Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the effects of radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) and clinical and electrophysiological characteristics in symptomatic patients with premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) from near the His‐bundle (His‐PVCs).

Methods

The patient characteristics, prevalence of complications with any life style related disease (ALSRD) including hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes mellitus, and/or cardiovascular disease (CVD) including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, renal dysfunction, or cardiomyopathy, clinical status, frequency of PVCs evaluated by 24hour Holter monitoring, echocardiography including the left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) parameters, and electrophysiological findings were evaluated in 14 consecutive symptomatic patients with His‐PVCs.

Results

The prevalence of males, being elderly and/or slightly obese, current and/or history of smoking, ALSRD or CVD related complications, and LVDD probably resulting from ALSRD and/or CVD complications were higher in patients with His‐PVCs. RFCA of His‐PVCs steadily decreased the PVC frequency and improved the systolic function, LV dilation, and clinical status, but not the LVDD. There was a significant relationship between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and His‐PVCs and the distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle.

Conclusion

The analysis of the QRS duration and accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and His‐PVCs before the RFCA may help to determine the distance between the origin of the PVCs and His‐bundle. Further, the appropriate ablation catheter may be selected during the RFCA procedure. Finally, RFCA may be one of the most effective, feasible, and safest therapies for symptomatic patients with His‐PVCs.

Keywords: catheter ablation, clinical characteristics, clinical status, His‐bundle, premature ventricular contraction

1. INTRODUCTION

Isolated premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are the most common arrhythmias observed in patients even if without structural heart disease.1 Many patients with PVCs often experience disabling symptoms and sometimes need long–term antiarrhythmic medications. However, the latter may have adverse effects, such as the increasing the mortality, probably due to their proarrhythmic effects, even though markedly suppressing the occurrence of PVCs.2 In recent years, radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) has proven to be a safe and successful therapy for arrhythmias including PVCs.3 Moreover, we previously reported that RFCA of PVCs from the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT‐PVCs), which is one of the most common type of PVCs, improves left ventricular (LV) dilation and the clinical status in patients without structural heart disease.1 On the other hand, PVCs from near the His‐bundle are comparably uncommon.3 However, they also often occur with intolerable symptoms. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of RFCA and the clinical and electrophysiological characteristics in symptomatic patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study population and laboratory analysis

This study was approved by the institutional review committee and ethics review board of our hospitals. From 2014 to 2017, 15 consecutive intolerable symptomatic patients with drug (including beta‐blockers, calcium–channel blockers, and class I agents of the Vaughan Williams classification) refractory PVCs from near the His‐bundle visited our hospitals. Fourteen out of the 15 patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle underwent RFCA. All patients had their history recorded, and underwent a physical examination, laboratory analysis, 12‐lead electrocardiography (12‐ECG), 24 hour Holter monitoring, and echocardiography, on admission or within at least 1 month before admission, and 6 months after the successful RFCA. The LV end–diastolic (LVDd) or systolic (LVDs) internal dimension, and right ventricle (RV) internal dimension (RVD), LV ejection fraction (LVEF) measured using the Teichholz method, parameters of LV diastolic dysfunction including the mitral early to late diastolic flow velocity ratio (E/A ratio), mitral E wave deceleration time (DcT), mean lateral e’ velocity (e’) and index E/e’ ratio using tissue Doppler imaging, tricuspid regurgitation velocity (TRV), and left atrial volume index (LAVI), were measured. All the echocardiography values were recorded during sinus rhythm, but not during PVC beats, nor post‐PVC beats. The serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) concentration and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class using a specific activity scale were evaluated on admission and 6 months after the successful RFCA.

2.2. Classification of PVCs from near the His‐bundle (Figure 1A,B)

Figure 1.

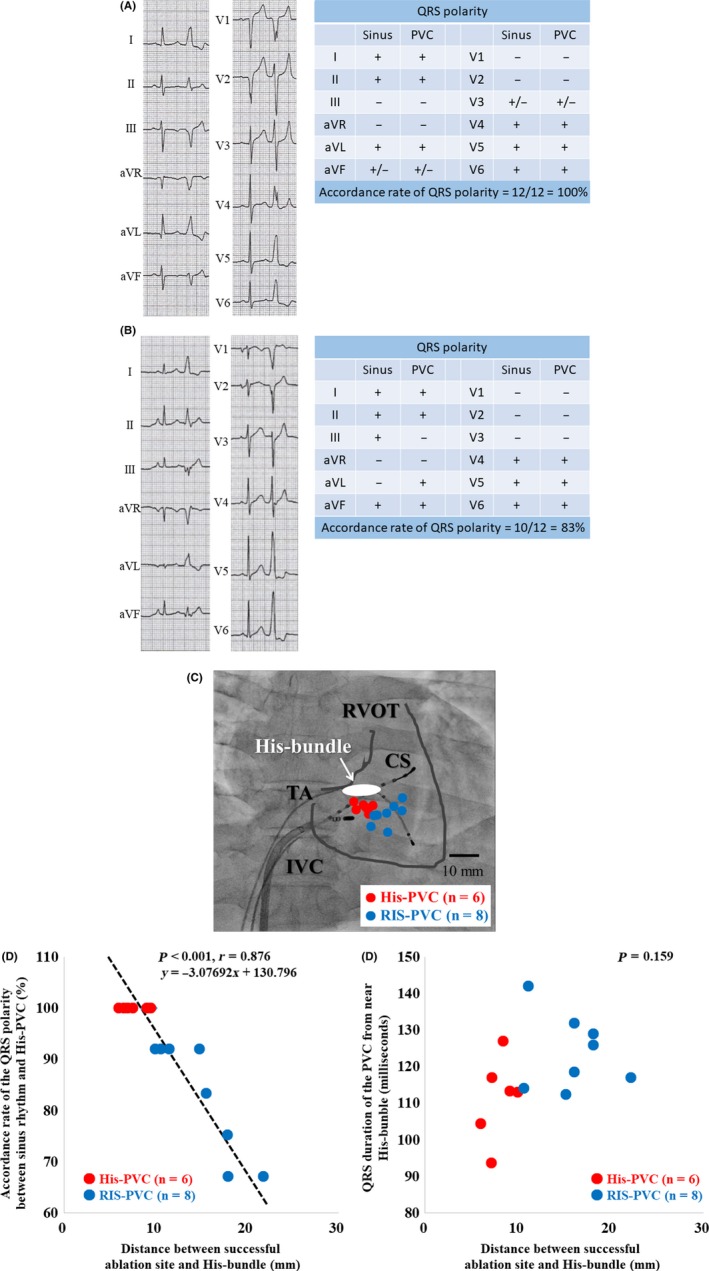

The 12‐lead electrocardiograms and the QRS polarities in patients of His‐PVC (A) and RIS‐PVC (B) groups, respectively. The accordance rate of QRS polarities was 100% (A) and 83% (B), respectively. The successful ablation sites of the premature ventricular contractions from near the His‐bundle are demonstrated in (C). The bars indicate 10 millimeters. The scatter plot analysis shows a significant strong relationship between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and His‐PVCs and the distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (P < 0.001, r = 0.876) (D), but not between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and the QRS duration of the His‐PVCs and QRS duration of the His‐PVCs (P = 0.159) (E). The red and blue circles indicate the His‐PVC group (n = 6) and RIS‐PVC group (n = 8), respectively. CS; coronary sinus, IVC; inferior vena cava, RVOT; right ventricular outflow tract, TA; tricuspid annulus

The PVCs from near the His‐bundle were divided into two groups on the basis of the site of the PVC origin. The His–PVC group was defined as having a site of the origin of the PVCs located near the His‐bundle within at least 10 mm of the largest His‐bundle potential4 (Figure 1A). The PVC from the right interventricular septum (RIS) (RIS–PVC) group was defined as having a site of the origin of the PVCs located near the His‐bundle, within 25 mm, but without the largest His‐bundle potential (Figure 1B). Ventricular tachycardia (VT) was defined by the standard electrocardiographic criteria of at least three consecutive PVCs at a rate of >120 beats per minute. No patients had any VT or atrial tachyarrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia, or paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, or received hemodialysis during this study.

2.3. Mapping and catheter ablation procedure

All procedures were performed after written informed consent was obtained. Antiarrhythmic drugs were discontinued at least 3 days before the procedure. The QRS duration and peak deflection index (PDI)5 were measured before the RFCA. RFCA was performed as described previously.1 In brief, under local anesthesia, after an 80 unit per kilogram administration of heparin was administered, 4 or 5‐mm‐tip electrode catheters (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) were introduced percutaneously into the RV and coronary sinus, respectively. After right ventriculography, in order to detect the earliest activation site, electro–anatomical mapping during the PVCs was performed in detail utilizing a 3D mapping system (EnSite NavX/Velocity™ Cardiac Mapping System, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) and a deflectable quadripolar ablation catheter (Therapy T3™ or FlexAbility™, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA). If the culprit PVC was not found during the procedure, an isoproterenol administration and/or programmed electrical stimulation with a digital stimulator (Cardiac Stimulator, Nihon Kohden Co., Tokyo, Japan) was performed to induce the culprit PVC. An optimal pace map was defined as a match of all 12 surface leads by comparing the R/S ratio and subtle notching in the QRS complex during pacing. An identical match was necessary in at least 11 of 12 leads. Further, based on the findings of the electro–anatomical mapping and an optimal pace map, radiofrequency energy was delivered at the site of the unipolar potentials from the ablation catheter demonstrating a QS pattern and bipolar potentials from the tip of the ablation catheter preceding the QRS in the 12‐ECG by at least 20 milliseconds during the PVC with a preset temperature of 43 to 50°C and power limit of 25 W. Further, a step–wise incremental application of the radiofrequency energy was performed with 10, 15, 20, and 25W,6 while increasing the energy of each of those steps in 15 second intervals over 60 seconds. The radiofrequency energy application was terminated when a prolongation of the atrio–ventricular (AV) interval, AV block, abnormal impedance rise (>30 Ω), or excessive junctional ectopic beats of >5 beats were observed. The distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle was also measured by the EnSite system. A successful ablation was defined as no recurrence and non‐inducibility of the culprit PVC with and without an isoproterenol administration and/or programmed electrical stimulation for at least 30 min after the ablation. Procedural success was defined as no recurrence of the culprit PVC within 24 h after the procedure under electrocardiogram monitoring. If the recurrence of the culprit PVC was observed, a repeat RFCA was performed.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The numerical results are expressed in the text as the mean ± standard deviation. Paired data was compared using Fisher's exact test and Student t tests.

A comparison of time–related changes was performed by using Mann‐Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test for post hoc analysis. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Clinical characteristics of the patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle on admission (Table 1)

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle on admission

| All | His–PVC | RIS–PVC | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 14 | 6 | 8 | |

| Male | 11 (79%) | 5 (83%) | 6 (75%) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 69 ± 2 | 71 ± 2 | 68 ± 4 | 0.138 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 0.9 | 23.4 ± 1.2 | 24.6 ± 1.3 | 0.138 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.92 ± 0.07 | 0.538 |

| Current and/or history of smoking | 9 (64%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (75%) | 0.580 |

| Any life style related disease | 12 (86%) | 5 (83%) | 7 (88%) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 9 (64%) | 4 (67%) | 5 (63%) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia | 8 (57%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (63%) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (21%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (13%) | 0.538 |

| Complication with CVD | 7 (50%) | 3 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 1.000 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3 (21%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (13%) | 0.538 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (21%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (25%) | 1.000 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (13%) | 1.000 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Palpitations | 10 (71%) | 4 (67%) | 6 (75%) | 1.000 |

| General fatigue | 5 (36%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (25%) | 0.580 |

| Chest discomfort/pain | 7 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 5 (63%) | 0.592 |

| Fainting | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

| Medications | ||||

| Beta blockers | 9 (64%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (75%) | 0.580 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2 (14%) | 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0.165 |

| Class I agents | 3 (21%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (25%) | 1.000 |

| No medication | 2 (14%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (13%) | 1.000 |

PVC, premature ventricular contraction; NA, not applicable; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Fourteen out of 15 patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle underwent RFCA. In 14 patients (11 males and three females with a mean age of 69 ± 2 years, body mass index (BMI) of 24.1 ± 0.9 kg/m2, and serum creatinine of 0.92 ± 0.05 mg/dl), the prevalence of the co‐existence of ex‐ or current smoking, any life style related disease (ALSRD) including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus (DM), and complications from cardiovascular disease (CVD) including coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease (CBVD), or cardiomyopathy, were nine (64%), twelve (86%), nine (64%), eight (57%), three (21%), seven (50%), three (21%), three (21%), and one (7%), patients, respectively. The prevalence of symptoms including palpitations, general fatigue, chest discomfort, and fainting, were ten (71%), five (36%), seven (50%), and zero (0%), respectively. On admission, all patients had PVC–associated intolerable symptoms. Of 14 patients, 12 (86%) were taking antiarrhythmic agents before admission, such as beta‐blockers (9; 64%), calcium channel blockers (2; 14%), and class Ia, Ib, and/or Ic Vaughan Williams classification agents (3; 21%). However, those agents were not sufficiently effective in eliminating the PVC–associated symptoms. All of the patients with a successful procedure reported the absence of PVC–associated symptoms and could discontinue the antiarrhythmic agents after the RFCA. The antihypertensive, antihypercholesterolemic, and antidiabetic agents and/or others were continued in patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, DM, CAD, CBVD, and cardiomyopathy before and after the RFCA.

3.2. Comparison of the clinical characteristics between the His–PVC group and RIS–PVC group on admission (Table 1)

There were no statistical differences among all factors including the age (71 ± 2 vs 68 ± 4; P = 0.138), BMI (23.4 ± 1.2 vs 24.6 ± 1.3 kg/m2; P = 0.138), serum creatinine (0.91 ± 0.05 vs 0.92 ± 0.07; P = 0.538), prevalence of being male (83% vs 75%; P = 1.000), co‐existence of ex‐ or current smoking (50% vs 75%; P = 0.580), ALSRD (83% vs 88%; P = 1.000) including hypertension (67% vs 63%; P = 1.000), dyslipidemia (30% vs 63%; P = 1.000), and DM (33% vs 13%; P = 0.538), prevalence of symptoms including palpitations (67% vs 75%; P = 1.000), general fatigue (50% vs 25%; P = 0.580), chest discomfort (33% vs 63%; P = 0.592), and fainting (0% vs 0%), and medications including beta‐blockers (50% vs 75%; P = 0.580), calcium channel blockers (33% vs 0%; P = 0.165), class I agents (17% vs 25%;P = 1.000) and no medication (17% vs 13%; P = 1.000), between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC group.

3.3. Twenty four hour Holter monitoring, NYHA functional class, and serum BNP concentration, in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle before and after the RFCA (Table 2)

Table 2.

24 hour Holter monitoring, NYHA functional class, and serum BNP concentration, in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle before and after RFCA

| All (n = 14) | His–PVC (n = 6) | RIS–PVC (n = 8) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hour Holter Monitoring | ||||

| Before RFCA Total heart beats (beats/day) | 106 694 ± 3176 | 110 446 ± 2693 | 103 881 ± 5125 | 0.358 |

| Total PVC (beats/day) | 17 999 ± 3306 | 19 787 ± 4684 | 16 658 ± 4814 | 0.685 |

| %PVC (%) | 17 ± 3 | 18 ± 3 | 16 ± 4 | 0.822 |

| After RFCA Total heart beats (beats/day) | 104 849 ± 2671 | 105 756 ± 3102 | 104 169 ± 4228 | 0.822 |

| Total PVC (beats/day) | 108 ± 35* | 106 ± 62* | 109 ± 43* | 1.000 |

| %PVC (%) | 0.10 ± 0.03* | 0.10 ± 0.05* | 0.10 ± 0.04* | 1.000 |

| Functional status | ||||

| Before RFCA NYHA functional class | 1.86 ± 0.14 | 1.67 ± 0.21 | 2.00 ± 0.19 | 0.138 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 63 ± 14 | 55 ± 15 | 68 ± 23 | 0.583 |

| After RFCA NYHA functional class | 1.00 ± 0.00* | 1.00 ± 0.00* | 1.00 ± 0.00* | 1.000 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 18 ± 3* | 16 ± 6* | 18 ± 2* | 0.785 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation.

P < 0.05 vs Before RFCA.

The %PVCs was calculated as: 100*[number of PVCs/number of total heart beats per day]. There was no statistical difference in the number of total heart beats (106 694 ± 3176 vs 104 849 ± 2671 beats/day; P = 0.358) between that before and after the RFCA. RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle steadily and significantly decreased and improved the total PVC per day count (from 17 999 ± 3306 to 108 ± 35 beats/day; P < 0.001), %PVCs (from 17 ± 3 to 0.10 ± 0.03%; P < 0.01), NYHA functional class (from 1.86 ± 0.14 to 1.00 ± 0.00; P < 0.001), and serum BNP concentration (from 63 ± 14 to 18 ± 3 pg/mL; P = 0.004) as compared to that before the RFCA.

3.4. Comparison of the 24 hour Holter monitoring, NYHA functional class, and serum BNP concentration, between the His–PVC group and RIS–PVC group before and after the RFCA (Table 2)

Before the RFCA, there was no statistical difference in the number of total heart beats (110 446 ± 2693 vs 103 881 ± 5125 beats/day; P = 0.358), total PVCs per day (19 787 ± 4684 vs 16 658 ± 4814 beats/day; P = 0.685), %PVCs (18 ± 3 vs 16 ± 4%; P = 0.822), NYHA functional class (1.67 ± 0.21 vs 2.00 ± 0.19; P = 0.138), and serum BNP concentration (55 ± 15 vs 68 ± 23 pg/mL; P = 0.785), between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups. RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle could steadily and significantly decrease and improve the total PVC per day count (from 19 787 ± 4684 to 106 ± 62 beats/day; P = 0.002 and from 16 658 ± 4814 to 109 ± 43 beats/day; P = 0.004), %PVCs (from 18 ± 3 to 0.01 ± 0.05%; P < 0.001 and from 16 ± 4 to 0.01 ± 0.04%; P = 0.003), NYHA functional class (from 1.67 ± 0.21 to 1.00 ± 0.00; P = 0.010 and from 2.00 ± 0.19 to 1.00 ± 0.00; P < 0.001), and serum BNP concentration (from 55 ± 15 to 16 ± 6 pg/mL; P = 0.058 and from 68 ± 23 to 18 ± 2 pg/mL; P = 0.038) in the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups, respectively, as compared to that before the RFCA. After the RFCA, there was no statistical difference in the number of total heart beats (105 756 ± 3102 vs 104 169 ± 4228 beats/day; P = 0.822), total PVCs per day (106 ± 62 vs 109 ± 43 beats/day; P = 1.000), %PVCs (0.10 ± 0.05 vs 0.10 ± 0.04%; P = 1.000), NYHA functional class (1.00 ± 0.00 vs 1.00 ± 0.00; P = 1.000), and serum BNP concentration (16 ± 6 vs 18 ± 2 pg/mL; P = 0.785) between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups.

3.5. Echocardiography and diastolic dysfunction in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle before and after the RFCA (Table 3)

Table 3.

Echocardiogram Findings in Patients with PVCs from Near the His‐bundle before and after RFCA

| All (n = 14) | His–PVC (n = 6) | RIS–PVC (n = 8) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiogram | ||||

| Before RFCA LVEF (%) | 64 ± 1 | 64 ± 2 | 64 ± 2 | 1.000 |

| LVDd (mm) | 47 ± 1 | 47 ± 2 | 47 ± 2 | 1.000 |

| LVDs (mm) | 30 ± 1 | 31 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 0.583 |

| RVD (mm) | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 1.000 |

| After RFCA LVEF (%) | 67 ± 1* | 68 ± 1 | 67 ± 1 | 1.000 |

| LVDd (mm) | 44 ± 1* | 45 ± 1 | 43 ± 1 | 0.583 |

| LVDs (mm) | 28 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 0.592 |

| RVD (mm) | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 1.000 |

| Parameters of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction | ||||

| Before RFCA E/A ratio | 1.09 ± 0.10 | 0.91 ± 0.13 | 1.23 ± 0.14 | 0.138 |

| DcT (ms) | 239 ± 9 | 253 ± 6 | 228 ± 15 | 0.538 |

| Index E/e’ ratio | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 0.625 |

| Mean lateral e’ velocity (cm/s) | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 1.000 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.000 |

| Left atrial volume index (mL/m2) | 28 ± 3 | 24 ± 5 | 30 ± 5 | 0.592 |

| After RFCA E/A ratio | 1.12 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.13 | 1.22 ± 0.14 | 0.165 |

| DcT (ms) | 231 ± 9 | 248 ± 7 | 219 ± 13 | 0.138 |

| Index E/e’ ratio | 13 ± 1 | 12 ± 2 | 14 ± 1 | 0.593 |

| Mean lateral e’ velocity (cm/s) | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 0.925 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.138 |

| Left atrial volume index (mL/m2) | 27 ± 3 | 25 ± 5 | 30 ± 4 | 0.500 |

PVC, premature ventricular contraction; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVDd, left ventricular end–diastolic internal dimension; LVDs, left ventricular end–systolic internal dimension; RVD, right ventricular internal dimension; E/A ratio, mitral early to late diastolic flow velocity ratio; DcT, mitral E wave deceleration time.

P < 0.05 vs Before RFCA.

RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle could steadily and significantly improve the LVEF (from 64 ± 1 to 67 ± 1%; P = 0.022) and LVDd (from 47 ± 1 to 44 ± 1 mm; P = 0.045) as compared to that before the RFCA. Hovever, there was no statistical difference in the LVDs (30 ± 1 vs 28 ± 1 mm; P = 0.335) and RVD (15 ± 1 vs 15 ± 1 mm; P = 1.000) between that before and after the RFCA. Moreover, RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle could not improve the LV diastolic dysfunction including the parameters of the E/A ratio (from 1.09 ± 0.10 to 1.12 ± 0.10; P = 1.000), DcT (from 239 ± 9 to 231 ± 9 ms; P = 0.558), Index E/e’ (from 13 ± 1 to 13 ± 1; P = 1.000), mean lateral e’ velocity (from 5.9 ± 0.4 to 5.9 ± 0.3 cm/s; P = 1.000), TRV (from 2.3 ± 0.1 to 2.3 ± 0.1 m/s; P = 1.000), and LAVI (from 28 ± 3 to 27 ± 3 mL/m2; P = 0.940), between that before and after the RFCA.

3.6. Comparison of the echocardiography and diastolic dysfunction between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups before and after the RFCA (Table 3)

There was no statistical difference in the LVEF (from 64 ± 2 to 68 ± 1%; P = 0.094 and from 64 ± 2 to 67 ± 1%; P = 0.124), LVDd (from 47 ± 2 to 45 ± 1 mm; P = 0.284 and from 47 ± 2 to 43 ± 1 mm; P = 0.112), LVDs (from 31 ± 1 to 28 ± 1 mm; P = 0.229 and from 29 ± 1 to 27 ± 1 mm; P = 0.293), RVD (from 15 ± 1 to 15 ± 1 mm; P = 1.000 and from 15 ± 1 to 15 ± 1 mm; P = 1.000), LV diastolic dysfunction including the parameters of the E/A ratio (from 0.91 ± 0.13 to 0.98 ± 0.13; P = 0.685 and from 1.23 ± 0.14 to 1.22 ± 0.14; P = 1.000), DcT (from 253 ± 6 to 248 ± 7 ms; P = 0.594 and from 228 ± 15 to 219 ± 13 ms; P = 0.642), Index E/e’ (from 13 ± 2 to 12 ± 2; P = 1.000 and from 14 ± 2 to 14 ± 1; P = 1.000), mean lateral e’ velocity (from 5.8 ± 0.5 to 6.0 ± 0.4 cm/s; P = 0.757 and from 5.9 ± 0.6 to 5.9 ± 0.5 cm/s; P = 1.000), TRV (from 2.3 ± 0.1 to 2.4 ± 0.1 m/s; P = 0.352 and from 2.3 ± 0.1 to 2.3 ± 0.1 m/s; P = 1.000), and LAVI (from 24 ± 5 to 25 ± 5 mL/m2; P = 1.000 and from 30 ± 5 to 30 ± 4 mL/m2; P = 1.000), between that before and after the RFCA in both the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups, respectively. There was no statistical difference in the LVEF (64 ± 2 vs 64 ± 2%; P = 1.000 and 68 ± 1 vs 67 ± 1%; P = 1.000), LVDd (47 ± 2 vs 47 ± 2 mm; P = 1.000 and 45 ± 1 vs 43 ± 1 mm; P = 0.583), LVDs (31 ± 1 vs 29 ± 1 mm; P = 0.583 and 28 ± 1 vs 27 ± 1 mm; P = 0.592), RVD (15 ± 1 vs 15 ± 1 mm; P = 1.000 and 15 ± 1 vs 15 ± 1 mm; P = 1.000), LV diastolic dysfunction including the parameters of the E/A ratio (0.91 ± 0.13 vs 1.23 ± 0.14; P = 0.138 and 0.98 ± 0.13 vs 1.22 ± 0.14; P = 0.165), DcT (253 ± 6 vs 228 ± 15 ms; P = 0.538 and 248 ± 7 vs 219 ± 13 ms; P = 0.138), Index E/e’ (13 ± 2 vs 14 ± 2; P = 0.625 and 12 ± 2 vs 14 ± 1; P = 0.593), mean lateral e’ velocity (5.8 ± 0.5 vs 5.9 ± 0.6 cm/s; P = 1.000 and 6.0 ± 0.4 vs 5.9 ± 0.5; P = 0.925), TRV (2.3 ± 0.1 vs 2.3 ± 0.1 m/s; P = 1.000 and 2.4 ± 0.1 vs 2.3 ± 0.1 m/s; P = 0.138), and LAVI (24 ± 5 vs 30 ± 5 mL/m2; P = 0.592 and 25 ± 5 vs 30 ± 4 mL/m2; P = 0.500), between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups before and after the RFCA, respectively.

3.7. Comparison of the electrophysiological findings between the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups (Table 4 and Figure 1C‐E)

Table 4.

Comparison of the electrophysiological findings, complications, and recurrence rate in the His–PVC group vs RIS–PVC group

| His–PVC (n = 6) | RIS–PVC (n = 8) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophysiological findings of PVCs | |||

| QRS duration (ms) | 111 ± 5 | 125 ± 3 | 0.026 |

| Peak deflection index | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 1.000 |

| Accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and PVCs (%) | 100 ± 0 | 84 ± 4 | 0.005 |

| Distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (mm) | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 15.9 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Ablation catheter during the successful session | |||

| 4 mm‐tip catheter | 5 (83%) | 3 (38%) | 0.138 |

| Irrigation catheter | 1 (17%) | 5 (63%) | 0.138 |

| Others | |||

| Complications | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

| Recurrence rate for the 1st session | 2 (33%) | 1 (13%) | 0.538 |

| Recurrence rate for the 2nd session | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

PVC, premature ventricular contraction; NA, not applicable.

During RFCA procedures, no patients required a radiofrequency energy delivery from the left ventricle or aortic cusps in either group. The QRS duration (111 ± 5 vs 125 ± 3 ms; P = 0.026), accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and PVCs, average distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (100 ± 0 vs 84 ± 4%; P = 0.005), and distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (8.0 ± 0.6 vs 15.9 ± 1.3 mm; P < 0.001), were significantly narrower, higher, and shorter, in the His–PVC group than RIS–PVC group. There was no statistical difference in the PDI between the two groups (0.57 ± 0.05 vs 0.59 ± 0.05; P = 1.000). The successful ablation sites in the His–PVC group (red circle; n = 6) and RIS–PVC group (blue circle; n = 8) are demonstrated in Figure 1C. The scatter plot analysis revealed a significant relationship between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and His–PVCs and the distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (P < 0.001, r = 0.876) (Figure 1D), but not between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and the QRS duration of the His–PVCs (P = 0.159) (Figure 1E). The prevalence of the use of irrigation catheters tended to be lower in the His–PVC group than RIS–PVC group (17% vs 63%; P = 0.138). Because radiofrequency energy had to be delivered near the His‐bundle in the His–PVC group, 4 mm‐tip catheters were used (83% vs 38%; P = 0.138) in order to avoid AV block. Although the initial success rates were 100% in both groups, recurrence of culprit PVCs was observed in two (33%) and one (13%) patients during the follow‐up in the His–PVC and RIS–PVC groups, respectively. However, all three patients underwent a repeat RCFA with successful results and no recurrence. Although only one patient suffered from transient AV block during the radiofrequency energy deliveries in the His–PVC group, no patients suffered from any procedure–related permanent adverse complications in either group.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Clinical characteristics in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle

We demonstrated that there was a higher prevalence of being male, elderly, slightly obese, and having a current and/or history of smoking, complications from ALSRD including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and DM, and CVDs including CAD, CBVD, and cardiomyopathy, LV diastolic dysfunction in patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle compared to RVOT‐ and other PVCs, as previously reported.1, 7 These findings may possibly indicate that the complications from ALSRD and/or CVD contributing to LV diastolic dysfunction may be induced and accelerated by a higher age and bad life style. Thus, the probable mechanisms of PVCs from near the His‐bundle may be associated with these conditions. In this study, although there were no patients with PVCs from the LV near His‐bundle, it is unfortunately unknown why they occurred in the RV near the His‐bundle. Moreover, the underlying intracellular mechanisms of the PVCs from near the His‐bundle could not be clarified.

4.2. Electrocardiogram characteristics of PVCs from near the His‐bundle

An RVOT‐PVC was defined as having a characteristic electrocardiographic appearance with (i) a left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern in precordial leads, (ii) tall R waves in the inferior leads, and (iii) an early precordial transitional zone in leads V3‐V4, as previously described.1 A PVC from near the His‐bundle was defined as having a characteristic electrocardiographic appearance with (i) a monophasic tall R pattern in lead I, (ii) low R waves in leads II, III, and aVF, particularly lower R waves in lead III than lead II, (iii) R waves in lead aVL, relatively narrow QRS duration, (iv) QS pattern in lead V1, (v) an early precordial transitional zone in leads V2‐V3, and (vi) tall R waves in leads V5 and V6, as previously described.3, 4 The PVCs from near His‐bundle were differentiated from RVOT‐PVCs by recognizing these electrocardiographic chatacteristics.

4.3. RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle

Because the PDI5 of the PVCs from near the His‐bundle (0.59 ± 0.03) is small, their origin is thought to be in the endocardium, indicating the effectiveness of RFCA. However, for origins of PVCs from near the His‐bundle, especially in the His–PVC group (8.0 ± 0.6 mm), that are located near the His‐bundle (Table 4, Figure 1C), RFCA may have a high risk of AV block.3 Thus, in order to perform a safe procedure and avoid AV block, we paid attention to the following five points: (i) Right ventriculography was performed before the RFCA to confirm the RV anatomy. (ii) An electro–anatomical map of the RV was reconstructed in detail with an EnSite NavX/Velocity™ 3D mapping system. (iii) Marking of the area where His‐bundle potentials were recorded was performed (Figure 1A). (iv) A step–wise incremental application of radiofrequency energy was performed with 10, 15, 20, and 25 W.6 (v The fluoroscopic images were prudently and continuously observed during RF energy delivery to avoid even a subtle dislodgement of the ablation catheter. (vi) The radiofrequency energy application was terminated when a prolongation of the AV interval, AV block, abnormal impedance rise (>30 Ω), or excessive junctional ectopic beats of >5 beats were observed. Finally, His–PVCs were successfully treated using RFCA without any complications and a good clinical course was obtained.

4.4. Selection of the ablation catheter for RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle

The QRS duration (111 ± 5 vs 125 ± 3 ms; P = 0.026), was significantly narrower in the His–PVC group than RIS–PVC group (Table 4). The scatter plot analysis revealed a significant relationship between the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and PVCs from near the His‐bundle and the distance between the successful ablation site and His‐bundle (P < 0.001, r = 0.876) (Figure 1D). Thus, those analyses before the RFCA may help to determine the distance between the origin of the PVCs and the His‐bundle. Further, an appropriate ablation catheter may be selected. For example, when the QRS duration was narrow, such as <120 ms, and/or the accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and the PVCs was higher, such as > 90%, the distance between the origin of the PVC and His‐bundle may be very near, such as <10 mm. Thus, if the origin of a PVC from near the His‐bundle was very near the His‐bundle, such as within <10 mm, or far from the His‐bundle, such as >10 mm, the appropriate ablation catheter used should possibly be a 4 mm‐tip or irrigated catheter because of their strong cauterizing power probably causing AV block. A previous study has demonstrated that the early recurrence rate of PVCs from near the His‐bundle was higher than that of RVOT‐PVCs.4 The reason for higher early recurrence rate might be related to an inadequate burn because of nonaggressive pursuance of RFCA for fear of creating AV block, and inadequate catheter contact because of difficulty of stable positioning of the ablation catheter near the His‐bundle.

4.5. Clinical benefits of RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle

Similar to what we previously reported about RFCA of RVOT‐PVCs,1 PVCs from near the His‐bundle steadily abolished the PVC–associated symptoms and improved the LVEF (so‐called LV systolic function), LV dilation, NYHA functional class, and serum BNP concentration (Tables 2 and 3). Unfortunately, RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐bundle could not improve the LV diastolic dysfunction parameters (Table 3). It is still unclear whether the cause of LV diastolic dysfunction may be PVCs from near the His‐bundle or myocardial degenerative changes resulting from complications from ALSRD and/or CVD. Because the serum BNP concentration improved 6 months after the RFCA of the PVCs from near the His‐bundle (Table 2), the LV diastolic dysfunction may improve after the long‐term follow‐up.

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Although our study was a multi–center trial, it was limited by a relatively small number of patients because PVCs from near the His‐Bundle are comparatively rare arrhythmias. The patients in this study were also limited by being symptomatic and an RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐Bundle being capable from only a right–sided approach. Thus, the effect of the RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐Bundle in asymptomatic patients was unfortunately unknown in this study. Moreover, our study could not clarify the underlying intracellular mechanisms of the PVCs from near the His‐Bundle or long‐term clinical benefit of RFCA of PVCs from near the His‐Bundle. Whether our results can safely be extrapolated to the inclusion of a larger number of patients and whether a longer follow–up period for these patients is needed should be determined in further studies. Recent advancement in new technologies, including the Arctic Front Advance cryo–ablation catheter, has facilitated a stable lesion creation near the His‐bundle and can be considered a safer source of energy as compared to RF energy in such patients at high risk of AV block.8 However, we could not use that device because it could be used in only a limited number of facilities in Japan at that time. However, they currently are commercially available all over the world and may improve and help in the RFCA procedure.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The clinical characteristics in patients with symptomatic PVCs from near the His‐bundle were a higher prevalence of being male, elderly, slightly obese, and having a current and/or history of smoking, complications from ALSRD including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and DM, and CVDs including CAD, CBVD, or cardiomyopathy, and LV diastolic dysfunction. RFCA of symptomatic PVCs from near the His‐bundle could improve the patients’ clinical status and LV systolic function, but not the LV diastolic dysfunction. The analysis of the QRS duration and accordance rate of the QRS polarity between sinus rhythm and PVCs from near the His‐bundle before the RFCA may help to determine the distance between the origin of the PVCs and His‐bundle. Further, an appropriate ablation catheter may be selected to avoid AV block during the RFCA procedure. Finally, RFCA may be one of the most effective, feasible, and safest therapies for symptomatic patients with PVCs from near the His‐bundle.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mrs. Kensuke Kawasaki, Shu Takata, Tsutomu Yoshinaga, Kazutaka Yamaguchi, and Takejiro Masumoto for their technical assistance with the electrophysiological study in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, and Mr. John Martin for his linguistic assistance with this paper.

Tanaka A, Takemoto M, Masumoto A, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular contractions from near the His‐bundle. J Arrhythmia. 2019;35:252–261. 10.1002/joa3.12167

REFERENCES

- 1. Takemoto M, Yoshimura H, Ohba Y, et al. Radiofrequency catheter ablation of premature ventricular complexes from right ventricular outflow tract improves left ventricular dilation and clinical status in patients without structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akhtar M, Breithardt G, Camm AJ, et al. Implications of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. Task Force of the Working Group on Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology. Circulation. 1990;81:1123–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lian‐Pin W, Yue‐Chun L, Jing‐Lin Z, et al. Catheter ablation of idiopathic premature ventricular contractions and ventricular tachycardias originating from right ventricular septum. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamauchi Y, Aonuma K, Takahashi A, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics of repetitive monomorphic right ventricular tachycardia originating near the His‐bundle. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1041–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hachiya H, Hirao K, Sasaki T, et al. Novel ECG predictor of difficult cases of outflow tract ventricular tachycardia: peak deflection index on an inferior lead. Circ J. 2010;74:256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haissaguerre M, Marcus F, Poquet F, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics and catheter ablation of parahissian accessory pathways. Circulation. 1994;90:1124–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka Y, Tada H, Ito S, et al. Gender and age differences in candidates for radiofrequency catheter ablation of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. Circ J. 2011;75:1585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Biase L, Al‐Ahamad A, Santangeli P, et al. Safety and outcomes of cryoablation for ventricular tachyarrhythmias: results from a multicenter experience. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]