple sclerosis. Iran J Neurol. 2014;13(2):105–7. Epub 2014/10/09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fang CY, Ross EA, Pathak HB, Godwin AK, Tseng M. Acculturative stress and inflammation among Chinese immigrant women. Psychosomatic medicine. 2014;76(5):320 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ascherio A, Munger KL. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Part I: the role of infection. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(4):288–99. Epub 2007/04/21. 10.1002/ana.21117 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Azami M, Badfar G, Shohani M, Mansouri A, YektaKooshali MH, Sharifi A, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Mean Vitamin D Concentration among Pregnant Women and Newborns in Iran. Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2017;20(4):76–87. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Azami M, Beigom Bigdeli Shamloo M, Parizad Nasirkandy M, Veisani Y, Rahmati S, YektaKooshali MH, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. koomesh. 2017;19(3):505–14. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Azami M, Sayehmiri K, YektaKooshali M, HafeziAhmadi M. The prevalence of tuberculosis among Iranian elderly patients admitted to the infectious ward of hospital: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of mycobacteriology. 2016;5:S199–S200. 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tunstall-Pedoe H. Preventing Chronic Diseases. A Vital Investment: WHO Global Report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. pp 200 CHF 30.00. ISBN 92 4 1563001. Also published on http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/en. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pekmezovic T, Drulovic J, Milenkovic M, Jarebinski M, Stojsavljevic N, Mesaros S, et al. Lifestyle factors and multiple sclerosis: A case-control study in Belgrade. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(4):212–6. Epub 2006/11/11. 10.1159/000096853 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Riise T, Moen BE, Kyvik KR. Organic solvents and the risk of multiple sclerosis. Epidemiology. 2002;13(6):718–20. Epub 2002/11/01. 10.1097/01.EDE.0000030721.86848.C2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mortensen JT, Bronnum-Hansen H, Rasmussen K. Multiple sclerosis and organic solvents. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):168–71. Epub 1998/03/21. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Koch MW, Metz LM, Agrawal SM, Yong VW. Environmental factors and their regulation of immunity in multiple sclerosis. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013;324(1):10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kelishadi R, Poursafa P. Air pollution and non-respiratory health hazards for children. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(4):483–95. Epub 2010/08/30. 10.5114/aoms.2010.14458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gregory AC 2nd, Shendell DG, Okosun IS, Gieseker KE. Multiple Sclerosis disease distribution and potential impact of environmental air pollutants in Georgia. Sci Total Environ. 2008;396(1):42–51. Epub 2008/04/25. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.01.065 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Talebi S, Tavakoli T, Ghinani A. Levels of PM10 and its chemical composition in the atmosphere of the city of Isfahan. Iran J Chem Engin. 2008;3:62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Halek F, Kavouci A, Montehaie H. Role of motor-vehicles and trend of air borne particulate in the Great Tehran area, Iran. Int J Environ Health Res. 2004;14(4):307–13. Epub 2004/09/17. 10.1080/09603120410001725649 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bolviken B, Celius EG, Nilsen R, Strand T. Radon: a possible risk factor in multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22(1):87–94. Epub 2003/02/05. 10.1159/000067102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fathabadi N, Mohammadi M, Dehghani R, Kardan M, Atoof F, Farahani M, et al. The effects of environmental parameters on the radon exhalation rate from the ground surface in HBRA in Ramsar with a regression model. Life Science Journal. 2013;10(SUPPL.):563–9. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Non- Disease Risk Factor InfoBase [Internet]. Islamic Republic of IRAN—Ministry of Health & Medical Education—Undersecretary for Health—Center for Disease Management 2009. Available from: URL: http://www.ncdinfobase.ir/english/.

- 106.Rubin DH, Krasilnikoff PA, Leventhal JM, Weile B, Berget A. Effect of passive smoking on birth-weight. Lancet. 1986;2(8504):415–7. Epub 1986/08/23. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sundstrom P, Nystrom L, Hallmans G. Smoke exposure increases the risk for multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(6):579–83. Epub 2008/05/14. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02122.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Organization WH. Atlas: multiple sclerosis resources in the world 2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 109.KAZEMI SD, JOZANIKOHAN Z, ASSAR O, LOTFIAN I. The effect of vitamin D deficiency on coronary artery stenosis severity in angioplasty patients in Baqiatallah hospital in 2013. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smolders J, Peelen E, Thewissen M, Menheere P, Tervaert JW, Hupperts R, et al. The relevance of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms for vitamin D research in multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(7):621–6. Epub 2009/04/28. 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.02.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S–6S. Epub 2008/04/11. 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fields J, Trivedi NJ, Horton E, Mechanick JI. Vitamin D in the Persian Gulf: integrative physiology and socioeconomic factors. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2011;9(4):243–50. Epub 2011/09/09. 10.1007/s11914-011-0071-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

The OR female to male of MS prevalence (A) and incidence (B).

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran in terms of men (A) and women (B).

(TIF)

Incidence of Multiple Sclerosis in Iran in terms of men (A) and women (B).

(TIF)

Publication bias for prevalence studies (A) and update (B) multiple sclerosis in Iran.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.