Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate plasma acylcarnitine profiles and their relationships with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis among individuals with and without HIV-infection.

Design:

Prospective cohort studies of 499 HIV-positive and 206 HIV-negative individuals from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.

Methods:

Twenty-four acylcarnitine species were measured in plasma samples of participants at baseline. Carotid artery plaque was assessed using repeated B-mode carotid artery ultrasound imaging in 2004–2013. We examined the associations of individual and aggregate short-chain (C2-C7), medium-chain (C8-C14) and long-chain acylcarnitines (C16-C26) with incident carotid artery plaque over 7 years.

Results:

Among 24 acylcarnitine species, C8- and C20:4-carnitines showed significantly lower levels comparing HIV-positive to HIV-negative individuals (FDR adjusted P<0.05); and C20- and C26-carnitines showed significantly higher levels in HIV-positive using ART than those without ART (FDR adjusted P<0.05). In the univariate analyses, higher aggregated short-chain and long-chain acylcarnitine scores were associated with increased risk of carotid artery plaque (RRs=1.22 [95% CI 1.02–1.45] and 1.20 [1.02–1.41] per SD increment, respectively). The association for the short-chain acylcarnitine score remained significant (RR=1.23 [1.05–1.44]) after multivariate adjustment (including traditional CVD risk factors). This association was more evident in HIV-positive individuals without persistent viral suppression (RR=1.37 [1.11–1.69]) compared to those with persistent viral suppression during follow-up (RR=1.03 [0.76–1.40]) or HIV-negative individuals (RR=1.02 [0.69–1.52]).

Conclusions:

In two HIV cohorts, plasma levels of most acylcarnitines were not significantly different between HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals. However, higher levels of aggregated short-chain acylcarnitines were associated with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis.

Keywords: HIV infection, acylcarnitines, cardiovascular disease, metabolomics, atherosclerosis, carotid artery

Introduction

Levocarnitine (L-carnitine) and acylcarnitine, which is an ester of L-carnitine, play important roles in transporting activated fatty acids (acyl-FA-Coenzyme A [CoA]) across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the mitochondrial matrix for β-oxidation.[1, 2] During this process, L-carnitine undergoes esterification in the membrane space to form free CoA and acylcarnitine, and then in turn undergoes reverse transesterification back to L-carnitine and acyl-CoA after carrying the FAs to the mitochondrial matrix.[1] As this process is essential in fatty acid metabolism and in maintaining intracellular CoA homeostasis, accumulation of acylcarnitines has been related to incomplete fatty acid oxidation and impaired mitochondrial function.[1–4] Recent metabolomics studies have reported significant associations between elevated circulating acylcarnitines levels (e.g., plasma short-chain and medium-chain acylcarnitines) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) events in the general population.[5–8]

In the pre-HAART and early HAART era, L-carnitine/acylcarnitine deficiency has been reported among some people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (i.e. those at the late stages of HIV, especially among those with neuropathy complications),[9, 10] possibly due to malabsorption, antiretroviral drugs and lipoatrophy induced increased availability of fatty acid.[11] Some studies, mostly small uncontrolled trials, suggested benefits of L-carnitine and/or acetylcarnitine supplementation on HIV disease progression and complications.[11, 12] However, few studies have examined circulating acylcarnitines in HIV-positive individuals in the HAART era,[13, 14] especially given their detrimental relationships with CVD complications found in the general population.[5–8] In a recent study of 60 HIV-positive individuals and 20 HIV-negative healthy controls, Waagsb et al. found that plasma levels of short-chain (C2- and C3-carnitine) and medium-chain (C5- and C8-carnitine) acylcarnitines were reduced in HIV-positive individuals before initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) and ART use partially recovered the acylcarnitine levels longitudinally.[13] But the relationships between acylcarnitines and HIV-related CVD complications were not investigated. In light of the fact that some have advocated for the use of carnitine and acylcarnitine supplementation to benefit HIV-positive individuals,[11, 12, 15] studies are needed to evaluate circulating acylcarnitine profiles and their relationships with long-term CVD risk in this population.

Our previous analyses in the Carotid Ultrasound Substudy (2004–2013) of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) have found that HIV-positive individuals have greater subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis risk compared to those without HIV infection.[16] In 2015, we initiated a plasma metabolomics project to examine plasma metabolites associated cardiometabolic risk in the context of HIV infection.[17] In the current analysis, we compared plasma levels of 24 acylcarnitine species between among HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals. We also examined the associations of individual acylcarnitine species and aggregate profiles of short-chain (C2-C7), medium-chain (C8-C14) and long-chain acylcarnitines (C16-C26) with progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis over a median 7-year follow-up period.

Methods

Study population

We included study participants from two longitudinal multicenter cohorts, the WIHS and MACS. The two ongoing cohorts follow up with participants and collect biological specimens semi-annually.[18, 19] In the plasma metabolomics study, we included 737 participants aged ≥35 years and were free of prevalent carotid artery plaque, cardiovascular disease and diabetes at baseline.[17] These participants underwent high-resolution B-mode carotid artery ultrasound scans at baseline (2004–2006) and follow-up scans (2011–2013) at a later visit.[16] All individuals provided informed consent, and each site’s institutional review board approved the study. In the current study, we further excluded those with missing covariates (n=2 for antihypertensive medication use, n=1 for body mass index and n=29 for blood lipids), leaving a study sample of 705 participants (369 women, 336 men) in the current analysis.

Ascertainment of carotid artery plaque

Carotid artery plaques were assessed at a baseline visit (2004–2006) and at a follow-up visit on average 7 years later. High-resolution B-mode carotid artery ultrasound was used to image six locations in the right carotid artery: the near and far walls of the common carotid artery (CCA), carotid bifurcation, and internal carotid artery. Plaque was defined as a focal IMT>1.5 mm in any of the six locations. A standardized protocol was used at all sites, [16] and IMT measures were obtained at a centralized reading center (University of Southern California). Repeated IMT measurements had good reliability, with the coefficient of variation 1.8% (intra-class coefficient (ICC) 0.98) in WIHS sites and 1.0% (ICC 0.99) in MACS sites.[20] The primary outcome of interest was the incident carotid artery plaque during the median 7-year follow-up period.

Quantification of plasma acylcarnitines

A total of 26 acylcarnitine species were profiled on stored frozen plasma specimens that had been collected at the core study visit closest to the baseline carotid artery imaging study visit with UPLC-MS (Shimadzu Corp. and Thermo Fisher Scientific) at the Broad Institute Metabolomics Platform. Detailed methods have been described elsewhere.[5] Briefly, metabolites were extracted from 10 µL frozen plasma samples and prepared with 90 µL of 25% methanol/75% acetonitrile containing two internal standards. The samples were centrifuged and then separated using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, and analyzed using high-resolution mass spectrometry in the positive-ion mode. Metabolite peaks were identified and were confirmed with the use of authentic reference standards. Metabolites were quantified using area-under-the-curve of the peaks. Raw data were processed with the use of TraceFinder 3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Progenesis CoMet v2.0 (Nonlinear Dynamics). In this analysis, 24 acylcarnitine species with coefficient of variation (CV) ≤20% were included, and C16-OH carnitine and C18:1-OH carnitine with CV >20% were excluded.

Demographics and clinical variables

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables were collected using standardized protocols at semi-annual core study visits.[21] HIV serostatus was ascertained using the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method and confirmed by Western blot. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was based on a serological test for antibodies or a nucleic acid test for viral ribonucleic acid (RNA). Other HIV-related characteristics include cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell count, HIV RNA and ART use. ART is defined as use of more than two nucleoside reverse transciptase inhibitors (NRTI) in combination with at least one protease inhibitor (PI) or one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI); one NRTI in combination with at least one PI and at least one NNRTI; or an abacavir or tenofovir containing regimen of more than three NRTI in the absence of both PI and NNRTI, except for the three NRTI regimens consisting of abacavir, tenofovir, and lamivudine, or didanosine, tenofovir, and lamivudine.[20] HIV-1 RNA were measured using essays from NucliSens (Organon Teknika Corporation, Durham, NC), sensitive to 80 copies HIV RNA/mL. Body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure were ascertained by trained personnel. Total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c) were analyzed in a central laboratory. Viral suppression was defined as having consistent HIV RNA ≤80 copies/mL among those with continuous ART use over the study period.[22]

Statistical methods

Acylcarnitine concentrations under the limit of detection (<10% for each acylcarnitine species) were imputed with half of the minimum detected level before transformation. We applied rank-based inverse normal transformation [5, 23] to raw concentrations of the 24 acylcarnitine species to obtain standardized scores (mean=0, standard deviation=1) in men and women separately. We generated scores of short-chain (8 species, C2-C7), medium-chain (9 species, C8-C14:2) and long-chain (7 species, C16-C26) acylcarnitines by computing the weighted sum of acylcarnitine scores, as previously done.[5] Weights were coefficients from a multivariate regression model that was fit with each individual acylcarnitine adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI and HIV serostatus. We used the t-test to compare normalized levels of individual acylcarnitines and aggregate short-, medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines by HIV serostatus and use of ART among HIV-positive individuals. To control for multiple testing, we applied false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment to P-values. We used Poisson regression models with robust estimates of variance to obtain incidence risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of incident carotid artery plaque per standard deviation (SD) increment in individual acylcarnitines and aggregate short-chain, medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines. We adjusted for covariates including age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection, injection drug use, HIV serostatus, baseline CD4 cell count and ART drug use (NRTI, NNRTI and PI), systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, HDL-c, and lipid-lowering medication use. We also examined the associations of acylcarnitines with incident carotid artery plaque among all participants stratified by sex and HIV serostatus; and among HIV-positive individuals stratified by baseline CD4 cell count (<500 or ≥500 cells/mm3), baseline HIV viral load (undetectable [≤80 copies/mL] or detectable [>80 copies/mL]) and persistent viral suppression status during follow-up by including an interaction term between acylcarnitine score and subgroup in the models. Age- and sex-adjusted partial Spearman’s correlations were used to assess correlations among acylcarnitines and their correlations with CVD risk factors and HIV-related parameters. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.4.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Two sided P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 108 participants (86 HIV+ and 22 HIV-) developed carotid artery plaque during the median follow-up time of 7 years. Baseline characteristics of 705 participants are described in Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics were similar between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants. HIV-positive individuals were more likely than HIV-negative participants to have HCV infection and a history of injection drug use. Participants with HIV infection had cumulatively been on ART for a median 4–5 years. At baseline, the majority (79%) received ART in the past 6 months and 56% had undetectable HIV RNA. Compared to those without HIV infection, HIV-positive participants were more like to have lower levels of total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol, and have lipid-lowering medication use and anti-hypertensive medication use (women only). BMI and blood pressure were similar between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by HIV serostatus.

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (N=271) | HIV− (N=98) | HIV+ (N=228) | HIV− (N=108) | |

| % or Median (IQR) |

% or Median (IQR) |

% or Median (IQR) |

% or Median (IQR) |

|

| Age, years | 42 (38-46) | 42 (38-46) | 46 (43-50) | 47 (45-54) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White/Other | 9% | 5% | 57% | 64% |

| Hispanic | 31% | 29% | 11% | 10% |

| African American | 60% | 66% | 32% | 26% |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 42% | 32% | 9% | 5% |

| High school | 30% | 32% | 14% | 14% |

| College and above | 28% | 36% | 77% | 81% |

| Behavioral risk factors | ||||

| Current smoking | 47% | 59% | 36% | 23% |

| Current crack/cocaine use | 7% | 16% | 15% | 8% |

| History of injection drug use | 31% | 27% | 11% | 3% |

| History of HCV infection | 34% | 21% | 15% | 6% |

| HIV-specific characteristics | ||||

| Baseline CD4+ T cell count, cells/mm3 | 438 (289-616) | 1002 (768-1287) | 519 (358-687) | 912 (730-1097) |

| Baseline HIV viral load ≤80 copies/mL | 47% | - | 67% | - |

| ART use in past 6 months | 75% | - | 84% | - |

| Cumulative exposure of ART, years | 4.0 (2.5-6.5) | - | 4.9 (2.3-7.3) | - |

| NRTI use in past 6 months | 74% | - | 83% | - |

| NNRTI use in past 6 months | 29% | - | 47% | - |

| PI use in past 6 months | 45% | - | 42% | - |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.9 (7.2) | 29.7 (7.1) | 25.8 (4.3) | 26.4 (4.0) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 175 (152-207) | 182 (160-203) | 187 (156-213) | 198 (172-222) |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 47 (38-57) | 57 (46-66) | 43 (36-52) | 49 (42-58) |

| Lipid-lowering drug use | 4% | 0% | 23% | 13% |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 115 (106-124) | 116 (105-126) | 122 (115-129) | 125 (117-132) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73 (67-81) | 72 (66-80) | 73 (68-79) | 74 (69-80) |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use | 18% | 10% | 16% | 17% |

| Family history of CVD | 25% | 23% | 57% | 54% |

Abbreviations: ART: antiretroviral therapy, HCV: hepatitis C virus, HDL-c: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HIV: human immunodeficiency virus, NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NNRTI: non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PI: protease inhibitor, CVD: cardiovascular disease.

HIV infection and plasma acylcarnitines

Among all participants, plasma medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines were moderately-to-highly correlated within groups of similar chain lengths, while short-chain acylcarnitines were weakly correlated (Figure S1). Correlation patterns for plasma acylcarnitines were similar between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants.

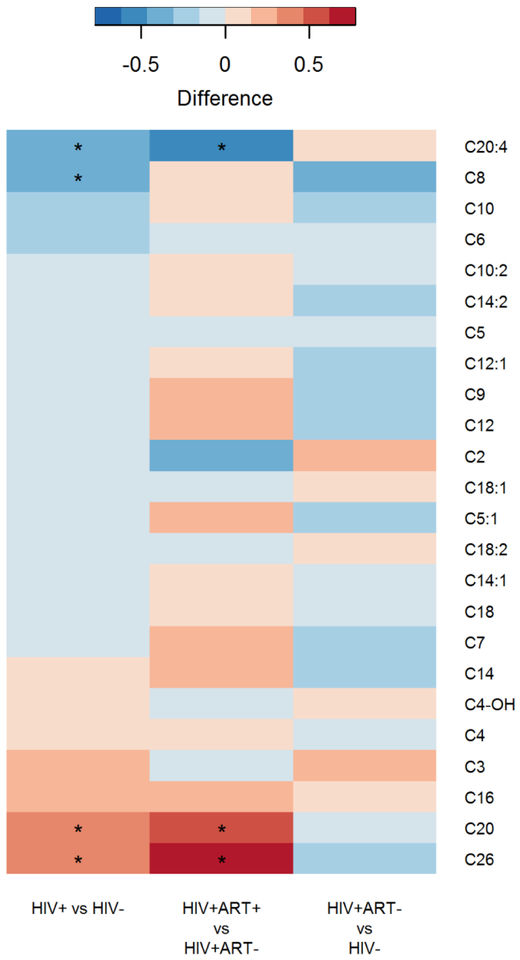

Overall, while there were few statistically significant differences in plasma levels of acylcarnitines between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants, the majority (17 of 24) showed lower levels in HIV-positive participants, with C8- and C20:4-carnitine reaching statistical significance (FDR adjusted P<0.05), compared to those without HIV infection (Figure 1). Among HIV-positive participants, plasma levels of most acylcarnitines (16 of 24) were higher in those treated with ART, with C20- and C26- carnitine reaching statistical significance (FDR adjusted P<0.05), compared to those without ART (Figure 1). Plasma levels of most acylcarnitines tended to be lower in HIV-positive participants without ART compared to HIV-negative participants, although no acylcarnitines reached statistical significance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differences in individual acylcarnitine species by HIV serostatus and ART use among HIV-positive participants.

Raw acylcarnitine concentrations were normalized with rank based inverse normal transformation by sex before analysis. *P-value <0.05 after FDR adjustment.

No significant differences in aggregated short-chain, medium-chain or long-chain acylcarnitine scores were observed between HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants (Table S1). Among HIV-positive participants, these acylcarnitine scores were not correlated with CD4+ cell count or HIV viral load (Table S2). In addition, all 3 acylcarnitine scores were modestly positively correlated with age, and there were a few very modest correlations between short-chain acylcarnitine scores and conventional CVD risk factor (e.g., BMI, HDL-cholesterol) (Table S2).

Plasma acylcarnitines and incident carotid artery plaque

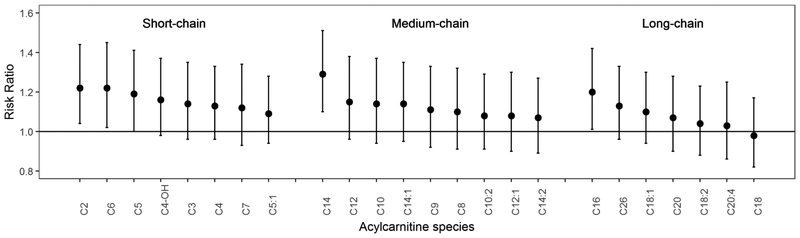

Figure 2 shows the associations of individual acylcarnitines with incident carotid artery plaque, adjusted for demographic, behavioral and HIV infection related factors. Most of acylcarnitines (23 of 24) showed positive associations with risk of carotid artery plaque, but none of them were statistically significant after controlling for multiple testing (all FDR adjusted P>0.05). Short-chain acylcarnitines showed generally stronger associations with incident carotid artery plaque than medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines. C2- and C6-carnitine in short-chain group, C14-carnitine in medium-chain group, and C16-carnitine in long-chain group were the leading acylcarnitines associated with incident carotid artery plaque at a nominal significant level (RRs=1.20–1.30; P<0.05). Most of the associations between individual acylcarnitines and risk of carotid artery plaque were slightly attenuated after further adjustment for conventional CVD risk factors (Table S3).

Figure 2.

Associations of individual acylcarnitine species with incident carotid artery plaque.

Data are risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of carotid artery plaque per standard deviation increment in acylcarnitine species, adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection, injection drug use and HIV serostatus. Raw data of acylcarnitine concentrations were rank-based inverse normal transformed by sex and standard deviations were sex-specific.

Table 2 shows the associations of aggregated short-chain, medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitine scores with incident carotid artery plaque. After adjustment for demographic, behavioral factors, higher short-chain (RR=1.25 [95% CI 1.05–1.49] per SD increment; P=0.01) and long-chain acylcarnitine scores (RR=1.21 [1.03–1.43]; P=0.02) were associated with increased risk of carotid artery plaque. The association between short-chain acylcarnitine score and carotid artery plaque remained significant (RR=1.23 [1.05–1.44]; P=0.01) after further adjusting for HIV-related factors and traditional CVD risk factors. The findings were generally consistent between men and women. Although the associations of the acylcarnitine scores with incident plaque were more pronounced in women than in men, there were no significant interactions (all P for interaction>0.05).

Table 2.

Associations of aggregated short-chain, medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitine scores with incident carotid artery plaque

| All | Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | P for interaction | |

| Short-chain acylcarnitine (C2-C7) score | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.25 (1.05-1.49) | 0.01 | 1.50 (1.15-1.96) | 1.10 (0.89-1.38) | 0.09 |

| Model 2 | 1.26 (1.07-1.48) | 0.005 | 1.48 (1.13-1.95) | 1.14 (0.94-1.38) | 0.12 |

| Model 3 | 1.23 (1.05-1.44) | 0.01 | 1.44 (1.10- 1.90) | 1.10 (0.91-1.34) | 0.13 |

| Medium-chain acylcarnitine (C8-C14) score | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.17 (0.97-1.40) | 0.10 | 1.23 (0.92-1.66) | 1.12 (0.90-1.40) | 0.61 |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (0.98-1.40) | 0.08 | 1.22 (0.91-1.63) | 1.14 (0.92-1.42) | 0.73 |

| Model 3 | 1.14 (0.95-1.36) | 0.15 | 1.17 (0.88-1.56) | 1.11 (0.89-1.40) | 0.78 |

| Long-chain acylcarnitine (C16-C26) score | |||||

| Model 1 | 1.21 (1.03-1.43) | 0.02 | 1.26 (0.98-1.62) | 1.18 (0.95-1.46) | 0.68 |

| Model 2 | 1.18 (0.99-1.40) | 0.06 | 1.24 (0.97-1.59) | 1.14 (0.91-1.43) | 0.60 |

| Model 3 | 1.15 (0.97-1.37) | 0.10 | 1.20 (0.93-1.54) | 1.12 (0.90-1.40) | 0.70 |

Data are adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of carotid artery plaque per standard deviation increment in short-chain, medium-chain and long-chain carnitine scores (weighted sums of carnitines species). Raw data of acylcarnitine concentrations were rank-based inverse normal transformed by sex and standard deviations were sex-specific. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection and injection drug use. Model 2 further adjusted for HIV serostatus, and baseline CD4 cell count, NRTI use, NNRTI use and PI use (HIV-infected participants only). Model 3 further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and lipid-lowering medication use.

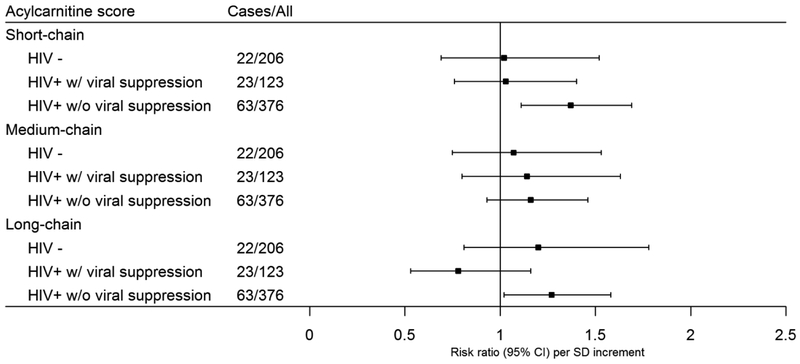

Our further analyses explored potential differences in associations of aggregated acylcarnitine scores and risk of carotid artery plaque according to HIV serostatus and viral suppression status during follow-up (Figure 3). Of note, aggregated short-chain acylcarnitine score was significantly associated with increased risk of carotid artery plaque in HIV-positive individuals (RR=1.27 [1.07–1.51]), particularly in those without persistent viral suppression (RR =1.37 [1.11–1.69]), but not in those with persistent virus suppression during follow-up (RR =1.03 [0.76–1.40]) or HIV-negative participants (RR=1.02 [0.69–1.52]) (Figure 3). However, no significant heterogeneity across these 3 groups was observed (P for interaction=0.13). Associations of aggregated acylcarnitine scores and risk of carotid artery plaque were generally consistent among HIV-positive participants stratified by baseline CD4+ cell count and baseline viral load (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Associations of aggregated short, medium and long-chain acylcarnitine scores with incident carotid artery plaque in HIV-negative participants, and HIV-positive participants with and without persistent viral suppression.

Data are adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of carotid artery plaque per standard deviation increment in acylcarnitine score (weighted sums of carnitines species), adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection, injection drug use, HIV serostatus, baseline CD4 cell count, NRTI use, NNRTI use, PI use, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and lipid-lowering medication use. Raw data of acylcarnitine concentrations were rank-based inverse normal transformed by sex and standard deviations were sex-specific.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a broad spectrum of circulating short-chain, medium-chain, and long-chain acylcarnitine (24 acylcarnitines species) among HIV-positive individuals. In a previous study, Waagsbo et al found that plasma short-chain (C2 carnitine and C3 carnitine) and medium-chain (C5 carnitine and C8 carnitine) were reduced in HIV-positive patients, especially among those with low CD4+ count.[13] Here, we observed significantly reduced C8- and C20:4-carnitine levels in HIV-positive individuals. However, most acylcarnitines were not statistically significantly different by HIV serostatus, though they showed a trend of lower levels in HIV-positive individuals compared to those who were HIV-negative. These observations may be explained by the ART use in the majority of the study participants and well-controlled HIV disease progression, as a previous study has shown that plasma acylcarnitines were decreased among rapid progressors and were partially recovered by ART.[13] Indeed, we observed a trend of higher levels for most acylcarnitines in ART users than in non-users. However, it is unclear whether the increase/recovery in levels of acylcarnitines is related to ART or just concurrent with better conditions (i.e. improve in absorption of dietary intake of carnitines). Future study will be needed to clarify this mechanism so that the necessity of carnitine supplementation in people with HIV infection could be evaluated.

Another major finding of this study is the significant association between higher levels of aggregated plasma acylcarnitines and greater progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis. Specifically, plasma short-chain acylcarnitines, rather than medium- or long-chain acylcarnitines, showed a significant association with increased risk of carotid artery plaque, independent of traditional CVD risk factors. The associations between acylcarnitines and CVD risks have been reported in several studies of non-HIV populations; however, it remains uncertain whether short-chain, medium-chain or long-chain acylcarnitines are most predictive. In a diet intervention trial, baseline plasma short-chain acylcarnitines showed a relatively stronger association with increased risk of CVD compared with medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines.[5] Other studies using principal component analysis have reported that factors comprising medium-chain and long-chain acylcarnitines are independent predictors for CVD and death events.[6, 8] Consistent with a previous finding,[24] we found several even-chain acylcarnitines (C2-, C6-, C14- and C16-carnitine) that were nominally associated with incident carotid artery plaque.

The associations of aggregated short-chain acylcarnitines with risk of carotid artery plaque tended to be most evident for virologically unsuppressed HIV-positive individuals. Meanwhile, null and non-significant associations were observed both among virologically suppressed HIV-positive and among those without HIV infection. However, we might have limited statistical power to test for interaction in this study. The potential mechanisms of this finding is unclear but might be related to the role of acylcarnitines in immune activation and inflammation. It has been found that viremic HIV+ individuals have dramatically higher degrees of monocyte activation than those virally suppressed.[25] Monocytes produce inflammatory mediators and play a critical part in the pathology of atherosclerosis,[26] which may interact with effects of acylcarnitines that activate proinflammatory signaling pathways.[27–29]

The mechanisms underlying the association of aggregated acylcarnitines and CVD risk are yet to be elucidated. One possible explanation is that alterations in acylcarnitines reflect mitochondria dysfunction, [1–4] which is believed to contribute to the development of CVD.[30–32] However, it should be noted that acylcarnitine alternations may not only be a biomarker but also play functional roles in mitochondria function, inflammation and immune activation, fatty acid oxidation, and glucose metabolism.[1–4] For example, some short-chain carnitines (C2, C4-OH, C5, C6) have been associated with insulin resistance,[2] which elevates the risk of CVD.[33, 34] In addition, C3 and C5 carnitines are derived from branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) which have been linked with diabetes, atherosclerosis and CVD, and defective BCAA catabolism may disturb cardiac glucose metabolism.[2, 35] The relationships of acylcarnitines and CVD risks could be complicated in HIV infection since HIV-positive individuals are susceptible to mitochondria dysfunction and cardiometabolic disorders (e.g., dyslipidemia, insulin resistance).[31, 36–41]

Major strengths of this study include two well-characterized HIV cohorts, a prospective study design, a broad spectrum of acylcarnitine profiles, and longitudinal measures of subclinical atherosclerosis. However, there are several limitations. First, we did not assess associations with clinical CVD events or mortality, although subclinical atherosclerosis measure has been validated as a surrogate outcome for CVD risk.[42, 43] Second, we did not have information regarding diet and exercise, which may influence plasma acylcarnitine profiles. Third, we only measured acylcarnitines at one time point and did not capture variation in acylcarnitines over time. Thus potential changes in circulating acylcarnitines with HIV disease progression and ART use are unknown in this study. Fourth, the stability of frozen blood samples may affect the levels of metabolites.[44, 45] Finally, we had relatively small sample size and thus limited power to test effect modification by HIV infection or other HIV parameters. Replication of our findings in other HIV cohorts would provide validation.

In summary, in this study of two long-standing HIV cohorts, we did not find significantly decreased levels for most plasma acylcarnitines among HIV-positive individuals, potentially due to widespread ART use. More importantly, we found that aggregated short-chain acylcarnitines were associated with greater progression of carotid artery atherosclerosis in HIV-positive individuals, especially in those without persistent viral suppression. Given the potential unfavorable effect of elevated acylcarnitines on CVD risk suggested by this study, L-carnitine/acylcarnitine supplementation may not be recommended in HIV-positive individuals who are on ART. Evidence is needed regarding the long-term effects of carnitine and/or acylcarnitine supplementation on chronic cardiovascular complications in HIV-positive individuals.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Levels of aggregated acylcarnitine scores (mean, SD) by behavioral and HIV-related factors.

Table S2. Partial Spearman correlations of aggregated acylcarnitine scores with traditional CVD risk factors and HIV related factors.

Table S3. Associations of individual acylcarnitine species with incident carotid plaque.

Table S4. N (%) of ART class, combination and ART drug use among 394 ART users.

Figure S1. Spearmen correlations among acylcarnitine species.

Figure S2. Associations of aggregated short-, medium- and long-chain acylcarnitine scores with incident carotid artery plaque stratified by HIV infection related characteristics, stratified by: (a) baseline CD4 cell count, (b) baseline HIV RNA. Models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection, injection drug use, HIV serostatus, baseline CD4 cell count, NRTI use, NNRTI use, PI use, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Figure S3. Differences in individual acylcarnitine scores by ART class and ART drugs. Raw acylcarnitine concentrations were normalized with rank based inverse normal transformation by sex before analysis. *P-value <0.05 after FDR adjustment.

Acknowledgements

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA), and P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR).

MACS (Principal Investigators): Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (Joseph Margolick, Todd Brown), U01-AI35042; Northwestern University (Steven Wolinsky), U01-AI35039; University of California, Los Angeles (Roger Detels, Otoniel Martinez-Maza, Otto Yang), U01-AI35040; University of Pittsburgh (Charles Rinaldo, Lawrence Kingsley, Jeremy Martinson), U01-AI35041; the Center for Analysis and Management of MACS, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (Lisa Jacobson, Gypsyamber D’Souza), UM1-AI35043. The MACS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects was also provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (NIDCD). MACS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR001079 (JHU ICTR) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Johns Hopkins ICTR, or NCATS. The MACS website is located at http://aidscohortstudy.org/.

Funding:

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) K01HL129892 to Q.Q., and other funding sources for this study include R01HL140976 to Q.Q, R01HL126543, R01HL132794, R01HL083760 and R01HL095140 to R.C.K., R01HL095129 to W.S.P., K01HL137557 to D.B.H., and Feldstein Medical Foundation Research Grant to Q.Q.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Kizer reports stock ownership in Amgen, Gilear Sciences, Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer. Others have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Reuter SE, Evans AM. Carnitine and acylcarnitines: pharmacokinetic, pharmacological and clinical aspects. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2012; 51(9):553–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schooneman MG, Vaz FM, Houten SM, Soeters MR. Acylcarnitines: reflecting or inflicting insulin resistance? Diabetes 2013; 62(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCoin CS, Knotts TA, Adams SH. Acylcarnitines-old actors auditioning for new roles in metabolic physiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015; 11(10):617–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kompare M, Rizzo WB. Mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation disorders. Seminars in pediatric neurology 2008; 15(3):140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guasch-Ferre M, Zhen Y, Ruiz-Canela M, Hruby A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Clish CB, et al. Plasma acylcarnitines and risk of cardiovascular disease: effect of Mediterranean diet interventions. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103(6):1408–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizza S, Copetti M, Rossi C, Cianfarani MA, Zucchelli M, Luzi A, et al. Metabolomics signature improves the prediction of cardiovascular events in elderly subjects. Atherosclerosis 2014; 232(2):260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah SH, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Crosslin DR, Haynes C, et al. Association of a Peripheral Blood Metabolic Profile With Coronary Artery Disease and Risk of Subsequent Cardiovascular Events. Circ-Cardiovasc Gene 2010; 3(2):207–U233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SH, Sun JL, Stevens RD, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Pieper KS, et al. Baseline metabolomic profiles predict cardiovascular events in patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2012; 163(5):844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Famularo G, Moretti S, Marcellini S, Trinchieri V, Tzantzoglou S, Santini G, et al. Acetyl-carnitine deficiency in AIDS patients with neurotoxicity on treatment with antiretroviral nucleoside analogues. Aids 1997; 11(2):185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desimone C, Famularo G, Tzantzoglou S, Trinchieri V, Moretti S, Sorice F. Carnitine Depletion in Peripheral-Blood Mononuclear-Cells from Patients with Aids - Effect of Oral L-Carnitine. Aids 1994; 8(5):655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilias L, Manoli I, Blackman MR, Gold PW, Alesci S. L-carnitine and acetyl-L-carnitinde in the treatment of complications associated with HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. Mitochondrion 2004; 4(2–3):163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaee H, Khalili H, Salamzadeh J, Jafari S, Abdollahi A. Potential benefits of carnitine in HIV-positive patients. Future Virol 2012; 7(1):73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waagsbo B, Svardal A, Ueland T, Landro L, Oktedalen O, Berge RK, et al. Low levels of short- and medium-chain acylcarnitines in HIV-infected patients. Eur J Clin Invest 2016; 46(5):408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassol E, Misra V, Morgello S, Kirk GD, Mehta SH, Gabuzda D. Altered Monoamine and Acylcarnitine Metabolites in HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Subjects With Depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(1):18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmon WG, Dadlani GH, Fisher SD, Lipshultz SE. Myocardial and Pericardial Disease in HIV. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2002; 4(6):497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanna DB, Post WS, Deal JA, Hodis HN, Jacobson LP, Mack WJ, et al. HIV Infection Is Associated With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(4):640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi Q, Hua S, Clish CB, Scott JM, Hanna DB, Wang T, et al. Plasma Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolites Are Altered in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Associated With Progression of Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis 2018:ciy053–ciy053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immun 2005; 12(9):1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR. The Multicenter Aids Cohort Study - Rationale, Organization, and Selected Characteristics of the Participants. Am J Epidemiol 1987; 126(2):310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Gange SJ, Benning L, Jacobson LP, Lazar J, et al. Low CD4+ T-cell count as a major atherosclerosis risk factor in HIV-infected women and men. Aids 2008; 22(13):1615–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna DB, Post WS, Deal JA, Hodis HN, Jacobson LP, Mack WJ, et al. HIV Infection Is Associated With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Atherosclerosis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(4):640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanna DB, Lin J, Post WS, Hodis HN, Xue XN, Anastos K, et al. Association of Macrophage Inflammation Biomarkers With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis in HIV-Infected Women and Men. J Infect Dis 2017; 215(9):1352–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, Van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 2007; 23(10):1294–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strand E, Pedersen ER, Svingen GF, Olsen T, Bjorndal B, Karlsson T, et al. Serum Acylcarnitines and Risk of Cardiovascular Death and Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Stable Angina Pectoris. Journal of the American Heart Association 2017; 6(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angelovich TA, Hearps AC, Maisa A, Martin GE, Lichtfuss GF, Cheng WJ, et al. Viremic and Virologically Suppressed HIV Infection Increases Age-Related Changes to Monocyte Activation Equivalent to 12 and 4 Years of Aging, Respectively. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaipersad AS, Lip GY, Silverman S, Shantsila E. The role of monocytes in angiogenesis and atherosclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014; 63(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rutkowsky JM, Knotts TA, Ono-Moore KD, McCoin CS, Huang S, Schneider D, et al. Acylcarnitines activate proinflammatory signaling pathways. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism 2014; 306(12):E1378–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adlouni HA, Katrib K, Ferard G. Changes in carnitine in polymorphonuclear leukocytes, mononuclear cells, and plasma from patients with inflammatory disorders. Clinical chemistry 1988; 34(1):40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.To KKW, Lee KC, Wong SSY, Lo KC, Lui YM, Jahan AS, et al. Lipid mediators of inflammation as novel plasma biomarkers to identify patients with bacteremia. J Infection 2015; 70(5):433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dominic EA, Ramezani A, Anker SD, Verma M, Mehta N, Rao M. Mitochondrial cytopathies and cardiovascular disease. Heart 2014; 100(8):611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madamanchi NR, Runge MS. Mitochondrial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2007; 100(4):460–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzetti E, Csiszar A, Dutta D, Balagopal G, Calvani R, Leeuwenburgh C. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and altered autophagy in cardiovascular aging and disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Physiol-Heart C 2013; 305(4):H459–H476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginsberg HN. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 2000; 106(4):453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy KJ, Singh M, Bangit JR, Batsell RR. The role of insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an updated review. J Cardiovasc Med 2010; 11(9):633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li T, Zhang Z, Kolwicz SC Jr., Abell L, Roe ND, Kim M, et al. Defective Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism Disrupts Glucose Metabolism and Sensitizes the Heart to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab 2017; 25(2):374–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Matute P, Perez-Martinez L, Blanco JR, Oteo JA. Role of Mitochondria in HIV Infection and Associated Metabolic Disorders: Focus on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Lipodystrophy Syndrome. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne BAI, Wilson IJ, Hateley CA, Horvath R, Santibanez-Koref M, Samuels DC, et al. Mitochondrial aging is accelerated by anti-retroviral therapy through the clonal expansion of mtDNA mutations. Nat Genet 2011; 43(8):806–U121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballocca F, Gili S, D’Ascenzo F, Marra WG, Cannillo M, Calcagno A, et al. HIV Infection and Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Lights and Shadows in the HAART Era. Progress in cardiovascular diseases 2016; 58(5):565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocr Metab 2007; 92(7):2506–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nduka C, Sarki A, Uthman O, Stranges S. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on serum lipoprotein levels and dyslipidemias: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2015; 199:307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galescu O, Bhangoo A, Ten S. Insulin resistance, lipodystrophy and cardiometabolic syndrome in HIV/AIDS. Rev Endocr Metab Dis 2013; 14(2):133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2007; 115(4):459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters SAE, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Carotid intima-media thickness: a suitable alternative for cardiovascular risk as outcome? Eur J Cardiov Prev R 2011; 18(2):167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haid M, Muschet C, Wahl S, Romisch-Margl W, Prehn C, Moller G, et al. Long-Term Stability of Human Plasma Metabolites during Storage at-80 degrees C. J Proteome Res 2018; 17(1):203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Chen Y, Xi C, Zhang R, Song Y, Zhan Q, et al. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry-Based Plasma Metabonomics Delineate the Effect of Metabolites’ Stability on Reliability of Potential Biomarkers. Analytical Chemistry 2013; 85(5):2606–2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Levels of aggregated acylcarnitine scores (mean, SD) by behavioral and HIV-related factors.

Table S2. Partial Spearman correlations of aggregated acylcarnitine scores with traditional CVD risk factors and HIV related factors.

Table S3. Associations of individual acylcarnitine species with incident carotid plaque.

Table S4. N (%) of ART class, combination and ART drug use among 394 ART users.

Figure S1. Spearmen correlations among acylcarnitine species.

Figure S2. Associations of aggregated short-, medium- and long-chain acylcarnitine scores with incident carotid artery plaque stratified by HIV infection related characteristics, stratified by: (a) baseline CD4 cell count, (b) baseline HIV RNA. Models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking, BMI, family history of cardiovascular disease, HCV infection, injection drug use, HIV serostatus, baseline CD4 cell count, NRTI use, NNRTI use, PI use, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Figure S3. Differences in individual acylcarnitine scores by ART class and ART drugs. Raw acylcarnitine concentrations were normalized with rank based inverse normal transformation by sex before analysis. *P-value <0.05 after FDR adjustment.