Abstract

Background

Associations between nursing home residents’ oral health status and quality of life, respiratory tract infections, and nutritional status have been reported. Educational interventions for nurses or residents, or both, focusing on knowledge and skills related to oral health management may have the potential to improve residents’ oral health.

Objectives

To assess the effects of oral health educational interventions for nursing home staff or residents, or both, to maintain or improve the oral health of nursing home residents.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Oral Health Trials Register (to 18 January 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, 2015, Issue 12), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 18 January 2016), Embase Ovid (1980 to 18 January 2016), CINAHL EBSCO (1937 to 18 January 2016), and Web of Science Conference Proceedings (1990 to 18 January 2016). We searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for ongoing trials to 18 January 2016. In addition, we searched reference lists of identified articles and contacted experts in the field. We placed no restrictions on language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs comparing oral health educational programmes for nursing staff or residents, or both with usual care or any other oral healthcare intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened articles retrieved from the searches for relevance, extracted data from included studies, assessed risk of bias for each included study, and evaluated the overall quality of the evidence. We retrieved data about the development and evaluation processes of complex interventions on the basis of the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). We contacted authors of relevant studies for additional information.

Main results

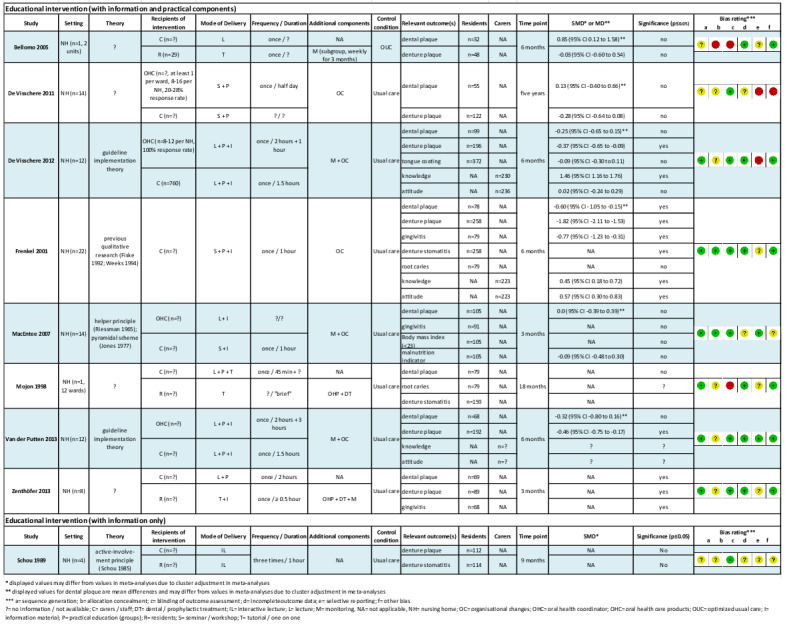

We included nine RCTs involving 3253 nursing home residents in this review; seven of these trials used cluster randomisation. The mean resident age ranged from 78 to 86 years across studies, and most participants were women (more than 66% in all studies). The proportion of residents with dental protheses ranged from 62% to 87%, and the proportion of edentulous residents ranged from 32% to 90% across studies.

Eight studies compared educational interventions with information and practical components versus (optimised) usual care, while the ninth study compared educational interventions with information only versus usual care. All interventions included educational sessions on oral health for nursing staff (five trials) or for both staff and residents (four trials), and used more than one active component. Follow‐up of included studies ranged from three months to five years.

No study showed overall low risk of bias. Four studies had a high risk of bias, and the other five studies were at unclear risk of bias.

None of the trials assessed our predefined primary outcomes 'oral health' and 'oral health‐related quality of life'. All trials assessed our third primary outcome, 'dental or denture plaque'. Meta‐analyses showed no evidence of a difference between interventions and usual care for dental plaque (mean difference ‐0.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.26 to 0.17; six trials; 437 participants; low quality evidence) or denture plaque (standardised mean difference ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.25 to 0.05; five trials; 816 participants; low quality evidence). None of the studies assessed adverse events of the intervention.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence to draw robust conclusions about the effects of oral health educational interventions for nursing home staff and residents. We did not find evidence of meaningful effects of educational interventions on any measure of residents' oral health; however, the quality of the available evidence is low. More adequately powered and high‐quality studies using relevant outcome measures are needed.

Plain language summary

Education for nursing home staff and/or residents to improve residents' oral health

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effectiveness of oral health education for nursing staff or nursing home residents compared to usual care for improving residents' oral health.

Background

Nursing home residents are often unable to carry out proper oral care, which is an important factor in maintaining the health of the mouth, teeth, and gums. Nursing home staff may not be prepared to provide adequate care. Therefore, oral health care education for residents and/or nursing staff may be one strategy to improve this situation.

Study characteristics

We searched for relevant studies that had been conducted up until January 2016 and identified nine trials involving a total of 3253 nursing home residents. The average age of residents across the studies ranged from 78 to 86 years. In all of the studies most of the people taking part had dentures (between 62% and 87%).

The trials evaluated a variety of approaches including educational programmes, skills training, and written information material. Topics included dental issues that were particularly relevant for older people such as care of dentures and covered dental and oral diseases, prevention of oral diseases, dental hygiene tools, and oral health care guidelines. The length of the trials ranged from three months to five years.

Key results

We could not identify a clear benefit of training of nurses and/or residents on residents' dental health as assessed by dental and denture plaque. No study assessed oral health, oral health‐related quality of life or adverse events. As education programmes were not fully described, results do not allow for clear conclusions about the effectiveness or potential harm of specific oral health education interventions in nursing homes.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, there was a low quality of information from the studies regarding all of the results. We conclude that there is a need for clinical trials to investigate the advantages and harms of oral health educational programmes in nursing homes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral health education for nursing home staff and residents (with information and practical components) compared to usual care.

| Oral health education for nursing home staff and residents (with information and practical components) compared to usual care | ||||||

|

Patient or population: nursing home residents Settings: nursing homes Intervention: oral health education (with information and practical components) Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Oral health education (with information and practical components) | |||||

| Oral health‐related quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not reported |

| Oral health | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Outcome not reported |

|

Dental plaque Plaque Index, Oral Hygiene Index, Geriatric Simplified Debris Index (all scales scoring 0 to 3) Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months |

Mean dental plaque scores in control groups ranged from 0.29 to 2.18 (0 to 3 scale) | Mean difference 0.04 lower (95% CI 0.26 lower to 0.17 higher) |

See comment | 437 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Information from 2 further studies was not available for meta‐analysis. A lower score indicates less plaque. |

|

Denture plaque Denture Plaque Index (scoring 0 to 3) and method of Augsburger (scoring 0 to 4) Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months |

See comment | Standardised mean difference

0.60 lower (95% CI 1.25 lower to 0.05 higher) |

See comment | 816 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Different outcome scales used Information from another study was not available for meta‐analysis. |

|

Gingivitis Gingival Bleeding Index and method of Suomi Follow‐up: 3 to 6 months |

245 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | No meta‐analysis (data not comparable). 3 studies at unclear risk of bias showed inconsistent results. |

|||

|

Denture‐induced stomatitis Method of Budtz‐Jørgensen Follow‐up: 6 to 18 months |

417 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | No meta‐analysis (data not comparable). 2 studies at unclear, in Frenkel 2001, or high risk of bias, in Mojon 1998, showed no apparent differences at short‐term, in Frenkel 2001, or long‐term follow‐up (Mojon 1998). |

|||

|

Caries/root caries Follow‐up: 6 to 18 months |

178 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | 2 studies at unclear, in Frenkel 2001, or high risk of bias, in Mojon 1998, showed no apparent differences at short‐term, in Frenkel 2001, or long‐term follow‐up (Mojon 1998). | |||

| CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias. 2Downgraded one level due to inconsistency (heterogeneity): I2= 66% and 92%. 3Downgraded one level due to inconsistency (clinical heterogeneity).

Background

Description of the condition

The demographic shift in high‐income countries as people live longer has important implications for healthcare services. There are and will be more elderly people with important morbidity and care dependency (Branca 2009), and an increasing number of nursing home residents. Whereas, until recently, most nursing home residents were provided with dentures, now a larger number of residents retain a considerable number of natural teeth (Hopcraft 2012; Porter 2015; Samson 2008). Declining rates of edentulism (having no teeth) have important implications for oral health and oral health management of these residents, as a greater proportion will have teeth at risk of dental caries and periodontal disease. Additionally, high‐quality and complex dental prostheses (i.e. implants, bridges, and removable dental prostheses) must be maintained. Nursing home residents are often unable to carry out adequate oral care, such as optimal removal of dental plaque. Continuous preventive and curative oral health care provided by trained staff therefore seems increasingly important. In nursing homes, nursing staff and other caregivers play a crucial role in the provision of daily oral health care (Porter 2015), as well as in initiating and organising routine prophylaxis and treatment by dental professionals (Nitschke 2010).

In the past, it was reported that nursing staff frequently do not acknowledge the importance of oral health and lack knowledge about how to achieve it (Glassman 1994). Some more recent studies have suggested knowledge about oral hygiene is still inadequate among nursing staff (Jablonski 2009; Wardh 2012), and that there is a large discrepancy between the proposed need for assistance with daily oral hygiene among nursing home residents and the actual assistance provided by nursing staff (Forsell 2009). In addition to dependence, some people with dementia exhibit unco‐operative or disruptive behaviour during helping interactions. These behaviours range from mild (e.g. turning the head away) to extreme resistance (e.g. hitting the nursing staff) (Jablonski 2009). This so‐called care‐resistant behaviour is a common phenomenon encountered by nursing staff during the provision of oral care (Frenkel 1999; Jablonski 2011).

Measures of poor oral health (e.g. gingivitis, caries, and chewing difficulties), along with discomfort and pain, have been reported for nursing home residents in different countries (De Visschere 2006; Gluhak 2010; Hopcraft 2012; Simunković 2005; Wyatt 2002). Dental plaque generally leads to an increased risk for dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis, as well as other infections in the oral cavity.

In addition, poor oral hygiene and poor dental status among elderly people are associated with reduced quality of life (Porter 2015; Walker 2007). Elderly people in day care have shown considerably higher levels of oral health problems compared to community‐dwelling elderly (Walker 2007), due to difficulties in maintaining a sufficient level of oral hygiene and in accessing professional dental care (Forsell 2009). Two‐thirds of elderly people living in residential facilities use dental services only in the case of dental problems and on demand (De Baat 1993; Isaksson 2007). In a British study, 70% of residents had not seen a dentist for more than five years (Frenkel 2000).

The accumulation of micro‐organisms on teeth and denture surfaces, caused by lack of oral hygiene, may influence residents' general health by causing pneumonia, arteriosclerosis, and infection‐related disorders (Azarpazhooh 2006; Desvarieux 2003; Scannapieco 2003; Shay 2002). Evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggests positive preventive effects of oral care on respiratory tract infection and pneumonia in nursing home residents (El‐Rabbany 2015; Sjögren 2008).

Furthermore, poor oral health has been associated with involuntary weight loss (Mojon 1999; Sheiham 2001). Institutionalised elderly people who suffer from oral discomfort, problems with chewing or swallowing, compromised dentition, or poorly fitted dentures have a higher incidence of nutritional deficiency (Saarela 2014; Saunders 2007).

Consequently, interventions to improve oral health seem warranted, as they possibly yield a number of positive effects including improved nutritional status and health‐related quality of life (Naito 2010).

Description of the intervention

In the context of this review, we have defined oral health‐related educational interventions as programmes that facilitate knowledge and skills acquisition in nursing home staff and/or residents to maintain or improve oral health, using a variety of formats (e.g. lectures, demonstrations, practical education). Programmes may target nursing home residents, staff, or both and may be provided to individuals or groups.

Interventions are usually complex, consisting of several different components. Three commonly included components included are:

theoretical education for staff or residents, or both aiming at improving knowledge of oral health and oral health care;

staff training (practical education) on examination and cleansing of the mouth or dentures, or both of residents; and

oral hygiene skills training for residents.

How the intervention might work

In general, the goal of educational interventions is to improve oral and dental health of residents by increasing knowledge and skill levels of nursing home staff or nursing home residents, or both.

Interventions targeting nursing home residents, especially oral hygiene skills training, may foster the ability to self perform dental care and thus decrease the need for assistance. There may also be direct effects of education on residents' attitudes as well as on quality of life.

Interventions targeting nursing home staff will strengthen staff expertise in oral care for residents. Furthermore, staff attitude and self efficacy will be influenced, leading (together with improved knowledge and skills) to improved oral health‐related behaviour and, as a consequence, improved oral health outcomes for residents.

Why it is important to do this review

The Cochrane Oral Health Group undertook an extensive prioritisation exercise in 2014 to identify a core portfolio of titles that were the most clinically important ones to maintain on the Cochrane Library (Worthington 2015). This review was identified as a priority title by the dental public health expert panel (Cochrane OHG priority review portfolio).

At the time of protocol preparation, there were no systematic reviews available summarising the effects of providing oral healthcare education to nursing home staff and/or residents. In 2014, a systematic review on oral healthcare education was published, which included two RCTs, one non‐randomised study, and three cross‐sectional studies (De Lugt‐Lustig 2014). The authors concluded that oral healthcare education for nursing staff may have a positive effect on attitudes and oral healthcare knowledge of nurses in nursing homes and on oral hygiene of residents. Meta‐analyses by Wang 2015 including one RCT and four before‐and‐after studies also found limited evidence that education for caregivers is effective in improving oral health. However, both reviews only focused on educational interventions for nursing staff or caregivers. De Lugt‐Lustig 2014 disregarded any educational interventions considering nursing home residents as recipients, whereas Wang 2015 excluded education for residents only. In addition, a further systematic review, Weening‐Verbree 2013, which included a broad range of study designs, concluded that knowledge, self efficacy, and facilitation of behaviour are determinants that are used in successful implementation strategies. Taking into account the heterogeneity of studies, the authors were not able to recommend a single strategy or combination of strategies for improving oral health in institutionalised elderly. Furthermore, they highlighted the importance of considering contextual factors (e.g. setting) when choosing implementation strategies. A high‐quality systematic review considering the growing number of RCTs published in recent years and describing the components of interventions was therefore warranted. This systematic review may impact the implementation of different approaches and trigger the development of new interventions on the basis of current best evidence.

Objectives

To assess the effects of oral health educational interventions for nursing home staff or residents, or both, to maintain or improve residents’ oral health.

To describe the components of the complex interventions used in the included studies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included individually randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or cluster‐RCTs with a follow‐up period of at least two weeks including groups of nursing home staff or residents, or both allocated either to:

a programme aiming to maintain or improve oral health of nursing home residents by one or more oral health educational and/or oral hygiene promotion interventions (the intervention group); or

(optimised) regular dental care or any other oral healthcare intervention (the control group). Optimised care means that the control group receives an additional component in addition to usual standardised care, e.g. provision of dental care auxiliaries or informative presentations.

We considered additional publications on development and piloting of complex interventions as well as process evaluations, without focusing on specific study designs, in order to capture single components of the complex interventions and contextual factors.

Types of participants

We considered male and female residents living in facilities providing supervision or nursing care for the elderly (e.g. nursing homes or long‐term care facilities) for inclusion. The majority of residents in a study had to be over the age of 64 years, or the mean age had to be at least 65 years. We also included nursing staff working in these facilities or a combination of residents and nursing staff. We included all participants involved in the primary studies (i.e. irrespective of residents' oral health status or qualifications of the nursing staff).

Types of interventions

We included any trial of an intervention or group of interventions where participants or clusters were allocated to receive an oral health education programme versus (optimised) usual oral health care, or any other oral healthcare intervention.

Oral health education programmes include either direct‐to‐staff programmes, direct‐to‐resident programmes (e.g. oral hygiene promotion or skills training), or a combination of both. We expected approaches to vary, for example in terms of frequency, length, and content, with the educational content likely to include some or all of the following: oral health, oral diseases and impact on general health, diet, oral hygiene measures, best oral care practices for elderly people with natural dentition and dentures, oral hygiene promotion, and skills training.

We expected some interventions to be designed as complex interventions comprising more than one of the components outlined above. Following the 'framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions', it may not be possible to extract the effective or ineffective components of the interventions (Campbell 2000; Craig 2008), but components of included programmes were collected and described in detail as suggested by Lenz 2007.

We considered interventions without educational or oral hygiene promotion components only as controls. In addition, we considered sole organisational interventions aiming to change organisational policies, for example through introduction of practice guidelines, oral health co‐ordinators, regular visits by a dentist or dental hygienist for professional oral care and examination, or regular visits of residents in dental surgeries, only as controls. The same applied to exclusive oral hygiene interventions (e.g. the provision of chemical topical interventions and mechanical auxiliaries).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Oral health‐related quality of life: measured by instruments such as Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) or OHIP‐14 (Slade 1994; Slade 1997), Geriatric/General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) (Atchison 1990), Dental Impact Profile (DIP) (Strauss 1993).

Oral health: oral health was defined as a functional, structural, aesthetic, physiologic, and psychosocial state of well‐being assessed by an instrument such as Brief Oral Health Status Examination (BOHSE) or Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) that covers different oral hygiene categories (Chalmers 2005; Kayser‐Jones 1995).

-

Dental health: dental health comprises only one aspect of oral health, such as:

dental or denture plaque, or both: measured by plaque scores and denture cleanliness scores (scales) such as Plaque Index (Silness 1964), Mucosal‐Plaque Index (MPS) (Henriksen 1999), or Denture Plaque Index (Wefers 1999);

gingivitis or denture‐induced stomatitis: measured by instruments such as Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) (Ainamo 1975), Gingival Index (Löe 1967), or Community Periodontal Index (Benigeri 2000); or

caries, incidence of new caries.

Secondary outcomes

Nutritional status (e.g. body weight, Body Mass Index (BMI)).

Incidence of respiratory diseases and pneumonia.

Adverse effects of the interventions.

Intermediate outcomes

Oral health‐related knowledge of staff or residents, or both: measured by any instruments used in the included studies (e.g. questionnaire or interview).

Oral health‐related attitude and behaviour of staff or residents, or both: measured by any instruments used in the included studies (e.g. questionnaire or interview).

Search methods for identification of studies

We developed detailed search strategies for each database to identify studies for inclusion in the review. These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE Ovid but revised appropriately for each database. The search strategy used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free‐text terms and was linked with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying RCTs in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐maximising version (2008 revision) as referenced in Section 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011). Details of the MEDLINE search are provided in Appendix 3. The searches of EMBASE and CINAHL were linked to Cochrane Oral Health's filters for identifying RCTs.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Oral Health Trials Register (to 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 12) in the Cochrane Library (searched 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 4);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 5);

Web of Science Conference Proceedings (1990 to 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 6).

We placed no restrictions on language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases.

Searching other resources

We searched the following databases for ongoing trials:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 7);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 18 January 2016) (see Appendix 8).

We examined the reference lists of published reviews and contacted experts in the field to identify unpublished or ongoing studies. We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions, considering the adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MA and RK) independently screened the titles and abstracts of citations identified by the search and independently assessed articles for inclusion according to the above criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors (MA, RK, SK) independently extracted data using a piloted standardised data collection sheet. These data were entered into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). The review authors were not blinded to authors of included studies. The two review authors resolved disagreements by discussion or, if necessary, by consulting a third review author in order to reach consensus. Data were sought per participant or randomised cluster (nursing home) on all outcome measures of interest for all assessment points (including baseline). We extracted data for characteristics of participants, baseline data, interventions, duration of intervention, length of follow‐up, outcome measures, and adverse events.

We retrieved data on research processes of the development, piloting, and evaluation of the complex interventions on the basis of Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2) (Möhler 2015). Criteria comprise developmental details like the description and intensity of the components, feasibility, and piloting, as well as evaluation of the complex intervention. We also extracted data on the fidelity of the intervention implementation.

If, as was frequently the case, no sufficient information on the above‐mentioned issues was available from included publications, we attempted to obtain additional information by contacting authors of the primary studies (e.g. by asking about related publications). Following earlier suggestions (Lenz 2007), we performed additional extra searches for publications related to included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Our assessment of risk of bias followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Two review authors (MA, RK) independently assessed and scored studies in order to identify any potential sources of systematic bias through selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, or detection bias as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook addressing six domains (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other issues). We assigned a judgement concerning the related risk of bias for each domain, either 'low risk', 'high risk', or where insufficient information was available to make a judgement, 'unclear risk'. In addition, we assessed recruitment bias for cluster‐randomised trials, that is whether individuals were recruited after clusters had been randomised. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study and presented the results graphically.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data (e.g. plaque indices), we used the mean difference (MD) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) if the same instrument was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different instruments were used for the same outcome measure. For dichotomous data (e.g. incidence of respiratory disease), we used risk ratio (RR). We sought and recorded the absolute numbers in each group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest.

Unit of analysis issues

For each study we considered whether groups of individuals were randomised in clusters or individually, whether individuals underwent more than one intervention, and whether there were multiple observation times for the same outcome. As results from more than one time point per study cannot be combined in meta‐analysis, depending on the reported follow‐up periods of included studies, we performed subgroup analyses for studies with short‐term and long‐term follow‐up (Higgins 2011), only using the longest. For cluster RCTs we checked whether results were cluster‐adjusted. For combined meta‐analyses of individual and cluster‐RCTs, we estimated 'effective sample sizes' for cluster‐RCTs as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sections 16.3.4 to 16.3.7) (Higgins 2011). We aimed to use intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) as reported in included studies. As no ICCs were reported in included studies, or values seemed unrealistically high, we considered a conservative estimate of ICC = 0.05 based on experience from studies on caries (personal communication with Cochrane Oral Health).

Dealing with missing data

Where data were missing from the published report of a trial, we contacted authors to obtain the data and to clarify any uncertainties. Analyses included only available data (ignoring missing data). However, we used methods for estimating missing standard deviations if necessary (Higgins 2011). Otherwise, we did not undertake any imputation techniques or use statistical methods to account for missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity statistically and quantified it among trials included in each analysis using the I² statistic. We followed the guidance of the Cochrane Handbook to interpret the I² statistic, with I² greater than 50% representing substantial heterogeneity and greater than 75% representing considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). To assess clinical heterogeneity, we analysed all studies in terms of interventions, participants, and outcomes.

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to minimise the risk of publication bias, we performed comprehensive searches in multiple databases, including searching for unpublished studies. Due to the small number of included trials, we did not use a funnel plot to assess the likelihood of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We grouped studies according to interventions. For each intervention type, we performed meta‐analyses if we considered the studies to be reasonably clinically and methodologically homogeneous. We used random‐effects models for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses for the outcomes dental and denture plaque:

intervention recipient (nursing staff only versus nursing staff and residents);

follow‐up period (short term versus long term);

education in the context of guideline implementation versus education without guideline implementation.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed no sensitivity analyses.

Presentation of main results

We have displayed results in a 'Summary of findings' table for the primary outcomes, using GRADEpro software (GRADE 2014), according to the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Section 11.5) (Higgins 2011). We assessed the quality of the evidence with reference to overall risk of bias of included studies, directness of the evidence, consistency of results, and precision of estimates. We categorised the quality of the evidence for each of the primary outcomes as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

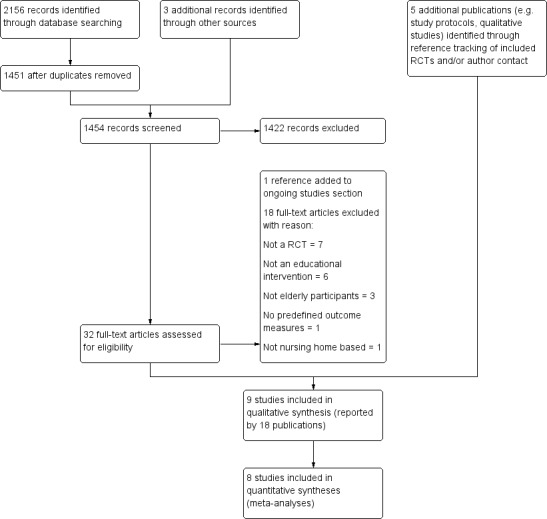

We screened a total of 1454 abstracts for inclusion (Table 2; Figure 1), and assessed 37 publications in full text. Eighteen publications reporting nine trials fulfilled the eligibility criteria (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013).

1. Search results.

| Database | First search date | Records retrieved (excl. duplicates) | Top‐up search | Records retrieved (excl. duplicates) | Top‐up search | Records retrieved (excl. duplicates) |

| Cochrane Oral Health Trials' Register | 31 July 2013 | 567 | 27 January 2015 | 123 | 18 January 2016 | 51 |

| CENTRAL via the Cochrane Library | 31 July 2013 | 164 | 27 January 2015 | 29 | 18 January 2016 | 10 |

| MEDLINE via OVID | 31 July 2013 | 509 (with RCT filter) | 27 January 2015 | 42 (with RCT filter) | 18 January 2016 | 33 (with filter) |

| Embase via OVID | 31 July 2013 | 214 (with RCT filter) | 27 January 2015 | 51 (with RCT filter) | 18 January 2016 | 18 (with filter) |

| CINAHL via EBSCO | 31 July 2013 | 94 (with RCT filter) | 27 January 2015 | 11 (with RCT filter) | 18 January 2016 | 8 (with filter) |

| Web of Science Conference Proceedings | 31 July 2013 | 151 | 27 January 2015 | 6 | 18 January 2016 | 3 |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | 31 July 2013 | 22 | 27 January 2015 | 23 | 18 January 2016 | 24 |

| WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform | Not performed | ‐ | 27 January 2015 | 3 | 18 January 2016 | 0 |

RCT: randomised controlled trial WHO: World Health Organization

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included two individual RCTs, Bellomo 2005 and Zenthöfer 2013, and seven cluster‐RCTs (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013), with a total of 3253 nursing home residents as participants.

Funding sources

All but two studies stated information about any kind of funding, for example financial or material support (Bellomo 2005; Schou 1989). One of these studies stated that they received funding for data collection from a commercial source (De Visschere 2011). One study received support from a commercial source in the form of free oral healthcare material (Zenthöfer 2013). Two studies obtained grants from non‐commercial sources (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007). The remaining three studies received grants from non‐commercial sources as well as free oral hygiene products from commercial sources (De Visschere 2012; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013).

Setting

All studies were based in nursing homes. However, in Schou 1989, the included institutions were described as "institutions for elderly". MacEntee 2007 only recruited intermediate‐care residents. In Zenthöfer 2013, participants were recruited from institutions for elderly (including assisted accommodation). All of the studies except MacEntee 2007 were conducted in Europe.

Recipients of the educational intervention

In five studies, the target groups of the educational interventions were nursing home staff (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013). More precisely, two studies aimed to include solely nursing staff (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007), and three studies focused on managerial and nursing staff (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013). Four studies examined interventions that comprised components for both nursing home staff and residents (Bellomo 2005; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Zenthöfer 2013).

The mean resident age ranged from 78.3 to 86.0 years across studies. Most participants were women (more than 66% in all studies). The proportion of residents with dental prostheses ranged from 62.1% to 87.3% across studies. Mean number of natural teeth varied between 4.7 and 17.4 at baseline, and the proportion of edentulous residents had a wide range, from 32.4% to 89.9% (see Characteristics of included studies). Two studies reported information about cognitive status or mental health, or both (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013). In four studies, cognitive impairment or dementia, or both was an exclusion criterion (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013). In De Visschere 2012, cognitive impairment tested by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE less than 26) was present in 86.5% of the sample. In Van der Putten 2013, 47% of participants in the intervention group and 58% in the control group had a diagnosis of dementia.

Some information on characteristics of participating nursing staff was reported in all studies except Bellomo 2005 and Schou 1989. The two studies examining knowledge and attitudes of nursing staff reported the most detailed description of the characteristics of the employed nursing staff (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001). In both studies, approximately 95% of nursing staff were female. In Frenkel 2001, the median length of work experience was four years, and about 67% reported attending a dentist at least once a year. In De Visschere 2012, nursing staff had been employed for a mean of 13.5 years; 62% were nurses and 38% auxiliary nurses. About 78% reported attending a dentist at least once a year. In addition, this study provided detailed information about the amount and numbers of staff members with previous education or skills training in oral health care. Five studies included nurses as well as nurse assistants (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). Five studies reported the number or proportion of intervention group staff attending the educational sessions. In Frenkel 2001, 65.6% of caregivers attended the educational session. In MacEntee 2007, the proportion of care‐aides attending the educational session in the intervention group and control group was 15% and 22%, respectively. De Visschere 2012 reported a 100% response rate (8 to 12 people per home). In Mojon 1998, the education course was attended by 76% of the caregivers. In Zenthöfer 2013, the number ranged from 20 to 40 people per nursing home.

Duration of follow‐up

Follow‐up for six studies ranged from three months, in Bellomo 2005, MacEntee 2007, and Zenthöfer 2013, to six months (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Van der Putten 2013); we categorised this as short term. Follow‐up for three studies ranged from nine months, in Schou 1989, to five years (De Visschere 2011); we categorised this as long term.

Description of interventions

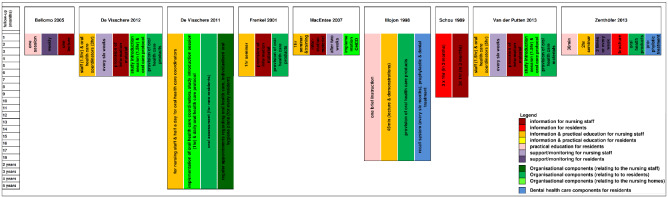

Studies differed in terms of intervention components as well as target groups. In all studies, the oral health educational intervention consisted of more than one component (see Figure 2). In all but one study (Bellomo 2005), nursing staff participated in one or more educational sessions. In eight studies, the intervention comprised education including theoretical information and skills training (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). In one study (Schou 1989), the educational intervention focused solely on theoretical information.

2.

Intervention components

Educational interventions with information and practical components (n = 8)

In Bellomo 2005, the long‐term care home residents received occupational therapy instruction on tooth and denture brushing. In addition, a subgroup of residents needing assistance were monitored weekly and, if necessary, re‐educated by an occupational therapist. De Visschere 2011 implemented a daily oral hygiene protocol. The implementation process included a half‐day theoretical and practical educational session for oral health co‐ordinators who had to educate the other nursing staff and prepare individualised oral hygiene plans for all residents. In two studies, the supervised implementation of an oral health guideline for older people in long‐term care institutions included theoretical and practical education sessions ranging from one to two hours for several groups of nursing home staff, using a train‐the‐trainer concept, and a daily oral healthcare protocol (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013). In Frenkel 2001, care assistants were educated by an experienced health promoter in a one‐hour session that consisted of a theoretical section on the role of plaque, oral diseases and a practical section with oral hygiene skills training. MacEntee 2007 used a "pyramidal education" approach to train the nursing staff of the intervention homes. Initially, a permanent member of the nursing staff was trained and installed as a nursing educator, who then trained the care‐aides in a single one‐hour seminar, which included a theoretical section (photographs and texts) and demonstrations of how to examine and clean the mouth. In addition, the nurse educators had to manage the oral health care provided by the care‐aides and were supported by the dental hygienist on request. In Mojon 1998, nursing staff took part in an interactive lecture (45 minutes) with slides and demonstration of brushing techniques. Every nurse or nurse aide received personalised oral hygiene instructions for their residents from a dental hygienist. Also, residents received brief (personalised) oral hygiene instructions from a dental hygienist. In addition, for residents, dental or prophylactic treatment including scaling at the start of the study and the implementation of a recall system were applied in the intervention group. In Zenthöfer 2013, the basic intervention for the three intervention groups consisted of a two‐hour session (PowerPoint presentation, a film) with dental demonstration models to train nursing staff. Residents received instruction and training on oral hygiene skills according to their specific needs. The residents of two of the three intervention groups were supported either by a dentist (re‐instruction and motivation after four and eight weeks) or by caregivers (provision of help twice a week using a standardised procedure). In addition, professional cleaning of dentures and teeth was performed for all intervention groups at the beginning.

Additional informational material on oral health and hygiene was provided to trained staff in four studies (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013) and to residents in one study (Zenthöfer 2013). Toothbrushes and/or other oral healthcare products were provided for intervention group residents in four studies (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013).

Educational interventions with information only (n = 1)

Schou 1989 only used education without further practical components. Nursing staff and residents took part in a dental health education programme using the "active involvement principle". Each intervention group (one for residents only, one for nursing staff only, and a combined one) met three times for one hour in a monthly interval to talk about dental health and individual experiences with oral health prevention procedures. Sessions were conducted by a dental hygienist who planned the content of the sessions in co‐operation with the participants.

Theoretical basis for intervention

Five studies provided at least some information on the interventions’ theoretical background. MacEntee 2007 based the intervention on a "pyramidal scheme" that evolved from the "helper principle" (Jones 1977; Riessman 1965). Schou 1989 used the "active involvement principle" for the dental education programme, which had been examined with positive results in another population (Schou 1985). Frenkel 2001 did not mention underlying theories, but based the intervention on previous research and her own qualitative study (Frenkel 1999). Two studies used a guideline implementation theory (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013). In four studies, no theoretical basis was mentioned (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013).

Content

Instructions and training of oral hygiene skills for residents included brushing techniques (tooth and dentures) (Bellomo 2005; Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013), and in some cases also handling of tooth/interdental space brushes, and advice on other auxiliaries, for example mouth rinses (Zenthöfer 2013). Training or demonstrations for nursing staff covered the same aspects (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013).

The theoretical sessions covered the following topics:

specifics of gerodontology/geriatric dentistry (e.g. MacEntee 2007; Zenthöfer 2013);

dental and oral diseases (e.g. Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Zenthöfer 2013);

prevention of oral diseases (e.g. Mojon 1998);

dental hygiene auxiliaries and handling (e.g. Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013);

handling of removable dentures (e.g. Zenthöfer 2013);

oral healthcare guideline or daily oral healthcare protocol, or both (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013).

Educators

The educational sessions for nursing staff were given by dentists (Zenthöfer 2013), dental hygienists (MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989), trained nursing staff (so‐called oral health co‐ordinators, ward oral healthcare organisers, nurse educators) (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013), and health promoters (Frenkel 2001). In studies that used a pyramidal or train‐the‐trainer concept, a combination of the aforementioned professions was involved in the educational components (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013).

Oral hygiene education or skills training for residents was provided by different professions including dental hygienists and occupational therapists (Bellomo 2005; Schou 1989; Zenthöfer 2013). Instructions on oral hygiene to nursing home residents were provided individually (Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013).

Presentation mode

Seven studies made use of more than one presentation mode for educational sessions. Four studies combined theoretical and practical sections for the educational sessions (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013). Three studies used a combination of oral presentations, lectures, PowerPoint presentations, and practical sessions of differing length (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013).

Duration and frequency

Not all studies specified the duration and frequency of the educational interventions or their different components.

Zenthöfer 2013 reported the duration of oral health instructions or skills training for nursing home residents as 30 minutes. In Schou 1989, oral health education for residents comprised three one‐hour sessions at monthly intervals. Re‐instruction or re‐education for residents took place weekly in Bellomo 2005. The frequency in Zenthöfer 2013 varied between the two intervention groups: residents received re‐instruction twice a week or after four and eight weeks.

The reported session duration for nursing staff ranged from 45 minutes, in Mojon 1998, to three hours (Schou 1989). The length for the training sessions for oral health co‐ordinators (train‐the‐trainer) varied from three to five hours and was not reported in two studies. The oral health co‐ordinators were supported by a dental hygienist two weeks after study start, in MacEntee 2007, or every six weeks (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013).

Control groups

One study included a control intervention that was similar in time and effort to the active intervention (Bellomo 2005). In MacEntee 2007, the control group received the same seminar (with photographs, texts, demonstrations), but education was provided by the dental hygienist. In the other studies (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013), no intervention was offered to the control group. Four studies specified usual care. In two of these studies, usual care implied oral health care according to the unsupervised implementation of a guideline (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013). De Visschere 2011 used a control group with residents receiving usual oral care in control homes and another group with residents living in intervention homes, but who did not receive the intervention, and in Mojon 1998, usual care meant that prior to the study no oral hygiene care was provided by the caregivers on a regular basis; cleaning of the teeth only took place if requested by the dentist; and oral care was provided by a dentist only at request of the resident, family, or caregivers.

Measured outcomes

Oral health‐related quality of life

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Oral health

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Dental health

This includes dental or denture plaque, inflammation of oral mucosa, and caries. The measures assessed and instruments used are shown in Table 3.

2. Summary of dental health outcomes assessed.

| Dental plaque | Denture plaque | Gingivitis | Caries | |

| Bellomo 2005 | PI | Index for plaque accumulation (Denture Plaque Index) by Ambjørnsen 1982 | Not assessed | Not assessed |

| De Visschere 2011 | PI (PO) | Method of Augsburger 1982 (PO) | Not assessed | Not assessed |

| De Visschere 2012 | PI (PO) | Method of Augsburger 1982 (PO) | Not assessed | Not assessed |

| Frenkel 2001 | OHI‐S (PO) | Method of Augsburger 1982 (PO) | Gingivitis (Suomi 1968) (PO) Denture‐induced stomatitis (Budtz‐Jørgensen 1970) (PO) |

Root caries* (SO) |

| MacEntee 2007 | GDI‐S (PO) | Not assessed | GBI* (PO) | Not assessed |

| Mojon 1998 | PI (PO) | Not assessed | Denture‐induced stomatitis (Budtz‐Jørgensen 1970) (PO) | Caries* (PO) Root caries* (PO) |

| Schou 1989 | Not assessed | Index for plaque accumulation (Denture Plaque Index) by Ambjørnsen 1982 (PO) | Denture‐induced stomatitis (Budtz‐Jørgensen 1970) (PO) | Not assessed |

| Van der Putten 2013 | PI (PO) | Method of Augsburger 1982 (PO) | Not assessed | Not assessed |

| Zenthöfer 2013 | Plaque‐control record* (PO) | DHI* (PO) | GBI* (PO) | Not assessed |

| PO: primary outcome measure; SO: secondary outcome measure. DHI: Denture Hygiene Index; GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index; GDI‐S: Geriatric Simplified Debris Index; OHI‐S: Simplified Oral Hygiene Index; PI: Plaque Index | ||||

*Dichotomously assessed.

All studies except Schou 1989 provided information on assessment of dental plaque. Seven studies used a four‐point (0 to 3) plaque scale based on the Plaque Index described by Silness 1964 (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013), or the (simplified) Oral Hygiene Index (OHI‐S) by Greene 1964 (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007). Six studies reported mean dental plaque, and one median dental plaque (Mojon 1998). In Zenthöfer 2013, dental plaque was assessed dichotomously using the "plaque‐control record". We were able to meta‐analyse up to six studies on dental plaque depending on subgroups (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013).

Seven studies reported on denture plaque (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). Denture plaque was assessed in four studies using a five‐point scale (0 to 4) described by Augsburger 1982 (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013), and in two studies using a four‐point scale (0 to 3) described by Ambjørnsen 1982 (Bellomo 2005; Schou 1989). A further study used the Denture Hygiene Index to assess presence or absence of denture plaque (Zenthöfer 2013). The authors were unable to provide usable data, so we were unable to include results in meta‐analyses (Zenthöfer 2013). We included data from five studies in meta‐analyses comparing educational interventions including information and practical components with (optimised) usual care (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Van der Putten 2013).

Five studies reported data on inflammation of oral mucosa such as gingivitis, in Frenkel 2001, MacEntee 2007, and Zenthöfer 2013, or denture stomatitis (Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989). Two studies assessed gingivitis dichotomously applying the Gingival Bleeding Index (MacEntee 2007; Zenthöfer 2013). Mean gingivitis scores were reported by Frenkel 2001 using the method of Suomi 1968. Denture stomatitis was classified and scored according to the erythema severity (Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989). Due to the fact that the studies used different outcomes and measures for inflammation of oral mucosa, we were unable to use the data for meta‐analyses.

Two studies reported data on root caries (Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998). In Frenkel 2001, root caries were assessed on a binary scale as absent/present and reported as median score. Mojon 1998 reported active root caries as percentage of the total number of natural teeth.

Nutritional status

Only one study reported clinical measures of nutritional status (MacEntee 2007). The BMI was determined for every resident and binarily coded, with a score of less than 23 suggesting undernourishment. The Malnutrition Indicator Score (range 0 to 30, higher scores indicate better nourishment) as part of the Mini Nutritional Assessment was assessed, and mean scores were reported.

Incidence of respiratory diseases and pneumonia

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Adverse effects

None of the studies reported this outcome.

Oral health‐related knowledge

Two studies reported oral health‐related knowledge of nursing staff (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001), assessed by self administered questionnaires reporting true/false responses to 26 statements, in Frenkel 2001, or 15 statements, in De Visschere 2012. The authors of a further study confirmed that this outcome was measured, but data are currently unavailable (Van der Putten 2013). We were able to combine data of two studies on staff knowledge (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001). None of the studies reported oral health‐related knowledge of residents.

Oral health‐related attitude

Three studies assessed oral health‐related attitude of nursing staff (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Van der Putten 2013). Self administered questionnaires were applied with four statements using a three‐point Likert scale (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013), or with 25 statements using a five‐point Likert scale (Frenkel 2001). We were able to combine the data of two studies (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001), with data from the third study currently unavailable (Van der Putten 2013). No study reported oral health‐related attitude of residents.

Oral health‐related behaviour

One study assessed oral health‐related behaviour of residents (Bellomo 2005). An in‐depth structured interview with the residents was taken to obtain information about toothbrushing habits and used dental hygiene auxiliaries.

Excluded studies

We excluded 18 studies: seven were non‐randomised; six had no educational component; three included students or adults; one was not nursing home based; and one assessed no predefined outcomes (see Characteristics of excluded studies; Figure 1).

Ongoing studies

We identified one ongoing study assessing the effects of an intervention combining "best mouth care practices" with behavioural techniques (Jablonski 2011). Participants are nursing home residents with any kind of diagnosed dementia. The primary outcome measure is the reduction in care‐resistant behaviour. Oral health using the "Oral Health Assessment Tool" is assessed as the secondary outcome.

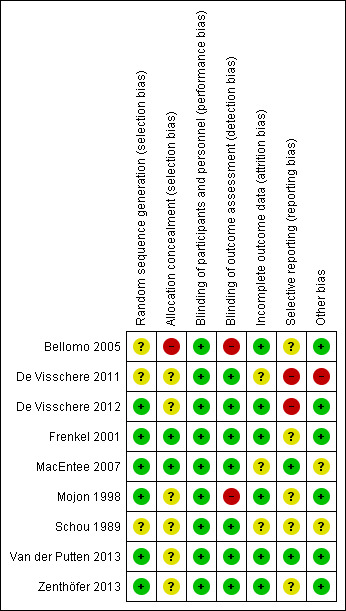

Risk of bias in included studies

We contacted the first or senior authors of all studies and asked them to provide further information on methodological details not reported in the publications. All authors responded to our requests, with all but one author being able to provide further information.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Three studies described an adequate method of random sequence generation (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Zenthöfer 2013). The authors of two studies responded to our requests for further information (MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998), which clarified that their methods were adequate. In addition, random sequence generation was probably done in one study since the investigators described an adequate method for another study based on one protocol (Van der Putten 2013). We therefore assessed six studies as being at low risk of bias for this domain. The remaining three studies only stated that participants were randomised but did not describe their methods, and so were assessed as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; Schou 1989).

Allocation concealment

Two studies provided details of how the random sequence was concealed from those involved in the study (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007). One author stated on request that allocation was not concealed, and so we assessed the study as at high risk of bias for this domain (Bellomo 2005). The remaining six studies did not mention any methods used to conceal the random sequence, and we therefore assessed them as being at unclear risk of bias (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

In educational interventions, blinding of participants is often not possible, but the relevance of lack of blinding varies according to circumstances. Lack of blinding of study participants or staff, or both, may affect outcomes (Higgins 2011, Chapter 8.4.2), especially if outcomes are self reported, as for example self assessed oral health‐related quality of life. Only one study reported blinding of participants (MacEntee 2007). We judged all nine studies to be at low risk of performance bias, given that we considered the influence of residents' and staff awareness on oral health behaviour to be negligible.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Seven studies reported blinded outcome assessment, and we rated them as at low risk of bias for this domain (De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). We assessed two studies as being at high risk of bias (Bellomo 2005; Mojon 1998): in one study, the author stated on request that the outcome assessor was not blinded (Bellomo 2005), and in the other study, blinding was not possible for practical reasons (Mojon 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed six studies as being at low risk of bias for this domain because attrition was low considering the special characteristics of the study population (especially high morbidity), and was roughly equal between groups (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). We assessed three studies as at unclear risk (De Visschere 2011; MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989).

Selective reporting

We assessed two studies as being at low risk of selective reporting bias as we could detect no obvious problems (MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013). However, reports of the preplanned outcomes oral health‐related knowledge and attitude are still under preparation (Van der Putten 2013). Data reported by De Visschere 2012 differed to some extent from the data in the trial registration (tongue coating was not preplanned), and results of De Visschere 2011 were not available for all preplanned outcome periods. We rated both studies as having a high risk of bias. We rated the remaining five studies as having an unclear risk of bias due to unavailable protocols or trial registrations (Bellomo 2005; Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Schou 1989; Zenthöfer 2013).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed the trials for other potential sources of bias such as recruitment bias in cluster‐randomised trials or contamination.

Seven of the included trials were cluster‐randomised trials, using nursing homes as the unit of randomisation. In one trial, it was clear that nursing homes residents gave informed consent or were examined at baseline after randomisation (De Visschere 2011), resulting in a high risk of bias. In addition, there was potential contamination between groups in this study (De Visschere 2011). Four trials were at low risk of bias (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013), and the other trials provided insufficient information, resulting in a judgement of unclear risk of bias (MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989).

Overall risk of bias

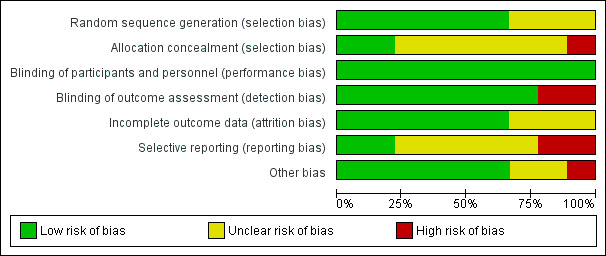

No study showed overall low risk of bias. Four studies had a high risk of bias (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Mojon 1998). The other five studies were at unclear risk of bias (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). See Figure 3; Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

5.

Summary of included studies

Comparison 1: Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care

Six out of eight trials for this comparison presented data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analyses. First, we have presented our analysis comprising the primary outcomes dental plaque and denture plaque. We have presented subgroup analysis for:

intervention recipient (nursing staff only versus nursing staff and residents);

follow‐up period (short term versus long term);

education in the context of guideline implementation versus education without guideline implementation (limited to short‐term follow‐up).

We have presented results for gingivitis, denture‐induced stomatitis, caries, secondary outcomes, and oral health‐related behaviour in a narrative form.

Primary outcomes

Oral health‐related quality of life

Not measured in the included studies.

Oral health

Not masured in the included studies.

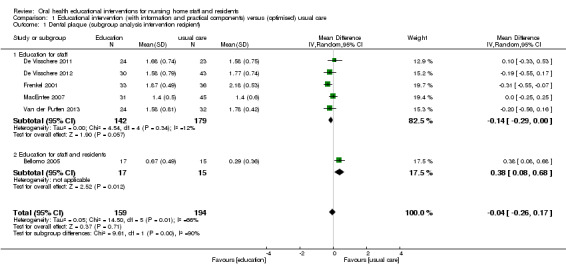

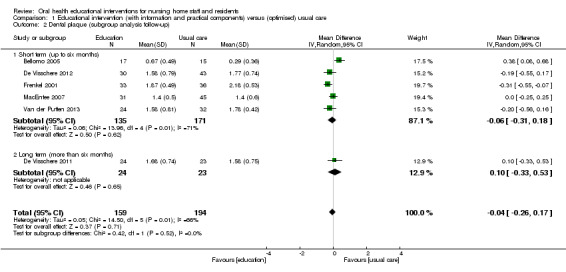

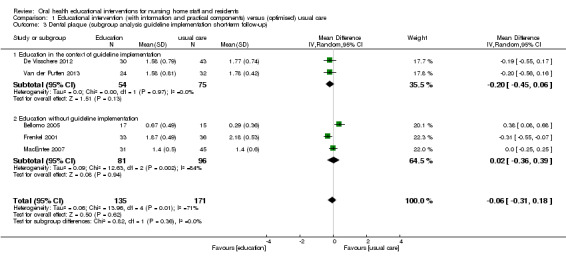

Dental plaque

We meta‐analysed six studies (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Van der Putten 2013), three at high and three at unclear risk of bias, involving 437 nursing home residents. Dental plaque scores did not differ between residents who were cared for by nursing staff educated in oral health and than those receiving usual care (mean difference (MD) ‐0.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.26 to 0.17; P = 0.71; effective sample size N = 353) (Analysis 1.1). There were no apparent subgroup differences for follow‐up periods (Analysis 1.2) or education in context of guideline implementation (Analysis 1.3). The subgroup analysis for educational intervention recipients showed a positive result in favour of interventions providing education for nursing staff only compared to education for staff and residents (P = 0.002), but results should be viewed with caution as there was only one study in the second category (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 1 Dental plaque (subgroup analysis intervention recipient).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 2 Dental plaque (subgroup analysis follow‐up).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 3 Dental plaque (subgroup analysis guideline implementation short‐term follow‐up).

We were unable to include two studies in this meta‐analysis (Mojon 1998; Zenthöfer 2013), which had high and unclear risk of bias, and involved 148 participants. In Mojon 1998, there was an increase in the median dental plaque scores for both groups (0.06 in the intervention group, 0.25 in the control group), a non‐significant difference (P = 0.06). In Zenthöfer 2013, dental plaque was assessed dichotomously, demonstrating lower mean percentages of plaque‐positive dental sites in three intervention groups compared to usual care (no P values reported).

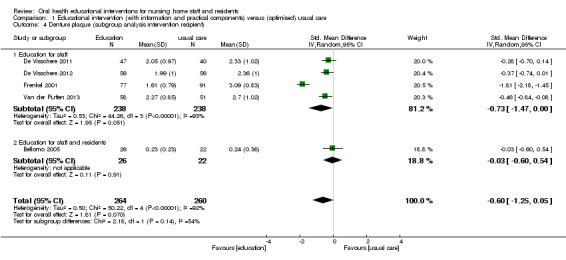

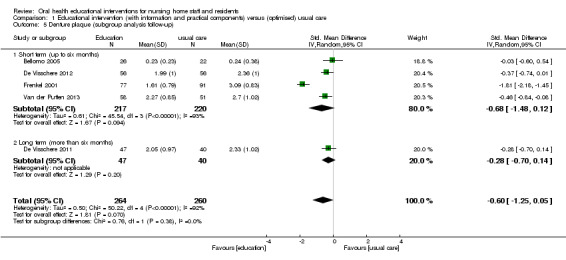

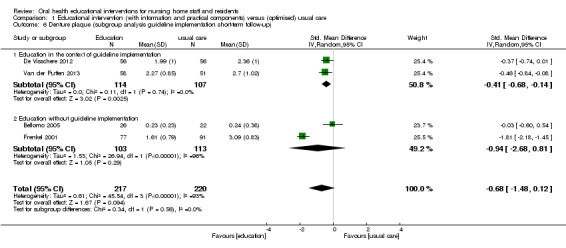

Denture plaque

We combined five studies, involving 816 nursing home residents, in a meta‐analysis. Three of the studies were at high risk of bias (Bellomo 2005; De Visschere 2011; De Visschere 2012), and two were at unclear risk of bias (Frenkel 2001; Van der Putten 2013). Denture plaque scores were not lower for residents who were cared for by nursing staff educated in oral health compared to residents receiving usual care (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.25 to 0.05; P = 0.07; effective sample size N = 524) (Analysis 1.4). Subgroup analyses for educational intervention recipient, follow‐up period, and education in the context of guideline implementation showed no significant differences (Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 4 Denture plaque (subgroup analysis intervention recipient).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 5 Denture plaque (subgroup analysis follow‐up).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 6 Denture plaque (subgroup analysis guideline implementation short‐term follow‐up).

Zenthöfer 2013, which included 89 participants and was at unclear risk of bias, did not provide adequate data for meta‐analysis. Denture plaque was assessed dichotomously, and trial authors reported a lower mean percentage of plaque‐positive denture sites in intervention groups compared to usual care (no P values reported).

Gingivitis

Three studies with short‐term follow‐up (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Zenthöfer 2013), all at unclear risk of bias, assessed gingivitis in residents, but we were unable to pool the data. Frenkel 2001 analysed 79 residents and showed a statistically significant difference in mean gingivitis score in favour of the intervention group (adjusted MD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.15; P < 0.001). In Zenthöfer 2013, which analysed 68 residents, the mean values for the Gingival Bleeding Index were lower in intervention groups one (8.5, standard deviation (SD) 11.9), two (7.4, SD 8.7), and three (20.7, SD 23.9) compared to the control group (21.8, SD 27.5) (P values not reported/not calculated). MacEntee 2007 analysed 98 residents and showed no significantly different scores for gingivitis between intervention and control (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐7.3 to 7.0; P = 0.48).

Denture‐induced stomatitis

Frenkel 2001, which involved 258 residents and was at unclear risk of bias, assessed severity of denture‐induced stomatitis. Stomatitis was reduced in the intervention group at six months' follow‐up compared to the control group (P < 0.0001). Mojon 1998, with 159 residents, assessed the incidence of mucosal and other lesions. There was no significant difference between groups for incidence of denture stomatitis (37% versus 42.2%; P value not reported) or other lesions (18.5% versus 31.6%; P = 0.06), but for incidence of glossitis, the result was in favour of the intervention group (4.9% versus 25%; P = 0.005).

Caries and root caries

Two studies at unclear and high risk of bias assessed caries or root caries (Frenkel 2001; Mojon 1998). The individual studies showed no significant differences between intervention groups and control groups at both short‐term and long‐term follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

None of the included studies assessed incidence of respiratory diseases, pneumonia, or adverse effects. Only one study assessed nutritional status (BMI and Malnutrition Indicator Score), which had short‐term follow‐up and an unclear risk of bias (MacEntee 2007). There was no benefit related to BMI scores less than 23 for residents receiving the intervention (odds ratio 1.0, 95% CI 0.3 to 3.1; P = 0.49). The mean difference of Malnutrition Indicator Score (range 0 to 30) was ‐1.1 (95% CI ‐2.9 to 0.7; P = 0.11).

Intermediate outcomes

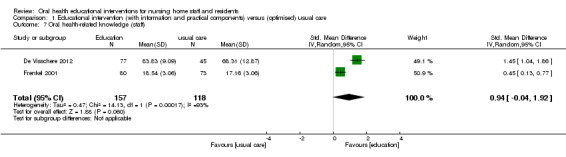

Oral health‐related knowledge

We combined two studies at high and unclear risk of bias involving 453 members of nursing staff in a meta‐analysis (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001). A non‐significant difference in knowledge was reported for nursing staff receiving educational interventions compared to those without education (SMD 0.94, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 1.92; P = 0.06) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 7 Oral health‐related knowledge (staff).

Oral health‐related attitude

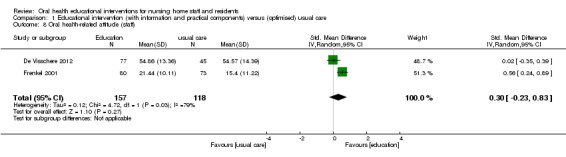

We combined two studies involving 459 members of nursing staff in a meta‐analysis (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001). A non‐significant difference in attitude was reported for nursing staff receiving educational interventions compared to those without education (SMD 0.30, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.83; P = 0.27) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Educational intervention (with information and practical components) versus (optimised) usual care, Outcome 8 Oral health‐related attitude (staff).

Oral‐health related behaviour

One study assessed oral health‐related behaviour of residents (Bellomo 2005). The 60 residents were interviewed about their toothbrushing habits. Use of toothbrushes and the frequency of brushing during the study period were comparable in both groups.

Comparison 2: Educational intervention (information only) versus usual care

One study (Schou 1989), at unclear risk of bias and analysing 114 residents, showed that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether or not denture plaque scores are lower when educating residents or nursing staff without practical training. There was no difference in the prevalence of denture stomatitis between the groups. The number of residents in the intervention groups who reported correct denture cleaning habits increased, but not significantly compared to baseline (baseline N = 28; follow‐up N = 38). The study did not assess any other outcomes of this review.

Reporting of complex interventions (CReDECI 2)

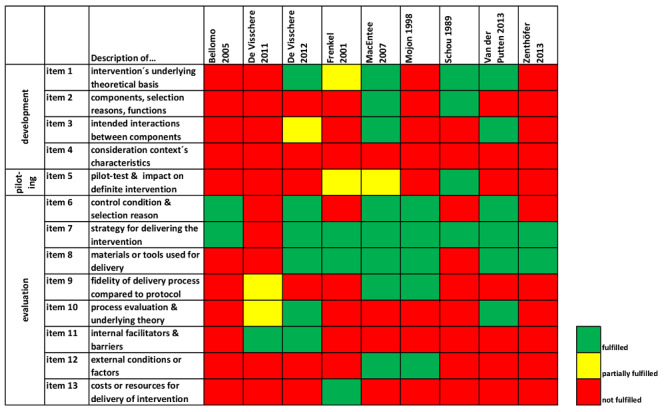

Findings for the reporting quality of complex interventions, using the CReDECI 2 checklist (Möhler 2015), are described in Table 4. Information about the development stage (four items) was rarely provided, as most studies failed to report reasons for selection of intervention components/essential function (item 2) or intended interactions between components (item 3). Five studies provided at least some information about the intervention's underlying theoretical basis (item 1) (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989; Van der Putten 2013). Only MacEntee 2007 and Schou 1989 considered item 2. None of the studies reported consideration of context characteristics in intervention modelling (item 4). Only three studies reported information on the feasibility and piloting stage (item 5) (Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Schou 1989). A description of the strategy for delivering the intervention (item 7) was reported in all but one study (De Visschere 2011). Six studies described the materials or tools used for the intervention delivery (item 8) (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; MacEntee 2007; Mojon 1998; Van der Putten 2013; Zenthöfer 2013). In two studies, the process evaluation (item 10) was planned a priori (De Visschere 2012; Van der Putten 2013), and in another two studies qualitative methods for identification of facilitators and barriers were mentioned (De Visschere 2011; MacEntee 2007). A description of costs or required resources for the delivery of the interventions was only provided in Frenkel 2001. Overall, most studies reported insufficient information on processes (Figure 6).

3. Evaluation of the included studies using the CReDECI 2 checklist.

| Bellomo 2005 | De Visschere 2011 | De Visschere 2012 | Frenkel 2001 | MacEntee 2007 | Mojon 1998 | Schou 1989 | Van der Putten 2013 | Zenthöfer 2013 | |

| Item 1: Description of the intervention’s underlying theoretical basis | No | No | Yes, guideline implementation theory; p. e97 & p. 2 | (Yes), qualitative data from previous research; p. 92 | Yes, pyramidal scheme (Jones 1977); p. 26 (Ref. 30‐35) | No | Yes, "active involvement principle"; (Ref. 14) | Yes, guideline implementation theory; p. 1144 & p. 2 | No |

| Item 2: Description of all intervention components, including the reasons for their selection as well as their aims/essential functions | No | No | No | No | Yes, p. 26 | No | Yes, p. 3 (& Ref. 14) | No | No |

| Item 3: Illustration of any intended interactions between different components | No | No | (Yes, p. e98) | No | Yes, p. 26 & 28 | No | No | (Yes), p. 1146 | No |

| Item 4: Description and consideration of the context’s characteristics in intervention modelling | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Item 5: Description of the pilot test and its impact on the definite intervention | No | No | No | (Yes), p. 92 | (Yes), research proposal (provided by the author on request) | No | Yes, Ref. 14 (modified intervention) | No | No |

| Item 6: Description of the control condition (comparator) and reasons for the selection | Yes, p. 26 | No | Yes, p. e97 | No | Yes, p. 28 | Yes, p. 828 | No | Yes, p. 1146 | No |

| Item 7: Description of the strategy for delivering the intervention within the study context | Yes, p. 26 | No | Yes, p. e98 | Yes, p. 290 & 92 | Yes, p. 27‐28 | Yes, p. ?? | Yes, p. 3 | Yes, p. 1146 | Yes, p. 262‐263 |

| Item 8: Description of all materials or tools used in the delivery of the intervention | No | No | Yes, p. e98 | Yes, p. 92 | Yes, p. 27‐28 (footnotes 2+3; restructured training material: bcdental.org/YourDentalHealth/YourDentalHealth.aspx?id=9974) |

Yes, p. 143 | No | Yes, p. 1146 | Yes, p. 263 & Ref. 19 |

| Item 9: Description of fidelity of the delivery process compared to the study protocol | No | (Yes), p. 419 | No | No | Yes, p. 30 | Yes, p. 830 | No | No | No |

| Item 10: Description of a process evaluation and its underlying theoretical basis | No | (Yes), p. 423 qualitative approach/publication mentioned | Yes, p. 5 | No | (Yes), research proposal MacEntee 2007 | No | No | Yes, p. 5 | No |

| Item 11: Description of internal facilitators and barriers potentially influencing the delivery of the intervention as revealed by the process evaluation | No | Yes, p. 423 (findings published in an additional publication p. 115‐122) | Yes, p. e102 results of process evaluation scantly mentioned (more information in a second publication p. 115‐122) | No | No (planned, but unfinished/unpublished) | No | No | No (publication in preparation) | No |

| Item 12: Description of external conditions or factors occurring during the study which might have influenced the delivery of the intervention or mode of action (how it works) | No | No | No | No | Yes, p. 31‐32 | Yes, p. 147 | No | No | No |

| Item 13: Description of costs or required resources for the delivery of the intervention | No | No | No | Yes, tab 4 on p. 294 | No | No | No | No | No |

6.

Summary of CReDECI 2: review authors' judgements of fulfilment of CReDECI 2 items for each included study

Discussion

Summary of main results

We have summarised results from nine RCTs, involving 3253 nursing home residents, investigating the effects of oral health educational interventions for nursing staff or nursing home residents, or both. All interventions were complex interventions that used more than one active component. We retrieved process measures and details of the development and evaluation of the complex interventions used, if available, using the CReDECI 2 criteria. The number of intervention components differed markedly between studies (Figure 2), but all interventions included theoretical or practical education sessions, or both, on oral health for nursing staff as one of the main intervention components. We categorised the interventions into two groups: educational intervention with information and practical components or educational intervention with information only. All trials aimed at improving different measures of dental health. Some were additionally concerned with increasing knowledge or improving attitude (De Visschere 2012; Frenkel 2001; Van der Putten 2013). Control interventions differed between studies, ranging from "usual care" to control interventions comparable to the active intervention in terms of time and effort spent.

None of the included studies assessed our primary outcomes oral health‐related quality of life and oral health. All studies assessed our third primary outcome dental health, although the outcome measures varied between studies (see Table 3). We found no clear beneficial effect on any dental health measure, and quality of the evidence was generally low.