Abstract

Background

A panic attack is a discrete period of fear or anxiety that has a rapid onset, reaches a peak within 10 minutes and in which at least four of 13 characteristic symptoms are experienced, including racing heart, chest pain, sweating, shaking, dizziness, flushing, stomach churning, faintness and breathlessness. Panic disorder is common in the general population with a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 4%. The treatment of panic disorder includes psychological and pharmacological interventions. Amongst pharmacological agents, antidepressants and benzodiazepines are the mainstay of treatment for panic disorder. Different classes of antidepressants have been compared; and the British Association for Psychopharmacology, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) consider antidepressants (mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)) as the first‐line treatment for panic disorder, due to their more favourable adverse effect profile over monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). In addition to antidepressants, benzodiazepines are widely prescribed for the treatment of panic disorder.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the effects of antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults.

Search methods

The Specialised Register of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMDCTR) to 11 September 2015. This register includes relevant randomised controlled trials from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐). Reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews were handsearched. We contacted experts in this field for supplemental data.

Selection criteria

All double‐blind randomised controlled trials allocating adult patients with panic disorder to antidepressants or benzodiazepines versus any other active treatment with antidepressants or benzodiazepines.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently checked eligibility and extracted data using a standard form. Data were entered in RevMan 5.3 using a double‐check procedure. Information extracted included study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention details, settings and outcome measures in terms of efficacy, acceptability and tolerability.

Main results

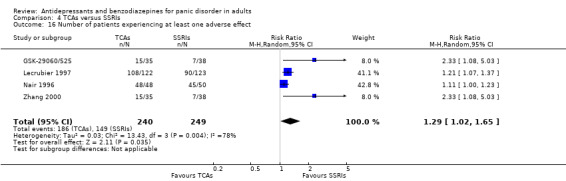

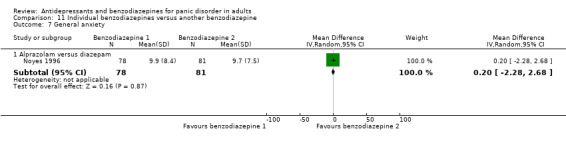

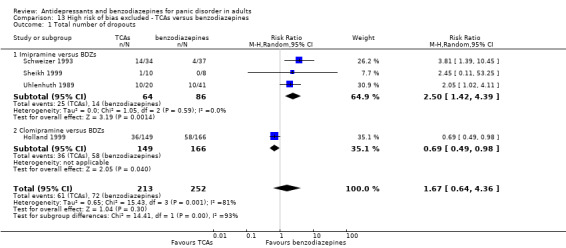

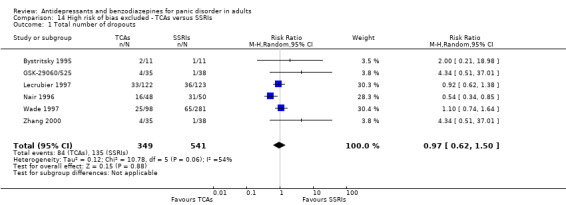

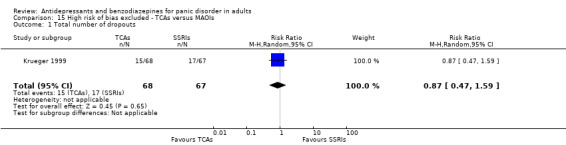

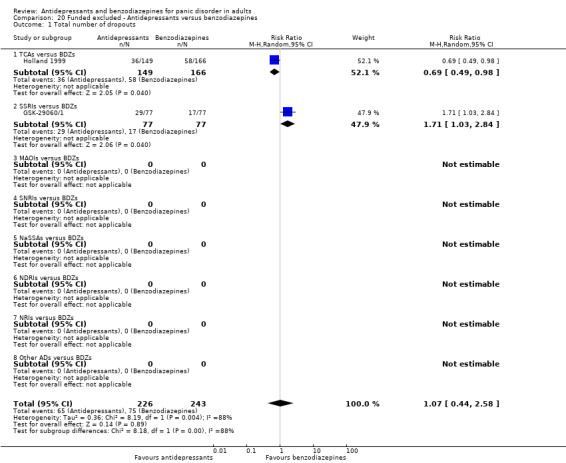

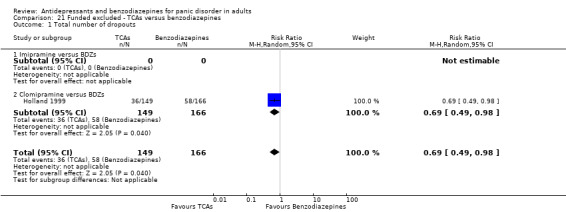

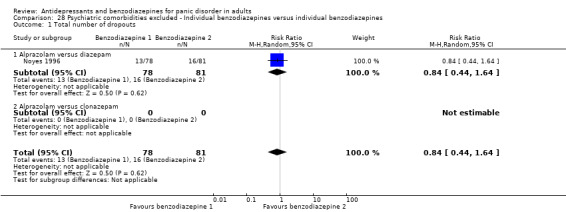

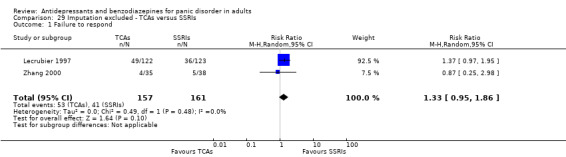

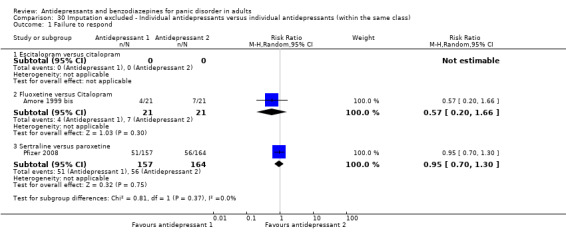

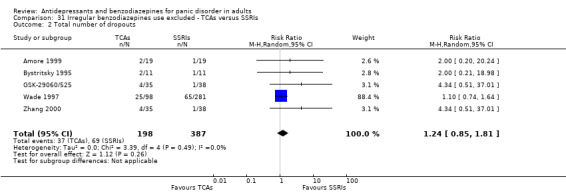

Thirty‐five studies, including 6785 participants overall (of which 5365 in the arms of interest (antidepressant and benzodiazepines as monotherapy)) were included in this review; however, since studies addressed many different comparisons, only a few trials provided data for primary outcomes. We found low‐quality evidence suggesting no difference between antidepressants and benzodiazepines in terms of response rate (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67 to 1.47; participants = 215; studies = 2). Very low‐quality evidence suggested a benefit for benzodiazepines compared to antidepressants in terms of dropouts due to any cause, even if confidence interval (CI) ranges from almost no difference to benefit with benzodiazepines (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.63; participants = 1449; studies = 7). We found some evidence suggesting that serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are better tolerated than TCAs (when looking at the number of patients experiencing adverse effects). We failed to find clinically significant differences between individual benzodiazepines. The majority of studies did not report details on random sequence generation and allocation concealment; similarly, no details were provided about strategies to ensure blinding. The study protocol was not available for almost all studies so it is difficult to make a judgment on the possibility of outcome reporting bias. Information on adverse effects was very limited.

Authors' conclusions

The identified studies are not sufficient to comprehensively address the objectives of the present review. The majority of studies enrolled a small number of participants and did not provide data for all the outcomes specified in the protocol. For these reasons most of the analyses were underpowered and this limits the overall completeness of evidence. In general, based on the results of the current review, the possible role of antidepressants and benzodiazepines should be assessed by the clinician on an individual basis. The choice of which antidepressant and/or benzodiazepine is prescribed can not be made on the basis of this review only, and should be based on evidence of antidepressants and benzodiazepines efficacy and tolerability, including data from placebo‐controlled studies, as a whole. Data on long‐term tolerability issues associated with antidepressants and benzodiazepines exposure should also be carefully considered.

The present review highlights the need for further higher‐quality studies comparing antidepressants with benzodiazepines, which should be conducted with high‐methodological standards and including pragmatic outcome measures to provide clinicians with useful and practical data. Data from the present review will be included in a network meta‐analysis of psychopharmacological treatment in panic disorder, which will hopefully provide further useful information on this issue.

Plain language summary

Antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults

Why is this review important?

Panic disorder is common in the general population. It is characterised by panic attacks, periods of fear or anxiety with a rapid onset in which other symptoms are experienced (involving bodily feelings and fearful thoughts). The treatment of panic disorder includes talking therapy and medicines, often used in combination. The most commonly prescribed medicines are antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Evidence for their efficacy in comparison is unclear. It is important to find out if antidepressants and benzodiazepines are effective and acceptable in the treatment of panic disorder.

Who will be interested in this review?

Patients and practitioners.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review aims to answer the following questions.

What is the efficacy of antidepressants and benzodiazepines compared to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines?

What is the acceptability of antidepressants and benzodiazepines compared to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines?

How many adverse effects do antidepressants and benzodiazepines have compared to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines?

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched electronic databases to find all relevant studies conducted up to September 2015. To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials that compared treatments with antidepressants and benzodiazepines in adults with a diagnosis of panic disorder. We included 35 studies involving a total of 5365 participants in the review.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

We did not find substantial differences between antidepressants and benzodiazepines in terms of efficacy and tolerability. There was not enough information to compare any differences in adverse effects. However, our findings are limited in the following ways: few studies contributed to each analysis, some studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies, and only short‐term outcomes were assessed. The quality of the available evidence was mainly low, meaning that further research would be very likely to have an important impact on these results.

What should happen next?

Studies with larger sample sizes and fewer risks of bias should be carried out, with head‐to‐head comparisons. Longer‐term outcomes need to be addressed to establish whether the effect is transient or durable. Trials should better report any harms experienced by participants during the trial. In addition, a network meta‐analysis of psychopharmacological treatment in panic disorder will likely shed further light on this compelling issue, also being able to provide more information with regard to comparative efficacy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antidepressants compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder.

| Antidepressants compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: Antidepressants Comparison: benzodiazepines | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Benzodiazepines | Antidepressants | |||||

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 8‐10 weeks | 314 per 1000 | 310 per 1000 (210 to 461) | RR 0.99 (0.67 to 1.47) | 215 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | 213 per 1000 | 350 per 1000 (220 to 561) | RR 1.64 (1.03 to 2.63) | 1449 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 8‐10 weeks | 360 per 1000 | 425 per 1000 (364 to 493) | RR 1.18 (1.01 to 1.37) | 1002 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | The mean panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.13 lower (0.72 to 0.47 lower) | 1144 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5 | |||

|

panic symptoms ‐mean change Follow‐up: 8 weeks |

The mean panic symptoms ‐ mean change in the intervention groups was 0.40 higher (0.83 lower to 1.63 higher) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |||

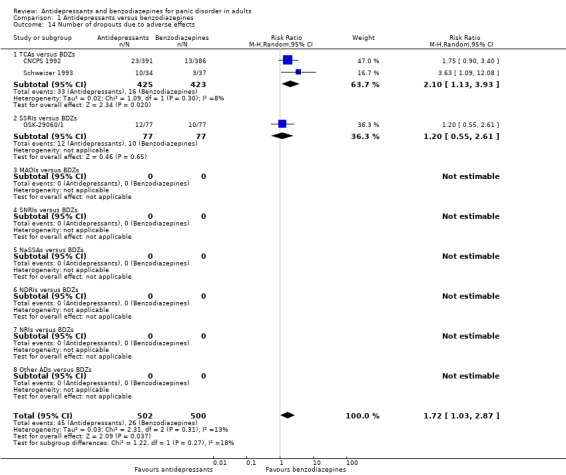

| number of dropouts due to adverse effects Follow‐up: 8‐10 weeks | 52 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (54 to 149) | RR 1.72 (1.03 to 2.87) | 1002 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (30%)

2 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI interval ranges from possible benefit with antidepressants to possible benefit with benzodiazepines

3 Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 75%)

4 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI interval ranges from no difference to possible benefit associated with benzodiazepines

5 Downgraded two points due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 95%) 6 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low (44) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to appreciable benefit with benzodiazepines

Summary of findings 2. TCAs compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder.

| TCAs compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: TCAs Comparison: benzodiazepines | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Benzodiazepines | TCAs | |||||

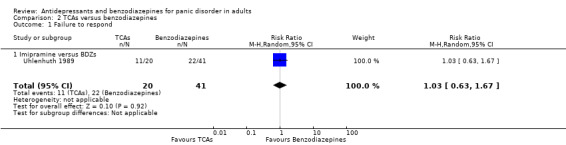

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 537 per 1000 | 547 per 1000 (338 to 896) | RR 1.02 (0.63 to 1.67) | 61 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

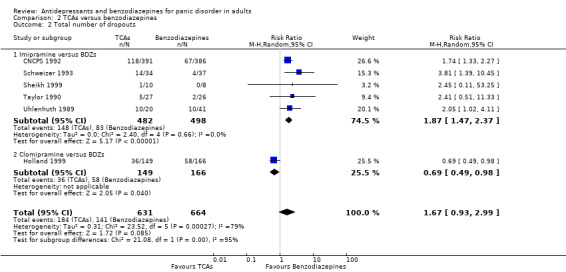

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | 212 per 1000 | 355 per 1000 (197 to 635) | RR 1.67 (0.93 to 2.99) | 1295 (6 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3,4 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 348 per 1000 | 414 per 1000 (348 to 490) | RR 1.19 (1 to 1.41) | 848 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | The mean panic symptoms ‐ endpoint score in the intervention groups was 0.25 lower (1.72 lower to 1.22 higher) | 998 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,5,6 | |||

|

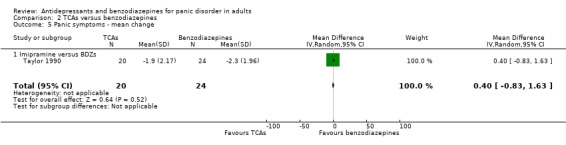

panic symptoms ‐ mean change Follow‐up: 8 weeks |

The mean panic symptoms ‐ mean change in the intervention groups was 0.40 higher (0.83 lower to 1.63 higher) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7 | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse effects Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 38 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (43 to 149) | RR 2.10 (1.13 to 3.93) | 848 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (around 30%) 2 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low (61) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to appreciable benefit with benzodiazepines

3 Downgraded two points due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 79%)

4 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from no difference to appreciable superiority of benzodiazepines in lowering the number of dropouts

5 Downgraded two points due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) 6 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI is very wide and ranges from benefit with TCAs and benefit with benzodiazepines 7 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low (44) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to appreciable benefit with benzodiazepines

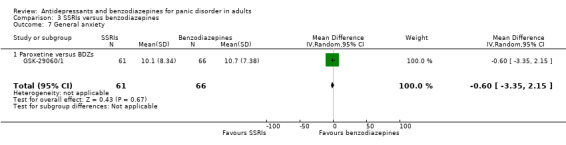

Summary of findings 3. SSRIs compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder.

| SSRIs compared to benzodiazepines for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: SSRI Comparison: benzodiazepines | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Benzodiazepines | SSRI | |||||

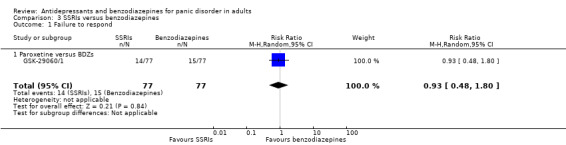

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 10 weeks | 195 per 1000 | 181 per 1000 (94 to 351) | RR 0.93 (0.48 to 1.80) | 154 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

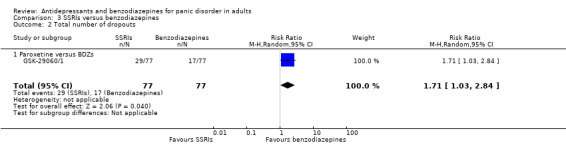

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 10 | 221 per 1000 | 378 per 1000 (227 to 627) | RR 1.71 (1.03 to 2.84) | 154 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 10 weeks | 429 per 1000 | 480 per 1000 (339 to 681) | RR 1.12 (0.79 to 1.59) | 154 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

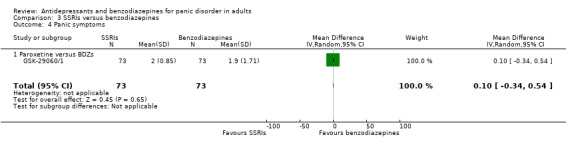

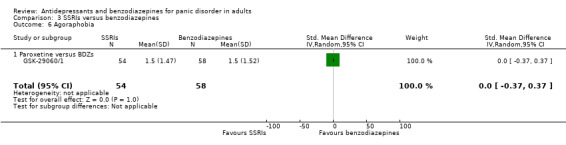

| panic symptoms | The mean panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.10 higher (0.34 lower to 0.54 higher) | 146 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse effects Follow‐up: 10 weeks | 130 per 1000 | 156 per 1000 (71 to 339) | RR 1.20 (0.55 to 2.61) | 154 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to high dropout rates (30%) 2 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low (= 154) and 95% CI is wide, including benefit with SSRIs and benefit with benzodiazepines; only one study provides data 3 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low (= 154) and 95% CI ranges from no difference to appreciable superiority of with benzodiazepines in lowering the number of dropouts; only one study provides data 4 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is low

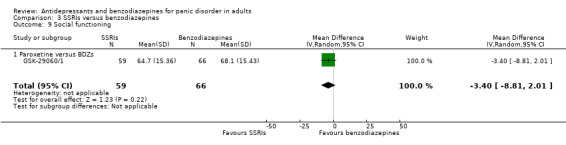

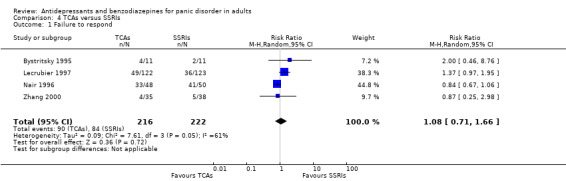

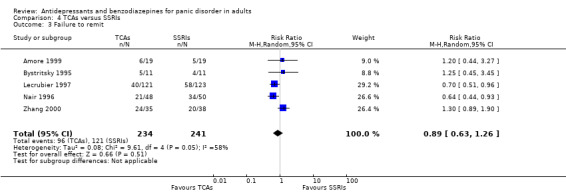

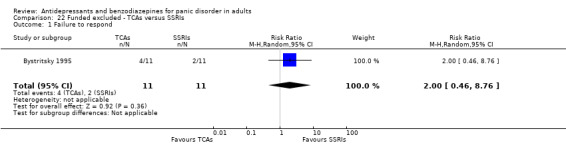

Summary of findings 4. TCAs compared to SSRI for adults with panic disorder.

| TCAs compared to SSRI for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: TCA Comparison: SSRI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SSRI | TCA | |||||

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 8‐12 weeks | 378 per 1000 | 409 per 1000 (269 to 628) | RR 1.08 (0.71 to 1.66) | 438 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | 243 per 1000 | 238 per 1000 (158 to 359) | RR 0.98 (0.65 to 1.48) | 928 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | 502 per 1000 | 447 per 1000 (316 to 633) | RR 0.89 (0.63 to 1.26) | 475 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

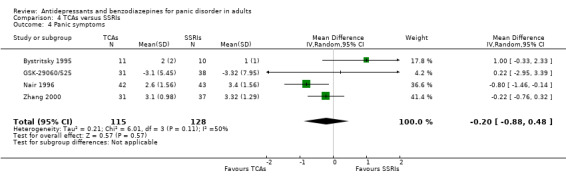

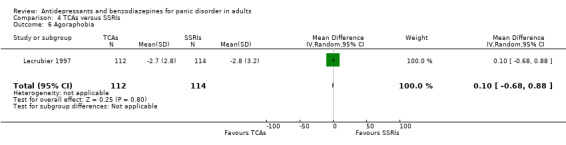

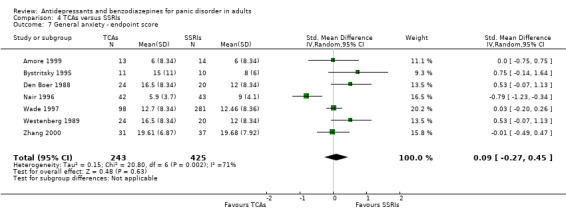

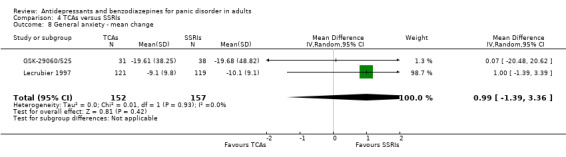

| panic symptoms Follow‐up: 8‐10 weeks | The mean panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.20 lower (0.88 lower to 0.48 higher) | 243 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6,7 | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse effects Follow‐up: 8‐24 weeks | 104 per 1000 | 148 per 1000 (85 to 257) | RR 1.43 (0.82 to 2.48) | 476 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,8 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to moderate heterogeneity (I squared = 61%) 2 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to appreciable benefit with SSRIs 3 Downgraded one point due to moderate heterogeneity (I squared = 47%) 4 Downgraded one point due to moderate heterogeneity (I squared = 58%) 5 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: dropout rate in one of the included studies (Nair 1996) is 48% 6 Downgraded one point due to moderate heterogeneity (I squared = 46%) 7 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to no difference 8 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from no difference to appreciable superiority of SSRIs in lowering the number of dropouts

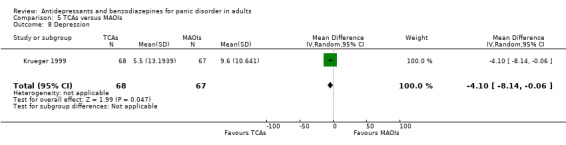

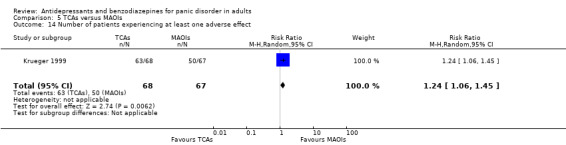

Summary of findings 5. TCA compared to MAOI for adults with panic disorder.

| TCA compared to MAOI for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: TCA Comparison: MAOI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| MAOI | TCA | |||||

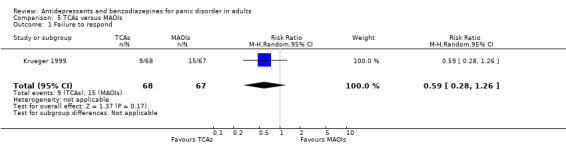

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 224 per 1000 | 132 per 1000 (63 to 282) | RR 0.59 (0.28 to 1.26) | 135 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

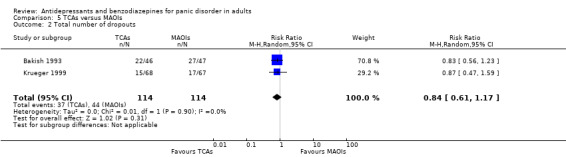

| total number of dropouts | 386 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (235 to 452) | RR 0.84 (0.61 to 1.17) | 228 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| failure to remit | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies provided data for this outcome |

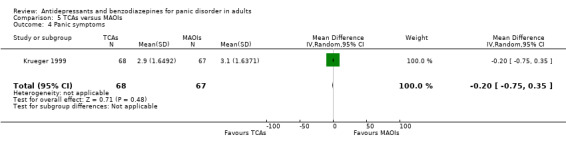

| panic symptoms Follow‐up: 8 weeks | The mean panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.20 lower (0.75 lower to 0.35 higher) | 135 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse events Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 104 per 1000 | 133 per 1000 (52 to 335) | RR 1.27 (0.5 to 3.21) | 135 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the study is low (= 135) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to no difference; only one study provides data 2 Downgraded one point due high dropout rates 3 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the study is low (= 135) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to no difference; only one study provides data. 4 Downgrded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the study is low (= 135) and 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with TCAs to appreciable benefit with MAOIs; only one study provides data.

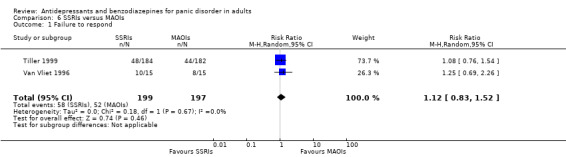

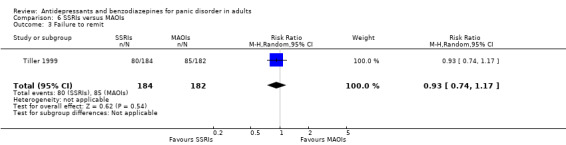

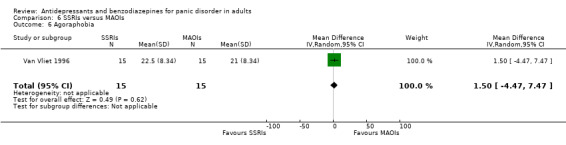

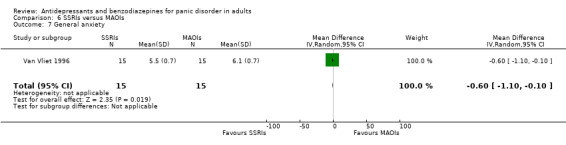

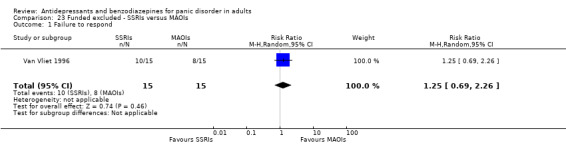

Summary of findings 6. SSRIs compared to MAOIs for adults with panic disorder.

| SSRIs compared to MAOIs for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: SSRI Comparison: MAOI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| MAOI | SSRI | |||||

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 8‐12 weeks | 264 per 1000 | 296 per 1000 (219 to 401) | RR 1.12 (0.83 to 1.52) | 396 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 12 weeks | 67 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (5 to 970) | RR 1.00 (0.07 to 14.55) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 467 per 1000 | 434 per 1000 (346 to 546) | RR 0.93 (0.74 to 1.17) | 366 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| panic symptoms | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies provided data for this outcome |

| number of dropouts due to adverse events Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 60 per 1000 | 76 per 1000 (36 to 163) | RR 1.26 (0.59 to 2.70) | 366 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from no difference to appreciable benefit with MAOIs 2 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is very low (= 30) and 95% CI is very wide, ranging from appreciable benefit with SSRIs to appreciable benefit with MAOIs; only one study provides data 3 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: even though the number of individuals included in the analysis is not low, only one study provides data 4 Downgrded two points due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with SSRIs to appreciable benefit with MAOIs; only one study provides data.

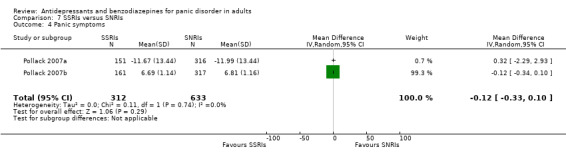

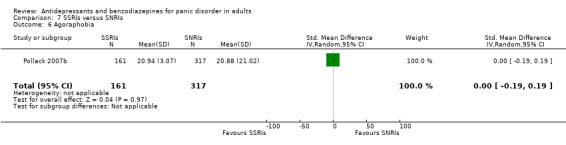

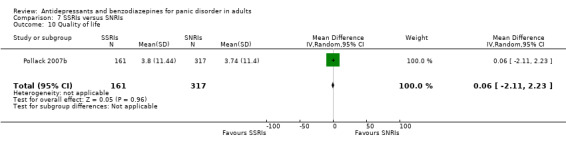

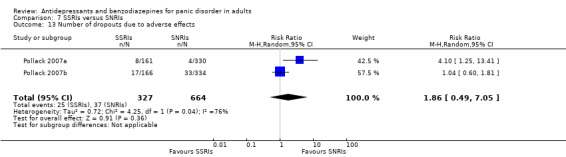

Summary of findings 7. SSRIs compared to SNRIs for adults with panic disorder.

| SSRIs compared to SNRIs for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: SSRI Comparison: SNRI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SNRI | SSRI | |||||

| failure to respond Follow‐up: 12 weeks | 232 per 1000 | 223 per 1000 (174 to 285) | RR 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23) | 991 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 2 weeks | 181 per 1000 | 201 per 1000 (134 to 298) | RR 1.11 (0.74 to 1.65) | 991 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| failure to remit Follow‐up: 12 weeks | 577 per 1000 | 606 per 1000 (525 to 698) | RR 1.05 (0.91 to 1.21) | 991 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| panic symptoms Follow‐up: 12 weeks | The mean panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.12 lower (0.33 lower to 0.10 higher) | 945 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse effects | 56 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (27 to 393) | RR 1.86 (0.49 to 7.05) | 991 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one point due to moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 53%) 2 Downgraded one point due to imprecision: 95% CI ranges from appreciable benefit with SSRIs to appreciable benefit with SNRIs 3 Downgraded one point due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 76%) 4 Downgraded one point due to serious imprecision: 95% CI ranges from no difference to benefit with SNRIs

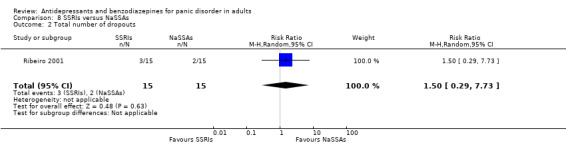

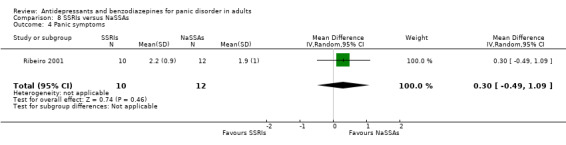

Summary of findings 8. SSRIs compared to NaSSAs for adults with panic disorder.

| SSRIs compared to NaSSAs for adults with panic disorder | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with panic disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: SSRI Comparison: NaSSA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| NaSSA | SSRI | |||||

| failure to respond | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | |

| total number of dropouts Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 133 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (39 to 1000) | RR 1.50 (0.29 to 7.73) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| failure to remit | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies provided data for this outcome |

| panic symptoms Follow‐up: 8 weeks | The mean panic symptoms in the intervention groups was 0.30 higher (0.49 lower to 1.09 higher) | 22 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | |||

| number of dropouts due to adverse events Follow‐up: 8 weeks | 133 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 (39 to 1000) | RR 1.50 (0.29 to 7.73) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is very low (= 30) and 95% CI is very wide, ranging from appreciable benefit with SSRIs to appreciable benefit with NaSSAs; only one study provides data 2 Downgraded two points due to imprecision: number of individuals included in the trial is very low (= 22) and 95% CI is very wide, ranging from appreciable benefit with SSRIs to appreciable benefit with NaSSAs; only one study provides data

Background

Description of the condition

A panic attack is a discrete period of fear or anxiety that has a rapid onset, reaches a peak within 10 minutes and in which at least four of 13 characteristic symptoms are experienced. Many of these symptoms involve bodily systems, such as racing heart, chest pain, sweating, shaking, dizziness, flushing, stomach churning, faintness and breathlessness. Further recognised panic attack symptoms involve fearful cognitions, such as the fear of collapse, going mad or dying, and derealisation (APA 1994).

Panic disorder first entered diagnostic classification systems in 1980 with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM‐III) (APA 1980), following observations that patients with panic attacks responded to treatment with the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), imipramine (Klein 1964). To diagnose panic disorder, further conditions must be met relating to the frequency of attacks, the need for some panic attacks to come on ‘out of the blue’ rather than in a predictable, externally‐triggered situation, and exclusions where attacks are attributable solely to medical causes or panic‐inducing substances, notably caffeine. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) also requires that at least one panic attack has been followed by one of the following:

persistent concern about having additional attacks;

worry about the implications of the attack or its consequences;

a significant change in behaviour related to the attacks (APA 1994).

The core features of panic attacks remained unchanged in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5) (APA 2013a), but in DSM‐5 panic disorder and agoraphobia are no longer linked and are now coded in two diagnoses (APA 2013b).

Panic disorder is common in the general population with a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 4% (Bijl 1998; Eaton 1994). In primary care settings, panic syndromes have been reported to have a prevalence of around 10% (King 2008). Its aetiology is not fully understood and is probably heterogeneous. Biological theories incorporate the faulty triggering of an inbuilt anxiety response. Evidence for this comes from biological challenge tests (lactate and carbon dioxide trigger panic in those with the disorder) and from animal experiments and neuroimaging studies in humans that show activation of fear circuits, such as those involving the periaqueductal grey matter (Gorman 2000).

Agoraphobia is anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having a panic attack (APA 1994) . About one‐fourth of people suffering from panic disorder also have agoraphobia (Kessler 2006). The presence of agoraphobia is associated with increased severity and worse outcome (Kessler 2006). There are several risk factors that predict the development of agoraphobia in people suffering from panic disorder: female gender, more severe dizziness during panic attacks, cognitive factors, dependent personality traits and social anxiety disorder (Starcevic 2009).

Panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, is highly co‐morbid with other psychiatric disorders, such as drug dependence, major depression, bipolar I disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and generalised anxiety disorder (Grant 2006). It is estimated that generalised anxiety disorder co‐occurs in 68% of people with panic disorder, whilst major depression has a prevalence of 24% to 88% among people with panic disorder (Starcevic 2009).

Description of the intervention

The treatment of panic disorder includes psychological and pharmacological interventions, often used in combination (Furukawa 2007). Historically, pharmacological interventions for panic disorder have been based on the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and TCAs (Bruce 2003). However, MAOIs and TCAs are associated with severe adverse effects, such as the risk of hypertensive crisis for MAOIs, and anticholinergic, arrhythmogenic and overall poor tolerability for TCAs (Wade 1999). Recent guidelines by the American Psychiatric Association (APA 2009), British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP 2005), and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (NICE 2011) recommend antidepressants, mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as the first‐line treatment for panic disorder, due to their more favourable adverse effect profile over MAOIs and TCAs. A meta‐analysis of 43 studies (randomised and non randomised) comparing SSRIs and TCAs in panic disorder showed that SSRIs were as effective as TCAs, and were better tolerated (Bakker 2002), although other studies showed a possible overestimation of the efficacy of SSRIs over older antidepressants in panic disorder, finding no difference in their efficacy (Otto 2001, effect‐size analysis of 12 placebo‐controlled, efficacy trials of SSRIs for panic disorder). It appears that TCAs can still have a role in the treatment of panic disorder.

Benzodiazepines, particularly high‐potency ones, have also been used in panic disorder (Stein 2010). Benzodiazepines have a higher incidence of dependence and withdrawal reaction when compared to antidepressants (Wade 1999). Moreover, benzodiazepines alone may not be effective in treating panic disorder co‐morbid with depression (Ballenger 1998), and have less favourable long‐term outcomes (NICE 2011). In spite of these caveats, it appears that benzodiazepines continue to be widely prescribed for the treatment of panic disorder (Bruce 2003).

How the intervention might work

The main classes with evidence of efficacy in panic disorder are antidepressant drugs that augment the function of the monoamines serotonin and/or noradrenaline. With regard to the serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline and citalopram), these drugs promote the transmission of the neurotransmitter serotonin across brain synapses; most notably in the dorsal raphe nucleus (Briley 1993). They prevent reuptake of serotonin into nerve terminals by inhibiting serotonin transporters, thus allowing more to be available for neurotransmission. In panic disorder, imaging studies have showed reduced expression of the 5H1A receptor (Nash 2008), which has an inhibitory function, so the increased serotonin throughput may in part serve to overcome this deficit of inhibition. Noradrenergic antidepressants can similarly increase transmission of the catecholamine noradrenaline. Some antidepressants such as the serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g. venlafaxine, duloxetine) and TCAs can enhance both serotonin and noradrenaline transmission by inhibiting both transporters.

Benzodiazepines moderate the gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system, which is the brain's main inhibitory neurotransmitter. They act as agonists at the GABA‐A benzodiazepines receptor. This complex contains a chloride channel which can be opened by agonists and ultimately produces an anxiolytic effect and sedation. It is known through imaging studies that the inhibitory GABA system is deficient in panic disorder (Malizia 1998; Cameron 2007), and thus the ability of benzodiazepines to act as agonists at the GABA‐A benzodiazepine receptor can counteract this. It is likely that both monoamine‐based systems and GABA‐based systems converge allowing both antidepressants and benzodiazepines to have efficacy in panic disorder despite their differing actions on neurotransmitter systems. One possibility is via serotonergic neurons that modulate GABA input to the periaqueductal grey matter.

Why it is important to do this review

Antidepressants and benzodiazepines are widely used in panic disorder. Published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown some evidence of efficacy. However, no systematic review that includes comparisons between antidepressants and benzodiazepines in panic disorder has been conducted recently, to our knowledge. A meta‐analysis published in 2007 focused on combined psychotherapy and antidepressants in panic disorder (Furukawa 2007), and a more recent systematic review focused on psychological treatments only (Sanchez‐Meca 2010). One meta‐analysis of interventions for panic disorder has been published in recent years, focusing on combined psychotherapy and benzodiazepines in panic disorder (Watanabe 2009). Furukawa 2007 concluded that either combined psychotherapy or psychotherapy alone may be chosen as first‐line treatment for panic disorder. Sanchez‐Meca 2010 reported that exposure, relaxation training and breathing retraining have the most robust evidence. A network meta‐analysis was also performed to compare different psychological therapies for panic disorder (Pompoli 2016). To our knowledge, the most recent meta‐analysis specifically focused on antidepressants in panic disorder was published in 2002 (Bakker 2002), and included 43 studies comparing SSRIs and TCAs. The authors concluded that SSRIs and TCAs were of equal efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder, with a better tolerability profile for SSRIs. Benzodiazepines are widely used in panic disorder. Available RCTs have shown some evidence of efficacy (Batelaan 2012). The last meta‐analysis specifically focused on benzodiazepines in panic disorder was published in 1991 (Wilkinson 1991), and included 19 double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials. This meta‐analysis compared antidepressants and benzodiazepines with placebo. The authors concluded that active treatment had a 25% greater success rate than placebo over 14 weeks. Another meta‐analysis has been recently published (Offidani 2013), including 22 studies comparing benzodiazepines and antidepressants in various anxiety disorders including panic disorder. The authors found that benzodiazepines were more effective in reducing the number of panic attacks, than TCAs. Additionally, benzodiazepines were better tolerated than TCAs and they were as effective as the newer antidepressants. The authors concluded that the role of benzodiazepines should be reappraised. The review mostly focused on tricyclic antidepressants and did not include studies comparing benzodiazepines with SSRIs.

An up‐to‐date systematic review is needed to help practitioners identify the relative efficacy of antidepressants and benzodiazepines, compared to each other, in order to be better guided in the choice of the pharmacological agent.

Two other Cochrane reviews in patients with panic disorder, one on antidepressants versus placebo and one on benzodiazepines versus placebo, respectively, are in progress, which will be of further help to identify effective treatments in panic disorder (Guaiana 2013a; Guaiana 2013b). A Cochrane network meta‐analysis of psychopharmacological treatment in panic disorder is in progress (Guaiana 2014).

This review followed the methods set out in the protocol (Guaiana 2015)

Objectives

To assess the effects of antidepressants or benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults, specifically:

to determine the efficacy of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in alleviating symptoms of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines;

to review the acceptability of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, in comparison to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines; and

to investigate the adverse effects of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, including the general prevalence of adverse effects, compared to other antidepressants and other benzodiazepines.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Double‐blind randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using a parallel‐group design that compare antidepressants as monotherapy with benzodiazepines as monotherapy, antidepressants with antidepressants and benzodiazepines with benzodiazepines. We included one cross‐over trial, and RCTs with more than two arms. Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion but none were identified.

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those allocated by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

Participants

Participants aged 18 years or older.

Diagnosis

Patient with primary diagnosis of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia, diagnosed according to any of the following criteria: Feighner criteria, Research Diagnostic Criteria, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐III, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV, DSM‐V) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD‐10). In cases where study eligibility focused on agoraphobia, rather than panic disorder, we included studies if operationally diagnosed according to the above‐named criteria and when it was possible to safely assume that some of the participants were suffering from panic disorder as defined by the above criteria. In other words, we excluded studies that focused on agoraphobia without panic disorder. There is evidence that over 95% of patients with agoraphobia seen clinically suffer from panic disorder as well (Goisman 1995). However, we planned to further examine the effects of the inclusion of these studies (i.e. studies in which some, but possibly not all, of the patients had panic disorder) in a sensitivity analysis (Sensitivity analysis).

Co‐morbidities

We excluded participants with serious co‐morbid physical disorders (e.g. myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, uncontrolled diabetes, electrolyte disturbances) as they may confound treatment effectiveness and tolerability. Studies where panic is induced were excluded. We included participants with co‐morbid mental disorders, but the effect of including these participants was examined in sensitivity analyses (Sensitivity analysis).

Settings

We included all types of settings (inpatient, outpatient, primary care). We included only studies recruiting patients acutely ill. Long‐term, relapse prevention studies were therefore excluded.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing antidepressants as monotherapy with benzodiazepines as monotherapy, antidepressants with antidepressants, and benzodiazepines with benzodiazepines in the treatment of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia.

We included only acute treatment studies treating participants for less than six months. If a study treated participants for more than six months but reported outcome data within six months, we included the data.

We included the following antidepressants as classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical, Therapeutic and Chemical (ATC) classification system and the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) (WHO ATC/DDD) system (WHO 2003).

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, amoxapine, clomipramine, desipramine, dosulepin/dothiepin, doxepin, imipramine, iofepramine, maprotiline, nortriptyline, protriptyline , trimipramine, any other agent.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, citalopram, paroxetine, escitalopram, any other agent.

Monomine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs: phenelzine, isocarboxazide, tranylcypromine, moclobemide, brofaromine, any other agent.

Serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, any other agent.

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs): mirtazapine, any other agent

Noradrenergic and dopaminergic reuptake inhibitors: bupropion, any other agent.

Noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors: reboxetine, any other agent.

Others: agomelatine, trazodone, nefazodone, mianserin, maprotiline, any other agent classified as antidepressants according to the WHO ATC/DDD system of non‐conventional herbal products (e.g. Hypericum).

We included the following benzodiazepines: alprazolam, bretazenil, bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, cinolazepam, clonazepam, cloxazolam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, fludiazepam, flunitrazepam, flurazepam, flutoprazepam, halazepam, ketazolam, loprazolam, lorazepam, medazepam, nimatazepam, nitrazepam, nodazepam, oxazepam, phenazepam, pinazepam, prazepam, premazepam, quazepam, temazepam, tetrazepam, triazolam.

We excluded studies in which regular use of benzodiazepines was allowed in addition to the study medications; studies where irregular use of benzodiazepines was allowed were included, but the effect of including these participants was examined in sensitivity analyses (Sensitivity analysis). We applied no restrictions on dose, frequency, intensity or duration.

We also excluded studies administering psychosocial therapies targeted at panic disorder delivered concurrently with medication.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Failure to respond, i.e. lacking of substantial improvement from baseline as defined by the original investigators. Examples of improvement would be “very much or much improved” according to the Clinical Global Impressions Scale, more than 40% reduction in the Panic Disorder Severity Scale score (which is considered as equivalent to "very much or much improved" on the Clinical Global Impression of Improvement Scale (Furukawa 2009), and more than 50% reduction in the Fear Questionnaire Agoraphobia Subscale (which is considered as an appropriate rate of response according to Bandelow 2006). For this outcome we calculated the number of patients who fail to meet these improvement criteria.

Total number of dropouts for any reason as a proxy measure of treatment acceptability.

Secondary outcomes

Failure to remit, i.e. lacking of satisfactory end‐state as defined by global judgment of the original investigators. Examples of satisfactory end‐state would be "panic free" and "no or minimal symptoms" according to the Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale. For this outcome, we calculated the number of patients who failed to meet these remission criteria.

Panic symptom scales and global judgment on a continuous scale. Examples include Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) total score (0 to 28), Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale (CGI‐S) (1 to 7), and Clinical Global Impression Change Scale (1 to 7). When multiple measures are used, preference was given in the order as above, with preference given to panic symptom scales. The actual measure entered into meta‐analyses will be indicated at the top of the listings in the 'Characteristics of included studies' section

Frequency of panic attacks, as recorded, for example, by a panic diary

Agoraphobia, as measured, for example, by the Fear Questionnaire (FQ), Mobility Inventory, or behavioural avoidance test

General anxiety, as measured, for example, by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA), Beck Anxiety Inventory, State‐Trait Anxiety Index, Sheehan Patient‐Rated Anxiety Scale, or Anxiety Subscale of Symptom Checklist‐90‐Revised (SCL‐90‐R)

Depression, as measured, for example, by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), or Depression Subscale of SCL‐90‐R

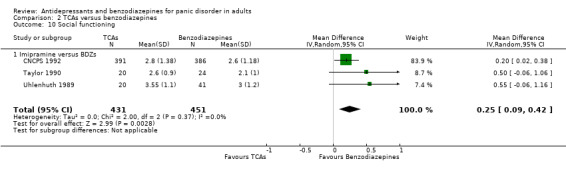

Social functioning, as measured, for example, by the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), Global Assessment Scale, or Social Adjustment Scale‐Self Report

Quality of life, as measured for example by the 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) or the 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐12)

Patient satisfaction with treatment

Economic costs

Number of dropouts due to adverse effects

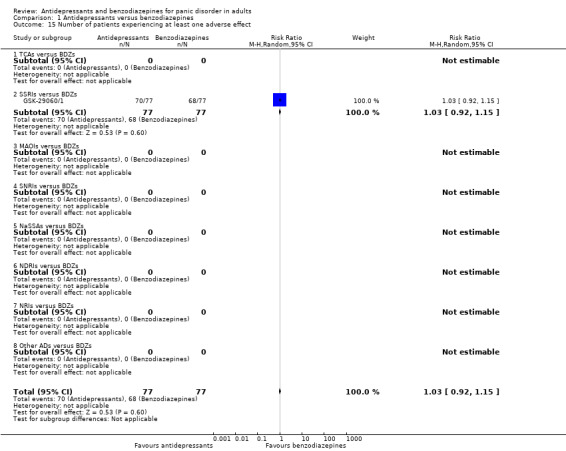

Number of patients experiencing at least one adverse effect

Timing of outcome assessment

All outcomes are short‐term outcomes, which we defined as acute phase treatment which normally would last two to six months.

When studies reported outcome data at different time points within two to six months, the time point closest to 12 weeks was given preference.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

When multiple measures were used, preference was given in the order listed above for each outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintains a specialised register of randomised controlled trials, the CCMDCTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies based register with >50% of reference records tagged to c12,500 individually PICO coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the hand‐searching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's web site with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's specialised register (CCMDCTR)

The Group's Information Specialist searched the CCMDCTR (Studies and References) register to 11 September 2015, using the following search strategy:

CCDANCTR‐Studies Diagnosis = panic

Records were screened for randomised‐controlled trials comparing antidepressants with benzodiazepines, antidepressants with antidepressants or benzodiazepine with benzodiazepine in this population.

CCDANCTR‐References A search of the references register (to identify additional untagged, uncoded reports of RCTs) included a comprehensive list of terms for panic, anxiety disorders not otherwise specified (ADNOS), antidepressants and benzodiazepines, (Appendix 2).

We screened all abstracts for 'antidepressants' as classified by the WHO ATC/DDD system as well as relevant benzodiazepine trials. We obtained full‐text articles, where necessary.

National and international trials registers

We conducted complementary searches on the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all included studies, non‐Cochrane systematic reviews and major textbooks of affective disorders (written in English), for published reports and citations of unpublished research. We also pursued a citation search via Web of Science (included studies only) to identify additional works. We also contacted experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (IB (clinical expertise), CT (methodological expertise)) independently selected studies for inclusion in this systematic review.

Review authors IB and CT inspected the search results by reading the titles and abstracts to see if they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was resolved by consultation with the other co‐authors. We obtained full‐text articles for the potentially relevant studies located in the search and both review authors independently assessed them for inclusion and, in the case of discordance, resolution was sought by discussion between all review authors. Where it was not be possible to evaluate the study because of language problems or missing information, we categorised the study as 'study awaiting classification' until a translation or further information could be obtained. We reported the reasons for the exclusion of trials in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

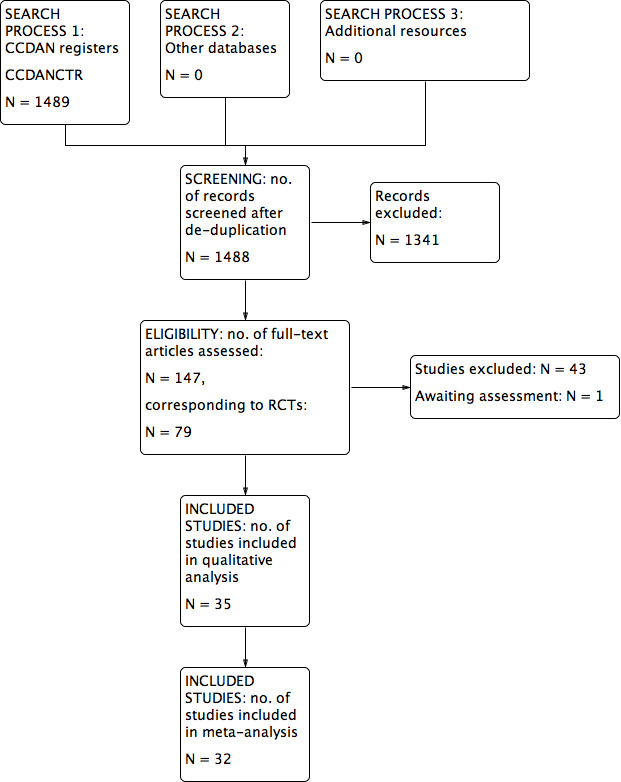

We documented and presented all decisions made during the selection process, with numbers of studies and references, in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher 2009) (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (IB and CT) used a standardised data extraction form to independently extract data from included studies concerning participant characteristics (age, sex, study setting), intervention details (dosage, duration of study, sponsorship), study characteristics (blinding, allocation etc) and outcome measures of interest. We first piloted this data extraction sheet on a sample of 10% of the included studies. Again, any disagreement was resolved by consensus or by consulting a third review author (CB). If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain clarification.

Our comparisons were as follows (Types of interventions):

A. antidepressants versus benzodiazepines;

B. antidepressants versus antidepressants;

C. individual benzodiazepines versus another benzodiazepine.

We stratified comparison A by class of antidepressant, as per the categories provided in Types of interventions. We also included comparisons of antidepressant classes versus benzodiazepines, to allow the presentation of data about individual antidepressants of each class versus benzodiazepines. For the second comparison, we made the decision to conduct separate comparisons for each class of antidepressant rather than stratify an overall comparison of antidepressant versus antidepressant according to class of drug. For the second comparison we also included individual antidepressants versus another antidepressant of the same class (see Differences between protocol and review.)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (IB and CT) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This tool encourages consideration of the following domains:

random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data reporting (attrition bias);

selective reporting (reporting bias);

other bias (within this domain we will consider things like sponsorship bias).

We assessed and categorised risk of bias, in each domain and overall, as follows:

low risk of bias, plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results;

high risk of bias, plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results;

unclear risk of bias, plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results.

In case of disagreement, the final rating was made by consensus, if needed with the involvement of a third author (CB). Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. Non‐concurrence in assessment of bias was also reported.

Measures of treatment effect

Our main outcome measure is reduction of severity of panic and agoraphobia symptoms. Symptomatic improvement was usually presented as a change in a panic disorder scale(s) (mean and standard deviation) or as a dichotomous outcome (responder or non‐responder, remitted or not‐remitted), or both.

Dichotomous data

For binary or dichotomous outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratios (RRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a random‐effects model. It has been shown that a random‐effects model has a good generalisability (Furukawa 2002), and that RRs are easier to understand than odds ratios (ORs) (Boissel 1999). Furthermore, ORs tend to be interpreted as RRs by clinicians (Deeks 2002). This may lead to an overestimation of the impression of the effect (Higgins 2011). For all primary outcomes, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) and their 95% CIs using Visual Rx (www.nntonline.net/), taking account of the event rate in the control group.

Continuous data

Summary statistics

We assumed a priori that the included studies used varied rating scales; therefore we used standardised mean differences (SMDs). If all included studies used the same measuring instrument, we used mean differences (MDs). We also calculated 95% CIs for each continuous measure.

Endpoint versus change data

Trials usually report results either using endpoint means and standard deviation of scales or using change in mean values from baseline of assessment rating scales. We prefer to use scale endpoint data, which typically cannot have negative values and are easier to interpret from a clinical point of view. If endpoint data were unavailable, we used the change data in separate analyses. In the case we used MDs, we pooled results based on change data and endpoint data in the same analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are trials in which all participants receive both the control and intervention treatment but in a different order. The major problem is a carry‐over effect from the first phase to the second phase of the study, especially if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As this is the case with panic disorder, we planned to include cross‐over studies, but to use only data up to the point of first cross‐over phase.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, when there were two appropriate dose groups of the same drug, we pooled different dose arms and considered them as one. If the arms involved one or more benzodiazepine arms and/or two or more arms of different classes of antidepressants, we planned to compare each arm separately. To avoid the of unit‐of‐analysis error by double counting the patients of the shared group (Higgins 2011), we planned to divide the shared group evenly among the treatment arms. In accordance to the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we divided events and number of patients for dichotomous outcomes, while only divided the number of patients for continuous outcomes.

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials, groups of individuals rather than individuals are randomised to different interventions. Had we identified cluster‐RCTs, we planned to use the generic inverse variance technique. We would have checked if such trials have been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients to adjust for cluster effects. If trialists have not adjusted for the effects of clustering, we would have attempted to do this by obtaining an intracluster correlation coefficient and then following the guidance given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We tried to contact the study authors for all relevant missing data.

Dichotomous outcomes

We calculated response, or remission on treatment, using an intention‐to‐treat analysis. We followed the principle of 'once randomised always analysed'. Where participants left the study before the intended endpoint, it was assumed that they would have experienced the negative outcome. The validity of the above assumption was planned to be tested by sensitivity analysis, applying worst and best case scenarios. When dichotomous outcomes were not reported, but the baseline mean and standard deviation on a panic disorder scale were reported, we calculated the number of responding or remitted participants according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2005). We analysed the validity of the above approach by sensitivity analysis (Sensitivity analysis). If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain data and/or clarification.

Continuous outcomes

Concerning continuous data, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions recommends avoiding imputation of continuous data and suggests using the data as presented by the original authors (Higgins 2011). Where intention‐to‐treat data were available, they have been preferred to 'per‐protocol analysis'. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies to obtain data and/or clarification.

Skewed or qualitative data

We planned to present skewed and qualitative data descriptively. We considered several strategies for skewed data. If papers reported a mean and standard deviation and there was also an absolute minimum possible value for the outcome, we planned to divide the mean by the standard deviation. If this was less than two then we concluded that there was some indication of skewness. If it was less than one (that is the standard deviation was bigger than the mean), then there was almost certainly skewness. If papers had not reported the skewness and simply reported means, standard deviations and sample sizes, these numbers were used. Because there was a possibility that these data might not have been properly analysed, and could also be misleading, they were descriptively reported in the results. If the data had been log‐transformed for analysis, and the geometric means were reported, skewness was reduced. This is the recommended method of analysis of skewed data (Higgins 2011). If studies used non‐parametric tests and described averages using medians, they could not be formally pooled in the analysis. We followed the recommendation made in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions that results of these studies should be reported in a table in our review, along with all other papers. This means that the data were not lost from the review and the results could be considered when drawing conclusions, even if they could not be formally pooled in the analyses.

Missing statistics

When only P or standard error values were reported, we calculated standard deviations (Altman 1996). In the absence of supplementary data after requests to the authors, we calculated the standard deviations according to a validated imputation method (Furukawa 2006). We examined the validity of these imputations in the sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic as per the guidance by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We interpreted the I² as follows:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

We also used the Chi² test and its P value to determine the direction and magnitude of the treatment effects. In a meta‐analysis of few trials, Chi² will be underpowered to detect heterogeneity, if it exists. A P value of <0.10 was used as a threshold of statistical significance for the ChI²² test. We also visually assessed the forest plots for evidence of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Higgins 2011). A funnel plot is usually used to investigate publication bias. However, it has a limited role when there are only few studies of similar size. Secondly, asymmetry of a funnel plot does not always reflect publication bias. We visually inspected funnel plots to assess publication bias as well as performed statistical test for funnel plot asymmetry as proposed by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not use funnel plots for outcomes if there were 10 or fewer studies included in the meta‐analysis in question, or if all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model to calculate the treatment effects. We preferred the random‐effects model as it takes into account differences between studies even when there is no evidence of statistical heterogeneity It gives a more conservative estimate than the fixed‐effect model. We noted that the random‐effects model gives added weight to small studies, which can either increase or decrease the effect size. We applied a fixed‐effect model, on primary outcomes only, to see whether it markedly changed the effect size.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses are often exploratory in nature and should be interpreted cautiously: firstly, because they often involve multiple analyses leading to false positive results; and secondly, these analyses lack power and are more likely to result in false positive results. Keeping in mind these reservations, and also taking into account the number of available studies, we planned to perform the following subgroup analyses:

participants with agoraphobia versus participants without agoraphobia (because the same treatment may have differential effectiveness with regard to panic and agoraphobia);

acute phase treatment studies that lasted for less than four months versus those that lasted for four months or more.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes only in order to examine if the results changed and check for the robustness of the observed findings.

Excluding trials with high risk of bias (i.e. trials with inadequate allocation concealment and blinding, with incomplete data reporting and/or with high probability of selective reporting).

Excluding trials with dropout rates greater than 20%.

Excluding studies funded by the pharmaceutical company marketing each antidepressant or benzodiazepine (This sensitivity analysis is particularly important in view of the repeated findings that funding strongly affects outcomes of research studies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Lexchin 2003; Bhandari 2004), and because industry sponsorship and authorship of clinical trial reports have increased over the last 20 years (Buchkowsky 2004)).

Excluding studies whose participants clearly have significant psychiatric co‐morbidities including primary or secondary depressive disorders.

Excluding studies mostly focused on agoraphobia.

Applying best and worst case scenarios to studies where participants left the study before the endpoint.

Excluding studies where responding or remitted participants are calculated according to an imputation method.

Excluding studies where irregular benzodiazepine use was allowed after the first 15 days after random allocation.

Summary of findings

We summarised the findings using a 'Summary of findings' table, applying the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Higgins 2011).

We included the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables:

response;

total number of dropouts;

remission;

panic symptom scales and global judgment on a continuous scale;

number of dropouts due to adverse effects.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The number of references identified by the searches (last update September 2015) was 1489, of which 1488 remained after de‐duplication. We excluded 1341 references after assessment of titles and abstracts. We retrieved 147 full‐text articles for full inspection, describing 79 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Of these, 43 studies were excluded, and one study was placed in the awaiting assessment group. Finally, 35 studies including 6785 participants, 5365 for the arms of interest (described in 84 reports) were included in the review. In case of missing information, we contacted authors of the included studies for additional information, and three of them responded (Drs. Bandelow, Lavori, and Stahl). See Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009) depicting the study selection process.

Included studies

Thirty‐five studies were included in this review, with characteristics as follows (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Design

Thirty‐four of the 35 included studies were parallel‐group, individually‐randomised controlled trials. One study (Sasson 1999) with a cross‐over design reported only aggregated results on the two active treatment phases (before and after cross‐over); therefore these data could not be included in the meta‐analysis.

Sample sizes

The sample sizes ranged between seven (Sheikh 1999) and 391 (CNCPS 1992) participants in each arm. Fifteen studies included overall sample sizes over 100: Bandelow 2004 (n = 225), CNCPS 1992 (n = 1168), GSK‐29060/1 (n = 226), Holland 1999 (n = 315), Krueger 1999 (n = 135), Lecrubier 1997 (n = 368), Nair 1996 (n = 148), Noyes 1996 (n = 238), Pfizer 2008 (n = 319), Pollack 2007a (n = 653), Pollack 2007b (n = 663), Schweizer 1993 (n = 106); Stahl 2003 (n = 380), Tiller 1999 (n = 366), Wade 1997 (n = 379).

Setting

A total of 19 trials enrolled only outpatients, one trial enrolled only inpatients, and both inpatients and outpatients were enrolled in three trials. For the remaining 12 trials the setting was unclear. Nine trials were conducted in the USA, four in the Netherlands, three in Italy, two in Canada, two in Brazil, two in China, one in UK, one in Finland, one in Japan, and one in Israel; seven trials were multinational, and two did not provide information about the country.

Participants

The proportion of women ranged from 36% to 92%. Mean age ranged from 30.5 to 61.6 years.

Interventions

Eighteen studies included two arms, while the remaining studies had three or more arms. Nine trials included a comparison between antidepressants and benzodiazepines, 22 between individual antidepressants (including four comparisons between antidepressants of the same class), and four trials between individual benzodiazepines. Fifteen studies had a placebo arm.

Duration of the intervention ranged from three to 24 weeks.

Outcomes

Seventeen studies reported data on response rates, while the number of dropout for any reason was reported in 28 studies. Fourteen studies reported on remission rates. Sixteen studies reported data on panic symptoms (using Panic and Anticipatory Anxiety Scale (PAAS), Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS), Clinical Global Impression Severity of Illness Score (CGI‐S)), 15 on frequency of panic attacks, 10 on agoraphobia (using Fear Questionnaire (FQ) and Marks‐Sheehan Phobia Scale), 26 on general anxiety (using Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAS) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA)), 17 on depression (using Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)). SIx studies reported data on social functioning (using Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)), three on quality of life. None of the studies reported on patient satisfaction and economic costs. Twenty‐one studies had data on dropouts due to adverse effects, and 11 on the number of patients experiencing at least one adverse effect.

Excluded studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies.

Sixty‐seven articles, initially selected (corresponding to 43 studies), did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded, for the following reasons: 19 had a wrong study design; four trials included patients who were not primarily diagnosed with panic disorder; five studies included participants with anxiety disorders in general, but the randomisation was not stratified by the presence of panic disorder; 15 studies had a wrong comparison group.

Ongoing studies

See: Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Our search identified no ongoing studies.

Studies awaiting classification

See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Only one study (Minutentag 2001) was classified as "awaiting classification".

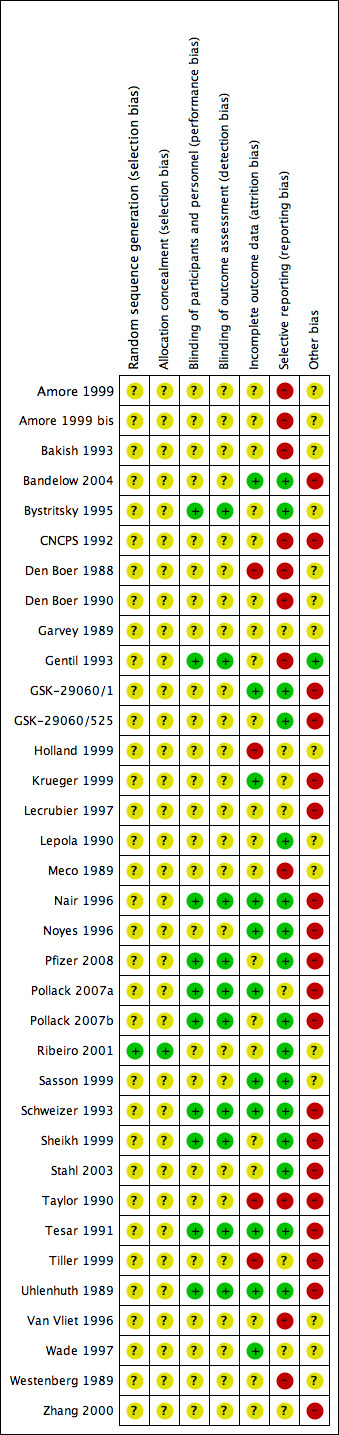

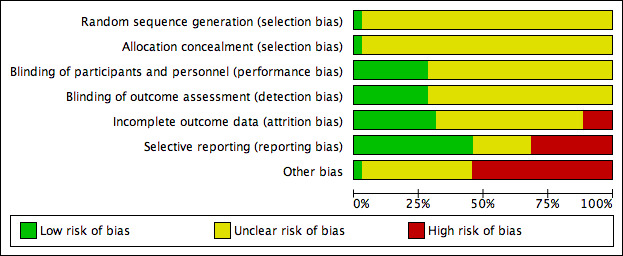

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of the 'Risk of bias' judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies. Graphical representations of the overall risk of bias in included studies are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Thirty‐four of the studies did not report the methods of random sequence generation; only one study (Ribeiro 2001) specified this information, and it was classified as "low risk".

Allocation concealment

Only one study (Ribeiro 2001) reported details on allocation concealment and was classified as "low risk".

Blinding

Twenty‐five RCTs were reported to be double‐blind, without providing any further detail; 10 RCTs reported details on strategies to ensure blinding of participants and key study personnel, and were classified as "low risk".

Incomplete outcome data

Eleven trials were rated as adequate in terms of addressing incomplete outcome data, while 20 studies were classified as "unclear risk" and four as "high risk".

Selective reporting

The study protocol was not available for almost all studies so it is difficult to make a judgment on the possibility of outcome reporting bias. However, in 16 studies results were consistent with the outcomes pre‐specified in the methods section, and they were evaluated as "low risk"; using the same criterion, 11 studies were judged to be at "high risk".

Other potential sources of bias

Nineteen of the included studies were funded by the pharmaceutical industry, and they did not report details on the role of the funder in planning, conducting and writing the study; for this reason they were rated as "high risk". Fifteen did not specify the source of funding. One study (Gentil 1993) was classified as "low risk".

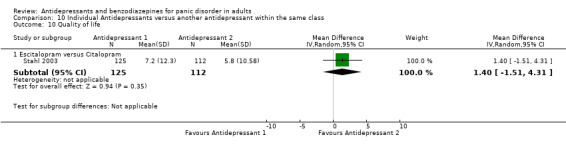

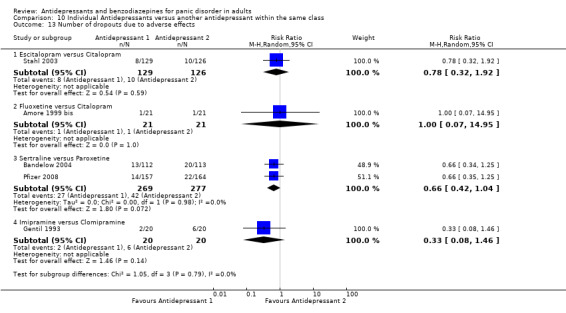

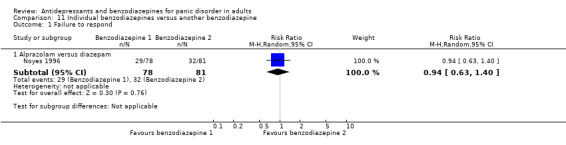

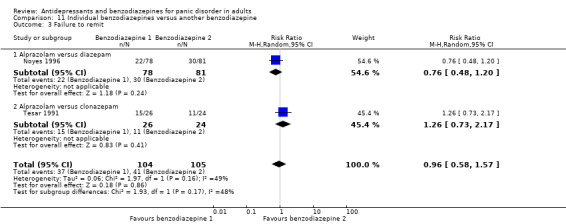

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8

A: Antidepressants versus benzodiazepines

We found data only for the comparisons reported below.

Comparison 1: Antidepressants versus benzodiazepines

Eight studies including 2055 participants (CNCPS 1992; GSK‐29060/1; Holland 1999; Lepola 1990; Schweizer 1993; Sheikh 1999; Taylor 1990; Uhlenhuth 1989) provided data for at least one outcome for this comparison. See also: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3.

Primary outcomes

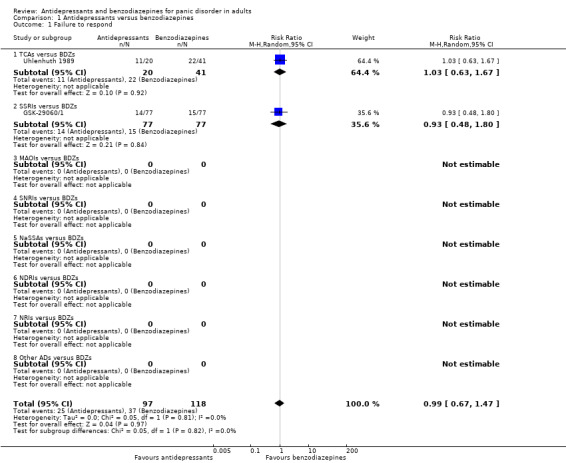

1.1 Failure to respond

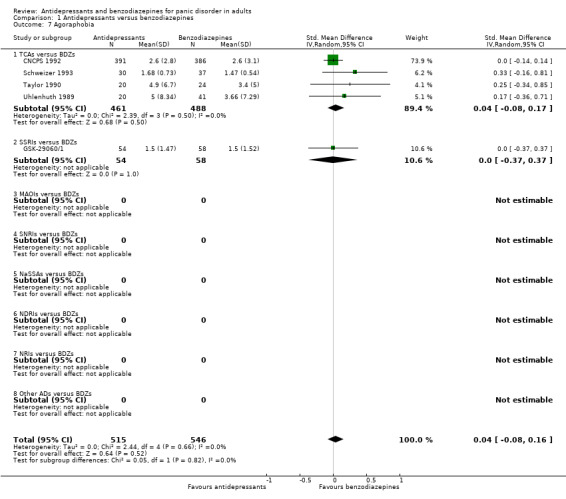

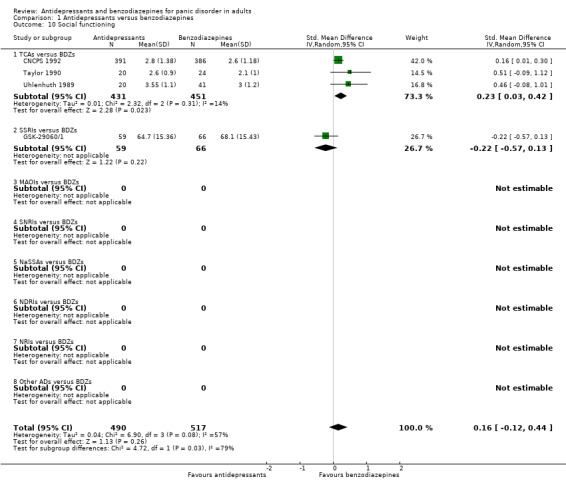

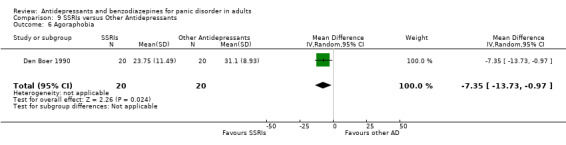

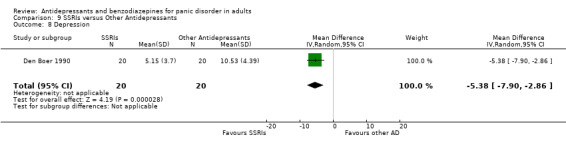

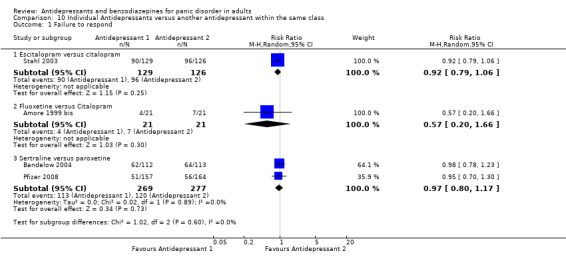

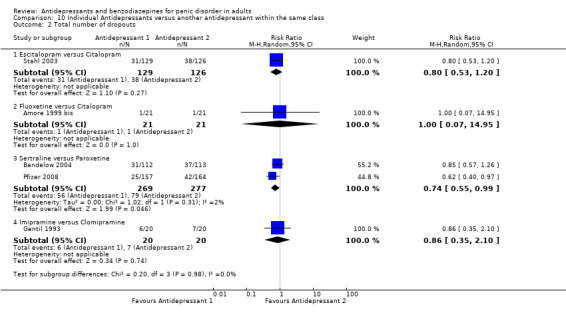

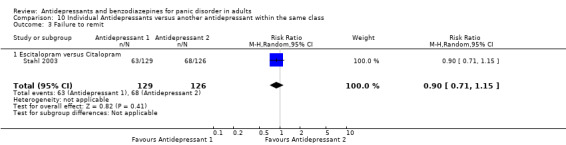

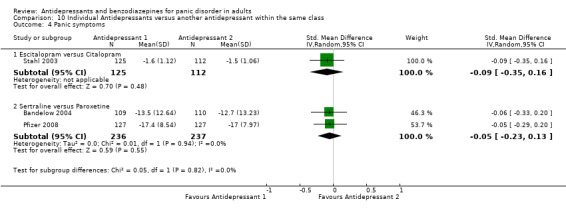

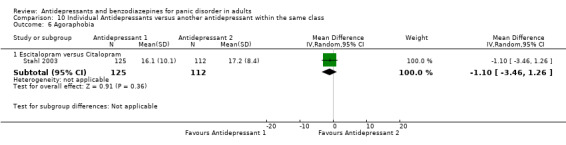

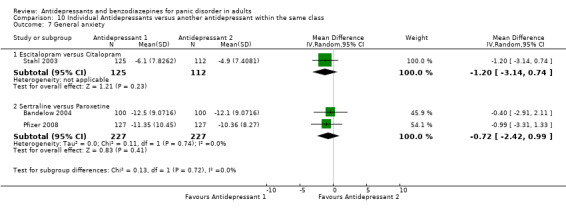

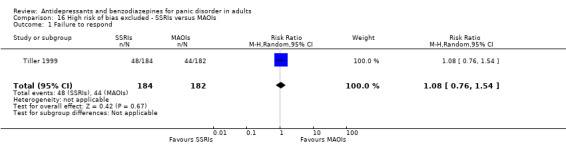

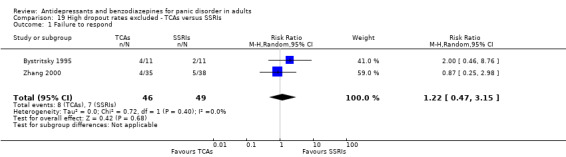

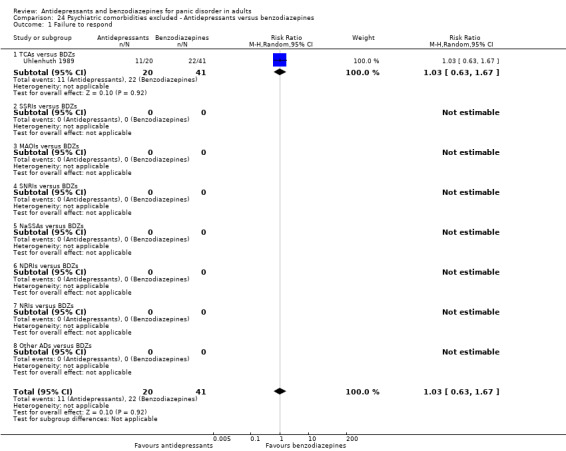

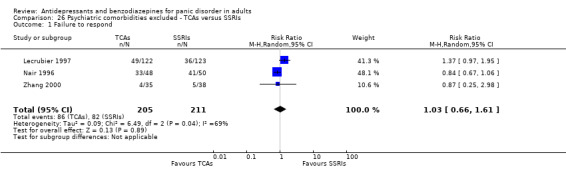

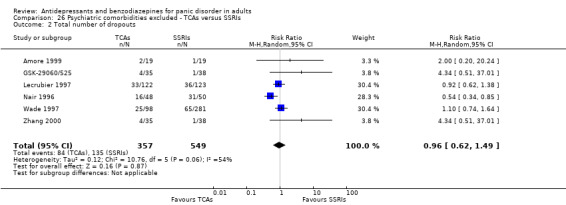

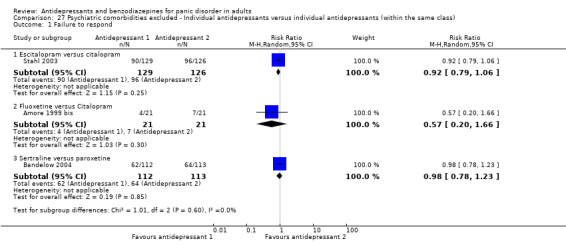

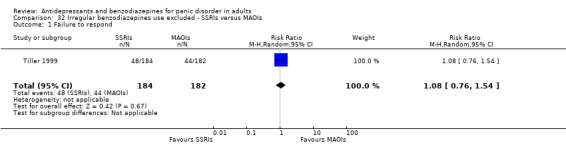

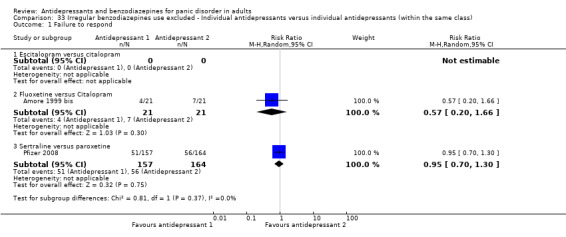

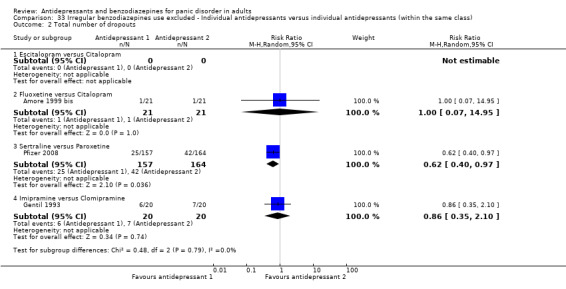

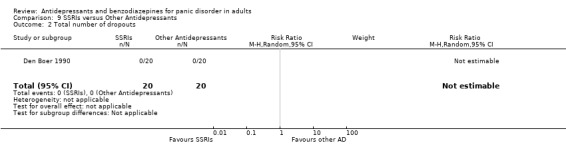

We found low‐quality evidence that cannot inform us as to whether there is a difference between antidepressants and benzodiazepines in terms of response rate. Confidence interval ranges from appreciable benefit with antidepressants to appreciable benefit with benzodiazepines (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67 to 1.47; participants = 215; studies = 2; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.1). There was consistency between study results. Risk of bias was considered unclear for this outcome. Additionally, the comparisons of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) versus benzodiazepines (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.67; participants = 61; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus benzodiazepines (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.80; participants = 154; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence) did not show any difference (Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antidepressants versus benzodiazepines, Outcome 1 Failure to respond.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antidepressants versus benzodiazepines, outcome: 1.1 Failure to respond.

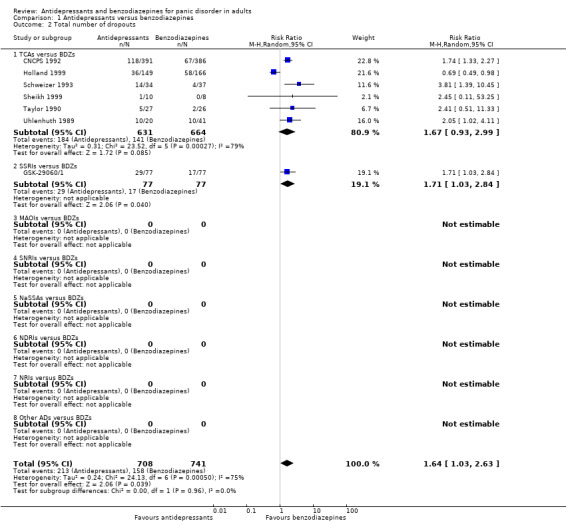

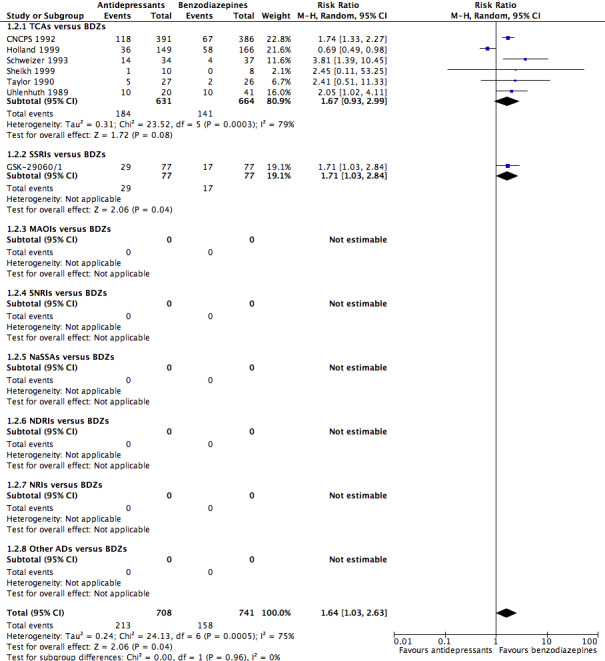

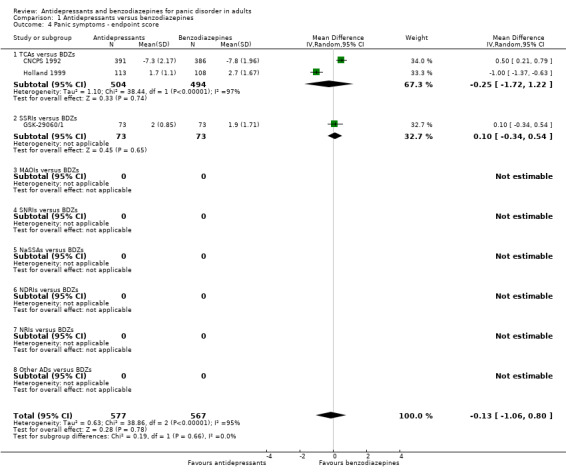

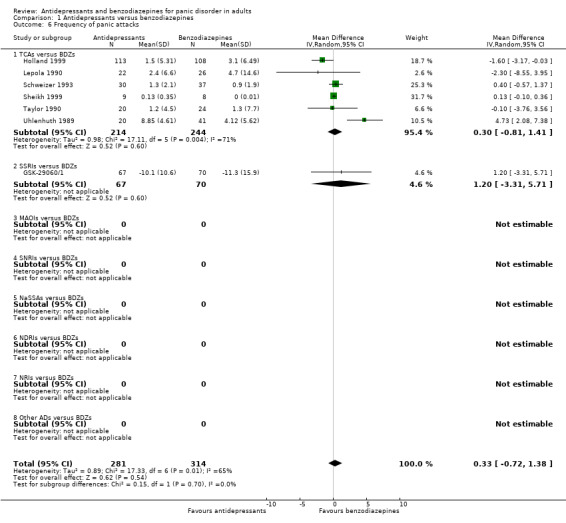

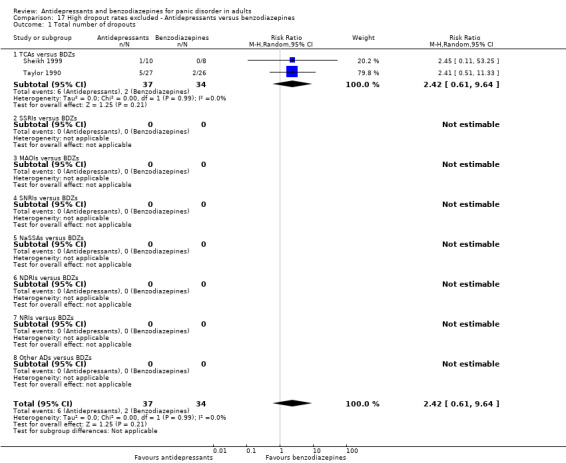

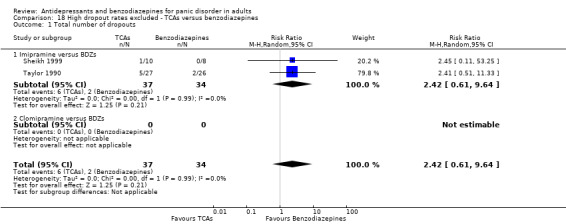

1.2 Total number of dropouts