Abstract

Epidemiological studies have reported associations of air pollution exposures with various neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit and schizophrenia, all of which are male-biased in prevalence. Our studies of early postnatal exposure of mice to the ultrafine particle (UFP) component of air pollution, considered the most reactive component, provide support for these epidemiological associations, demonstrating male-specific or male-biased neuropathological changes and cognitive and impulsivity deficits consistent with these disorders. Since these neurodevelopmental disorders also include altered social behavior and communication, the current study examined the ability of developmental UFP exposure to reproduce these social behavior deficits and to determine whether any observed alterations reflected changes in steroid hormone concentrations. Elevated plus maze, social conditioned place preference, and social novelty preference were examined in adult mice that had been exposed to concentrated (10–20×) ambient UFPs averaging approximately 45 ug/m3 particle mass concentrations from postnatal day (PND) 4–7 and 10–13 for 4 h/day. Changes in serum testosterone (T) and corticosterone where measured at postnatal day (P)14 and approximately P120. UFP exposure decreased serum T concentrations on PND 14 and social nose-to-nose sniff rates with novel males in adulthood, suggesting social communication deficits in unfamiliar social contexts. Decreased sniff rates were not accounted for by alterations in fear-mediated behaviors and occurred without overt deficits in social preference, recognition or communication with a familiar animal or alterations in corticosterone. Adult T serum concentrations were positively correlated with nose to nose sniff rates. Collectively, these studies confirm another feature of male-biased neurodevelopmental disorders following developmental exposures to even very low levels of UFP air pollution that could be related to alterations in sex steroid programming of brain function.

Keywords: Air pollution, Sex-specific, Testosterone, Fetal origins, Social behavior

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder(s) (ASDs) are a group of profound, intractable, and highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorders that impact 1 in 68 children and result in lifelong behavioral deficits including impairment in communication, social interaction, and repetitive/stereotyped behaviors (Neggers, 2014). Identification of specific environmental etiological risk factors for ASDs remains elusive, in part due to this heterogeneity. Although it is clear that genetics contributes to the development of ASD (Huguet et al., 2013), it is also recognized that genetics cannot fully account for the disorder, especially in light of its rising incidence over recent decades (Neggers, 2014; Hertz-Picciotto and Delwiche, 2009; Bertoglio and Hendren, 2009; Matson and Kozlowski, 2011; Atladottir et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2013). Additionally, this rising incidence can only partially be explained by changes in diagnostic criteria. This has increased consideration of a potential involvement of environmental factors, including environmental chemical exposures, in the etiology of ASD (Fombonne, 2009).

A compelling case for the involvement of early life air pollution (AP) exposures and ASD is suggested by a growing number of epidemiological studies (Volk et al., 2013, 2014, 2011; Becerra et al., 2013; Jung et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013a; Windham et al., 2006; Kalkbrenner et al., 2010). AP has also been linked to impaired cognitive abilities (Wang et al., 2009; van Kempen et al., 2012), and attention-related deficits (Siddique et al., 2011) as well as to schizophrenia (Duan et al., 2018; Eguchi et al., 2018; Yackerson et al., 2013; Pedersen et al., 2004), notably all neurobehavioral disorders with male-biased prevalence rates. These disorders also frequently include abberant social behaviors. Diagnosis of ASD is premised on altered behaviors, including alterations in social interactions and communication (Bhat et al., 2014). Deficits in social cognition are also pervasive in schizophrenia (Mier and Kirsch, 2017), while aterations in social skills also characterize attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (Kulkarni, 2015).

These epidemiological asssociations between AP and characteristics of male-biased neurodevelopmental disorders are also seen in our studies of developmental exposures of mice to UFPs in the early postnatal period, a time considered equivalent to human 3rd trimester brain development (Clancy et al., 2007a,b; Rice and Barone, 2000) that produce characteristics reminiscent of ASD preferentially and persistently in males (e.g., altered dopamine/glutamate function, excitatory/inhibitory imbalance, glial activation/cytokine release, reductions in white matter and size of the corpus callosum, ventriculomegaly). This male bias is consistent with the male prevalence in autism spectrum disorder (Baio et al., 2018), findings also observed in other neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and in many studies, schizophrenia (Kern et al., 2017; Abel et al., 2010).

Such male-sensitivity raises questions regarding the extent to which endocrine active chemical (EAC) contaminants of AP may play a key role. AP is a complex mixture that includes particles, gases (CO2, CO, NO, ozone, SO2) and adsorbed volatile organic and inorganic contaminants, such as metals and trace elements (Friedlander, 1973) with specific contaminants differing by geography, climate, season, weather conditions, etc. Consideration of the health consequences of AP exposures are typically related to the size of the particulate matter (PM) that are designated as coarse (< 10 μm or PM10), fine (< 2.5 μm or PM2.5), or ultrafine particles (UFP; < 100 nm or 0.1 μm). UFPs are of particular concern as the most reactive component (Oberdorster et al., 1994; Brown et al., 2001), likely due to their greater surface area/mass ratio for contamination by organic and inorganic adherents (Lin et al., 2005). EACs such as polychlorinated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, metals, phthalates, and certain pesticides are reported in indoor and outdoor environments that can target early organizational hormone patterns critical for brain development (de Cock et al., 2012; Tareen and Kamboj, 2012; Rudel and Perovich, 2009). Further, many metal and trace element contaminants of AP also have endocrine-related effects (Rana, 2014).

The male biased neurotoxicity of early postnatal exposures to UFPs in our studies (Allen et al., 2013, 2017, 2014a,b,c) also raises the issue of whethe AP alters steroid hormones. Inappropriate levels of perinatal testosterone (T) have been posited to play an etiological role in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in ASD (James, 2008; King et al., 2000, 1999). In rodents, T excretion from leydig cells begins around gestational day (GD) 15, increases on GD17 and GD19, and surges within hours of birth and continues into the early postnatal period (Scott et al., 2009). T is critically important for sexual differentiation of the brain (Auyeung et al., 2013; Fitch et al., 1991; Chura et al., 2010; Moffat et al., 1997; Lenz and McCarthy, 2014; Lenz et al., 2013). ASD incidence has been linked to androgen-sensitive reproductive malformations (Rzhetsky et al., 2014; Butwicka et al., 2015) and children of women with hyper-androgenic PCOS have higher ASD assessment scores (Ingudomnukul et al., 2007; Palomba et al., 2012). Increases in prenatal T correlate with poor eye contact, social relationship quality, and higher ASD assessment scores, however, adult T levels show inconsistent, even negative correlations with ASD in humans (Schaafsma and Pfaff, 2014; Croonenberghs et al., 2010). Increasingly, evidence suggests that developmental air pollution exposures can alter sex hormone function and adult social behaviors in rodent models. For example, increased T biosynthesis was found in adult rodents exposed to diesel exhaust that was likely due to increased expression of testicular cholesterol synthesizing enzymes (Li et al., 2012). Inhalation of diesel exhaust particles during gestation increased T in pregnant rat dams for up to 3 weeks after birth, suggestive of an alteration in aromatase activity (Watanabe and Kurita, 2001), causing fetal masculinization and increasing anogenital distance in both male and female offspring, a measure of prenatal androgen exposure (vom Saal et al., 1990). Furthermore, studies have reported that diesel exhaust increases testes weight, spermatogenesis, and serum T levels (Yoshida et al., 2006; Ono et al., 2008).

Collectively, the above raises questions as to whether early postnatal UFP exposures recapitulate the social behavioral deficits seen in these neurodevelopmental disorders in addition to the many neuropathological, neurochemical and behavioral features already observed. In addition, many such neurodevelopmental disorders are male-biased. To address this hypothesis, we expanded our behavioral assessment in this study to include a battery of social behaviors, specifically social preference, recognition and communication. In addition, levels of serum T and another steroid hormone, corticosterone, were measured at PND14 (i.e., immediately following developmental UFP exposures), as well as in adulthood, to determine whether potential steroid hormone mechanisms might be impacted and/or contribute to any observed alterations in social behaviors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and husbandry

Eight week old male and female C57BL/6 J mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were bred using a monogamous pairing scheme. Male and female (n = 35 pairs) mice were paired for 3 days, after which males were removed from the home cage. Pregnant dams (n = 24) remained singly housed throughout weaning. On average, litters contained (mean ± SD) 5.91 ± 1.56 pups with (mean ± SD) approximately 45 ± 22% males. Litter sizes ranged from 4 to 8 pups. To decrease inter-litter variability, treatment groups were counterbalanced against litter size and each litter had an allocation of both UFP and filtered air exposed pups. To preclude litter specific effects, pups were randomly allocated to each of the 4 treatment groups (male-Air, male-UFP, female-Air, female-UFP) when possible. Upon weaning at PND25, male and female progeny were housed in same sex pairs in a vivarium room maintained at 22 ± 2 °C with a 12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h). Labdiet Rodent 5001 diet was provided ad libitum. All experiments were carried out according to NIH Guidelines and were approved by the University of Rochester Medical School University Committee on Animal Resources.

2.2. Air pollution exposure

Offspring (n = 8–12/treatment group/sex) were exposed to UFPs or HEPA-filtered (99.99% effective) room air in compartmentalized whole body inhalation chambers over PNDs 4–7 and 10–13 for 4 h/day between 0700–1300 hours corresponding to high levels of vehicular traffic near the ambient air intake valve. This time period is equivalent to human third trimester in terms of brain development (Clancy et al., 2007a; Rice and Barone, 2000; Clancy et al., 2007c) and was chosen as it encompasses a period of marked neuro- and gliogenesis (Bandeira et al., 2009). Pups were removed from dams to prevent mothering behavior (e.g. nose-to-fur huddling) from impacting exposures for both filtered air and UFP-exposed offspring, and thus maternal separation or milk deprivation effects were comparable across treatment. No gross differences in maternal care by treatment were observed after cessation of exposure. Exposures were carried out using the Harvard University Concentrated Ambient Particle System (HUCAPS) as described previously in detail (Allen et al., 2013). Briefly, the HUCAPS system concentrates ambient ultrafine particles from a nearby highly trafficked roadway to approximately 10 times that of ambient air and delivers them to compartmentalized whole-body inhalation chambers. The natural variability in ambient air in these exposures represents the real-world nature of the air pollution exposure. Particle counts were obtained using a condensation particle counter (model 3022 A; TSI, Shoreview, MN) and mass concentration was calculated using idealized particle density of 1.5 g/cm3. Both UFP and Air mouse exposure chambers were maintained at 77–79 °F and 35–40% relative humidity.

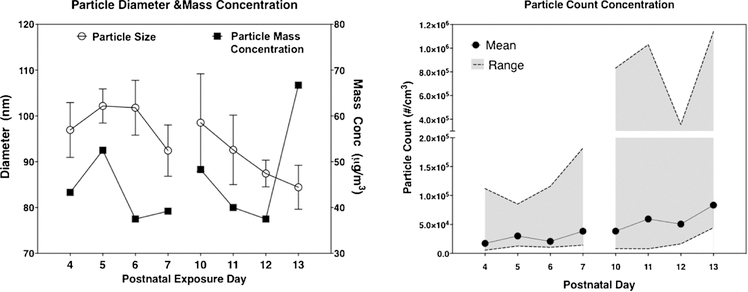

2.3. Quantification of exposure

As shown in Fig. 1, ambient outdoor UFP counts ranged from approximately 10,000–27,000 particles/ cm3 and were concentrated giving rise to UFP exposure particle count concentrations averaging approximately 50,000 particles/cm3. Particle mass concentrations ranged from 40 to 60 μg/m3, averaging approximately 45 μg/m3 across days. Concentrated particle counts showed a wide range, consistent with intra- and inter-day real-world variability, and averaged between 17,215 to 83,378 particles/cm3. In addition, particle size distribution confirmed that particles were, as expected, below 100 nm, as in our prior studies (Allen et al., 2013, 2014d).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of ambient ultrafine particle exposures. Right: Particle size (nm) and mass concentration (μg/m3) are shown from each exposure day. Left: Particle count number mean values and ranges are shown for each exposure day.

2.4. Behavioral methods

All behavioral assays were video recorded and scored by an observer blinded to the treatment groups using Observer XT 13.0 (Noldus).

2.4.1. Social conditioned place preference (SCPP)

SCPP testing occurred in a three-chambered polycarbonate box (63 cm × 27 cm × 31 cm) using two groups of animals (denoted as squad 1 and squad 2). One chamber was wall papered with vertical and a second chamber was wall papered with horizontal black and white stripes. In a manner counter-balanced across individuals, both for side and paper orientation, one chamber was designated as the social chamber, while the other was designated as the solitary chamber. Testing consisted of two phases, training and preference testing. Training occurred for 10 min a day for 10 days. During this training period, mice could choose between the side chamber that contained its cagemate (placed under a wire cup) or the side chamber that contained only an empty wire cup. For the preference test, both side chambers were empty, and mice were returned to the center arena, and their subsequent preference behavior videotaped and scored for the next 5 min. Data collected include: individual’s first choice, latency to make first choice, total duration in each chamber and number of entries into each chamber. A Social Preference Index was calculated using the following equation:

2.4.2. Social novelty preference (SNP)

SNP was conducted in two phases, in a three-chambered polycarbonate box (63 cm × 27 cm × 31 cm) and used a separate squad of mice. Mice were first habituated to the chambers by being placed in the center chamber and given 10 min to explore the apparatus with empty, identical, wire cups in each adjacent chamber. The habituation period was followed by two testing phases: sociability and social novelty. In the sociability phase, mice were placed in the center chamber of the three-chambered polycarbonate box with a novel object (rubber duck) place under one wire cup in one dise chamber and a novel C57Bl/6 age and sex-matched mouse placed under the second cup in the opposite side chamber. In the social novelty phase, mice were returned to the chamber with a new novel sex-matched mouse and a familiar one under the wire cups. All phases were 10 min long and video recorded. Scoring codes included time spent in each chamber, time spent exploring each cup, and nose-to-nose sniffing. Time spent with cup was defined as: mouse facing cup, nose touching or sniffing the cup within a 2 cm boundary. Mice engaged in a particular greeting behavior, nose-to-nose sniffing. Nose-to-nose sniffing was defined as both mice point towards each other, noses touching, sniffing (see supplemental video 1). A social recognition index and nose-to-nose sniff rate was calculated for the second and third phases as follows:

The placement of mice (novel/familiar) and novel object were counterbalanced across individuals. Naïve animals were used in all testing phases.

2.4.3. Elevated plus maze (EPM)

Mice were placed in the center of the maze, and each session was 5 min in duration. Scoring codes included entries into and time spent in the open arms, center and closed arms of the maze.

2.5. Serum testosterone and corticosterone determinations

Blood was collected immediately after exposure on PND14 and also after the conclusion of social behavior testing (at approximately 12 months of age). Mice were weighed and then sacrificed by cervical dislocation without the use of sedatives and fresh brains removed and hemisected. Upon sacrifice, trunk blood was collected. Whole blood was collected into pre-chilled centrifuge tubes and centrifuged for 20 min at 3500 g for 20 min to obtain serum. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C until day of assay. Serum T and corticosterone were measured in duplicate using commercially available Enzyme immunoassay kits (testosterone: ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA; corticosterone: Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), according to manufacturer’s specifications. Sample replicates with CV’s higher than 15% were excluded from analysis (two adult male samples were excluded).

2.6. Statistical analyses

As our prior studies demonstrated robust sex-specific effects of AP (Allen et al., 2017, 2014a,c), statistical analyses were conducted separately by sex if a significant main effect of sex or interaction of sex by treatment was confirmed in statistical analyses. If so, one-way ANOVAs for treatment group (UFP and AIR) were used to analyze testosterone, corticosterone, and social novelty preference assays. Two-factor ANOVAs were used to analyze elevated plus maze and social conditioned place preference assays with treatment (UFP and AIR) and sex (male and female) as between group factors, with subsequent post-hoc tests (student’s t-test) as appropriate dependent upon interaction outcomes. Outliers were removed following a statistically significant Grubb’s test (Graphpad Software Inc.). Statistical analyses were conducted using JMP Pro 13.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, while near significant values (p values ≤ 0.06) are also indicated.

3. Results

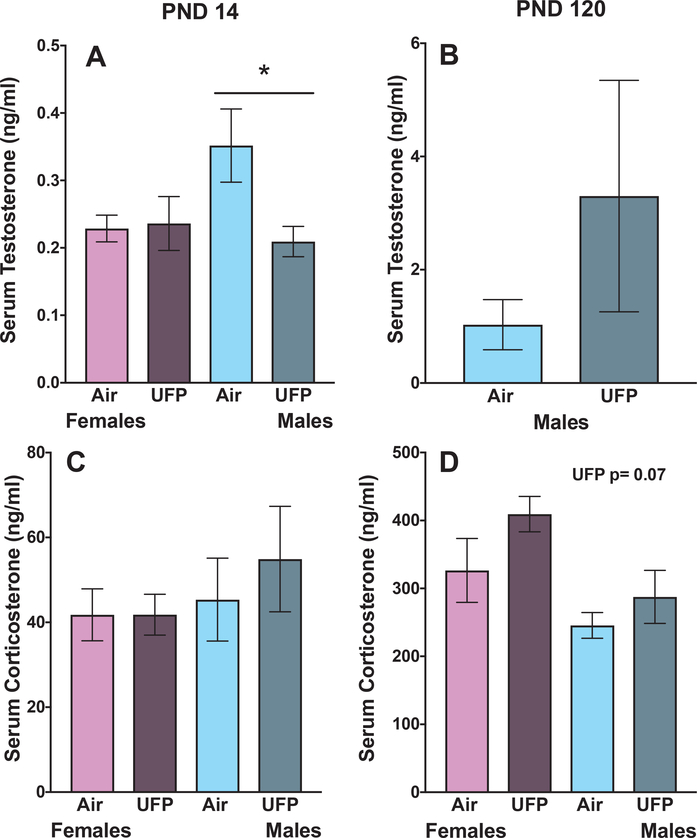

3.1. Serum testosterone and corticosterone concentrations and body weight

Control males had significantly higher T levels than control females at PND 14 (Fig. 2A: F (1, 19) = 4.8, p < 0.04). UFP-exposed males did not have higher T levels than UFP-exposed females (Fig. 2A: F (1, 19) = 0.32, p = 0.58). UFP exposed male mice, at PND 14, showed significantly decreased T levels compared to control males (Fig. 2A: F (1, 19) = 5.87, p = 0.026). There were no treatment-related differences in females (Fig. 2A: F (1, 20) = 0.02, p = 0.87). At PND 120, the trend towards higher T levels in UFP-exposed males remained, but was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B: F (1, 20) = 1.18, p = 0.29) even with removal of two samples in the UFP-exposed males with high serum T concentrations (F (1, 18) = 2.4, p = 0.14).

Fig. 2. Group mean ± S.E. Serum Testosterone and Corticosterone Concentrations.

of female (purple) and male (blues) mice exposed to either filtered air or UFPs. Adult serum testosterone concentrations were measured at PND14 (A; n = 10–11/group) and in adulthood (B) (n = 10/group). UFP- exposed males showed decreased T levels immediately following exposure, but reductions were not found in adulthood. At PND14, there was no change in testosterone concentrations in either sex (n = 9–10/group).; however there was a slight trend towards a UFP-induced increase in corticosterone concentrations in females in adulthood (C and D) (n = 6–12/group).

Corticosterone concentrations were not changed by UFPs at PND 14 or in adulthood (Fig. 2C and D, respectively: males: F (1, 18) = 1.2, p = 0.30, F (1, 19) = 1.2, p = 0.30; females: F (1, 18) = 0.0, p = 0.99, F (1, 13) = 1.9, p = 0.19, PND 14 and PND 120 respectively). There were no significant differences in body weight immediately following exposure (data not shown: males: F (1, 23) = 0.01, p = 0.95; females: F (1, 23) = 0.32, p = 0.57).

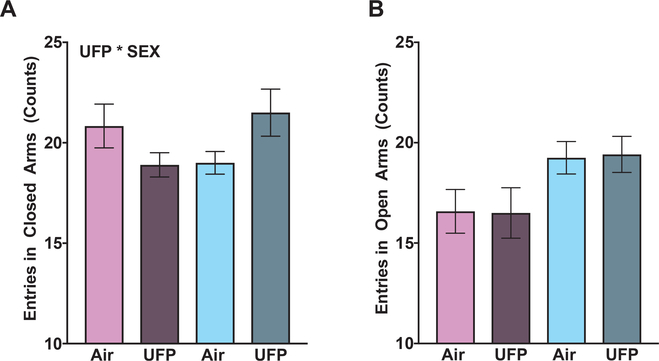

3.2. Elevated plus maze

There was a significant interaction between sex and treatment for number of entries into the closed arms of the EPM (Fig. 3A: F (3, 42) = 5.7, p < 0.02) that was due to the greater number of entries into open arms by males (Fig. 3B, F (3, 42) = 7.59, p < 0.01). Therefore, separating by sex, UFP-exposed males had an increased number of entries into the closed arms, though it failed to reach significance (Fig. 3A: F (1, 22) = 3.7, p = 0.06). However, for entries into the open arms, there were no significant treatment-related differences for males or females (Fig. 3B: males: F (1, 22) = 0.02, p = 0.89; females: F (1, 20) < 0.01, p = 0.96). There was no significant UFP effects on duration in the open or closed arms (closed arms: female: F (1, 20) = 0.24, p = 0.62, male: F (1, 22) = 0.01, p = 0.91; open arms: female: F (1, 20) = 0.39, p = 0.54, male: F < 0.01, p = 0.95; data not shown).

Fig. 3. Elevated Plus Maze.

Group mean ± S.E entries into closed arms (A) and into open arms (B) of male (purple colors) and female (blue colors) mice exposed to filtered air or UFP. There was a significant interaction between UFP exposure and sex on number of entries into the closed arms; however post hoc analyses separated by sex did not show significance between UFP and control animals (A). UFP exposure did not change number of entries into the open arms for the EPM (B). Asterisk indicates p ≤ 0.05; hashtag indicates p ≤ 0.6; n = 10–12/group.

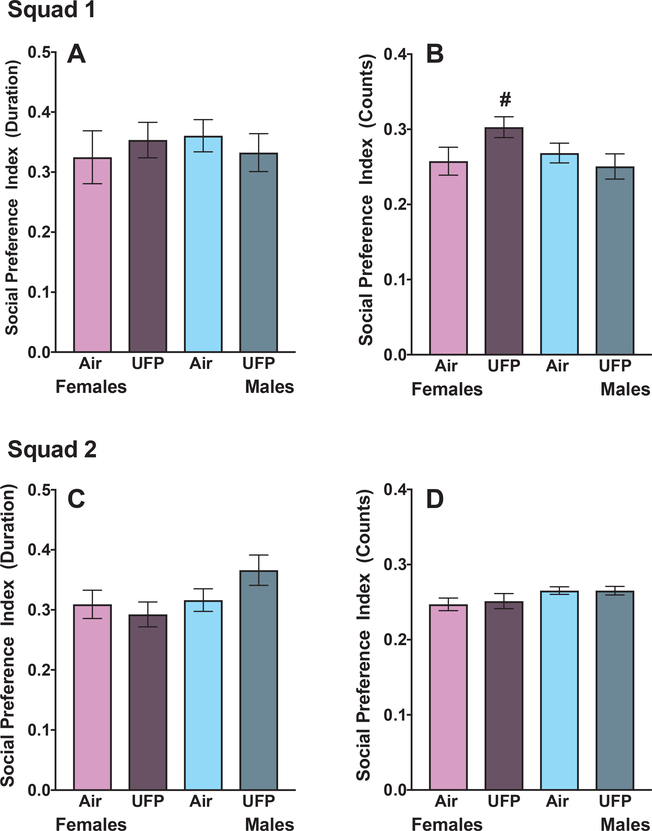

3.3. Social conditioned place preference

There were no significant reductions in social preference conditioning following UFP exposure, as measured by duration of time spent (Figs. 4A and C: Squad 1: F (1, 21) = 0.44, p = 0.51; Squad 2: F (1, 23) = 2.5, p = 0.12) or in the number of entries into the social chamber (Figs. 4B and D; Squad 1: F (1, 21) = 0.65, p = 0.42; Squad 2: F (1, 23) = 0.01, p = 0.98). While UFP-treated females in squad 2 showed no significant changes in social preference index counts in the social chamber (Fig. 4D), there were increased entries into the social chamber for Squad 1 (Fig. 4B), though it failed to reach significance (Squad 1: F (1, 23) = 3.8, p = 0.06; Squad 2: F (1, 20) = 0.10, p = 0.75). No treatment related differences in social index duration were seen in females (Fig. 4A and C: duration: Squad 1: F (1, 23) = 0.29, p = 0.59; Squad 2: F (1, 20) = 0.28, p = 0.60).

Fig. 4. Social Conditioned Place Preference.

Group mean ± S.E social preference index duration (A and C) and counts (B and D) of female (purple) and male (blue) mice exposed to filtered air or UFP from Squad 1 (top row) and Squad 2 (bottom row). There were no overt deficits in social conditioned place preference in male or female mice. In fact, there was a slight increase in Social Preference Index counts of UFP-exposed females in Squad 1(B). (N = 10–12). Asterisk indicates p ≤ 0.05; hashtag indicates p ≤ 0.1; n = 10–12/group.

3.4. Three-chambered social novelty preference

Social novelty testing occurred in two testing phases: sociability testing and novelty testing. In the sociability phase, mice were placed in the center chamber of the three-chambered polycarbonate box with a novel object (rubber duck) place under one wire cup in one side chamber and a novel C57Bl/6 age and sex-matched mouse placed under the wire cup in the opposite side chamber. In the social novelty phase, mice were returned to the chamber with a new novel sex-matched mouse and a familiar one under the wire cups.

In the sociability testing phase, UFP exposed females trended towards spending more time investigating the novel mouse cup, but it failed to reach statistical significance (F (1, 19) = 4.0, p = 0.06) and social sniffing was not altered during the sociability phase (F (1, 19) = 2.2, p = 0.15). During the social novelty phase, social nose-to-nose sniffing was not altered by UFPs in female mice, either in the presence of a novel or a familiar mouse (Fig. 5A and B, respectively: novelty testing: novel mouse: F (1, 19) = 0.38, p = 0.54; familiar mouse: F (1, 19) = 0.95, p = 0.34), and the recognition index during the social novelty phase was not affected (duration: F (1, 19) = 1.38, p = 0.25).

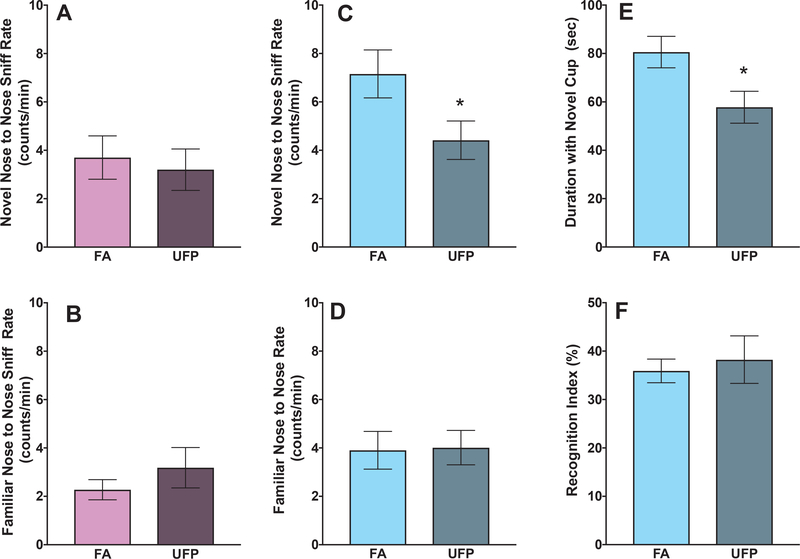

Fig. 5. Social Novelty Preference Novelty Testing Phase.

Analysis of phase two representing the first exposure to a novel same-sex conspecific. Group mean ± S.E. counts/minute of nose to nose sniffing of a novel mouse (A) and to a familiar mouse (B) of female mice exposed to filtered air or UFP. Group mean ± S.E. counts/minute of nose to nose sniffing of a novel mouse (C) and duration of time in seconds spent with the novel wire cup under which the novel mouse was placed (E) of male mice ex[psed to filtered air or UFPs in contrast to nose to nose sniff rates in the presence of a familiar mouse (D) and the social recognition index in the presence of a familiar mouse (F). Male mice showed significantly more nose-to-nose sniff counts compared to female mice (cf. A vs. C and B vs. D). Male mice exposed to UFPs showed significantly fewer nose-to-nose sniff counts compared to air males to the presence of a novel mouse (C) as well as a corresponding reduction in duration of time spent with the wire cup housing the novel mouse (E). Corresponding effects on nose-to-nose sniff counts were not observed in interactions with their cage mate (D). This was not attributable to a reduction in the recognition of a familiar conspecific (F). Also in phase three, there was still a marginally significant decrease in nose-to-nose sniff counts for males exposed to UFPs, when exposed to another novel mouse, while in the context of exposure to the cage mate. (N = 10–12). Asterisk indicates p ≤ 0.05; hashtag indicates p ≤ 0.1; n = 10–12/group.

During the sociability phase, UFP-exposed males spent less time exploring the novel mouse (F (1, 22) = 6.0, p = 0.02) and had a decreased nose-to-nose sniff rate with the novel mouse (F (1, 22) = 5.1, p = 0.03). In the social novelty phase, UFP-exposed males again showed reductions in nose-to-nose sniff rate with a novel mouse (Fig. 5C: F (1, 22) = 4.7, p = 0.04), as well as a reduction in duration of time spent with the cup housing the novel mouse (Fig. 5E), while there were no significant differences in nose-to-nose contact with the familiar mouse (Fig. 5D: F (1, 22) = 0.01, p = 0.92). All males were able to recognize the novel males, as there were no significant difference in the recognition index for UFP-exposed males compared to controls (Fig. 5F: duration: F (1, 22) = 0.47, p = 0.5; counts: F (1, 22) = 0.12, p = 0.73).

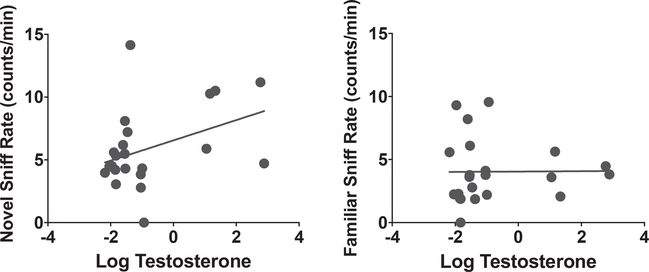

To determine whether T levels may play a role in social novelty preference, correlations between adult serum T levels and nose-to-nose sniff rates were carried out. These analyses suggest that serum T is associated with male nose-to-nose sniff rates when males are investigating a novel male (Fig. 6: r2 = 0.2, p = 0.06), but not with a familiar mouse (r2 = 0.0, p = 0.96).

Fig. 6. Correlations between Adult Serum Testosterone and Nose-to-Nose Sniff Rate.

The association between nose-to-nose sniff rates with a novel animal and adult testosterone (r2 = 0.2, p = 0.06) as determined by linear regression, where no such correlation exists with familiar animal nose-to-nose sniff rates (r2 = 0, p = 0.96), suggests an association between this behavior and serum testosterone.

4. Discussion

Epidemiological evidence suggests that poor air quality may contribute to the etiology of sex-biased neurodevelopmental disorders and cognitive deficits in children, including ASD, attention-like deficits, schizophrenia and others, many of which are male-biased in prevalence (Volk et al., 2013, 2014, 2011; Jung et al., 2013; Windham et al., 2006; Kalkbrenner et al., 2010; Duan et al., 2018; Eguchi et al., 2018; Pedersen et al., 2004; Becerra et al., 2013; Roberts et al., 2013b; Siddique et al., 2011). Our prior findings in experimental studies of early postnatal UFP exposure, consistent with human brain 3rd trimester (Clancy et al., 2007b; Romijn et al., 1991), provide biological support to such associations, showing male-specific and/or male-biased neuropathological and neurochemical changes as well as some impulsive-like and cognitive deficits associated with such disorders (Allen et al., 2013, 2014b,c, 2015). Given the fact that these disorders are also characterized, and in some cases diagnosed by, deficits in social behaviors and communication (Bhat et al., 2014; Mier and Kirsch, 2017; Kulkarni, 2015), the current study hypothesized that these features of such disorders might also be reproduced by UFPs and could potentially be related to changes in sex steroids.

Consistent with this hypothesis, the current study found male-specific alterations in social novelty preference consisting of reduced duration of time spent in the chamber and reduced nose to nose sniffing behavior with a novel mouse rather than a rubber duck or a novel conspecific. These effects could not be attributed to a generalized social aversion, since no such changes were seen in response to a familiar conspecific mouse. Additionally, levels of T in males were reduced during the early postnatal period, suggesting that an altered steroid hormone milieu might contribute to such effects, particularly as testosterone levels in adulthood were shown to correlate positively with levels of nose to nose sniffing behavior.

These findings are consistent with a prior report demonstrating that developmental exposures of mice to fine/ UFP components of air pollution (135.8 ug/m3) during gestation and early postnatal development disrupted social behavior in adulthood (Church et al., 2017). Specifically, exposures from gestational day 0.5 to 17 for 6 h/day for 7 days a week followed by postnatal exposures beginning at postnatal day 2 for 2 h/day 7 days a week until postnatal day 10, resulted as measured at 20 weeks of age, in reduced social approach behavior in both sexes, while producing a male-specific reduction in reciprocal social interactions. In the current study, postnatal UFP exposure alone induced a consistent alteration in social behavior, suggesting the potential importance of the postnatal period (human brain 3rd trimester equivalent) to the alterations in social behavior. Moreover, exposure concentrations in the current study averaged approximately 45 ug/m3, i.e., approximately 2/3 lower than those in the Church et al. study (Church et al., 2017), indicating that air pollution-associated alterations in social behavior can occur at even relatively low levels of exposure during development.

Adult social behavior is a complex phenotype comprising a variety of neurobehavioral patterns: overall gregariousness (desire to be in a social group), tendency to approach, and communication skill that are context-dependent and often are learned over time. To understand what underlying components of social behavior were disrupted by postnatal UFP exposure, we utilized a battery of social assays, including social place conditioning, social approach communication, and social recognition (Silverman et al., 2010; Crawley, 2007). Postnatal UFP exposure decreased nose-to-nose sniff contact between novel adult males. Interestingly, this specific social deficit occurred without overt toxicity to overall social preference or recognition ability. The lack of significant decreases in the social recognition index suggests there were no deficits in social recognition between the novel and familiar mouse. Additionally, alterations in nose-to-nose communication does not seem to be mediated by large changes in fear-mediated behaviors, such as increased time in the open arms of an elevated plus maze, as males showed no differences in total entries into or time in the open arms of the EPM. Again, females showed no changes.

Our findings highlights the susceptibility of the postnatal period as critical for adult social behavior development. This critical developmental period represents a period of rapid brain development and growth with patterns that are often sex-specific in nature in mice. The mechanisms of sex-specific brain development are often regulated by waves of steroid hormone exposure which occurring during very specific windows of development, which overlap with our exposure window (McCarthy et al., 2018, 2017). In this study, exposure to UFPs for eight days between postnatal days 4–13 resulted in a decrease in serum T on day 14. The decrease in T at PND14 does not represent a generalized decrease in serum steroid concentrations, as corticosterone concentrations were not altered. Increases in T in male offspring at PND120 were suggestive, but not statistically significant, indicating a need for replication that includes repeated measures across time. However, collectively, the data suggest a change in the trajectory of T over the lifetime, which normally increases and subsequently is shown to remain constant in mice (but not rats) (Eleftheriou and Lucas, 1974; Finch et al., 1977). Females showed no early treatment-related differences in serum T concentrations.

Specific components of diesel exhaust particles, 3-methyl-4-nitrophenol, 4-nitrophenol, etc., have been shown to have both androgenic and anti-androgenic activity. Interestingly, carbon nanoparticle exposure alone did not alter serum T (Yoshida et al., 2010). Differences in T may be due either to the composition, concentration, duration, or developmental exposure window or to the contaminants that adhere to particulate matter. Additionally, many exposure procedures are stressful with prolonged activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; cross-talk between the HPA and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis can be critical to understand disruption of serum sex-steroid concentrations (Acevedo‐Rodriguez et al., 2018; Viau, 2002). Variation in the consistency of exposure protocols may influence the endocrine action of developmental AP exposure. Although testis weight at PND 14 did not significantly change in response to UFP exposures, future studies should investigate sperm production and motility. Previous studies in rodents have shown alterations in sperm quality following diesel exhaust exposures, without an overt decrease in testis weight (Li et al., 2012; Watanabe and Kurita, 2001; Watanabe and Oonuki, 1999).

It is important to consider that decreased T concentrations at P14 likely does not define the full extent of the early disruption of neuro-development that was induced by postnatal UFP exposure. Increasingly, research on sex-specific brain development has identified a complex program of sex-specific brain development, which includes inflammation, epigenetics and hormones as mediators of development (Lenz et al., 2013; McCarthy et al., 2017). Changes in serum T can be viewed instead as an indicator that typical early sex-specific brain development programming has been altered. In fact, the role of microglia specifically has been increasingly recognized to play a key role in sex-specific neurodevelopment, and in our prior studies, postnatal UFP exposures resulted in cytokine elevations and brain microglia activation that were posited to play a role in the accompanying sex-specific neuropathology, including white matter development, previously documented into adult UFP exposed males (Allen et al., 2014c,d). Interactions between endocrine disruption and inflammatory response to UFP merits further investigation as together they play a key role in sex-specific neurodevelopment (Lenz and McCarthy, 2014; Lenz et al., 2013; McCarthy et al., 2009). Interestingly, it has been reported that testosterone depletion, as seen here early in life, can produce astrocyte and microglial inflammation as well as enhanced permeability of the blood-brain barrier (Atallah et al., 2016); in prior studies we have observed male specific microglial activation in corpus callosum (Allen et al., 2014c).

Of critical note is that the UFP exposure concentration in the current study is approximately 1/4th the exposure of our previous studies (Allen et al., 2014d). Reports of UFP particle concentrations in Erfurt, Germany (Wichmann and Peters, 2010) and Atlanta GA (Woo et al., 2010) ranged from 10,000–20,000 particles/cm3, similar to ambient UFP concentrations reported here. However, particle concentrations in Los Angeles, California, USA and Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA have been reported at 200,000–400,000/cm3, respectively, near highways, with peak episodic counts reaching as high as 2,000,000 particles/cm3 in Minneapolis (Kittelson, 2004; Westerdahl et al., 2005). Thus, particle exposures in this study were low to moderate in environmental relevance and clearly within human-relevant ranges. In fact, our previous studies, with exposures averaging 200,000 particles/cm3, were 3–4× higher than the concentrations in the current study (Allen et al., 2013). A limitation of the present study includes determination of whether alterations in sniffing behavior in male mice may be influenced by alterations in olfactory development following UFP exposure. Future research is needed to identify differences in olfactory behavior.

Multiple routes of exposure of UFP to brain are possible during this period. As noted previously, AP is a complex mixture that includes particles, gases (CO2, CO, NO, ozone, SO2) and adsorbed volatile organic and inorganic contaminants, such as metals and trace elements (Friedlander, 1973). Gaseous components as well as trace element contaminants may reach brain via the nasal olfactory pathways, even bypassing the blood brain barrier (Brain, 1970; Tjalve and Henriksson, 1999). In addition, gases or particles deposited on the lining of the respiratory tract can move into the bloodstream and be transported to other body tissues (Bigazzi and Figliozzi, 2014). The current understanding of which components of UFPs lead to the observed deficits remains unclear but is critical to understand for purposes of public health protection.

In conclusion, UFP exposure decreased serum T concentrations on PND 14 and social nose-to-nose sniff rates with novel males in adulthood, suggesting social communication deficits in unfamiliar social contexts. These decreased sniff rates were not accounted for by alterations in fear-mediated behaviors and occurred without overt deficits in social preference, recognition or communication with a familiar animal. Future studies are needed to understand the inter-connected role of the endocrine and immune systems, including microglia, in regulating sex-specific neurobehavioral development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIHR01 ES025541 (Cory-Slechta, D.A.) and P30 ES00247 (D. Cory-Slechta, PI). Dr. Joshua Allen is currently a Principal Research Scientist at Battelle Research, Columbus Ohio. Dr. Carolyn Klocke is a postdoctoral fellow at University of California, Davis.

References

- Abel KM, Drake R, Goldstein JM, 2010. Sex differences in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 22 (5), 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo‐Rodriguez A, et al. , 2018. Emerging insights into Hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal (HPG) axis regulation and interaction with stress signaling. J. Neuroendocrinol, e12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2013. Developmental exposure to concentrated ambient particles and preference for immediate reward in mice. Environ. Health Perspect 121 (1), 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2014a. Early postnatal exposure to ultrafine particulate matter air pollution: persistent ventriculomegaly, neurochemical disruption, and glial activation preferentially in male mice. Environ. Health Perspect 122 (9), 939–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2014b. Consequences of developmental exposure to concentrated ambient ultrafine particle air pollution combined with the adult paraquat and maneb model of the Parkinson’s disease phenotype in male mice. Neurotoxicology 41, 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2014c. Developmental exposure to concentrated ambient ultrafine particulate matter air pollution in mice results in persistent and sex-dependent behavioral neurotoxicity and glial activation. Toxicol. Sci 140 (1), 160–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2014d. Early postnatal exposure to ultrafine particulate matter air pollution: persistent ventriculomegaly, neurochemical disruption, and glial activation preferentially in male mice. Environ. Health Perspect [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2015. Developmental neurotoxicity of inhaled ambient ultrafine particle air pollution: parallels with neuropathological and behavioral features of autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurotoxicology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, et al. , 2017. Cognitive effects of air pollution exposures and potential mechanistic underpinnings. Curr. Environ. Health Rep 4 (2), 180–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah A, Mhaouty-Kodja S, Grange-Messent V, 2016. Chronic depletion of gonadal testosterone leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction and inflammation in male mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 37 (9), 3161–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atladottir HO, et al. , 2014. The increasing prevalence of reported diagnoses of childhood psychiatric disorders: a descriptive multinational comparison. Eur Child Adolesc. Psychiatry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auyeung B, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S, 2013. Prenatal and postnatal hormone effects on the human brain and cognition. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol 465 (5), 557–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, et al. , 2018. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 67 (6), 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeira F, Lent R, Herculano-Houzel S, 2009. Changing numbers of neuronal and non-neuronal cells underlie postnatal brain growth in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106 (33), 14108–14113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra TA, et al. , 2013. Ambient air pollution and autism in Los Angeles county, California. Environ. Health Perspect 121 (3), 380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoglio K, Hendren RL, 2009. New developments in autism. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am 32 (1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S, et al. , 2014. Autism: cause factors, early diagnosis and therapies. Rev. Neurosci 25 (6), 841–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi AY, Figliozzi MA, 2014. Review of urban bicyclists’ intake and uptake of traffic-related air pollution. Transp. Rev 34 (2), 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- Brain JD, 1970. The Uptake of Inhaled Gases by the Nose. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol 79 (3), 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DM, et al. , 2001. Size-dependent proinflammatory effects of ultrafine polystyrene particles: a role for surface area and oxidative stress in the enhanced activity of ultrafines. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 175 (3), 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butwicka A, et al. , 2015. Hypospadias and increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56 (2), 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chura LR, et al. , 2010. Organizational effects of fetal testosterone on human corpus callosum size and asymmetry. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35 (1), 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church JS, et al. , 2017. Perinatal exposure to concentrated ambient particulates results in autism-like behavioral deficits in adult mice. NeuroToxicology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, et al. , 2007a. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. Neurotoxicology 28 (5), 931–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, et al. , 2007b. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. NeuroToxicology 28 (5), 931–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, et al. , 2007c. Web-based method for translating neurodevelopment from laboratory species to humans. Neuroinformatics 5 (1), 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, 2007. Mouse behavioral assays relevant to the symptoms of autism. Brain Pathol. 17 (4), 448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croonenberghs J, et al. , 2010. Serum testosterone concentration in male autistic youngsters. Neuroendocrinol. Lett 31 (4), 483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock M, Maas YG, van de Bor M, 2012. Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Review. Acta Paediatr 101 (8), 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, et al. , 2018. Is the serious ambient air pollution associated with increased admissions for schizophrenia? Sci. Total Environ 644, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi R, et al. , 2018. The relationship between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and schizophrenia severity. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 91 (5), 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleftheriou BE, Lucas LA, 1974. Age-related changes in testes, seminal vesicles and plasma testosterone levels in male mice. Gerontology 20 (4), 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE, et al. , 1977. Hormone Production by the Pituitary and Testes of Male C57BL/ 6J Mice During Aging. Endocrinology 101 (4), 1310–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RH, et al. , 1991. Corpus callosum: demasculinization via perinatal anti-androgen. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci 9 (1), 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, 2009. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr. Res 65, 591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander SK, 1973. Chemical element balances and identification of air pollution sources. Environ. Sci. Technol 7 (3), 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto I, Delwiche L, 2009. The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology 20 (1), 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguet G, Ey E, Bourgeron T, 2013. The genetic landscapes of autism spectrum disorders. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 14, 191–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingudomnukul E, et al. , 2007. Elevated rates of testosterone-related disorders in women with autism spectrum conditions. Horm. Behav 51 (5), 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James WH, 2008. Further evidence that some male‐based neurodevelopmental disorders are associated with high intrauterine testosterone concentrations. Dev. Med. Child Neurol 50 (1), 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CR, Lin YT, Hwang BF, 2013. Air pollution and newly diagnostic autism spectrum disorders: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One 8 (9), e75510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner AE, et al. , 2010. Perinatal exposure to hazardous air pollutants and autism spectrum disorders at age 8. Epidemiology 21 (5), 631–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JK, et al. , 2017. Developmental neurotoxicants and the vulnerable male brain: a systematic review of suspected neurotoxicants that disproportionally affect males. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars) 77 (4), 269–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JA, Kelly T, Delville Y, 1999. Adult levels of testosterone alter catecholamine innervation in an animal model of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychobiology 42 (4), 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JA, et al. , 2000. Early androgen treatment decreases cognitive function and catecholamine innervation in an animal model of ADHD. Behav. Brain Res 107 (1), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittelson DB, 2004. Nanoparticle emissions on Minnesota highways. Atmos. Environ. 38, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, 2015. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Indian J. Pediatr 82 (3), 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, McCarthy MM, 2014. A Starring Role for Microglia in Brain Sex Differences. Neuroscientist. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, et al. , 2013. Microglia are essential to masculinization of brain and behavior. J. Neurosci 33 (7), 2761–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, et al. , 2012. Effect of nanoparticle-rich diesel exhaust on testosterone biosynthesis in adult male mice. Inhal. Toxicol 24 (9), 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, et al. , 2005. Characteristics of metals in nano/ultrafine/fine/coarse particles collected beside a heavily trafficked road. Environ. Sci. Technol 39 (21), 8113–8122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Kozlowski AM, 2011. The increasing prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disorders 5 (1), 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, et al. , 2009. The epigenetics of sex differences in the brain. J. Neurosci 29 (41), 12815–12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Nugent BM, Lenz KM, 2017. Neuroimmunology and neuroepigenetics in the establishment of sex differences in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 18 (8), 471–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Herold K, Stockman SL, 2018. Fast, furious and enduring: sensitive versus critical periods in sexual differentiation of the brain. Physiol. Behav 187, 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mier D, Kirsch P, 2017. Social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci 30, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, et al. , 1997. Testosterone is correlated with regional morphology of the human corpus callosum. Brain Res. 767 (2), 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers YH, 2014. Increasing prevalence, changes in diagnostic criteria, and nutritional risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. ISRN Nutr. 2014, 514026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorster G, Ferin J, Lehnert BE, 1994. Correlation between particle size, in vivo particle persistence, and lung injury. Environ. Health Perspect 102 (Suppl 5), 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono N, et al. , 2008. Detrimental effects of prenatal exposure to filtered diesel exhaust on mouse spermatogenesis. Arch. Toxicol 82 (11), 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomba S, et al. , 2012. Pervasive developmental disorders in children of hyperandrogenic women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal case-control study. Clin.Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 77 (6), 898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, et al. , 2004. Air pollution from traffic and schizophrenia risk. Schizophrenia Res. 66 (1), 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana SV, 2014. Perspectives in endocrine toxicity of heavy metals–a review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res 160 (1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Barone S, 2000. Jr., Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (Suppl 3), 511–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, et al. , 2013a. Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the children of Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Environ. Health Perspect. 121 (8), 978–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, et al. , 2013b. Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the children of Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Environ. Health Perspect. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romijn HJ, Hofman MA, Gramsbergen A, 1991. At what age is the developing cerebral cortex of the rat comparable to that of the full-term newborn human baby? Early Hum. Dev 26 (1), 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudel RA, Perovich LJ, 2009. Endocrine disrupting chemicals in indoor and outdoor air. Atmos. Environ. (1994) 43 (1), 170–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzhetsky A, et al. , 2014. Environmental and state-level regulatory factors affect the incidence of autism and intellectual disability. PLoS Comput. Biol 10 (3), e1003518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma SM, Pfaff DW, 2014. Etiologies underlying sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Neuroendocrinol 35 (3), 255–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HM, Mason JI, Sharpe RM, 2009. Steroidogenesis in the fetal testis and its susceptibility to disruption by exogenous compounds. Endocr. Rev 30 (7), 883–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique S, et al. , 2011. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children chronically exposed to high level of vehicular pollution. Eur. J. Pediatr 170 (7), 923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JL, et al. , 2010. Behavioural phenotyping assays for mouse models of autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 11 (7), 490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareen RS, Kamboj MK, 2012. Role of endocrine factors in autistic spectrum disorders. Pediatr. Clin.North Am 59 (1), 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B, Jick H, Maclaughlin D, 2013. Prevalence and incidence rates of autism in the UK: time trend from 2004–2010 in children aged 8 years. BMJ Open 3 (10), e003219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjalve H, Henriksson J, 1999. Uptake of metals in the brain via olfactory pathways. Neurotoxicology 20 (2–3), 181–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen E, et al. , 2012. Neurobehavioral effects of exposure to traffic-related air pollution and transportation noise in primary schoolchildren. Environ. Res 115, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, 2002. Functional cross‐talk between the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐gonadal and‐adrenal axes. J. Neuroendocrinol 14 (6), 506–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk HE, et al. , 2011. Residential proximity to freeways and autism in the CHARGE study. Environ. Health Perspect 119 (6), 873–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk HE, et al. , 2013. Traffic-related air pollution, particulate matter, and autism. JAMA Psychiatry 70 (1), 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk HE, et al. , 2014. Autism spectrum disorder: interaction of air pollution with the MET receptor tyrosine kinase gene. Epidemiology 25 (1), 44–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS, et al. , 1990. Paradoxical effects of maternal stress on fetal steroids and postnatal reproductive traits in female mice from different intrauterine positions. Biol. Reprod 43 (5), 751–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, et al. , 2009. Association of traffic-related air pollution with children’s neurobehavioral functions in Quanzhou, China. Environ. Health Perspect 117 (10), 1612–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Kurita M, 2001. The masculinization of the fetus during pregnancy due to inhalation of diesel exhaust. Environ. Health Perspect 109 (2), 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Oonuki Y, 1999. Inhalation of diesel engine exhaust affects spermatogenesis in growing male rats. Environ. Health Perspect 107 (7), 539–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl D, et al. , 2005. mobile platform mesurements of ultrafine particles and associated pollutant concentrations on freeways and residential streets in Los Angeles. Atmos. Environ 39, 3597–3610. [Google Scholar]

- Windham GC, et al. , 2006. Autism spectrum disorders in relation to distribution of hazardous air pollutants in the san francisco bay area. Environ. Health Perspect 114 (9), 1438–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yackerson NS, et al. , 2013. The influence of air-suspended particulate concentration on the incidence of suicide attempts and exacerbation of schizophrenia. Int. J. Biometeorol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, et al. , 2006. In utero exposure to diesel exhaust increased accessory reproductive gland weight and serum testosterone concentration in male mice. Environ. Sci 13 (3), 139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, et al. , 2010. Effects of fetal exposure to carbon nanoparticles on reproductive function in male offspring. Fertil. Steril 93 (5), 1695–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.