Abstract

Background

The standard management of primary ovarian cancer is optimal cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum‐based chemotherapy. Most women with primary ovarian cancer achieve remission on this combination therapy. For women achieving clinical remission after completion of initial treatment, most (60%) with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer will ultimately develop recurrent disease. However, the standard treatment of women with recurrent ovarian cancer remains poorly defined. Surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer has been suggested to be associated with increased overall survival.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of optimal secondary cytoreductive surgery for women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. To assess the impact of various residual tumour sizes, over a range between 0 cm and 2 cm, on overall survival.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) up to December 2012. We also searched registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field. For databases other than MEDLINE, the search strategy has been adapted accordingly.

Selection criteria

Retrospective data on residual disease, or data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective/retrospective observational studies that included a multivariate analysis of 50 or more adult women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer, who underwent secondary cytoreductive surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy. We only included studies that defined optimal cytoreduction as surgery leading to residual tumours with a maximum diameter of any threshold up to 2 cm.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (KG, TA) independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias. Where possible the data were synthesised in a meta‐analysis.

Main results

There were no RCTs; however, we found nine non‐randomised studies that reported on 1194 women with comparison of residual disease after secondary cytoreduction using a multivariate analysis that met our inclusion criteria. These retrospective and prospective studies assessed survival after secondary cytoreductive surgery in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Meta‐ and single‐study analyses show the prognostic importance of complete cytoreduction to microscopic disease, since overall survival was significantly prolonged in these groups of women (most studies showed a large statistically significant greater risk of death in all residual disease groups compared to microscopic disease).

Recurrence‐free survival was not reported in any of the studies. All of the studies included at least 50 women and used statistical adjustment for important prognostic factors. One study compared sub‐optimal (> 1 cm) versus optimal (< 1 cm) cytoreduction and demonstrated benefit to achieving cytoreduction to less than 1 cm, if microscopic disease could not be achieved (hazard ratio (HR) 3.51, 95% CI 1.84 to 6.70). Similarly, one study found that women whose tumour had been cytoreduced to less than 0.5 cm had less risk of death compared to those with residual disease greater than 0.5 cm after surgery (HR not reported; P value < 0.001).

There is high risk of bias due to the non‐randomised nature of these studies, where, despite statistical adjustment for important prognostic factors, selection is based on retrospective achievability of cytoreduction, not an intention to treat, and so a degree of bias is inevitable.

Adverse events, quality of life and cost‐effectiveness were not reported in any of the studies.

Authors' conclusions

In women with platinum‐sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer, ability to achieve surgery with complete cytoreduction (no visible residual disease) is associated with significant improvement in overall survival. However, in the absence of RCT evidence, it is not clear whether this is solely due to surgical effect or due to tumour biology. Indirect evidence would support surgery to achieve complete cytoreduction in selected women. The risks of major surgery need to be carefully balanced against potential benefits on a case‐by‐case basis.

Plain language summary

Surgery to remove tumour so that it is not visible with the naked eye prolongs survival in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer is a disease in which malignant cells form in the tissue covering the ovary. It accounts for about 90% of ovarian cancers; the remaining 10% arise from germ cells or the sex cords and stroma of the ovary. Women with epithelial ovarian cancer that has returned after primary treatment (recurrent disease) may need secondary surgery to remove all or part of the cancer. When ovarian cancer recurs after more than six months it is considered suitable for further treatment with platinum chemotherapy (platinum sensitive).

The results of this review suggest that surgery may be associated with improved outcomes in terms of prolonging life in some women (platinum‐sensitive disease). In particular, surgery removing all visible disease is associated with a significant improvement in survival, although this may be due to the cancer biology facilitating surgery, rather than the surgery itself. We conclude from the current evidence that surgery with the aim of removing all visible disease should be considered in women with recurrent ovarian cancer on an individual basis. However, the data are limited to non‐randomised studies with a median age of women in their 50s and early 60s, which may not be representative of all women with ovarian cancer. The risks of major surgery need to be carefully balanced against potential benefits on a case‐by‐case basis.

Background

Description of the condition

Ovarian cancer is the sixth most common cancer among women. Worldwide there are more than 200,000 new cases of ovarian cancer each year, accounting for around 4% of all cancers diagnosed in women with approximately 6.6 new cases per 100,000 women per year (GLOBOCAN 2008; Hannibal 2008). A woman's risk of developing ovarian cancer by age 75 years varies between countries, ranging from 0.5% to 1.6% (IARC 2002). In Europe, just over one‐third of women with ovarian cancer are alive five years after diagnosis (EUROCARE 2003). The poor survival associated with ovarian cancer is largely because most women are diagnosed when the cancer is already at an advanced stage (Jemal 2008).

Epithelial ovarian cancer accounts for about 90% of ovarian cancers, the remaining 10% arise from germ cells or the sex cords and stroma of the ovary. Approximately 75% to 80% of epithelial ovarian cancers are of serous histological type, less common are mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, Brenner and undifferentiated cancers (Scully 1998).

Most women with ovarian cancer have widespread disease at presentation (Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III to IV) (Appendix 1). This may be due to relatively early spread and implantation of high‐grade serous cancers to the rest of the peritoneal cavity. In addition, presenting symptoms such as abdominal pain and swelling, gastrointestinal symptoms, and pelvic pain, are often unrecognised leading to possible delay in diagnosis (Goff 2000; Smith 2005).

Description of the intervention

Surgery is the first step in the initial diagnosis and staging of ovarian cancer. The standard management of primary ovarian cancer is optimal cytoreductive surgery (usually defined as reduction of residual disease to less than 1 to 2 cm) followed by platinum‐based chemotherapy (Bristow 2002; Delgado 1984; Hacker 1983; Hoskins 1994; Piver 1988). In a randomised trial, women with stage IIIc and IV ovarian cancer randomised to neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval cytoreduction had similar survival compared to women randomised to primary cytoreductive surgery followed by chemotherapy (Vergote 2011). The postoperative complications and mortality rates were lower after interval cytoreduction. The most important independent prognostic factor for overall survival (OS) was complete cytoreduction (no residual tumour) after primary or interval surgery (Vergote 2011).

Most women with primary ovarian cancer achieve remission on this combination therapy. The theoretical benefit from cytoreductive surgery relates to removing large tumour volumes that have a decreased growth fraction and poor blood supply, thereby improving the efficacy of chemotherapeutical agents (Boente 1998). For women achieving clinical remission after completion of initial treatment, most (60%) with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer will ultimately develop recurrent disease within five years (Burke 1994).

Secondary cytoreductive surgery is defined as surgery after completion of the primary treatment, and a period of remission, to further debulk the recurrent tumour. Surgery in the recurrent setting aims at prolongation of survival and is not curative. The apparent benefits of optimal primary surgery in advanced ovarian cancer have prompted investigations into the role of secondary surgery for recurrent disease after a period of clinical remission. These studies, which included a heterogeneous group of women, suggested that secondary cytoreductive surgery may have survival benefits in selected women (Gungor 2005; Tebes 2007). In addition, various chemotherapeutic agents including platinum are often given after secondary cytoreductive surgery.

One meta‐analysis on surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer complete cytoreductive surgery was shown to be independently associated with increased overall post‐recurrence survival time (Bristow 2009).

A number of chemotherapeutic agents are active in recurrent ovarian cancer including a combination of platinum and paclitaxel (Gonzalez‐Martin 2003; Parmar 2003). Other chemotherapeutic agents with activity in recurrent ovarian cancer include: topotecan, etoposide, doxycycline and bevacizumab (Avastin) (Bookman 1998; Markman 2004). Newer chemotherapeutic agents have shown activity in recurrent ovarian cancer and response rates of 20% to 30% have been described (Ozols 2005; Wright 2006). These chemotherapeutic agents are sometimes given within research protocols. Response to these agents is often short‐lived and they have a significant toxicity profile (Munkarah 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

The standard treatment of women with recurrent ovarian cancer remains poorly defined. Surgical debulking (cytoreduction) may be associated with improved outcomes in terms of survival in selected cases (platinum‐sensitive disease), with no residual disease emerging as the 'best' surgical objective. A systematic review and meta‐analysis is essential to make a reliable evaluation of the potential benefits and risks of surgical cytoreduction with or without adjuvant chemotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer. One systematic review on cytoreductive surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer suggested that complete cytoreduction confers survival benefit (Bristow 2009). A Cochrane review (Galaal 2010) did not identify any studies that compared the effectiveness and safety of secondary surgical cytoreduction to chemotherapy alone for women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Therefore it is important to review the current evidence whether secondary cytoreductive surgery with or without adjuvant is associated with a survival benefit in women with recurrent ovarian cancer. In addition, it is important to evaluate the harms of surgery and chemotherapy in a non‐curative setting, so that women and their clinicians can adequately weigh the pros and cons of proposed treatment options.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of optimal secondary cytoreductive surgery for women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

To assess the impact of various residual tumour sizes, over a range between 0 cm and 2 cm, on OS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

There are no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assigning women to sub‐optimal cytoreductive surgery versus complete cytoreduction as yet. Therefore this review was based on retrospective and prospective non‐randomised data. We only included data from prospective and retrospective cohort studies and unselected case series of 50 or more women that included concurrent comparison groups. Data collected from RCTs were retrospective as groups of women were randomised to surgery, where residual disease was categorised based on microscopic (no visible disease), optimal and sub‐optimal disease without taking into account the method of surgical intervention.

Case‐control studies, studies that did not have concurrent comparison groups and case series of fewer than 50 women were excluded.

In order to minimise selection bias, we included only studies that used statistical adjustment for baseline case mix using multivariable analyses (e.g. age, stage, grade, etc.).

Types of participants

Adult women (over age 18 years) diagnosed with platinum‐sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer who received secondary cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant platinum‐based chemotherapy.

Women with other concurrent malignancies were excluded.

Types of interventions

Intervention: secondary optimal cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant platinum‐based chemotherapy. We only included studies that defined optimal cytoreduction as surgery leading to residual tumours with a maximum diameter of any threshold up to 2 cm.

Comparison: women who had secondary surgery resulting in residual disease, which did not meet the criteria specified in the study as 'optimal', followed by adjuvant platinum‐based chemotherapy.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes

OS: survival until death from all causes. Survival had been assessed from the time when women were diagnosed with recurrent disease.

Secondary outcomes

Progression‐free survival (PFS).

Quality of life (QoL), measured using a scale that has been validated through reporting of norms in a peer‐reviewed publication.

Adverse events (CTCAE 2006):

direct surgical morbidity (e.g. death within 30 days; injury to bladder, ureter, blood vessels, small bowel or colon), presence and complications of adhesions, febrile morbidity, intestinal obstruction, haematoma, local infection);

surgically related systemic morbidity (chest infection, thromboembolic events (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), cardiac events (cardiac ischaemias and cardiac failure), cerebrovascular accident);

recovery: delayed discharge, unscheduled re‐admission;

chemotherapy toxicity;

other.

Grades of chemotherapeutic toxicity were extracted and grouped as:

haematological (leukopenia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, haemorrhage);

gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhoea, liver, proctitis);

genitourinary;

skin (stomatitis, mucositis, alopecia, allergy);

neurological (peripheral and central);

pulmonary.

Search methods for identification of studies

Papers in all languages were sought and translations carried out when necessary.

Electronic searches

See: Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group methods used in reviews. The following electronic databases were searched:

the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Collaborative Review Group's Trial Register;

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) Issue 11, 2012;

MEDLINE to December 2012:

EMBASE to December 2012

The MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL search strategy based on terms related to the review topic are presented in Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, respectively.

For databases other than MEDLINE, the search strategy has been adapted accordingly.

All relevant articles found had been identified on PubMed and using the 'related articles' feature, a further search had been carried out for newly published articles.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

We searched Metaregister, Physicians Data Query, www.controlled‐trials.com/rct, www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials and Gynaecologic Oncologists of Canada (http://www.g‐o‐c.org) for ongoing trials.

Handsearching

We handsearched the following reports of conferences:

Gynecologic Oncology (Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncologists);

Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society (IGCS), and the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO);

British Journal of Cancer;

British Cancer Research Meeting;

Annual Meeting of European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO);

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO);

BioMed (open text publisher); American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) conferences.

We searched the Journal of Ovarian Research (www.ovarianresearch.com/home/).

Reference lists and correspondence

We checked the citation lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field to identify further reports of studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to the reference management database Endnote X5.0.1, removed duplicates and two review authors (KG, TA) examined the remaining references independently. We excluded those studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (KG, TA) assessed the eligibility of retrieved papers independently and resolved disagreements by discussion between two review authors (KG and TA) or by appeal to a third review author (AB). We documented reasons for exclusion (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Data extraction and management

We extracted data for included studies, as recommended in Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This included data on the following:

author, year of publication and journal citation (including language);

country;

setting;

inclusion and exclusion criteria;

study design, methodology;

-

study population:

total number enrolled;

participant characteristics;

age;

co‐morbidities;

-

ovarian cancer details at diagnosis:

FIGO stage;

histological cell type;

tumour grade;

extent of disease;

disease‐free interval;

number of recurrences;

total number of intervention groups;

-

intervention details:

details of secondary cytoreductive surgery

type of surgeon (gynae‐oncologist, gynaecologist, general surgeon);

experience of surgeon;

-

details of chemotherapy:

dose;

cycle length;

combination;

details of best supportive care;

risk of bias in study (see below);

duration of follow‐up;

-

outcomes ‐ OS, PFS, QoL, patient satisfaction and adverse events:

for each outcome: outcome definition (with diagnostic criteria if relevant);

unit of measurement (if relevant);

for scales: upper and lower limits, and whether high or low score was good;

results: number of participants allocated to each intervention group;

for each outcome of interest: sample size; missing participants.

Data on outcomes were extracted as below

For time‐to‐event (OS) data, we extracted the log of the hazard ratio [log(HR)] and its standard error from trial reports; if these are not reported, we attempted to estimate them from other reported statistics using the methods of Parmar 1998.

Where possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, in which participants are analysed in groups to which they were assigned.

The time points at which outcomes were collected and reported had been noted.

Two review authors (KG, TA) independently abstracted data onto a data abstraction form specially designed for the review. The review authors resolved differences of opinion by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AB) when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included RCTs was assessed using the following questions and criteria.

Sequence generation

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

This item was scored as being 'at high risk of bias' as given the scope of the review, randomisation within a study was not feasible.

Allocation concealment

Was allocation adequately concealed?

This item was scored as being 'at high risk of bias' as given the scope of the review, concealment of the allocation within a study was not applicable.

Blinding

Assessment of blinding had been restricted to blinding of outcome assessors, since it is generally not possible to blind participants and treatment providers to surgical interventions.

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Yes.

No.

Unclear.

Incomplete reporting of outcome data

We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were not reported at the end of the study; we noted if loss to follow‐up was not reported.

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Yes, if fewer than 20% of women were lost to follow‐up and reasons for loss to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms.

No, if more than 20% of women were lost to follow‐up or reasons for loss to follow‐up differed between treatment arms.

Unclear if loss to follow‐up was not reported.

Selective reporting of outcomes

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Yes, for example, if review reports all outcomes specified in the protocol.

No.

Unclear.

Other potential threats to validity

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

Yes.

No.

Unclear.

The risk of bias in non‐randomised studies was assessed in accordance with four additional criteria.

Cohort selection

-

Was the cohort studied representative of women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer?

Yes, if representative of women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

No, if group of women was selected.

Unclear, if selection of group was not described.

Comparability of treatment groups

-

Were there no differences between the two groups or differences controlled for, in particular with reference to age, FIGO stage, disease‐free interval, histology, type and experience of surgeon, number of recurrences and dose and duration of chemotherapy?

Yes, if at least three of these characteristics were reported and any reported differences were controlled for.

No, if the two groups differed and differences were not controlled for.

Unclear, if fewer than three of these characteristics were reported, even if there were no other differences between the groups, and other characteristics had been controlled for.

The risk of bias tool had been applied independently by two review authors (KG, TA) and differences resolved by discussion or by appeal to a third review author (AB). Results had been presented in both a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. Results of meta‐analyses had been interpreted in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We used the following measures of the effect of treatment.

For time to event data, we used the HR to compare the risk of death or disease progression in the treatment group with that in the control group.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for the primary outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials that cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003) and by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001). If there is evidence of substantial heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this had been investigated and reported.

Data synthesis

If sufficient, clinically similar studies were available their results were pooled in meta‐analyses. Adjusted summary statistics were used.

For time‐to‐event data, HRs had been pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of RevMan 5 (RevMan 2011).

Random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting were used for all meta‐analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy identified 522 unique references. The title and abstract screening of these references identified 33 studies as potentially eligible for the review. The full‐text screening of the 33 studies excluded 24 for the reasons described in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. The remaining nine studies met our inclusion criteria and are described in the table Characteristics of included studies.

Searches of the grey literature did not identify any additional relevant studies.

Included studies

The nine included studies (Ayhan 2006; Chi 2006; Eisenkop 2000; Harter 2006; Oksefjell 2009; Salani 2007; Scarabelli 2001; TIAN 2010; Zang 2000) assessed a total of 1194 women.

The number of women included in all studies varied from 267 women in the Harter 2006 study to 60 women in the Zang 2000 study.

Design

Retrospective studies comprised seven out of the nine included studies (Ayhan 2006; Chi 2006; Harter 2006; Oksefjell 2009; Salani 2007; TIAN 2010; Zang 2000). Two studies were prospective cohort studies (Eisenkop 2000; Scarabelli 2001).

Participant characteristics

Women diagnosed with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer at least of six months post primary treatment. The median age reported for women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer varied between 49 and 75 years.

Intervention details

SCR surgery for women with platinum‐sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. All studies commented on the surgery to include resection of the recurrent tumour, as well as resection of viscera, with the aim of removing all visible disease, if possible. In these studies the majority (87‐100%) of women received postoperative chemotherapy with most receiving platinum‐based chemotherapy.

Outcomes

The median duration of follow‐up varied from 26 months (TIAN 2010) to 36.9 months (Chi 2006). The duration of follow‐up was not reported in four studies (Eisenkop 2000; Harter 2006; Oksefjell 2009; Zang 2000).

All nine studies reported OS; all of which used appropriate statistical techniques (HRs to correctly allow for censoring), but three studies (Chi 2006; Eisenkop 2000; Salani 2007) did not report sufficient estimates for OS to include in forest plots or meta‐analyses. These studies reported either only P values from the Cox model or the point estimate of the HR with the Cox P value. Prognostic factors were adjusted for in the analysis of survival outcomes in all nine included studies using Cox regression.

The HR in the Ayhan 2006 study was adjusted for: residual disease; disease‐free interval; outcome of primary debulking surgery; chemotherapy before secondary cytoreduction; tumour histology; number of recurrent sites; median survival of women with only one recurrence and women with two or more recurrences; interval from appearance of recurrent disease to secondary cytoreduction and maximal diameter of the recurrent disease; age; stage and grade.

The HR in the Chi 2006 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; FIGO stage; tumour histology; tumour grade; carcinomatosis at first debulking; residual disease after first debulking; second‐look findings; method of detection; site of largest tumour; ascites; number of sites; age; CA‐125 and disease‐free interval.

The HR in the Eisenkop 2000 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; age; Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) performance status; tumour grade; histology; ascites (presence or absence); location of largest recurrent tumour; subspecialty training of physicians involved at primary cytoreduction; number or specific types of procedures performed at secondary cytoreduction; symptoms (presence or absence); physical findings; preoperative radiographic (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) findings; disease‐free interval; administration of chemotherapy prior to surgery; and the largest size of recurrent tumour.

The HR in the Harter 2006 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG); ascites; localisation of recurrence in preoperative diagnosis in pelvis; platinum‐based chemotherapy after surgery for recurrence and treatment‐free interval (< six months vs. six to 12 months and < six months vs. > 12 months).

The HR in the Oksefjell 2009 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; FIGO stage; degree of differentiation; residual disease after primary operation; chemotherapy and age (years) at relapse; treatment group and treatment‐free interval.

The HR in the Salani 2007 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; age; second‐look outcome (positive and negative); elevated CA‐125; histology; grade; ascites; greatest dimension of recurrence; number of recurrence sites (imaging and actual) and diagnosis‐to‐recurrence interval (≥ 18 months).

The HR in the Scarabelli 2001 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; residual tumour after primary surgery; recurrence‐free interval; prior chemotherapy combination from primary surgery; lymph node status and age.

The HR in the TIAN 2010 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; FIGO stage; histology; grade; primary cytoreduction; median PFS; ascites; recurrent lesions; maximum diameter of the largest recurrent site; intestinal resection and chemotherapy after secondary cytoreductive surgery.

The HR in the Zang 2000 study was adjusted for: residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; residual disease after secondary cytoreduction; progression‐free interval and refractory ascites (ascites presenting in company with recurrent disease).

For the distribution of these factors at baseline for each study by treatment arm see the table Characteristics of included studies.

Adverse events and QoL were not reported by treatment arm or to a satisfactory level in any of the studies.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐four references were excluded, after obtaining the full text, for the following primary reasons.

Seventeen studies (Benedetti 2006; Berek 1983; Bristow 2003; Eisenkop 1995; Gadducci 2000; Gronlund 2005; Gungor 2005; Helm 2007; Landoni 1998; Matsumoto 2006; Morris 1989; Munkarah 2001; Park 2006; Tay 2002; Vaccarello 1995; van der Vange 2000; Zanon 2004) were excluded because the study did not include at least 50 women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Two studies (Tebes 2007; van der Vange 2000) did either not report multivariate analyses or did not include residual disease as a variable.

Three studies (Goto 2011; Zang 2000a; Zang 2004) did not report survival by residual disease.

One study (Bristow 2009) had no comparison group.

One study (Karam 2007) was retrospective study for secondary and tertiary cytoreduction.

One study (Zang 2003) did not report the results of secondary surgery by residual disease. Instead the authors included the effect of giving the women 'redebulking surgery' (secondary cytoreduction) or secondary chemotherapy in a multivariate Cox regression analysis for OS.

For further details of all the excluded studies see the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

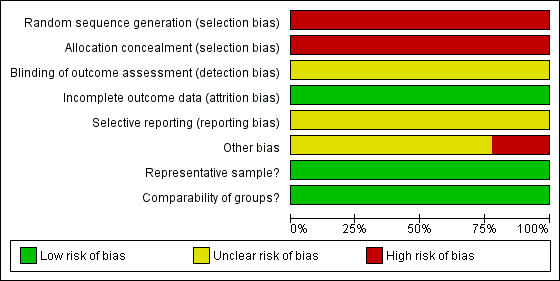

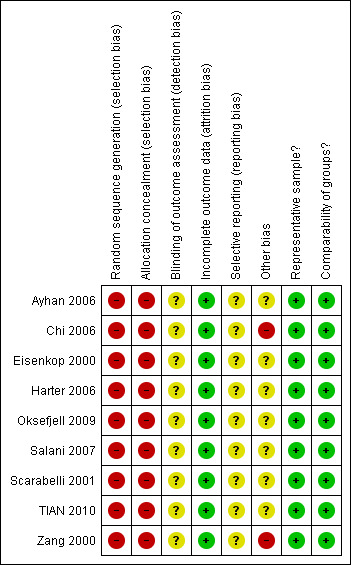

Although the included studies were a combination of prospective and retrospective studies, the comparison of residual disease was retrospective in nature in all cases and consequently all studies were at high risk of bias as they, at most, only satisfied three of the eight criteria used to assess risk of bias (see Figure 1; Figure 2).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The method of sequence generation and allocation of concealment was not applicable to the studies included in the review, so these individual items were flagged up as being at high risk of bias for all studies. Blinding of the outcome assessor was not reported in any of the studies and it was unclear whether there had been selective reporting of outcomes in all of the studies. There was insufficient information to make judgement on whether any additional risk factor for bias existed, apart from the Chi 2006 and Zang 2000 studies. In the Chi 2006 study, details of specific information on outcomes of comparable women with recurrent disease, who were managed without secondary cytoreduction, were lacking, while in the Zang 2000 study details of women who received chemotherapy pre‐ and post‐secondary cytoreductive surgery was not provided. In all included studies women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques, which were used to account for any censoring. Additionally, all studies appeared to include a representative sample of women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via secondary cytoreductive surgery and multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in a Cox regression model for OS in all studies, making the groups comparable.

Effects of interventions

Meta‐analyses of survival are based on HRs that were adjusted for prognostic variables (see Included studies for full details).

Overall survival (risk of death from all causes)

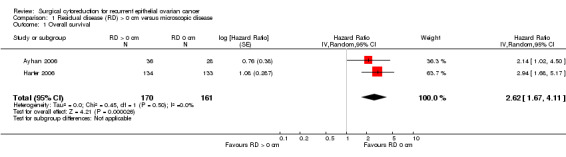

Residual disease > 0 cm (macroscopic disease; any visible tumour of any size) versus microscopic disease

(See Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Residual disease (RD) > 0 cm versus microscopic disease, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

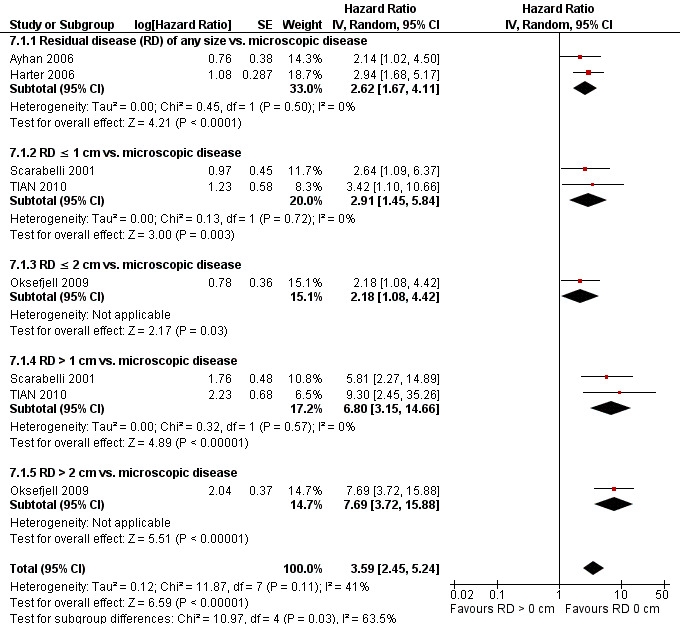

Four studies (Ayhan 2006; Eisenkop 2000; Harter 2006; Salani 2007) reported a comparison of microscopic disease (no visible residual disease) versus macroscopic disease (visible residual disease) in a multivariate analysis, but Eisenkop 2000 did not report a confidence interval or a standard error of the log HR and Salani 2007 only reported the significance probabilities of significant variables in the Cox model. Meta‐analysis of two studies (Ayhan 2006; Harter 2006), assessing 331 participants, found that women with macroscopic disease after secondary cytoreductive surgery had over 2.5 times the risk of death compared to women with only microscopic disease (HR 2.62, 95% CI 1.67 to 4.11; P < 0.0001). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance) was not important (I2 = 0%).

The Eisenkop 2000 study found that women with no visible disease after secondary cytoreductive surgery had 87% less risk of death compared to women with macroscopic disease (HR 0.13; P value = 0.007). The median survival after complete secondary cytoreduction was 44.4 months versus 19.3 months for sub‐optimal cytoreduction (P value = 0.007). The Salani 2007 study found that only three factors were associated independently and significantly with post‐recurrence and OS and these included a diagnosis‐to‐recurrence interval ≥ 18 months (P = 0.001), complete cytoreduction after secondary cytoreductive surgery (P < 0.001) and the number of recurrence sites (imaging (P = 0.005) and actual (P = 0.06)). The median survival was 50 months for women with microscopic disease after secondary debulking and 7.2 months for women who had visible residual disease.

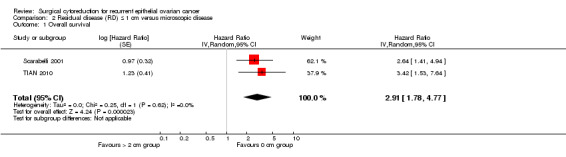

Residual disease < 1 cm versus microscopic disease

(See Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Residual disease (RD) ≤ 1 cm versus microscopic disease, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

Meta‐analysis of two studies (Scarabelli 2001; TIAN 2010), assessing 272 participants, found that women who were optimally debulked (residual disease < 1 cm) after secondary cytoreductive surgery had nearly three times the risk of death compared to women with only microscopic disease (HR 2.91, 95% CI 1.78 to 4.77). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance was not important (I2 = 0%).

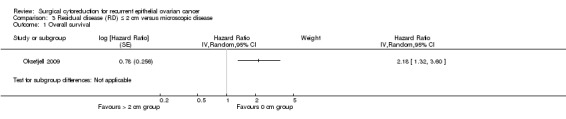

Residual disease < 2 cm versus microscopic disease

(See Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Residual disease (RD) ≤ 2 cm versus microscopic disease, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

The Oksefjell 2009 study, which assessed 217 participants, found that women who were optimally debulked (residual disease < 2 cm) after secondary cytoreductive surgery had more than twice the risk of death compared to women with only microscopic disease (HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.32 to 3.60). The median survival was 4.5 years in women who had cytoreduction to no residual disease compared to 2.3 years when ≤ 2 cm macroscopic disease was left.

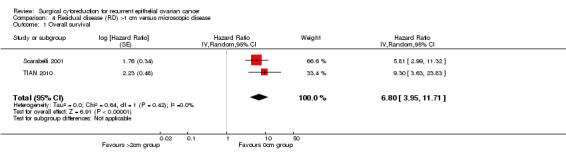

Residual disease > 1 cm versus microscopic disease

(See Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Residual disease (RD) >1 cm versus microscopic disease, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

Meta‐analysis of two studies (Scarabelli 2001; TIAN 2010), assessing 217 participants, found that women who were sub‐optimally debulked (residual disease >1 cm) after secondary cytoreductive surgery had nearly seven times the risk of death compared to women with only microscopic disease (HR=6.80, 95% CI: 3.95 to 11.71). The percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance is not important (I2 = 0%).

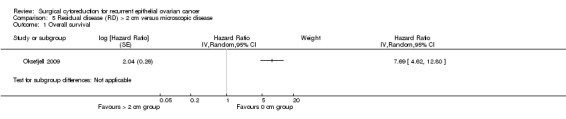

Residual disease >2 cm versus microscopic disease

(See Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Residual disease (RD) > 2 cm versus microscopic disease, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

The Oksefjell 2009 study, which assessed 217 participants, found that women who were sub‐optimally debulked (residual disease > 2 cm) after secondary cytoreductive surgery had more than seven and a half times the risk of death compared to women with only microscopic disease (HR 7.69, 95% CI 4.62 to 12.80). The median survival was 4.5 years in women who had complete cytoreduction compared to 0.7 years in women left with residual disease > 2 cm.

Residual disease > 0.5 cm versus residual disease < 0.5 cm

The authors of the Chi 2006 study reported estimates for a comparison of residual disease less than 0.5 cm versus more than 0.5 cm in univariate analyses, but only reported the significance probabilities of significant variables in multivariate analyses. They found that only disease‐free interval (P = 0.004), the number of sites of recurrence (P = 0.01) and residual disease after secondary cytoreduction (P value < 0.001) were significant in multivariate analysis. The median survival was 56 months for women who had residual disease that measured ≤ 0.5 cm after secondary debulking and 27 months for women who had residual disease that measured > 0.5 cm.

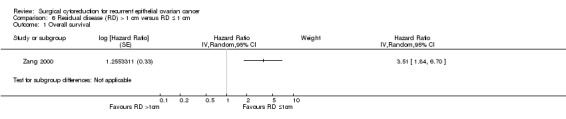

Residual disease > 1 cm versus residual disease < 1 cm

(See Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Residual disease (RD) > 1 cm versus RD ≤ 1 cm, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

The Zang 2000 study, which assessed 106 participants, found that women who were sub‐optimally debulked (residual disease > 1 cm) after secondary cytoreductive surgery had around three and a half times the risk of death compared to women who were optimally debulked with residual disease < 1 cm (HR 3.51, 95% CI 1.84 to 6.70). Median survival was 19 months for women who had optimal cytoreduction versus 8 months for women with sub‐optimal cytoreduction.

No residual disease (microscopic disease) versus any residual disease

(See Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Overall survival, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

Combining the results from all of the included studies has suggested that there is a significant improvement in the OS when the outcome of cytoreductive surgery is no visible disease (microscopic disease), see Figure 3.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: Overall survival, microscopic disease vs. any residual disease (RD).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found two prospective and seven retrospective studies that included a multivariate analysis that met our inclusion criteria, although the comparison of residual disease was retrospective in nature in all cases. These studies assessed survival after secondary cytoreductive surgery in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Meta‐ and single‐study analyses clearly show the prognostic importance of complete cytoreduction to microscopic disease as OS was significantly prolonged in these groups of women (most studies showed a large statistically significant greater risk of death in all residual disease groups compared to microscopic disease). RFS was not reported in any of the studies. The fact that all of the studies included at least 50 women and used statistical adjustment for important prognostic factors increased the level of certainty in estimates, despite the fact the review was restricted to non‐randomised retrospective studies (see Figure 3).

Only the Zang 2000 study compared sub‐optimal (> 1 cm) versus optimal (< 1 cm) cytoreduction and this study showed the importance of trying to debulk the tumour to less than 1 cm if microscopic disease cannot be achieved (HR 3.51, 95% CI 1.84 to 6.70). Similarly, one study (Chi 2006) found that women whose tumour had been cytoreduced to less than 0.5 cm had less risk of death compared to those with residual disease greater than 0.5 cm (HR not reported; P value < 0.001).

Adverse events, QoL and cost‐effectiveness were not reported in any of the studies. QoL may be of additional importance to women who present with recurrent disease and have obvious physical limitations to their life after developing the disease and as a result of the effects of receiving treatment. None of the included studies had QoL assessments as a component of the studies. Treatment‐related morbidity very often degrades the quality of the time that people live, which is especially important after the completion of treatment for advanced cancer where people have poor prognosis and will want to enjoy a comfortable standard of living during their final months. However, this needs to be considered in the context of the findings from this review in that women in whom complete cytoreduction is achieved have a much better survival, suggesting that the potential benefits of prolonging survival may outweigh the disadvantages of any short‐term morbidities associated with the surgical procedure. Only one study (Zang 2000) compared residual disease greater and less than 1 cm (see above) and one study (Chi 2006) greater or less than 0.5 cm. All of the studies emphasised the importance of making every effort to try and reduce the tumour to microscopic disease.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence from this review indicates that complete (no visible residual disease) and optimal (residual disease < 1 cm) secondary surgical cytoreduction is associated with prolonged survival in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer compared to sub‐optimal (residual disease > 1 cm). Although the findings do not enable us to determine whether it is a direct effect of the surgical intervention that women with complete cytoreduction do better, if surgery is undertaken, every effort should be made to reduce the tumour to microscopic disease. Where this is considered not achievable, attempts should be made to obtain optimal cytoreduction, defined as residual disease less than 1 cm. There was no evidence on whether or not residual disease defined as being less than 2 cm still had any significant survival benefit when compared to residual disease greater than this threshold.

The criteria for assignment of women to secondary cytoreductive surgery were selective in most cases so statistical adjustment was necessary to minimise bias. The review benefited from having restrictive inclusion criteria. By only including studies with 50 or more women, satisfactory conclusions could be made in all of the multivariate analyses as the number of women in each study was adequate. One major limitation of the studies is that they were largely confined to younger women and those with a good performance status (median age in several studies in 50s) and the results may therefore not be generalisable to the wider patient population.

Quality of the evidence

There was a high risk of bias due to the non‐randomised studies and retrospective nature of the analyses where, despite statistical adjustment for important prognostic factors, selection bias was still likely to be of particular concern.

The nine studies that met our inclusion criteria included retrospective analyses and were all at a high risk of bias. As the surgical efforts may vary with age, performance status, and intra‐operative events or complications, which were not reported thoroughly, we included only sufficiently large studies that controlled for various co‐factors using multivariate analysis in order to reduce the possibility of selection bias. The exact reasons for performing one type of surgery over another were not well documented and it was likely that women in generally poor health would be subjected to less aggressive surgery (or no surgery at all) and thus would be more likely to have larger residual disease. This would most likely result in poorer survival, although we applied strict inclusion criteria and included studies that used statistical adjustment. The studies reported adjusted HR estimates using Cox proportional hazards models. An HR is the best statistic to summarise the difference in risk between two intervention groups over the duration of a study when there is 'censoring', that is the time to death is unknown for some women as they are still alive at the end of the study. All studies were at high risk of bias as they, at most, only satisfied three of the criteria used to assess risk of bias (Figure 2). Many of the individual risk of bias items could not be scored as having low risk of bias given the fact that only non‐randomised designs were identified; and we were cautious when deciding whether studies were selectively reported or whether any additional source of bias may have been present and scored most of these items as being unclear.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, and all studies were sifted and data extracted by two review authors working independently. We were not restrictive in our inclusion criteria with regards to types of studies as we included non‐randomised studies with concurrent comparison groups that used multivariate analyses. We attempted to ensure that we did not overlook any relevant evidence by searching a wide range of reasonable‐quality non‐randomised study designs (studies that did not have concurrent comparison groups and case series of fewer than 50 women were excluded). A significant threat to the validity of the review is likely to be publication bias, that is studies that did not find the treatment to have been effective may not have been published. We found an insufficient number of studies that met the inclusion criteria to assess this possibility adequately.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are consistent with the previously published review by Bristow 2009, which showed a direct correlation between degree of cytoreduction and survival so that for each 10% increase in the proportion of women undergoing complete cytoreductive surgery was associated with a 3.0‐month increase in median cohort survival time. He concluded that, among women undergoing operative intervention for recurrent ovarian cancer, the proportion of women undergoing complete cytoreductive surgery is independently associated with overall post‐recurrence survival time. For this select group of women, the surgical objective should be resection of all macroscopic disease.

A Cochrane systematic review studying the effects of complete and optimal cytoreduction in the treatment of primary (non‐recurrent) epithelial ovarian cancer came to a similar conclusion and recommendation (Elattar 2011), which fits with the natural history of the disease that is most likely to progress in the abdominal cavity before it leads to death. Therefore the beneficial effects of complete as well as optimal to cytoreduction in the primary setting may continue to be present when surgery is performed in the secondary setting as shown in this review. However, this is with the caveat that optimal surgery may be a strong prognostic indicator in both the primary and recurrent setting and a direct therapeutic effect has yet to be robustly demonstrated.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In women with recurrent ovarian cancer, ability to achieve surgery with complete cytoreduction (no visible residual disease) is associated with significant improvement in overall survival. However, in the absence of randomised controlled trial evidence, it is not clear whether this is solely due to surgical effect or due to tumour biology. Indirect evidence would support surgery to achieve complete cytoreduction in some women, if this is not possible, the aim should be to debulk disease (nodules less than 0.5 cm or 1 cm). The risks of major surgery need to be carefully balanced against potential benefits on a case‐by‐case basis.

Implications for research.

There is a need for a trial that randomly assigns women with recurrent ovarian cancer to surgery.

Future trials need to clarify which groups of women would benefit from which treatment by stratifying women at trial entry for age, performance status, prior treatments, site of disease and co‐morbidity.

Quality of life and symptom scores should be assessed as well as primary outcomes such as overall survival.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 September 2016 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 10, 2010 Review first published: Issue 2, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 February 2015 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 27 March 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 29 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jo Morrison for clinical and editorial advice, Jane Hayes for designing the search strategy, and Gail Quinn and Clare Jess for their contribution to the editorial process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. FIGO staging

|

Stage I Stage I ovarian cancer is limited to the ovaries.

* [Note: the term malignant ascites is not classified. The presence of ascites does not affect staging unless malignant cells are present.] Stage II Stage II ovarian cancer is tumour involving 1 or both ovaries with pelvic extension or implants (or both).

Different criteria for allotting cases to stage IC and stage IIC have an impact on diagnosis. To assess this impact, of value would be to know if rupture of the capsule was (1) spontaneous or (2) caused by the surgeon; and, if the source of malignant cells detected was (1) peritoneal washings or (2) ascites. Stage III Stage III ovarian cancer is tumour involving 1 or both ovaries with microscopically confirmed peritoneal implants outside the pelvis. Superficial liver metastasis equals stage III. Tumour is limited to the true pelvis but with histologically verified malignant extension to small bowel or omentum.

Stage IV Stage IV ovarian cancer is tumour involving 1 or both ovaries with distant metastasis. If pleural effusion is present, positive cytological test results must exist to designate a case to stage IV. Parenchymal liver metastasis equals stage IV (Shepherd 1989). |

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Ovarian Neoplasms/ 2 (ovar* adj5 cancer*).mp. 3 (ovar* adj5 neoplas*).mp. 4 (ovar* adj5 carcinom*).mp. 5 (ovar* adj5 malignan*).mp. 6 (ovar* adj5 tumor*).mp. 7 (ovar* adj5 tumour*).mp. 8 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9 exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ 10 surg*.mp. 11 "surgery".fs. 12 11 or 10 or 9 13 debulk*.mp. 14 cytoreduc*.mp. 15 13 or 14 16 8 and 12 and 15 17 "randomized controlled trial".pt. 18 "controlled clinical trial".pt. 19 randomized.ab. 20 randomly.ab. 21 trial.ab. 22 groups.ab. 23 exp Cohort Studies/ 24 cohort*.mp. 25 case adj series.mp. 26 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27 16 and 26 key: mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word fs=floating subheading

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

EMBASE Ovid

exp Ovary Tumor/

(ovar* adj5 cancer*).mp.

(ovar* adj5 neoplas*).mp. [

(ovar* adj5 carcinom*).mp.

(ovar* adj5 malignan*).mp.

(ovar* adj5 tumor*).mp.]

(ovar* adj5 tumour*).mp.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

exp Surgery/

surg*.mp.

su.fs.

9 or 10 or 11

debulk*.mp.

cytoreduc*.mp.

13 or 14

8 and 12 and 15

exp Controlled Clinical Trial/

random*.mp.

trial*.mp.

group*.mp.

exp Cohort Analysis/

cohort*.mp.

series.mp.

17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23

16 and 24

key: mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name, fs=floating subheading

Appendix 4. CENTRAL search strategy

CENTRAL, Issue 11 2012

MeSH descriptor Ovarian Neoplasms explode all trees

ovar* near/5 cancer*

ovar* near/5 neoplas*

ovar* near/5 carcinom*

ovar* near/5 malignan*

ovar* near/5 tumor*

ovar* near/5 tumour*

(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7)

MeSH descriptor Surgical Procedures, Operative explode all trees

surg*

Any MeSH descriptor with qualifier: SU

(#9 OR #10 OR #11)

debulk*

cytoreduc*

(#13 OR #14)

(#8 AND #12 AND #15)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Residual disease (RD) > 0 cm versus microscopic disease.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 2 | 331 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 2.62 [1.67, 4.11] |

Comparison 2. Residual disease (RD) ≤ 1 cm versus microscopic disease.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 2.91 [1.78, 4.77] |

Comparison 3. Residual disease (RD) ≤ 2 cm versus microscopic disease.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 4. Residual disease (RD) >1 cm versus microscopic disease.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 6.80 [3.95, 11.71] |

Comparison 5. Residual disease (RD) > 2 cm versus microscopic disease.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 6. Residual disease (RD) > 1 cm versus RD ≤ 1 cm.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 7. Overall survival.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 5 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 3.59 [2.45, 5.24] | |

| 1.1 Residual disease (RD) of any size vs. microscopic disease | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 2.62 [1.67, 4.11] | |

| 1.2 RD ≤ 1 cm vs. microscopic disease | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 2.91 [1.45, 5.84] | |

| 1.3 RD ≤ 2 cm vs. microscopic disease | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 2.18 [1.08, 4.42] | |

| 1.4 RD > 1 cm vs. microscopic disease | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 6.80 [3.15, 14.66] | |

| 1.5 RD > 2 cm vs. microscopic disease | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 7.69 [3.72, 15.88] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ayhan 2006.

| Methods | Retrospective study | |

| Participants |

64 women, recurrent EOC, from 1990 to 2001. Mean age of 51 years. Inclusion criteria: Women with recurrent EOC, at least 6 months post primary treatment. E xclusion criteria: Women with progressive disease (recurrence within 6 months of initial surgery). Disseminated intrahepatic or extra‐abdominal metastasis. Palliative surgery rather than a cytoreductive effort. |

|

| Interventions |

Interventions: 53 women (83%) had optimal SCR ≤ 1 cm of residual disease (28 women without macroscopic disease and 25 women with residual disease ≤ 1 cm) Comparison: 11 women (17%) had sub‐optimal cytoreduction > 1 cm residual |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: MST for optimally cytoreduced: 28 months. MST for sub‐optimally cytoreduced: 18 months. Secondary outcome: Multivariable analysis showed 3 factors were associated with a favourable outcome after SCR: optimal cytoreduction during primary surgery, optimal cytoreduction during SCR surgery and endometrioid type of tumour histological type. Analysis of SCR success: Multivariate analysis of (age, number of recurrent disease and maximal diameter of the recurrence): only age (≤ 50 years had 57.6% no macroscopic disease vs. > 50 years had 29% no macroscopic disease) and number of recurrent disease (no macroscopic disease in 92% and 31% of women with 1 and ≥ 2 recurrent disease; P value = 0.001) to be significant for maximal SCR. |

|

| Notes | 33 women (52%) had SCR included only resection of the recurrent tumour. 31 women (48%) SCR included additional visceral organ resections (intestinal and bowel resection in 17, splenectomy in 10, partial liver resection in 2 and removal of the bladder in 2). All women received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy after the SCR. 56 women (87%) had chemotherapy only. 4 women (6%) had radiation therapy only. 4 women (6%) had chemoradiation. Median follow‐up: 33.7 months. Outcome of primary surgery was significant for survival after SCR (30 months for optimal vs. 18 months for sub‐optimal). DFI significantly affected the OS duration (If DFI < 12 months, the MST was 18 months and if DFI > 12 months the MST up to 39 months). Chemotherapy before SCR has no effect of survival outcome. Authors carried out a multivariate analysis and found that optimal cytoreduction during primary cytoreduction (P value = 0.003), endometrioid‐type tumour histology (P value = 0.005) and SCR (HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.99; P value = 0.04) were all significant factors, which indicates that women who had no visible disease after SCR surgery were at less risk of death than those with visible disease. In the meta‐analysis, the reference group was reversed so that all forest plots were consistent and a HR > 1 indicated that women with residual disease > 0 cm had increased risk of death compared to those with microscopic disease |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Not done as it was retrospective study. Women who had SCR surgery were recruited after an extensive discussion by the multidisciplinary team. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Concealment of allocation irrelevant to this study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques that were used to account for any censoring. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Representative sample? | Low risk | All women had recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via SCR surgery. |

| Comparability of groups? | Low risk | Multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in Cox model for OS. |

Chi 2006.

| Methods | Retrospective study | |

| Participants |

153 women with recurrent EOC from January 1987 to December 2001. Median age of 56.5 years. Inclusion criteria: Women diagnosed with EOC who had undergone primary surgery and received platinum‐based chemotherapy. Had completed clinical remission of at least 6 months. For women who underwent second‐look surgery and received further chemotherapy, the time of the clinical remission was measured from completion of the therapy after the second‐look surgery. Exclusion criteria: Women with low malignant potential. Women who underwent surgery for correction of malignant bowel obstruction. |

|

| Interventions |

Interventions: 62 women (41%) had no macroscopic disease. 17 women (11%) had residual disease of 0.1‐0.5 cm. 21 women (14%) had residual disease of 0.6‐1.0 cm. 52% of women had residual disease that measure ≤ 0.5 cm. Comparison: 11 women (7%) had residual disease of 1.1‐2.0 cm. 41 women (27%) had residual disease of > 2 cm. 1 woman (1%) had residual disease status unknown. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: Median survival of women who had optimal cytoreduction (≤ 0.5 cm) was 56.2 months. MST of women who had sub‐optimal cytoreduction (≥ 0.5 cm) was 26.7 months. 105 women (69%) died of disease. 23 women (15%) remained alive with no evidence of disease. 25 women (16%) remained alive with disease. Secondary outcome: No perioperative mortalities. 6 (4%) intraoperative complications, all which involved bowel injuries. 6 (4%) postoperative complications. 3 women had infectious process requiring antibiotics. 2 women had venous thromboembolism. 1 woman had bleeding secondary to gastritis. On multivariate analysis: DFI, the number of sites of recurrence and residual disease after SCR retained prognostic significance |

|

| Notes | Median OS was 41.7 months. All women had a CT scan preoperatively. 129 women (84%) received platinum‐ based chemotherapy after their SCR. 21 women (14%) received non‐platinum‐ based chemotherapy. 3 women (2%) received unknown treatment. No statistically significant difference between survival of women who were left no macroscopic residual disease that measured from 0.1 cm to 0.5 cm. Median follow‐up was 36.9 months. Median DFI was 17 months. MST was 60 months for single site of recurrence. MST was 42 months for multiple sites of recurrence. MST was 28 months for women who had carcinomatosis. The only continuous factor that had prognostic significance in the univariate analysis was DFI. In general, the median survival improved significantly with longer DFIs, fewer sites of recurrence and SCR to residual disease that measured ≤ 0.5 cm. The suggestion from this study was that the objective of SCR should be to achieve residual disease that measures ≤ 0.5 cm. The following selection criteria are suggested: For women with only 1 of site of recurrence DFI is ≥ 6 months Offer SCR surgery for women with multiple recurrence sites but no carcinomatosis who have a DFI > 12 months. For women with carcinomatosis who have a DFI > 30 months (SCR may be beneficial). SCR not recommend for women who have a DFI of 6‐12 months with evidence of carcinomatosis. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | This was a retrospective non‐randomised study. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Concealment of allocation irrelevant to this study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques that were used to account for any censoring. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | High risk | Lack of specific information on outcomes of comparable women with recurrent disease who were managed without SCR. |

| Representative sample? | Low risk | All women had recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via SCR surgery. |

| Comparability of groups? | Low risk | Multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in Cox model for OS. |

Eisenkop 2000.

| Methods | Prospective study | |

| Participants |

106 women with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma from 1990 to 1998. Median age of 60.5 years. Inclusion criteria: Completion of primary surgery and chemotherapy with a clinical, radiographic and serological DFI of at least 6 months after primary adjuvant chemotherapy. Absence of unresectable extra‐abdominal or hepatic metastases. Patient willingness to be treated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery. Absence of medical contraindications to an extensive surgical procedure. Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) performance status < 4. |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: 87 women (82%) had complete cytoreduction, no visible residual disease. 3 women (3%) had residual disease < 5 mm. Comparison: 16 women (15%) had residual disease > 5 cm. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: Complete cytoreduction MST 44.4 months. Optimal/sub‐optimal cytoreduction (any residual disease); MST 19.3 months (P value = 0.007). Secondary outcome: 2 women (2%) died (1 of multiple organ failure and 1 of sepsis). 34 women (32%) had postoperative complications. 11 women (10%) had wound infection. 27 women (26%) had prolonged ileus. 10 women (9%) had septicaemia. 3 women (3%) had enterocutaneous fistula or pneumonia. 2 women (2%) had systematic candidiasis, partial fascial separation or mechanical small bowel obstruction managed surgically. 1 woman (1%) had a superior vena cava syndrome, cholecystitis, RDS, DVT, pseudomembranous colitis and a vesicovaginal fistula. Multivariate analysis: use of salvage chemotherapy before surgery, the GOG performance status and size of the largest site of recurrent disease were independent predictor of survival. Preoperative GOG performance status: survival: (0 (100%), 1 (91%), 2 (82%), 3 (47%); P value = 0.001). This study confirmed that the completeness of surgical resection independently determines the prognosis and is proven to improve survival. |

|

| Notes | Overall MST from date of SCR was 34.4 months. 64 women (60.5%) had secondary surgery before salvage chemotherapy. 42 women (39.5%) had salvage chemotherapy before secondary surgery. Among the women with bulky unresected disease: 6 women (38%) had open and closed procedure 7 women (44%) had palliative procedure such as gastrostomy or colostomy. After recovery from surgery, women received salvage therapy based on initial treatment. 34 women (32%) received IV platin‐paclitaxel therapy. 24 women (23%) were treated with other platinum‐based systemic combination therapy. 7 women (6.5%) were treated with either paclitaxel or platin‐based intraperitoneal chemotherapy. 4 women (4%) received whole abdomen radiation therapy. 5 women (5%) did not receive any therapy. Median survival for women who were not treated with salvage chemotherapy before SCR was 47% and 40% of those women survived > 5 years after recurrence. MST for women treated with salvage chemotherapy before secondary surgery was 15.8 months and 15% of those women survived > 5 years after recurrence. Majority of women had advanced disease at primary diagnosis and bulky, multifocal disease at time of recurrence (87 women (82%) had multifocal disease sites). Survival was influenced by: DFI after primary treatment (6‐12 months (median 56.8 months) vs. 13‐36 months (median 44.4 months) vs. > 36 months (median 56.8 months); P value = 0.007) The use of salvage chemotherapy before secondary surgery (chemotherapy given (median 24.9 months) vs. chemotherapy not given (median 48.4 months); P value = 0.005) Largest size of recurrent tumour (< 10 cm (median 37.3 months) vs. > 10 cm (median 35.6 months); P value = 0.04). The probability of complete cytoreduction was influenced by: The largest size of recurrent tumour (< 10 cm (90%) vs. > 10 cm (67%); P value = 0.001). Women with metastases > 10 cm in largest dimension were rendered visibly disease free 67% of the time. Use of salvage chemotherapy before secondary surgery (chemotherapy given (64%) vs. chemotherapy not given (94%); P value = 0.001). Log rank analysis revealed the DFI, use of salvage chemotherapy before secondary surgery, the largest size of recurrence disease and cytoreductive outcome to influence the probability of survival. Patient age, GOG performance status, tumour grade, histology, presence or absence of ascites, location of largest recurrence tumour, sub‐speciality training of physician involved at primary surgery, the number or specific types of procedures performed at secondary surgery and the presence or absence of symptoms, physical findings, or preoperative radiographic findings of ascites, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, or other intra‐abdominal masses did not influence the probability of survival. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | A prospective study, no randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Concealment of allocation irrelevant to this study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques that were used to account for any censoring. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Representative sample? | Low risk | All women had recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via SCR surgery. |

| Comparability of groups? | Low risk | Multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in Cox model for OS. |

Harter 2006.

| Methods | Retrospective study (DESKTOP OVAR TRIAL) | |

| Participants |

267 women with recurrent EOC. Median age 60 years From January 2000 to December 2003 from 25 institutions Exclusion criteria: Women with non‐EOC. Women with borderline tumours. Women who had operations with palliative purposes or within primary therapy (second‐look or interval operations). |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: 133 women (50%) had complete cytoreduction. 69 women (26%) had optimal cytoreduction (residual tumour of 1‐10 mm). Comparison: 22 women (8%) had sub‐optimal cytoreduction (residual tumour of 11‐20 mm). 43 women (16%) had sub‐optimal cytoreduction (residual tumour of > 20 mm). |

|

| Outcomes | MST of complete cytoreduction (without residual tumour) was 45.2 months. MST with residual tumour, irrespective of its size was 19.7 months (HR 4.33, 95% CI; P value < 0.0001). The size of residual tumour did not impact survival in women not completely debulked. MST of women with residual tumour of 1‐10 mm and > 10 mm was 19.6 and 19.7 months, respectively (P value = 0.502). Multivariate analysis: Significant factors for survival following SCR. Complete cytoreduction (residual tumour at surgery for recurrence 0 vs. > 0 mm; P value < 0.001). Absence of ascites. Application of a platinum‐containing chemotherapy. |

|

| Notes | 168 women (63%) had DFI was 12 months from primary surgery. 92% had a good performance status (ECOG). 69% had advanced disease at initial diagnosis. Some women had salvage chemotherapy before the surgery. All women received platinum‐based first‐line chemotherapy. 73% had recurrent disease localised beyond the pelvis. Post SCR treatment with platinum‐based chemotherapy in 47%. 43% had received other chemotherapy. No postoperative chemotherapy was documented for 10.5%. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | A retrospective study, no randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Concealment of allocation irrelevant to this study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques that were used to account for any censoring. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Representative sample? | Low risk | All women had recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via SCR surgery. |

| Comparability of groups? | Low risk | Multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in Cox model for OS. |

Oksefjell 2009.

| Methods | Retrospective study | |

| Participants | 789 women treated for the first recurrence EOC from 1985 to 2000 217 women with EOC who had any surgical procedure following primary debulking and chemotherapy. Inclusion criteria: Surgery for cytoreduction or for bowel obstruction. Non‐responders to chemotherapy during primary treatment. Tumour relatively localised in pelvis or upper abdomen. Age, good performance status and TFI > 6 months. Exclusion criteria: Women with borderline tumours. 571 women who got only chemotherapy at first relapse. |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: 68 women (35%) without macroscopic tumour. Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 49% of women operated with SCR intentions. Comparison: 33 women (17%) having tumour nodules ≤ 2 cm residual tumours. 21 women operated for bowel obstruction were excluded from statistical analysis biopsy the residual tumour after SCR was not registered. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: MST was 4.5 years in women who were SCR to no residuum compare to 0.7 years in women left with residual disease > 2 cm and 2.3 years when ≤ 2 cm macroscopic disease was left. Multivariate analysis: Residual tumour after SCR, TFI and age as independent prognostic factors for survival. Localised tumour remained as prognostic factor in binary logistic regression. There is a clear survival benefit for women who had undergone a secondary complete cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone at the time of first recurrence. |

|

| Notes | Treatment of the first relapse was registered in 3 groups:

Ascites and performance status were not always registered. Types of chemotherapy: Either as chemotherapy alone or as post‐SCR therapy. SCR was chosen for 217 (27%) of 789 women with recurrence EOC. At relapse significantly more women with TFI > 24 months had SCR. Significantly more women > 70 years had chemotherapy. 84 of 217 women had localised disease and MST was 3.4 years. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | A retrospective study, no randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Concealment of allocation irrelevant to this study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Women were analysed for OS using appropriate statistical techniques which were used to account for any censoring. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Representative sample? | Low risk | All women had recurrent ovarian cancer that had been cytoreduced via SCR surgery. |

| Comparability of groups? | Low risk | Multivariate analysis was used to adjust for important prognostic factors in Cox model for OS. |

Salani 2007.

| Methods | Retrospective study | |

| Participants |

55 women with recurrent EOC from September 1997 to March 2005. Median age at recurrent was 57.7 years. Inclusion criteria: Complete a clinical response to the primary therapy. ≥ 12 months between the initial diagnosis and recurrence. Performance status ≤ 2. Attempted SCR. ≤ 5 recurrence sites within the abdomen or pelvis on preoperative imaging studies. Exclusion criteria: Women who underwent an interval debulking or second‐look procedure with findings of macroscopically positive disease. |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: Complete cytoreduction was achieved in 41 women (74.5%). 8 women (14.5%) had optimal cytoreduction (macroscopic disease with a maximal dimension < 1 cm). Comparison: 6 women (11%) had sub‐optimal cytoreduction (> 1 cm of residual disease). |

|

| Outcomes |