Abstract

Background

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) with dialysis and transplantation is the only means of sustaining life for patients with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). Although transplantation is the treatment of choice, the number of donor kidneys are limited and transplants may fail. Hence many patients require long‐term or even life‐long dialysis. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is an alternative to hospital or home haemodialysis for patients with ESKD.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of CAPD versus hospital or home haemodialysis for adults with ESKD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL in The Cochrane Library Issue 12, 2011), the Cochrane Renal Group's specialised register (12 January 2012), MEDLINE (1966 to May 2002), EMBASE (1980 to May 2002), BIOSIS, CINAHL, SIGLE and NRR without language restriction. Reference lists of retrieved articles and conference proceedings were searched and known investigators and biomedical companies were contacted.

Date of last search: 12 January 2012.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs comparing CAPD to hospital or home haemodialysis for adults with ESKD were to be included.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assess the methodological quality of studies. Data was abstracted from included studies onto a standard form by one author and checked by another. Statistical analyses were performed using the random‐effects model and the results expressed as risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

One trial, reported in abstract form only, was located in the most recent search. There was no statistical difference in death or quality adjusted life years score at two years between peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis patients.

Authors' conclusions

There is Insufficient data to allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative effectiveness of CAPD compared with hospital or home haemodialysis for adults with ESKD. Efforts should be made to start and complete adequately powered RCTs, which compare the different dialysis modalities.

Plain language summary

Insufficient evidence from trials comparing CAPD (home dialysis without a machine) with hospital dialysis for people with kidney failure

When people's kidneys fail (end‐stage kidney disease), they need either a transplant or dialysis to keep performing the kidney's functions. Dialysis can involve either regular visits to hospital for time on an artificial kidney machine (haemodialysis), or home dialysis. Home dialysis (CAPD ‐ continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis) is a 'do it yourself' option that does not require a machine. It involves a tube permanently inserted through the abdomen to allow a fluid called dialysate to be emptied and replaced every day. The review found only one trial comparing the effects of CAPD and haemodialysis. No conclusions could be drawn.

Background

Renal replacement therapy (RRT) with dialysis and transplantation is the only means of sustaining life for patients with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). Although transplantation is the treatment of choice, the number of donor kidneys are limited and transplants may fail. Hence many patients require long‐term or even life‐long dialysis. Such therapy is not only associated with considerable morbidity and a significantly impaired quality of life (QoL), but also imposes a major economic burden on health services.

The two principal modes of dialysis for patients with ESKD are haemodialysis (HD) and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).

An artificial kidney (dialyser) is used in HD, which contains a semi‐permeable membrane. Dialysis relies on the principle that small molecules such as urea and creatinine, usually excreted by the kidney, can pass across this membrane down a concentration gradient. Removal of fluid from blood is achieved by applying hydrostatic pressure across the membrane. Acidosis is corrected by acetate or bicarbonate in the dialysis fluid (dialysate), which flows on the other side of the membrane. This procedure, which is most often performed in a hospital although it can be performed in a patients own home, requires the patient to have permanent easy access to the circulation usually obtained by creating an arterio‐venous fistula in the arm. HD is performed according to different schedules, ranging from four to eight hours, three times/week to the so‐called daily treatments (two to eight hours, six sessions/week) (Buoncristiani 1998; Charra 1992; Twardowski 2001).

The human peritoneal membrane is semi‐permeable and hence can be used as a dialysis membrane. CAPD can be carried out by the patient themselves at home and does not require a machine. Dialysate is left in the peritoneal cavity for six to eight hours allowing for equilibration and then drained out and fresh dialysate instilled. This can then be performed three to four times/day. Fluid removal relies on creating an osmotic gradient across the membrane using varying concentrations of glucose (or a glucose polymer) in the dialysate. This procedure requires a permanent catheter to be inserted into the abdomen.

In certain patients it may be not be possible to offer both types of dialysis therapy; those who have had extensive abdominal surgery for example may only be suitable for HD and those in whom the creation of vascular access (arterio‐venous fistula) has become impossible may be restricted to CAPD. Although medical issues do limit the choice of therapy for some patients, in the majority of cases the choice of dialysis modality is made by the patient and/or health personnel is based on non‐medical factors (Nolph 1993). This is reflected in the wide variation in the uptake of the two types of dialysis in different countries.

The current practice of RRT is not standardised and there are wide inter‐ and intra‐national variations, such as in the modality of treatment used and in the choices of membranes and solutions for HD, and of catheters and fluids for CAPD. There are also considerable differences in the length of time and the frequency of dialysis. In the 1980's the criteria for accepting patients for dialysis in the UK and elsewhere were broadened and older patients and those with co‐morbid illnesses, such as heart disease and diabetes, were accepted for treatment. Around this time CAPD was introduced which allowed the treatment of the increasing number of patients without the need to create more HD facilities, purchase expensive machines and employ large numbers of highly trained staff. There is variability in the use of peritoneal dialysis (PD) across countries. Fifteen percent of the United States ESKD population is on PD. In other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom (35%), New Zealand (55%) and Mexico (90%), the rates are higher (Heaf 2004; Mendelssohn 2001). It has been suggested that the reimbursement of both the physician and the dialysis facility is the strongest influence on the selection of treatment modality worldwide (Nissenson 1993). In the UK, factors which may influence the choice of treatment include distance of the patient's home from the renal unit (Dalziel 1987) and the presence of co‐morbid illnesses (Feest 1990). Once these factors have been taken into account, informed patient choice should be a major factor in influencing the choice of treatment modality. The two modalities are generally thought of as complementary and indeed patients may move from one treatment to the other if one technique fails. A decision about the choice of modality requires information on the effectiveness, acceptability and cost of the various modalities.

The aim of this review is to assess the benefits and harms of CAPD versus HD for ESKD.

Objectives

We aimed to assess the benefits and harms of CAPD versus hospital or home HD for adults with ESKD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (e.g. sealed, opaque sequentially numbered envelopes with third party involvement) and quasi‐RCTs (e.g. alternate patients, alternate treatments, allocation according to date of birth or medical record number) comparing CAPD with hospital or home HD for the management of adults with ESKD were to be included.

Types of participants

Adults with ESKD who were suitable for both CAPD or hospital or home HD irrespective of sex, race, primary kidney disease or co‐morbidity.

Types of interventions

CAPD was designated as the experimental treatment. A variable number (usually four) of manual PD exchanges performed in a 24 hour period by either the patient or an assistant.

HD was designated as control treatment comprising of a variable number (usually three) of dialysis sessions per week, performed in a home or hospital setting.

Types of outcome measures

Survival (overall mortality and cause‐specific mortality)

Haemoglobin/haematocrit

Biochemical indices of kidney disease (serum potassium, calcium, phosphate, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, radiological or histopathological evidence of renal bone disease)

QoL ‐ any scale of measure

Technique failure

Kt/V

Protein Catabolic Rate (PCR)

Systolic blood pressure

Diastolic blood pressure

Mean arterial blood pressure

Hospitalisation rate (days/patient/year)

Patient preference (if cross‐over study)

Employment status

costs and cost‐effectiveness

Search methods for identification of studies

This review has been adapted and updated from a Health Technology Assessment NHS R&D HTA Programme. Because this was one of a number of reviews of the management of ESKD undertaken at the same time, a broad search strategy was employed which attempted to identify all RCTs or quasi‐RCTs relevant to the management of ESKD (see additional Table 1 ‐ Electronic search strategies). This original search can been seen in full in this report (MacLeod 1998). Date of most recent search January 2004. Additional trials were sought from the following sources:

1. Electronic search strategies.

| Database/year | Search strategy |

| MEDLINE (1980 to Nov 1997) | 001 controlled clinical trial.pt. 002 randomized controlled trial.pt. 003 randomized controlled trials/ 004 random allocation/ 005 double blind method/ 006 single blind method/ 007 clinical trial.pt. 008 exp clinical trials/ 009 placebos/ 010 placebo$.tw. 011 random$.tw. 012 research design/ 013 volunteer$.tw. 014 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 015 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 016 factorial.tw. 017 cross‐over studies/ 018 crossover.tw. 019 latin square.tw. 020 (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 021 (animal not human).sh. 022 renal replacement therapy/ 023 exp hemodialysis/ 024 exp hemofiltration/ 025 kidney, artificial/ 026 exp peritoneal dialysis/ 027 ultrafiltration/ 028 dialysis/ 029 kidney failure, chronic/ 030 kidney failure, acute/ 031 uremia/ 032 (ultrafiltrat$ or dialy$).tw. 033 ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (replac$ or artificial or extracorpeal)).tw. 034 ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (disease$ or failure$ or sufficien$ or insufficien$)).tw. 035 ESRD.tw. 036 ur?emi$.tw. 037 biofilt$.tw. 038 (hemodia$ or haemodia$ or hemofilt$ or haemofilt$ or diafilt$)).tw. 039 predialy$.tw. 040 pre‐dialy$.tw. 041 or/23‐41 042 "erythropoietin"/ 043 epo.tw. 044 erythropoietin.tw. 045 epoetin.tw. 046 epogen.tw. 047 11096 26 7 erythropoietin.rn. 048 erythropoetin$.tw. 049 eprex.tw. 050 recormon.tw. 051 huepo.tw. 052 r‐HuEPO.tw. 053 "r.HuEPO".tw. 054 (r adj HuEPO).tw. 055 erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. 056 erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. 057 erythropoietin‐beta.tw. 058 erythropoietin$.tw. 059 rhEPO.tw. 060 epoietin.tw. 061 rHuEPO.tw. 062 or/42‐61 063 or/1‐20 064 63 not 21 065 41 and 62 and 64 |

| MEDLINE (Nov 1997 to Jun 2001) | 1. controlled clinical trial.pt. 2. randomized controlled trial.pt. 3. randomized controlled trials/ 4. random allocation/ 5. double blind method/ 6. single blind method/ 7. clinical trial.pt. 8. exp clinical trials/ 9. placebos/ 10. placebo$.tw. 11. random$.tw. 12. research design/ 13. volunteer$.tw. 14. (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 15. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 16. factorial.tw. 17. cross‐over studies/ 18. crossover.tw. 19. latin square.tw. 20. (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 21. (animal not human).sh. 22. or/1‐20 23. 22 not 21 24. renal replacement therapy/ 25. exp Renal Dialysis/ 26. exp hemofiltration/ 27. kidney, artificial/ 28. exp peritoneal dialysis/ 29. ultrafiltration/ 30. dialysis/ 31. exp kidney failure/ 32. exp dialysis solutions/ 33. hemodialysis units, hospital/ 34. uremia/ 35. (ultrafiltrat$ or dialy$).tw. 36. ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (replac$ or artificial or extracorpeal)).tw. 37. ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (diseases$ or failure$ or sufficien$ or insufficien$)).tw. 38. esrd.tw. 39. ur?emi$.tw. 40. biofilt$.tw. 41. (hemodia$ or haemodia$ or hemofilt$ or haemofilt$ or diafilt$).tw. 42. predialy$.tw. 43. pre‐dialy$.tw. 44. ESRF.tw. 45. Pre‐ESRF.tw. 46. Pre‐ESRD.tw. 47. ARF.tw. 48. CRF.tw. 49. or/24‐48 50. "erythropoietin"/ 51. epo.tw. 52. erythropoietin.tw. 53. epoetin.tw. 54. epogen.tw. 55. 11096 26 7 erythropoietin.rn. 56. erythropoetin$.tw. 57. eprex.tw. 58. recormon.tw. 59. huepo.tw. 60. r‐HuEPO.tw. 61. "r.HuEPO".tw. 62. (r adj HuEPO).tw. 63. erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. 64. erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. 65. erythropoietin‐beta.tw. 66. erythropoietin$.tw. 67. rhEPO.tw. 68. epoietin.tw. 69. rhuEPO.tw. 70. marogen.tw. 71. procrit.tw. 72. repotin.tw. 73. or/50‐72 74. 23 and 49 and 73 |

| EMBASE (1984 to Nov 1997) | (((controlled study)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(randomised controlled trial) @KMAJOR, KMINOR,(clinical study)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(clinical trial)@KMAJOR, KMINOR, (major clinical study)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(prospective study)@KMAJOR, KMINOR,(multicenter study)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(randomization)@KMAJOR, KMINOR,(double blind procedure)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(single blind procedure) @KMAJOR,KMINOR,(crossover procedure) @KMAJOR,KMINOR, (placebo) @KMAJOR,KMINOR),(random*, volunteer*, latin square*, (clin* + trial*), ((singl*, doubl*, trebl*, tripl*) + (blind*, mask*)), (balanced* + block*), (factorial + (design*, trial*)), "cross‐over", crossover)@(TI,AB,KWDS))+ ((kidney failure)@EX,(hemodialysis) @EX,(hemofiltration)@EX,(artificial kidney)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(ultrafiltration)@KMAJOR,KMINOR, (dialysis)@EX),(uremi*, uraemi*, renal disease*, renal failure*, renal sufficien*, renal insufficien*, biofilt*, predialy*, "pre‐dialy*", ESRD, esrf, "pre‐esrf", "pre‐ESRD", arf, crf, kidney* disease*, kidney* failure*, kidney* sufficien*, kidney insufficien*, ((kidney*, renal) + (replac*, artificial, extracorporeal)), haemodia*, hemodia*, hemofilt*, haemofilt*, diafilt*, ultrafilt*, dialy*)@(TI,AB,KWDS)) + ((erythropoietin)@KMAJOR,KMINOR,(epo, erythropoietin*, epoetin, epogen, erythropoetin, eprex, recormon, rhepo, epoietin, rhuepo, huepo, "r‐huepo", "r.huepo", "erythropoietin‐alpha", "erythropoietin‐alfa", "erythropoietin‐beta", r huepo)@(TI,AB,KWDS))) ‐ ((nonhuman)@KW‐((human)@KW+(nonhuman)@KW))) |

| EMBASE (Nov 1997 to Jun 2001) | 1. controlled clinical trial.pt. 2. randomized controlled trial.pt. 3. randomized controlled trials/ 4. random allocation/ 5. double blind method/ 6. single blind method/ 7. clinical trial.pt. 8. exp clinical trials/ 9. placebos/ 10. placebo$.tw. 11. random$.tw. 12. research design/ 13. volunteer$.tw. 14. (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 15. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 16. factorial.tw. 17. cross‐over studies/ 18. crossover.tw. 19. latin square.tw. 20. (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 21. (animal not human).sh. 22. or/1‐20 23. 22 not 21 24. renal replacement therapy/ 25. exp Renal Dialysis/ 26. exp hemofiltration/ 27. kidney, artificial/ 28. exp peritoneal dialysis/ 29. ultrafiltration/ 30. dialysis/ 31. exp kidney failure/ 32. exp dialysis solutions/ 33. hemodialysis units, hospital/ 34. uremia/ 35. (ultrafiltrat$ or dialy$).tw. 36. ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (replac$ or artificial or extracorporeal)).tw. 37. ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (diseases$ or failure$ or sufficien$ or insufficien$)).tw. 38. esrd.tw. 39. ur?emi$.tw. 40. biofilt$.tw. 41. (hemodia$ or haemodia$ or hemofilt$ or haemofilt$ or diafilt$).tw. 42. predialy$.tw. 43. pre‐dialy$.tw. 44. ESRF.tw. 45. Pre‐ESRF.tw. 46. Pre‐ESRD.tw. 47. ARF.tw. 48. CRF.tw. 49. or/24‐48 50. "erythropoietin"/ 51. epo.tw. 52. erythropoietin.tw. 53. epoetin.tw. 54. epogen.tw. 55. 11096 26 7 erythropoietin.rn. 56. erythropoetin$.tw. 57. eprex.tw. 58. recormon.tw. 59. huepo.tw. 60. r‐HuEPO.tw. 61. "r.HuEPO".tw. 62. (r adj HuEPO).tw. 63. erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. 64. erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. 65. erythropoietin‐beta.tw. 66. erythropoietin$.tw. 67. rhEPO.tw. 68. epoietin.tw. 69. rhuEPO.tw. 70. marogen.tw. 71. procrit.tw. 72. repotin.tw. 73. exp Erythropoietin/ 74. or/50‐73 75. 23 and 49 and 74 76. 19971$.em. 77. 1998$.em. 78. 1999$.em. 79. 200$.em. 80. 76 or 77 or 78 or 79 81. 2001$.em. 82. 2000$.em. 83. 76 or 77 or 81 or 82 |

| BIOSIS (1985 to Jan 1997) | #1: hemodia* #2: haemodia* #3: hemofilt* #4: haemofilt* #5: diafilt* #6: ultrafilt* #7: dialy* #8: biofilt* #9: (kidney* or renal) and (replac* or artificial or extracorporeal) #10: (renal or kidney*) and (disease* or failure* or sufficien* or insufficien*) #11: ESRD or esrf or "pre‐ESRD" or "pre‐esrf" or arf or crf #12: uremi* or uraemi* #13: #1or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 #14: BC86215 #15: clin* and trial* #16: singl* and (blind* or mask*) #17: doubl* and (blind* or mask*) #18: trebl* and (blind* or mask*) #19: tripl*) and (blind* or mask*) #20: placebo* #21: random* #22: volunteer* or factorial* #23: crossover or latin square #24: #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 #25: epo or erythropoietin* or epoetin or epogen or erythropoetin or eprex #26: recormon or rhepo or epoietin or rhuepo or huepo or "r‐huepo" or "r.huepo" #27: "erythropoietin‐alpha" or "erythropoietin‐alfa" or "erythropoietin‐beta" #28: r huepo #29: #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 #30: #13 and #14 and #24 and #29 |

| CINAHL (1982 to Oct 1997) | 001 "erythropoietin"/ 002 epo.tw. 003 erythropoietin.tw. 004 epoetin.tw. 005 epogen.tw. 006 erythropoetin$.tw. 007 eprex.tw. 008 recormon.tw. 009 huepo.tw. 010 r‐HuEPO.tw. 011 "r.HuEPO".tw. 012 (r adj HuEPO).tw. 013 erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. 014 erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. 015 erythropoietin‐beta.tw. 016 erythropoietin$.tw. 017 rhEPO.tw. 018 epoietin.tw. 019 rHuEPO.tw. 020 or/1‐19 |

| CHEMABS (1984 to Nov 1996) | renal terms ‐ hemodia*, haemodia*, hemofilt*, haemofilt*, dialy*, diafilt*, biofilt*, (kidney? or renal)(2w)(artificial or replac? or extracorporeal), (kidney? or renal)(2w)(disease? or failure? or sufficien? or insuffic?), uremi?, uraemi?, predialy?, pre(w)dialy?, esrf, pre(w)esrf, ESRD, pre(w)ESRD, arf, crf; Erythropoietin terms ‐ erythropoietin, 11096‐26‐7; Limits ‐ human, patient?. |

| HealthSTAR (1995 to Oct 1997) | 01 controlled clinical trial.pt. 02 randomized controlled trial.pt. 03 randomized controlled trials/ 04 random allocation/ 05 double blind method/ 06 single blind method/ 07 clinical trial.pt. 08 exp clinical trials/ 09 placebos/ 10 placebo$.tw. 11 random$.tw. 12 research design/ 13 volunteer$.tw. 14 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 15 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 16 factorial.tw. 17 cross‐over studies/ 18 crossover.tw. 19 latin square.tw. 20 (balance$ adj2 block$).tw. 21 (animal not human).sh. 22 or/1‐20 23 not 21 24 renal replacement therapy/ 25 exp hemodialysis/ 26 exp hemofiltration/ 27 kidney, artificial/ 28 exp peritoneal dialysis/ 29 ultrafiltration/ 30 dialysis/ 31 kidney failure, chronic/ 32 kidney failure, acute/ 33 uremia/ 34 (ultrafiltrat$ or dialy$).tw. 35 ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (replac$ or artificial or extracorpeal)).tw. 36 ((kidney$ or renal) adj2 (disease$ or failure$ or sufficien$ or insufficien$)).tw. 37 esrd.tw. 38 ur?emi$.tw. 39 biofilt$.tw. 40 (hemodia$ or haemodia$ or hemofilt$ or haemofilt$ or diafilt$)).tw. 41 predialy$.tw. 42 pre‐dialy$.tw. 43 ESRF.tw. 44 Pre‐ESRF.tw. 45 Pre‐ESRD.tw. 46 ARF.tw. 47 CRF.tw. 48 or/24‐47 49 "erythropoietin"/ 50 epo.tw. 51 erythropoietin.tw. 52 epoetin.tw. 53 epogen.tw. 54 11096 26 7 erythropoietin.rn. 55 erythropoetin$.tw. 56 eprex.tw. 57 recormon.tw. 58 huepo.tw. 59 r‐HuEPO.tw. 60 "r.HuEPO".tw. 61 (r adj HuEPO).tw. 62 erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. 63 erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. 64 erythropoietin‐beta.tw. 65 erythropoietin$.tw. 66 rhEPO.tw. 67 epoietin.tw. 68 rHuEPO.tw. 69 marogen.tw. 70 procrit.tw. 71 repotin.tw. 72 or/49‐71 73 23 and 48 and 72 |

| SIGLE (1980 to Jun 1996) | search term: renal SIGLE was searched in order to try to identify RCTs in the grey literature in this field |

| CRIB (1995) | search term: nephrology This database was searched in order to identify ongoing trials in the field of dialysis and end stage renal disease. Authors of ongoing trials relevant to the six topics were contacted to ascertain if the study was to be randomised. |

| UK NNR (1996) | Search terms (textword only): renal, haemodialy, haemofilt*, dialy, kidney*. This database was searched in order to identify ongoing trials in the field of dialysis and end stage renal disease. Authors of ongoing trials relevant to the six topics were contacted to ascertain if the treatment allocation was randomised |

| CCTR (Issue 1, 1997) | renal replacement therapy/; exp hemodialysis/ exp hemofiltration/ kidney artificial/ exp peritoneal dialysis/ ultrafiltration/ dialysis/ kidney failure chronic/ kidney failure acute/ uremia/ (ultrafiltrat* or dialy*).tw. ((kidney* or renal) adj2 (replac* or artificial or extracorporeal)).tw. ((kidney* or renal) adj2 (disease* or failure* or sufficien* or insufficien*)).tw. ESRD.tw. ur?emi*.tw. biofilt*.tw. (hemodia* or haemodia* or hemofilt* or haemofilt* or diafilt*)).tw. predialy*.tw. pre‐dialy*.tw. (these terms were combined together using the Boolean operator 'OR'). Erythropoietin terms: "erythropoietin"/ epo.tw. erythropoietin.tw. epoetin.tw. epogen.tw. 11096 26 7 erythropoietin.rn. erythropoetin*.tw. eprex.tw. recormon.tw. huepo.tw. r‐HuEPO.tw. "r.HuEPO".tw. (r adj HuEPO).tw. erythropoietin‐alpha.tw. erythropoietin‐alfa.tw. erythropoietin‐beta.tw. erythropoietin*.tw. rhEPO.tw. epoietin.tw. rHuEPO.tw. (these terms were combined together using the Boolean operator 'OR'). The 2 sets of search terms were combined with the Boolean operator AND. |

| CENTRAL Most recent search: Issue 11, 2012 | Renal replacement Haemodia* Hemodia* Dial* CAPD Peritoneal dialysis Artificial kidney Renal failure Kidney failure Uraemia Uremia CRF End stage renal disease End stage renal failure ESRD ESRF |

| RSC (on BIDS) (1980 to Feb 1997) | epo; erythropoietin*; epoetin; epogen;; erythropoetin*; eprex; recormon; huepo; "r‐HuEPO"; "r.HuEPO"; "erythropoietin‐alpha"; "erythropoietin‐alfa"; "erythropoietin‐beta"; epoietin; rHuEPO (all in title, abstract and keywords) and 11096‐26‐7 in the CAS registry number. |

| IBSS (British Library of Political and Economic Science) (1984 to Jul 1997) | erythropoietin*, erythropoetin*, epo, epoetin, epogen*, eprex*, recormon*, "r.huepo", "r‐huepo", rhepo, rhuepo, huepo |

| NHS Economic Evaluation Database NEED (Jul 1997) | erythropoietin$, erythropoetin$, epo, epoetin, epoietin, epogen, eprex$, recormon$, "r.huepo", "r‐huepo", rhepo, rhuepo |

| http://www.hotbot.com/ (August 1997) | (erythropoietin OR "erythropoietinalfa" OR "erythropoietinalpha"OR "erythropoietinbeta" OR epo OR eprex OR epogen OR recormon OR epoetin OR huepo OR marogen OR procrit OR repotin OR "rhuepo" OR rhuepo OR "rhuepo" OR "rhuepo") AND ((trial AND (clinical OR controlled OR randomized OR randomised)) OR blind) AND (kidney OR renal OR hemodialysis OR hemofiltration OR haemodialysis OR haemofiltration OR diafiltration OR predialysis OR "predialysis" OR uremia OR uraemia) AND NOT (hiv OR aids OR autologous) In order to get round length limitations, this was manually converted to a web address and submitted as: http://www.hotbot.com/?MT=%28erythropoietin+OR+%22erythropoietinalfa%22+OR+ %22erythropoietinalpha%22+OR+%22erythropoietinbeta%22+OR+epo+OR+eprex+OR+e pogen+OR+recormon+OR+epoetin+OR+huepo+OR+marogen+OR+procrit+OR+repotin+OR+%2 2rhuepo%22+OR+rhuepo+OR+%22rhuepo%22+OR+%22rhuepo%22%29+AND+%28%28trial+ AND+%28clinical+OR+controlled+OR+randomized+OR+randomised%29%29+OR+blind%29+ AND+%28kidney+OR+renal+OR+hemodialysis+OR+hemofiltration+OR+haemodialysis+OR +haemofiltration+OR+diafiltration+OR+predialysis+OR+%22predialysis%22+OR+ur emia+OR+uraemia%29+AND+NOT+%28hiv+OR+aids+OR+autologous%29&SW=web&SM=B&RG=NA &_v=2&DC=100&DE=0&act.search.x=1&act.search.y=1 |

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials ‐ CENTRAL ‐ and the Cochrane Renal Group specialised register.

Handsearching: Kidney International (including supplements) 1980 to 1997 was hand searched. However, conference proceedings, published in abstract form only, were only searched for one year, 1994. Conference proceedings are now searched by the Cochrane Renal Group and additional studies are included in the Specialised Register. Hand‐searching was performed by two members of the team, one of whom was a Nephrologist. Two quality assurance controls were implemented. A 'Gold Standard' was devised. This consisted of the 1990 and 1995 volumes of Kidney International which were searched by both hand‐searchers independently. After discussion an agreed assessment of all studies in these issues was made; this became the 'Gold Standard'. A sensitivity and precision (specificity) of greater than 90% was required of each searcher. Quality of hand‐searching throughout the period of the review was maintained by each author checking 5% of the other author's studies. This 5% was chosen at random. We attempted to identify all possible RCTs and controlled clinical trials regardless of subject matter. All identified trials were notified to the Renal Cochrane Collaborative Group and to the Baltimore Cochrane Centre. Hard copies were made of the complete identified trials relevant to this review.

Bibliographies of all studies included in these reviews, of all other identified relevant studies and of relevant book chapters were examined by subject‐experts (nephrologists). We limited this bibliography searching to the 'first generation' studies only. We therefore did not search the bibliographies of studies originally identified from a previous bibliographic search.

Authors of included studies and of studies whose methodology we were seeking clarification were contacted to ascertain if they knew of any further published, unpublished or still‐to‐be completed RCTs on this particular subject.

Relevant biomedical companies were contacted to identify further published, unpublished or incomplete studies.

We advertised our interest in finding published and unpublished RCTs and quasi‐RCTs in any language relevant to this topic at the Exploratory meeting for the Renal Cochrane Collaborative Review Group, in Lyon, in March 1996 and at the Renal Association, UK, April 1996.

Data collection and analysis

During an initial pilot project, all abstracts were read by both a subject expert and a methodology expert. There was a high degree of concurrence between them but they were assessed markedly more quickly by the subject experts and it was decided that they alone should assess the abstracts. Hard copies of studies whose title or abstract were assessed as potentially relevant were obtained, and were assessed for subject relevance and methodological quality.

The assessors were not blinded to author, institution nor journal of the assessed studies. Any differences of opinion was resolved by discussion. If agreement could not be reached, a third assessor would evaluate the study, and, ware of the previous team's deliberations reached a final decision. A single investigator abstracted data from each study describing the characteristics of participants, interventions and outcome measures using a standard form. Only published data in the identified trials was used; no raw data was sought although authors would be contacted to clarify points in the Methods or Results sections of their papers.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies were assessed independently without blinding to authorship, using the criteria of the Cochrane Renal Group adapted from Crowther 1998. Any difference of opinion was resolved by discussion. The quality items to be assessed were allocation concealment, intention‐to‐treat analysis, completeness of follow‐up and blinding of participants, investigators and outcome assessment.

Allocation Concealment

Adequate: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study.

Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available.

Inadequate: Method of randomisation used such as alternate medical record numbers or unsealed envelopes; any information in the study that indicated that investigators or participants could influence intervention group

Blinding

Blinding of investigators: Yes/no/not stated

Blinding of participants: Yes/no/not stated

Blinding of outcome assessor: Yes/no/not stated

Blinding of data analysis: Yes/no/not stated

The above were considered not blinded if they knew the treatment group or could identify it in >20% of participants because of side effects of treatment.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Yes: Specifically reported by authors that intention‐to‐treat analysis was undertaken and this was confirmed on study assessment.

Yes: Not reported but confirmed upon study assessment

No: Not reported and lack of intention‐to‐treat analysis confirmed on study assessment (patients who were randomised were not included in the analysis because they did not receive the study intervention, they withdrew from the study or were not included because of protocol violation).

Unclear: Not reported and not clear from study assessment

Completeness of follow‐up

Per cent of patients lost to follow up during study

Economic assessment

Where economic data (costs, economic measures of effectiveness such as quality adjusted life years, and cost‐effectiveness) were reported additional quality assessment was performed. This quality assessment used the Drummond checklist for the critical appraisal of economic evaluations (Drummond 1997). This checklist asks a series of questions relating to the quality of the economic component of the study. These were:

Was a well‐defined question posed in an answerable form? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Was a comprehensive description of the competing alternatives given (i.e. can you tell who, did what, to whom, where, and how often)? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Was there evidence that the programmes effectiveness had been established? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were all important and relevant costs and consequences for each alternative identified? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were costs and consequences measured accurately in appropriate physical units? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were costs valued credibly? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were consequences valued credibly? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were costs adjusted for differential timing? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Were consequences adjusted for differential timing? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Was an incremental analysis of costs and consequences of alternatives performed? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Did the presentation and discussion of study results include all issues of concern to users? Yes/No/Cannot tell

Studies that did not present a full economic evaluation (studies that only reported either costs or economic measures of effects) were only assessed against those questions that were relevant. (see additional Table 2 ‐ Quality assessment of economic studies (Questions 1 to 5) and Table 3 ‐ Quality assessment of economic studies (Questions 6 to 11))

2. Quality assessment of economic studies (Questions 1 to 5).

| Study ID | Defined question | Desc of alternatives | Effects established | Relevant C & E | Natural units | Credible costs |

| Korevaar 2003 | Yes. Are HD and PD equivalent in terms of survival and quality of life | No. It is unclear which types of HD and peritoneal dialysis were given | No. Although based on an RCT the methods used to calculate QALYs were not reported | NA. Costs not considered as part of the study | Yes. Given the aims of the study | NA costs not considered |

3. Quality assessment of economic studies (Questions 6 to 11).

| Study ID | Credible effects | Discounting costs | Discounting effects | Incremental analysis | Disc of concerns | Q 11 |

| Korevaar 2003 | No. Source of quality of life scoring system not provided. Description of derivation of QALYs is also not explained and the method of presentation is unusual | NA | No | Yes | No. Study report is brief although interpretation of data presented appears appropriate |

Statistical assessment

For dichotomous outcomes the risk ratio (RR) was to be calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and summary statistics estimated using the random effects model. Heterogeneity was to be analysed with a threshold value of P < 0.1 used for statistical significance. Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment, data was to be analysed in continuous form as the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used with 95% CI.

Results

Description of studies

The sensitive search strategy (MacLeod 1998) resulted in a large number of abstracts (11,800). Despite this, no RCTs or quasi‐RCTs were identified when this study was first published in 2003. One abstract reporting a RCT comparing CAPD to hospital or home HD was identified by the additional search performed in January 2004.

The one study identified was only reported in abstract form (Korevaar 2003). The study described a comparison of HD and PD although it was unclear precisely which form of HD or PD were considered.

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of the methodological quality of the included RCT are outlined in the description of included studies and in the additional tables. The included study appeared to be a multicentred RCT but due to brevity of reporting it was unclear whether allocation was concealed, analysis was on intention to treat basis and how complete the follow‐up was of study participants. In terms of blinding it was unclear whether investigators, outcome assessors or data analysts were blinded to treatment allocation. Given the nature of the interventions it is unlikely that participants could have been blinded to treatment allocation. The trial stopped recruitment before the prespecified sample size due to poor recruitment.

In terms of the economic component of the study the methods used were not well described and it is unclear precisely how quality adjusted life years (QALYs) were assessed. This is a concern as the method of reporting QALYs is not standard (Drummond 1997) as it would be expected that the score would be between 0 and 2 (QALYs are calculated by weighting survival, measured in years by a quality of life weight. Typically, full health is given a weight of 1 and death a weight of 0). The authors of the trial have been contacted by the Cochrane Renal Group for clarification of the method/s used.

Effects of interventions

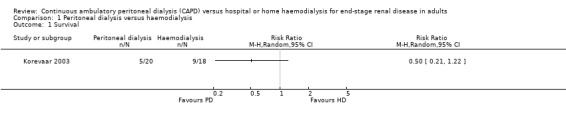

Survival

At five years 5/20 PD and 9/18 HD patients had died. There was no significant difference in survival between PD and HD (Analysis 1.1: RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.22). The trial reported that after adjusting for any baseline differences in age, comorbidity and primary kidney disease the hazard ratio was 3.6 (95% CI 0.8 to 15.4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis, Outcome 1 Survival.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured in terms of mean QALYs score at two years. There was no significant difference between PD and HD (Analysis 1.2: MD ‐5.10, 95% CI ‐15.10 to 4.90).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis, Outcome 2 Quality of life ‐ QALYs score at 2 years.

Discussion

It was chastening that only one small RCT comparing PD and HD (Korevaar 2003) was identified despite checking approximately 12,000 abstracts identified in the literature searching. As this study report is only available in abstract form, the quality of the study is difficult to determine. Furthermore, the trial was smaller than intended due to the difficulty of recruitment and as a result the results are imprecise as well as being potentially unreliable and the probability of a type II error cannot be excluded. It would be helpful if details of how and why the study failed to achieve its recruitment targets were made available so that future studies can take steps to avoid similar problems.

The issue facing the health services is not whether to have CAPD or HD but rather the balance of provision between the two modalities. It is known from variations in uptake of these techniques in different countries that a proportion of patients requiring dialysis for ESKD could be managed with either CAPD or HD initially. What is still required is information about the relative costs, benefits and risks of policies that start with one or other modality. Ideally information on benefits and risks should come from comparisons, within a large pragmatic RCT.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Data from robust RCTs are not available to allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative effectiveness of HD and CAPD and as such changes in practice can not be supported by evidence on effectiveness or efficiency.

Implications for research.

Efforts should be made to undertake adequately powered RCTs or well designed observational studies that compare the different dialysis modalities. Given the development of new techniques in dialysis therapy such as continuous cycling PD (CCPD), additional evaluation is required to investigate their place in the treatment of ESKD alongside HD and CAPD.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 September 2016 | Amended | Minor edit to excluded studies |

| 22 September 2016 | Review declared as stable | No new or ongoing studies since 2003, therefore this review is no longer being updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 January 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Our conclusions did not change |

| 12 January 2012 | New search has been performed | Four reports were identified (1 abstract; 3 ongoing) |

| 13 May 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 23 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 8 July 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

No new or ongoing studies since 2003, therefore this review is no longer being updated

Acknowledgements

Funded by the NHS Executive R&D Health Technology Assessment Programme. The Health Services Research Unit and Health Economics Research Unit are funded by the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Survival | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Quality of life ‐ QALYs score at 2 years | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Korevaar 2003.

| Methods | Method of random allocation: not described Unclear whether investigators, outcome assessors or data analysis was blinded. It is not stated whether participants were blinded but the nature of the interventions makes it unlikely Description of withdrawals/dropouts: not mentioned Analysis on intention to treat basis: unclear Completeness of follow‐up: unclear Duration of follow‐up 5 years |

|

| Participants | 38 patients receiving dialysis treatment for ESKD. 18 randomised to HD and 20 to PD Inclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria: Patients from 38 Dutch dialysis units with no medical, social or logistic objections. Further details not provided Proportion male: 58% Age (mean, SD) Overall 59 (12) Primary kidney disease: Overall 24% diabetes mellitus, 18% renal vascular disease |

|

| Interventions | PD vs HD | |

| Outcomes | Quality of life (measured in quality adjusted life years [QALYs] at 2 years) Survival (at five years) |

|

| Notes | Trial recruitment stopped early due to problems with recruitment. QALYs are measure of effectiveness used in economic evaluations. further quality assessment is described in the additional tables | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ateshkadi 1995 | Not an RCT |

| Dursun 2004 | Not an RCT |

| Foley 2004 | Not an RCT |

| Gagnon 1983 | Not an RCT |

| IDEAL Study 2004 | Randomised to early versus late referral |

| Odor‐Morales 1987 | Not an RCT |

| Selgas 2001 | Not an RCT |

| Shmueli 1987 | Not an RCT, study in children |

| Suzuki 2003 | Not an RCT |

Contributions of authors

All authors were fully involved in conceiving, designing, and co‐ordinating the review. Sheila Wallace conducted the initial searches and organised retrieval of papers. Alison MacLeod, Conal Daly and Marion Campbell screened the search results. Luke Vale wrote the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Aberdeen, UK.

Health Services Research Unit, UK.

Health Economics Research Unit, UK.

External sources

NHS Research and Development, Health Technology Assessment Programme, UK.

Declarations of interest

A MacLeod currently chairs the Standards and Audit Subcommittee of the Renal Association. (UK)

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Korevaar 2003 {published data only}

- Korevaar J, Feith G, Dekker F, Manen J, Boeschoten E, Bossuyt P, et al. Effects of starting with hemodialysis compared with peritoneal dialysis in patients new on dialysis treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2003; Vol. 18 (Suppl 4):199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Korevaar JC, Feith GW, Dekker FW, Manen JG, Boeschoten EW, Bossuyt PM, et al. Effect of starting with hemodialysis compared with peritoneal dialysis in patients new on dialysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Kidney International 2003;84(6):2222‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ateshkadi 1995 {published data only}

- Ateshkadi A, Johnson CA, Founds HW, Zimmerman SW. Serum advanced glycosylation end‐products in patients on hemodialysis and CAPD. Peritoneal Dialysis International 1995;15(2):129‐33. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dursun 2004 {published data only}

- Dursun B, Demircioglu F, Varan HI, Basarici I, Kabukcu M, Ersoy F, Ersel F, Suleymanlar G. Effects of different dialysis modalities on cardiac autonomic dysfunctions in end‐stage renal disease patients: one year prospective study. Renal Failure 2004;26(1):35‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Foley 2004 {published data only}

- Foley RN. Comparing the incomparable: hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis in observational studies. Peritoneal Dialysis International 2004;24(3):217‐21. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gagnon 1983 {published data only}

- Gagnon RF, Shuster J, Kaye M. Auto‐immunity in patients with end‐stage renal disease maintained on hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Journal of Clinical & Laboratory Immunology 1983;11(3):155‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

IDEAL Study 2004 {published data only}

- Brunkhorst R. Early versus late initiation of dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(24):2368‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J, Cooper B, Branley P, Bulfone L, Craig J, Fraenkel M, et al. Outcomes of patients with planned initiation of hemodialysis in the IDEAL trial. Contributions to Nephrology 2011;171:1‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins J, Craig J, Fraenkel M, et al. The results of the initiating dialysis early and late trial [abstract no: 166]. Nephrology 2010;15(Suppl 4):70. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Dempster J, et al. The initiating dialysis early and late (IDEAL) study: study rationale and design. Peritoneal Dialysis International 2004 Mar;24(2):176‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(7):609‐19. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaun N, Kluth D. Early versus late initiation of dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(24):2369‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust J, Schreiner O. Early versus late initiation of dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(24):2368‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Cooper BA, Li JJ, Bulfone L, Branley P, Collins JF, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of initiating dialysis early: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2011;57(5):707‐15. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepe V, Libetta C, Dal Canton A. Early versus late initiation of dialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;363(24):2369‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley GA, Marwick TH, Doughty RN, Cooper BA, Johnson DW, Pilmore A, et al. Effect of early initiation of dialysis on cardiac structure and function: results from the echo substudy of the IDEAL trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2013;61(2):262‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MG, Pollock CA, Cooper BA, Branley P, Collins JF, Craig JC, et al. Association between GFR estimated by multiple methods at dialysis commencement and patient survival. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2014;9(1):135‐42. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Odor‐Morales 1987 {published data only}

- Odor‐Morales A, Castorena G, Jimeno C, Pena JC, Bordes J, Rosa C, et al. Hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis before transplantation: prospective comparison of clinical and hemodynamic outcome. Transplantation Proceedings 1987;19(1 Pt 3):2197‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Selgas 2001 {published data only}

- Selgas R, Cirugeda A, Fernandez‐Perpen A, Sanchez‐Tomero JA, Barril G, Alvarez V, et al. Comparisons of hemodialysis and CAPD in patients over 65 years of age: a meta‐analysis. International Urology & Nephrology 2001;33(2):259‐64. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shmueli 1987 {published data only}

- Shmueli D, Yussim A, Nakache R, Eisenstein B, Davidovitz M, Stark H, et al. Kidney transplantation in children on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis [abstract]. Pediatric Nephrology 1987:C32. [Google Scholar]

Suzuki 2003 {published data only}

- Suzuki T, Kanno Y, Nakamoto H, Okada H, Sugahara S, Suzuki H. Peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis: a five‐year comparison of survival and effects on the cardiovascular system, erythropoiesis, and calcium metabolism. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis 2003;19:148‐54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Buoncristiani 1998

- Buoncristiani U, Quintaliani G, Cozzari M, Giombini LR. Daily dialysis: long term clinical and metabolic results. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 1998;24:137‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Charra 1992

- Charra B, Calemard M, Ruffet M, Chazot C, Terrat JC, Vanel T, et al. Survival as an index of adequacy of dialysis. Kidney International 1992;41(5):1286‐91. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crowther 1998

- Crowther CA, Henderson‐Smart DJ. Phenobarbital prior to preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 2. [Google Scholar]

Dalziel 1987

- Dalziel M, Garrett C. Intraregional variation in treating end stage renal failure. British Medical Journal Clinical Research Ed 1987;294(6584):1382‐3. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drummond 1997

- Drummond M, O'Brien B, Stoddart G, Torrance G. Methods for the economic evaluation of healthcare programmes. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Feest 1990

- Feest TG Mistry CD, Grimes DS, Mallick NP. Incidence of advanced chronic renal failure and the need for end stage renal replacement treatment. BMJ 1990;301(6757):897‐900. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heaf 2004

- Heaf J. Underutilization of peritoneal dialysis. JAMA 2004;291(6):740‐2. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mendelssohn 2001

- Mendelssohn DC. Mullaney SR. Jung B. Blake PG. Mehta RL. What do American nephologists think about dialysis modality selection?. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2001;37(1):22‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nissenson 1993

- Nissenson AR, Prichard SS, Cheng IK, Gokal R, Kubota M, Maiorca R, et al. Non‐medical factors that impact on ESRD modality selection. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 1993;43(40):120‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nolph 1993

- Nolph KD, Henderson LW. Editorial. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 1993;43(40):1‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Twardowski 2001

- Twardowski ZJ. Daily dialysis: is this a reasonable option for the new millennium?. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2001;16(7):1321‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

MacLeod 1998

- MacLeod A, Grant A, Donaldson C, Khan I, Campbell M, Daly C, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of methods of dialysis therapy for end‐stage renal disease: systematic reviews. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 1998;2(5):1‐166. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vale 2002

- Vale L, Cody J, Wallace S, Daly C, Campbell M, Grant A, et al. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) versus hospital or home haemodialysis for end‐stage renal disease in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003963] [DOI] [Google Scholar]