Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown potential benefits of rapamycin or rapalogs for treating people with tuberous sclerosis complex. Although everolimus (a rapalog) is currently approved by the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) and the EMA (European Medicines Agency) for tuberous sclerosis complex‐associated renal angiomyolipoma and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, applications for other manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex have not yet been established. A systematic review is necessary to establish the clinical value of rapamycin or rapalogs for various manifestations in tuberous sclerosis complex.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of rapamycin or rapalogs in people with tuberous sclerosis complex for decreasing tumour size and other manifestations and to assess the safety of rapamycin or rapalogs in relation to their adverse effects.

Search methods

Relevant studies were identified by authors from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE, and clinicaltrials.gov. Relevant resources were also searched by the authors, such as conference proceedings and abstract books of conferences, from e.g. the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex International Research Conferences, other tuberous sclerosis complex‐related conferences and the Human Genome Meeting. We did not restrict the searches by language as long as English translations were available for non‐English reports.

Date of the last searches: 14 March 2016.

Selection criteria

Randomized or quasi‐randomized studies of rapamycin or rapalogs in people with tuberous sclerosis complex.

Data collection and analysis

Data were independently extracted by two authors using standard acquisition forms. The data collection was verified by one author. The risk of bias of each study was independently assessed by two authors and verified by one author.

Main results

Three placebo‐controlled studies with a total of 263 participants (age range 0.8 to 61 years old, 122 males and 141 females, with variable lengths of study duration) were included in the review. We found high‐quality evidence except for response to skin lesions which was judged to be low quality due to the risk of attrition bias. Overall, there are 175 participants in the treatment arm (rapamycin or everolimus) and 88 in the placebo arm. Participants all had tuberous sclerosis complex as proven by consensus diagnostic criteria as a minimum. The quality in the description of the study methods was mixed, although we assessed most domains as having a low risk of bias. Blinding of treatment arms was successfully carried out in all of the studies. However, two studies did not report allocation concealment. Two of the included studies were funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

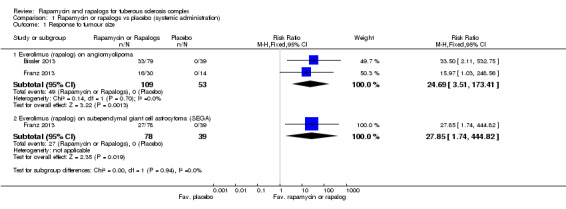

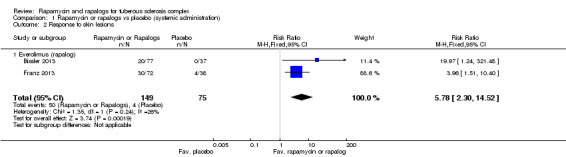

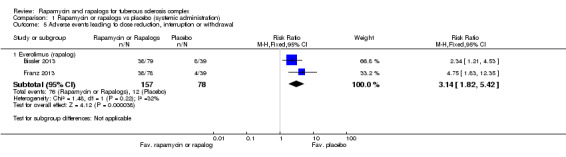

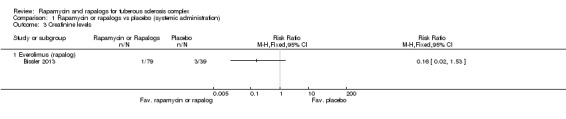

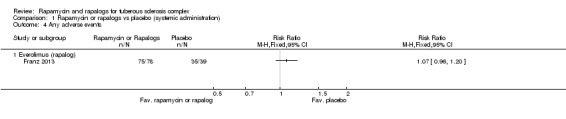

Two studies (235 participants) used oral (systemic) administration of everolimus (rapalog). These studies reported response to tumour size in terms of the number of individuals with a reduction in the total volume of tumours to 50% or more relative to baseline. Significantly more participants in the treatment arm (two studies, 162 participants, high quality evidence) achieved a 50% reduction in renal angiomyolipoma size, risk ratio 24.69 (95% confidence interval 3.51 to 173.41) (P = 0.001). For the sub‐ependymal giant cell astrocytoma, our analysis of one study (117 participants, high quality evidence) showed significantly more participants in the treatment arm achieved a 50% reduction in tumour size, risk ratio 27.85 (95% confidence interval 1.74 to 444.82) (P = 0.02). The proportion of participants who showed a skin response from the two included studies analysed was significantly increased in the treatment arms, risk ratio 5.78 (95% confidence interval 2.30 to 14.52) (P = 0.0002) (two studies, 224 participants, high quality evidence). In one study (117 participants), the median change of seizure frequency was ‐2.9 in 24 hours (95% confidence interval ‐4.0 to ‐1.0) in the treatment group versus ‐4.1 in 24 hour (95% confidence interval ‐10.9 to 5.8) in the placebo group. In one study, one out of 79 participants in the treatment group versus three of 39 in placebo group had increased blood creatinine levels, while the median percentage change of forced expiratory volume at one second in the treatment arm was ‐1% compared to ‐4% in the placebo arm. In one study (117 participants, high quality evidence), we found that those participants who received treatment had a similar risk of experiencing adverse events compared to those who did not, risk ratio 1.07 (95% confidence interval 0.96 ‐ 1.20) (P = 0.24). However, as seen from two studies (235 participants, high quality evidence), the treatment itself led to significantly more adverse events resulting in withdrawal, interruption of treatment, or reduction in dose level, risk ratio 3.14 (95% confidence interval 1.82 to 5.42) (P < 0.0001).

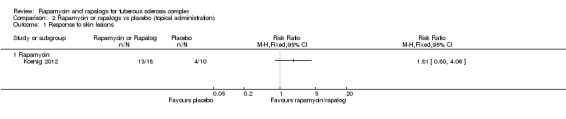

One study (28 participants) used topical (skin) administration of rapamycin. This study reported response to skin lesions in terms of participants' perception towards their skin appearance following the treatment. There was a tendency of an improvement in the participants' perception of their skin appearance, although not significant, risk ratio 1.81 (95% confidence interval 0.80 to 4.06, low quality evidence) (P = 0.15). This study reported that there were no serious adverse events related to the study product and there was no detectable systemic absorption of the rapamycin during the study period.

Authors' conclusions

We found evidence that oral everolimus significantly increased the proportion of people who achieved a 50% reduction in the size of sub‐ependymal giant cell astrocytoma and renal angiomyolipoma. Although we were unable to ascertain the relationship between the reported adverse events and the treatment, participants who received treatment had a similar risk of experiencing adverse events as compared to those who did not receive treatment. Nevertheless, the treatment itself significantly increased the risk of having dose reduction, interruption or withdrawal. This supports ongoing clinical applications of oral everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Although oral everolimus showed beneficial effect on skin lesions, topical rapamycin only showed a non‐significant tendency of improvement. Efficacy on skin lesions should be further established in future research. The beneficial effects of rapamycin or rapalogs on tuberous sclerosis complex should be further studied on other manifestations of the condition.

Plain language summary

Drugs that aim to relieve clinical symptoms of tuberous sclerosis complex

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of rapamycin or rapalogs for reducing the severity of clinical symptoms in people with tuberous sclerosis complex.

Background

Tuberous sclerosis or tuberous sclerosis complex is a genetic disease caused by mutations in tuberous sclerosis complex 1 or tuberous sclerosis complex 2 genes that affects several organs such as the brain, kidneys, heart, lungs and skin. The incidence has been reported to be one in approximately 6000. Previous studies have shown potential benefits of rapamycin or rapalogs for treating people with tuberous sclerosis complex. Although everolimus (a rapalog) is currently approved by the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) and EMA (European Medicines Agency) for tumours associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (renal angiomyolipoma and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma), the use of these drugs for treating other symptoms of the condition has yet to be established. This review aims to bring together clinical trials in this area to establish the clinical value of rapamycin and rapalogs for various symptoms of tuberous sclerosis complex.

Search date

The evidence is current to: 14 March 2016.

Study characteristics

The review included three studies with 263 people with tuberous sclerosis complex aged between 0.8 and 61 years of age. However, one study involved five people with sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (without tuberous sclerosis complex) which we could not remove from the analysis. Studies compared rapamycin or rapalogs with placebo and people were selected for one treatment or the other randomly. The duration of the studies was variable. Two of the included studies were funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Key results

There is evidence that oral everolimus (rapalog) increased the number of people who achieved a 50% reduction in the size of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma and renal angiomyolipoma. Oral everolimus also showed benefit in terms of response to skin lesions, although applying rapamycin to the skin only showed a tendency for improvement. Those who received treatment had a similar risk of experiencing adverse events as compared to those who did not receive treatment. However, more people receiving the active treatment had severe adverse events causing them to withdraw from the trial, temporarily stop treatment or reduce their dose compared to the control group.

Quality of the evidence

Two of the included studies generally showed a low risk of bias in study design, except for one study where it was unclear whether people knew which group they would be put into. Another included study showed different degrees of risk of bias with regards to study design, for example, due to missing data and lack of clarity about how people where put into the different groups. The results from the studies were generally of high quality, except for response to skin lesions from topical rapamycin due to missing outcome data and seizure frequency due to the way participants were selected.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Tuberous sclerosis or tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (OMIM#191100; OMIM#613254) is a genetic disease that affects several organs such as the brain, kidneys, heart, lungs and skin (NINDS 2013). The primary manifestation is as a consequence of growth of non‐malignant tumours in the various systems described. The incidence has been reported to be one in approximately 6000 (Osborne 1991). However, its true incidence is not known because of a number of undiagnosed cases consisting mostly of mildly affected or asymptomatic individuals (Osborne 1991).

Two disease‐causing genes have been identified by positional cloning, TSC1 (van Slegtenhorst 1997) and TSC2 (ECTSC 1993). The TSC1 gene is located on chromosome 9q34, and encodes the protein, hamartin (130 kDa, 1164 amino acids) (van Slegtenhorst 1997). The TSC2 gene is located on chromosome 16p13.3, and encodes another protein, tuberin (180 kDa, 1807 amino acids) (ECTSC 1993). However, 10% to 25% of people with TSC showed no TSC1/TSC2 mutation as identified by conventional genetic testing (Northrup 2013). A recent report of 53 people with TSC with no mutation identified, reported that mosaicism was observed in the majority (58%) and then followed by intronic mutations, which were seen in 40% of the study population. Two mutations were even identified in skin tumour biopsies only, and were not seen at appreciable frequency in blood or saliva DNA (Tyburczy 2015). These genetic abnormalities are generally inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Nevertheless, in more than 60% of cases sporadic mutations are known to occur (van Slegtenhorst 1999).

The defective production of hamartin is caused by TSC1 mutations (NINDS 2013). Mutations on the TSC2 gene lead to the defective production of another protein, tuberin and are usually related to more severe manifestations (Dabora 2001). Both TSC1 and TSC2 are tumour suppressor genes, the defect of which will lead to an uncontrolled proliferation of benign tumours called tubers in various sites (Gao 2001). People with TSC present at different ages with a variety of clinical manifestations. Common presenting symptoms include skin lesions, seizures, learning disabilities or manifestations of tumours affecting organs such as the brain, heart, eyes, or the kidneys (Napolioni 2008). The disease can be diagnosed clinically by assessing individuals against major or minor criteria, depending on the signs and symptoms present (Northrup 2013).

Investigation of somatic mutations in a variety of TSC hamartomas supports classification of the TSC1 and TSC2 as tumour suppressor genes (Cheadle 2000). Interaction between hamartin and tuberin has a stoichiometry of 1:1 and is stable; a tight binding interaction between tuberin and hamartin forming a tumour suppressor heterodimer has been elucidated (Kwiatkowski 2003). This complex inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) which is a key regulator in the signalling pathway of cell proliferation and organ size (Kwiatkowski 2003). It has been reported that hamartin‐tuberin complex regulates mTOR via hydrolysis of Rheb‐GTP into its inactive GDP bound state, Rheb‐GDP (Rosner 2004; Tee 2003).

Diagnostic criteria for TSC was recently updated (Northrup 2013) from its 1998 consensus (Roach 1998). The disease can now be diagnosed either genetically or clinically (Northrup 2013). Genetic diagnostic criteria include the identification of either a TSC1 or TSC2 pathogenic mutation in DNA from normal tissue. A pathogenic mutation is defined as a mutation that clearly inactivates the function of the TSC1 or TSC2 proteins (e.g., out‐of‐frame indel or nonsense mutation), prevents protein synthesis (e.g., large genomic deletion), or is a missense mutation whose effect on protein function has been established by functional assessment (Hoogeveen‐Westerveld 2012; Hoogeveen‐Westerveld 2013; LOVD TSC1; LOVD TSC2). Clinical diagnostic criteria remain with the major and minor clinical features that enable clinicians to clinically diagnose TSC (Northrup 2013). However, as compared to the older criteria (Roach 1998), less minor criteria were noted and 'cortical tubers' in major criteria was replaced by a broader feature 'cortical dysplasia' which includes tubers and cerebral white matter radial migration lines (Northrup 2013).

The new consensus for TSC clinical diagnostic criteria defines only possible and definitive diagnosis (Northrup 2013) without a probable diagnosis as defined in the old consensus (Roach 1998). A definitive diagnosis can be made when there are either two major features or one major feature with two or more minor features. A possible diagnosis can be made when there are either one major feature or two or more minor features (Northrup 2013). Major features in the new consensus include hypomelanotic macules (three or more, at least five mm diameter), angiofibromas (three or more) or fibrous cephalic plaque, ungual fibromas (two or more), shagreen patch, multiple retinal hamartomas, cortical dysplasias, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, cardiac rhabdomyoma, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) and angiomyolipomas (two or more). It is of note, however, finding on the combination of LAM and angiomyolipomas still require another feature for a definitive diagnosis (Northrup 2013). Minor features include 'confetti' skin lesions, dental enamel pits (more than three), intraoral fibromas (two or more), retinal achromic patch, multiple renal cysts and nonrenal hamartomas (Northrup 2013).

Tumours of major clinical attentions include those involving the heart, brain, kidney and lung. Generally, tumour manifestations of TSC occur later in life, except for cardiac rhabdomyomas. Studies estimated that up to 70% to 90% of children with rhabdomyomas have TSC, and at least 50% of children with TSC have rhabdomyomas. Nearly 100% of foetuses with multiple rhabdomyomas have TSC, underscoring the practical importance of identifying additional tumours at the time of fetal assessment for diagnosis and prognosis (Hinton 2014). A recent report of a rhabdomyomas case series showed 31 out of 33 rhabdomyoma cases were diagnosed with TSC (Sciacca 2014). The case series reported 205 masses, mostly localized in interventricular septum, right ventricle and left ventricle. During follow up, a reduction of rhabdomyomas in terms of both the number and size was observed in all but one child (Sciacca 2014).

There are three types of brain lesions in TSC ‐ cortical dysplasia (cortical tubers and cerebral white matter radial migration lines), subependymal nodules (SEN; formed in the walls of the ventricles) and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA; develops from SEN and grow such that they may block the flow of fluid within the brain, causing a buildup of fluid and pressure and leading to headaches and blurred vision) (NINDS 2013). Cortical tubers and cerebral white matter radial migration lines are commonly associated with intractable epilepsy and learning difficulties in TSC (Northrup 2013). The majority of people with TSC have SEN that remain static throughout their lifetime. However, approximately 20% of people with TSC demonstrate progressive growth of SEN to become SEGA, which may produce neurologic complications, including obstructive hydrocephalus (Crino 2010; Franz 2010).

Renal problems in TSC, including angiomyolipomas (which occur in 80% of people with TSC) and multiple renal cysts, comprise the second leading cause of premature death after severe intellectual disability (Shepherd 1991). Angiomyolipomas are benign tumours composed of vascular, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue. In the kidney, angiomyolipomas can cause serious issues with bleeding because of their vascular nature and can lead to the need for dialysis and even renal transplantation (Kozlowska 2008). Multiple renal cysts can be seen in people with TSC who have a TSC1 or TSC2 mutation or as part of a contiguous gene deletion syndrome involving the TSC2 and PKD1 genes (Bissler 2010).

In people with TSC, LAM is associated with interstitial expansion of the lung with benign‐appearing smooth muscle cells that infiltrate all lung structures (Johnson 2010; McCormack 2010). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) activity was believed to facilitate tumour cell invasion by disrupting basement membranes (Kleiner 1999). Levels of urinary MMPs were elevated in people with LAM, and MMPs were found in LAM lung nodules (Glasgow 2010). Studies suggest a role for metalloproteinases in the cystic lung destruction of LAM (Glasgow 2010). Individuals typically present with progressive dyspnoea on exertion and recurrent pneumothoraces in the third to fourth decade of life. Cystic pulmonary parenchymal changes consistent with LAM are observed in 30% to 40% of females with TSC, but recent studies suggest that lung involvement may increase with age such that up to 80% of TSC females are affected by the age of 40 years (Cudzilo 2013). Cystic changes consistent with LAM are also observed in about 10% to 12% of males with TSC, but symptomatic LAM in males is very rare (Adriaensen 2011; Muzykewicz 2012).

Long‐term morbidity that requires life‐long institutional care is also of concern in TSC. Best estimates from epidemiological populations suggest that about 45% of individuals with TSC have intellectual disability (Joinson 2003). Rates of self‐injury and aggression in children with TSC were 27% and 50%, respectively. These are high but not significantly different from rates in children with Down syndrome or other syndrome groups (Eden 2014). In addition, 30 out of 45 women who were diagnosed with TSC as adults, actually met the clinical criteria for TSC in childhood. Although these women had minimal morbidity during childhood, they were at risk of life‐threatening pulmonary and renal manifestations (Seibert 2011).

Once the diagnosis of TSC is established and initial diagnostic evaluations completed, continued surveillance is necessary to monitor the progression of known problems or lesions and the emergence of new ones. Although some manifestations that appear during childhood do not cause significant problems in adulthood and vice versa, some others may be present throughout the entire life‐span of the individual, such as epilepsy and TSC‐associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) (Krueger 2013).

Description of the intervention

Rapamycin (sirolimus) and rapalogs (analogs of rapamycin) are first generation inhibitors of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin). This is a protein kinase that controls cell growth, proliferation, and survival. Often mTOR signaling is up‐regulated in cancer and there is a great interest in developing drugs that target this enzyme. Until recently, rapamycin sensitivity was the major criterion used to identify mTOR‐controlled effects (Ballou 2008).

During the 1980s, rapamycin (sirolimus) was discovered to show an anti‐cancer activity (Faivre 2006). However, due to its unfavourable pharmacokinetic properties, the development of rapamycin for the treatment of cancer was not successful at that time (Yuan 2009). Later on, analogs of rapamycin (rapalogs) with more favourable pharmakokinetic properties and reduced immunosuppressive effects were discovered (Faivre 2006). These include temsirolimus (CCI‐779), everolimus (RAD001), biolimus A9 and zotarolimus (ABT‐578) (Falotico 2005, Brachmann 2009). Both biolimus and zotarolimus are drug‐eluting coronary stents for preventing coronary artery restenosis.

Rapamycin (C51H79NO13) is a macrolide compound that was isolated in 1975 from Streptomyces hygroscopicus found in a soil sample on Easter Island. It prevents activation of T cells and B cells by inhibiting their response to interleukin‐2 (IL‐2). It is an FDA‐approved drug for immunosuppression after organ transplantation. Rapamycin also possesses both antifungal and antineoplastic properties. Rapamycin is administered orally once daily, with or without food as a tablet or a solution with a maximum daily dose of 40 mg (RxList 2015a). The most common adverse reactions (at least 30%) observed with rapamycin in clinical studies are: peripheral oedema; hypertriglyceridaemia; hypertension; hypercholesterolaemia; creatinine increase; constipation; abdominal pain; diarrhoea; headache; fever; urinary tract infection; anaemia; nausea; arthralgia; pain; and thrombocytopaenia (RxList 2015a).

Topical rapamycin has been used for facial angiofibromas in people with TSC (Haemel 2010; Mutizwa 2011). There are various preparations for topical rapamycin that have been reported with concentrations ranging from 0.1% to 1% (Madke 2013). An irritation and burning sensation is the most common side effect seen after topical administration of rapamycin. Individuals should be prescribed topical hydrocortisone 0.1% cream or desonide 0.05% lotion along with liberal emollients to counteract any irritation and ensure compliance. It is practical to use commercially available oral solution of rapamycin (1 mg/ml) as a topical formulation since compounding pharmacies are not always readily accessible and the stability and efficacy of compounded preparation cannot be ensured (Madke 2013).

Temsirolimus (C56H87NO16) has a molecular weight of 1030.30 and is non‐hygroscopic. It is insoluble in water and soluble in alcohol. It has no ionizable functional groups, and its solubility is independent of pH. In in vitro studies using renal cell carcinoma cell lines, temsirolimus inhibited the activity of mTOR and resulted in reduced levels of the hypoxia‐inducible factors HIF‐1 and HIF‐2 alpha, and the vascular endothelial growth factor. It has been indicated for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma with a recommended dose of 25 mg infusion over a 30 to 60 minute period once a week. The most common adverse reactions (at least 30%) are rash, asthenia, mucositis, nausea, oedema, and anorexia. The most common laboratory abnormalities (at least 30%) are anaemia, hyperglycaemia, hyperlipaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, lymphopenia, elevated alkaline phosphatase, elevated serum creatinine, hypophosphataemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and leukopenia. Temsirolimus is contraindicated in individuals with bilirubin more than 1.5 times of upper limit of normal range. (RxList 2015b).

Everolimus (C53H83NO14) has a molecular weight of 958.2. It has been indicated for the treatment of post‐menopausal women with advanced hormone receptor‐positive, HER2‐negative breast cancer, adults with progressive neuroendocrine tumours of pancreatic origin (PNET), adults with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC), adults with renal angiomyolipoma, SEGA and TSC. However, further follow up of people with TSC is still required to determine long‐term outcomes. The recommended dose of everolimus tablets is 10 mg, to be taken once daily at the same time every day. The most common adverse reactions (incidence at least 30%) were stomatitis, infections, rash, fatigue, diarrhoea, and decreased appetite. The most common laboratory abnormalities (incidence at least 50%) were hypercholesterolaemia, hyperglycaemia, increased AST, anaemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, increased alanine transaminase (ALT), and hypertriglyceridaemia (RxList 2016).

While non‐randomised trials showed that rapamycin or rapalogs reduce the size of TSC‐associated tumours in humans, such as angiomyolipoma, LAM and SEGA, tumour regression does not occur in all cases and tumour regrowth is generally observed with the cessation of treatment (Bissler 2008; Cardamone 2014; Davies 2008; Franz 2006). Furthermore, evidence on the effect of rapamycin (Canpolat 2014, Cardamone 2014) or rapalogs (Muncy 2009, Krueger 2013) in improving epilepsy is not without opposition (Overwater 2014; Wiemer‐Kruel 2014). Rapamycin or rapalogs have also been tested on other manifestations of TSC with mostly promising results, albeit with a variable degree of evidence. Reports described improvement in facial angiofibroma (Foster 2012; Truchuelo 2012; Wataya‐Kaneda 2012; Wheless 2013), cardiac rhabdomyoma (Tiberio 2011), renal cell carcinoma (Pressey 2010) but not the optic nerve tumour (Sparagana 2010) among people with TSC. An open study of 10 people with TSC‐associated facial angiofibroma reported sustained improvement in erythema and in the size and extension of the lesions. Rapamycin plasma levels remained below detection limits (0.3 ng/mL) in all cases. The formula was well‐tolerated with no local or systemic adverse effects (Salido 2012). Although the response results in early human trials are encouraging, conflicting evidence is present and it is possible that a longer term use of rapamycin may be more effective. Identification of other active drugs is also of interest to improve the response rate or durability of response, or both (Lee 2009).

Rapamycin or rapalogs are extensively metabolized by O‐demethylation or hydroxylation (or both) in the intestinal wall and liver and undergo counter‐transport from enterocytes of the small intestine into the gut lumen. Seven major metabolites, including hydroxy, demethyl, and hydroxydemethyl, are identifiable in whole blood. Some of these metabolites are also detectable in plasma, faecal, and urine samples (RxList 2015a; RxList 2015b; RxList 2016).

In the human and rat liver, rapamycin or rapalogs is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P‐450 3A4 (Sattler 1992). Rapamycin or rapalogs are substrates for both CYP3A4 and P‐gp (P‐glycoprotein 1). Inducers of CYP3A4 and P‐gp may decrease rapamycin or rapalogs concentrations whereas inhibitors of CYP3A4 and P‐gp may increase their concentrations. Drugs and agents that could increase the concentration of rapamycin or rapalogs in the blood include cyclosporine, bromocriptine, cimetidine, cisapride, clotrimazole, danazol, diltiazem, fluconazole, protease inhibitors (e.g., for HIV and hepatitis C that include drugs such as ritonavir, indinavir, boceprevir, and telaprevir), metoclopramide, nicardipine, troleandomycin, verapamil, grapefruit (RxList 2015a), Seville oranges, limes and pomelos (Tanzi 2013). Drugs and agents that could decrease rapamycin or rapalogs concentrations include carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifapentine, St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum).

In addition, verapamil concentration could increase when given with rapamycin or rapalogs. Immunosuppressants may affect response to vaccination. Therefore, during treatment with rapamycin or rapalogs, vaccination may be less effective. The use of live vaccines should be avoided, including, but not limited to, measles, mumps, rubella, oral polio, bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), yellow fever, varicella, and TY21a typhoid (RxList 2015a).

How the intervention might work

As uncontrolled proliferation of benign tumours in various organs is part of the pathophysiology, due to the loss of tumour suppressor genes, inhibitors of such processes is a logical step in tumour suppression. Cell growth and proliferation function is largely regulated in its final pathway, by a set of processes involving a common regulatory mTOR protein. This protein regulates vital cell growth processes, receives external signals from growth factors, hormones, and proteins. It then gives the 'on' or 'off' signals for the cell to grow and divide. In normal circumstances, mTOR combines with several other cellular components to form two distinct complexes, termed mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Bhaskar 2007).

Inhibiting mTOR kinase was thought to be a useful approach to systemic therapy for TSC or LAM (or both) because rapamycin has been shown to normalize dysregulated mTOR signalling in cells that lack normal hamartin or tuberin (Gao 2001; Goncharova 2002; Inoki 2002; Kwiatkowski 2002; Manning 2002; Potter 2002).

A detailed look into the mode of action of rapamycin discovered that it binds to the cytosolic protein FK‐binding protein 12 (FKBP12). The sirolimus‐FKBP12 complex inhibits the mTOR from forming the mTORC1, thus inhibiting cell proliferation. A previous study utilising cohorts of Tsc2+/‐ mice and mouse model of Tsc2‐null tumours showed that treatment with an mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) kinase inhibitor (CCI‐779, a rapamycin analogue) reduced the severity of TSC‐related disease without significant toxicity (Lee 2005).

The mechanisms by which rapamycin or rapalogs inhibits mTOR are not fully understood, but rapamycin associates with FKBP12 to bind to the FRB (FKBP12–rapamycin‐binding) domain of mTOR. Binding of the rapamycin–FKBP12 complex to mTOR can destabilize the mTORC1 complex and interfere with the activation of mTOR by phosphatidic acid. Several new compounds are available to inhibit mTOR, either by interfering with complex formation (FKBP12‐dependent or FKBP12‐independent) or by directly inhibiting the catalytic domain of mTOR (Ehninger 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

There is currently no established therapy for TSC, despite the life‐threatening morbidities of the disorder. Previous studies have shown potential clinical applications of rapamycin for TSC. Although everolimus (a rapalog) is currently FDA‐ and EMA‐approved for TSC‐associated renal angiomyolipoma and SEGA, applications for other manifestations of TSC are yet to be established. This review aims to bring together clinical trials in this area to establish the clinical value of rapamycin or rapalogs for various manifestations in TSC.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of rapamycin or rapalogs administration in people with TSC for decreasing the size of TSC‐related tumours and other manifestations and to assess the safety of rapamycin or rapalogs relating to their adverse effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised studies. Studies in which quasi‐randomised methods, such as alternation, are used were included when there is sufficient evidence that the treatment and control groups are similar at baseline.

Types of participants

People with known TSC as proven by the clinical features designated in the revised consensus on TSC diagnostic criteria (genetic or clinical (or both) manifestations) (Northrup 2013). Individuals diagnosed using older diagnostic criteria (Hyman 2000; Roach 1998; Roach 1999) would be included if we could not ascertain compliance with the latest diagnostic criteria through communications with trial authors.

Types of interventions

Rapamycin or rapalogs designed to reduce any TSC‐associated symptoms in people with TSC compared to placebo or any standard treatments, applied systemically or topically.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Tumour size (any unit of analysis found)

Secondary outcomes

Skin lesion response

Aneurysm size for angiomyolipomas (any unit of analysis found)

Frequency of seizure (times)*

Forced expiratory volume at one second (FEV1) / forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio

Creatinine level (mg/dL)

Any reported adverse effect or toxicity

* Please refer to 'Differences between protocol and review' for information about this post hoc addition to outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not restrict the searches by language as long as an English translation was available for non‐English reports.

Electronic searches

All electronic searches were carried out on 14 March 2016. Relevant studies were identified by authors from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 1, 2012 to Issue 2, 2016) via the Central register of Studies Online (crso.cochrane.org), Ovid MEDLINE (published 1946 to 14 March 2016), and clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov). The search strategies used and filtering options were as outlined in the appendices (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3). The Ovid MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011).

Searching other resources

The authors also searched relevant resources, such as conference proceedings and books of conference abstracts (where accessible). This included the TSC International Research Conferences (2009 to 2015), 2012 International TSC Congress, 2014 World TSC Conference and the Human Genome Meeting (2010 to 2016). The authors will continue to search resources from similar conferences for future updates of this review. Investigators will be contacted whenever we identify eligible studies from these sources and if more detailed information is needed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In order to select studies for inclusion in the review, the inclusion criteria were applied by two authors independently. The authors reached consensus by discussion between all four authors for any disagreements which arose on the suitability of a study for inclusion in the review.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by NFDI using the standard acquisition forms and then verified by one author (THS). The authors reached consensus by discussion upon any disagreements arise on the data extraction. For missing information as specified in other parts of this manuscript, the authors will contact study investigators for future update of this review. The eligible time period for endpoint analysis is at least one month after rapamycin administration. We excluded studies from analysis when the only time period reported was less than one month. While we planned to analyse data in three blocks of time (one to three months; over three months to six months; and longer than six months), none of the included studies reported enough information for such analyses. We aim, if possible, to undertake this for an update of this review, pending communication with study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of each study was assessed by NFDI and then verified by one author (ZAMHZH). The authors generated a risk of bias table for each study as described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In particular, details of the following components were examined:

sequence generation (e.g. whether randomization was adequate);

allocation concealment (e.g. whether the allocation was adequately concealed);

blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (e.g. whether the the participants, personnel and outcome assessors were blinded);

incomplete outcome data (e.g. whether attrition and exclusion were reported);

selective outcome reporting (e.g. whether the study was free from selective outcome reporting);

other sources of bias (will be specified during the assessment).

All components were assessed by authors using the methods as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. For each item, the table provided a description of what was reported in the study and the subjective judgement regarding possible bias (low, high or unclear risk of bias) (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

We pooled the analysis of different types of the different drugs types and plan to perform subgroup analysis for rapamycin and rapalogs if in future versions of the review we identify more studies. We separated the analysis of different modes of applications into systemic or topical administration.

We could not obtain tumour size in the form of continuous data. Instead, authors obtained response of treatment to tumour size (Bissler 2013;Franz 2013) and skin lesions (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012) and we analysed data as dichotomous. The studies reported creatinine levels as the number of participants with increased creatinine levels in both treatment or placebo arms. We therefore analysed these data as dichotomous. Two studies reported lung functions (Bissler 2013) and frequency of seizures (Franz 2013) as only median change. None of the included studies reported aneurysm size of angiomyolipoma. All studies reported adverse effects (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

The authors reported dichotomous outcomes (number of participants having 50% reduction in tumour size and skin lesions, presence or absence of adverse effects and treatment response to creatinine level). We calculated the risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) based on the ratio of an outcome among treatment‐allocated participants to that among controls. We calculated the pooled estimate of the treatment effect for each outcome across studies by determining the RR.

In future updates of this review, if continuous data of these outcomes become available, we will record them as either mean change from baseline for each group or mean post‐treatment values and standard deviation (SD) for each group. We will assess continuous outcomes by the calculation of the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs. Where trials report multiple measures for the same outcome (e.g. absolute change FEV1 per cent predicted, percentage change in FEV1 per cent predicted, or per cent change of absolute FEV1 volumes) we will calculate the standardised MDs (SMD). We will consider absolute changes in FEV1 in the context of comparable data being available for each participant before and after the intervention so that a calculation of the effect size is possible.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include any cross‐over studies in the review; in future updates, we will only include cross‐over studies if we consider there to be a sufficient washout period between the treatment arms. We will analyse any data from such studies using paired analyses as described by Elbourne (Elbourne 2002).

For cluster randomised studies, if we regard these as not being analysed correctly by study authors, we will calculate the effective sample size and monitor and analyse them based on the method described by Donner (Donner 2002). We plan to analyse any such studies separately. We aim to address the risk of unit of analysis error caused by repeated observations on participants and whether the individual or the tumours are randomised based on the information provided in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the individual is randomised, we will include all tumours observed in the studies.

Dealing with missing data

If any included studies were only reported as abstracts, presented at meetings, or reported to the review authors, we sought full reports from the study investigators. For missing information as specified in other parts of this manuscript, we plan to contact study investigators for future updates of this review. In order to allow an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, we grouped data by allocated treatment groups, irrespective of later exclusion (regardless of cause) or loss to follow up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for heterogeneity between studies using a standard Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003) (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.5).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (systemic administration), Outcome 1 Response to tumour size.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (systemic administration), Outcome 2 Response to skin lesions.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (systemic administration), Outcome 5 Adverse events leading to dose reduction, interruption or withdrawal.

The Chi2 test is a statistical test for heterogeneity, whereas I2 assesses the quantity of inconsistency across studies in the meta‐analysis. The authors used a cut‐off P value of 0.1 to determine significance. This is because of the generally anticipated low power of the reported studies due to the disease being rare. The authors used the following I2 ranges to interpret heterogeneity: 0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The authors visually assessed the forest plot to see if CIs overlapped.

Assessment of reporting biases

For all studies, we compared the 'Methods' section of the full published paper with the 'Results' section to ensure that all measured outcomes were reported.

The review included fewer than 10 studies, so we did not construct any funnel plots for assessment, either visually or statistically (small‐study effects analyses). However, in future updates, provided that we include at least 10 studies, we will carry out a visual assessment of funnel plots and statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry (small‐study effects analyses). If we identify any evidence of small‐study effects, we will attempt to understand the source, including the possibility of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We employed a fixed‐effect analysis in this review. In future updates, if there is evidence of heterogeneity (I2 statistic more than 40%), we plan to use a random‐effects analysis.

We compared rapamycin or rapalogs versus placebo or other standard treatment. We determined the exact time‐points that we reported after analysing the included studies, but they were at least six months apart.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future versions of this review, if we identify heterogeneity between the studies (I2 statistic more than 40%), we will examin subgroups, such as: age of participants (0 years to 10 years, over 10 years to 20 years, over 20 years) and the gene affected (TSC1 or TSC2).

In addition to this, where appropriate, we plan to perform subgroup analyses of different medications (rapamycin or rapalogs), different locations and types of tumour, and if rapamycin or rapalogs were administered in conjunction with other agent(s).

Sensitivity analysis

Authors plan to test the robustness of the results with the following sensitivity analyses:

studies where quasi‐randomisation methods are used;

studies where there are variations among one or more inclusion criteria;

studies of different designs (e.g. cross‐over studies).

In addition, we plan to undertake a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of combining endpoint analysis across all time‐periods.

Summary of findings table

Summary of findings tables were created with the following outcomes, depending on data available in the included studies:

50% reduction of tumour size;

response to skin lesions;

frequency of seizures (times);

creatinine level (mg/dL);

FEV1/FVC ratio; and

any reported adverse effect or toxicity.

Results

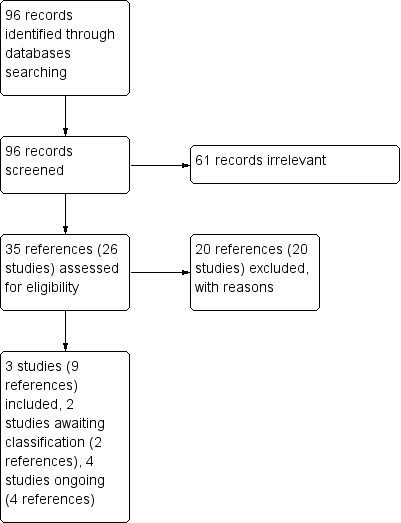

Description of studies

Results of the search

Please refer to the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The search identified 29 relevant studies, we excluded 20 studies; 14 of these are case series or case reports (Birca 2010; Foster 2012; Franz 2006; Herry 2007; Hofbauer 2008; Koenig 2008; Lam 2010; Pressey 2010; Salido 2012; Sparagana 2010; Staehler 2012; Wataya‐Kaneda 2011; Wienecke 2006; Yalon 2011); six are phase 2 clinical trials with no control arm or randomization (Cabrera 2011; Dabora 2011; Davies 2011; Krueger 2010; Tanaka 2013; Wataya‐Kaneda 2015). Two studies were awaiting classification in a future update of this review (NCT01289912; NCT01526356). Four studies are ongoing clinical trials (NCT01713946; NCT01730209; NCT01954693; NCT02635789). Three studies were eligible for inclusion in the current review (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

Included studies

Refer to Characteristics of included studies.

Trial characteristics

All three studies were described as double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled studies (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012). Additionally, the Bissler and the Franz studies were described as phase 3 studies (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

The Bissler study was multicentre (24 centres in 11 countries) as was the Franz study (24 centres in 10 countries) (Franz 2013). The Koenig study was carried out in a single centre in Texas, USA (Koenig 2012).

Participants

The Bissler study randomised 118 participants having at least one angiomyolipoma (3 cm or larger in diameter), and a definite diagnosis of TSC per consensus criteria. There were 79 participants in the treatment group and 39 in the placebo group. This study included adults (18 years or older). People were excluded if their angiomyolipoma required surgery at randomisation, or if they had angiomyolipoma‐related bleeding or embolisation during the six months before randomisation. Those with lymphangioleiomyomatosis were excluded if their carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLco) was 35% or less, oxygen saturation was below normal at rest, or oxygen saturation was 88% or less on a six‐minute walking test with up to 6 L/min of oxygen (Bissler 2013).

The Franz study randomised 117 participants having at least one angiomyolipoma (3 cm or larger in diameter), and a definite diagnosis of TSC per consensus criteria. There were 78 participants in the treatment group and 39 in the placebo group. This study included participants aged up to 65 years old. Those individuals who had previously used antiproliferative agents were excluded from the study (Franz 2013).

The Koenig study randomised 28 (13 females and 15 males) participants with a diagnosis of TSC. There were 18 participants in the treatment group and 10 in the placebo group. This study included people over 13 years of age. Participants were excluded if they were currently pregnant, were using oral rapamycin, or had any form of immune dysfunction (Koenig 2012).

Interventions

The Bissler study compared everolimus and placebo; details of the placebo were not provided. Everolimus was given for six months at a dose of 10 mg per day, with dose modifications allowed on the basis of safety findings (systemic administration). Concomitant use of strong inhibitors or inducers of cytochrome P450 3A4 or p‐glycoprotein (PgP) was to be avoided during the study and participants were prohibited from using antiproliferative agents other than the study drug (Bissler 2013).

The Franz study compared everolimus and placebo; details of the placebo were not provided. Everolimus was administered orally at a starting dose of 4.5 mg/m² body surface area per day and subsequently adjusted to attain blood trough concentrations of 5 to 15 ng/mL with dose modifications allowed for the purpose of treatment‐related toxic effects (systemic administration). The starting dose for children with malignancies was chosen to be just less than the maximum‐tolerated dose (5 mg/m² per day). Participants were prohibited from using strong and moderate inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and P‐glycoprotein (except antiepileptic drugs), strong inducers of CYP3A4 (except antiepileptic drugs), and concomitant use of antiproliferative drugs. The participants were treated with everolimus for six months with an extension phase (upto four years after the last participant was randomly assigned to treatment) if the results of the core phase favoured everolimus (Franz 2013).

The Koenig study compared rapamycin and placebo; details of the placebo were not provided. Over a period of six months, rapamycin was given at a dose of either 1 mg per 30 cc (0.003%) or 5 mg per 30 cc (0.015%). A thin coating of rapamycin was applied on the skin directly over the treatment area every morning (topical administration). The product was allowed to air dry for 60 minutes following application and was removed by gentle washing in the morning (Koenig 2012).

Outcomes

The Bissler study reported the effect of everolimus on response rate of tumour (angiomyolipoma and skin lesion), tumour volume and time for angiomyolipoma progression. Adverse events were also reported (Bissler 2013).

The Franz study reported the effect of everolimus on tumour volume (subependymal giant cell astrocytomas), rate of tumour response, seizure frequency, time for tumour progression, skin lesions response and angiomyolipoma response. Adverse events were also reported (Franz 2013). se studies reported tumour response to the intervention in terms of the number of participants having a 50% or more reduction of volume of tumours relative to baseline (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

The Koenig study reported the effect of rapamycin on skin lesion appearance. Rapamycin concentrations and complete blood counts (including haemoglobin level and platelet count) were measured. Adverse events were also reported (Koenig 2012). Effects of intervention were measured as the participants' perception on their skin appearance. The participants were asked if they "got better on the treatment", "got worse on the treatment", or if "the treatment made no difference".

Excluded studies

Please refer to the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

A total of 20 studies were excluded from this review. Of these, six studies were non‐randomized without any control group and recruited participants from multiple centres based on TSC diagnostic criteria (Cabrera 2011; Dabora 2011,Davies 2011; Tanaka 2013; Wataya‐Kaneda 2015). A further 14 studies were case series and case reports (Birca 2010; Foster 2012; Franz 2006; Herry 2007; Hofbauer 2008; Koenig 2008; Lam 2010; Pressey 2010; Salido 2012; Sparagana 2010; Staehler 2012; Wataya‐Kaneda 2011; Wienecke 2006; Yalon 2011).

Risk of bias in included studies

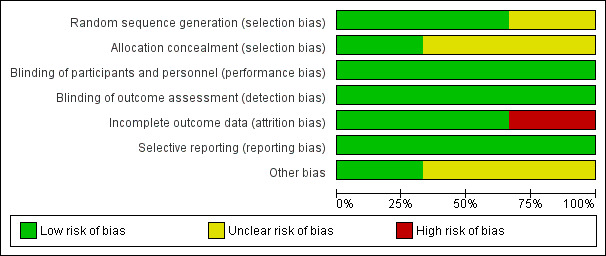

Please refer to Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph illustrating percentages of each risk of bias item for all three included studies (Bissler 2013, Koenig 2008 and Franz 2006).

3.

Risk of bias graph summarizing review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included studies (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013, Koenig 2012).

Allocation

Sequence generation

Two studies described the use of a computer‐generated random sequence and were judged to have a low risk of bias (Franz 2013, Bissler 2013). The Koenig study was judged to have an risk of bias for allocation sequence as no process of generating allocation sequence was described (Koenig 2012).

Allocation concealment

The Franz study described the use of interactive Internet‐response system for allocation concealment and therefore, it was judged as having low risk for allocation concealment (Franz 2013). Allocation concealment was not described in the remaining two studies and was therefore graded as unclear (Bissler 2013; Koenig 2012).

Blinding

Participants and all study personnel (caregiver, investigator and outcomes assessor) were blinded in all three studies and so were assessed as having a low risk of bias (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies were judged to have a low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013). In the Bissler study, efficacy analyses were undertaken on all randomised participants, and safety analyses were undertaken on all participants who received at least one dose of the study drug and had at least one post‐baseline assessment. Participants who were not able to be assessed (either by dropout or for other reasons) were considered as non‐responders (Bissler 2013). Therefore, the risk of bias for incomplete outcome data was low. In the Franz study, efficacy and safety analyses were carried out on all participants, therefore the study was assessed as having low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Franz 2013).

The Koenig study was assessed as having a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data due to the fact that only 23 out of 28 participants were analysed upon completion of the intervention, no information pertaining to which arms the dropouts came from and outcomes were only reported as percentages of participants reporting improvements of their skin lesions on each arm (Koenig 2008).

Selective reporting

Overall, there is a low risk of bias for selective reporting for all studies (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012). For the Franz study, all outcomes recorded in the 'Methods' section were reported in 'Results' section (Franz 2013). The outcomes were response to tumour size, tumour progression, seizure frequency (median change from baseline to week 24), response of treatment to skin lesion and adverse effects (Franz 2013). For the Bissler study, all outcomes mentioned in the 'Methods' section were also reported in the 'Results' section (Bissler 2013). The outcomes included response of treatment to tumour size, tumour progression, response to skin lesion, FEV1, creatinine level, plasma VEGF‐D and collagen IV levels and adverse events (Bissler 2013). For the Koenig study, all outcomes mentioned in the 'Methods' section were also reported in the 'Results' section (Koenig 2012). They reported intervention effect on lesion appearance based on the participants' perception of their skin appearance, complete blood counts and adverse events (Koenig 2012).

Other potential sources of bias

For the Bissler and Franz studies it was noted that the authors who are employees, stock owners or consultants of the funder (Novartis) were involved in the study design, discussion, research, overseeing of data collection and data analysis and interpretation, we assessed this as having an unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings for systemic administration.

| Oral everolimus (rapalog) compared with placebo for people with TSC | |||||||

|

Patient or population: people with TSC Settings: outpatient Intervention: oral everolimus (rapalog) Comparison: placebo | |||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||||

| Placebo | Oral Everolimus (Rapalog) | ||||||

| 50% reduction of tumour size1 | Renal angiomyolipoma | 0 out of 1000 (see comment) |

450 out of 1000 (see comment) |

RR: 24.7 (95% CI 3.5 ‐ 173.4) | 162 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | P = 0.001 0 out of 53 participants in the placebo group and 49 out of 109 participants in the Rapalog group experienced 50% reduction in tumour size. Assumed and corresponding risk are calculated as the event rates in each group. |

| SEGA | 0 out of 1000 (see comment) |

346 out of 1000 (see comment) |

RR: 27.9 (95% CI 1.7 ‐ 444.8) |

117 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | P = 0.02 0 out of 39 participants in the placebo group and 27 out of 78 participants in the Rapalog group experienced 50% reduction in tumour size. Assumed and corresponding risk are calculated as the event rates in each group. |

|

| Response to skin lesions2 | 53 out of 1000 | 307 out of 1000 (122 to 769 out of 1000) | RR: 5.8 (95% CI 2.3 ‐ 14.5) | 224 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | P = 0.0002 | |

| Frequency of seizure | Median change = ‐4.1/24 hr (95% CI ‐10.9 to 5.8) | Median change = ‐2.9/24 hr (95% CI ‐4.1 to ‐1.0) | ‐ | Not reported (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ moderate4 | ‐ | |

| Creatinine level | Increased in 77 out of 1000 participants | Increased in 12 out of 1000 participants (2 to 118 participants) |

RR: 0.16 (95% CI 0.02 ‐ 1.53) | 118 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | ‐ | |

| Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) | See comments | See comments | See comments | See comments | See comments | For the subset of participants with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis the median percentage change of FEV1 in the treatment arm (in 24 out of 79 participants) was ‐1%, while in the placebo arm (10 out of 39 participants) this was ‐4%. | |

| Any adverse events | 897 out of 1000 | 960 out of 1000 (807 to 1000 out of 1000) |

RR: 1.07(0.9‐1.2) | 117 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | P = 0.24 | |

| Adverse Events leading to dose reduction, interruption or withdrawal | 154 out of 1000 | 484 out of 1000 (277 to 770 out of 1000) |

RR: 3.14(1.8‐5.4) | 235 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high3 | P < 0.0001 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the event rate in the placebo group unless otherwise stated in the comments. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; TSC: tuberous sclerosis complex | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||||

This summary of finding table was generated based on analyses from two of the included studies (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013) which used oral (systemic) administration of everolimus (rapalog). Five of the participants from Bissler study were diagnosed with sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (without TSC) which we could not separate from the current analysis (we will attempt to do this for a future update of the review) (Bissler 2013).

1. Response to tumour size is defined as reduction in at least 50% reduction from baseline in sum of volumes of target tumour in participant.

2. Definition of 'response' to skin lesions was not mentioned in the two study analysed (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

3. No downgrading of evidence: High quality of evidences were given even though there are large CIs. The number of participants is relatively large for a rare disease, thus judgement about the quality of evidence (particularly judgements about precision) may be based on the absolute effect. Here the quality rating was considered 'high' because the outcome was appropriately assessed.

4. Downgraded once due to lack of applicability: Most participants had no seizures at baseline or at follow up. Participants were selected for the trial on the basis of their need for intervention for progression of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas rather than presence of seizures (Franz 2013). Further randomised study designed specifically to select people with TSC with seizures may change the outcome.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings for topical administration.

| Topical rapamycin compared with placebo for people with TSC | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with TSC Settings: outpatient Intervention: topical rapamycin Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Topical Rapamycin | |||||

|

Response to skin lesions ‐ rapamycin (6 months) |

38% of participants1 | 73% of participants1 | RR: 1.81 (0.80 ‐ 4.06) | 28 (1) | ⊕⊕ low2 | P = 0.15 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1. The study reported only the percentages. The absolute numbers of responder in each treatment arm were inferred from the percentages. While there are 5 dropouts, no reports on which treatment arm they came from. ITT principle is in effect for the analysis, assuming all participants completed the protocol.

2. We judged the quality of evidence as low due to incomplete outcome data reported from the study (Koenig 2012) and we needed to infer the results from percentages. The evidence is downgraded twice for this reason.

Rapamycin or rapalogs versus placebo

Three studies with a total of 263 participants were included (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

Primary outcome

1. Tumour size

The included studies reported the response of tumour size to oral administration of everolimus in terms of a reduction in the total volume of tumours to 50% or more relative to baseline (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013). The results were presented as dichotomous data as the number of participants experiencing this event in both the treatment and placebo groups.

1.1. Angimyolipoma

Bissler reported that 33 out of 79 participants showed at least a 50% reduction in the size of angiomyolipoma in the treatment group versus none out of 39 in the placebo group (Bissler 2013). Franz reported response to the size of renal angiomyolipomas; 16 out of 30 participants in treatment group versus none of 14 in placebo group showed at least a 50% reduction in angiomyolipoma size (Franz 2013). Our meta‐analysis showed that there was a significant increase in the proportion of participants who achieved a 50% reduction in angiomyolipoma size, RR 24.69 (95% CI 3.51 to 173.41) within the treatment arm (Analysis 1.1).

Given the ITT principle where we analysed all participants enrolled into both studies, it should be noted that five of 79 participants in the Bissler study had sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (without TSC), which we could not separate from the analysis and which we will attempt to do so for a future update of this review (Bissler 2013).

1.2. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA)

1.2.1. Systemic administration

Franz reported a 50% reduction of SEGA volume in 27 out of 78 participants in the treatment group versus none out of 38 participants in the placebo group (Franz 2013). There was a significant increase within the treatment arm in the proportion of participants who achieved a 50% reduction in the volume of SEGA, RR 27.85 (95% CI 1.74 to 444.82) (Analysis 1.1).

Secondary outcomes

1. Response to skin lesions

1.1. Systemic administration

Two studies administered everolimus orally and reported the response to skin lesions; however, these studies did not define 'response' (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013).

Bissler reported 20 participants with a response to skin lesions out of 77 participants in treatment group as compared to no participants among 37 participants in the placebo group (Bissler 2013). Franz reported 30 participants with a response to skin lesions out of 72 participants in the treatment group as compared to four out of 38 participants in placebo group (Franz 2013). We analysed the data from these two studies and found that the proportion of participants who showed a skin response was significantly increased in the treatment arms, RR 5.78 (95% CI 2.30 to 14.52) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Topical administration

One study administered rapamycin topically (skin application), reported a defined response to skin lesions (seeCharacteristics of included studies) (Koenig 2012). The report of five withdrawals were not accompanied by an explanation from which arm the withdrawn participants came. Based on the ITT principle, we analysed this outcome by assuming that all participants completed the protocol.

The effects of the intervention in the Koenig study was measured based on the participants' perception of their skin condition (seeCharacteristics of included studies). While absolute numbers were not reported, it was stated that 73% of participants in the treatment group were said to have improved after treatment, versus 38% in the placebo group (Koenig 2012). We inferred the number of responders in each treatment arm from these percentages and analysed the data (Analysis 2.1). Although there is tendency for improvement in skin lesions in participants who received treatment, it was not significant, RR 1.81 (95% CI 0.80 to 4.06) (P = 0.15).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (topical administration), Outcome 1 Response to skin lesions.

For future updates of the review, we plan to contact the authors of two studies for clarification on the definition of skin response (Bissler 2013;Franz 2013) and type of skin lesions (Bissler 2013;Franz 2013). We also plan to contact the authors of a third study with regards to the absolute number of participants who responded and completed the protocol in each treatment arm (Koenig 2012).

2. Frequency of seizure (times)

One study reported seizure frequency in the form of median seizure frequency at baseline and at week 24 (Franz 2013). The effect of the intervention was reported as the median change of seizure frequency between these time points. However, a large proportion of participants did not experience seizures at baseline. The study reported sensitivity analyses on the subset of participants who had at least one seizure at baseline. The placebo group was reported to have higher median in the baseline of seizure frequency at baseline (11 in 24 hours) compared to treatment group (5.9 in 24 hours). The median change at 24 weeks was ‐2.9 in 24 hours (95% CI ‐4.0 to ‐1.0) in treatment group versus ‐4.1 in 24 hours (95% CI ‐10.9 to 5.8) in placebo group (Franz 2013).

3. Aneurysm size for angiomyolipomas (any unit of analysis found)

None of the included studies reported aneurysm size for angiomyolipomas (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

4. Creatinine level (mg/dL)

One study reported creatinine levels in terms of the number of participants with increased or decreased levels (dichotomous not continuous data) (Bissler 2013). One out of 79 participants in treatment group versus three out of 39 participants in placebo group had increased blood creatinine levels, our analysis showed a non‐significant difference between treatment groups, RR 0.16 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.53) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (systemic administration), Outcome 3 Creatinine levels.

5. Forced expiratory volume at one second (FEV1) / forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio

No study reported analysable data for FEV1 / FVC ratio were not reported. In the Bissler study, only median values at baseline and week 24 for FEV1 were reported. At baseline, the median values were 2.9 the in treatment group versus 2.7 in placebo group, while at week 24, the median values for both groups were 2.7. For the subset of participants with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis the median percentage change of FEV1 in the treatment arm (in 24 out of 79 participants) was ‐1%, while in the placebo arm (10 out of 39 participants) this was ‐4% (Bissler 2013).

6. Any reported adverse effect or toxicity

All included studies reported adverse events during the course of each study, but none were definitely related to tretment (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013; Koenig 2012).

6.1. Systemic administration

Adverse events reported by the two studies which administered everolimus orally, were consistent with the known safety profile of the drug (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013). Adverse events were graded according to the 'Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0' (CTCAE v3.0); most were grade 1 or 2. The most common events in the Franz study were mouth ulceration, stomatitis, convulsion and pyrexia (Franz 2013), and in the Bissler study were nasopharyngitis, acne‐skin lesions, headache, cough and hypercholesterolaemia (Bissler 2013). Franz reported that 75 out of 78 participants within the treatment group and 35 out of 39 participants in the placebo group experienced an adverse events (Franz 2013). Bissler reported the proportion of specific adverse events in both arms (Bissler 2013). An additional table summarises adverse events from 157 participants in the treatment arm and 78 participants in the placebo arm from both studies (Table 3) (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

1. List of adverse events in oral (systemic) administration of everolimus (rapalog).

| Adverse events | Everolimus (n = 157) | Placebo (n = 78) |

| Stomatitis | 69 (44%) | 12 (15%) |

| Nasopahryngitis | 33 (21%) | 21 (27%) |

| Acne‐like skin lesions | 17 (11%) | 2 (3%) |

| Rash | 9 (6%) | 2 (3%) |

| Convulsion | 22 (14%) | 12 (15%) |

| Pyrexia | 22 (14%) | 6 (8%) |

| Headache | 17 (11%) | 8 (10%) |

| Cough | 26 (17%) | 9 (12%) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 16 (10%) | 1 (1%) |

| Aphthous stomatitis | 17 (11%) | 4 (5%) |

| Fatigue | 25 (16%) | 8 (10%) |

| Mouth ulceration | 41(26%) | 4 (5%) |

| Nausea | 13(8%) | 5 (6%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 12(8%) | 6 (8%) |

| Bronchitis | 11(7%) | 5 (6%) |

| Otitis media | 9 (6%) | 3 (4%) |

| Pharyngitis | 8 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Vomiting | 26 (17%) | 7 (9%) |

| Anaemia | 10 (6%) | 1 (1%) |

| Arthralgia | 10 (6%) | 2 (3%) |

| Diarrhoea | 20 (13%) | 4 (%) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (6%) | 4 (5%) |

| Blood lactate dehydrogenase increased | 9 (6%) | 2 (3%) |

| Hypophosphataemia | 9 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Eczema | 8 (5%) | 3 (4%) |

| Leucopenia | 8 (5%) | 3 (4%) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 8 (5%) | 4 (5%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 21 (13%) | 9 (12%) |

Data were analysed from two studies (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

We analysed total adverse event data from only one of the included studies (Franz 2013) and found the participants who received oral everolimus treatment had a similar risk of experiencing adverse events as compared to those who did not receive treatment, RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.20) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Rapamycin or rapalogs vs placebo (systemic administration), Outcome 4 Any adverse events.

Oral everolimus treatment lead to significantly more adverse events resulting in withdrawal, interruption in treatment, or a reduction in dose level, RR 3.14 (with 95% confidence interval 1.82 to 5.42) (P < 0.0001) (Analysis 1.5) (Bissler 2013; Franz 2013).

6.2. Topical administration

The Koenig study, which administered rapamycin topically, reported that one participant from the treatment group experienced a serious adverse event, albeit unrelated to the study treatment (Koenig 2012). The participant aspirated during a seizure and developed pneumonia, which progressed to septic shock. The rapamycin concentrations were undetectable at the time of hospital admission, and the participant was immediately withdrawn from the study. This study did not list specific adverse events in the participants; however, the authors reported that there were no serious adverse events related to the study product and there was no detectable systemic absorption of the rapamycin during the study period (Koenig 2012).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Significantly more participants with angiomyolipoma who received oral everolimus (rapalog) had at least a 50% reduction in tumour size compared to those receiving placebo. Similarly, more participants with subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) who received oral everolimus (rapalog) had at least a 50% reduction in tumour volume compared to those receiving placebo.

Two studies reported a significant increase in the chance of showing a response to skin lesions with oral everolimus (rapalog) (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013). However, the response of skin lesions to topical rapamycin showed a tendency to improvement, although this was not significant (Koenig 2012).

The effect of oral everolimus (rapalog) on seizure frequency was reported in one study, but the outcome was inconclusive (Franz 2013). These observations were based on the median values of seizure reduction, rather than the mean; probably because the data for this outcome was skewed (i.e. most participants might have had experienced a few seizures but a small number of participants may have experienced many) which will change the distribution of the data (the median would be a more appropriate statistic to use in this case). Moreover, participants were selected for the study on the basis of their need for intervention for progression of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas rather than presence of seizures. Further clarifications from the trial authors will be sought on this for a future update of the review.

One study reported an effect of oral everolimus (rapalog) on serum creatinine, were more participants in the placebo group were found to have elevated levels of serum creatinine compared to those in the intervention arm (Bissler 2013).

For a subset of participants with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis, after 24 weeks, the median percentage reduction in FEV1 was greater in the placebo group than in the oral everolimus (rapalog) group (Bissler 2013).

Although our analysis on one of the included studies showed that participants who received oral everolimus (rapalog) had a similar risk of having adverse events as compared to participants who did not (Franz 2013), the treatment itself led to significantly more adverse events resulting in withdrawal, an interruption in treatment, or a reduction in dose level (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013). Nevertheless, these are adverse events of which correlation to the treatment per se is not certain. No serious adverse events related to the topical rapamycin administration were reported and there was no detectable systemic absorption during the study period (Koenig 2012)

The findings were summarized in the table (Table 1; Table 2).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We identified three studies meeting our inclusion criteria and including outcomes of interest to this review. However, the objective of correlating intervention to adverse effects was not satisfactorily met, as most of the manifestations were observed as adverse events and not specifically treatment‐related adverse effects. It should be noted that small proportions of the participants (five of 162) analysed for renal angiomyolipoma have sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (without tuberous sclerosis complex).

Quality of the evidence

Two of the included studies generally showed a low risk of bias (Bissler 2013, Franz 2013), except for an unclear risk in one study with no information on allocation concealment (Bissler 2013). Another included study showed a range of risk of biases across domains, where we judged this study to have high risk of attrition bias, unclear allocation concealment and unclear random sequence generation (Koenig 2012). The reporting outcomes across studies was generally of high quality, except for the response to skin lesions from topical rapamycin due to the attrition bias of the study and seizure frequency due to selection of participants. Evidence for an effect on skin lesions from topical rapamycin requires more data. Evidence for seizure frequency was inconclusive. The evidence was of high quality in relation to response to tumour size, even though there are large confidence intervals. The number of participants is relatively large for a rare disease, thus judgement about the quality of the evidence (particularly judgements about precision) may be based on the absolute effect. Here the quality rating was considered 'high' because the outcome was appropriately assessed.

Potential biases in the review process

The strengths of this review are based on the careful selection of randomised studies of a rare disease. We have noted that not all relevant data could be obtained, especially those data relating to adverse effects.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review on non‐randomised studies carried out by this author team showed similar findings, where absolute tumour size reduction was noted in people treated with rapamycin or rapalogs (Sasongko 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Convincing evidence of a reduction of tumour size after 24 weeks of treatment with oral everolimus (rapalogs) in both renal angiomyolipoma and SEGA would provide sufficient evidence for its use in clinical practice as the benefits outweigh the risks. With this in mind, and with the positive effects on the size reduction in renal angiomyolipoma and SEGA, this review concurs with the decision of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicine Agency (EMA) on the use of everolimus for both types of tumours. Rapamycin or rapalogs may also have a beneficial effect on skin lesions.

Implications for research.