Abstract

The roles of histone demethylation in the regulation of plant flowering, disease resistance, rhythmical response, and seed germination have been elucidated recently; however, how histone demethylation affects leaf senescence remains largely unclear. In this study, we exploited yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) to screen for the upstream regulators of NONYELLOWING1 (NYE1), and identified RELATIVE OF EARLY FLOWERING6 (REF6), a histone H3 lysine 27 tri-methylation (H3K27me3) demethylase, as a putative binding protein of NYE1 promoter. By in vivo and in vitro analyses, we demonstrated that REF6 directly binds to the motif CTCGYTY in NYE1/2 promoters through its zinc finger domain and positively regulates their expression. Loss-of-function of REF6 delayed chlorophyll (Chl) degradation, whereas overexpression of REF6 accelerated Chl degradation. Subsequently, we revealed that REF6 positively regulates the general senescence process by directly up-regulating ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 (EIN2), ORESARA1 (ORE1), NAC-LIKE, ACTIVATED BY AP3/PI (NAP), PYRUVATE ORTHOPHOSPHATE DIKINASE (PPDK), PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT 4 (PAD4), LIPOXYGENASE 1 (LOX1), NAC DOMAIN CONTAINING PROTEIN 3 (AtNAC3), and NAC TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR-LIKE 9 (NTL9), the key regulatory and functional genes predominantly involved in the regulation of developmental leaf senescence. Importantly, loss-of-function of REF6 increased H3K27me3 levels at all the target Senescence associated genes (SAGs). We therefore conclusively demonstrate that H3K27me3 methylation represents an epigenetic mechanism prohibiting the premature transcriptional activation of key developmentally up-regulated senescence regulatory as well as functional genes in Arabidopsis.

Author summary

Leaves of higher plants start yellowing and subsequently die (senescence) at particular developmental stages as a result of both internal and external regulations. Leaf senescence is evolved to facilitate nutrient remobilization to young/important organs to meet their rapid development, and a large number of genes (Senescence associated genes, SAGs) are activated to regulate/facilitate the process. It has been intriguing how these genes are kept transcriptionally inactive to ensure an effective photosynthesis before the initiation of leaf senescence. Here, we reveal an epigenetic mechanism responsible for the prohibition of their premature transcription. We found that an H3K27me3 demethylase, RELATIVE OF EARLY FLOWERING 6 (REF6), directly promotes the expression of its ten target senescence regulatory and functional genes (EIN2, ORE1, NAP, AtNAC3, NTL9, NYE1/2, LOX1, PAD4, and PPDK), which are involved in major phytohormones’ signaling, biosynthesis, and chlorophyll degradation. Crucially, REF6 is substantially involved in promoting the H3K27me3 demethylation of both their promoter and/or coding regions during the aging process of leaves. We therefore provide conclusive evidence that H3K27me3 methylation is an epigenetic mechanism hindering the premature transcriptional activation of key SAGs, which helps to explain the “aging effect” of senescence initiation.

Introduction

Histone methylation plays an essential role in diverse biological processes, ranging from transcriptional regulation to heterochromatin formation. Histone lysine methyltransferases (“writers”) and demethylases (“eraser”) dynamically regulate methylation levels, and in Arabidopsis, methylations at Lys4 (K4), Lys9 (K9), Lys27 (K27), and Lys36 (K36) of histone H3 have been extensively studied [1]. In general, histone H3K9 and H3K27 methylation are associated with silenced regions, whereas H3K4 and H3K36 methylation with active genes [2]. H3K9me1/2 and H3K27me1 are enriched at constitutively silenced heterochromatin in Arabidopsis [3, 4]. H3K27me3 repression of gene expression during development is a conserved mechanism in eukaryotes, and several thousand genes (more than 15% of all transcribed genes) in Arabidopsis are marked by the modification [5–7]. H3K27me3 is catalyzed by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which consists of four parts: E(Z), Su(z)12, p55, and Esc. Sequence similarity and genetic analyses revealed that Arabidopsis EZH2 homologs, including curly leaf (CLF), swinger (SWN), and medea (MEA), are H3K27me3 methyltransferases [1, 5].

The Jumonji (JMJ) protein was first identified in mouse by a gene trap approach [8]. Then, JMJ domain-containing proteins were found to be able to remove histone methyl groups [9, 10]. Arabidopsis JMJ homologs, RELATIVE OF EARLY FLOWERING 6 (REF6), EARLY FLOWERING 6 (ELF6) and JMJ30, were demonstrated as H3K27me3 demethylases [11–13]. ELF6 was first reported as a repressor of flowering in the photoperiod pathway, and REF6, with the highest similarity to ELF6, as a flowering locus C (FLC) repressor [14]. Loss-of-function mutations in REF6 lead to the ectopic accumulation of H3K27me3 at hundreds of genes in seedlings, suggesting that REF6 is a coordinator of multiple developmental programs in plants [11]. BRI1-EMS-suppressor 1 (BES1) and Nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-YA) were reported to recruit REF6 to its target genes [15, 16]. Notably, a new targeting mechanism of REF6 was recently revealed, i.e. by directly binding the CTCTGYTY motif in its target genes [17, 18]. In senescing leaves, the reprogrammed distribution of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 accompanies a decondensation of chromocenter heterochromatin in the interphase nuclei [19]. A further report showed that the senescence-associated global changes at chromatin organization can be inhibited by overexpressing SUVH2, a gene encoding a methyltransferase [20]. The above reports reveal a close relationship between senescence and histone modification, but how histone modification precisely regulates leaf senescence remains unclear.

Plants senesce typically in the modular manner and leaves are the major modular organ. Leaf senescence is an integral part of plant development, triggering characteristic degenerative processes as an adaptive mechanism, such as chlorophyll (Chl) degradation and macromolecule breakdown, and particularly recycling of released nutrients to nascent tissues or storage organs [21–23]. De-greening, reflecting a net loss of Chl, is the most obvious symptom of leaf senescence, which is closely associated with the degradation of light-harvesting complexes (LHCs) [24, 25]. The biochemical pathway of de-greening has been largely elucidated by the identification of Chl catabolic genes (CCGs) or Chl catabolic enzymes (CCEs) in Arabidopsis as well as in rice [26]. During senescence, Chl b is converted to Chl a via the catalysis of Chl b reductase (encoded by NYC1/NOL) and 7-hydroxymethyl Chl a reductase (HCAR) [27–30]. NYEs/SGRs-catalyzed magnesium dechelation is the first step of Chl a degradation, generating pheophytin a [31], which is then sequentially degraded/modified to: 1) pheophorbide a by pheophytin pheophorbide hydrolase (PPH) [32, 33], 2) to red chlorophyll catabolites (RCC) by pheophorbide a oxygenase (PAO), 3) to primary fluorescent chlorophyll catabolites (pFCC) by red chlorophyll catabolite reductase (RCCR) [34], and 4) finally to hydroxy-pFCC by TIC55 inside the chloroplast [35]. The conversion from pheophorbide a to RCC leads to the loss of green color of Chl catabolites [34]. The identification of NYE1/SGR1, among other major CCEs, was an important event, not only because it is responsible for catalyzing the first step of Chl a degradation but more significantly because its mutation is responsible for Mendel’s green cotyledon trait [36–43].

A broad range of endogenous factors as well as environmental cues can modulate the initiation/progression of leaf senescence [22], and ethylene (ET) has been shown to be a key promoter [44–47]. EIN2 and EIN3 predominantly mediate its signaling via a sophisticated regulatory hierarchy [46, 48–51]. During leaf senescence, EIN3 directly activates the expression of ORE1/NAC2 and NAP, as well as CCGs, to accelerate leaf senescence [52]. EIN3 is also involved in a feed-forward regulation by directly suppressing the expression of miR164, which targets ORE1 at the post-transcriptional level [46, 49]. Moreover, ORE1 and NAP directly activate the expression of Senescence associated genes (SAGs) and CCGs to accelerate leaf Chl degradation and senescence in general [52–54].

It is important to note that ethylene can promote senescence only in the leaves that have reached a certain age, in which some age-related changes must have occurred [55, 56]. Yet, the identities of these changes have not been clearly defined, and particularly, the mechanism(s) by which the transcription of the genes encoding major senescence regulatory as well as functional SAGs/CCGs is prematurely repressed remains elusive. In this study, we employed the yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) system to screen for the putative transcriptional regulator of NYE1 and interestingly, identified REF6, a histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase, as a candidate. It was then confirmed that REF6 modulates Chl degradation by directly up-regulating the transcription of NYE1/2. Subsequently, we demonstrated that REF6 also regulates general leaf senescence, and identified other eight senescence regulatory and functional genes (EIN2, ORE1, NAP, PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, AtNAC3, and NTL9) as its direct targets. Finally, we showed that REF6 regulates the expression of its ten target SAGs by reducing their H3K27me3 levels. Our study identifies that H3K27me3 methylation represents a kind of epigenetic mechanisms prohibiting the premature activation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis.

Results

REF6 directly binds to both the promoters and coding regions of NYE1 and NYE2

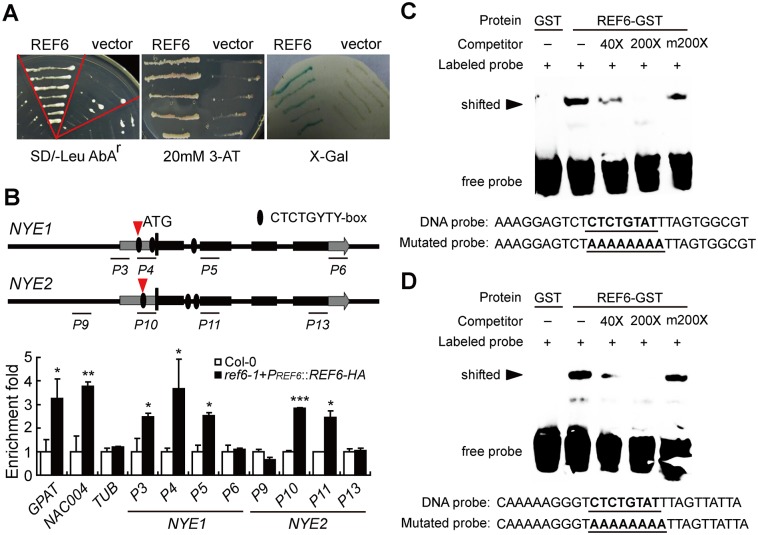

NYE1 was initially identified as a crucial regulator of Chl degradation during green organ senescence in diversified species and particularly shown to be responsible for the green/yellow cotyledon trait of Mendel’s pea (Pisum sativum) [36–43]. To understand the transcriptional regulation of NYE1, we exploited Y1H to screen for the putative trans-regulators of NYE1. The core part of NYE1’s promoter (-532 bp upstream of its ATG) was used as the bait for the screening against a cDNA library generated from the senescing leaves of Arabidopsis plants [57]. To our surprise, a positive clone encoding a zinc finger structure protein with two JMJ domains was identified, which was previously demonstrated to be a histone H3K27me3 demethylase and named as REF6 (AT3G48430) [11]. We then cloned the full-length coding region of REF6 into the vector pGAD-T7 and introduced the resultant construct along with PNYE1::Pabai into Y1H Gold. Y1H Gold grew well on a medium containing Aureobasidin A. To confirm this result, we generated a construct containing the reporter genes HIS3 and LacZ driven by the NYE1’s promoter and introduced it into the yeast YM4271 along with empty pGAD-T7 or REF6::pGAD-T7. Compared with the yeast transformed with empty pGAD-T7, the one with REF6::pGAD-T7 grew well in a 3-AT-containing medium and turned blue when transferred to X-Gal-containing medium (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. REF6 directly binds to both the promoters and coding regions of NYE1 and NYE2.

(A) Physical interactions of REF6 with NYE1 promoter in Y1H assays and blue-white spotting tests. (B) ChIP assays of in vivo association of REF6-HA with NYE1/2 genes in the 10-day-old seedlings of ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA and Col-0. Fold enrichments were calculated as the ratios of the signals in ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA to the signals in Col-0. Primers are listed in S4 Table. GPAT4 and NAC004 genes were used as positive controls, with TUB as a negative control. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test. (C, D) EMSAs of in vitro binding of REF6 to the CTCTGYTY motifs within the ChIP-PCR fragments P4 and P10 of NYE1 (C) and NYE2 (D) promoters (indicated with red arrows). Probe sequences used in EMSA are shown in (C) and (D). GST-tagged REF6 was incubated with the biotin-labeled wild-type DNA probe. Competition experiments were performed by adding the excessive amounts (40× and 200×, respectively) of unlabeled DNA probe. A mutated probe was used to test binding specificity. Shifted bands, indicating the formation of DNA-protein complexes, are indicated by arrows. “-” represents absence, “+” represents presence. Sequences of both the wild-type and mutated probes are shown on the bottom of the images.

Remarkably, REF6’s targeting mechanism was recently revealed, i.e. REF6 directly binds to the CTCTGYTY motif of its target genes [17]. By scanning NYE1’s promoter and coding regions, we found three CTCTGYTY motifs, and interestingly, we also detected three CTCTGYTY motifs across the promoter and coding regions of NYE2, a functional paralog of NYE1 [58]. To test whether REF6 protein could directly bind to these motifs in vivo, we carried out chromatin immuneprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assays with multiple pairs of primers designed accordingly. Chromatins isolated from ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA transgenic plants were immuneprecipitated with HA antibody, and RT-qPCR was then performed to quantify the enrichment of corresponding promoter and coding regions. We observed 2.6- to 3.7-fold enrichments in the NYE1’s promoter region (NYE1-P3, -P4), where the first two CTCTGYTY motifs are located, and relatively less enrichment in the first exon (NYE1-P5), which is close to the third CTCTGYTY motif, in contrast to no enrichment at the end of the coding region (NYE1-P6), where no CTCTGYTY motifs were detected. An expected enrichment pattern was also observed within NYE2’s promoter and coding regions (Fig 1B).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was carried out to determine whether REF6 protein could directly bind to NYE1/2 promoters in vitro. The C2H2-ZnF domain of REF6 fused with a GST tag (GST-REF6C 1,239–1,360 aa) was expressed and purified as described previously [17]; and a 28 bp DNA fragment covering the first CTCTGYTY motif in NYE1 promoter was made a probe. We detected a shifted band when labeled probes were pre-incubated with GST-REF6C, and addition of excess unlabeled probes competed with the binding. In contrast, REF6 protein did not bind to the motif-mutated probes (Fig 1C), indicating that REF6 specifically bound to the motif of NYE1 promoter in vitro. REF6 protein could also specifically bind to the motif of NYE2 promoter in vitro (Fig 1D). These observations, along with the previous data, collectively suggest that REF6 may act as a transcriptional regulator of NYE1/2 by directly binding to their CTCTGYTY motif-containing regions.

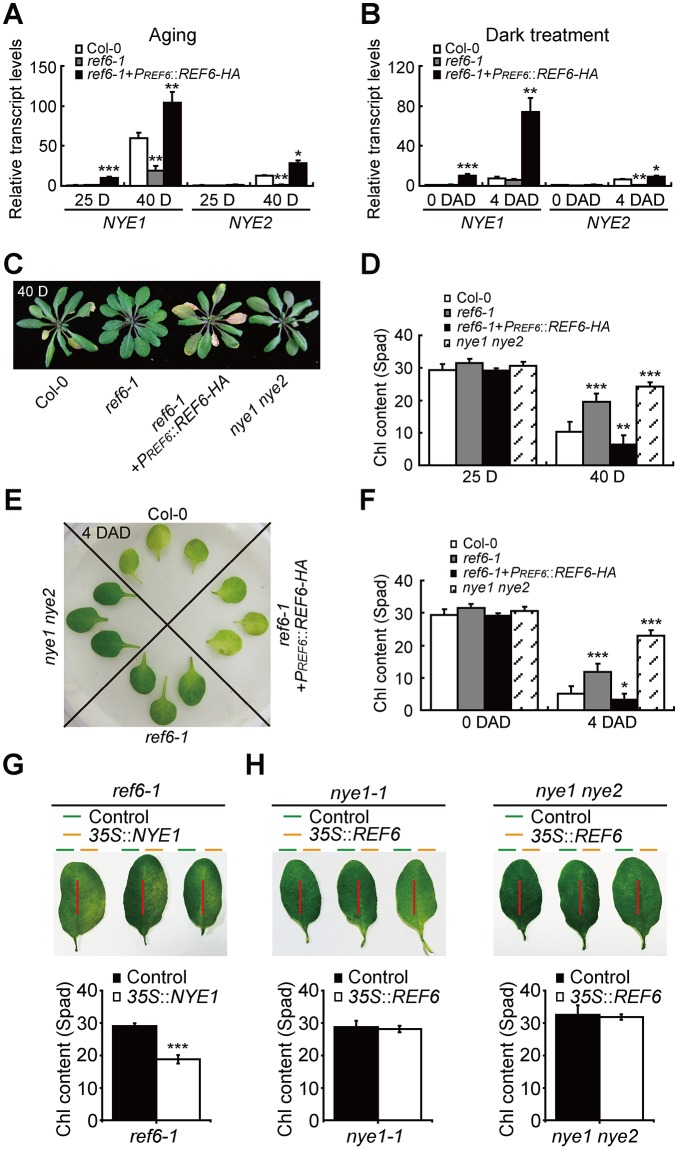

REF6 promotes Chl degradation during leaf senescence via up-regulation of NYE1 and NYE2

To verify the above assumption, we examined the characteristic changes of NYE1/2’s transcriptions in ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA, as well as in Col-0, during age-triggered and dark-induced leaf senescence. The ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA were the native promoter-driven REF6 overexpression plants with ~3.0-fold enhancement in its transcription (S1 Fig). Loss-of-function of REF6 significantly reduced the transcription of NYE1/2, whereas overexpression of REF6 enhanced the transcription of NYE1/2 during both of the scenarios of leaf senescence (Fig 2A and 2B).

Fig 2. REF6 promotes both Chl degradation and general leaf senescence process.

(A, B) Changes in the transcript levels of NYE1/2 in ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA relative to those in Col-0 with aging (A) and during dark treatment (B) (DAD, days after dark treatment). Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test. (C, D) Plants of indicated genotypes (ref6-1, ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA, nye1 nye2 as well as Col-0) grown under long day-growth conditions for 40 days (C). Chl contents (D) in the leaves of the plants shown in (C). (E, F) Phenotypes of indicated genotypes on 4 DAD. Detached leaves were obtained from 25-day-old plants under long day-growth conditions. Unless stated otherwise, the 3rd and 4th detached rosette leaves were used for physiological and molecular analyses. (G) Leaf phenotypes and Chl contents of ref6-1 after infiltration with Agrobacterium containing 35S::NYE1 or empty vector pCHF3. (H) Leaf phenotypes and Chl contents of nye1-1 or nye1 nye2 after infiltration with Agrobacterium containing 35S::REF6 or empty vector pCHF3.

To examine the role of REF6 in regulating Chl degradation, we first characterized the de-greening phenotype of ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA during age-triggered senescence, with nye1 nye2 and Col-0 plants used as controls. As expected, the rosette leaves of ref6-1 showed an obvious stay-green phenotype as compared with Col-0, whereas ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA exhibited a premature yellowing phenotype, in contrast to the most severe stay-green phenotype of nye1 nye2 (Fig 2C). Measurements of Chl content were consistent with the visual phenotype (Fig 2D). To confirm the regulatory role of REF6 in Chl degradation, their 3rd and 4th rosette leaves were incubated in darkness and characterized four days after dark treatment (DAD). A stay-green phenotype was also observed on the leaves of ref6-1, in contrast to an obvious premature yellowing on those of ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA (Fig 2E). Their phenotypic observations were validated by their measurements of Chl content (Fig 2F).

Finally, we checked whether NYE1 overexpression could rescue the stay-green phenotype of ref6-1 by using an in situ transient expression system. We first infiltrated one half of a ref6-1’s leaf with Agrobacteria containing NYE1 expression vector and found that it turned yellow two days after infiltration while the other half of the leaf transfected with Agrobacteria containing the empty plasmid still stayed green (Fig 2G). Then, we overexpressed REF6 in nye1-1 and nye1 nye2 in the same manner and detected similar stay-green phenotypes between the two halves of a leaf transfected (Fig 2H). All the analyses convincingly demonstrate that REF6 requires NYE1/2 for promotion of Chl degradation during leaf senescence.

REF6 positively regulates the general leaf senescence process

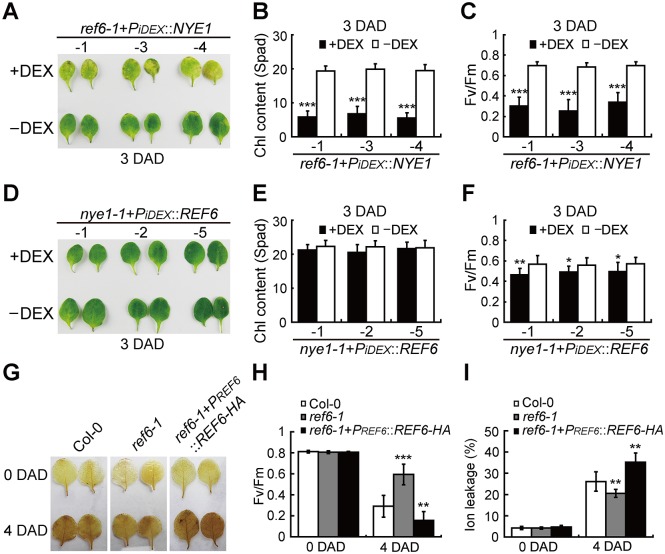

To confirm the above transient expression results, we overexpressed NYE1 in ref6-1 plants (ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1) and vise versa, REF6 in nye1-1 plants (nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6) by using a dexamethasone (DEX) induction system. After treated with 30 μM chemical inducer DEX, ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1 transgenic plants exhibited a yellowing phenotype compared with the untreated control on 3 DAD (Fig 3A and 3B and S2A Fig), whereas nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants displayed a stay-green phenotype similar to that of nye1-1 (Fig 3D and 3E and S2B Fig). These findings are consistent with the transient expression results. Interestingly, although Chl degradation was not affected, a significantly decreased Fv/Fm ratio was detected in nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants compared with un-induced controls (Fig 3C and 3F), which reminded us of that REF6 might also be involved in the regulation of other SAGs apart from NYEs.

Fig 3. Overexpression of REF6 and NYE1 in each other’s mutants confirms their roles in promoting the general leaf senescence process.

(A) Leaf phenotypes of ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1 transgenic plants treated with or without DEX on 3 DAD. -1, -3, and -4 represent different transgenic lines. (B, C) Chl contents (B) and Fv/Fm ratios (C) in the leaves shown in (A). (D) Leaf phenotypes of nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants treated with or without DEX on 3 DAD. -1, -2, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. (E, F) Chl contents (E) and Fv/Fm ratios (F) in the leaves shown in (D). (G-I) H2O2 levels detected by DAB staining (G), Fv/Fm ratios (H), and Ion leakage (I), in ref6-1, Col-0, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants on 4 DAD. Data are mean ± SD (n = 10). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test.

Subsequently, we examined the major senescence parameters of both REF6’s loss-of-function mutant (ref6-1) and its native promoter-driven overexpression lines (ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA) during both dark-induced and age-triggered leaf senescence. It was found that, on 4 DAD, the Fv/Fm ratio remained higher while the ion leakage and H2O2 content lower in the 3rd and 4th detached rosette leaves of 25-day-old ref6-1 plants than those in Col-0, and the exact opposite trends in the changes of the senescence parameters were observed in ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA (Fig 3G–3I) [59, 60]. Consistently, 40 days after germination under long-day growth conditions, a significantly higher Fv/Fm ratio and a significantly lower Fv/Fm ratio were detected in the 3rd and 4th rosette leaves of ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants, respectively (S3 Fig). These results confirm that REF6 indeed regulates the general leaf senescence process.

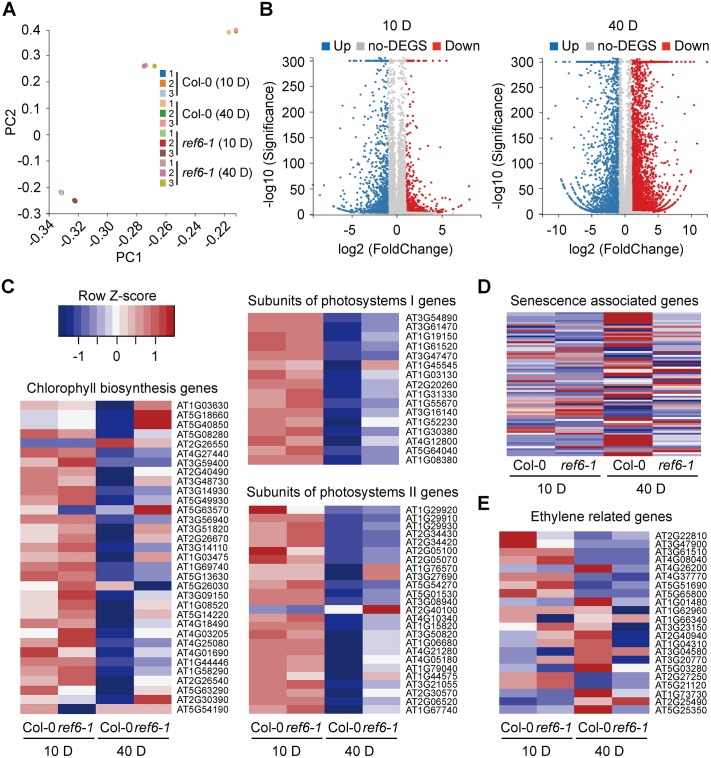

REF6 promotes the transcription of dozens of SAGs during leaf senescence

To examine the effect of loss-of-REF6 function on the global gene expression pattern, we did a comparative RNA-seq analysis of the 10-day-old seedlings and 40-day-old rosette leaves of both ref6-1 and Col-0 plants. In total, 25,044 expressed genes were identified from all the samples. PCA analysis showed that in the rosette leaves, the transcriptional difference between Col-0 and ref6-1 was much more significant in comparison to that in the seedlings (Fig 4A): a total of 6,106 differentially expressed genes (DEGs, those with more than 2.0-fold change in transcription) were identified in the rosette leaves compared to 1,319 DEGs in the seedlings (Fig 4B and S1 Table). The decline in leaf photosynthetic capacity is correlated with the progression of leaf senescence [61], and expectedly, a large number of Chlorophyll biosynthesis- and photosynthesis-related genes were down-regulated much less rapidly in ref6-1 than those in Col-0 (Fig 4C and S2 Table). By contrast, among the previously identified 74 SAGs [62], 33 were up-regulated far less significantly in ref6-1 than those in Col-0 (Fig 4D and S2 Table). These analyses provide evidence that REF6 significantly promotes the general leaf senescence process via up-regulating the transcription of major SAGs. Notably, by referring to the SAGs database set up by Liu et al. [62], we found that the up-regulated transcription of quite a few of the SAGs relating to ethylene biosynthesis, signaling or response was significantly compromised in the 40-day-old rosette leaves of ref6-1 (Fig 4E and S2 Table), implying that ethylene signaling and/or biosynthesis might be largely responsible for mediating REF6-regulated leaf senescence.

Fig 4. Transcriptome analysis of Col-0 and ref6-1 mutant.

(A) Principle component analysis of log2-transformed transcriptome data of 12 samples. (B) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for Col-0 and ref6-1 investigated in this work (10-day-old seedlings, left; 40-day-old rosette leaves, right). The y-axis corresponds to the mean expression value of -log10 (q-value), and the x- axis displays the log2-fold change value. (C-E) Heat map showing the expression of chlorophyll biosynthesis, subunit genes of photosystems I and II (C), senescence associated genes (D), and ethylene related genes (E) in 10-day-seedlings and 40-day-old leaves of Col-0 and ref6-1.

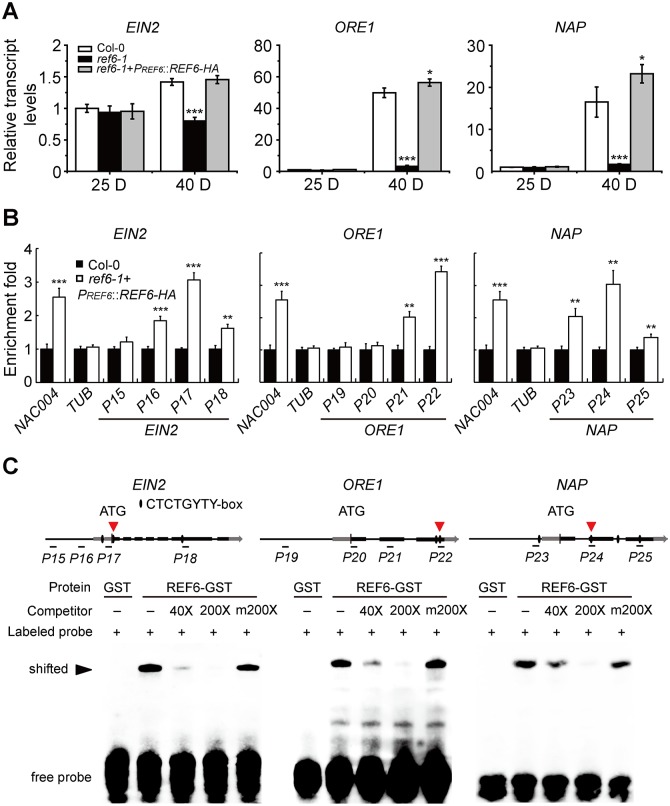

REF6 directly activates the transcription of its target SAGs

To identify the SAGs directly activated by REF6, we analyzed the overlap between REF6 target genes [11] and the SAGs significantly down-regulated in the 40-day-old rosette leaves of ref6-1 (S3 Table), and revealed three ethylene signaling genes, EIN2, ORE1, and NAP [51, 63], as well as other five SAGs, PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, AtNAC3, and NTL9, as REF6 candidate target SAGs. The ethylene signaling pathway has been elucidated as a key hormonal signaling pathway in regulating age-triggered leaf senescence [49, 51, 52], and we therefore focused on the analysis of EIN2, ORE1, and NAP’s involvement. To preliminarily examine the regulatory relationship of the three ethylene signaling genes with REF6, we measured their transcript levels and found that their enhancements in transcription with aging were significantly reduced in ref6-1 while apparently increased in ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA compared to those in Col-0 (Fig 5A). The in vivo association of REF6 with the three genes was examined by ChIP-qPCR assays, and it was found that REF6 was associated with all the three genes in their coding regions but not in their promoter regions, with 3.0-, 3.5-, and 3.0-fold enrichments in the coding regions of EIN2 (EIN2-P17), ORE1 (ORE1-P22), and NAP (NAP-P24), respectively (Fig 5B). By scanning their genomic regions, CTCTGYTY motifs were identified mainly in their coding regions instead of their promoters. With the ChIP data as a reference, an EMSA was performed to examine whether REF6 protein could directly bind to the CTCTGYTY motifs in their coding regions. Indeed, bindings were detected within the coding regions of all the three genes (Fig 5C). These results indicate that REF6 modulates leaf senescence likely by directly up-regulating EIN2, ORE1, and NAP, and presumably, other five candidate target SAGs as well (CTCTGYTY motifs were also detected in their coding/promoter regions (S4A Fig).

Fig 5. REF6 directly up-regulates the transcription of EIN2, ORE1, and NAP.

(A) Relative transcript levels of EIN2, ORE1, and NAP genes in the leaves detached from 25-day-old or 40-day-old Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants grown under long day-growth conditions. (B) ChIP assays of in vivo binding of REF6-HA to EIN2, ORE1, and NAP promoters and coding regions in the 10-day-old seedlings of ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA and Col-0 plants. Fold enrichments were calculated as described previously. Primers are listed in S4 Table. NAC004 gene was used as a positive control, whereas TUB as a negative control. In (A) and (B), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test. (C) EMSAs of in vitro binding of REF6 to the CTCTGYTY motifs within the ChIP-PCR fragments P17, P22, and P24 of EIN2, ORE1, and NAP coding regions (indicated with red arrows). Probe sequences used in EMSA are: 5’-AGGAACCATTCTCTGGATAAACCCTAGC-3’ for EIN2, 5’-TACTCGGATCCTCTGTTTTTACAAGACA-3’ for ORE1, and 5’-TTTCTCCAAACTCTGTTTTCTCTGTAAA-3’ for NAP.

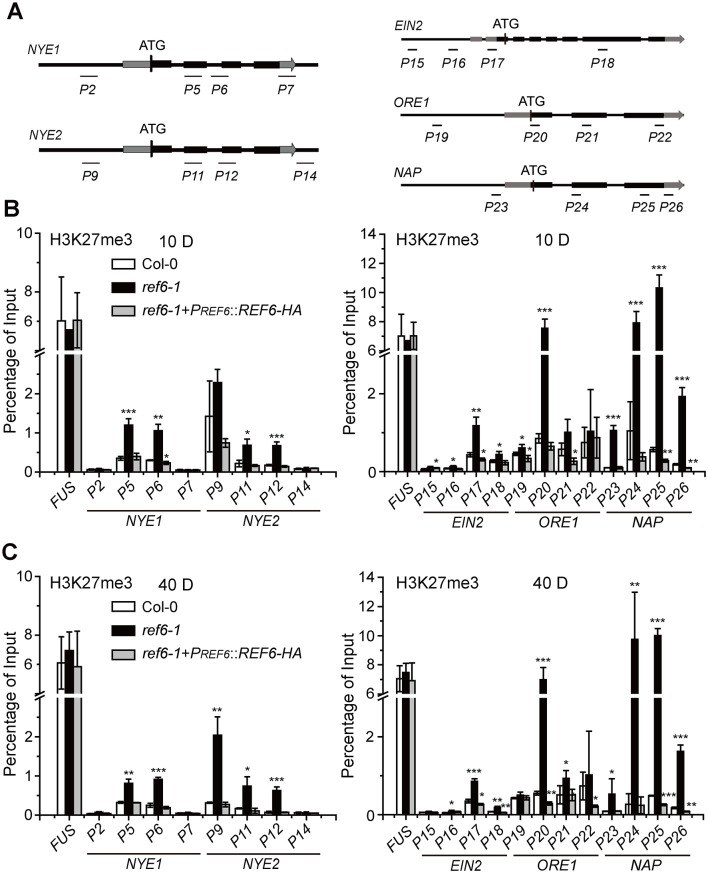

REF6 promotes the transcription of its ten target SAGs by reducing their H3K27me3 levels

Previous reports revealed that the expression of genes is tightly restricted by a high level of H3K27me3 [6], and loss-of-function of REF6 caused a genome-wide H3K27me3 hypermethylation [11]. We then hypothesized that REF6 might directly promote the transcription of its target SAGs by reducing their H3K27me3 levels. To test this hypothesis, we measured H3K27me3 level at these SAGs in the 10-day-old seedlings (Fig 6A and 6B and S4A and S4B Fig) and 40-day-old leaves (Fig 6A and 6C and S4A and S4C Fig) of both ref6-1 and Col-0 plants. It was detected that H3K27me3 levels were significantly higher in ref6-1 than in Col-0 plants at all the ten SAGs, and notably, between ref6-1 and Col-0, much bigger differences at H3K27me3 level were revealed at ORE1, NAP, NAC3, and NTL9 in both the 10-day-old seedlings and the 40-day-old leaves (Fig 6 and S4 Fig). We also found that H3K27me3 levels at all the ten genes were lower in the 40-day-old leaves than those in the 10-day-old seedlings of both Col-0 and ref6-1 plants, suggesting that the H3K27me3 on these SAGs are gradually cleared up by REF6 as well as other related demethylases towards the initiation of leaf senescence. These data demonstrate that REF6 facilitates the expression of its ten target SAGs during the initiation/progression of leaf senescence by reducing their H3K27me3 levels.

Fig 6. Loss-of-function of REF6 increases H3K27me3 levels at NYE1/2, EIN2, ORE1, and NAP genes.

(A) Schematic diagrams of NYE1/2, EIN2, ORE1, and NAP genes and positions of the primers used for determining their H3K27me3 levels. Primer sequences are listed in S4 Table. (B) H3K27me3 levels of NYE1/2, EIN2, ORE1, and NAP genes, expressed as the percentage of input, in the 10-day-old seedlings of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. (C) H3K27me3 levels of NYE1/2, EIN2, ORE1, and NAP genes in the leaves detached from the 40-day-old plants of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. In (B)—(C), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

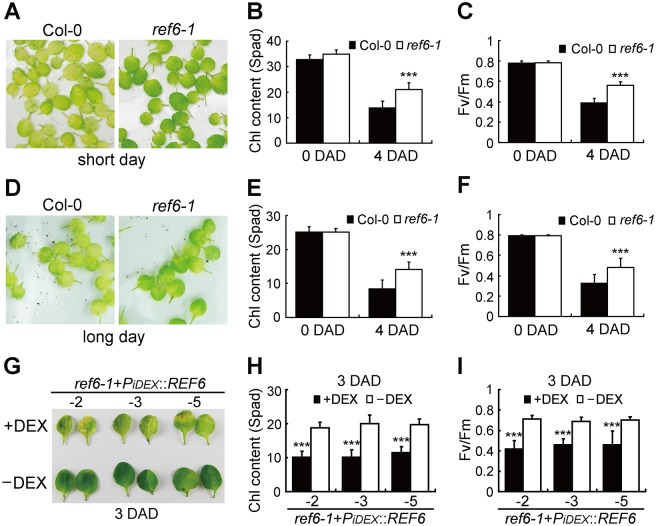

REF6-promoted leaf senescence is independent of plant development

It has been found that early leaf senescence is always accompanied with early flowering, but delayed leaf senescence does not necessarily cause late flowering [64]. Some histone modification factors were reported to affect both flowering time and leaf senescence process [19, 20, 24]. Since ref6-1 is an obvious late-flowering mutant, we wondered whether its delayed leaf senescence is associated with a delayed plant development. To minimize a possible influence of plant development on leaf senescence, the detached rosette leaves of 40-day-old Col-0 and ref6-1 plants (whole plants were still in vegetative growth) under short day-growth conditions were dark treated for 4 days to examine their dark-induced senescence phenotypes. It was found that the leaves of ref6-1 plants exhibited an obvious stay-green phenotype compared to those of Col-0 (Fig 7A). The measurements of Chl content (Fig 7B) and Fv/Fm ratio (Fig 7C) were consistent with the phenotypic observations. Similar results were obtained on 4 DAD with the rosette leaves of 14-day-old plants under long day-growth conditions (Fig 7D–7F), implying that the stay-green phenotype of ref6-1 is independent of plant development. To manifest a direct role of REF6 in promoting leaf senescence, a dexamethasone (DEX)-induced expression of REF6 was designed and performed. Rosette leaves of 25-day-old ref6-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants (under long day-growth conditions) were treated with 30 μM chemical inducer DEX, and a stronger yellowing phenotype was observed on 3 DAD, as compared with those of un-induced controls (Fig 7G–7I and S2C Fig). These results convincingly demonstrate that REF6 directly promotes leaf senescence independently of plant development.

Fig 7. REF6 regulates leaf senescence independently of plant development.

(A) Phenotypes of the leaves detached from 40-day-old ref6-1 and Col-0 plants grown under short day-growth conditions on 4 DAD. (B, C) Chl contents (B) and Fv/Fm ratios (C) in the leaves shown in (A). (D) Phenotypes of the leaves detached from 14-day-old ref6-1 and Col-0 plants grown under long day-growth conditions on 4 DAD. (E, F) Chl contents (E) and Fv/Fm ratios (F) in the leaves shown in (D). (G) Leaf phenotypes of ref6-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants treated with or without DEX on 3 DAD. -2, -3, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. (H, I) Chl contents (H) and Fv/Fm ratios (I) in the leaves shown in (G). In (B), (C), (E), (F), (H), and (I), data are mean ± SD (n = 10). ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test.

Discussion

REF6-catalyzed H3K27me3 demethylation is involved in the regulation of leaf senescence

Epigenetic modifications, especially histone methylations, have been implicated in the regulatory process of leaf senescence [19, 65, 66]. During leaf senescence, genes showing an increase in H3K4me3 mark are up-regulated, while those showing a decrease in H3K4me3 mark are down-regulated. Interestingly, for H3K27me3 modification, the trends are just opposite [65, 66]. A previous report specifically revealed that the early-senescence activation of WRKY53, a key regulatory gene of leaf senescence, occurs concomitantly with a significant increase in active H3K4 marks but without a significant change in inactive H3K27 marks at its 5’ end and coding regions [19]. Just immediately before our resubmission, an online paper showed that an H3K4 specific demethylase, JMJ16, is apparently involved in this process by demethylating H3K4 at WRKY53 as well as SAG201 to prevent precocious leaf senescence in mature leaves [67]. Intriguingly, the ectopic overexpression of SUVH2, a histone methyltransferase gene, significantly impaired the increase in H3K4 marks at both its 5’ end and coding regions but caused a significant increase in H3K27 marks at its 5’ end, repressing its transcription and consequently delaying leaf senescence [20]. These findings suggest a kind of the involvement of histone methylations in the regulation of leaf senescence. Nevertheless, very little is known about the in vivo details of their involvement in the regulation of developmental leaf senescence. In this study, we identified an H3K27me3 demethylase, REF6, as a direct transcriptional regulator of NYE1/2, which is responsible for catalyzing Chl degradation during leaf senescence. Further analyses demonstrated that REF6 is also directly involved in the transcriptional regulation of major senescence regulatory and functional genes, which mediate ethylene signaling (EIN2, ORE1, and NAP) [51], abscisic acid/abiotic stress signaling (AtNAC3 and NTL9) [68, 69], jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis (LOX1) [70], salicylic acid biosynthesis/signaling (PAD4) [71], and nitrogen remobilization (PPDK) [72] during leaf senescence. Consistently, as leaves age, REF6 reduces H3K27me3 level at all the ten genes. The loss-of-function mutation or ectopic overexpression of REF6 significantly alters the initiation/progression dynamics of both Chl degradation and the general leaf senescence. Notably, REF6-upreglated Chl degradation and leaf senescence is independent of the developmental process of the whole plant. Based on the above findings, we for the first time reveal the involvement of a methylation status regulator, REF6, in the regulation of both Chl degradation and the general leaf senescence process.

H3K27 methylation is an important epigenetic modification involved in the regulation of gene expressions. In Arabidopsis, a genome-wide profiling identified 10 to 20% of genes that are marked by H3K27me3, depending on plant organs or their developmental states [2, 73]. The absence of REF6 incurs a genome-wide H3K27me3 hypermethylation, implying that REF6 might regulate a variety of growth and developmental processes [11]. Compared with those in 10-day-old seedlings, significant decreases in H3K27me3 level at all the ten genes in the 40-day-old leaves of ref6-1 suggest that REF6 may not be the only demethylase responsible for H3K27me3 demethylation as leaves age. To check whether ELF6, another identified H3K27me3 demethylase, is possibly involved in this process, the dark-induced senescence phenotypes of elf6-5 and ref6-1 elf6-5 were examined four days after treatment in darkness (S5 Fig). It was found that the elf6-5 mutant showed a similar senescence phenotype to that of Col-0, and no obvious differences were detected in their senescence phenotype between ref6-1 elf6-5 double mutant and ref6-1 single mutant. The observations suggest that ELF6 might not play a substantial role in regulating Chl degradation and leaf senescence, which is reminiscent of that ELF6 also plays a role different from that of REF6 in regulating flowering [14, 74]. Further efforts are needed to identify additional demethylase(s) responsible for H3K27me3 demethylation during the aging of leaves.

REF6 represents a new catalog of SAGs

SAGs are generally identified by their elevated transcription during senescence. We measured the relative transcript levels of REF6 in the different tissues of Col-0 plants, and found that REF6 had a high transcript level in the flower and capsule (S6A Fig). We also measured its relative transcript levels during the aging of leaves and during dark treatment. The transcription of REF6 increased but not greatly from day 10 to day 25, even more gently from day 25 to day 40 (S1 Fig); similarly, during dark-induced senescence, the transcription of REF6 elevated only slightly (S6B Fig). These measurements suggest that REF6 is not a typical kind of SAGs in this regard, but represents a new catalog of SAGs that act to up-regulate the expression of other SAGs, likely through enriching their protein abundance or enhancing their enzymatic activity during senescence. As an enzyme, REF6 was once proposed to be recruited by NF-YA and BES1 onto its targets [15, 16]. Surprisingly, it was recently revealed that REF6 could directly bind to the CTCTGYTY motif of its targets via its zinc finger domain [17, 18], with CUC1 and PIN 1/3/7 being subsequently reported regulated as such [17, 75]. Here we demonstrate that the binding of REF6 to its targets could be mediated by the CTCTGYTY motifs located not only in the promoters but also in the coding regions (EIN2, ORE1, NAP, PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, and NTL9) of SAGs.

H3K27me3 methylation is an epigenetic mechanism hindering the premature transcriptional activation of key SAGs

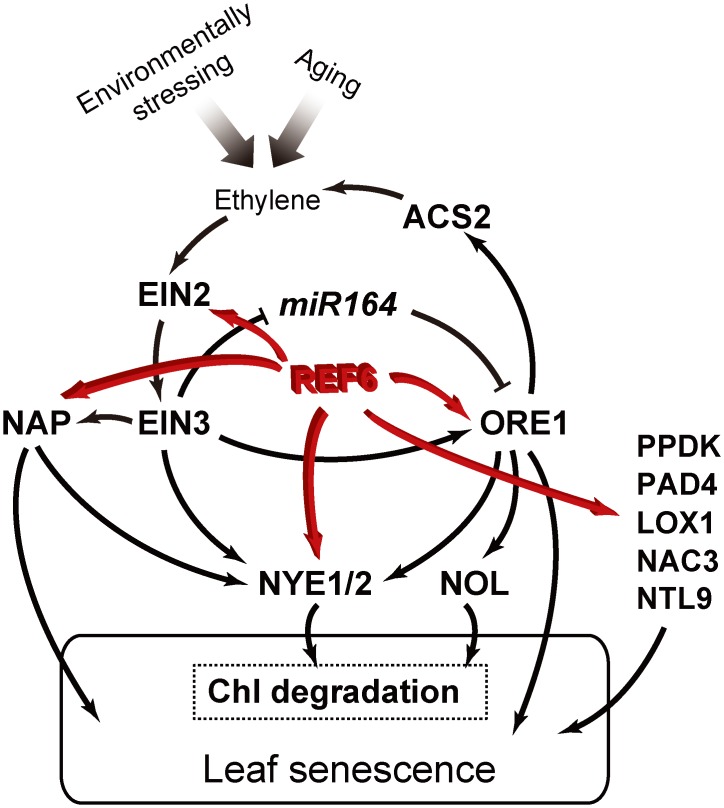

Leaf senescence is initiated with a genome-wide transcriptional reprogramming [63, 76], and a large number of transcriptionally-enhanced SAGs have been identified over the last decade or so, some of which were found to function as modules [26, 77–79]. Nevertheless, a fundamental question remains unanswered, i.e. by which mechanism(s) these SAGs are kept transcriptionally silenced before the initiation of senescence. In this study, we show that REF6 directly upregulates ten major SAGs and is responsible for their H3K27me3 demethylation during the aging process of leaves (Fig 6 and S4 Fig), and importantly, loss-of-function of REF6 represses their transcription, whereas overexpression of REF6 enhances their transcription (Figs 2A, 4D and 5A and S1–S3 Tables), consequently causing a change in the dynamics of leaf senescence initiation (Fig 2C–2F). EIN2, ORE1, and NAP, interconnected with EIN3 and miR164, form the framework of a core regulatory module (Fig 8) primarily responsible for the regulation of developmental leaf senescence as well as Chl degradation [46, 49, 51, 52]. Meanwhile, we found that ref6-1 mutant showed insensitivity to ethylene treatment compared with Col-0 (S7 Fig). Our findings suggest that H3K27me3 methylation is an epigenetic mechanism hindering the premature transcriptional activation of key SAGs activated by major phytohormones’ and stresses’ signaling, ethylene signaling in particular. Our findings help to explain the “aging effect” on senescence induction [55, 56]. The scope and extent of H3K27me3 methylation as a prohibiting mechanism to other SAGs’ premature transcriptions need to be further investigated.

Fig 8. Major target SAGs of REF6 in the regulation of leaf senescence.

ORE1 and NAP, acting downstream of EIN2 and EIN3, are the two major NAC transcription factors responsible for promoting Chl degradation and leaf senescence by up-regulating the expression of NYE1/2 as well as other SAGs. EIN3 is also involved in a feed-forward regulation by directly suppressing the expression of miR164, which targets ORE1 at the post-transcriptional level [46, 49, 51–54]. In this study, it is revealed that, during leaf senescence, REF6 directly facilitates the activation of the whole pathway by reducing the H3K27me3 level at EIN2, ORE1, and NAP [51] as well as AtNAC3, NTL9, LOX1, PAD4 and PPDK [68–72].

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All mutants and transgenic lines were derived from Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) unless stated otherwise. Generation and identification of nye1 nye2 were carried out as described previously [39, 58]. The ref6-1, elf6-5, ref6-3 ef6-5 mutants and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants were kindly provided by Dr. Xiaofeng Cao (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing). To generate nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6, ref6-1+PiDEX::REF6, and ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1 transgenic lines, the full-length coding sequences (CDS) of REF6 and NYE1 were PCR amplified and cloned into the vector pTA7002, respectively. The resultant constructs were introduced into nye1-1 and ref6-1 mutant plants, respectively, by using the floral-dipping method.

Seeds were germinated in soil and plants were grown at 23 °C under 16-h light/8-h dark for long day conditions or 16-h dark/8-h light for short day conditions in a growth room equipped with cool-white fluorescent lights (90–100 μmol m-2 s-1) unless indicated otherwise. The 3rd and 4th rosette leaves from 25-day-old soil-grown plants were incubated in complete darkness as described previously [39].

Y1H screening

Y1H screening is performed with the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid Library Screening System (Clontech). The bait fragment (the -532 bp fragment of NYE1 promoter, [57]) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the pAbAi vector. The resultant vector was subsequently linearized and introduced into the yeast strain Y1H Gold to generate a bait-reporter strain, which was then used to screen a cDNA library generated from detached leaves incubated in darkness for 12 h. Approximately 5×105 transformants were initially screened out on plates containing SD/-Leu media supplemented with 100 ng/ml Aureobasidin A. Prey fragments were identified from the positive colonies by DNA sequencing. For re-transformation assay, the full-length coding sequence of REF6 was amplified from Col-0 cDNA by use of gene-specific primers (S4 Table). The PCR products were then cloned into the pGADT7 (Clontech) prey vector and the resultant vectors were subsequently transferred into the previously mentioned bait-reporter yeast strain.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were extracted by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and DNA remnants were removed by Dnase I (Takara) treatment. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized with the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara) and used as templates for quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq TM (Takara). The qPCR analyses were carried out with the MyiQ5 Real Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). ACTIN2 (AT3g18780) was used as an internal reference to normalize the qPCR data. Gene-specific primers are listed in S4 Table.

RNA-sequencing and data analysis

Total RNA of the whole seedlings or detached leaves was extracted by using a Trizol kit (Takara). Fifty bp single end RNA-sequencing was conducted by using the BGISEQ-500 platform established by Beijing Genomics Institute, and the reads were aligned by using Bowtie 2 instead of Bowtie [80]. A gene with a cut-off value of two-fold change and p-value less than 0.01 was defined as a differentially expressed gene. R program “princomp” was used to conduct PCA analysis. Heatmap.2 in the ‘gplots’ package of R program was used for the construction of heat maps.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

An REF6C (encoding amino acids 1,239–1,360) fragment was cloned into pGEX-6p-1, and GST-REF6C recombinant fusion protein and GST protein were then expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21 codon plus, Stratagene) and purified with glutathione sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). Biotin-labeled DNA probes are listed in S4 Table. Unlabeled competitors were added in 400-fold molar excess. EMSA is carried out with the Light Shift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific). 20 μl reaction mixture contained 2 μl binding buffer, 0.3 μl poly (dI-dC), 4 μg purified fusion protein and 1 μl biotin-labeled annealed oligonucleotides. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, the reaction mixture was electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide mini-gel (containing 3% glycerol), then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences), which was illuminated by use of an ultraviolet lamp for cross-linking. Biotin-labeled DNA was detected with Pierce chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed as described previously [17] with slight modifications. For measuring REF6 enrichments: chromatins were isolated from about 2 g of formaldehyde cross-linked rosette leaves from 10-day-old transgenic plants and Col-0 plants. For the determination of H3K27me3 levels, chromatins were isolated from about 2 g of formaldehyde cross-linked rosette leaves of 10-day-old seedlings and 40-day old leaves of Col-0 and ref6-1 plants, respectively, which were then sonicated to produce 0.2- to 1-kb DNA fragments with a Branson sonicator (40-s bursts at -88 watts). The lysates were diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer to decrease the concentration of SDS to 0.1%, which was then cleared by centrifugation (16,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C). After 5% being taken out and used as input, the rest supernatant was incubated with the antibodies for HA (Sigma, H6908) or H3K27me3 (Millipore, 07–449) overnight at 4 °C. Chromatin was collected by using Protein A/G magnetic beads, then washed, eluted, and reverse cross-linked, and DNA purification was then performed. DNA fragments were purified by using the ChIP-qPCR purification kit (Zymo Research). The purified DNA was re-suspended in double-distilled water, and enriched DNA fragments were quantified by qPCR with the primers listed in S4 Table. Input samples were reverse–cross-linked and used to normalize the qPCR data for each ChIP sample.

Ethylene treatment

Ethylene treatment was carried out principally as reported [81]. Ethephon was purchased from Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Co., and leaves were treated in an air-tight container (desiccator). A1 Methephon stock solution was prepared with ethanol, and 86.5 μl of the stock solution were added to 200 ml of 5 mM Na2HPO3 placed in a 17.3 L desiccator to create the 5 μM air concentration of ethylene. The cover was closed immediately after addition, and the desiccator was placed under light or in the dark according to the requirement of the experimental design.

Measurements of Ion leakage rates

Before or after a 4-day treatment in the dark, the detached leaves were incubated in deionized water for at least 4 h (< 10 h), and small fractions of the elution water solutions were subsequently taken out for the initial value determination (C1). The leaf samples were then boiled in the same deionized water for 15 min. After cooling, the elution water solutions were determined again (C2) [49]. The ratio of C1: C2 was calculated as the percentage of ion leakage. We used 3 ml deionized water for one leaf measurement in a 5-ml centrifuge tube.

Measurements of Chl contents and Fv/Fm ratios

Chl contents were measured by using SPAD-502 PLUS, and maximal photochemical efficiencies of PSII (Fv/Fm) were measured with LI-COR6400 (http://www.licor.com/env/products/photosynthesis) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean ± SD and were analyzed by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA.

Accession numbers

NYE1 (AT4G22920), NYE2 (AT4G11910), EIN2 (AT5G03280), ORE1/NAC2/NAC092 (AT5G39610), NAP (AT1G69490), REF6 (AT3G48430), ACTIN2 (AT3G18780), UBQ (AT4G05320), GPAT4 (AT1G01610), NAC004 (AT1G02230), TUB (AT5G62690), PAD4 (AT3G52430), PPDK (AT4G15530), LOX1 (AT1G55020), NAC3 (AT3G15500), NTL9 (AT4G35580). RNA-seq data obtained in this study were deposited at the NCBI short read archive under Bioproject identifier PRJNA518728 with accession number: SRR8518110 to SRR8518121.

Supporting information

(A) Abundances of semi-quantitative RT-PCR products of REF6 in the leaves detached from 10-day-old or 40-day-old Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants grown under long day-growth conditions. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the leaves detached from 10-day-old, 25-day-old, or 40-day-old Col-0, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants grown under long day-growth conditions. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Relative transcript levels of NYE1 in 25-day-old ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1 transgenic plants grown under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -1, -3, and -4 represent different transgenic lines. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in 25-day-old nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -1, -2, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. (C) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in 25-day-old ref6-1+PiDEX::REF6 plants under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -2, -3, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. In (A)-(C), data are mean ± SD (n = 3), **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

Fv/Fm ratios were determined in the 25-day and 40-day old rosette leaves of ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants as well as Col-0 and nye1 nye2 plants. Data are mean ± SD (n = 10). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Schematic diagrams of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3, and NTL9 genes and positions of the primers used for determining their H3K27me3 levels. Primer sequences are listed in S4 Table. (B) H3K27me3 levels of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3, and NTL9, expressed as the percentage of input, in the 10-day-old seedlings of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. (C) H3K27me3 levels of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3 and NTL9 genes in the leaves detached from the 40-day-old plants of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. In (B)—(C), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Senescence phenotypes of the leaves of indicated genotypes on 4 DAD. Leaves were detached from 25-day-old plants under long day-growth conditions. (B, C) Chl contents (B) and Fv/Fm ratios (C) in the leaves shown in (A). Data are mean ± SD (n = 10). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(A) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the different tissues of Col-0 plants. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the leaves of Col-0 plants after dark treatment. In (A) and (B), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(A) Senescence phenotypes of the attached leaves of 25-day-old Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants two days after ethylene treatment. (B) Senescence phenotypes of the leaves detached from 25-day-old Col-0 and ref6-1 plants two days after ethylene treatment. (C) Chl contents in the leaves shown in (A). (D) Chl contents in the leaves shown in (B). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. XiaoFeng Cao (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing) for providing ref6-1 mutants and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA transgenic plants, and for Dr. Yan Zhu (Fudan University, Shanghai) for his advice.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31670287, 31170218), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (15JC1400800), and State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering to BK and XZ. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Liu C, Lu F, Cui X, Cao X. Histone methylation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010; 61:395–420. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.091939 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007; 447:407–412. 10.1038/nature05915 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathieu O, Probst AV, Paszkowski J. Distinct regulation of histone H3 methylation at lysines 27 and 9 by CpG methylation in Arabidopsis. Embo J. 2005; 24:2783–2791. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600743 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs J, Demidov D, Houben A, Schubert I. Chromosomal histone modification patterns—from conservation to diversity. Trends. Plant Sci. 2006; 11:199–208. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pien S, Grossniklaus U. Polycomb group and trithorax group proteins in Arabidopsis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007; 1769:375–382. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.01.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Clarenz O, Cokus S, Bernatavichute YV, Pellegrini M, Goodrich J, et al. Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2007; 5:e129 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050129 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennig L, Derkacheva M. Diversity of Polycomb group complexes in plants: same rules, different players? Trends Genet. 2009; 25:414–423. 10.1016/j.tig.2009.07.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y, Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Kondo S, Motoyama J, et al. Gene trap capture of a novel mouse gene, jumonji, required for neural tube formation. Gene Dev. 1995; 9:1211–1222. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2006; 7:715–727. 10.1038/nrg1945 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, et al. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006; 439:811–816. 10.1038/nature04433 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu F, Cui X, Zhang S, Jenuwein T, Cao X. Arabidopsis REF6 is a histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase. Nat Genet. 2011; 43:715–719. 10.1038/ng.854 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crevillen P, Yang H, Cui X, Greeff C, Trick M, Qiu Q, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming that prevents transgenerational inheritance of the vernalized state. Nature, 2014; 515:587–590. 10.1038/nature13722 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gan ES, Xu Y, Wong JY, Goh JG, Sun B, Wee WY, et al. Jumonji demethylases moderate precocious flowering at elevated temperature via regulation of FLC in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014; 5:5098 10.1038/ncomms6098 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noh B. Divergent Roles of a Pair of Homologous Jumonji/Zinc-Finger-Class Transcription Factor Proteins in the Regulation of Arabidopsis Flowering Time. Plant Cell. 2004; 16:2601–2613. 10.1105/tpc.104.025353 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X, Li L, Li L, Guo M, Chory J, Yin Y. Modulation of brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression by Jumonji domain-containing proteins ELF6 and REF6 in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008; 105:7618–7623. 10.1073/pnas.0802254105 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou X, Zhou J, Chang L, Lu L, Shen L, Hao Y. Nuclear factor Y-mediated H3K27me3 demethylation of the SOC1 locus orchestrates flowering responses of Arabidopsis. Nat Commun. 2014; 5:4601 10.1038/ncomms5601 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui X, Lu F, Qiu Q, Zhou B, Gu L, Zhang S, et al. REF6 recognizes a specific DNA sequence to demethylate H3K27me3 and regulate organ boundary formation in Arabidopsis. Nat Genet. 2016; 48:694–699. 10.1038/ng.3556 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Gu L, Lei G, Chen C, Wei CQ, Qi Q, et al. Concerted genomic targeting of H3K27 demethylase REF6 and chromatin-remodeling ATPase BRM in Arabidopsis. Nat Genet. 2016; 48:687–693. 10.1038/ng.3555 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ay N, Irmler K, Fischer A, Uhlemann R, Reuter G, Humbeck K. Epigenetic programming via histone methylation at WRKY53 controls leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2009; 58:333–346. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ay N, Janack B, Humbeck K. Epigenetic control of plant senescence and linked processes. J Exp Bot. 2014; 65:3875–3887. 10.1093/jxb/eru132 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himelblau E, Amasino RM. Nutrients mobilized from leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana during leaf senescence. J Plant Physiol. 2001; 158:1317–1323. 10.1078/0176-1617-00608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007; 58:115–136. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guiboileau A, Yoshimoto K, Soulay F, Bataillé MP, Avice JC. Masclaux-Daubresse C. Autophagy machinery controls nitrogen remobilizationat the whole-plant level under both limiting and ample nitrateconditions in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2012; 194:732–740. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04084.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas H, Howarth CJ. Five ways to stay green. J Exp Bot. 2000; 51:329–337. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakuraba Y, Schelbert S, Park SY, Han SH, Lee BD, Andres CB, et al. STAY-GREEN and chlorophyll catabolic enzymes interact at light-harvesting complex II for chlorophyll detoxification during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012; 24:507–518. 10.1105/tpc.111.089474 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuai B, Chen J, Hörtensteiner S. The biochemistry and molecular biology of chlorophyll breakdown. J Exp Bot. 2018; 69:751–767. 10.1093/jxb/erx322 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusaba M, Tanaka A. Rice NON-YELLOW COLORING1 is involved in light-harvesting complex II and grana degradation during leaf senescence. Plant Cell. 2007; 19:1362–1375. 10.1105/tpc.106.042911 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horie Y, Ito H, Kusaba M, Tanaka R, Tanaka A. Participation of chlorophyll b reductase in the initial step of the degradation of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-protein complexes in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284:17449–17456. 10.1074/jbc.M109.008912 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato Y, Morita R, Katsuma S, Nishimura M, Tanaka A, Kusaba M. Two short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases, NON-YELLOW COLORING 1 and NYC1-LIKE, are required for chlorophyll b and light-harvesting complex II degradation during senescence in rice. Plant J. 2009; 57:120–131. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03670.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meguro M, Ito H, Takabayashi A, Tanaka R, Tanaka A. Identification of the 7-hydroxymethyl chlorophyll a reductase of the chlorophyll cycle in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011; 23:3442–3453. 10.1105/tpc.111.089714 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimoda Y, Ito H, Tanaka A. Arabidopsis STAY-GREEN, Mendel’s Green Cotyledon Gene, Encodes Magnesium-Dechelatase. Plant Cell. 2016; 28:2147–2160. 10.1105/tpc.16.00428 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schelbert S, Aubry S, Burla B, Agne B, Kessler F, Krupinska K, et al. Pheophytin pheophorbide hydrolase (pheophytinase) is involved in chlorophyll breakdown during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009; 21:767–785. 10.1105/tpc.108.064089 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren G, Zhou Q, Wu S, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Huang J, et al. Reverse genetic identification of CRN1 and its distinctive role in chlorophyll degradation in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010; 52:496–504. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00945.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pružinská A, Tanner G, Anders I, Roca M, Hörtensteiner S. Chlorophyll breakdown: pheophorbide a oxygenase is a Rieske-type iron-sulfur protein, encoded by the accelerated cell death 1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003; 100:15259–15264. 10.1073/pnas.2036571100 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauenstein M, Christ B, Das A, Aubry S, Hörtensteiner S. A role for tic55 as a hydroxylase of phyllobilins, the products of chlorophyll breakdown during plant senescence. Plant Cell. 2016; 28:2510–2527. 10.1105/tpc.16.00630 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armstead I, Donnison I, Aubry S, Harper J, Hörtensteiner S, James C, et al. Cross-species identification of Mendel’s I locus. Science, 2007; 315:73 10.1126/science.1132912 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang H, Li M, Liang N, Yan H, Wei Y, Xu X, et al. Molecular cloning and function analysis of the staygreen gene in rice. Plant J. 2007; 52:197–209. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03221.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park SY, Yu JW, Park JS, Li J, Yoo SC, Lee NY, et al. The senescence-induced staygreenprotein regulates chlorophyll degradation. Plant Cell. 2007; 19:1649–1664. 10.1105/tpc.106.044891 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren G, An K, Liao Y, Zhou X, Cao Y, Zhao H, et al. Identification of a novel chloroplast protein AtNYE1 regulating chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007; 144:1429–1441. 10.1104/pp.107.100172 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato Y, Morita R, Nishimura M, Yamaguchi H, Kusaba M. Mendel’s green cotyledongene encodes a positive regulator of the chlorophyll-degrading pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104:14169–14174. 10.1073/pnas.0705521104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barry CS, McQuinn RP, Chung MY, Besuden A, Giovannoni JJ. Amino acid substitutions in homologs of the STAY-GREEN protein are responsible for the green-flesh and chlorophyll retainer mutations of tomato and pepper. Plant Physiol. 2008; 147:179–187. 10.1104/pp.108.118430 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou C, Han L, Pislariu C, Nakashima J, Fu C, Jiang Q, et al. From model to crop: functionalanalysis of a STAY-GREEN gene in the model legume Medicago truncatulaand effective use of the gene for alfalfa improvement. Plant Physiol. 2011; 157:1483–1496. 10.1104/pp.111.185140 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang C, Li C, Li W, Wang Z, Zhou Z, Shen Y, et al. Concerted evolution of D1 and D2 to regulate chlorophylldegradation in soybean. Plant J. 2014; 77:700–712. 10.1111/tpj.12419 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burg SP. Ethylene in plant growth Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973; 70:591–597. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grbic V, Bleecker AB. Ethylene regulates the timing of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1995; 8:595–602. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.8040595.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim JH, Woo HR, Kim J, Lim PO, Lee IC, Choi SH, et al. Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2009; 323:1053–1057. 10.1126/science.1166386 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin XR, Xie XL, Xia XJ, Yu JQ, Ferguson IB, Giovannoni JJ, et al. Involvement of an ethylene response factor in chlorophyll degradation during citrus fruit degreening. Plant J. 2016; 86:403–412. 10.1111/tpj.13178 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bisson MM, Bleckmann A, Allekotte S, Groth G. EIN2, the central regulator of ethylene signalling, is localized at the ER membrane where it interacts with the ethylene receptor ETR1. Biochem J. 2009; 424:1–6. 10.1042/BJ20091102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Z, Peng J, Wen X, Guo H. ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 Is a Senescence-Associated Gene That Accelerates Age-Dependent Leaf Senescence by Directly Repressing miR164 Transcription in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013; 25:3311–3328. 10.1105/tpc.113.113340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merchante C, Alonso JM, Stepanova AN. Ethylene signaling: simple ligand, complex regulation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013; 16:554–560. 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.08.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim HJ, Hong SH, Kim YW, Lee IH, Jun JH, Phee BK, et al. Gene regulatory cascade of senescence-associated NAC transcription factors activated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE2-mediated leaf senescence signalling in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2014; 65:4023–4036. 10.1093/jxb/eru112 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiu K, Li Z, Yang Z, Chen J, Wu S, Zhu X, et al. EIN3 and ORE1 Accelerate Degreening during Ethylene-Mediated Leaf Senescence by Directly Activating Chlorophyll Catabolic Genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2015; 11:e1005399 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005399 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo Y, Gan S. AtNAP, a NAC family transcription factor, has an important role in leaf senescence. Plant J. 2006; 46:601–612. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02723.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balazadeh S, Siddiqui H, Allu AD, Matallana-Ramirez LP, Caldana C, Mehrnia M, et al. A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J. 2010; 62:250–264. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04151.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jing HC, Sturre MJG, Hille J, Dijkwel PP. Arabidopsis onset of leaf death mutants identify a regulatory pathwaw controlling leaf senescence. Plant J. 2002; 32:51–63. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jing HC, Schippers JH, Hille J, Dijkwel PP. Ethylene-induced leaf senescence depends on age-related changes and OLD genes in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2005; 56:2915–2923. 10.1093/jxb/eri287 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao S, Gao J, Zhu X, Song Y, Li Z, Ren G, et al. ABF2, ABF3 and ABF4 promote ABA-mediated chlorophyll degradation and leaf senescence by transcriptional activation of chlorophyll catabolic genes and senescence-associated genes in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2016; 9:1272–1285. 10.1016/j.molp.2016.06.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S, Li Z, Yang L, Xie Z, Chen J, Wei Z, et al. NON-YELLOWING2 (NYE2), a Close Paralog of NYE1, Plays a Positive Role in Chlorophyll Degradation in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2015; 9:624–627. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.12.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas H. Sid: a Mendelian locus controlling thylakoid membrane disassembly in senescing leaves of Festuca pratensis. Theor Appl Genet. 1987; 73:551–555. 10.1007/BF00289193 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Navabpour S, Morris K, Allen R, Harrison E, A-H-Mackerness S, Buchanan-Wollaston V, et al. Expression of senescence-enhanced genes in response to oxidative stress. J Exp Bot. 2003; 54:2285–2292. 10.1093/jxb/erg267 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Field C, Mooney A. Leaf age and seasonal effects on light, water, and nitrogen use efficiency in a California shrub. Oecologia. 1983; 56:348–355. 10.1007/BF00379711 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li ZH, Peng JY, Wen X, Guo HW. Gene network analysis and functional studies of senescence-associated genes reveal novel regulators of Arabidopsis leaf senescence. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012; 54:526–539. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01136.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Breeze E, Harrison E, McHattie S, Hughes L, Hickman R, Hill C, et al. High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell. 2011; 23:873–894. 10.1105/tpc.111.083345 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wingler A. Interactions between flowering and senescence regulation and the influence of low temperature in Arabidopsis and crop plants. Ann Appl Biol. 2011; 159:320–338. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2011.00497.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brusslan JA, Rus Alvarez-Canterbury AM, Nair NU, Rice JC, Hitchler MJ, Pellegrini M, et al. Genome-wide evaluation of histone methylation changes associated with leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e33151 10.1371/journal.pone.0033151 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brusslan JA, Bonora G, Rus-Canterbury AM, Tariq F, Jaroszewicz A, Pellegrini M, et al. A Genome-Wide Chronological Study of Gene Expression and Two Histone Modifications, H3K4me3 and H3K9ac, during Developmental Leaf Senescence. Plant Physiol. 2015; 168:1246–1261. 10.1104/pp.114.252999 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu P, Zhang S, Zhou B, Luo X, Zhou X, Cai B, et al. The Histone H3K4 Demethylase JMJ16 Represses Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2019. 10.1105/tpc.18.00693 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takasaki H, Maruyama K, Takahashi F, Fujita M, Yoshida T, Nakashima K, et al. SNAC-As, stress-responsive NAC transcription factors, mediate ABA-inducible leaf senescence. Plant J. 2015; 84:1114–23. 10.1111/tpj.13067 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon HK, Kim SG, Kim SY, Park CM. Regulation of leaf senescence by NTL9-mediated osmotic stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Cells. 2008; 25:438–45. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He Y, Fukushige H, Hildebrand DF, Gan S. Evidence supporting a role of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2002; 128:876–84. 10.1104/pp.010843 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris K, MacKerness SA, Page T, John CF, Murphy AM, Carr JP, et al. Salicylic acid has a role in regulating gene expression during leaf senescence. Plant J. 2000; 23:677–85. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00836.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taylor L, Nunes-Nesi A, Parsley K, Leiss A, Leach G, Coates S, et al. Cytosolic pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase functions in nitrogen remobilization during leaf senescence and limits individual seed growth and nitrogen content. Plant J. 2010; 62(4):641–52. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04179.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.He XJ, Mu RL, Cao WH, Zhang ZG, Zhang JS, Chen SY. AtNAC2, a transcription factor downstream of ethylene and auxin signaling pathways, is involved in salt stress response and lateral root development. Plant J. 2005; 44:903–916. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02575.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hong EH, Jeong YM, Ryu JY, Amasino RM, Noh B, Noh YS. Temporal and spatial expression patterns of nine Arabidopsis genes encoding Jumonji C-domain proteins. Mol Cells. 2009; 27:481–490. 10.1007/s10059-009-0054-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X, Gao J, Gao S, Li Z, Kuai B, Ren G. REF6 promotes lateral root formation through de-repression of PIN1/3/7 genes. J Integr Plant Biol. 2018. 10.1111/jipb.12726 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo Y, Gan S. Convergence and divergence in gene expression profiles induced by leaf senescence and 27 senescence-promoting hormonal, pathological and environmental stress treatments. Plant Cell Environ. 2012; 35:644–655. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02442.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schippers JH, Schmidt R, Wagstaff C, Jing HC. Living to die and dying to live: the survival strategy behind leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2015; 169:914–930. 10.1104/pp.15.00498 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim J, Woo HR, Hong GN. Towards systems understanding of leaf senescence: an integrated multi-omics perspective on the leaf senescence research. Mol Plant. 2016; 9:813–825. 10.1016/j.molp.2016.04.017 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu X, Chen J, Qiu K, Kuai B. Phytohormone and light regulation of chlorophyll degradation. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8:1911 10.3389/fpls.2017.01911 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012; 9:357–9. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang W, Wen CK. Preparation of ethylene gas and comparison of ethylene responses induced by ethylene, ACC, and ethephon. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010; 48:45–53. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.10.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Abundances of semi-quantitative RT-PCR products of REF6 in the leaves detached from 10-day-old or 40-day-old Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants grown under long day-growth conditions. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the leaves detached from 10-day-old, 25-day-old, or 40-day-old Col-0, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants grown under long day-growth conditions. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Relative transcript levels of NYE1 in 25-day-old ref6-1+PiDEX::NYE1 transgenic plants grown under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -1, -3, and -4 represent different transgenic lines. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in 25-day-old nye1-1+PiDEX::REF6 transgenic plants under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -1, -2, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. (C) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in 25-day-old ref6-1+PiDEX::REF6 plants under long day-growth conditions with or without DEX treatment. -2, -3, and -5 represent different transgenic lines. In (A)-(C), data are mean ± SD (n = 3), **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

Fv/Fm ratios were determined in the 25-day and 40-day old rosette leaves of ref6-1 and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants as well as Col-0 and nye1 nye2 plants. Data are mean ± SD (n = 10). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Schematic diagrams of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3, and NTL9 genes and positions of the primers used for determining their H3K27me3 levels. Primer sequences are listed in S4 Table. (B) H3K27me3 levels of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3, and NTL9, expressed as the percentage of input, in the 10-day-old seedlings of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. (C) H3K27me3 levels of PPDK, PAD4, LOX1, NAC3 and NTL9 genes in the leaves detached from the 40-day-old plants of Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA grown under long day-growth conditions. In (B)—(C), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by paired Student’s t test.

(DOCX)

(A) Senescence phenotypes of the leaves of indicated genotypes on 4 DAD. Leaves were detached from 25-day-old plants under long day-growth conditions. (B, C) Chl contents (B) and Fv/Fm ratios (C) in the leaves shown in (A). Data are mean ± SD (n = 10). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(A) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the different tissues of Col-0 plants. (B) Relative transcript levels of REF6 in the leaves of Col-0 plants after dark treatment. In (A) and (B), data are mean ± SD (n = 3). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(A) Senescence phenotypes of the attached leaves of 25-day-old Col-0, ref6-1, and ref6-1+PREF6::REF6-HA plants two days after ethylene treatment. (B) Senescence phenotypes of the leaves detached from 25-day-old Col-0 and ref6-1 plants two days after ethylene treatment. (C) Chl contents in the leaves shown in (A). (D) Chl contents in the leaves shown in (B). Marking with different letters means a statistical significance at P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA test.

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.