Abstract

Although humans with X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) and the Hyp mouse, a murine homolog of XLH, are known to develop degenerative joint disease, the exact mechanism that drives the osteoarthritis (OA) phenotype remains unclear. Mice that overexpress high-molecular-weight fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 isoforms (HMWTg mice) phenocopy both XLH and Hyp, including OA with increased FGF23 production in bone and serum. Because HMWTg cartilage also has increased FGF23 and there is cross-talk between FGF23-Wnt/β-catenin signaling, the purpose of this study was to determine if OA observed in HMWTg mice is due to FGF23-mediated canonical Wnt signaling in chondrocytes, given that both pathways are implicated in OA pathogenesis. HMWTg OA joints had decreased Dkk1, Sost, and Lrp6 expression with increased Wnt5a, Wnt7b, Lrp5, Axin2, phospho-GSK3β, Lef1, and nuclear β-catenin, as indicated by immunohistochemistry or quantitative PCR analysis. Chondrocytes from HMWTg mice had enhanced alcian blue and alkaline phosphatase staining as well as increased FGF23, Adamts5, Il-1β, Wnt7b, Wnt16, and Wisp1 gene expression and phospho-GSK3β protein expression as indicated by Western blot, compared with chondrocytes of vector control and chondrocytes from mice overexpressing the low-molecular-weight isoform, which were protected from OA. Canonical Wnt inhibitor treatment rescued some of those parameters in HMWTg chondrocytes, seemingly delaying the initially accelerated chondrogenic differentiation. FGF23 neutralizing antibody treatment was able to partly ameliorate OA abnormalities in subchondral bone and reduce degradative/hypertrophic chondrogenic marker expression in HMWTg joints in vivo. These results demonstrate that osteoarthropathy of HMWTg is at least partially due to FGF23-modulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling in chondrocytes.

High-molecular-weight FGF2 isoforms enhance FGF23 expression, causing osteoarthritis via canonical Wnt signaling in murine cartilage.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic disabling joint disease, mainly of the knee, which affects millions of people and disturbs all areas of the joint, including the subchondral bone, meniscus, and synovium, but is primarily characterized by the degradation of articular cartilage (1, 2). This cartilage is comprised of unique chondrocytes that synthesize extracellular matrix components and a variety of catabolic and anabolic factors to maintain healthy cartilage homeostasis. When this balance is perturbed and various biochemical pathways are activated within chondrocytes, there is a breakdown of the extracellular matrix by degradative enzymes, inflammation occurs, and chondrocytes undergo dedifferentiation and hypertrophy, ultimately leading to OA (2, 3). Unfortunately, the molecular mechanisms that cause OA are not fully understood, and there is a crucial need to further study these biochemical pathways that contribute to the disease to identify therapeutic targets to effectively treat OA.

The Wnt signaling pathway has been a well-recognized regulator not only in skeletal and embryonic development, but also in cartilage homeostasis and the pathophysiology of OA (4, 5). Though there have been contradictory findings regarding either the activation or inhibition of Wnt signaling on joint homeostasis (6, 7), there are numerous studies that suggest that cartilage degradation is a result of excessive canonical Wnt signaling, which is initiated by binding to low-density lipoprotein receptor (LRP) 5 or 6, leading to stabilization and nuclear translocation of β-catenin, and transcription of its target genes, such as Wnt-induced signaling protein-1 (WISP1), which has been shown to increase OA cartilage in mice (7–11). Specifically, Wnt7b, an exclusively canonical ligand, was found to be upregulated in human OA cartilage (10), and Wnt16 and nuclear β-catenin expression was increased in OA cartilage with a decreased expression of Wnt inhibitors (9, 11). Also, human and mouse OA cartilage was found to have an upregulation of LRP5, and mice lacking Lrp5 were protected from experimental OA (8). Thus, aberrant canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling negatively impacts cartilage.

Interestingly, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23 is upregulated in human OA chondrocytes (12), and exogenous expression of FGF23 stimulates hypertrophy and increases FGFR1 production in chondrocytes (13, 14). Fibroblast growth factor signaling has been found to augment nuclear β-catenin levels by inactivating glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3β (15), and Wnt/β-catenin activity was shown to stimulate FGF23 promoter activity in osteoblasts (16). Together these studies imply that FGF23 and canonical Wnt signaling cooperatively may be contributing to OA. We previously published that mice that overexpress high-molecular-weight FGF2 isoforms (HMWTg mice) in osteoblastic lineage cells spontaneously develop signs of OA as early as 2 months of age, including increased degradative enzymes, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and FGF23 and FGFR1 expression in the cartilage, whereas mice that overexpress the low-molecular-weight FGF2 isoform (LMWTg mice) were protected from OA (17). HMWTg mice mimic subjects that have X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) in that they have decreased bone mineral density, rickets, osteomalacia, hypophosphatemia, osteoarthropathy, and elevated levels of FGF23, which are traits in which the HMWTg mice phenocopy Hyp mice (18), a murine homolog of XLH. Additionally, Wnt signaling components are enhanced in Hyp mice (16, 19). The aim of this study is to determine if the OA phenotype observed in HMWTg mice is due to increased FGF23 and canonical Wnt signaling in chondrocytes.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Connecticut Health Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee. We have previously described in detail the generation of HMWTg and vector (control) transgenic mice (18). HMWTg mice overexpress human high-molecular-weight (HMW) FGF2 isoforms in bone, using the Col3.6-HMW-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)–green fluorescent protein–sapphire (GFPsaph) construct in which a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) fragment of the previously generated construct, Col3.6-CAT-IRES-GFPsaph, was replaced with high-molecular-weight (HMW) isoforms of human FGF2 cDNA, thus allowing HMW and GFPsaph to be concurrently overexpressed from a single bicistronic mRNA. Vector mice overexpress the transgene cassette Col3.6-IRES/GFPsaph, without the additional FGF2 coding sequences. Col3.6-CAT-IRES-GFPsaph or Col3.6-IRES/GFPsaph construct inserts were released via digestion by AseI and AflII. Microinjections in the pronuclei of fertilized oocytes were performed at the Gene Targeting and Transgenic Facility at UCONN Health. To establish the individual transgenic mouse lines, founder mice of the F2 (FVBN) strain were mated with wild-type mice. Mice that overexpress the human low-molecular-weight (LMW) FGF2 isoform were generated using a similar method as described above (20). In vivo studies used male homozygous vector and HMWTg without antibody treatment and female homozygous vector and HMWTg mice for antibody treatment studies. Both male and female 5-day-old pups of vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg were used for all in vitro studies.

Histology

Following dissection, knees were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified using a 14% EDTA solution, processed for paraffin embedding in a frontal orientation, and cut into 7-μm alternate sections. The ImmunoCruz ABC Staining System (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) was used for all immunohistochemical staining. After sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, antigen retrieval was done by incubating sections with 10mM sodium citrate buffer for 10 minutes at 95°C. To reduce endogenous target, slides were blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in water for 15 minutes, then blocked for 1 hour with 10% serum, and incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used: goat anti-sclerostin (SOST) (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; AF1589; RRID: AB_2195345), rabbit anti-pLRP6 (1:100; Bioss, Woburn, MA; bs-3253R; RRID: AB_10858068), rabbit anti-pLRP5 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab203306; RRID: AB_2721918), goat anti-WNT5A (1:50; R&D Systems; AF645: RRID: AB_2288488), rabbit anti-WNT7B (1:100; GeneTex, Irvine, CA; GTX114881; RRID: AB_11172941), rabbit anti-pGSK3β (1:50; Abcam; ab75745; RRID: AB_1310290), rabbit anti–lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1; 1:50; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; AV32404; RRID: AB_1852782), rabbit anti–non-phospho β-catenin (1:50; Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA; 8814; RRID: AB_11127203), rabbit anti-MMP13 (1:100; Abcam; ab39012; RRID: AB_776416), and goat anti-MMP19 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc6840; RRID: AB_2144734). A negative control slide was used each time, which was incubated overnight with only blocking serum. Sections were then washed and incubated with the appropriate 1:200 biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes. Finally, slides were washed, developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories), and counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Quantitative analysis of DAB-positive vs total cells was performed using a web-based automated image analysis application (ImmunoRatio). Images were uploaded and analyzed as recommended by ImmunoRatio application from three images per sample, as described (21).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

For in vivo studies, following removal of skin and bulk muscle of the knee, total RNA was extracted from the entire joint, which included all components above the growth plate using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) (20). For real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR analysis, the RNA to cDNA EcoDry Premix Kit (Clontech Inc., Takara Bio, Mountain View, CA) was used to reverse transcribe the RNA to cDNA. iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and a MyiQ instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were used for quantitative PCR (qPCR). The relative change in mRNA level was normalized to the mRNA level of β-actin, which served as an internal reference for each sample. For in vitro studies, RNA was extracted from culture plates using TRIzol reagent and qPCR performed as described above. Additionally, mRNA was normalized to the β-actin mRNA level and expressed as the fold change relative to the appropriate vector group. Table 1 lists the primers, synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (CA) for the genes of interest.

Table 1.

Primers Used in Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | 5′-atggctggggtgttgaaggt-3′ | 5′-atctggcaccacaccttctacaa-3′ |

| Axin2 | 5′-aacctatgcccgtttcctcta-3′ | 5′-gagtgtaaagacttggtccacc-3′ |

| Sost | 5′-ggaatgatgccacagaggtcat-3′ | 5′-cccggttcatggtctggtt-3′ |

| Sostdc1 | 5′-actggatcggaggaggctatgg-3′ | 5′-tgtggctggactcgttgtgc-3′ |

| Dkk1 | 5′-gggagttctctatgagggcg-3′ | 5′-aagggtagggctggtagttg-3′ |

| Wisp1 | 5′-gtggacatccaactacacatcaa-3′ | 5′-aagttcgtggcctcctctg-3′ |

| Wnt5a | 5′-ctccttcgcccaggttgttatag-3′ | 5′-tgtcttcgcaccttctccaatg-3′ |

| Wnt7b | 5′-ttctggaggaccgcatgaa-3′ | 5′-ggtccagcaagttttggtggta-3′ |

| Wnt16 | 5′-agtgcaggcaacatgaccg-3′ | 5′-ccacatgccgtactggacatc-3′ |

| Wnt10b | 5′- ttctctcgggatttcttggattc-3′ | 5′- tgcacttccgcttcaggttttc-3′ |

| Lrp6 | 5′-ggtgtcaaagaagcctctgc-3′ | 5′-acctcaatgcgatttgttcc-3′ |

| Lef1 | 5′-gccaccgatgagatgatccc-3′ | 5′-ttgatgtcggctaagtcgcc-3′ |

| Mmp-13 | 5′-ctttggcttagaggtgactgg-3′ | 5′-aggcactccacatcttggttt-3′ |

| Mmp-9 | 5′-gcgtcgtgatccccacttac-3′ | 5′-caggccgaataggagcgtc-3′ |

| Adamts5 | 5′-cctgcccacccaatggtaaa-3′ | 5′-ccacatagtagcctgtgccc-3′ |

| Col10a1 | 5′-gggaccccaaggacctaaag-3′ | 5′-gcccaactagacctatctcacct-3′ |

| Col1a1 | 5′-ggtcctcgtggtgctgct-3′ | 5′-acctttgcccccttctttg-3′ |

| Fgf23 | 5′-acttgtcgcagaagcatc-3′ | 5′-gtgggcgaacagtgtagaa-3′ |

| Fgf18 | 5′-aaggagtgcgtgttcattgag-3′ | 5′-agcccacataccaaccagagt-3′ |

| FGFR3 | 5′-ccggctgacacttggtaag-3′ | 5′-cttgtcgatgccaatagcttct-3′ |

| FGFR3c | 5′-gttctctctttgtagactgc-3′ | 5′-agtacctggcagcacca-3′ |

| IL-1β | 5′-gcaactgttcctgaactcaact-3′ | 5′-atcttttggggtccgtcaact-3′ |

| Ihh | 5′-ggcgctacgaaggcaagat-3′ | 5′-cttgaagatgatgtcgggattgt-3′ |

| Sox9 | 5′-agtacccgcatctgcacaac-3′ | 5′-acgaagggtctcttctcgct-3′ |

| Nkx3.2 | 5′-aaagtggccgtcaaggtgct-3′ | 5′-agcccgggagacagtagtaa-3′ |

Radiology and microcomputed tomography analysis

Digital x-rays of excised knee joints taken in the frontal plane were captured under consistent conditions (26 kV at 6-second exposure) using a SYSTEM MX 20 (Faxitron X-Ray Corporation, Tucson, AZ). Imaging of knee architecture was performed using ex vivo microcomputed tomography (μCT40; ScanCo Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The following morphometric parameters of the region of subchondral trabecular bone of the epiphysis in the femur and tibia were analyzed by three-dimensional (3D) microcomputed tomography: bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), and trabecular number (Tb.N).

FGF23 neutralizing antibody treatment

Female HMWTg mice were treated with a rat anti-rat FGF23 neutralizing antibody (FGF23Ab) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight or control IgG (rat-anti-NGFPb-3F8-raIgG2a) by intraperitoneal injection twice a week, beginning at 8 weeks of age for 6 weeks. This dosage was previously established in our laboratory in a pilot experiment. Initially, vector mice were treated with control IgG (vehicle; Amgen) only, but an additional experiment that included vector mice treated with FGF23Ab (as an added control group) or control IgG treatment was performed by initiating injections twice a week at 3 weeks of age for 6 weeks and combined into the study. Vector + vehicle, HMWTg + vehicle, and HMWTg + FGF23Ab groups were n = 4, and the vector + vehicle group was n = 3. Mice were euthanized by CO2, and knees were collected. Sections were obtained by methods described, and Safranin-O staining using 0.1% aqueous Safranin-O with 0.02% aqueous Fast Green and Weigert Iron Hematoxylin Counterstain was performed.

Chondrocyte culture

Chondrocytes were dissected from ∼5-day-old male and female vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg pups from the femoral head, femoral condyles, and tibial plateau using a dissecting Zeiss microscope. Cartilage was collected in high-glucose DMEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and digested in 0.25% trypsin (Life Technologies) for 30 minutes and then incubated with 500 U/mL of collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) for 3 hours at 37°C. Cells were collected and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies) (22).The cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2, incubated for 7 days with media changes every other day, fixed, and stained with alcian blue (3% in acetic acid, pH 2.5) (Poly Scientific, Bay Shore, NY) or Vector Blue Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured with a Nikon TS100 microscope interfaced with SPOT software and quantitatively analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) using methodology as previously described (23, 24) and presented as percentage-positive area (n = 3 to 4 independent experiments). For inhibitor experiments, chondrocyte culture medium was supplemented with 10 µM IWR-1 endo (IWR-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide on day 5 when cells are ∼70% confluent for 48 hours.

Western blot analysis

Protein was extracted from primary articular chondrocytes on day 7 in culture using 1× radioimmune precipitation buffer (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), and protein concentration was assayed with bicinchoninic acid assay protein assay reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following SDS-PAGE on mini protean gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), proteins were transferred to Immun-Blot PVD Membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were probed using antibodies, including a rabbit polyclonal antiphospho-Gsk3β (Ser9; 9336; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.; RRID: AB_331405), a rabbit monoclonal anti-Gsk3β (9315; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.; RRID: AB_490890), a rabbit polyclonal anti-AXIN2 (SAB3500619; Sigma-Aldrich; RRID: AB_10900607), a rabbit monoclonal anti–non-phospho (active) β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr31; 8814; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.; RRID: AB_11127203), a rabbit polyclonal β-catenin (sc7199; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; RRID: AB_634603), a monoclonal β-actin (sc47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; RRID: AB_2714189), and a goat secondary antibody against rabbit (7074; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.; RRID: AB_2099233). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using Supersignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific) and autoradiography film (Laboratory Scientific Inc., Highlands, NJ) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. ImageJ was used to densitometrically quantify band densities.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± SD. Student t test was used to analyze differences between groups. Differences were considered significant at P values <0.05.

Results

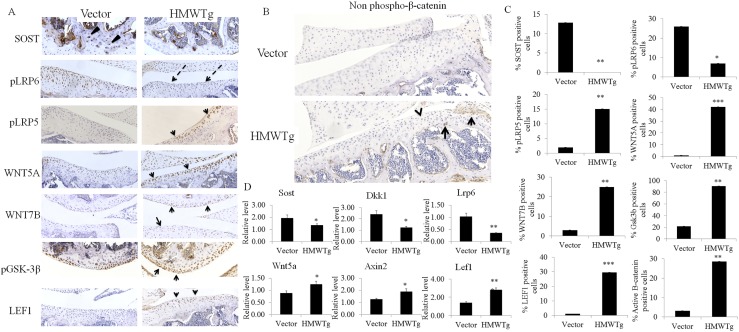

Expression of Wnt signaling components in vector and HMWTg joints

Previously, we have shown that HMWTg mice develop osteoarthropathy as early as 2 months of age, and to determine if Wnt signaling may be contributing to this phenotype, we examined 2-month-old male vector and HMWTg knees for protein and gene expression of components of the Wnt signaling pathway (n = 3 per group). SOST, a Wnt inhibitor, was not present in HMWTg knees; however, vector mice had SOST expression in the subchondral bone. Phosphorylated LRP6 receptor protein was decreased in HMWTg articular cartilage, compared with vector cartilage, yet phosphorylated LRP5 was strongly expressed in HMWTg cartilage compared with vector. Ligands WNT5A and WNT7B were greatly increased in HMWTg cartilage compared with vector. Also, phosphorylated inactive GSK3β and LEF1, both downstream components of canonical Wnt signaling, had strong expression in HMWTg compared with vector articular cartilage (Fig. 1A). To determine if specifically canonical Wnt signaling, in which β-catenin does not become degraded, was upregulated in HMWTg joints, we examined nonphosphorylated β-catenin by immunohistochemistry, and expression was only present in HMWTg cartilage and not in vector knees (Fig. 1B). All immunohistochemical data were quantified that showed significant differences between vector and HMTWTg knees (Fig. 1C). We then examined gene expression in whole joints from 2-month-old vector and HMWTg mice (n=7 to 8 per group) and similarly found that the Wnt inhibitors Sost and Dickkopf WNT Signaling Pathway Inhibitor (Dkk1) and receptor Lrp6 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in HMWTg compared with vector. Also, Wnt5a, Axin2, and Lef1 gene expression was significantly increased in HMWTg joints compared with the vector control (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Expression of components of the Wnt pathway in knees of 2-month-old male vector and HMWTg mice. (A) Representative immunohistochemical staining shows no protein expression of SOST in the subchondral bone of HMWTg compared with vector (arrowheads) and decreased phospho-LRP6 expression in articular cartilage (dashed arrows). Arrows indicate increased expression of phospho-LRP5, WNT5A, WNT7B, phospho-GSK3β, and LEF1 in HMWTg cartilage compared with vector. Magnification, ×10; n = 3 per group. (B) Representative images show evidence of active β-catenin protein expression in HMWTg cartilage (arrows). Magnification, ×20; n = 3 per group. (C) Quantitative data (A and B) of DAB-positive cells/total cells using ImmunoRatio analyses; n = 3 per group. (D) qPCR analysis shows decreased Sost, Dkk1, and Lrp6 and increased Wnt5a, Axin2, and Lef1 mRNA levels of HMWTg joints compared with vector. Values are the means ± SD; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n = 7 to 8 per group.

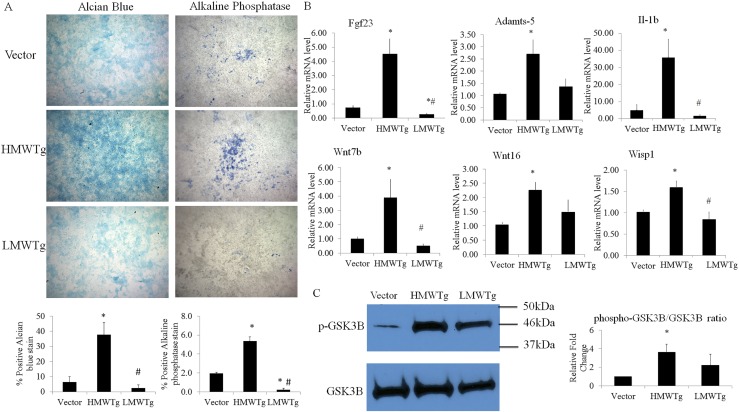

Characterization of immature murine articular chondrocytes from vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg mice

To be able to study more directly how the chondrocyte phenotype and Wnt/β-catenin signaling is modulated in vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg mice, we microsurgically dissected articular cartilage from postnatal mice (one litter, approximately seven pups per genotype per experiment) and studied in vitro in monolayer. On day 7 in culture, chondrocytes reached confluence and were fixed and stained for alcian blue. From four independent experiments, chondrocytes from LMWTg consistently had slightly less blue staining, whereas HMWTg chondrocytes had more robust staining, indicating increased glycosaminoglycan content compared with vector or LMWTg (Fig. 2A). Similarly, alkaline phosphatase staining was markedly less in LMWTg chondrocytes, and staining in HMWTg chondrocytes was significantly increased, indicating enhanced hypertrophic differentiation (Fig. 2A). Next, RNA was isolated from cultures on day 7, and qPCR analysis was used to determine expression levels of genes involved in FGF and Wnt signaling and OA pathogenesis. Of importance, Fgf23, Adamts5, Interleukin 1 β, Wnt7b, Wnt16, and Wisp1 were significantly increased in HMWTg chondrocytes. Also, FGF23, Interleukin 1 β, and Wnt7b were significantly decreased in LMWTg chondrocytes (Fig. 2B). Table 2 lists any genes that had significant difference in mRNA level between genotypes, and it was determined that HMW chondrocytes had increased Fgf18 levels, but not as elevated as LMW chondrocytes. Also, FGFR3 expression was decreased in HMW chondrocytes, but FGFR3c was increased in HMW compared with vector. Degradative enzyme Mmp9 expression level was significantly increased in HMW compared with LMW. Transcription factors sex-determining region Y box 9 (Sox9), ColX, Indian hedgehog (Ihh), and sclerostin domain containing 1 (Sostdc1) expression was significantly less in LMW compared with vector. Whereas Col1 levels were increased in HMW, NK3 Homeobox 2 (Nkx3.2) and Wnt10b were decreased compared with vector. To further determine if Wnt signaling is modulated in these chondrocytes, we examined phospho-GSK3β protein expression by Western blot. From three independent experiments, it was determined that HMWTg had a statistically significant increase in phospho-GSK3β (Fig. 2C), indicating that there is more inactive GSK3β, allowing less degradation of β-catenin and subsequent enhanced transcription of β-catenin target genes.

Figure 2.

Basal characterization of primary immature murine articular chondrocytes cultured for 7 days. (A) Alcian blue staining shows enhanced matrix proteoglycan production by HMWTg compared with vector and LMWTg. Alkaline phosphatase staining was increased in HMWTg chondrocytes compared with vector and LMWTg. The data are representative of four independent experiments. Magnification, ×4. Graphical representation of alcian blue– or alkaline phosphatase–stained cells; percentage of area staining was calculated using ImageJ software. (B) mRNA expression revealed modulated gene expression between genotypes by qPCR analysis. (C) Phospho-GSK3β protein expression was significantly higher in HMWTg chondrocytes compared with vector. The mRNA expression and protein levels were expressed as relative (fold changes) to the expression of the vector group. Values are the means ± SD for three independent experiments. *Compared with vector (P < 0.05); #Compared with HMWTg (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Relative Fold Change of Gene Expression of Vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg Immature Murine Articular Chondrocytes

| Gene | Vector | HMWTg | LMWTg | Vector vs HMWTg P Value | Vector vs LMWTg P Value | HMWTg vs LMWTg P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fgf18 | 1.02 ± 0.08 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 1.94 ± 0.70 | 0.044 | 0.009 | 0.034 |

| FGFR3 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.21 | 1.35 ± 1.25 | 0.000 | 0.477 | 0.126 |

| FGFR3c | 1.10 ± 0.13 | 1.48 ± 0.30 | 0.98 ± 1.00 | 0.017 | 0.766 | 0.263 |

| Mmp9 | 1.02 ± 0.10 | 2.57 ± 1.98 | 0.65 ± 0.43 | 0.086 | 0.067 | 0.043 |

| Sox9 | 0.99 ± 0.08 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | 0.72 ± 0.27 | 0.076 | 0.041 | 0.524 |

| ColX | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.40 | 0.83 ± 0.22 | 0.071 | 0.049 | 0.502 |

| Col1 | 0.97 ± 0.11 | 1.93 ± 0.52 | 1.80 ± 0.77 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.751 |

| Ihh | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 1.24 ± 1.07 | 0.54 ± 0.26 | 0.571 | 0.002 | 0.150 |

| Nkx3.2 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.12 | 0.90 ± 0.21 | 0.000 | 0.251 | 0.012 |

| Wnt10b | 0.96 ± 0.18 | 0.70 ± 0.17 | 0.93 ± 0.34 | 0.030 | 0.885 | 0.160 |

| Sostdc1 | 1.09 ± 0.24 | 0.96 ± 0.64 | 0.51 ± 0.26 | 0.642 | 0.002 | 0.141 |

| Dkk1 | 1.33 ± 0.37 | 2.50 ± 1.26 | 1.79 ± 0.32 | 0.056 | 0.044 | 0.216 |

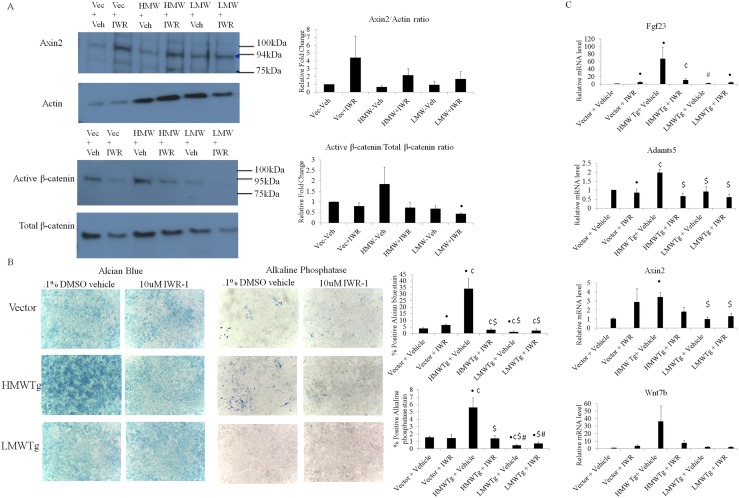

Inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin on chondrocyte homeostasis

To determine if canonical Wnt signaling is contributing to the enhanced chondrocyte differentiation and hypertrophy and OA in HMWTg cells, we treated cultures with IWR-1, a potent Wnt inhibitor that stabilizes Axin2, a member of the β-catenin destruction complex, ultimately leading to the degradation of β-catenin (25). This stabilization of Axin2 was confirmed by increased Axin2 protein expression by Western blot in vector, HMWTg, and LMWTg groups compared with their vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3A). Consequently, active β-catenin vs total β-catenin was decreased after IWR-1 treatment of all genotypes as determined by Western blot, and the initial increase in active β-catenin in HMWTg vehicle treated compared with vector and LMWTg was observed (Fig. 3A). IWR-1 treatment of chondrocytes caused a significant decrease in both alcian blue and alkaline phosphatase staining in HMWTg cultures, which was similar to that of vector and LMWTg vehicle-treated groups. However, IWR-1 treatment did not diminish the staining in vector or LMWTg cultures (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, IWR-1 markedly reduced mRNA expression of the initially high Fgf23 expression in HMWTg chondrocytes, yet somewhat increased expression in vector and LMWTg. Adamts5 elevated expression was rescued in HMWTg after IWR-1 treatment. Though Axin2 gene expression was significantly increased in HMWTg vehicle-treated chondrocytes compared with the vector vehicle treated, mRNA levels were not significantly altered following IWR-1 treatment compared with each group’s vehicle-treated controls. qPCR also showed enhanced Wnt7b expression in HMWTg, which was reduced after IWR-1 treatment (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Effect of IWR-1 on primary articular chondrocytes from HMWTg, LMWTg, and vector mice. (A) Western blots showed increased Axin2 protein expression after treatment with IWR-1 for 48 hours. Active β-catenin protein expression was greatest in the HMWTg-vehicle–treated group and was decreased after IWR-1 treatment in all genotypes. Statistical analysis of Western blots of Axin2/Actin and active β-catenin/total β-catenin from three independent experiments is represented as the means ± SD. (B) Alcian blue staining showed a decrease in matrix proteoglycan production after IWR-1 treatment in HMWTg chondrocytes compared with vehicle treated, whereas vector– and LMWTg IWR-1–treated cultures retained their vehicle-treated phenotype. Following IWR-1 treatment, alkaline phosphatase staining was decreased in HMWTg with no effect on vector and LMWTg chondrocytes. Magnification, ×4. Graphical representation of alcian blue– or alkaline phosphatase–stained cells; percentage of area staining was calculated using ImageJ software. (C) IWR-1 treatment modulated mRNA expression and rescued some gene expression in HMWTg cultures as indicated in the qPCR analysis. The mRNA expression is expressed as relative (fold changes) to the expression of the vector group. Values are the means ± SD for three independent experiments. •Compared with vector + vehicle (P < 0.05); ¢Compared with vector + IWR-1 (P < 0.05); $Compared with HMWTg + vehicle (P < 0.05); #Compared with HMWTg + IWR-1 (P < 0.05). DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; Vec, vector; Veh, vehicle.

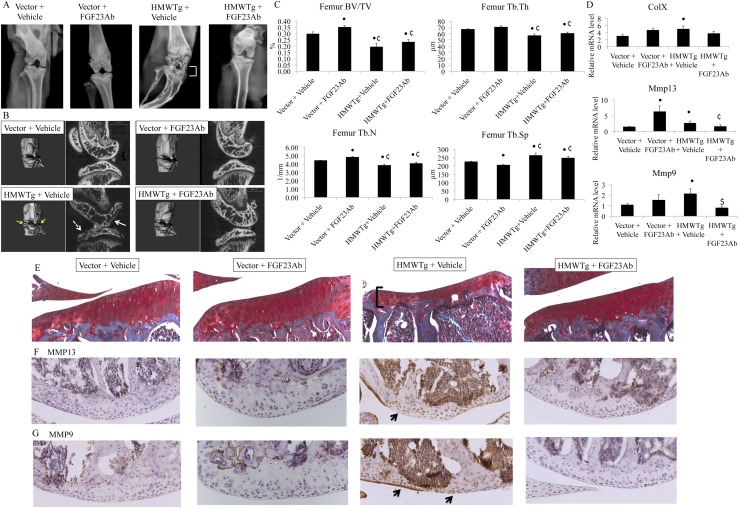

Effects of long-term FGF23Ab treatment on joint homeostasis in vector and HMWTg

Because HMWTg knees and chondrocytes have an OA phenotype and increased FGF23 expression, and FGF23 has been found to promote chondrocyte hypertrophy and differentiation (14), we assessed whether neutralization of FGF23 could rescue the OA phenotype in HMWTg mice. As shown by digital radiography, the flattened tibial plateau and narrowing of the joint space in the HMWTg vehicle-treated group was rescued following FGF23Ab treatment (Fig. 4A). 3D renderings show abnormal contour and erosion of the subchondral surface in the HMWTg vehicle-treated group, whereas FGF23Ab treatment resulted in a phenotype resembling that of the vector groups (Fig. 4B). Sagittal microCT images reveal irregular shape and thinning of the subchondral bone with decreased trabeculae number and thickness within the epiphyses of HMWTg vehicle-treated knees, which was rescued following FGF23Ab injections (Fig. 4B). Specifically, HMWTg vehicle-treated femoral epiphyses had altered trabecular architecture indicative of early OA, and 3D morphometric parameters calculated from microCT results of the epiphyses indicated increased BV/TV and Tb.Th and Tb.N and decreased Tb.Sp, compared with vector vehicle-treated epiphyses, which were partially normalized with FGF23Ab treatment (Fig. 4C). Also, increased hypertrophic OA gene markers found in mRNA from HMWTg vehicle-treated joints showed rescue after FGF23Ab treatment, which included ColX, Mmp13, and Mmp9 (Fig. 4D). Protein expression of MMP13 and MMP9 was strongly expressed in HMWTg vehicle-treated cartilage, but was not present in either vector group or HMWTg FGF23Ab-treated mice (Fig. 4F and 4G). Articular cartilage thickness was decreased in HMWTg vehicle-treated mice, similar to what was observed in our initial study (17), and was then restored to the cartilage thickness of vector mice in the HMWTg FGF23Ab-treated group (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Effect of FGF23Ab on joints of HMWTg and vector female mice. (A) Digital radiographs show flattening of the tibial plateau and joint space narrowing (bracket) in vehicle-treated HMWTg mice, where FGF23Ab-treated HMWTg knees have a similar phenotype to both vector control groups. n = 3 to 4 per group. (B) 3D reconstructive images show pitting and erosion of the surface (yellow arrows) in the HMWTg + vehicle knees compared with the smooth contour of all other groups. High-resolution microCT sagittal images of HMWTg + vehicle display flattened tibia (dashed arrow), thinning and abnormal morphology of subchondral bone (white arrow), and decreased Tb.N and Tb.Th in the femoral and tibial epiphyses. HMWTg + Fgf23Ab phenotype resembles that of vector + vehicle and vector + Fgf23Ab groups. n = 3 to 4 per group. (C) 3D morphometric parameters revealed a significant decrease in BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Th and increase in Tb.Sp in HMWTg + vehicle femoral epiphyses compared with the vector + vehicle group, whereas there is some rescue in the HMWTg + FGF23Ab knees. n = 3 to 4 per group. (D) qPCR analysis of mRNA taken from the knees shows increased expression of ColX, Mmp13, and Mmp9 in HMWTg + vehicle mice, with some rescue in the HMWTg + FGF23Ab group. n = 3 to 4 per group. (E) Safranin-O staining shows decreased articular cartilage thickness (bracket) in HMWTg + vehicle, which is restored in HMWTg + FGF23Ab. n = 3 per group. (F and G) Representative immunohistochemical staining shows increased MMP13 and MMP9 expression (arrows) in femoral articular cartilage of HMWTg + vehicle, which is decreased in HMWTg + FGF23Ab. n = 3 per group. Values are the means ± SD. •Compared with vector + vehicle (P < 0.05); ¢Compared with vector + FGF23Ab (P < 0.05); $Compared with HMWTg + vehicle (P < 0.05); #Compared with HMWTg + FGF23Ab (P < 0.05).

Discussion

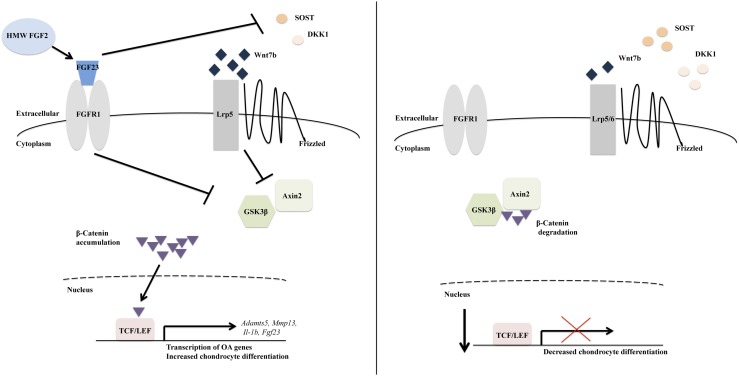

This study examined modulation of FGF23 and canonical Wnt signaling in chondrocytes obtained from mice that overexpress the HMW isoforms of FGF2 and develop OA. We found the following: (1) joints of HMWTg mice, which have elevated FGF23 expression, had decreased Sost, Dkk1, and Lrp6 expression and increased Wnt7b, Wnt5a, Lrp5, Axin2, Gsk3β, Lef1, and nuclear β-catenin levels; (2) chondrocytes of HMWTg mice had accelerated differentiation and increased Fgf23, Adamts5, Il-1β, Wnt7b, Wnt16, Wisp1, and phospho-Gsk3β; (3) inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling rescued hypertrophy and Fgf23, Adamts5, and Wnt7b levels in HMWTg chondrocytes; and (5) the OA phenotype in HMWTg mice can be partially rescued by neutralizing FGF23Ab treatment in vivo. Collectively, these data suggest that FGF23 modulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling promoting chondrocyte differentiation, resulting in OA (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic model in which HMW FGF2-mediated FGF23 stimulation of chondrocyte differentiation and OA is partially through modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Overexpression of HMW FGF2 enhances FGF23 expression, which results in enhanced Wnt7b and phospho-Lrp5 and reduced Sost and Dkk1 expression. Increased inactive phosphorylated Gsk3β and Axin2 allow β-catenin to accumulate and be translocated to the nucleus, where it binds lymphoid enhancer factor/T-cell factor (LEF/TCF)-promoting transcription of OA and chondrocyte hypertrophic genes. When HMW FGF2 is not overexpressed, there is less FGF23 expression, resulting in reduced Wnt7b and increased Sost and Dkk1 expression, ultimately leading to reduced Wnt/β-catenin signaling and less chondrocyte differentiation.

Disruption of cartilage homeostasis is a primary reason of OA pathogenesis and is initiated by varying physical or genetic factors, leading to an imbalance of anabolic and catabolic factors, resulting in modulation of various biochemical pathways (3). Although we have previously published that HMWTg mice phenocopy both Hyp mouse and XLH and spontaneously develop degenerative joint disease, the molecular mechanism driving this OA phenotype was unclear (17); however, in this study we show that FGF23 is a catabolic regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling-mediated OA cartilage destruction. In vivo, we observed increased FGF23 and FGFR1 expression in HMWTg cartilage (17), and it is well established that FGF23 stimulates hypertrophy and signaling through FGFR1 leads to a cascade of events that are catabolic in articular chondrocytes (26). Although there is evidence that suggests FGF23 requires Klotho as a coreceptor for FGFR1, we found that there was no difference in Klotho expression between HMWTg and vector cartilage in vivo (data not shown), implying that FGF23 signals through FGFR1 independent of Klotho, similar to that observed in a previous study (13). Also, FGFR signaling has been shown to increase Wnt/β-catenin signaling in chondrocytes (27). Though Wnt signaling can have differing effects on cartilage homeostasis (6, 7), our findings are consistent with its negative role. We found that inhibitors Sost and Dkk1 were decreased in HMWTg joints, essentially allowing activation of the Wnt pathway, and similarly it was found that increased Sost and Dkk1 levels protect against cartilage degradation in OA in mice (28, 29). Interestingly, we observed an increase in LRP5 with a decrease in LRP6 in HMWTg, which further strengthens the argument that these receptors can have distinct functions, and that LRP5 (but not LRP6) is essential for Wnt-induced cartilage destruction by regulating production of MMPs (8), as we have also shown increased MMPs expression in vivo and in vitro.

Although aberrant noncanonical Wnt signaling can contribute to OA (5, 30) and we observed increased Wnt5a expression in HMWTg, which is most often associated with the noncanonical pathway, there is evidence that suggests that Wnt5a activates the canonical pathway in the presence of LRP5 (31), which was also increased in our study. Furthermore, we observed increased Wnt7b expression in HMWTg chondrocytes, which is an exclusively canonical ligand (10), increased inactivation of Gsk3β, and increased LEF1, Wisp1, and nuclear β-catenin, which indicates that β-catenin is stabilized and translocated to the nucleus, which is due to enhanced canonical signaling.

Because various areas within an osteoarthritic joint contribute to the disease, it is of great importance that we were able to identify the articular chondrocyte as the component of the knee that may be responsible for the pathogenesis of OA observed in HMWTg mice. Even though in the Hyp mouse [which has increased Wnt signaling in varying tissues (16, 19)] it was determined that cellular changes occur within articular cartilage that contribute to the osteoarthropathy, these mice and humans with XLH also develop OA-like changes in the subchondral bone and tendons (32), so it was unclear what tissue was driving the phenotype. Isolating articular chondrocytes from pups that were only 5 days old and growing for just 7 days in undifferentiating media mimicked the in vivo results of HMWTg cartilage, which included increased FGF23/catabolic factor expression, mineralization, and chondrogenic hypertrophy (17). Firstly, alcian blue and alkaline phosphatase (mineralization) staining was strongest in HMWTg and lowest in LMWTg cultures, indicating that HMWTg chondrocytes have accelerated chondrogenic differentiation. Col1 was statistically significantly increased in HMWTg cultures and ColX was decreased in LMWTg cultures, which are markers for fully differentiated chondrocytes (33). Also, LMWTg cultures had a significant reduction in Sox 9, which acts further at each stage in chondrogenic differentiation (34), and Ihh, which simulates chondrogenic cell differentiation (35), whereas HMWTg cultures had a decrease in Nkx3.2, which has been found to decrease as chondrocytes mature and become more hypertrophic (36).

Although FGFR3c was increased in HMWTg cultures, total FGFR3 was significantly decreased, which is the primary receptor of FGF18 (which was greatly increased in LMWTg) and downstream signaling promotes anabolic activity in chondrocytes (37). Just as we had previously observed in vivo, HMWTg chondrocytes are unable to maintain their normally quiescent nature, resulting in rapid chondrogenesis, whereas LMWTg chondrocytes appear to have slower differentiation potential resulting in protection from OA. Further studies will be needed to fully elucidate the mechanism by which the LMW FGF2 isoform confers a chondroprotective effect.

The OA phenotype in HMWTg but not LMWTg chondrocytes is due to enhanced canonical Wnt signaling mediated by FGF23 because, in addition to increased FGF23 mRNA levels, HMWTg chondrocytes had increased expression of other components of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Once the cells were treated with a canonical Wnt inhibitor, IWR-1, which stabilizes Axin2, allowing more degradation of cytoplasmic β-catenin, the hypertrophic phenotype was rescued in HMWTg chondrocytes. Also, Adamts5 expression was decreased to levels found in vector or LMWTg chondrocytes following treatment in HMWTg cultures. Interestingly, FGF23 and Wnt7b elevated expression in HMWTg chondrocytes was markedly reduced after IWR-1 treatment. This decrease in FGF23 expression may be due to inhibition of active β-catenin, which has been found to enhance FGF23 promoter activity (16). Similarly, in the presence of higher levels of FGF23, we showed there was increased Wnt7b expression, so if FGF23 is unable to be transcribed, we would expect to see a decrease in Wnt7 levels. However, future studies are necessary to determine how FGF23 signaling regulates Wnt7b expression.

Additionally, this study identified a potential therapeutic approach to partially rescue osteoarthropathy in HMWTg mice by long-term treatment with a neutralizing FGF23Ab, which has previously been reported to ameliorate rickets, osteomalacia, and hypophosphatemia in the Hyp mouse (38) and human subjects with XLH (39). This is a unique finding in that there are no disease-modifying drugs to treat degenerative joint disease, and the effect of FGF23Ab treatment on the OA phenotype in the earlier studies was not examined (38, 39). Specifically, the microarchitecture of the subchondral bone was able to be restored to that of the vector control after FGF23Ab treatment. Notably, ColX and MMP expression was reduced in HMWTg + FGF23Ab–treated knees, which indicates that neutralizing FGF23 is restoring chondrocyte function, because these degradative/hypertrophic markers are expressed by osteoarthritic articular cartilage, as was observed by immunohistochemistry in the HMWTg + vector group. The rescue of cartilage thickness also indicates the impact of the antibody on chondrocytes.

Herein we provide evidence suggesting that FGF23 catabolically influences OA pathophysiology through canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in chondrocytes. These results provide insight into the role of FGF23 in the pathogenesis of cartilage degradation in the context of XLH and identify Wnt/β-catenin FGF23-mediated signaling as a candidate pathway to be targeted in the treatment or prevention of OA.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DK098566 and AR072985-05A1 (to M.M.H.) and National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Training Grant T90DE021989 (to P.M.B.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 3D

three-dimensional

- ADAMTS

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs

- BV/TV

bone volume/tissue volume

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- DAB

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGF23Ab

fibroblast growth factor 23 neutralizing antibody

- GFPsaph

green fluorescent protein–sapphire

- GSK

glycogen synthase kinase

- HMW

high-molecular-weight

- HMWTg mice

mice that overexpress high-molecular-weight fibroblast growth factor 2 isoforms

- Ihh

Indian hedgehog

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- IWR-1

IWR-1-endo

- LEF1

lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1

- LMW

low-molecular-weight

- LMWTg mice

mice that overexpress the low-molecular-weight fibroblast growth factor 2 isoform

- LRP

low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- Nkx3.2

NK3 Homeobox 2

- OA

osteoarthritis

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- SOST

sclerostin

- Sostdc1

sclerostin domain containing 1

- Sox9

sex-determining region Y box 9

- Tb.N

trabecular number

- Tb.Sp

trabecular spacing

- Tb.Th

trabecular thickness

- WISP1

Wnt-induced signaling protein-1

- XLH

X-linked hypophosphatemia

References

- 1. Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2(2):205–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005;365(9463):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hashimoto M, Nakasa T, Hikata T, Asahara H. Molecular network of cartilage homeostasis and osteoarthritis. Med Res Rev. 2008;28(3):464–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ma B, Landman EB, Miclea RL, Wit JM, Robanus-Maandag EC, Post JN, Karperien M. WNT signaling and cartilage: of mice and men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92(5):399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chun JS, Oh H, Yang S, Park M. Wnt signaling in cartilage development and degeneration. BMB Rep. 2008;41(7):485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sen M, Lauterbach K, El-Gabalawy H, Firestein GS, Corr M, Carson DA. Expression and function of wingless and frizzled homologs in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(6):2791–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu M, Chen M, Zuscik M, Wu Q, Wang YJ, Rosier RN, O’Keefe RJ, Chen D. Inhibition of β-catenin signaling in articular chondrocytes results in articular cartilage destruction. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):2053–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shin Y, Huh YH, Kim K, Kim S, Park KH, Koh JT, Chun JS, Ryu JH. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 governs Wnt-mediated osteoarthritic cartilage destruction. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dell’accio F, De Bari C, Eltawil NM, Vanhummelen P, Pitzalis C. Identification of the molecular response of articular cartilage to injury, by microarray screening: Wnt-16 expression and signaling after injury and in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1410–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakamura Y, Nawata M, Wakitani S. Expression profiles and functional analyses of Wnt-related genes in human joint disorders. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(1):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blom AB, Brockbank SM, van Lent PL, van Beuningen HM, Geurts J, Takahashi N, van der Kraan PM, van de Loo FA, Schreurs BW, Clements K, Newham P, van den Berg WB. Involvement of the Wnt signaling pathway in experimental and human osteoarthritis: prominent role of Wnt-induced signaling protein 1. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(2):501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Orfanidou T, Iliopoulos D, Malizos KN, Tsezou A. Involvement of SOX-9 and FGF-23 in RUNX-2 regulation in osteoarthritic chondrocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9b, 9B):3186–3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bianchi A, Guibert M, Cailotto F, Gasser A, Presle N, Mainard D, Netter P, Kempf H, Jouzeau JY, Reboul P. Fibroblast growth factor 23 drives MMP13 expression in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes in a Klotho-independent manner. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(11):1961–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guibert M, Gasser A, Kempf H, Bianchi A. Fibroblast-growth factor 23 promotes terminal differentiation of ATDC5 cells. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holnthoner W, Pillinger M, Gröger M, Wolff K, Ashton AW, Albanese C, Neumeister P, Pestell RG, Petzelbauer P. Fibroblast growth factor-2 induces Lef/Tcf-dependent transcription in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(48):45847–45853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu S, Tang W, Fang J, Ren J, Li H, Xiao Z, Quarles LD. Novel regulators of Fgf23 expression and mineralization in Hyp bone. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(9):1505–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meo Burt P, Xiao L, Dealy C, Fisher MC, Hurley MM. FGF2 high molecular weight isoforms contribute to osteoarthropathy in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(12):4602–4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiao L, Naganawa T, Lorenzo J, Carpenter TO, Coffin JD, Hurley MM. Nuclear isoforms of fibroblast growth factor 2 are novel inducers of hypophosphatemia via modulation of FGF23 and KLOTHO. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(4):2834–2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uchihashi K, Nakatani T, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, He X, Razzaque MS. FGF23-Induced Hypophosphatemia Persists in Hyp Mice Deficient in the WNT Coreceptor Lrp6.. Basel, Switzerland: Karger Publishers; 2013:124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiao L, Liu P, Li X, Doetschman T, Coffin JD, Drissi H, Hurley MM. Exported 18-kDa isoform of fibroblast growth factor-2 is a critical determinant of bone mass in mice. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(5):3170–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tuominen VJ, Ruotoistenmäki S, Viitanen A, Jumppanen M, Isola J. ImmunoRatio: a publicly available web application for quantitative image analysis of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and Ki-67. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(4):R56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zanotti S, Canalis E. Interleukin 6 mediates selected effects of Notch in chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(11):1766–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gutiérrez ML, Guevara J, Barrera LA. Semi-automatic grading system in histologic and immunohistochemistry analysis to evaluate in vitro chondrogenesis. Univ Sci. 2012;17(2):167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhou FY, Wei AQ, Shen B, Williams L, Diwan AD. Cartilage derived morphogenetic protein-2 induces cell migration and its chondrogenic potential in C28/I2 cells. Int J Spine Surg. 2015;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, Roth MG, Amatruda JF, Chen C, Lum L. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(2):100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yan D, Chen D, Cool SM, van Wijnen AJ, Mikecz K, Murphy G, Im HJ. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is principally responsible for fibroblast growth factor 2-induced catabolic activities in human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(4):R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27. Buchtova M, Oralova V, Aklian A, Masek J, Vesela I, Ouyang Z, Obadalova T, Konecna Z, Spoustova T, Pospisilova T, Matula P, Varecha M, Balek L, Gudernova I, Jelinkova I, Duran I, Cervenkova I, Murakami S, Kozubik A, Dvorak P, Bryja V, Krejci P. Fibroblast growth factor and canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cooperate in suppression of chondrocyte differentiation in experimental models of FGFR signaling in cartilage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(5):839–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan BY, Fuller ES, Russell AK, Smith SM, Smith MM, Jackson MT, Cake MA, Read RA, Bateman JF, Sambrook PN, Little CB. Increased chondrocyte sclerostin may protect against cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):874–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oh H, Chun CH, Chun JS. Dkk-1 expression in chondrocytes inhibits experimental osteoarthritic cartilage destruction in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2568–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Y, Pizzute T, Pei M. A review of crosstalk between MAPK and Wnt signals and its impact on cartilage regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;358(3):633–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mikels AJ, Nusse R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits β-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(4):e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang G, Vanhouten J, Macica CM. An atypical degenerative osteoarthropathy in Hyp mice is characterized by a loss in the mineralized zone of articular cartilage. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89(2):151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakajima M, Negishi Y, Tanaka H, Kawashima K. p21(Cip-1/SDI-1/WAF-1) expression via the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in insulin-induced chondrogenic differentiation of ATDC5 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320(4):1069–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22(1):85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Nakamura T, Aikawa T, Higuchi Y, Yuasa T, Yamaguchi A, Nohno T, Noji S, Matsuya T, Kurisu K, Koyama E, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Hedgehog proteins stimulate chondrogenic cell differentiation and cartilage formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15(9):1659–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Provot S, Kempf H, Murtaugh LC, Chung UI, Kim DW, Chyung J, Kronenberg HM, Lassar AB. Nkx3.2/Bapx1 acts as a negative regulator of chondrocyte maturation. Development. 2006;133(4):651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davidson D, Blanc A, Filion D, Wang H, Plut P, Pfeffer G, Buschmann MD, Henderson JE. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 18 signals through FGF receptor 3 to promote chondrogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(21):20509–20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aono Y, Yamazaki Y, Yasutake J, Kawata T, Hasegawa H, Urakawa I, Fujita T, Wada M, Yamashita T, Fukumoto S, Shimada T. Therapeutic effects of anti-FGF23 antibodies in hypophosphatemic rickets/osteomalacia. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(11):1879–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruppe MD, Zhang X, Imel EA, Weber TJ, Klausner MA, Ito T, Vergeire M, Humphrey JS, Glorieux FH, Portale AA, Insogna K, Peacock M, Carpenter TO. Effect of four monthly doses of a human monoclonal anti-FGF23 antibody (KRN23) on quality of life in X-linked hypophosphatemia. Bone Rep. 2016;5:158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]