Abstract

Background

Pre‐cancerous lesions of cervix (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)) are usually treated with excisional or ablative procedures. In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) cervical screening guidelines suggest that over 80% of treatments should be performed in an outpatient setting (colposcopy clinics). Furthermore, these guidelines suggest that analgesia should always be given prior to laser or excisional treatments. Currently various pain relief strategies are employed that may reduce pain during these procedures.

Objectives

To assess whether the administration of pain relief (analgesia) reduces pain during colposcopy treatment and in the postoperative period.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 2), MEDLINE (1950 to March week 3, 2016) and Embase (1980 to week 12, 2016) for studies of any design relating to analgesia for colposcopic management. We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared all types of pain relief before, during or after outpatient treatment to the cervix, in women with CIN undergoing loop excision, laser ablation, laser excision or cryosurgery in an outpatient colposcopy clinic setting.

Data collection and analysis

We independently assessed study eligibility, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We entered data into Review Manager 5 and double checked it for accuracy. Where possible, we expressed results as mean pain score and standard error of the mean with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and synthesised data in a meta‐analysis.

Main results

We included 19 RCTs (1720 women) of varying methodological quality in the review. These trials compared a variety of interventions aimed at reducing pain in women who underwent treatment for CIN, including cervical injection with lignocaine alone, lignocaine with adrenaline, buffered lignocaine with adrenaline, prilocaine with felypressin, oral analgesics (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), inhalation analgesia (gas mixture of isoflurane and desflurane), lignocaine spray, cocaine spray, local application of benzocaine gel, lignocaine‐prilocaine cream (EMLA cream) and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Most comparisons were restricted to single trial analyses and were under‐powered to detect differences in pain scores between treatments that may or may not have been present. There was no difference in pain relief between women who received local anaesthetic infiltration (lignocaine 2%; administered as a paracervical or direct cervical injection) and a saline placebo (mean difference (MD) ‐13.74; 95% CI ‐34.32 to 6.83; 2 trials; 130 women; low quality evidence). However, when local anaesthetic was combined with a vasoconstrictor agent (one trial used lignocaine plus adrenaline while the second trial used prilocaine plus felypressin), there was less pain (on visual analogue scale (VAS)) compared with no treatment (MD ‐23.73; 95% CI ‐37.53 to ‐9.93; 2 trials; 95 women; low quality evidence). Comparing two preparations of local anaesthetic combined with vasoconstrictor, prilocaine plus felypressin did not differ from lignocaine plus adrenaline for its effect on pain control (MD ‐0.05; 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.16; 1 trial; 200 women). Although the mean (± standard deviation (SD)) observed blood loss score was less with lignocaine plus adrenaline (1.33 ± 1.05) compared with prilocaine plus felypressin (1.74 ± 0.98), the difference was not clinically as the overall scores in both groups were low (MD 0.41; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.69; 1 trial; 200 women). Inhalation of gas mixture (isoflurane and desflurane) in addition to standard cervical injection with prilocaine plus felypressin resulted in less pain during the LLETZ (loop excision of the transformation zone) procedure (MD ‐7.20; 95% CI ‐12.45 to ‐1.95; 1 trial; 389 women). Lignocaine plus ornipressin resulted in less measured blood loss (MD ‐8.75 ml; 95% CI ‐10.43 to ‐7.07; 1 trial; 100 women) and a shorter duration of treatment (MD ‐7.72 minutes; 95% CI ‐8.49 to ‐6.95; 1 trial; 100 women) than cervical infiltration with lignocaine alone. Buffered solution (sodium bicarbonate buffer mixed with lignocaine plus adrenaline) was not superior to non‐buffered solution of lignocaine plus adrenaline in relieving pain during the procedure (MD ‐8.00; 95% CI ‐17.57 to 1.57; 1 trial; 52 women).

One meta‐analysis found no difference in pain using VAS between women who received oral analgesic and women who received placebo (MD ‐3.51; 95% CI ‐10.03 to 3.01; 2 trials; 129 women; low quality evidence).

Cocaine spray was associated with less pain (MD ‐28.00; 95% CI ‐37.86 to ‐18.14; 1 trial; 50 women) and blood loss (MD 0.04; 95% CI 0 to 0.70; 1 trial; 50 women) than placebo.

None of the trials reported serious adverse events and majority of trials were at moderate or high risk of bias (13 trials).

Authors' conclusions

Based on two small trials, there was no difference in pain relief in women receiving oral analgesics compared with placebo or no treatment (MD ‐3.51; 95% CI ‐10.03 to 3.01; 129 women). We consider this evidence to be of a low to moderate quality. In routine clinical practice, intracervical injection of local anaesthetic with a vasoconstrictor (lignocaine plus adrenaline or prilocaine plus felypressin) appears to be the optimum analgesia for treatment. However, further high quality, adequately powered trials should be undertaken in order to provide the data necessary to estimate the efficacy of oral analgesics, the optimal route of administration and dose of local anaesthetics.

Plain language summary

Pain relief for women with pre‐cancerous changes of the cervix (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)) undergoing outpatient treatment

What is the issue? Treatment for CIN is usually undertaken in an outpatient colposcopy clinic to remove the pre‐cancerous cells from the cervix (lower part of the womb). It commonly involves lifting the cells off the cervix with electrically heated wire (diathermy) or laser, or destroying the abnormal cells with freezing methods (cryotherapy). This is potentially a painful procedure.

The aim of the review The purpose of this review is to determine which, if any, pain relief should be used during cervical colposcopy treatment.

What evidence did we find?

We identified 19 clinical trials up to March 2016 and these reported different forms of pain relief before, during and after colposcopy. Evidence from two small trials showed that women having a colposcopy treatment had less pain and blood loss if the cervix was injected with a combination of a local anaesthetic medicine and a medicine that causes blood vessels to constrict (narrow), compared with placebo (a pretend treatment). Although taking oral pain‐relieving medicines (e.g. ibuprofen) before treatment on the cervix in the colposcopy clinic is recommended by most guidelines, evidence from two small trials did not show that this practice reduced pain during the procedure.

Quality of the evidence Most of the evidence was of a low to moderate quality and further research may change these findings.

Additionally, we were unable to obtain evidence with regards to how much of the local anaesthetic or method of administering local anaesthetic into the cervix.

What are the conclusions? There is a need for high quality trials with sufficient numbers of women in order to provide the data necessary to determine which pain relief should be used during outpatient colposcopy treatment.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women up to 65 years of age and is the most frequent cause of death from gynaecological cancers worldwide. A woman's risk of developing cervical cancer by the age of 65 years ranges from 0.69% in high income countries to 1.38% in low to moderate income countries (GLOBOCAN 2008). In Europe, about 60% of women with cervical cancer are alive five years after diagnosis (EUROCARE 2003). Cervical screening has all the characteristics of a good screening programme. There are effective screening tests, such as the traditional cytological approach (Pap smear) for diagnosing pre‐invasive and early invasive disease, or new methodologies, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, which try to improve sensitivity and specificity. In addition, there are effective surgical treatments for pre‐invasive and early invasive disease that dramatically alter prognosis. As cervical screening is relatively inexpensive, non‐invasive and treatment of pre‐invasive disease requires only simple surgical techniques, screening is cost‐effective and has been clearly demonstrated to reduce mortality in countries with well‐organised screening programmes (Peto 2004).

One previous Cochrane review examined the effectiveness of different modalities of treatment for pre‐invasive disease (Martin‐Hirsch 2010). In the review, each modality of treatment was assessed for its ability to eradicate disease and associated morbidity. Current treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is by local ablative therapy or by excisional methods, depending on the nature and extent of the disease. There is an international consensus that the majority of these procedures can be performed within the colposcopy clinic in an outpatient setting. In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) cervical screening guidelines suggest that over 80% of treatments should be performed in a clinic setting (NHSCSP 2004; NHSCSP 2010). Furthermore, these guidelines also suggest that analgesia should always be given prior to laser or excisional treatments.

Description of the intervention

Therapies that are available to treat pre‐malignant lesions of the cervix in outpatient settings include loop diathermy excision, laser ablation or excision, and cryotherapy (Martin‐Hirsch 2010). Studies have reported variable outcomes with different types of pain relief for these procedures. The choice of pain relief in these studies varies from no analgesia to intracervical infiltration with anaesthetic agent (e.g. lignocaine ‐ buffered and non‐buffered ‐ or prilocaine) with or without vasopressor agents (e.g. adrenaline or felypressin) (Lee 1986; Johnson 1989; Kizer 2014). Other methods studied are oral therapy with non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Frega 1994), local spray with cocaine (Mikhail 1988) or lignocaine (xylocaine) spray (Vanichtantikul 2013), topical benzocaine gel (Lipscomb 1995), inhalation of gas mixture of isoflurane and desflurane (Cruickshank 2005), local anaesthetic cream (EMLA cream) (Sarkar 1993), and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (Crompton 1992).

How the intervention might work

The possible mechanisms proposed in the literature to explain pain during cervical laser vaporisation includes pain mediated through peripheral pain fibres in the cervix, stimulated by heat energy, with or without pain caused by increased uterine contractions, probably because of the release of prostaglandins. The interventions may work by blocking the pain pathways. The nerve supply to the cervix is unclear, but the richest supply appears to be at the level of internal os. The ectocervix appears to be relatively insensitive to extremes of temperature with few specialised nerve fibres (Jordan 1976). Pain stimuli from the cervix and vagina are conducted by visceral afferent fibres to the S2 to S4 spinal ganglia via the pudendal and pelvic splanchnic nerves, along with parasympathetic fibres (Moore 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

There now appears to be a consensus that analgesia should be administered before treatment to the cervix. Currently, there is no systematic review or meta‐analysis evaluating whether administering analgesia reduces the pain experienced by women undergoing outpatient treatment. Most guidelines are also not explicit on the nature of optimum analgesia for intra‐ and postoperative pain relief. Analgesia is commonly administered intra‐ or para‐cervically using fine dental needles. Other routes of administering analgesics evaluated are TENS, peri‐operative NSAIDs and inhalation analgesia.

Objectives

To assess whether the administration of pain relief (analgesia) reduces pain during colposcopy treatment and in the postoperative period.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Women with CIN undergoing loop excision, laser ablation, laser excision or cryosurgery treatment of the cervix in an outpatient colposcopy clinic setting.

Types of interventions

All types of pain relief before, during or after outpatient treatment to the cervix, compared with no pain relief or another type of pain relief. We excluded studies that included treatment performed under general anaesthetic.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Presence or absence of pain, as a dichotomous outcome, or the degree of pain, measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) or categorical scales.

Secondary outcomes

Speed of procedure (in minutes).

Blood loss (either in millilitres (ml) or categorical scale as none, mild or minimal, heavy, troublesome or as dichotomous data).

Any moderate or severe adverse effects (dizziness, fainting, shaking, delayed discharge, etc.).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for papers in all languages and undertook translations if necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2016, Issue 2), MEDLINE (1950 to March week 3, 2016), Embase (1980 to week 12, 2016) for studies of any design relating to analgesia for colposcopic management. The electronic literature search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE are summarised in Appendix 1, Appendix 2, and Appendix 3, respectively.

We identified all relevant articles on PubMed and used the 'related articles' feature to search for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Registries of randomised trials

We searched the following registries for ongoing trials: Metaregister (www.controlled-trials.com), Physicians Data Query (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), www.clinicaltrials.gov, and www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials.

We used ZETOC to search conference proceedings and abstracts (zetoc.mimas.ac.uk).

Handsearching

We handsearched the citation lists of included studies, key textbooks, previous systematic reviews and reports of conferences in the following sources:

Gynecologic Oncology (Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncologist);

International Journal of Gynecological Cancer (Annual Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society);

British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Cytology (BSCCP) Annual Meeting.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (KG, AB) scanned the titles and abstracts (when available) of all reports identified through the electronic searches. For studies appearing to meet the inclusion criteria, or for which there were insufficient information in the title and abstract to make a clear decision, we obtained the full report. Two review authors (KG, AB) independently assessed the full reports obtained from all the electronic and other methods of searching to establish whether the studies met the inclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion. Where resolution was not possible, we consulted a third review author (PM‐H). All studies meeting the inclusion criteria underwent validity assessment and data extraction using a standardised proforma. We recorded studies rejected at this or subsequent stages in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, and recorded reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (KG, AB) independently extracted the data using specially designed data extraction forms. The data extraction forms were piloted on several papers and modified as required before use. We discussed any disagreements and consulted a third review author (PM‐H) when necessary. We contacted study authors for clarification or missing information if necessary and excluded data until further clarification was available or if we could not reach agreement.

For included studies, we extracted data as recommended in Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This included data on the following:

author, year of publication, country of origin, source of study funding and journal citation (including language);

setting;

details of the participants including demographic characteristics (e.g. age, co‐morbidities, etc.), total number enrolled, and criteria for inclusion and exclusion;

CIN details at diagnosis;

details of the type of intervention;

risk of bias in study (see below);

duration of follow‐up;

-

details of the outcomes reported (pain, blood loss, adverse events), including method of assessment, and time intervals (see below):

for each outcome: outcome definition (with diagnostic criteria if relevant);

unit of measurement (if relevant);

for scales: upper and lower limits, and whether high or low score was good;

results: number of participants allocated to each intervention group;

for each outcome of interest: sample size; missing participants;

the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported.

We extracted data on outcomes as below:

for dichotomous outcomes (e.g. pain, adverse events), we extracted the number of women in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of women assessed at endpoint, in order to estimate a risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI);

for continuous outcomes (e.g. blood loss), we extracted the final value and standard deviation (SD) of the outcome of interest and the number of women assessed at endpoint in each treatment arm at the end of follow‐up, in order to estimate the mean difference (MD) (if trials measured outcomes on the same scale) and 95% CI or standardised mean differences (if trials measured outcomes on different scales) between treatment arms and its standard error.

Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, in which participants were analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in included RCTs in accordance with guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool and the criteria specified in Chapter 8 (Higgins 2011). This included assessment of:

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding (of participants, healthcare providers and outcome assessors);

-

incomplete outcome data:

-

we recorded the proportion of women whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the study. We coded the satisfactory level of loss to follow‐up for each outcome as:

low risk of bias, if less than 20% of women were lost to follow‐up and reasons for loss to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms;

high risk of bias, if more than 20% of women were lost to follow‐up or reasons for loss to follow‐up were different between treatment arms;

unclear risk of bias, if loss to follow‐up was not reported;

-

selective reporting of outcomes;

other possible sources of bias.

Two review authors (KG, AB) independently applied the 'Risk of bias' tool and resolved differences by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (PM‐H). We summarised results in both a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. Results of meta‐analyses were interpreted with consideration of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment:

for dichotomous outcomes, we used the RR;

for continuous outcomes, we used the MD between treatment arms.

Unit of analysis issues

Two review authors (KG, AB) reviewed any unit of analysis issues according to Higgins 2011 and resolved differences by discussion.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for the primary outcome. If data were missing or only imputed data were reported, we contacted trial authors to request data on the outcomes only among women who were assessed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials that could not be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001), and, when possible, by subgroup analyses. If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we investigated and reported the possible reasons.

Data synthesis

We characterised each trial by its type of analgesia and route of administration. Furthermore, we classified the assessment of pain or any other outcomes on whether dichotomous or continuous outcomes were used. We performed meta‐analysis when the interventions, route of administration and outcome measures were clinically similar.

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the RR for each trial and then pooled them.

For continuous outcomes, we pooled the MDs between the treatment arms at the end of follow‐up if all trials measured the outcome on the same scale, otherwise we pooled standardised mean differences.

If any trials had multiple treatment groups, we divided the 'shared' comparison group into the number of treatment groups and comparisons between each treatment group and treated the split comparison group as independent comparisons.

We used random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting for all meta‐analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

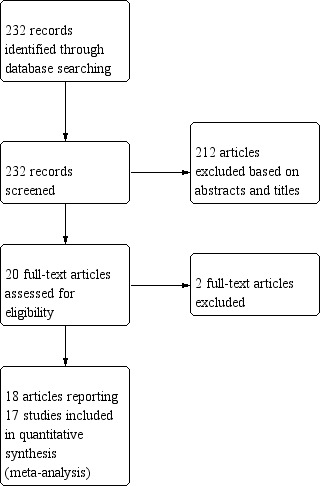

This review was first published in 2012 (Gajjar 2012). The original search strategy identified 232 unique references (Figure 1). Two review authors (KG, AB) screened the abstracts and articles that obviously did not meet the inclusion criteria and identified 20 articles as potentially eligible for inclusion in this Cochrane review. We performed full‐text screening of these 20 references and excluded two references for reasons described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The remaining 18 references pertaining to 17 completed RCTs met our inclusion criteria and are described in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1.

Study flow diagram of search results (September 2010).

For the 2016 review update, the search strategy identified an additional 109 unique references (Figure 2). After title and abstract screening these references, we retrieved four full‐text articles. We excluded one (Bogani 2014; see Characteristics of excluded studies table), and one study is awaiting classification until additional information is obtained from the study author (Diab 2015). Details of this study are described in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. We have contacted the author to request quantitative data and details of the measures used to quantify pain and anxiety, however, to date we have not received a reply. We included the remaining two studies in the review (Characteristics of included studies table).

2.

Study flow diagram of search results for review update April 2016.

Included studies

This updated review included the 17 trials from the original review (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Connell 2000; Crompton 1992; Cruickshank 2005; Diakomanolis 1997; Duncan 2005; Frega 1994; Howells 2000; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Lee 1986; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Rogstad 1992; Sammarco 1993; Sarkar 1993; Winters 2009), and two trials identified from the 2016 search (Kizer 2014; Vanichtantikul 2013). The 19 trials randomised 1753 women, and assessed 1720 at the end of the trials (Characteristics of included studies table; Table 4).

1. Overview of included studies.

| Study | Participants' characteristics | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

| Al‐Kurdi 1985 | 97 women, undergoing CO2 laser treatment for CIN Age: 18 to 50 years |

Intervention (n = 50): 2 tablets naproxen sodium 550 mg Comparison (n = 47): 2 placebo tablets Given no less than 30 minutes before procedure |

Pain relief: VAS on 10 cm scale; VRS (none, very slight, mild, moderate, severe) Speed of procedure Use of analgesia in first 24 hours |

Self reported adverse effects very minor (aches and pains at 24 hours) and not included in analysis |

| Connell 2000 | 30 women undergoing LLETZ Age: 20 to 64 years |

Intervention (n = 15): lignocaine hydrochloride 10% spray Comparison (n = 15): saline spray Both groups received 4.4 ml local anaesthetic (prilocaine hydrochloride 30 mg/ml + felypressin 0.54 µg/ml) in the cervix |

Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale; 4 point categorical scale 1 to 4 (1 = not painful; 2 = slightly painful; 3 = moderately painful; 4 = severely painful) |

Outcome reported on categorical scale was not included in the analysis |

| Crompton 1992 | 98 women undergoing CO2 laser treatment for CIN Linear analogue anxiety and HAD anxiety/depression personality trait scores (Zigmond 1983), age and parity recorded to assess group comparability 3 arm trial |

TENS (n = 34) TENS + direct infiltration of 2 ml lignocaine 2% + Octapressin (prilocaine 30 mg/ml + felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) 1:10,000 (0.03 IU/ml) (n = 29) Direct infiltration of 2 ml lignocaine 2% + Octapressin (n = 35) |

Pain relief: VAS on 120 mm scale | Median pain score on 120 mm VAS; however, authors converted it to percentage for reporting |

| Cruickshank 2005 | 389 women undergoing LLETZ treatment for CIN Age mean: intervention: 32.7 years; comparison: 31.5 years |

Intervention group (n = 195): isoflurane + desflurane gases Comparison (n = 194): placebo (air) Both groups received infiltration of the cervix with prilocaine hydrochloride (30 mg/ml) + Octapressin (prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) (0.54 mg/ml) |

Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale Heavy vaginal bleeding (yes/no) Anxiety using HAD scale |

Acceptability, satisfaction, helpfulness and willingness to undergo procedures in future ‐ not included in analysis |

| Diakomanolis 1997 | 100 women undergoing CO2 laser for CIN Age median: intervention: 28 years; comparison: 28.5 years |

Intervention (n = 50): 30 ml of 1:30 POR8 (vasoconstrictor) + lignocaine 1% solution Comparison (n = 50): 30 ml of lignocaine 1% solution |

Pain relief: VRS (none, moderate, severe) Intra‐operative blood loss Duration of procedure |

Adverse effects (transient hypertension and sweating) |

| Duncan 2005 | 97 women undergoing treatment with Semm coagulator Intervention: n = 46, mean age 31.3 years (SD 8.4); comparison: n = 47, mean age 32.6 years (SD 8.0) Nullipara: intervention: 14 (30.4%); comparison: 10 (21.3%) Married/cohabiting: intervention: 20 (43.5%); comparison: 22 (46.8%) CIN (1/2/3/unspecified) details (number (%)): intervention: HPV/CIN1 = 17/46 (37%), CIN2,3 = 29/46 (63%), microinvasion = 0/46; comparison: HPV/CIN1 = 17/47 (36.2%), CIN2,3 = 29/47 (61.7%), microinvasion = 1/47 (2.1%) |

Intervention (n = 46): 5 ml vials prilocaine 3% (30 mg/ml) + felypressin 0.03 IU/ml Comparison (n = 47): normal saline |

Pain relief: 11 point analogue scale ( 1 to 3, mild; 4 to 7, moderate; 8 to 10, severe pain) |

Details of anticipated pain excluded from the analysis |

| Frega 1994 | 63 women undergoing CO2 laser vaporisation for CIN 3 arm trial |

Intervention (n = 21): naproxen sodium 550 mg 30 minutes before treatment Comparison 1 (n = 21): placebo 30 minutes before treatment Comparison 2 (n = 21): no drug |

Pain relief: VAS 100 mm scale |

‐ |

| Howells 2000 | 200 women, aged 20 to 60 years, undergoing LLETZ for CIN (final histology negative intervention: 4/94 women; comparison: 8/106 women) Age mean (SD): intervention: 36.6 years (10.3); comparison: 34.6 years (9.7) |

Intervention (n = 94): prilocaine 3% (30 mg/ml) + felypressin 0.03 IU/ml (Citanest) Comparison (n = 106): lignocaine (xylocaine) 2% + adrenaline 1:80,000 |

Duration of procedure Degree of bleeding (0 = none; 5 = heavy) Pain relief: participant reported (0 = none; 5 = unbearable) |

Other adverse effects, e.g. feeling faint, nausea and shaking, scored in a similar way (0 = none; 5 = a great deal) |

| Johnson 1989 | 70 women undergoing CO2 laser ablation for cervical dysplastic lesion Size of transformation zone recorded as a score out of 2: intervention: 1.4; comparison: 1.2 |

Bilateral paracervical block by injecting 10 ml into the paracervical tissues Intervention (n = 35): lignocaine 2% Comparison (n = 35): normal saline |

Pain relief: VAS on 120 mm scale and objective scoring by nurse and attending operator Blood loss (recorded as a score) |

Anxiety and depression HAD scores (Zigmond 1983) and premenstrual syndrome scores also recorded |

| Johnson 1996 | 44 women undergoing CO2 laser treatment for CIN | Intervention (n = 23): 10 ml paracervical lignocaine 2% Comparison (n = 21): 2 ml lignocaine 2% directly into the TZ |

Pain relief: VAS (expressed as percentage) and objective scoring by nurse and laser operator |

‐ |

| Kizer 2014 | 52 women undergoing loop excision of the cervix for treatment in colposcopy clinic setting Age mean: intervention: 32.3 years; comparison 32.4 years |

Intervention (n = 28): buffered solution of lignocaine 1% + 1:100,000 adrenaline Comparison (n = 24): non‐buffered solution of lignocaine 1% + 1:100,000 adrenaline |

Pain relief: pain scores reported as mean, SD, median and range using 100 mm VAS during the injection, during procedure and cramping pain after procedure |

Adverse effects not reported in paper but mentioned in results section of clinical trials website No complications observed in either group |

| Lee 1986 | 50 women undergoing laser vaporisation of cervix for CIN | Intervention (n = 25): ectocervix infiltrated with 2 ml prilocaine 3% + 0.03 IU/ml felypressin (Citanest) Control (n = 25): no analgesia or anaesthesia |

Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale (VRS none, mild, moderate or severe) Blood loss: none, slight, moderate, troublesome |

Adverse effects, e.g. sweating, nausea, dizziness and cramps, also reported but not included in analysis as they were minor adverse effects |

| Lipscomb 1995 | 50 women scheduled for the loop electrosurgical excision for treatment of CIN Age mean (SD): intervention: 29.5 (10.5); comparison: 28.4 (8.9) Parity mean (SD): intervention: 2.1 (2.1); comparison: 2.3 (1.6) Loop passes: mean (SD): intervention: 1.2 (0.4); comparison: 1.3 (0.6) Positive margins: mean (SD): intervention: 2/25; comparison: 3/25 |

Intervention (n = 25): cervical application of benzocaine 20% gel Comparison (n = 25): placebo gel After 1 minute of gel application, 4 ml of lignocaine 1% + adrenaline 1:100,000 was injected in cervix |

Pain relief: VAS on 10 cm scale |

‐ |

| Mikhail 1988 | 50 women undergoing laser vaporisation of the cervix for CIN Age mean (SD): intervention: 27.4 (3.9); comparison: 26.7 (4.6) Parity mean (SD): intervention 0.9 (1.24); comparison: 1 (1) |

Intervention (n = 25): cervix was sprayed with 3 to 4 ml of a cocaine 10% solution Comparison (n = 25): cervix sprayed with a similar quantity of preservative alone |

Duration of procedure Blood loss (minimal, moderate, severe) Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale and VRS (none, mild, moderate or severe) |

‐ |

| Rogstad 1992 | 60 women undergoing cold coagulation for cervical abnormalities | Intervention (n = 29): 2 ml lignocaine 2% Comparison (n = 31): normal saline |

Pain relief: VAS on 0 to 10 scale and VRS |

Other outcomes, e.g. pain of injection and 3 to 6 weeks' follow‐up questionnaire of pain and bleeding were excluded from the analysis |

| Sammarco 1993 | 45 women undergoing cryocoagulation with liquid nitrogen using cryo‐2000 by double‐freeze technique for CIN | Intervention (n = 19): 2 to 3 ml of lignocaine 1% + adrenaline 1:100,000 dilution Comparison (n = 26): no treatment Both groups received single dose of ketoprofen 75 mg, within 1 hour of the procedure; 2 women received naproxen sodium 550 mg |

Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale Mean VAS score recorded by nurses was not included in analysis owing to high risk of bias |

‐ |

| Sarkar 1993 | 70 women undergoing laser treatment for CIN Age mean (SD): intervention: 27.8 years (6.3); comparison: 28 years (5.4) |

Intervention (n = 35): EMLA cream (lignocaine 2.5% + prilocaine 2.5%) Comparison (n = 35): placebo cream |

Pain relief: assessed by McGill's pain questionnaire (Melzack 1975) and VAS Blood loss (none, mild, moderate, troublesome) |

Minor adverse experiences during treatment, e.g. feeling hot, sweating, dizziness, fainting and sickness, not included in analysis |

| Vanichtantikul 2013 | 101 women

undergoing loop excision treatment for CIN Age median: intervention: 47 years (range 28 to 69 years); comparison: 48 years (range 28 to 85 years) Parity median: 2 (range 0 to 5) in both groups |

Intervention (n = 50): 40 mg of lignocaine 10% spray Comparison (n = 51): 1.8 ml of lignocaine 2% in 1:100,000 adrenaline injected submucosally |

Pain relief: 10 cm VAS after speculum insertion, during local injection or spray application, during loop excision and 30 minutes after procedure. Pain scores reported as median and range for all categories Pain scores further stratified using 2 cm cut‐off for the size of loop and these data reported as mean and SD only for loop size ≥ 2 cm |

No complications observed in any participants |

| Winters 2009 | 60 women undergoing LLETZ for CIN | Intervention (n = 30): prilocaine 3% + felypressin injected deep into the cervical stroma around TZ Comparison (n = 30): prilocaine 3% + felypressin injected superficial followed by deep into the cervical stroma around TZ Same amount used for both groups |

Pain relief: VAS on 100 mm scale |

Pain experienced during local anaesthetic injection also evaluated |

CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HAD: Hospital Anxiety and Depression; HPV: human papillomavirus; LLETZ: loop excision of the transformation zone; n: number of participants; SD: standard deviation; TENS: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VAS: visual analogue scale; VRS: verbal rating score; TZ: transformation zone.

Design

All trials were conducted as single centre trials in a colposcopy clinic setting. Various pain relief interventions were reported in the 19 included trials. Two trials investigated cervical injection (intracervical block (Johnson 1989) and paracervical block (Rogstad 1992)) with anaesthetic agent (lignocaine 2%) compared with saline (Johnson 1989; Rogstad 1992). Three trials used preparations made up of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (Duncan 2005; Lee 1986; Sammarco 1993). One of these three trials used cervical injection with lignocaine 1% mixed with 1:100,000 dilution of adrenaline given submucosally and compared it with no treatment (Sammarco 1993), while the two other trials reported cervical injection with a different anaesthetic agent (prilocaine 30 mg/ml) mixed with vasoconstrictor (felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) compared with no treatment or placebo (Duncan 2005; Lee 1986). One trial investigated lignocaine 1% plus vasoconstrictor (1:30 of ornipressin in lignocaine 1% solution) compared to lignocaine 1% alone to evaluate the effects on the blood loss during the procedure (Diakomanolis 1997). One trial evaluated pain relief during the loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) procedure with buffered local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor compared to non‐buffered local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor injected locally into the cervix (Kizer 2014). A buffered solution of local anaesthetic was prepared immediately before use by mixing 9 ml of lignocaine 1% plus adrenaline 1:100,000 with 1 ml of a 1 mEq/ml (8.4%) solution of sodium bicarbonate buffer while the non‐buffered solution contained 10 ml of lignocaine with adrenaline.

Three trials investigated the method of cervical injection. One trial compared local anaesthetic combined with vasoconstrictor (prilocaine 3% plus felypressin) administered by deep and superficial injection with deep injection alone (Winters 2009), while another trial compared paracervical injection of lignocaine 2% with direct injection (Johnson 1996). One trial investigated two different preparations of anaesthetic agent with vasoconstrictor (prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml compared with lignocaine 2% plus adrenaline 1:80,000) (Howells 2000).

Two trials reported the use of oral analgesia with NSAID (naproxen sodium 550 mg), given 30 minutes to one hour before treatment, compared to placebo or no treatment (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Frega 1994), with one trial using a single dose of naproxen sodium 550 mg (Frega 1994) while the other trial used double the dose (1100 mg) (Al‐Kurdi 1985).

One trial used a gas mixture (isoflurane 0.3% and desflurane 1%) as inhalation agent, in addition to standard cervical injection of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml, also known as Octapressin) (Cruickshank 2005).

A further five trials used topical application of gel, cream and sprays for their anaesthetic effects during the treatment on cervix (Connell 2000; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993; Vanichtantikul 2013). One trial looked at the effects of benzocaine 20% gel compared to placebo gel (Lipscomb 1995) and the other trial compared EMLA cream, which is a local anaesthetic cream consisting of a mixture of lignocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5% (Sarkar 1993) to a placebo cream. Mikhail 1988 compared 3 to 4 ml of a cocaine 10% spray as a surface anaesthesia to a placebo solution (preservative) for its effects on pain relief. Out of the two trials using 10% lignocaine hydrochloride spray on the cervix (Connell 2000; Vanichtantikul 2013), one trial compared the effectiveness of 10% lignocaine spray with injection of 2% lignocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline (Vanichtantikul 2013). In the trial of Connell 2000, women were randomised to receive either lignocaine 10% spray or saline spray in addition to standard cervical infiltration using prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml. One trial investigated TENS, which is a non‐invasive method (Crompton 1992).

Participant characteristics

The age of the women in the included trials ranged from 17 to 85 years; the mean age across the trials ranged from 27 to 35 years. However, Vanichtantikul 2013 reported a median age of 47 years (range 28 to 69 years) in the control group and 48 years (28 to 85 years) in the intervention (lignocaine spray) group. Most of the studies included both pre‐ and postmenopausal women, although two trials excluded perimenopausal or postmenopausal women, or both (Crompton 1992; Johnson 1989). Other common exclusion criteria were: various allergies, pregnancy and previous treatment to the cervix. Concomitant use of highly protein‐bound drug was an exclusion criterion in one trial with oral analgesia using NSAID (Al‐Kurdi 1985), while another trial using a gas mixture of isoflurane and desflurane excluded women taking monoamine‐oxidase inhibitors or women driving themselves home from the clinic (Cruickshank 2005). The trial of Kizer 2014 excluded women using prescription analgesics within seven days of scheduled procedure. Other reasons for exclusion included pelvic inflammatory disease, cardiac pacemaker (Crompton 1992), bronchial asthma (Al‐Kurdi 1985), cervical and vaginal infection, drug abuse, history of neurological deficit (Vanichtantikul 2013), cardiac conditions, hypertension and epilepsy (Diakomanolis 1997).

Eight trials described parity for intervention and control groups (Crompton 1992; Cruickshank 2005; Duncan 2005; Howells 2000; Johnson 1989; Kizer 2014; Lipscomb 1995; Vanichtantikul 2013). Number of nulliparous women recruited in these trials ranged from 18% to 48%. Two trials reported the number of children, which ranged from no children up to five (Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988). Three trials reported marital status (Duncan 2005; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993). Two trials provided the usage of contraception (Howells 2000; Johnson 1989). Sixty‐five per cent of women in the intervention group and 72% in the control group used contraception in the trial of Howells 2000. The use of oral contraceptive pills in Johnson 1989 was 47% in the intervention group compared to 53% in the control group.

Cruickshank 2005 used deprivation scores, while median anxiety Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) score (Zigmond 1983) and median depression HAD score (Zigmond 1983) was used to compare the characteristics of intervention and control groups in the Crompton 1992 and Johnson 1989 trials. The Johnson 1989 trial also used anxiety VAS (Zigmond 1983) and premenstrual syndrome scores (no reference provided). Lee 1986 also used the Anxiety score (Spielberger 1970). Only one trial compared the groups for smoking status (Howells 2000).

Three trials reported smear grades as well as final histology with CIN grades (Howells 2000; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009). Lipscomb 1995 and Winters 2009 reported positive margins of excised cervical specimen after treatment. Crompton 1992 reported the size of the cervical pre‐invasive lesion in participants' characteristics, while Howells 2000, Kizer 2014, and Vanichtantikul 2013 reported the size of the loop excised. Vanichtantikul 2013 also reported the volume of the cone excised. Howells 2000 and Kizer 2014 provided number of passes of loop diathermy. Lipscomb 1995 reported mean number of loop passes per person in trial and control group.

The trial of Kizer 2014 reported the volume of anaesthetic agent used in both groups.

In nine of the 19 trials, women underwent laser ablation of the cervix (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Crompton 1992; Diakomanolis 1997; Frega 1994; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Lee 1986; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993), seven trials used LLETZ (Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Howells 2000; Kizer 2014; Lipscomb 1995; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009), one trial used cryotherapy (Sammarco 1993), and two trials used cold coagulation with Semm Coagulator to treat the cervix (Duncan 2005; Rogstad 1992).

Outcomes

The diverse nature of the interventions in the trials precluded direct comparison apart from two trials comparing oral analgesia versus control, it was possible to combine the pain relief outcome reported on VAS (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Frega 1994).

Pain relief reported on visual analogue scale

Fifteen trials reported the degree of pain relief during the procedure as VAS (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Frega 1994; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Kizer 2014; Lee 1986; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Rogstad 1992; Sammarco 1993; Sarkar 1993; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009). All 19 trials used VAS to assess pain immediately after the procedure. In addition, one trial reported VAS for scoring pain after insertion of speculum, after spray or injection of local anaesthetic solution and 30 minutes after the procedure (Vanichtantikul 2013). The pain scores were further stratified according to the size of the excised loop. Kizer 2014 reported VAS for pain due to injection of local anaesthetic solution and cramping pain after procedure in addition to VAS pain scores immediately after the procedure. Seven trials used a 100‐mm or 10‐cm linear analogue scale, where 0 was no pain at all and 100 (or 10 in the 10‐cm scale) was worst pain imaginable (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Cruickshank 2005; Kizer 2014; Lipscomb 1995; Sarkar 1993; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009). One trial reported pain relief on 120‐mm linear VAS, which was converted to percentages (Johnson 1989). Connell 2000, Johnson 1996, and Vanichtantikul 2013 reported pain relief as VAS; however, the values were median and interquartile range (IQR), rather than mean and SD. Sammarco 1993 and Vanichtantikul 2013 reported VAS on an 11‐point scale (0 to 10 or 10‐cm scale) where 0 was no pain and 10 was severe pain.

Pain relief reported on verbal rating scores

Five trials reported pain relief on verbal rating score (VRS) categorised as none, mild, moderate or severe (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Diakomanolis 1997; Duncan 2005; Lee 1986; Mikhail 1988).

Pain relief reported on other categorical scales

In addition to VAS, Johnson 1989 and Johnson 1996 reported pain relief as an objective score, given by the attending nurse and laser operator on a categorical scale of 0 to 2. The attending colposcopist of another trial scored pain on a categorical scale (0 = none to 4 = severe) as well as by women undergoing treatment (0 = none to 5 = unbearable) (Howells 2000). The Sarkar 1993 trial measured pain scores for pain relief after treatment and not just during treatment. However, the time scale for carrying out the pain score was not specified. The trial of Al‐Kurdi 1985 asked women whether additional analgesics were required within the first 24 hours. Cruickshank 2005 asked women whether additional pain relief was required after treatment. It would appear that this was asked at six months' follow‐up, which carries a risk of recall bias. Owing to this risk, we did not include these data in the analysis.

Blood loss during treatment

Seven trials reported blood loss as none, mild, moderate and troublesome (Crompton 1992; Cruickshank 2005; Diakomanolis 1997; Howells 2000; Lee 1986; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993). The Diakomanolis 1997 trial explicitly specified the method of measuring blood loss, while other trials reported blood loss subjectively as scored by the operator on a categorical scale (0 = none to 5 = heavy/troublesome) (Crompton 1992; Cruickshank 2005; Howells 2000; Lee 1986; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993). One trial reported estimated blood loss as volume range with categories of 0 ml, 1 to 5 ml, 6 to 10 ml and more than 10 ml (Kizer 2014).

Speed of procedure (or duration of treatment)

Four trials reported speed of procedure (Diakomanolis 1997; Howells 2000; Lee 1986; Sarkar 1993).

Anxiety

Preoperative anxiety is one of the most significant risk factors for experiencing pain during cervical colposcopy treatment (Johnson 1994). Four trials measured anxiety levels preoperatively in both arms. Three trials measured anxiety using HAD scores (Crompton 1992; Cruickshank 2005; Johnson 1989), while a fourth trial (Lee 1986) used a different scale (Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; Spielberger 1970).

Excluded studies

We excluded three references after obtaining the full text, for the following reasons.

The trial of Sarkar 1990 was not an RCT and it was not controlled for placebo effects. This trial reported use of EMLA cream (lignocaine‐prilocaine cream) for pain relief during cervical laser treatment.

Sharp 2009 did not compare pain relief interventions. This was an observational study nested within an RCT in which women completed a questionnaire about their experiences at colposcopy, colposcopy and biopsy, and colposcopy and LLETZ treatment.

Bogani 2014 was not an RCT and the intervention was for pain relief for different procedure (colposcopically guided biopsies rather than excisional or ablative procedures).

For further details of all the excluded studies, see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Six trials were at low risk of bias, as they satisfied at least five of the criteria that we used to assess risk of bias (Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Kizer 2014; Mikhail 1988). Nine trials were at moderate risk of bias as they satisfied three or four of the criteria (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Diakomanolis 1997; Duncan 2005; Howells 2000; Lee 1986; Lipscomb 1995; Sarkar 1993; Winters 2009). The trials of Rogstad 1992 and Vanichtantikul 2013 were at high risk of bias as they only satisfied two of the criteria and a further three trials were also at high risk of bias as they only satisfied one criterion (Crompton 1992; Frega 1994; Sammarco 1993) (see Figure 3; Figure 4).

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study.

Allocation

Ten trials reported the method of generation of the sequence of random numbers used to allocate women to treatment arms (Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Kizer 2014; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Rogstad 1992; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009), but three of these trials did not report concealment of this allocation sequence from participants and healthcare professionals involved in the trial (Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Rogstad 1992). Five trials did not report on either the method of sequence generation or concealment of allocation (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Connell 2000; Frega 1994; Lee 1986; Sammarco 1993; Sarkar 1993). In the trials of Duncan 2005and Howells 2000, it was unclear whether the method of assigning women to treatment groups was carried out using an adequate method of sequence generation, but the allocation was adequately concealed. The trial of Crompton 1992 did not report sequence generation details but did state that the allocation was not concealed.

Blinding

Four trials reported blinding of participants, healthcare professionals and outcome assessors (Cruickshank 2005; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Kizer 2014), whereas this information was not reported in five trials (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Duncan 2005; Frega 1994; Lee 1986; Rogstad 1992). Five trials confirmed blinding of participants and healthcare professionals, but it was unclear whether the outcome assessor was blinded (Connell 2000; Diakomanolis 1997; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993). Four trials confirmed that participants and/or healthcare professionals were not blinded but did not report whether the outcome assessor was blinded or not (Crompton 1992; Howells 2000; Sammarco 1993; Winters 2009). In the trial of Vanichtantikul 2013 comparing a spray with local injection, operator blinding was not possible.

Incomplete outcome data

At least 80% of the women who were enrolled were assessed at endpoint in all 19 trials.

Selective reporting

It was not certain whether three trials reported all the outcomes that they assessed (Crompton 1992; Lipscomb 1995; Sammarco 1993), but in 10 trials it appeared that additional pertinent outcomes should have been reported and their omission left a gap in the evidence (Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Diakomanolis 1997; Duncan 2005; Frega 1994; Howells 2000; Johnson 1989; Johnson 1996; Rogstad 1992; Vanichtantikul 2013; Winters 2009). The remaining five trials seemed to report all relevant outcomes related to the subject matter.

Other potential sources of bias

No other form of bias appeared likely in 10 trials (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Connell 2000; Cruickshank 2005; Duncan 2005; Howells 2000; Johnson 1989; Lee 1986; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Winters 2009). Additional forms of bias may have been possible in the trials of Sammarco 1993 and Sarkar 1993 in the way some analyses were undertaken, but it was unclear whether this was the case in the remaining five trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Local anaesthetic infiltration (lignocaine 2%) compared with saline injection for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment.

| Local anaesthetic infiltration (lignocaine 2%) compared with saline injection for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women undergoing outpatient colposcopy treatment Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: local anaesthetic infiltration (lignocaine 2%) Comparison: saline injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect MD (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Saline injection | Local anaesthetic infiltration with lignocaine 2% | |||||

| Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0 to 100) | The mean VAS score ranged across control groups was 30 to 53 | The mean VAS score in the intervention groups was 27 to 29 | 13.74 lower (34.32 lower to 6.83 higher) | 130 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Lower VAS score represents less pain |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment were not described in one of the included studies.

2 Adverse events not reported.

Summary of findings 2. Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor compared with no analgesia for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment.

| Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor compared with no analgesia for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women undergoing outpatient colposcopy treatment Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: local anaesthetic + vasoconstrictor Comparison: no analgesia | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect MD (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No analgesia | Local anaesthetic + vasoconstrictor | |||||

| Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0 to 100) | The mean VAS score ranged across control groups was 42.7 to 43 | The mean VAS score in the intervention groups was 11.6 to 26 |

23.73 lower (9.93 lower to 37.53 lower) |

95 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Lower VAS score represents less pain |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment were not described in one of the included studies. Participants and personnel were not blinded in the second study.

2 Adverse events not reported.

Summary of findings 3. Oral analgesia compared with placebo for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment.

| Oral analgesia compared with placebo for pain relief during outpatient colposcopy treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women undergoing outpatient colposcopy treatment Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: oral analgesia Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect MD (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Oral analgesia | |||||

| Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0 to 100) | The mean VAS score ranged across control groups was 21 to 41 | The mean VAS score in the intervention groups was 19 to 36 |

3.51 lower (10.03 lower to 3.01 higher) |

129 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Lower VAS score represents less pain |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment were not described in one of the included studies.

2 Adverse events not reported.

3 Some inconsistencies regarding presentation of the data in one study.

Local anaesthetic versus placebo

Two trials compared local anaesthetic (lignocaine 2%) alone versus placebo (saline injection) (Johnson 1989; Rogstad 1992). Johnson 1989 used lignocaine 2% injection for paracervical block while the trial of Rogstad 1992 used lignocaine 2% for direct injection in the cervix.

Pain scores during procedure (VAS)

Rogstad 1992 found that women who received local anaesthetic had less pain during treatment than women who received placebo (MD ‐24.00; 95% CI ‐35.44 to ‐12.56; 60 women), whereas Johnson 1989 found no difference between the groups (MD ‐3.00; 95% CI ‐16.03 to 10.03; 70 women) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Local anaesthetic (lignocaine 2% injection) versus control (saline injection), Outcome 1: Pain scores during procedure (VAS)

Moderate to severe pain during procedure

Rogstad 1992 found that women who received local anaesthetic reported less moderate or severe pain during treatment than women who received placebo (RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.71; 60 women) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Local anaesthetic (lignocaine 2% injection) versus control (saline injection), Outcome 2: Moderate to severe pain

Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control

Three trials compared local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control, but variations in both the interventions or control groups, or both, meant that the trials could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis (Duncan 2005; Lee 1986; Sammarco 1993).

Pain scores during procedure

Meta‐analysis of two trials, assessing 95 women, found that women who received local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (prilocaine 3% with felypressin 0.03 IU/ml (Lee 1986) and lignocaine 1% with adrenaline 1:100,000 dilution (Sammarco 1993)) had less pain during treatment than women who received no treatment (MD ‐23.73; 95% CI ‐37.53 to ‐9.93) (Analysis 2.1). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is because of heterogeneity rather than chance may represent substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 63%). In Sammarco 1993, women in both intervention arm and control arm received the oral analgesic ketoprofen 75 mg single dose within one hour of receiving treatment.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control, Outcome 1: Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0‐100)

Moderate or severe pain during procedure

Two trials reporting pain relief with local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control using VRS showed contrasting results (Duncan 2005; Lee 1986). Duncan 2005 found that women who received local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor (5 ml vials of prilocaine 3% (30 mg/ml) with felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) reported less moderate or severe pain during treatment than women who received placebo. Lee 1986 found no difference in the same outcome between women who received vasoconstrictor with local anaesthetic (2 ml of prilocaine 3% with felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) and those who received no treatment (RR 0.12; 95% CI 0.04 to 0.37 and RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.27 (Analysis 2.2) for local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor versus placebo or no treatment, respectively). Whether the difference could be attributable to varying dosage of anaesthetic agents (5 ml in Duncan 2005 trial versus 2 ml in Lee 1986 trial) is worth considering. We identified no other trials on optimal dosage to address this issue. Also of note, the method of cervical treatment differed in these two trials. Women in Lee 1986 received cervical treatment with laser vaporisation while in Duncan 2005 the women received treatment with Semm coagulator (high‐temperature electro‐cautery).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control, Outcome 2: Moderate or severe pain

Blood loss (subjective) during procedure

Lee 1986 found no difference in the risk of troublesome bleeding between women who received local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (2 ml of prilocaine 3% plus 0.03 IU/ml of felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) and women who received no treatment (RR 0.40; 95% CI 0.09 to 1.87) (Analysis 2.3). However, the blood loss was not measured and was a subjective impression by the operator.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus control, Outcome 3: Troublesome bleeding

Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus local anaesthetic injection alone

Diakomanolis 1997 compared local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (30 ml of ornipressin 1:30 plus lignocaine 1% solution) with local anaesthetic alone (30 ml of lignocaine 1% solution).

Moderate or severe pain during procedure

Diakomanolis 1997 found no difference in the risk of moderate or severe pain between women who received local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor and women who received local anaesthetic alone (RR 1.20; 95% CI 0.57 to 2.52) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus local anaesthetic injection alone, Outcome 1: Moderate or severe pain

Blood loss (measured) during procedure

Diakomanolis 1997 found that women who received vasoconstrictor with local anaesthetic had less measured blood loss during treatment than women who received local anaesthetic alone (MD ‐8.75 ml; 95% CI ‐10.43 to ‐7.07) (Analysis 3.2). In this trial, the amount of solution used for cervical injection of 30 ml was higher than what is generally used. Unlike the subjective evaluation of blood loss in other trials by the operator, trial of Diakomanolis 1997 reported the actual measured volume of blood loss.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus local anaesthetic injection alone, Outcome 2: Blood loss (volume)

Speed of procedure (duration of treatment)

Diakomanolis 1997 found that duration of treatment was less in women who received vasoconstrictor with local anaesthetic than women who received local anaesthetic alone (MD ‐7.72; 95% CI ‐8.49 to ‐6.95) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus local anaesthetic injection alone, Outcome 3: Duration of treatment

Local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (prilocaine (local anaesthetic) with felypressin (vasoconstrictor)) versus lignocaine (local anaesthetic) with adrenaline (vasoconstrictor))

Howells 2000 compared two types of local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor. More specifically, it reported a comparison of prilocaine 3% with felypressin 0.03 IU/ml versus lignocaine 2% with adrenaline 1:80,000.

Pain scores during procedure (using 6‐point categorical scale)

Howells 2000 found no difference in pain scores when measured using a 6‐point categorical scale between women who received prilocaine plus felypressin and women who received lignocaine plus adrenaline (MD ‐0.05; 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.16) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Prilocaine plus felypressin versus lignocaine plus adrenaline, Outcome 1: Pain (using 6 category scale)

Blood loss during procedure

Howells 2000 found that women who received prilocaine plus felypressin had more mean blood loss during treatment than women who received lignocaine plus adrenaline (MD 0.41; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.69) (Analysis 4.2). However, the observed difference is unlikely to be clinically significant and the assessment of blood loss was by subjective 0‐ to 5‐point scoring and not the actual measured loss.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Prilocaine plus felypressin versus lignocaine plus adrenaline, Outcome 2: Blood loss (0‐5 scale)

Deep plus superficial versus deep cervical injection

One trial compared deep plus superficial injection with deep injection alone (Winters 2009).

Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0 to 100)

Winters 2009 found no difference in pain scores when measured using a VAS between women who received deep and superficial injection and women who received deep cervical injection (MD ‐4.90; 95% CI ‐11.51 to 1.71) (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Deep plus superficial versus deep cervical injection, Outcome 1: Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0‐100)

Oral analgesic versus placebo or no treatment

Two trials reported a comparison of naproxen sodium 550 mg tablets given at least 30 minutes before treatment (oral analgesic) versus placebo (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Frega 1994). The trial of Frega 1994 also included a third arm, which had randomised women to no drug.

Pain scores during procedure

Meta‐analysis of the two trials assessing 129 women, found no difference in pain scores when measured using a VAS between women who received oral analgesic and women who received placebo (MD ‐3.51; 95% CI ‐10.03 to 3.01 (Analysis 6.1) (Al‐Kurdi 1985; Frega 1994). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that was because of heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance) was not important (I2 = 0%). The trial of Frega 1994 also found no difference in pain scores between oral analgesic versus no treatment (MD ‐4.00; 95% CI ‐13.69 to 5.69 (Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Oral analgesic versus control, Outcome 1: Pain scores (VAS: 0‐100)

Moderate to severe pain during procedure

Al‐Kurdi 1985 found no difference in the moderate or severe pain experienced during treatment between women who received oral analgesic and women who received placebo (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.13) (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Oral analgesic versus control, Outcome 2: Moderate to severe pain

Pain relief required in first 24 hours

The trial of Al‐Kurdi 1985 found that women who received oral analgesic for pain relief during colposcopy were less likely to use additional pain relief within the first 24 hours following treatment than women who received placebo (RR 0.12; 95% CI 0.03 to 0.47) (Analysis 6.3).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Oral analgesic versus control, Outcome 3: Pain relief required in first 24 hours

Inhalation analgesia versus placebo or no treatment

Cruickshank 2005 reported a comparison of a gas mixture (isoflurane and desflurane) as inhalation analgesia versus placebo (air) (in addition to standard cervical injection with prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml).

Pain scores during procedure

Cruickshank 2005 found that women who received gas mixture for pain relief (in addition to standard cervical injection with prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) had less pain during treatment than women who received placebo (MD ‐7.20; 95% CI ‐12.45 to ‐1.95) (Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Inhalation analgesia versus placebo, Outcome 1: Pain scores (VAS: 0‐100)

Haemorrhage during procedure

Cruickshank 2005 found no difference in the risk of heavy vaginal bleeding between women who received gas mixture and those who received placebo (RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.64) (Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Inhalation analgesia versus placebo, Outcome 2: Heavy vaginal bleeding

Anxiety (HAD score) during procedure

Cruickshank 2005 found no difference in anxiety scores between women who received gas mixture and women who received placebo (MD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.80 to 0.82) (Analysis 7.3).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Inhalation analgesia versus placebo, Outcome 3: Anxiety ‐ HAD score

Topical application (benzocaine gel, EMLA cream, cocaine spray and lignocaine spray) versus control

Five trials reported comparisons of anaesthetic topical application versus control agent, but variations in the interventions meant that the trials were could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis (Connell 2000; Lipscomb 1995; Mikhail 1988; Sarkar 1993; Vanichtantikul 2013).

Topical (gel/cream) versus placebo

Two trials reported topical gel or cream versus placebo (Lipscomb 1995; Sarkar 1993).

Pain scores during procedure

Lipscomb 1995 found no difference in pain scores when measured using a VAS between women who received anaesthetic topical gel (20% benzocaine) and women who received placebo (MD ‐9.00; 95% CI ‐68.59 to 50.59) (Analysis 8.1). Women in both intervention and placebo arm received pre‐procedure oral analgesia in addition to injecting 4 ml of lignocaine 1% (mixed with adrenaline 1:100,000) in four quadrants of the cervix.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Topical application versus placebo, Outcome 1: Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0‐100)

Speed of procedure (duration of treatment)

Sarkar 1993 found no difference in the duration of treatment between women who received anaesthetic topical cream (EMLA cream ‐ mixture of lignocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) and women who received placebo (MD 0.10; 95% CI ‐1.38 to 1.58) (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8: Topical application versus placebo, Outcome 2: Duration of treatment

Cocaine spray versus placebo

Mikhail 1988 reported a comparison of cocaine spray versus placebo.

Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0 to 100)

Mikhail 1988 found that women who received cocaine spray for pain relief had less pain during treatment than women who received placebo (MD ‐28.00; 95% CI ‐37.86 to ‐18.14) (Analysis 9.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9: Cocaine spray versus placebo, Outcome 1: Pain scores during procedure (VAS: 0‐100)

Moderate to severe pain during procedure

Mikhail 1988 found that women who received cocaine spray experienced less moderate or severe pain during treatment than women who received placebo (RR 0.57; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.89) (Analysis 9.2).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9: Cocaine spray versus placebo, Outcome 2: Moderate to severe pain

Blood loss during procedure (troublesome bleeding)

Mikhail 1988 found that women who received cocaine spray had less risk of troublesome bleeding following treatment than women who received placebo. No women in the cocaine spray arm and 11 out of 25 women in the placebo arm had troublesome bleeding. We did not calculate the RR; the default zero‐cell correction within Review Manager 5 would bias the result of the meta‐analysis towards no difference between cocaine spray and placebo (Analysis 9.3).

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9: Cocaine spray versus placebo, Outcome 3: Troublesome bleeding

Lignocaine spray versus cervical injection with lignocaine with adrenaline

Vanichtantikul 2013 compared 40 mg 10% lignocaine spray alone with 1.8 ml of 2% lignocaine plus 1:100,000 adrenaline.

Pain scores during procedure

Vanichtantikul 2013 reported pain scores using 10 cm VAS scoring system between women who received 40 mg 10% lignocaine spray and women who received 1.8 ml of 2% lignocaine with 1:100,000 adrenaline. Pain during the procedure was reported as median rather than mean pain scores. As such, the median pain scores were not included in the analysis but were summarised separately. However, pain during the procedure was reported as means following stratification of data by loop size (less than 2 cm and 2 cm or greater), and these data were included in the analysis.

TENS, local anaesthetic alone and TENS plus local anaesthetic injection

Crompton 1992 compared three treatments; TENS, TENS plus cervical infiltration with local anaesthetic with a vasoconstrictor (2 ml of lignocaine 2% plus Octapressin (prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml)) injection and local anaesthetic injection alone. As results of pain relief were reported as median with IQR, they were not included in analysis but were summarised separately.

Troublesome blood loss during procedure

Crompton 1992 found no difference in the risk of troublesome vaginal bleeding between women who received TENS, TENS plus local anaesthetic and local anaesthetic alone (TENS versus TENS plus local anaesthetic: RR 2.56; 95% CI 0.28 to 23.29; TENS versus local anaesthetic alone: RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.19 to 3.20; TENS plus local anaesthetic versus local anaesthetic alone: RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.04 to 2.55) (Analysis 10.1; Analysis 11.1; Analysis 12.1).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10: TENS versus TENS plus local anaesthetic injection, Outcome 1: Troublesome blood loss

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11: TENS versus local anaesthetic injection, Outcome 1: Troublesome blood loss

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12: TENS plus local versus local anaesthetic injection, Outcome 1: Troublesome blood loss

Buffered solution of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor versus non‐buffered solution of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor

Kizer 2014 compared submucosal cervical injection of a buffered solution of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor agent (mixture of 9 ml of lignocaine with adrenaline 1:100,000 mixed with 1 ml of a 1 mEq/ml (8.4%) solution of sodium bicarbonate buffer) with the non‐buffered solution of lignocaine plus adrenaline.

Pain scores during procedure

Kizer 2014 found no difference in the pain scores on VAS scale between women who received buffered local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor and women who received non‐buffered solution of local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor agent (MD ‐8.00; 95% CI ‐17.57 to 1.57) (Analysis 13.1).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13: Buffered versus non‐buffered local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor, Outcome 1: Pain scores (VAS: 0‐100)

Studies or analyses, or both, included within the review but not in the forest plots

Pain scores (VAS and objective pain scores)

Connell 2000; Crompton 1992; and Johnson 1996 reported pain on VAS scales using median and IQR. Johnson 1996 also reported objective pain scores by attending nurse and colposcopist.

Lignocaine spray versus placebo

Connell 2000 compared 0.5 ml of lignocaine 10% spray in addition to standard cervical infiltration with prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml versus placebo. The trial reported the results of pain relief using a VAS scale as median and IQR. The results showed that application of lignocaine spray had no effect on pain scores (P value = 0.38). The medians with IQR of the VAS scale for lignocaine spray versus placebo were 40.0 (IQR 21.25 to 63.25) for lignocaine spray and 36.0 (IQR 17.5 to 49.5) for placebo.

Lignocaine spray versus local anaesthetic plus vasoconstrictor

Vanichtantikul 2013 compared four puffs (10 mg each) of 10% lignocaine spray versus standard 1.8 ml of 2% lignocaine with adrenaline 1:100,000 cervical injection. The trial reported the results of pain relief during the intervention (spray versus injection) during the procedure and 30 minutes after the procedure using a 10 cm VAS score as median and range.

Pain scores during the procedure

The median pain scores with IQR using 10 cm VAS during procedure were 3.0 (IQR 0.0 to 9.5) for lignocaine spray and 4.0 (IQR 0.0 to 8.2) for lignocaine plus adrenaline injection (P value = 0.11).

Pain scores 30 minutes after the procedure

The median pain scores with IQR after 30 minutes of completion of the procedure were 2.6 (IQR 0.0 to 7.8) for lignocaine spray and 1.9 (IQR 0.0 to 8.5) for lignocaine plus adrenaline injection (P value = 0.84).

Pain scores during application of spray versus injection

The median with IQR for the VAS pain score was 0.0 (IQR 25.7 to 3.0) for lignocaine spray and 1.9 (IQR 23.5 to 7.6) for lignocaine plus adrenaline injection (P value < 0.01).

TENS, local anaesthetic injection and TENS plus local anaesthetic injection

Crompton 1992 compared three treatments; TENS, TENS plus cervical infiltration with local anaesthetic with a vasoconstrictor (2 ml of lignocaine 2% plus Octapressin (prilocaine 30 mg/ml plus felypressin 0.03 IU/ml) injection and local anaesthetic injection alone (2 ml of lignocaine 2%).

The results of pain relief using VAS were reported as median pain scores and IQR (24 (IQR 10 to 42) for TENS; 17 (IQR 7 to 30) for local anaesthetic alone; 18 (IQR 8 to 31) for TENS plus local anaesthetic). The median pain score for the group assigned TENS only was higher than the median score for the group given direct infiltration of local anaesthetic alone (U = ‐1.57; P value = 0.12).

Paracervical versus intracervical injection in the transformation zone of cervix with lignocaine