Abstract

Objective

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women and has the highest mortality rate among the women around the world. Early diagnosis of this cancer increases the survival of the patients. The aim of this study was to determine the predictor factors for breast self-examination (BSE) based on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) among female healthcare workers in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Materials and Methods

This analytical-descriptive study was conducted on 501 employed women in age range of 20–61 years old in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences in west of Iran during 2018. Participants in the study were random stratified sampling selected. Data collection tools were demographic information and the constructs of PMT. The data were analyzed by descriptive statistics and the logistic regression tests.

Results

The results showed that only 9% of participants performed BSE regularly and monthly. The most important reason for lack of BSE was its triviality. Linear regression analysis showed that the structure of perceived threat appraisal is the predictor of the intention to perform BSE (R2=0.027). Moreover, the logistic regression analysis showed that the protection motivation construct was a strong predictor for BSE (R2=0.25).

Conclusion

The frequency of practice of BSE in female healthcare workers is low. Therefore, it is imperative to periodically emphasize the importance of early breast cancer diagnosis for them and the design of educational programs based on the PMT can increase the regular of BSE behavior.

Keywords: Breast cancer, breast self-examination, protection motivation theory, women

Introduction

It is the most common cancer in women and is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women (1). According to the American Cancer Society, in the United States, 252,710 new cases of breast cancer was diagnosed in 2017 and 40,610 of them died (2). In Iran, the breast cancer is the first common cancer among women and accounts for 21.4% of all malignancies in women (3). Breast cancer, in addition to mortality, has other consequences including changes in social relationships and marriages, changes in mental image, less sexual attractiveness, less independence, pain and suffering, depression, fear of recrudescing the disease, disability, and financial problems (4).

The most common age of death due to the breast cancer in developing countries, including Iran, is between the ages of 49–40, while the age of death in developed countries is observed in the post-menopausal ages. If this cancer can be diagnosed at an early step, it can be treated and the screening can be used for its diagnosis (5). Surveillance and epidemiology of the disease have shown that the5-year survival rate is 93–100 percent by its diagnosis in the early steps (I-II steps), while its diagnosis after these steps (III-IV steps) decreases the survival rate to 22–72% (6). The studies have shown that BSE by the individual is the most important measure in identifying the tumor in the early steps; so that, more than 65% of the lumps in breast are diagnosed by the patient themselves, but, despite the high efficiency of breast self-examination in reducing the mortality, the findings of the previous studies show that the compliance rate of this behavior among women in different populations is low (7).

Screening methods for the early diagnosis of this fatal disease are including Mammography, BSE and Clinical breast examinations (CBE) (8). BSE is an easy, inexpensive and cost-effective technique and it does not need any special equipment that increases the awareness of individuals about breast health and is a helpful technique to diagnose palpable lumps in the early steps (9, 10). However, there is a debate about the effectiveness of BSE in early diagnosis of breast cancer. But this method is still an important screening tool for early diagnosis of breast cancer in developing countries (11). All women should start the BSE at the age of 20 and become familiar with their breast appearance and report any changes to their doctor quickly (12). The rate of BSE in American women varied from 29% to 63%. Similar results have been reported in similar studies in Canada, Jordan and Thailand (13). The results of a study in Turkey showed that only 21.9% BSE and 12.5% mammograms were conducted among employed women (physician, nurse and midwife) (14).

Meanwhile, the female healthcare workers are one of the at-risk groups that it is due to their daily work (15). The knowledge of employed individuals towards the breast cancer, diagnosis and treatment techniques is at the average level, but their attitude and practice are not favorable (16). This group does not screen for BSE because of being busy, lacking time (17) and forgetfulness (18). Long working hours of female workers are known to be associated with specific clinical diseases. Long working hours and so time limitation for self-care may make these women vulnerable to the disease. Also, female workers have an important role in health status of country (19).

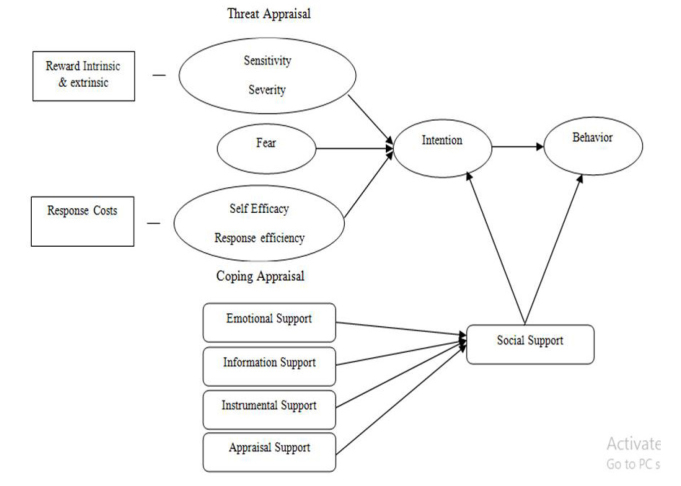

Considering the problems in creating, maintaining and continuing the screening behavior and complexity of this behavior, it is necessary to use the theories and models of behavior change in this field because the theory and models determine the main factors that affect the desired behavior (20). One of the theories used in health education is the PMT (Figure 1), which was proposed by Rogers in 1975 to explain the effects of fear on attitudes and health behaviors (21). This theory includes two stages of threat appraisal and coping appraisal and fear construct. The threat appraisal emphasizes the factors that increase or decrease the possibility of performing the inconsistent responses, such as avoiding protective behavior or denying health threats. The threat appraisal consists of perceived susceptibility construct, perceived severity and perceived rewards. The coping appraisal emphasizes the coping responses with the health threat and the factors that increase and decrease the possibility of consistent responses. This moderator step consists of perceived self-efficacy and perceived response efficacy and perceived response cost. The fear is Mediator variable between the perceived susceptibility and perceived severity and threat appraisal, and the protection motivation causes and promotes the health behaviors (22–24).

Figure 1.

Protection Motivation Theory Framework

Different studies have been conducted to determine the relevant factors for BSE because these factors can be used to design the educational programs (25). Regarding the importance of the subject, this study aimed to determine the predictor factors of the BSE based on the PMT among employed women in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Materials and Methods

Design

This research is a descriptive-analytical study.

Study population and Sampling method

This research which was of the cross-sectional type, was conducted on, 501 women were selected among the individual at age range of 20 to 61 years old in 2018.

Sampling method was multi-stage (Random Stratified Sampling). Considering that Hamadan University of Medical Sciences has educational, health, medical and office units. Each of these units includes the following sections: in the education units, there are 7 school; in the health units, there are 20 comprehensive health centers and health centers; in the medical units, there are 5 hospitals; and, in the staff units, there are seven sections (educational, health, medical, support, student, research and technology and social). Therefore, the sample was randomly selected from each of the above four domains (Educational unit 77 people, Health unit 71 people, Medical unit 302 people and Staff unit 51 people). The sampling method was as follows: At first, the number of employees in each unit was obtained and then, based on the number of people in each unit, the names of employed women in each domain were given to the Randomizer program and the subjects were selected. Then, the researcher gave a questionnaire for its completion to the people who their names were selected. In case of lack of cooperation or absence of these people, the selected questionnaires were given to their colleagues for its completion. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were the consent and willingness to participate in the study, the age range between 20 to 61 years and the lack of breast cancer history. Exclusion criteria were breast cancer at the time of study and incomplete completion of the questionnaire.

Data collection

Data were collected using two self-reporting questionnaires, which were completed by the participants after obtaining written informed consent.

Data collection instruments

A researcher-made questionnaire was self-reported and consisted of two parts; the first demographic information and knowledge, and the second PMT constructs. The questionnaire was developed by the authors based on an extensive review of the literature (26, 27). Demographic variables included age, marital status, education, contraceptive method, and duration of taking contraceptive pills, menopause status, and workplace, age of delivery and age of menarche and duration of breastfeeding, physical activity and contact with the cancerous patient. The knowledge questionnaire was consisted of 10 items (Yes/No) and the questions about the cancer were including the history of hormone therapy (hormone replacement therapy in during menopausal period) (Yes/No), family history of breast cancer (Yes/No), breast disease (Cyst or Fibro adenoma), history of BSE, influential people on the conducting the BSE and, ultimately, the reason for lack of conducting the BSE.

The questions were designed based on the PMT including perceived susceptibility construct (5 Item), perceived severity construct (8 Item), perceived self-efficacy construct (6 Item), construct of perceived response efficacy (7 Item), construct of response cost (4 Item), construct of perceived reward (5 Item), construct of fear (4 Item), intention construct (4 Item). All of the scales were positively related to the screening behavior, except for the cost response and perceived reward, which were negatively associated. The PMT questions were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The dependent variable, practices related to BSE, was assessed on the frequency of BSE. The BSE score was coded in non-practice=1 and regular practice (monthly)=2.

Pilot testing of questionnaire

The questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of experts consisted of 10 specialists in health education and promotion. Content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated through experts’ opinion, and based on Lawshe’s table, items with the score of 0.78 and more remained in the questionnaire (28) Content validity index (CVI) was calculated by researches using a four-point scale assessed by Waltz and Bausell (29). The score of 0.79 was considered as the least suitable CVI. Face validity of the questionnaire was examined by 6 women so that all questions were read to them and women’s understanding and the difficulty level of questions were assessed and then the proposed correction was applied.

To determine the reliability, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and the Test-Re test were used. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.83 and the correlation coefficient was 0.99.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences with Ethics Identity of IR.UMSHA.REC.1396.609. The researcher also pledged to keep all information confidential. Participation in this study was voluntarily and the participants could discontinue this when they were not interested to cooperate for any reason. Before collecting data, the researcher presented a document containing the information about the study objectives, to presidency of all relevant departments, and asked them to participate in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were checked for normality using one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The data was distribution normal. The basic demographic characteristics of the participants were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The Chi-square, Pearson statistical analysis was used for bivariate analysis. Moreover, for controlling the effect of confounding variables, we used the linear and logistic regression model for analysis of data. Data analysis was performed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences version 23 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA) software at a significant level of 0.05.

Results

Seven questionnaires (1%) were filled by participants’ colleagues, because of being absent and lack of participation. Five questionnaires (1%) were excluded, because of uncompleted filling. Five questionnaires (1%) were excluded, because of having breast cancer.

The mean age of the participants was 37.1±8.35 years old and the majority of women (80.4%) were married. Most women had the MSc degree (67.5%). The mean age of marriage was 24.33±4.9 years, the mean age of delivery was 27.34±4.48 years, the number of children was 1.28±0.86, the duration of breastfeeding was 23.49±22.57 month, and the mean duration of taking the contraceptive pills was 24.93±30.81 months. The most common contraceptive method was withdrawal (45.9%). Most of the participants were inactive for physical activity (54.5%). (Table 1). According to the results, 35.9% of the individuals never performed the BSE and only 9% performed this behavior regularly and monthly.

Table 1.

Demographic variables of participants (n=501)

| Variables | N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | <40 years | 337 | 67.3 |

| 40> years | 164 | 32.7 | |

| Marital status | Married | 403 | 80.4 |

| Single | 98 | 19.6 | |

| Educational status | Diploma | 35 | 7 |

| Technician | 37 | 7.4 | |

| Bachelor | 338 | 67.5 | |

| MSc | 74 | 14.8 | |

| PhD | 17 | 3.4 | |

| Number of children | No Child | 80 | 19.8 |

| 1–2 | 308 | 76.8 | |

| ≥3 | 15 | 3.7 | |

| History of breast disease | Yes | 44 | 8.8 |

| No | 457 | 91.2 | |

| Family history of breast cancer | Yes | 63 | 12.6 |

| No | 438 | 87.4 | |

| Menopause | Yes | 46 | 9.2 |

| No | 455 | 90.8 | |

| Workplace | Health Unit | 85 | 17 |

| Therapeutic unit | 308 | 61.5 | |

| Education unit | 58 | 11.6 | |

| Head office | 50 | 10 | |

| Hormone replacement therapy during menopausal period | Yes | 6 | 1.2 |

| No | 495 | 98.8 | |

| Seeing a patient with breast cancer | Yes | 202 | 40.3 |

| No | 299 | 59.7 | |

| Physical Activity | Yes | 228 | 45.5 |

| No | 273 | 54.5 | |

| Duration of breastfeeding (month) | (Mean±SD) | 23.49±22.57 | |

| Age of marriage (yrs) | (Mean±SD) | 24.33±4.09 | |

| Age of delivery (yrs) | (Mean±SD) | 27.34±4.40 | |

| Duration of taking the contraceptive pills (month) | (Mean±SD) | 24.93±30.81 | |

| Age of menarche (yrs) | (Mean±SD) | 13.77±1.54 | |

| Contraceptive method | Withdrawal | 185 | 45.9 |

| Condom | 115 | 28.5 | |

| Contraceptive pills | 16 | 4 | |

| IUD | 19 | 4.7 | |

| DMPA | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Vasectomy | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Tubectomy | 12 | 3 | |

| Hysterectomy | 2 | 0.5 | |

| No contraceptive method | 46 | 11.4 |

The relationship between demographic variables and BSE has presented in Table 2. Results showed that there is a significant association between BSE and marital status (p=0.004), education (p=0.02), workplace (p=0.01), history of breast disease (p=0.006) and seeing a patient with breast cancer (p=0.001).

Table 2.

Relationship between demographic variables and BSE (n=501)

| Variables | BSE performing | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=321) | No (n=180) | |||

| Age (yrs) | <40 years | 217 (64.4) | 120 (35.6) | 0.453 |

| 40> years | 104 (63.4) | 60 (36.6) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 270 (67) | 133 (33) | 0.004 |

| Single | 51 (52) | 47 (48) | ||

| Educational status | Diploma | 16 (45.7) | 19 (54.3) | 0.024 |

| Technician | 24 (64.9) | 13 (35.1) | ||

| Bachelor | 219 (64.8) | 119 (35.2) | ||

| MSc | 48 (64.9) | 26 (35.1) | ||

| PhD | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) | ||

| Number of Children | No Child | 51 (63) | 29 (37) | 0.441 |

| 1–2 | 212 (68.8) | 96 (31.2) | ||

| ≥3 | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | ||

| History of breast disease | Yes | 36 (81.8) | 8 (18.2) | 0.006 |

| No | 285 (62.4) | 172 (37.6) | ||

| Family history of breast cancer | Yes | 43 (68.3) | 20 (31.7) | 0.277 |

| No | 278 (63.5) | 160 (36.5) | ||

| Menopause | Yes | 27 (58.7) | 19 (41.3) | 0.260 |

| No | 294 (64.6) | 161 (35.4) | ||

| Workplace | Health Unit | 62 (72.9) | 23 (27.1) | 0.013 |

| Therapeutic unit | 200 (64.9) | 108 (35.1) | ||

| Education unit | 31 (53.4) | 27 (46.6) | ||

| Head office | 28 (56) | 22 (44) | ||

| Hormone replacement therapy during menopausal period | Yes | 6 (100) | 0 | 0.068 |

| No | 315 (63.6) | 180 (36.4) | ||

| Seeing a patient with breast cancer | Yes | 146 (72.3) | 56 (27.7) | 0.001 |

| No | 175 (58.5) | 124 (41.5) | ||

Pearson correlation coefficient showed that there was a positive correlation between perceived threat appraisal with perceived severity and fear, and it had a weak and negative correlation with self-efficacy construct, response cost construct and perceived reward construct, and motivation protection. There was no correlation between the construct of Coping appraisal and protection motivation construct and there was a weak and negative correlation between construct of Coping appraisal and perceived response costs and perceived reward construct (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean, SD, and range of scores and Pearson correlation coefficients among the constructs of PMT (n=501)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean±SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Susceptibility | 1 | 16.36±3.72 | 5–25 | |||||||||

| 2. Severity | 0.31** | 1 | 29.81±5.98 | 8–40 | ||||||||

| 3. Self-Efficacy | 0.24** | 0.25** | 1 | 24.58±3.80 | 6–30 | |||||||

| 4. Response Efficacy | 0.17** | 0.29** | 0.59** | 1 | 27.78±4.86 | 7–35 | ||||||

| 5. Response Costs | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.36** | 0.23** | 1 | 14.81±2.81 | 4–20 | |||||

| 6. Reward | 0.11* | 0.02 | 0.4** | 0.34** | 0.53** | 1 | 20.30±3.34 | 5–25 | ||||

| 7. Fear | 0.15** | 0.29** | 0.04 | 0.11** | 0.06 | −0.01 | 1 | 16.20±3.69 | 4–20 | |||

| 8. Protection Motivation | 0.22** | 0.13** | 0.42** | 0.30** | 0.40** | 0.38** | −0.09 | 1 | 14.12±3.18 | 4–20 | ||

| 9. Threat appraisal (Sus+Sev-Rew)a | 0.40** | 0.61** | −0.09* | 0.04 | −0.44** | −0.71** | 0.21** | −0.15** | 1 | |||

| 10. Coping appraisal (SE+RE-RC)b | 0.18** | 0.31** | 0.34** | 0.50** | −0.67** | −0.17** | 0.13** | −0.06 | 0.35** | 1 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

A: Susceptibility+Severity-Reward

B: Self-Efficacy+Response Efficacy-Response Costs

The results of the table show that the perceived threat appraisal construct predicts the intention to perform the BSE. Therefore, in consideration of the other constant constructs, the average score of intention to perform the BSE decreased by 0.13 for one unit-score of perceived threat appraisal (R2=0.027) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Linear regression analysis to predict the protection motivation (intention) based on the constructs of PMT

| Variables | Coefficient | SE | β | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Fear | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.02 | 0.145 |

| Threat appraisal | −0.48 | 0.17 | −0.13 | −0.83 | −0.14 | 0.006 |

| Coping appraisal | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.007 | −0.42 | 0.36 | 0.881 |

| Constant | 14.80 | 0.67 | -- | 13.48 | 16.13 | <0.001 |

β: standardized regression coefficient; SE: standard error

The results of the table show that for one unit increase in intention, the chance BSE increased by 55%. The protection motivation construct was observed to be a strong predictor for BSE (R2=0.25) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis to predict the BSE based on the constructs of PMT

| Variables | Coefficient | SE | Wald | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Protection motivation | −0.44 | 0.044 | 99.32 | 1.55 | 1.42 | 1.69 | <0.001 |

| Constant | −5.35 | 0.60 | 78.06 | 0.005 | -- | -- | <0.001 |

SE: standard error; OR: odds ratio

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the factors affecting the BSE based on the PMT in employed women in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. If the BSE be performed regularly, it can help the diagnosis of the abnormal breast changes and early detection of breast cancer (30). In this study, only 9% of the participants performed the BSE regularly. The percentage of monthly BSE in the studies conducted by Birhane (31), Didarlo (30) and Gonzales (32) was respectively observed to be 12%, 24% and 7.8%. In a study conducted by Negeri et al. (33), which was conducted on female health professionals, 33% of women performed the monthly BSE.

There was a significant association between BSE and marital status. This result was inconsistent with the study conducted by Zavare-Akhtari (11) but in the Friestudy (34), the married women reported more BSE, which is similar to the results of the present study. In the present study, it seems that the married women have the support of their spouses and children, which it can increase the BSE. In this study, there was a significant association between BSE and workplace. This result was consistent with Wall (35) and Fenga (36). This result suggests that understanding the organizational and structural factors such as access to services and the quality of services can be effective on screening behaviors (33).

The results of present study showed that there is higher probability for BSE among the individuals with a history of breast disease that it was consistent with the study of Bahrami et al. (37) and Ogunbede et al. (38). The reason for this result is due to the increasing the perceived severity (36) and susceptibility and perceived risk of cancer, which leads to increase the follow-up of people about health. The other results of this study showed that the BSE was higher in people with lower educational levels. This result was not consistent with the Friestudy (34). The reason for this can be attributed to this fact that the individual with higher educational levels do not believe in the effectiveness and usefulness of BSE.

Other results of this study showed that the BSE was great among the individuals who had co-workers with breast cancer at the workplace. This increase in behavior can be explained by increasing the perceived susceptibility of individuals. In the present study, the most important motivators for BSE were the co-workers and physicians that it is consistent with Hassan et al. (39) study. Therefore, they can be used to influence and to educate the women for conducting the screening behaviors.

Other results clarified that most important reason for lack of BSE was its triviality. This is due to the fact that there is a lack of time in employed people, which it is led to triviality of screening behavior. In the study conducted by Akhtari-Zavare et al. (40), the reason for neglecting the BSE was mentioned to be the lack of familiarity with its technique.

As the most important hypothesis of the PMT, as well as the most important hypothesis of the present study, the results showed that threat appraisal predicted the intention of BSE. In other words, according to the hypothesis of the PMT that suggests two paths of threat appraisal and a coping appraisal, only the threat appraisal pathway has an ability to predict the intention of BSE. This finding is consistent with the results of some similar studies (41, 42). Also, in the studies conducted by Morowati Sharifabad et al. (43), Plotnikoff et al. (44) the construct of the perceived response efficacy was introduced as the predictor. Therefore, the educational program should be emphasized on the susceptibility and severity of these behaviors. Moreover, paying attention to the barriers to implement the screening behavior in women is also important.

The results of this study showed that the PMT can predict 25% of BSE. This theory predicts a screening behavior up to 15.6% in the Rahaei et al. study (45). It seems that those who have high levels of protection motivation are more motivated to control the risk and to accept the recommended behaviors (46).

The present study has limitations. First, Given that BSE by the American Cancer Society is no longer recommended However one of the most important reasons to do regular breast self-examination is so that women know what is normal for their breasts. If women see or feel something different or unusual while performing BSE see their doctor without delay, second, the results cannot be generalized to all women working in all environments, because the information was exclusively collected from the women employed in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences; and third, the information was self-report.

Therefore, it is suggested that women employed in medical universities in other provinces and the women employed in the other organizations and workplaces should be examined.

In conclusion, the frequency of practice of BSE in female healthcare workers is low. Therefore, it is imperative to periodically emphasize the importance of diagnosis of breast cancer in early steps and the design of educational programs based on protection motivation theory can increase the regular of BSE behavior.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1396.609)

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patients who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - S.B., M.D.; Design - M.D., S.B., M.B.; Supervision - S.B.; Resources - L.M., M.B.; Materials - S.B., M.D., M.B.; Data Collection and/or Processing - M.D.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - L.M., Y.M.; Literature Search - M.D.; Writing Manuscript - M.D., S.B.; Critical Review - M.B., Y.M.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: This study was supported by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant no. 9609215872).

References

- 1.Wu WW. Linking Bayesian networks and PLS path modeling for causal analysis. Expert Syst Appl. 2010;37:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2009.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rebecca S, Kimberly M, Ahmedin J. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalili S, Shojaiezadeh D, Azam K, Kheirkhah Rahimabad K, Kharghani Moghadam M, Khazir Z. The effectiveness of education on the health beliefs and practices related to breast cancer screening among women referred to Shahid Behtash Clinic, Lavizan area, Tehran, using health belief model. J Health. 2014;5:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vatannavaz E, Taymoori P. Factors Related in Mammography Screening Adoption: an Application of Extended Parallel Process Model. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajian-Tilaki K, Auladi S. Health belief model and practice of breast self-examination and breast cancer screening in Iranian women. Breast Cancer. 2014;21:429–423. doi: 10.1007/s12282-012-0409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhtari-Zavare M, Juni MH, Said SM, Ismail IZ, Latiff LA, Ataollahi Eshkoor S. Result of randomized control trial to increase breast health awareness among young females in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:738. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3414-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheppard VB, Huei-yu Wang J, Eng-Wong J, Martin SH, Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Luta G. Promoting mammography adherence in underserved women: The telephone coaching adherence study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baliga MS, Rao S, Rao P, Kumar A, Tonse R, Mathew M, Mathew JM. Knowledge of cancer and self-breast examination among women working in agricultural sector in Mangalore, Karnataka, India. IJAR. 2017;3:200–202. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trimmer JS, Cooperman SS, Tomiko SA, Zhou JY, Crean SM, Boyle MB, Kallen RG, Sheng ZH, Barchi RL, Sigworth FJ. Sociocultural factors associated with breast self-examination among Iranian women. Neuron. 1989;3:33–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan MR, Ghazi HF, Mohamed AS, Jasmin SJ. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among female non-medical students in universiti Kebangasaan Malaysia (UKM) in Bangi. MJPHM. 2017;17:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akhtari-Zavare M, Ghanbari-Baghestan A, Latiff LA, Matinnia N, Hoseini M. Knowledge of breast cancer and breast self-examination practice among Iranian women in Hamedan, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6531–6534. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.16.6531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Society A. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures Atlanta: Inc 2017ȓ2018. American Cancer Soc. 2017:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berdi GA, Charkazi A, Razzaq NA. Knowledge, practice and perceived threat toward breast cancer in the women living in Gorgan, Iran. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canbulat N, Uzun Ö. Health beliefs and breast cancer screening behaviors among female health workers in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39:16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olanloye EE, Ajayi IO, Akpa OM. Practice and Efficiency of Breast Self-Examination Among Female Health Workers In A Premier Tertiary Hospital In Nigeria. J American Sci. 2017;13:121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazzal Z, Sholi H, Sholi S, Sholi M, Lahaseh R. Mammography Screening Uptake among Female Health Care Workers in Primary Health Care Centers in Palestine-Motivators and Barriers. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2549–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naghibi A, Jamshidi P, Yazdani J, Rostami F. Identification of Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Screening Based on the PEN-3 Model among Female School Teachers in Kermanshah. Iran J Health Educ and Health Promot. 2016;4:58–64. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.ihepsaj.4.1.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keshavarz Z, Simbar M, Ramezankhani A. Factors for Performing Breast and Cervix Cancer Screening by Iranian Female Workers: A Qualitative-model Study. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1587–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moodi M, Rezaeian M, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad G. The study of mammography screening behavior based on stage of change model in Isfahanian women of age 40 and older: A population-based study. ZUMS J. 2013;21:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arabtali B, Solhi M, Shojaeezadeh D, Gohari M. Related factors in using Hearing protection device based on the Protection motivation theory in Shoga factory workers, 2011. Iran Occup Health. 2015;12:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karmakar M, Pinto SL, Jordan TR, Mohamed I, Holiday-Goodman M. Predicting adherence to aromatase inhibitor therapy among breast cancer survivors: an application of the protection motivation theory. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2017;11:1178223417694520. doi: 10.1177/1178223417694520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fry RB, Prentice-Dunn S. Effects of a psychosocial intervention on breast self-examination attitudes and behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2005;21:287–295. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahaei Z, Ghofranipour F, Morowatisharifabad MA. Psychometric properties of a protection motivation theory questionnaire used for cancer early detection. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2015;12:69–79. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2015.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarawneh E, Al-Attiyat N. Exploration of barriers to breast-self examination and awareness: a review. ME-JN. 2013;7:3–7. doi: 10.5742/MEJN.2013.76333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khosravi V, Barati M, Moeini B, Mohammadi Y. Prostate Cancer Screening Behaviors and the Related Beliefs among 50- to 70-year-old Men in Hamadan: Appraisal of Threats and Coping. J Educ Community Health. 2018;4:20–31. doi: 10.21859/jech.4.4.20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehdari T, Hassani L, Shojaeizadeh D, Hajizadeh E, Nedjat S, Abedini M. Predictors of Iranian women’s intention to first papanicolaou test practice: An application of protection motivation theory. Indian J Cancer. 2016;53:50–53. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.180857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity1. Personnel psychology. 1975;28:563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: design statistics and computer analysis. Philadelphia: Davis FA; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Didarloo A, Nabilou B, Khalkhali HR. Psychosocial predictors of breast self-examination behavior among female students: an application of the health belief model using logistic regression. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:861. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4880-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birhane N, Mamo A, Girma E, Asfaw S. Predictors of breast self-examination among female teachers in Ethiopia using health belief model. Arch of Public Health. 2015;73:39. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzales A, Alzaatreh M, Mari M, Saleh AA, Alloubani A. Beliefs and Behavior of Saudi Women in the University of Tabuk Toward Breast Self Examination Practice. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:121–126. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Negeri EL, Heyi WD, Melka AS. Assessment of breast self-examination practice and associated factors among female health professionals in Western Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. International J Med Sci. 2017;9:148–157. doi: 10.5897/IJMMS2016.1269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grosse Frie K, Ramadas K, Anju GA, Mathew BS, Muwonge R, Sauvaget CS, Thara ST, Sankaranarayanan R. Determinants of participation in a breast cancer screening trial in Trivandrum district, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:7301–7307. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.12.7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wall KM, Nú-ez-Rocha GM, Salinas-Martínez AM, Sánchez-Pe-a SR. Determinants of the use of breast cancer screening among women workers in urban Mexico. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenga C. Occupational exposure and risk of breast cancer (Review) Biomed Rep. 2016;4:282–292. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bahrami M, Taymoori P, Bahrami A, Farazi E, Farhadifar F. The Prevalence of breast and Cervical cancer screening and related factors in woman who refering to health center of Sanandaj city in 2014. Zanco J of Med Sci. 2015;2015:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogunbode A, Fatiregun A, Ogunbode O. Breast self-examination practices in Nigerian women attending a tertiary outpatient clinic. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52:520–524. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.178376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassan N, Ho WK, Mariapun S, Teo SH. A cross sectional study on the motivators for Asian women to attend opportunistic mammography screening in a private hospital in Malaysia: the MyMammo study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:548. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1892-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akhtari-Zavare M, Juni MH, Ismail IZ, Said SM, Latiff LA. Barriers to breast self examination practice among Malaysian female students: a cross sectional study. Springerplus. 2015;4:692. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan Y, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Chen X, Xie N, Chen J, Yang N, Gong J, Macdonell KK. Application of the protection motivation theory in predicting cigarette smoking among adolescents in China. Addict Behav. 2014;39:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barati M, Amirzargar MA, Bashirian S, Kafami V, Mousali AA, Moeini B. Psychological Predictors of Prostate Cancer Screening Behaviors Among Men Over 50 Years of Age in Hamadan: Perceived Threat and Efficacy. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2016;9:e4144. doi: 10.17795/ijcp-4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MorowatiSharifabad M, Sarvestani M, Firoozabadi A, Fallahzadeh H. Perceived Rewards of Unsafe Driving and Perceived Costs of safe driving as Predictors of Driving Status in Yazd, Iran. J Res Health. 2011;7:422–433. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plotnikoff RC, Higginbottom N. Protection motivation theory and exercise behavior change for the prevention of coronary heart disease in a high risk Australian representative community sample of adults. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7:87–98. doi: 10.1080/13548500120101586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahaei Z, Ghofranipour F, Morowatisharifabad M, Mohammadi E. Determinants of Cancer Early Detection Behaviors:Application of Protection Motivation Theory. Health Promot Perspect. 2015;5:138–146. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2015.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malmir S, Barati M, Khani AJ, Bashirian S, Hazavehei SMM. Effect of an Educational Intervention Based on Protection Motivation Theory on Preventing Cervical Cancer among Marginalized Women in West Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:755–761. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]