Abstract

Background

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) precedes the development of invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Current treatment of CIN is quite effective, but there is morbidity for the patient related to pain, bleeding, infection, cervical stenosis and premature birth in subsequent pregnancy. Effective treatment with medications, rather than surgery, would be beneficial.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), including cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors, to induce regression and prevent the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia CIN.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 11, 2013), MEDLINE (November, 2013) and EMBASE (November week 48, 2013). We also searched abstracts of scientific meetings and reference lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled trials of NSAIDs in the treatment of CIN.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risks of bias. Outcome data were pooled using random‐effects meta‐analyses.

Main results

In two RCTs, 41 women over the age of 18 years, in an outpatient setting, were randomised to receive celecoxib 200 mg twice daily by mouth for six months versus placebo (one study, 25 participants) or rofecoxib 25 mg once daily by mouth for three months versus placebo (one study, 16 participants). This second study was discontinued early when rofecoxib was withdrawn from the market in 2004. The trials ran from June 2002 to October 2003, and May 2004 to October 2004. We have chosen to include the data from the rofecoxib study as outcomes may be similar when other such NSAIDs are utilised.

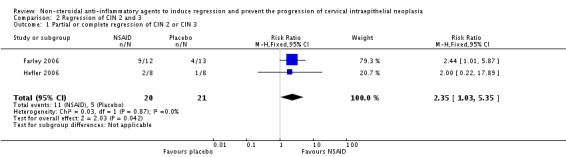

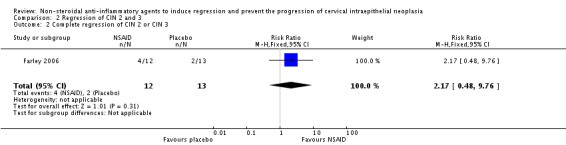

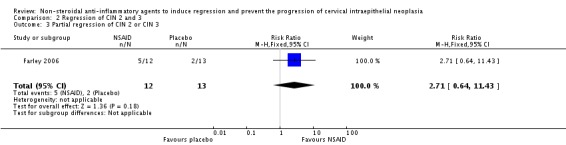

Partial or complete regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in 11 out of 20 (55%) in the treatment arms and five out of 21 (23.8%) in the placebo arms (RR 2.35, 95% CI 1.03 to 5.35; P value 0.04), very low quality evidence). Complete regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in four of 12 (33%) of those receiving celecoxib versus two of 13 (15%) of those receiving placebo (RR 2.17, 95% CI 0.48 to 9.76; P value 0.31, very low quality evidence). Partial regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in five of 12 (42%) of those receiving celecoxib versus two of 13 (15%) of those receiving placebo (RR 2.71, 95% CI 0.64 to 11.43; P value 0.18), very low quality evidence). Progression to a higher grade of CIN, but not to invasive cancer, occurred in one of 12 (8%) of those receiving celecoxib and two of 13 (15%) receiving placebo (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.24; P value 0.4, very low quality evidence). One study reported no cases of progression to invasive cancer within the timeframe of the study. No toxicity was reported in either study. Although the studies were well conducted and randomised, some risk of bias was detected in both studies. Furthermore, the duration of the studies was short, which may mask identifying progression to cancer.

Authors' conclusions

There are currently no convincing data to support a benefit for NSAIDs in the treatment of CIN (very low quality evidence according to GRADE criteria). Results from a large on‐going randomised study of celecoxib are awaited.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Administration, Oral; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/administration & dosage; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Celecoxib; Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia; Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia/drug therapy; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors/administration & dosage; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Disease Progression; Induction Chemotherapy; Induction Chemotherapy/methods; Lactones; Lactones/administration & dosage; Lactones/therapeutic use; Pyrazoles; Pyrazoles/administration & dosage; Pyrazoles/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sulfonamides; Sulfonamides/administration & dosage; Sulfonamides/therapeutic use; Sulfones; Sulfones/administration & dosage; Sulfones/therapeutic use; Uterine Cervical Neoplasms; Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/drug therapy

The treatment of cervical pre‐cancer (CIN) with anti‐inflammatory agents to induce regression and prevent the progression to cervical cancer

Review Questions

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) to cause regression and prevent the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) to cervical cancer. We found only two small studies.

Background

Cervical pre‐cancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: CIN) can progress to invasive cancer of the cervix (neck of the womb). CIN is identified by screening and can be treated with surgery to the cervix, either with destruction of the cells covering the cervix, such as with laser therapy, heating, or freezing, or removal by surgical excision. While this is effective in the majority of cases, the surgery can cause immediate unwanted effects, such as bleeding and infection, or later complications including difficulty with menses due to scarring of the cervix and early (premature) labour.

NSAIDs have been found to prevent the development of cancer of the large bowel and other organs, but with some unwanted side effects, especially on the heart and blood vessels. Although rofecoxib, used in one of these studies, was withdrawn from the market in 2004, it may shed light on the feasibility of treatment with other NSAIDs.

We wanted to discover whether the use of NSAIDs for women with CIN could promote regression or prevent progression to cervical cancer without undue risk or side effects.

Study characteristics

We identified two randomised studies, including 41 women over the age of 18 years, with moderate or severe CIN. The trials ran from June 2002 until October 2003 and between May 2004 and October 2004. One of them was discontinued before it was completed. The women were given either celecoxib or rofecoxib versus a placebo (sugar tablet) daily by mouth for a period of three to six months.

Key Results

There were far too few women involved in the trials to be able to show whether NSAIDs had a helpful effect in causing regression of CIN. No patients progressed to invasive cervical cancer, and no unwanted effects of the NSAID tablets were reported, but the number of women in the studies would have been too small to detect an adverse effect.

Quality of the evidence

While both studies appear to have been conducted well, there are some questions related to the quality of evidence in relation to concealment and women dropping out of the study before completion of assigned medications. There was insufficient information to assess accuracy of the reporting of information. It is possible that there are other incomplete and unreported studies that have not been identified.

Conclusion

There is insufficient data at this time to support the use of NSAIDs to cause regression or prevent progression of CIN to cervical cancer.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

| Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) compared with placebo for CIN 2 or CIN 3 | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with CIN 2 or CIN 3 Settings: outpatient Intervention: celecoxib 200 mg by mouth, twice daily for six months or rofecoxib 40 mg by mouth, daily for three months Comparison: placebo tablet by mouth, daily for three to six months | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3 | 154 per 1000¹ | 333 per 1000 | RR 2.17 (0.48 to 9.76) | 25 (one study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| Partial or complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3 | 238 per 100² | 550 per 1000 | RR 2.35 (1.03 to 5.35) | 41 (two studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| Progression of CIN to a higher grade of CIN | 167 per 1000¹ | 77 per 1000 | RR 0.54 (0.06 to 5.24) | 25 (one study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹ The basis for the assumed risk is from the spontaneous complete regression rate in the placebo arm of Farley 2006

² The basis for the assumed risk is from the combined spontaneous partial or complete regression rates in the placebo arms of Farley 2006; Hefler 2006

Given the paucity of data in the included studies, the small sample size, and the limitations from early study closure, we have downgraded the quality of the evidence to very low quality.

Background

Description of the condition

Invasive carcinoma of the cervix is the most common cancer in women in developing countries with more than 500,000 cases diagnosed worldwide each year (Ferlay 2010). It is preceded by cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), which can be detected on cervical cytology smears (Papanicolaou test, also called Pap smear, Pap test or smear test) taken as part of screening programmes. Treatment of CIN is effective at reducing, but not eliminating, the risk of subsequent invasive carcinoma (Soutter 1997). However, the cost of treatment of CIN and follow‐up is high, and the surgery involved can have short‐ and long‐term adverse effects (Arbyn 2008; Martin‐Hirsch 2010).

Description of the intervention

The family of agents called non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), including aspirin, ibuprofen, indomethacin, naproxen, piroxicam, and sulindac (Fischer 2011), are able to block both cyclooxygenase (COX) ‐1 and ‐2 enzymes. Selective COX‐2 inhibitors such as celecoxib, rofecoxib and valdecoxib specifically interfere with COX‐2. These agents can be taken orally.

How the intervention might work

COX enzymes catalyse the rate‐limiting step in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and other eicosanoids (DeWitt 1991). COX‐1 is involved in homeostatic functions such as gastrointestinal cytoprotection and is constitutively expressed in most tissues, whereas COX‐2 is rapidly induced after stimulation of quiescent cells by growth factors and also by oncogenes, carcinogens and tumour‐promoters (Hia 1992; Hershmann 1996).

Over‐expression of COX‐2 is thought to be a key factor in malignant transformation in many tissues (Mohammed 1999; Lim 2000; Shamma 2000; Shirahama 2000; Shariat 2003; Surh 2005; Tan 2005). Increased levels of COX‐2 protein expression have been reported in malignancies arising in various sites such as the stomach (Lim 2000), breast (Hwang 1998), oesophagus (Shamma 2000), ovary Munkarah 2005, cervix (Ferrandina 2000; Ferrandina 2002; Kulkarni 2001; Ryu 2000) and colon (Eberhart 1994; Soslow 2000).

COX‐2 may play a role in malignant transformation in the cervix. Increased COX‐2 expression is found with higher grades of CIN (Farley 2004; Mitchell 2007). There is increased risk of persistent or recurrent disease when resection margins (following excisional procedures) are positive for the enzyme (Farley 2004). COX‐2 is present in invasive carcinoma (Dursun 2007; Farley 2004; Kim 2005; Kulkarni 2001; Mitchell 2007). In similar fashion to other cancers (Cao 2002; Sobolewski 2010), high levels of expression are associated with poorer prognostic features such as shorter time to first recurrence, decreased survival (Farley 2004; Ferrandina 2000; Ferrandina 2002; Gaffney 2001) increased lymph node metastasis or parametrial invasion (Ryu 2000; Gaffney 2003; Kim 2003) and chemotherapy or radiation resistance (Ferrandina 2000; Kim 2002).

The mechanism of the effect on the development of tumours is still being investigated, but it has already been shown that increased expression of COX‐2 will inhibit apoptosis (Tsujii 1995), promote angiogenesis (Tsujii 1998), and enhance the invasiveness of malignant cells (Tsujii 1997). It has been hypothesised that over‐expression of COX‐2 could impair host immune responses (Huang 1998; Pockaj 2004) partly because COX‐2 inhibitors reverse tumour‐associated immunosuppression (Huang 1998; Stolina 2000).

The inhibition of the prostaglandin biosynthetic cascade by NSAIDs has been demonstrated to modulate carcinogenesis in both human and animal epithelial tissues (Kelloff 1996). Selective COX‐2 inhibitors suppress tumorigenesis in experimental models of colon, bladder, breast, prostate, stomach, skin cancer and lung cancers (Elmets 2010; Fischer 1999; Fischer 2011; Harris 2000; Kawamori 1998; Liu 2000; Narisawa 1981; Okajima 1998; Reddy 2000.

One of the proposed benefits of selective COX‐2 inhibitors was a reduction of significant gastrointestinal toxicity related to blocking of COX‐1 from non‐selective NSAIDs (Psaty 2006). While this is true, COX‐2 inhibition is unfortunately associated with other adverse effects, principally related to inhibition of the production of prostacyclin in the arterial endothelial and smooth muscle cells (Grosser 2006). In two large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomas, cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure, and death) were increased 12.7% in patients taking celecoxib, and reduced by 4.4% in those taking aspirin (Arber 2006; Bertagnolli 2006; Psaty 2006). These patients had a median age of 59 to 61, were treated for relatively long periods of time (one to three years) and many had pre‐existing cardiovascular disease. While these patients represent a different population than most who would be treated for CIN, cardiovascular events remain a concern with the use of COX‐2 inhibitors. Rofecoxib, a COX‐2 inhibitor which was used by one of the studies in this review, was withdrawn from the market in 2004 for such concerns.

It should be noted that many women may experience regression of CIN without treatment: CIN 2 regression is estimated in around 50% of women within 6 months (Bleecker 2014) and CIN 3 regression in approximately 30% of women within 6 months. In a RCT investigating medical treatment for CIN 2/CIN 3, 31% in the placebo arm had complete histologic regression in 6 months (Follen 2001) whilst in another similar study 32% of CIN 2/CIN 3 lesions regressed to a lower level of CIN in 3 months without treatment (Alvarez 2003). Differences in regression may be related to the subtype of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) as HPV‐16 and HPV‐33 are less likely to be spontaneously cleared and more likely to progress to higher CIN (Jaisamrarn 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

The potential use of NSAIDs, including COX‐2 inhibitors, to induce regression or prevent the progression of CIN to invasive carcinoma is an exciting prospect. To our knowledge, no recent systematic review has been published that specifically addresses this subject.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of NSAIDs, including cyclooxygenases inhibitors, to induce regression and prevent the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or non‐RCTs.

Studies were considered only if they included details of how the grading of CIN was determined. The gold standard for follow‐up of CIN includes cervical cytology, colposcopy and biopsy, where indicated. However, studies were accepted for review with cytologic assessment only. Progression was defined as elevation of the grade of dysplasia by at least one grade (CIN 1 to 2, CIN 2 to 3 and CIN 3 to invasive disease). Regression was defined as reduction in the grade of dysplasia by at least one grade (CIN 3 to 2, CIN 2 to 1, and CIN 1 to no dysplasia).

Types of participants

Women 18 years of age and over with an initial diagnosis of CIN.

Types of interventions

Treatment with non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents, including COX‐2 inhibitors alone, by any route in an outpatient setting.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Progression of CIN to higher grades of CIN.

Progression of CIN to invasive carcinoma

Regression of CIN

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events related to treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for papers in all languages and planned to have them translated as necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Specialised Register of the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group (CGCRG), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 11) (see Appendix 1); the non‐trials database of the CGCRG; MEDLINE (1946 up to Novemeber, 2013) (see Appendix 2); and EMBASE (1980 up to 2013, week 48) (see Appendix 3).

We used the 'related articles' feature in PubMed to identify all relevant articles. We carried out a further search for newly published articles.

The most recent search was executed by the authors.

Searching other resources

We carried out an electronic search of abstracts presented to the annual or biennial meetings of the following organisations: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists, International Gynecological Cancer Society, European Society of Gynecologic Cancer, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology by reviewing their respective online journals of Gynecologic Oncology, The International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Journal of Lower Genital Tract Diseases and Journal of Clinical Oncology from 2000 to 2013.

We searched the following for ongoing trials.

Metaregister (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/rct).

Physicians Data Query (http://www.nci.nih.gov).

http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

Handsearching

We checked the references from published studies to identify additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

The methodology of the review was based on the guidelines stated in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (Higgins 2011).

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching and removed duplicates. Three reviewers (originally OMS and CWH, and recently SMG and CWH) examined the remaining references independently. We excluded those studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (originally OMS and CWH, and recently SMG and CWH) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved papers. The review authors resolved disagreements by discussion. There was no disagreement that required resolution from a third review author. We documented reasons for exclusion.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (originally OMS and CWH, and recently SMG and CWH) searched the titles and abstracts from the initial computerised searches for potential trials to include. The review authors then independently assessed the full text of these provisionally included studies to determine whether a study met the inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreement by consensus.

Data extraction and management

We analysed the included studies for data on:

Author, year of publication and journal citation (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design, methodology

-

Study population

Total number enrolled

Patient characteristics

Age

Co‐morbidities

Other baseline characteristics

-

Intervention details

Patients receiving NSAIDs of any type or route for the purposes of CIN treatment were considered in the intervention group

-

Comparison

Patients used as the controls in the selected studies (not receiving NSAIDs) were used as the comparison

Risk of bias

Duration of accrual

Compliance

Duration of follow‐up

Outcomes: For each outcome we extracted the outcome definition

Results: We extracted the number of participants allocated to each intervention group, the total number analysed for each outcome, and the missing participants

If reported, we extracted both unadjusted and adjusted statistics.

Where possible, all data extracted was relevant to an intention‐to‐treat analysis, in which participants are analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

Three review authors (initially OMS and CWH and later SMG and CWH) independently extracted data onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. Differences between review authors were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in included RCTs using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool and the criteria specified in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This included assessment of the following domains.

Selection bias: Random sequence generation and allocation concealment

Performance bias: Blinding of participants and personnel (patients and treatment providers)

Detection bias: Blinding of outcome assessment

Attrition bias: Incomplete outcome data. We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the study and considered greater than 20% attrition to be at a high risk of bias

Reporting bias: Selective reporting of outcomes

Other possible sources of bias

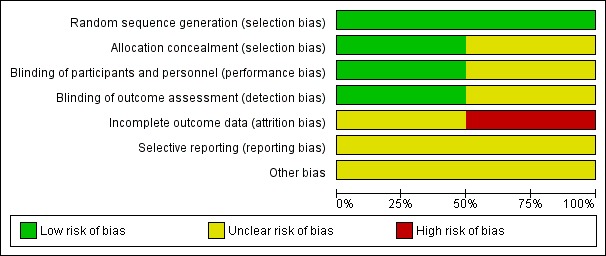

Three review authors (initially OMS and CWH and later SMG and CWH) applied the 'Risk of bias' tool (Appendix 4) independently and differences were resolved by discussion. We have presented results in a 'Risk of bias' summary graph (Figure 1) and interpreted the results of the meta‐analyses in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Figure 1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment.

For time to event data, we used the hazard ratio, if possible.

For dichotomous outcomes, we used the risk ratio (RR).

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for the primary outcome.

Assessment of reporting biases

Since only two RCTs were identified, we did not examine funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analysis of the primary outcome to assess the potential for small study effects such as publication bias.

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.2 software (RevMan 2012). Where appropriate, we pooled results of comparable trials using a random‐effects model. We reported results as RRs or odds ratios (ORs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We performed the meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5.2 (RevMan 2012).

Results

Description of studies

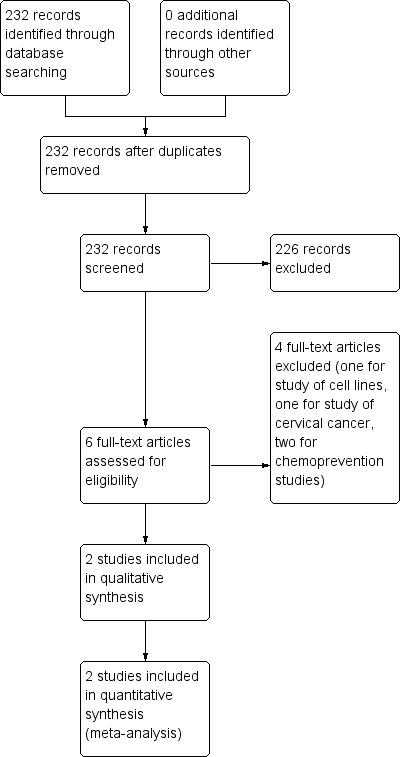

Results of the search

The search strategy identified references which we screened by title and abstract in order to identify studies as potentially eligible for the review. From 232 unique references, we identified six articles as potentially eligible for the review. Following the full text screening of these six articles, we excluded four for the reasons described in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. The remaining two RCTs met the inclusion criteria and are described in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'. We did not identify any additional relevant studies fro the ancillary searches. A further RCT has been completed within a co‐operative research group but has not yet been published. No data is available on this (see study flow diagram: Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The two RCTs randomised a total of 41 women; one included 25 women (Farley 2006), and the other 16 women (Hefler 2006). They both used COX‐2 inhibitors. One was performed at the Tripler United States Army Medical Center in Hawaii, USA, and the other at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria. The latter study was closed early when rofecoxib was withdrawn from the market, due to potential toxicity (Hefler 2006). The mean age of the treatment and placebo groups was 23 years ± 4 years and 22.5 years ± 3 years, respectively (overall range 19 to 27 years) (Farley 2006), and 27.1 years ± 3.3 years and 31.2 years ± 5.5 years, respectively (overall range 24 to 36 years) (Hefler 2006). Thirty‐one patients had CIN 2 and 10 had CIN 3. In one study, the treatment group received celecoxib 200 mg twice daily by mouth for six months (Farley 2006), and the other rofecoxib 25 mg by mouth daily (Hefler 2006). In both studies the comparison arm received placebo tablets (Characteristics of included studies).

Excluded studies

We excluded four studies because they were reviews of chemoprevention (Mitchell 2007; Vlastos 2003), a clinical study of celecoxib together with chemoradiation for the treatment of cervical cancer (Herrera 2007), and a laboratory investigation of celecoxib in cervical cancer cell lines (Ferrandina 2003) (Characteristics of excluded studies).

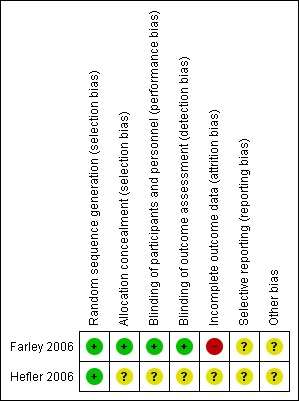

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias as being lower in the completed study (Farley 2006), as the randomisation code in the other study (Hefler 2006) was broken when rofecoxib could no longer be given to patients (Characteristics of included studies), (Figure 1; Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

Adequacy of randomisation was confirmed in both studies.

Allocation

Concealment of allocation was low risk in Farley 2006, but was unclear for Hefler 2006. (Characteristics of included studies)

Blinding

Performance bias was assessed as being at low risk of bias in Farley 2006, where both patients and the examining physicians were blinded to the treatment arm to which the patients were randomised, and unclear in Hefler 2006, since the statistician and pathologist were blinded at all times, but the randomisation code was broken (Characteristics of included studies).

Detection bias was assessed as low risk of bias with physicians, patients and pathologist blinded at all times in Farley 2006, and unclear in Hefler 2006, because of the broken code (Characteristics of included studies).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition bias was assessed as high risk in Farley 2006 because 'five patients (20%) discontinued the study early but were included in the final statistical analysis' and unclear in Hefler 2006 (Characteristics of included studies).

Selective reporting

There was insufficient information to assess in either study.

Other potential sources of bias

One study closed early (Farley 2006), but otherwise, there is insufficient data to identify whether other sources of bias exist.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Efficacy

Primary outcomes

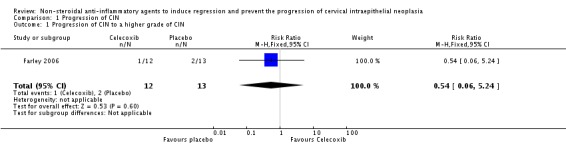

1. Progression of CIN to higher grades of CIN

Progression to a higher grade of CIN occurred in one out of 12 (8%) of those receiving celecoxib and two out of 13 (15%) receiving placebo (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.06 to 5.24; P value 0.6) (Analysis 1.1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Progression of CIN, Outcome 1 Progression of CIN to a higher grade of CIN.

The Heffler study did not comment on progression (Hefler 2006).

2. Progression of CIN to invasive carcinoma

Neither study reported on progression to invasive cancer (Farley 2006; Hefler 2006).

3. Regression of CIN

Partial or complete regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in 11 out of 20 (55%) in the treatment arms and five out of 21 (23.8%) in the placebo arms (RR 2.35, 95% CI 1.03 to 5.35; P value 0.04) (Analysis 2.1).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Regression of CIN 2 and 3, Outcome 1 Partial or complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3.

Complete regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in four out of 12 (33%) of those receiving celecoxib versus two out of 13 (15%) of those receiving placebo (RR 2.17, 95% CI 0.48 to 9.76; P value 0.31) (Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Regression of CIN 2 and 3, Outcome 2 Complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3.

Partial regression of CIN 2 or 3 occurred in five out of 12 (42%) of those receiving celecoxib versus two out of 13 (15%) of those receiving placebo (RR 2.71, 95% CI 0.64 to 11.43; P value 0.18) (Analysis 2.3).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Regression of CIN 2 and 3, Outcome 3 Partial regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3.

Secondary outcome

Adverse events related to treatment were not reported in either study (Farley 2006; Hefler 2006).

Discussion

The pursuit of non‐invasive methods to prevent the progression of CIN remains important in order to allow women to avoid the potentially serious morbidities of invasive treatments, including pain, bleeding, infection, cervical stenosis and premature birth in subsequent pregnancy, and to reduce the healthcare costs involved in the prevention of invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Although there are sound theoretical reasons why NSAIDs might have an effect on prevention of progression of CIN (as detailed in the Background), the findings of this review are not surprising in view of the small size and quality of the published data that were identified. The questions can only be resolved through the performance of appropriately designed clinical trials; such trials are difficult to perform in this setting.

It is important to note that any therapeutic benefit demonstrated as a result of further clinical trials will need to be weighed against the possible adverse effects of both NSAIDs and COX‐2 inhibitors that have been identified in large chemoprevention studies for colorectal adenomas.

In light of the causal association of high risk human papilloma virus (HPV) infection with the development and progression of CIN (Munoz 2006) and the high negative predictive value of clearance of high risk HPV infection following treatment, such testing might be an important factor to incorporate in future studies (Paraskevaidis 2004).

Summary of main results

We found no convincing evidence to support the use of NSAIDS in CIN 2/3 to induce complete or partial regression, or to prevent progression to higher grades.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The published data is currently far too small to determine significant efficacy and safety of NSAIDs in the treatment of CIN. Additionally, one of the medications used in this study (rofecoxib) was removed from the market in 2004. Despite it's removal, the outcomes from treatment with rofecoxib may be applicable as the other COX‐2 inhibitors have a similar mechanism of action.

Quality of the evidence

While the trials appear to have been well conducted they were of small size, and one was closed early due to withdrawal of the study agent.

The small sample sizes lend towards the possibility of random error as well as wide confidence intervals. Given that the natural history of CIN lends to some regression without intervention, these small studies are not of significant evidence to support treatment.

Given the paucity of data in the included studies, the small sample size, and the limitations from early study closure, we have downgraded the quality of the evidence to very low, according to GRADE criteria.

Potential biases in the review process

We undertook a comprehensive search to identify eligible studies. Three review authors extracted data independently. It is possible that there are other incomplete and unreported studies that have not been identified. We chose to retain data from the use of rofecoxib (removed from the market in 2004) in the review as findings may be similar to other COX‐2 inhibitors.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We did not identify any relevant studies or reviews.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy and safety of NSAIDs in the treatment of CIN. Only very low quality evidence is available from two small short‐term studies. Further, high quality RCTs are required. Although, during data collection any NSAID therapy was eligible, this review identified only two studies using COX‐2 inhibitors (celecoxib and rofecoxib (the latter of which was withdrawn from the market due to increased risk of cardiovascular events)) as the treatment agent. Whilst COX‐2 inhibitors may be theoretically preferred over other NSAIDs, given the high levels of the enzyme expressed with malignancy and the specificity of the agent, we found no evidence in other NSAIDs, and these other agents could be explored in future trials.

At the time of writing, a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) multi‐centre RCT of celecoxib has recently closed to patient entry and findings should be forthcoming. The protocol for this ongoing study includes treatment of women with CIN 2 or 3 with 400 mg celecoxib by mouth, once daily for 14 to 18 weeks versus placebo tablets with outcomes of complete or partial regression and toxicity (NCT 00081263). With an accrual goal of 130 patients, this study has the potential to build upon the existing literature in this area. An attempt to contact this group for preliminary data was made, but response was not received by the time of this writing.

As with any treatment, NSAIDs should be personalised to the patient. For those patients who are less likely to comply with close follow‐up and monitoring required for medical treatment, a surgical intervention may ultimately remain a better treatment approach.

Further understanding of the molecular mechanisms and pathways involved in cancer development and the interactions of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents with these pathways could lead to more effective chemo‐preventive agents without substantial toxicity, and should be pursued. Although there is currently insufficient evidence to promote use of NSAIDs for treatment of CIN, further studies may support a medical management approach, and save women (especially in their child‐bearing years) unnecessary procedures. Identifying HPV status prior to, and following treatment, could lead to further understanding of regression of CIN seen with NSAIDs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aaron Howell, Administrative Assistant, Division of Gynecologic Oncology; James Graham, Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville, USA for assistance with the first phase of this review; Jo Morrison for clinical and editorial advice; Jane Hayes for designing the search strategy and Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for their contribution to the editorial process. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Uterine Cervical Neoplasms] this term only # 2 MeSH descriptor: [Uterine Cervical Dysplasia] this term only #3 MeSH descriptor: [Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia] this term only #4 (cervi* near/5 (neoplas* or tumor* or tumour* or malignan* or carcinoma* or cancer* or dysplas* or intraepithel* or intra‐epithel*)) #5 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 #6 MeSH descriptor: [Anti‐Inflammatory Agents] explode all trees #7 (anti‐inflammatory or antiinflammatory) #8 NSAID* #9 (cyclo‐oxygenase or cyclooxygenase) #10 #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 #11 #5 and #10

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1 Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/ 2 Uterine Cervical Dysplasia/ 3 Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia/ 4 (cervi* adj5 (neoplas* or tumour* or tumour* or malignan* or carcinoma* or cancer* or dysplas* or intraepithel* or intra‐epithel*)).mp. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/ 7 (anti‐inflammatory or antiinflammatory).mp. 8 NSAID*.mp. 9 (cyclo‐oxygenase or cyclooxygenase).mp. 10 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11 5 and 10 12 randomised controlled trial.pt. 13 controlled clinical trial.pt. 14 randomized.ab. 15 placebo.ab. 16 drug therapy.fs. 17 randomly.ab. 18 trial.ab. 19 groups.ab. 20 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 21 11 and 20 22 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 23 21 not 22 key: mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier pt=publication type ab=abstract sh=subject heading ti=title

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

1 exp uterine cervix tumour/ 2 uterine cervix dysplasia/ 3 uterine cervix carcinoma in situ/ 4 (cervi* adj5 (neoplas* or tumour* or tumour* or malignan* or carcinoma* or cancer* or dysplas* or intraepithel* or intra‐epithel*)).mp. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp antiinflammatory agent/ 7 (anti‐inflammatory or antiinflammatory).mp. 8 NSAID*.mp. 9 (cyclo‐oxygenase or cyclooxygenase).mp. 10 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11 5 and 10 12 exp controlled clinical trial/ 13 crossover procedure/ 14 double‐blind procedure/ 15 randomised controlled trial/ 16 single‐blind procedure/ 17 random*.mp. 18 factorial*.mp. 19 (crossover* or cross over* or cross‐over*).mp. 20 placebo*.mp. 21 (double* adj blind*).mp. 22 (singl* adj blind*).mp. 23 assign*.mp. 24 allocat*.mp. 25 volunteer*.mp. 26 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27 11 and 26 28 (exp animal/ or nonhuman/ or exp animal experiment/) not human/ 29 27 not 28

key: mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword

Appendix 4. Risk of bias tool

We applied this tool to included studies to assess the risk of bias.

1. Random sequence generation

Low risk of bias e.g. participants assigned to treatments on basis of a computer‐generated random sequence or a table of random numbers.

High risk of bias e.g. participants assigned to treatments on basis of date of birth, clinic ID number or surname, or no attempt to randomise participants.

Unclear risk of bias e.g. not reported, information not available.

2. Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias e.g. where the allocation sequence could not be foretold.

High risk of bias e.g. allocation sequence could be foretold by patients, investigators or treatment providers.

Unclear risk of bias e.g. not reported.

3. Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk of bias if participants and personnel were adequately blinded.

High risk of bias if participants were not blinded to the intervention that the participant received.

Unclear risk of bias if this was not reported or unclear.

4. Blinding of outcomes assessors

Low risk of bias if outcome assessors were adequately blinded.

High risk of bias if outcome assessors were not blinded to the intervention that the participant received.

Unclear risk of bias if this was not reported or unclear.

5. Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias, if fewer than 20% of patients were lost to follow‐up and reasons for loss to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms.

High risk of bias, if more than 20% of patients were lost to follow‐up or reasons for loss to follow‐up differed between treatment arms.

Unclear risk of bias, if loss to follow‐up was not reported.

6. Selective reporting of outcomes

Low risk of bias e.g. reports all outcomes specified in the protocol.

High risk of bias e.g. it is suspected that outcomes have been selectively reported.

Unclear risk of bias e.g. if it is unclear whether outcomes have been selectively reported.

7. Other bias

Low risk of bias if you do not suspect any other source of bias and the trial appears to be methodologically sound.

High risk of bias if you suspect that the trial was prone to an additional bias.

Unclear risk of bias if you are uncertain whether an additional bias may have been present.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Progression of CIN

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Progression of CIN to a higher grade of CIN | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.06, 5.24] |

Comparison 2.

Regression of CIN 2 and 3

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Partial or complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3 | 2 | 41 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.35 [1.03, 5.35] |

| 2 Complete regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3 | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.17 [0.48, 9.76] |

| 3 Partial regression of CIN 2 or CIN 3 | 1 | 25 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.71 [0.64, 11.43] |

What's new

Last assessed as up‐to‐date: 30 November 2013.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 September 2016 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Differences between protocol and review

Shannon Grabosch MD joined the review group. The search strategy was reworked to make it more effective and an up‐to‐date search was performed. The Background was extensively edited and updated. The manuscript was edited to reflect the search and literature information and the updated Cochrane Review requirements and guidelines.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Farley 2006

| Methods | True randomisation with allocation by computer generated blocks. Parallel design without crossover. Patient, provider, pathologist blinded. All pathologic specimens were reviewed by a blinded central pathologist. Time for accrual 16 months (6/02 to 10/03). Analysis was by intent‐to‐treat | |

| Participants | 25 women. Eligibility included: greater than 18 years of age with biopsy proven CIN 2 or CIN 3. Exclusions included: pregnancy or breast feeding women; medical history of stomach bleeding; history of allergy after taking NSAIDs, severe kidney disease (such as creatinine greater than 1.2 mg/dl) or liver problems (such as AST greater than 80 U/L and ALT greater than 80 U/L); severe clinical immunosuppression; women taking NSAIDs for other medical conditions; or asthma associated with salicylates or NSAIDs. Also women with positive dysplasia on endocervical curettage or cervical cytology diagnosis of atypical glandular cells, carcinoma in situ, adenocarcinoma in situ, or invasive carcinoma. Age range 19 to 27 years. Race distribution not stated. Study performed at Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii, USA | |

| Interventions | Celecoxib 200 mg or placebo by mouth, twice daily with meals for six months, or until progression of dysplasia. All patients underwent initial colposcopy, thin‐prep liquid‐based cervical cytology, reflex HPV testing, and colpography of lesion with specimens reviewed by a blinded pathologist. Patients were seen at eight week intervals for six months. At each visit they underwent thin‐prep liquid‐based cervical cytology, colposcopy, photography of the cervix and biopsy. If colposcopy was normal, representative biopsy was taken from the area of previous dysplastic abnormality. Participants were removed from the study and underwent loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) for any increase in severity of CIN on cytology or histology. After six months, persistent CIN 3 required removal from study and treatment with LEEP. Participants missing an eight week follow‐up were contacted and asked to return for evaluation as soon as possible. Anyone not attending follow‐up was removed from the study and treated with LEEP | |

| Outcomes | Primary objectives were to determine response rate to treatment and toxicity of treatment. Toxicity was assessed at each eight week follow‐up visit by the treating pharmacist by direct questioning about the most common side effects of celecoxib. No toxicity was reported by participants.

Response was defined as any decrease in severity of CIN on histology. A complete response was defined as a complete visual resolution of the lesion on colposcopy and the absence of CIN on thin‐prep liquid‐based cytology and histology. Partial response defined as a decrease in severity of CIN on histology with no cytologic change in severity of CIN. Stable disease defined as no change in histologic degree of CIN from entry cervical biopsy. Progression was defined as any increase in severity of CIN on cytology or histology. Of the 25 participants 13 were randomised to the placebo and 12 to the treatment arm. Five participants (two in the treatment and three in the placebo arms) discontinued the study early because they desired definitive treatment. Overall response was N = 4 (31%) placebo versus N = 9 (75%) treatment. Mean time to response was 72 (+/‐ 38) days in the placebo arm and 73 (+/‐ 26) days in the treatment arm (P value 0.39). Complete response N = 2 (15%) placebo versus N = 4 (33%) treatment. Partial response was N = 2 (15%) placebo versus N = 5 (42%) treatment. Progression to higher degree of CIN was N = 2 (15%) placebo and N = 1 (8%) treatment arm with a mean time to progression of 65 days. No patients progressed to invasive carcinoma. The treatment arm was 2.5 x more likely to have regression of their cervical dysplasia |

|

| Notes | 100% of treatment arm women were positive for high‐risk types of HPV by Hybrid Capture II in comparison with 85% in the placebo arm. Eleven of 12 (92%) women in the treatment arm and 11 of 13 (85%) in the placebo arm had CIN 2 with 1 of 12 (8%) in the treatment arm and 2 of 13 (15%) in the placebo arm having CIN 3.

Two women in the treatment arm regressed from CIN 2 to CIN 1 in eight weeks, but wished then to be treated with LEEP, having final diagnoses of moderate dysplasia |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Randomization was performed using a computer generator Random Allocation Software, which randomised each subject to a single treatment, by using the method of randomly permuted blocks' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Allocation concealment was accomplished by the Department of Pharmacy. All physicians who participated in the implementation of the treatments, medication or placebo, were blinded to the randomisation process. Only the Pharmacy coordinator (E.G.) was aware of the allocation of the medications. Participants obtained their medications from E.G. in a separate encounter to their clinical follow‐up' |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'Both the patients and the examining physicians were blinded to the treatment option to which the patients were randomised' |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 'Both the patients and the examining physicians were blinded to the treatment option to which the patients were randomised |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 'Five patients (20%) discontinued the study early but were included in the final statistical analysis' |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

Hefler 2006

| Methods | True randomisation with allocation by computer generated blocks. Parallel design without crossover. Patient and physicians were blinded. No mention of pathologist. Analysis by intention‐to‐treat. No mention of who and how toxicity was assessed. Time for accrual five months (5/05 to 10/05). Study was closed after 87 days due to withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market. Randomisation code broken at this point |

|

| Participants | 16 women. Eligibility included: histological evidence of CIN 2 or CIN 3; a fully visible transformation zone and lesion margin; compliant patient; and safe contraception.

Exclusions included: presence of (micro‐)invasive cancer; endocervical lesion; upper margin of lesion not visible on colposcopy; and non‐compliant patient. Also: prior history of an adverse gastrointestinal event (ulcer, haemorrhage); age greater than 60 years; concurrent use of glucocorticoids; and allergic reaction to NSAIDs. Age: range 24 to 36 years, mean 27.1 years for treatment arm and 31.2 years for placebo arm |

|

| Interventions | Rofecoxib 25 mg or placebo, by mouth, daily for three months. After the screening visit a physical examination was performed, a questionnaire was answered and study medication was distributed. At initial visit all patients meeting inclusion criteria were evaluated for HPV status via Hybrid Capture (Digene Corp., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Follow‐up examinations performed at three and six months and included gynaecological examination with ecto‐ and endocervical cytology smears, colposcopy and biopsy, HPV test and pregnancy test. These modalities were used for the evaluation of regression, persistence, or progression of cervical dysplasia |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes assessed were regression and remission of CIN over a 3‐month treatment period, and secondary were safety and side‐effects. 16 women participated: eight in the treatment arm (four with CIN 2; four with CIN 3) and eight in the placebo arm (five with CIN 2; three with CIN 3). Regression occurred in two of eight (25%) in the treatment arm and one of eight (12.5%) in the placebo arm (P value 0.9), after a mean of 87 days of treatment | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Subjects were randomised using a random number sequence with permuted block size of 12' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Randomisation code broken when rofecoxib withdrawn from the market. Statistician and pathologist blinded at all times |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Randomisation code broken when rofecoxib withdrawn from the market. Statistician and pathologist blinded at all times |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to judge |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Early closure of study. Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase AST: aspartate aminotransferase CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia HPV: human papillomavirus LEEP: loop electrosurgical excision procedure NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agent

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ferrandina 2003 | Laboratory study of celecoxib in cervical cancer cell lines |

| Herrera 2007 | Phase I‐II study of celecoxib with chemoradiation in patients with cervical cancer |

| Mitchell 1995 | Review of chemoprevention trials and surrogate end point biomarkers in the cervix |

| Vlastos 2003 | Review of biomarkers and their use in cervical cancer chemoprevention |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | GOG 0207: A Randomized Double‐Blind Phase II Trial of Celecoxib, a COX‐2 Inhibitor, in the Treatment of Patients With Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 2/3 or 3 (CIN 2/3 or CIN 3) |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter study. Detail of randomisation unknown |

| Participants | Women age 18 years and over, with histologically proven CIN 2/3 or CIN 3 on cervical biopsy within two‐eight weeks from study entry. Pathology report must clearly state "CIN 2/3" or "3" OR "moderate‐severe dysplasia," "moderate‐severe dyskaryosis," "severe dysplasia," or "severe dyskaryosis." No CIN 2 alone or moderate dysplasia or dyskaryosis alone Colposcopically visible cervical lesion at study entry that is consistent with biopsy. No evidence of endocervical dysplasia or invasive cancer by cytology or biopsy. No history of cervical cancer. Gynecologic Oncology Group performance status 0, 1 or 2. Hematopoietic:platelet count greater than 125,000/mm3, haemoglobin greater than 11.0 g/dL, WBC greater than 3000/mm3. No significant bleeding disorder. Hepatic: bilirubin ≤ 1.5 times ULN (greater than 1.5 times ULN allowed if due to Gilbert's disease), AST and ALT less than 2.0 times ULN, no hepatic disorder. Renal: creatinine ≤ 1.5 times ULN, no known renal failure. Cardiovascular: no history of transient Ischaemic attack or stroke, no history of cardiovascular disease, no uncontrolled hypertension. Other: no undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, no known immunocompromised condition, no known allergic reaction (such as asthma, urticaria, or other reaction) to NSAIDs or aspirin, no known hypersensitivity to celecoxib,no known allergic reaction to sulphonamides,no history of peptic ulcer disease, must be good candidate for delayed treatment of CIN (i.e. deemed reliable to return for follow‐up and provide adequate contact information), not pregnant or nursing, negative pregnancy test, fertile patients must use effective contraception, no prior renal transplantation. Other: at least 15 days since prior non‐steriodal anti‐inflammatory agents or aspirin, no other concurrent NSAIDs or aspirin, no concurrent fluconazole or lithium. Projected accrual: maximum of 130 patients (39 per treatment arm) |

| Interventions | Arm I: Patients receive oral celecoxib once daily for 14 to 18 weeks. Arm II: Patients receive oral placebo once daily for 14 to 18 weeks. Patients undergo colposcopy at week eight and between weeks 14 and 18. Between weeks 14 and 18, patients with evidence of disease also undergo large loop excision of the transformation zone (cone biopsy) or cervical biopsy and patients with no evidence of disease undergo a cervical biopsy to confirm the absence of disease on colposcopy |

| Outcomes | Primary objectives: 1) to determine the efficacy of celecoxib to induce complete remission or partial regression to CIN 1 of CIN 2/3 or CIN 3 and 2) to determine the toxicity of celecoxib |

| Starting date | Opened October 2005. Closed to accrual April 2012 |

| Contact information | Janet Rader, MD Study Chair |

| User defined 1 | |

| Notes | Data retrieved from clinicaltrials.gov and http://cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=360805&version=healthprofessional |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase AST: aspartate aminotransferase CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia COX: cyclooxygenase NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agent ULN: upper limit of normal WBC: white blood cells

Contributions of authors

Link with Cochrane Review Group: Helm. Drafted the protocol: Helm. Searched for trials: Shariff, Grabosch, Helm. Abstraction of study data: Grabosch, Shariff, Helm. Writing of the review: Grabosch, Helm.

Sources of support

Internal sources

None, Other.

External sources

None, Other.

Declarations of interest

None.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

- Farley JH, Truong V, Goo E, Uyehara C, Belnap C, Larsen WI. A randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled phase II trial of the cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor Celecoxib in the treatment of cervical neoplasia. Gynecologic Oncology 2006;103(2):425‐30. [PUBMED: 16677697] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefler LA, Grimm C, Speiser P, Sliutz G, Reinthaller A. The cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor rofecoxib (Vioxx) in the treatment of cervical dysplasia grade II‐III. A phase II trial. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2005;125(2):251‐54. [PUBMED: 16188370] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Ferrandina G, Ranelletti FO, Legge F, Lauriola L, Salutari V, Gessi M, et al. Celecoxib modulates the expression of cyclooxygenase‐2, ki67, apoptosis‐related marker, and microvessel density in human cervical cancer: a pilot study. Clinical Cancer Research 2003;9(12):4324‐31. [PUBMED: 14555502] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera FG, Chan P, Doll C, Milosevic M, Oza A, Syed A, et al. A prospective phase I‐II trial of the cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor celecoxib in patients with carcinoma of the cervix with biomarker assessment of the tumor microenvironment. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology and Physics 2006;67(1):97‐103. [PUBMED: 17056201] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MF, Hittelman WK, Lotan R, Nishioka K, Tortolero‐Luna G, Richards‐Kortum R, et al. Chemoprevention trials and surrogate end point biomarkers in the cervix. Cancer 1995;76(10 Suppl):1956‐77. [PUBMED: 8634987] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlastos AT, Schottenfeld D, Follen M. Biomarkers and their use in cervical cancer chemoprevention. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology 2003;46(3):261‐73. [PUBMED: 12791426] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

- GOG 0207: A Randomized Double‐Blind Phase II Trial of Celecoxib, a COX‐2 Inhibitor, in the Treatment of Patients With Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 2/3 or 3 (CIN 2/3 or CIN 3). Ongoing study Opened October 2005. Closed to accrual April 2012.

Additional references

- Alvarez RD, Conner MG, Weiss H, Klug PM, Niwas S, Manne U, et al. The efficacy of 9‐cis retinoic acid (aliretinoin) as a chemopreventive agent for cervical dysplasia: results of a randomized double blind clinical trial. Cancer, Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2003;12(2):114‐9. [PUBMED: 12582020] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, Rácz I, Dite P, Hajer J, et al. PreSAP Trial Investigators. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;355:885‐95. [PUBMED: 16943401] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbyn M, Kyrgiou M, Simoens C, Raifu AO, Koliopoulos G, Martin‐Hirsch P, et al. Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta‐analysis. BMJ 2008;337:a1284. [PUBMED: 18801868] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. APC Study Investigators. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;355(9):873‐84. [PUBMED: 16943400] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker E, Koehler E, Smith J, Budwit D, Rahangdale L. Outcomes after management of young women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 with a 6‐month observation protocol. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 2014;18(1):46‐9. [PUBMED: 23959297] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Prescott SM. Many actions of cyclooxygenase‐2 in cellular dynamics and in cancer. Journal of Cell Physiology 2002;190(3):279‐86. [PUBMED: 11857443] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase: regulation of enzyme expression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1991;1083(2):121‐34. [PUBMED: 1903657] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun P, Yuce K, Usubutun A, Ayhan A. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III and squamous cell cervical carcinoma, and its correlation with clinicopathologic variables. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2007;17(1):164‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart CE, Coffey RJ, Radhik A. Up‐regulation of cyclooxygenase‐2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology 1994;107(4):1183‐8. [PUBMED: 7926468] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets CA, Viner JL, Pentland AP, Cantrell W, Lin HY, Bailey H, et al. Chemoprevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer with celecoxib: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2010;102(24):1835‐44. [PUBMED: 21115882] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J, Uyehara C, Hashiro G, Belnap C, Birrer M, Salminen E. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression predicts recurrence of cervical dysplasia following loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Gynecologic Oncology 2004;92(2):596‐602. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin H‐R, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer 2010;127(12):2893‐917. [PubMed: : 21351269] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Lauriola L, Zannoni GF, Distefano MG, Legge F, Salutari V, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) in tumour and stroma compartments in cervical cancer: clinical implications. Cancer 2002;87(10):1145‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandina G, Lauriola L, Distefano MF, Zannoni GF, Gessi M, Legge F, et al. Increased cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is associated with chemotherapy resistance and poor survival in cervical cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2002;20(4):973‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SM, Lo HH, Gordon GB, Seibert K, Kelloff G, Lubert RA, et al. Chemopreventive activity of celecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor, and indomethacin against ultraviolet‐light induced skin carcinogenesis. Molecular Carcinogenesis 1999;25(4):231‐40. [PUBMED: 10449029] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SM, Hawk ET, Lubet RA. Coxibs and other nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in animal models of cancer prevention. Cancer Prevention Research 2011;4(11):1728‐35. [PUBMED: 21778329] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follen M, Atkinson EN, Schottenfeld D, Malpica A, West L, Lippman S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of 4‐hydroxyphenylretinamide for high‐grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix. Clinical Cancer Research 2001;7(11):3356‐65. [PUBMED: 11705848] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney DK, Holden J, Davies M. Elevated cyclooxygenase‐2 expression correlates with diminished survival in carcinoma of the cervix treated with radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation, Oncology, Biology and Physics 2001;49(5):1213‐7. [PUBMED: 11286825] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney DK, Haslam D, Tsodikov A, Hammond E, Seaman J, Holden J, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) negatively affect overall survival in carcinoma of the cervix treated with radiotherapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 2003;56(4):922‐8. [PUBMED: 12829126] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser T, Fries S, FitzGerald GA. Biological basis for the cardiovascular consequences of COX‐2 inhibition: therapeutic challenges and opportunities. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2006;116(1):4‐15. [PUBMED: 16395396] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RE, Alshafie GA, Abou‐Isaa H, Seibert K. Chemoprevention of breast cancer in rats by celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor. Cancer Research 2000;60(8):2101‐3. [PUBMED: 10786667] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschman HR. Prostaglandin synthase 2. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1996;1299(1):125‐40. [PUBMED: 8555245] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hia T, Neilson K. Human cyclooxygenase‐2 cDNA. Proceedings of National Academy of Science USA 1992;89(16):7384‐8. [PUBMED: 1380156] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

- Huang D, Skollard D, Sharma S. Non‐small cell lung cancer cyclooxygenase‐2‐dependent regulation of cytokine balance in lymphocytes and macrophages: up regulation of interleukins 10 and down regulation of interleukins 12 production. Cancer Research 1998;58(6):1208‐16. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D, Scollard D, Byrne J, Levine E. Expression of cyclooxygenase‐1 and cyclooxygenase‐2 in human breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1998;90(6):455‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaisamrarn U, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, Naud P, Palmroth J, Rosario‐Raymundo MR, et al. HPV PATRICIA Study Group. Natural history of progression of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLOS One 2013;8(11):e79260. [PUBMED: 24260180] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamori T, Rao CV, Seibert K, Reddy BS. Chemopreventive activity of celecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor against colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Research 1998;58(3):409‐12. [PUBMED: 9458081] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloff GJ, Boone CW, Crowell JA, Steele VE, Lubet RA, Doody LA. New agents for cancer chemoprevention. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 1996;26S:1‐28. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YB, Kim GE, Cho NH, Pyo HR, Shim SJ, Chang SK, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase‐2 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with radiation and concurrent chemotherapy. Cancer 2002;95(3):531‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Seo SS, Song YS, Kang DH, Park IA, Kang SB, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase‐1 and ‐2 associated with expression of VEGF in primary cervical cancer and at metastatic lymph nodes. Gynecologic Oncology 2003;90(1):83‐90. [PUBMED: PMID: 12821346] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Lim SJ, Park K, Lee CM, Kim J. Cyclooxygenase‐2 and c‐erbB‐2 expression in uterine cervical neoplasm assessed using tissue microarrays. Gynecologic Oncology 2005;97(2):337‐41. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Rader JS, Zhang F, Liapis H, Koki AT, Masferrer JL, et al. Cyclooxygenase‐2 is overexpressed in human cervical cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2001;7:429‐34. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HY, Joo HJ, Choi JH, Yi JW, Yang MS, Cho DY, et al. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 protein in human gastric carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2000;6(2):519‐25. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, Lee R, Holland JF, Levine AC. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 suppresses angiogenesis and the growth of prostate cancer in vivo. Journal of Urology 2000;164(3):820‐5. [PUBMED: 10953162] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin‐Hirsch PPL, Paraskevaidis E, Bryant A, Dickinson HO, Keep SL. Surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001318.pub2; PUBMED: 20556751] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A, Newton JM, Brite K, Einspahr J, Ellis M, Davis J, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and vulvar cancer. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 2007;11(2):80‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed SI, Knapp DW, Bostwick DG, Foster RS, Khan KN, Masferrer JL, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) in human invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder. Cancer Research 1999;59(22):5647‐50. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkarah A, Ali‐Fehmi R. COX‐2: a protein with an active role in gynecological cancers. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;17(1):49‐53. [PUBMED: 15711411] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz N, Castellsague X, Gonzalez AB, Gissmann L. Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer. Vaccine 2006;24(Suppl 3):S1‐S10. [PUBMED: 16949995] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narisawa T, Sato M, Tani M, Kudo T, Takahashi T, Goto A. Inhibition of development of methylnitrosourea‐induced rat colon tumors by indomethacin treatment. Cancer Research 1981;41(5):1954‐7. [PUBMED: 7214363] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima E, Denda A, Ozono S, Takahama M, Akai H, Sasaki Y, et al. Chemopreventive effects of nimesulide, a selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor, on the development of rat urinary bladder carcinomas initiated by N‐butyl‐N‐(4‐hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine. Cancer Research 1998;58(14):3028‐31. [PUBMED: 9679967] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraskevaidis E, Arbyn M, Sotiriadis A, Diakomanolis E, Martin‐Hirsch P, Koliopoulos G, et al. The role of HPV DNA testing in the follow‐up period after treatment for CIN: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2004;30:205‐11. [PUBMED: 15023438] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockaj BA, Basu GD, Pathangey LB, Gray RJ, Hernandez JL, Gendler SJ, et al. Reduced T‐cell and dendritic cell function is related to cyclooxygenase‐2 overexpression and prostaglandin E2 secretion in patients with breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2004;11(3):328‐39. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaty BM, Potter JD. Risks and benefits of celecoxib to prevent recurrent adenomas. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;355(9):950‐2. [PUBMED: 16943408] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BS, Hirose Y, Lubet R, Steele V, Kelloff G, Paulson S, et al. Chemoprevention of colon cancer by specific cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor, celecoxib, administered during different stages of carcinogenesis. Cancer Research 2000;60(2):293‐7. [PUBMED: 10667579] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

- Ryu HS, Chang KH, Yang HW, Kim MS, Kwon HC, Oh KS. High cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in stage 1B cervical cancer with lymph node metastasis or parametrial invasion. Gynecologic Oncology 2000;76(3):320‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamma A, Yamamoto H, Doki Y, Okami J, Kondo M, Fujiwara Y, et al. Up‐regulation of cyclooxygenase‐2 in squamous carcinogenesis of the oesophagus. Clinical Cancer Research 2000;6(4):1229‐38. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat SF, Kim JH, Ayala GE, Kho K, Wheeler TM, Lerner SP. Cyclooxygenase‐2 is highly expressed in carcinoma in situ and T1 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Journal of Urology 2003;169(3):938‐42. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahama T. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is up‐regulated in transitional cell carcinoma and its preneoplastic lesions in the human urinary bladder. Clinical Cancer Research 2000;6(6):2424‐30. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski C, Cerella C, Dicato M, Ghibelli L, Diederich M. The role of cyclooxygenase‐2 in cell proliferation and cell death in human malignancies. International Journal of Cell Biology 2010 Mar 17 [Epub ahead of print]. [PUBMED: 20339581] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Soslow RA, Dannenberg AJ, Rush D, Woerner BM, Khan KN, Masferrer J, et al. COX‐2 is expressed in human pulmonary, colonic, and mammary tumors. Cancer 2000;89(12):2637‐45. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutter WP, Barros Lopes A, Fletcher A, Monaghan JM, Duncan ID, Paraskevaidis E, et al. Invasive cervical cancer after conservative therapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Lancet 1997;349(9057):978‐80. [PUBMED: 9100623] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolina M, Sharma S, Lin Y, Dohadwala M, Gardner B, Luo J, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 restores tumor reactivity by altering the balance of IL‐10 and IL‐12 synthesis. Journal of Immunology 2000;164(1):361‐70. [PUBMED: 10605031] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh Y‐J, Kundu JM. Signal transduction network leading to COX‐2 induction: a road map in search of cancer chemopreventives. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2005;28(1):1‐15. [PUBMED: 15742801] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KB, Putti TC. Cyclooxygenase 2 expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: immunohistochemical findings and potential implications. Journal of Clinical Pathology 2005;58(5):535‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujii M, Dubois RN. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells over expressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell 1995;83(3):493‐501. [PUBMED: 8521479] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proceedings of National Academy of Science USA 1997;94(7):3336‐40. [PUBMED: 9096394] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsujii S, Sawaoka H, Hori M, Dubois RN. Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 1998;93(5):705‐16. [PUBMED: 9630216] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]