SUMMARY:

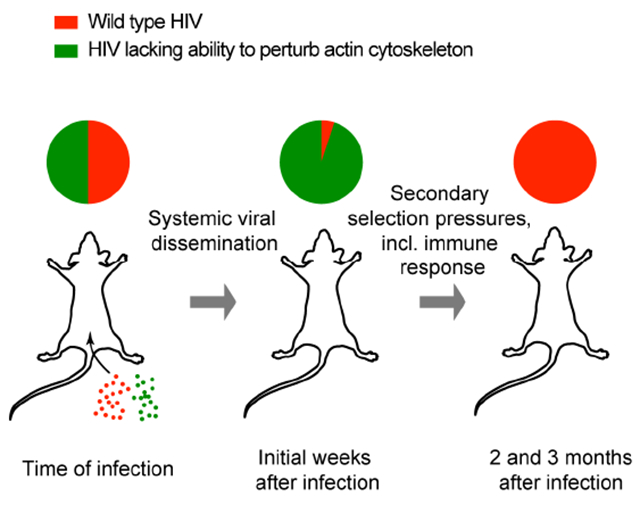

HIV-1 primarily infects T lymphocytes and uses these motile cells as migratory vehicles for effective dissemination in the host. Paradoxically, the virus at the same time disrupts multiple cellular processes underlying lymphocyte motility, seemingly counterproductive to rapid systemic infection. Here we show by intravital microscopy in humanized mice that perturbation of the actin-cytoskeleton via the lentiviral protein Nef, and not changes to chemokine receptor expression or function, is the dominant cause of dysregulated infected T cell motility in lymphoid tissue by preventing stable cellular polarization required for fast migration. Accordingly, disrupting the Nef hydrophobic patch that facilitates actin-cytoskeletal perturbation initially accelerates systemic viral dissemination after female genital transmission. However, the same feature of Nef was subsequently critical for viral persistence in immune-competent hosts. Therefore, a highly conserved activity of lentiviral Nef proteins has dual effects and imposes both fitness costs and benefits on the virus at different stages of infection.

Keywords: HIV-1, T cell migration, humanized mice, Nef, PAK2, Vpu, Env, chemokines, actin-cytoskeleton, mucosal transmission, viral dissemination, intravital microscopy

eTOC Blurb

HIV and other lentiviruses disrupt many functions that facilitate T cell migration. Usmani et al. (2018) reveal that perturbation of the T cell actin cytoskeleton by the viral accessory protein Nef initially restricts viral dissemination, but that the molecular activity underlying this function of Nef subsequently supports viral persistence.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Many retroviruses, including HIV-1, use lymphocytes as their primary targets for replication and chronic persistence. In addition to being generally long-lived, T and B cells are motile, and in particular T cells recirculate through both lymphoid and most if not all non-lymphoid tissues during immune surveillance. Infecting such highly migratory cells may provide retroviruses with transport vehicles that enable their systemic dissemination into host tissue compartments otherwise less accessible to free viral particles moving through extracellular fluids passively via diffusion and convection. We and others have recently started to use multiphoton intravital microscopy (MP-IVM) in humanized mice to investigate the behavior both of free HIV particles and of HIV-infected cells in lymphoid tissues in vivo and found that retrovirally infected lymphocytes retain robust migratory activity in spleen and lymph nodes (LNs) early after infection (Law et al., 2016; Murooka et al., 2012; Sewald et al., 2015). We also observed that trafficking of HIV-infected T cells away from viral transmission sites facilitates efficient systemic spread in the host (Deruaz et al., 2017; Murooka et al., 2012).

Seemingly counterproductively to the benefit of infecting migratory target cells, HIV-1 interferes with a variety of cellular processes that enable cell migration. The multifunctional accessory protein Nef downregulates the expression of several chemokine receptors including, but not limited to the HIV co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 (Hrecka et al., 2005; Michel et al., 2005; 2006; Venzke et al., 2006), and impairs the function of G-proteins these receptors use for signal transduction (Chandrasekaran et al., 2012). Nef also disrupts actin-cytoskeletal turnover, necessary to establish stable cell polarity required for fast cellular migration. This can be achieved through its association with p21-activated kinase (PAK) 2, enabling the formation of a large multiprotein complex containing Nef, PAK2, Rac, Cdc42, Vav, and members of the exocyst complex (Imle et al., 2015; Mukerji et al., 2012). Formation of this complex requires a patch of hydrophobic residues of Nef to facilitate activation of PAK2, which in turn phosphorylates and inactivates the actin-severing protein cofilin to disrupt chemotaxis-driven actin-cytoskeletal turnover (Nobile et al., 2010; Stolp et al., 2012; 2009). Nef also attenuates T cell receptor (TCR)-driven signaling and actin polymerization through a mechanism that is independent of PAK2’s kinase activity and instead depends on PAK2-mediated association of Nef with exocyst proteins (Imle et al., 2015). Another HIV-1 accessory protein, Vpu, has also been reported to inhibit T cell chemotaxis in response to the LN chemokines CCL19 and CCL21 by downregulating their common receptor CCR7 from the surface of infected cells (Ramirez et al., 2014). Finally, HIV envelope proteins exposed on the cell surface during viral budding may alter the ability of infected cells to traffic in vivo by tethering them to uninfected CD4-expressing cells and driving the formation of multinucleated syncytia (Murooka et al., 2012).

The relative importance of described mechanisms for the motility for HIV-infected human T cells in a relevant tissue environment remains unclear. Here we used MP-IVM and fluorescent reporter viruses, in which nef, vpu, and env genes are either not expressed or mutated, in order to examine their respective roles in regulating the migratory behavior of infected T cells in the LN T cell area of BLT humanized mice. We found that either deleting nef or mutating a critical residue in the hydrophobic patch to disable its association with active PAK2 fully restored migration speeds of infected T cells to those of uninfected CD4+ T cells. Deleting env in addition to nef also eliminated tethering and syncytia formation by infected T cells and revealed that Nef impairs organized F-actin polymerization and stabilization of cell polarity required for fast cell migration. In contrast, deleting vpu did not have a measurable effect on T cell motility. Unexpectedly, in a setting of competitive mucosal co-infection, the highly conserved hydrophobic patch that enables PAK2-dependent perturbation of the cytoskeleton rendered HTV-1 less fit during the initial phase of systemic dissemination, compared to virus that lacked this activity. Subsequently, however, at a time when the anti-HIV cytotoxic T cell response is induced and a stable set point of plasma viremia is established, the hydrophobic patch provided a vital advantage to the virus in immune-competent hosts, allowing it to outcompete the initially dominant mutant virus where the patch is disrupted. These observations reveal an important role for this poorly understood feature of Nef for systemic viral persistence that comes at the expense of delayed systemic dissemination.

RESULTS

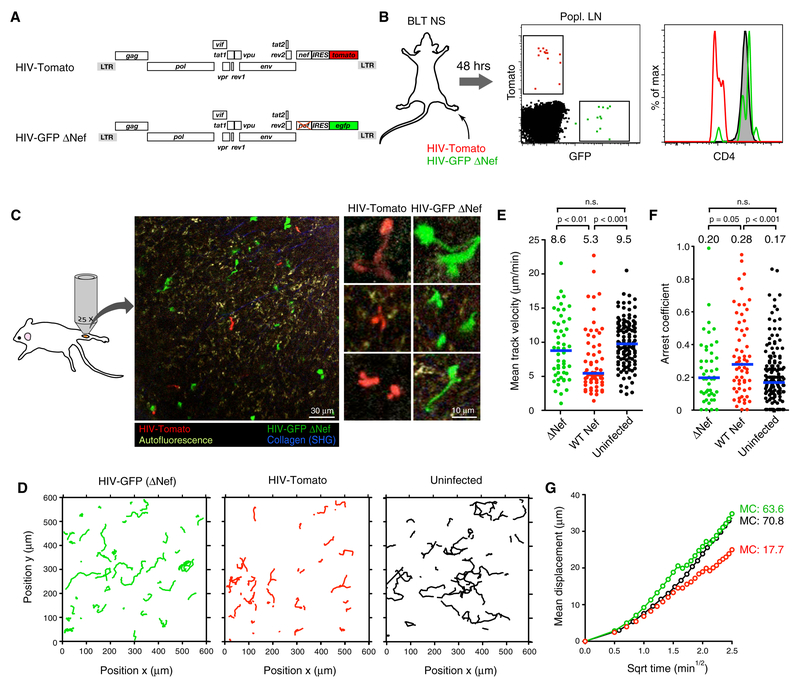

HIV-1 decelerates migration of infected T cells through Nef, but not Vpu

We previously observed that HIV-1 reduces the migration speed of infected T cells in LNs by half, but it remained unclear if this resulted from a specific viral activity on cell motility or from a general cytopathic effect (Murooka et al., 2012). To test the role of Nef in reducing migration speeds of infected human T cells in vivo we constructed a GFP-expressing, CCR5-tropic HIV reporter strain that lacked expression of Nef (HIV-GFP ΔNef) (Fig. 1A). We then infected NOD-scid (NS) BLT humanized mice via footpad injection to examine the behavior of infected cells in the draining popliteal LN by MP-IVM (popLN), as described (Murooka et al., 2012). As an internal control we co-injected virus expressing an intact Nef protein and the monomeric red fluorescent protein dTomato (HIV-Tomato). Both viruses infected comparable numbers of cells in LNs, but only Nef-expressing HIV-Tomato downregulated the CD4 membrane protein on T cells, as expected (Wildum et al., 2006) (Fig. 1B). Cells infected with either virus distributed similarly in tissue and a fraction of cells within both populations showed the elongated cell shapes we previously described as a result of Env-dependent tethering to CD4-expressing cells and multinucleated syncytia formation (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Movie 1) (Murooka et al., 2012). However, the migratory tracks of cells infected with nef-deleted virus were more extended compared to cells infected with HIV expressing WT Nef. Their migratory speed nearly doubled, leading to increased displacement, and their motility resembled that of uninfected human central memory-like CD4+ T cells (‘TCM’) (Fig. 1D-G) (Murooka et al., 2012). Therefore, to the extent that our analysis captures various aspects of cell motility, Nef appears to be the most important regulator of migration in infected cells.

Figure 1: Loss of Nef restores impaired motility of HIV-infected T cells in vivo.

(A) ORF diagrams of HIV reporter strains.

(B) CD4 expression in infected cells in draining popLNs 2 days following footpad co-injection of both reporter strains. Grey histogram shows uninfected LN CD4+ T cells.

(C) An intravital micrograph of a popLN 2 days after infection as shown in (B). Enlarged images to the right highlight HIV-induced elongated morphology in both populations.

(D) Migratory tracks (normalized to max. 15 min duration) of infected cells. Tracks of uninfected TCM were recorded separately in LNs of uninfected BLT mice.

(E) Mean track velocities,

(F) Arrest coefficients, and

(G) Mean displacement (MD) plots of the three populations.

Numbers above graphs and blue lines represent medians. Data are pooled from 12 individual recordings from 3 animals. MC = motility coefficient (in μm × min−1). n.s. = not significant.

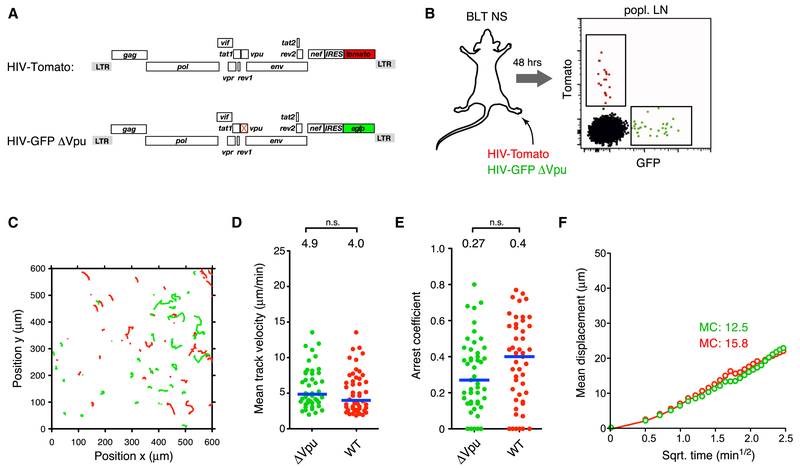

Full restoration of infected cell migration speeds solely through deletion of nef was unexpected given a report that the HIV accessory protein Vpu downregulates expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 and impairs T cell chemotaxis towards the LN chemokine CCL19 (Ramirez et al., 2014). Given the reduced migration speed of mouse T cells lacking CCR7 in mouse LNs (Worbs et al., 2007), and since mouse CCL19 and CCL21 have chemotactic activity on human CCR7 on T cells (Deruaz et al., 2017), Vpu-mediated downregulation of CCR7 would be predicted to decelerate migration of HIV-infected human T cells in LNs of BLT humanized mice as well. However, upon footpad co-injection of HIV-Tomato with a vpu-deleted reporter virus (HIV-GFP ΔVpu) that, as expected, lacked the ability to antagonize the antiviral restriction factor tetherin (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1) (Sauter et al., 2009), we did not detect a significant difference in migration speeds of cells infected with either virus, as both showed restrained motility (Fig. 2B-F and Supplementary Movie 2). Thus, while we cannot exclude more subtle effects of Vpu on migratory behavior, Nef is the major attenuator of motility in HIV-infected T cells in LNs.

Figure 2: Vpu does not attenuate migration of HIV-infected T cells in LNs.

(A) ORF diagrams of indicated HIV reporter strains

(B) Infected cells in draining popLN 2 days following footpad co-injection of both reporter strains.

(C) Migratory tracks,

(D) Mean track velocities,

(E) Arrest coefficients, and

(F) MD plot of HIV-infected cells.

Blue lines and numbers above graphs indicated medians. MC = motility coefficient (in μm × min−1). n.s. = not significant.

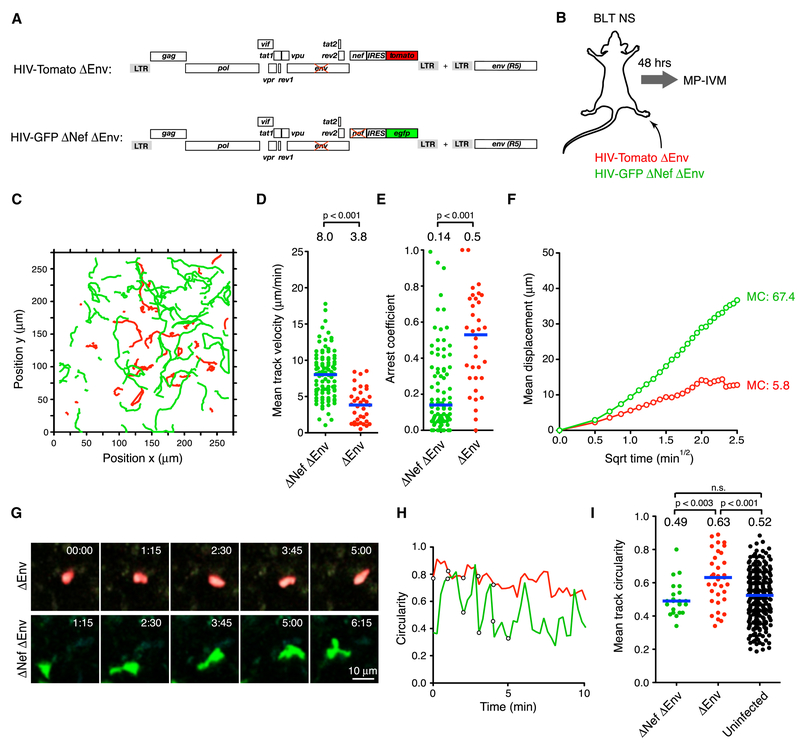

Nef impairs stabilization of cell polarity in HIV-infected T cells

Nef perturbs chemokine receptor function and actin polymerization, and both activities could reduce cell migration speed by disabling stable cell polarization. Indeed, HIV Nef reduces polarization of mouse T cells migrating on endothelial monolayers in vitro (Stolp et al., 2012). We therefore wanted to determine if Nef also impairs polarization of HIV-infected human T cells in vivo. However, Env-dependent tethering and formation of syncytia (Fig. 1C and (Murooka et al., 2012)) precluded reliable measurements of cell shape changes driven by Nef. We therefore co-infected mice with env-deleted reporter viruses that expressed nef (HIV-GFP ΔEnv) or not (HIV-Tomato ΔEnv ΔNef) (Fig. 3A, B). Similar to our env-expressing virus, nef-deletion restored migration speed and displacement of cells infected with env-deleted virus to values observed in uninfected CD4+ TCM (Fig. 3C-F, Supplementary Movie 3, and Fig. 1D-G). However, as previously described (Law et al., 2016; Murooka et al., 2012), cells infected with env-deleted virus did not exhibit the characteristic elongated shapes of HIV-infected cells. We were thus able to examine the effect of Nef on cell polarity using a 2-D circularity index CI (CI=1 for a perfect circle, CI=0 for a line). Cells infected with nef-expressing virus maintained mostly high CIs, consistent with poor polarization capacity. In contrast, cells infected with nef-deleted virus continuously oscillated between states of low and high polarity while roaming the LN T cell area, resulting in lower mean CIs comparable to those of uninfected cells (Fig. 3G-I and Supplementary Movie 3). The property of HIV Nef to attenuate migration speed of infected cells is therefore linked to the cells’ impaired capacity for stable polarization.

Figure 3: Nef impairs stabilization of cell polarity in HIV-infected T cells.

(A) ORF diagrams of indicated HIV reporter strains. To produce virus capable of one round of infection, a complementary helper plasmid encoding intact env was used for viral packaging.

(B) Experimental protocol

(C) Migratory tracks,

(D) Mean track velocities,

(E) Arrest coefficients and

(F) MD plots of HIV-infected cells. Blue lines and numbers indicate medians. MC = motility coefficient (in ×m × min−1).

(G) MP-IVM time-lapse series of representative T cells infected with env-deficient HIV expressing Nef (red) or not (green). Elapsed time in minutes:seconds.

(H) Circularity index over time for cells shown in (G). Circles correspond to measurements of cells at various time points depicted in (G).

(I) Mean track circularities.

Data are pooled from 6 individual recordings from 2 animals. MC = motility coefficient (in μm × min−1). n.s. = not significant. Blue lines and numbers above graphs indicate medians. n.s. = not significant.

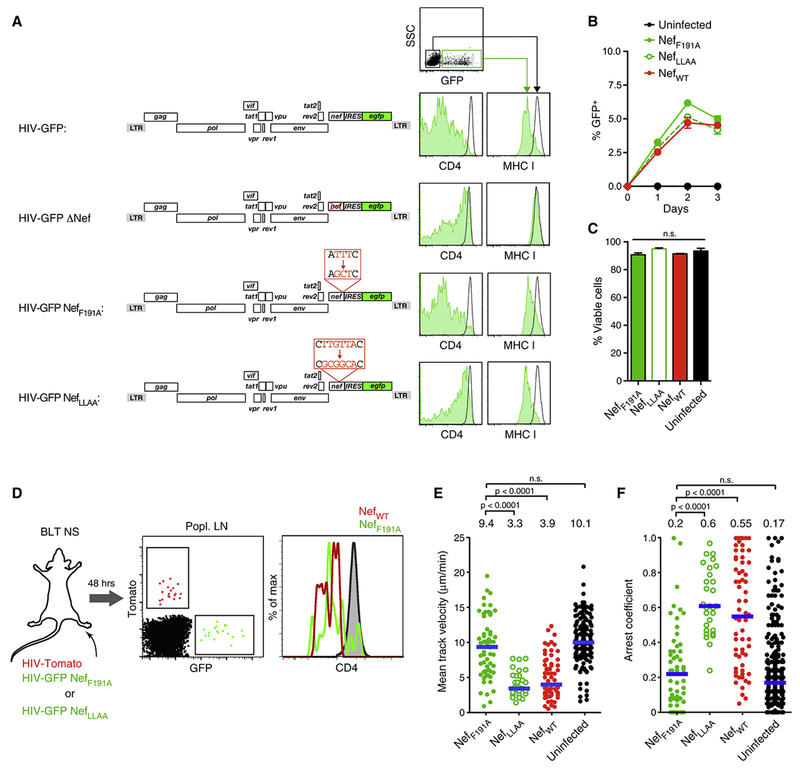

Nef’s effects on cell migration are based on its association with PAK2

Nef uses distinct motifs for downregulation of chemokine receptors and association with active PAK2. The latter requires the formation of an outward-facing hydrophobic patch formed by Nef residues L85, H89, A188, and F191 in clade B strains of HIV-1 (Agopian et al., 2006; O’Neill et al., 2006). Nef-driven and PAK2-dependent actin cytoskeletal dysregulation can be disrupted through the mutation of Nef F191, while leaving chemokine receptor down-regulation and other known functions of Nef intact (O’Neill et al., 2006; Schindler et al., 2007). To specifically test the role of PAK2 association in attenuating cell motility we generated reporter viruses expressing either the F191 alanine mutant of Nef (HIV-GFP NefF191A) or, as a control, a Nef mutant with a disrupted ExxxLL di-leucine motif (E160-L165) required for CD4 down-regulation (HIV-GFP NefLLAA) (Stolp et al., 2009) (Fig. 4A). These mutants exhibited the predicted effects on CD4 and MHC I expression in infected primary human T cells (Fig. 4A), and did not alter in vitro replication or target cell apoptosis as compared to HIV-GFP expressing WT Nef (Fig. 4B, C). However, while HIV-GFP NefLLAA reduced motility of infected T cells in LNs to a similar extent as HIV-Tomato, the F191A mutation was sufficient to restore the motility of infected cells to that of uninfected control T cells, and as observed in complete absence of Nef (Fig. 4D-F and Supplementary Movie 4).

Figure 4: Nef interferes with cell migration by activating PAK2.

(A) Cell surface expression of CD4 and MHC I on uninfected TCM (black histograms) or TCM infected with HIV-GFP encoding either wildtype Nef, ΔNef, NefF191A or NefLLAA (green histograms).

(B) Frequency of infected T cells.

(C) Frequency of viable (Annexin V−) infected cells on day two.

(D) Exp. protocol and CD4 expression by infected cells in draining popLNs 2 days following footpad co-injection of WT and F191A mutant reporter strains. Grey histogram shows uninfected LN CD4+ T cells.

(E) Mean track velocities and

(F) Arrest coefficients of HIV infected T cells. Uninfected TCM recorded in LNs of separate BLT NS mice are shown for reference. Data are pooled from 17 individual recordings from 5 animals. Blue lines and numbers above graphs indicate medians. n.s. = not significant.

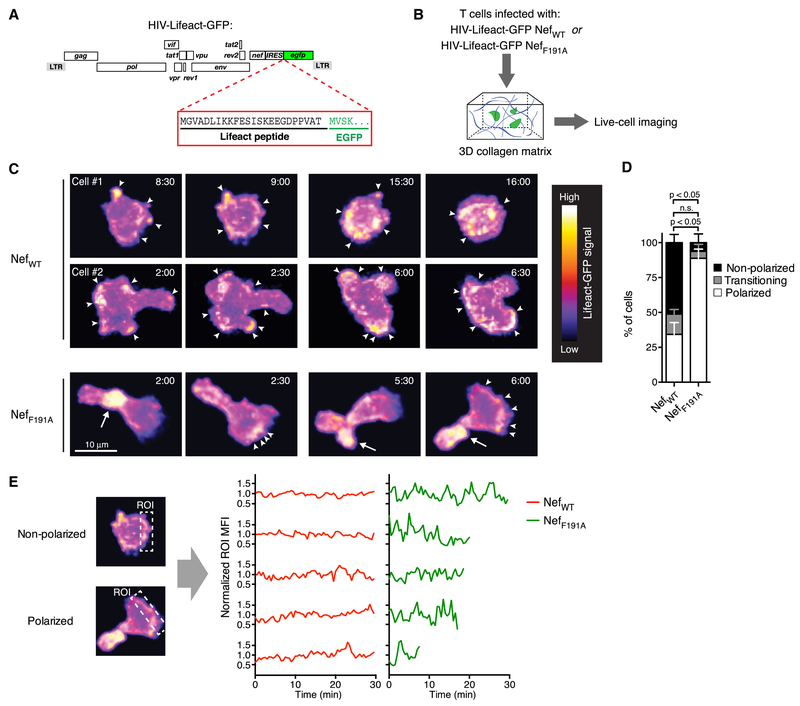

The association of NL4-3 Nef with PAK2 is reportedly less pronounced than for other Nef alleles (Arora et al., 2000; Kirchhoff et al., 2004; Luo and Garcia, 1996; Pulkkinen et al., 2004). We therefore generated HIV NefWT and HIV NefF191A clones expressing Lifeact-GFP (Fig. 5A), a fluorescent reporter that permits visualization of filamentous (F-) actin in live cells (Riedl et al., 2008), in order to test through direct visualization whether the hydrophobic patch of NL4-3 Nef mediates HIV-induced disruption of the actin-cytoskeleton in infected primary T cells. Since the resolution of MP-IVM was not sufficient to reliably resolve discrete F-actin clusters in infected T cells in LNs of BLT mice (data not shown), we resorted to live cell imaging of HIV-infected human T cells in collagen matrices (Fig. 5B) (Stolp et al., 2012). In this 3-dimensional, but acellular environment, NefWT and NefLLAA had similar effects on T cell motility as they had in LNs, while cells infected with HIV expressing NefF191A resembled uninfected CD4+ T cells (Fig. S2). Cells infected with HIV-Lifeact-GFP NefF191A polarized and formed dense and stable F-actin clusters in their uropods, while clusters at the leading edge were more dynamic and formed in a cyclical fashion, (Fig. 5C-E and Supplemental Movie 5), as expected for lamellipodium formation in migrating uninfected T cells. Most cells infected with HIV-Lifeact-GFP NefWT, on the other hand, did not stably polarize, and formed disorganized F-actin clusters around their entire perimeter with no clear directional preference. Even in those cells that partially polarized and migrated, F-actin formation rarely followed the cyclical spatiotemporal patterns observed for cells infected with HIV-Lifeact-GFP NefWT (Fig. 5C, D and Supplemental Movie 5). Hence, the hydrophobic patch that enables association with active PAK2 appears to be solely or predominantly responsible for the pronounced impact of NL4-3 Nef on regulated actin cytoskeletal function and migratory behavior of HIV-infected T cells in LNs, while effects of Nef on other molecules implicated in cell motility are likely to be more subtle or absent, or may only be apparent in different tissue contexts.

Figure 5: The NL4-3 Nef hydrophobic patch perturbs actin cytoskeletal function in migrating HIV-infected T cells.

(A) ORF diagram of HIV-Lifeact-GFP.

(B) Experimental protocol.

(C) Time-lapse series (2 pairs of consecutive frames/cell) of TCM infected with HIV-Lifeact-GFP expressing NefWT (top two rows) or NefF191A (bottom row). Fluorescence intensity is represented using a heat map look-up table. Elapsed time in minutes:seconds. Arrowheads indicate small peripheral F-actin clusters. Arrows indicate large F-actin clusters predominantly observed in the uropod of polarized cells.

(D) Fractions of cells forming lamellipodia (‘polarized’) or not (‘non-polarized’), and of cells ‘transitioning’ between these states, of a total of 43 (NefWT) and 21 (NefF191A) cell traces from 3 independent experiments. Mean ± SEM.

(E) Rectangular ROIs were used to longitudinally measure MFIs at randomly chosen sites in non-polarized cells (repositioned for each time-point to capture the same aspect of the cell) and at the leading edge of polarized cells (repositioned for each time-point perpendicular to the direction of movement). MFIs were normalized to a value of ‘1’ for individual cells and plotted over time for 5 representative cells from each group to compare the fluctuations of F-actin polymerization in infected T cells expressing NefWT or NefF191A.

Actin-cytoskeletal disruption by Nef impairs early systemic viral spread upon genital mucosal transmission

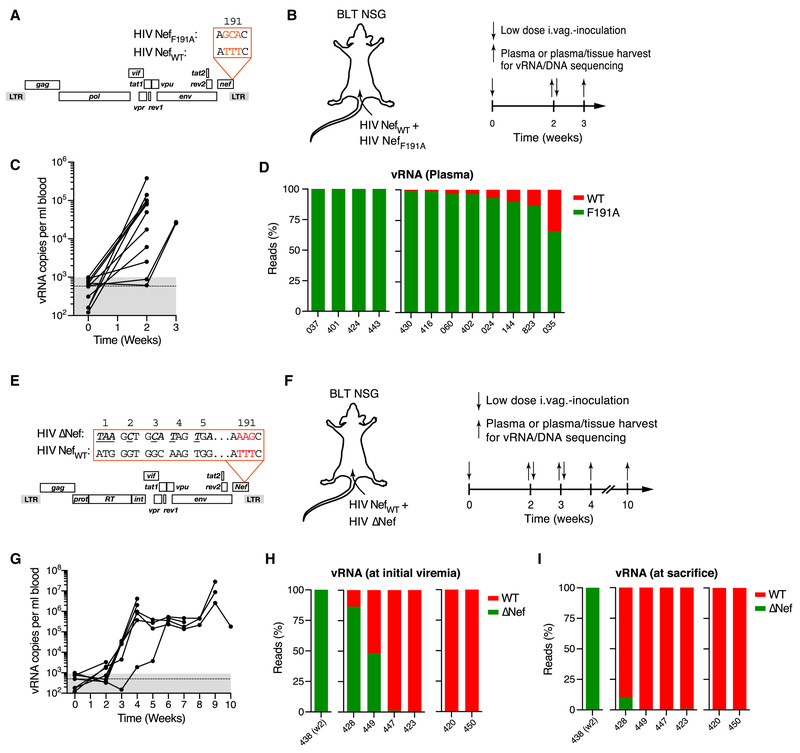

Association with the kinase PAK2 in host cells is a highly conserved property not only of HIV-1 Nef, but also of other lentiviral Nef proteins (Kirchhoff et al., 2004; Sawai et al., 1996). Furthermore, other human retroviruses (Chan et al., 2013), as well as broad range of unrelated virus families, including for instance alpha herpesvirus and poxvirus (Mercer and Helenius, 2008; Van den Broeke et al., 2009), also control the activity of PAK2 and other p21-activated kinases, underscoring the general significance of this function for viral pathogenesis. It remains unclear, however, in which way this function benefits HIV-1 in vivo. To examine how the Nef hydrophobic patch that enables PAK2 association affects viral fitness during female genital transmission and initial spread to distant lymphoid tissues in humanized mice, we generated two non-fluorescent CCR5-tropic NL4-3 viral clones that differed only in residue F191 of Nef and used these for repeated low dose intravaginal co-inoculations at a 50:50 ratio in 12 NOD-scid common γ-chain−/− (NSG) BLT humanized mice (Fig. 6A, B). We reasoned that if an intact Nef hydrophobic patch or lack thereof conferred a significant fitness advantage in this competitive setting, we would be able to retrieve predominantly one or the other virus in plasma and tissues once viremia ensues. To prevent possible reversion of mutant nef 191A to wildtype nef 191F in vivo, we chose a triple nucleotide mutation (TTT for F191 into GCA for A191), full reversion of which we deemed to be unlikely over the time-course of the experiment (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6: Actin cytoskeletal disruption restrains initial viral dissemination.

(A) ORF diagrams of HIV NefWT and HIV NefF191A.

(B) 104 IUs each of each clone were intravaginally co-inoculated into BLT NSG mice at 50:50 ratio (based on I.U.). Plasma viremia was measured at week two, followed the next day by tissue harvest or, in non-viremic animals, repeat intravaginal inoculation and tissue harvest at week three.

(C) Plasma viremia. Dashed line and grey-shaded area indicate mean and range of background signals in three uninfected control animals.

(D) Ratio of nefWT (red) or nefF191A (green) NGS reads (~2 × 104 total reads/sample) from plasma vRNA obtained at the time of initial viremia. Numbers indicate individual animals. HIV nefWT vRNA was undetectable at any time in plasma or any tissue analyzed in the four animals grouped on the left.

(E) ORF diagrams of HIV NefWT and HIV ΔNef.

(F) 104 IUs each of HIV NefWT and HIV ΔNef were intravaginally inoculated into BLT NSG mice at 50:50 ratio (based on I.U.). Plasma viremia was measured weekly starting at week 2. Non-viremic animals received repeat intravaginal inoculations the next day.

(G) Plasma viremia. Dotted line and grey-shaded area indicate mean and range of background signals.

(H, I) Ratio of NGS reads (~2 × 104 total reads/sample) for nefWT (red) or Δnef (green) from plasma vRNA obtained at the time of initial viremia (H) or at the time of sacrifice (I). Numbers indicate individual animals. Either nefWT or Δnef vRNA were undetectable in any samples in the animals grouped on the left (n=1) or on the right (n=2), respectively.

All 12 animals developed plasma viremia within 2 to 3 weeks of their first challenge. At this point their female reproductive tract (FRT) tissue and distant LNs (dLNs; Note: draining iliac LNs can rarely be identified in NSG BLT mice) were harvested (Fig. 6C) and nef was amplified from plasma and tissue viral RNA (vRNA) for analysis by next generation sequencing (NGS). Unexpectedly, HIV NefF191A sequence dominated during this early phase of infection. We detected exclusively mutant nef sequence in 4 out of 12 animals, and a mixture of mutant and WT nef in the remaining 8 animals, with the fraction of F191A sequence ranging from 65 to 99% (Fig. 6D). Similar distributions were found for both vRNA and viral DNA in FRT and dLNs, with a slightly larger, but still minor proportion of WT vRNA in the FRT (the initial site of viral replication), compared to plasma and dLNs (Fig. S3A, B and Fig. S3). This pattern is consistent with co-transmission of both clones, followed by accelerated spread of mutant HIV-1 compared to WT HIV-1 over the course of systemic viral dissemination based on an unexpected initial fitness advantage through a disrupted Nef hydrophobic patch in vivo. The four exclusive infections with HIV NefF191A may reflect co-transmission of both clones followed by complete disappearance of WT virus by the time of initial viremia or, alternatively, a bias in favor of HIV NefF191A during single clonal transmission events that may occur in our low-dose inoculation model.

To test if the viral fitness benefit through disruption of the Nef hydrophobic patch could be replicated in vitro, we assessed replication of HIV-1 NefWT or HIV NefF191A in a competitive setting in resting TCM (Fig. S4), but did not observe changes in the ratio of WT and mutant nef sequence over the course of 5 weeks (Fig. S4B, C). Thus, selection pressures only encountered in vivo render HIV expressing intact Nef capable of actin cytoskeletal perturbation less fit early after female genital transmission compared to mutant virus lacking this capability.

Given that deletion of nef strongly diminishes viral fitness in vivo in both HIV-1 infection of humans and SIVmac239 infection of rhesus macaques (Kestler et al., 1991; Kirchhoff et al., 1995), a fitness benefit through selective disruption of the Nef hydrophobic patch was surprising. We therefore also co-infected animals with NL4-3 expressing NefWT together with NL4-3 that did not express the entire nef gene and in addition was engineered to carry the mutant AAG sequence in codon position 191 of the (unexpressed) nef open reading frame in order to distinguish from NefWT (TTT in position 191) by NGS (‘HIV δNef’) (Fig. 6E, F). Here we observed clear dominance of NefWT sequence in plasma vRNA at initial viremia, which became even more pronounced by the time the animals were sacrificed for harvest of FRT tissue and dLNs, where the same pattern was observed (Fig. 6G-I and Fig. S3C, D). Apparent exclusive clonal infections were also biased in favor of NefWT-expressing virus. Hence, our co-infection model replicates the well-established fitness deficit of nef-deleted lentiviruses, which contrasts with an early benefit of Nef hydrophobic patch disruption.

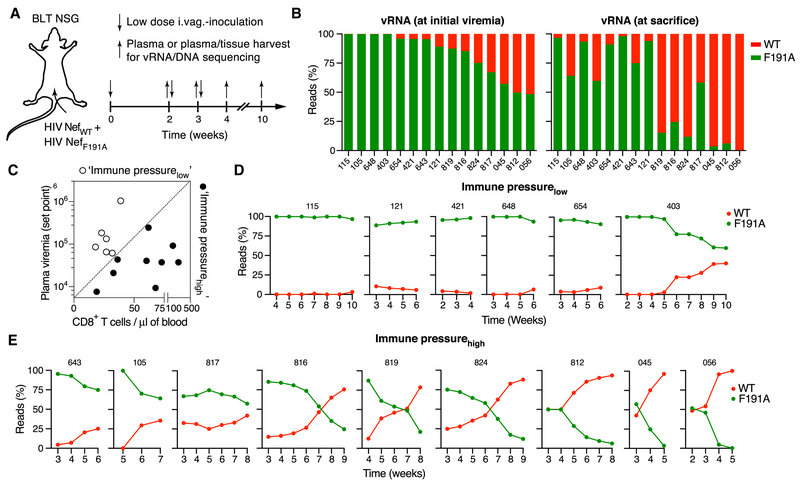

The Nef hydrophobic patch optimizes viral persistence in vivo

To test whether the initial dominance of HIV lacking the ability to dysregulate the actin cytoskeleton was sustained, we repeatedly co-inoculated an additional 36 female animals from 4 different batches of BLT NSG humanized mice with HIV NefWT and HIV NefF191A intravaginally and collected plasma weekly until viremia became detectable (between week 2 and 5, Fig. 7A and Fig. S5A). At this point, exclusively nefF191A vRNA sequence was detected by NGS in 18 animals, in contrast to only 3 animals with exclusively nefWT sequence (Fig. S5B). In the remaining 15 animals a mixture of both sequences was found (also considering analysis from later time-points), but with clear dominance of HIV nefF191A at the onset of viremia (Fig. 7B). Weekly plasma collection was continued in all animals until their sacrifice for tissue collection at varying time-points up to week 10 week. This revealed that with time, nefWT sequence again became detectable in some animals in which it was previously undetectable, and started to dominate plasma viremia in animals where it had previously represented the smaller share of detected sequence (Fig. 7B and Fig. S5C). Both vRNA and vDNA in tissue largely mirrored observations in plasma (Fig. S6A-D). This variable reversion of dominance from HIV nefF191A to HIV nefWT suggested a secondary selection pressure that now favored outgrowth of the previously less fit WT virus. Because immune reconstitution of BLT humanized is variable, and also because the varying HLA alleles expressed by the human hematopoietic graft can provide variable levels of protection against HIV, we considered that anti-HIV immune pressure may be variable between animals from different batches of mice and between individual animals (Dudek et al., 2012). We therefore correlated the frequency of human CD8+ T cells in blood prior to infection as a measure of immune reconstitution and the plasma viremic setpoint as an inverse measure of CTL-mediated immune pressure (Ndhlovu et al., 2015), and set an arbitrary threshold to retrospectively stratify animals with mixed infections as either ‘immune pressurelow’ (low CD8+ T cell count/high viremic setpoint) or ‘immune pressurehigh’ (high CD8+ T cell count/low viremic setpoint) (Fig. 7C). When we then examined the fractions of nefWT and nefF191A NGS reads in plasma over time, we observed no or only a weak trend towards recovery of nefWT in immune pressurelow mice (Fig. 7D). In contrast, we saw a strong trend toward nefWT recovery in all immune pressurehigh mice, with WT virus becoming dominant in 6 out of 9 animals over the 5- to 9-week observation period following initial viral inoculation (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7: The Nef hydrophobic patch supports viral persistence.

(A) 104 IUs each of HIV NefWT and HIV NefF191A were repeatedly intravaginally inoculated into BLT NSG mice at 50:50 ratio (based on I.U.). Animals were sacrificed at different time-points in order to compare vRNA and vDNA from plasma and tissue.

(B) Ratio of nefWT (red) or nefF191A (green) NGS reads (~2 × 104 total reads/sample) from plasma vRNA obtained at the time of initial viremia (left) or of sacrifice (right) for animals with mixed infections. Numbers indicate individual animals. For data on single infections, see Fig. S5.

(C) Correlation of human CD8+ T cell counts in blood prior to infection and viremic set points (median vRNA level following peak viremia) in individual animals. An arbitrary cut-off (dashed line) was used to classify animals as immune pressurelow (open symbols) or immune-pressurehigh (closed symbols).

(D, E) Dynamics of HIV NefWT and HIV NefF191A vRNA (as percentage of total vRNA) in plasma, based on NGS analysis (~2 × 104 total reads/sample), for immune-pressurelow (D) and immune pressurehigh (E) animals, as classified in (C). Numbers indicate individual animals.

While both primary fitness disadvantage and secondary fitness benefit of the Nef hydrophobic patch were thus evident in a competitive setting of co-infection, we wondered how pronounced these effects are in non-competitive settings. We therefore examined plasma viremia in 15 animals where exclusively nefWT or nefF191A sequence was observed at any timepoint and in any tissue, and which we therefore considered as singly infected with either one or the other clone. Even in this non-competitive setting, mice infected with HIV expressing NefWT developed viremia later than those infected with HIV NefF191A, but while peak viremia was comparable, they subsequently demonstrated higher viral setpoints (Fig. S6E-G). Hence, an intact hydrophobic patch that enables Nef to associate with active PAK2, perturb the actin cytoskeleton, and thereby inhibit the motility of HV-infected T cells, initially restrains viral systemic dissemination. Subsequently, however, coinciding with rising CTL-mediated immune pressure in BLT humanized mice (Dudek et al., 2012), it provides a secondary fitness benefit in immune-competent animals.

DISCUSSION

The lentiviral protein Nef is a major driver of the development of AIDS in HIV-1 infection, but how its various functions in infected, and potentially in uninfected bystander cells contribute to this outcome in vivo remains poorly understood. Here we used intravital microscopy in LNs of BLT humanized mice to demonstrate that perturbation of regulated actin polymerization, dependent on the ability of Nef to associate with an active pool of the host cell kinase PAK2, is the primary determinant of altered migratory behavior of infected T cells in LNs, while other functions of Nef, as well as CCR7-downregulation by Vpu, play at most subordinate roles. Through competitive co-infection with molecular clones of HIV-1 and NGS analyses we found that, consistent with a role for infected T cells as migratory viral vehicles in systemic viral dissemination, Nef-mediated disruption of actin-cytoskeletal function initially restricted viral replication in vivo. However, following the initial phase of spread and temporally coinciding with rising immune pressure through the anti-HIV cytotoxic T cell response (Dudek et al., 2012), the hydrophobic patch of Nef that enables association with PAK2 imparts significantly greater fitness to the virus, revealing a previously unrecognized benefit of this conserved function of lentiviral Nef proteins in vivo.

It is surprising that a highly conserved viral feature such as the Nef hydrophobic patch restricts viral transmission and dissemination, even if only transiently, as observed here during the first few weeks following female genital transmission. The fact that the virus tolerates this fitness penalty indicates that the underlying molecular activity of Nef has a critical benefit in a different context, as is reflected by the secondary rebound of virus expressing intact Nef. Prior work on macaque infection with SIVmac239 supports this conclusion by showing a trend towards genetic reversion of nef mutations that disable its association with active PAK2. Two studies demonstrated restoration of PAK2 association between 2 and 8 weeks post infection, preceding – and presumably enabling – high level viremia (Khan et al., 1998; Sawai et al., 1996). A third study observed reversion between 12 and 20 weeks, and no correlation to viremic levels (Carl et al., 2000). Irrespective of functional relevance, the kinetics of genetic reversion in these studies match the secondary rebound of HIV expressing NefWT during co-infection with NefF191A-expressing HIV in BLT humanized mice. This comparison may however be confounded by the fact that the mutations disabling PAK2 association of SIV Nef in the macaque studies (the RRLL mutation of the di-arginine motif and the AxxA mutation of the polyproline motif) likely disrupt additional functions of Nef, although these other functions are not as well characterized for SIV Nef as they are for HIV Nef.

Our findings on the fitness defect of nef-deleted HIV in the BLT humanized mouse model both early and late after infection are entirely consistent with observations in humans (Kirchhoff et al., 1995), macaques (Kestler et al., 1991), and prior humanized mouse studies (Watkins et al., 2015). However, the competitive co-infection setting with WT HIV may accentuate the fitness defect resulting from nef deletion. Co-infection may therefore serve as a sensitive experimental approach to reveal fitness phenotypes that are less apparent in single clonal infections.

Why do lentiviruses disrupt the actin cytoskeleton? It has been speculated that the resulting slower migration speeds of infected cells could prolong their contacts with uninfected cells, thus promoting the formation of virological and infectious synapses and amplifying the rate of viral spread in tissues (Fackler et al., 2014). Contradicting this hypothesis, we found that disrupting the hydrophobic patch that enables Nef association with active PAK2, and thereby restoring the migratory speed of infected cells to that of uninfected cells boosts initial viral spread. This accelerated spread concomitant with enhanced cell motility is in agreement with a model by which trafficking of infected T cells within and between tissues provides for the most effective means of viral dissemination (Deruaz et al., 2017; Murooka et al., 2012). Our results also suggest that Nef-PAK2 association and actin cytoskeletal perturbation do not primarily serve the purpose of reducing T cell motility to prolong cell contacts and enable enhanced formation of virological and infectious synapses, since the resulting improvement of cell-to-cell transmission would be predicted to accelerate viral dissemination, while we observed a deceleration.

The actin cytoskeleton facilitates the cellular entry of HIV particles (Liu et al., 2009), and modulation of its activity via Nef-mediated inhibition of cofilin (Stolp et al., 2009) or through PAK2-dependent association with the exocyst complex (Imle et al., 2015; Mukerji et al., 2012) could either promote entry during initial cellular infection, or subsequently inhibit it to minimize super-infection, similar to what down-regulation of CD4 and the HIV co-receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 is thought to achieve (Michel et al., 2005; Venzke et al., 2006). Effects on viral entry would require either highly localized activity of the small quantities of Nef protein contained in entering viral particles, or trans-effects of Nef released from infected cells on uninfected cells. Nef protein can be detected in extracellular fluids, indicating that it can be released in large quantities from infected cells (Fujii et al., 1996). It is therefore conceivable that cell-free Nef primes uninfected T cells for productive infection by rendering them more receptive for viral core entry through PAK2-dependent changes to cortical actin structure. However, in our prior studies, we did not observe changes to the motility of uninfected T cells in direct vicinity of infected cells, which argues against pronounced trans-effects of Nef (Murooka et al., 2012). More importantly, such a trans-mechanism would not explain the secondary fitness benefit of the Nef hydrophobic patch we observed, since in a mixed infection extracellular WT Nef would prime target cells for entry of both NefWT- or NefF191A-expressing virus.

It should be noted that the Nef hydrophobic patch may have additional, less well characterized or even unknown functions other than association with PAK2 and actin-cytoskeletal perturbation, and that these functions may contribute to the fitness phenotypes we observed upon its disruption. One study from the Gabuzda group noted that constellations of hydrophobic Nef residues that facilitate its association with active PAK2 can enhance HIV-1 replication in T cells in vitro, but only when these cells are exposed to the virus before cellular activation, and only under suboptimal activation conditions (Olivieri et al., 2011). While we did not observe differences in viral replication in resting central memory-like T cells over the course of several weeks, it is possible that our culture conditions did not produce a T cell activation state where this fitness benefit is revealed. Likewise, it is possible that early HIV replication in BLT humanized mice does not depend on target cells with the particular resting state described in the Gabuzda study, potentially concealing a positive effect on replication. Further studies will need to address this.

The lack of either a positive or negative effect of the Nef hydrophobic patch on viral fitness in in vitro indicates that environmental conditions only found in the intact organism create the selective pressures that this function has evolved to withstand. Part of the in vivo conditions promoting secondary rebound of HIV expressing intact Nef could be the immune pressure mounted through coordinated T cell, antibody, and NK cell responses. In our observations, virus with an intact Nef hydrophobic patch became dominant between 3 and 7 weeks after initial exposure. These kinetics align with CTL responses in BLT humanized mice, documented through CTL escape mutations, and with CTL responses in HIV-infected humans (Dudek et al., 2012; Koup et al., 1994), implying a possible causal relationship. The fact that a secondary rebound of HIV expressing WT Nef occurred primarily in animals with the most robust immune reconstitution, which developed the lowest viremic setpoints, further supports a role for immune pressure in selecting for an intact Nef hydrophobic patch.

Interestingly, while association with active PAK2 is overall highly conserved among lentiviruses and among HIV strains in the human population, it is often lost in viruses isolated from patients at late stages of infection, when antiviral immune function is reduced (Agopian et al., 2007; Kirchhoff et al., 1999). Also, analysis of nef sequences obtained from untreated chronic progressor (n=45) (Mwimanzi et al., 2013) and elite controller patients (n=406) (Meribe et al., 2015) revealed polymorphisms in position F191 of nef in 37% of patients in the progressor, but in 0% of patients in the controller group (Dr. Takamasa Ueno, personal communication). Therefore, mutations underlying loss of PAK2 association are less likely to result from immune escape, but may rather reflect a relaxed requirement to maintain this function under conditions of waning immune pressure. How perturbation of actin-cytoskeletal function would increase resistance to CTL-mediated or other immune pressure is currently unclear, but since perforin-driven cytotoxicity depends on force-generation across the immunological synapse to produce target cell membrane pores (Basu et al., 2016) as well as on endocytosis and membrane repair processes requiring the target cell actin-cytoskeleton (Thiery et al., 2011), increased resistance to cytotoxic killing could be one mechanism.

Stolp et al have suggested that by impairing the migration of HIV-infected T cells in LNs, Nef may undermine humoral anti-HIV responses (Stolp et al., 2009). However, while antibodies are known to exert immune pressure on HIV in early infection, it is not immediately obvious how, in a mixed infection, humoral immune factors would discriminate between infected cells expressing PAK2 association-defective Nef and the virions they release, and cells and virions that express WT Nef to create the competitive advantage we observed for the latter. Similarly, while delayed viral replication might allow the virus to avoid activation of more effective innate and eventually adaptive immune responses, this alone could not explain the secondary competitive advantage of expressing intact Nef proteins that we observed in mixed infections, since both WT and mutant strains would be equally exposed to the enhanced immune response. It therefore appears more likely that Nef, through its hydrophobic patch, may render infected cells intrinsically more resistant to cell contact-dependent immune effector mechanisms, complementing down-regulation of MHC-I.

Apart from disrupting cell motility and enhancing immune resistance, lentiviral Nef proteins appear to tune the level of T cell activation by down-regulating a variety of immunologically relevant cell surface proteins, while at the same time interfering with different immune signaling pathways (Abraham and Fackler, 2012). This may allow the virus to sustain controlled, but long-term viral gene expression by promoting a suitable host cell activation state that avoids unfavorable bursts of cellular activation through cell-extrinsic stimuli, such as TCR-signals, which may enhance viral antigen presentation and shorten T cell lifespan. Since signaling through many cell surface receptors, including the TCR, depends on cortical actin function (Jaqaman and Grinstein, 2012), Nef-mediated actin-cytoskeletal perturbation could be part of this strategy to generate a stable cellular environment for long-lasting viral replication in vivo, where activating antigen and cytokine signals constantly jeopardize the function of infected T cells as long-lived vehicles for viral dissemination, persistence, and replication.

In conclusion, our findings define perturbation of actin-cytoskeletal regulation via the Nef hydrophobic patch that mediates association with the kinase PAK2 as the primary mechanism by which HIV-1 attenuates the motility of infected T cells in lymphoid tissue. However, while disrupting chemotactic actin turnover initially restrains systemic viral dissemination, presumably by restricting the trafficking of infected T cells, the intact hydrophobic patch is subsequently needed to sustain high-level viremia. It will be of interest to further define the selection pressures that drive conservation of this so far enigmatic viral function in vivo, since its inhibition could enhance viral immune vulnerability in ways that synergizes with other antiviral treatment strategies such as vaccination or broadly neutralizing antibody therapy.

STAR* METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Thorsten Mempel (tmempel@mgh.harvard.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Humanized mice

Female NOD-scid (NS) and NOD-scid × IL-2 receptor γ-chain−/− (NSG) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and housed in specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions at MGH. Both strains were used for the production of Bone marrow Liver Thymus (BLT) NS and BLT NSG humanized mice, respectively, as described below. Fetal tissue from single donors was used to generate batches 30-60 BLT mice/donor. Animals were housed in groups of 4-5 mice per cage during the reconstitution period. Both male and female mice with sufficient reconstitution based on our established criteria (Murooka et al., 2012) were randomly assigned into separate experimental groups, where they were either mock- or HIV-infected. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations implemented by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Cells

MAGI.CCR5 cells were obtained from the NIH ARRRP (Cat. #3522) and grown in DMEM 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate and 10mM HEPES (Mediatech) under 37°C/5% CO2 conditions. MAGI cells are derived from a clone of the female human HeLa cell line. This cell line has not been authenticated.

TZM-bl cells were obtained from the NIH ARRRP (Cat. #8129) and grown in DMEM 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate and 10mM HEPES (Mediatech) under 37°C/5% CO2 conditions. TZM-bl cells are derived from a clone of the female human HeLa cell line. This cell line has not been authenticated.

HEK 293T Cells were obtained from ATCC and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate and 10mM HEPES (Mediatech) under 37°C/5% CO2 conditions.

De-identified PBMC samples were obtained with informed consent from buffy coats of healthy blood donors at Massachusetts General Hospital according to IRB approved protocols.

Viral Constructs and Preparation of Viral Stocks

The proviral plasmid pBR-NL43-IRES-EGFP-nef+ (pIeG-nef+) (Schindler et al., 2003) was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program (Cat. #11349). The V3 loop of env was modified to resemble that of HIV BaL and confer R5-tropism and the resulting derivative was designated as ‘HIV-GFP’ (Murooka et al., 2012). The egfp gene was replaced with dTomato (Shaner et al., 2004) using restriction enzyme sites NcoI and XmaI to generate the ‘HIV-Tomato’ construct. To generate a nef-deleted strain, HIV-GFP was digested with MluI and XhoI, and re-ligated using T4 DNA polymerase and quick ligase (NEB #E0542L). The resulting deletion produces a premature STOP codon downstream of the nef start site, preventing expression of a functional Nef protein (designated ‘HIV-GFPΔNef’). To generate the HIV-GFP NefF191A mutant, the Q5 Site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB #E0554) was used according to manufacturer’s protocols with primers 5’- CAGCCGCCTAGCAGCTCATCACGTGGCCCG -3’ and 5’- CGGGCCACGTGATGAGCTGCTAGGCGGCTG -3’. To generate the HIV-GFP NefLLAA mutant, mutagenic primers 5’- GGAGAGAACACCAGCGCGGCACACCCTGTGAGCCTGC -3’ and 5’- GCAGGCTCACAGGGTGTGCCGCGCTGGTGTTCTCTCC -3’ were used. To generate a vpu-deleted strain, the start codon of vpu (ATG) was mutagenized into a stop codon (TAG) using QuikChange lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) with primers 5’- GCAGTAAGTAGTACATGTATAGCAACCTATAATAGTAG CAATAGTAGCATTAGTAGTAGC-3’ and 5’-GCTACTACTAATGCTACTATTGCTA CTATTATAGGTTGCTATACATGTACTACTTACTGC-3’. The env-deleted HIV plasmids were constructed by digesting the HIV-GFP plasmid with PsiI to generate a frameshift mutation, as described previously (Murooka et al., 2012). To generate the F191A mutation in nef of the parental HIV-1 NL43 R5-tropic strain, the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB #E0554) and mutagenesis primers 5’-CCGCCTAGCAGCACATCACGTGG-3’ and 5’-CTGTCAAACCTCCACTCTAAC-3’ were used. To generate the nef deletion in the parental HIV-1 NL43 R5-tropic strain, the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB #E0554) and mutagenesis primers 5’- ATAGTGATCAAAAAGTAGTGTGATTGG -3’ and 5’- GCAGCTTACTTATAGCAAAATCCTTTCC -3’ and mutagenesis primers 5’-CCGCCTAGCAAAGCATCACGTGG-3’ and 5’-CTGTCAAACCTCCACTCTAAC-3’ to introduce the codon AAG tag at the F191 position of the mutagenized plasmid. To generate the HIV Lifeact-GFP reporter clones, the oligonucleotides 5’- CCATGGGTGTCGCAGATTTGATCAAGAAATTCGAAAGCATCTCAAAGGAAGAAGGGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACCATGG -3’ and 5’- CCATGGGTGTCGCAGATTTGATCAAGAAATTCGAAAGCATCTCAAAGGAAGAAGGGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACCATGG -3’ were synthesized, annealed and cloned upstream of the EGFP gene using restriction enzyme Ncol (Riedl et al., 2008).

All constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing on both DNA strands.

All HIV proviral constructs used in this manuscript were propagated in XL-10 Gold Ultracompetent Cells and grown at 37°C in a shaking incubator for 18 hours. Plasmids were purified using a commercial kit (Qiagen) and DNA content quantified by spectrophotometry. Plasmid stocks were stored at −80°C. Thawed tissues were homogenized using the gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) to extract total RNA and DNA using AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen).

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of BLT NS and NSG Humanized Mice

Female NS or NSG mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and reconstituted at age 6-8 weeks with human immune systems as previously described (Murooka et al., 2012).

Anonymized fetal tissues (17 to 19 weeks of gestational age) were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources and contained no information regarding donor gender, race and health status. Mice were conditioned with sublethal (2 Gy) whole-body irradiation and microsurgically transplanted with 1 mm3 fragments of human fetal thymus and liver under the kidney capsule. CD34+ cells isolated from human fetal liver using anti-CD34 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) were injected intravenously (1 - 5 × 105 cells/mouse) within 6 hours of surgery to create “BLT” (Bone marrow, Liver and Thymus) mice. Mice were monitored for human hematopoietic reconstitution at 14 and 18 weeks post-transplantation. High lymphoid reconstitution of BLT NS mice in peripheral blood (>25% lymphocytes in PBMC, >50% human lymphocytes, >40% T cells among lymphocytes) correlated with optimal LN reconstitution and rendered mice suitable for intravital imaging (typically at 18-20 weeks after surgery). BLT NS mice were used for all MP-IVM studies (due to robust repopulation of popLNs), and BLT NSG mice were used for long-term infection studies.

Preparation of viral stocks

All HIV-1 stocks were produced by transient transfection of HEK 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Viral supernatants were collected 48 hours after transfection, clarified through a 0.22 ϋm filter and centrifuged at 90,000 × g for 2 hours using an SW32Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) over a 20% sucrose cushion. Viral stocks were titrated on MAGI.CCR5 or TZM-bl cells indicator cells and blue focus units (bfu) counted to determine infectious units (IUs)/ml. To produce HIV AEnv virions capable of one round of infection, a complementary LTR-driven plasmid encoding an exogenous intact BaL Env (pSVIIIexE7-BaL) was used for co-transfection of HEK 293T cells, as previously described (Murooka et al., 2012).

Generation and infection of TCM from BLT humanized mice

Human CD4+ central memory-like T cell (TCM) were generated as described previously (Murooka et al., 2012). Briefly, CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and LNs of BLT mice by positive immuno-magnetic selection using CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) to purities consistently above 95%. Cells were activated by adding Dynabeads coated with anti-human CD3ε/CD28 antibody (3:1 bead:cell ratio, Life Technologies) for 2 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (Atlanta Biologicals), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate and 10mM HEPES (Mediatech). After 2 days, microbeads were removed and cells were cultured for another 6-8 days in medium containing 50 IU/ml human rIL-2 (R&D Systems), keeping cell density close to 5 × 105 cells/ml. Cells were used for all experiments between days 8 and 10. TCM were infected with HIV (HIV-GFP, HIV-GFPΔNef, HIV-GFP NefF191A and HIV-GFP NefLLAA) by incubating 3 × 106 T cells with virus at an MOI of 0.1-0.5 (final volume of 200 μL) in 8μg/ml polybrene. After 4 hours, 3ml of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with hrIL-2 was added. GFP expression was measured by flow cytometry to determine the rate of infection at the specified times. To perform MP-IVM of uninfected TCM populations in an uninfected BLT LN, T cells were stained with 10nM of CMTMR (CelltrackerOrange, Thermo Fisher) prior to adoptive transfer by footpad injection. MP-IVM was performed 18-20 hours after injection.

Co-culture of WT and HIV NefF191A-infected TCM generated from human PBMC

Resting human CD4+ TCM were generated as described above, but using CD4+ T cells isolated from blood derived from healthy human donors using the RosetteSep Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies). At day 8 of TCM culture, aliquots of 105 cells in 0.5 ml medium with 4 μg/ml polybrene were spin-infected in 24 well plates at 2000 × g for 2 hours at 37°C with either non-fluorescent WT HIV or HIV NefF191A at an MOI of 0.5. Cells were washed and resuspended in fresh medium containing human rIL-2, and cultured for 2 days. To determine the fraction of infected cells in each aliquot, cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti p24 antibody (clone KC-57-RD, Beckman Coulter), and analyzed by flow cytometry. 50:50 ratio co-cultures of WT and HIV NefF191A infected cells were established by mixing aliquots to infected cells to produce samples of 105 cells/0.5 ml containing equal numbers of WT and HIV NefF191A-infected cells. These mixtures were then continually cultured for 5 weeks in medium containing 50 IU/ml human rIL-2. To compensate for cell loss due to cell death and provide fresh target cells, 104 uninfected cells from the same initial TCM culture were added to each co-culture on a weekly basis. Virus supernatants were collected 6 hours after initial cell mixing and then weekly, clarified by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, and stored at −80°C for subsequent vRNA isolation, nef PCR, and Sanger sequencing. Sequencing chromatograms were analyzed by ImageJ to calculate the area under the curve for each base pair and were used to determine the relative abundance of each viral strain.

Tetherin downmodulation by Vpu

To confirm functional Vpu expression by NL4-3-based HIV-Tomato reporter virus, HEK 293T cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected with 3 μg of either HIV-Tomato or ΔVpu HIV-GFP proviral construct and different concentrations of human tetherin expression plasmid (Sauter et al., 2009) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 2 days post-transfection, viral supernatants were harvested to infect TZM-bl cells. Infection of TZM-bl cells was quantified 2 days later measuring β-galactosidase activity using the Gal-Screen assay kit (Applied Biosystem, T1027).

To assess Vpu effects on primary human CD4+ T cells, we produced TCM from three different human donors and infected these with ΔVpu HIV-GFP or HIV-GFP through spin-infection, as described above, and collected viral supernatant for RT-qPCR analysis of viral load.

Flow cytometry

T cells were analyzed on an LSRII (Becton Dickinson) using FlowJo software (Tree Star) for analysis. LNs were minced with fine forceps and passed through a 40 μm mesh to obtain single cell suspensions. Cells were washed, counted and stained with a panel of directly conjugated anti-human mAbs: αCD3-PE (HIT3a), αCD4-AF700 (RPA-T4), αCCR7-PE (G043H7), αCD8-APC/Cy7 (RPA-T8), αCD45RA-FITC (HI100) and αHLA-A, B, C-APC (W6/32) (Biolegend). HIV-infected cells were fixed with 2% PFA after staining before analysis.

Footpad HIV infection

To analyze HIV infection in the popLN, BLT mice were injected into the hock of the foot (referred to as ‘footpad’ here) with 5 × 105 – 1.5 × 106 infectious units of various HIV strains. After two days, the draining popLN was imaged in MP-IVM or mice were euthanized and the popLNs removed for flow cytometry analysis.

Repetitive low dose intravaginal HIV infection

BLT NSG mice were subcutaneously injected with 200 μg progesterone (Depo-Provera, Pfizer) to synchronize their estrous cycle. 5-7 days later, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and inoculated intravaginally with 1×104 infectious units each of wildtype and F191A mutant HIV strains (in 10 μl PBS). Control mice were given an intravaginal inoculum of 10 μl PBS. Plasma viremia was monitored weekly by RT-qPCR for gag. Mice that did not show measurable viral loads compared to uninfected controls were inoculated again as described above. Once plasma viremia was observed, or at 10 weeks after infection, mice were euthanized, and plasma, LNs, and FRT were harvested and stored in RNAlater solution (Invitrogen) at 4°C for 24 hours, then transferred to −80°C for long-term storage.

Plasma viral loads

Viral RNA was isolated from 50–100 μl of plasma using the QIAamp viral RNA kit (Qiagen). Quantitative reverse transcription and PCR was performed using HIV-1 gag specific primers 5’-AGTGGGGGGACATCAAGCAGCCATGCAAAT-3’ and 5’-TGCTATGTCACTTCCCCTTGGTTCTCT-3’ using the single step QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) on the Lightcycler 480-II system (Roche). Plasma from uninfected BLT mice was used to determine the background signal, as described previously (Murooka et al., 2012).

Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was performed using the fluorescently-labeled dideoxy-nucleotide chain termination method (BigDye v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, Applied Biosystems) at the CCIB DNA Core Facility at Massachusetts General Hospital.

RNA Seq analysis of nef amplicons / Deep sequencing of nef amplicons

For deep sequencing of viral RNA, cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification was performed using the SuperScript III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum Taq High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher) with primers 5’-GTAGCTGAGGGGACAGATAGGGTTAT-3’ and 5’-GCACTCAAGGCAAGCTTTATTGAGGC-3’. The amplified product (945bp) was used as a template for a nested PCR reaction, which was performed using the TaKaRa Ex Taq Hot start version kit (Clonetech) with primers 5’-ACATACCTAGAAGAATAAGACAGG-3’ and 5’-GTCCCCAGCGGAAAGTCCCTTGT-3’. The final amplified PCR product was 705bp. To sequence viral DNA, both PCR amplification steps were performed with TaKaRa Ex Taq Hot start kit using the primers described above.

The final PCR product was purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and used to prepare a TruSeq-compatible and paired-end ready Illumina library. Deep sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq Sequencing platform (2×150) at the CCIB DNA Core Facility at MGH. Sequencing data were analyzed and subsequently entered into an automated de novo assembly pipeline. Amplicons were assembled using the MGH CCIB’s de novo assembler UltraCycler v1.0. (Brian Seed and Huajun Wang). Each assembly output was manually inspected and quality controlled.

Multiphoton intravital microscopy and image analysis

BLT NS mice were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and the popLN microsurgically exposed for MP-IVM as previously described (Murooka et al., 2012). Imaging depth was typically 80-200 μm below the LN capsule. For multiphoton excitation and second harmonic generation, a MaiTai Ti:sapphire laser (Newport/Spectra-Physics) was tuned to between 920 and 990 nm for optimized excitation of the fluorescent probes used. For four-dimensional recordings of cell migration, stacks of 11 optical sections (512 × 512 pixels) with 4 μm z-spacing were acquired every 15 seconds to provide imaging volumes of 40 μm in depth. Emitted light and second harmonic signals were detected through 455/50 nm, 525/50 nm, 590/50 nm, and 665/65 band-pass filters with non-descanned detectors. Data sets were transformed in Imaris 8.2 (Bitplane) to generate maximum intensity projections (MIPs) for export as QuickTime movies. We used automated or manual 2D tracking of cell centroids for all motility analyses, which yielded slightly lower velocities than 3D tracking, but more accurately described behaviors of elongated HIV-infected cells. Further cell track parameters (arrest coefficient, mean displacement (MD)) were analyzed in Matlab (Mathworks). Arrest coefficient was defined as the fraction of time in a track that a cell was migrating at a velocity below 4 μm/min. Motility co-efficients were derived from the linear segments of MD plots. 2-D Cell shapes were measured in ImageJ (NIH) by applying a color threshold and using the wand (tracing) tool and circularity indices calculated as CI = (4 × π × area)/(perimeter)2, resulting in values between 0 to 1, where 0 is a straight line and 1 indicates a perfect circle. All time-lapse sequences are accelerated 225× over real-time for display as Quicktime movies.

Live-cell imaging in 3D collagen

Glass slide chambers were constructed as previously described (Sixt and Lämmermann, 2011). 5-7 million TCM cells were infected with HIV-GFP for 2 days, washed and resuspended in a bovine Type I collagen (PureCol) to achieve a final concentration of 1.7mg/mL in each chamber. In some experiments, control T cells were labeled with 10μm Celltracker Blue (Invitrogen) prior to embedding in collagen. To inhibit actin polymerization, T cells were pre-treated with 1μM Latunculin A (Cayman Chemicals) for 15 minutes at 37°C prior to imaging. Chambers were allowed to solidify for 45 minutes at 37°C / 5% CO2 and placed onto a custom-made heating platform attached to a temperature controller apparatus (Warner Instruments). A thermocouple was used to continuously monitor and maintain the chamber temperature at 37°C. A multiphoton microscope with two Ti:sapphire lasers (Coherent) was tuned to between 780 and 920 nm for optimized excitation of the fluorescent probes used. For four-dimensional recordings of cell migration, stacks of 13 (or 26) optical sections (512 × 512 pixels) with 4 μm z-spacing were acquired every 15 (or 30) seconds to provide imaging volumes of 48 (or 96) μm in depth.

Emitted light was detected through 460/50 nm, 525/70 nm, and 595/50 nm dichroic filters with non-descanned detectors. All images were acquired using the 20× 1.0 N.A. Olympus objective lens (XLUMPLFLN; 2.0mm WD). 3-D recordings were processed in Imaris and exported as 2-D images sequences for further analysis in ImageJ, where MFIs in rectangular ROIs of constant size but adjusted in position from frame to frame were used in order to capture F-actin density at the same aspect of each cell over time. MFIs were normalized to yield an MFI of ‘1’ for each individual cell in order to directly compare fluctuations of F-actin formation based on the relative MFI independent of the absolute brightness of individual cells.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Numbers of individual cells, recordings, and animals analyzed are indicated in the figure legends as appropriate. Unpaired Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for comparisons of data sets with normal and non-normal distribution, respectively, using Prism 5 (GraphPad). Medians and p-values from statistical analyses are indicated in each graph. When p-values were larger than 0.05, differences were considered as not significant.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

MATLAB cell motility analysis scripts will be made available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1 (Related to Figure 1): Motility of cells infected with Nef-deficient HIV-1 in the lymph node. HIV-Tomato (infected cells appear red) and HIV-GFP ΔNef (infected cells appear green) were injected into the footpad of a BLT NS humanized mouse and the popLN prepared for MP-IVM after 2 days. Movie on the right shows individual cell tracks a ‘dragon tails’. Tissue autofluorescence is shown in light brown, second harmonic signals are shown in blue. Each individual frame is a maximum intensity projection of 11 z-stacks spaced 4 μm apart (total thickness of 40 μm). Scale bar = 30 μm. Time is shown in minutes and seconds. Events are accelerated 225× over real-time.

Movie S2 (Related to Figure 2):

HIV-Tomato Tomato (infected cells appear red) and HIV-GFP ΔVpu (infected cells appear green) were injected into the footpad of a BLT NS humanized mouse and the popLN prepared for MP-IVM after 3 days. Movie on the right shows individual cell tracks a ‘dragon tails’. Each individual frame is a maximum intensity projection of 11 z-stacks spaced 4 pm apart (total thickness of 40 μm). Scale bar = 30 μm. Time is shown in minutes and seconds. Events are accelerated 225× over real-time.

Movie S3 (Related to Figure 3):

HIV-Tomato and HIV-GFP ΔNef ΔEnv were injected into the footpad of a BLT NS humanized mouse and the popLN prepared for MP-IVM after 2 days. Top panels highlight cells infected with HIV-GFP ΔNef ΔEnv (infected cells appear green), bottom panels highlight cells infected with HIV-Tomato (infected cells appear red). Panels are taken from recordings where each individual frame is a maximum intensity projection of 11 z-stacks spaced 4 μm apart (total thickness of 40 μm). Scale bar = 10 μm. Time is shown in minutes and seconds. Events are accelerated 225× over real-time.

Movie S4 (Related to Figure 4):

HIV-Tomato (infected cells appear red) and HIV-GFP NefF191A (infected cells appear green) were injected into the footpad of a BLT NS humanized mouse and the popLN prepared for MP-IVM after 2 days. Movie on the right shows individual cell tracks a ‘dragon tails’. Each individual frame is a maximum intensity projection of 11 z-stacks spaced 4 μm apart (total thickness of 40 μm). Scale bar = 30 μm. Time is shown in minutes and seconds. Events are accelerated 225× over real-time.

Movie S5 (Related to Figure 5):

CD4+ human TCM were infected with HIV-Lifeact-GFP NefWT (top panel showing two representative cells) or NefF191A (bottom left panel) and embedded into collagen gels for live-cell imaging studies. Each individual frame is a maximum intensity projection of stack of 26 optical sections spaced 4 μm apart (total thickness of 100 μm). Lifeact-GFP intensity is displayed through a fire heatmap LUT. Time is shown in minutes and seconds. Events are accelerated 300× over real-time.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-human CD3-PE, Clone HIT3a | BioLegend | Cat. #300308 |

| anti-human CD4-Alexa Fluor700, Clone RPA-T4 | BioLegend | Cat. #300526 |

| anti-human CD8-APC/Cy7, Clone RPA-T8 | BioLegend | Cat. #301016 |

| anti-human CD19-BV421, Clone HIB19 | BioLegend | Cat. #302233 |

| anti-human CD45-FITC, Clone HI30 | BioLegend | Cat. #304006 |

| anti-mouse CD45-APC, Clone 30F11 | BioLegend | Cat. #103112 |

| anti-human CCR7(CD197)-PE, Clone G043H7 | BioLegend | Cat. #353203 |

| anti-human HLA-A,B,C-APC, Clone W6/32 | BioLegend | Cat. #311410 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP (BaL envelope) | Murooka et al. 2012 | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-Tomato (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-ΔNef (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-NefF191A (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-NefLLAA (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-ΔEnv (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-ΔEnv ΔNef (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43 Nef-IRES-GFP-ΔVpu (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43-NefF191A (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| HIV-1 NL43-ΔNef (BaL envelope) | This paper | N/A |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human de-identified peripheral blood mononuclear cells | MGH Blood Bank | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| QIAamp viral RNA kit | Qiagen | Cat. #52904 |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | Cat. #28106 |

| AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat. #80204 |

| QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit | Qiagen | Cat. #204154 |

| QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit | Qiagen | Cat. #204243 |

| FastStart Essential DNA Green Master mix | Roche | Prod. #06924204001 |

| SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum® Taq High Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Thermo Fisher | Cat. #12574030 |

| TaKaRa Ex Taq® DNA Polymerase Hot-Start Version | Clontech | Cat. #RR006A |

| GenElute HP Plasmid Maxiprep Kit | Sigma | Prod. #NA0310-1KT |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK 293T Cells | ATCC | Cat. #CRL-11268 |

| MAGI CCR5+ Cells | NIH AAARP | Cat. #3580 |

| TZM-bl Cells | NIH AAARP | Cat. #8129 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| NOD-scid mice | Jackson Laboratories | Stock #001303 |

| NOD-scid × γc−/− mice | Jackson Laboratories | Stock #005557 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Refer to Table S1 | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Imaris 8.2 | Bitplane | http://www.bitplane.com |

| ImageJ | Freeware/NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Prism 6 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com |

| FlowJo | Treestar | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Other | ||

HIGHLIGHTS.

HIV-1 impairs fast directional migration of infected T cells primarily via Nef

Nef perturbs the actin cytoskeleton through its C-terminal hydrophobic patch

Impaired infected T cell motility initially restrains HIV-1 systemic dissemination

Actin-cytoskeletal perturbation subsequently supports persistent HIV-1 viremia

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants AI097052, DA036298, and P01 AI078897 (to T.R.M), an MGH ECOR Tosteson Postdoctoral Fellowship Award, NIH U19 grant AI082630, the Harvard University CFAR Scholars award, and NIH training grant T32 AI007387 (to T.T.M.), a DFG research fellowship (US116-2-1), a Research Manitoba postdoctoral fellowship (to W.H.K.), an EMBO fellowship (ALTF534-2015) and a Marie Curie Global Fellowship (750973) (to M.D.P.).

The NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program provided MAGI-CCR5 cells and TZM-bl cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Abraham L, and Fackler OT (2012). HIV-1 Nef: a multifaceted modulator of T cell receptor signaling. Cell Commun. Signal 10, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agopian K, Wei BL, Garcia JV, and Gabuzda D (2006). A hydrophobic binding surface on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef core is critical for association with p21-activated kinase 2. Journal of Virology 80, 3050–3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agopian K, Wei BL, Garcia JV, and Gabuzda D (2007). CD4 and MHC-I downregulation are conserved in primary HIV-1 Nef alleles from brain and lymphoid tissues, but Pak2 activation is highly variable. Virology 358, 119–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora VK, Molina RP, Foster JL, Blakemore JL, Chernoff J, Fredericksen BL, and Garcia JV (2000). Lentivirus Nef specifically activates Pak2. Journal of Virology 74, 11081–11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R, Whitlock BM, Husson J, Le Floc’h A, Jin W, Oyler-Yaniv A, Dotiwala F, Giannone G, Hivroz C, Biais N, et al. (2016). Cytotoxic T Cells Use Mechanical Force to Potentiate Target Cell Killing. Cell 165, 100–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl S, Iafrate AJ, Lang SM, Stolte N, Stahl-Hennig C, Mätz-Rensing K, Fuchs D, Skowronski J, and Kirchhoff F (2000). Simian immunodeficiency virus containing mutations in N-terminal tyrosine residues and in the PxxP motif in Nef replicates efficiently in rhesus macaques. Journal of Virology 74, 4155–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C-P, Siu Y-T, Kok K-H, Ching Y-P, Tang H-MV, and Jin D-Y (2013). Group I p21-activated kinases facilitate Tax-mediated transcriptional activation of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeats. Retrovirology 10, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran P, Buckley M, Moore V, Wang LQ, Kehrl JH, and Venkatesan S (2012). HIV-1 Nef impairs heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by targeting Gα(i2) for degradation through ubiquitination. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287, 41481–41498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deruaz M, Murooka TT, Ji S, Gavin MA, and Vrbanac VD (2017). Chemoattractant-mediated leukocyte trafficking enables HIV dissemination from the genital mucosa. JCI Insight. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek TE, No DC, Seung E, Vrbanac VD, Fadda L, Bhoumik P, Boutwell CL, Power KA, Gladden AD, Battis L, et al. (2012). Rapid evolution of HIV-1 to functional CD8+ T cell responses in humanized BLT mice. Sci Transl Med 4, 143ra98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackler OT, Murooka TT, Imle A, and Mempel TR (2014). Adding new dimensions: towards an integrative understanding of HIV-1 spread. Nat Rev Micro 12, 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Otake K, Tashiro M, and Adachi A (1996). Soluble Nef antigen of HIV-1 is cytotoxic for human CD4+ T cells. FEBS Letters 393, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrecka K, Swigut T, Schindler M, Kirchhoff F, and Skowronski J (2005). Nef proteins from diverse groups of primate lentiviruses downmodulate CXCR4 to inhibit migration to the chemokine stromal derived factor 1. Journal of Virology 79, 10650–10659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imle A, Abraham L, Tsopoulidis N, Hoflack B, Saksela K, and Fackler OT (2015). Association with PAK2 Enables Functional Interactions of Lentiviral Nef Proteins with the Exocyst Complex. MBio 6, e01309–e01315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaqaman K, and Grinstein S (2012). Regulation from within: the cytoskeleton in transmembrane signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 515–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler HW, Ringler DJ, Mori K, Panicali DL, Sehgal PK, Daniel MD, and Desrosiers RC (1991). Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell 65, 651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IH, Sawai ET, Antonio E, Weber CJ, Mandell CP, Montbriand P, and Luciw PA (1998). Role of the SH3-ligand domain of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef in interaction with Nef-associated kinase and simian AIDS in rhesus macaques. Journal of Virology 72, 5820–5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff F, Easterbrook PJ, Douglas N, Troop M, Greenough TC, Weber J, Carl S, Sullivan JL, and Daniels RS (1999). Sequence variations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef are associated with different stages of disease. Journal of Virology 73, 5497–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff F, Greenough TC, Brettler DB, Sullivan JL, and Desrosiers RC (1995). Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 332, 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff F, Schindler M, Bailer N, Renkema GH, Saksela K, Knoop V, Müller-Trutwin MC, Santiago ML, Bibollet-Ruche F, Dittmar MT, et al. (2004). Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected chimpanzees interact with p21-activated kinase 2 and modulate cell surface expression of various human receptors. Journal of Virology 78, 6864–6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koup RA, Safrit JT, Cao Y, Andrews CA, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, and Ho DD (1994). Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. Journal of Virology 68, 4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law KM, Komarova NL, Yewdall AW, Lee RK, Herrera OL, Wodarz D, and Chen BK (2016). In Vivo HIV-1 Cell-to-Cell Transmission Promotes Multicopy Micro-compartmentalized Infection. CellReports 15, 2771–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Belkina NV, and Shaw S (2009). HIV infection of T cells: actin-in and actin-out. Sci Signal 2, pe23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, and Garcia JV (1996). The association of Nef with a cellular serine/threonine kinase and its enhancement of infectivity are viral isolate dependent. Journal of Virology 70, 6493–6496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J, and Helenius A (2008). Vaccinia virus uses macropinocytosis and apoptotic mimicry to enter host cells. Science (New York, N.Y.) 320, 531–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meribe SC, Hasan Z, Mahiti M, Mwimanzi F, Toyoda M, Mori M, Gatanaga H, Kikuchi T, Miura T, Kawana-Tachikawa A, et al. (2015). Association between a naturally arising polymorphism within a functional region of HIV-1 Nef and disease progression in chronic HIV-1 infection. Arch. Virol. 160, 2033–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel N, Allespach I, Venzke S, Fackler OT, and Keppler OT (2005). The Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus establishes superinfection immunity by a dual strategy to downregulate cell-surface CCR5 and CD4. Curr. Biol. 15, 714–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]