Abstract

Sexual minorities are at increased risk for substance use and mental health problems. Although previous studies have examined the associations between outness and health outcomes, few have used longitudinal designs or examined differences across subgroups of sexual minorities. To address these gaps, the current study examined sexual orientation and gender as moderators of the longitudinal associations between outness and substance use (cigarettes, marijuana, illicit drugs, and alcohol) and mental health (depression and anxiety). Data were from a sample of 169 sexual minority emerging adults (98 women and 71 men) who provided self-report data at four times over 3.5 years. Results indicated that sexual orientation moderated the within-person associations between outness and changes in health. For bisexual individuals, being more out was associated with increases in marijuana use, illicit drug use, and depression. In contrast, for gay/lesbian individuals, being more out was associated with decreases in illicit drug use and it was not significantly associated with changes in marijuana use or depression. Additionally, outness was not significantly associated with changes in cigarette use, alcohol use, or anxiety for gay/lesbian or bisexual individuals, and gender did not moderate any of the associations. In sum, being more open about one’s sexual orientation had negative consequences for bisexual individuals but not for gay/lesbian individuals. Professionals who work with sexual minorities need to be aware of the potential risks of being open about one’s sexual orientation for bisexual individuals. Interventions are needed to facilitate disclosure decisions and to promote the health of sexual minorities.

Keywords: gay/lesbian, bisexual, outness, substance use, mental health

INTRODUCTION

Sexual minorities are at increased risk for substance use and mental health problems compared to heterosexuals. These disparities begin in adolescence (Marshal et al., 2008, 2011) and persist into adulthood (King et al., 2008; Meyer, 2003; Semlyen, King, Varney, & Hagger-Johnson, 2016), highlighting the need to address them early in development. To do so, it is first necessary to understand the factors that contribute to substance use and mental health problems among sexual minorities. One important factor to consider is outness (or sexual orientation disclosure), which refers to the extent to which a person is open about their sexual orientation with others. While theories of sexual orientation development (Cass, 1979; Troiden, 1989), the coming-out process (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001), and minority stress (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003) emphasize the benefits of being open about one’s sexual orientation, doing so can also lead to negative outcomes, such as becoming the target of prejudice (Pachankis, 2007). As described in the disclosure process model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010), disclosure can have both positive and negative consequences, and the extent to which it leads to specific outcomes depends on various factors (e.g., reactions to disclosure, changes in behavior subsequent to disclosure). Thus, disclosure decisions require sexual minorities to weigh the stress of concealing one’s sexual orientation against the potential risks of disclosure.

In samples of sexual minority adults, most studies have found that outness was cross-sectionally associated with better mental health (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009; Jordan & Deluty, 1998; Juster, Smith, Ouellet, Sindi, & Lupien, 2013; Michaels, Parent, & Torrey, 2016; Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001; Plöderl et al., 2014) but also more substance use (Kipke et al., 2007; Klitzman, Greenberg, Pollack, & Dolezal, 2002; McKirnan & Peterson, 1989; Parks, Hughes, & Kinnison, 2007; Peacock, Andrinopoulos, & Hembling, 2015; Stall et al., 2001; Thiede et al., 2003). For adults, being more open about one’s sexual orientation may improve mental health by decreasing the stress of concealment and increasing access to social support. However, it may also contribute to substance use by increasing exposure to contexts in which substances are used and perceived as normative. Historically, bars have been social centers for sexual minorities, and there is some evidence that reliance on bars to socialize is associated with greater alcohol consumption (Heffernan, 1998; Trocki, Drabble, & Midanik, 2009) and that sexual minorities report more normative perceptions of substance use than heterosexuals (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008). Additionally, being more open about one’s sexual orientation can lead to stigma-related stressors (e.g., discrimination), and previous research has demonstrated that stigma-related stressors are associated with using substances to cope (Feinstein & Newcomb, 2016; Kaysen et al., 2014; Lewis, Mason, Winstead, Gaskins, & Irons, 2016).

Findings have been mixed in samples of sexual minority youth and emerging adults (up to age 25). For this age group, recent cross-sectional studies have found that outness was associated with better mental health (Kosciw et al., 2015; Russell, Toomey, Ryan, & Diaz, 2014) whereas older cross-sectional studies have found that outness was associated with worse mental health (Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2006). These findings could reflect increasing societal acceptance of sexual minorities. Being open about one’s sexual orientation may have been associated with worse mental health in the past, when attitudes toward sexual minorities were more negative, but it may be associated with better mental health now that those attitudes have improved. It is also possible that being more open about one’s sexual orientation may have both positive and negative consequences for youth and emerging adults. The negative consequences may be due to youth and emerging adults having less control over their environments (e.g., living with family members who may not be accepting of their sexual orientation) and possibly having fewer sexual minority peers, role models, and allies. In contrast, a meta-analysis found that neither disclosing one’s sexual orientation to family and friends nor the number of people to whom one has disclosed their sexual orientation were significantly associated with substance use among sexual minority youth and emerging adults (Goldbach, Tanner-Smith, Bagwell, & Dunlap, 2014). The inclusion of studies with youth and emerging adults may have contributed to the non-significant associations between disclosure and substance use, given that youth do not have legal access to cigarettes and alcohol or to venues such as bars and clubs. Goldbach et al. also noted that more research is needed because of the limited number of studies that examined the association between each dimension of disclosure and substance use.

A critical limitation of research in this area is that most studies have been cross-sectional. Therefore, it remains unclear if being more open about one’s sexual orientation is associated with changes in substance use and mental health over time or if sexual minorities who are healthier (e.g., less depressed) are more open about their sexual orientation. In an exception, Aranda et al. (2015) found that disclosure to siblings, but not to parents, was associated with decreases in depression one year later among lesbian adults. In contrast, Rosario, Schrimshaw, and Hunter (2004) found that disclosure to more people was associated with increases in alcohol use, but not cigarette or marijuana use, six months later among sexual minority youth; however, this association was not significant one year later. Based on these contrasting longitudinal findings, it is possible that disclosure may have both positive and negative consequences for sexual minorities.

Additionally, very few studies have examined differences in the associations between outness and health outcomes across subgroups of sexual minorities (e.g., men versus women, gay/lesbian versus bisexual individuals). Three cross-sectional studies have tested gender as a moderator of these associations. One study found that disclosure to family and friends was associated with less heavy drinking for young gay men and lesbian women (Baiocco, D’Alessio, & Laghi, 2010), one study found that disclosure to a parent was associated with lower odds of depression and illicit drug use for sexual minority women but not for sexual minority men (Rothman, Sullivan, Keyes, & Boehmer, 2012), and one study found that being out was associated with higher odds of depression for sexual minority men but not for sexual minority women (Pachankis, Cochran, & Mays, 2015). Together, these studies suggest that being open about one’s sexual orientation may be protective against negative health outcomes for sexual minority women, but findings are mixed for sexual minority men.

Sexual orientation has received less attention as a moderator of the associations between outness and health outcomes. However, being more open about one’s sexual orientation may be particularly likely to lead to negative consequences for bisexual individuals because it can put them at risk for rejection and discrimination from both heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals (Brewster & Moradi, 2010). People have more negative attitudes toward bisexual individuals than toward gay/lesbian individuals (Herek, 2002), which are rooted in stereotypes about bisexuality (e.g., that bisexuality is not a stable sexual orientation, that bisexual individuals are promiscuous; Brewster & Moradi, 2010; Mohr & Rochlen, 1999). As a result, bisexual individuals experience rejection and discrimination from heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals, which could lead to experiencing depression and anxiety and to using substances to cope (for a review, see Feinstein & Dyar, 2017). Consistent with this, Feinstein, Dyar, and London (2017) found that being more open about one’s sexual orientation was associated with more alcohol/drug abuse for bisexual women but not for lesbian or queer women. These findings provide preliminary support for gender and sexual orientation as moderators of the associations between outness and health outcomes. However, the conclusions that can be drawn from these studies are limited because they were all cross-sectional, and none of them examined gender and sexual orientation as moderators in the same sample. Additionally, all of the studies had primarily White samples, highlighting the need for additional research to understand the extent to which previous findings generalize to racially/ethnically diverse samples of sexual minorities.

As such, the goals of the current study were to examine sexual orientation, gender, and their interaction as moderators of the within-person associations between outness and changes in substance use (cigarettes, marijuana, illicit drugs, and alcohol) and mental health (depression and anxiety) using four waves of data from a longitudinal study of racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youth. Our within-person, longitudinal design had several advantages over the commonly used between-person, cross-sectional design. By examining within-person associations, we were able to test the extent to which a person’s level of outness at a given time (relative to their average level of outness across times) was associated with changes in health over time. In contrast, between-person, cross-sectional studies have only been able to test the average associations between outness and health at a single time. Given that very few studies have examined sexual orientation or gender as moderators of these associations, we considered our study exploratory. We hypothesized that sexual orientation would moderate the within-person associations between outness and changes in health, such that being more open about one’s sexual orientation would be associated with increases in negative health outcomes for bisexual individuals but not for gay/lesbian individuals. We did not make a priori hypotheses about gender as a moderator, because previous findings have been mixed and did not account for sexual orientation.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Project Q2 was a cohort study focused on predictors of mental health, substance use, and HIV risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth living in Chicago. Inclusion criteria required participants to be 16–20 years old at baseline and to either self-identify as LGBTQ, report same-sex attraction, or report same-sex sexual behavior. Participants provided up to eight waves of data over five years between 2007 and 2014. This accelerated longitudinal design (Tonry, Ohlin, & Farrington, 1991) allowed for the assessment of developmental changes across a wider age range than if all participants were the same age at baseline. An incentivized snowball sampling approach was used for recruitment, in which an initial convenience sample was recruited through flyers posted in LGBTQ neighborhoods and online (38% of the baseline sample), and then those participants recruited their peers (62% of the baseline sample). Prior to enrollment, decisional capacity was assessed and informed consent was obtained. At each assessment, participants completed a battery of self-report measures using a computer-assisted self-interview. Participants were paid $25–$50 for each assessment.

The current analyses used data from the 18-, 24-, 48-, and 60-month follow-up assessments. We focused on these waves because outness was only assessed at 18 and 48 months. We included the subsequent waves (24 and 60 months) to test longitudinal associations between outness at one wave (18 and 48 months) and health at the next wave (24 and 60 months), controlling for health at the previous wave (18 and 48 months). The full sample included 248 individuals, but the analytic sample included 169. We excluded 23 individuals who were missing data from the waves when outness was assessed, 16 individuals with sexual orientations other than LGB, 25 individuals who reported different sexual orientations at different waves, and 15 individuals for whom identification checks at later waves revealed that they were not 16–20 years old at the baseline assessment (which was a requirement for participation). We could not include individuals with sexual orientations other than LGB because there were too few to consider them a separate group. Furthermore, we could not include individuals who reported different sexual orientations at different waves because they were too heterogeneous to consider them a separate group. Some reported one change, others reported multiple changes, and changes did not demonstrate a consistent pattern.

The resulting analytic sample (n = 169) included 124 gay/lesbian individuals (51.6% women; n = 64) and 45 bisexual individuals (75.5% women; n = 34). The majority was cisgender (55.6% cisgender women, 41.4% cisgender men, 2.4% transgender women, and 0.5% transgender men). The analytic sample was racially/ethnically diverse, with 55.6% Black/African American, 16.0% White/Caucasian, 12.4% Hispanic or Latino/a, and 16.0% other (i.e., Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, multiracial, and other). The large proportion of racial/ethnic minorities was due to the demographics of the city in which the study was conducted and the incentivized snowball sampling approach. At the first wave used in the analyses, participants ranged in age from 18 to 22 (M = 20.73, SD = 1.29). See Table 1 for additional demographics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the analytic sample (N = 169).

| Variable | # (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender and sexual orientation | |

| Lesbians | 64 (37.9%) |

| Gay men | 60 (35.5%) |

| Bisexual women | 34 (20.1%) |

| Bisexual men | 11 (6.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 27 (16.0%) |

| Black/African American | 94 (55.6%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 21 (12.4%) |

| Other | 27 (16.0%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| At least some college | 82 (48.5%) |

| High school | 33 (19.5%) |

| Partial high school or less | 30 (17.7%) |

| Missing at 18-month follow-up | 24 (14.3%) |

| Living Status | |

| Living with parents | 78 (46.1%) |

| Not living with parents | 71 (42.0%) |

| Missing at 18-month follow-up | 20 (11.9%) |

Measures

Demographics

At baseline, we assessed age and race/ethnicity (Black, White, Latino/a, and other). At 18 months, we assessed gender (man = 0, woman = 1), sexual orientation (gay/lesbian = 0, bisexual = 1), highest level of education completed (less than high school, high school, and at least some college), and living situation (with parents = 0; not with parents = 1).

Outness

At 18 and 48 months, participants were asked about their outness to eight people. We expanded a measure from D’Augelli, Hershberger, and Pilkington (1998), who assessed outness to one’s mother, father, and siblings, to assess outness to a larger number of people. Participants were asked, “Do the following people know your sexual orientation (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual) or gender identity (e.g., transgender)?” Participants answered this question in regard to their (1) mother/stepmother, (2) father/stepfather, (3) closest sister, (4) closest brother, (5) best heterosexual female friend, (6) best heterosexual male friend, (7) closest teacher/academic advisor/professor, and (8) boss/employer. Response options included (1) definitely knows and we have talked about it, (2) definitely knows and we have never talked about it, (3) probably knows or suspects, and (4) does not know or suspect. Participants could also indicate “not applicable” if they did not have such a person in their lives. Responses were recoded such that higher values represented more outness and then averaged across items (excluding items with “not applicable” responses). The range of possible scores was 1–4, and inter-item reliability was high (α = .83–.95). The average amount of change in outness over time was small (M = .14), but there was considerable variability (SD = .69; range = −2.25–2.88).

In sensitivity analyses (described in the analytic plan), we examined outness to three groups of people: family (mother/stepmother, father/stepfather, closest sister, and closest brother; α = .83–.90), heterosexual friends (best heterosexual male friend and best heterosexual female friend; α = .72–.87), and others (closest teacher/academic advisor/professor and boss/employer; α = .73–.76). If a participant selected “not applicable” for all individuals in a group at a given wave of data collection, then their data from that wave were not included in analyses focused on outness to that group (n = 3 for family, 10 for heterosexual friends, and 56 for other).

Cigarette use

At all waves, participants were asked, “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?” Those who said yes were asked, “How many cigarettes a day do you smoke?” Our measure was similar to the National Youth Tobacco Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017), but we adapted the timeframe to reflect the amount of time in between our waves of data collection and allowed participants to respond in an open-ended manner rather than providing them with a Likert-type scale. Those who reported smoking 0 cigarettes per day were coded as non-smokers. Values ranged from 0 to 60, but 95.4% of participants reported smoking fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. To reduce the impact of outliers, values greater than 3 SD above the mean (17.27) were transformed to 17. The resulting variable remained overdispersed (M = 2.14, SD = 3.78), so we used negative binomial regression. The average amount of change in cigarette use over time was small (M = −.09), but there was considerable variability (SD = 3.51; range = −17.00–15.00).

Marijuana use

At all waves, participants were asked, “In the last 6 months, did you use marijuana?” Those who said yes were asked, “In the last 6 months, how many times did you use marijuana?” Our measure was similar to the measure used in Monitoring the Future (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2017), but we adapted the timeframe to reflect the amount of time in between our waves of data collection and we allowed participants to respond in an open-ended manner rather than providing them with a Likert-type scale. Responses ranged from 0 to 10,000, but 94.7% of participants reported using marijuana 190 times or fewer in the last six months. To reduce the impact of outliers, the top 5% (values of 191 to 10,000) were transformed to values of 191.1 The resulting variable remained overdispersed (M = 32.90, SD = 58.20), so we used negative binomial regression. The average amount of change in marijuana use was 8.57, but there was considerable variability (SD = 47.74; range = −180.00–191.00).

Illicit drug use

At all waves, participants were asked, “In the last 6 months, did you use [illicit drug]?” Illicit drugs included cocaine, methamphetamines, and club drugs (ecstasy, ketamine, and GHB). Those who said yes were asked, “In the last 6 months, how many times did you use [illicit drug]?” Our measure was modeled after our measure of marijuana use. Endorsement was low across waves (0.7–2.7% for methamphetamines, 4.1–8.2% for cocaine, and 2.7–9.6% for club drugs), so we created a single dichotomous variable for any illicit drug use at each wave. Any illicit drug use was endorsed by 7.0–13.5% of the sample across waves (7.0% at 18 months, 10.3% at 24 months, 10.8% at 48 months, and 13.5% at 60 months).

Alcohol use

At all waves, participants were asked, “In the last 6 months, did you use alcohol (beer, wine, liquor, etc.)?” Those who said yes were asked two follow-up questions about frequency and quantity. First, they were asked, “In the last 6 months, how many days did you drink alcohol?” Then, they were asked, “Think of all the times you have had a drink during the last 6 months. How many drinks did you usually have each time?” Responses to the frequency question ranged from 0 to 180, but 94.8% of participants reported 91 or fewer drinking days in the last six months. To reduce the impact of outliers, the top 5% were recoded to the 95th percentile score (90).1 Responses to the quantity question ranged from 1 to “6 or more” standard drinks. Participants who had not used alcohol in the last six months were coded as 0 for both frequency and quantity. Consistent with previous research (Bartholow & Heinz, 2006; Greenfield, 2000), quantity and frequency were multiplied to create an index of alcohol use. The variable remained overdispersed (M = 68.50, SD = 112.16), so we used negative binomial regression. The average amount of change in alcohol use was −6.04, but there was considerable variability (SD = 100.78; range = −546.00–434.00).

Depression and anxiety

At all waves, the Brief Symptoms Inventory (Derogatis, 2001) was used to assess depression and anxiety symptoms in the past week. Participants were asked to indicate, “How much has [symptom] distressed or bothered you in the last seven days?” for 12 symptoms (six for depression, such as “feeling blue,” and six for anxiety, such as “feeling fearful”). Items were rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), and responses were averaged across items (α = .86–.88 for depression and .87–.88 for anxiety). To facilitate interpretation, scores were standardized (i.e., grand-mean centered and divided by the grand SD). Although the average amount of change in depression and anxiety over time was small (M = .08 for depression and .02 for anxiety), there was considerable variability (for depression, SD = .83, range = −2.83–3.00; for anxiety, SD = .73, range = −2.83–2.67).

Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 7.

Preliminary analyses

Prior to conducting our primary analyses, we conducted a series of preliminary analyses to examine the bivariate associations among our variables. This included bivariate associations (1) among our health outcomes, (2) between gender/sexual orientation and outness/health outcomes, and (3) between outness and health outcomes in the full sample (i.e., without moderators or covariates). First, we examined the bivariate associations among our health outcomes. For continuous and binary variables, we used multilevel correlation (i.e., within- and between-person correlation). Within-person correlations reflect the extent to which a person’s score on one variable at a given time (relative to their average score on that variable across times) is associated with their score on another variable at that given time (relative to their average score on that variable across times). Between-person correlations reflect the extent to which a person’s average score on one variable across times is associated with their average score on another variable across times. For count variables, we used bivariate multilevel negative binomial regression because multilevel correlation is not appropriate. Bivariate multilevel negative binomial regression produces odds ratios (ORs), but interpretation of the within- and between-person levels is similar to interpretation of within- and between-person correlations. Second, we examined the bivariate associations between gender/sexual orientation and outness/health outcomes at the between-person level (i.e., gender/sexual orientation differences in outness/health outcomes). Again, we used bivariate multilevel correlations and bivariate multilevel binomial regression. Third, we examined the bivariate associations between outness and health outcomes in the full sample using the same types of analyses.

Primary analyses

The goals of our primary analyses were to test sexual orientation, gender, and their interaction as moderators of the within-person associations between outness and changes in health over time. We used multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) with robust maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Missing data (11.0%) were handled using full information maximum likelihood. Similar to other multilevel approaches, MSEM separates within- and between-person variance to allow for tests of within- and between-person effects, but it estimates between-person variables with less bias than other multilevel approaches (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010). MSEM treats repeated measures as indicators of latent variables, which estimate the variable at the between-person level while adjusting for non-independence at the within-person level (Lüdtke et al., 2008; Marsh et al., 2009). The within-person level consisted of repeated measures nested within individuals (i.e., the between-person level).

We tested separate models for each health outcome. In each model, the lagged health outcome (at 24 or 60 months) was predicted by outness (at 18 or 48 months), controlling for the unlagged health outcome (at 18 or 48 months). All intercepts (i.e., the average level of each outcome at the between-person level) were allowed to vary between persons (i.e., they were treated as random effects). The within-person association between outness and the lagged health outcome (representing the effect of outness on change in the health outcome) was treated as a random effect, because it was expected to vary based on sexual orientation and gender. To test moderation, we initially included sexual orientation, gender, and their interaction as between-level predictors of the within-person associations between outness and the lagged health outcomes. However, the interaction was not significant in any of the analyses. Therefore, we removed the interaction. To control for the between-person effects of the moderators and covariates, we included sexual orientation, gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, living situation, and average outness as predictors of the lagged health outcomes at the between-person level. The within-person associations reflect the extent to which a person’s level of outness at a given time (relative to their average level of outness across times) is associated with their change in each health outcome. The between-person associations reflect the extent to which a person’s average level of outness across time is associated with their average level of each health outcome across times. Significant sexual orientation or gender effects were followed with simple slope tests to understand the associations for specific groups.

Sensitivity analyses

Finally, we conducted two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, to ensure that our results were not being influenced by our small number of transgender participants, we conducted our analyses without the five transgender participants. The pattern of results was the same. Therefore, in the interest of being inclusive, we report the results of the analyses that included the transgender participants. Second, we examined whether the pattern of results was the same across different dimensions of outness (i.e., outness to family, heterosexual friends, and others). The pattern of results was the same for overall outness and outness to specific groups of people, but there were a few exceptions (discussed at the end of the results).

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Means and variances for all variables are shown in Table 2. Correlations and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for continuous and dichotomous variables are also shown in Table 2. Bivariate associations for count variables (from bivariate multilevel negative binomial regression models) are shown in Table 3. ICCs for continuous and dichotomous variables (outness, illicit drug use, depression, and anxiety) ranged from .35 to .51, indicating that there was substantial variance at the within- and between-person levels. ICCs are not appropriate for count variables (cigarette, marijuana, and alcohol use).

Table 2.

Correlations, means, variances, and intra-class correlations.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | .21* | .01 | .09 | −.02 | −.03 |

| 2. Sexual Orientation | - | −.55** | .20* | .10 | −.06 | |

| 3. Outness | - | −.01 | .05 | .14 | ||

| 4. Depression | −.06 | - | .80** | .18* | ||

| 5. Anxiety | .03 | .58** | - | .20* | ||

| 6. Illicit Drug Use | .01 | .14* | .16* | - | ||

| Mean | 3.47 | .72 | .56 | .08 | ||

| Within Variance | .24 | .35 | .26 | .07 | ||

| Between Variance | .19 | .31 | .30 | .04 | ||

| ICC | .46 | .41 | .51 | .35 |

Notes. Between-level correlations are above the diagonal and within-level correlations are below the diagonal. Outness is measured at 18 and 48 months, and depression, anxiety, and illicit drug use are measured at 24 and 60 months. Cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use are not included in this table because they are count variables (see “Measures” and Table 3). Gender is coded as male = 0 and female = 1. Sexual orientation is coded as gay/lesbian = 0 and bisexual =1.

p < .05

p < .01.

Table 3.

Bivariate negative binomial regression analyses predicting cigarette, marijuana, and alcohol use.

| Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Use | Marijuana Use | Alcohol Use | |||||

| Level | Predictor | b (SE) | eb | b (SE) | eb | b (SE) | eb |

| Within | Outness | .18 (.20) | 1.20 | .48 (.28) | 1.62 | −.23 (.51) | .79 |

| Between | Outness | −.65 (.18)** | .52 | −.05 (.04) | .95 | 1.20 (.26)** | 3.32 |

| Sexual Orientation | .04 (.28) | 1.04 | −.12 (0.31) | .89 | .09 (.27) | 1.09 | |

| Gender | .10 (.30) | 1.11 | −.21 (.01)** | .81 | −.30 (.23) | .74 | |

Notes. Separate models were tested for each outcome variable. eb represents the rate parameter (multiplicative increase in outcome associated with a one unit increase in the predictor). Outness is measured at 18 and 48 months, and cigarette, marijuana, and alcohol use are measured at 24 and 60 months. Gender is coded as male = 0 and female = 1. Sexual orientation is coded as gay/lesbian = 0 and bisexual = 1.

p < .05

p < .001.

Gender/sexual orientation differences in outness and health outcomes

Results are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Bivariate associations at the between-person level (averaged across waves and not including covariates) indicated that bisexual individuals reported lower outness and higher depression than gay/lesbian individuals, and men reported more marijuana use than women. None of the other sexual orientation or gender differences were significant.

Associations between outness and health outcomes in the full sample

Results are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Bivariate associations between outness and health in the full sample (not including moderators or covariates) indicated that being more out was associated with more alcohol use and less cigarette use at the between-person level (averaged across waves). None of the other between-person associations between outness and health outcomes were significant, and none of the within-person associations between outness and changes in health outcomes were significant.

Primary Analyses

Results are shown in Table 4 (for substance use) and Table 5 (for mental health). Gender did not moderate any of the within-person associations between outness and changes in health outcomes over time. Therefore, we do not describe these non-significant findings below. Instead, we focus on the findings for sexual orientation as a moderator. Simple slope tests were used to understand significant moderation effects. Rate ratios (RRs) and odds ratios (ORs) from simple slope tests are reported in-text. As noted, although our hypotheses focused on within-person associations, our models also included associations at the between-person level (i.e., averaged across waves). Therefore, we report both associations for each health outcome. In Tables 4 and 5, the between-person effects and the within-person effect of each unlagged health outcome are presented under the subheading “intercept.” Effects related to the slope of the association between outness and each health outcome are presented under the subheading “slope” (including the average within-person slope and the variance in the within-person slope). Moderation effects are indicated in bold font (gender ➔ slope and sexual orientation ➔ slope).

Table 4.

Multilevel models of outness predicting substance use.

| Outcome | Predictor | b | exp(b) | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Cigarette Use | Intercept | 1.34 | 3.82 | .45 | 2.99 | .003 |

| Unlagged Cigarette Use | .27 | 1.31 | .28 | 8.08 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | 1.24 | 3.46 | .30 | 4.16 | < .001 | |

| Gender | −.99 | .37 | .34 | −2.94 | .003 | |

| Outness | .64 | 1.90 | .33 | 1.92 | .05 | |

| Race: Black | −.65 | .52 | .28 | −2.28 | .02 | |

| Race: Latino | .03 | 1.03 | .60 | .05 | .96 | |

| Race: Other | .22 | 1.25 | .76 | .29 | .77 | |

| Age at baseline | .08 | 1.08 | .18 | .45 | .65 | |

| Education: High school | −1.10 | .33 | .55 | −1.98 | .05 | |

| Education: At least some college | −1.15 | .32 | .35 | −3.28 | < .001 | |

| Living Situation | −.39 | .68 | .38 | −1.03 | .30 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Cigarette Use) | ||||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −1.44 | .24 | 1.20 | −1.20 | .23 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .61 | .46 | 1.33 | .18 | ||

| Gender → Slope | 1.59 | 1.27 | 1.24 | .21 | ||

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | .94 | .49 | 1.93 | .05 | ||

| Lagged Marijuana Use | Intercept | 3.12 | 22.65 | 1.13 | 2.77 | .01 |

| Unlagged Marijuana Use | .02 | 1.02 | .003 | 6.81 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .55 | 1.73 | 1.52 | .36 | .72 | |

| Gender | −.39 | .68 | 1.06 | −.37 | .71 | |

| Outness | .66 | 1.93 | 1.71 | .38 | .70 | |

| Race: Black | −.01 | .99 | .83 | −.02 | .99 | |

| Race: Latino | −.37 | .69 | 1.00 | −.37 | .71 | |

| Race: Other | .01 | 1.01 | .65 | .01 | .99 | |

| Age at baseline | .33 | 1.39 | .32 | 1.03 | .30 | |

| Education: High school | −.16 | .85 | 1.31 | −.12 | .90 | |

| Education: At least some college | −.91 | .40 | .62 | −1.45 | .15 | |

| Living Situation | −.35 | .70 | .82 | −.42 | .67 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Marijuana Use) | ||||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.71 | .49 | .48 | −1.47 | .14 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .33 | .23 | 1.40 | .16 | ||

| Gender → Slope | −.01 | .37 | −.04 | .97 | ||

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | 1.79 | .83 | 2.16 | .03 | ||

| Lagged Illicit Drug Use | Intercept | −3.46 | .03 | 1.08 | 3.20 | < .001 |

| Unlagged Illicit Drug Use | 4.46 | 86.49 | .02 | 4.14 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .68 | 1.97 | .83 | .82 | .41 | |

| Gender | −.83 | .44 | .51 | −1.63 | .10 | |

| Outness | 4.13 | 62.18 | .75 | 5.48 | < .001 | |

| Race: Black | −.71 | .49 | .38 | −1.86 | .06 | |

| Race: Latino | .14 | 1.15 | .40 | .34 | .73 | |

| Race: Other | 1.06 | 2.89 | .74 | 1.43 | .15 | |

| Age at baseline | −.43 | .65 | .32 | −1.36 | .17 | |

| Education: High school | −2.36 | .09 | .57 | −4.11 | < .001 | |

| Education: At least some college | −.96 | .38 | .61 | −1.58 | .11 | |

| Living Situation | .55 | 1.73 | .75 | .73 | .46 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Illicit Drug Use) | ||||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −1.35 | .26 | .61 | −2.21 | .03 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .44 | .30 | 1.47 | .14 | ||

| Gender → Slope | .85 | .66 | 1.29 | .20 | ||

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | 2.54 | .39 | 6.47 | < .001 | ||

| Lagged Alcohol Use | Intercept | 3.65 | 38.47 | .21 | 17.62 | < .001 |

| Unlagged Alcohol Use | .005 | 1.01 | .001 | 6.26 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .38 | 1.46 | .17 | 2.20 | .03 | |

| Gender | .00 | 1.00 | .18 | .01 | .99 | |

| Outness | .37 | 1.45 | .14 | 2.62 | .01 | |

| Race: Black | −.62 | .54 | .17 | −3.56 | < .001 | |

| Race: Latino | −.39 | .68 | .19 | −2.03 | .04 | |

| Race: Other | .04 | 1.04 | .30 | .15 | .88 | |

| Age at baseline | .22 | 1.25 | .06 | 3.57 | < .001 | |

| Education: High school | .36 | 1.43 | .14 | 2.69 | .01 | |

| Education: At least some college | .10 | 1.11 | .34 | .29 | .77 | |

| Living Situation | −.03 | .97 | .24 | −.13 | .89 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Alcohol Use) | ||||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.45 | .64 | .52 | −.85 | .390 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .72 | .31 | 2.33 | .02 | ||

| Gender → Slope | −.23 | .78 | −.29 | .77 | ||

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | 1.60 | .59 | 2.72 | .01 |

Notes. White is the reference group for the dummy coded race variables. Gender is coded as male = 0 and female = 1. Sexual orientation is coded as gay/lesbian = 0 and bisexual = 1. Age at baseline is grand-mean centered.

Table 5.

Multilevel models of outness predicting mental health.

| Outcome | Predictor | b | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Symptoms | Intercept | .01 | .28 | .04 | .97 |

| Unlagged Depression | .43 | .08 | 5.35 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .23 | .24 | .94 | .35 | |

| Gender | −.08 | .15 | −.52 | .60 | |

| Outness | −.36 | .50 | −.73 | .46 | |

| Race: Black | .18 | .18 | .98 | .33 | |

| Race: Latino | .13 | .32 | .41 | .68 | |

| Race: Other | −.01 | .24 | −.06 | .95 | |

| Age at baseline | .06 | .05 | 1.07 | .29 | |

| Education: High school | −.06 | .30 | −.22 | .83 | |

| Education: At least some college | −.19 | .39 | −.49 | .62 | |

| Living Situation | .18 | .32 | .58 | .56 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Depression) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.33 | .59 | −.57 | .57 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .15 | .08 | 1.86 | .06 | |

| Gender → Slope | .18 | .64 | .29 | .77 | |

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | .81 | .200 | 3.97 | < .001 | |

| Anxiety Symptoms | Intercept | .06 | .16 | .35 | .72 |

| Unlagged Anxiety | .45 | .09 | 4.78 | < .001 | |

| Sexual Orientation | .20 | .52 | .38 | .70 | |

| Gender | −.05 | .25 | −.22 | .83 | |

| Outness | −.21 | .49 | −.42 | .67 | |

| Race: Black | −.32 | .13 | −2.45 | .01 | |

| Race: Latino | −.26 | .34 | −.78 | .43 | |

| Race: Other | −.11 | .13 | −.86 | .39 | |

| Age at baseline | .05 | .19 | .26 | .80 | |

| Education: High school | .28 | .23 | 1.21 | .23 | |

| Education: At least some college | .06 | .42 | .15 | .88 | |

| Living Situation | .22 | .39 | .57 | .57 | |

| Slope (Outness → Lagged Anxiety) | |||||

| Fixed Effect (average slope) | −.40 | 3.29 | −.12 | .90 | |

| Random Effect (variance of slope) | .33 | .18 | 1.84 | .07 | |

| Gender → Slope | .49 | 3.92 | .13 | .90 | |

| Sexual Orientation → Slope | .59 | .50 | 1.19 | .23 |

Notes. White is the reference group for the dummy coded race variables. Gender is coded as male = 0 and female = 1. Sexual orientation is coded as gay/lesbian = 0 and bisexual =1. Age at baseline is grand-mean centered. Depression and anxiety symptoms are grand-mean centered.

Cigarette use

At the within-person level, there was a trend toward sexual orientation moderating the association between outness and change in cigarette use (b = .94, SE = .49, z = 1.93, p = .053). However, outness was not significantly associated with change in cigarette use for bisexual (b = .44, SE = .55 z = .79, p = .43, RR = 1.55) or gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.50, SE = .57, z = −.88, p = .38, RR =.61) (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Association between within-person outness and change in cigarette use as a function of sexual identity. Being more out was not associated with change in cigarette use for bisexual individuals (b = .44, SE = .55 z = .79, p = .43, RR = 1.55) or gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.50, SE = .57, z = −.88, p = .38, RR =.61). Expected cigarette use is calculated holding all covariates at their means.

At the between-person level, there were several significant predictors of cigarette use (averaged across waves). Average cigarette use was higher among bisexual individuals (estimate = .59, SE = .32, eest = 1.80) compared to gay/lesbian individuals (estimate = −.64, SE = .38, eest = .53), men (estimate = .30, SE = .20, eest = 1.35) compared to women (estimate = −.70, SE = .47, eest = .50), White individuals (estimate = .03, SE = .44, eest = 1.03) compared to Black individuals (estimate = −.62, SE = .26, eest = .54), and individuals with less than a high school education (estimate = .59, SE = .29, eest = 1.80) compared to those with a high school education (estimate = −.51, SE = .61, eest = .60) or some college (estimate = −.55, SE = .41, eest = .58). Average cigarette use was also higher among individuals who reported higher average outness (see Table 4).

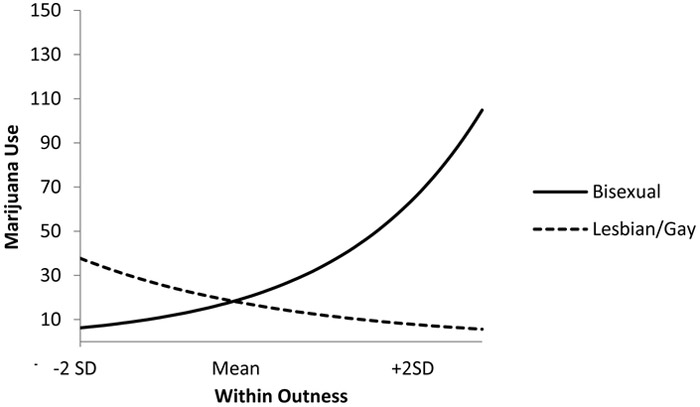

Marijuana use

At the within-person level, sexual orientation significantly moderated the association between outness and change in marijuana use. Being more out was associated with increases in marijuana use for bisexual individuals (b = 1.07, SE = .40 z = 2.63, p = .01, RR = 2.91) but not for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.72, SE = .51, z = −1.40, p = .16, RR =.49) (see Fig. 2). At the between-person level, there were no significant predictors of marijuana use.

Figure 2.

Association between within-person outness and change in marijuana use as a function of sexual identity. Being more out was associated with increases in marijuana use for bisexual individuals (b = 1.07, SE = .40 z = 2.63, p = .01, RR = 2.91) but not for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.72, SE = .51, z = −1.40, p = .16, RR =.49). Expected marijuana use is calculated holding all covariates at their means.

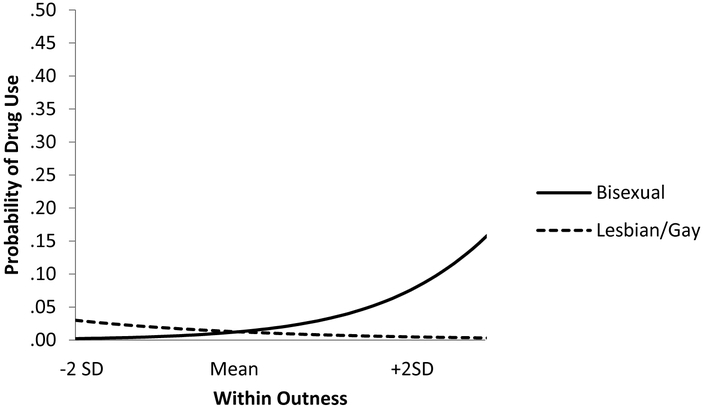

Illicit drug use

At the within-person level, sexual orientation significantly moderated the association between outness and change in illicit drug use. Being more out was associated with increases in the odds of illicit drug use for bisexual individuals (b = 1.68, SE = .42, z = 4.00, p < .001, OR = 5.36) and with decreases in the odds of illicit drug use for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.85, SE = .43, z = −1.99, p = .046, OR = .43) (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Association between outness and change in illicit drug use as a function of sexual identity. Being more out was associated with increases in the odds of illicit drug use for bisexuals (b = 1.68, SE = .42, z = 4.00, p < .001, OR = 5.36) and with decreases for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.85, SE = .43, z = −1.99, p = .046, OR = .43). Expected probability of illicit drug use is calculated holding all covariates at their means.

At the between-person level, odds of illicit drug use (averaged across waves) were higher among individuals with less than a high school education (estimate = −3.33, SE = .59, probability = .03) compared to those with a high school education (estimate = −4.29, SE = .30, probability = .01) and among individuals with higher average outness (see Table 4).

Alcohol use

At the within-person level, sexual orientation significantly moderated the association between outness and change in alcohol use. Being more out was associated with a non-significant increase in alcohol use for bisexual individuals (b = 1.02, SE = .60, z = 1.69, p = 09, RR = 2.77) and a non-significant decrease in alcohol use for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.58, SE = .34, z = −1.73, p = .08, RR = .56) (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Association between outness and change in alcohol use as a function of sexual identity. Being more out was associated with marginally significant increases in alcohol use for bisexual individuals (b = 1.02, SE = .60, z = 1.69, p = 09, RR = 2.77) and marginally significant decreases for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.58, SE = .34, z = −1.73, p = .08, RR = .56). Expected alcohol use is calculated holding all covariates at their means.

At the between-person level, there were several significant predictors of alcohol use (averaged across waves). Average alcohol use was higher among bisexual individuals (estimate = 4.21, SE = .21, eest = 67.36) compared to gay/lesbian individuals (estimate = 3.83, SE = .18, eest = 46.06), White individuals (estimate = 4.32, SE = .22, eest = 75.19) compared to Black (estimate = 3.70, SE = .33, eest = 40.45) and Latino/a individuals (estimate = 3.93, SE = .15, eest = 50.91), and individuals with a high school education (estimate = 3.90, SE = .36, eest = 49.40) compared to those with less than a high school education (estimate = 3.80, SE = .11, eest = 44.70). Additionally, individuals who were older (at baseline) and those who reported higher average outness also reported higher average alcohol use (see Table 4).

Depression

At the within-person level, sexual orientation significantly moderated the association between outness and change in depression. Being more out was associated with increases in depression for bisexual individuals (b = .58, SE = .27, z = 2.15, p = .03) but not for gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.23, SE = .24, z = −.95, p = .34). See Figure 5. At the between-person level, there were no significant predictors of depression.

Figure 5.

Association between outness and change in depression as a function of sexual identity. Being more out was associated with increases in depression for bisexual individuals (b = .58, SE = .27, z = 2.15, p = .03) but not gay/lesbian individuals (b = −.23, SE = .24, z = −.95, p = .34). Expected depression is calculated holding all covariates at their means.

Anxiety

At the within-person level, sexual orientation did not significantly moderate the association between outness and change in anxiety. Additionally, there was not a significant main effect of outness on change in anxiety. Therefore, outness was not associated with change in anxiety for any subgroups of sexual minorities. At the between-person level, anxiety (averaged across waves) was higher among White individuals (M = .28, SE = .13) than Black individuals (M = −.03, SE = .24).

Sensitivity Analyses

Finally, we examined whether our findings differed across dimensions of outness (i.e., outness to family, heterosexual friends, and others). Overall, the pattern of results described above (for overall outness) was the same as the pattern of results for outness to family and heterosexual friends. In contrast, the pattern of results was different for outness to others; sexual orientation moderated the within-person association between outness to others and change in cigarette use, but none of the other health outcomes. However, we may have been underpowered to detect significant associations for outness to others, because 56 observations were excluded from these analyses (due to participants who did not have any “other” individuals in their lives).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have examined the associations between outness and health, but few have utilized longitudinal designs or examined differences across subgroups of sexual minorities. To address these gaps, we used longitudinal data to examine sexual orientation and gender as moderators of the within-person associations between outness and changes in health in a racially/ethnically diverse sample of sexual minorities. Overall, results indicated that the within-person associations between outness and changes in health depended on sexual orientation. Consistent with our hypotheses, being more open about one’s sexual orientation had negative consequences for bisexual individuals. In contrast, most of the associations between outness and changes in health were not significant for gay/lesbian individuals (with the exception of outness being associated with lower odds of illicit drug use for gay/lesbian individuals). Additionally, gender did not moderate the within-person associations between outness and changes in health.

First, we found that being more open about one’s sexual orientation was associated with increases in marijuana use, illicit drug use, and depression for bisexual individuals. This is consistent with previous findings that outness was cross-sectionally associated with higher alcohol and drug abuse for bisexual women, but not for lesbian or queer women (Feinstein et al., 2017). However, Feinstein et al. used a cross-sectional design and focused exclusively on sexual minority women and susbtance abuse. Therefore, our findings extend theirs to bisexual men as well as women and to depression as well as marijuana and illicit drug use. Our findings also provide evidence that there are longitudinal associations between outness and negative health outcomes for bisexual individuals. However, given that our sample included only 45 bisexual individuals, these findings should be interpreted with caution until they are replicated. We were not able to determine why outness was associated with increases in substance use and depression for bisexual individuals. However, Feinstein et al. found that the association between outness and drug abuse among bisexual women was mediated by LGBT community involvement and discrimination. They suggested that bisexual women who were more open about their sexual orientation may have become more involved in the LGBT community, putting them at risk for discrimination from gay/lesbian individuals and leading to using drugs to cope. As such, outness may have been associated with increases in substance use and depression for the bisexual individuals in our study because it may have exposed them to discrimination from both heterosexual and gay/lesbian individuals.

Of note, outness and LGBT community involvement reflect two related but distinct constructs. Being more open about one’s sexual orientation could lead to spending more time in the LGBT community, including contexts in which substance use is common and perceived as normative (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008), in turn leading to more substance use. However, research is needed to understand the associations between LGBT community involvement and changes in health over time. It will also be important for research to continue to examine other potential mechanisms underlying the associations between outness and negative health outcomes among bisexual individuals. In addition to experiencing discrimination, it can be difficult for bisexual individuals to find bisexual-specific communities and social spaces (Hayfield, Clarke, & Halliwell, 2014; Hequembourg & Brallier, 2009). As a result, it can be challenging for them to access non-stigmatizing environments and the resources that social communities provide (e.g., support; Cox, Vanden Berghe, Dewaele, & Vincke, 2010; Hayfield et al., 2014; Kertzner, Meyer, Frost, & Stirratt, 2009). Both stigma-related experiences and isolation from other bisexual individuals could explain why being more open about one’s sexual orientation is associated with increases in substance use and depression in this group.

Second, in contrast to our findings for bisexual individuals, we found some evidence that being more open about one’s sexual orientation had positive consequences for gay/lesbian individuals (i.e., decreases in illicit drug use). In recent years, attitudes toward same-sex relationships have improved (Pew Research Center, 2017), but attitudes toward bisexual individuals remain neutral at best and often negative (Dodge et al., 2016). Therefore, for gay/lesbian individuals, being more open about one’s sexual orientation may provide access to supportive allies while also reducing the stress associated with concealing one’s sexual orientation. In turn, gay/lesbian individuals who are more open about their sexual orientation may use social support rather than illicit drugs to cope with stress related to their sexual orientation. However, the positive consequences of outness for gay/lesbian individuals did not extend to any of the other health outcomes (i.e., those associations were non-significant). As such, there is a need for continued research to understand when and how being open about one’s sexual orientation contributes to positive health outcomes for gay/lesbian individuals.

Third, we did not find significant associations between outness and changes in cigarette use or anxiety for any subgroups of sexual minorities. Outness may not influence changes in cigarette use because of how common it is, especially among sexual minorities (King, Dube, & Tynan, 2012). Additionally, motivations for using cigarettes can vary across people and contexts. One study found that sexual minorities reported using cigarettes for various reasons (e.g., to forge connections with other sexual minorities, to cope with stress; Remafedi, 2007), and these reasons are relevant before and after coming out. Similarly, sexual minorities may experience anxiety before coming out (e.g., concerns about people suspecting their sexual orientation) and after coming out (e.g., concerns about rejection). As such, they may experience anxiety regardless of how open they are about their sexual orientation. Although outness was not significantly associated with changes in alcohol use for any subgroups of sexual minorities, the pattern was in the same direction as other health outcomes (i.e., there was a non-significant positive association for bisexual individuals and a non-significant negative association for gay/lesbian individuals). Therefore, it is possible that the negative association among bisexual individuals would have been significant in a larger sample. It is also possible that the age of our sample influenced our findings for alcohol use because many participants were not old enough to legally purchase alcohol for most of the study. Given that previous cross-sectional studies have found positive associations between outness and alcohol consumption among sexual minority adults (McKirnan & Peterson, 1989; Peacock, Andrinopoulos, & Hembling, 2015), outness may only influence alcohol use for those who have legal access to it.

Two previous studies found that the cross-sectional associations between outness and health were different for sexual minority men and women. Rothman et al. (2012) found that disclosure to a parent was associated with lower odds of depression and illicit drug use, but only for sexual minority women, and Pachankis et al. (2015) found that being out was associated with higher odds of depression, but only for sexual minority men. In our study, however, gender did not moderate the longitudinal associations between outness and changes in health. Neither of the previous studies accounted for sexual orientation or statistically tested gender as a moderator (i.e., they examined the associations separately for men and women). Furthermore, the samples in both of those studies were older than ours, and societal acceptance of same-sex relationships has increased over time (Pew Research Center, 2017). It is possible that there are cohort differences in the associations between outness and health. For example, as societal acceptance of sexual minorities continues to increase, there may be fewer people who experience negative consequences of being out. Still, given that attitudes toward bisexual individuals continue to be neutral at best and often negative (Dodge et al., 2016), it is important to account for sexual orientation in studies focused on the consequences of outness.

Finally, we also found several significant demographic differences in health at the between-person level (averaged across waves and controlling for covariates). Consistent with previous findings, bisexual participants reported more cigarette and alcohol use than gay/lesbian participants (for a review, see Feinstein & Dyar, 2017), male particpants reported more cigarette use than female participants, White participants reported more cigarette use (compared to Black participants) and more alcohol use (compared to Black and Latino/a particiapnts) (Miech, Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2016), and White participants reported higher anxiety than Black participants (Kessler et al., 2005). Although participants with less than a high school education reported more cigarette and illicit drug use than those with a high school education, those who had a high school education or who were older at baseline reported more alcohol use. Given that our participants were 18–22 at the first wave, these findings likely reflect easier access to alcohol for participants who were of legal drinking age and/or out of high school. Finally, participants with higher average outness over time reported higher cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use (averaged across waves and controlling for covariates), suggesting that the average associations between outness and substance use are only evident after accounting for individual differences. However, given our primary findings (that sexual orientation moderated the within-person associations between outness and changes in health), it is important to account for sexual orientation to understand the implications of being open about one’s sexual orientation.

Findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, given that our sample only included 34 bisexual women and 11 bisexual men, it will be critical to see if our findings are replicated in larger samples of bisexual individuals. Second, we excluded participants with sexual orientations other than LGB and those who reported different sexual orientations at different times. It remains unclear if findings generalize to those groups. Given that changes in sexual orientation are associated with increases in substance use and mental health problems (Everett, 2015; Ott et al., 2013), it will be important for future research to consider the role of outness. Third, while our sample was racially/ethnically diverse, it was not large enough to examine race/ethnicity as a moderator. Studies with larger samples could utilize an intersectional framework to examine how intersecting identities influences these associations. Fourth, on average, participants reported relatively low levels of depression and anxiety, and it will be important to see if our findings are replicated in samples with more severe symptoms. Fifth, we examined outness as a predictor of changes in health, but it is also possible that certain aspects of health could influence disclosure of one’s sexual orientation (e.g., depression and anxiety may inhibit disclosure). Future research should continue to examine the directionality of these associations. Finally, while our longitudinal design was a strength, we were only able to examine associations between outness and health 6–12 months later. Intensive repeated-measures designs (e.g., daily diaries) and longitudinal designs with more time points have the potential to improve our understanding of the immediate and long-term consequences of outness.

In sum, we found that being more open about one’s sexual orientation was associated with increases in substance use and depression for bisexual individuals but not for gay/lesbian individuals. These findings have important implications for healthcare providers who work with sexual minorities. It is important to recognize that being open about one’s sexual orientation can have negative consequences for bisexual individuals. While it has the potential to reduce stress associated with concealment and to facilitate connections to social support, it can also put bisexual individuals at risk for discrimination. As such, there is a critical need for interventions to reduce societal stigma toward bisexual individuals in order to improve the health of this population. Healthcare professionals can also help facilitate informed disclosure decisions that take into account an individual’s specific circumstances (e.g., safety, support, coping skills). For example, clinicians can help sexual minority clients think through the costs and benefits of disclosure in different contexts, strategies for disclosure, and ways to cope with negative reactions. Beyond that, there is a need to better understand why outness is associated with negative health outcomes for bisexual individuals. We offer possible explanations (e.g., exposure to discrimination, perceptions of substance use as normative), and the disclosure process model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) offers additional possibilities (e.g., reactions to disclosure, changes in behavior subsequent to disclosure). However, these remain empirical questions. As we develop a deeper understanding of how outness influences substance use and mental health across subgroups of sexual minorities, we will be able to develop more effective interventions to facilitate disclosure decisions and improve the health of sexual minorities.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH095413; PI: Mustanski), the National Institute on Child and Human Development (R01HD089170: PI: Whitton), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (PI: Mustanski), the William T. Grant Foundation Scholars Award (PI: Mustanski), and the David Bohnett Foundation (PI: Mustanski). Brian A. Feinstein’s time was also supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F32DA042708; PI: Feinstein). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

First, alcohol and marijuana use values were Winsorized at 3 SD above the mean, but outliers remained. Therefore, we Winsorized the top 5% of values instead of Winsorizing at 3 SD to reduce the influence of outliers (determined based on fewer cases with Cook’s distance values > 1).

Conflict of Interest: Brian A. Feinstein declares that he has no conflict of interest. Christina Dyar declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dennis H. Li declares that he has no conflict of interest. Sarah W. Whitton declares that she has no conflict of interest. Michael E. Newcomb declares that he has no conflict of interest. Brian Mustanski declares that he has no conflict of interest.

References

- Aranda F, Matthews AK, Hughes TL, Muramatsu N, Wilsnack SC, Johnson TP, & Riley BB (2015). Coming out in color: Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between level of sexual identity disclosure and depression among lesbians. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 247–257. doi: 10.1037/a0037644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco R, D’Alessio M, & Laghi F (2010). Binge drinking among gay, and lesbian youths: The role of internalized sexual stigma, self-disclosure, and individuals’ sense of connectedness to the gay community. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 896–899. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BD, & Heinz A (2006). Alcohol and aggression without consumption. Alcohol cues, aggressive thoughts, and hostile perception bias. Psychological Science, 17, 30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals KP, Peplau LA, & Gable SL (2009). Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 867–879. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, & Moradi B (2010). Perceived experiences of anti-bisexual prejudice: Instrument development and evaluation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 451–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, July 21). National Youth Tobacco Survey. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm

- Chaudoir SR, & Fisher JD (2010). The disclosure processes model: understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 236–256. doi: 10.1037/a0018193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N, Vanden Berghe W, Dewaele A, & Vincke J (2010). Acculturation strategies and mental health in gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1199–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9435-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, & Pilkington NW (1998). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (2001). BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. Bloomington, MN: National Computer Systems, Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Herbenick D, Friedman MR, Schick V, Fu T-C, Bostwick W, et al. (2016). Attitudes toward bisexual men and women among a nationally representative probability sample of adults in the United States. PLoS ONE, 11: e0164430 10.1371/journal.pone.0164430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett B (2015). Sexual orientation identity change and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56, 37–58. doi: 10.1177/0022146514568349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, & Dyar C (2017). Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Current Sexual Health Reports. doi: 10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Dyar C, & London B (2017). Are outness and community involvement risk or protective factors for alcohol and drug abuse among sexual minority women? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 1411–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0790-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, & Newcomb ME (2016). The role of substance use motives in the associations between minority stressors and substance use problems among young men who have sex with men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3, 357–366. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, & Dunlap S (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15, 350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK (2000). Ways of measuring drinking patterns and the difference they make: experience with graduated frequencies. Journal of Substance Abuse, 12, 33–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, & Fromme K (2008). Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: Results from a prospective study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayfield N, Clarke V, & Halliwell E (2014). Bisexual women’s understandings of social marginalisation: The heterosexuals don’t understand us but nor do the lesbians. Feminism & Psychology, 24, 352–372. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan K (1998). The nature and predictors of substance use among lesbians. Addictive Behaviors, 23, 517–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg AL, & Brallier SA (2009). An exploration of sexual minority stress across the lines of gender and sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 56, 273–298. doi: 10.1080/00918360902728517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2002). Heterosexuals attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, & Deluty RH (1998). Coming out for lesbian women: its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality, 35, 41–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster RP, Smith NG, Ouellet E, Sindi S, & Lupien SJ (2013). Sexual orientation and disclosure in relation to psychiatric symptoms, diurnal cortisol, and allostatic load. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75, 103–116. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182826881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Kulesza M, Balsam KF, Rhew IC, Blayney JA, Lehavot K, & Hughes TL (2014). Coping as a mediator of internalized homophobia and psychological distress among young adult sexual minority women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 225–233. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, & Stirratt MJ (2009). Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: the effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Dube SR, & Tynan MA (2012). Current tobacco use among adults in the United States: Findings from the National Adult Tobacco Survey. American Journal of Public Healh, 102, e93–e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, & Nazareth I (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Ramirez M, Dorey F, Ritt-Olson A, Iverson E, & Ford W (2007). Club drug use in Los Angeles among young men who have sex with men. Substance Use and Misuse, 42, 1723–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL, Greenberg JD, Pollack LM, & Dolezal C (2002). MDMA (‘ecstasy’) use, and its association with high risk behaviors, mental health, and other factors among gay/bisexual men in New York City. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 66, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, & Kull RM (2015). Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Mason TB, Winstead BA, Gaskins M, & Irons LB (2016). Pathways to hazardous drinking among racially and socioeconomically diverse lesbian women: Sexual minority stress, rumination, social isolation, and drinking to cope. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40, 564–581. doi: 10.1177/0361684316662603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke O, Marsh HW, Robitzsch A, Trautwein U, Asparouhov T, & Muthen B (2008). The multilevel latent covariate model: A new, more reliable approach to group-level effects in contextual studies. Psychological Methods, 13, 203–229. doi: 10.1037/a0012869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Ludtke O, Robitzsch A, Trautwein U, Asparouhov T, Muthen B, & Nagengast B (2009). Doubly-latent models of school contextual effects: Integrating multilevel and structural equation approaches to control measurement and sampling error. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 44, 764–802. doi: 10.1080/00273170903333665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, . . . Brent DA (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 49, 115–123. doi:DOI 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, . . . Morse JQ (2008). Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction, 103, 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, & Peterson PL (1989). Psychosocial and cultural factors in alcohol and drug abuse: An analysis of a homosexual community. Addictive Behaviors, 14, 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels MS, Parent MC, & Torrey CL (2016). A minority stress model for suicidal ideation in gay men. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 46, 23–34. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, & Rochlen AB (1999). Measuring attitudes regarding bisexuality in lesbian, gay male, and heterosexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, & Rothblum ED (2001). A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ott MQ, Wypij D, Corliss HL, Rosario M, Reisner SL, Gordon AR, & Austin SB (2013). Repeated changes in reported sexual orientation identity linked to substance use behaviors in youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, & Mays VM (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 890–901. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA, Hughes TL, & Kinnison KE (2007). The relationship between early drinking contexts of women “coming out” as lesbian and current alcohol use. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3, 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock E, Andrinopoulos K, & Hembling J (2015). Binge drinking among men who have sex with men and transgender women in San Salvador: correlates and sexual health implications. Journal of Urban Health, 92, 701–716. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2017, June). Changing attitudes on gay marriage. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/

- Ploderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek R, & Kralovec K (2014). Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1559–1570. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, & Zhang Z (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G (2007). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths: Who smokes, and why? Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 9, S65–71. doi: 10.1080/14622200601083491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]