Abstract

Background

Vulval cancer is usually treated by wide local excision with removal of groin lymph nodes (inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy) from one or both sides, depending on the tumour location. However, this procedure is associated with significant morbidity. As lymph node metastasis occurs in about 30% of women with early vulval cancer, accurate prediction of lymph node metastases could reduce the extent of surgery in many women, thereby reducing morbidity. Sentinel node assessment is a diagnostic technique that uses traceable agents to identify the spread of cancer cells to the lymph nodes draining affected tissue. Once the sentinel nodes are identified, they are removed and submitted to histological examination. This technique has been found to be useful in diagnosing the nodal involvement of other types of tumours. Sentinel node assessment in vulval cancer has been evaluated with various tracing agents. It is unclear which tracing agent or combination of agents is most accurate.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic test accuracy of various techniques using traceable agents for sentinel lymph node assessment to diagnose groin lymph node metastasis in women with FIGO stage IB or higher vulval cancer and to investigate sources of heterogeneity.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (1946 to February 2013), EMBASE (1974 to March 2013) and the relevant Cochrane trial registers.

Selection criteria

Studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of traceable agents for sentinel node assessment (involving the identification of a sentinel node plus histological examination) compared with histological examination of removed groin lymph nodes following complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL) in women with vulval cancer, provided there were sufficient data for the construction of two‐by‐two tables.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (TAL, AP) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, classified studies for inclusion/exclusion and extracted data. We assessed the methodological quality of studies using the QUADAS‐2 tool. We used univariate meta‐analytical methods to estimate pooled sensitivity estimates.

Main results

We included 34 studies evaluating 1614 women and approximately 2396 groins. The overall methodological quality of included studies was moderate. The studies included in this review used the following traceable techniques to identify sentinel nodes in their participants: blue dye only (three studies), technetium only (eight studies), blue dye plus technetium combined (combined tests; 13 studies) and various inconsistent combinations of these three techniques (mixed tests; 10 studies). For studies of mixed tests, we obtained separate test data where possible.

Most studies used haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains for the histological examination. Additionally an immunohistochemical (IHC) stain with and without ultrastaging was employed by 14 and eight studies, respectively. One study used reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis (CA9 RT‐PCR), whilst three studies did not describe the histological methods used.

The pooled sensitivity estimate for studies using blue dye only was 0.94 (68 women; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69 to 0.99), for mixed tests was 0.91 (679 women; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.98), for technetium only was 0.93 (149 women; 95% CI 0.89 to 0.96) and for combined tests was 0.95 (390 women; 95% CI 0.89 to 0.97). Negative predictive values (NPVs) for all index tests were > 95%. Most studies also reported sentinel node detection rates (the ability of the test to identify a sentinel node) of the index test. The mean detection rate for blue dye alone was 82%, compared with 95%, 96% and 98% for mixed tests, technetium only and combined tests, respectively. We estimated the clinical consequences of the various tests for 100 women undergoing the sentinel node procedure, assuming the prevalence of groin metastases to be 30%. For the combined or technetium only tests, one and two women with groin metastases might be 'missed', respectively (95% CI 1 to 3); and for mixed tests, three women with groin metastases might be 'missed' (95% CI 1 to 9). The wide CIs associated with the pooled sensitivity estimates for blue dye and mixed tests increased the potential for these tests to 'miss' women with groin metastases.

Authors' conclusions

There is little difference in diagnostic test accuracy between the technetium and combined tests. The combined test may reduce the number of women with 'missed' groin node metastases compared with technetium only. Blue dye alone may be associated with more 'missed' cases compared with tests using technetium. Sentinel node assessment with technetium‐based tests will reduce the need for IFL by 70% in women with early vulval cancer. It is not yet clear how the survival of women with negative sentinel nodes compares to those undergoing standard surgery (IFL). A randomised controlled trial of sentinel node dissection and IFL has methodological and ethical issues, therefore more observational data on the survival of women with early vulval cancer are needed.

Plain language summary

Can tests used to identify the main groin lymph node/s in women with vulval cancer accurately predict whether the cancer has spread to the groin/s?

The issue

Women with vulval cancer that has spread to the groin lymph nodes need additional treatment. The standard treatment usually involves surgical removal of as many groin nodes as possible (known as complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL)). However, only about 30% of women with vulval cancer in whom lymph nodes are not obviously enlarged will have groin involvement; therefore, in about 70% of these women additional surgery is not necessary. As groin surgery often causes later swelling of the legs and other unpleasant side effects, it would be preferable not to undergo the surgery if it is not required; therefore, accurate screening tests to determine who should have surgery are needed.

Sentinel node assessment involves identifying the main lymph node/s draining the tumour. After the main (sentinel) nodes are identified, they are removed and examined under a microscope to check for cancer cells. Additional surgery depends on the findings of the examination: if cancer cells are found in the nodes, additional surgery is necessary; if the nodes are cancer‐free, additional surgery can be avoided.

Why is this review important?

Several studies have been done using dyes or traceable agents to identify sentinel nodes. From these studies, it is not clear whether all of these agents are sufficiently accurate to predict which women have cancerous spread to the groin. This review summarises the evidence and produces overall estimates of the relative accuracies of the available tests.

How was the review conducted?

We included all studies that tested the accuracy of tracer agent/s against the standard method of identifying cancer in the groin nodes (removing all groin nodes (IFL) and examining them under a microscope). Women in these studies had vulval cancer of Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB or higher without obvious signs of cancer in the groin (enlarged or palpable nodes). We only included studies of at least 10 women, and noted any concerns about the quality of studies.

What are the findings?

We included 34 studies (1614 women) that evaluated three techniques: blue dye only, technetium (a radioactive substance) only, or blue dye and technetium combined. Ten studies used all three techniques during the course of the study (one technique per participant). There are two attributes to a test: the ability to identify or detect the sentinel node, and the ability to identify the cancer in the sentinel node. We found that all tests can identify cancer in the groin nodes with good accuracy (more than 90% of nodes with cancer will be accurately identified with any of the tests), although the combined test was the most accurate (95%). The ability of the tests to detect sentinel nodes varied, with the blue dye test only detecting sentinel nodes in 82% of women, compared with 98% for the combined test. If sentinel nodes are not detected, they cannot be examined for cancer cells; therefore, women in whom sentinel nodes are not detected will usually need to undergo IFL.

What does this mean?

The combined and technetium only tests are able to predict accurately which women have cancerous spread to the groin. For a group of 100 women undergoing assessment, the findings mean that approximately one or fewer women having the combined or technetium only tests will undergo an unnecessary IFL, compared with approximately 11 women having the blue dye only test. This is mainly because the blue dye only test is not as good as technetium in identifying sentinel nodes. Fewer women with spread to the groin will be missed with the combined or technetium only tests (1 to 3 out of 30) compared with the blue dye only test (1 to 8 out of 30). It is not clear whether women with negative sentinel nodes (i.e. no spread of cancer to the groin lymph nodes) who do not undergo IFL will live as long as those who undergo IFL. The current best data on survival come from a Dutch study that followed up 259 women with negative sentinel nodes and reported a three‐year survival of 97%.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Summary of findings: Traceable agents for sentinel lymph node assessment in vulval cancer.

|

Review question: how does the diagnostic test accuracy of various techniques using traceable agents for sentinel lymph node assessment in vulval cancer compare? Patients or population: women with FIGO stage IB or higher vulval cancer without palpable/suspicious groin nodes Settings: tertiary level hospitals Role: to diagnose groin lymph node metastases Index tests: blue dye, technetium, combined tests (blue dye and technetium) and mixed tests (blue dye, technetium or combined tests) Reference standard: histological examination following complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy Studies: prospective (30) and retrospective (4) cohort | ||||||||

| Index test | Quantity of evidence | Mean detection rate* | Pooled sensitivity results per woman (95% CI) | Consequences in a cohort of 100 women undergoing SN assessment, assuming the prevalence of groin metastases to be 30% | ||||

|

No SNs detected** (undetected) |

Women with metastatic nodes diagnosed by index test (TP) |

Women with metastatic nodes missed by index test (FN) |

Women requiring IFL*** | Women not requiring IFL | ||||

| 1. Blue dye | 68 women (3 studies) |

82% | 94% (69% to 99%) | 18 | 23 (17 to 25) | 2 (0 to 8) | 41 | 59 |

| 2. Technetium | 149 women (8 studies) |

96% | 93% (89% to 96%) | 4 | 27 (26 to 28) | 2 (1 to 3) | 31 | 69 |

| 3. Combined tests (blue dye + technetium) | 390 women (12 studies) |

98% | 95% (89% to 97%) | 2 | 28 (26 to 29) | 1 (1 to 3) | 30 | 70 |

| 4. Mixed tests | 679 women (7 studies) |

95% | 91% (71% to 98%) | 5 | 26 (20 to 28) | 3 (1 to 9) | 32 | 68 |

Studies which employed 'mixed tests' used a combination of the index tests 1 to 3 and presented the overall results (i.e. did not present results separately for the different tests).

The detection rate is the percentage of patients in which the test located a sentinel node. In patients where no node is detected, the test has no value.

*These mean detection rates are estimates derived from the total number of participants included in the studies for each test (see Table 3).

**Undetected women require complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL).

***Undetected women + correctly diagnosed women (TPs).

TP = true positives; FN = false negatives

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

The target condition being diagnosed is groin lymph node metastases in women with vulval cancer. Vulval cancer is a rare gynaecological cancer with an incidence of 1 to 3 per 100,000 women per year (ONS 2009; Sankaranarayanan 2006; Saraiya 2008). At the time of diagnosis more than half of affected women are aged 70 years or above, and incidence peaks at the age of 75 years and above (ONS 2009; Sankaranarayanan 2006). However, recent epidemiological evidence from The Netherlands suggests that the incidence in younger women is increasing (Schuurman 2013). The majority (75% to 90%) of vulval cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (Saraiya 2008; Stehman 2007), which are staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification (Table 2).

1. FIGO staging of vulval cancer *.

| Stage I | Tumour confined to the vulva |

| 1A | Lesions ≤ 2 cm in size, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤ 1.0 mm**, no nodal metastasis |

| 1B | Lesions > 2 cm in size or with stromal invasion > 1.0 mm*, confined to the vulva or perineum, with negative nodes |

| Stage II | Tumour of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes |

| Stage III | Tumour of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with positive groin lymph nodes |

| IIIA | (i) With 1 lymph node metastasis (≥ 5 mm), or |

| (ii) 1 to 2 lymph node metastasis(es) (< 5 mm) | |

| IIIB | (i) With 2 or more lymph node metastases (≥ 5 mm), or |

| (ii) 3 or more lymph node metastases (< 5 mm) | |

| IIIC | With positive nodes with extracapsular spread |

| Stage IV | Tumour invades other regional (2/3 upper urethra, 2/3 upper vagina), or distant structures |

| IVA | (i) upper urethral and/or vaginal mucosa, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or fixed to pelvic bone, or |

| (ii) fixed or ulcerated groin lymph nodes | |

| IVB | Any distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes |

*The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumour from the epithelial‐stromal junction of the adjacent, most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

Groin lymph node metastasis is associated with reduced survival in women with vulval cancer and depends on the type, size and location of the vulval lesion (Andreasson 1985; Boyce 1985; Curry 1980; Homesley 1991; Parker 1975; Podratz 1983; Smyczek‐Gargya 1997). The risk of groin metastases in women with apparent early‐stage vulval cancer (stage IB/II) is approximately 30% (GROINSS‐V 2008).

Primary vulval lesions are treated by wide local excision (WLE). Lesions smaller than 2 cm, with a depth of invasion less than 1 mm (FIGO stage IA), do not require removal of lymph nodes (inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy; IFL) from the groin due to the extremely low risk (less than 1%) of metastasis (Hacker 1993). However, in all other cases (FIGO stage IB and higher) removal of all groin lymph nodes (IFL) has been the traditional gold standard of treatment. Vulval tumours away from midline (lateralised) require removal of groin lymph nodes from the same side, whilst midline tumours require removal of lymph nodes from both sides (Hacker 1993; Iversen 1981). Most women with positive groin lymph nodes will require further treatment with radiation after surgery, with its risk of additional morbidity. This treatment approach is highly effective, with a low groin tumour recurrence rate of 1% to 10% (Burger 1995; Hacker 1981; Homesley 1991; Katz 2003). Effective treatment has resulted in a halving of vulval cancer mortality over the last three decades (ONS 2009). However, this treatment approach is associated with significant morbidity related to the wound and lymph drainage in up to 70% of cases (Fotiou 1996; Gaarenstroom 2003; Rouzier 2003; Stehman 1992; Van der Zee 2008). Short‐term morbidity includes wound infection, wound disruption, groin lymph collection (lymphocyst) and longer hospital stay. Long‐term morbidity includes chronic leg swelling (lymphoedema), chronic and recurrent skin infection (erysipelas) and reduced mobility.

Index test(s)

The lymphatic fluid from the vulval skin is drained by lymphatic channels to the groin lymph nodes. The first lymph node to receive these lymphatic channels on each side is considered to be the sentinel node. Cancer cells from a vulval tumour spread via lymph fluid through lymphatic channels usually to the sentinel node, before spreading to other nodes. A diagnostic test can therefore be employed to detect, excise and examine the sentinel node(s) histologically for cancer cells. This is usually achieved by injecting a traceable agent subcutaneously around the vulval tumour (usually at four quadrants). This agent spreads via the lymphatic channels to the lymph node, which can be traced using an appropriate tracing method. The first lymph node in each groin region to concentrate the traceable agent is considered the sentinel lymph node. There are two attributes to a test: the ability to identify a sentinel node (detection), and the ability to identify the cancer in the sentinel node (diagnosis).

Various traceable agents and their detection techniques can be employed on their own or in combination. For instance, the most commonly used technique involves a combination of radioactive 99m technetium and patent blue dye. Technetium radiocolloid is injected at four quadrants of the vulval tumour a day before, or on the day of, surgery followed by a scan to detect the sentinel node(s) (lymphoscintigraphy), which are marked on the overlying skin. Patent blue dye is injected around the tumour immediately before surgery. A hand‐held gamma camera probe to detect the concentration of the technetium and the visual discolouration of patent blue dye guides the surgeon during the operation to detect the sentinel node.

Once excised, the sentinel node is sent either for an immediate frozen section examination or for routine paraffin histology (which takes a few days to report). If the sentinel node is found to have cancer cells (positive sentinel node), further surgery to remove all remaining groin nodes (at the same time if reported on frozen section, or at a later date if on paraffin section) will be required. If the sentinel node is reported to be free of cancer cells (negative sentinel node), total removal of groin lymph node and its associated morbidity can be avoided. Ultrastaging techniques such as serial micro‐sectioning (at 200 to 250 μm) and immunohistochemistry staining (usually for cytokeratin) are used to detect micro‐metastasis (< 2 mm size) in the sentinel node if initial haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) section is negative (Knopp 2005). This has proven to increase the detection rate of lymph node metastasis (GROINSS‐V 2008), but its significance in the overall prognosis in vulval cancer remains unclear. It is anticipated that use of ultrastaging will have a significant effect on the diagnostic accuracy of sentinel node analysis.

Sentinel node detection and analysis has been pioneered and has become the standard of care in the surgical management of melanoma and breast cancer (Canavese 2010; Krag 2007; Morton 1990; Morton 2006; Rodier 2007; Thompson 2007; Wang 2011). Success rates of sentinel node detection in vulval cancer with the combined use of 99m technetium and patent blue dye approach have been reported to be between 89% and 100% (de Hullu 2000; Tavares 2001). Failure to detect the sentinel node could be due to the agent failing to reach a sentinel node, too low concentration of agent in the lymph node, or the surgeon not being able to identify the sentinel node. In this situation it is advisable to undergo standard groin lymph node dissection (IFL). In those where sentinel node(s) are identified it is important that the false negative rate of groin lymph node metastasis (i.e. negative sentinel lymph node but presence of positive non‐sentinel lymph nodes) is extremely low. A high false negative sentinel node rate will lead to poor outcomes due to avoidance of groin lymph node removal and radiation treatment in cases that would have actually benefited from these therapies.

Sentinel node assessment is usually only used in cases where the vulval tumour size is less than 4 cm in maximum diameter with greater than 1 mm depth of invasion, and in cases where groin lymph node metastasis is not suspected. The maximum tumour dimension of 4 cm, although arbitrarily chosen, is based on a relatively lower risk of lymph node metastasis (± 30%; GROINSS‐V 2008) and low failure rate to detect sentinel nodes. False negatives occur more frequently with tumours larger than 4 cm in size (Levenback 2012).

Clinical pathway

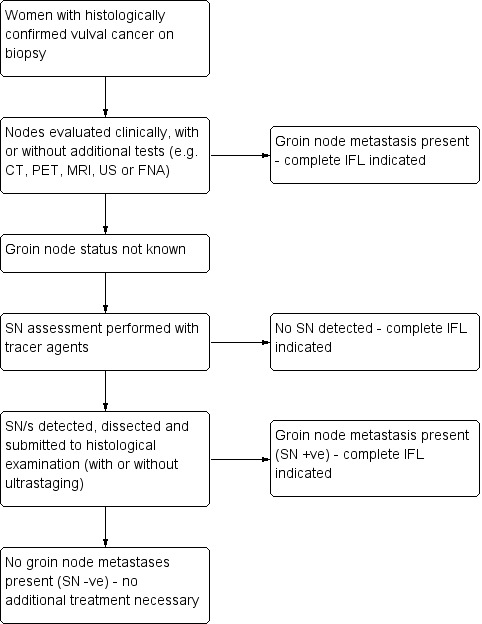

For the clinical pathway of women with early vulval cancer see Figure 1.

1.

Clinical pathway of women with ≥ FIGO stage IB vulval cancer

SN sentinel node; CT computed tomography; PET positron emission tomography; MRI magnetic resonance imaging; US ultrasound; FNA fine needle aspiration; IFL inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy

Role of index test(s)

The role of the index test is to predict accurately groin lymph node metastases so that the extent of surgery can be reduced for women without metastases.

Alternative test(s)

Currently, there are no alternative diagnostic tests that predict groin lymph node metastases in vulval cancer with reasonable test accuracy. Various imaging techniques including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography ‐ computed tomography (PET‐CT) have been used to evaluate groin lymph node status before definitive surgery. Although they have the advantage of being non‐invasive, their ability to confirm (sensitivity) or exclude metastasis (specificity) is limited (Abang Mohammed 2000; Cohn 2002; de Hullu 1999; Hall 2003; Hawnaur 2002; Land 2006; Makela 1993; Moskovic 1999; Sohaib 2002), and therefore they are not routinely used in clinical practice.

Rationale

Surgical excision of tumour and lymphatic staging remains a cornerstone of the management in vulval cancer. For very early‐stage disease (FIGO IA), WLE without lymphatic staging is an accepted method of treatment due to the low risk (less than 1%) of lymph node metastasis (Hacker 1993). For FIGO stage IB disease or above, a WLE of vulval tumour along with the removal of groin lymph nodes from one or both sides (depending on the tumour location) is the traditional treatment of choice (Hacker 1993; Iversen 1981). This treatment, however, is associated with significant morbidity related to wound and lymph drainage in up to 70% of cases (Gaarenstroom 2003; Rouzier 2003; Stehman 1992; Van der Zee 2008). The overall rate of lymph node metastasis in vulval cancer is reported to be 25% to 50% (Creasman 1997; Simonsen 1984; Sutton 1991). The node‐negative cases are unlikely to benefit from removal of groin lymph nodes and many will suffer from unnecessary associated surgical morbidity. Most women with positive groin lymph nodes will require further treatment with radiation, with its risk of additional associated morbidity.

The concept of sentinel node detection and analysis has been successfully applied to guide the management of melanoma and breast cancer (Canavese 2010; Krag 2007; Morton 1990; Morton 2006; Rodier 2007; Thompson 2007). The surgical morbidity of axillary lymph node dissection has been reduced without adverse effect on breast cancer outcomes (Canavese 2010; Krag 2007; Rodier 2007; Wang 2011). A similar benefit is possible with sentinel node assessment in vulval cancer as well. The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node in the groin region to which the vulval cancer cells would spread via the lymphatic channels. The histological analysis of the sentinel groin node is considered to be representative of all other remaining non‐sentinel groin lymph nodes draining to the same anatomical side. The use of sentinel node assessment will therefore triage only those women with positive sentinel node for further groin node dissection, avoiding surgical morbidity in the remaining sentinel node‐negative women. If sentinel node detection and analysis has very high sensitivity with an extremely low false negative rate in predicting groin lymph node metastasis, its use in routine clinical practice can be envisaged. This review aims to analyse the diagnostic accuracy of sentinel node assessment in vulval cancer.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic test accuracy of various techniques using traceable agents for sentinel lymph node assessment to diagnose groin lymph node metastasis in women with FIGO stage IB or higher vulval cancer and to investigate sources of heterogeneity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all prospective and retrospective studies that compared and reported diagnostic test accuracy statistics of sentinel node assessment (detection and histological examination) with the reference standard of histological examination of inguinofemoral lymph node dissection (IFL). We included studies that reported the number of sentinel node procedures (each side counted separately; so‐called 'per groin' data) and the number of women who underwent a sentinel node procedure (whereby a bilateral sentinel node procedure was reported as one case; so‐called 'per woman' data), provided that we could construct two‐by‐two tables of these data. We excluded studies reporting fewer than 10 sentinel node procedures, as well as studies for which construction of a two‐by‐two table for either 'per groin' or 'per woman' data was not possible. For studies that included women with clinically suspicious, palpable or metastases‐positive groin nodes, we attempted to exclude these women from the extracted data. Where this was not possible, we excluded studies in which these cases exceeded 10% of the total numbers of women or groins assessed.

Participants

Women diagnosed with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB or higher vulval cancer without clinically suspicious nodes. We considered all ages, histological types of tumour, and all techniques and settings of sentinel node detection, dissection and histological examination in this review.

Index tests

Tracer agents used to identify sentinel nodes for histological assessment.

We expected that trial reports should specify accurately the technique used and include the following:

Description of agent

Technique, amount, location and timing of injection of agent

Method used to trace and detect sentinel node

Definition of what was regarded as a sentinel node

Description of the histological method used to assess the sentinel node

A sentinel node should have been defined as the first lymph node that showed adequate concentration of tracing agent (e.g. greatest radioactive signal in groin basin detected on hand‐held gamma probe in case of radioactive tracer agent, or a node that appeared visually blue intra‐operatively) (de Hullu 1998). The sentinel node should then have been removed and subjected to standard histological examination or by frozen section with at least haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. If the sentinel node was found to be malignant, it was defined as a positive sentinel node. If a sentinel node did not show any malignancy, it was defined as a negative sentinel node. If a sentinel node could not be identified, it was defined as 'failure to detect sentinel node' (and not index test negative). Details of reason for failure to detect sentinel nodes should also have been reported where possible, along with the outcome of lymph node status on reference standard.

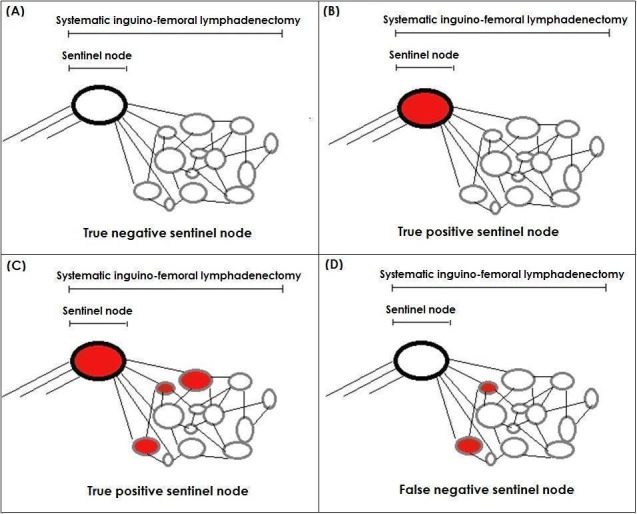

A complete groin lymph node dissection (IFL) would include the sentinel node in the specimen, thus creating a situation where the index test result becomes part of the reference standard (incorporation). Realistically, therefore, false positive tests would not exist in this situation (see Figure 2). In an event where the sentinel node was identified, assessed and deemed histologically positive but the remaining groin nodes were negative, the index test would still be regarded as a true positive. We did not anticipate that false positive tests would be reported in the included studies, but if we encountered them, unless further information was available from the author to create a protocol‐compliant two‐by‐two table, we planned to exclude them from the review.

2.

Possible outcomes of sentinel lymph node assessment followed by total groin lymph node removal (inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy). (A) Negative sentinel and rest of the groin nodes (True negative), (B) Positive sentinel node but negative rest of the groin nodes (True positive), (C) Positive sentinel and groin nodes (True positive) and (D) Negative sentinel but positive groin nodes (False negative)

We anticipated that many studies would report a combination of various sentinel node assessment techniques (mixed tests). When analysing the diagnostic test accuracy of a single technique, we only included these studies in the analyses if a separate two‐by‐two table for the technique in question could be constituted. Similarly, not all women received combined techniques (i.e. blue dye and technetium) in these studies. When analysing the diagnostic test accuracy of the combined technique, these studies were only included in the analyses if all cases received the combined technique in question, or a separate two‐by‐two table for cases who received the combined technique in question could be constituted. Where possible, we attempted to obtain separate diagnostic test accuracy data from investigators of studies in which different index test data had been combined.

Target conditions

Groin (inguinofemoral) lymph node metastases in FIGO stage IB or higher vulval cancer.

Reference standards

Histological examination of systematic groin lymph node dissection (IFL) was the reference standard. The reference standard was to be subjected to the standard histological assessment with at least H&E staining. If any of the removed nodes (including the sentinel node) showed cancer metastasis histologically, the reference standard was considered positive. Studies were to report the reference standard result by each side of groin node removal or by women/cases.

Systematic groin lymph node removal includes removal of inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. Traditionally this includes removal of lymph nodes above and parallel to the inguinal ligament up to the pubic tubercle medially and lymph nodes from the femoral triangle (parallel to femoral vessels and sapheno‐femoral junction including cribriform fascia) up to and including the deep fascia of muscle forming the base of the femoral triangle. Dissection deeper to the deep fascia or into the adductor canal is usually not required. However, there remains some uncertainty regarding the ideal extent and adequacy of surgical dissection (Hudson 2004).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The electronic searches were performed by the Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group Trial Search Co‐ordinator, Anne Eisinga. This included searches of the following electronic databases:

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to February 2013, week four);

EMBASE (OvidSP) (1974 to March 2013, week 10).

The search strategies are outlined in the appendix (Appendix 1). As these searches would have identified any possible reviews on the topic we did not search other databases, e.g. DARE, as stated in the protocol. We did not apply language restrictions to the electronic searches and, where necessary, had non‐English articles of relevant studies translated.

Searching other resources

We reviewed the reference list of all relevant studies retrieved from electronic searches and used the 'related articles' feature of PubMed to identify additional potentially relevant studies. We did not handsearch the conference proceedings of the International Gynaecological Cancer Society (IGCS), the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the Society of Gynaecologic Oncologists (SGO) and the American Society of Clinical Oncologist (ASCO) from 2000 to the present as planned in the protocol, as abstracts for this period from these societies were identified by the electronic searches. Where the electronic searches identified conference abstracts in the absence of a full report, we attempted to contact the investigators for more information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the reference manager software Endnote® to remove duplicates from all titles and abstracts retrieved from the literature search (Endnote 2012). Amit Patel (AP) and Theresa Lawrie (TAL) independently examined all eligible references. We excluded studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained full‐text articles of those that appeared potentially relevant. AP and TAL independently assessed the full‐text articles for their eligibility and in the event of disagreement involved other authors. We documented clearly the reasons for exclusion of potentially relevant studies.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following variables from each included study to a specifically designed Excel® spreadsheet:

Author, year of publication and journal (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Study design and flow of patient pathway

Population

Sample size

Details of diagnosis of vulval cancer (diagnostic biopsy or radical excision)

-

Pathological parameters

Size of tumour

Histological type

Unifocal or multi‐focal

Lympho‐vascular invasion

Previous history of vulval surgery

Details of any suspected groin node involvement prior to sentinel node assessment

Additional tests performed to assess groin lymph node status prior to the sentinel node assessment

Experience of the surgeons

-

Index test

-

Method(s)

Details of tracer agent used, amount, dilution

Method of application

Timing of application in relation to sentinel node excision

Method used to detect sentinel node

Method used for histological assessment of sentinel node

-

Results

Detection rate of sentinel node (total intended versus total detected)

False negative sentinel node test (categorised by negative sentinel node)

Rate of adverse events associated with index test

-

-

Reference standard

Unilateral or bilateral

Is positive sentinel node (but negative remaining groin nodes) regarded as positive reference standard?

Average lymph node yield (quality marker for reference standard)

Extent of surgical dissection of groin lymph nodes

Method used for histological assessment

Rate of adverse effects associated with reference standard

QUADAS‐2 items (see Assessment of methodological quality below)

Data for two‐by‐two table

We piloted the data extraction spreadsheet including QUADAS‐2 items using two included studies. We matched the data between the two authors (TAL and AP) and resolved differences by revisiting the original articles.

Assessment of methodological quality

AP and TAL performed the assessment of methodological quality. In the event of disagreement, other co‐authors were involved. We assessed treatment pathways in detail for each included study. We also assessed the description of index and reference standard tests for each included study to determine if these were described in sufficient detail to enable the reader to reproduce the technique. We assessed study methodological quality using the QUADAS‐2 tool (Whiting 2011) as described in Appendix 3, and reported the results in detail in a tabular and graphical form. We also summarised results in the text.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

To determine diagnostic test accuracy (DTA), we performed separate analyses with 'per groin' and 'per women' data. We created two‐by‐two tables in Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and calculated sensitivity (diagnostic accuracy statistic for proportion of women with the disease who were correctly identified from the test) for each included study. Specificity was always 100% as, when the reference standard was negative, sentinel node was always negative. We presented diagnostic accuracy statistics for each study in a paired forest plot (where specificity was always 100%). As a result, sensitivity statistics were lined up on y‐axis (sensitivity) crossing x‐axis at 0 (1‐specificity) on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space. As there was no variability in specificity, we used the univariate model to pool these sensitivity data by removing the logit specificity and correlation parameters from the standard bivariate model (Reitsma 2005), thus simplifying the model to a univariate random‐effects logistic regression model. The analysis was carried out using the xtmelogit command and macro procedures in Stata IC version 12.0 (Stata 2012).

We estimated mean detection rates for each technique by combining the number of participants detected in each included study (numerator), divided by the total number of participants in which the technique was attempted (denominator), and multiplied by 100. We used these crude rates to illustrate the clinical consequences of the DTA results.

Investigations of heterogeneity

We anticipated that multiple factors could influence DTA statistics for sentinel node detection and analyses in vulval cancer. These factors may lead to heterogeneity in the analyses. In the univariate analysis of sensitivity we did not quantify heterogeneity using the I² statistic or make inference about heterogeneity using the variance parameter for logit sens. Instead of quantifying heterogeneity, we investigated heterogeneity where possible. We explored the effect of heterogeneity by investigating forest plots limited to relevant study level subgroup co‐variables. We attempted to explore the potential effects of the following covariates:

Index test used in sentinel node detection, e.g. blue dye and/or technetium

Techniques used in sentinel node histological assessment, e.g. ultrastaging, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Size of tumour (less than 4 cm)

Experience of surgeon/s

We were unable to explore heterogeneity related to other variables (including histology, site and focality of tumour, previous vulval surgery and the use of imaging techniques prior to enrolment) due to insufficient relevant data.

Sensitivity analyses

During the review process we discovered that several studies had included some women with clinically suspicious or palpable groin nodes. As this was not predicted at the protocol stage, and raised concerns about applicability, we decided to include these studies if the number of women or groins affected was 10% or less of the total sample, or if investigators supplied sufficient information for us to exclude these data from the study results. We noted our concerns regarding the applicability of the samples assessed in these studies and performed sensitivity analysis by excluding these studies to assess their effect on the review results. We also performed sensitivity analyses related to other methodological quality items (QUADAS‐2) including the type of study (retrospective versus prospective).

Assessment of reporting bias

Where possible, we explored patient withdrawals and drop‐outs from individual studies. We included data from studies presented at conferences but not published in full, and attempted to obtain further details of these studies, to minimise publication bias. Where studies had been published more than once, at various stages of enrolment, we checked that the data in the earlier and later reports corresponded and, if not, we attempted to obtain clarification from the investigators.

Results

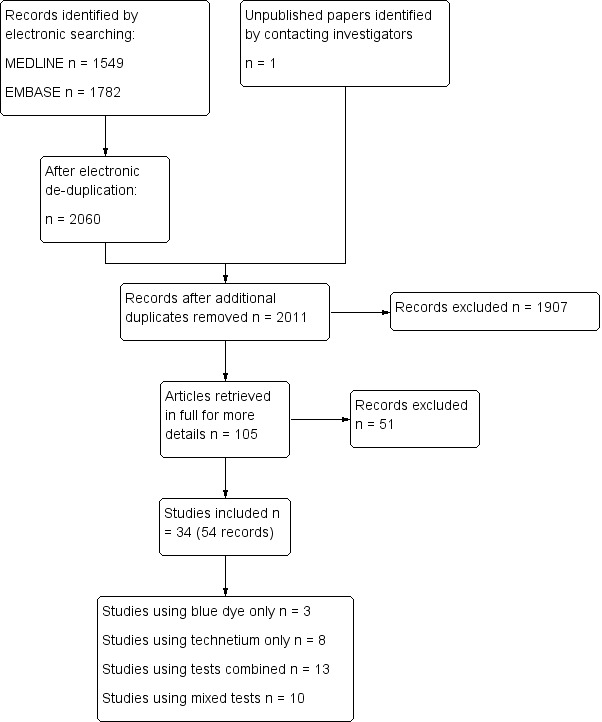

Results of the search

The combined de‐duplicated 2013 MEDLINE and EMBASE searches yielded 2020 records. Two review authors (TAL, AP) independently screened these titles and abstracts, selecting 103 records for classification. After obtaining the full texts, we excluded 51 records (pertaining to 47 studies/reports) mainly for the following reasons:

they were reviews, editorials, case reports or letters to the editor (eight);

we were unable to construct two‐by‐two tables from the available data (12);

the reference standard had not been consistently applied (12);

they were not studies assessing sentinel node test accuracy (11);

more than 10% of participants had clinically suspicious nodes and we were unable to separate these data from the other participants (three); or

the sample size was less than 10 (one).

For further details see Characteristics of excluded studies.

We included 34 studies comprising 54 citations (see Figure 3). For the purposes of this review, we emailed the investigators of 20 studies for further information and/or data. We obtained unpublished information and/or data for six of these studies (Levenback 2012; Morotti 2011; Nyberg 2007; Rob 2007; Sawicki 2010; Trifiro 2010), including an unpublished manuscript (Morotti 2011). The latter study would otherwise have been excluded had we not received these unpublished data, as we were unable to construct two‐by‐two tables from the published conference abstract alone.

3.

Study flow diagram.

The included studies evaluated the following index tests:

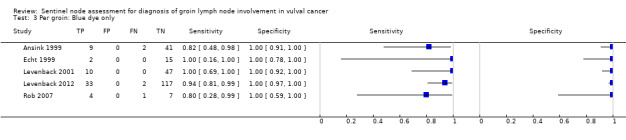

Blue dye only (three studies; Ansink 1999; Echt 1999; Levenback 2001).

Technetium only (eight studies; Boran 2003; DeCesare 1997; Goni 2011; Klar 2011; Merisio 2005; Sideri 2000; Trifiro 2010; Zekan 2012).

Technetium in combination with blue dye (combined tests; 13 studies; Basta 2005; Camara 2009; Crosbie 2010; de Hullu 2000; Johann 2008; Klat 2009; Louis‐Sylvestre 2006; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Moore 2003a; Morotti 2011; Radziszewski 2010; Vidal‐Sicart 2007; Zambo 2002).

A combination of the above tests (mixed tests; 10 studies; Akrivos 2011; Hampl 2008; Hauspy 2007; Levenback 2012; Li 2009; Lindell 2010; Nyberg 2007; Rob 2007; Sawicki 2010; Sliutz 2002).

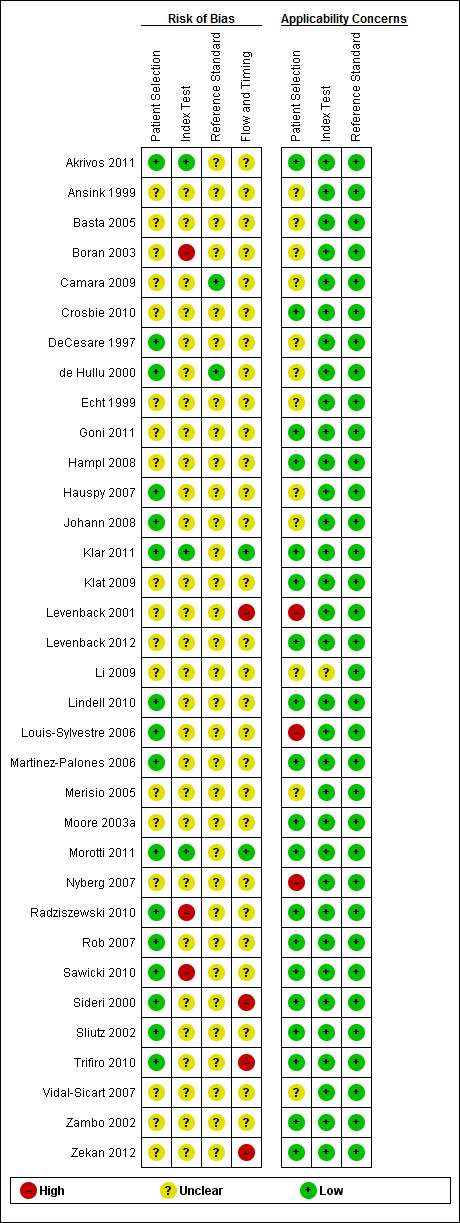

Methodological quality of included studies

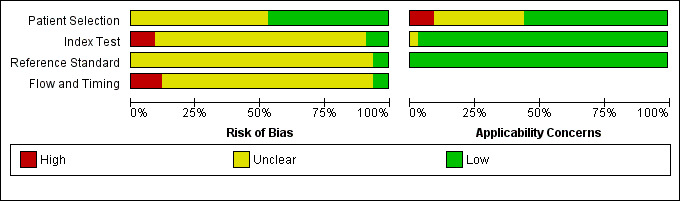

Of the 34 studies, we considered four included studies to be at a high risk of bias for flow and timing, and three studies raised high concerns regarding applicability (Figure 4). However, in general, we considered the quality of included studies to be moderate, with the risk of bias mostly low or unclear (Figure 5).

4.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

5.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

Types of studies

We included 30 prospective and four retrospective studies. We did not include case‐control studies. The sampling method was consecutive in 20 studies, and not clearly described in the other 14 studies. All were conducted in university hospitals and tertiary care settings.

Patient selection

We considered the participants of most studies to be representative of patients in clinical practice. Most participants:

had squamous cell cancer (SCC) of the vulva, except for Trifiro 2010 (melanomas only) and Levenback 2001 (67% SCC, 33% other histology);

were between the ages of 29 and 95 years, with reported mean and median ages ranging from 58 to 75 years (eight studies did not report age);

did not have clinically suspicious nodes.

Four studies included some women with suspicious nodes in their study samples (DeCesare 1997; Levenback 2001; Louis‐Sylvestre 2006, Vidal‐Sicart 2007). We excluded data for these women from our data extraction for Vidal‐Sicart 2007 and Louis‐Sylvestre 2006. For the other two studies, the women with clinically suspicious nodes comprised 10% or less of the participants. We considered these studies to be at an unclear risk of selection bias.

Vulval lesions were midline in 582 women, lateralised in 308 women and the location was not described for 724 women. Tumour size was either not reported (22 studies) or inconsistently reported (12 studies): some studies reported the number of tumours greater than and less than 2 cm, some reported a 4 cm cut‐off and some reported continuous data (mean size). Depth of tumour, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) and grade were rarely reported.

Few described whether any withdrawals or exclusions had occurred during or after the selection process. It was mainly this lack of clarity that increased the proportion of studies in which the risk of bias relating to patient sample selection was 'unclear'.

Index test methods

The index test methods of the included studies were highly applicable to this review, with a low risk of potential bias (Figure 5). They comprised the following techniques: blue dye only (three studies), technetium only (eight studies), a combination of blue dye and technetium (13 studies) or mixed tests (any or all of the previous three techniques used within each study; 10 studies). Most studies reported that index test contents were injected peritumourally, in two to four sites around the tumour, or at 3, 6, 9 and 12 o'clock. Blue dye was injected pre‐operatively, after general anaesthesia for all studies. When technetium was used, the timing was subject to some variation: 13 studies injected technetium on the day before the operation (Akrivos 2011; Crosbie 2010; de Hullu 2000; Goni 2011; Johann 2008; Louis‐Sylvestre 2006; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Morotti 2011; Radziszewski 2010; Sideri 2000; Trifiro 2010; Vidal‐Sicart 2007; Zambo 2002), two studies injected it between 14 and 18 hours pre‐operatively (Basta 2005; Merisio 2005), eight studies injected it two to four hours pre‐operatively (Hampl 2008; Hauspy 2007; Lindell 2010; Klat 2009; Moore 2003a; Rob 2007; Sliutz 2002; Zekan 2012), and three studies injected it intra‐operatively or within two hours of surgery (DeCesare 1997; Klat 2009; Sawicki 2010). In three studies, the timing was unclear (Camara 2009; Levenback 2012; Li 2009), and in one study injections were given either on the day of surgery or on the day before surgery (Nyberg 2007).

Where studies employed mixed tests, administering the various index tests alone (e.g. blue dye or technetium tests alone) and in combination (e.g. technetium and blue dye), separate data were frequently not reported. Where possible, we emailed investigators to request separate data and obtained these data for Rob 2007 and Levenback 2012. In Hauspy 2007, for a subset of women, the choice of one index method (blue dye) was dependent on the success of the other method (Tc‐99m) and therefore separate data would not have been meaningful.

Most studies reported using H&E stains to diagnose groin metastases. Fourteen studies additionally employed ultrastaging and immunohistochemical (IHC) stains to improve detection (Akrivos 2011; Crosbie 2010; de Hullu 2000; Klar 2011; Klat 2009; Levenback 2001; Levenback 2012; Lindell 2010; Hampl 2008; Hauspy 2007; Merisio 2005; Morotti 2011; Rob 2007; Vidal‐Sicart 2007), and eight studies reported using IHC stains, but not ultrastaging (Basta 2005; Boran 2003; Goni 2011; Louis‐Sylvestre 2006; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Radziszewski 2010; Sliutz 2002; Trifiro 2010). One study also employed reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis (CA9 RT‐PCR) to enhance detection (Radziszewski 2010), presenting results with and without the RT‐PCR analysis. Due to the experimental nature of this test, we did not use the RT‐PCR results in our analyses. Histological methods were not described in three studies (Johann 2008; Nyberg 2007; Sawicki 2010).

For blue dye, most studies considered blue lymph nodes and draining lymphatics that turned blue after the index test injection to indicate the presence of a sentinel node. For technetium, sentinel nodes were usually detected intra‐operatively using a hand‐held gamma probe. Nodes were reported to be 'hot' if the measured radioactivity was five or 10 times greater than the background activity (e.g. Hauspy 2007; Levenback 2012; Sawicki 2010) or greater than 5% (e.g. Akrivos 2011) or 10% (e.g. Rob 2007) of the activity of the injection site. Several studies reported continuing dissection if more 'hot' nodes were identified (e.g. defined as activity of > 5% or > 10% of the activity of the injection site or the 'hottest' sentinel node) (e.g. Boran 2003; Klar 2011; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Zekan 2012). Sixteen studies reported the 'mean sentinel node yield' per groin (ranged from 1 to 2.7 sentinel nodes); three studies reported the median sentinel node yield per groin (ranged from 1 to 5 sentinel nodes); and 15 studies did not report either the mean or median sentinel node yield per groin.

For 'surgeon/s experience', either this variable was not reported in the studies, or the element of a 'learning curve' was described; i.e. the surgeon/s gained the necessary experience (10 sentinel node procedures) over the course of the study. Only two studies reported that participating surgeons had performed a minimum of 10 procedures (Klar 2011; Morotti 2011).

Reference standards

All studies reported using histological examination of inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL) as the reference standard. Few studies described the extent of surgical dissection, therefore it was not possible to determine whether heterogeneity existed in this regard. Most studies reported performing bilateral IFL for midline lesions and unilateral IFL for lateralised lesions. Eleven studies defined midline lesions, either as a lesion within 1 cm of the midline (Ansink 1999; de Hullu 2000; Hampl 2008; Hauspy 2007; Klar 2011; Lindell 2010; Louis‐Sylvestre 2006), or within 2 cm of the midline (Levenback 2012; Merisio 2005; Sideri 2000; Zekan 2012), with the other 23 studies not reporting their definitions of 'midline'. Only one study reported blinding the assessors of the reference standard to the results of the index test histology (de Hullu 2000). Thirteen studies (38%) reported that reference standard and index test specimens were sent separately to the laboratory for examination; however, it was unclear to us whether this was supposed to reflect some degree of assessor blinding (see Characteristics of included studies). Therefore, we considered most studies to be at an 'unclear risk' of bias for this item.

Flow and timing

Most studies reported that enrolled women underwent the index test within 24 hours of surgery, sentinel node removal and IFL procedures were performed during the same operation, and specimens were sent to the laboratory immediately thereafter for examination. However, the risk of bias for patient flow in the majority of the studies was 'unclear' overall. This occurred mainly due to the lack of clarity in most studies regarding the signalling question related to 'additional imaging tests'. In only four studies was it described that women had undergone additional imaging tests (ultrasound or CT) to exclude groin lymph node metastases (Hampl 2008; Morotti 2011; Radziszewski 2010; Rob 2007). When this question was excluded from the 'Risk of bias' assessment, the overall risk of bias for patient flow was low.

Other methodological issues

There were some unit of analysis issues, with nine studies reporting test accuracy data 'per women' only (Basta 2005; Camara 2009; Johann 2008; Nyberg 2007; Rob 2007; Sawicki 2010; Sliutz 2002; Trifiro 2010; Zekan 2012). We emailed contact authors of these studies and obtained 'per groin' data for Nyberg 2007; Rob 2007; Sawicki 2010 and Trifiro 2010.

De Cicco 2000 and Sideri 2000 were two reports of the same consecutive case series of women in Italy: women in the former report were recruited between May 1996 and September 1998 (De Cicco 2000); women in the later report were recruited from May 1998 to July 1999 (Sideri 2000). Taking into consideration that the latter paper was an extension of the De Cicco 2000 data set, there remained inconsistencies between the reports with regard to the number of groins, number and types of procedures, and number and types of lesions (lateralised or midline). Contact authors were emailed for clarification, however they were unable to locate these data due to the time lapse since the study. We used the data in the later publication for this review.

Zekan 2012 was also reported twice, as an article and a conference abstract. There are four fewer women reported in the published article of 2012 than the (earlier) conference abstract. We were unable to obtain clarification of this discrepancy and noted our concerns regarding the possibility of withdrawals in the 'Risk of bias' assessment for flow and timing.

In addition to using ultrastaging and IHC stains, Radziszewski 2010 also used a RT‐PCR test. As this was the only study to use this histology method, we did not include the accuracy results of this test in our analysis. By using the PCR test, double the number of true positives were detected; these were mainly micrometastases, for which the clinical significance is unknown.

Findings

1. Detection rates (the ability of a test to identify a sentinel node)

Sentinel node detection rates across included studies varied according to the index test method used and the unit of analysis reported (i.e. 'per groin or 'per woman' data) (Table 3).

2. Sentinel node detection rates of included studies.

| Study ID |

SN detection (per woman) n/N (%) |

SN detection (per groin) n/N (%) |

Undetected +ve groins n/N (%) |

| Blue dye only | 108/131 (82) | 148/228 (65) | |

| 1. Ansink 1999 | 42/51 (82) | 52/93 (56) | 3/41 (7) |

| 2. Akrivos 2011* | NR | 10/14 (71) | 0/4 (0) |

| 3. Echt 1999 | 9/12 (75) | 17/23 (74) | 2/6 (33) |

| 4. Levenback 2001 | 46/52 (88) | 57/76 (75) | 2/19 (10) |

| 5. Rob 2007* | 11/16 (69) | 12/22 (55) | 1/10 (10) |

| Tc‐99m only | 152/159 (96) | 158/189 (84) | |

| 1. Boran 2003 | 10/10 (100) | 17/17 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| 2. Zekan 2012 | 25/25 (100) | NR | NR |

| 3. Merisio 2005 | 20/20 (100) | 21/31 (68) | 1/10 (10) |

| 4. Goni 2011 | 21/24 (88) | NR | NR |

| 5. Sideri 2000 | 44/44 (100) | 61/77 (79) | NR |

| 6. DeCesare 1997 | 10/10 (100) | 20/20 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| 7. Klar 2011 | 12/16 (75) | 25/29 (86) | 0/4 (0) |

| 8. Trifiro 2010 | 10/10 (100) | 14/15 (93) | NR |

| Combined tests | 365/371 (98) | 562/607 (93) | |

| 1. Radziszewski 2010 | NR | 106/107 (99) | NR |

| 2. Basta 2005 | 38/39 (97) | NR | NR |

| 3. Camara 2009 | 15/17 (88) | NR | NR |

| 4. Crosbie 2010 | 31/32 (97) | NR | 0/1 (0) |

| 5. de Hullu 2000 | 59/59 (100) | 95/107 (89) | NR |

| 6. Louis‐Sylvestre 2006** | NR | 39/52 (75) | 3/13 (23) |

| 7. Martinez‐Palones 2006 | 27/28 (96) | 39/40 (98) | 0/1 (0) |

| 8. Rob 2007* | 43/43 (100) | 62/64 (97) | 0/2 (0) |

| 9. Vidal‐Sicart 2007** | 43/43 (100) | 60/64 (94) | NR |

| 10. Moore 2003a | 21/21 (100) | 31/31 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| 11 Morotti 2011 | 55/56 (98) | 92/101 (91) | NR |

| 13 Johann 2008 | NR | NR | NR |

| 14 Klat 2009 | 23/23 (100) | 38/41 (93) | 0/3 (0) |

| 15. Zambo 2002 | 10/10 (100) | NR | NR |

| Mixed tests | 786/827 (95) | 1092/1349 (81) | |

| 1. Levenback 2012 | 418/452 (92) | 593/772 (77) | NR |

| 2. Akrivos 2011 | 34/34 (100) | 52/64 (81) | 0/12 (0) |

| 3. Hauspy 2007 | 39/41 (95) | 58/68 (85) | NR |

| 4. Sawicki 2010 | 24/24 (100) | 34/39 (87) | 1/5 (20) |

| 5. Hampl 2008 | 125/127 (99) | 228/230 (99) | NR |

| 6. Lindell 2010 | 75/77 (97) | 94/130 (72) | 8/36 (22) |

| 7. Nyberg 2007 | 25/25 (100) | NR | NR |

| 8. Li 2009 | 20/21 (95) | NR | NR |

| 9. Sliutz 2002 | 26/26 (100) | 32/46 (70) | NR |

*Data separated from total detection rates for mixed tests.

**Excluding women with suspicious nodes.

NR = not reported

For blue dye only, detection rates ranged from 55% to 75% for 'per groin' data (mean 65%; five studies, 228 groins) and 69% to 88% for 'per woman' data (mean 82%; four studies, 131 women).

For technetium only, detection rates ranged from 68% to 100% for 'per groin' data (mean 84%; six studies, 189 groins) and 75% to 100% for 'per woman' data (mean 96%; eight studies, 159 women).

For blue dye/technetium combined, detection rates ranged from 75% to 100% for 'per groin' data (mean 93%; nine studies, 607 groins) and 88% to 100% for 'per woman' data (mean 98%; 11 studies, 371 women).

For mixed tests, detection rates ranged from 70% to 99% for 'per groin' data (mean 81%; seven studies, 1349 groins) and 92% to 100% for 'per woman' data (mean 95%; nine studies, 827 women).

Less than half of the studies reported the status of undetected nodes and it was not meaningful to analyse these limited data.

2. Test accuracy (the ability of a test to identify cancer)

We included test accuracy data from 1614 women with FIGO stage 1B or higher vulval cancer in our sensitivity meta‐analyses.

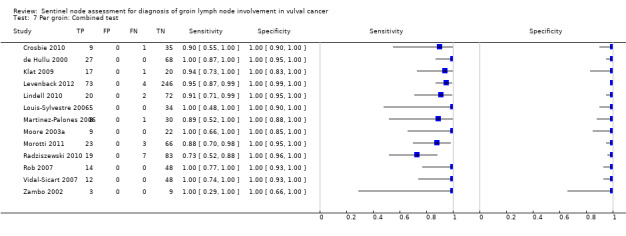

2.1. Test accuracy according to index test method

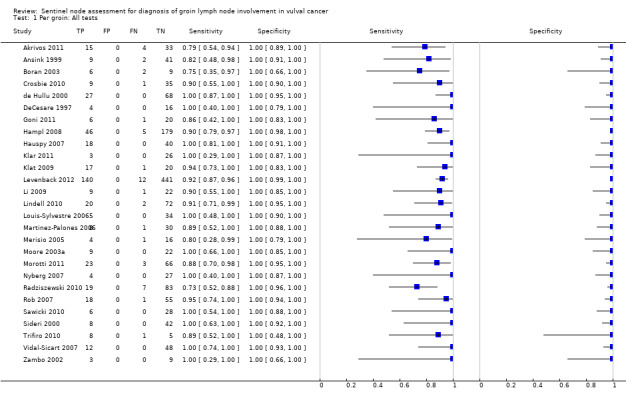

Per groin data

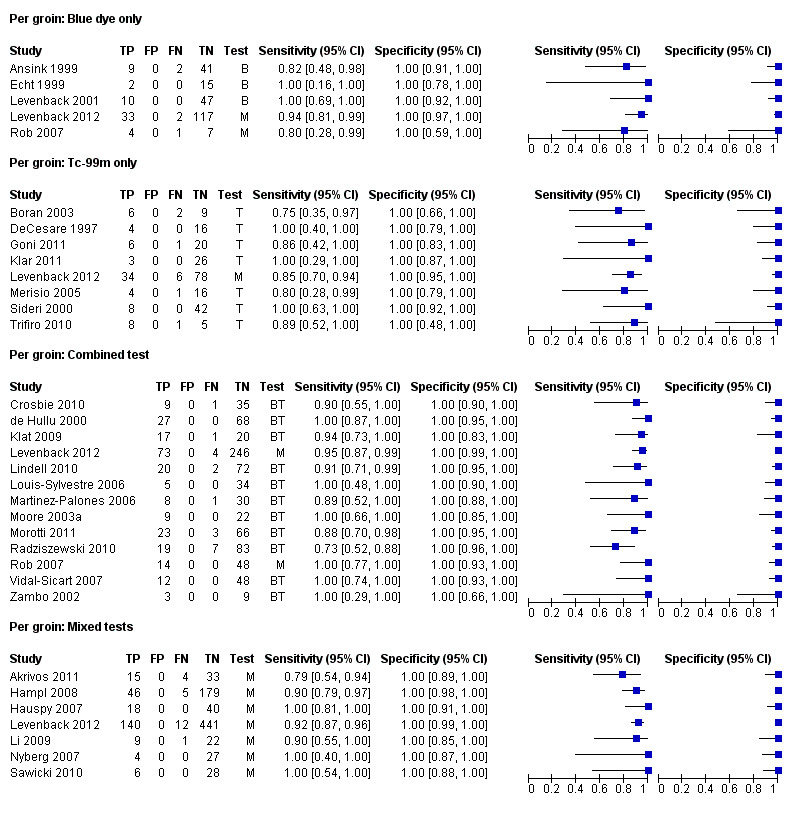

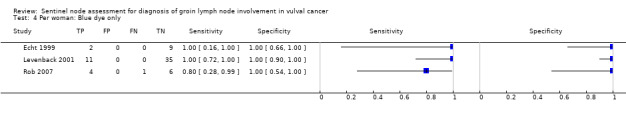

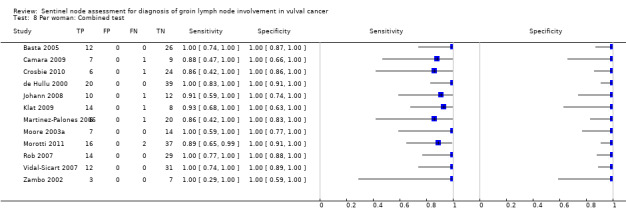

For each index test, the pooled estimates for sensitivity 'per groin' were as follows (Figure 6):

6.

Forest plot of tests: 3 Per groin: Blue dye only, 5 Per groin: Tc‐99m only, 7 Per groin: Combined test, 9 Per groin: Mixed tests.

Blue dye only: 0.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.82 to 0.97 (five studies; 290 groins).

Technetium only: 0.91, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.94 (eight studies; 296 groins).

Combined tests: 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97 (13 studies; 1039 groins).

Mixed tests: 0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93 (seven studies; 1030 groins).

Negative predictive values (NPVs) for the above tests were 98% for blue dye and the combined tests, 97% for mixed tests and 95% for technetium only.

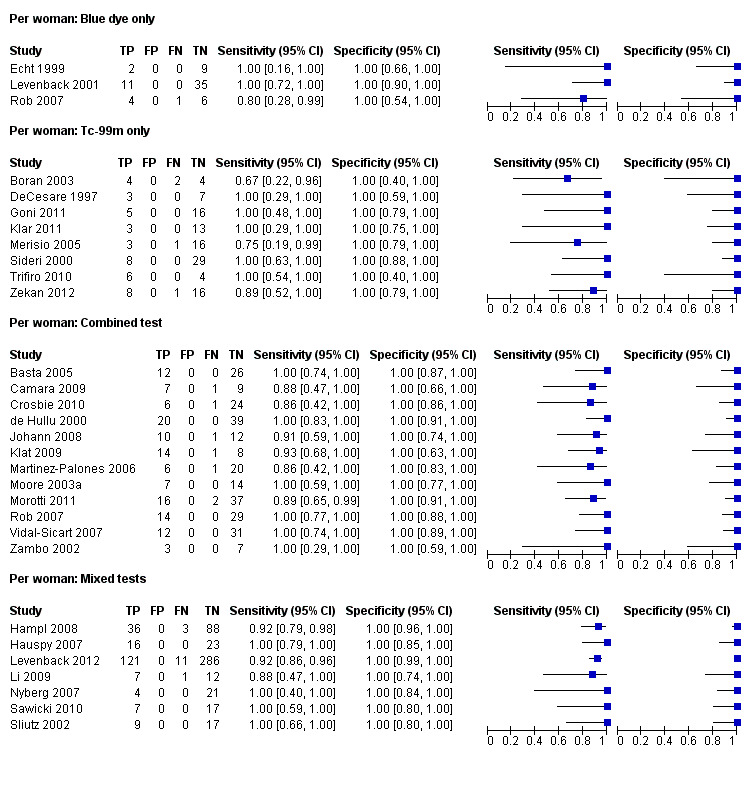

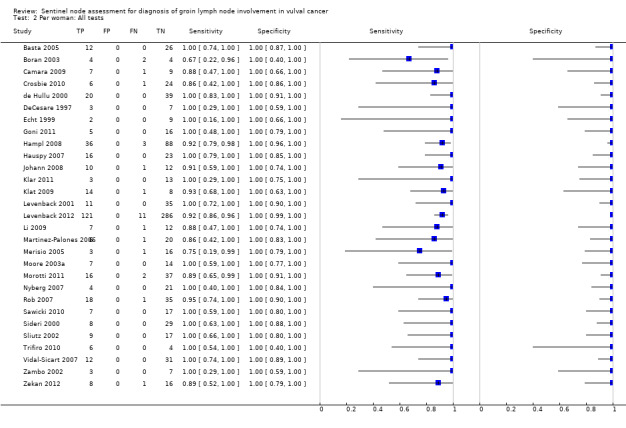

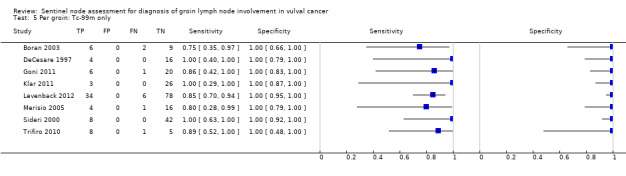

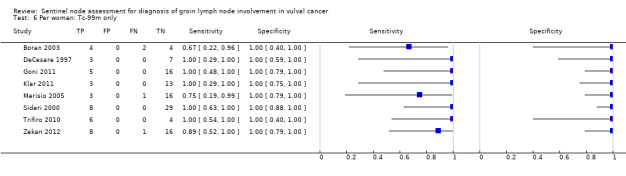

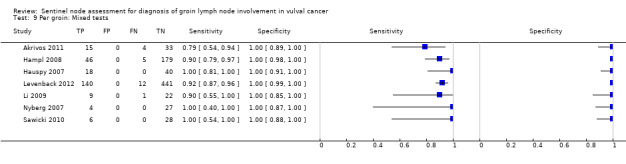

Per woman data

For each index test, the pooled estimates for sensitivity 'per woman' were as follows (Figure 7):

7.

Forest plot of tests: 4 Per woman: Blue dye only, 6 Per woman: Tc‐99m only, 8 Per woman: Combined test, 10 Per woman: Mixed tests.

Blue dye only: 0.94, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.99 (three studies; 68 women).

Technetium only: 0.93, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.96 (eight studies; 149 women).

Combined tests: 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.97 (12 studies; 390 women).

Mixed tests: 0.91, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.98 (seven studies; 679 women).

NPVs of the above tests ranged from 96% to 98%. The rate of groin node metastases in women across all included studies and index tests ((true positives + false negatives)/total number of women evaluated)) was 32% (29 studies; 411/1286 women).

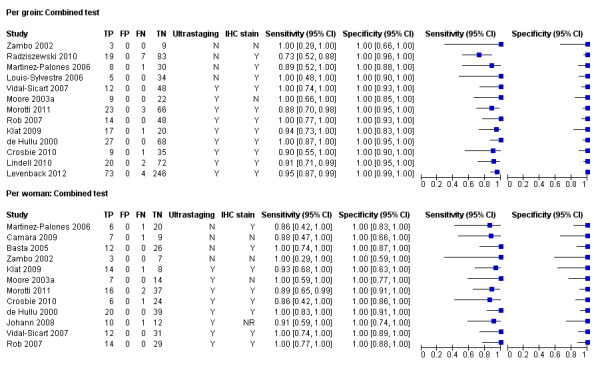

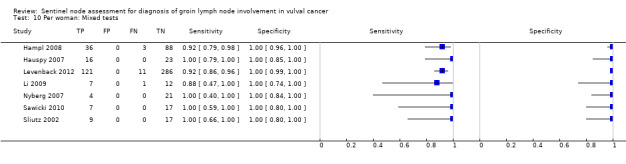

2.2 Test accuracy for combined tests (blue dye and technetium) according to histological methods

Pooled estimates of sensitivity for the combined tests according to histological methods were as follows (Figure 8):

8.

Forest plot of tests: 7 Per groin: Combined test, 8 Per woman: Combined test. Covariate: ultrastaging and/or IHC

Per groin data

Ultrastaging only: 0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.97 (nine studies; 840 groins). Four studies (Louis‐Sylvestre 2006; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Radziszewski 2010; Zambo 2002), which did not report or use ultrastaging, had a pooled sensitivity estimate of 0.81, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.90 (four studies; 199 groins).

Ultrastaging and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC): 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.97 (12 studies; 828 groins). Only one study did not use ultrastaging or IHC (Zambo 2002).

Per woman data

Ultrastaging only: 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.98 (eight studies; 300 women). Four studies (Basta 2005; Camara 2009; Martinez‐Palones 2006; Zambo 2002), which did not report or use ultrastaging, had a pooled sensitivity estimate of 0.93, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.98 (four studies; 92 women).

Ultrastaging and/or IHC: 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 to 0.98 (10 studies; 363 women). Only Camara 2009 and Zambo 2002 did not report or use ultrastaging or IHC; pooled sensitivity was 0.91, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.99 (two studies; 27 women).

2.3. Test accuracy for combined tests according to surgeons' experience

Only one study using the combined tests reported that the surgeons had performed more than 10 procedures prior to the study (Morotti 2011), therefore, meta‐analysis according to this covariate was not possible.

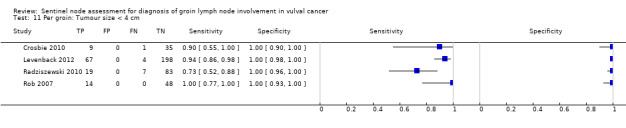

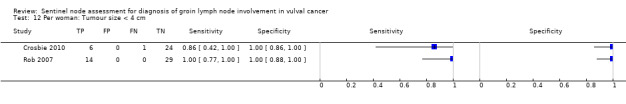

2.4.Test accuracy for combined tests according to tumour size

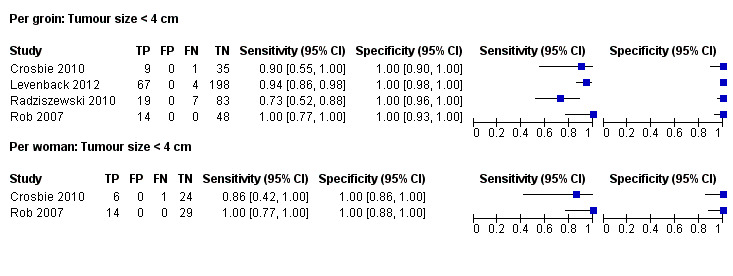

Four studies evaluated test accuracy for tumours of less than 4 cm for 'per groin' data (Crosbie 2010; Levenback 2012; Radziszewski 2010; Rob 2007) (Figure 9), with two of these studies also reporting 'per woman' data (Crosbie 2010; Rob 2007). The pooled estimate for sensitivity for 'per groin' data was 0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.97 (four studies; 485 groins) and for 'per woman' data was 0.99, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99 (two studies; 74 women).

9.

Forest plot of tests: 11 Per groin: Tumour size < 4 cm, 12 Per woman: Tumour size < 4 cm.

2.5. Sensitivity analyses for combined tests

Type of study

Per groin data

Only one study in the combined test meta‐analysis was retrospective (Lindell 2010). When we excluded this study from the meta‐analysis, the pooled estimate for sensitivity was 0.95, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.98 (12 studies; 945 groins).

Per woman data

Only one study in the combined test meta‐analysis was retrospective (Johann 2008). When we excluded this study from the meta‐analysis, the pooled estimate for sensitivity was 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 to 0.98 (11 studies; 367 women).

Other potential sources of heterogeneity

Three studies in the combined test meta‐analysis reported the use of pre‐operative imaging procedures (CT or ultrasound) using 'per groin' data (Morotti 2011; Radziszewski 2010; Rob 2007), and two of these additionally included 'per woman' data (Morotti 2011; Rob 2007).

Per groin data

The pooled sensitivity estimate of these three studies 'per groin' was 0.88, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.96 (three studies; 206 groins), compared with 0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.98 (10 studies; 833 groins) for the studies in which it was not clear whether pre‐operative imaging had been used.

Per woman data

The pooled estimate for sensitivity for 'per woman' data was 0.94, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.98 (two studies; 98 women), compared with 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 0.98 (10 studies; 292 women) for the studies which did not report whether pre‐operative imaging had been used.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The rate of groin node metastases in women across all included studies was approximately 32%. All index tests were associated with pooled sensitivity estimates of greater than 90% for 'per woman' data and 'per groin' data (with exception of mixed tests where the pooled sensitivity estimate was 87% for 'per groin' data) (Table 1). The negative predictive value (NPV) for all index tests 'per woman' was greater than 95%. The combined tests were associated with the best pooled sensitivity estimate, and a narrow confidence interval, however the estimate was not much higher than that of technetium alone. Pooled sensitivity estimates for blue dye alone and mixed tests were associated with wide confidence intervals, which suggests that blue dye may not be sufficiently accurate when used on its own.

Crude mean detection rates across included studies were calculated to be 98%, 96%, 82% and 95% for the combined test, technetium, blue dye and mixed tests, respectively (per woman data). We used these data with the sensitivity data to estimate the clinical consequences of the test results (Table 1). Based on the 'per woman' pooled estimates, and assuming that 30 out of 100 women with FIGO grade IB or higher vulval cancer without suspicious nodes will have groin metastases (30%), one and two women with groin metastases may be 'missed' with the combined tests and technetium only test alone, with a confidence interval (CI) of one to three women for both tests. With blue dye and mixed tests, however, the upper limit of the confidence interval is eight and nine women, respectively. This suggests that utilising blue dye alone or mixed tests may 'miss' as many as nine women out of 30 with groin metastases.

We found little evidence showing the influence of other factors in further reducing the number of missed women. However, pooled sensitivity estimates for the combined test were probably enhanced by the use of ultrastaging (lower CI limits were 0.91 versus 0.88, with and without ultrastaging, respectively (per groin data)). Most studies used these additional techniques for sentinel nodes that were negative on routine H&E staining.

Four studies using the combined test (with ultrastaging and/or IHC staining) evaluated sensitivity data for vulval lesions less than 4 cm in diameter. The pooled estimate for this subgroup of women was slightly lower than the overall sensitivity estimate (0.91, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.97), probably due to insufficient data.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Strengths

To our knowledge, this is the most meticulous review of sentinel node test accuracy in vulval cancer to date. Previous reviews have included studies reporting women with suspicious lymph nodes in their samples (e.g. Molpus 2001; Tavares 2001), studies where the reference standard was not consistent for all women (e.g. Molpus 2001), and data from different reports of the same study (e.g. Sideri 2000 and De Cicco 2000, and the Levenback 2001 series). By applying clearly defined, pre‐specified inclusion criteria we classified potentially eligible studies in a consistent way, thereby attempting to minimise heterogeneity across studies. We also assessed the methodological quality of each study as well as making judgements on its risk of bias. We excluded studies where the sample size was fewer than 10 women, and those in which women with clinically suspicious nodes accounted for 10% or more of the sample, if we were unable to separate these data from the study results. Although several studies had relatively small samples, the review comprises a large number of studies (n = 34) and participants (n = 1614), increasing the power of the analyses (with meta‐analyses ranging from two to 13 included studies). Not all included studies reported their data in the same way or used the same unit of analysis therefore, where possible, we contacted authors for clarification and/or additional data. We pooled and analysed data separately for each index test, and separately for 'per groin' and 'per woman' data. Variations in methodological quality did not appear to have any impact on the overall findings. We therefore consider the resulting evidence to be of a moderate quality.

Analysing both 'per groin' and 'per woman' data is a strength of this review: 'per groin' data may be more precise for assessing test accuracy, however, 'per woman' data are useful for clinical decision‐making. For example, with midline vulval lesions, as long as a metastatic node in one groin is identified, additional treatment (usually bilateral IFL) will be clinically indicated. Therefore, even if the metastatic node in the opposite groin is not identified ('false negative' according to 'per groin' data), the woman will have been identified as needing additional treatment.

Weaknesses

There are inherent weaknesses in DTA studies where the reference standard incorporates the index test result, giving an associated specificity of 100%. Increasing test sensitivity can cause a corresponding drop in specificity, but this would not be detected in these studies due to the absence of false positive results. The clinical consequence of a false positive index test would be a greater extent of surgery (complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL)) for a woman without groin node involvement. However, as complete IFL is also the standard management for a positive test result, the clinical consequences cannot be estimated.

Only one study in this review reported assessor blinding and in most studies the assessment procedure was not clearly described. In unblinded studies, knowledge of the reference standard results might have affected the interpretation of the index test results. This overall lack of blinding would most likely have impacted the results in the direction of overestimating sensitivity, as unblinded assessors may have been tempted to alter their assessment of the index test findings in light of the reference standard results, for example, if an original index test result was equivocal or inconclusive.

It is possible that test accuracy and detection rates are affected in situations where the tumour has already been excised (where agents are injected around the scar), in multi‐focal tumours and in women with a previous history of vulval surgery. We were unable to evaluate test accuracy data for these variables, or midline versus lateralised lesions, as these baseline data were not consistently reported. Similarly, we were unable to evaluate test accuracy data according to the depth of invasion of the primary lesion.

There were insufficient data on surgeons' experience, therefore we were unable to evaluate the impact of this variable on the test results. However, in several studies the early part of the study was used as a learning curve; thus it is likely that, in general, detection and test accuracy may improve over time with increasing specialist expertise. Therefore, a lack of surgeons' experience would be likely to impact the results in the direction of underestimating test sensitivity.

The number of included studies in the meta‐analyses that reported use of pre‐operative imaging was small (three and two for 'per groin' and 'per woman' analyses, respectively) and it is unclear whether this was standard procedure in the other studies; therefore it is difficult to make any inferences with regard to this variable.

We did not anticipate the substantial variation in the timing of administering technetium across included studies. Most studies administered technetium on the day before surgery; however 10 studies administered it within six hours of surgery. These studies reported detection rates ranging from 75% to 100% and, when all technetium studies were considered, the mean detection rate was 97% (282/290 women detected). The technetium study with the lowest detection rate (75%) administered the nanocolloid intra‐operatively after general anaesthesia (Klar 2011). Such timing may be more convenient and more comfortable for patients; however, more evidence is needed on the safety and accuracy of this method.

It would be valuable to know the relative costs of the different tests, including their clinical consequences. However, we did not specify economic outcomes a priori and these data were not reported in any of the included studies.

Applicability of findings to the review question

Sentinel node assessment is a technique designed for use in women with early‐stage vulval cancer (grade IB or higher) without clinically suspicious nodes. Almost all studies included in this review restricted participants to this group of women. The overall rate of groin node metastases across included studies (32%) is robust to a large observational study of early‐stage vulval cancer (GROINSS‐V 2008), in which groin metastases were identified in 33% of women. Therefore, we consider the review findings to be highly applicable.

Index test detection rates have a substantial impact on the clinical pathway of women undergoing sentinel node assessment: for women in whom a sentinel node is not detected, more extensive surgery (complete IFL) is usually indicated (see Figure 1). As IFL is associated with significantly greater morbidity than sentinel node dissection (GROINSS‐V 2008), index tests with lower detection rates will be associated with a greater risk of morbidity. For example, index tests with detection rates of 82% and 98% will result in 18 versus two women per 100 requiring IFL without evidence of groin metastases, respectively (see Table 1). Therefore, index test accuracy cannot be evaluated without considering the index test detection rates. According to the results of this review, the combined test, with a sensitivity of 0.95 and a detection rate of 98% (per woman data), offers the best option for women with early‐stage vulval cancer. The technetium test alone had detection and sensitivity rates that were very similar to the combined test estimates. It is possible that other tracer agents, e.g. fluorescent indocyanine green (ICG), may further enhance sentinel node detection rates; however, we did not find any test accuracy studies of this agent to include in this review.

For women undergoing sentinel node assessment with the combined or technetium tests, an estimated one or two women (2% or less) may be 'missed' (see Table 1). These women would not receive additional treatment and would be likely to experience a shorter survival than those who were identified as having groin metastases and who received additional treatment (IFL). This finding is consistent with GROINSS‐V 2008, in which 3% of sentinel node‐negative women experienced groin recurrences within 16 months of the procedure. The three‐year survival rate for sentinel node‐negative women in GROINSS‐V 2008 was also 97%.

The largest study of sentinel node assessment in vulval cancer to date (Levenback 2012), found that women with vulval lesions greater than 4 cm in diameter were at greater risk of experiencing false negatives on sentinel node assessment. In this study, the NPV of sentinel node assessment for tumours less than 4 cm was 98% compared with 93% for larger tumours. GROINSS‐V 2008 only enrolled women with primary tumours less than 4 cm and revealed a similar NPV to Levenback 2012 for this risk group (97%). The NPV for tests evaluated per women in this review ranged from 96% to 98% overall. Few studies contributed data to the meta‐analysis according to vulval lesion size of less than 4 cm; therefore the review is unable to provide much evidence in this regard. However, based on the data from Levenback 2012, it is prudent to restrict sentinel node assessment to women with vulval lesions less than 4 cm in diameter. Similarly, this review was unable to clarify the role of sentinel node assessment in women with multifocal lesions. However, limited evidence from GROINSS‐V 2008 suggests that women with multifocal lesions may not be suitable candidates for sentinel node assessment.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Sentinel node assessment performed at specialist oncology centres can accurately diagnose groin metastases in women with early vulval cancer and unknown groin node status. In practice, either the combined tests or technetium alone may be employed. Women undergoing sentinel node assessment can be counselled that the risk of the combined or technetium test missing the spread of vulval cancer to the groin lymph nodes is 1% to 3%. This means that one to three women with groin node metastases out of 100 women undergoing the procedure (or out of 30 women with groin lymph node involvement) may be 'missed'. The combined test may miss fewer women than technetium alone. Ultrastaging probably further enhances test accuracy. Using blue dye on its own may increase the number of 'missed' cases to nine per 100 women undergoing the procedure. Both the combined and technetium only tests will reduce the need for complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (IFL) by approximately 70% and, therefore, reduce the risk of surgical morbidity for women with early vulval cancer.

Implications for research.

It is not yet clear how the survival of women with negative sentinel nodes compares to those undergoing standard surgery (IFL). A recent observational study of vulval cancer trends conducted in The Netherlands suggests that the introduction of less radical surgery has not affected survival rates (Schuurman 2013). In order to prove this definitively, one would have to design a study that randomised women with negative sentinel nodes to IFL or no additional treatment, with survival as the endpoint. Given the rarity of vulval cancer, such a study would be a challenge which would require worldwide co‐operation including multiple centres. Furthermore, there are ethical issues in subjecting women with a very small risk of groin metastases to an operation associated with significant morbidity, and which may be unnecessary. It may be possible to design a trial of IFL compared with sentinel node assessment with or without IFL. This would still require huge numbers and therefore may not be feasible, but would be ethically acceptable as the node positivity in both arms would be about 30%, and one of the arms is the current standard treatment.

For this review, it was not possible to determine whether pre‐operative radiology has an important role to play in patient selection and management and future research should address this question. Further DTA studies of existing and new technologies should employ assessor blinding to reduce the risk of detection bias. Further studies to evaluate the optimal timing of technetium administration for sentinel node assessment and patient satisfaction with the procedure, may be of value.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 September 2016 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2013 Review first published: Issue 6, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 April 2015 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 11 February 2015 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Acknowledgements

We thank the following:

Co‐ordinating Editor of the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group (CGCG), Jo Morrison, for her clinical expertise;

CGCG Managing Editors, Gail Quinn and Clare Jess, for their contribution to the editorial process;

Trial Search Co‐ordinator, Anne Eisinga, for designing the search strategy;

Yemisi Takwoingi, for statistical advise and supplying Stata code for the univariate sensitivity analyses ‐ her input was invaluable to the timely delivery of this review;

the librarians at the Royal United Hospital in Bath for sourcing the essential reference material; and

Sambor Sawicki (Sawicki 2010), Lukas Rob (Rob 2007), Matteo Morotti (Morotti 2011), Giuseppe Trifiro (Trifiro 2010), Reita Nyberg (Nyberg 2007), Charles Levenback and Shamshad Ali (Levenback 2012) and Mario Sideri (Sideri 2000), who provided us with additional information and/or data.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group.

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices