Abstract

Background

End‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a chronic, debilitative and progressive illness that may need interventions such as dialysis, transplantation, dietary and fluid restrictions. Most patients with ESKD will require renal replacement therapy, such as kidney transplantation or maintenance dialysis. Advance care planning traditionally encompass instructions via living wills, and concern patient preferences about interventions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and feeding tubes, or circumstances around assigning surrogate decision makers. Most people undergoing haemodialysis are not aware of advance care planning and few patients formalise their wishes as advance directives and of those who do, many do not discuss their decisions with a physician. Advance care planning involves planning for future healthcare decisions and preferences of the patient in advance while comprehension is intact. It is an essential part of good palliative care that likely improves the lives and deaths of haemodialysis patients.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine whether advance care planning in haemodialysis patients, compared with no or less structured forms of advance care planning, can result in fewer hospital admissions or less use of treatments with life‐prolonging or curative intent, and if patient's wishes were followed at end‐of‐life.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 27 June 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. We also searched the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Social Work Abstracts (OvidSP).

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at advance care planning versus no form of advance care planning in haemodialysis patients was considered for inclusion without language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study exists, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes are only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted. Non‐randomised controlled studies were excluded.

Main results

We included two studies (three reports) that involved 337 participants which investigated advance care planning for people with ESKD. Neither of the included studies reported outcomes relevant to this review. Study quality was assessed as suboptimal.

Authors' conclusions

We found sparse data that were assessed at suboptimal quality and therefore we were unable to formulate conclusions about whether advance care planning can influence numbers of hospital admissions and treatment required by people with ESKD, or if patients' advance care directives were followed at end‐of‐life. Further well designed and adequately powered RCTs are needed to better inform patient and clinical decision‐making about advance care planning and advance directives among people with ESKD who are undergoing dialysis.

Keywords: Humans; Advance Care Planning; Renal Dialysis; Hospitalization; Hospitalization/statistics & numerical data; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Kidney Failure, Chronic/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Third‐Party Consent; Third‐Party Consent/statistics & numerical data

Plain language summary

Advance care planning for haemodialysis patients

Background

People with chronic kidney disease and end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) have irreversible kidney damage and require renal replacement therapy. In developed countries, haemodialysis has become the most common treatment for people with ESKD. Despite its life‐saving potential, haemodialysis can be a significant physical and psychological burden to patients. Advance care planning is the process of planning for a person’s future health and personal care decisions in terms of level of healthcare and quality of life the person would want, should for any reason, the person becomes unable to participate in decision‐making. Advance care goals can change over time and advance care planning assists in addressing these changes and readdress care goals over time. This helps to ensure that individual choices are respected in future medical treatment in an event where the person cannot communicate or make decisions.

We wanted to find out if advance care planning can improve health outcomes among people with ESKD in terms of use of resuscitation measures such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and withdrawal from dialysis. Additionally, we wanted to find out whether patient wishes were followed in the end of life period.

Study characteristics

We searched the literature up to June 2016 and found two studies (three reports) that involved 337 patients which investigated use of patient‐centred advanced care planning (PC‐ACP) and peer mentoring interventions.

Key results

Neither study addressed our questions concerning use of life‐prolonging treatments such as resuscitation, death in hospital or withdrawal from dialysis. It remains uncertain if advance care planning can improve health outcomes among ESKD patients. More research is required to better inform use of PC‐ACP for people receiving haemodialysis treatment.

Background

Many people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) have irreversible kidney damage and require renal replacement therapy. For people with ESKD, kidney transplant is the treatment of choice because compared with haemodialysis, transplant reduces mortality risk and improves quality of life. Haemodialysis has become the default treatment for people with ESKD in developed countries, and although it sustains life, for many people it is a supportive or palliative therapy (Davison 2007). Age and co‐morbidities of people receiving haemodialysis have increased. In low‐risk patients, mortality is much higher compared with age‐matched controls who do not have kidney failure; and for high‐risk patients, haemodialysis may simply prolong the process of dying (Vilar 2011).

Advance care planning traditionally encompasses instructions via living wills concerning patient preferences about interventions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and feeding tubes, or circumstances around assigning surrogate decision makers. However, few patients formalise their wishes as advance care planning directives, and of those who do, many do not discuss their decisions with a physician (Weisbord 2003). In many instances, patients do not address withdrawal from dialysis because they are unaware that this option is available, or believe that their physician would not support this decision (Davison 2007). Davison 2010 study of 584 patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD reported that only 38.2% had completed a personal directive.

McAdoo 2012 surveyed 138 kidney patients at 10 London hospitals and found that 28% (n = 26) of those who died in hospital had discussed end‐of‐life care with medical or nursing staff in the year before death, and 52% (n = 49) had good symptom control at the time of death. The absence of end of life discussion does not accord with findings that people with CKD most valued being informed about prognosis and in being able to prepare for death (Davison 2010). Poorly documented advance care planning processes resulted in the survey by McAdoo 2012 eliciting that although few patients discussed end‐of‐life care with medical teams, 43% (n = 40) discontinued dialysis, and 45% (n = 42) were referred for palliative care, highlighting the need for clear and well‐constructed advance care planning processes and documentation.

Advance care planning involves planning for future healthcare decisions and preferences of the patient in advance while comprehension is intact. It is an essential part of good palliative care that likely improves the lives and deaths of haemodialysis patients (Davison 2006).

Description of the condition

CKD is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function (e.g. albuminuria or GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2), present for greater than three months, with implications for health (KDIGO 2013). The incidence and prevalence of CKD varies across regions with incidence as high as 200 cases per million per year in some countries (Levey 2012). Advanced (Stage 5) CKD (GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) is known as ESKD, and is associated with metabolic complications such as uraemia, electrolyte disorders, and hypertension, which contribute to significant morbidity and mortality.

The aim of haemodialysis is to correct metabolic and electrolyte disturbances seen in ESKD patients. Haemodialysis uses a dialyser consisting of parallel membrane plates or hollow fibres suspended in dialysis fluid (dialysate), which act as a semipermeable membrane, across which blood and dialysate can flow. The dialysate fluid has an electrolyte composition similar to that of extracellular fluid and flows in an opposite direction to the blood. Solute and water can move across the semipermeable membrane, allowing metabolic wastes and excess body water from blood to be removed and replenishes body buffers before the blood is returned to the patient (Mallick 1999). Haemodialysis carries risks such as vascular access failure, venous occlusion, and line infections (Brown 2007).

Recent reports indicate a gradual plateau of incident ESKD over time (ANZDATA 2012). There has been an increase in dialysis patients dying after withdrawal of dialysis (10% to 15% in 1990, 20% in 2004) making it the second leading cause of death following cardiovascular disease (KDIGO 2013).

Description of the intervention

Although advance care planning for each patient is individualised, the underlying principles of the advance care planning process are similar: the responsible physician determines the patient's priorities, establishes agreed levels of care, manages appropriate transition from active to palliative care, achieves symptom control at end‐of‐life, and acts as a spokesperson for the patient if needed (Arulkumaran 2012). Advance care plans are reviewed constantly as part of an overall dynamic program of care (Holley 2003).

The process is changing from a document‐driven, decision‐focused event to an approach that encompasses understanding, reflection, communication, and discussion involving patients, family or caregivers, and healthcare staff to clarify end‐of‐life care preferences (Davison 2006). Advance care planning is traditionally used in the event of incapacity to make informed decisions (Simon 2008); however change in health status over time may prompt change about intervention preferences during the course of care. Discussions therefore occur early in the disease process (Davison 2007), and patients are encouraged to appoint a spokesperson if needed. The goal is that preferences are communicated to all stakeholders and documented appropriately (Russon 2010).

How the intervention might work

Aiding patients to establish options and priorities for end‐of‐life care enables preferences to be maintained according to individual wishes (Russon 2010). Advance care plans are often not followed by healthcare providers, and it may not be possible to anticipate all clinical contingencies for individual patients. The most significant barrier may be lack of physician intervention to initiate and guide advance care planning discussions (Davison 2010).

In some instances, continuation of treatment and admission to intensive care settings may prolong death rather than sustain life. A well‐constructed and communicated advance care plan is likely to improve satisfaction and end‐of‐life care for patients and reduce psychological stress for surviving relatives (Arulkumaran 2012).

The focus of advance care planning is about living well and ensuring optimal care for patients near the end‐of‐life, and not just on death and the decision to refuse treatment. Advance care planning enables patients to prepare for death, strengthen relationships with loved ones, achieve control over their lives, and relieve burden on others (Singer 1995).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite its life‐saving potential, haemodialysis can impose significant risks of morbidity and mortality, as well as a range of physical and psychological symptoms and complications (Weisbord 2003). Advance care planning may be beneficial in providing better quality of care at end‐of‐life and offer more autonomy in health care decision‐making for people with ESKD receiving dialysis treatment.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine whether advance care planning in haemodialysis patients, compared with no or less structured forms of advance care planning, can result in fewer hospital admissions or less use of treatments with life‐prolonging or curative intent, and if patient's wishes were followed at end‐of‐life.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at advance care planning versus no form of advance care planning for haemodialysis patients were included.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion involved people with ESKD undergoing haemodialysis.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that involved people with clinically‐diagnosed mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia, dementia), and people with ESKD not on haemodialysis.

Types of interventions

We included studies that investigated the use of advance care planning.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Use of treatments with primary life‐prolonging or curative intent order in place, such as resuscitation (yes/no)

Hospital death (yes/no)

Dialysis discontinued before death (yes/no).

Secondary outcomes

Good symptom control achieved (yes/no)

Use of end‐of‐life care pathway (yes/no)

Patient's satisfaction with end‐of‐life care (yes/no)

Caregiver's satisfaction with end‐of‐life care (yes/no)

Treatment goal nearing the end‐of‐life (life prolonging/palliation)

Inpatient hospital admission near end‐of‐life (yes/no)

Length of stay in hospital (continuous)

Awareness among healthcare providers of patients' stated preferences during end‐of‐life care and advance decisions (yes/no).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register to 27 June 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

We also searched the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Social Work Abstracts (OvidSP) to December 2014.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of clinical practice guidelines, review articles and relevant studies

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors then independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and if necessary the full text of the studies, and determined which satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study exists, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes are only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted. Non‐randomised controlled studies were excluded.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes (e.g. use of treatments with primary life‐prolonging or curative intent, hospital death, hospital admission, dialysis discontinuation prior to death, good symptom control achieved, satisfaction with end‐of‐life care, treatment goal nearing end‐of‐life (life‐prolonging or palliation), and healthcare providers' awareness of patients' stated preferences) was planned to be expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. knowledge of advance care planning, length of hospital stay prior to death) the mean difference (MD) was planned to be used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales was used.

Unit of analysis issues

We had planned to include effect estimates from cluster‐RCTs and cross‐over RCTs together with estimates from parallel RCTs where designs were properly accounted for and reported. If effect estimates for cluster‐RCTs and cross‐over RCTs were not corrected appropriately for possible unit of analysis errors, we had planned to adjust the CIs of those estimates by reducing the size of each study to its effect sample size.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required was sought from the original author by written correspondence (e.g. emailing or writing to corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was planned to be performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were planned to be investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last‐observation‐carried‐forward) was critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where required, heterogeneity was planned to be analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 test (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where required and possible, funnel plots were to be used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to pool data using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also to be used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was planned to be performed to investigate if effects varied due to advance care planning process type, differences in populations and settings, and study design (cluster‐RCTs versus parallel RCTs). Other potential sources of heterogeneity, such as participants' age and gender was also planned to be analysed. Adverse effects was planned to be tabulated and assessed using descriptive techniques. If possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was planned to be calculated for each adverse effect, either compared with no treatment (i.e. advance care planning) or another intervention.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

Results

Description of studies

For detailed descriptions, please see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

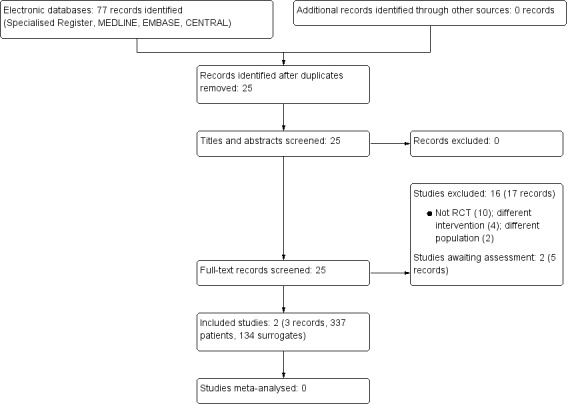

Our search identified 77 potentially relevant records; of these, 52 were duplicates. We assessed 25 full text papers, and excluded 17 (See Figure 1). Two studies (three reports) met our inclusion criteria (Kirchhoff 2010; Perry 2005) Two studies reported both peritoneal and haemodialysis patients, and data could not be split from the reports (Song 2010; SPIRIT Study 2013). Our attempts to contact the authors were unsuccessful; both studies have been added to Studies awaiting classification.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included two studies (three reports) that involved a total of 337 patients and 134 surrogates (see Characteristics of included studies).

Kirchhoff 2010 conducted a parallel RCT involving 313 patients and their surrogate pairs from 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2007. Of the 313 patients, 134 had diagnoses of ESKD and 179 were diagnosed with end‐stage coronary heart failure (CHF). Only those with ESKD were included in our analysis. Of the ESKD patients 70 were randomised to the intervention group to receive patient centred‐advanced care planning (PC‐ACP) and 64 received usual care in the control group. The study was conducted at two centres (six outpatient clinics of large community or university health systems) in Wisconsin, USA. Participants were recruited from nephrology units, dialysis clinics and dialysis units affiliated with the two study centres.

Intervention group participants completed 60 to 90 minute interviews with a trained facilitator. PC‐ACP assessed patient and surrogate understanding and experiences with illness; provided information about disease‐specific treatment options and their benefits and burdens; assisted in documenting patient preferences for treatment; and assisted surrogate partners to make decisions in line with patients' preferences. Control group participants received usual care consisting of advance care planning facilitation; standard advance directive counselling; assessment of advance directive on admission; and if patients needed more information. Post‐death data were reviewed to measure concordance between patients' preferences and care at end of life.

Study outcomes included knowledge about advance care planning; statement of treatment preferences; quality of patient‐clinician communication about end‐of‐life care; and concordance of patient preferences and care at end of life.

This study was published in two separate reports.

Perry 2005 conducted a three‐arm parallel RCT that involved 203 participants, of whom 63 were assigned peer‐mentoring intervention group, 59 to printed material intervention group, and 81 to the control group to receive routine care. The study was conducted at 21 dialysis units in Michigan, USA.

Study duration was two to four months for each participant. Participants randomised to the peer mentoring intervention group were contacted by peers eight times (five telephone calls and three face‐to‐face meetings) to discuss the value of completing advance directives. Peers had attended regional advanced directive workshops where advance directives issues were discussed. Peer mentors and patients discussed the program; gave their own experience with chronic illness; goals outside ESKD; spiritual orientation and fears; end‐of‐life considerations and barriers to completing advance directives; contribution to others and patient's strength. Participants in the printed material received literature developed by the (US) National Kidney Foundation. Control group participants received routine care provided by the dialysis unit (not described).

Study outcomes included completion of advanced directive during the study; whether or not patients wished to complete an advanced directive if they had not done so during the study period; and how comfortable the patient appeared to be in discussion about advance directives.

Excluded studies

Ten studies that were not RCTs (Badzek 2000; Choudry 1995; Fassett 2011; Friedman 2010; Hodge 2010; Katsube 2011; Lindblad 2010; Manda 2013; Parker 2009; Tangri 2011)

Four studies that compared interventions not relevant to this review (den Hoedt 2013; Singer 1995; SPIRIT Pilot Study 2009; Wright 2009)

Two studies enrolled participants who were not relevant to this review (Briggs 2004; Dallas 2012).

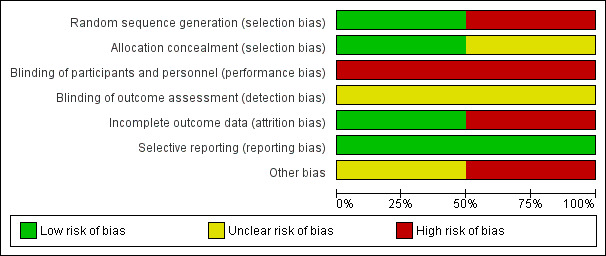

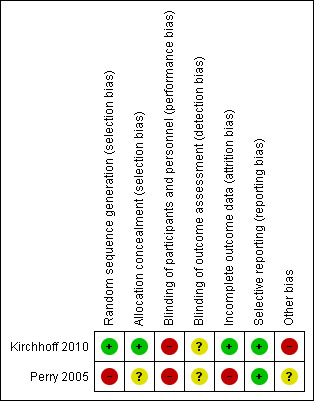

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias for both included studies. Overall, risk of bias was assessed as unclear. (See Figure 2; Figure 3)

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Kirchhoff 2010 reported that pairs of eligible patients and their surrogates were randomised using the sealed‐envelope method and was assessed at low risk of bias. Perry 2005 did not report randomisation or allocation concealment methods. Participants were moved between groups after allocation and these domains were judged to be at high risk of bias.

Blinding

Participants were not blinded in either study and were judged at high risk of performance bias. Neither Kirchhoff 2010 nor Perry 2005 report if outcome assessors were blinded and were assessed at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Both studies reported reasons and numbers of dropouts. Kirchhoff 2010 conducted intention‐to‐treat analysis which was assessed at low risk of bias. Perry 2005 excluded participants without follow‐up data from analysis and was assessed at high risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

No reporting bias was noted for either of the included studies and all specified outcomes were reported. Protocols were unavailable. Reporting bias was assessed as low risk.

Other potential sources of bias

Kirchhoff 2010 reported four instances where neither surrogate nor medical record information was available for both ESKA and CHF participants. Kirchhoff 2010 did not reach calculated power levels due to resource limitations and the study was stopped early. Kirchhoff 2010 was supported by grants from the Agency of Health Care Research and Quality and National Institutes of Health. Two authors of Kirchhoff 2010 were employed by the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation which owns rights to the intervention used in the study. We assessed Kirchhoff 2010 at high risk of other bias.

Perry 2005 was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; National Kidney Foundation of Michigan; and National Institute of Mental Health Career grant. Specific support relationships were unclear. We assessed this study at unclear risk of other bias.

Effects of interventions

Neither of the included studies reported on any of our specified primary or secondary outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included two studies (three reports) that involved a total of 337 patients and 134 surrogates that investigated PC‐ACP and peer support interventions. Neither study reported any of our primary or secondary outcomes.

Kirchhoff 2010 investigated PC‐ACP and reported that there was improved understanding of patient goals and preferences for future medical decisions among surrogates who received PC‐ACP compared with those in the control group. There was a higher percentage of surrogates in the intervention group who knew the degree of latitude (decision making authority a patient wished to grant the chosen surrogate) the patient chose compared with control group participants. Communication quality was rated as highly satisfactory among those in the intervention group, and it was suggested that PC‐ACP did not create anxiety or other adverse effects. Kirchhoff 2010 also found higher rates of concordance between patients' preferences and end‐of‐life care among intervention group participants compared with the control group, including cardiopulmonary arrest.

Perry 2005 reported that peer support intervention resulted in a higher proportion of participants completing an advance directive or expressing a desire to complete, compared with printed material and routine care. The study also reported that peer support intervention group participants had significantly greater levels of comfort about discussion of advance directives than printed material and routine care group participants.

PC‐ACP and peer support may be useful interventions in advance care planning for haemodialysis patients. Both studies suggest that in‐depth discussion about advance directives and end‐of‐life care did not cause unnecessary discomfort or anxiety. It should also be noted that patients in Perry 2005 were younger than those in Kirchhoff 2010. However, the small number of included studies and participants means that further research is needed before conclusive evaluation can be made about advance care planning for haemodialysis patients.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Findings reported by Kirchhoff 2010 and Perry 2005 were confined to specific geographical and ethnic populations. Participants were generally older people, and findings may therefore not be generalisable to diverse populations and settings where advance care planning methods, healthcare systems and adherence rates vary or do not exist. The small number of included studies meant that we were unable to analyse data related to our specified primary and secondary outcomes. We were unable to perform subgroup analysis or meta‐analysis due to insufficient data.

Quality of the evidence

Risk of bias was assessed as unclear or high in over half of the domains assessed, limiting our confidence in the quality of evidence. Due to the nature of participants and interventions, blinding of participants and interventionists was not possible and blinding of outcome assessment was not reported in either study. Patients with missing follow‐up data were excluded from the analysis by Perry 2005.

Due to insufficient resources, Kirchhoff 2010 was unable to recruit sufficient numbers of participants to attain optimal power during the study period. Calculated power analysis required 560 patient‐surrogate pairs for optimal analysis; however, recruitment was stopped at 313 pairs. The 179 participants with CHF were omitted from assessment for this review.

Overall, quality of evidence was assessed as suboptimal.

Potential biases in the review process

Potential sources of biases in the review process include that only a small number of studies were eligible for our review. Although literature searches included all major databases and handsearching of kidney conference proceedings, it is possible that relevant unpublished data were not identified.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings are consistent with an earlier audit of dialysis patients by McAdoo 2012 where most deaths occurred in hospital settings and dialysis was withdrawn before death among fewer than half of the participants.

The results of this review suggested that patients were highly satisfied with the quality of communication and greater levels of comfort. Our review is consistent with other studies suggesting that discussion regarding advance care planning and end‐of‐life care did not destroy hope, cause unnecessary discomfort or anxiety to patients (Davison 2006; Wright 2008).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The chronic and debilitating nature of ESKD indicates that advance care planning should be considered for patients who choose to receive haemodialysis to prepare for future uncertainties while cognitively unimpaired. Advance care planning does not cause unnecessary distress and would help to enhance patients' quality of life at end‐of‐life. However, we found that the concept of advance care planning was inconsistently defined in the literature, and the lack published RCTs may be interpreted as an indication of suboptimal implementation of advance care planning in healthcare settings. The effectiveness and value of advance care directives for people living with ESKD therefore remains largely unresolved.

Implications for research.

Given the lack of evidence for advance care planning for people receiving haemodialysis, large scale, well designed RCTs involving people with ESKD are necessary to determine the efficacy and value of advance care planning for patients. Consistent methods for reporting outcome measures that are patient‐centred and relevant to health services should be further explored before widespread use can be justified. Additionally, consideration should be made for development of a global standardised protocol for advance care planning to facilitate its systematic evaluation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the referees for their feedback and advice during the preparation of this review. We would also like to thank Miss Jia Lin Chua, Miss Suyi Siow and Miss Khai Ho for their initial input to this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

| CINAHL | S43 S36 AND S42 S42 S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 S41 TI (trial) S40 TI (double blind) OR AB (double blind) S39 TI (randomi?e*) OR AB (randomi?e*) S38 AB (placebo) OR AB (randomly) S37 (MH "Clinical Trials+") S36 S22 AND S35 S35 S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 S34 TI (ESRF) OR AB (ESRF) S33 TI (ESRD) OR AB (ESRD) S32 TI (ESKF) OR AB (ESKF) S31 TI (ESKD) OR AB (ESKD) S30 TI (end stage renal) OR AB (end stage renal) S29 TI (endstage renal) OR AB (endstage renal) S28 TI (end stage kidney) OR AB (end stage kidney) S27 TI (endstage kidney) OR AB (endstage kidney) S26 TI (h#emodialysis) OR AB (h#emodialysis) S25 TI (dialysis) or AB (dialysis) S24 TI (renal replacement therapy) OR AB (renal replacement therapy) S23 (MH "Renal Replacement Therapy+") OR (MH "Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy+") OR (MH "Hemodialysis+") OR (MH "Hemofiltration+") OR (MH "Home Dialysis") OR (MH "Peritoneal Dialysis+") S22 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 S21 TI (treatment N5 withdraw*) OR AB (treatment N5 withdraw*) S20 TI (treatment N5 withhold*) OR AB (treatment N5 withhold*) S19 TI (treatment N5 refus*) OR AB (treatment N5 refus*) S18 TI (terminal care) OR AB (terminal care) S17 TI (end of life) OR AB (end of life) S16 TI (power of attorney) OR AB (power of attorney) S15 TI (patient* N5 advocat*) OR AB (patient* N5 advocat*) S14 TI (right to die) OR AB (right to die) S13 TI (living will*) OR AB (living will*) S12 AB (advance N1 decision*) S11 TI (advance N1 decision*) S10 AB (advance N1 directive*) S9 TI (advance N1 directive*) S8 AB (advance care N1 plan) S7 TI (advance care N1 plan*) S6 (MH "Terminal Care+") S5 (MH "Patient Advocacy") S4 (MH "Treatment Refusal") S3 (MH "Right to Die") S2 (MH "Advance Directives+") S1 (MH "Advance Care Planning") |

| Social Work Abstracts | 1 (dialysis or hemodialysis or haemodialysis).mp. 2 (advance adj3 (care or plan or planning or directive*)).mp. 3 (power of attorney or end of life).mp. 4 2 or 3 5 1 and 2 |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random) |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes) |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon) |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kirchhoff 2010.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Pairs of eligible patients and their surrogates were randomised to the control group or the experimental PC‐ACP group using sealed‐envelopes |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Due to the nature of the interview, participants and interventionists could not be blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Did not report if outcome assessors were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All reasons and numbers of dropouts were reported. Intention‐to‐treat analysis conducted |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All stated outcomes reported |

| Other bias | High risk | There were 4 cases where there was neither surrogate nor medical record information was available (out of both CHF and ESKD patients). Two reviewers blinded to group determined what treatment the patient received. For 14 cases, where reviewers could not determine the care received or discrepancy was present, it was referred to an independent Palliative Care Practitioner and expert interdisciplinary panel if necessary. Data from these were used in final data analysis Study did not reach calculated power levels due to resource limitations and hence was stopped early Study was supported by grants from the Agency of Health Care Research and Quality and National Institutes of Health. Two authors were employed by the Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation which owns the rights to the intervention used in the study |

Perry 2005.

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Did not report randomisation method other than "Patients were assigned by random lots". In 5 instances, patients assigned to the peer‐intervention group were moved to a control group by the social worker because of dialysis‐schedule conflicts that prevented peer intervention. In addition, the peer mentor at 1 unit became ill early in the study and could not carry out the peer intervention; therefore, patients at this unit were assigned to the other 2 groups. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and social workers not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Did not report if outcome assessors were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Reasons and numbers for participant drop outs were reported. Patients without follow‐up data were excluded. "A small number of patients did not have follow‐up data and are excluded" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; National Kidney Foundation of Michigan; and National Institute of Mental Health Career grant. Specific support relationships were unclear |

AD ‐ advance directive; CHF ‐ chronic heart failure; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis; M/F ‐ ,male/female; MI ‐ myocardial infarction; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Badzek 2000 | Not RCT; descriptive cross‐sectional study |

| Briggs 2004 | Mixed population, unable to separate data for patients with ESKD |

| Choudry 1995 | Not RCT; review article |

| Dallas 2012 | Wrong population group; children with AIDS |

| den Hoedt 2013 | Examined distribution of death causes in particular cardiovascular deaths; did not report advance care planning |

| Fassett 2011 | Not RCT; review article |

| Friedman 2010 | Not RCT; review article |

| Hodge 2010 | Not RCT; opinion/review |

| Katsube 2011 | Not RCT; questionnaire |

| Lindblad 2010 | Not RCT; questionnaire/survey |

| Manda 2013 | Not RCT; chart review and survey |

| Parker 2009 | Not RCT; summary and conclusions from the End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Steering Committee meeting, did not contain data that could be assessed |

| Singer 1995 | Crossover RCT; assessing which of 3 forms patients would use |

| SPIRIT Pilot Study 2009 | Different interventions; studying recruitment and retention rates for palliative care studies |

| Tangri 2011 | Not RCT; epidemiological study |

| Wright 2009 | Wrong intervention; investigated education in self‐management of CKD |

AIDS ‐ acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Song 2010.

| Methods |

|

| Participants |

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

| Outcomes |

|

| Notes |

|

SPIRIT Study 2013.

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes |

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis; M/F ‐ male/female; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis

Contributions of authors

Draft the protocol: DL, RN, NC, CK, FB, MC

Study selection: RN, DL, NC

Extract data from studies: RN, DL

Enter data into RevMan: RN, DL

Carry out the analysis: DL, RN, NC

Interpret the analysis: DL, RN, NC

Draft the final review: DL, RN, NC, CK, FB, MC

Disagreement resolution: DL, NC

Update the review: DL, NC, RN

Sources of support

Internal sources

Nil, Other.

External sources

Nil, Other.

Declarations of interest

Chi Eung Danforn Lim: none known

Rachel WC Ng: none known

Nga Chong Lisa Cheng: none known

Maria Cigolini: none known

Cannas Kwok: none known

Frank Brennan: none known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Kirchhoff 2010 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL. Effect of a disease‐specific advance care planning intervention on end‐of‐life care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2012;60(5):946‐50. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL. Effect of a disease‐specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2010;58(7):1233‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perry 2005 {published data only}

- Perry E, Swartz J, Brown S, Smith D, Kelly G, Swartz R. Peer mentoring: a culturally sensitive approach to end‐of‐life planning for long‐term dialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2005;46(1):111‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Badzek 2000 {published data only}

- Badzek LA, Cline HS, Moss AH, Hines SC. Inappropriate use of dialysis for some elderly patients: nephrology nurses' perceptions and concerns. Nephrology Nursing Journal: Journal of the American Nephrology Nurses' Association 2000;27(5):462‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Briggs 2004 {published data only}

- Briggs LA, Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Song MK, Colvin ER. Patient‐centered advance care planning in special patient populations: a pilot study. Journal of Professional Nursing 2004;20(1):47‐58. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Choudry 1995 {published data only}

- Choudry NK, Naylor CD. Reflections on supply‐demand mismatch in dialysis services in Ontario. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal 1995;153(5):575‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dallas 2012 {published data only}

- Dallas RH, Wilkins ML, Wang J, Garcia A, Lyon ME. Longitudinal Pediatric Palliative Care: Quality of Life & Spiritual Struggle (FACE): design and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2012;33(5):1033‐43. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

den Hoedt 2013 {published data only}

- Hoedt CH, Bots ML, Grooteman MP, Mazairac AH, Penne EL, Weerd NC, et al. Should we still focus that much on cardiovascular mortality in end stage renal disease patients? The CONvective TRAnsport STudy. PLoS ONE 2013;8(4):e61155. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fassett 2011 {published data only}

- Fassett RG, Robertson IK, Mace R, Youl L, Challenor S, Bull R. Palliative care in end‐stage kidney disease. Nephrology 2011;16(1):4‐12. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Friedman 2010 {published data only}

- Friedman EA. Stressful ethical issues in uremia therapy. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 2010;78(117):S22‐32. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hodge 2010 {published data only}

- Hodge MH. The path to a paradigm shift in hemodialysis. Hemodialysis International 2010;14(1):5‐10. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Katsube 2011 {published data only}

- Katsube M, Akisue Y, Nakamoto H. Recognition of Japanese nurse about “terminal care” and “right to die” in patients on dialysis [abstract]. Peritoneal Dialysis International 2011;31(1 Suppl 1):S22. [EMBASE: 70716134] [Google Scholar]

Lindblad 2010 {published data only}

- Lindblad A, Juth N, Furst CJ, Lynoe N. When enough is enough; terminating life‐sustaining treatment at the patient’s request: a survey of attitudes among Swedish physicians and the general public. Journal of Medical Ethics 2010;36(5):284‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manda 2013 {published data only}

- Manda K, Albert D, Germain M, Puntin G, Hakanson‐Stacy J, Cohen L. Do ESRD patients really want to know prognosis? [abstract]. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2013;61(4):A62. [EMBASE: 71024010] [Google Scholar]

Parker 2009 {published data only}

- Parker TF 3rd, Glassock RJ, Steinman TI. Conclusions, consensus, and directions for the future. Clinics of Journal of American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2009;4 Suppl 1:S129‐44. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Singer 1995 {published data only}

- Singer PA, Thiel EC, Naylor CD, Richardson RM, Llewellyn‐Thomas H, Goldstein M, et al. Life‐sustaining treatment preferences of hemodialysis patients: implications for advance directives. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 1995;6(5):1410‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SPIRIT Pilot Study 2009 {published data only}

- Shields AM, Park M, Ward S, Song MK. Subject recruitment and retention against quadruple challenges in an intervention trial of end‐of‐life communication. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2010;12(5):312‐8. [PUBMED: 2010825388] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MK, Ward S, Lin FC. End‐of‐life decision‐making confidence in surrogates of African‐American dialysis patients is overly optimistic. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2012;15(4):412‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MK, Ward SE, Happ MB, Piraino B, Donovan HS, Shields AM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: an effective approach to preparing African‐American dialysis patients and families for end of life. Research in Nursing & Health 2009;32(3):260‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tangri 2011 {published data only}

- Tangri N, Tighiouart H, Meyer KB, Miskulin DC. Both patient and facility contribute to achieving the centers for Medicare and Medicaid services' pay‐for‐performance target for dialysis adequacy. Journal of American Society of Nephrology 2011;22(12):2296‐302. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wright 2009 {published data only}

- Wright S, Bogan A, Chokshi A. DaVita program advocates self‐management of CKD. Nephrology News & Issues 2009;23(13):28‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Song 2010 {published data only}

- Song MK, Donovan HS, Piraino BM, Choi J, Bernardini J, Verosky D, et al. Effects of an intervention to improve communication about end‐of‐life care among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Applied Nursing Research 2010;23(2):65‐72. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SPIRIT Study 2013 {published data only}

- Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE. Patient perspectives on informed decision‐making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2013;28(11):2815‐23. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MK, Ward SE. The extent of informed decision‐making about starting dialysis: does patients’ age matter?. Nephrology 2014;27(5):571‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, et al. Advance care planning and end‐of‐life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2015;66(5):813‐22. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MK, Ward SE, Lin FC, Hamilton JB, Hanson LC, Hladik GA, et al. Racial differences in outcomes of an advance care planning intervention for dialysis patients and their surrogates. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2016;19(2):134‐42. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

ANZDATA 2012

- McDonald S, Clayton P, Hurst K. Thirty fifth annual report. 2012. www.anzdata.org.au/v1/report_2012.html (accessed 14 April 2016).

Arulkumaran 2012

- Arulkumaran N, Szawarski P, Philips BJ. End‐of‐life care in patients with end‐stage renal disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012;27(3):879–81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2007

- Brown E, Chambers EJ, Eggeling C. End of life care in nephrology: from advanced disease to bereavement. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. [ISBN/ISSN: 9780199211050] [Google Scholar]

Davison 2006

- Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2006;333(7574):886. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davison 2007

- Davison SN, Torgunrud C. The creation of an advance care planning process for patients with ESRD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2007;49(1):27‐36. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davison 2010

- Davison SN. End‐of‐life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2010;5(2):195–204. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JP, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Holley 2003

- Holley JL. Advance care planning in elderly chronic dialysis patients. International Urology & Nephrology 2003;35(4):565‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

KDIGO 2013

- Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 2013;3(1):1‐150. [EMBASE: 2014145464] [Google Scholar]

Levey 2012

- Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2012;379(9811):165‐80. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mallick 1999

- Mallick NP, Gokal R. Haemodialysis. Lancet 1999;353(9154):737‐42. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McAdoo 2012

- McAdoo SP, Brown EA, Chesser AM, Farrington K, Salisbury EM, pan‐Thames renal audit group. Measuring the quality of end of life management in patients with advanced kidney disease: results from the pan‐Thames renal audit group. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012;27(4):1548–54. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Russon 2010

- Russon L, Mooney A. Palliative and end‐of‐life care in advanced renal failure. Clinical Medicine 2010;10(3):279‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simon 2008

- Simon J, Murray A, Raffin S. Facilitated advance care planning: what is the patient experience?. Journal of Palliative Care 2008;24(4):256‐64. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vilar 2011

- Vilar E, Farrington K. Haemodialysis. Medicine 2011;39(7):429‐33. [EMBASE: 2011354231] [Google Scholar]

Weisbord 2003

- Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, Rotondi AJ, Cohen LM, Zeidel ML, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2003;18(7):1345–52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wright 2008

- Wright A, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end‐of‐life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300(14):1665‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Lim 2013

- Lim CE, Siow S, Ho KE, Chua JL, Cheng NC, Kwok C, et al. Advance care planning for haemodialysis patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010737] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]