Abstract

Objective

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes (ASPs) have been widely implemented in large hospitals but little is known regarding small-to-medium-sized hospitals. This literature review evaluates outcomes described for ASPs participated in by clinical pharmacists and implemented in small-to-medium-sized hospitals (<500 beds).

Methods

Following PRISMA principles, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were searched in early 2016 for English language articles describing implementation and outcomes for inpatient ASPs participated in by clinical pharmacists in small-to-medium-sized hospitals. Each included study was required to include at least one of the following outcomes: microbiological outcomes, quality of care and clinical outcomes or antimicrobial use and cost outcomes.

Results

We included 28 studies from 26 hospitals, mostly American or Canadian. Most cases (23 studies) consisted of time-series comparisons of pre-and post-intervention periods. Of the 28 studies analysed, 8 reported microbiological outcomes, 21 reported quality of care and clinical outcomes, and 27 reported antimicrobial use and cost outcomes. Interventions were not generally associated with significant changes in mortality or readmission rates but were associated with substantial cost savings, mainly due to reduced use of antibiotics or the use of cheaper antibiotics.

Conclusion

As far as we are aware, ours is the first systematic review that evaluates ASPs participated in by clinical pharmacists in small-to-medium-sized hospitals. ASPs appear to be an effective strategy for reducing antimicrobial use and cost. However, the limited association with better microbiological, care quality and clinical outcomes would highlight the need for further studies and for standardised methods for evaluating ASP outcomes.

Keywords: clinical pharmacy, infectious diseases, pharmacotherapy, therapeutics, side effects of drugs

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing health problem worldwide that urgently needs to be tackled. Several studies have demonstrated that up to 50% of antimicrobial prescriptions in Europe and the USA are considered inappropriate.1 Infections involving multidrug-resistant microorganisms and Clostridium difficile have been shown to increase hospital stays, healthcare costs and mortality,2 and to be associated with misuse and overuse of certain antibiotics.3–5 Additionally, the decreased use of restricted agents is associated with a parallel increase in the prescription of other antimicrobials that may facilitate the development of yet other types of resistant microorganisms, a phenomenon known as ‘squeezing the balloon’.6 7

A tool for rationalising antibiotic use in healthcare facilities is an antimicrobial stewardship programme (ASP), defined as an ongoing effort by a hospital to optimise antimicrobial use in order to improve patient outcomes, reduce adverse events associated with antimicrobial use (including antimicrobial resistance) and ensure cost-effective therapy.8 ASPs, implemented through multidisciplinary teams, monitor all aspects of antibiotic use – from selection and indication to factors related with time – but focus especially on four main measures: antibiotic use, clinical parameters, antibiotic resistance and cost.9 Guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) indicate that ASP teams should include, as core members, an infectious disease physician and a clinical pharmacist with training in infectious diseases.10 Two types of interventions have been described for an ASP: in formulary restriction with prior authorisation, antibiotics are administered according to a certain set of patient- or antibiotic-specific criteria, whereas in prospective auditing with feedback, ASP team members interact directly with prescribers to optimally tailor antimicrobial therapy to each patient after initial drug prescription and dispensation.11 A Cochrane systematic review states that it remains unclear which of the interventions is better since no direct comparison has been made between them.12

ASPs to date have typically been implemented in large teaching hospitals with substantial financial and human resources. However, for two time periods (2000–2004 vs 1990–1994), it has been shown that the greatest increase in multidrug-resistant microorganisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa was in hospitals with fewer than 200 beds.13 Community hospitals thus need to develop strategies adapted to their size, staffing and infrastructure as well as to specific and localised patterns of resistance.14

Clinical pharmacists are likely to play a greater role in community hospitals since they may personally review all antimicrobial prescriptions and hold face-to-face discussions with medical and nursing staff and so reinforce the message.15 Although infectious-disease clinical pharmacists may have several antimicrobial-related tasks (eg, producing evidence-based prescribing guidelines, educating prescribers in the prudent use of antimicrobials, supporting prescribers in optimising antimicrobial therapy for individual patients, advising on therapeutic drug monitoring and managing new antimicrobials in hospital formularies), the lack of good-quality evidence of their impact on optimising antimicrobial therapy and patient outcomes would indicate an urgent need for research in this area.16

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the implementation and outcomes of ASPs participated in by clinical pharmacists in small-to-medium-sized hospitals (fewer than 500 beds).

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) principles for systematic reviews were applied. The PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were searched in April 2016 for English language articles describing pharmacist-participated inpatient ASPs and their outcomes for small-to-medium-sized hospitals (fewer than 500 beds) and further relevant articles were identified from cross-references. Hospitals with fewer than 500 beds were defined as small-to-medium-sized hospitals since they accounted for 94% of American Hospital Association-defined community hospitals in 2013 and 78% of acute care facilities reporting to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2015.17 18

Articles selected for initial review had the following terms in their titles or abstracts: ‘antimicrobial stewardship programms’; ‘antimicrobial stewardship program’; ‘antimicrobial stewardship programmes’; ‘antimicrobial stewardship programme’; ‘antimicrobial stewardship community hospital’; ‘antimicrobial control’; ‘antibiotic control’ or ‘antibiotic stewardship’. Selection was further limited to those studies that also contained the following terms in the titles or abstracts: ‘clinical pharmacist’; ‘pharmacists’; ‘clinical pharmacy’; ‘pharmacy’; ‘pharmacist’; ‘pharmacist interventions’; ‘community hospital’; ‘community hospitals’; or ‘pharmaceutical care’.

Selected for review from the studies meeting the above initial selection criteria were articles reporting ASP evaluations and outcomes in inpatient settings with the participation of at least one clinical pharmacist, provided the full text was accessible via PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the library of the Autonomous University of Barcelona or could be obtained directly from the authors. Multicentre studies were excluded because it is difficult to guarantee similarity in the characteristics of hospitals, patients and methodologies.

From each of the above studies, two reviewers independently extracted the following information:

General characteristics. City and country, hospital size (number of beds), patient exclusion criteria, number of patients, mean/median age of patients, whether the ASP was run for a specific department or the entire hospital, study design, study duration, inclusion of antivirals and antifungals, ASP team members and ASP strategies.

Microbiological outcomes. Changes in antibiotic susceptibility, incidence of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms and C. difficile infection, and proportion of sterile/non-sterile site cultures treated.

Care quality and clinical outcomes. Length of stay, improvement in patient chart documentation details, mortality rates, readmission rates, number of pharmacotherapeutic interventions and acceptance rates, adverse events and physician satisfaction regarding ASP interventions.

Antimicrobial use and cost. Antimicrobial costs, personnel costs, implementation costs and total cost savings.

Risk-of-bias assessment

We applied the 2016 Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) risk-of-bias criteria to all papers included in this review.19 Studies were scored for risk of bias as follows: low, if all criteria were scored as ‘low’; medium, if one or two criteria were scored as ‘unclear’ or ‘high’; and high if three or more criteria were scored as ‘unclear’ or ‘high’.20

Results

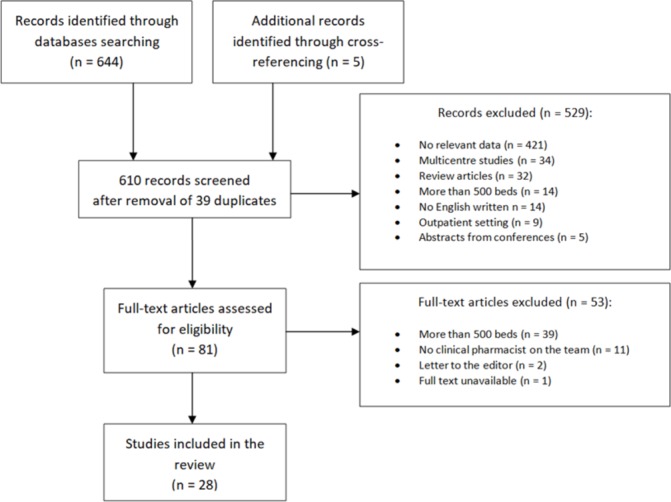

Our search identified 644 titles and abstracts and five additional articles identified through cross-referencing (total 649 studies), of which only 28 studies met eligibility criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. Reasons for excluding other studies are explained in the screening flow chart in figure 1. Letters to the editor and abstracts from conferences were excluded since they frequently lack the data necessary to evaluate methodological quality.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing screening process.

General characteristics

Online supplementary table 1 summarises setting, ASP team compositions, study designs, study durations and stewardship intervention types for the 28 included studies. The 28 studies described formal ASPs in 26 hospitals of different sizes: fewer than 100 beds (n=1); 100–200 beds (n=6); 201–300 beds (n=5); 301–400 beds (n=6); and 401–500 beds (n=8). Most of the studies referred to the USA or Canada (n=21). ASP strategies implemented were as follows: prospective auditing with feedback (n=17); preauthorised formulary restriction (n=4); and both strategies (n=7). ASP teams comprised at least one physician and one pharmacist and, in most cases (22 studies), the ASP was rolled out across the entire hospital. Most cases (23 studies) consisted of a time-series comparison of the pre-and post-intervention periods, and the remaining five studies were randomised controlled trials (n=3), a prospective interventional study (n=1) and a quasi-experimental stepped-wedge controlled study (n=1). In most cases (21 studies) the intervention period ranged between 1 and 3 years. Regarding antimicrobial classes, only 5 and 11 studies reported including antiviral drugs and antifungal drugs, respectively, in their analysis. Finally, the number of patients reviewed by the ASP team was only clearly specified in 17 of the 28 studies: these reported numbers of 14 to 8765 patients for the intervention group/period (age range: 56–78.3 years for adult studies and 2.5–8.5 years for paediatric studies). In the nine studies that clearly highlighted exclusion criteria, the most frequently applied criteria were paediatric patients (four studies) and patients with cystic fibrosis (two studies).

ejhpharm-2017-001381supp001.docx (31.5KB, docx)

Microbiological outcomes

Most studies did not report statistically significant results for microbiological outcomes (online supplementary table 2). One study reported cumulative susceptibilities to specific organism-antibiotic combinations such as Enterobacter aerogenes, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.21 Another study highlighted a drop in the rate of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas spp. from 6% to 1% despite rates for ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella spp. and ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas spp. increasing from 12% to 42% and from 4% to 14%, respectively.22 Another study reported a higher proportion of sterile-site cultures and a lower proportion of non-sterile site cultures being treated after ASP implementation.23 Two studies reported a significant decrease in the annual C. difficile rate: from 0.11 to 0.07 per 1000 patient-days21 and from 5.5 to 1.6 cases per 10 000 patient-days.24 Finally, contradictory results were reported for MRSA infections, with two studies reporting a decrease in monthly rates from 2.9 to 1.5 cases per 1000 patient-days25 and a decrease from 50% to 34% of all clinical isolates,26 but with two other studies reporting higher rates of MRSA infections in the post-intervention period27 28 and a decrease in the number of patients with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection (from 10 to 2 cases annually), while the number of patients with vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus infection increased.28

ejhpharm-2017-001381supp002.docx (33.3KB, docx)

Quality of care and clinical outcomes

The number of ASP-proposed pharmacotherapeutic interventions implemented by physicians was not reported by 13 studies, and the remaining 15 studies reported 10 to 2457 interventions (obviously dependent on study length). Interventions differed between studies and not all were described in detail. Intervention acceptance rates ranged from 50.5% to 94%, with 4 of the 28 studies reporting acceptance rates of more than 90%. None of the studies reported significant drops in readmission rates after ASP implementation, but one study reported reduced hospital stays for the intervention group29 and another study reported reduced mortality and reduced stays (of around 2.4 days) for patients with infections.26 Contradictory results were reported, however, for length of stay for patients with community-acquired pneumonia.30 31 One study reported chart documentation improvements for intensive-care unit (ICU) patients in terms of antimicrobial indication, dosage, stop dates and de-escalation after the ASP was initiated.23 Only six of the studies collected data on possible adverse outcomes associated with ASP-related pharmacotherapeutic interventions, but no study recorded any actual adverse event. Four studies reported increased physician satisfaction with ASP interventions most notably, an increase from 22% to 68% after implementation of an online ASP.32 A further three studies reported greater physician confidence in pharmaceutical and antimicrobial recommendations after implementing an ASP.24 29 33

Antimicrobial use and cost outcomes

Twenty-two and 19 studies reported outcomes for antimicrobial use and cost, respectively (online supplementary table 2). The 22 studies reporting data on use indicated decreased antimicrobial use after ASP rollout, although the specific metrics differed between studies. Some studies reported decreases in general antimicrobial use22 23 31–37 or decreases in certain targeted antibiotics such as the carbapenems,30 35 38–40 linezolid35 and daptomycin.30 Despite curtailment of general or targeted antimicrobials, increased use was reported for specific antibiotics such as the beta-lactams,21 30 35 37 40 quinolones21 38 and clindamycin.28 37 As for the 19 studies with data on cost, all reported decreased antimicrobial spending after ASP rollout: nine reported pre- and post-ASP implementation comparisons between antibiotic cost per inpatient-days;23–25 33–35 39 41 42 and 11 reported reductions in antimicrobial purchase costs of between 17% and 69%.22 23 26 29 30 32 33 37–39 43 Finally, only three studies reported annual personnel costs, at $22,092,29 $47,22041 and $121,300.38 None of the 19 studies reporting cost data included information regarding the actual ASP cost.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk of bias was low for eight studies,22 23 27 28 30 37 40 42 medium for 12 studies25 26 31 32 34–36 38 39 41 45 46 and high for eight studies.21 24 29 33 43 44 47 48

Discussion

No clear conclusions can be drawn from the results of our review of inpatient ASPs rolled out in small-to-medium-sized hospitals, other than regarding benefits in terms of reduced antimicrobial use and cost.

The importance of ASPs as national strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing is widely recognised, to the point where ASPs are now included in regulatory frameworks, some of which include provisions for healthcare providers to put an ASP in place.49 We evaluated 28 studies referring to small-to-medium-sized hospitals a similar number of studies to reviews referring to larger hospitals.50–52 As with the larger hospitals, for small-medium-sized hospitals there is still limited evidence for the impact of ASPs on patient outcomes, mainly because many of the studies have methodological limitations, include few patients or have short follow-up periods.

Although optimising clinical outcomes is the primary goal of ASPs, results for mortality, hospital readmission and length of stay were rarely reported, and if reported, were mostly non-significant. Only one study in our review found an association between ASP implementation and a drop in mortality rates.26 For larger hospitals, ASP implementation was not associated with reductions in mortality or readmission rates, and contradictory results have been reported for length of stay.50–52 However, both small-to-medium-sized and large hospitals seem to obtain positive results in terms of antimicrobial use and cost savings, and ASP implementation appears not to be associated with adverse outcomes.50 51 We suggest that the fact that ASPs are not associated with increases in mortality rates or hospital readmissions is of paramount importance, since it demonstrates that ASPs are not harmful for patients but are likely to produce important cost savings for the hospital.

Individual strategies should be taken into account if a full ASP cannot be implemented. For instance, an infection team could focus on sequential therapy (a systematic plan to switch from parenteral to oral antimicrobials with excellent bioavailability) and so achieve shorter stays, fewer nosocomial infections and lower healthcare costs.53 If an ASP cannot be rolled out in the entire hospital, it could be targeted in especially appropriate areas such as the emergency or surgical departments,54 55 or, as happened in three studies in our review, the ICU.23 34 39

Results regarding microbiological outcomes would appear to depend on the pathogen. Although two studies in our review found a significant decrease in the annual C. difficile rate,21 24 contradictory results were found for MRSA27 28 and for ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella spp. and ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas spp. 22 Regarding MRSA, the two studies reporting higher MRSA rates during the ASP rollout period may not be truly representative, as they were focused on reducing vancomycin use in a paediatric setting.27 28 As for the increases reported for ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella spp. and ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas spp.,22 these were attributed to decreased carbapenem and increased cephalosporin prescriptions, a phenomenon widely recognised as ‘squeezing the balloon’.6

The benefits of ASPs were especially evident in antimicrobial use and cost outcomes. Leaving aside a study that did not evaluate these parameters44 and another study that found limited efficacy for these outcomes,48 all the remaining 26 studies described significant decreases in antimicrobial use or cost. The fact that some studies provided no information regarding reasons for switching antimicrobials or reducing antimicrobial use limits the usefulness of those results when it comes to evaluating whether or not guidelines were followed. Note that none of the studies included accurate information on the cost of the ASP itself and each study used different metrics for ASP results — both issues that have been widely discussed. A recent systematic review has indicated, for instance, that without such information it is impossible to compare studies or draw general conclusions regarding the financial benefits of ASPs.56 All this would suggest that much more work remains to be done, both to improve this kind of study and to conduct formal financial studies that calculate the real impact of ASP implementation.

As far as we are aware, ours is the first systematic review that evaluates ASPs involving clinical pharmacists in small-to-medium-sized hospitals — a setting where it is recognised that most work is needed.13 14 Our review, however, confirms the important role played by clinical pharmacists and infectious disease physicians in ASP implementation in the 28 evaluated studies. A European cross-sectional study of 263 hospitals (with a median of 669 beds) showed that antibiotic consumption was lower when a pharmacist worked with the prescriber.57 There is also evidence that availing of a pharmacist specialising in infectious diseases, as opposed to a ward pharmacist, may ensure greater adherence to antimicrobial therapy recommendations.58 Interestingly, the British National Health Service reported a significant increase in absolute numbers of antimicrobial-specialist pharmacy staff between 2005 and 2011.59

Our systematic review has a number of limitations. First, although we tried to mine the maximum number of relevant studies using a wide range of specific search terms, we may have missed out on some studies depending on how authors described their paper, wrote their title and abstract, or chose their key words. Furthermore, the full text was unavailable for one study that appeared to meet with all the inclusion criteria (although we could not be sure that the hospital had under 500 beds), but it is unlikely that this single paper could change the conclusions of our review.60 Second, we could not consult Embase since we did not have access to this database. Nonetheless, we suggest that articles found in PubMed and the Cochrane Library are sufficiently representative of published evidence on this topic. Third, although it is likely that more than 26 small-to-medium-sized hospitals have implemented ASPs in recent decades, we cannot rule out the possibility that many of them found negative results — and it is well known that negative results are less likely to be published than positive results.61 Fourth, since around two-thirds of the included studies had medium or high risk-of-bias scores, additional clinical trials in small-to-medium-sized hospitals that compare antibiotic stewardship with no intervention could well change our conclusions. Fifth, 21 of the 28 studies were performed in the USA (n=17) or Canada (n=4), so their results cannot be extrapolated to hospitals located in other countries. What is remarkable is the lack of studies for European hospitals (we identified only one study for Europe), as such studies would, naturally, be useful for comparison with results for the USA and Canada. Finally, the objectives and conclusions of the individual studies were variable, which makes it difficult to draw any clear conclusion regarding the clinical benefits of ASP implementation involving clinical pharmacists in small-to -medium-sized hospitals.

Conclusion

Our review of ASPs involving clinical pharmacists rolled out in small-to-medium-sized hospitals would indicate that ASPs are effective in decreasing both antimicrobial use and cost. What remains unclear, however, is the association with better clinical, care quality and microbiological outcomes. This highlights the need for more studies and for standardised methods for evaluating ASP outcomes.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes are widely implemented in large hospitals but evidence about their usefulness in small-to-medium-sized hospitals is lacking.

The clinical pharmacist as an expert in pharmacotherapy can play a crucial role in this setting.

What this study adds?

Implementing an antimicrobial stewardship programme that involves clinical pharmacists in a small-to-medium-sized hospital is an effective approach in decreasing antimicrobial use and cost.

More studies are urgently needed to demonstrate ASP correlation with better microbiological, care quality and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Ailish Maher, who reviewed English usage in the final version of this manuscript.

This article is part of a PhD thesis in pharmacology (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain) authored by PM-M.

Footnotes

Funding: MV was supported by a grant (FIS CP04/00121) from the Spanish Ministry of Health in collaboration with Institut de Recerca de l’Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona: she is a member of CIBERSAM (funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III attached to the Spanish Ministry of Health).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Aryee A, Price N. Antimicrobial stewardship – can we afford to do without it? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;79:173–81. 10.1111/bcp.12417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cosgrove SE. The relationship between antimicrobial resistance and patient outcomes: mortality, length of hospital stay, and health care costs. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42(Suppl 2):S82–89. 10.1086/499406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aldeyab MA, Harbarth S, Vernaz N, et al. The impact of antibiotic use on the incidence and resistance pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in primary and secondary healthcare settings. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:171–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04161.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aldeyab MA, Monnet DL, López-Lozano JM, et al. Modelling the impact of antibiotic use and infection control practices on the incidence of hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a time-series analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:593–600. 10.1093/jac/dkn198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hensgens MP, Goorhuis A, Dekkers OM, et al. Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:742–8. 10.1093/jac/dkr508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burke JP. Antibiotic resistance – squeezing the balloon? JAMA 1998;280:1270–1. 10.1001/jama.280.14.1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aldeyab MA, Kearney MP, McElnay JC, et al. A point prevalence survey of antibiotic prescriptions: benchmarking and patterns of use. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;71:293–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03840.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MacDougall C, Polk RE. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in health care systems. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18:638–56. 10.1128/CMR.18.4.638-656.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacob JT, Gaynes RP. Emerging trends in antibiotic use in US hospitals: quality, quantification and stewardship. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2010;8:893–902. 10.1586/eri.10.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Infectious diseases society of america and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:159–77. 10.1086/510393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Griffith M, Postelnick M, Scheetz M. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: methods of operation and suggested outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2012;10:63–73. 10.1586/eri.11.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD003543 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Gaynes RP. The impact of antimicrobial-resistant, health care-associated infections on mortality in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:927–30. 10.1086/591698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohl CA, Dodds Ashley ES. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in community hospitals: the evidence base and case studies. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53(Suppl 1):S23–8. 10.1093/cid/cir365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weller TM, Jamieson CE. The expanding role of the antibiotic pharmacist. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004;54:295–8. 10.1093/jac/dkh327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilchrist M, Wade P, Ashiru-Oredope D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship from policy to practice: experiences from UK antimicrobial pharmacists. Infect Dis Ther 2015;4(Suppl 1):51–64. 10.1007/s40121-015-0080-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf (accessed 15 Feb 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dudeck MA, Edwards JR, Allen-Bridson K, et al. National healthcare safety network report, data summary for 2013, device-associated module. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:206–21. 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC Resources for review authors. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, 2016. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors (accessed 15 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davey P, Marwick CA, Scott CL, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD003543 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Tawfiq JA, Momattin H, Al-Habboubi F, et al. Restrictive reporting of selected antimicrobial susceptibilities influences clinical prescribing. J Infect Public Health 2015;8:234–41. 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Magedanz L, Silliprandi EM, dos Santos RP. Impact of the pharmacist on a multidisciplinary team in an antimicrobial stewardship program: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:290–4. 10.1007/s11096-012-9621-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katsios CM, Burry L, Nelson S, et al. An antimicrobial stewardship program improves antimicrobial treatment by culture site and the quality of antimicrobial prescribing in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2012;16:R216–24. 10.1186/cc11854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yam P, Fales D, Jemison J, et al. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program in a rural hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012;69:1142–8. 10.2146/ajhp110512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fukuda T, Watanabe H, Ido S, et al. Contribution of antimicrobial stewardship programs to reduction of antimicrobial therapy costs in community hospital with 429 beds – before-after comparative two-year trial in Japan. J Pharm Policy Pract 2014;7:10–16. 10.1186/2052-3211-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gentry CA, Greenfield RA, Slater LN, et al. Outcomes of an antimicrobial control program in a teaching hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2000;57:268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gillon J, Xu M, Slaughter J, et al. Vancomycin use: room for improvement among hospitalized children. J Pharm Pract 2017;30:296–9. 10.1177/0897190016635478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Di Pentima MC, Chan S. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin use in a pediatric teaching hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29:707–11. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d683f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gums JG, Yancey RW, Hamilton CA, et al. A randomized, prospective study measuring outcomes after antibiotic therapy intervention by a multidisciplinary consult team. Pharmacotherapy 1999;19:1369–77. 10.1592/phco.19.18.1369.30898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Waters CD. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial stewardship program in an institution without infectious diseases physician support. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2015;72:466–8. 10.2146/ajhp140381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DiDiodato G, McArthur L, Beyene J, et al. Evaluating the impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on the length of stay of immune-competent adult patients admitted to a hospital ward with a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia: a quasi-experimental study. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:e73–9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Agwu AL, Lee CK, Jain SK, et al. A world wide web-based antimicrobial stewardship program improves efficiency, communication, and user satisfaction and reduces cost in a tertiary care pediatric medical center. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:747–53. 10.1086/591133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bartlett JM, Siola PL. Implementation and first-year results of an antimicrobial stewardship program at a community hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014;71:943–9. 10.2146/ajhp130602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taggart LR, Leung E, Muller MP, et al. Differential outcome of an antimicrobial stewardship audit and feedback program in two intensive care units: a controlled interrupted time series study. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:480–90. 10.1186/s12879-015-1223-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Storey DF, Pate PG, Nguyen AT, et al. Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program on the medical-surgical service of a 100-bed community hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2012;1:32–9. 10.1186/2047-2994-1-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012;1:179–86. 10.1093/jpids/pis054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mercer KA, Chintalapudi SR, Visconti EB. Impact of targeted antibiotic restriction on usage and cost in a community hospital. J Pharm Tech 1999;15:79–84. 10.1177/875512259901500303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vettese N, Hendershot J, Irvine M, et al. Outcomes associated with a thrice-weekly antimicrobial stewardship programme in a 253-bed community hospital. J Clin Pharm Ther 2013;38:401–4. 10.1111/jcpt.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leung V, Gill S, Sauve J, et al. Growing a ’positive culture' of antimicrobial stewardship in a community hospital. Can J Hosp Pharm 2011;64:314–20. 10.4212/cjhp.v64i5.1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Di Pentima MC, Chan S, Hossain J. Benefits of a pediatric antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics 2011;128:1062–70. 10.1542/peds.2010-3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lin YS, Lin IF, Yen YF, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program with multidisciplinary cooperation in a community public teaching hospital in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control 2013;41:1069–72. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benson JM. Incorporating pharmacy student activities into an antimicrobial stewardship program in a long-term acute care hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2014;71:227–30. 10.2146/ajhp130321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Potasman I, Naftali G, Grupper M. Impact of a computerized integrated antibiotic authorization system. Isr Med Assoc J 2012;14:415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Pentima MC, Chan S, Eppes SC, et al. Antimicrobial prescription errors in hospitalized children: role of antimicrobial stewardship program in detection and intervention. Clin Pediatr 2009;48:505–12. 10.1177/0009922808330774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cairns KA, Jenney AW, Abbott IJ, et al. Prescribing trends before and after implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship program. Med J Aust 2013;198:262–6. 10.5694/mja12.11683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ullman MA, Parlier GL, Warren JB, et al. The economic impact of starting, stopping, and restarting an antibiotic stewardship program: a 14-year experience. Antibiotics 2013;2:256–64. 10.3390/antibiotics2020256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Danaher PJ, Milazzo NA, Kerr KJ, et al. The antibiotic support team – a successful educational approach to antibiotic stewardship. Mil Med 2009;174:201–5. 10.7205/MILMED-D-00-1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Masiá M, Matoses C, Padilla S, et al. Limited efficacy of a nonrestricted intervention on antimicrobial prescription of commonly used antibiotics in the hospital setting: results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008;27:597–605. 10.1007/s10096-008-0482-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ashiru-Oredope D, Sharland M, Charani E, et al. Improving the quality of antibiotic prescribing in the NHS by developing a new antimicrobial stewardship programme: start smart-then focus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67(Suppl 1):i51–i63. 10.1093/jac/dks202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wagner B, Filice GA, Drekonja D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in inpatient hospital settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:1209–28. 10.1086/678057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Karanika S, Paudel S, Grigoras C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical and economic outcomes from the implementation of hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship programs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016;60:4840–52. 10.1128/AAC.00825-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Filice G, Drekonja D, Greer N, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in inpatient settings: a systematic review. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US), 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Calbo E, Alvarez-Rocha L, Gudiol F, et al. A review of the factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2013;31(Suppl 4):12–15. 10.1016/S0213-005X(13)70127-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, et al. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract 2012;25:190–4. 10.1177/0897190011420160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grill E, Weber A, Lohmann S, et al. Effects of pharmaceutical counselling on antimicrobial use in surgical wards: intervention study with historical control group. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:739–46. 10.1002/pds.2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dik JW, Vemer P, Friedrich AW, et al. Financial evaluations of antibiotic stewardship programs – a systematic review. Front Microbiol 2015;6:317–24. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. MacKenzie FM, Gould IM, Bruce J, et al. The role of microbiology and pharmacy departments in the stewardship of antibiotic prescribing in European hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2007;65(Suppl 2):73–81. 10.1016/S0195-6701(07)60019-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bessesen MT, Ma A, Clegg D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: comparison of a program with infectious diseases pharmacist support to a program with a geographic pharmacist staffing model. Hosp Pharm 2015;50:477–83. 10.1310/hpj5006-477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wickens HJ, Farrell S, Ashiru-Oredope DA, et al. The increasing role of pharmacists in antimicrobial stewardship in English hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68:2675–81. 10.1093/jac/dkt241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Puckett F, Baars R, Seay K. Antibiotic use review using the ’target drug' method. Hosp Formul 1987;22:489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Patel D, Lawson W, Guglielmo BJ. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: interventions and associated outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2008;6:209–22. 10.1586/14787210.6.2.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2017-001381supp001.docx (31.5KB, docx)

ejhpharm-2017-001381supp002.docx (33.3KB, docx)