Abstract

Background

Iturins, which belong to antibiotic cyclic lipopeptides mainly produced by Bacillus sp., have the potential for application in biomedicine and biocontrol because of their hemolytic and antifungal properties. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LL3, isolated previously by our lab, possesses a complete iturin A biosynthetic pathway as shown by genomic analysis. Nevertheless, iturin A could not be synthesized by strain LL3, possibly resulting from low transcription level of the itu operon.

Results

In this work, enhanced transcription of the iturin A biosynthetic genes was implemented by inserting a strong constitutive promoter C2up into upstream of the itu operon, leading to the production of iturin A with a titer of 37.35 mg l−1. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses demonstrated that the strain produced four iturin A homologs with molecular ion peaks at m/z 1044, 1058, 1072 and 1086 corresponding to [C14 + 2H]2+, [C15 + 2H]2+, [C16 + 2H]2+ and [C17 + 2H]2+. The iturin A extract exhibited strong inhibitory activity against several common plant pathogens. The yield of iturin A was improved to 99.73 mg l−1 by the optimization of the fermentation conditions using a response surface methodology. Furthermore, the yield of iturin A was increased to 113.1 mg l−1 by overexpression of a pleiotropic regulator DegQ.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first report on simultaneous production of four iturin A homologs (C14–C17) by a Bacillus strain. In addition, this study suggests that metabolic engineering in combination with culture conditions optimization may be a feasible method for enhanced production of bacterial secondary metabolites.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12934-019-1121-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Iturin A, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Promoter substitution, Response surface methodology, Pleiotropic regulator

Background

Iturin A, which contains a β-amino fatty acid chain with 14–17 carbons and a cyclic heptapeptide, is a potent antifungal lipopeptide mainly produced by Bacillus sp. [1–3]. Iturin A can be used as a potential biopesticide against plant pathogens and used for the treatment of human and animal mycoses due to its low toxicity and the lack of allergic effects on the host [4–6].

Iturin A is biosynthesized by the non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), and the Iturin A biosynthetic operon consists of four open reading frames called ituD, ituA, ituB and ituC [7]. ituD encodes a malonyl-CoA transacylase (MCT-domain), which is related to the synthesis of fatty acids. ituA, ituB and ituC contain amino acid-activating modules that encode the peptide and subunits of bacillomycin D synthetase. In addition, a TE domain is located at the C-terminal end of ituC, which is responsible for the cyclization and release of the lipoheptapeptide intermediate [3, 8]. So far, several iturin A-producing strains have been reported, including Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus methyltrophicus [7, 9–16].

Currently, promoter engineering can serve as a powerful tool for fine-tuning of the activity of the biosynthetic pathway enzymes for enhanced synthesis of many valuable products. In a previous study, the yield of iturin A was increased by threefold in B. subtilis RB14 by the replacement of the native promoter of the iturin A operon by a promoter of the plasmid pUB110 replication protein PrepU [7]. In another study, through the substitution of the surfactin operon promoter for a native lichenysin biosynthesis operon promoter, the mutant B. licheniformis WX02-Psrflch produced 779 mg l−1 lichenysin, a 5.5-fold improvement compared to that of wild strain WX-02 (121 mg l−1), indicating that enhanced production of lichenysin in WX02-Psrflch was attributed to elevated expression of lichenysin biosynthetic genes [17]. Recently, Jiao et al. [18] constructed an artificial IPTG-inducible promoter Pg2 and further introduced two point mutations in the − 35 and − 10 regions to produce a strong promoter Pg3. Pg3 was substituted for the native surfactin synthase promoter in the genome of B. subtilis THY-7, resulting in an engineered strain with a surfactin titer of 9.74 g l−1, a 16.7-fold improvement compared to that of wild-type strain THY-7.

Optimization of fermentation process is considered as a useful strategy to improve the yield of iturin A. In Bacillus sp. BH072, the yield of iturin A was improved to 52.21 mg ml−1 by optimizing medium components and fermentation conditions using a one-factor test and response surface methodology (RSM) [19]. In B. subtilis 3–10, significant enhancement of iturin A production could be achieved by a novel two-stage stepwise decreased glucose feeding strategy, leading to a maximum yield of 1.12 g l−1 [20].

Antibiotic lipopeptide biosynthesis in Bacillus strains is under regulation of complex metabolic network [8]. The biosynthesis of the antibiotic substances in Bacillus strains is regulated by the specific pleiotropic regulators [13, 21, 22]. For example, the quorum sensing cluster comQXPA plays important roles in surfactin biosynthesis. ComP activated by ComX phosphorylates the response regulator ComA, and then ComA motivates transcription of the srfA operon through binding to the promoter Psrf [23]. It was demonstrated that both the three pleiotropic regulators (DegU, DegQ and ComA) and two sigma factors (σB and σH) positively regulate transcriptional activation of the bmy promoter to promote bacillomycin D synthesis [21]. It was also verified that membrane spanning protein YczE and 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase Sfp exert their effect on bacillomycin D synthesis in a posttranscriptional manner [24]. A recent study indicated that the expression level of AbrB and PhrC was reduced with increased bacillomycin D production [25].

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LL3, which was identified initially as a poly-γ-glutamicacid (γ-PGA)-producing strain, has been shown to possess the complete Iturin A biosynthetic pathway in the genome based on the genome data of strain LL3 [26, 27], suggesting that this strain has the potential to produce iturin A. In this work, the production of antifungal lipopeptide iturin A in B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 was achieved by enhanced expression of the iturin A biosynthetic pathway. Furthermore, fermentation conditions optimization was carried out by using an RSM to improve the yield of iturin A. Finally, the production of iturin A was further enhanced by overexpression of a pleiotropic regulator DegQ.

Results

Genome and transcriptome analysis of B. amyloliquefaciens

According to the genome information, the six antibiotic substance biosynthetic gene clusters with a total size of ~ 170 kb, i.e., bacillaene, bacillibactin, bacilysin, iturin A, surfactin and fengycin, are present in the genome of B. amyloliquefaciens NK-1, accounting for 4.26% of its total genetic capacity (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Among the gene clusters, the itu biosynthetic gene cluster (38 kb) including ituD, ituA, ituB and ituC is responsible for iturin A biosynthesis and shows high homology to that of B. amyloliquefacians DSM7. A mutant strain NK-∆LP was generated from the strain NK-1 by deleting the γ-PGA synthetase gene cluster. Transcriptome analysis indicated that the transcriptional levels of the ituD, ituA, ituB and ituC in NK-∆LP were 1.9-, 4.59-, 4.39- and 4.22-fold higher than that in NK-1, respectively (Table 1). The fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) can be used as an indicator of the transcriptional activity of a gene [28]. Transcriptional activity of a gene is positively correlated with FPKM value. For NK-∆LP, the FPKM values for the ituD, ituA, ituB and ituC were still very low (Table 1). The low transcriptional level may contribute to the fact that iturin A was not detected in the culture broth of NK-∆LP when using the original or modified Landy medium (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Expression level comparison of genes in NK-1 and ∆LP

| Gene | Protein | NK-1 FPKM | ∆LP FPKM | Expression level fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ituD | Malonyl-CoA transacylase | 6.07445 | 11.3028 | 1.90 |

| ituA | Iturin A synthetase A | 4.33389 | 52.1055 | 4.59 |

| ituB | Iturin A synthetase B | 2.82559 | 29.7206 | 4.39 |

| ituC | Iturin A synthetase C | 6.89153 | 64.1951 | 4.22 |

| ywsC | PGA synthase CapB | 37.3213 | – | – |

| amyA | Alpha-amylase | 374.999 | 2554.04 | 3.77 |

FPKM fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

Fig. 1.

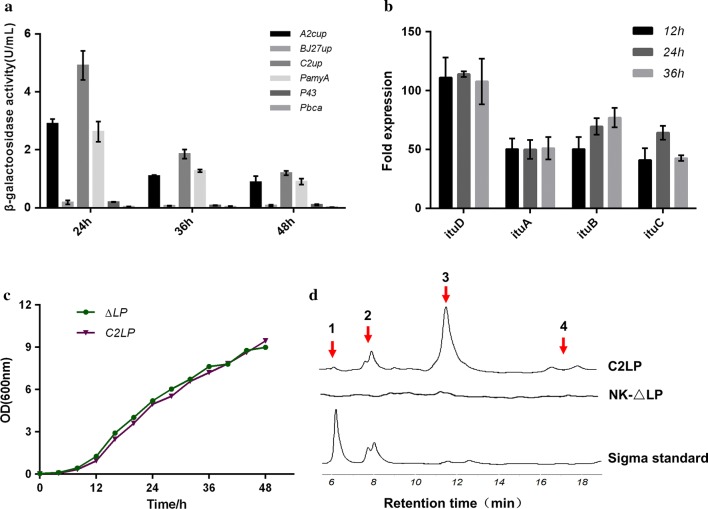

Strength comparison of the selected promoters and the effects of promoter C2up on the itu operon transcription and iturin A production. a Quantification of PA2cup-, PBJ27up-, PC2up-, PamyA- P43- and Pbca-driven β-galactosidase (bgaB) activity at 24, 36 and 48 h; b changes in the transcriptional level of ituD, ituA, ituB and ituC after 12, 24 and 36 h of fermentation, and the transcriptional level of each itu gene in NK-∆LP was used as a control; c growth curves of B. amyloliquefaciens NK-∆LP and C2LP; d HPLC chromatograms of Sigma standard and the produced iturin A samples by C2LP, and NK-∆LP was used as a control. Data are mean values ± standard deviations of three replicates

Selection of strong promoter to construct an iturin A-producing strain B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP

The strengths of the six promoters selected in this study were characterized by a β-galactosidase reporter assay. The β-galactosidase activity revealed that the transcriptional activities of the six promoters showed considerable differences with each other, but the activity of all promoters decreased gradually over the 48-h fermentation period (Fig. 1a). By comparing the six promoters, the maximum β-galactosidase activity was observed as early as 24 h when driven by the promoter C2up, and remained high at 36 and 48 h. Consequently, we further tested the ability of the screened strongest promoter C2up to improve the production of iturin A.

Inserting the strong promoter C2up into upstream of the itu operon in the genome of NK-∆LP was achieved using a scarless genome editing method with upp as a counter-selectable marker [29]. Successful construction of the promoter insertion mutant B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP was confirmed by PCR detection using the primers C2itu-SS and C2itu-XX (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The transcriptional level of the itu operon in C2LP was compared with that in NK-∆LP. As expected, the transcriptional levels of all the tested itu biosynthetic genes in C2LP were up-regulated obviously at different growth phases (Fig. 1b). The ituD in C2LP showed more than 100-fold higher transcriptional level compared to the ituD in NK-∆LP, and the transcriptional levels of the ituA, ituB and ituC in C2LP were 40- to 70-fold higher than that in NK-∆LP (Fig. 1b). Both the strain C2LP and NK-∆LP showed the similar growth profiles over a 48-h incubation period and reached a maximum OD600 of 9.0 and 9.5 at 48 h, respectively (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, iturin A was also detected in the fermentation broth of C2LP after 48 h of incubation (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that the strong constitutive promoter C2up may be used to enhance the transcription of the itu operon for iturin A production.

Characterization of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP

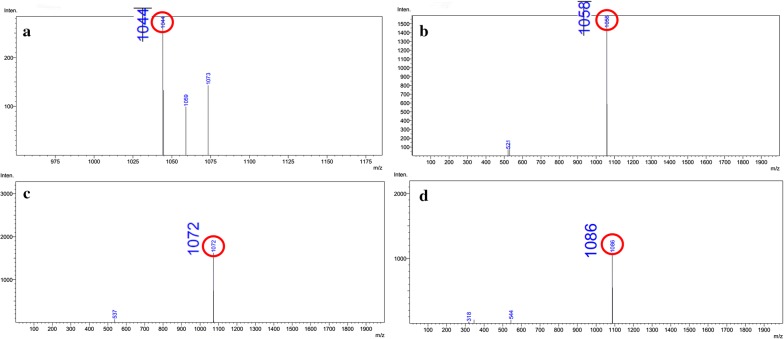

It was reported that iturin A produced by bacteria is a mixture of several iturin A homologs [13]. In this study, by comparing the HPLC chromatogram of the produced iturin A by C2LP with that of the Sigma iturin A standard, the peaks 1, 2 and 3 with a retention time of about 6, 8 and 10 min, respectively, could be detected with the above two kinds of samples. In contrast, the peak 4 could be detected only with the produced iturin A by C2LP but not with the Sigma iturin A standard (Fig. 1d). To verify whether the peaks are iturin A homologs, each peak product was purified from 2000 ml of the culture supernatant of strain C2LP for LC–MS analysis. The mass spectra of the purified products had molecular ion peaks at m/z 1044, 1058, 1072 and 1086, which were attributed to [C14 + 2H]2+, [C15 + 2H]2+, [C16 + 2H]2+ and [C17 + 2H]2+, respectively (Fig. 2). These compounds are iturin A homologs which differ in their alkane chain length by 14 Da corresponding to a CH2 group. The peak 3 product corresponding to C16-β-amino acid had the highest content among the produced four iturin A homologs by C2LP (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 2.

Mass spectra of the purified four iturin A homologs produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP. a The peak 1 product showing a molecular ion peak at m/z 1044 corresponds to the protonated form of C14-β-amino acid [C14 + 2H]2+; b the peak 2 product showing a molecular ion peak at m/z 1058 corresponds to the protonated form of C15-β-amino acid [C15 + 2H]2+; c the peak 3 product showing a molecular ion peak at m/z 1072 corresponds to the protonated form of C16-β-amino acid [C16 + 2H]2+; d the peak 4 product showing a molecular ion peak at m/z 1086 corresponds to the protonated form of C17-β-amino acid [C17 + 2H]2+

Antimycotic activity of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP

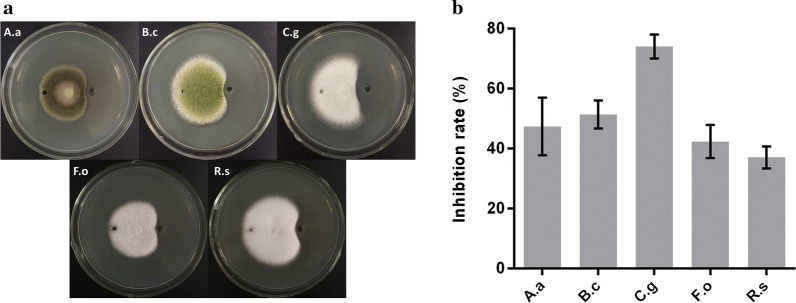

Five fungi including A. alternate, B. cinerea, C. gloeosporioides, F. oxysporum and R. solani were selected to test the antifungal activity of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP in vitro. As a result, the five fungi were significantly inhibited by the iturin A extract after 4 days of stationary culture (Fig. 3a). The iturin A extract from B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP showed the strongest inhibitory activity against C. gloeosporioides with an inhibition ratio of 74% (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the iturin A standard (Sigma) lacking C17-sidechain iturin A showed a decreased inhibition ratio against B. cinerea and C. gloeosporioides.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect picture (a) and inhibition ratio (b) of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP. Samples A.a, B.c, C.g, F.o and R.s correspond to A. alternate, B. cinerea, C. gloeosporioides, F. oxysporum and R. solani, respectively. Each well on the right was filled with 60 μl of the iturin A extract from C2LP, and 60 μl of sterile fermentation medium as a control was added to the well on the left. Data are reported as mean values of the inhibition ratio from three independent experiments

Pre-optimization of iturin A production by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP

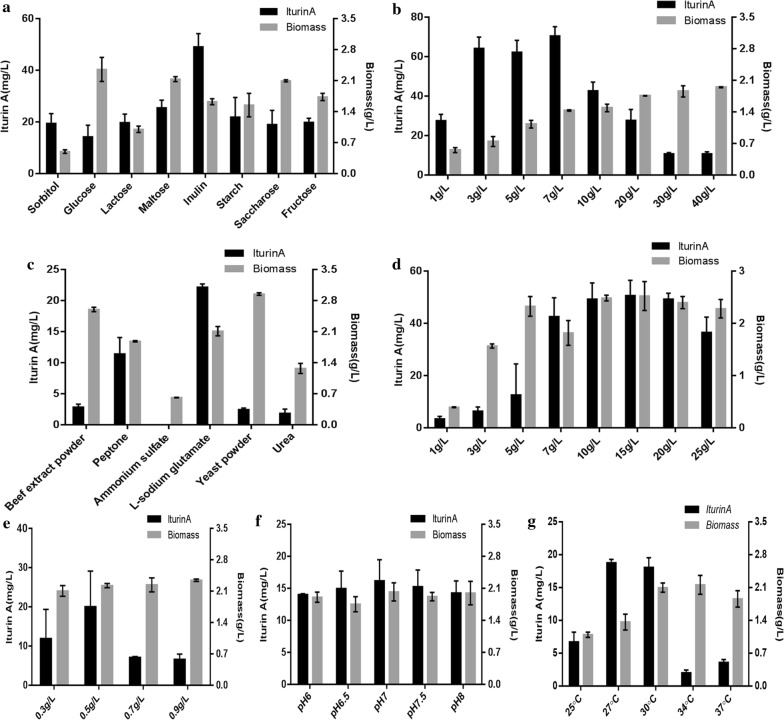

B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP had an iturin A titer of 37.35 mg l−1 when cultured in the original Landy medium. Thus, the fermentation medium was optimized to further improve the iturin A production. The effects of carbon and nitrogen sources, pH and temperature on iturin A production were investigated in shake-flask cultures. As shown in Fig. 4, inulin was the most appropriate one among the eight carbon sources (sorbitol, glucose, lactose, maltose, inulin, starch, saccharose and fructose), and l-sodium glutamate was the best nitrogen source among the six candidates (beef extract powder, peptone, ammonium sulfate, l-sodium glutamate, yeast power and urea). The optimal pH and temperature for iturin A production by strain C2LP were 7.0 and 27 °C, respectively. We further determined the optimal concentration of the main factors. The optimal concentrations of inulin, l-sodium glutamate and MgSO4 were 7, 15 and 0.5 g l−1, respectively.

Fig. 4.

The effect of the different single factor changes on iturin A production and biomass of B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP. a Carbon source, b inulin concentration, c nitrogen source, d l-sodium glutamate concentration, e MgSO4 concentration, f initial pH of fermentation medium, g fermentation temperature. Data are mean values ± standard deviations of three replicates

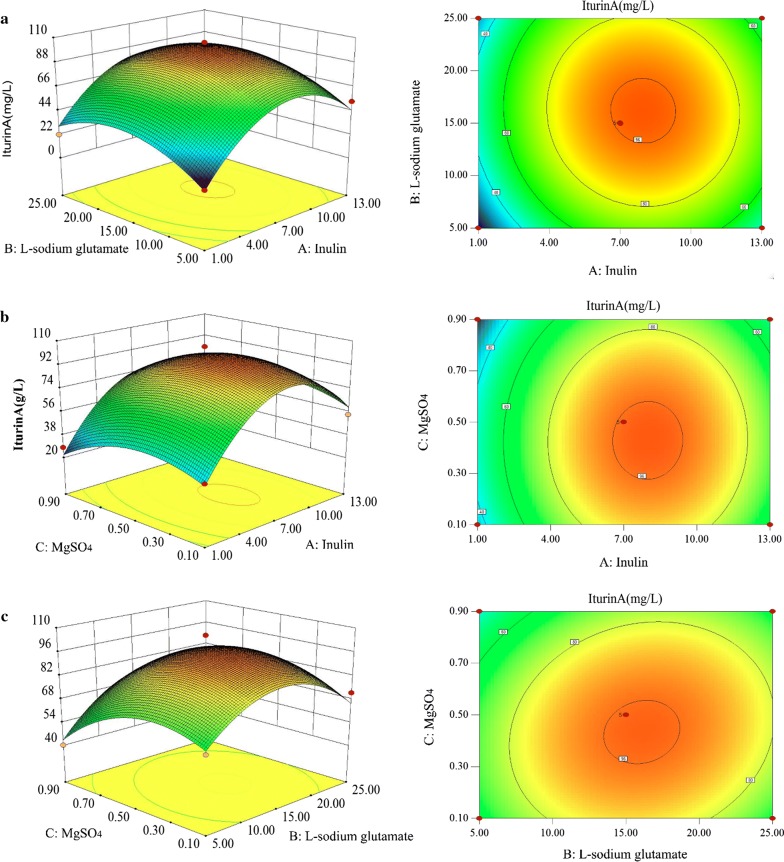

Multiple responses optimization of iturin A production

In this work, to improve iturin A production, three significant influence factors including inulin, l-sodium glutamate and MgSO4 were selected for further optimization using the RSM design based on the single-factor tests result. The experimental design and results are shown in Table 2. Our results showed the response surfaces of two variables at the center level of other variables, respectively (Fig. 5). The non-linear nature of all response surfaces demonstrated that there were considerable interactions between each of the independent variables, and that the independent variables affected the iturin A production. From these results, we obtained the optimal concentrations of the three factors (g l−1): inulin 7.97, l-sodium glutamate 16.02 and MgSO4 0.44. Under the optimized culture conditions, the shake-flask cultures of strain C2LP could produce 99.73 mg l−1 iturin A.

Table 2.

Experiment design and results of the Box–Behnken central composite design

| Run order | Factors (g/l) | Titer (mg/l) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Experimental | Predicted | |

| 1 | 1 | 5 | 0.5 | 15.70 ± 4.21 | 15.11 |

| 2 | 13 | 5 | 0.5 | 52.87 ± 5.07 | 44.98 |

| 3 | 1 | 25 | 0.5 | 22.00 ± 3.14 | 29.88 |

| 4 | 13 | 25 | 0.5 | 51.58 ± 1.73 | 52.17 |

| 5 | 1 | 15 | 0.1 | 36.43 ± 0.28 | 34.91 |

| 6 | 13 | 15 | 0.1 | 54.03 ± 0.51 | 59.80 |

| 7 | 1 | 15 | 0.9 | 28.07 ± 2.02 | 22.30 |

| 8 | 13 | 15 | 0.9 | 48.05 ± 0.81 | 49.57 |

| 9 | 7 | 5 | 0.1 | 62.02 ± 3.64 | 64.14 |

| 10 | 7 | 25 | 0.1 | 72.06 ± 3.71 | 65.69 |

| 11 | 7 | 5 | 0.9 | 36.93 ± 6.77 | 43.29 |

| 12 | 7 | 25 | 0.9 | 65.81 ± 7.67 | 63.70 |

| 13 | 7 | 15 | 0.5 | 92.76 | 96.83 |

| 14 | 7 | 15 | 0.5 | 96.60 | 96.83 |

| 15 | 7 | 15 | 0.5 | 94.20 | 96.83 |

| 16 | 7 | 15 | 0.5 | 105.69 | 96.83 |

| 17 | 7 | 15 | 0.5 | 94.89 | 96.83 |

Fig. 5.

Response surface indicates the effect of three main factors on iturin A production. a The effect of inulin and l-sodium glutamate on iturin A production; b the effect of inulin and MgSO4 on iturin A production; c the effect of l-sodium glutamate and MgSO4 on iturin A production

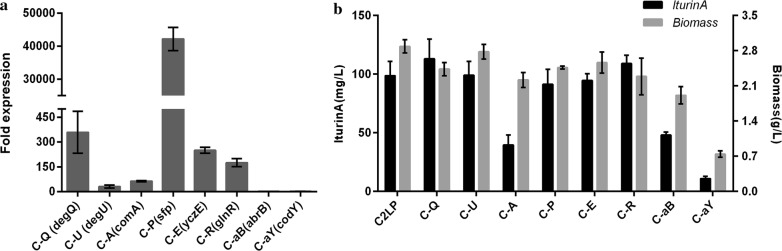

Effect of the overexpression and suppression of the regulatory factors on iturin A production

In this work, to test whether the overexpression or suppression of the eight regulatory factors (DegQ, DegU, ComA, Sfp, YczE, GlnR, AbrB and CodY) could directly increase the production of iturin A by strain C2LP, we constructed the various overexpression or suppression vectors and transformed the vectors into strain C2LP. All the recombinant strains, especially for C-A, C-P and C-aB, showed poor growth in the optimized Landy medium compared with strain C2LP (data not shown). As expected, the relative transcriptional levels of the eight regulatory factors were up- or down-regulated by overexpression or suppression (Fig. 6a). Moreover, the recombinant strains C-Q and C-R could produce 113.1 and 109.06 mg l−1 iturin A after 48 h of cultivation, respectively, which were 14.51 and 10.46% higher than the iturin A titer of strain C2LP. In contrast, the recombinant strains C-A, C-aB and C-aY showed a sharp decrease in the iturin A titer, only with a titer of 39.54, 48.12 and 10.95 mg l−1, respectively (Fig. 6b). Generally, the functionality of pleiotropic regulators would be affected by culture conditions. Nevertheless, the iturin A titer was not further improved by applying the RSM method to the finally obtained degQ-overexpressing strain C-Q.

Fig. 6.

a Expression profiles of the eight pleiotropic regulators degQ, degU, comA, sfp, yczE, glnR, abrB and codY in the corresponding engineered strains. The expression level of each regulator in C2LP was used as a control. b Comparison of iturin A production and biomass of B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP with that of its derived strains

Discussion

B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 is a natural γ-PGA producing strain. In our previous study, we could not detect any iturin A product in the culture broth of the wild strain B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 even though this strain contains the complete itu operon [26]. Since both the γ-PGA and iturin A biosynthetic pathways may compete for the same substrate glutamic acid, we constructed the γ-PGA sythetase knockout strain NK-∆LP [26]. Unfortunately, no iturin A could be detected in the culture broth of strain NK-∆LP (Fig. 1d).

Due to the key roles of the promoter in the regulation of gene expression, many studies focused on promoter modification and substitution [17, 18, 30]. In strain NK-∆LP, the low transcriptional level of the itu operon, as revealed by transcriptome analysis (Table 1), might be the main reason of the block of iturin A production. Therefore, the replacement of the native iturin synthetase promoter with a strong Bacillus constitutive promoter may be a feasible approach for enhancing the transcriptional level of the itu operon in strain NK-∆LP.

In this study, the six strong Bacillus constitutive promoters (A2cup, BJ27up, C2up, PamyA, P43 and Pbca) were selected based on previous literatures and transcriptome analysis. P43, a strong constitutive promoter, is widely used in Bacillus for enzyme expression or pathway engineering, such as the overexpression of endoglucanase, α-amylase and keratinase [31–33], as well as hyaluronan synthesis [34]. A2cup and C2up from B. subtilis phage φ29 are strong early σA-RNA polymerase-dependent promoters [35]. BJ27up is a strong constitutive promoter from Bacillus expression plasmid pJH27. Pbca and PamyA derived from B. amyloliquefaciens NK-1, which are responsible for the transcription of γ-PGA synthetase and α-amylase, respectively, were assumed to possess higher transcriptional activity than the native iturin synthetase promoter, as judged by FPKM values from transcriptome analysis (Table 1). C2up was demonstrated to be the strongest promoter among the above six promoters using β-galactosidase reporter assays (Fig. 1a). Integrating the C2up into upstream of the itu operon in the genome of NK-∆LP could significantly elevate transcriptional level of the itu operon at different growth phases (Fig. 1b). As expected, the C2up substitution strain C2LP was able to produce iturin A with a titer of 37.35 mg l−1 (Fig. 1d). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the substitution of the strong Bacillus constitutive promoters C2up for the native iturin synthetase promoter may promote the production of iturin A by enhancing the transcriptional level of the itu operon.

Optimization of fermentation medium and condition may serve as an effective approach for the improvement of the antifungal lipopeptide production. In a previous study, carbon and nitrogen sources were demonstrated to be the main factors capable of enhancing iturin A production, and their optimum amounts in the fermentation medium were predicted [5]. Optimization of iturin A production by adding Asn, Glu and Pro during the fed-batch fermentation process was studied using an artificial neural network-genetic algorithm and uniform design. The iturin A yield was improved to 13,364.5 ± 271.3 U ml−1, which was 1.34-fold higher than that of the control (batch fermentation without adding the amino acids) [6]. It was reported that inulin could promote efficient production of bacillomycin D by significantly improving the expression of lipopeptide bacillomycin D synthetase genes and by up-regulating the related regulatory factors such as ComA, DegU, SigmaH and Spo0A [25]. Coincidentally, fructose similarly enhanced the expression of lipopeptide fengycin synthetase genes, regulatory factors (ComA, SigmaH, DegU and DegQ) and the cell division and growth related genes (ftsZ and divIVA), leading to increased fengycin production [36]. In this study, five single factors including both fermentation conditions and medium components were explored to select the appropriate degree, and finally it was confirmed that inulin 7 g l−1, l-sodium glutamate 15 g l−1, MgSO4 0.5 g l−1, pH 7.0 and temperature 27 °C were the appropriate one (Fig. 4). RSM is a time-saving experimental methodology that can use quantitative data to evaluate multiple process variables and their interactions by establishing a mathematical model [37, 38]. RSM has been employed to optimize the fermentation conditions and media components for cyclic lipopeptide production in shake-flask fermentation [19, 39]. In this study, three significant influence factors inulin, l-sodium glutamate and MgSO4 were chosen to be optimized by RSM for rapidly achieving the optimum fermentation medium. The three factors optimized by RSM were as follows: inulin (A) 7.97 g l−1, l-sodium glutamate (B) 16.02 g l−1 and MgSO4 (C) 0.44 g l−1 (Fig. 5). The result is definitely believable because the coefficient of determination (R2) of the model was 0.9696 (very close to 1).

So far, the regulatory mechanism of iturin A biosynthesis is still unknown. In contrast, the regulatory mechanism of bacillomycin D biosynthesis has been studied preliminarily [21, 24, 25]. Since iturin A and bacillomycin D belong to iturins family and their synthetase operons exhibit high similarity, the biosynthesis of iturin A and bacillomycin D may be similarly regulated. Although B. subtilis 168 was converted into an iturin A producer RM/iS2 by the introduction of the iturin A operon and an sfp gene, the titer of iturin A was very low. By inserting the pleiotropic regulator degQ, the titer of iturin A was increased to 64 μg ml−1, which was eightfold higher than that of RM/iS2 [13]. The degQ gene from B. subtilis 168 is not functional because of the mutation in promoter region. In this study, to explore whether overexpression or repression of pleiotropic regulators is profitable for iturin A synthesis, we selected the eight pleiotropic regulators DegQ, DegU, ComA, GlnR, CodY, AbrB, YczE and Sfp from B. amyloliquefaciens LL3. As shown in Fig. 6b, DegQ had the most significant positive impact on iturin A production, followed by GlnR, reaching a titer of 113.1 and 109.1 mg l−1, respectively. In the future, more deep studies on the regulatory mechanism of iturin A biosynthesis are required for improved production of iturin A by manipulating the specific regulatory factors.

The composition of iturins produced differs in their alkane chain length and would largely depend on the species of Bacillus used. The main components of iturin A produced by the B. subtilis 168-derived RM/iSd series strains were C14- and C15-β-amino acid and a minor amount of C16-β-amino acid was also detected [13]. Chen et al. isolated an active substance from B. subtilis JA by reversed-phase HPLC separation and identified two iturin A homologs (C14- and C15-β-amino acid) by electrospray ionization and collision-induced dissociation mass spectrometry analysis [40]. B. methyltrophicus TEB1 produced three iturin A homologs C14-, C15- and C16-β-amino acid, among which C15-β-amino acid was identified as the main component [10]. B. amyloliquefaciens W10 produced four iturin homologs, as revealed by mass spectrometry, showing molecular ion peaks at m/z 1051.5, 1065.5, 1079.5, 1081.5, 1093.5 and 1095.5, which were attributed to [C13 + Na]+, [C14 + Na]+, [C15 + Na]+, [C14 + K]+, [C16 + Na]+ and [C15 + K]+, respectively [15, 41] demonstrated the production of two iturin A homologs (m/z 1044.3, 1047.9 and 1069.5) by B. amyloliquefaciens B94. Caldeira et al. [42] also identified two iturin homologs (m/z 1031.5 and 1045.5) produced by B. amyloliquefaciens CCMI 1051. In this study, B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP produced four iturin A homologs C14-, C15-, C16- and C17-β-amino acid, among which C16-β-amino acid had the highest content followed by C15-β-amino acid (Figs. 1d and 2). To our knowledge, there is no report on the co-production of four iturin A homologs (C14–C17) by a Bacillus strain so far. The iturin A extract from B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP exhibited strong inhibitory activity against several common plant pathogens (Fig. 3), suggesting that the structural diversity of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP may contribute to a broad inhibitory spectrum against various plant pathogenic fungi.

In this study, selection of a non-natural iturin A-producing strain LL3 has three main reasons, which include: (1) strain LL3 contains all the iturin A biosynthetic genes; (2) the iturin A biosynthesis capacity can be restored by the activation of the transcription of the iturin A biosynthetic genes through the replacement of a native iturin A biosynthesis operon promoter with a strong constitutive promoter C2up; (3) B. amyloliquefaciens has an ability to produce diverse iturin A homologs.

Conclusions

In this study, B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 was engineered to be an iturin A producer by promoter substitution. Furthermore, iturin A production was significantly improved using a combined strategy of culture conditions optimization and pleiotropic regulators overexpression. More importantly, this strain is capable of simultaneous production of four iturin A homologs, suggesting that the strain may serve as a biocontrol agent or iturin A producer for widespread application. Currently, more efforts are still needed for the elucidation of the regulatory mechnism of iturin A biosynthesis and for the industrial scale production of iturin A by the strain.

Methods

Strains, plasmids and culture conditions

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for plasmid construction and transformation. E. coli GM2163 was used for plasmid demethylation. The B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 strain was deposited in the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC) with accession number CCTCC M 208109 [27]. B. amyloliquefaciens NK-∆LP was used as the parental strain [43]. B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP was used for the production of iturin A.

Plasmid pCB containing β-galactosidase gene was used as a reporter vector for characterizing the strengths of the selected promoters [44]. A temperature-sensitive plasmid p-KSU containing a upp expression cassette, which was derived from the pKSV7 plasmid [45], was used for the construction of the C2up promoter insertion vector. Plasmid pHT01 was used for the overexpression and repression of pleiotropic regulators. All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains and plasmids | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-1 | LL3 derivative, ∆pMC1, ∆upp | [43] |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-∆LP | NK-1 derivative, ∆pgsBCA | [43] |

| B. subtilis168 | trpC2, containing a strong constitutive promoter P43 | This lab |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-Pbca | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-Pbca | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-A2cup | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-A2cup | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-BJ27up | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-BJ27up | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-C2up | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-C2up | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-PamyA | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-PamyA | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens NK-P43 | NK-1 derivative with plasmid pCB-P43 | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP | ∆LP derivative, C2up promoter inserted into upstream of the itu operon | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-Q | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-degQ | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-U | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-degU | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-A | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-comA | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-P | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-sfp | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-E | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-yczE | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-R | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-glnR | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-aB | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-antiabrB | This work |

| B. amyloliquefaciens C-aY | C2LP derivative with plasmid pHT-anticodY | This work |

| E. coli DH5α | F−, ϕ80dlacZM1, (lacZYA-argF)U169, deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17 (rk−, mk+), phoA, supE44, λ−thi-1, gyrA96, relA1 | This lab |

| E. coli GM2163 | F−, ara-14 leuB6 thi-1 fhuA31 lacY1 tsx-78 galK2 galT22 supE44 hisG4 rpsL136 (Strr) xyl-5 mtl-1 dam13::Tn9 (Camr) dcm-6 mcrB1 hsdR2 mcrA |

This lab |

| Fungi | ||

| Alternaria alternate | Wild-type | This lab |

| Botrytis cinerea | Wild-type | This lab |

| Colletotrichum gloeosporioides | Wild-type | This lab |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Wild-type | This lab |

| Rhizoctonia solani | Wild-type | This lab |

| Plasmid | ||

| pCB | Shuttle vector containing the β-galactosidase gene bgaB from B. stearothermophilus as a reporter gene, Ampr, Err | Xie et al. [44] |

| pKSU | pKSV7 derivative with upp gene expression cassette | This lab |

| pHT01 | Cmr; IPTG inducible expression vector for Bacillus | MoBiTec |

| pCB-Pbca | pCB derivative with the promoter Pbca | This work |

| pCB-A2cup | pCB derivative with the promoter A2cup | This work |

| pCB-BJ27up | pCB derivative with the promoter BJ27up | This work |

| pCB-C2up | pCB derivative with the promoter C2up | This work |

| pCB-PamyA | pCB derivative with the promoter PamyA | This work |

| pCB-P43 | pCB derivative with the promoter P43 | This work |

| pKSU-C2itu | pKSU derivative, a C2up promoter insertion vector | This work |

| pHT-degQ | pHT01 derivative with the gene degQ | This work |

| pHT-degU | pHT01 derivative with the gene degU | This work |

| pHT-comA | pHT01 derivative with the gene comA | This work |

| pHT-sfp | pHT01 derivative with the gene sfp | This work |

| pHT-yczE | pHT01 derivative with the gene yczE | This work |

| pHT-glnR | pHT01 derivative with the gene glnR | This work |

| pHT-antiabrB | pHT01 derivative with the gene anti-abrB sRNA sequence and hfq gene | This work |

| pHT-anticodY | pHT01 derivative with the gene anti-codY sRNA sequence and hfq gene | This work |

All strains were cultured at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) media [46]. When required, LB media were supplemented with ampicillin (Ap, 50 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (Cm, 5 μg ml−1) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 100 μg ml−1). For lipopeptide iturin A production, B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP was cultured at 27 °C and 160 rpm for 48 h in the optimized Landy medium, pH 7.0 [47], containing 7.97 g l−1 inulin, 16.02 g l−1 l-sodium glutamate, 0.44 g l−1 MgSO4, 1 g l−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g l−1 KCl, 0.15 mg l−1 FeSO4, 5.0 mg l−1 MnSO4 and 0.16 mg l−1 CuSO4. All fungi used in antagonism tests were incubated at 28 °C for 3 to 5 days and maintained on potato dextrose agar.

Identification of strong promoters by β-galactosidase assay

The six strong Bacillus constitutive promoters (A2cup, BJ27up, C2up, PamyA, P43 and Pbca) were selected based on previous literatures and transcriptome analysis of B. amyloliquefaciens NK-1. Transcriptome analysis of B. amyloliquefaciens NK-1 was carried out at BGI-Shenzhen (BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China) based on standard procedure [48]. The nucleotide sequences of the six promoters are shown in Additional file 1. To test the strengths of the selected promoters, we generated the recombinant reporter plasmids by inserting each of the promoters into upstream of the bgaB reporter gene on the pCB plasmid (Additional file 1: Figure S3). The NK-1 strains transformed with the reporter plasmids were used for the measurement of β-galactosidase activity using a previous method described by Xie et al. [44].

Construction of the C2up promoter insertion mutant

For targeted insertion of the C2up promoter into upstream of the itu operon, the upstream and downstream homologous arms were PCR amplified from genomic DNA of B. amyloliquefaciens NK-∆LP using primers C2UP-F/C2UP-R and C2DN-F/C2DN-R, respectively. The C2up promoter was amplified from the pUC-C2up using primers C2-F/C2-R and then fused with the upstream and downstream fragments by overlap PCR. The fused fragment was ligated into the linearized p-KSU vector using a one-step cloning kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to generate the C2up promoter insertion vector pKSU-C2itu.

Subsequently, we used a scar-less genome editing method to construct the promoter insertion mutant [29]. In brief, the vector pKSU-C2itu was transformed into B. amyloliquefaciens NK-∆LP by electroporation. The single-crossover mutants were screened by incubated at 42 °C for 24 h on the LB agar plates with Cm and further identified by PCR using the specific primers. The selected positive clones were then incubated in LB medium supplemented with 5-FU at 42 °C for 24 h. The cell suspensions were diluted to 10−5 and spread on the LB agar plates with 5-FU. The double-crossover mutants showing Cms and 5-FUr were further identified by PCR, and the amplified PCR products were sent to BGI for DNA sequencing to verify the inserted promoter sequence. The resulting mutant was designated as B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP. All primers used in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Iturin A isolation and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens was cultured with shaking at 160 rpm in the fermentation medium for 48 h. The cell-free culture supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 9000 rpm and 4 °C for 20 min, subsequently acidified with 6 M HCl to pH 2 and stored overnight at 4 °C. The precipitate formed was collected by centrifugation at 4 °C and 13,000 rpm for 20 min and then resuspended with 100 ml methyl alcohol for iturin A extraction; the pH of the sample was adjusted to 7.0 using 1 M NaOH [7]. After 48 h of incubation at 180 rpm and 37 °C, the samples were centrifuged to collect the supernatant containing the iturin A extract. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter and subjected to HPLC analysis.

For further purification of iturin A, the four iturin A homologs were recovered, respectively, at different retention times when using HPLC analysis. The collected solutions were concentrated to remove the residual acetonitrile by a vacuum rotary evaporator and then lyophilized using a vacuum freeze dryer to obtain the purified iturin A.

Lipopeptide iturin A was detected and quantified by reversed-phase HPLC as follows: 20 μl of the extract described above was injected into a HPLC C18 column [Innoval ODS-2 (4.6 mm diameter by 250 mm), Agel, Tianjin, China] maintained at 37 °C. For sample separation, the mobile phase consisting of water and acetonitrile (55:45, v/v) supplemented with 0.035% formic acid was used at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Meanwhile, the absorption spectrum was set at 220 nm. The iturin A standard (Sigma) was used for all analyses.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analyses

To determine precisely the different iturin A homologs produced by B. amyloliquefaciens, the extracted iturin A samples were analyzed by LC–MS using Shimadzu HPLC system LC-10AVP equipped with a photo diode array (PDA) detector and a reversed-phase C-18 column, Luna® (250 mm × 4.6 mm internal diameter, 5 μ particle size, Phenomenex, USA). The samples (50 μl) were injected and two different solvent systems were used for effective separation and detection of iturin A homologs. The mobile phase consisting of water (eluent A) and acetonitrile (eluent B) supplemented with 0.035% (v/v) formic acid was used at a gradient flow rate of 10 ml min−1. The gradient conditions were as follows: firstly, starting at 90% eluent A and 10% eluent B, eluent A was linearly decreased to 55% with the increase of eluent B to 45% within the first 2.5 min; then, eluent A was linearly decreased to 0% with the increase of eluent B to 100% in the next 2.5 min and then maintained for 3 min; finally, eluent A was linearly increased to 90% with the decrease of eluent B to 10% in the next 1 min and then maintained for 1 min. The eluants were read at 220 nm using PDA detector (UVD340U, Dionex, USA). The LC-MS analyses were performed using an LTQ-XL instrument (Thermo Scientific, Germany) equipped with Xcalibur software.

Fungal growth inhibition assay

Antifungal activity of iturin A produced by B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP was evaluated by the agar-well diffusion method using the five fungi Alternaria alternate, Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Fusarium oxysporum and Rhizoctonia solani [15]. Wells of 5-mm diameter were formed in PDA agar plates with a sterile cork borer. Then, the iturin A extract (60 μl) from B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP was added into the well. Sterile fermentation medium (60 μl) was added to another well, which was used as a control. A 5-mm diameter disk inoculated with fungi was placed in the center of the agar plate, and then the plates were incubated at 28 °C and monitored for any inhibition of mycelia growth during a 3- to 5-day period.

Single-factor tests and multiple responses optimization

To obtain a higher iturin A yield, single-factor tests and RSM were used to optimize the fermentation medium. In this study, the Box-Behnken experimental design model was used. Our experimental plan consisted of 17 trials and the independent variables were studied at three different levels, designated as − 1, 0 and + 1 for low, middle and high values, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S2). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and the average yield of iturin A obtained was taken as the dependent variable or response. The software Design-Expert 8.0.6.1 (Stat-Ease, USA) was used for the experimental design.

Overexpression and repression of pleiotropic regulators

To investigate the influence of pleiotropic regulators on iturin A production in B. amyloliquefaciens, the six native regulatory genes (degQ, degU, comA, glnR, sfp and yczE) from B. amyloliquefaciens were overexpressed using the expression vector pHT01 in B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP. Additionally, the two regulatory genes codY and abrB in B. amyloliquefaciens were repressed by the expression of synthetic small regulatory RNAs (sRNA). The sRNAs were designed and transcribed as described previously [49]. The gene IDs of degQ, degU, comA, glnR, sfp, codY, abrB and yczE are 12202327, 12205127, 12202323, 12204645, 12202653, 12204515, 12201069 and COG2364, respectively.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

To further determine the transcriptional level of target genes (ituD, ituA, ituB, ituC, degQ, degU, comA, glnR, sfp, codY, abrB and yczE), bacterial cultures were harvested after 24 h incubation. Total RNAs of these bacterial cultures were isolated using the commercial RNApure Bacteria kit (DNase I) (Cwbio, Beijing, China). Then, cDNA was synthesized using the extracted RNA samples and HiScript® II Reverse Transcriptase SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was carried out using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) on a StepOnePlus™ real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions were as follows: pre-incubation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 20 s. The transcriptional levels of target genes were normalized against that of rspU [50].

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Diagram of the locations for antibiotic substance gene clusters in B. amyloliquefacians NK-1. Figure S2. Confirmation of the construction of the mutant strain B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP via PCR. Lane M, DNA marker Ш; lane 1, PCR product obtained by amplification with the NK-∆LP genomic DNA as the template; lane 2, PCR product obtained by amplification with the C2LP genomic DNA as the template. Figure S3. Map of reporter vectors containing respectively the six promoters (A2up, BJ27up, C2up, PamyA, P43 and Pbca). bgaB, β-galactosidase gene; ApR, ampicillin resistance gene; ErR, erythromycin resistance gene. Table S1. Primers used in this study. Table S2. Coded and actual levels of factors used in the experimental design.

Authors’ contributions

YLD and CY designed this study. YLD took charge of the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and played an important role in the manuscript writing. FJZ, XSL, XF and RH made contribution to data acquisition. CY, WXG and SFW helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

All of the authors would like to thank Prof. Cunjiang Song for his valuable suggestions on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional file.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Funding of China (Grant Nos. 31570035 and 31670093), the Tianjin Natural Science Funding (Grant Nos. 17JCZDJC32100 and 18JCYBJC24500) and the Postdoctoral Science Funding of China (Grant No. 2018M631729).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- NRPSs

non-ribosomal peptide synthetases

- RSM

response surface methodology

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase million

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- LC–MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

Contributor Information

Yulei Dang, Email: 13821615007@163.com.

Fengjie Zhao, Email: zfjmail2010@163.com.

Xiangsheng Liu, Email: lxs_tianjin@163.com.

Xu Fan, Email: 812382037@qq.com.

Rui Huang, Email: 993014540@qq.com.

Weixia Gao, Phone: +86 22 23503753, Email: watersave@126.com.

Shufang Wang, Phone: +86 22 23503753, Email: wangshufang@nankai.edu.cn.

Chao Yang, Phone: +86 22 23503866, Email: yangc20119@nankai.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ongena M, Jacques P, Touré Y, Destain J, Jabrane A, Thonart P. Involvement of fengycin-type lipopeptides in the multifaceted biocontrol potential of Bacillus subtilis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;69:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero D, de Vicente A, Rakotoaly RH, Dufour SE, Veening JW, Arrebola E, et al. The iturin and fengycin families of lipopeptides are key factors in antagonism of Bacillus subtilis toward Podosphaera fusca. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:430–440. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-4-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ongena M, Jacques P. Bacillus lipopeptides: versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin H, Zhang X, Li K, Niu Y, Guo M, Hu C, et al. Direct bio-utilization of untreated rapeseed meal for effective iturin A production by Bacillus subtilis in submerged fermentation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizumoto S, Shoda M. Medium optimization of antifungal lipopeptide, iturin A, production by Bacillus subtilis in solid-state fermentation by response surface methodology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0994-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng W, Zhong J, Yang J, Ren Y, Xu T, Xiao S, et al. The artificial neural network approach based on uniform design to optimize the fed-batch fermentation condition: application to the production of iturin A. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13:54. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuge K, Akiyama T, Shoda M. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of the iturin A operon. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6265–6273. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6265-6273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein T. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:845–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernat P, Paraszkiewicz K, Siewiera P, Moryl M, Płaza G, Chojniak J. Lipid composition in a strain of Bacillus subtilis, a producer of iturin A lipopeptides that are active against uropathogenic bacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:157. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2126-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalai-Grami L, Karkouch I, Naili O, Slimene IB, Elkahoui S, Zekri RB, et al. Production and identification of iturin A lipopeptide from Bacillus methyltrophicus TEB1 for control of Phoma tracheiphila. J Basic Microbiol. 2016;56:864–871. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim PI, Ryu J, Kim YH, Chi YT. Production of biosurfactant lipopeptides Iturin A, fengycin and surfactin A from Bacillus subtilis CMB32 for control of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;20:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez KJ, Viana JD, Lopes FC, Pereira JQ, Santos DM, Oliveira JS, et al. Bacillus spp. isolated from puba as a source of biosurfactants and antimicrobial lipopeptides. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:61. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuge K, Inoue S, Ano T, Itaya M, Shoda M. Horizontal transfer of iturin A operon, itu, to Bacillus subtilis 168 and conversion into an iturin A producer. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4641–4648. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4641-4648.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velmurugan N, Choi MS, Han SS, Lee YS. Evaluation of antagonistic activities of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis against wood-staining fungi: in vitro and in vivo experiments. J Microbiol. 2009;47:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s12275-009-0018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang QX, Zhang Y, Shan HH, Tong YH, Chen XJ, Liu FQ. Isolation and identification of antifungal peptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens W10. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24:25000–25009. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao X, Zhou ZJ, Han Y, Wang ZZ, Fan J, Xiao HZ. Isolation and identification of antifungal peptides from Bacillus BH072, a novel bacterium isolated from honey. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu Y, Xiao F, Wei X, Wen Z, Chen S. Improvement of lichenysin production in Bacillus licheniformis by replacement of native promoter of lichenysin biosynthesis operon and medium optimization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:8895–8903. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5978-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiao S, Li X, Yu H, Yang H, Li X, Shen Z. In situ enhancement of surfactin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis using novel artificial inducible promoters. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114:832–842. doi: 10.1002/bit.26197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Han Y, Tan XQ, Wang J, Zhou ZJ. Optimization of antifungal lipopeptide production from Bacillus sp. BH072 by response surface methodology. J Microbiol. 2014;52:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-3354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin H, Li K, Niu Y, Guo M, Hu C, Chen S, Huang F. Continuous enhancement of iturin A production by Bacillus subtilis with a stepwise two-stage glucose feeding strategy. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15:53. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koumoutsi A, Chen XH, Vater J, Borriss R. DegU and YczE positively regulate the synthesis of bacillomycin D by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain FZB42. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6953–6964. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00565-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuge K, Ano T, Hirai M, Nakamura Y, Shoda M. The genes degQ, pps, and lpa-8 (sfp) are responsible for conversion of Bacillus subtilis 168 to plipastatin production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2183–2192. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.9.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satpute SK, Bhuyan SS, Pardesi KR, Mujumdar SS, Dhakephalkar PK, Shete AM, Chopade BA. Molecular genetics of biosurfactant synthesis in microorganisms. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;672:14–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5979-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen XH, Koumoutsi A, Scholz R, Borriss R. More than anticipated-production of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;16:14–24. doi: 10.1159/000142891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian S, Lu H, Meng P, Zhang C, Lv F, Bie X, Lu Z. Effect of inulin on efficient production and regulatory biosynthesis of bacillomycin D in Bacillus subtilis fmbJ. Bioresour Technol. 2015;179:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao W, Liu F, Zhang W, Quan Y, Dang Y, Feng J, et al. Mutations in genes encoding antibiotic substances increase the synthesis of poly-γ-glutamic acid in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LL3. MicrobiologyOpen. 2017;6:e00398. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng W, Cao M, Song C, Xie H, Liu L, Yang C, et al. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LL3, which exhibits glutamic acid-independent production of poly-γ-glutamic acid. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:3393–3394. doi: 10.1128/JB.05058-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang W, Gao W, Feng J, Zhang C, He Y, Cao M, Li Q, Sun Y, Yang C, Song C, Wang S. A markerless gene replacement method for B. amyloliquefaciens LL3 and its use in genome reduction and improvement of poly-γ-glutamic acid production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:8963–8973. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5824-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blazeck J, Alper HS. Promoter engineering: recent advances in controlling transcription at the most fundamental level. Biotechnol J. 2013;8:46–58. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu YH, Lu FP, Li Y, Yin XB, Wang Y, Gao C. Characterisation of mutagenised acid-resistant alpha-amylase expressed in Bacillus subtilis WB600. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;78:85–94. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang JJ, Rojanatavorn K, Shih JC. Increased production of Bacillus keratinase by chromosomal integration of multiple copies of the kerA gene. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;87:459–464. doi: 10.1002/bit.20145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang XZ, Sathitsuksanoh N, Zhu Z, Percival Zhang YH. One-step production of lactate from cellulose as the sole carbon source without any other organic nutrient by recombinant cellulolytic Bacillus subtilis. Metab Eng. 2011;13:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin P, Kang Z, Yuan P, Du G, Chen J. Production of specific-molecular-weight hyaluronan by metabolically engineered Bacillus subtilis 168. Metab Eng. 2016;35:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meijer WJ, Salas M. Relevance of UP elements for three strong Bacillus subtilis phage phi29 promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1166–1176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu H, Qian S, Muhammad U, Jiang X, Han J, Lu Z. Effect of fructose on promoting fengycin biosynthesis in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fmb-60. J Appl Microbiol. 2016;121:1653–1664. doi: 10.1111/jam.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gangadharan D, Sivaramakrishnan S, Nampoothiri KM, Sukumaran RK, Pandey A. Response surface methodology for the optimization of alpha amylase production by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:4597–4602. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih IL, Shen MH. Application of response surface methodology to optimize production of poly(ε-lysine) by Streptomyces albulus IFO14147. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2006;39:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu XB, Zheng ZM, Yu HQ, Wang J, Liang FL, Liu RL. Optimization of medium constituents for a novel lipopeptide production by Bacillus subtilis MO-01 by a response surface method. Process Biochem. 2005;40:3196–3201. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Wang L, Su CX, Gong GH, Wang P, Yu ZL. Isolation and characterization of lipopeptide antibiotics produced by Bacillus subtilis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu GY, Sinclair JB, Hartman GL, Bertagnolli BL. Production of iturin A by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens suppressing Rhizoctonia solani. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:55–63. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00027-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caldeira AT, Arteiro JMS, Coelho AV, Roseiro JC. Combined use of LC–ESI-MS and antifungal tests for rapid identification of bioactive lipopeptides produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CCMI 1051. Process Biochem. 2011;46:1738–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2011.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng J, Gu Y, Han L, Bi K, Quan Y, Yang C, et al. Construction of a Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain for high purity levan production. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362:fnv079. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie CC, Luo Y, Chen YH, Cai J. Construction of a promoter-probe vector for Bacillus thuringiensis: the identification of cis-acting elements of the chiA locus. Curr Microbiol. 2012;64:492–500. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith K, Youngman P. Use a new integrational vector to investigate compartment-specific expression of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIM gene. Biochimie. 1992;74:705–711. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green MR, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 4. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Landy M, Rosenman SB, Warren GH. An antibiotic from Bacillus subtilis active against pathogenic fungi. J Bacteriol. 1947;54:24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng J. Metabolic engineering of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens for γ-PGA overproduction, Doctor Thesis. Nankai University, Tianjin, China; 2016.

- 49.Feng J, Gu Y, Quan Y, Cao M, Gao W, Zhang W, et al. Improved poly-γ-glutamic acid production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens by modular pathway engineering. Metab Eng. 2015;32:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reiter L, Kolstø AB, Piehler AP. Reference genes for quantitative, reverse-transcription PCR in Bacillus cereus group strains throughout the bacterial life cycle. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;86:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Diagram of the locations for antibiotic substance gene clusters in B. amyloliquefacians NK-1. Figure S2. Confirmation of the construction of the mutant strain B. amyloliquefaciens C2LP via PCR. Lane M, DNA marker Ш; lane 1, PCR product obtained by amplification with the NK-∆LP genomic DNA as the template; lane 2, PCR product obtained by amplification with the C2LP genomic DNA as the template. Figure S3. Map of reporter vectors containing respectively the six promoters (A2up, BJ27up, C2up, PamyA, P43 and Pbca). bgaB, β-galactosidase gene; ApR, ampicillin resistance gene; ErR, erythromycin resistance gene. Table S1. Primers used in this study. Table S2. Coded and actual levels of factors used in the experimental design.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional file.