Abstract

Due to their vital function, the wall structures of medium and large arteries are immunoprivileged and protected from inflammatory attack. This vascular immunoprivilege is broken in atherosclerosis and in vasculitis, when wall-invading T-cells and macrophages promote tissue injury and maladaptive repair. Historically, tissue-residing T-cells were studied for their antigen specificity, but recent progress has refocused attention to antigen-nonspecific regulation, which determines tissue access, persistence, and functional differentiation of T-cells. The co-inhibitory receptor PD-1, expressed on T-cells, delivers negative signals when engaged by its ligand PD-L1, expressed on dendritic cells, macrophages, and endothelial cells; to attenuate T cell activation, effector functions and survival. Through mitigating signals, the PD-1 immune checkpoint maintains tissue tolerance. In line with this concept, dendritic cells, and macrophages from patients with the vasculitic syndrome giant cell arteritis (GCA) are PD-L1lo; including vessel-wall embedded DC that guard the vascular immunoprivilege. GCA infiltrates in the arterial walls are filled with PD-1+ T-cells that secrete IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-21, drive inflammation-associated angiogenesis and facilitate intimal hyperplasia. Conversely, chronic tissue inflammation in the atherosclerotic plaque is associated with an overreactive PD-1 checkpoint. Plaque-residing macrophages are PD-L1hi, a defect induced by their addiction to glucose and glycolytic breakdown. PD-L1hi macrophages render patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) immunocompromised and suppress anti-viral immunity, including protective anti-varicella zoster virus T-cells. Thus, immunoinhibitory signals affect several domains of vascular inflammation: Failing PD-L1 in vasculitis enables unopposed immuno-stimulation and opens the flood gates for polyfunctional inflammatory T-cells and excess PD-L1 in the atherosclerotic plaque disables tissue-protective T-cell immunity.

INTRODUCTION

T cells and macrophages are key perpetrators of chronic vascular inflammation, representing the adaptive and innate arm of the immune system in disease pathogenesis. The most frequent form of blood vessel inflammation is atherosclerosis, now recognized as a slowly progressing inflammatory response that begins during the 2nd-3rd decade of life and leads to clinical complications 40–60 years later [1–4]. Lipids deposited below the endothelial layer are believed to attract immune cells. Immuno-stromal interactions eventually lead to the formation of the atherosclerotic plaque, a lesion that obstructs blood flow, but more importantly, can rupture to give rise to sudden atherothrombosis and vascular occlusion [5]. Clinical outcomes include myocardial infarction, stroke, and tissue ischemia.

A much more violent form of vascular inflammation are the vasculitides, causing vessel wall destruction within days to weeks. Vasculitides affecting the aorta and its major branch vessels (medium and large vessel vasculitides) are closest to atherosclerotic disease in targeting select vascular beds, building intramural infiltrates, and triggering vessel wall remodeling [6]. Vasculitic damage includes inflammation-induced angiogenesis, fast and concentric intimal hyperplasia and, in the aorta, wall thinning and aneurysm formation. Rupture or erosion of the vascular lesion is not a feature of vasculitis. Most cases of aortitis and large vessel vasculitis are caused by giant cell arteritis (GCA) [7–9], a disease with a stringent tissue tropism (aorta and 2nd-5th branches), rapid course and downstream organ ischemia. Similarities in T cell/ macrophage participation and in tissue patterning encourage a comparative analysis between GCA and coronary artery disease (CAD), to better understand the immunopathology and to explore potential strategies for immunomodulatory therapy.

To generate protective and pathogenic immune responses, T cells receive signals delivered through the antigen-specific T cell receptor (TCR) but the intensity, the duration and the tissue-damaging potential of such T-cell responses is equally shaped by co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors [10, 11], which amplify or attenuate the T-cell activation cascade. Most prominent amongst the co-stimulatory molecules is CD28 [12], which by binding to B7 family ligands critically amplifies TCR-derived signals to enhance T cell expansion and effector functions. Of equal importance, and of even higher clinical relevance, are the receptors sending inhibitory signals, including CTLA-4 and PD-1. Now known as immune checkpoints, CTL4–4 and PD-1 can block the induction of T-cell effector functions by targeting proximal signals and profoundly shape the nature of the developing immune response [13–15].

PD-1 is exclusively expressed on activated immune cells, most importantly on T cells, thus exclusively regulating ongoing immune responses, both in secondary lymphoid organs and in peripheral tissue sites. Engagement of PD-1 by its ligand PD-L1 (B7-H1, CD274) downregulates TCR and CD28-mediated activation cascades. PD-1 inhibits signaling pathways involved in glucose metabolism and cell cycle regulation, including the PI3K–Akt–mTOR and Ras–MEK–ERK pathways, thus impacting critical survival functions in normal tissues [16–18]. PD-L1 is expressed on antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells, macrophages etc) and on endothelial cells (EC). In animal studies, the PD-1 immune checkpoint has been implicated in protecting tissue tolerance and disruption of PD-1 and PD-L1-associated negative signaling has been associated with inflammatory disease [19–21]. Remarkably, PD-L1 is often abundantly expressed in cancer cells, and has been implicated in the immune evasion strategy of malignant cells, that paralyze anti-tumor T cells by engaging their PD-1 receptors. Accordingly, therapeutic blockade of PD-1 or PD-L1 in cancer patients has heralded in a revolution in cancer immunotherapy.

Given the role of immunoinhibitory signals in shaping ensuing effector and memory T cell populations, thus determining the long-term outcome of chronic immunity, we will review recent progress in understanding how the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway affects the immuno-pathogenesis of human blood vessel disease, exemplified in the slowly progressing CAD and the rapidly proceeding GCA.

1. PD-L1LO IMMUNOSTIMULATORY DENDRITIC CELLS AND MACROPHAGES IN GIANT CELL ARTERITIS (GCA)

In mice, PD-L1 deficiency causes exacerbation of inflammatory disease, in line with a critical role for the ligand in T cell tolerance [19]. Recent reports have extended this concept to the immunopathogenesis of human disease; the vasculitic syndrome GCA [22].

GCA is an aggressive vasculitis predominantly found in the thoracic aorta, the subclavian-axillary arteries, the vertebral arteries, the ophthalmic artery, and optic-nerve supplying vessels. Coronary arteries are rarely affected, unless the inflammation of the aortic wall causes ostial occlusion and acute coronary syndrome. In contrast to CAD, GCA is associated with an extravascular component [23], characterized by an intense hepatic acute phase response (elevating CRP and ESR), muscle pains and constitutional symptoms.

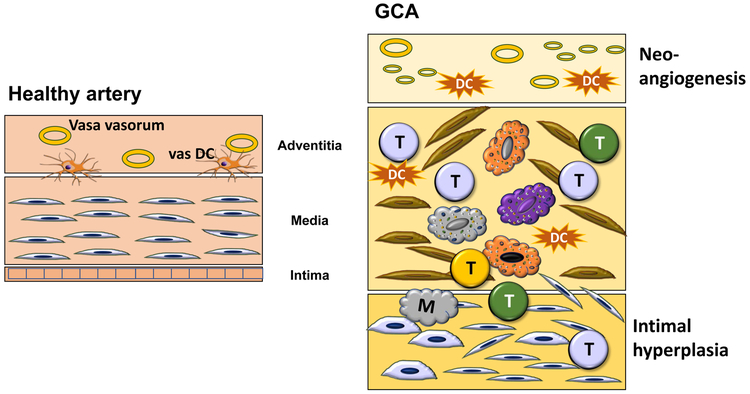

The histomorphology of GCA [24] describes granulomatous infiltrates, composed of T cells and highly activated macrophages. Some of the macrophages fuse into multinucleated giant cells, the namesake of the condition. Multiple different functional macrophage lineages have been distinguished, with a remarkable correlation between placement in the arterial wall and the functional commitment [25]. Typically, all wall layers (adventitia, media, intima) are infiltrated by T cells and macrophages, but critical functions have been assigned to the adventitial tissue niche. GCA is a quintessential example of failing tissue tolerance [26] (Fig.1).

Fig. 1: Breakdown of Tissue Tolerance in Giant Cell Arteritis.

The normal vessel wall has three layer: the vasa-vasorum containing adventitia; the elastic media; and a thin intima composed of 1-2 layers of endothelial cells. In GCA, disease inducing T cells and macrophages enter the vessel wall through the intima, infiltrate into the media and form granulomatous arrangements. Wall remodeling includes neo-angiogenesis of micro-vessles and mobilization of myofibroblasts that create a hyperplastic and lumen-occlusive intima.

T; T cell

M; macrophage

DC; dendritic cell

The adventitia harbors two elements of critical disease importance: (1) adventitial microvascular networks, that supply the vessel wall with oxygen and nutrient and (2) wall-residing dendritic cells, so-called vascular dendritic cells (vasDC), that are placed at the outside of the adventitia-media border [27]. Adventitial microvascular structures participate in the disease by expressing Jagged1 on the lining endothelial cells. Jagged1+ micro-endothelial cells provide stimulating signals to interacting T cells that express the Jagged1 receptor NOTCH1 [28]. Local stimulation opens the door to T cells, which are then able to enter an otherwise immuno-privileged tissue zone.

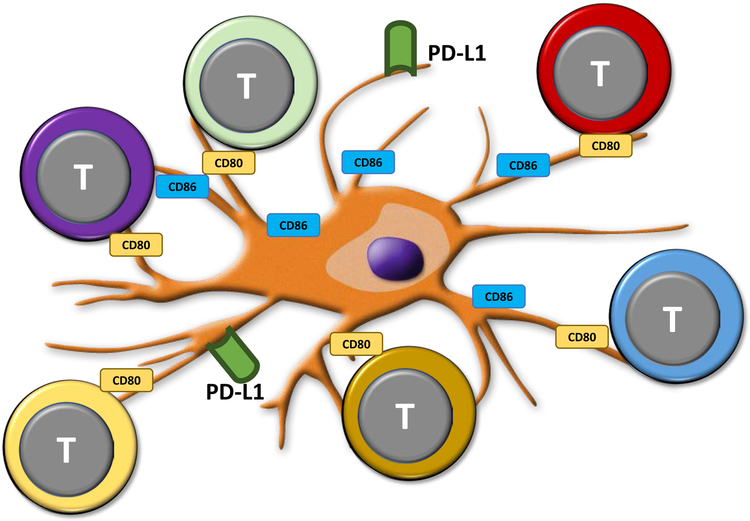

A critical protection mechanism avoiding immune cell infiltrates into the vessel wall comes from wall-embedded DC. Spontaneously, these wall-residing DC [29] are positive for PD-L1, providing a negative signal to all those T cells that express PD-1. This mechanism should close access to all activated PD-1+ T cells and this mechanism fails in GCA [29] (Fig.2). Temporal artery biopsies lesions from patients with active GCA are densely filled with DC [30], yet they lack PD-L1. Ex vivo differentiated DC from blood precursor cells of patients and age-matched controls demonstrate significantly lower PD-L1 surface density, while co-stimulatory ligands are present at similar amounts [29]. Functionally, such PD-L1lo DC fail to attenuate T cell responses, creating unopposed T cell stimulation (Fig.2). Interestingly, PD-L1 expression on patient-derived DC correlated inversely with systemic inflammatory markers, compatible with a role of PD-L1lo DC in overall immune regulation. PD-L1lo DC from GCA patients are competent in other DC functions (production of cytokines and chemokines). Failing PD-L1 expression is a feature of DC, monocytes and macrophages, emphasizing the systemic character of the defect.

Fig. 2: PD-L1lo dendritic cells stimulate a diverse array of T effector cells.

In GCA, both circulating and vessel-wall residing DC have low expression of the immunoinhibitory ligand PD-L1. The co-stimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86 are abundantly present. PD-L1lo CD86hi DC function as powerful activators of T cells, whose stimulation remains unrestrained due to the lack of engaging the negative receptor PD-1.

2. INSUFFICIENTLY SUPPRESSED T CELLS IN GIANT CELL ARTERITSI (GCA)

Failure of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint in GCA can be mimicked in a humanized mouse model of GCA, providing insights into the functional consequences of insufficient co-inhibition. In this model, human arteries are engrafted into immunocompromised mice and such chimeric mice are reconstituted with monocytes and T cells from patients with GCA [28, 29, 31]. Vasculitis develops in the implanted human artery within 7–10 days. Vasculitic arteries are then explanted and used for transcriptome analysis, immunostaining experiments, isolation of tissue-residing cells etc. Treatment of mice carrying vasculitic arteries with blocking anti-PD-1 antibodies was used to dismantle the checkpoint and define functional outcomes in arteries unprotected by PD-1 signaling. Eliminating PD-1 signaling caused fulminant vasculitis [29]. Interesting, when PD-1 was blocked even monocytes and T cells from healthy individuals could enter the arterial wall and establish inflammation, albeit to a much lower degree than the patients’ cells, supporting the concept that the PD-1 checkpoint is critically important in maintaining tissue tolerance.

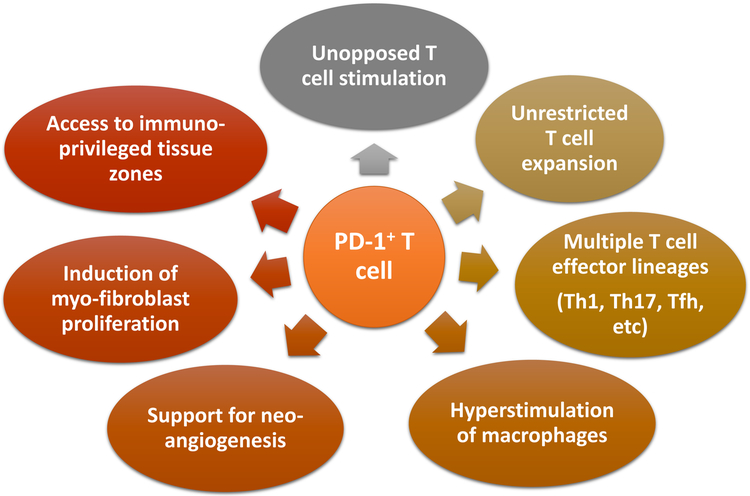

Removing the PD-1/PD-L1-dependent protection lead to a dense T cell infiltrate, with T cells from multiple different lineages represented [32] (Fig.3). Expression of lineage-determining transcription factors in the lesions indicated that Th1, Th17 and Tfh-committed T cells were entrapped in the vessel wall. Effector cytokine analysis demonstrated IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-21, a cytokine cocktail that is also typical for biopsy samples taken from GCA patients [33–36]. Thus, the vasculitogenic T cell infiltrate is composed of many different effector lines, enabling aggressive inflammatory activity and a multitude of damage pathways. Comparison of frequencies of CD4+PD-1+ T cells revealed effective enrichment of PD-1-expressing T cells in the inflamed vessel walls, after the PD-1 checkpoint was disabled.

Figure 3. Vasculitogenic T cells in Giant Cell Arteritis.

Tissue-invading T cells in GCA are unopposed due to the failure of PD-L1 expression on endothelial cells and on dendritic cells. Most lesional T cells are PD-1pos. Functional consequences of unrestricted T cell activation are multifold: (1) hyperactivation of T cells; (2) durable T cell expansion and survival; (3) hyperstimulation of macrophages; (4) unopposed access to privileged tissue zones; (5) support for myofibroblast growth; (6) enhanced angiogenesis of microvascular networks.

Probably the most surprising observations in the checkpoint-inhibited arteries was the acceleration of two disease processes, that so far have not been associated with T cell activity: inflammation-associated neoangiogenesis [37–39] and the outgrowth of myofibroblast forming hyperplastic intima [40–42] (Fig.3). Newly formed microvessels appear in the adventitia and the media of the inflamed arterial wall, where they supply oxygen and nutrients for the tissue-invading cells, but also expedite access of further inflammatory cell populations to the wall layers. The outgrowth of myofibroblasts to build the thickened intima is of critical disease importance, as most of the clinical manifestations are related to vessel stenosis/occlusion and tissue ischemia. This holds true specifically for the blindness-inducing ischemic optic neuropathy. Cellular origins and processes giving rise to the growing intima are not entirely clear, but proceed at rapid pace in GCA [43]. Arteries treated with the checkpoint inhibitor had markedly increased numbers of microvessels and the thickness of the intimal layer doubled. It is possible that removing negative signaling by PD-1 blockade translated into much more aggressive inflammation, equally intensifying downstream events. However, tissue cytokine production, an easy read-out of inflammatory activity has been reported to be inversely related to risk for ischemic events. Thus, direct actions of uninhibited T cells appear a more likely explanation. Together, these experiments directly implicated T cell function into wall remodeling and, for the first time, defined PD-1 and PD-L1 as molecules-of-interest in the sequalae of blood vessel inflammation. Communication of T cells with vascular stromal cells, e.g. microvascular vasa vasora or myofibroblasts fits well into the emerging disease concepts. A recent study has identified an instructive tissue niche that relies on the interaction between microvessels and T cells via Jagged1-Notch1 interaction [28]. Further work needs to quantify the contribution of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signals and their interrelationship in shaping vasculitogenic immunity.

3. PD-L1HI IMMUNOINHIBITORY MACROPHAGES IN CORORNARY ARTERY DISEASE (CAD)

In mice, impairment of the PD-1 pathways either by knockout of the PD-L1 ligand or the PD-1 receptor, results in atherogenesis by increasing lesion size, T cell density and higher macrophage recruitment [44, 45]. Even the expansion of anti-inflammatory T cells in checkpoint-deficient mice was not sufficient to prevent the exacerbation of atherogenesis in mice [46]. These data are in line with the concept that the chronic inflammatory response in athero-prone mice is sustained by co-stimulated T cell responses [47] and is kept in check by co-inhibitory signals.

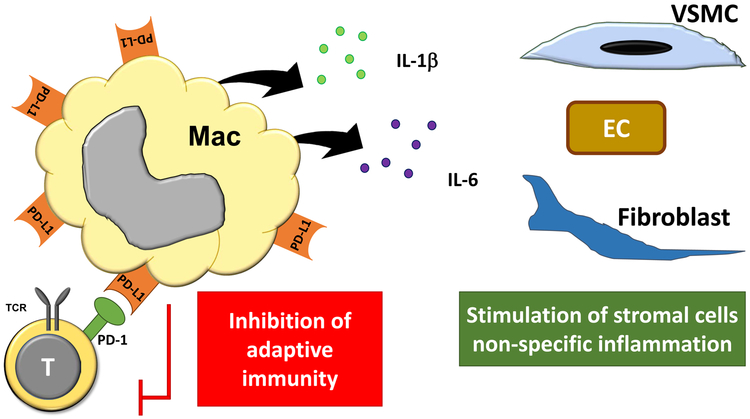

Human atherosclerosis appears to follow different rules, as recent data strongly support a very active PD-1 checkpoint in the atherosclerotic plaque [48] (Fig.4). Discrepancies between mice and human may partly reflect profound differences in the kinetics of disease (Table 1). CAD is a disease of slow progression [49] and mostly affects individuals over the age of 60 years. It remains the dominate cause of death in the Western world, by inducing acute tissue ischemia [50] (stroke and heart attack) or by step-wise weakening of myocardial muscle function (cardiac insufficiency). Atherosclerotic lesions in affected blood vessels are populated by macrophages, some of which differentiate into lipid-laden foam cells. T-cells have been placed into the plaque, where they produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ [51, 52] and T-cell co-stimulation has been suspected to magnify abnormal immune reactivity. Plaque-residing T cells are enriched for CD4+CD28- T cells [53], now recognized as a marker of the immune aging process. Such T cells have undergone extensive proliferation, are end-differentiated, are no longer dependent on CD28-mediated co-stimulation and have acquired several innate receptors, through which they communicate with stromal cells in the vessel wall, including EC.

Fig. 4: PD-L1hi IL-1βhi IL-6hi macrophages in coronary artery disease.

Macrophages populating the atherosclerotic plaque express high surface density of the immuno-inhibitory ligand PD-L1 and suppress the induction of T-cell responses. Also, they are prone to release IL-1β and IL-6, two pro-inflammatory cytokines that enhance innate immunity and non-specific tissue inflammation.

TCT; T cell receptor

Table 1: The PD-1 Immune Checkpoint in Vascular Inflammation.

Comparison of the role of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint in two inflammatory conditions of the vascular wall. In large vessel vasculitis, low expression of PD-L1 dismantles the checkpoint, leading to unrestrained T cell responses. In contrast, PD-L1 expression in high in the atherosclerotic plaque. Patients with coronary artery disease have impaired T cell responses to varicella zoster virus, which can partially corrected by blocking PD-L1.

| Large Vessel Vasculitis |

Atherosclerosis | |

|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 expression | low | high |

| PD-1 expression | high | (? high) |

| CD80/CD86 | high | high |

| T cell activation | enhanced | impaired |

| T cell expansion | enhanced | impaired |

| Anti-VZV T cells | impaired | |

| IL-1β/IL-6 | like age-matched controls | high |

| CD4 T cell immunosenescence | ?? | yes |

| CD8 Treg function | impaired | ?? |

The enrichment of CD4+CD28- T cells in the blood [54] and the tissue lesions [53] of CAD patients identifies such individuals as being immunosenescent, even beyond the degree of immune aging experienced by healthy age-matched individuals. Circulating CD8 T cells in patients with atherosclerosis similarly display an aging phenotype, expressing PD-1 and Tim-3 [55]. The process of immunosenescence is now recognized as a complex program, affecting multiple domains of cellular functions [56, 57]. Necessitated by the involution of T cell generation in the thymus, which happens early in life, and the continuous need for new T cells to battle old and new infections and malignancies, the human immune system has adopted several strategies to optimally maintain immune competence with advancing age. To generate new T cells, the system utilizes a process of self-renewal of already existing T cells, named homeostatic proliferation. To secure immune defenses against infections and tumors, the system differentiates memory T cells and expands the memory compartment over life time (memory expansion). To mitigate the risk of excessive immunity, T cells acquire multiple inhibitory receptors [58, 59], which attempt to control clonal outgrowth, but also limit immune competence. The acquisition of co-inhibitory molecules, such as PD-1, by aging T cells can lead to immune exhaustion [60–62]. Immune exhaustion occurs in chronic viral infection and in tumor-bearing hosts and malignancies usurp this mechanism to successfully escape for immune recognition and destruction.

Most macrophages in the atherosclerotic plaque are PD-L1 positive [48], enabling them to provide inhibitory signals to interacting T cells (Fig.4). Macrophages differentiated from blood precursor cells of CAD patients are high expressors for PD-L1 and the intensity of PD-L1 surface expression on CAD macrophages distinguishes them from similar cells derived from age-matched healthy individuals. The density of the co-stimulatory ligands CD80 and CD86 is similar in macrophages from CAD patients and healthy controls, compatible with a selective abnormality impacting negative signaling.

PD-L1 overexpression in CAD macrophages has functional consequences. Patient-derived PD-L1hi macrophages suppress the activation and clonal expansion of CD4 T cells. Importantly, they inhibit the induction of IFN-γ producing T cells specific for varicella zoster virus (VZV) [48]. VZV is a herpesvirus which causes chickenpox during childhood [63, 64]. The virus enters latency and is reactivated when anti-VZV CD4 T cells wane over life time [65, 66]. When anti-VZV CD4 T cells are no longer present in sufficient numbers and at sufficient effectiveness, the virus is reactivated and becomes visible in infected skin lesions, called the shingles. This is a frequent event in the elderly; by the time people turn 80 years old, up to 30% of them have experienced VZV reactivation, manifesting clinically as herpes zoster and complicated by postherpetic pain [67, 68]. When stimulated with VZV lysate, one million peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals contained 250 IFN-γ-secreting T cells, whereas CAD patients had less than 100 of such protective T cells [48]. Addition of anti-PD-L1 antibodies improved the induction of patient-derived anti-VZV T cells by almost 50%, implicating PD-L1 in inhibiting anti-viral immunity. In line with these findings, the risk of CAD patients to develop herpes zoster attacks is significantly increased compared to age-matched populations [69] and, vice versa, within 2 years of having a herpes zoster attack, the risk for cardiovascular events is significantly elevated [70].

PD-L1 overexpression is not the only abnormality in CAD macrophages; intense upregulation of the inhibitory ligand is coupled to other functional deviations; specifically, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [71] (Fig.4). CAD macrophages respond to activation with high production of IL-1β and IL-6. The production of IL-6 is correlated with systemic inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and is sustained in plaque-residing macrophages. The abnormality is already present in circulating CD14+ monocytes, suggesting that patient-derived hematopoietic cells are exposed to stimulatory signals in the bone marrow environment.

In essence, immune checkpoints shape T cell immunity in CAD patients. High expression of PD-L1 boosts the PD-1 checkpoint and effectively impairs protective T-cell responses. In the tissue environment of the inflamed atherosclerotic plaque, PD-L1hi macrophages co-produce IL-1β and IL-6, thus dampening adaptive immunity and amplifying non-specific immune reactivity. A possible interpretation is that in the chronic lesion of the human atherosclerotic plaque, T cells fulfill tissue-protective functions, which are controlled by PD-1-derived signals. Molecular definition of such functions may allow therapeutic manipulation and re-establishment of tissue tolerance in atherosclerosis.

4. METABOLIC CONTROL OF PD-L1 EXPRESSION

While the PD-L1hi IL-1βhi IL-6hi signature of plaque macrophages allows a more integrated view of how these innate cells shape in situ conditions in the damaged wall, the question remains how this functional status is induced. In recent studies, two pathways have been identified to lead to induction of IL-6/IL-1β and PD-L1, respectively [48, 71] (Fig.5). Both pathways are mechanistically connected to cellular metabolism, opening the intriguing possibility to modulate immune function through metabolic interference [72].

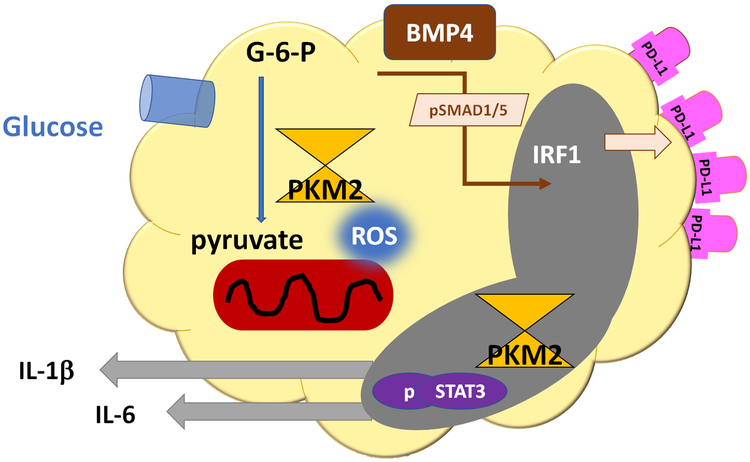

Figure 5. Metabolic control of macrophage function.

Glucose metabolism and mitochondrial activity regulate macrophage function through two major pathways: (1) Excess glucose uptake increases pyruvate and heats up the mitochondrial electron transport chain; resulting in ROS production. Mitochondrial ROS force PKM2 into dimeric formation and PKM2 dimers are translocated into the nucleus, where they phosphorylate STAT3. This triggers production of IL-1β and IL-6. (2) Pyruvate import into the mitochondrion induces production of BMP4, which activates SMAD1/5 phosphorylation and upregulation of the transcription factor IRF1. IRF1 amplifies transcription of PD-L1, enabling the cell to deliver immunoinhibitory signals.

IL-1βhi IL-6hi macrophages from CAD patients have a molecular signature of strongly upregulated glycolysis [71]. Compared to macrophages generated from healthy donors, patient-derived cells express significantly higher transcript concentrations for the glucose transporters GLUT3 and GLUT1 and the glycolytic enzymes PKM2, PDK1, PFKFB3, HK2, and PGK1. Functional assessment of glycolytic activity and mitochondrial activity by Seahorse analysis confirmed upregulation of oxygen-dependent and oxygen-independent energy production. Cytokine release could be suppressed by withdrawing glucose and by scavenging mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS). Molecular analysis connected the mitochondrial overload with excess ROS production. Once released from the mitochondria, ROS promoted the dimerization of the glycolytic enzyme PKM2. Dimeric PKM2 was spotted in the nucleus, where it acted as a protein kinase and phosphorylated the transcription factor STAT3. pSTAT3 directly increased transcripts for IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig.5). Nuclear activities of PKM2, specifically in regulating cytokine production, is considered a “moonlighting function”, implicating basic metabolic regulators in directly affecting cellular behavior [73–76].

Mitochondria are now recognized as key regulators of cytokine production [77, 78], employing several pathways of upregulating cytokine transcripts and cell surface receptors. Dimerization and nuclear translocation of PKM2 could not be implicated in upregulating PD-L1, giving rise to the concept that the excess production of cytokines and the enhancement of PD-L1 expression may be separable. Molecular studies demonstrated that the transcription factor inducing PD-L1 in CAD macrophages was IRF1 [48], with STAT1 and STAT3 making minor contributions. The PD-L1hi phenotype was, however, linked to the release of bone morphogenetic protein 4, which in turn triggered SMAD1/5 phosphorylation and induction of IRF1 (Fig.5).

The common root between excessive cytokine production (IL-1β, IL-6) and the upregulation of immunoinhibitory surface molecules (PD-L1) could be traced to oversupply of glucose and mitochondrial stress. The glucose breakdown product pyruvate alone was sufficient to switch macrophages into PD-L1hi expressors [48]. Import of pyruvate into the mitochondria was required to reach the PD-L1hi phenotype. Mitochondria were identified as the source of ROS driving PKM2 dimers into the nucleus, where this kinase supports pro-inflammatory functions.

These data predict that immunosuppressive functions of CAD macrophages may be triggered by excess glucose in their environment. Alternatively, a defect in glucose import could cause a similar scenario. How glucose transporters are being regulated in human macrophages and whether environmental cues impact this fundamental step in metabolism is insufficiently understood [79]. Abnormalities identified in CAD macrophages so far have in common that the cells take up glucose in excess amounts and enter the molecule into the glycolytic pathway, overloading the mitochondria. Negative feedback loops protecting mitochondria from nutrient oversupply appear dysfunctional [80, 81]. Interlinking the metabolic abnormalities and the pro-inflammatory abnormalities of CAD patients on a molecular level promises to be informative.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Inflammation of the blood vessel wall occurs most frequently as a smoldering fibroreparative process that results in formation of the atherosclerotic plaque, wall remodeling and luminal compromise. In some individuals, the process is complicated by sudden tissue breakdown leading to acute ischemia. Antigen recognition has been implicated in intra-plaque immune responses [82], predicting that the rules of adaptive immune regulation apply. In murine atherosclerosis, loss of inhibitory immune checkpoints exacerbates disease. In human atherosclerosis, the lesion does not lack immunoinhibitory signal, but rather has a surplus of PD-L1 (Fig.4). The T cell compartment of patients with CAD is known to be prematurely aged [83, 84], with the selection of large CD4 T cell clonotypes that are end-differentiated. An important aspect of T cell aging is the upregulation of inhibitory receptors [85, 86], and CAD T cells have been reported to possess an array of receptors borrowed from NK cells and have undergone a change in T cell receptor threshold setting [87][88][89]. Aged T cells can interact with stromal cells, promote endothelial damage [90], vascular smooth muscle cell death and tissue inflammation [91, 92]. This holds true for T cells in patients that have developed severe and complicated CAD. Overall, in the inflamed atherosclerotic plaque, the tolerance-inducing PD-1 checkpoint is highly upregulated, yet tissue damage is insufficiently controlled. PD-L1 expression was evident even in early atherosclerotic lesions [48], making it unlikely that the abundance of PD-L1 simply reflects chronicity. Better understanding of PD-1-dependent T cells responses in the tissue lesion is needed to understand this signature.

The PD-1 checkpoint is obviously functional in CAD. Protective anti-viral immune responses are downregulated and are partially recovered by blocking PD-L1. One possible model is that the “wound” in the atherosclerotic plaque does not heal because anti-viral immunity is inefficient. PD-1 expression is a hallmark of T cells in chronic viral infection [93].

The participation of the PD-1 checkpoint in the acute inflammatory condition of GCA is diametrical different (Table 1, Fig. 2; Fig.4). Here, PD-L1 is typically low on circulating monocytes, dendritic cells and on tissue-resident dendritic cells (Fig. 2). The low expression of PD-L1 transcripts in tissue extracts of inflamed arteries lead to the discovery of immune checkpoint failure in GCA [48], indicating that all PD-L1-expressing cell types are affected. Like in CAD, the abnormal expression of PD-L1 has a systemic and tissue component. Like in CAD, indirect, but no direct evidence for disease-inducing antigens has been provided and it is currently unclear which combination of signals drives the vessel wall lesion. In contrast to CAD patients, GCA patients have no signs of immune aging in their CD4 T cell compartment; quite surprisingly, given that age is the major disease risk factor for this vasculitic syndrome. CD4 T cells in GCA are chronically stimulated, but do not progress to end-differentiation nor the accumulation of expanded clonotypes. Notably, the failure of the PD-1 checkpoint is not the only abnormality in the immune system of GCA patients that fosters unrestrained T cell responses. GCA patients lack a population of anti-inflammatory CD8 T cells [94] that can control the responsiveness of CD4 T cells. These CD8 Treg cells are localized in the T-cell zones of secondary lymphoid organs and mediate their immunoinhibitory function by impacting the systemic CD4 T cell pool. The molecular mechanism of CD8 Treg-mediated suppression of CD4 T cells has been clarified: they produce membrane vesicles that contain the enzyme NOX2 and transfer such exosomes onto neighboring CD4 T cells. The end result is proximal interference with the TCR activation cascade in CD4 T cells. Through this mechanism, CD8 Treg cells can control the overall size of the CD4 compartment. Numbers and functionality of NOX2+ CD8 Tregs declines with age [94, 95], but their absence in GCA patients is selective and is not a feature in other inflammatory conditions.

Revolutionary progress in cancer immunotherapy has made available therapeutic reagents that enable to modify the PD-1 checkpoint in vivo [96–98]. In cancer patients, anti-PD1 or nati-PD-L1 therapy unleashes the immune system, generating powerful anti-tumor T cell responses, sometimes complicated by drug-induced autoimmunity. In CAD patients, blocking the PD-1 checkpoint could improve anti-viral T cell responses. Understanding the impact on the atherosclerotic plaque requires further studies. Conversely, in GCA, strengthening of the PD-1 checkpoint, e.g. through agonistic antibodies, could restore immunoinhibitory signaling and rebuild the natural immune privilege of the vessel wall. Given the impact of metabolic intermediates on PD-L1 expression, interfering with metabolic activity of T cells [99] and macrophages emerges as an novel approach of immunomodulatory therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Work reviewed here was supported by the NIH (R01 AR042527, R01 HL117913, R01 AI108906 and P01 HL129941 to CMW and R01 AI108891, R01 AG045779, U19 AI057266, R01 AI129191and I01 BX001669 to JJG), the Govenar and Cahill Discovery Funds. We thank our patients who have given samples for research studies and our clinical colleagues who have contributed their patients. We apologize to all colleagues whose work could not be included.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GCA

giant cell arteritis

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- VZV

varicella zoster vaccine

- BMP4

bone morphogenetic protein 4

- IRF1

interferon regulatory factor 1

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- vasDC

vascular dendritic cells

- PKM2

M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase

- GLUT3

glucose transporter 3

- PDK1

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1

- PFKFB3

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3

- HK2

hexokinase 2

- PGK1

phosphoglycerate kinase 1

- PFK-1

phosphofructokinase-1

- GLUT1

glucose transporter 1

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- NOX

NADPH oxidase / oxide of nitrogen

- NAPDH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase M2

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

No conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Legein B, Temmerman L, Biessen EA, Lutgens E (2013) Inflammation and immune system interactions in atherosclerosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 70, 3847–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gistera A and Hansson GK (2017) The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 13, 368–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zernecke A (2015) Dendritic cells in atherosclerosis: evidence in mice and humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35, 763–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lintermans LL, Stegeman CA, Heeringa P, Abdulahad WH (2014) T cells in vascular inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 5, 504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yahagi K, Kolodgie FD, Lutter C, Mori H, Romero ME, Finn AV, Virmani R (2017) Pathology of Human Coronary and Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis and Vascular Calcification in Diabetes Mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 37, 191–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirai T, Hilhorst M, Harrison DG, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2015) Macrophages in vascular inflammation--From atherosclerosis to vasculitis. Autoimmunity 48, 139–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weyand CM and Goronzy JJ (2003) Medium- and large-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med 349, 160–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyand CM and Goronzy JJ (2014) Clinical practice. Giant-cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. N Engl J Med 371, 50–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyand CM, Liao YJ, Goronzy JJ (2012) The immunopathology of giant cell arteritis: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. J Neuroophthalmol 32, 259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L and Flies DB (2013) Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 227–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q and Vignali DA (2016) Co-stimulatory and Co-inhibitory Pathways in Autoimmunity. Immunity 44, 1034–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acuto O and Michel F (2003) CD28-mediated co-stimulation: a quantitative support for TCR signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 3, 939–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fife BT and Bluestone JA (2008) Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunol Rev 224, 166–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okazaki T and Honjo T (2007) PD-1 and PD-1 ligands: from discovery to clinical application. Int Immunol 19, 813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibson PJ (2004) The regulation of lymphocyte activation by inhibitory receptors. Curr Opin Immunol 16, 328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siska PJ and Rathmell JC (2015) T cell metabolic fitness in antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol 36, 257–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamoto K, Chowdhury PS, Kumar A, Sonomura K, Matsuda F, Fagarasan S, Honjo T (2017) Mitochondrial activation chemicals synergize with surface receptor PD-1 blockade for T cell-dependent antitumor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E761–E770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bengsch B, Johnson AL, Kurachi M, Odorizzi PM, Pauken KE, Attanasio J, Stelekati E, McLane LM, Paley MA, Delgoffe GM, Wherry EJ (2016) Bioenergetic Insufficiencies Due to Metabolic Alterations Regulated by the Inhibitory Receptor PD-1 Are an Early Driver of CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion. Immunity 45, 358–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Wu Y, Chernova T, Sobel RA, Klemm M, Kuchroo VK, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH (2004) PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 10691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keir ME, Liang SC, Guleria I, Latchman YE, Qipo A, Albacker LA, Koulmanda M, Freeman GJ, Sayegh MH, Sharpe AH (2006) Tissue expression of PD-L1 mediates peripheral T cell tolerance. J Exp Med 203, 883–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC, Horton HF, Fouser L, Carter L, Ling V, Bowman MR, Carreno BM, Collins M, Wood CR, Honjo T (2000) Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med 192, 1027–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe R, Zhang H, Berry G, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2017) Immune checkpoint dysfunction in large and medium vessel vasculitis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312, H1052–H1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weyand CM and Goronzy JJ (2013) Immune mechanisms in medium and large-vessel vasculitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 9, 731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maleszewski JJ, Younge BR, Fritzlen JT, Hunder GG, Goronzy JJ, Warrington KJ, Weyand CM (2017) Clinical and pathological evolution of giant cell arteritis: a prospective study of follow-up temporal artery biopsies in 40 treated patients. Mod Pathol 30, 788–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weyand CM, Wagner AD, Bjornsson J, Goronzy JJ (1996) Correlation of the topographical arrangement and the functional pattern of tissue-infiltrating macrophages in giant cell arteritis. J Clin Invest 98, 1642–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilhorst M, Shirai T, Berry G, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2014) T cell-macrophage interactions and granuloma formation in vasculitis. Front Immunol 5, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pryshchep O, Ma-Krupa W, Younge BR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2008) Vessel-specific Toll-like receptor profiles in human medium and large arteries. Circulation 118, 1276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen Z, Shahram Y, Li Y, Watanabe R, Liao YJ, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2017) The microvascular niche instructs T-cells in large vessel vasculitis via the VEGF Jagged1-Notch pathway. Sci Transl Med 9, eaal 3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Watanabe R, Berry GJ, Vaglio A, Liao YJ, Warrington KJ, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2017) Immunoinhibitory checkpoint deficiency in medium and large vessel vasculitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E970–E979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma-Krupa W, Jeon MS, Spoerl S, Tedder TF, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2004) Activation of arterial wall dendritic cells and breakdown of self-tolerance in giant cell arteritis. J Exp Med 199, 173–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piggott K, Deng J, Warrington K, Younge B, Kubo JT, Desai M, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2011) Blocking the NOTCH pathway inhibits vascular inflammation in large-vessel vasculitis. Circulation 123, 309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe R, Hosgur E, Zhang H, Wen Z, Berry G, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2017) Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory T cells in giant cell arteritis. Joint Bone Spine 84, 421–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng J, Younge BR, Olshen RA, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2010) Th17 and Th1 T-cell responses in giant cell arteritis. Circulation 121, 906–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciccia F, Rizzo A, Guggino G, Cavazza A, Alessandro R, Maugeri R, Cannizzaro A, Boiardi L, Iacopino DG, Salvarani C, Triolo G (2015) Difference in the expression of IL-9 and IL-17 correlates with different histological pattern of vascular wall injury in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 54, 1596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samson M, Audia S, Fraszczak J, Trad M, Ornetti P, Lakomy D, Ciudad M, Leguy V, Berthier S, Vinit J, Manckoundia P, Maillefert JF, Besancenot JF, Aho-Glele S, Olsson NO, Lorcerie B, Guillevin L, Mouthon L, Saas P, Bateman A, Martin L, Janikashvili N, Larmonier N, Bonnotte B (2012) Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes expressing CD161 are implicated in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum 64, 3788–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terrier B, Geri G, Chaara W, Allenbach Y, Rosenzwajg M, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Fouret P, Musset L, Benveniste O, Six A, Klatzmann D, Saadoun D, Cacoub P (2012) Interleukin-21 modulates Th1 and Th17 responses in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 64, 2001–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser M, Younge B, Bjornsson J, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (1999) Formation of new vasa vasorum in vasculitis. Production of angiogenic cytokines by multinucleated giant cells. Am J Pathol 155, 765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neill L, Rooney P, Molloy D, Connolly M, McCormick J, McCarthy G, Veale DJ, Murphy CC, Fearon U, Molloy E (2015) Regulation of Inflammation and Angiogenesis in Giant Cell Arteritis by Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A. Arthritis Rheumatol 67, 2447–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelimarkka L, Salminen H, Kuopio T, Nikkari S, Ekfors T, Laine J, Pelliniemi L, Jarvelainen H (2001) Decorin is produced by capillary endothelial cells in inflammation-associated angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 158, 345–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser M, Weyand CM, Bjornsson J, Goronzy JJ (1998) Platelet-derived growth factor, intimal hyperplasia, and ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 41, 623–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makkuni D, Bharadwaj A, Wolfe K, Payne S, Hutchings A, Dasgupta B (2008) Is intimal hyperplasia a marker of neuro-ophthalmic complications of giant cell arteritis? Rheumatology (Oxford) 47, 488–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ly KH, Regent A, Molina E, Saada S, Sindou P, Le-Jeunne C, Brezin A, Witko-Sarsat V, Labrousse F, Robert PY, Bertin P, Bourges JL, Fauchais AL, Vidal E, Mouthon L, Jauberteau MO (2014) Neurotrophins are expressed in giant cell arteritis lesions and may contribute to vascular remodeling. Arthritis Res Ther 16, 487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muratore F, Boiardi L, Cavazza A, Aldigeri R, Pipitone N, Restuccia G, Bellafiore S, Cimino L, Salvarani C (2016) Correlations between histopathological findings and clinical manifestations in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis. J Autoimmun 69, 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu DX, Tarrio M, Maganto-Garcia E, Stavrakis G, Tajima G, Lederer J, Jarolim P, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH (2011) Impairment of the programmed cell death-1 pathway increases atherosclerotic lesion development and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31, 1100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gotsman I, Grabie N, Dacosta R, Sukhova G, Sharpe A, Lichtman AH (2007) Proatherogenic immune responses are regulated by the PD-1/PD-L pathway in mice. J Clin Invest 117, 2974–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cochain C, Chaudhari SM, Koch M, Wiendl H, Eckstein HH, Zernecke A (2014) Programmed cell death-1 deficiency exacerbates T cell activation and atherogenesis despite expansion of regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis-prone mice. PLoS One 9, e93280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buono C and Lichtman AH (2004) Co-stimulation and plaque-antigen-specific T-cell responses in atherosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14, 166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe R, Shirai T, Namkoong H, Zhang H, Berry GJ, Wallis BB, Schaefgen B, Harrison DG, Tremmel JA, Giacomini JC, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2017) Pyruvate controls the checkpoint inhibitor PD-L1 and suppresses T cell immunity. J Clin Invest 127, 2725–2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yahagi K, Davis HR, Arbustini E, Virmani R (2015) Sex differences in coronary artery disease: pathological observations. Atherosclerosis 239, 260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanwar SS, Stone GW, Singh M, Virmani R, Olin J, Akasaka T, Narula J (2016) Acute coronary syndromes without coronary plaque rupture. Nat Rev Cardiol 13, 257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liuzzo G, Vallejo AN, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Holmes DR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2001) Molecular fingerprint of interferon-gamma signaling in unstable angina. Circulation 103, 1509–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flego D, Liuzzo G, Weyand CM, Crea F (2016) Adaptive Immunity Dysregulation in Acute Coronary Syndromes: From Cellular and Molecular Basis to Clinical Implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 68, 2107–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, Kopecky SL, Holmes DR, Frye RL, Weyand CM (2000) Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 101, 2883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liuzzo G, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, O’Fallon WM, Maseri A, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (1999) Perturbation of the T-cell repertoire in patients with unstable angina. Circulation 100, 2135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu MK, Wang SC, Dai YX, Wang SQ, Ou JM, Quan ZW (2015) PD-1 and Tim-3 Pathways Regulate CD8+ T Cells Function in Atherosclerosis. PLoS One 10, e0128523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goronzy JJ and Weyand CM (2017) Successful and Maladaptive T Cell Aging. Immunity 46, 364–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pereira BI and Akbar AN (2016) Convergence of Innate and Adaptive Immunity during Human Aging. Front Immunol 7, 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henson SM, Macaulay R, Riddell NE, Nunn CJ, Akbar AN (2015) Blockade of PD-1 or p38 MAP kinase signaling enhances senescent human CD8(+) T-cell proliferation by distinct pathways. Eur J Immunol 45, 1441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cavanagh MM, Qi Q, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ (2011) Finding Balance: T cell Regulatory Receptor Expression during Aging. Aging Dis 2, 398–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Penaloza-MacMaster P, Kamphorst AO, Wieland A, Araki K, Iyer SS, West EE, O’Mara L, Yang S, Konieczny BT, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Rudensky AY, Ahmed R (2014) Interplay between regulatory T cells and PD-1 in modulating T cell exhaustion and viral control during chronic LCMV infection. J Exp Med 211, 1905–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jin HT, Anderson AC, Tan WG, West EE, Ha SJ, Araki K, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Ahmed R (2010) Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 14733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Zhu B, Allison JP, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ahmed R (2006) Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 439, 682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duncan CJ and Hambleton S (2015) Varicella zoster virus immunity: A primer. J Infect 71 Suppl 1, S47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helmuth IG, Poulsen A, Suppli CH, Molbak K (2015) Varicella in Europe-A review of the epidemiology and experience with vaccination. Vaccine 33, 2406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arvin A and Abendroth A (2007) VZV: immunobiology and host response In Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis (Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, and Yamanishi K, eds), Cambridge. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weinberg A and Levin MJ (2010) VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 342, 341–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmader K (2016) Herpes Zoster. Clin Geriatr Med 32, 539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, Cohrs RJ, Gershon MD, Gilden D, Grose C, Hambleton S, Kennedy PG, Oxman MN, Seward JF, Yamanishi K (2015) Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 1, 15016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ke CC, Lai HC, Lin CH, Hung CJ, Chen DY, Sheu WH, Lui PW (2016) Increased Risk of Herpes Zoster in Diabetic Patients Comorbid with Coronary Artery Disease and Microvascular Disorders: A Population-Based Study in Taiwan. PLoS One 11, e0146750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu PY, Lin CL, Sung FC, Chou TC, Lee YT (2014) Increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients with herpes zoster: a population-based study. J Med Virol 86, 772–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shirai T, Nazarewicz RR, Wallis BB, Yanes RE, Watanabe R, Hilhorst M, Tian L, Harrison DG, Giacomini JC, Assimes TL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2016) The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Exp Med 213, 337–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weyand CM, Zeisbrich M, Goronzy JJ (2017) Metabolic signatures of T-cells and macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Immunol 46, 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palsson-McDermott EM, Curtis AM, Goel G, Lauterbach MA, Sheedy FJ, Gleeson LE, van den Bosch MW, Quinn SR, Domingo-Fernandez R, Johnston DG, Jiang JK, Israelsen WJ, Keane J, Thomas C, Clish C, Vander Heiden M, Xavier RJ, O’Neill LA (2015) Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1alpha activity and IL-1beta induction and is a critical determinant of the warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab 21, 65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xie M, Yu Y, Kang R, Zhu S, Yang L, Zeng L, Sun X, Yang M, Billiar TR, Wang H, Cao L, Jiang J, Tang D (2016) PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 7, 13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bhardwaj A and Das S (2016) SIRT6 deacetylates PKM2 to suppress its nuclear localization and oncogenic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E538–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, Lyssiotis CA, Aldape K, Cantley LC, Lu Z (2012) ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat Cell Biol 14, 1295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monlun M, Hyernard C, Blanco P, Lartigue L, Faustin B (2017) Mitochondria as Molecular Platforms Integrating Multiple Innate Immune Signalings. J Mol Biol 429, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tschopp J (2011) Mitochondria: Sovereign of inflammation? Eur J Immunol 41, 1196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Calder PC, Dimitriadis G, Newsholme P (2007) Glucose metabolism in lymphoid and inflammatory cells and tissues. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10, 531–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith CO, Nehrke K, Brookes PS (2017) The Slo(w) path to identifying the mitochondrial channels responsible for ischemic protection. Biochem J 474, 2067–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dikic I (2017) Proteasomal and Autophagic Degradation Systems. Annu Rev Biochem 86, 193–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ketelhuth DF and Hansson GK (2016) Adaptive Response of T and B Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 118, 668–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaplan RC, Sinclair E, Landay AL, Lurain N, Sharrett AR, Gange SJ, Xue X, Parrinello CM, Hunt P, Deeks SG, Hodis HN (2011) T cell activation predicts carotid artery stiffness among HIV-infected women. Atherosclerosis 217, 207–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weyand CM, Fulbright JW, Goronzy JJ (2003) Immunosenescence, autoimmunity, and rheumatoid arthritis. Exp Gerontol 38, 833–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gustafson CE, Qi Q, Hutter-Saunders J, Gupta S, Jadhav R, Newell E, Maecker H, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ (2017) Immune Checkpoint Function of CD85j in CD8 T Cell Differentiation and Aging. Front Immunol 8, 692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Akbar AN and Henson SM (2011) Are senescence and exhaustion intertwined or unrelated processes that compromise immunity? Nat Rev Immunol 11, 289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pryshchep S, Goronzy JJ, Parashar S, Weyand CM (2010) Insufficient deactivation of the protein tyrosine kinase lck amplifies T-cell responsiveness in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Res 106, 769–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang X, Niessner A, Nakajima T, Ma-Krupa W, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2006) Interleukin 12 induces T-cell recruitment into the atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res 98, 524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakajima T, Goek O, Zhang X, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2003) De novo expression of killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and signaling proteins regulates the cytotoxic function of CD4 T cells in acute coronary syndromes. Circ Res 93, 106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakajima T, Schulte S, Warrington KJ, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2002) T-cell-mediated lysis of endothelial cells in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 105, 570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pryshchep S, Sato K, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2006) T cell recognition and killing of vascular smooth muscle cells in acute coronary syndrome. Circ Res 98, 1168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sato K, Niessner A, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2006) TRAIL-expressing T cells induce apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells in the atherosclerotic plaque. J Exp Med 203, 239–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Duttagupta PA, Boesteanu AC, Katsikis PD (2009) Costimulation signals for memory CD8+ T cells during viral infections. Crit Rev Immunol 29, 469–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wen Z, Shimojima Y, Shirai T, Li Y, Ju J, Yang Z, Tian L, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2016) NADPH oxidase deficiency underlies dysfunction of aged CD8+ Tregs. J Clin Invest 126, 1953–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Suzuki M, Jagger AL, Konya C, Shimojima Y, Pryshchep S, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM (2012) CD8+CD45RA+CCR7+FOXP3+ T cells with immunosuppressive properties: a novel subset of inducible human regulatory T cells. J Immunol 189, 2118–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R (2013) Programmed cell death 1-directed immunotherapy for enhancing T-cell function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 78, 239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM (2012) Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 24, 207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Callahan MK and Wolchok JD (2013) At the bedside: CTLA-4- and PD-1-blocking antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol 94, 41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weyand CM and Goronzy JJ (2017) Immunometabolism in early and late stages of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 13, 291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]