Abstract

Background

Despite the existence of effective interventions and best‐practice guideline recommendations for childcare services to implement policies, practices and programmes to promote child healthy eating, physical activity and prevent unhealthy weight gain, many services fail to do so.

Objectives

The primary aim of the review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies aimed at improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention. The secondary aims of the review were to:

1. describe the impact of such strategies on childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes; 2. describe the cost or cost‐effectiveness of such strategies; 3. describe any adverse effects of such strategies on childcare services, service staff or children; 4. examine the effect of such strategies on child diet, physical activity or weight status.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases on 3 August 2015: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process, EMBASE, PsycINFO, ERIC, CINAHL and SCOPUS. We also searched reference lists of included trials, handsearched two international implementation science journals and searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Selection criteria

We included any study (randomised or non‐randomised) with a parallel control group that compared any strategy to improve the implementation of a healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme by staff of centre‐based childcare services to no intervention, 'usual' practice or an alternative strategy.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors independently screened abstracts and titles, extracted trial data and assessed risk of bias in pairs; we resolved discrepancies via consensus. Heterogeneity across studies precluded pooling of data and undertaking quantitative assessment via meta‐analysis. However, we narratively synthesised the trial findings by describing the effect size of the primary outcome measure for policy or practice implementation (or the median of such measures where a single primary outcome was not stated).

Main results

We identified 10 trials as eligible and included them in the review. The trials sought to improve the implementation of policies and practices targeting healthy eating (two trials), physical activity (two trials) or both healthy eating and physical activity (six trials). Collectively the implementation strategies tested in the 10 trials included educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing. A total of 1053 childcare services participated across all trials. Of the 10 trials, eight examined implementation strategies versus a usual practice control and two compared alternative implementation strategies. There was considerable study heterogeneity. We judged all studies as having high risk of bias for at least one domain.

It is uncertain whether the strategies tested improved the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention. No intervention improved the implementation of all policies and practices targeted by the implementation strategies relative to a comparison group. Of the eight trials that compared an implementation strategy to usual practice or a no intervention control, however, seven reported improvements in the implementation of at least one of the targeted policies or practices relative to control. For these trials the effect on the primary implementation outcome was as follows: among the three trials that reported score‐based measures of implementation the scores ranged from 1 to 5.1; across four trials reporting the proportion of staff or services implementing a specific policy or practice this ranged from 0% to 9.5%; and in three trials reporting the time (per day or week) staff or services spent implementing a policy or practice this ranged from 4.3 minutes to 7.7 minutes. The review findings also indicate that is it uncertain whether such interventions improve childcare service staff knowledge or attitudes (two trials), child physical activity (two trials), child weight status (two trials) or child diet (one trial). None of the included trials reported on the cost or cost‐effectiveness of the intervention. One trial assessed the adverse effects of a physical activity intervention and found no difference in rates of child injury between groups. For all review outcomes, we rated the quality of the evidence as very low. The primary limitation of the review was the lack of conventional terminology in implementation science, which may have resulted in potentially relevant studies failing to be identified based on the search terms used in this review.

Authors' conclusions

Current research provides weak and inconsistent evidence of the effectiveness of such strategies in improving the implementation of policies and practices, childcare service staff knowledge or attitudes, or child diet, physical activity or weight status. Further research in the field is required.

Keywords: Child; Humans; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Motor Activity; Program Development; Child Care; Child Care/methods; Child Care/organization & administration; Child Day Care Centers; Diet; Diet/standards; Eating; Guidelines as Topic; Health Promotion; Health Promotion/methods; Health Promotion/organization & administration; Obesity; Obesity/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Improving the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes in childcare services

The review question This review aimed to look at the effects of strategies to improve the implementation (or correct undertaking) of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote children's healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention. We also looked at whether these strategies improved childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes. We also wanted to determine the cost or cost‐effectiveness of providing implementation support, whether support strategies were associated with any adverse effects and whether there was an impact on child nutrition, physical activity or weight status. Background A number of childcare service‐based interventions have been found to be effective in improving child diet, increasing child physical activity and preventing excessive weight gain. Despite the existence of such evidence and best‐practice guideline recommendations for childcare services to implement these policies and practices, many childcare services fail to do so. Without proper implementation, children will not benefit from these child health‐directed policies and practices. Study characteristics The review identified 10 trials, eight of which examined implementation strategies versus usual practice, and two that compared different types of implementation strategies. The trials sought to improve the implementation of policies and practices targeting healthy eating (two trials), physical activity (two trials) or both healthy eating and physical activity (six trials). Collectively the implementation strategies tested in the 10 trials included educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing. The strategies tested were only a small number of those that could be applied to improve implementation in this setting. Search date The evidence is current to August 2015. Key results None of the strategies identified in the review improved implementation of all the targeted policies or practices. However, most strategies reported improvement for at least one policy or practice. The findings provide weak and inconsistent evidence of the effects of these strategies on improving the implementation of policies, practices and programmes, childcare service staff knowledge or attitudes, or child diet, physical activity or weight status. The lack of consistent terminology in this area of research may have meant some relevant studies were not picked up in our search. Nonetheless, the few identified trials suggest that research to implement such policies and practices in childcare services is only in the early stages of development. Quality of the evidence We rated the evidence for all outcomes as very low quality and thus we cannot be overly confident in the findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

| Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services | |||

|

Patient or population: children up to the age of 6 years Settings: centre‐based childcare services that cater for children prior to compulsory schooling Intervention: any strategy (including educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, small incentives or grants, educational outreach visits or academic detailing) with the primary intent of improving the implementation (by usual service staff) of policies, practices or programmes in centre‐based childcare services to promote healthy eating, physical activity or prevent unhealthy weight gain Comparison: no intervention (8 studies) or alternate intervention (2 studies) | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention | We are uncertain whether strategies improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention | 1053 participants (childcare services), 10 studies | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

| Childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes related to the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity | We are uncertain whether strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention improve childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes | 457 participants (childcare service staff), 2 studies | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

| Cost or cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services | No studies were found that looked at the cost or cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services | Nil | N/A |

| Adverse consequences of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services | We are uncertain whether strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention impact on adverse consequences | 20 participants (childcare services), 1 study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb |

| Measures of child diet, physical activity or weight status | We are uncertain whether strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention improve child diet, physical activity or weight status | 2829 participants (children), 3 studies | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

aTriple downgraded due to limitations in the design, imprecision of evidence and unexplained heterogeneity. bTriple downgraded due to indirectness, inconsistency and imprecision of evidence.

Background

Description of the condition

Internationally, the prevalence of being overweight and obesity has increased across every region of the world in recent decades (Finucane 2011). Currently over 1.5 billion adults and 170 million children are overweight or obese (Finucane 2011; Lobstein 2004). While obesity rates in high‐income countries remain higher, prevalence rates in low‐ and middle‐income countries are accelerating (Swinburn 2011). In Africa, for example, the prevalence of being overweight among children under five years is expected to increase from 4% in 1990 to 11% by 2025 (Black 2013). Excessive weight gain increases the risk of a variety of chronic health conditions. Between the years 2010 and 2030, up to 8.5 million cases of diabetes, 7.3 million cases of heart disease and stroke, and 669,000 cases of cancer attributable to obesity have been projected in the USA and UK alone (Wang 2011). In Australia, between the years 2011 and 2050, 1.75 million lives and over 10 million premature years of life will be lost due to excessive weight gain (Gray 2009).

Description of the intervention

Physical inactivity and poor diet are key drivers of excessive weight gain. As excessive weight gain in childhood tracks into adulthood, interventions targeting children's diet and physical activity have been recommended to mitigate the adverse health effects of obesity on the population (World Health Organization 2012). A recently published World Health Organization report into population‐based approaches to childhood obesity prevention identified centre‐based childcare services (including preschools, long daycare services and kindergartens that provide educational and developmental activities for children prior to formal compulsory schooling) as an important setting for public health action to reduce the risk of unhealthy weight gain in childhood. Such settings provide an opportunity to access large numbers of children for prolonged periods of time (World Health Organization 2012). Further, randomised and quasi‐experimental trials have identified a number of interventions, delivered in childcare services, which have increased child physical activity and fundamental movement skill proficiency, improved child diet quality and prevented excessive weight gain (Adams 2009; De Silva‐Sanigorski 2010; Hardy 2010; Trost 2008). As such, regulations and best practice guidelines for the childcare sector recommend implementation of a number of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices, such as restricting sedentary screen time opportunities; ensuring meals provided by childcare services or foods packed by parents for consumption in care are consistent with dietary guidelines; and the provision of programmes to promote physical activity and fundamental movement skill development (Commonwealth of Australia; McWilliams 2009; Tremblay 2012).

Despite the existence of evidenced‐based best‐practice guidelines for childcare services, implementation of obesity prevention policies and practices that are consistent with such guidelines is poor (McWilliams 2009; Story 2006). In the USA, research suggests that 75% of meat consumed in childcare is fried or high in fat, and that children consume less than 13% of dietary guideline recommendations for whole grains and 7% for dark vegetables (Ball 2008). Childcare service adherence to dietary guidelines in other countries has also been reported to be poor (Yoong 2014). Similarly, adherence to best‐practice recommendations for physical activity is also suboptimal. For example, only 14% of USA childcare services provided 120 minutes of active play per day, 57% to 60% did not have a written physical activity policy (McWilliams 2009; Sisson 2012), and in 18% of childcare services, children were seated for more than 30 minutes at a time (McWilliams 2009). In Australia, it has been reported that just 48% to 50% of centre‐based childcare services had a written physical activity policy, 46% to 60% had programmed time each day for fundamental movement skill development (Wolfenden 2010), and 60% of child lunch boxes contained more than one serving of high‐fat, salt or sugar foods or drinks (Kelly 2010).

Without adequate implementation across the population of childcare services, the potential public health benefits of initiatives to improve child diet or physical activity, or prevent obesity, will not be fully realised. 'Implementation' is described as the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence‐based health interventions and to change practice patterns within specific settings (Glasgow 2012). Implementation research, specifically, is the study of strategies designed to integrate health policies, practices or programmes within specific settings (for example, primary care, community centres or childcare services) (Schillinger 2010). The National Institutes of Health recognises implementation research as a fundamental component of the third stage of the research translation process ('T3') and that it is a necessary pre‐requisite for research to yield public health improvements (Glasgow 2012). While staff of centre‐based childcare services are responsible for providing educational experiences and an environment supportive of healthy growth and development, including initiatives designed to reduce the risk of excessive weight gain, it may be the childcare services themselves, government or other agencies (such as for licensing and accreditation requirements) that undertake strategies aimed at enhancing the implementation of such initiatives.

There are a range of potential strategies that can improve the likelihood of implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies and practices in childcare services. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy is a framework for characterising educational, behavioural, financial, regulatory and organisational interventions (EPOC 2015); it includes three categories with 22 subcategories within the topic of 'implementation strategies'. Examples of such subcategories include continuous quality improvement, educational materials, performance monitoring, local consensus processes and educational outreach visits (EPOC 2015).

How the intervention might work

The determinants of policy and practice implementation are complex and the mechanisms by which support strategies facilitate implementation are not well understood. Implementation frameworks have identified a large number of factors operating at multiple macro and micro levels that can influence the success of implementation (Damschroder 2009). However, few studies have been conducted in the childcare setting to identify key determinants of implementation in this setting. A study by Wolfenden and colleagues of over 200 childcare services in Australia examined associations between the existence of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices and 13 factors suggested by Damschroder's Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to impede or promote implementation (Wolfenden 2015a). The study reported that implementation policy and practice implementation was more likely when service managers, management committee and parents were supportive, and where external resources to support implementation were accessible. Applied implementation frameworks, such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (Michie 2008), suggest that strategies to facilitate implementation may be most likely to be effective with a thorough understanding of implementation context and barriers, and when theoretical frameworks are applied to select implementation support strategies to address key determinants of implementation. For example, knowledge barriers to implementation may be best overcome with education meetings or materials, while activity reminders, such as decision support systems, may be particularly important in instances where staff forgetfulness is identified as a local implementation barrier.

Why it is important to do this review

A number of large systematic reviews have been undertaken to assess the effectiveness of such implementation strategies in improving the professional practice of clinicians. For example Ivers and colleagues reviewed the effectiveness of audit and feedback on the behaviour of health professionals and the health of their patients and found it generally resulted in small but important improvements in professional practice (Ivers 2012). Giguère and colleagues reviewed the effectiveness of printed education materials on the practice of healthcare professionals and patient health outcomes and found a small beneficial effect on professional practice outcomes (Giguère 2012). Additional systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of additional implementation strategies including reminders (Arditi 2012), education meetings and workshops (Forsetlund 2009; O'Brien 2007), and incentives (Scott 2011). Despite the existence of such reviews, implementation research in non‐clinical community settings remains limited (Buller 2010). While several implementation strategies have been used to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies and practices in childcare services (Finch 2012; Ward 2008), a systematic synthesis of the effects reported in such trials has not been undertaken in this setting.

To our knowledge, just one systematic review of implementation interventions in non‐clinical settings (for example, schools) has been published to date (Rabin 2010). The review, which was an update of an earlier Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality report (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2003), investigated the effectiveness of strategies in any community setting to implement policies or practices to reduce behavioural risks for cancer, including healthy eating, physical activity, smoking and sun protection. The review included studies published between 1980 and 2008 and did not identify any implementation trials targeting healthy eating or physical activity in childcare services. An up‐to‐date, comprehensive review of such literature is therefore warranted.

Objectives

The primary aim of the review was to examine the effectiveness of strategies aimed at improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by childcare services that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention.

The secondary aims of the review were to:

describe the impact of such strategies on childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes;

describe the cost or cost‐effectiveness of such strategies;

describe any adverse effects of such strategies on childcare services, service staff or children;

examine the effect of such strategies on child diet, physical activity or weight status.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any study (randomised, including cluster‐randomised, or non‐randomised trials) with a parallel control group that compared:

a strategy to improve the implementation of any healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme in centre‐based childcare services compared with no intervention or 'usual' practice;

two or more alternative strategies to improve the implementation of any healthy eating, physical activity or obesity prevention policy, practice or programme in centre‐based childcare services.

We excluded studies that did not include implementation of policy, practices or programmes as a specific aim (primary or secondary), as well as studies that did not report baseline measures of the primary outcome. There was no restriction on the length of the study follow‐up period, language of publication or country of origin.

Types of participants

Centre‐based childcare services such as preschools, nurseries, long daycare services and kindergartens that cater for children prior to compulsory schooling (typically up to the age of five to six years). We excluded studies of childcare services provided in the home.

Types of interventions

Any strategy with the primary intent of improving the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in centre‐based childcare services to promote healthy eating, physical activity or prevent unhealthy weight gain was eligible. To be eligible strategies must have sought to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes by usual childcare service staff. Strategies could have included quality improvement initiatives, education and training, performance feedback, prompts and reminders, implementation resources, financial incentives, penalties, communication and social marketing strategies, professional networking, the use of opinion leaders or implementation consensus processes. Interventions may have been singular or multi‐component.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We included any measure of either the completeness or the quality of the implementation of childcare service policies, practices or programmes (for example, the percentage of childcare services implementing a food service consistent with dietary guidelines or the mean number of physical activity practices implemented). To assess the review outcomes, data may have been collected from a variety of sources including teachers, managers, cooks or other staff of centre‐based childcare services; or administrators, officials or other health, education, government or non‐government personnel responsible for encouraging or enforcing the implementation of health‐promoting initiatives in childcare services. Such data may have been obtained from audits of service records, questionnaires or surveys of staff, service managers, other personnel or parents; direct observation or recordings; examination of routine information collected from government departments (such as compliance with food standards or breaches of childcare service regulations) or other sources. Additionally, children, parents or childcare service staff may have provided information regarding child diet, physical activity or child weight status.

Secondary outcomes

Any measure of childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes related to the implementation of policies, practices or programmes that promote child healthy eating, physical activity and/or obesity prevention.

Estimates of absolute costs or any assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of strategies to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services.

Any reported adverse consequences of a strategy to improve the implementation of policies, practices or programmes in childcare services. This could include impacts on child health (for example, an increase in child injury following the implementation of physical activity‐promoting practices) or development, service operation or staff attitudes (for example, impacts on staff motivation or cohesion) or the displacement of other key programmes, curricula or practices.

Any measure of child diet, physical activity (including sedentary behaviours) or weight status. Such measures could be derived from any data source including direct observation, questionnaire, or anthropometric or biochemical assessments. We excluded studies focusing on malnutrition/malnourishment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted searches for peer‐reviewed articles in electronic databases. We also undertook handsearching of relevant journals and the reference lists of included trials.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 7), MEDLINE (1950 to 2015), MEDLINE In Process (up to 2015), EMBASE (1947 to 2015), PsycINFO (1950 to 2015), ERIC (up to 2015), CINAHL (up to 2015) and SCOPUS (up to 2015).

We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for the other databases and we included filters used in other systematic reviews for population (childcare services) (Zoritch 2000), physical activity (Dobbins 2013), healthy eating (Jaime 2009), and obesity (Waters 2011). A search filter for intervention type (implementation interventions) was based on previous reviews (Rabin 2010), and a glossary of terms in implementation and dissemination research (Rabin 2008). See Appendix 1 for the detailed search strategy.

An experienced librarian (DB) searched the electronic databases.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all included trials for citation of other potentially relevant trials. We conducted handsearches of all publications for the past five years in the journal Implementation Science and the Journal of Translational Behavioural Medicine as they are the leading implementation journals in the field. We also performed handsearches of the reference lists of included trials. Furthermore, we conducted searches of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov). We included studies identified in such searches, which have not yet been published, in the 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' table. We also made contact with the authors of included trials, experts in the field of implementation science and key organisations to identify any relevant ongoing or unpublished trials or grey literature publications.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (from pool of six authors: JJ, LW, CMW, AJW, KS and SLY) independently screened abstracts and titles. Review authors were not blind to the author or journal information. We conducted the screening of studies using a standardised screening tool developed based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), which we piloted before use. We obtained the full texts of manuscripts for all potentially eligible trials for further examination. For all manuscripts, we recorded information regarding the primary reason for exclusion and documented this in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We included the remaining eligible trials in the review. We resolved discrepancies between review authors regarding study eligibility by consensus. In instances where the study eligibility could not be resolved via consensus, a third review author made a decision.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from pool of five authors: JJ, MF, RW, FT, TS), unblinded to author or journal information, independently extracted information from the included trials. We recorded the information extracted from the included trials in a data extraction form that we developed based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Public Health Group Guide for Developing a Cochrane Protocol (Cochrane Public Health Group 2011). We piloted the data extraction form before the initiation of the review. We resolved discrepancies between review authors regarding data extraction by consensus and, where required, via a third review author.

We extracted the following information:

Study eligibility as well as the study design, date of publication, childcare service type, country, participant/service demographic/socioeconomic characteristics and number of experimental conditions, as well as information to allow assessment of study risk of bias.

Characteristics of the implementation strategy, including the duration, number of contacts and approaches to implementation, the theoretical underpinning of the strategy (if noted in the study), information to allow classification against the EPOC taxonomy, and to enable an assessment of the overall quality of evidence using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as well as data describing consistency of the execution of the intervention with a planned delivery protocol.

Trial primary and secondary outcomes, including the data collection method, validity of measures used, effect size and measures of outcome variability.

Source(s) of research funding and potential conflicts of interest.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Overall risk of bias

Two review authors (MK and FT) assessed risk of bias independently using the 'Risk of bias' tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We provided an overall risk of bias ('high', 'low' or 'unclear') for each included study based on consideration of study methodological characteristics (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and 'other' potential sources of bias). Where required, a third review author adjudicated discrepancies regarding the risk of bias that could not be resolved via consensus. We included an additional criterion 'potential confounding' for the assessment of the risk of bias in non‐randomised trial designs (Higgins 2011). We also included additional criteria for cluster‐randomised controlled trials including 'recruitment to cluster', 'baseline imbalance', 'loss of clusters', 'incorrect analysis' and 'compatibility with individually randomised controlled trials' (Higgins 2011). We documented the risk of bias of the included studies in 'Risk of bias' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

Differences in measures and the primary and secondary outcomes reported in the included studies precluded the use of summary statistics to describe treatment effects. As such, the methods and outcomes of the included trials are comprehensively described in narrative form according to broad implementation strategy characteristics.

Unit of analysis issues

Clustered studies

We examined clustered trials for unit of analysis errors. We identified trials with unit of analysis errors in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of included trials to provide additional information if any outcome data were unclear or missing. All information we received was included in the results of the review. We noted any instances of potential selective or incomplete reporting of outcome data in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We were unable to perform an assessment of heterogeneity due to considerable variability in terms of study interventions, outcomes, measures and comparators. Therefore we were unable to explore heterogeneity via box plots, forest plots and/or the I2statistic (Higgins 2011). Instead the potential implications of trial heterogeneity are outlined in the Discussion.

Assessment of reporting biases

The comprehensive search strategy for this review helped to reduce the risk of reporting bias. We also conducted comparisons between published reports and trial protocols, and trial registers where such reports were available. Instances of potential reporting bias are documented in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Data synthesis

We narratively synthesised trial findings according to the implementation strategies employed and the outcome measures reported. We used the EPOC taxonomy to classify implementation strategies (EPOC 2015). As the trial heterogeneity precluded meta‐analysis we described the effects of interventions by reporting the absolute effect size of the primary outcome measure for policy or practice implementation for each study. We calculated the effect size by subtracting the change from baseline on the primary implementation outcome for the control or comparison group from the change from baseline in the experimental or intervention group. If data to enable calculation of the change from baseline were unavailable, we used the differences between groups post‐intervention. Where there were two or more primary implementation outcome measures, we used the median effect size of the primary outcomes. Where the primary outcome measure was not explicitly identified by the study authors in the published manuscripts we used the implementation outcome on which the trial sample size calculation was based or, in its absence, we took the median effect size of all measures of policy or practice outcomes reported in the manuscript. Such an approach was previously used in the Cochrane Review of the effects of audit and feedback on professional practices published by the Cochrane EPOC Group (Ivers 2012). In instances where a number of subscales of an overall implementation score were reported in addition to a total scale score, we used the total score as the primary outcome to provide a more comprehensive measure of implementation. We reverse scored implementation measures that did not represent an improvement (for example, the proportion of services without a nutrition policy). We present the effects of interventions according to the implementation strategies (classified using the EPOC taxonomy) employed by included studies and, within such grouping, based on the outcome data (continuous or dichotomous) reported.

We included a 'Summary of findings' table to present the key findings of the review (Table 1). We generated the table based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the EPOC Group and included i) a list of all primary and secondary outcomes in the review, ii) a description of intervention effect, iii) the number of participants and studies addressing each outcome, and iv) a grade for the overall quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. In particular, the table provides key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

Two review authors (LW and JJ) rated the overall quality of evidence for each outcome using the GRADE system (Guyatt 2010), with any disagreements resolved via consensus or, where required, by a third review author. The GRADE system defines the quality of the body of evidence for each review outcome regarding the extent to which one can be confident in the review findings. The GRADE system required an assessment of methodological quality, directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias. We used the GRADE quality ratings (from 'very low' to 'high') to describe the quality of the body of evidence for each review outcome and we included these in 'Table 1'.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Data were insufficient to conduct subgroup analysis or enable quantitative exploration of heterogeneity. Nonetheless clinical and methodological heterogeneity of included studies is described narratively. To describe the impact of implementation strategies delivered 'at scale' (defined as involving 50 or more childcare services) we performed subgroup analyses narratively for the primary implementation outcomes. Specifically we performed subgroup analyses where included studies sought to improve implementation of policies, practices or programmes across 50 or more services.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform sensitivity analysis by removing studies with a high risk of bias or by removing outliers contributing to statistical heterogeneity as marked heterogeneity precluded pooled analysis.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

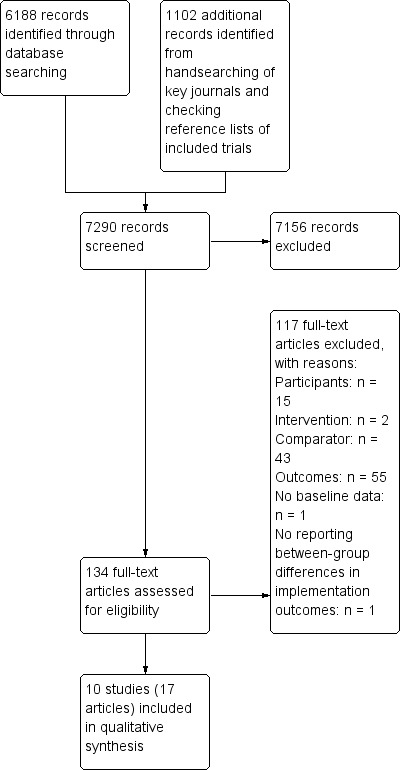

The electronic search, conducted on 3 August 2015, yielded 6188 citations (Figure 1). We identified an additional 1102 records from handsearching key journals and checking reference lists of included trials. We identified no additional records through our contact with the authors of included trials, experts in the field of implementation science and key organisations. Following screening of titles and abstracts, we obtained the full texts of 134 manuscripts for further review, of which we included 17 manuscripts describing 10 individual trials. We contacted the authors of five included trials to provide additional information where any outcome data were unclear or missing. All authors responded and the information we received was included in the results of the review. We identified four studies as ongoing studies that have not yet been published through searches of clinical trial registration databases.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Types of studies

The trials were predominantly conducted in the USA (n = 5) (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Gosliner 2010; Ward 2008; Williams 2002), and Australia (n = 4) (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), but also included a study from Ireland (n = 1) (Johnston Molloy 2013). Studies were conducted between 1995 and 2012, although two studies did not report the years of data collection (Benjamin 2007; Gosliner 2010). There was considerable heterogeneity in the participants, interventions and outcomes (clinical heterogeneity), and the study design characteristics (methodological) of included studies.

Participants

Of the 10 included trials, seven recruited childcare services located in disadvantaged areas or specifically serving disadvantaged low‐income or minority children (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Williams 2002). The socio‐economic characteristics of the service locality or the children attending was not described in the remaining three trials. There was considerable variability in the number of participating childcare services in the included studies. The largest trial recruited 583 preschools (Bell 2014). However, most trials recruited 20 or fewer childcare services (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Williams 2002), with the smallest trial recruiting just nine services. Three trials sought to improve implementation of policies, practices or programmes in 50 or more services (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Ward 2008). Six of the 10 included trials were conducted by two research groups in the USA and Australia and all were conducted in high‐income countries (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Ward 2008).

Interventions

Two trials targeted the implementation of healthy eating policies or practices only (Bell 2014; Williams 2002), two targeted the implementation of physical activity policies and practices only (Finch 2012; Finch 2014), and six targeted both healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008). All trials used multiple implementation strategies. The strategies tested examined only a small number of those described in the EPOC taxonomy that could be applied to improve implementation in the setting. The definitions of each of the EPOC subcategories used to classify implementation strategies employed by studies included in the review are provided in Table 2. Using the EPOC taxonomy descriptors, all trials included educational meetings and educational materials (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008; Williams 2002). One trial utilised these strategies with the addition of audit and feedback (Johnston Molloy 2013). Three trials combined educational meetings and educational materials with educational outreach visits or academic detailing (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Ward 2008), and three trials utilised these strategies with the addition of small incentives of financial grants not otherwise specified (Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Williams 2002). Two studies tested an intervention consisting of educational meetings and educational materials with audit and feedback, the use of opinion leaders and small incentives (Bell 2014; Finch 2012), and one study tested the impact of an implementation strategy comprising educational meetings and educational materials, academic detailing, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives (Finch 2014). Four studies reported that strategies to support implementation were theoretically based (Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Ward 2008), and the theories adopted included components of social cognitive theory against a social‐ecologic framework (Benjamin 2007; Ward 2008), practice change and capacity building theoretical frameworks (Bell 2014), and social‐ecological models of health behaviour change (Finch 2014).

Table 1.

Definition of EPOC subcategories utilised in the review

| EPOC subcategory | Definition |

| Educational materials | Distribution to individuals, or groups, of educational materials to support clinical care, i.e. any intervention in which knowledge is distributed. For example, this may be facilitated by the internet, learning critical appraisal skills; skills for electronic retrieval of information, diagnostic formulation; question formulation |

| Educational meetings | Courses, workshops, conferences or other educational meetings |

| Educational outreach visits or academic detailing | Personal visits by a trained person to health workers in their own settings, to provide information with the aim of changing practice |

| Small incentives or grants | Transfer of money or material goods to healthcare providers conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a predetermined performance target, for example incentives for lay health workers |

| Audit and feedback | A summary of health workers’ performance over a specified period of time, given to them in a written, electronic or verbal format; the summary may include recommendations for clinical action |

| Opinion leaders | The identification and use of identifiable local opinion leaders to promote good clinical practice |

Outcomes

Implementation was primarily assessed using telephone interview, surveys/questionnaires completed by childcare service staff or audits of service documents conducted by researchers (Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Williams 2002), or by direct observation (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008). The validity of four of the five trials utilising a survey/questionnaire to assess implementation was not reported (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010). In one trial outcome assessments were conducted immediately post‐intervention, and one and four months post‐intervention (Benjamin 2007), while the remaining studies included follow‐up ranging from up to five to six months (Hardy 2010), 22 months (Bell 2014), or four years after initiation of the intervention (Johnston Molloy 2013). Three trials reported outcomes of both implementation and a measure of child healthy eating, physical activity or weight status (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Williams 2002), two trials included measures of childcare service staff knowledge, skills or attitudes (Finch 2012; Hardy 2010), one trial included a measure of potential adverse effects (Finch 2014), and none reported costs or cost‐effectiveness analyses.

Study design characteristics

Seven of the included studies were randomised trials (or cluster‐randomised trials) (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008), and three were non‐randomised trials with a parallel control group (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Williams 2002).

Eight trials compared an implementation strategy to usual practice or a no intervention control (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010; Ward 2008; Williams 2002). Two trials directly compared two different implementation strategies (Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013). Four studies utilised a convenience sample of childcare services (JAlkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008). Four trials attempted to recruit all eligible services in the study region (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Hardy 2010), or randomly approached services within a study region to participate (Finch 2014), the service level participation rate of such studies ranging from 48% (Hardy 2010) to 91% (Bell 2014). The sampling procedures of two trials were unclear (Gosliner 2010; Williams 2002).

We judged implementation to be the primary outcome in seven trials (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Gosliner 2010; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008), and a secondary outcome in the remaining three trials (Finch 2014; Hardy 2010; Williams 2002), based on the stated aims of the trial. A variety of outcome measures were employed by the included studies. Seven trials included continuous measures of implementation outcomes including policy or environment scores (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008), minutes of policy or programme implementation (Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), frequency of policy or programme implementation (Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), or quantity of food or beverages or macronutrients provided to children (Bell 2014; Williams 2002). Six trials reported a dichotomous measure of implementation, including the percentage of staff or childcare services that implemented a policy, practice or programme (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010). Assessment of implementation included observation of childcare environments (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013; Ward 2008), audits of menus (Bell 2014; Williams 2002), or telephone interviews or surveys/questionnaires completed by staff of childcare services (Bell 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2012; Gosliner 2010; Hardy 2010) (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of intervention, measures and absolute intervention effect size in included studies

| Study | Implementation strategies | Comparison group | Primary implementation outcome measures | Effect sizea |

| Alkon 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings and audit and feedback | Usual practice |

Score: nutrition and physical activity policy quality using the CHPHSPC and nutrition and physical activity practices using the EPAO assessed via observation (5 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: foods offered to children assessed using the DOCC tool assessed via observation (10 measures) |

Median (range)d: 1.4 (0 to 4.29) Median (range): 0% (0% to 25%)c |

| Bell 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders, and small incentives or grants | Usual practice |

% of staff or services implementing a practice: percentage of services implementing nutrition policies and practices and menus consistent with nutrition recommendations (10 measures) Quantity of food served (servings/items): mean number of items or servings of healthy/unhealthy foods on service menus (4 measures) |

Median (range): 9.5% (2% to 36%) Median (range): 0.5 serves/items (‐0.4 to 0.8) |

| Benjamin 2007 | Educational materials, educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Usual practice | Score: nutrition, physical activity environments assessed via questionnaire (NAPSACC) completed by service managers (total score) | Mean difference (95% CI)d: 5.10 (‐2.80 to 13.00) |

| Finch 2012 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives | Usual practice |

% of staff or services implementing a practice: percentage of services implementing physical activity policies and practices (11 measures) Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice: time (hours/day) spent on structured physical activities (1 measure) |

Median (range): 2.5% (‐4% to 41%) Mean: 6 minutes |

| Finch 2014 | Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives | Usual practice |

Frequency of staff or service implementation of a practice: occasions of implementation of fundamental movement skill activities, staff role modelling and verbal prompts and positive comments (4 measures) Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice (per session or day): minutes of fundamental movement skill activities, structured time, television viewing or seated time (4 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: services with seated time > 30 minutes or with an activity policy (2 measures) Mean number of resources or equipment per service: (3 measures) |

Median (range): 2.6 (12.1 to 0.6) Median (range)d: 4.3 minutes (‐12 minutes to 39 minutes) Median (range): 5 (30 to ‐20) Median (range): ‐01 (‐0.6 to ‐0.1) |

| Gosliner 2010 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants with staff wellness programme | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing | % of staff or services implementing a practice: Provision of food items by staff 'more often' assessed via staff completed questionnaire (8 measures) | Median (range): 17% (0% to 23%) |

| Hardy 2010 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants | Usual practice |

Minutes of service or staff implementation of a policy of practice: Minutes (per week or session) of structured and unstructured play or fundamental movement skills activities (3 measures) Frequency of staff or service implementation of a practice: Frequency (per week or day) of structured or unstructured play, and of fundamental movement skill activities (3 measures) % of staff or services implementing a practice: conduct of food based activities, development of new rules around food and drink bought from home, and the provision of health information to families (3 measures) |

Median (range): 7.7 minutes (6.5 minutes to 10.1 minutes) Median (range): 0.2 (‐0.9 to 1.9) Median (range)d: 11% (‐7% to 31%) |

| Johnston Molloy 2013 | Educational materials, manager and staff educational meetings and audit and feedback | Educational materials, manager educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Score: On the Health Promotion Evaluation Activity Scored Evaluation form assessed via observation (total score) | Difference in median score: ‐2b |

| Ward 2008 | Educational materials, educational meetings, and audit and feedback | Usual practice | Score: nutrition and physical activity practices using the EPAO assessed via observation (total score) | Mean difference (95% CI)d: 1.01 (0.18 to 1.84) |

| Williams 2002 | Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants | Usual practice | Quantity of food served (servings/grams): Primary outcome – grams of saturated fat assessed via menu audit (one measure) | Median (range): 17% (0% to 23%) |

aEffect size calculated first using the primary outcome (where a single primary outcome was reported); otherwise using a total score (when total and subscale scores were provided); otherwise using the median effect size across measures (where more than one outcome measure was reported and not specified as primary).

bMean not reported. Represents the difference in median score between manager and staff trained versus manager only trained group.

cEffect size of measures reported as non‐significant (but where data are not reported in manuscript) assumed to be '0'.

dAdditional data obtained from study authors where unclear or missing.

CHPHSPC: Californian Childcare Health Programme Health and Safety Checklist; DOCC: Diet Observation in Child Care; EPAO: Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation; NAPSACC: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self‐Assessment for Child Care

Excluded studies

Following screening of titles and abstracts, we obtained the full texts of 134 manuscripts for further review for study eligibility (Figure 1). Of these, we considered 115 studies ineligible following the trial screening process (reasons for exclusion included: participants n = 15; intervention n = 2; comparator n = 43; outcomes n = 55). We excluded a study based on 'inappropriate outcomes' if it did not report implementation outcomes, if it did not report implementation outcomes for both intervention and control groups and if it did not report between‐group differences in implementation outcomes. We excluded an additional study following the commencement of data extraction as it did not report between‐group differences in implementation outcomes (Korwanich 2008). A further two studies did not collect baseline data (De Silva‐Sanigorski 2012; Gosliner 2010). We retained one of these studies as it was a randomised trial and therefore the examination of post‐intervention differences between groups was considered to be valid (Gosliner 2010).

Risk of bias in included studies

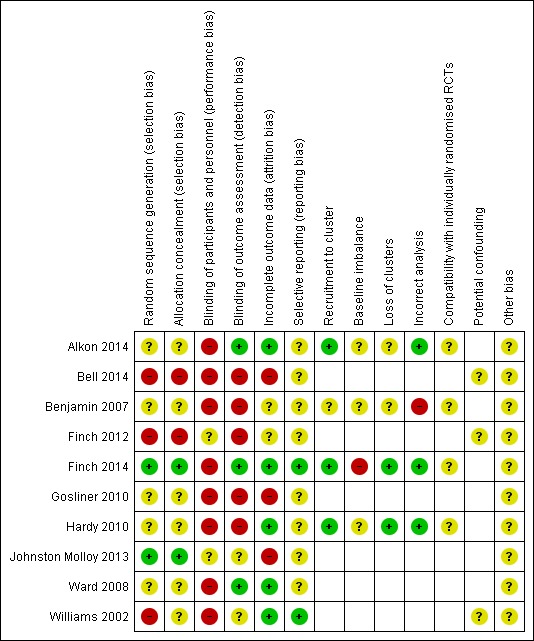

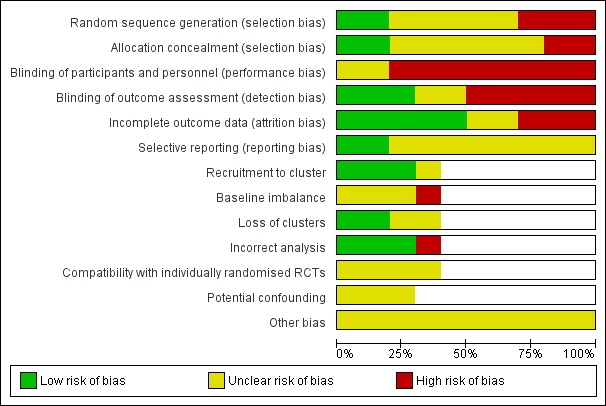

See Characteristics of included studies. The level of risk of bias is presented separately for each study in Figure 2 and as a combined study assessment of risk of bias in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Figure 3.

'Risk of bias graph': review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Risk of selection bias differed across studies. Only two of the studies were low risk as computerised random number functions and tables were used to generate random sequences and allocation was undertaken automatically in a single batch, preventing allocation from being pre‐empted (Finch 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013). For the three studies with quasi‐experimental, non‐randomised designs, the risk of selection bias was high (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Williams 2002). For the remaining five studies, such bias was unclear as these studies did not report on random sequence generation or concealment of allocation.

Blinding

For the majority of studies (n = 8), the risk of performance bias was high due to participants and research personnel not being blind to group allocation. For the remaining two studies the risk of performance bias was unclear as in both studies the control group also received some form of intervention (Finch 2012; Johnston Molloy 2013). Detection bias differed across studies based on whether outcome measures were objective (e.g. body mass index (BMI)) (low risk) or self‐reported (high risk), and whether research personnel were blind to group allocation when conducting outcome assessment (low risk). For three studies, the risk of detection bias was low for all outcomes included in this review (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Ward 2008). For the remainder of the studies (n = 7), the risk of detection bias was high, low or unclear across one or more outcome measures.

Incomplete outcome data

For half the studies (n = 5), the risk of attrition bias was low as either all or most participating services were followed up and/or sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of missing data. For two studies the risk of such bias was high due to a large difference in the proportion of participating services lost to follow‐up between groups (Bell 2014; Johnston Molloy 2013). Risk of attrition bias was also high for the study conducted by Gosliner and colleagues (Gosliner 2010), as participants who did not complete the intervention were excluded from the analysis. For the remaining studies the risk of attrition bias was unclear as it was unclear whether incomplete outcome data had been addressed adequately.

Selective reporting

For the majority of the studies (n = 8) a published protocol paper or trial registration record was not identified and therefore it was unclear whether reporting bias had occurred. For the remaining two studies the risk of reporting bias was low as protocol papers were available and all a priori determined outcomes were reported (Finch 2014; Williams 2002).

Other potential sources of bias

For the four studies that were cluster‐randomised controlled trials, we assessed the potential risk of additional biases (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010).

For the potential risk of recruitment (to cluster) bias, three of these studies were low risk as either a random, quasi‐random or census approach was used for recruitment (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010).

Regarding risk of bias due to baseline imbalances, three studies were at unclear risk (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Hardy 2010), while one study was at high risk due to baseline imbalances in service characteristics, with no mention of adjustments within the analysis (Finch 2014).

Two studies were low risk for loss of clusters as either all children were followed up or there was no loss of clusters (Finch 2014; Hardy 2010).

For incorrect analysis, three studies were low risk (Alkon 2014; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010), while the remaining study was high risk as no statistical analysis was undertaken due to the small sample size (Benjamin 2007).

All four cluster‐randomised controlled trials were at unclear risk for compatibility with individually randomised controlled trials as we were unable to determine whether a herd effect existed (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010).

For the three studies with quasi‐experimental, non‐randomised designs (Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Williams 2002), we also considered the potential risk of bias due to confounding factors. For all three studies it was unclear whether confounders were adequately adjusted for.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Most studies reported improvement in at least one of the policies or practices targeted by the implementation support strategy. Of the eight trials that compared an implementation strategy to usual practice or a no intervention control, seven reported statistically significant improvements in the implementation of at least one of the targeted policies or practices relative to control (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010; Ward 2008; Williams 2002). For trials comparing implementation strategies against a non‐intervention or usual practice control, the absolute effect of the primary implementation outcome was as follows: among the three trials that reported score‐based measures of implementation the scores ranged from 1 to 5.1 (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Ward 2008); across four trials reporting the proportion of staff or services implementing a specific policy or practice this ranged from 0% to 9.5% (Alkon 2014; Bell 2014; Finch 2012; Finch 2014; Hardy 2010); and in three trials reporting the time (per day or week) staff or services spent implementing a policy or practice this was 4.3 minutes to 7.7 minutes (Table 3). Two trials reported comparing two different implementation strategies: the first reported no significant improvement on any measure of implementation (Johnston Molloy 2013), while the second reported significant improvements in two of the eight implementation outcomes reported (Gosliner 2010).

The effects of interventions are presented according to the implementation strategies (classified using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group taxonomy) employed by included studies and, within such grouping, based on the outcome data (continuous or dichotomous) reported.

Primary outcome

1. Education materials, manager and staff educational meetings, and audit and feedback versus educational materials, manager educational meetings, and audit and feedback

Continuous outcomes

Johnston Molloy and colleagues conducted a randomised, parallel‐group trial testing two training‐based interventions to improve implementation of nutrition and health‐related activity practices in Irish full daycare services (preschools) (Johnston Molloy 2013). Services were randomised to a 'manager and staff trained' group (n = 31) or a 'manager trained' only group (n = 30). Eighteen services in the 'manager and staff training' group and 24 in the 'manager trained' group provided follow‐up data and were included in the main analysis. There was no single primary implementation outcome reported in the trial, however the total Preschool Health Promotion Activity Scored Evaluation score did not differ significantly between groups (absolute difference in median scores between 'manager and staff trained' versus 'manager trained' only group = ‐2), with median total scores improving from 15 to 34 in the 'manager and staff trained group' and 13 to 34 in the 'manager trained' only group (P = 0.84). Similarly, there were no significant between‐group differences on any of the four subscale measures of nutrition environment, food service, meals or snacks.

2. Educational materials, educational meetings and educational outreach visits or academic detailing versus usual practice control

Continuous outcomes

Three trials assessed the impact of implementation strategies using self‐assessment or observational assessment scores of the childcare environment, or childcare policies and practices (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Ward 2008). All trials assessed the effects of implementation strategies consisting of educational materials, education meetings and educational outreach visits or academic detailing (Alkon 2014; Benjamin 2007; Ward 2008). The absolute effect size for the primary implementation outcome (based on a total scale score where provided, or the median absolute effect size where multiple implementation outcomes are reported) ranged from 1 for the implementation strategies tested by Ward and colleagues and assessed via researcher observation of childcare environment (Ward 2008), to a 5.09 point improvement in Nutrition and Physical Activity Self‐Assessment for Child Care (NAPSACC) self‐assessment score among services receiving implementation support in a trial by Benjamin and colleagues (Benjamin 2007).

All three studies, Alkon 2014, Benjamin 2007 and Ward 2008, assessed the effectiveness of implementation of the NAPSACC programme (Ammerman 2007). The first was a randomised pilot study to assess the feasibility, acceptability and impact of the programme, which targeted implementation of 15 key service nutrition and physical activity policies and practices (Benjamin 2007). A convenience sample of eight counties in North Carolina, USA were randomised to an intervention group or control (six intervention counties and two control). Between two and five childcare services were approached per county and 15 services in the intervention and four in the control region participated. Implementation support was delivered by childcare health consultants (typically registered nurses) who were provided a NAPSACC tool kit and resources. Changes in policy and practice implementation were re‐assessed using the NAPSACC self‐assessment survey completed by service managers immediately following the six‐month intervention. At follow‐up, two intervention services had withdrawn and one had closed. The trial found no significant change in the NAPSACC self‐assessment survey score completed by service managers in the intervention relative to the control group between baseline and immediately post‐intervention (mean difference (MD) 5.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐2.80 to 13.00, P = 0.21) (Benjamin 2007).

The second evaluation of the NAPSACC programme utilised a randomised controlled trial design (Ward 2008). A convenience sample of 30 childcare health consultants in North Carolina were randomised to an intervention (n = 20) or delayed intervention control group (n = 10). A convenience sample of 84 licensed childcare services associated with participating health consultants were then recruited. The primary trial outcome (change in nutrition and physical activity environment score) data were collected at baseline and immediately following the six‐month intervention using the Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation (EPAO) tool. There were significant improvements in total EPAO score among services receiving implementation support (MD 1.01, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.84, P = 0.02). There were no significant differences between groups at follow‐up for either the nutrition (MD 0.90, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.61, P = 0.06) or physical activity (MD 1.15, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 2.51, P = 0.19) environment subscales.

In the third study, Alkon and colleagues reported the findings of a randomised controlled trial of the NAPSACC programme conducted in 17 childcare services serving predominantly low‐income families (Alkon 2014). Nutrition and physical activity policies were evaluated by a research assistant using the California Childcare Health Program Health and Safety Policy Checklist (CCHPHSPC), while a modified version of the EPAO tool was completed by a research assistant to assess nutrition and physical activity practices during a one‐day observation. The trial found a significant increase in the mean policy scores, reflecting improvements in quantity and quality of nutrition and physical activity policies among intervention services at follow‐up. The mean nutrition policy score increased from 0.89 at baseline to 5.17 at follow‐up, with no change (0.0) in the mean score within the control group. The mean physical activity policy score increased from 0 at baseline to 2.82 at follow‐up, with no change in the mean score within the control group (0.0). There were no significant differences in unadjusted nutrition (MD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.30, P = 0.55) or physical activity (MD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.29, P = 1.00) EPAO scores between groups at follow‐up. Total EPAO score was not reported.

Dichotomous outcomes

The trial by Alkon and colleagues also assessed the impact of such an implementation strategy on the types and portions of all foods and beverages served to children in care. Assessments were conducted by direct observations conducted by researchers using the Diet Observation in Child Care (DOCC) tool, a validated instrument (Alkon 2014). At follow‐up there were no significant differences between groups on 10 measures of the types and portions of foods and beverages offered to children. Non‐significant improvements favouring intervention services were observed in the offering of: healthy foods (intervention +8%, control +1%); low‐ or non‐fat milk (intervention +10%, control +2%); and low‐fat meats and beans (intervention +17%, control ‐8%) (no other data reported).

3. Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants versus usual practice control

Continuous outcomes

Two trials assessed the effectiveness of implementation strategies consisting of educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing and incentives, and utilised continuous measures of implementation (Hardy 2010; Williams 2002). However, the measures used in each trial differed. Hardy and colleagues utilised a number of implementation measures including the duration (in minutes) (three measures) or frequency (three measures) of staff or service implementation of practices or programmes (Hardy 2010). Williams and colleagues reported changes in the macronutrients of foods served to children (Williams 2002). The primary outcome for the trial conducted by Williams was the fat content of childcare meals. The effect size of the primary implementation outcome for both trials can be seen in Table 3.

Hardy and colleagues conducted a cluster‐randomised controlled trial to evaluate the 'Munch and Move' programme in one state of Australia (New South Wales) (Hardy 2010). All 61 government services (preschools) in the study region were invited to participate in the trial and 29 consented and were randomised. To assess policy and practice implementation, interviews with all service managers occurred at baseline and immediately following the five‐month intervention. The frequency of service provided in fundamental movement skill activities for children increased from 1.3 sessions per week to 3.2 sessions per week in the intervention group whilst remaining unchanged among control services, a difference that was statistically significant (difference at follow‐up of 1.5, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.9, P = 0.05). There were no significant differences between groups in the frequency of structured play sessions per week (adjusted difference 0.02, 95% CI ‐1.5 to 1.5), or unstructured play sessions per week (adjusted difference not reported). There were significant differences for the three measures assessing minutes per session of structured play (adjusted difference 0.09, 95% CI ‐11.6 to 11.8), unstructured play (adjusted difference 7.7, 95% CI ‐15.6 to 31.0) or fundamental movement skill sessions (adjusted difference 3.4, 95% CI ‐9.7 to 16.5). There were no significant differences between groups on any of the four measures of nutrition policy or practice implementation including food‐based activities, rules around food and food policies (effect sizes not reported).

Williams and colleagues conducted a quasi‐experimental trial of a preschool education and food service intervention conducted in Head Start Centers in upstate New York (Bollella 1999; D'Agostino 1999; Spark 1998; Williams 1998; Williams 2002; Williams 2004). The primary aim was to reduce the saturated fat content of service meals and to reduce consumption of saturated fat by children. Six services received either a food service intervention with nutrition classroom education curricula or an identical food service intervention with a classroom safety component. Both of these groups received implementation support to improve food service. Three other childcare services with food operations not amenable to modification served as a control and received safety education curricula. Implementation of menus with nutrient content consistent with guideline recommendations was assessed by obtaining menu recipes and food labels over a five‐day period. The trial found statistically significant within‐group reductions in grams of saturated fat of food listed on menus, the primary implementation outcome, reducing from 11.3 grams (standard deviation (SD) ± 1.9) to 7.6 grams (SD ± 1.7) at the 18‐month follow‐up. Significant within‐group changes were also identified for percentage of energy (kcal) from fat, reducing from 31.0 (SD ± 2.6) to 27.6 (SD ± 2.8) at six months (P < 0.05) and to 25.0 (SD ± 2.6) at 18 months (P < 0.01). Similarly, the percentage of energy (kcal) from saturated fat reduced from 12.5 (SD ± 1.4) to 10.3 (SD ± 1.4) at six months (not significant) and to 8.0 (SD ± 1.2) at the 18‐month follow‐up (P < 0.05) within the intervention group. There were no significant changes in these measures within the control group. Statistical comparisons between groups were not conducted. No other statistically significant changes were reported within either group for the 15 other nutrients measured at 18‐month follow‐up.

Dichotomous outcomes

Hardy and colleagues also reported trial outcomes using dichotomous measures (Hardy 2010). There were no significant differences between groups on any measures of nutrition policy or practice implementation including the conduct of food‐based activities, development of new rules around food and drinks bought from home, and the provision of health information to families, with the effect sizes relative to control ranging from ‐7% to 31% (P > 0.05).

4. Educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing with small incentives or grants with staff wellness programme versus educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach visits or academic detailing

Dichotomous outcomes

Gosliner and colleagues conducted a randomised trial with staff from childcare services in California, USA to assess the impact of an intervention on the nutrition and physical activity environment of childcare services (Gosliner 2010). Childcare services that were participating in a health education and policy development project (Child Health and Nutrition Center Enhancement) were matched on city of location and randomised to an intervention or control group. All services received multi‐strategic implementation support. In addition, staff of intervention services received a wellness programme consisting of individual health assessments (conducted by the research team); monthly newsletters and information with pay‐checks promoting healthy eating and nutrition; a group walking programme where staff received collective incentive rewards as they reached milestones; and staff follow‐up support visits. At 10‐month follow‐up there were significant improvements in two of the eight implementation measures. Specifically, staff at intervention services were significantly more likely to report providing fruit 'more often' to children in children's meals or snacks during the past year (74% of staff) compared to staff at control services (41% of staff) (P = 0.004). Similarly, staff at intervention services were significantly more likely to report providing vegetables 'more often' to children in children’s meals or snacks during the past year (64% of staff) compared to staff at control services (38% of staff) (P = 0.03). There were no significant differences between groups in the provision of sweetened beverages (intervention 7%, control 8%) and sweetened foods (intervention and control 5%) (P values not reported). At children’s celebrations during the past year, staff at intervention services were significantly more likely to report providing fresh fruit (39% of staff) compared to staff at control services (24% of staff) (P = 0.05). Further, intervention staff reported providing fewer sweetened beverages (7% of staff) compared to control (27% of staff) (P = 0.05) and fewer sweetened foods (intervention 15%, control 34%) (P = 0.025). There were no differences between groups in the provision of vegetables at children's celebrations (intervention 32%, control 24%) (P value not reported).

5. Educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, opinion leaders and small incentives versus usual practice control