Abstract

Background

Surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic and periampullary cancer. A considerable proportion of patients undergo unnecessary laparotomy because of underestimation of the extent of the cancer on computed tomography (CT) scanning. Laparoscopy can detect metastases not visualised on CT scanning, enabling better assessment of the spread of cancer (staging of cancer). This is an update to a previous Cochrane Review published in 2013 evaluating the role of diagnostic laparoscopy in assessing the resectability with curative intent in people with pancreatic and periampullary cancer.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy performed as an add‐on test to CT scanning in the assessment of curative resectability in pancreatic and periampullary cancer.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE via OvidSP (from inception to 15 May 2016), and Science Citation Index Expanded (from 1980 to 15 May 2016).

Selection criteria

We included diagnostic accuracy studies of diagnostic laparoscopy in people with potentially resectable pancreatic and periampullary cancer on CT scan, where confirmation of liver or peritoneal involvement was by histopathological examination of suspicious (liver or peritoneal) lesions obtained at diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy. We accepted any criteria of resectability used in the studies. We included studies irrespective of language, publication status, or study design (prospective or retrospective). We excluded case‐control studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed data extraction and quality assessment using the QUADAS‐2 tool. The specificity of diagnostic laparoscopy in all studies was 1 because there were no false positives since laparoscopy and the reference standard are one and the same if histological examination after diagnostic laparoscopy is positive. The sensitivities were therefore meta‐analysed using a univariate random‐effects logistic regression model. The probability of unresectability in people who had a negative laparoscopy (post‐test probability for people with a negative test result) was calculated using the median probability of unresectability (pre‐test probability) from the included studies, and the negative likelihood ratio derived from the model (specificity of 1 assumed). The difference between the pre‐test and post‐test probabilities gave the overall added value of diagnostic laparoscopy compared to the standard practice of CT scan staging alone.

Main results

We included 16 studies with a total of 1146 participants in the meta‐analysis. Only one study including 52 participants had a low risk of bias and low applicability concern in the patient selection domain. The median pre‐test probability of unresectable disease after CT scanning across studies was 41.4% (that is 41 out of 100 participants who had resectable cancer after CT scan were found to have unresectable disease on laparotomy). The summary sensitivity of diagnostic laparoscopy was 64.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 50.1% to 76.6%). Assuming a pre‐test probability of 41.4%, the post‐test probability of unresectable disease for participants with a negative test result was 0.20 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.27). This indicates that if a person is said to have resectable disease after diagnostic laparoscopy and CT scan, there is a 20% probability that their cancer will be unresectable compared to a 41% probability for those receiving CT alone.

A subgroup analysis of people with pancreatic cancer gave a summary sensitivity of 67.9% (95% CI 41.1% to 86.5%). The post‐test probability of unresectable disease after being considered resectable on both CT and diagnostic laparoscopy was 18% compared to 40.0% for those receiving CT alone.

Authors' conclusions

Diagnostic laparoscopy may decrease the rate of unnecessary laparotomy in people with pancreatic and periampullary cancer found to have resectable disease on CT scan. On average, using diagnostic laparoscopy with biopsy and histopathological confirmation of suspicious lesions prior to laparotomy would avoid 21 unnecessary laparotomies in 100 people in whom resection of cancer with curative intent is planned.

Keywords: Humans; Ampulla of Vater; Unnecessary Procedures; Common Bile Duct Neoplasms; Common Bile Duct Neoplasms/diagnostic imaging; Common Bile Duct Neoplasms/pathology; Common Bile Duct Neoplasms/surgery; Laparoscopy; Laparoscopy/methods; Laparotomy; Laparotomy/statistics & numerical data; Neoplasm Staging; Neoplasm Staging/methods; Pancreatic Neoplasms; Pancreatic Neoplasms/diagnostic imaging; Pancreatic Neoplasms/pathology; Pancreatic Neoplasms/surgery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tomography, X‐Ray Computed

Plain language summary

What is the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopic staging following a CT scan for assessing whether pancreatic and periampullary cancer is resectable?

Background

The pancreas is an organ situated in the abdomen close to the junction of the stomach and small bowel. It secretes digestive juices which are necessary for the digestion of all food materials. The digestive juices secreted in the pancreas drain into the upper part of the small bowel via the pancreatic duct. The bile duct is a tube which drains bile from the liver and gallbladder. The pancreatic and bile ducts share a common path just before they drain into the small bowel. This area is called the periampullary region. Surgical removal is the only potentially curative treatment for cancers arising from the pancreatic and periampullary regions. A considerable proportion of patients undergo unnecessary major open abdominal exploratory operation (laparotomy) because their CT scan has underestimated the spread of cancer. If during the major open operation the cancer is found to have spread within the abdomen, patients are referred for alternate treatments such as chemotherapy, which do not cure the cancer but may improve survival.

This major open abdominal operation can be avoided if the spread of cancer within the abdomen is known, called 'staging' the cancer. The minimum test used for staging is usually the computed tomography (CT) scan. However, CT scan can understage the cancer, that is it can underestimate the spread of cancer. Laparoscopy, a procedure whereby a small telescope is inserted inside the abdomen through a small (keyhole) surgical incision, can detect spread not identified on CT scanning. Different studies report different accuracy of laparoscopy in assessing whether the cancer can be removed. Our aim therefore was to find out the average diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy for staging pancreatic and periampullary cancers considered to be removable after a CT scan. This review is an update of our previous review.

A glossary of terms is provided in Appendix 1.

Study characteristics

We performed a thorough literature search to identify studies published up to 15 May 2016. We identified 16 studies reporting information on 1146 people with pancreatic or periampullary cancers which were considered to be eligible for potentially curative surgery based on CT scan staging. These studies evaluated diagnostic laparoscopy and compared results of the procedure with the eventual diagnosis by the surgeon that the cancer was not resectable during major abdominal operation or examination under microscope.

Quality of evidence

All of the studies were of unclear or low methodological quality in one or more aspects, which may undermine the validity of our findings.

Key results

Of those people with what CT suggests seems to be a potentially surgically curable cancer, the percentage in whom more extensive cancer was found on further staging with diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy ranged between 17% and 82% across studies. The median percentage of people in whom cancer spread was not detected by CT scan was 41%. Adding staging laparoscopy to CT scan might decrease the number of people with unremovable disease undergoing unnecessary major operations to 20% compared to those who undergo unnecessary major operation after CT scan alone (41%). This means that using diagnostic laparoscopy could halve the rate of unnecessary major open operations in people undergoing major surgery for potentially surgically curable pancreatic cancer.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Diagnostic laparoscopy.

| Population | Males and females aged 15 to 87 years with potentially resectable pancreatic or periampullary carcinoma on computed tomography (CT) scanning | |

| Setting | Surgical centres in the USA, Germany, the UK, Japan, Israel, and the Netherlands | |

| Index test | Diagnostic laparoscopy with histologic confirmation | |

| Reference standard | Paraffin section histology on diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy or surgeon's judgement of unresectability on laparotomy True positive: Suspicious lesion on diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed to be cancer by a histopathological examination of biopsy obtained during diagnostic laparoscopy False positive: This is not possible since laparotomy will only be performed if histopathology of the biopsy of the suspicious lesion on diagnostic laparoscopy shows no evidence of cancer False negative: No evidence of unresectability by diagnostic laparoscopy but evidence of unresectability on laparotomy True negative: No evidence of unresectability by diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy |

|

| Number of studies | 16 studies | |

| Summary sensitivity | 64.4% (95% confidence interval 50.1% to 76.6%) | |

| Consistent results | No | |

| Uncertainty (overall risk of bias) | High | |

| Other limitations | Different definitions of unresectability because studies used surgeon's judgement of unresectability on laparotomy when biopsy confirmation was not possible | |

| Pre‐test probability from included studies1 | Post‐test probability of unresectable disease for patients with a negative test result (95% confidence interval)2 | Percentage of patients for whom unnecessary laparotomy can be avoided3 |

| Minimum = 17.4 | 7.0 (4.9 to 9.8) | 10.4 |

| Lower quartile = 34.7 | 15.9 (11.4 to 21.6) | 18.8 |

| Median = 41.4 | 20.1 (14.7 to 26.8) | 21.3 |

| Upper quartile = 62.7 | 37.4 (29.0 to 46.6) | 25.3 |

| Maximum = 81.8 | 61.5 (52.3 to 70.0) | 20.3 |

| Interpretation | At pre‐test probabilities of 17%, 41%, and 82%, adding diagnostic laparoscopy to CT scan for the preoperative staging of pancreatic cancer avoids 10, 21, and 20 unnecessary laparotomies out of 100 laparotomies performed for curative resection purposes. These pre‐test probabilities are the minimum, middle, and maximum values obtained from the included studies | |

1Probability of someone having unresectable disease at laparotomy after CT indicated that the disease is resectable. 2Probability of someone having unresectable disease after the CT and diagnostic laparoscopy indicated that the disease is resectable. 3Calculated as the difference between the post‐test probability and the pre‐test probability.

All probabilities are reported in the table as percentages.

Background

Periampullary cancer develops near the ampulla of Vater (National Cancer Institute 2011a). This includes cancer of the head and neck of the pancreas, cancer of the distal end of the bile duct, cancer of the ampulla of Vater, and cancer of the second part of the duodenum. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the main treatment for cancers arising in the head of the pancreas, ampulla, and second part of the duodenum. Surgical resection is generally considered to be the only cure for pancreatic cancer. However, only 15% to 20% of people with pancreatic cancers undergo potentially curative resection (Conlon 1996; Engelken 2003; Michelassi 1989; Shahrudin 1997; Smith 2008). In all other people, the cancers are not resected because of infiltration of local structures, disseminated disease, or because the person is deemed unfit to undergo major surgery. Computed tomography (CT scan) is generally used for staging pancreatic and periampullary cancers (National Cancer Institute 2011b). Despite undergoing routine CT scanning to stage the disease (Mayo 2009), a substantial proportion of patients (approximately 10% to 25%) undergo unnecessary laparotomy (opening the abdomen using a large incision) with lack of curative resectability identified only during the laparotomy (Lillemoe 1999; Mayo 2009). Laparoscopy can be used to detect metastatic disease in people with periampullary cancer.

Target condition being diagnosed

Inability to perform curative resectability of pancreatic and periampullary cancer ('unresectable' cancers)

Index test(s)

Diagnostic laparoscopy involves the use of a laparoscope (a telescope inserted into the abdominal cavity through a keyhole incision) to visualise and explore the abdominal organs. Also known as staging laparoscopy, it is used following initial staging by CT scanning. Any spread of cancer to the liver, peritoneum, or adjacent structures can be visualised during diagnostic laparoscopy. A biopsy of the suspicious lesion can be performed, and the biopsy specimen can be examined under the microscope to confirm that the suspicious lesion is spread of cancer.

Clinical pathway

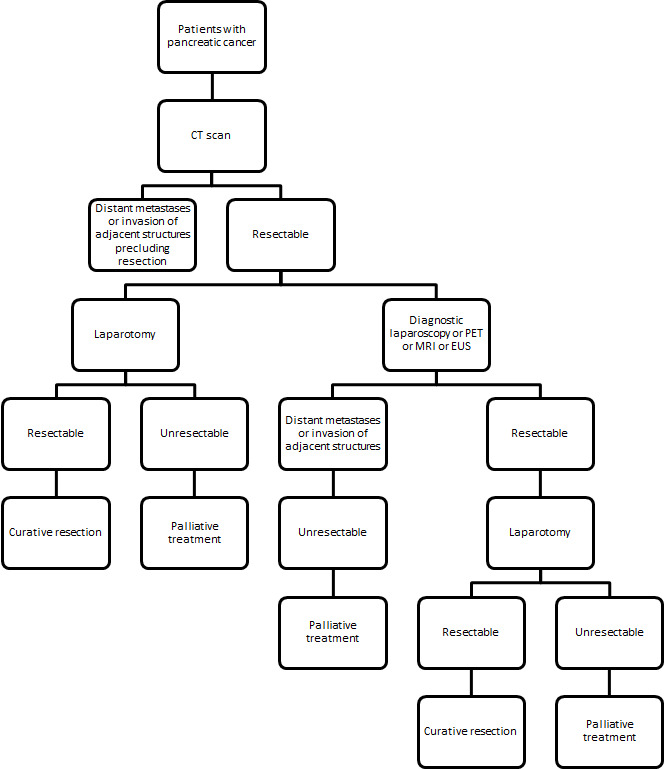

No standard algorithm is currently available for assessing the resectability of pancreatic and periampullary cancers, with clinicians following their own algorithms based on either their clinical experience or education. Almost all current algorithms include a CT scan as one of the tests (National Cancer Institute 2011b). CT may be the only test performed before laparotomy. Other tests such as diagnostic laparoscopy, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may be used in addition to CT scan to assess resectability. The possible clinical pathway in the staging of pancreatic cancers is shown in Figure 1. Another review is assessing the accuracy of these various tests and CT scanning (Gurusamy 2015).

1.

Clinical pathway.

EUS: endoscopic ultrasound MRI: magnetic resonance imaging PET: positron emission tomography

Prior test(s)

The minimum prior test should be CT, and the cancer should be resectable with curative intent on the basis of the CT scan to be included in this review. Other tests such as PET scanning, MRI, or EUS might be used in addition to CT scanning to assess resectability prior to diagnostic laparoscopy. We included participants in this review irrespective of whether they underwent these other tests prior to diagnostic laparoscopy.

Role of index test(s)

Diagnostic laparoscopy can be considered as an add‐on test to the CT scan prior to laparotomy done with the intention of performing a potentially curative resection.

Alternative test(s)

Other tests such as PET scanning, laparoscopic ultrasound, or EUS may be used as alternative tests to diagnostic laparoscopy in people considered to have CT resectable pancreatic and periampullary cancer. As mentioned earlier, PET scanning and EUS may also be used prior to diagnostic laparoscopy. Laparoscopic ultrasound may be used in combination with diagnostic laparoscopy, and the strategy for determining test positivity of the combination may be either test positive or both tests positive.

Rationale

Diagnostic laparoscopy allows internal visualisation of the abdomen and can detect any peritoneal spread of the cancer or the involvement of any adjacent structures. A biopsy and histopathological examination of any suspicious lesion can be performed and an unnecessary laparotomy to attempt curative resection avoided. If this add‐on test can identify unresectable cancers without laparotomy, it might decrease the costs and morbidity associated with unnecessary laparotomy. This is an update to an earlier Cochrane Review assessing the resectability with curative intent in pancreatic and periampullary cancer published in 2013 (Allen 2013).

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy performed as an add‐on test to CT scanning in the assessment of curative resectability in pancreatic and periampullary cancer.

Secondary objectives

We planned to explore the following sources of heterogeneity.

Studies at low risk of bias versus those at unclear or high risk of bias based on methodological quality assessment using the QUADAS‐2 tool (Whiting 2011).

Full‐text publications versus abstracts (this can inform about publication bias since there may be an association between the results of the study and the study reaching full publication status) (Eloubeidi 2001).

Prospective studies versus retrospective studies.

Proportion of participants with pancreatic cancer, ampullary cancer, and bile duct cancers (although classified as periampullary cancers, each has a different prognosis) (Klempnauer 1995). The additional value of diagnostic laparoscopy may be different because of the extent of spread in these different types of periampullary cancers.

Procedures performed under the same anaesthetic versus procedures performed under a different anaesthetic (there are likely to be differences in the histopathological examinations since the former procedure is associated with frozen section biopsy, while the latter procedure is likely to be associated with paraffin section). Paraffin section is considered to be the gold standard in identifying cancer. Frozen sections can be associated with false‐negative results (Yeo 2002). However, frozen section results are always confirmed by paraffin section histological examinations.

Different definitions for resectable cancer on laparotomy. Different surgeons may consider cancer unresectable differently, i.e. they will have different criteria for unresectability on laparotomy (other than the consensus criteria for resectability). For example, one surgeon may judge that the cancer is unresectable on laparotomy because of the involvement of the vessel and consider the reference standard to be positive. This will result in a false‐negative result for laparoscopy. Another surgeon may judge the same cancer to be resectable despite the involvement of the vessel and proceed with resection. The reference standard will be negative in this situation, resulting in a true‐negative result for laparoscopy. This might have an intrinsic threshold effect.

Additional pre‐tests performed (besides CT scan). This can alter the pre‐test probability of unresectability and can help in the assessment of the additional value of diagnostic laparoscopy under various situations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that evaluated the accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy in the appropriate patient population (see below) irrespective of language or publication status, or whether data were collected prospectively or retrospectively. However, we excluded case reports which did not provide sufficient diagnostic test accuracy data. We also excluded case‐control studies, which are prone to bias (Whiting 2011).

Participants

People about to undergo curative resection for pancreatic and periampullary cancer with no contraindications (such as metastatic disease) for curative resection on CT scan, and who were anaesthetically fit to undergo major surgery.

Index tests

We included only diagnostic laparoscopy in which histopathological confirmation of metastatic spread was obtained on a paraffin section.

Target conditions

The target conditions were unresectable pancreatic and periampullary cancers, that is diagnostic laparoscopy was considered to be a positive test if the pancreatic or periampullary cancer was unresectable. In these cancers it is not possible to perform curative resectability. There are no uniform criteria for resectability of pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Consensus exists for the definition of borderline resectable cancers (Abrams 2009). Therefore, where there is less tissue involvement than in a borderline resectable cancer, the tumour can be considered as resectable. We accepted any criteria of resectability used by the study authors and acknowledge that this could potentially create a threshold effect. In general, the cancer would not be resected if liver or peritoneal metastases were noted, or if the cancer had invaded important adjacent blood vessels that are beyond the criteria for borderline resectable cancers, for example greater than 180° involvement of the superior mesenteric artery.

Reference standards

Confirmation of liver or peritoneal involvement by histopathological examination of suspicious (liver or peritoneal) lesions obtained at diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy. We accepted only paraffin section histology as the reference standard. In clinical practice, depending on the urgency of the results, a frozen section biopsy may be done to obtain immediate results. However, this is always confirmed by subsequent paraffin section histology (which can take several days) because frozen section biopsy is not as reliable as paraffin section histology. We also accepted the surgeon's judgement of unresectability at laparotomy when biopsy confirmation was not possible. For example, if the tumour has invaded the adjacent blood vessels the surgeon may not resect the tumour because of the danger posed by resecting part of a large blood vessel, and so biopsy confirmation cannot be obtained.

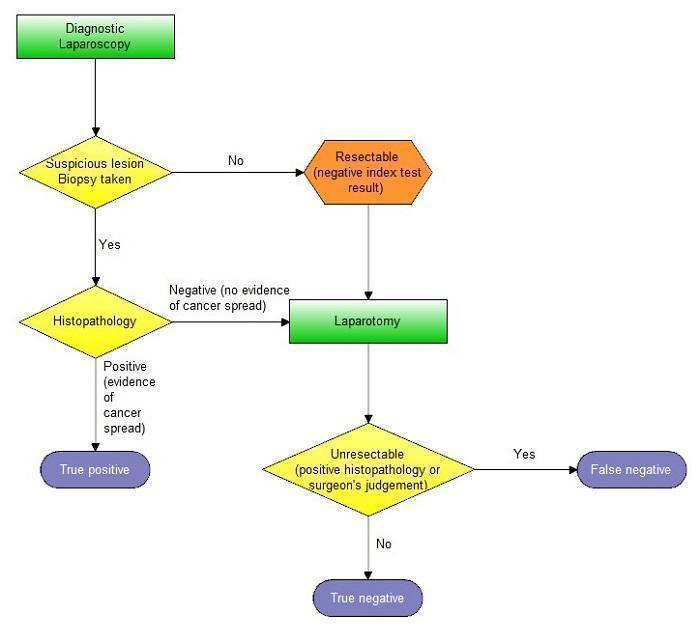

Diagnostic laparoscopy results versus reference standard results

A schematic diagram of the results of diagnostic laparoscopy against those of histopathology or laparotomy is shown in Figure 2. Positive histopathology of a biopsy taken during diagnostic laparoscopy confirms the presence of cancer (true positive). Thus, the index test and the reference standard are one and the same if there is positive histopathology after laparoscopy. As a result, false positives are not possible, and there is no sampling error associated with specificity because it is by definition equal to 1. If the histopathology is negative, the surgeon will perform a laparotomy. The cancer may be resectable with curative intent (true negative) or may not be resectable with curative intent (false negative) based on histopathological confirmation or the surgeon's judgement of unresectability on laparotomy if biopsy confirmation cannot be obtained.

2.

Schematic diagram indicating how true‐positive, false‐negative, and true‐negative test results were determined.

Search methods for identification of studies

We included all studies irrespective of language of publication and publication status. We obtained translations of any non‐English articles.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases until 15 May 2016.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issue 5, 2016) (Appendix 2).

MEDLINE via PubMed (January 1946 to May 2016) (Appendix 3).

EMBASE via OvidSP (January 1947 to May 2016) (Appendix 4).

Science Citation Index Expanded (January 1980 to May 2016) (Appendix 5).

Searching other resources

We searched the references of the included studies to identify additional studies. We also searched for articles related to the included studies by performing the 'related search' function in MEDLINE (PubMed) and EMBASE (OvidSP) and a 'citing reference' search (by searching the articles which cited the included articles) in Science Citation Index Expanded and EMBASE (OvidSP) (Sampson 2008).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (VA and KG or AK) independently searched the references to identify relevant studies. We obtained the full texts for references considered relevant by at least one of the review authors. Two review authors screened the full‐text papers against the inclusion criteria. Any differences in study selection were arbitrated by BRD.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted the following data from each included study, resolving any differences by discussion with BRD.

First author.

Year of publication.

Study design (prospective or retrospective; cross‐sectional studies or randomised clinical trials).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for individual studies.

Total number of participants.

Number of females.

Average age of the participants.

Type of cancer (i.e. head and neck of pancreas, body and tail of pancreas, ampullary cancers, cancer of the lower end of the bile duct).

Criteria for unresectability at diagnostic laparoscopy (index test) and at laparotomy (reference standard).

Preoperative tests carried out prior to diagnostic laparoscopy.

Description of the index test.

Reference standard.

Number of true positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Complications of diagnostic laparoscopy.

The unit of analysis was the participant, meaning that if multiple metastases were found in a participant with a negative index test, the number of false negatives was considered to be one. This is because it is the presence rather than the number of metastases which is important in determining the curative resectability of patients. We considered participants with uninterpretable diagnostic laparoscopy results (no matter the reason given for lack of interpretation) as negative for the test since in clinical practice laparotomy would be carried out on these patients. However, we included such participants in the analysis only if the results of laparotomy were available. We sought further information from study authors if necessary.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two review authors (VA and KG) independently assessed study quality using the QUADAS‐2 assessment tool (Whiting 2011). Any differences were resolved by BRD. The criteria used to classify the different studies are shown in Table 2. We considered studies which were classified as 'low risk of bias' and 'low concern' in all the domains as having high methodological quality.

1. QUADAS‐2 classification.

| Domain 1: Patient selection | Patient sampling | Patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer considered eligible for surgical resection following a CT scan |

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes: If a consecutive sample or a random sample of patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer eligible for surgical resection after CT scan was included in the study No: If a consecutive sample or a random sample of patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer eligible for surgical resection after CT scan was not included in the study Unclear: If this information was not available | |

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes: If a cohort of patients about to undergo surgical resection were studied

No: If patients who underwent unsuccessful laparotomy (cases) were compared with patients who underwent successful surgical resection (controls). Such studies were excluded

Unclear: We anticipated that we would be able to determine whether the design was case‐control As anticipated, we were able to determine the study design and were able to exclude all case‐control studies. So, all studies included in this review were classified as 'yes' for this item |

|

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes: If all patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer eligible for surgical resection were included No: If the study excluded patients based on high probability of resectability (for example, small tumours) Unclear: If this information was not available | |

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | Low risk of bias: If 'yes' classification for all the above 3 questions; high risk of bias: if 'no' classification for any of the above 3 questions; unclear risk of bias: if 'unclear' classification for any of the above 3 questions but without a 'no' classification for any of the above 3 questions | |

| Patient characteristics and setting | Yes: We included only patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer who were considered eligible for surgical resection following a CT scan. So, we anticipated all the included studies to be classified as 'yes' No: We excluded studies where patients were considered unsuitable for surgery after a CT scan. So, we did use this classification Unclear: We excluded studies in which it was not clear whether the patients had undergone CT scan following which they were still considered suitable for surgical resection | |

| Are there concerns that the included patients and setting do not match the review question? | Considering the inclusion criteria of this review, we anticipated that all of the included studies would be classified as 'low concern'. However, this was not the case, as shown in Figure 3 | |

| Domain 2: Index test | Index test(s) | Diagnostic laparoscopy with histologic confirmation of metastases |

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | The index test would always be conducted and interpreted before the reference standard. So, this classification was always 'yes' | |

| If a threshold was used, was it prespecified? | Not applicable | |

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | We anticipated classifying all studies as 'low risk of bias' because diagnostic laparoscopy indicates that structures within the abdomen were inspected, diagnostic laparoscopy would be conducted and interpreted before reference standard, and because we excluded any studies without histological confirmation of the metastatic spread As anticipated, all of the studies were classified as 'low risk of bias' for this domain |

|

| Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Considering the inclusion criteria for this review, we anticipated that all of the included studies will be classified as 'low concern' As anticipated, all of the studies were classified as 'low concern' for this domain |

|

| Domain 3: Target condition and reference standard | Target condition and reference standard(s) | Unresectability. The reasons for unresectability include involvement of adjacent structures or distant metastases. There is currently no universal criteria for unresectability. Consensus exists for the definition of borderline resectable cancers (Abrams 2009). Therefore where there is less tissue involvement than in a borderline resectable cancer, the tumour can be considered as resectable Positive reference standard: Confirmation of liver or peritoneal involvement by histopathological examination of suspicious (liver or peritoneal) lesions (irrespective of how the tissues were obtained for histopathological examination). We accepted only paraffin section histology as the reference standard. We also accepted the surgeon's judgement of unresectability on laparotomy when biopsy confirmation was not possible (e.g. the surgeon may not resect the tumour if it invaded the adjacent blood vessels but will not obtain a biopsy confirmation of this because of the danger posed by resecting a part of a large blood vessel) Negative reference standard: Cancer was fully resected, i.e. clear resection margins on histology |

| Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes: If histological confirmation of distant spread or local infiltration of adjacent structures making the cancer unresectable was obtained. The report on the resection margins showed clearly that the cancer was completely resected. We did not anticipate that any studies would meet these criteria because of the danger that biopsy of infiltration of adjacent structures poses

No: If resection margins were not clear of cancer

Unclear: If surgeon's judgement was used to assess unresectability or if the information about the resection margins was not available. We anticipated that most studies would be classified as 'unclear' because surgeon's judgement is generally used as a criterion for unresectability in clinical practice As anticipated, all of the studies were classified as 'unclear' for this item |

|

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | It is not possible to perform the reference standard without knowledge of the results of the index test. However, only patients with suspicious lesions on laparoscopy undergo biopsy, and only patients with negative laparoscopy would undergo laparotomy. The results of the index test are unlikely to influence the results of the reference standard. All studies were classified as 'no' for this question | |

| Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Risk of bias was determined as 'low' if the answer to the first question was 'yes', 'high' if the answer to the first question was 'no', and 'unclear' if the answer to the first question was 'unclear' | |

| Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the question? | Considering the inclusion criteria for this review, we anticipated that all of the included studies would be classified as 'low concern' As anticipated, all of the studies were classified as 'low concern' for this domain |

|

| Domain 4: Flow and timing | Flow and timing | The cancer may progress if there is long time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy. So, we chose an arbitrary time interval of 2 months as an acceptable time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy |

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes: If the time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy was less than 2 months No: If the time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy was more than 2 months Unclear: If the time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy was unclear | |

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes: If all of the patients received the same reference standard (we anticipated that all the studies would be classified as 'yes')

No: If different patients received different reference standards Unclear: If this information was not clear |

|

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes: If all of the patients were included in the analysis irrespective of whether the results were uninterpretable No: If some patients were excluded from the analysis because of uninterpretable results Unclear: If this information was not clear | |

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | Low risk of bias: if 'yes' classification for all of the above 3 questions; high risk of bias: if 'no' classification for any of the above 3 questions; unclear risk of bias: if 'unclear' classification for any of the above 3 questions but without a 'no' classification for any of the above 3 questions |

CT: computed tomography

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

The index test used was diagnostic laparoscopy with biopsy and histopathological confirmation. For the reason mentioned earlier, false positives were not possible. We therefore performed meta‐analysis of only sensitivities by using a univariate random‐effects logistic regression model. The analysis was done using the NLMIXED procedure in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) (Appendix 6). We used the ESTIMATE statement in NLMIXED to obtain the negative likelihood ratio by using a function of the estimated summary sensitivity and a specificity of 1. The median pre‐test probability of unresectability was calculated from the pre‐test probabilities of the included studies. We calculated the proportion of participants classified as having resectable disease by CT scanning and diagnostic laparoscopy who were actually found to be unresectable at laparotomy (post‐test probability) using the median pre‐test probability and the negative likelihood ratio (see Appendix 7 for details). The difference in the unresectability proportions (post‐test probability minus pre‐test probability) gave the overall added value of diagnostic laparoscopy compared to the standard practice of CT scan staging alone.

Investigations of heterogeneity

We planned to explore heterogeneity by using the different sources of heterogeneity as covariate(s) in the regression model. However, this was not possible because the information was either not available or was the same in all the studies.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not plan any sensitivity analyses.

Results

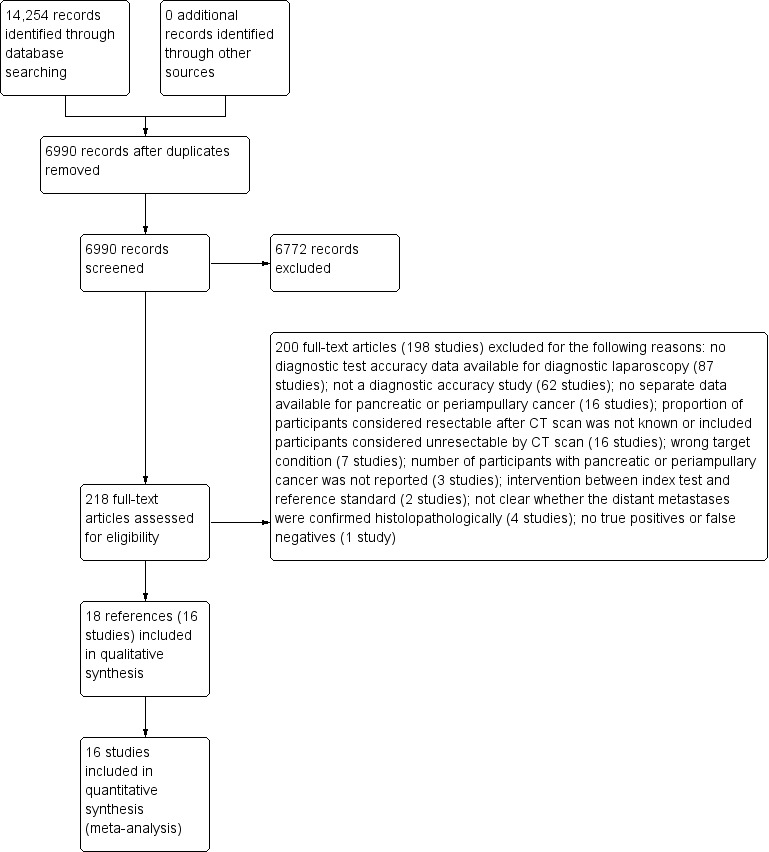

Results of the search

We identified a total of 14,254 references through the electronic searches of the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group Controlled Trials Register and CENTRAL (n = 191), MEDLINE (n = 5228), EMBASE (n = 4460), and Science Citation Index (n = 4375). Figure 4 shows the flow of references through the selection process. We excluded 7264 duplicates and clearly irrelevant references through reading the abstracts. We retrieved 213 references for further assessment. We identified no references through scanning reference lists of the identified studies. Of the 213 references, we excluded 194 for the reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. In one study (Hashimoto 2015), all 11 participants who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy had resectable pancreatic cancers. There were therefore no true positives and false negatives for estimation of sensitivity, and we excluded this study from the review. We included 18 references of 16 studies.

4.

Flow diagram of study selection.

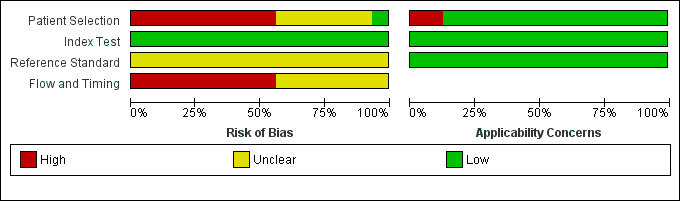

Methodological quality of included studies

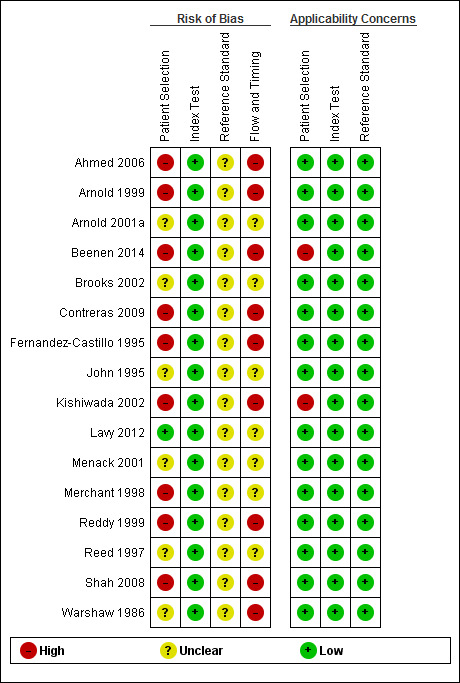

The methodological quality of the included studies is shown in the Characteristics of included studies table, Figure 5, and Figure 3.

5.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study.

There was a high risk of bias regarding the selection of participants in most studies (Ahmed 2006; Arnold 1999; Arnold 2001a; Beenen 2014; Brooks 2002; Contreras 2009; John 1995; Kishiwada 2002; Lavy 2012; Menack 2001; Merchant 1998; Reddy 1999; Reed 1997; Shah 2008; Warshaw 1986). This was because the studies did not explicitly state whether a consecutive or random sample of patients was recruited or whether they had made inappropriate exclusions. Only one study had low risk of bias and low applicability concerns regarding the selection of participants (Fernandez‐Castillo 1995).

There were no risk of bias issues or concerns regarding applicability of the index test in any of the studies, as was anticipated (Table 2).

As anticipated, it proved impossible to determine whether an appropriate reference standard was used. This is because even in the presence of predefined criteria for unresectability, it may not be ethical to biopsy and confirm that the tumour has invaded the blood vessels because of the risk of major bleeding. Thus it was not possible to determine whether the cancer was truly unresectable. None of the studies reported whether the margins of the resected lesions were clear of cancer. It was therefore not possible to determine whether the cancer was truly resectable with curative intent.

None of the studies reported the time interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy. In addition, many studies had excluded some patients inappropriately. All of the studies were therefore at unclear or high risk of bias in the flow and timing domain.

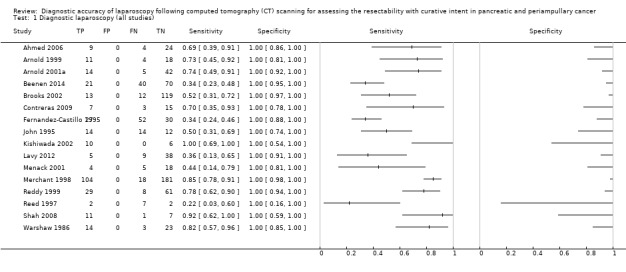

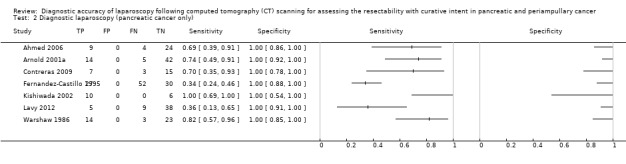

Findings

All of the included studies assessed pancreatic or periampullary cancer. The 16 included studies involved a total of 1146 participants (Data and analyses). The age of participants in the included studies ranged between 15 and 87 years. Studies that provided demographic details of participants reported roughly equal numbers of males and females. Seven studies included only people with pancreatic cancer (Ahmed 2006; Arnold 2001a; Contreras 2009; Fernandez‐Castillo 1995; Kishiwada 2002; Lavy 2012; Warshaw 1986), and two studies included only people with periampullary malignancies (Beenen 2014; Brooks 2002). The remaining studies did not provide information regarding the specific type of cancer they considered.

The details of the CT scan; other tests the participants underwent in addition to the CT scan; probability of CT resectable disease identified as unresectable by diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy (pre‐test probability); reasons for CT resectable disease identified as unresectable by diagnostic laparoscopy; probability of CT and diagnostic laparoscopy resectable disease identified as unresectable at laparotomy (post‐test probability); and the reasons for CT and diagnostic laparoscopy resectable disease identified as unresectable at laparotomy are all shown in Table 3.

2. Prior testing and unresectability.

| Study name | Type of CT scan | Prior testing in addition to CT scan |

Probability of CT resectable disease identified as unresectable by diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy (Pre‐test probability) |

Number of participants (N) and reasons for CT resectable disease identified as unresectable by diagnostic laparoscopy |

Probability of CT and diagnostic laparoscopy resectable disease identified as unresectable at laparotomy (Post‐test probability of negative diagnostic laparoscopy) |

Number of participants (N) and reasons for CT and diagnostic laparoscopy resectable disease identified as unresectable at laparotomy |

| Ahmed 2006 | Helical CT scan | None described | 35.1 | N = 9 Liver metastases = 6 Peritoneal metastases = 1 Peritoneal and liver metastases = 2 |

14.3 | N = 4 Metastatic disease = 2 Locally advanced disease (1 coeliac artery lymph node, 1 mesenteric vascular involvement) = 2 |

| Arnold 1999 | No further information on CT scan was available | All participants underwent endoscopy and ultrasound. Some participants underwent EUS, proportion unclear | 45.5 | N = 11 Liver metastases = 6 Peritoneal metastasis = 1 Peritoneal and liver metastases = 3 Peritoneal and omental metastases = 1 |

18.2 | N = 4 Liver metastases = 2 Peritoneal metastases = 1 Liver and peritoneal metastases = 1 |

| Arnold 2001 | No further information on CT scan was available | Endoscopy, ultrasound, and MRI. Proportion of participants who received each modality is unclear | 31.1 | N = 14 Liver metastases = 8 Peritoneal metastases = 2 Liver and peritoneal metastases = 4 |

10.6 | N = 5 Liver metastases = 3 Peritoneal metastases = 2 Metastases in the omentum and mesocolon = 2 Some had spread to more than 1 location |

| Beenen 2014 | No further information on CT scan was available | All participants underwent abdominal ultrasound and ERCP | 46.6 | N = 21 Reasons for unresectability not stated |

36.3 | N = 40 Reasons for unresectability not stated |

| Brooks 2002 | Contrast enhanced, thin slice | 85% of participants underwent ERCP | 17.4 | N = 13 Liver metastases = 6 Peritoneal metastases = 5 Other metastatic disease = 2 |

9.2 | N = 10 Liver metastases = 3 Vascular invasion = 3 Peritoneal metastases = 1 Local extension = 1 Benign disease = 2 |

| Contreras 2009 | Pancreas protocol CT scan | EUS used in some participants, proportion unclear | 40.0 | N = 7 Liver metastases = 4 Peritoneal metastases = 2 Gross regional lymphadenopathy = 1 |

16.7 | N = 3 Aortocaval node disease = 1 Liver metastases = 1 Coeliac node disease = 1 |

| Fernandez‐Castillo 1995 | Further details not known | None described | 72.4 | N = 27 Liver metastases = 11 Peritoneal metastases = 3 Omental metastases = 2 Metastases in more than 1 site = 11 |

63.4 | N = 87 Vascular invasion at subsequent angiography and did not undergo laparotomy = 42 Peritoneal disease at laparotomy = 2 Reasons for unresectability at laparotomy not stated = 43 |

| John 1995 | Contrast‐enhanced dynamic CT scan | Various scanning techniques used. Exact techniques and proportion who received them were unclear | 70.0 | N = 14 Liver metastases = 10 Peritoneal metastases = 8 Hilar lymph node involvement = 2 Some had spread to more than 1 location |

53.8 | N = 14 Metastatic disease = 2 Locally advanced and metastatic disease = 1 Locoregional spread = 11 |

| Kishiwada 2002 | Helical CT scan | All participants received ultrasound | 62.5 | Reasons for unresectability not stated | 0 | Reasons for unresectability at laparotomy not stated |

| Lavy 2012 | No further information on CT scan was available | All participants received EUS | 26.9 | Peritoneal metastases = 5 | 19.1 | N = 9 Metastatic disease = 2 Locally advanced cancer = 7 |

| Menack 2001 | Contrast‐enhanced CT scan with thin slices of pancreas | Transabdominal ultrasound, EUS, and ERCP performed in some participants, proportion unclear | 33.3 | Reasons for unresectability not stated | 21.7 | N = 5 Portal vein occlusion = 1 Metastatic disease in the lymph nodes or liver on laparoscopic ultrasound and biopsy = 2 Portal vein encasement = 1 Locally advanced disease at laparotomy = 1 |

| Merchant 1998 | Further details not known | Ultrasound, ERCP, and angiography performed on some participants, proportion unclear | 40.3 | N = 104 Liver metastases = 48 Extrapancreatic spread = 41 Nodal spread = 20 Vascular invasion = 37 Some had spread to more than 1 location |

9.0 | N = 18 Liver metastases = 6 Extrapancreatic disease = 3 Positive nodal disease = 3 Vascular invasion = 2 Benign disease = 4 |

| Reddy 1999 | Further details not known | None described | 37.8 | N = 29 Liver metastases = 23 Liver and peritoneal metastases = 3 Hepatic, peritoneal, and mesenteric metastases = 1 Mesenteric involvement = 2 |

11.6 | N = 6 Liver metastases = 4 Peripancreatic lymph node involvement = 2 |

| Reed 1997 | Further details not known | None described | 81.8 | Reasons for unresectability not stated | 77.8 | N = 7 Local tumour spread = 5 Omental spread = 1 Unclear = 1 |

| Shah 2008 | Multi‐detector row CT using pancreatic protocol | None described | 63.2 | N = 9 Metastases = 6 Locally advanced disease = 3 |

12.5 | Liver metastasis = 1 |

| Warshaw 1986 | Further details not known | All participants received chest roentgenography, transhepatic cholangiography, or ERCP and abdominal ultrasound. Some received coeliac and superior mesenteric angiography | 42.5 | N = 14 Liver metastases = 6 Parietal peritoneal metastases = 7 Omental metastatic disease = 1 |

11.5 | Liver metastases = 3 |

CT: computed tomography DL: diagnostic laparoscopy ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangio‐pancreatography EUS: endoscopic ultrasound MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

All probabilities in the table are reported as percentages.

The pre‐test probability of unresectability (due to distant metastases or local infiltration) after CT scanning ranged from 17.4% to 82% in the included studies. The median pre‐test probability was 41.4%, meaning that a person that was said to be resectable on CT scanning still had a 41.4% chance that their cancer would be unresectable. Visual inspection of the data in Table 3 did not suggest a relationship between the type of CT scan (such as helical CT or multi‐detector row CT, with or without a pancreatic protocol) or date of publication and the pre‐test probability of unresectable disease.

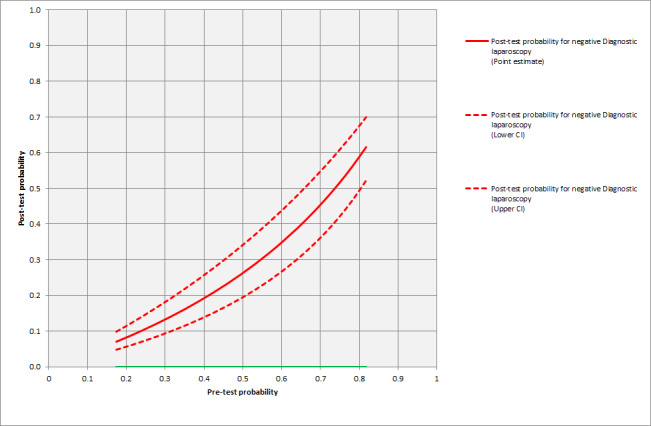

The summary estimate of sensitivity was 64.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 50.1 to 76.6), and the summary negative likelihood ratio was 0.36 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.52). Using the median pre‐test probability of unresectable disease of 0.414, the post‐test probability of unresectable disease for participants with a negative test result was 0.20 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.27). This means that if a person is said to have resectable disease after diagnostic laparoscopy (and a CT scan), there is a 20% chance that their cancer will be unresectable. The post‐test probability of unresectable disease is shown at different pre‐test probabilities of unresectable disease in Figure 6.

6.

Post‐test probability of unresectability for various pre‐test probabilities.

None of the studies reported any complications related to diagnostic laparoscopy. In some instances diagnostic laparoscopy provided an inconclusive result, that is it was unclear whether the participant had resectable or unresectable disease. Eight studies reported drop‐out rates of: 37.3% (Ahmed 2006), 29.8% (Arnold 1999), 36.1% (Beenen 2014), 67.5% (Contreras 2009), 4.4% (Fernandez‐Castillo 1995), 10.6% (Merchant 1998), 1.0% (Reddy 1999), and 61.2% (Shah 2008). In four of these studies the participants underwent laparotomy directly (Ahmed 2006; Beenen 2014; Contreras 2009; Shah 2008), and there was no indication of the selection criteria used for participants who had diagnostic laparoscopy. The other studies did not report drop‐out rates.

A subgroup analysis of studies that included only participants with pancreatic cancer gave a summary sensitivity of 67.9% (95% CI 41.1% to 86.5%). The summary negative likelihood ratio was 0.32 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.68). The median pre‐test probability of unresectability was 40.0% in this subgroup of studies. Using this pre‐test probability, the post‐test probability of unresectable disease after negative diagnostic laparoscopy was 0.18 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.92).

We also performed a post hoc meta‐regression of studies published before and after the year 2000, to test whether the sensitivity of diagnostic laparoscopy was different in the last decade, because major technological innovations in CT scans such as helical CT scans and multi‐slice CT scans became widely available in the last decade. The likelihood ratio test comparing the model with and without this covariate gave a P value of 1.0, indicating no evidence of a statistically significant difference in sensitivity between studies published before or after the year 2000.

We found an inconsistency in one study between the results reported in the main text of the study and a flow diagram which summarised the results (Kishiwada 2002). In our previous review we investigated the effect of this inconsistency by conducting a sensitivity analysis, which showed no change in the estimates of the summary sensitivity and the confidence intervals (Allen 2013). In another sensitivity analysis, we imputed missing data as false‐negative results (that is diagnostic laparoscopy incorrectly classified unresectable disease as resectable in all the missing participants) (Allen 2013). We have not presented the results of the first sensitivity analysis in this update since only participant was misclassified, and the impact on results was negligible. We did not perform the second sensitivity analysis since the reasons for not performing diagnostic laparoscopy were not reported, and it is unlikely that all the participants in diagnostic laparoscopy would have false‐negative results.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We have summarised the results in Table 1. The addition of diagnostic laparoscopy to CT scanning decreases the probability of unresectable disease from 41% to 20%. This means that for every 100 patients who receive a CT scan followed by diagnostic laparoscopy, 21 patients (41 minus 20) will avoid major laparotomy compared to with CT scanning alone. Although this review included studies which were more than 10 years old, with improvements in CT scanning possible over this period, the probability of unresectability was high (63.2%) even after multi‐detector row CT using a pancreatic protocol (Table 3). Diagnostic laparoscopy can either be performed as a separate procedure or immediately prior to major laparotomy as part of a larger procedure. These two different approaches have distinct advantages and disadvantages. The advantages of performing diagnostic laparoscopy as part of a larger procedure are that the patient needs only one hospital admission and one general anaesthetic. However, if the patient is diagnosed as having unresectable disease at laparoscopy and the subsequent laparotomy is then cancelled, it means that operation theatre time is wasted. It is also not possible to use paraffin section, the gold standard test, to confirm a histological diagnosis of cancer if diagnostic laparoscopy is undertaken as part of a larger procedure. If laparoscopy is performed as a separate diagnostic procedure, the patient must undergo the burden of two separate hospital admissions and anaesthetics, but no operation theatre time will be wasted if they are found to have unresectable disease. The time delay between the two separate procedures also allows the use of paraffin sections.

We found no complications related to diagnostic laparoscopy in this systematic review, however the literature reports an injury rate of 0.23% involving major blood vessels or the bowel (Azevedo 2009). This indicates that diagnostic laparoscopy should only be performed by appropriately trained healthcare professionals with expertise in the conduct of diagnostic laparoscopy and biopsy during diagnostic laparoscopy.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

A strength of this review is that we placed no restrictions on the language of publication and conducted a comprehensive search. We avoided the use of search filters and undertook additional searches to find related articles. We also performed a citation search. We therefore minimised the risk of missing relevant studies. Little is known about the mechanisms of publication bias for diagnostic accuracy studies, and so it is not possible to estimate the impact of unpublished studies on our findings. Nevertheless, the studies included in this systematic review are likely to be the majority of studies that provide evidence on this topic. Another strength of this review is that we used a recommended approach for meta‐analysis.

Our review has some weaknesses. Firstly, our findings are based on studies with low methodological quality, and there was considerable between‐study heterogeneity. There were between‐study differences in the conduct and interpretation of diagnostic laparoscopy (in terms of what constitutes a suspicious lesion) and differences in the assessment of resectability on laparotomy. Despite the observed differences in the conduct and interpretation of diagnostic laparoscopy, the procedure appeared to decrease the number of unnecessary laparotomies in 15 of the 16 included studies. With regards to methodological quality, the presence of selection bias may raise doubts about the applicability of our findings in clinical practice. Secondly, determination of unresectability on laparotomy relies on the judgement of individual surgeons, which may not have been appropriate in some of the studies. This could have caused an error in the estimation of diagnostic accuracy. Thirdly, an inappropriate delay between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy can result in patients who had previously resectable cancer developing unresectable cancer because of local or distant spread. This will underestimate the accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy. Fourthly, inappropriate exclusion of patients is likely to result in an error in the estimation of diagnostic accuracy if the excluded patients had low likelihood of unresectability or high likelihood of unresectability. We performed a sensitivity analysis imputing the results according to the worst‐case scenario, that is as false negatives. As mentioned earlier, indeterminate results at diagnostic laparoscopy will result in the patients undergoing laparotomy.

We were able to identify one previous systematic review on this topic (Chang 2009). Despite the inclusion of studies in which histopathological confirmation of suspicious lesions was not obtained, and the lack of meta‐analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy, the authors of the review suggested that diagnostic laparoscopy decreases unnecessary laparotomy by 4% to 36% and that diagnostic laparoscopy has a role in staging pancreatic cancer (Chang 2009). We agree broadly with the conclusions of the authors of the identified systematic review (Chang 2009).

Applicability of findings to the review question

This review is only applicable to people with pancreatic and periampullary cancer who have had a CT scan which demonstrated resectable disease prior to diagnostic laparoscopy. This review is also applicable only when the interval between diagnostic laparoscopy and laparotomy is sufficient to obtain histopathology results but not too long for the cancer to spread. Diagnostic laparoscopy appears to be beneficial in avoiding unnecessary laparotomies, and the morbidity associated with diagnostic laparoscopy is low. Cost‐effectiveness needs to be formally assessed to inform clinical and policy decision making in state‐funded health care.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although the methodological quality of the evidence was limited, diagnostic laparoscopy appears to be useful in decreasing the proportion of people with pancreatic and periampullary cancer that were found to have resectable disease on CT scanning who will undergo unnecessary laparotomy.

Implications for research.

Well‐designed diagnostic test accuracy studies are needed to reliably estimate the accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy. Comparison with positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and laparoscopic ultrasound may further demonstrate the value of diagnostic laparoscopy in staging pancreatic and periampullary cancers.

The conclusion of this study needs regular review as the quality of CT scanning improves, and diagnostic laparoscopy should be compared with other tests for staging pancreatic and periampullary cancers.

Cost‐effectiveness studies should be undertaken to determine whether diagnostic laparoscopy should be routinely performed in state‐funded clinical practice.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 June 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated. One new study was added and the data re‐analysed. |

| 2 June 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The conclusions remain unchanged. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 10, 2011 Review first published: Issue 11, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 August 2014 | Amended | Review republished solely to include the plain language summary. |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group, the UK Support Unit for Diagnostic Test Accuracy (DTA) Reviews, and the DTA editorial team for their advice in the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary of terms

Index test: The diagnostic test being evaluated. In this review the index test is diagnostic laparoscopy after CT scanning

QUADAS: A tool for assessing the methodological quality of diagnostic accuracy studies in terms of risk of bias and applicability to the review question. The assessment parameters are described in more detail in the main text of the review

Reference standard: The test that is accepted as the best available to classify the target condition correctly in a particular setting. In this review the reference standard is biopsy with histopathological confirmation after diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy, or the surgeon's judgement of unresectability at laparotomy when biopsy confirmation was not possible

Sensitivity: Proportion of diseased individuals correctly identified as having the disease by the index test i.e. True positives/(True positives + False negatives)

Specificity: Proportion of disease‐free individuals correctly identified as being disease‐free by the index test i.e. True negatives/(False positives + True negatives)

Target condition: The disease or condition to be diagnosed. In this review the target condition is unresectable pancreatic and periampullary cancer

Appendix 2. Cochrane Register of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies and CENTRAL search strategy

#1 ((ampulla near/2 vater*) or ampullovateric or (papilla near/2 vater*) or periampulla* OR peri‐ampulla* OR choledoch* or alcholedoch* or bile duct* or biliary or cholangio* or gall duct or duoden* or small bowel or small intestin* or enter* or pancrea*) #2 (carcin* or cancer* or neoplas* or tumour* or tumor* or cyst* or growth* or adenocarcin* or malign*) #3 (#1 AND #2) #4 (pancreatect* OR pancreaticojejunost* OR pancreaticogastros* OR pancreaticoduodenect* OR duodenopancreatectom*) #5 (#3 OR #4) #6 (laparoscop* or peritoneoscop* or celioscop* or coelioscop*) #7 (#5 AND #6)

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

(((((ampulla vateri[tiab] OR "Ampulla of Vater" [Mesh] OR ampullovateric[tiab] OR papilla vateri[tiab] OR vater papilla[tiab] OR vater ampulla[tiab] OR peri‐ampull*[tiab] OR periampull*[tiab] OR choledoch*[tiab] OR alcholedoch*[tiab] OR bile duct*[tiab] OR biliary[tiab] OR cholangio*[tiab] OR gall duct[tiab] OR duodenum[tiab] OR duodenal[tiab] OR duoden*[tiab] OR small bowel[tiab] OR small instestin*[tiab] OR enteral[tiab] OR enteric[tiab] OR enter*[tiab] OR pancreatic[tiab] OR pancreato*[tiab] OR pancreas*[tiab]) AND (carcinoma[tiab] OR carcinomas[tiab] OR carcin*[tiab] OR cancer*[tiab] OR neoplas*[tiab] OR tumor[tiab] OR tumors[tiab] OR tumorous[tiab] OR tumour*[tiab] OR tumor*[tiab] OR cyst[tiab] OR cysts[tiab] OR cystic[tiab] OR cyst*[tiab] OR growth*[tiab] OR adenocarcin*[tiab] OR malignant[tiab] OR malignancy[tiab])) OR "Duodenal Neoplasms"[Mesh] OR "Pancreatic Neoplasms"[Mesh] OR "Common Bile Duct Neoplasms"[Mesh]) AND (surger*[tiab] OR operat*[tiab] OR resection*[tiab] OR surgical*[tiab] OR Surgical Procedures, Operative[MeSH] OR General Surgery[MeSH])) OR (pancreatect*[tiab] OR pancreaticojejunost*[tiab] OR pancreaticogastros*[tiab] OR pancreaticoduodenect*[tiab] OR duodenopancreatectom*[tiab] OR Pancreatectomy[MeSH] OR Pancreaticojejunostomy[MeSH] OR Pancreaticoduodenectomy[MeSH])) AND (laparoscop*[tiab] OR peritoneoscop*[tiab] OR celioscop*[tiab] OR coelioscop*[tiab] OR "Laparoscopy"[Mesh])

Appendix 4. EMBASE search strategy

1 ((ampulla vateri or ampullovateric or papilla vateri or vater papilla or vater ampulla or periampull* or peri‐ampull* or choledoch* or alcholedoch* or bile duct* or biliary or cholangio* or gall duct or duoden* or small bowel or small intestin* or enter* or pancrea*) and (carcin* or cancer* or neoplas* or tumour* or tumor* or cyst* or growth* or adenocarcin* or malign*)).ti,ab. 2 exp duodenum cancer/ or Vater papilla tumor/ or exp pancreas cancer/ or exp bile duct tumor/ 3 1 or 2 4 (surger* or surgical* or operat* or resection*). ti,ab. 5 exp Surgery/ 6 4 or 5 7 3 and 6 8 (pancreatect* OR pancreaticojejunost* OR pancreaticogastros* OR pancreaticoduodenect* OR duodenopancreatectom*). ti,ab. 9 exp pancreas surgery/ 10 7 or 8 or 9 11 (laparoscop* or peritoneoscop* or celioscop* or coelioscop*). ti,ab. 12 laparoscopy/ or laparoscopic surgery/ 13 11 or 12 14 10 and 13

Appendix 5. Science Citation Index search strategy

#1 TS=(((ampulla vateri or ampullovateric or papilla vateri or vater papilla or vater ampulla or periampull* or peri‐ampull* or choledoch* or alcholedoch* or bile duct* or biliary or cholangio* or gall duct or duoden* or small bowel or small intestin* or enter* or pancrea*) and (carcin* or cancer* or neoplas* or tumour* or tumor* or cyst* or growth* or adenocarcin* or malign*))) #2 TS=(operat* OR surger* OR surgical* OR resection*) #3 #1 AND #2 #4 TS=(pancreatect* OR pancreaticojejunost* OR pancreaticogastros* OR pancreaticoduodenect* OR duodenopancreatectom*) #5 #3 OR #4 #6 TS=(laparoscop* or peritoneoscop* or celioscop* or coelioscop*) #7 #5 AND #6

Appendix 6. SAS code for analysis

data DiagnosticTestMetaAnalysis; input Study_id TP FP FN TN; datalines;

1 9 0 4 24

2 11 0 4 18

3 14 0 5 42

4 21 0 40 70

5 13 0 12 119

6 7 0 3 15

7 27 0 52 30

8 14 0 14 12

9 10 0 0 6

10 5 0 9 38

11 4 0 5 18

12 104 0 18 181

13 29 0 8 61

14 2 0 7 2

15 11 0 1 7

16 14 0 3 23 run;

/* Modify the dataset for the analysis */ data dt; set DiagnosticTestMetaAnalysis; sens=1; spec=0; true=tp; n=tp+fn; output; sens=0; spec=1; true=tn; n=tn+fp; output; run;

/* Ensure that both records for a study are clustered together */ proc sort data=dt; by study_id ; run;

ods output ParameterEstimates=pet4 FitStatistics=fitt4 additionalestimates=addest4; /* Run random effects logistic regression model for sensitivity only*/ proc nlmixed data=dt tech=quanew lis=5 qpoints=10; parms msens=2 s2usens=0 ; logitp=(msens+usens)*sens; p = exp(logitp)/(1+exp(logitp)); model true ˜ binomial(n,p); random usens ˜ normal([0],[s2usens]) subject=study_id out=randeffs; /* logLR based on spec=1 */ estimate 'logLR‐' log((1‐(exp(msens)/(1+exp(msens))))) ; run;

/* Obtain summary sens and spec from the model 4 */ data summary4; set pet4; if parameter = 'msens' then name = 'Sensitivity'; if parameter = 'msens' then summary=100 * exp(estimate)/(1 + exp(estimate)); if parameter = 'msens' then summlower=100 * exp(lower)/(1 + exp(lower)); if parameter = 'msens' then summupper=100 *exp(upper)/(1 + exp(upper)); output; run; /* Obtain summary LR‐ */ data summaryLR; set addest4; summary=exp(estimate); summlower=exp(lower); summupper=exp(upper); output; run;

Appendix 7. Calculation of post‐test probability of unresectable disease for patients with a negative test result

The post‐test probability of unresectable disease for patients with a negative test result can be calculated from the pre‐test probability of unresectable disease and the negative likelihood ratio. The calculation using the median pre‐test probability from the included studies, as an example, is shown below.

Pre‐test probability = 0.414 Pre‐test odds = Pre‐test probability/(1 ‐ Pre‐test probability) = 0.414/0.586 = 0.706 Post‐test odds of negative test = Post‐test odds * negative likelihood ratio = 0.706 * negative likelihood ratio Post‐test probability of unresectable disease for patients with a negative test result = Post‐test odds/(1 + Post‐test odds)

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Diagnostic laparoscopy (all studies) | 16 | 1146 |

| 2 Diagnostic laparoscopy (pancreatic cancer only) | 7 | 340 |

1. Test.

Diagnostic laparoscopy (all studies).

2. Test.

Diagnostic laparoscopy (pancreatic cancer only).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahmed 2006.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 37 Females: Not stated Age: Not stated |

||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients with potentially resectable, histologically confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma (after CT scan) Setting: Surgical centre in the USA |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Tumours were considered locally advanced and unresectable if laparoscopic examination revealed peritoneal or liver metastasis, coeliac artery or para‐aortic lymph node involvement, or tumour invasion or encasement of the coeliac axis or hepatic artery |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: Unresectability Reference standard: Laparotomy for patients with no evidence of metastases on laparoscopy; biopsy with histolopathological confirmation of spread for patients with suspected metastases Criteria for positive diagnosis: Tumours were considered locally advanced and unresectable if laparoscopic examination revealed peritoneal or liver metastasis, coeliac artery or para‐aortic lymph node involvement, or tumour invasion or encasement of the coeliac axis or hepatic artery |

||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard were available: Not stated Number of patients who were excluded from the analysis: 22 (37.3%) |

||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| High | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Unclear | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| High | |||

Arnold 1999.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 33 Females: Not stated Age: Not stated |

||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients with potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (after CT scan) Setting: Germany (setting not clear) |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Biopsies of lesions suspicious of metastases |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: Unresectability Reference standard: Laparotomy for patients with no evidence of metastases on laparoscopy; biopsy with histolopathological confirmation of spread for patients with suspected metastases Criteria for positive diagnosis: Not stated |

||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard were available: Not stated Number of patients who were excluded from the analysis: 14 (29.8%) |

||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| High | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Unclear | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| High | |||

Arnold 2001a.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 61 Females: Not stated Age: Not stated |

||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients with potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (after CT scan) Setting: Germany (setting not clear) |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Biopsies of lesions suspicious of metastases |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: Unresectability Reference standard: Laparotomy for patients with no evidence of metastases on laparoscopy; biopsy with histolopathological confirmation of spread for patients with suspected metastases Criteria for positive diagnosis: Not stated |

||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard were available: Not stated Number of patients who were excluded from the analysis: Not stated |

||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Unclear | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Unclear | ||

| Unclear | |||

Beenen 2014.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 131 Females: Not stated Age: Not stated |

||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients with CT and ultrasound resectable periampullary cancer Setting: Secondary/tertiary care, the Netherlands |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Biopsy confirmation of suspicious lesions |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: Unresectability Reference standard: Laparotomy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Locally advanced pancreatic cancer or metastatic pancreatic cancer |

||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard were available: 0 Number of patients who were excluded from the analysis: 74 (36.1%) |

||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | No | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| High | High | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | No | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Unclear | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| High | |||

Brooks 2002.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 144 Females: Not stated Age: Not stated |

||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients with potentially resectable periampullary carcinoma other than pancreatic cancer Setting: Surgical centre in the USA |

||

| Index tests | Diagnostic laparoscopy Criteria for positive diagnosis: Patients were deemed unresectable at diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy if they were found to have histologically proved peritoneal or hepatic metastases, distant nodal involvement, arterial involvement, or local extension outside the resection field |

||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: Unresectability Reference standard: Laparotomy for patients with no evidence of metastases on laparoscopy; biopsy with histolopathological confirmation of spread for patients with suspected metastases Criteria for positive diagnosis: Patients were deemed unresectable at diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy if they were found to have histologically proven peritoneal or hepatic metastases, distant nodal involvement, arterial involvement, or local extension outside the resection field |

||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard were available: 10 (6.9%) Number of patients who were excluded from the analysis: Not stated |

||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Unclear | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Unclear | ||

| Unclear | |||

Contreras 2009.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Sample size: 25 Females: 12 (32.5%) Age: 68 years |

||