Abstract

We report a plasmonic interferometer array (PIA) sensor and demonstrate its ability to detect circulating exosomal proteins in real-time with high sensitivity and low cost to enable the early detection of cancer. Specifically, a surface plasmon wave launched by the nano-groove rings interferes with the free-space light at the output of central nano-aperture and results in an intensity interference pattern. Under the single-wavelength illumination, when the target exosomal proteins are captured by antibodies bound on the surface, the biomediated change in the refractive index between the central aperture and groove rings causes the intensity change in transmitted light. By recording the intensity changes in real-time, one can effectively screen biomolecular binding events and analyze the binding kinetics. By integrating signals from multiple sensor pairs to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, superior sensing resolutions of 1.63×10−6 refractive index unit (RIU) in refractive index change and 3.86×108 exosomes/mL in exosome detection were realized, respectively. Importantly, this PIA sensor can be imaged by a miniaturized microscope system coupled with a smart phone to realize a portable and highly sensitive healthcare device. The sensing resolution of 9.72×109 exosomes/mL in exosome detection was realized using the portable sensing system building upon a commercial smartphone.

Keywords: Plasmonic interferometer, optical biosensor, exosome, cancer diagnosis

I. Introduction

Cancer is a serious socioeconomic problem. Effective screening and early detection are the only way to improve the chance of successful treatment and reduce cancer mortality. Mobile medical devices have great potential to impact the fight against this global health problem, especially in areas where medical resources are limited. In particular, it was estimated that approximately two-thirds of global cell-phones are actually being used in the developing world (e.g. Africa, Asia) [1]. Therefore, sensitive biomedical devices integrated with smart-phones would yield promising mobile medical devices for cancer screening and early detection and introduce great impact on point-of-care diagnostics in developing countries and resource-limited areas.

Surface plasmons (SPs) are coherent oscillations of conduction electrons on a metal surface excited by electromagnetic radiation at the metal-dielectric interface [2]. The extremely high sensitivity of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to the refractive index (RI) change on the metal surface has led to the development of SPR sensing systems, which typically use prisms to couple obliquely incident light into SP waves propagating on a flat, continuous metal film (typically gold) [3]. However, the conventional SPR systems are limited by expensive equipment and bulky footprint. Therefore, they are not suitable for cost-effective, point-of-care diagnostic tests. To overcome these challenges, nanoplasmonic biosensors have received significant attentions as attractive miniaturized platforms for sensitive, label-free and high throughput detection of bio-chemical analytes. The most popular nanoplasmonic sensor architectures studied in recent years are metallic nanohole or nanopattern arrays (e.g. [4–8]). However, instead of further improving the sensing limit, recent major efforts have mainly focused on the integration of nanoplasmonic sensing elements with different sensing systems to enable more portable sensing applications. For instance, a nanohole array plasmonic biosensor was integrated with the smart-phone microscope and resolved a 3nm-thick monolayer of bovine serum albumin (BSA) molecules (corresponding to the surface coverage sensitivity of ~4 ng/mm2) [9]. More recently, researchers developed a nanoplasmonic exosome (nPLEX) assay to analyze ascites samples from ovarian cancer patients [10]. The nPLEX assay used exosomal CD24 and EpCAM as the biomarkers and discriminated ovarian cancer patients from noncancerous cirrhosis patients with high accuracy, demonstrating its potential for exosome based cancer diagnostics [11]. Since the target cancer biomarker (i.e. exosomes) are 50~100-nm-sized nanoparticle, it does not require record-breaking sensitivity to resolve their binding events on sensor surface. For these applications, the key target is the integration of plasmonic nanostructures with low-cost experimental settings to realize high performance sensing. However, most previously reported plasmonic sensing devices are based on wavelength modulation (e.g. [4–8]). Therefore, high spatial density multiplexed measurements are difficult to achieve in that broadband wavelength analysis because a spectrometer is required, which inevitably adds to the size and cost of the entire system.

We previously developed a plasmonic interferometer array (PIA) biosensor based on wavelength modulation generated by ring-hole nanostructures. Using this type PIA biosensor, the sensitive detection of BSA surface coverage as low as 0.4 pg mm 2 was realized [12]. In this study, we have further developed the PIA biosensor using intensity modulation at a single wavelength by optimizing the geometry of the ring-hole nanostructure. These new designs allow us to monitor the intensity change from each sensor unit, which enables superior detection sensitivity but requires neither spectrometer nor angle-tunable prism-coupling system, leading to a significant reduction in device cost and instrumental complexity. We have also integrated the PIA biosensor in an optofluidic biochip and attached to the imaging system of a smart-phone for general portable biosensing.

II. Sensor design and fabrication

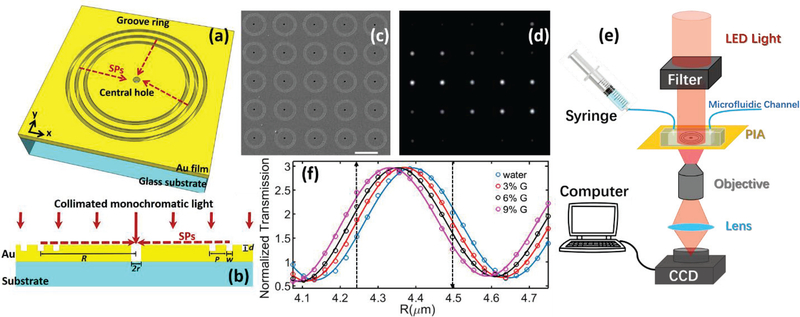

Fig.1 (a) illustrates the ring-hole plasmonic interferometer structure with a nanohole in a metal film surrounded by concentric circular nanogrooves. When the incident light illuminates the structure at the normal direction, SP waves are launched at the grooves. They will propagate along the radial direction of the rings towards the central nanohole and interfere with the directly-transmitted light through the central nanohole (see Fig.1 (b) for the cross-sectional diagram). In this case, the transmitted light intensity at a given wavelength, λ, through the plasmonic interferometer can be described as:

| (1) |

where Ifree and Isp are intensities of the free-space and SP-mediated light, respectively. The cosine term represents the interference between these two components. Here R is the radius of the circular ring; λ is incident wavelength; nsp = Re[(εmn2/(εm+n2))1/2] represents the effective RI for SPs at the metal/dielectric interface, where εm is the metal permittivity, n is the RI of the dielectric medium on top of the metal surface; 𝜑0 is an additional phase shift introduced during the SP coupling process at the nanogroove [13]. According to this equation, the transmitted light intensity It at a given λ can be modulated by R and nsp.

Fig. 1.

(a). Schematic of a ring-hole plasmonic interferometer. (b) Cross-section view. (c) SEM image of a 5X5 array of plasmonic interferometer with increasing R from left to right, bottom to top. (d) Transmitted light of the interferometer array was imaged on the CCD camera. (e) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup. (f) Transmission of each interferometer was modulated sinusoidally by R, showing different sensitivity when glycerolwater solutions of increased concentrations were flowed on the sensor surface. Black arrows indicate the interferometers with highest sensitivities.

To demonstrate the intensity-modulated biosensor, we used Focused Ion Beam (FIB) milling to fabricate a 5×5 array of ring-hole plasmonic interferometers on a 250-nm gold film that was deposited on a glass substrate with 5-nm titanium adhesion layer in between. As we can see from its SEM image shown in Fig.1 (c), the diameter of the ring, R, increases from 4.07 μm to 4.75 μm with the step size of ~28 nm. According to our previous investigation [14], the efficiency of a single nanogroove to couple normally-incident free-space light at λ into SPs depends on its width (w) and depth (d). By optimizing these two parameters in numerical modeling and calculating the theoretical SP coupling efficiency, we selected a set of parameters for nanofabrication (i.e. w=240 nm and depth d=70 nm). To further enhance the coupled-SP intensity, three grooves were selected in this experiment with the groove period P = 480 nm, which was designed to match with the effective wavelength of SPs (i.e., λsp= nspλ) under water environment so that SPs generated at each groove are tuned in phase. The diameter of the central hole was tuned to 620 nm to control the directly transmitted light intensity to match the SPintensity and maximize the interference contrast. The center-to-center distance between two adjacent elements along x and y direction are both 12.5 μm. In our optical characterization, a collimated LED source (Thorlabs M660L3-C1, operated at 800 mW) was passed through a laser line filter (Thorlabs FL670–10) to get a narrow-band red light with a centered wavelength λ = 665 nm and a linewidth of ~7-nm, which was employed to illuminate fabricated PIA sample at the normal direction. The transmitted image of the sensor array was collected by a 40X objective lens (NA = 0.6) and imaged using a CCD camera (Hamamatsu C8484–03G02). The camera exposure time was set as 160 ms and the capture rate was 37 frames/min. As a result, one can see from Fig. 1(d) that the transmitted intensity of each interferometer unit was modulated by R when n is fixed at ~1.33 (i.e., water environment under room temperature).

To calibrate the sensing performance, a PDMS-based microfluidic channel was bonded on the sensor chip to introduce glycerol-water solutions with different concentrations to control the bulk RI (Fig. 1(e)). When the water is injected into the microfluidic channel, each element shows different brightness, demonstrating the intensity interference at a single wavelength transmitted through the array as the function of R. As shown in Fig. 1(f), the extracted intensity is normalized by the transmitted light intensity through a reference hole without grooves, showing an interference period of ~490 nm, very close to λsp and therefore verifying the interference mechanism. As the RI increases, the transmitted intensity from each sensing element will either increase or decrease. The highest sensitivity among these sensing elements can be obtained at the waist of the interference pattern as indicated by the two black dashed lines in Fig. 1(f), which are 8.8×103 %/RIU and 6.7 ×103 %/RIU, respectively. This intensity-modulated sensitivity obtained from a single plasmonic interferometer is equivalent to the best results obtained by intensity-modulated nanohole arrays based on dual-polarization responses [15].

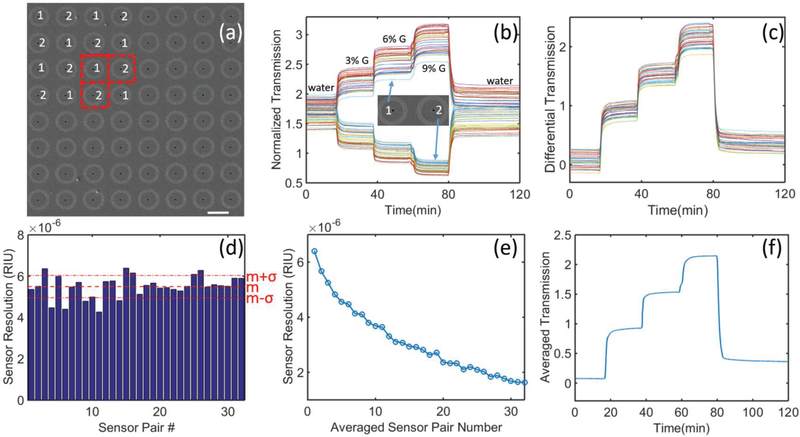

To enhance the sensor performance, we then fabricated these two most sensitive interferometers (i.e. R1 = 4.25 μm and R2 = 4.50 μm) as an 8×8 “chessboard” array (see Fig. 2 (a) for its SEM image). Real-time responses of all interferometer units in the array are plotted in Fig. 2 (b). In this experiment, different solution samples were used to tune the bulk refractive index. The refractive indices of the deionized water and a series of glycerol-water solutions (i.e., 3%, 6%, and 9% glycerol solutions) are 1.3328, 1.3370, 1.3419, and 1.3463, respectively (characterized using Reichert, Part #13940014). One can see that the interferometers with two selected radius showed opposite response to the bulk RI change on the sensor surface. As the RI increases on the sensor surface, the transmitted intensity of the R1 sensor unit increases, while the intensity of the R2 sensor unit decreases at the same time. Therefore, any horizontally or vertically adjacent two interferometers can work as a sensor pair (see red dashed squares in Fig. 2 (a)). Since adjacent sensor units are spatially close to each other, they should share a similar background signal introduced by inevitable fluctuations in the microfluidic channel (e.g. localized light intensity fluctuation, environment temperature variation, system mechanical vibrations, etc.) [16]. Using this self-reference strategy, the background signal change can easily be removed by calculating their differential signal. For instance, here we consider every two horizontally adjacent interferometers as a sensor pair. The differential signals of 32 sensing pairs are plotted in Fig. 2 (c). By subtracting the decreasing R2 signal from the increasing R1 signal, the signal changes from these two sensor units were added up. Importantly, the background noise was removed, resulting in a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). As shown in Fig. 2(d), we calculated the resolution of the 32 sensor pairs, showing great repeatability in the range of 4.2~6.3×10−6 RIU (with the mean value, m, of 5.50×10−6 RIU and the standard deviation, 𝜎, of 5.37×10−7 RIU). This resolution is better than previously-reported best nanoplasmonic biosensors based on intensity modulation [15, 17–19].

Fig.2.

(a) SEM image of an 8 × 8 “chessboard” array of ring-hole plasmonic interferometers with two different radius (R1 =4.25 μm and R2=4.5 μm). Scale bar: 10λm. (b) Real-time transmission signals of each interferometer in the array in response to different concentrations of glycerol-water solutions flowing on the metal surface. (c) Differential signal of 32 pairs of neighboring interferometers. (d) Enumeration of sensor resolution of each pair of neighboring interferometers. Their mean value and standard deviation are represented by m and σ, respectively. (e) Sensor resolution can be improved by averaging signals of multiple sensor pairs. (f) Real-time transmission response by averaging signals of all 32 sensor pairs.

Moreover, by averaging signals of all 32 sensor pairs, the noise can be reduced and hence the sensor resolution can be optimized further. As shown in Fig. 2(e), we plot the sensor resolution versus the number of sensor pairs used in the signal averaging process (i.e. 1 to 32), showing that the overall sensing resolution can be reduced to ~1.63×10−6 RIU. The averaged signal of all 32 sensor pairs is shown in Fig. 2 (f), demonstrating a much better SNR compared with the original data shown in Fig. 2 (d). Remarkably, this RI sensing resolution is already comparable to those of the best commercial SPR imaging systems (2–5×10−6 RIU) [20, 21]. By employing higher performance light sources and CCD cameras with lower noise, this performance can be improved further. On the other hand, instead of competing the sensing limit, recent major efforts have mainly focused on the development of portable optical biosensing systems by integrating nanoplasmonic sensing elements with miniaturized optical components (e.g. [9, 22]). Next, we will integrate the PIA sensor with an optofluidic biochip and show the feasibility of using the PIA biochip to detect circulating biomarkers in blood for cancer diagnosis.

III. Real-time detection of exosomal EGFR using the PIA biochip

To demonstrate the potential of the PIA biochip as a mobile medical device for disease diagnosis, we selected lung cancer as the disease model, which is the leading cause of cancer-deaths around the world [23], and exosomal EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) as the biomarker. Exosomes are nano-sized (50–100nm) extracellular vesicles secreted by many cell types under normal physiological conditions and exist widely in a variety of body fluids, such as blood and urine [24, 25]. Exosomes transfer DNA, RNA, microRNA, proteins and lipids from parent cells to recipient cells, and serve as “messengers” for cell-cell communication [26]. Exosomes are actively involved in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance [27]; therefore, they are promising cancer biomarkers for non-invasive, in vitro diagnostics. For examples, exosomal glypican-1 detected early stages of pancreatic cancer with 100% sensitivity and specificity [28]. Here we selected exosomal EGFR as the biomarker for lung cancer detection because EGFR is a lung cancer driver gene and regulates cancer cell proliferation and survival [29]. Recent studies indicate that the expression of exosomal EGFR is significantly dysregulated in plasma samples from lung cancer patients [30, 31] and is closely correlated with lung cancer patients’ overall survival rate [32], indicating the promising value of exosomal EGFR in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

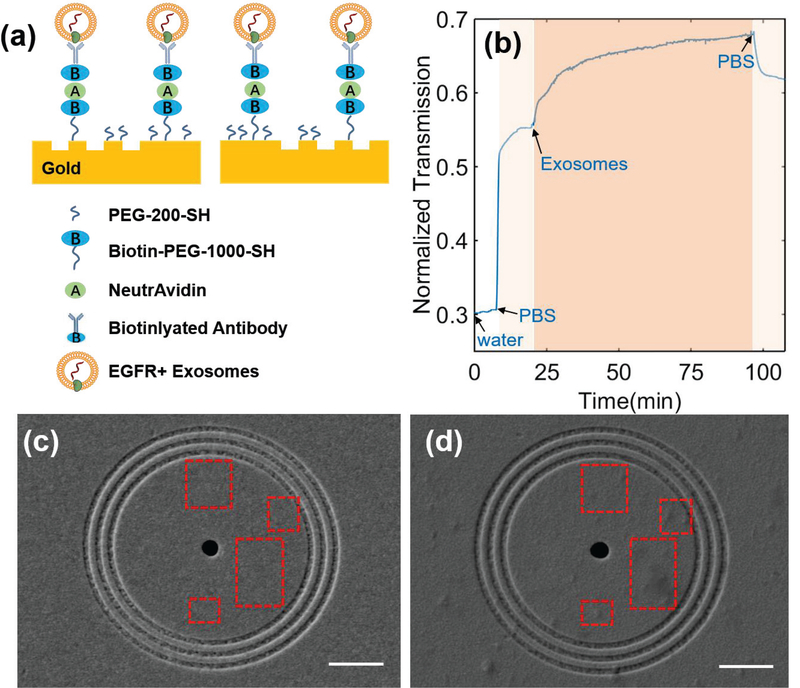

To demonstrate the feasibility of using the PIA biochip for cancer diagnosis, we first used a desktop microscope (Olympus IX81) to measure the expression of EGFR on the exosomes derived from A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. To enable the sensing of exosomal EGFR, anti-EGFR antibodies were conjugated on the surface through a series of surface modification steps. As shown in Fig. 3(a), a mixture of PEG200-SH and biotin-PEG-1000-SH (1:3 molar ratio, 10mM in PBS) was first applied on the surface of gold nanostructures for 1 hour. After washing off unbound PEG, 5 ng/mL NeutrAvidin was added and incubated on the biochip for 1 hour. Then the extra NeutraAvidin was removed by PBS washing. Finally, 0.05 mg/mL biotinylated anti-EGFR antibodies were applied and incubated on the biochip for 1 hour to allow the binding of antibodies on the surface through biotin-avidin interaction. After the removal of excess antibodies by PBS washing, the PIA biochip was ready for use. All the modification steps were performed at room temperature.

Fig. 3.

(a) Schematic diagram of the developed ring-hole PIA biochip with captured EGFR+ exosomes. (b) Real-time response of 18-pair sensing units upon exosome adsorption on the sensor surface. (c-d) SEM images of the sensor surface (c) before and (d) after exosome binding. Scale bar: 2 μm. Red squares indicate obvious exosome binding within the ring area after exosome binding.

To measure the level of exosomal EGFR, deionized-H2O (Di-H2O) and PBS solutions were fed through the PIA biochip at 0.02 mL/min for 10 minutes each to collect the baseline signals (Iwater and IPBS). As shown in Fig. 3(b), the transmission signal intensity increased after PBS solution injection due to the RI change (i.e., from Water 1.3328 to PBS 1.3343). The exosomes derived from A549 cells were suspended in PBS buffer at the concentration of 2×1010 exosomes/mL, and introduced into the PIA biochip at a flow rate of 0.02 mL/min. A quick increase of the signal intensity was observed right after the exosomes entered the PIA biochip. Then the signal intensity leveled off and reached plateau at time of 3×103 seconds. The dynamic change of the transmission signal intensity demonstrated the successful capture of exosomes via anti-EGFR antibodies on the biochip. Finally, PBS was flowed through the PIA biochip at 0.02 mL/min for 10 min to wash off all non-specifically bound exosomes. The transmission signal intensity after PBS wash was recorded as Iexosome. The expression (E) of exosomal EGFR observed in this PIA biochip was 0.21, which was calculated using the following equation (2). The PIA biochip showed a high detection sensitivity with the SNR of 51.76, corresponding to the resolution of 3.86×108 exosomes/mL.

| (2) |

To further demonstrate the capture of exosomes by the anti-EGFR antibodies on the biochip, we took the SEM images of the biochip surface before and after exosome binding. As shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d), a number of exosomes were observed around the ringhole nanostructures as indicated by the red dotted rectangles. The sensitive detection of lung cancer cell-derived exosomal EGFR with high SNR indicated the potential application of the PIA biochip in exosome-based cancer diagnosis. It is important to note that our sensor footprint (70 μm 70 μm) is around two orders of magnitude smaller than that of commercial prism-based SPR systems. This largely improved sensor resolution per unit area facilitates sensor integration with compact microfluidics and also decreases the sample consumption. Furthermore, the collinear transmission setup of our platform is much simpler than the angle tuning operational mode of conventional SPR systems, and has great potential for system miniaturization and low-cost production.

IV. Integration of the PIA biochip with a smart-phone-based microscope system

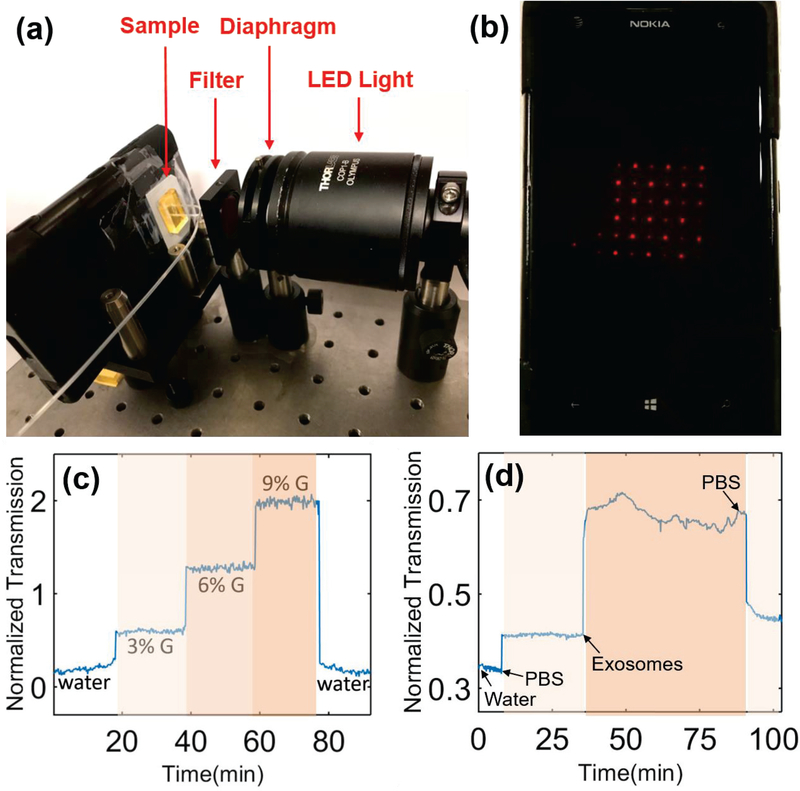

Because of the world-wide cell-phone subscription, mobile medical devices have attracted significant attention to combat global health problems, such as cancer, especially for developing countries and resource-limited areas. It will be very beneficial if we can integrate the highly sensitive and low-cost PIA biochip with the imaging system of smart-phones. Therefore, in this section, we continued to investigate the possibility of detecting exosomal EGFR using a smart-phone-based microscope. As shown in Fig. 4(a), a miniaturized plano-concave lens with a diameter of 1 mm (Edmund) was embedded in a homemade phone-case and aligned with the smartphone camera (Nokia Lumia 1020), comprising a portable microscopy system with the magnitude of approximately 10X. By adjusting the simple optical system shown in Fig. 4(a), the transmitted light through a 6×6 plasmonic interferometer array was detected by the built-in CMOS camera of the cell phone (Fig. 4(b)). A series of glycerol-water solutions (i.e., 3%, 6%, and 9% glycerol solutions) were first tested on the PIA biochip to quantify its sensitivity and resolution. As shown in Fig. 4 (d), after the glycerol solutions were flowed into the PIA biochip, the transmission intensity through the plasmonic interferometer increased with increasing concentration of glycerol solutions. After washing off the biochip with deionized water, the transmission intensity signal returned back to the baseline. Compared with the same PIA biochip characterized using the desktop microscope shown in Fig. 2, we obtained a similar optical response with larger noise due to the intrinsic noise of the built-in CMOS camera. We estimated that the sensitivity and resolution of the PIA biochip coupled with the smart-phone imaging system are 1.35×104%/RIU and 1.27×10−4 RIU, respectively.

Fig. 4.

(a) Proof-of-concept experiment setup of the mobile PIA biochip integrated with the smart-phone imaging system. (b) The screen of the smart-phone (Nokia Lumia 1020) with the PIA biochip transmission image. (c-d) Real-time response of (c) bulk refractive index and (d) surface binding changes measured by the PIA biochip coupled with the smart-phonebased microscope.

Next, we investigated the feasibility of exosomal EGFR detection using the mobile PIA sensing setup. A similar surface treatment procedure was employed to modify the sensor surface with anti-EGFR antibodies. Di-H2O and PBS solutions were fed into the PIA biochip at flow rate of 0.02 mL/min for 10 minutes and 20 minutes respectively to collect the baseline signals (i.e., Iwater and IPBS). Then exosomes derived from A549 lung cancer cells were resuspended in PBS at the concentration of 8×1010 exosomes/mL and flowed into the PIA biochip at a flow rate of 0.02mL/min. As shown in Fig. 4(d), similar phenomena were observed through the smartphone-based PIA sensing system compared with the results obtained using the desktop microscope system (Fig. 3(b)). The expression of exosomal EGFR was calculated as 0.49 using (Eq. 2). The SNR of the results obtained by the smart-phone-based system was calculated as 8.23, corresponding to the sensing resolution of 9.72×109 exosomes/mL. Although the concentration of exosomes applied in the smartphone-based PIA sensing system (8×1010 exosomes/mL) was 4 times higher than that of exosomes applied in the desktop microscope system (2×1010 exosomes/mL), we only observed 2.33-fold, instead of 4-fold, increase in exosomal EGFR level. The relatively lower sensing performance should be attributed to the limited resolution and noise level of the low-cost smart-phone camera. However, these experimental results successfully demonstrated the feasibility of the mobile PIA biochip in detecting exosomal protein biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. An improved sensing performance is expected if higher performance components are employed in the portable systems, which is still under investigation. For the next step, the clinical utility of the PIA biochip in cancer diagnosis will be further demonstrated using blood samples from cancer patients and normal controls, which is still under investigation. While such devices may not be able to completely replace advanced diagnostics in hospitals, they will provide “early warnings” that will improve the overall early detection of lung cancer and many other types of cancer/diseases, and thus reduce the mortality.

V. Conclusion

In conclusion, we reported a highly integrated, portable ring-hole PIA biochip, which is a highly sensitive, cost-effective, fast/real-time and label-free optical sensor for specific sensing of biomolecules, such as exosomal proteins. By combining two complementary sensor units, the background fluctuation can be minimized, resulting in the sensing resolution of ~1.63×10−6 RIU by integrating multiple sensor units signals observed using the desktop microscope. Surface binding of exosomes with the sensing resolution of 3.86×108 exosomes/mL and 9.72×109 exosomes/mL was successfully realized on the desk-top optical microscope and the smart-phonebased microscope, respectively. The proposed high performance and compact sensor system is critical for overcoming size, cost and detection time barriers of conventional technologies. Compared with conventional prism-based SPR systems, our miniaturized, compact PIA platform does not require angular tunable prism coupling systems, and therefore can be realized with a significant reduction in device cost and instrumental complexity. This smartphone-based, highly sensitive, and low cost PIA biochip is promising for label-free sensing with great impact on point-of-care diagnostics. It can assist in advancing basic cancer research, and serve as a routine pre-screening and rapid diagnostic tool that could complement more invasive and expensive testing and provide additional information for clinical decision making. When combined with wireless communication and signal processing advances, such portable diagnosis tools can be used to construct a global biosensor network to monitor and control the global endemic disease threats. We expect that this mobile biosensing system with PIA biochips will have potentially transformative impact on biosensing, cancer screening and overall health care.

Acknowledgement:

We acknowledge the funding support from National Science Foundation under award number IIP-1718177, ECCS-1807463 and the funding support from National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number 5R33CA191245. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Dr. Xie Zeng received his B.S. in Honor Program (Information Science) from China Agricultural University, Beijing, China in 2008, and his M.S. in Optical Engineering from Beihang University, Beijing, China in 2011, and Ph.D. in Nano-optics and Bio-photonics from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 2016. His research interests include plasmonics, biosensors, micro/nanofabrication and signal/image processing.

Yunchen Yang received his B.S. in Biochemistry and Biotechnology from Xiamen University in 2016. He is working as a Ph.D. candidate in the Biomedical Engineering Department from the State University of New York at Buffalo since 2016. His research interests include development of biosensors, cancer theranostics and biomarkers.

Nan Zhang received his Bachelor degree in engineering from Beijing Institute of Technology in 2012. He is currently working towards the Ph.D. degree in the Electrical Engineering Department from the State University of New York at Buffalo. His current research interests include nanooptics, opto-electronics and bio-photonics.

Dr. Dengxin Ji received his B.S. in Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu, China in 2010, and his Ph.D. in Nanooptics and Bio-photonics from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 2018. His research interests include metamaterials, plasmonics, biosensors, and micro/nano-fabrication.

Dr. Xiaodong Gu received his Bachelor degree in Clinical Medicine from Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China in 2004 and the M.D. degree in General Surgery from Fudan University, Shanghai, China in 2010. He is currently an Attending Physician at Department of General Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University. He has established perfect clinical follow-up database and sample database, His research interests include circulating biomarker discovery and cancer biology.

Josep Miquel Jornet (S’08– M’13) received the B.S. degree in telecommunication engineering and the M.Sc. degree in information and communication technologies from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, in 2008, and the Ph.D. degree in electrical and computer engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), Atlanta, GA, USA, in 2013. From 2007 to 2008, he was a Visiting Researcher with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, under the MIT Sea Grant Program. He is currently an Assistant Professor with the Department of Electrical Engineering, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. His current research interests are in terahertz-band communication networks, nanophotonic wireless communication, intra body wireless nanosensor networks, and the Internet of Nano-Things. He is a member of the ACM. He also serves in the Steering Committee of the ACM Nanoscale Computing and Communications Conference series. He was a recipient of the Oscar P. Cleaver Award for outstanding graduate students in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Georgia Tech, in 2009. He also received the Broadband Wireless Networking Lab Researcher of the Year Award in 2010. In 2016 and 2017, he received the Distinguished TPC Member Award at the IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, one of the premier conferences of the IEEE Communications Society. In 2017, he received the IEEE Communications Society Young Professional Best Innovation Award. Since 2016, he has been an Editor-in-Chief of the Nano Communication Networks Journal (Elsevier).

Dr. Yun Wu received her Bachelor and Master’s degree in Polymer Materials and Engineering from Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China in 2000 and 2002 respectively. She received her Ph.D. in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA in 2009. After completion of her degree, she received her postdoc training in the NSF Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center at the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. She is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Her current research focuses on the development of innovative biosensors for cancer screening, diagnosis and prognosis and the development of multifunctional nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. Her research has been supported by National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Science Foundation, and Food and Drug Administration. She has published 3 book chapters, >35 peer-reviewed papers and 1 patent. She received Biomedical Engineering Innovation and Career Development Award from Biomedical Engineering Society in 2013, UUP Discretionary Lump-Sum Awards from University at Buffalo in 2015 and 2016. She now serves as the associate editor for Scientific Reports (NPG).

Dr. Qiaoqiang Gan (S’06M’11) received his Bachelor’s degree from Fudan University, Shanghai, China in 2003, his Master’s degree in 2006 in nano-photonics at the Nano-Optoelectronics Lab in the Institute of Semiconductors at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his Ph.D. degree from Lehigh University in 2010. He is currently an Associate Professor at the Electrical Engineering Department, University at Buffalo (UB), The State University of New York. He is an applied physicist with extensive experience in development of applications based on nanophotonic structures/ devices. Since 2011, he has been directing the NanoOptics and Biophotonics Laboratory, UB, where he is currently involved in miniaturized and portable biosensors, such as plasmonic devices and cellphone-based microscope, fundamental research on energy, and novel nanofabrication technologies. His research publications include over 90 technical papers and 4 patents. He serves as the associate editor for Scientific Reports (NPG), IEEE Photonics Journal and J. of Photonics for Energy (SPIE).

References

- [1].International Telecommunication Union, ITU Key 2015–2017 ICT Data. Available: https://www.itu.int/en/ITUD/Statistics/Documents/statistics/2017/ITU_Key_2005–2017_ICT_data.xls

- [2].Raether H, Surface Plasmons on Smooth and Rough Surfaces and on Gratings: Springer, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Homola J and Piliarik M, “Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensors,” in Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Sensors. vol. 4, Homola J, Ed., ed: Springer Berlin; Heidelberg, 2006, pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Soler M, Belushkin A, Cavallini A, Kebbi-Beghdadi C, Greub G, and Altug H, “Multiplexed nanoplasmonic biosensor for one-step simultaneous detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine,” Biosensors and Bioelectronics, vol. 94, pp. 560–567, 2017/08/15/ 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li X, Soler M, Ozdemir CI, Belushkin A, Yesilkoy F, and Altug H, “Plasmonic nanohole array biosensor for label-free and real-time analysis of live cell secretion,” Lab on a Chip, vol. 17, pp. 2208–2217, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Peter LD, Eugeniu B, Yongsop H, Catherine S, and Brian A, “Optical Chemical Barcoding Based on Polarization Controlled Plasmonic Nanopixels,” Advanced Functional Materials, vol. 28, p. 1704842, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Abid A, P. HL, Sujin S, Khawar DF, R. GM, L. GL, et al. , “Plasmonic Sensing of Oncoproteins without Resonance Shift Using 3D Periodic Nanocavity in Nanocup Arrays,” Advanced Optical Materials, vol. 5, p. 1601051, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bowen L, Shu C, Jiancheng Z, Xu Y, Jinhui Z, Haixin L, et al. , “A Plasmonic Sensor Array with Ultrahigh Figures of Merit and Resonance Linewidths down to 3 nm,” Advanced Materials, vol. 30, p. 1706031, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cetin AE, Coskun AF, Galarreta BC, Huang M, Herman D, Ozcan A, et al. , “Handheld high-throughput plasmonic biosensor using computational on-chip imaging,” Light: Science & Applications, vol. 3, p. e122, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Im H, Shao H, Park YI, Peterson VM, Castro CM, Weissleder R, et al. , “Labelfree detection and molecular profiling of exosomes with a nano-plasmonic sensor,” Nat Biotech, vol. 32, pp. 490–495, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Im H, Shao H, Weissleder R, Castro CM, and Lee H, “Nano-plasmonic exosome diagnostics,” Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, vol. 15, pp. 725–733, 2015/06/01 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gao Y, Xin Z, Zeng B, Gan Q, Cheng X, and Bartoli F, “Plasmonic interferometric sensor arrays for high-performance labelfree biomolecular detection,” Lab on a Chip, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zeng X, Hu H, Gao Y, Ji D, Zhang N, Song H, et al. , “Phase change dispersion of plasmonic nano-objects,” Sci. Rep, vol. 5, 07/29/online 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gan Q, Gao Y, Wang Q, Zhu L, and Bartoli F, “Surface plasmon waves generated by nanogrooves through spectral interference,” Physical Review B, vol. 81, p. 085443, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Blanchard-Dionne A, Guyot L, Patskovsky S, Gordon R, and Meunier M, “Intensity based surface plasmon resonance sensor using a nanohole rectangular array,” Opt. Express, vol. 19, pp. 15041–15046, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gao Y, Gan Q, Xin Z, Cheng X, and Bartoli FJ, “Plasmonic Mach–Zehnder Interferometer for Ultrasensitive On-Chip Biosensing,” ACS Nano, vol. 5, pp. 9836–9844, 2011/12/27 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Escobedo C, Vincent S, Choudhury A, Campbell J, Brolo A, Sinton D, et al. , “Integrated nanohole array surface plasmon resonance sensing device using a dualwavelength source,” Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, vol. 21, p. 115001, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yang J-C, Ji J, Hogle JM, and Larson DN, “Multiplexed plasmonic sensing based on small-dimension nanohole arrays and intensity interrogation,” Biosensors & bioelectronics, vol. 24, pp. 2334–2338, 12/13 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang J-C, Ji J, Hogle JM, and Larson DN, “Metallic Nanohole Arrays on Fluoropolymer Substrates as Small LabelFree Real-Time Bioprobes,” Nano Letters, vol. 8, pp. 2718–2724, 2008/09/10 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Spoto G and Minunni M, “Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging: What Next?,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, vol. 3, pp. 2682–2691, 2012/09/20 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cooper MA, “Optical biosensors in drug discovery,” Nat Rev Drug Discov, vol. 1, pp. 515–528, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Coskun AF, Cetin AE, Galarreta BC, Alvarez DA, Altug H, and Ozcan A, “Lensfree optofluidic plasmonic sensor for real-time and label-free monitoring of molecular binding events over a wide fieldof-view,” Sci. Rep, vol. 4, 10/27/online 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. “Lung Cancer Statistics,” In: Ahma A., Gadgee S. (eds) Lung Cancer and Personalized Medicine. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 893 2016. Springer, Cham. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PRM, Andreu Z, Bedina Zavec A, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, et al. , “Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions,” Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, vol. 4, p. 27066, 2015/01/01 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].El Andaloussi S, Mäger I, Breakefield XO, and Wood MJA, “Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities,” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 12, p. 347, 04/15/online 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tkach M and Théry C, “Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go,” Cell, vol. 164, pp. 1226–1232, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Azmi AS, Bao B, and Sarkar FH, “Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: a comprehensive review,” Cancer and Metastasis Reviews, vol. 32, pp. 623–642, 2013/12/01 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, Fernandez AF, Gammon ST, Kaye J, et al. , “Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer,” Nature, vol. 523, p. 177, 06/24/online 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Liu X, Wang P, Zhang C, Ma Z. “Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): A rising star in the era of precision medicine of lung cancer,” Oncotarget. vol. 8(30), pp. 50209–50220, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yamashita T, Kamada H, Kanasaki S, Maeda Y, Nagano K, Abe Y, et al. , “Epidermal growth factor receptor localized to exosome membranes as a possible biomarker for lung cancer diagnosis,” Die Pharmazie-An International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 68, pp. 969–973, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jakobsen KR, Paulsen BS, Bæk R, Varming K, Sorensen BS, and Jørgensen MM, “Exosomal proteins as potential diagnostic markers in advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma,” Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, vol. 4, p. 26659, 2015/01/01 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sandfeld-Paulsen B, AggerholmPedersen N, Bæk R, Jakobsen KR, Meldgaard P, Folkersen BH, et al. , “Exosomal proteins as prognostic biomar ers in non small cell lung cancer, Molecular Oncology, vol. 10, pp. 1595–1602, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]