Abstract

Background

Depressive illness is common in old age. Prevalence in the community of case level depression is around 15% and milder forms of depression are more common. It causes significant distress and disability. The number of people over the age of 60 years is expected to double by 2050 and so interventions for this often long‐term and recurrent condition are increasingly important. The causes of late‐life depression differ from depression in younger adults and so it is appropriate to study it separately.

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2012.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in preventing the relapse and recurrence of depression in older people.

Search methods

We performed a search of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's specialised register (the CCMDCTR) to 13 July 2015. The CCMDCTR includes relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from the following bibliographic databases: The Cochrane Library (all years), MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date), and PsycINFO (1967 to date). We also conducted a cited reference search on 13 July 2015 of the Web of Science for citations of primary reports of included studies.

Selection criteria

Both review authors independently selected studies. We included RCTs involving people aged 60 years and over successfully treated for an episode of depression and randomised to receive continuation and maintenance treatment with antidepressants, psychological therapies, or a combination.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data. The primary outcome for benefit was recurrence rate of depression (reaching a cut‐off on any depression rating scale) at 12 months and the primary outcome for harm was drop‐outs at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included relapse/recurrence rates at other time points, global impression of change, social functioning, and deaths. We performed meta‐analysis using risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

This update identified no further trials. Seven studies from the previous review met the inclusion criteria (803 participants). Six compared antidepressant medication with placebo; two involved psychological therapies. There was marked heterogeneity between the studies.

Comparing antidepressants with placebo on the primary outcome for benefit, there was a statistically significant difference favouring antidepressants in reducing recurrence compared with placebo at 12 months with a GRADE rating of low for quality of evidence (three RCTs, n = 247, RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.82; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 5). Comparing antidepressants with placebo on the primary outcome for harms, there was no difference in drop‐out rates at 12 months' follow‐up, with a GRADE rating of low.

There was no significant difference between psychological treatment and antidepressant in recurrence rates at 12 months (one RCT, n = 53) or between combination treatment and antidepressant alone at 12 months.

Authors' conclusions

This updated Cochrane review supports the findings of the original 2012 review. The long‐term benefits and harm of continuing antidepressant medication in the prevention of recurrence of depression in older people are not clear and no firm treatment recommendations can be made on the basis of this review. Continuing antidepressant medication for 12 months appears to be helpful with no increased harms; however, this was based on only three small studies, relatively few participants, use of a range of antidepressant classes, and clinically heterogeneous populations. Comparisons at other time points did not reach statistical significance.

Data on psychological therapies and combined treatments were too limited to draw any conclusions on benefits and harms.

The quality of the evidence used in reaching these conclusions was low and the review does not, therefore, offer clear guidance to clinicians and patients on best practice and matching interventions to particular patient characteristics.

Of note, we identified no new studies that evaluated pharmacological or psychological interventions in the continuation and maintenance treatment of depression in older people. We are aware of studies conducted since the previous review that included both older people and adults under the age of 65 years, but these fall outside of the remit of this review. We believe that there remains a need for studies solely recruiting older people, particularly the 'older old' with comorbid medical problems. However, these studies are likely to be challenging to conduct and may not, so far, have been prioritised by funders.

Keywords: Aged, Female, Humans, Male, Middle Aged, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Combined Modality Therapy, Combined Modality Therapy/methods, Depression, Depression/therapy, Maintenance Chemotherapy, Maintenance Chemotherapy/methods, Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Secondary Prevention

Plain language summary

Long‐term treatment for depression in older people

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2012.

Why is this review important?

Depression is a common problem among older people and causes considerable disability. Even after successful treatment, it frequently recurs.

The causes of depression in older people are more diverse than in younger adults and, as the number of older people is steadily increasing, it is important to study the effects of treatments specifically in older adults. Treatments commonly used are antidepressant drugs and psychological treatments (talking treatments).

Who will be interested in this review?

‐ People with depression, friends, families, and carers.

‐ General practitioners, psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, psychological therapists, and pharmacists.

‐ Professionals working in older‐adult mental health services.

‐ Professionals working in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies services in the UK.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

In people aged 60 years and over who have recovered from depression while taking antidepressant medication:

‐ Is receiving continued antidepressant medicine, psychological treatment, or a combination of the two more effective in preventing recurrence of depression than receiving placebo (a pretend treatment) or any of the other treatments?

‐ Is receiving continued antidepressant medicine, psychological treatment, or a combination of the two more harmful than receiving placebo or any of the other treatments?

Which studies does the review include?

We searched medical databases to find all relevant studies completed up to 13 July 2015. The studies had to compare antidepressant treatment, psychological treatment, or a combination of the two, with placebo or the other treatments for preventing recurrence of depression in people aged 60 years and over. We included seven studies, involving 803 people.

Six studies compared antidepressant medicine with placebo. Only two of the studies involved psychological treatments. The studies varied in how they were conducted, numbers of participants, and types of participants.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

Remaining on antidepressant medicines for one year appears to reduce the risk of depression returning from 61% to 42% but the benefits at other time intervals could not be determined. Antidepressant treatment appeared to be no more harmful than placebo as measured by number of participants dropping out of trials. The benefits of psychological therapies were not clear, due to the small number of studies. The quality of evidence was low.

The majority of participants in the studies were women. Few were over 75 years of age. Most had received treatment for their original depressive illness as outpatients, indicating less severe depression.

Antidepressant medicines used were both older type antidepressants (called tricyclics) and newer type (called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). Psychological treatments were interpersonal therapy, which addresses obstacles in relationships, and cognitive behavioural therapy, which addresses inactivity and self‐defeating thought patterns.

What should happen next?

This review provides limited evidence that continuing antidepressant medication for one year can reduce the risk of depression recurring with no additional harm. However, it cannot be used to make firm recommendations due to the limited number and small size of studies involved. Limitations in the design and reporting of these studies may also make the results unrepresentative. Similarly, no firm conclusions can be drawn about psychological treatments or combinations of antidepressant and psychological treatments in preventing recurrence.

Further, larger, trials are required to clarify any benefits of antidepressant and psychological treatments. These trials should include more people aged over 75, and people with other problems typical of people treated in routine clinical services, such long‐term physical illness and mild memory problems.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antidepressant medication compared with placebo at 12 months' follow‐up.

| Antidepressant medication compared with placebo at 12 months' follow‐up | ||||||

| Patient or population: older people in remission from depression Setting: mixed Intervention: antidepressant Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with antidepressant | |||||

| Recurrence at 12 months | Study population | RR 0.67 (0.55 to 0.82) | 247 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1 | 2 trials used TCAs (OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a); 1 used an SSRI (Klysner 2002). Trials varied in setting, mean age, cut‐off for remission, and length of remission before randomisation | |

| 730 per 1000 | 489 per 1000 (402 to 599) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 759 per 1000 | 508 per 1000 (417 to 622) | |||||

| Overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) at 12 months | Study population | RR 1.48 (0.75 to 2.92) | 121 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Only 1 trial reporting drop‐outs at 12 months (Klysner 2002). Reynolds 1999b reported drop‐outs but not timing | |

| 180 per 1000 | 267 per 1000 (135 to 527) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 180 per 1000 | 267 per 1000 (135 to 526) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1. Downgraded one point for imprecision (only three studies) and one point for risk of bias since allocation concealment and blinding were unclear for two of the studies and study protocols were not available for all three studies.

2. Downgraded two points due to imprecision (only one study; wide confidence intervals).

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is among the most common of psychiatric disorders. It remains common in old age, occurring more frequently than dementia. Several community studies have shown a prevalence in the population over 64 years of age of around 15% of case level depression (i.e. that which a psychiatrist would consider in need of treatment) (Evans 2003). Milder forms of depression are likely to be more common and still account for significant suffering. Very old people are particularly prone to developing depression (Blazer 2000).

Depression is important because it causes significant distress and is associated with a great deal of disability in older people. Chronic depression is associated with over five times the odds of worsening disability over three years (Lenze 2005). The number of people over the age of 60 years is expected to double by 2050 and so interventions for long‐term and recurrent conditions such as depression will become more important in maintaining healthy functioning (WHO 2015).

The causes of late‐life depression, especially in cases with onset after 50 years of age, are thought to differ from depression in younger adults. They include neuropsychological abnormalities such as executive dysfunction (Gansler 2015), and physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stroke (Valkonova 2013). This makes it appropriate to study late‐life depression separately from depression in younger adults. It also means that it would be useful to establish if there is a difference in treatment response between late‐onset and early‐onset illness.

Description of the intervention

A range of antidepressant medications are used to treat older people. They include older agents such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), as well as newer agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NASSAs), and reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs) (Abou‐Saleh 2010). TCAs include imipramine and amitriptyline; SSRIs include sertraline and citalopram; SNRIs include venlafaxine; NASSAs include mirtazapine; and RIMAs include moclobemide.

Several short‐term psychological therapies are used to treat older people with depression, including behavioural therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and psychodynamic therapy. Behavioural therapy uses an operant conditioning model to reintroduce positive reinforcement, to reduce the time spent on negative events, and to overcome avoidance through behavioural activation. CBT begins with behavioural activation but also tackles the thought patterns that maintain inactivity and depressed mood by using direct verbal challenging and behavioural experiments. Problem‐solving therapy teaches a structured approach to tackling inactivity, lack of pleasurable activities, and dealing with psychosocial problems. Interpersonal psychotherapy focuses on the interplay between depression and interpersonal relationships. It uses patient education and a number of strategies such as role play and communication analysis to tackle obstacles in relationships (Wilkinson 2010). Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy combines teaching on the role of thought patterns in depression with training in meditation techniques (Segal 2002). Psychodynamic psychotherapy focusses on the person's life review, losses experienced, attitudes to ageing, and the relationship with the therapist (Garner 2008). Counselling, such as Rogerian person‐centred therapy, is an unstructured psychological therapy with an emphasis on warmth, genuineness, and empathy in the therapeutic relationship (Zarit 1998).

There is a small number of trials that support the efficacy of psychological therapies as acute phase interventions with older people, but fewer than with younger people (NICE 2010). One Cochrane review found cognitive behavioural interventions to be superior to waiting list control in five trials, but the authors suggested caution in generalising this finding to clinical populations due to the small number of participants (Wilson 2008). A more recent trial with 204 participants in primary care showed benefits of combining CBT with treatment as usual (including antidepressants) as compared with treatment as usual and treatment as usual plus a talking control (Serfaty 2009).

How the intervention might work

Older adults with depression are frequently prescribed antidepressants (Percudani 2005), and the short‐term response to treatment is generally good (Katona 2002). Antidepressant action is thought to result from regulation of the monoamine neurotransmitter changes that occur in depressive illness. The rationale for continuing antidepressant treatment after clinical recovery, therefore, is that it will sustain regulation of monoamine activity.

Individual CBT is as effective as antidepressants in reducing symptoms of depression and produces more enduring benefit than antidepressant treatment; it also appears to be better tolerated than antidepressants. Adding CBT to antidepressant treatment can also improve outcome in more severe depression and possibly in chronic depression (NICE 2010). People with residual symptoms of depression after treatment have a poorer prognosis and psychological therapies may have an important role in reducing relapse and recurrence rates in these people (Paykel 2005).

Interpersonal psychotherapy can be used as a short‐term acute phase treatment of depression (usually up to 16 sessions) or as a maintenance treatment with sessions more widely spaced over a period of months. The use of maintenance treatment allows for a greater number of therapeutic foci to be addressed including the long‐standing patterns of interpersonal behaviour that may contribute to recurrence (so‐called interpersonal deficits) (Miller 2003).

Maintenance CBT involves helping the person to continue to identify and address the behavioural and cognitive patterns associated with depressive relapse (Wilkinson 2009). CBT can continue to have a positive effect after it is discontinued (Blackburn 1997), and, in younger adults, combining antidepressant medication and psychological therapies in the continuation phase produces better long‐term results than antidepressants alone (Paykel 2005). Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy is an intervention partly derived from CBT that is used in the maintenance treatment of depression. It combines teaching in the cognitive model of depression with meditation‐based exercises (Segal 2002) to help the individual to recognise when their mood is beginning to become low, and to develop the capacity to allow distressing mood, thoughts, and sensations to come and go without engaging with them.

Psychodynamic therapy for depression is based on a model of vulnerability arising from early life experiences and disrupted childhood attachment. The relationship with the therapist is of key importance in identifying and fostering insight into psychological defence mechanisms. Psychodynamic therapy with the older person may help to develop a long‐term sense of contentment and acceptance of the losses and changes associated with ageing (Garner 2008).

As antidepressants and psychological therapies have different modes of action, combining them may produce greater benefits than either treatment alone. Psychological therapy may also include education on the benefits of antidepressant medication in order to foster treatment concordance.

Why it is important to do this review

This review adds to a programme of Cochrane reviews addressing the acute management of depression in older people with psychological therapies (Wilson 2008) and antidepressants (Mottram 2009).

The long‐term prognosis of late‐life depression is known to be poor, with around a quarter of people becoming depressed within two years of remission or recovery and a third experiencing one or more relapses after two years (Cole 1997). Therefore, it is important to identify treatments that will improve longer‐term outcome (i.e. reduce rates of recurrence and relapse). In younger adults, continuing antidepressant medication after remission reduces the odds of relapse by 70% with effects lasting up to 36 months, as long as medication is continued (Geddes 2003).

Most previous reviews of trials with older adults have been narrative reviews and have focused on the acute treatment of depression (Areán 2007). None have included both antidepressant medication and psychological therapies. This review includes trials of antidepressant medication, psychological therapies, and combinations of the two in the continuation and maintenance phase treatment of depression in adults aged 60 years and over.

We anticipated that there would be few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving people aged 60 years and over. As many of these would be with small numbers of participants, a comprehensive review and meta‐analysis was required. It was also likely that there would be high withdrawal rates through physical illness, adverse effects, and death and it was possible that drop‐out rates would differ significantly between antidepressant treatment and psychological therapies. This review will help to identify the need for further studies.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in preventing the relapse and recurrence of depression in older people.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The review included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), published and unpublished, including cluster‐randomised and cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

Trial participants were aged 60 years or over, of either gender, who were in remission or who had recovered from a depressive episode diagnosed according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Criteria (DSM; APA 1994), International Classification of Diseases (ICD; WHO 1992), Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC; Feighner 1972), Geriatric Mental State (GMS; Copeland 1976), or as defined by trialists. The review included participants treated in a range of settings (inpatients, outpatients, community, care homes) and people with comorbid physical illness. The review also included studies in which some participants were aged under 60 years provided that data from those aged 60 years and over were separately analysed. The review included trial participants with both late‐onset depression (50 years or older) and early‐onset (under 50 years). Trials were included in which all participants had already responded to acute treatment (i.e. all were in continuation and maintenance phases) and trials in which only some participants had already responded.

We excluded trials with participants experiencing bipolar disorder, dementia, and other severe mental disorders.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Any antidepressant. There was no restriction on the dose of antidepressant treatment. All antidepressant drugs were eligible from the following classes.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): amitriptyline, imipramine, trimipramine, doxepin, desipramine, protriptyline, nortriptyline, clomipramine, dothiepin, lofepramine.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): zimelidine, fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram.

Serotonin‐noradrenaline antidepressants (SNRIs): venlafaxine, milnacipram, duloxetine.

Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NASSAs): mirtazapine.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): irreversible: phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid; reversible: brofaramine, moclobemide, tyrima.

Other antidepressants: noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (NARIs): reboxetine, atomoxetine; noradrenaline‐dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): amineptine, buproprion; serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs): trazodone; unclassified antidepressants: agomelatine, vilazodone; other heterocyclic antidepressants: mianserin, amoxapine, maprotiline.

Any psychological therapy. Any structured psychological therapy of any duration was eligible, including the following.

Behavioural therapy: activity scheduling, behaviour modification, psychoeducation.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): problem‐solving therapy, rational emotive therapy, self control.

Third‐wave CBTs: mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behaviour therapy.

Integrative therapies: interpersonal therapy (IPT), cognitive analytical therapy.

Psychodynamic therapies: brief psychological therapies, counter transference, psychoanalytic therapy.

Humanistic therapies: existential therapy, experiential therapy.

We categorised counselling according to the psychological therapy approach used by counselling practitioners.

Comparator interventions

Placebo.

Treatment as usual/waiting list control (provided these did not incorporate any of the excluded interventions).

Antidepressants.

Psychological therapies.

We excluded electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), antipsychotic medication, or lithium used as continuation or maintenance treatments.

We excluded psychological interventions, including systemic and family therapies, in which some recipients of therapy were not the index participant.

We excluded studies in which there was no randomisation to treatment in the continuation and maintenance phase, that is, those in which acute phase treatment was simply continued after remission.

For a list of main planned comparisons, see Data extraction and management.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure for benefit was recurrence rate of depression at 12 months' follow‐up. We defined this as reaching a cut‐off on depression rating scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1996), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS; Hamilton 1960), Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery 1979), or any depression symptom rating scale used by study authors. We defined remission of a depressive illness as depressive symptoms dropping below case level and defined recovery as remission lasting for more than six months. Recurrence was return to case level symptoms during recovery (Frank 1991).

The primary outcome measure for harm was number of participants who had dropped out during the trial at 12 months as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes for benefit were relapse and recurrence rates examined at six‐monthly intervals over the follow‐up period and at the point of final measurement (endpoint). We defined this as reaching a cut‐off on depression rating scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1996), HDRS (Hamilton 1960), MADRS (Montgomery 1979), or any depression symptom rating scale used by study authors. We defined relapse as return to case level symptoms during remission and recurrence was return to case level symptoms during recovery (Frank 1991). We defined remission of a depressive illness as depressive symptoms dropping below case level and defined recovery as remission lasting for more than six months. We included long‐term data after discontinuation of antidepressant medication if available.

Where data were available, we also included the following secondary outcomes.

Global clinical impression by the clinician (Guy 1976).

Global clinical impression by the participant.

Social functioning measured using the Global Assessment of Function scores (Luborsky 1962), or another scale used by the authors.

Quality of life measured using the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) (Ware 1993).

Deaths.

Acceptability

Acceptability was measured through number of participants who dropped out due to drug‐related adverse effects during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants (drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects).

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintains a specialised register of randomized controlled trials, the CCMDCTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies based register with >50% of reference records tagged to c12,500 individually PICO coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of Medline (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the hand‐searching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website with an example of the core Medline search displayed in Appendix 2.

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)

The Group's Information Specialist cross‐searched the CCMDCTR‐Refs and CCMDCTR‐Studies registers (to 13 July 2015) using the following updated search strategy (precision maximizing):

#1 depress*:ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh #2 ((relapse or recurr* or maintenance or continuation or prophyla*) and (recovered or remission or remit* or responder* or "responded to" or "recent* episode" or "recent* depress*" or "previous* depress*" or "previous episode*" or (depress* near2 past))):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh #3 ((continuation or maintenance) near2 (treatment* or *therap* or phase or antidepress* or medicat*)):ti,ab #4 “relapse prevention” or “time to relapse” #5 (aged or elder* or old or older or geriatric or "late* life" or institutional* or "care home*"):ti #6 Aged:kw,ky,sh,emt #7 (#1 and (#2 or #3 or #4) and (#5 or #6))

Key to search fields (Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) platform): ti:title; ab:abstract; kw:keywords;ky:additional keywords; emt:EMTREE headings; MH:MeSH

The Group's Information Specialist also conducted a cited reference search on the Web of Science (WoS) at this time (13‐Jul‐2015) for citations of primary reports of included studies. Results were screened for eligibility and any additional RCTs added to the CCMDCTR search results.

Previous searches to June 2012 can be found in Appendix 1.

2. International trial registers

The World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov were also searched at this time (13‐July‐2015).

Searching other resources

Handsearches

We handsearched the following journals: International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,Journal of the American Geriatrics Association, and International Psychogeriatrics. We screened relevant papers and major textbooks that covered late‐life depression and its treatment. [Date]

Personal communication

We contacted the authors of significant papers and experts in the field for information on any unpublished studies.

Bibliographies

We examined references and bibliographies from relevant trials for further RCTs not identified.

Grey literature

We also searched grey literature, including conference abstracts of the International Psychogeriatrics Association.[Date]

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both review authors independently performed the selection of trials for inclusion in the review by reviewing the titles and abstracts culled by the search strategy. Where a title or abstract appeared to describe a trial eligible for inclusion, we obtained the full‐text article to assess the relevance to this review based on the inclusion criteria. We attempted to resolve any disagreements by discussion. If agreement was not possible, we contacted the principle author of the study for further information to allow inclusion or exclusion. We generated a Cohen Kappa statistic to show level of agreement between the review authors.

Data extraction and management

Both review authors independently extracted data using data extraction forms and evidence tables. We resolved differences by discussion. Both authors managed data entry into Review Manager (RevMan 2014). We analysed included trials for the following characteristics.

Characteristics of the study participants

Age and any other recorded characteristics of participants.

Location of participants.

Methods used to define and diagnose study participants.

Interventions used

Type and stated aim of psychological therapy.

Type of antidepressant medication.

Type of placebo/control/comparison.

Measures

Assessment instruments.

Assessment intervals.

Outcomes

Primary

Relapse of depression.

Recurrence of depressive disorder.

Secondary

Global clinical impression by clinician.

Global clinical impression by the participant.

Social functioning.

Quality of life.

Acceptability:

Overall drop‐out rate.

Drop‐out due to drug‐related adverse effects.

Drop‐out due to death.

When aspects of methodology were unclear, or when the data were in a form unsuitable for meta‐analysis and trials appeared to meet the eligibility criteria, we contacted the principal author for additional information.

Planned comparisons

Antidepressants versus placebo.

Psychological therapies versus placebo or treatment as usual/waiting list.

Antidepressants/psychological therapies combination versus drug placebo.

Antidepressant versus psychological therapies.

Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus antidepressants alone.

Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus psychological therapies alone.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed trial quality using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias. This tool assesses the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, handling of incomplete data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Both review authors independently assessed each paper before agreeing on 'Risk of bias' assessments in each domain. We contacted investigators for additional information in cases of incomplete recording.

We noted methods used for sequence generation and allocation concealment. We recorded methods for blinding participants, therapists, and assessors from treatment type along with evidence of effectiveness. In assessing incomplete outcome data, we assessed each main outcome at each time point for completeness including exclusions and attrition; we assessed methods for addressing incomplete data. To assess selective reporting, we compared stated outcomes with intended outcomes as stated in the methods sections and any available trial protocols.

We made judgements for each domain as high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). When the overall results were significant, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and additional harmful outcome (NNTH), as the inverse of the risk difference (RD).

We presented mean differences (MD) for continuous data. Where necessary, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) from the study authors' CIs for MDs (Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

In trials in which participants were treated individually, the unit of analysis was the participants.

Cluster‐randomised trials

In cluster‐randomised trials, participants in the same treatment group cannot be regarded as independent and an analysis that ignores clustering is likely to underestimate the standard error (SE) of the estimate. If study authors had taken account of clustering and reported data adjusted for possible within‐group correlation, we used the adjusted data in this review. If they did not report adjusted data, we contacted authors to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We analysed data from studies that compared more than two intervention groups using multiple pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups while taking care not to include the same group of participants more than once in the same meta‐analysis.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trails evaluate the effect of experimental intervention compared with control intervention separately for each participant. Cross‐over design is unlikely in continuation and maintenance trials in depression, especially trials of psychological therapies that have carry‐over effects. As this review uses a point‐in‐time analysis comparing interventions at six monthly intervals from randomisation, data from cross‐over trials could not be included.

Dealing with missing data

We obtained missing data from authors, if available.

We performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis in studies where more than 60% of people completed the study. We counted everyone allocated to the intervention, whether they completed the follow‐up or not. We assumed that those who dropped out had a negative outcome, with the exception of death.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic as a test of heterogeneity with results interpreted according to the following broad thresholds:

0% to 40%: may not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: represents considerable heterogeneity.

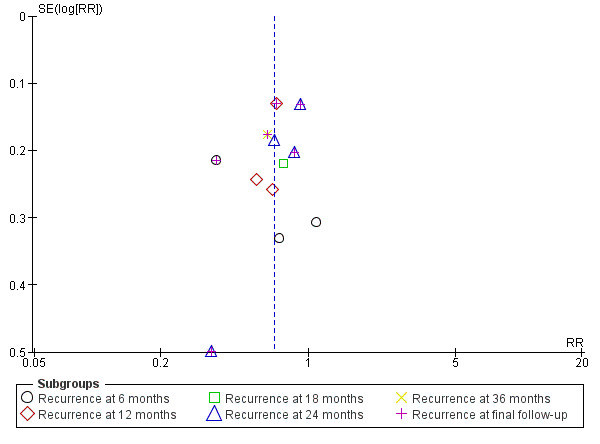

Assessment of reporting biases

We entered data from included studies into a funnel graph in an attempt to identify the likelihood of significant publication bias.

Data synthesis

We calculated the RR using the random‐effects model as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. We inspected data to see if an analysis using a fixed‐effect model would make any substantive difference in outcomes that were not statistically significantly heterogeneous.

Where possible, we attempted to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'depression relapse/recurrence' or 'no relapse/recurrence of depression'. If the authors of a study had used a predefined cut‐off point for determining clinical effectiveness, we used this, where appropriate. Otherwise, we assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score, this was interpreted as being a clinically significant response.

We presented non‐quantitative data descriptively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored clinical heterogeneity, where possible, using the following subgroup analyses.

Early‐onset depressive disorder and late‐onset depressive disorder in continuation and maintenance treatment.

Response to treatment of participants (recovered) versus participants in remission.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to see if the results were affected by methodological decisions made throughout the review process. We undertook the following analyses to test the impact of including studies at high risk of bias.

Removing studies at high risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Removing studies at high risk of bias for blinding.

Removing studies with a drop‐out rate above 20%.

'Summary of findings' table

We produced one 'Summary of findings' table for the two primary outcomes (recurrence and overall drop‐outs) at 12 months' follow‐up in the main comparison of interest, antidepressant versus placebo. There was no separation into high‐risk and low‐risk populations, as this was not possible using available data. We graded outcomes using the GRADE approach and produced the table using GRADEprofiler software (GRADEpro). We based the risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The updated search yielded 10 new records all of which we examined as full‐text articles and excluded as not meeting inclusion criteria. Therefore, the number of included studies remained unchanged from the previous review at seven studies (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009; Wilson 2003).

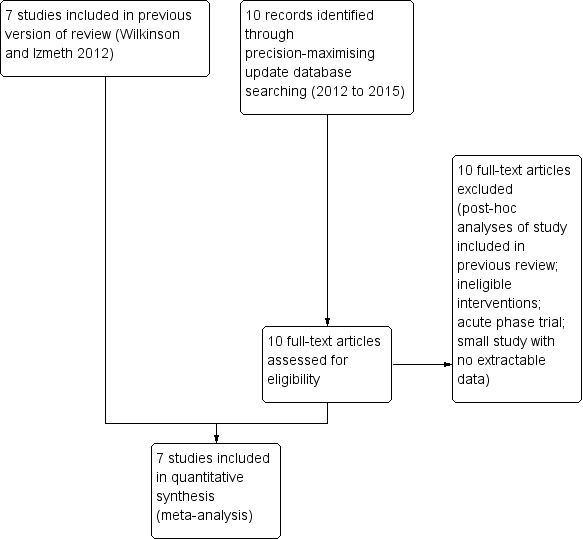

We produced an updated study flow diagram incorporating the studies included in the previous review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram (including studies in previous review version).

Included studies

The review included seven studies. See Characteristics of included studies table.

Types of studies

All seven included studies were of parallel design with participants allocated to therapeutic or control conditions. Four trials were multicentre (Gorwood 2007; OADIG 1993; Wilkinson 2009; Wilson 2003), and three were single centre (Alexopoulos 2000; Klysner 2002; Reynolds 1999a).

Five of the seven trials included two arms and compared antidepressant medication with drug placebo. Two used a TCA (Alexopoulos 2000; OADIG 1993), and three used an SSRI (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; Wilson 2003). One trial included two arms and compared continuation of any acute phase antidepressant with a combination of antidepressant and group CBT (Wilkinson 2009). One trial included four arms and compared a TCA, drug placebo, IPT/drug placebo combination, and TCA/IPT combination (Reynolds 1999a).

Study size varied. One trial randomised 43 participants and another trial randomised 45 participants (Alexopoulos 2000; Wilkinson 2009). One trial randomised 69 participants (OADIG 1993), and three randomised between 107 and 121 participants (Klysner 2002; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). One trial randomised 305 participants (Gorwood 2007).

Types of participants

Diagnoses and measures of depression severity

Two trials required participants to have met DSM‐IV criteria for major depression (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002). One trial used RDC (OADIG 1993), one used both DSM‐IV and RDC (Alexopoulos 2000), one used Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia ‐ Lifetime Version (SADS‐L) (Reynolds 1999a), one used ICD‐10 criteria (Wilkinson 2009), and one used both Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy (AGECAT) and DSM‐III (Wilson 2003).

Five of the trials also required participants to have scored above a cut‐off on a depression rating scale. Three trials used the HDRS (Alexopoulos 2000; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003) and two trials used the MADRS (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002).

Participants in all trials were in remission from depression before randomisation. All trials defined remission as scoring below a cut‐off on a depression rating scale. Four trials used the MADRS with cut‐offs of less than 13 (Gorwood 2007), less than 12 (Klysner 2002), less than 11 (OADIG 1993), and less than 10 (Wilkinson 2009). Two trials used the 17‐item HDRS with a cut‐off of less than 11 (Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). One trial used the 24‐item HDRS with a cut‐off of less than 11 as well as the Cornell rating scale for depression with a cut‐off of less than 7 (Alexopoulos 2000). Two of the trials also required participants no longer to meet the diagnostic criteria for depression used for entry to the study (Alexopoulos 2000; Wilkinson 2009). In all trials, participants were required to have been in a stable period of remission before randomisation. In the majority of trials, the period of remission was 16 weeks. In two trials, the required period of remission was shorter, that is, eight weeks (OADIG 1993) and four weeks (Wilson 2003). One trial required a period of remission of between eight weeks and one year (Wilkinson 2009).

Recruitment source

Four of the seven trials were based in psychiatry clinics in the USA and continental Europe (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; Reynolds 1999a). Authors described two of these clinics as research clinics (Klysner 2002; Reynolds 1999a). The other three trials were based in the UK National Health Service, recruiting people from primary and secondary care (OADIG 1993; Wilkinson 2009; Wilson 2003). Two of these included a proportion of participants who had received inpatient treatment (OADIG 1993; Wilkinson 2009), and one included some participants who had been recruited through a research community survey (Wilson 2003).

Participant characteristics

In keeping with the search strategy used, all participants were aged 60 years and over. Although the search had yielded many trials with adults of all ages that included a proportion of people aged 60 years and over, none of these analysed results separately from older participants and so we excluded all of them from the review. Three of the included trials recruited participants aged 65 years and over (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; Wilson 2003); the remaining trials included participants aged 60 years and over. In six of the trials, the mean age was between 73 and 77 years; in the other trial, the mean was 67 years (Reynolds 1999a). In all trials, the majority of the participants were women. One trial stipulated that participants should have experienced at least one previous episode of major depression within the previous three years (Reynolds 1999a). One trial required participants to have experienced a depressive episode of at least four weeks' duration (Gorwood 2007).

Exclusion criteria

All trials except one (Wilkinson 2009) excluded people with severe or unstable physical illness. All except one (Klysner 2002) used a single measure of cognitive function to exclude people with cognitive impairment. However, the degree of cognitive impairment for exclusion varied considerably between studies. Of six studies using the Folstein Mini Mental State Examination, the lowest cut‐off (representing the greatest degree of cognitive impairment) was 12 (Wilson 2003), and the highest cut‐off (representing the smallest degree of cognitive impairment) was 27 (Reynolds 1999a). Two studies excluded people whose depressive episode had been treated with ECT (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002), and the two studies randomising to TCAs excluded people who were known to be unable to tolerate that class of antidepressant or who had contraindications to their use (OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a).

Three trials excluded people who had been treated for psychotic depression (Gorwood 2007; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). Three trials excluded people who had a history of any other psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002). One trial limited exclusion to bipolar disorder and dysthymia (Reynolds 1999a), and one to bipolar disorder alone (Wilkinson 2009).

Types of intervention

Antidepressant drugs and drug placebo interventions

All trials except one (Wilkinson 2009) involved comparison of active antidepressant treatment with antidepressant placebo. Three of these trials used TCAs. One trial adjusted nortriptyline dose to achieve a plasma level of 60 ng/mL to 150 ng/mL, while people randomised to placebo underwent titration from nortriptyline over a 10‐week period; all participants continued to attend a medication clinic (Alexopoulos 2000). The second trial adjusted nortriptyline dose to achieve a plasma level of 80 ng/mL to 120 ng/mL with people randomised to placebo undergoing a six‐week titration; all participants continued to attend a medication clinic (Reynolds 1999a). In the third trial using TCAs, all participants in the active treatment arm received dothiepin 75 mg daily (OADIG 1993). None of the study authors specified titration arrangements for participants randomised to placebo.

The other three trials comparing active treatment with placebo antidepressant used SSRIs. Gorwood 2007 used escitalopram at 10 mg or 20 mg daily, according to the dose required during active treatment. Participants randomised to receive placebo underwent direct switch from escitalopram 10 mg daily or titration over one week from 20 mg daily. Klysner 2002 used citalopram at 20 mg, 30 mg, or 40 mg daily, according to the dose required during acute treatment; they did not specify titration procedures for participants randomised to placebo. Wilson 2003 used sertraline at a dose of 50 mg, 100 mg, or 150 mg daily according to the dose used in the acute phase treatment except with participants who had required a dose of 200 mg in the acute phase who had this reduced to 150 mg. They did not specify titration procedures for participants randomised to placebo.

Reynolds 1999a compared nortriptyline at a plasma level of 80 ng/mL to 120 ng/mL and medication clinic attendance with nortriptyline titrated for four weeks after randomisation to achieve a lower plasma level of 40 ng/mL to 60 ng/mL with medication clinic attendance. In Wilkinson 2009, all participants in both arms continued to receive whichever antidepressant had been used in their acute phase treatment.

Types of psychological therapies

Only two trials included psychological therapies. One trial used IPT (Reynolds 1999a). Treatment sessions were delivered on a monthly basis throughout the whole period of follow‐up, that is, for three years or until recurrence or drop‐out. Reference is made to use of a therapy manual. The other trial to involve a psychological therapies used eight sessions of group CBT over a fixed 12‐week period (Wilkinson 2009). This was a standardised therapy using a treatment manual and therapy homework, including usual cognitive behavioural techniques of activity scheduling, thought monitoring, and thought challenging.

Process evaluation of psychotherapeutic evaluation

Reynolds 1999a audiotaped IPT sessions and rated them for treatment integrity and compliance with the treatment manual. Although not explicitly stated, a reference indicated that a rating tool was used (Wagner 1992), although compliance ratings are not given. Wilkinson 2009 videotaped group CBT sessions and rated a 25% sample for therapy quality and adherence to the treatment manual using a modified version of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (Blackburn 2001). All sessions achieved the predetermined level of therapy competence, apart from the sessions from the first group treated.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcome measures were rates of recurrence of depression using predetermined cut‐offs on different depression rating scales, diagnostic criteria, or clinical judgement. One study used the 17‐item HDRS requiring a score of 13 or more (Wilson 2003). Another study used the 24‐item HDRS, requiring a score of 17 or more (Alexopoulos 2000). Four studies used the MADRS, two requiring a score of 22 or more (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002), one a score of 11 or more (OADIG 1993), and the other a score of 10 or more (Wilkinson 2009). Three studies also allowed recurrence to be identified by clinical judgement (Gorwood 2007; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a), one by RDC (Alexopoulos 2000), and one by DSM‐IIIR criteria (Wilson 2003).

Secondary outcomes

No study reported long‐term recurrence rates of depression after discontinuation of treatments. One study measured changes in observer‐rated Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (Gorwood 2007). No studies reported social functioning measures or quality of life measures. Six of the seven studies reported death rates; one study did not state death rates (Alexopoulos 2000), but it was apparent that no deaths occurred during follow‐up. One study reported overall drop‐out rates without identifying drop‐outs specifically due to adverse effects and deaths, and the study authors provided no further data (OADIG 1993).

Acceptability

Six of the seven studies reported overall drop‐out rates. One study did not state drop‐out rates, but it was apparent that no drop‐outs occurred during follow‐up (Alexopoulos 2000). Three of the studies reported drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects (Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; Wilson 2003). One study reported overall drop‐out rates without identifying drop‐outs specifically due to adverse effects and deaths, and study authors provided no further data (OADIG 1993).

Excluded studies

The most frequent reason for exclusion of studies was inclusion in trials of participants aged 60 years and over with younger adults, with no separate analysis of data from older participants. We excluded two trials by Reynolds et al., one because it compared two serum levels of the same antidepressant (Reynolds 1999b), and the other because some participants received augmentation with lithium or perphenazine, which was not discontinued at randomisation (Reynolds 2006). See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

We identified no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We identified no ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

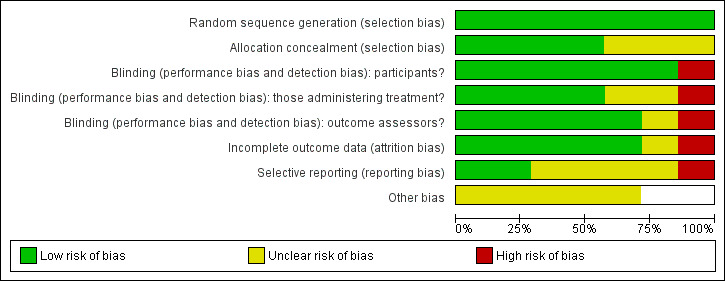

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for summary graphs.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

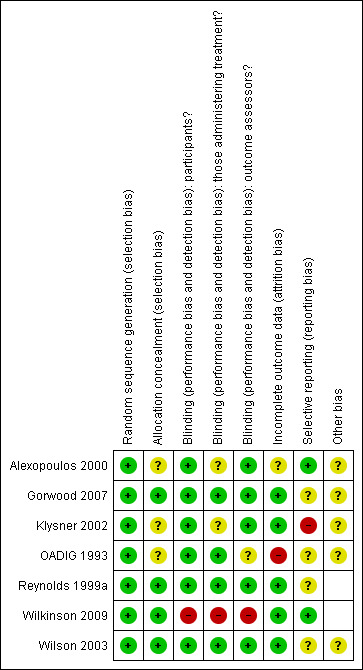

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

All studies used adequate sequence generation. All reported using random allocation, although not all studies stated the randomisation method. Two studies also employed stratification (OADIG 1993; Wilkinson 2009).

Allocation concealment

Four studies used adequate allocation concealment (Gorwood 2007; Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009; Wilson 2003). Allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining studies.

Blinding

Blinding of participants

The six studies that investigated antidepressant medication achieved blinding of participants using placebo arms (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). The two trials involving psychological therapies could not achieve blinding of participants as psychological therapies involve active participation from people receiving the treatment (Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009).

Blinding of those delivering treatment

There was adequate blinding of those delivering treatment in four of the studies (Gorwood 2007; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). Blinding was unclear in two of the studies (Alexopoulos 2000; Klysner 2002). In the two studies with psychological therapy arms, blinding was not possible (Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009).

Blinding of assessors

Blinding of assessors was adequate in five of the studies (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003), and unclear in one (OADIG 1993). Blinding inadequate in Wilkinson 2009 as the study authors report that, during follow‐up assessments, some participants used terms that indicated they had become familiar with CBT, the intervention under investigation, causing unblinding of the assessor.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies addressed incomplete data (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009; Wilson 2003).

Selective reporting

Only one study was free from selective reporting as the study protocol was available to the authors (Wilkinson 2009). There were no other study protocols available so risk of bias in the other six studies was uncertain.

Other potential sources of bias

All seven studies involved antidepressant medication; one involved a range of medications (Wilkinson 2009), while the others involved single agents. Involvement by pharmaceutical companies in trials may introduce bias as companies hold a vested interest in the results. Three studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies (Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Wilson 2003). The funding of Gorwood 2007 was unclear but employees of a pharmaceutical company were among the investigators. The funding of Alexopoulos 2000 was also unclear. Independent grant‐giving bodies funded the remaining studies (Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009).

Six of the seven studies involved titration from active antidepressant to placebo antidepressant (Alexopoulos 2000; Gorwood 2007; Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Reynolds 1999a; Wilson 2003). This can introduce bias through carry‐over therapeutic effects if titration is slow, or by discontinuation symptoms if titration is rapid. Two studies described gradual tapering of antidepressant dose under double‐blind conditions; in one study, this was over 10 weeks (Alexopoulos 2000), and in the other study was over six weeks (Reynolds 1999a). In Gorwood 2007, participants randomised to receive placebo underwent direct switch from escitalopram 10 mg daily or titration over one week from escitalopram 20 mg daily. The remaining studies did not state the procedures for titration (Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993; Wilson 2003).

Two trials included delivery of psychological treatments (Reynolds 1999a; Wilkinson 2009). Poor treatment fidelity is a potential source of bias in psychological treatment trials. However, both trials used psychological therapists with high levels of training and included supervision in the relevant therapy (IPT (Reynolds 1999a) and group CBT (Wilkinson 2009)). Both trials also used a therapist competency scale to measure treatment fidelity. Therefore, this potential source of bias was low in these studies.

Studies reported different drop‐out rates. Higher rates of drop‐out may occur in people taking active medication and experiencing adverse effects, leading to bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We performed intention‐to‐treat analyses in all comparisons.

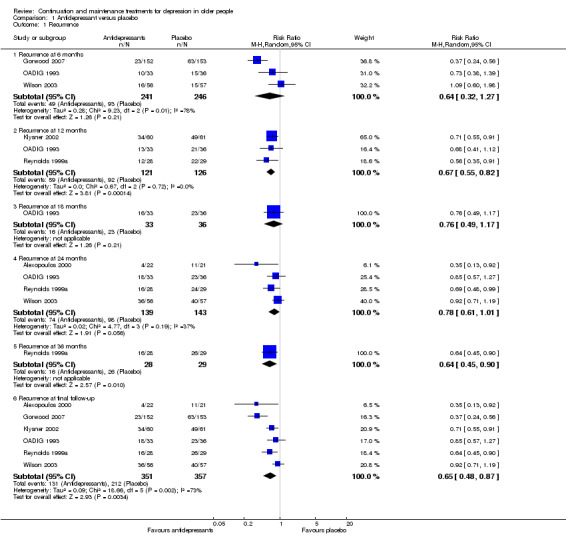

1. Antidepressants versus placebo

Primary outcomes

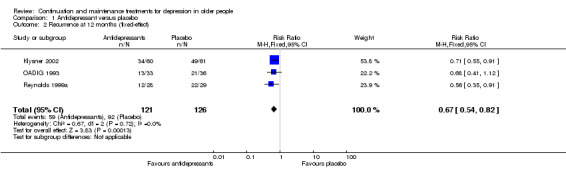

1.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

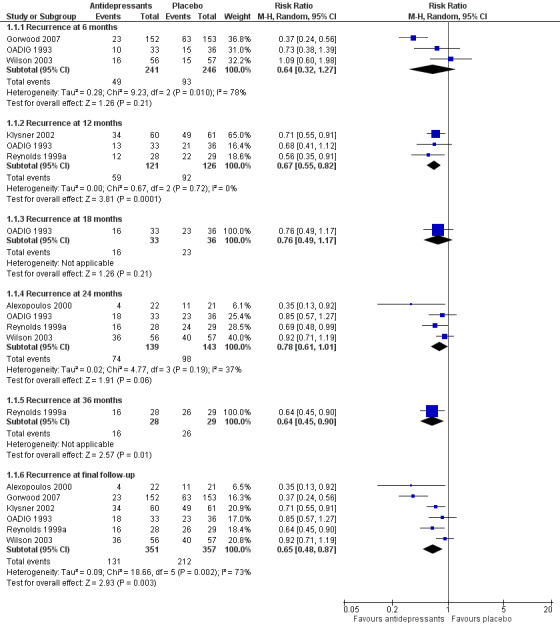

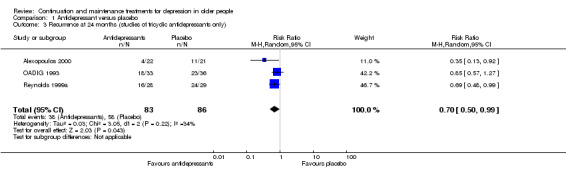

There was a statistically significant difference favouring antidepressants in reducing recurrence at 12 months compared with placebo (three RCTs, n = 247, RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.82) (Figure 4). This translated to an NNTB of 5. Fixed‐effect modelling found the same effect. We downgraded the outcome from high to low quality of evidence due to imprecision and risk of bias.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antidepressant versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Recurrence.

1.2 Overall drop‐out rates at 12 months

There was no difference in drop‐out rates at 12 months (one RCT, n = 121). We downgraded the outcome from high to low quality of evidence due to imprecision.

Secondary outcomes

1.3 Relapse/recurrence rates of depression at other time points

There was no significant reduction in relapse rates at six months in people taking antidepressants compared with people taking placebo (three RCTs, n = 487; Figure 4). There was a high degree of heterogeneity between the three trials in this analysis (I2 = 78%), the possible reason being that two of the trials used a lower cut‐off to determine relapse, and they included people from secondary care (who had probably been more severely depressed) (OADIG 1993; Wilson 2003). Excluding these two trials from the analysis resulted in a significant benefit of antidepressant treatment in the one remaining trial (Gorwood 2007).

There was no significant reduction in recurrence rates at 18 months in people taking antidepressants compared with people taking placebo in the one trial yielding data (one RCT, n = 69; Figure 4).

There was no significant reduction in recurrence rates at 24 months in people taking antidepressants compared with people taking placebo (four RCTs, n = 282; Figure 4). There was a moderate degree of heterogeneity between the four trials in this analysis (I2 = 37%), with one trial being an outlier (Alexopoulos 2000). When we removed this trial from the analysis, the heterogeneity was reduced (I2 = 0%) but the result remained insignificant.

In the three trials of TCAs, antidepressant treatment was superior to placebo at 24 months.

There was a significant difference favouring the antidepressant group in reducing recurrence at 36 months compared with placebo in the one trial reporting data at 36 months (n = 57, RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 4). This translated to an NNTB of 4. Participants in this trial were generally younger, less cognitively impaired, and experienced less physical illness than participants in other trials in the review.

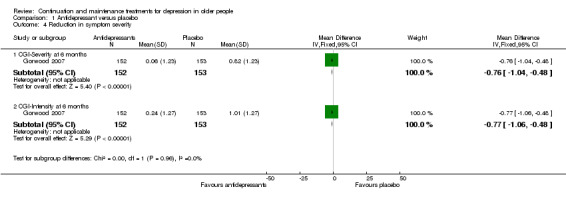

1.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

One study presented continuous data measuring changes in observer‐rated CGI (n = 305; Gorwood 2007) as MDs using SDs calculated from the study authors' CIs for MDs (Higgins 2011). There was no significant difference in symptom severity between antidepressant and placebo at six months.

1.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on global clinical impression by the participant.

1.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

1.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

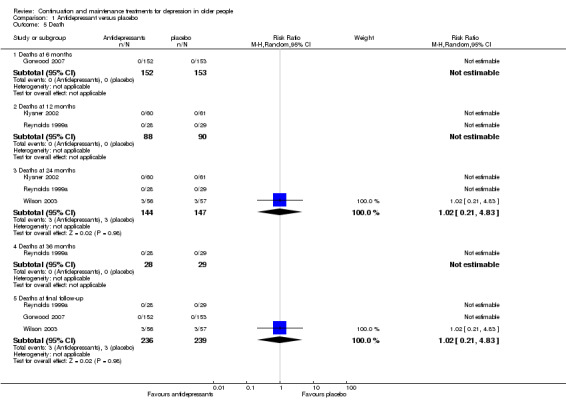

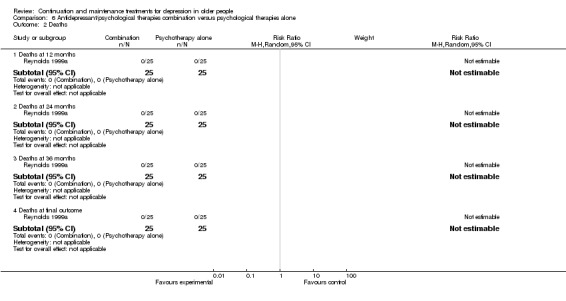

1.8 Deaths

Comparison of death rates was possible for antidepressant versus placebo at 24 and 36 months, and antidepressant versus combination of antidepressant and psychological therapies at six and 12 months. There were no significant differences in any of these analyses.

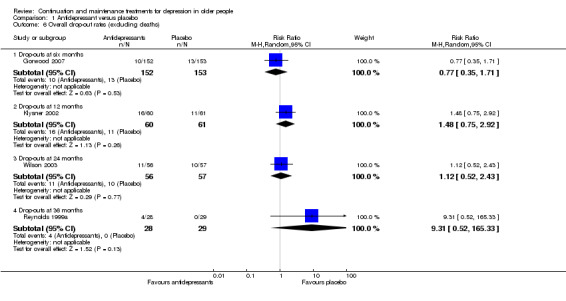

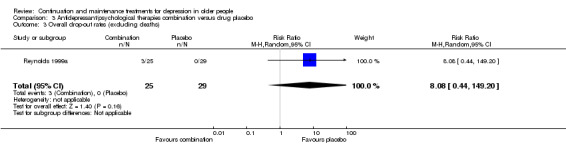

1.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rates at other time points

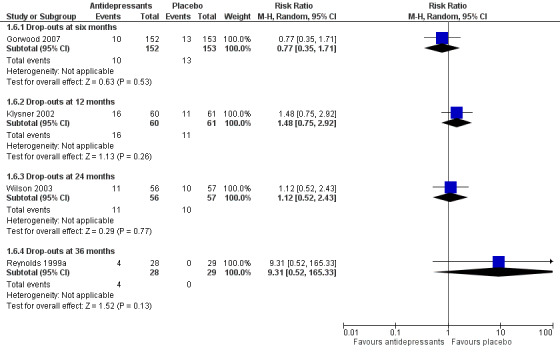

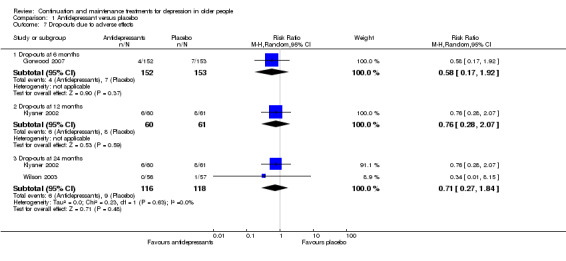

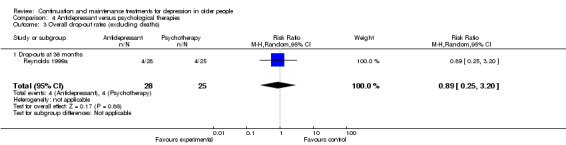

Comparison of overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) was possible for antidepressant medication versus placebo at six months (one RCT, n = 305), 24 months (one RCT, n = 113), and 36 months (one RCT, n = 57). There were no significant differences (Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antidepressant versus placebo, outcome: 1.6 Overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths).

1.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

There were no significant differences in drop‐outs due to drug‐related adverse effects in the analyses at six months (one RCT, n = 305), 12 months (one RCT, n = 121), or 24 months (one RCT, n = 234). Only one trial reported qualitative data on adverse effects encountered at a statistically greater frequency with antidepressant (citalopram) than with placebo (Klysner 2002). These were increased sweating, tremor, and fatigue.

2. Psychological therapies versus placebo or treatment as usual/waiting list

Primary outcomes

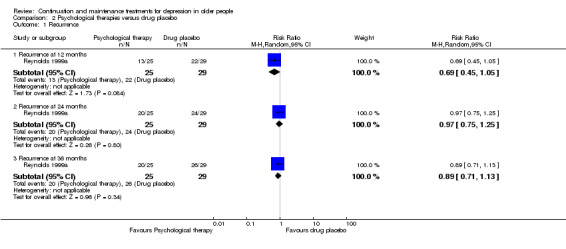

2.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

In the one trial comparing psychological therapies (IPT) with placebo medication (n = 54; Reynolds 1999a), there was no significant difference in recurrence at 12 months.

2.2 Overall drop‐out rate at 12 months

We found no data on overall drop‐out rate at 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

2.3 Relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points

In the one trial comparing psychological therapies (IPT) with placebo medication (n = 54; Reynolds 1999a), there was no significant difference in recurrence at 24 months.

In the one trial comparing psychological therapies (IPT) with placebo medication (n = 54; Reynolds 1999a), there was no significant difference in recurrence at 36 months.

2.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

We found no data on global clinical impression by the clinician.

2.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on global clinical impression by the participant.

2.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

2.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

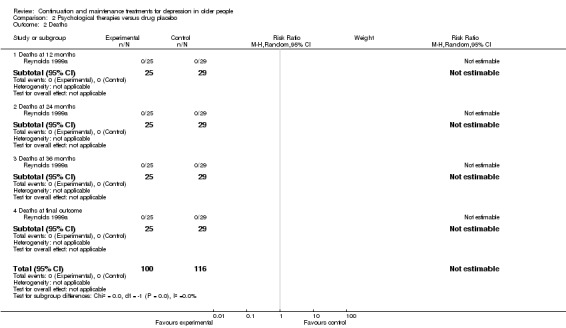

2.8 Deaths

We found no data on deaths.

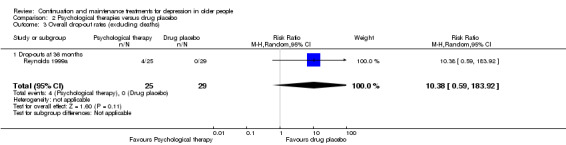

2.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rate

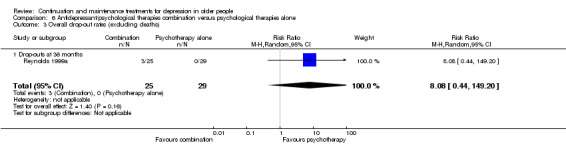

One study yielded data to compare overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) at 36 months in the comparisons of antidepressant versus psychological therapies, psychological therapies versus placebo, and combination of antidepressant and placebo versus psychological therapies alone (n = 54; Reynolds 1999a). There were no significant differences in any of these three comparisons.

2.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

We found no data on drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects.

3. Antidepressants/psychological therapies combination versus drug placebo

Primary outcomes

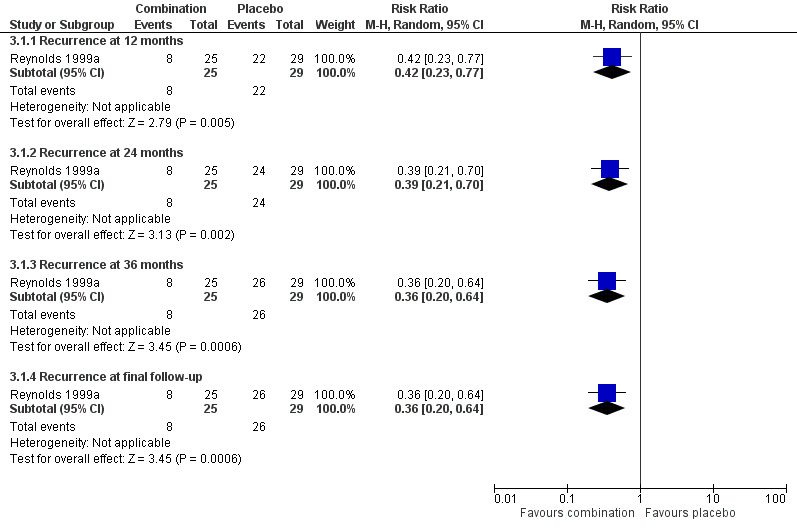

3.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

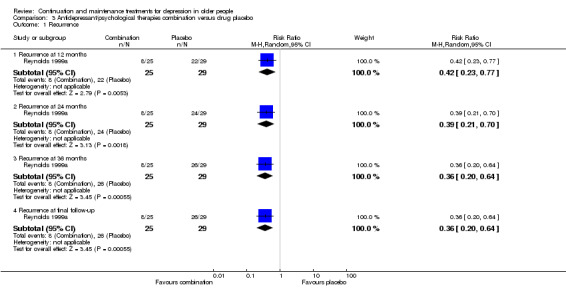

There was a significant difference at 12 months favouring combination in the one trial comparing antidepressant/psychological therapies combination with drug placebo alone (n = 54, RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.77; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 6).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 7 Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus drug placebo, outcome: 7.1 Recurrence.

3.2 Overall drop‐out rate at 12 months

There was no significant difference in overall drop‐out rate at 12 months (one RCT; n =54).

Secondary outcomes

3.3 Relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points

There was a significant difference at 24 months favouring combination in the one trial comparing antidepressant/psychological therapies combination with drug placebo alone n = 54, RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.70; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 6).

There was a significant difference at 36 months favouring combination in the one trial comparing antidepressant/psychological therapies combination with drug placebo alone (n = 54, RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.64; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 6).

3.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

We found no data on global clinical impression by the clinician.

3.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on global clinical impression by the participant.

3.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

3.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

3.8 Deaths

We found no data on deaths.

3.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rate at other time points

Comparison of overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) was possible for combination of antidepressant and psychological therapies with placebo at six, 12, and 24 months, with no significant differences found (one RCT; n =54).

3.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

We found no data on drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects.

4. Antidepressant versus psychological therapies

Primary outcomes

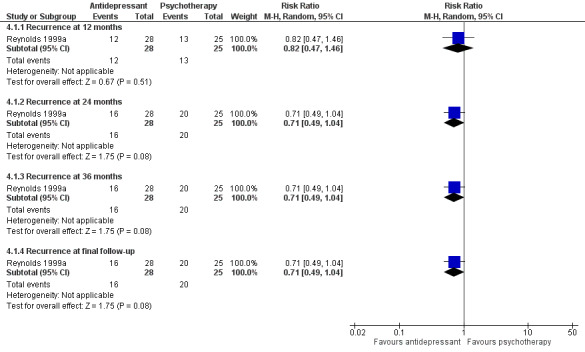

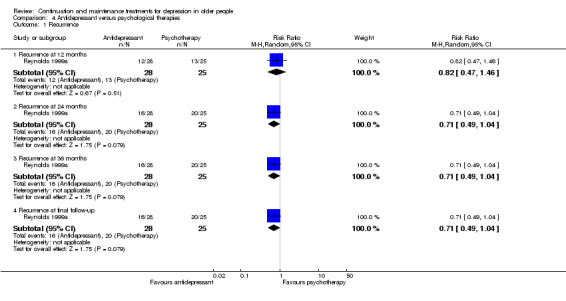

4.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

There was no significant difference in recurrence rates at 12 months in people taking an antidepressant compared with people receiving psychological therapies in the one trial comparing recurrence rate of depression at 12 months (n = 53, RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.46; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 7).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Antidepressant versus psychological therapies, outcome: 2.1 Recurrence.

4.2 Overall drop‐out rate at 12 months

We found no data on overall drop‐out rate at 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

4.3 Relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points

There was no significant difference in recurrence rate at 24 months in people taking an antidepressant compared with people receiving psychological therapies in the one trial comparing relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points (n = 53, RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.04; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 7).

4.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

We found no data on global clinical impression by the clinician.

4.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on global clinical impression by the participant.

4.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

4.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

4.8 Deaths

We found no data on deaths.

4.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rate

One study yielded data to compare overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) at 36 months in the comparisons of antidepressant versus psychological therapies, psychological therapies versus placebo, and combination of antidepressant and placebo versus psychological therapies alone (n = 54; Reynolds 1999a). There were no significant differences in any of these three comparisons.

4.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

We found no data on drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects.

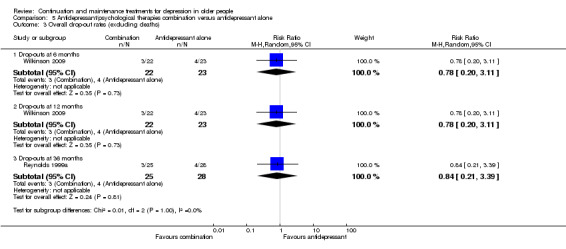

5. Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus antidepressants alone

Primary outcomes

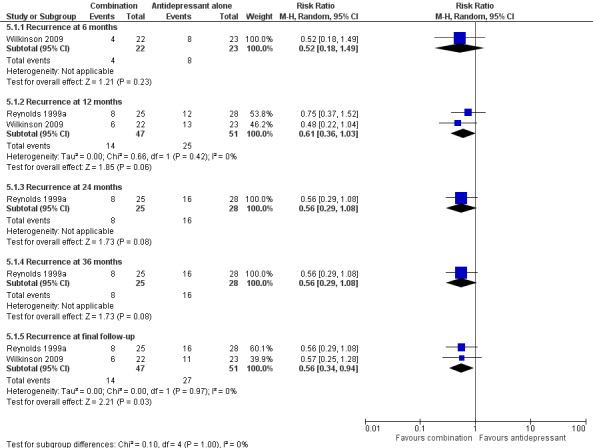

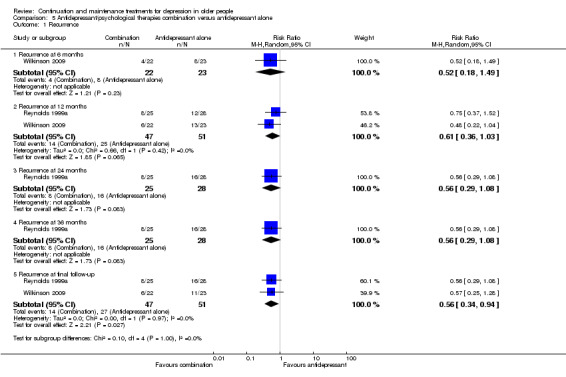

5.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

There was no significant difference in recurrence at 12 months in people receiving antidepressant/psychological therapies combination compared with people receiving antidepressant alone. There were two trials in this analysis (n = 98) with low heterogeneity (Figure 8). This analysis also included data from Wilkinson 2009, which the study authors adjusted for clustering.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus antidepressant alone, outcome: 5.1 Recurrence.

5.2 Overall drop‐out rates at 12 months

We found no data on overall drop‐out rates at 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

5.3 Relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points

In the one trial reporting relevant data, there was no significant reduction in relapse at six months in people receiving antidepressant/psychological therapies combination compared with people receiving antidepressant alone (n = 45; Wilkinson 2009) (Figure 8). This was a group‐based intervention; the study authors adjusted the calculation of RR to allow for clustering.

In the one trial reporting data, there was no significant reduction in recurrence at 24 months in people receiving antidepressant/psychological therapies combination compared with people receiving antidepressant alone (n = 53; Figure 8).

In the one trial reporting data, there was no significant reduction in recurrence at 36 months in people receiving antidepressant/psychological therapies combination compared with people receiving antidepressant alone (n = 53; Figure 8).

5.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

We found no data on global clinical impression by the clinician.

5.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on Global clinical impression by the participant.

5.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

5.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

5.8 Deaths

Comparison of death rates was possible for combination of antidepressant and psychological therapy versus antidepressant alone at six months (one RCT, n = 45), 12 months (two RCTs, n = 98), 24 months (one RCT, n = 53), and 36 months (one RCT; n = 53). There were no significant differences in any of these analyses.

5.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rate

We found no data on overall drop‐out rate.

5.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

We found no data on drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects.

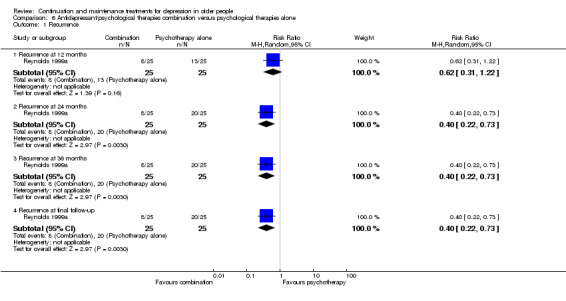

6. Antidepressants/psychological therapies combination versus psychological therapies alone

Primary outcomes

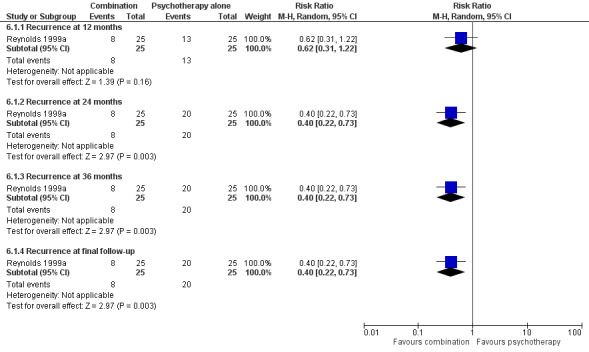

6.1 Recurrence rate of depression at 12 months

In the one trial comparing the combination of psychological therapies and antidepressant with psychological therapies (IPT) alone, combination was not superior to psychological therapies alone at 24 months (n = 50, RR 0.62, 96% CI 0.31 to 1.22; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 9).

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus psychological therapies alone, outcome: 6.1 Recurrence.

6.2 Overall drop‐out rate at 12 months

We found no data on overall drop‐out rate at 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

6.3 Relapse/recurrence rate of depression at other time points

In the one trial comparing the combination of psychological therapies and antidepressant with psychological therapies (IPT) alone, combination was superior to psychological therapies at 24 and 36 months (n = 50, RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.73; Reynolds 1999a) (Figure 9).

6.4 Global clinical impression by the clinician

We found no data on global clinical impression by the clinician.

6.5 Global clinical impression by the participant

We found no data on global clinical impression by the participant.

6.6 Social functioning

We found no data on social functioning.

6.7 Quality of life

We found no data on quality of life.

6.8 Deaths

We found no data on deaths.

6.9 Acceptability: overall drop‐out rate

One study yielded data to compare overall drop‐out rates (excluding deaths) at 36 months in the comparisons of antidepressant versus psychological therapies, psychological therapies versus placebo, and combination of antidepressant and placebo versus psychological therapies alone (Reynolds 1999a). There were no significant differences in any of these three comparisons.

6.10 Acceptability: drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects

We found no data on drop‐out rates due to drug‐related adverse effects.

Subgroup analyses

It was not possible to perform either of the a priori subgroup analyses as the required data were not reported.

Sensitivity analyses

In the original review, we performed two a priori sensitivity analyses of recurrence rates in studies comparing antidepressant with placebo, on the basis of risk of bias in studies. In the first sensitivity analysis, we omitted the studies with unclear allocation concealment (Alexopoulos 2000; Klysner 2002; OADIG 1993), which produced no change in significant findings. In the second sensitivity analysis, we omitted the one study with inadequate blinding of assessors (Wilkinson 2009), which produced no change in significant findings.

We performed three additional sensitivity analyses in the original review. In the first, we removed Alexopoulos 2000 (as an outlier) from the analysis of recurrence rates in studies comparing antidepressant with placebo; this did not affect the overall findings. In the second, we removed Reynolds 1999a from the analysis (on the basis of younger age of participants); this did not affect the overall findings. In the third, we removed Klysner 2002 from the analysis of recurrence rates as the only study with a drop‐out rate of over 20%; this did not affect the overall findings.

In this update, we performed further sensitivity analyses in response to feedback on the original review (received 20 April 2015). These analyses were to assess the effect of excluding drop‐outs from recurrence rates in Reynolds 1999a. The study authors used censoring of drop‐outs for their survival analysis whereas this review used the more conservative intention‐to‐treat for point‐in‐time analysis. We assumed that all drop‐outs had occurred during year one of follow‐up as the study authors were unable to provide exact timings of the drop‐outs. The sensitivity analyses produced no changes in significant findings except in comparison six (antidepressants/psychological therapies combination versus psychological therapies alone) where the combination of antidepressant and psychological therapy became superior to psychological therapy alone at 12 months, in the one study making this comparison.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This updated review was based on data from seven studies from which six comparisons were possible, involving 803 participants. Six of the studies compared continuation/maintenance antidepressant treatment with placebo. Only two studies involved psychological therapies. Both of these examined the effect of psychological therapies in combination with antidepressant medication compared with medication alone and one also compared the combination with both psychological therapies alone and placebo alone. Follow‐up intervals varied between the studies from six to 36 months.

Antidepressants versus placebo

Results for the primary outcomes are shown in Table 1.

Six trials involving 708 participants compared continuation/maintenance antidepressant treatment with placebo, three trials using TCAs and three using SSRIs. Continuation/maintenance antidepressant medication reduced risk of recurrence after 12 months with an NNTB of 5. There was marked clinical heterogeneity in the studies and significant numbers of drop‐outs, but the direction of the effect was in favour of antidepressants in all trials. There was no statistically significant risk reduction for recurrence at 24 months when the analysis included all six studies. However, when data from the three trials of TCAs were analysed separately, there was a statistically significant reduction in recurrence risk with an NNTB of 5. It might be assumed that drop‐outs due to adverse effects would be greater with TCAs. However, there were no data that addressed this question as the only trials reporting drop‐outs due to adverse effects separately were the trials of SSRIs.

In the one trial in which participants were followed up for 36 months, maintenance antidepressant medication reduced risk of recurrence after with an NNTB of 5 (Reynolds 1999a). Participants in this trial were relatively young and cognitively unimpaired compared to participants in other trials. In this trial, in addition to outcome assessments, participants receiving placebo also attended medication clinics for physical assessment. For the purpose of this review, we considered this a placebo condition comparable to other studies in this comparison, but the medication clinic contact could be considered as an active treatment component.

Antidepressants versus psychological therapies

Only one trial, involving 53 participants, compared an antidepressant (nortriptyline) with a psychological therapy (IPT). There was no significant difference in terms of recurrence of depression. Therefore, the available data were too limited to allow for any clear conclusion on the comparative efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies. There were no deaths among participants.

Antidepressant/psychological therapies combination versus antidepressant