Abstract

Background

People with serious mental illness not only experience an erosion of functioning in day‐to‐day life over a protracted period of time, but evidence also suggests that they have a greater risk of experiencing oral disease and greater oral treatment needs than the general population. Poor oral hygiene has been linked to coronary heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease and impacts on quality of life, affecting everyday functioning such as eating, comfort, appearance, social acceptance, and self esteem. Oral health, however, is often not seen as a priority in people suffering with serious mental illness.

Objectives

To review the effects of oral health education (advice and training) with or without monitoring for people with serious mental illness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register (5 November 2015), which is based on regular searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, BIOSIS, AMED, PubMed, PsycINFO, and clinical trials registries. There are no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records in the register.

Selection criteria

All randomised clinical trials focusing on oral health education (advice and training) with or without monitoring for people with serious mental illness.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For binary outcomes, we calculated risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI), on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For continuous data, we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups and its 95% CI. We employed a fixed‐effect model for analyses. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADE.

Main results

We included three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1358 participants. None of the studies provided useable data for the key outcomes of not having seen a dentist in the past year, not brushing teeth twice a day, chronic pain, clinically important adverse events, and service use. Data for leaving the study early and change in plaque index scores were provided.

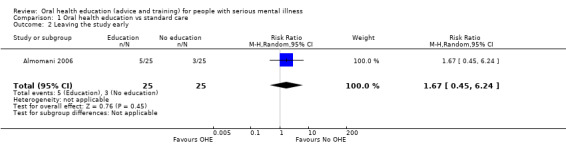

Oral health education compared with standard care

When 'oral health education' was compared with 'standard care', there was no clear difference between the groups for numbers leaving the study early (1 RCT, n = 50, RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.45 to 6.24, moderate‐quality evidence), while for dental state: no clinically important change in plaque index, an effect was found. Although this was statistically significant and favoured the intervention group, it is unclear if it was clinically important (1 RCT, n = 40, MD ‐ 0.50 95% CI ‐ 0.62 to ‐ 0.38, very low quality evidence).These limited data may have implications regarding improvement in oral hygiene.

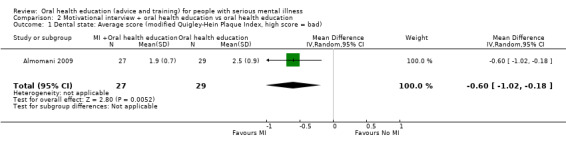

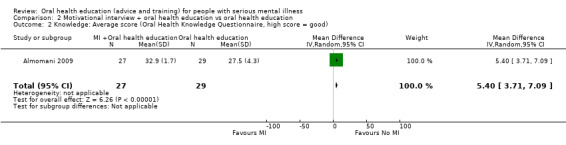

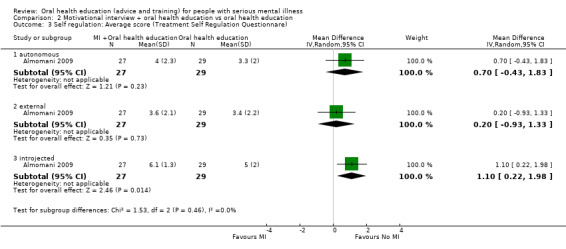

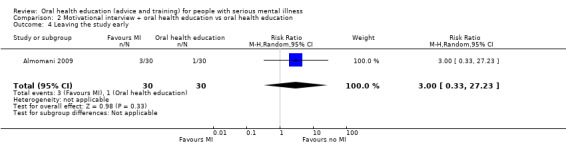

Motivational interview + oral health education compared with oral health education

Similarly, when 'motivational interview + oral health education' was compared with 'oral health education', there was no clear difference for the outcome of leaving the study early (1 RCT, n = 60 RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.33 to 27.23, moderate‐quality evidence), while for dental state: no clinically important change in plaque index, an effect favouring the intervention group was found (1 RCT, n = 56, MD ‐ 0.60 95% CI ‐ 1.02 to ‐ 0.18 very low‐quality evidence). These limited, clinically opaque data may or may not have implications regarding improvement in oral hygiene.

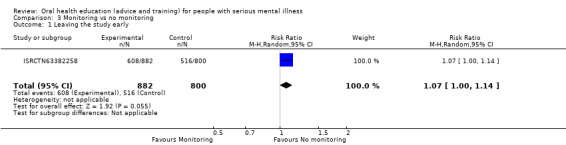

Monitoring compared with no monitoring

For this comparison, only data for leaving the study early were available. We found a difference in numbers leaving early, favouring the 'no monitoring' group (1 RCT, n = 1682, RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.14, moderate‐quality evidence). However, these data are problematic. The control denominator is implied and not clear, and follow‐up did not depend only on individual participants, but also on professional caregivers and organisations ‐ the latter changing frequently resulting in poor follow‐up, but not a good reflection of the acceptability of the monitoring to patients. For this comparison, no data were available for 'no clinically important change in plaque index'.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence from trials that oral health advice helps people with serious mental illness in terms of clinically meaningful outcomes. It makes sense to follow guidelines and recommendations such as those put forward by the British Society for Disability and Oral Health working group until better evidence is generated. Pioneering trialists have shown that evaluative studies relevant to oral health advice for people with serious mental illness are possible.

Keywords: Humans, Oral Health, Quality of Life, Mental Disorders, Mental Disorders/complications

Plain language summary

Oral heath advice (education and training) for people with serious mental illness

Is providing advice about oral health to people with serious mental illness effective?

Background

People with mental health problems have an increased likelihood of oral disease (affecting the teeth, mouth, and gums) and can require more dental treatment than the general population. Oral health is currently not a priority for service users and mental health professionals, even though tooth decay, discolouration, sensitivity, and gum disease can affect such aspects of everyday life as eating, comfort, appearance, feelings of being accepted by others, and self esteem. While unlikely in itself to be fatal, poor dental health can contribute to other physical health problems such as heart disease. Some medications used to treat serious mental illness can cause side effects that lead to oral disease.

Oral health advice from a healthcare professional may encourage people with mental health problems to brush their teeth more regularly, have regular check‐ups with their dentist, and seek dental care if suffering from painful tooth decay, increased sensitivity, or gum disease. Advice may include information or counsel that enables the individual to think about and be aware of their dental health. It should educate and inform, aim at preventing problems, and empower people to take better care of their mouth and teeth.

Study characteristics

We ran an electronic search in November 2015 for trials that randomised people with serious mental illness to receive either oral health advice, monitoring, or standard care. Three studies meeting the required standards were found and are included in this review.

Key results

The data available in the included trials suggests that participants receiving oral health education had statistically better plaque index scores than those not receiving oral heath education, but what this actually means clinically is unclear. The trials provided no information about such important issues as number of visits made to dentists or how many times teeth were brushed each day and if there were any potential adverse effects of oral health education. The review authors suggest that although there is currently no real evidence available from trials, it would make sense to follow the guidelines and recommendations put forward by the British Society for Disability and Oral Health working group regarding oral health care for people with mental health problems.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence in the small number of trials available was low to moderate. There is currently a lack of good‐quality evidence available from trials to aid in decision‐making about the overall effectiveness of oral health advice for people with serious mental illness. More good‐quality trials are required to gather better and more concrete evidence.

Ben Gray, Senior Peer Researcher, McPin Foundation. http://mcpin.org/

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral health education compared with standard care for people with serious mental illness.

| Oral health education compared to standard care for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: Oral health education Comparison: Standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard care | Oral health education | |||||

| Oral health: Not having seen a dentist in the past year | No study reported useable data | |||||

| Oral health: Not brushing teeth twice a day | ||||||

| Quality of life: Chronic pain | ||||||

| Adverse events: Clinically important specific adverse events | ||||||

| Service use: Emergency medical/dental treatment | ||||||

| Leaving the study early | 120 per 10001 | 200 per 1000 (54 to 749) | RR 1.67 (0.45 to 6.24) | 50 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Dental state: No clinically important change in plaque index Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index) | The mean dental state: no clinically important change in plaque index in the intervention groups was 0.5 lower (0.62 to 0.38 lower) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

112% control risk taken from included study. 2Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ supported by 'interested' industry, reporting problematic, unclear if standard error reported as standard deviation. 3Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not binary outcome, clinical meaning of average scores not clear.

Summary of findings 2. Motivational interview plus oral health education compared with oral health education for people with serious mental illness.

| Motivational interview plus oral health education compared to oral health education for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: Motivational interview plus oral health education Comparison: Oral health education | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Oral health education | Motivational interview + oral health education | |||||

| Oral health: Not having seen a dentist in the past year | No study reported useable data | |||||

| Oral health: Not brushing teeth twice a day | ||||||

| Quality of life: Chronic pain | ||||||

| Adverse events: Clinically important specific adverse events | ||||||

| Service use: Emergency medical/dental treatment | ||||||

| Leaving the study early | 33 per 10001 | 36 per 1000 (33 to 38) | RR 3.00 (0.33 to 27.23) | 60 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Dental state: No clinically important change in plaque index Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index) | The mean dental state: no clinically important change in plaque index in the intervention groups was 0.6 lower (1.02 to 0.18 lower) | 56 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Approximately 3% control risk taken from the included study. 2Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ important assumptions in the denominator data. 3Risk of bias: rated 'very serious' ‐ supported by 'interested' industry, reporting problematic, unclear if standard error reported as standard deviation. 4Indirectness: rated 'serious' ‐ not binary outcome, clinical meaning of average scores not clear.

Summary of findings 3. Monitoring compared to no monitoring for people with serious mental illness.

| Monitoring compared to no monitoring for people with serious mental illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: People with serious mental illness Settings: Intervention: Monitoring Comparison: No monitoring | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No monitoring | Monitoring | |||||

| Oral health: Not having seen a dentist in the past year | No study reported useable data | |||||

| Oral health: Not brushing teeth twice a day | ||||||

| Quality of life: Chronic pain | ||||||

| Adverse events: Clinically important specific adverse events | ||||||

| Service use: Emergency medical/dental treatment | ||||||

| Leaving the study early | 645 per 1000 | 690 per 1000 (645 to 735) | RR 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) | 1682 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Dental state: No clinically important change in plaque index | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No study reported useable data |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ important assumptions in the denominator data.

Background

Description of the condition

The definition of severe mental illness with the widest consensus is that of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Schinnar 1990), which characterises individuals based on diagnosis, duration, and disability (NIMH 1987). People with serious mental illness have conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or personality disorder, over a protracted period of time resulting in disruption of functioning in day‐to‐day life. A European survey put the total population‐based annual prevalence of serious mental illness at approximately 2 per 1000 (Ruggeri 2000). Oral health is an important part of overall physical health. While oral health needs of the mentally ill are similar to those of the general population, they have not been seen as a priority in this group. Evidence suggests that people with serious mental illness have a significantly increased chance of experiencing oral health problems than the general population (BSDH 2000; Stiefel 1990). A recent systematic review and meta‐analysis of advanced dental disease in people with severe mental illness found that this group not only had higher Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) scores, but also 3.4 times the odds of looing all their teeth as compared to the general population (Kisely 2011). While unlikely in itself to be fatal, poor oral hygiene has been linked to coronary heart disease (Montebugnoli 2004), diabetes, and respiratory disease and impacts on such aspects of everyday life as eating, comfort, appearance, social acceptance, and self esteem (Cormac 1999). The are many reasons why advanced dental disease is frequently seen in people with schizophrenia, mainly: schizophrenia impairs a person's ability to perform daily oral hygiene procedures due to lack of motivation; many drugs routinely prescribed such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilisers lead to changes in physiology leading to xerostomia (dry mouth), which in turn causes caries and periodontal disease; and some individuals may have limited access to dental treatment in the context of meagre financial resources (Friedlander 2002).

Description of the intervention

Oral health education is a process of combined learning experiences designed to predispose, enable, and reinforce voluntary behaviours conducive to health in individuals, populations, and communities (Frazier 1992). Health education is one of several prevention strategies that focus on lifestyle change appreciating the importance of social, cultural, behavioural, and economic factors as disease determinants. Both advice and training are major parts of health education. Advice is the active provision of the preventative information; it has an educative component and is delivered in a gentle, non‐patronising manner (Stott 1990). Oral health advice could therefore be defined as any verbal advice about maintenance of oral health from a healthcare professional, and can take many forms depending on environmental and socioeconomic factors.

In the context of this review, oral health training could be referred to as the act of teaching people with serious mental health illness skills to take care of their own oral health. The aim of monitoring, on the other hand, is to obtain information that could then be used to treat or prevent a physical condition (Tosh 2014). In some instances, monitoring is indicated for special groups with a distinct demographic risk factor, such as those suffering from serious mental illness. Monitoring could range from self monitoring to more specialised and guideline‐directed monitoring provided by the healthcare professional.

Oral health education is one of the most important tools of oral health promotion, which is defined as “a process of enabling people to take control over, and to improve their health” (WHO 2016). A major emphasis in health promotion is “to make healthy choices the easy choices” by focusing attention upstream.

Health education can be differentiated from monitoring in terms of target individuals, as shown in Table 4.

1. Differences between oral health education and monitoring.

| Target | People with serious mental illness via interventions directed at: | ||||

| People with the illness | Caregivers | Society | |||

Health education: Dental health education has 3 major domains (Daly 2013), namely:

|

Advice: “the active provision of the preventative information; it has an educative component and is delivered in a gentle non‐patronising manner" (Stott 1990) |

|

|

||

| Training: a process of learning a particular skill or skills required to perform a certain task | Aims at target individual’s knowledge and oral health‐related skills |

|

|||

| Monitoring: “Any means of observation, supervision, keeping under review, measuring or testing at intervals” (Tosh 2014) | Self monitoring | Monitoring by caregiver | Monitoring of relevant societal parameters | ||

How the intervention might work

Advice from a healthcare professional can have a positive impact on behaviour and plays a significant role in disease prevention (Kreuter 2000; Russell 1979). Advice may motivate people to seek further support and treatment (Sutherland 2003). Given the evidence of increased rates of potentially preventable health problems in people with serious mental illness (Cournos 2005; Dixon 1999; Robson 2007), and the suggestion from a systematic review that methodologically robust healthy living interventions result in “promising outcomes” in people with schizophrenia (Bradshaw 2005), we believe that appropriate oral health advice could prevent oral diseases and improve the quality and duration of life for sufferers of serious mental illness. Oral health advice from a healthcare professional may also motivate those with serious mental illness to improve their self care regimen, brush their teeth on a regular basis, trust their dentist, have regular dental check‐ups, and seek help in a dental emergency. Training these individuals to maintain their own oral health will help them carry out oral hygiene practices regularly with confidence, while information gathered by monitoring can be effectively employed to generate curative, palliative, and preventative medical treatments. This would also help to identify current and predict future diseases and subsequently improve the overall quality and duration of life for people suffering with serious mental illness.

Why it is important to do this review

Prevention being a core element in dentistry, a preventative orientation is employed in all aspects of dental practice, from diagnosis and treatment planning to monitoring procedures. Dentists and their teams have a huge responsibility to advise, train, and monitor people’s oral health. Individuals with serious mental illness are less likely to seek medical advice and are more likely to be exposed to medications with potentially negative health consequences (Weinmann 2009). These individuals should also stand to benefit from oral health advice as evidence suggests they are at greater risk of oral disease and have greater oral treatment needs than the general population (BSDH 2000). Oral health problems are not well recognised by mental health professionals, and people with serious mental illnesses can experience barriers to treatment (Cormac 1999), including low tolerance to their lack of compliance with oral hygiene, and a lack of understanding of mental health problems by dental professionals (BSDH 2000). It is important to update the previous review, as advice is a part of the broader concept of ‘oral health education’, which incorporates both advice and training of the target individuals. By contrast, monitoring involves reviewing and gathering information in order to prevent future disease in people (Tosh 2014). We know of no systematic review of oral health education with or without monitoring for those with serious mental illness.

Objectives

To review the effects of oral health education (advice and training) with or without monitoring for people with serious mental illness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all relevant randomised controlled trials (and economic evaluations conducted alongside included randomised controlled trials). We planned to exclude quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week. We planned to undertake a Sensitivity analysis for trials described in some way as to suggest or imply that the study was randomised and where the demographic details of each group's participants were similar.

Types of participants

For inclusion, we required that a majority of participants should be between 18 and 65 years old and suffering from severe mental illness, preferably as defined by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 1987), but in the absence of this, from diagnosed illnesses such as schizophrenia, schizophrenia‐like disorders, bipolar disorder, or serious affective disorder. We did not consider substance abuse to be a severe mental disorder in its own right, however we did consider studies to be eligible if they dealt with people with dual diagnoses, that is those with severe mental illness plus substance abuse. We did not intend to include studies focusing on dementia, personality disorder, or mental retardation, as they are not covered by our definition of severe mental illness.

Types of interventions

1. Oral health advice/training

We found a very useful definition of oral health advice from the previous review, that is preventative information, in Greenlund 2002, or counsel, in OED, that enables the recipient to make the final decision about their oral health. It should have at least a suggestion of: i. an educative component; ii. a preventative aim; and iii. an ethos of self empowerment. Advice could be directional but not paternalistic in its delivery. It is not a programmed or training approach, focusing on the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and competencies as a result of formal teaching sessions. Training could be defined as a process of learning particular skills to maintain one's own oral health.

2. Monitoring

Monitoring is defined as “any means of observation, supervision, keeping under review, measuring or testing at intervals” (Tosh 2014).

Compared with each other or:

2. Standard care

Care in which oral health advice and monitoring are not specifically emphasised above and beyond the care that would be expected for people suffering from severe mental illness.

Types of outcome measures

We planned to divide outcomes into four time periods: i. immediate (within one week); ii. short term (one week to six months); iii. medium term (six months to one year); and iv. long term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Oral health

1.1 Not owning a toothbrush 1.2 Not having seen a dentist in the past year 1.3 Not brushing teeth twice a day 1.4 Not flossing teeth twice a day 1.4 Incidence of either pain or infection related to dental caries1.5 Oral health knowledge score

2. Quality of life

2.1 Change in independence 2.2 Change in activities of daily living (ADL) skills 2.3 Chronic pain 2.4 Immobility 2.5 Change in earnings/employment 2.6 Change in social status 2.7 Healthy days 2.8 Clinically important change in general quality of life 2.9 Average endpoint general quality of life score 2.10 Average change in general quality of life score

3. Dental state

3.1 No clinically important change in plaque index 3.2 Any change in plaque index 3.3 Teeth lost due to decay 3.4 Change in dental caries 3.5 Change in periodontal disease 3.6 Change in oral infections

Secondary outcomes

4. Global state

4.1 Clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies) 4.2 Any change in global state 4.3 Average endpoint/change score global state scales 4.4 Relapse (as defined by the individual studies)

5. Mental state

5.1 Clinically important change in general mental state 5.2 Any change in general mental score 5.3 Average endpoint/change in general mental state score 5.4 Clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia) 5.5 Any change in specific symptom score 5.6 Average endpoint/change in specific symptom score

6. Adverse events

6.1 Number of participants with at least one adverse effect 6.2 Clinically important specific adverse events (cardiac events, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count) 6.3 Average endpoint/change specific adverse events score

7. Death

7.1 Natural 7.2 Suicide

8. Service use

8.1 Hospital admission 8.2 Emergency medical/dental treatment 8.3 Use of emergency services

9. Leaving the study early

9.1 Any reason 9.2 Due to adverse events 9.3 Due to inefficacy of treatment

10. General functioning

10.1 No clinically important change in general functioning 10.2 Average endpoint general functioning score 10.3 Average change in general functioning score

11. Social functioning

11.1 Social isolation as a result of preventable incapacity 11.2 Increased burden to caregivers

12. Economic

12.1 Increased costs of health care 12.2 Days off sick from work 12.3 Reduced contribution to society 12.4 Family claiming care allowance 12.5 Claiming unemployment benefit 12.6 Claiming financial assistance because of a physical disability

Summary of findings table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings and used GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from RevMan 5 (RevMan) to create a 'Summary of findings' table (Schünemann). This table provides outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient care and decision‐making. We aimed to include the following main outcomes in Summary of findings table 1.

Oral health: Not having seen a dentist in the past year

Oral health: Not brushing teeth twice a day

Quality of life: Chronic pain

Dental state: No clinically important change in plaque index

Adverse events: Clinically important specific adverse events (cardiac events, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count)

Service use: Emergency medical/dental treatment

Economic: Increased costs of health care

Leaving the study early

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register

On 5 November 2015, the Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Study‐Based Register of Trials using the following search strategy, which has been developed based on literature review and consulting with the authors of the review:

*Oral Health Intervention* in Intervention Field of STUDY

In such study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonym keywords and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics.

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, AMED, BIOSIS, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed, and clinical trials registries) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings (see Group’s Module). There is no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

For previous searches, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected the references of all identified included studies for other relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We planned to contact the first author of each included trial for information regarding unpublished studies. We also planned to contact the first author of each ongoing study to request information about the current progress of ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

We found three relevant trials that fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this review. The methods we planned to use for data collection and analysis are detailed below.

Selection of studies

Review authors MK and WK screened the results of the electronic search. WK inspected a random sample of these abstracts, comprising 10% of the total. We discussed any disagreements and documented decisions and, if necessary, acquired the full article for further inspection. We then requested the full articles of relevant reports for reassessment and carefully inspected them to make a final decision on inclusion (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). In turn, GT and AC inspected all full reports and independently decided whether they met inclusion criteria. We were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, or journal of publication. If we had found any studies for which it was impossible to make a decision, we would have added these studies to those awaiting assessment and contacted the authors of the papers for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Two review authors (MK and AC) independently extracted data from the included studies and compared results of the data extraction. We would have discussed any disagreements, documented our decisions, and contacted the authors of studies for clarification. Whenever possible, we would have extracted data presented only in graphs and figures and included the data if two review authors independently reached the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request, in order to obtain any missing information or for clarification. Where possible, we would have extracted data relevant to each component centre of multicentre studies separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

MK and WK extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Data from multicentre trials

If we had found multicentre trials to include, where possible the review authors would have independently verified calculated centre data against original trial reports.

2.3 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); b. the measuring instrument was not written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; and c. the measuring instrument was either i. a self report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided to primarily use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We planned to combine endpoint and change data in the analysis, as we aimed to use mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to relevant continuous data before inclusion.

We planned to enter all relevant data from studies of more than 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the following rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We would also have entered all relevant change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether data are skewed or not.

For endpoint data from studies of less than 200 participants, we planned to use the following methods:

(a) if a scale started from the finite number zero, we would have subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value is lower than 1, it strongly suggests a skew, and we would have excluded these data. If this ratio is higher than 1 but below 2, there is suggestion of skew. We would have entered these data to test whether their inclusion or exclusion changed the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio was larger than 2, we planned to include these data, because skew is less likely (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011);

(b) if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210) (Kay 1986), we planned to modify the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2 SD > (S ‐ S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week, or per month) to a common metric (for example mean days per month).

2.6. Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we planned to make efforts to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This could be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), in Overall 1962, or the PANSS (Kay 1986; Kay 1987), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005; Leucht 2005a). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we planned to use the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7. Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for oral health advice.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again, review authors MK and WK worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting.

If the raters had disagreed, we planned to make the final rating by consensus. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we planned to contact the authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We would have reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, and if disputes had arisen as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, we would have resolved this by discussion.

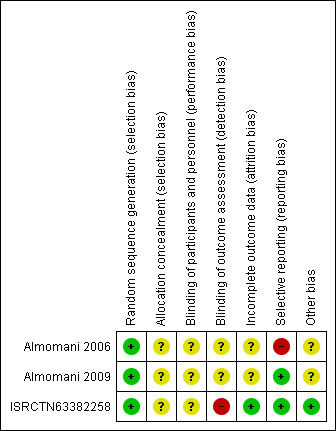

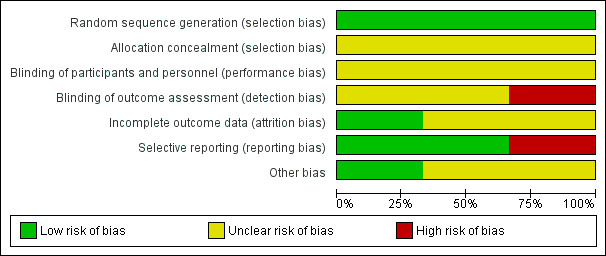

We noted the level of risk of bias in the Risk of bias in included studies, Figure 1, Figure 2, Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the random‐effects risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive than odds ratios (OR) and that ORs tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Boissel 1999; Deeks 2000). Within the 'Summary of findings' table we aimed to calculate the lowest control risk applied to all data. We assumed the same for the highest‐risk groups. We used the 'Summary of findings' table to calculate absolute risk reduction for primary outcomes.

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we estimated the mean difference (MD) between groups. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (standardised mean difference (SMD)). However, if in future versions of this review, if scales of very considerable similarity are used, we will presume there is a small difference in measurement, and we will calculate effect size and transform the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data pose problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow, and statistical significance overestimated (Divine 1992). This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we planned to present data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we planned to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) of clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC [Design effect = 1 + (m ‐ 1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC had not been reported, we would have assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed, taking into account ICC and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. This occurs if an effect (for example pharmacological, physiological, or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we planned to use only data from the first phase of cross‐over trials.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, we would have presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons if relevant. Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not have reproduced these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). For any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data been unaccounted, we would not have reproduced these data, or we would have used them within the analyses. However, if more than 50% of data in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we would have marked this data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome is between 0% and 50% and where these data had not been clearly described, we planned to present data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). We would have assumed those participants lost to follow‐up to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death. We would then have undertaken a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when 'completer' data only were compared to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumption.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

If attrition for a continuous outcome had been between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data were reported, we would have reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If measures of variance for continuous data were missing, but exact standard error and CIs were available for group means, and either the P value or t value were available for differences in mean, we would have calculated a standard deviation value according to the method described in Section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If standard deviations were not reported and could not be calculated from available data, we planned to ask the authors to supply the data. In the absence of data from authors, we would have used the mean standard deviation from other studies.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) would be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results. Therefore, where LOCF data had been used in a trial, if less than 50% of the data had been assumed, we would have reproduced these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We judged clinical heterogeneity by considering all included studies initially without seeing comparison data. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying situations or people that we had not predicted would arise. Should such situations or participant groups arise in future updates of this review, we will discuss these fully.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We judged methodological heterogeneity by considering all included studies initially without seeing comparison data. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise. Should such situations or participant groups arise in future updates of this review, we will discuss these fully.

3. Statistical

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 method alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i. magnitude and direction of effects and ii. strength of evidence for heterogeneity (for example P value from Chi2 test, or a CI for I2). We interpreted an I2 estimate greater than or equal to 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity according to Section 9.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and we explored the reasons for heterogeneity. When we found substantial levels of heterogeneity in the primary outcome, we explored the reasons for it.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We would have used funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size. In future cases, where funnel plots are possible, we plan to seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we used a random‐effects model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. According to our hypothesis of an existing variation across studies, to be explored further in the meta‐regression analysis, despite being cautious that the random‐effects method does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies, we favoured using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We anticipated no subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

2.1 Unanticipated heterogeneity

Should unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity have been obvious, we would simply have stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

2.2 Anticipated heterogeneity

We anticipated some heterogeneity for the primary outcomes and proposed to summate all data but also present them separately.

Sensitivity analysis

1. Implication of randomisation

We aimed to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we planned to include these studies, and if there was no substantive difference when we added the implied randomised studies to those with better description of randomisation, we would then have employed all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions must be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we planned to compare the findings of the primary outcomes where we used our assumption with completer data only. If there had been a substantial difference, we would have reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

See Table 5 for series of related reviews.

2. Series of related reviews.

| Title | Reference |

| Physical health care monitoring | Tosh 2014 |

| General physical‐health advice | Tosh 2014 |

| Advice regarding smoking cessation | Khanna 2012 |

| Advice regarding oral health care | This review |

| Advice regarding HIV/AIDS prevention | Wright 2014 |

| Advice regarding substance use | Under way |

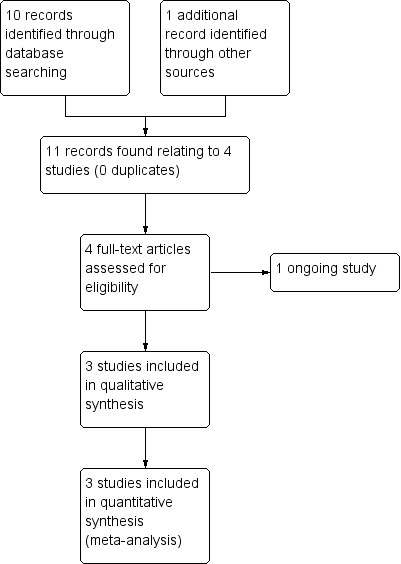

The initial search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of Trials in November 2015 was a combined search designed to identify studies relevant to physical‐health monitoring and physical‐health advice for people with serious mental illness. One review (Physical health care monitoring for people with serious mental illness) based on this search has already been published (Tosh 2010). Work has also begun on a series of sister reviews looking at physical‐health advice for people with serious mental illness. Two reviews have been published that examine general physical‐health advice (Tosh 2011; Tosh 2014), while two more reviews have been published looking at more targeted advice relating to specific problems or behaviours such as smoking and HIV (Khanna 2012; Wright 2014). The initial search identified 11 references (from 4 studies). After examining the reports, we found that only three were suitable for further examination, while one was an ongoing trial commencing in January 2016. The PRISMA table shows results of our search (see Figure 3).

3.

Study flow diagram for 2015 search results

Included studies

1. Methods

Due to the nature of the intervention, no studies were double blind. Two of the studies were parallel (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009), one was a cluster (ISRCTN63382258), and all were described as randomised (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009; ISRCTN63382258; NCT02512367).

All three studies reported outcomes immediately after intervention as well as after a follow‐up period of 4 weeks (Almomani 2006), 4 and 8 weeks (Almomani 2009), and after 12 months (ISRCTN63382258).

2. Length of trials

The duration of the included trials was 4 weeks in Almomani 2006, 8 weeks in Almomani 2009, and 12 months in ISRCTN63382258.

3. Participants

The three included studies involved a total of 1358 participants. Two studies included fewer than 100 participants (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009), and ISRCTN63382258 included 1248 participants. All studies included both males and females.

All studies included people with schizophrenia. None of the trials specified a valid diagnostic system. However, two studies determined the diagnosis through self reports and medical records (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). It is unknown whether not using diagnostic systems influenced the validity and reliability of the study findings.

No report referred to the current clinical state of participants (acute, early postacute, partial remission, remission), and similarly no report focused on people with particular problems, for example negative symptoms or treatment illnesses. None of the studies specified length of illness.

4. Setting

Two studies took place in the United States within the same community centre (Wyndott Center for Community and Behavioral Health, Kansas City, Kansas) (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). The third study took place in three shires (Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, and Lincolnshire) of the United Kingdom (ISRCTN63382258).

5. Interventions

5.1 Oral health education

In one study (Almomani 2006), a senior dental hygiene student provided the oral health education intervention along with dental hygiene instructions and a tooth brush reminding system, while in another, Almomani 2009, a doctoral psychology student provided a brief Motivational Interview (MI) session prior to oral health education. The content of the oral health education intervention was the same in both studies, that is participants were briefed about the effects of chronic mental illness on oral health, the advantages of good oral hygiene, and the disadvantages of bad oral hygiene. Neither study specified if the senior dental hygiene student or doctoral psychology student was trained to provide oral health education sessions, however it was specified that the doctoral psychology student was trained in MI.

Neither of the two studies provided information regarding the frequency of the oral health education session (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). Only one study specified the duration of the session, that is 15 minutes (Almomani 2006).

In two of the included studies the oral health education intervention was followed by the provision of two take‐home pamphlets (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). The first pamphlet explained the effects of psychiatric disabilities (in particular, medication) on oral health, while the second pamphlet outlined the correct way of brushing using a mechanical toothbrush.

5.2 Monitoring

Only one of the included studies mentioned monitoring as an intervention (ISRCTN63382258), looking at whether dental awareness training and dental checklist lead to a significant difference in the oral health behaviours of people with serious mental illness. Monitoring was provided by the usual clinical case worker who had the ongoing, day‐to‐day contact with the participant. Monitoring consisted of a single sheet of paper with a few broad, relevant questions.

5.3 Motivational Interviewing

In Almomani 2009, a doctoral psychology student provided a brief MI session (15 to 20 minutes) prior to oral health education. For those participants in the MI arm, the intervention was conducted prior to the education session and focused on exploring advantages and disadvantages, motivation and confidence, and personal values related to daily toothbrushing and oral health.

5.4 Standard care

Care in which oral health advice is not specifically emphasised above and beyond the care that would be expected for people suffering from severe mental illness.

One of the included studies compared oral health education intervention against standard care (no oral health education) (Almomani 2006). Another study compared MI and oral health education against oral health education alone (Almomani 2009). The third study compared monitoring against standard care (no monitoring) (ISRCTN63382258).

6. Outcomes

The outcomes for which we could obtain useable data are listed below, followed by a summary of data that we could not use in this review as well as missing outcomes.

6.1 Outcome scales

6.1.1 Dental state

In the context of this review, only two studies, Almomani 2006 and Almomani 2009, reported this outcome, measured by the modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index (Hiremath 2011). The modified technique of scoring plaque on the labial, buccal, and lingual surfaces is a comprehensive method of evaluating antiplaque procedures such as toothbrushing and flossing, as well as chemical antiplaque agents. A score of 0 to 5 is assigned to each facial and lingual non‐restored surface of all the teeth except third molars, with a high score of 5 indicating plaque covering two‐thirds or more of the crown of the tooth (0 = no plaque, 1 = separate flecks of plaque at the cervical margin of the tooth, 2 = a thin continuous band of plaque (up to 1 mm) at the cervical margin of the tooth, 3 = a band of plaque wider than 1 mm but covering less than one‐third of the crown of the tooth, 4 = plaque covering at least one‐third but less than two‐thirds of the crown of the tooth, 5 = plaque covering two‐thirds or more of the crown of the tooth).

6.2 Leaving the study early

All three studies reported this outcome (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009; ISRCTN63382258).

6.3 Missing outcomes

Overall, this review was subject to a considerable number of missing outcomes. No studies reported data on key outcomes of oral health: not having seen a dentist in the past year; oral health: not brushing teeth twice a day; quality of life: chronic pain; adverse events: clinically important adverse events; service use: emergency medical/dental treatment.

Excluded studies

No study was excluded.

1. Awaiting assessment

No studies are currently awaiting assessment.

2. Ongoing studies

One study was ongoing and was published in protocol format only (NCT02512367). This appears to be a comprehensive study with more than 200 participants (estimated 230) with 12 establishments cluster randomised over 12 months and outcomes detailed including primary outcome measure of proportion of participants with a Community Periodontal Index (CPI) ≥ to 3, dental health, and quality of life. Upon contacting the study author, we found that in the short term this study will enable a reduction in curative treatment needs. In the longer term, the program is expected to simultaneously reduce morbidity due to oral disease and related diseases. If shown to be effective, this intervention research will be a step towards changing medical practices in France.

We eagerly await data for this study.

Risk of bias in included studies

See also 'Risk of bias' table in Characteristics of included studies and Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

All studies were randomised controlled trials, using random sequence generation methods. Two of the included studies utilised a random numbers table for randomisation (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009), while the third study utilised block randomisation with block being a number of teams in each county (ISRCTN63382258); we rated all studies as at low risk of bias for sequence generation.

However, we rated all three studies as at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009; ISRCTN63382258), as no concealment strategy was described or explicit details on concealment approach reported.

Blinding

None of the included studies reported adequate blinding either of participants and personnel or of outcome assessment. However, one of the included studies reported no details of blinding (ISRCTN63382258).

One of the included studies reported using a randomised, controlled, 'examiner‐blind', parallel design (Almomani 2006), but it was unclear whether participants were blind to their allocation. Also, insufficient information was provided for blinding of outcome assessment.

In the second study (Almomani 2009), the examiner was not blind to group assignment and was aware of the intervention being delivered, but it was unclear whether participants were blind to their allocation.

The third study provided no details regarding blinding of participants, or personnel for outcome assessment; we rated this study as at high risk of performance and detection bias (ISRCTN63382258).

Incomplete outcome data

We rated two studies as at unclear risk of attrition bias because although they mentioned the number of participants who completed the study and the number who dropped out, the data from those who left early was not reported (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009).

Only one included study reported complete outcome (follow‐up) data and was rated as at low risk of attrition bias (ISRCTN63382258).

Selective reporting

We rated only one included study as at high risk of reporting bias (Almomani 2006), as only one outcome of several, plaque index score, was described clearly; the others, including leaving the study early, unable to use toothbrush, quality of life/satisfaction ‐ questionnaire, were not reported clearly.

The other two studies reported all the stated outcomes (Almomani 2009; ISRCTN63382258); we rated these studies as at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Two of the included studies appeared to have other potential sources of bias (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). We ranked them as at high risk of other bias, as support for the studies was approved by a grant from Proctor & Gamble Company, which produced Crest Spinbrush Pro toothbrushes, however we are unclear what effect this would have on the results. Also, in Almomani 2009, the additive design, which results in the MI group receiving more practitioner time, makes it unclear if MI (rather than greater attention) led to the observed treatment effects.

Furthermore, given the lack of a true control group or comparison with manual toothbrushing in Almomani 2006, it is unclear whether or not the same benefits would be derived from instructions on using a manual toothbrush.

The third study appears to be free from any other potential sources of bias (ISRCTN63382258).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Studies relevant to this review fell into three comparisons. We were able to extract numerical data from three randomised studies.

1. COMPARISON 1: ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION vs STANDARD CARE

One study (total N = 50) provided data for this comparison.

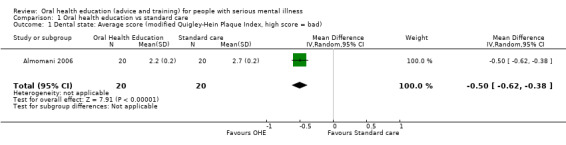

1.1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, high score = bad)

We found evidence of a clear difference between 'oral health education' and 'no specific oral health education' (mean difference (MD) ‐0.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.62 to ‐0.38, Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral health education vs standard care, Outcome 1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, high score = bad).

1.2 Leaving the study early

We found no evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments in this comparison (risk ratio (RR) 1.67, 95% CI 0.45 to 6.24, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral health education vs standard care, Outcome 2 Leaving the study early.

2. COMPARISON 2: MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEW + ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION vs ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION

One study (N = 60) provided data for this comparison.

2.1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, high score = bad)

We found evidence of a clear difference between 'motivational interview + oral health education' and 'oral health education' (1 RCT, n = 56, MD ‐0.6, 95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.18, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Motivational interview + oral health education vs oral health education, Outcome 1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, high score = bad).

2.2 Knowledge: Average score (Oral Health Knowledge Questionnaire, high score = good)

We found evidence of a clear difference between 'motivational interview + oral health education' and 'oral health education' (1 RCT, n = 56, MD 5.4, 95% CI 3.71 to 7.09, Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Motivational interview + oral health education vs oral health education, Outcome 2 Knowledge: Average score (Oral Health Knowledge Questionnaire, high score = good).

2.3 Self regulation: Average score (Treatment Self Regulation Questionnare, high score = good)

2.3.1 Autonomous

. For this subgroup, we did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments (1 RCT, n = 56, MD 0.7, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 1.83, Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Motivational interview + oral health education vs oral health education, Outcome 3 Self regulation: Average score (Treatment Self Regulation Questionnare).

2.3.2 External

For this subgroup, we did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments (1 RCT, n = 56, MD 0.2, 95% CI ‐0.93 to 1.33, Analysis 2.3).

2.3.3 Introjected

We did not find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments (1 RCT, n = 56, MD 1.1, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.98, Analysis 2.3).

2.4 Leaving the study early

No difference between groups was found ( 1 RCT, n = 60, RR 3.00 95% CI 0.33 to 27.23,.Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Motivational interview + oral health education vs oral health education, Outcome 4 Leaving the study early.

3. COMPARISON 3: MONITORING vs NO MONITORING

A single stude ( N = 1682) provided data for this for one outcome.

3.1 Leaving the study early

We did find evidence of a clear difference between the two treatments (RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.14, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Monitoring vs no monitoring, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

4. Missing outcomes

No studies reported data on key outcomes of oral health, quality of life, adverse events, and service use.

Discussion

Summary of main results

1. ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION compared to STANDARD CARE for people with serious mental illness

1.1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index)

The one relevant study (n = 50) suggests a clear difference between the two groups (Analysis 1.1), but although this was 'statistically' significant, it is unclear if it is 'clinically' important. We also categorised these data as being of very low quality. These limited data may have implications regarding improvement in oral hygiene, but what they are remains unclear to this dentist writing the review (author MK).

1.2 Leaving the study early

We found moderate‐quality data from one relevant trial (n = 50) suggesting no clear difference in the number of people leaving the study early from the oral health education group as compared to the standard‐care group (Analysis 1.2). Around 20% of participants left both groups by about 4 weeks. It is encouraging that 80% of people were able to tolerate the education programme.

1.3 Missing outcomes

The one relevant study did not report many key outcomes such as oral health behaviours, quality of life, adverse events, and service use. Even reasons for leaving the study were not specified. Oral health affects aspects of social life, including self esteem, social interaction, school, and job performance. Quality of life outcomes are of prime importance when considering effects of oral health education from a person's perspective. It would seem important not to forget these outcomes in future trials.

2. MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEW + ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION compared to ORAL HEALTH EDUCATION for people with serious mental illness

2.1 Dental state: Average score (modified Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index)

The one relevant study (n = 60) suggests a clear difference between the two groups (Analysis 2.1). We categorised these data as being of very low quality. As for the previous comparison, we had wanted some clear binary outcomes as regards 'dental state' but found none. These limited, clinically opaque data may ‐ or may not ‐ have implications regarding improvement in oral hygiene.

2.2 Leaving the study early

The one relevant trial (n = 60) found moderate‐quality data suggesting no clear difference in the number of people leaving the study early from the motivational interview plus oral health education group as compared to the oral health education‐only group (10% versus 3%, Analysis 2.4). The study was small, and it is difficult to know whether or not to be encouraged that a larger proportion than for Comparison 1 may have sustained enthusiasm throughout the oral health education programme, including those allocated to the control group.

2.3 Missing outcomes

The one relevant study did not report many key outcomes like oral health behaviours, quality of life, adverse events, and service use. The quality of life measure aids oral health professionals in determining the efficacy of treatment and in weighing its associated risks and benefits. Oral health aspects should also not be missed in future trials.

3. MONITORING compared to NO MONITORING for people with serious mental illness

3.1 Leaving the study early

The one relevant trial (n = 1682) found moderate‐quality data suggesting that more people in the monitoring group left the study early as compared with those allocated to no monitoring (Analysis 3.1). However, these data are problematic. The control denominator is implied and not clear, and follow‐up did not depend only on individual participants, but also on professional caregivers and organisations ‐ the latter changing frequently resulting in poor follow‐up, but not a good reflection of the acceptability of the monitoring to patients.

3.2 Missing outcomes

The one relevant study did report key outcomes like oral health, dental state, adverse events, and service use, but we could not include these data because of the enormous attrition (66%). The study did not report on quality of life. Clinicians, care providers, managers, policymakers, and people with the illness are less informed than they should be.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

1. Completeness

Evidence was certainly relevant, but overall data were too sparse to extensively address the objectives of this review. The search strategy identified 3 trials involving 1358 participants comparing oral health education with standard care, motivational interview and oral health education with oral health education alone, and monitoring against standard care.

A significant limitation of this review was the dearth of good‐quality studies, which in a broader perspective may have influenced the validity and applicability of the evidence. However, an important strength of this review was the presence of short‐, medium‐, or long‐term outcomes that may influence the directness of evidence given the chronic nature of schizophrenia. Also, even in the presence of short‐, medium‐, and long‐term outcomes, no data were provided for key outcomes of oral health: not having seen a dentist in the past year; oral health: not brushing teeth twice a day; quality of life: chronic pain; adverse events: clinically important adverse events; and service use: emergency medical/dental treatment. In Almomani 2006, only one follow‐up measurement was obtained, and long‐term positive effects of the study remain unknown.

2. Applicability

All three studies specified a diagnostic criteria; two of the included studies had a similar inclusion criteria, recruiting participants with severe mental illness with a minimum of one gradeable tooth in each sextant (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009), while the third study included any service users under the care of a care coordinator in an Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) team in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, and Lincolnshire aged 18 years or above. Later the inclusion was broadened to any EIP team willing to participate for which some sort of follow‐up could be provided. Settings varied between studies and included a mix of inpatients and outpatients.

Almomani 2006 and Almomani 2009 were conducted in a community centre in Kansas, United States, while the third study was based in three shires of the United Kingdom, where oral health education may be a more accepted mainstream practice (ISRCTN63382258). It was interesting to note that none of the studies were conducted in Middle Eastern, Asian, or African countries, therefore the implication of the findings may not be generaliseable to low‐income countries.

Two of the studies were relatively small, with 110 participants in total (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). The small size of these studies and lack of an extended follow‐up significantly weakens the quality of evidence presented, therefore any demonstrated difference between the oral health education intervention and control outcomes should be considered in this context. Only one study with more than 1000 participants may have strengthened the quality of evidence, but failed to determine that a reminder checklist had any effect on end‐of‐year follow‐up (ISRCTN63382258). Furthermore, this trial has no implications in terms of oral health as the only complete data the researchers managed to find was for follow‐up of 31%.

Quality of the evidence

See also Risk of bias in included studies and Table 1.

The quality of the current evidence was low to moderate based on GRADE and limits our confidence in the small positive changes shown in this review. All studies were randomised controlled trials, which require a random sequence allocation. Two of the included studies had utilised a random numbers table for randomisation (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009), while the third study utilised block randomisation, with block being a number of teams in each county; we rated these studies as at low risk of bias (ISRCTN63382258).

However, we rated all three studies as at unclear risk for allocation concealment (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009; ISRCTN63382258), as no concealment strategy was described or explicit details on concealment approach reported.

All three studies may have been at risk for performance bias, as blinding of the outcome assessor was unclear. One of the included studies reported using a randomised, controlled, examiner‐blind, parallel design, but it was unclear whether the participants were blind to their allocation (Almomani 2006). Also, insufficient information was provided for blinding of outcome assessment. In the second study (Almomani 2009), the examiner was not blind to group assignment and was aware of the intervention being delivered, but it was unclear whether participants were blind to their allocation. The third study provided no details regarding blinding of participants nor if personnel were blind for the outcome assessment; we rated this study as at high risk of performance and detection bias (ISRCTN63382258).

We rated two studies as at unclear risk of attrition bias due to incomplete outcome data because although they mentioned the number of participants who completed the study and the number who dropped out, data from those who left early was not reported (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). Only one included study reported complete outcome (follow‐up) data and was rated as at low risk of attrition bias (ISRCTN63382258).

We rated only one included study as at high risk of reporting bias, as only one outcome of several, plaque index score, was described clearly; the others, including leaving the study early, unable to use toothbrush, quality of life/satisfaction questionnaire, were not reported clearly (Almomani 2006).

Moreover, we noted a number of other sources of biases in two of the studies (Almomani 2006; Almomani 2009). We ranked them as at high risk of other bias as support for the study was approved by a grant from Proctor & Gamble Company, which produced Crest Spinbrush Pro toothbrushes, however we are unclear what effect this would have on the results. In Almomani 2006, given the lack of a true control group or comparison with manual toothbrushing, it is unclear whether or not the same benefits would be derived from instructions on using a manual toothbrush. Also, in Almomani 2009, the additive design, which results in the MI group receiving more practitioner time, makes it unclear if MI (rather than greater attention) led to the observed treatment effects.

Current medical practice in the United Kingdom is led by guidance from the British Society for Disability and Oral Health that is based predominantly on little more than anecdotal evidence produced from a working group (Griffiths 2000). The association between schizophrenia and poor oral health is well established (Cormac 1999), and, taken at face value, the current guidance seems to make sense. However, there are concerns around implementing guidance that has no evidence base, and vulnerable people with serious mental illness should surely expect that all aspects of their care has been subject to some degree of evaluation.

Potential biases in the review process

The search criteria on the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (November 2015) should have been robust enough to detect relevant studies. However, it is possible that we failed to identify small studies, although we think it unlikely that we would have missed large trials. Studies published in languages other than English, and those with equivocal results, are often difficult to find (Egger 1997). Our search was biased by use of English phrases. However, given that the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trials Register covers many languages but is indexed in English, we feel that we would not have missed many studies within the register. For example, the search uncovered 101 studies for which the title was only available in Chinese characters. These were checked for relevance by a Chinese speaking colleague (Jun Xia), and none were identified as possibly relevant to this review.

Furthermore, we were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, or journal of publication, which may have introduced bias into the review process.

The primary author of this review has a background in dental public health and took a public health approach torward the review rather than opting for a general oral health approach. For the same reason, the interventions in the previous review have been amended to clearly reflect a public health perspective. We are not aware if this form of bias has affected the findings or external and internal validity of the evidence.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews