Abstract

The present study elucidated whether roots of temperate forest trees can take up organic phosphorus in the form of ATP. Detached non-mycorrhizal roots of beech (Fagus sylvatica) and gray poplar (Populus x canescens) were exposed under controlled conditions to 33P-ATP and/or 13C/15N labeled ATP in the presence and absence of the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42-. Accumulation of the respective label in the roots was used to calculate 33P, 13C and 15N uptake rates in ATP equivalents for comparison reason. The present data shown that a significant part of ATP was cleaved outside the roots before phosphate (Pi) was taken up. Furthermore, nucleotide uptake seems more reasonable after cleavage of at least one Pi unit as ADP, AMP and/or as the nucleoside adenosine. Similar results were obtained when still attached mycorrhizal roots of adult beech trees and their natural regeneration of two forest stands were exposed to ATP in the presence or absence of MoO42-. Cleavage of Pi from ATP by enzymes commonly present in the rhizosphere, such as extracellular acid phosphatases, ecto-apyrase and/or nucleotidases, prior ADP/AMP/adenosine uptake is highly probable but depended on the soil type and the pH of the soil solution. Although uptake of ATP/ADP/AMP cannot be excluded, uptake of the nucleoside adenosine without breakdown into its constituents ribose and adenine is highly evident. Based on the 33P, 13C, and 15N uptake rates calculated as equivalents of ATP the ‘pro and contra’ for the uptake of nucleotides and nucleosides is discussed.

Short Summary

Roots take up phosphorus from ATP as Pi after cleavage but might also take up ADP and/or AMP by yet unknown nucleotide transporter(s) because at least the nucleoside adenosine as N source is taken up without cleavage into its constituents ribose and adenine.

Keywords: adenosine uptake, ADP/AMP uptake, ATP uptake, excised non-mycorrhizal roots, Fagus sylvatica, phosphatase inhibition, Populus x canescens, uptake competition

Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is one of the six macronutrients in all living organism essential for growth and development due to its function in DNA and RNA for inheritance, in free nucleotides for energy transfer, in phospholipids as membrane components as well as in sugar phosphates within carbon metabolism including signaling and regulation processes. Different to nitrogen (N) and sulfur (S), which are acquired by plant roots from the soil via active uptake mechanisms (e.g., Gigolashvili and Kopriva, 2014; Rennenberg and Dannenmann, 2015; Castro-Rodríguez et al., 2017) and from the atmosphere via diffusion through the stomata of leaves (e.g., Gessler et al., 2000, 2002; Herschbach, 2003), P is exclusively available in the soil. With soil development (pedogenesis), the already low availability of P (Bieleski, 1973) further decreases due to long-term weathering, erosion, and leaching (Turner and Condron, 2013). P input into the soil by P deposition is extremely low (Peñuelas et al., 2013) and a chemical shift of plant available to unavailable organic bound phosphate (Porg) (Walker and Syers, 1976; Callaway and Nadkarni, 1991; Chadwick et al., 1999; Vitousek et al., 2010; Vincent et al., 2013) further diminishes the plant available P in the soil. As a consequence, during plant evolution several morphological, physiological, and molecular strategies have been developed to overcome this limitation (Vance et al., 2003; Lambers et al., 2008, 2015a,b). P acquisition can be improved by the formation of cluster roots in Proteaceae at P limitation (Lambers et al., 2015a). Mycorrhizal association, evolved by about 90% of all land plants, largely enhances the root surface as well as the accessibility to small diameter soil pores; thereby mycorrhizal hyphae are the most important sites of P acquisition of most plant species (Jansa et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2015). Increased organic acid and acid phosphatase exudation improves Pi solubilization of Al- and Fe-bound P and the cleavage of organic-bound P, respectively (Tran et al., 2010; Chen and Liao, 2016).

A major part of soil phosphate (Pi) is adsorbed to Fe and Al oxyhydroxides and, hence, is not available for plant uptake (Prietzel et al., 2016), but is also present as phosphate (di)esters such as nucleic acids, sugar phosphate and phospholipids as Porg (Plassard and Dell, 2010). Exudation of organic acids by the roots (Plaxton and Tran, 2011; Tian and Liao, 2015) supports phosphate (Pi) solubilization from chelated aluminum- and iron-P (Hinsinger, 2001; Jones and Oburger, 2011; Marschner et al., 2011; Prietzel et al., 2016). Extracellular phosphatases produced and exuded by microbes, fungi and plant roots mediate Pi cleavage from Porg and make Pi from Porg available for the uptake by roots (Hinsinger et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015; Tian and Liao, 2015). The release of acid phosphatase into the rhizosphere by microbes and plants depends on the soil-P level, with higher activity at P-poor than at P-rich forest soils (Hofmann et al., 2016). Furthermore, gross and net P mineralization was found to be negligible in soils developed on a P-rich basalt site, but biological and biochemical processes dominate P mineralization in a P-poor sandy soil (Bünemann et al., 2016). Pi uptake by plant roots is furthermore adapted to plant available Pi concentrations in the soil solution at the level of Pi transporter expression (Kavka and Polle, 2016). All these strategies and processes can influence and affect the acquisition of Pi, the only form of P described to be taken up by plant roots (Chiou and Lin, 2011).

The amount of Porg in soils depends on soil type and age (Jones and Oburger, 2011). For example, about 95% of mobile P in a rendzic forest soil was found to be Porg (Kaiser et al., 2003). In this context, it is remarkable that mobilization of glucose-6-phosphate from ferrihydrite by ligand-promoted dissolution via organic acids, such as oxalate and ascorbate, is higher than mobilization of Pi (Goebel et al., 2017). Hence, Porg may be highly available in the rhizosphere after organic acid exudation. Furthermore, P acquisition by plants is mainly achieved from the organic layer by ectomycorrhizal fungi (Zavišić et al., 2016). In the organic soil layer plant available Pi was 5 to 36 times higher than in the mineral layer. However, in the organic soil layer most of the total P was found to be attributed to Porg fixed in plant litter and living organism of the rhizosphere and only 10–24% was present as Pi (Zavišić et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2017). Hence, Porg is an important P source that gets available during degradation of root and leaf litter as well as dead microbes and soil organic matter (SOM) (Shen et al., 2011).

Altogether, this summary indicates the importance of P acquisition from Porg by plant roots. However, the preferential Porg compound(s) used in Pi release (e.g., nucleotides versus sugar phosphates) by acid and alkaline phosphatases, the significance of Pi release versus direct Porg uptake, and the interaction/competition between Pi and Porg for Pi uptake by the roots have not been established. Such interactions were found for the inorganic and organic N uptake by the roots of woody plants (e.g., Stoelken et al., 2010). Determination of ATP in the soil is frequently used to quantify microbial biomass (Blagodatskaya and Kuzyakov, 2013) and, consequently, ATP seems to be available for P acquisition by the roots. In addition, extracellular ATP mostly correlated with regions of active growth and cell expansion and has been discussed as a signal in growth control (Kim et al., 2006; Tanaka et al., 2010, 2014; Yang et al., 2015). Hence, mobility of ATP across the root plasma membrane is highly probable. Consequently, roots might take up ATP and other Porg compounds such as sugar-Ps. Although the significance of Porg as Pi source for P nutrition of plants is well known (e.g., Thomas et al., 1999; Liang et al., 2010), direct uptake of Porg compounds has not been established.

The aim of the present study was to elucidate, if roots of temperate forest trees can take up Porg in the form of ATP. We hypothesized that ATP and/or one of its degradation products ADP, AMP, as important Porg compounds of soil, root and leaf litter, and of microbial detritus in the rhizosphere, can be taken up by tree roots as intact molecule. We further hypothesized that ATP and Pi uptake compete with each other. These hypotheses were tested under controlled conditions with detached roots of two temperate forest tree species colonizing different ecological niches; i.e., beech (Fagus sylvatica) the most important climax tree species of Central European temperate forests and poplar (Populus x canescens) a continuously, fast growing tree species of floodplains (Stimm and Weisgerber, 2008).

Materials and Methods

Plant Material for Experiments Under Controlled Conditions

Poplar cuttings (Populus tremula × Populus alba, synonym Populus x canescens) of the INRA clone 717 1B4) were micropropagated (Strohm et al., 1995), transferred into sand after 4–6 weeks of growth (Herschbach et al., 2010; Scheerer et al., 2010; Honsel et al., 2012) and cultivated in a greenhouse under long-day conditions for further 14–18 weeks. Poplar plants were fertilized with 200 mL modified ¼ Hoagland solution per week (Herschbach et al., 2010; Honsel et al., 2012). The one fourth modified Hoagland solution (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950) contained: 0.6 mM KNO3, 1.3 mM Ca(NO3)2 × 4 H2O, 0.3 mM MgSO4 × 7 H2O, 1.5 mM MgCl2 × 6 H2O, 0.25 mM KH2PO4, 2.3 μM MnCl2 × 4 H2O, 2 μM H3BO3, 0.08 μM CuCl2 × 4 H2O, 0.2 μM ZnCl2, 0.2 μM Na2MoO4 × 2 H2O, 0.04 μM CoCl2 × 6 H2O, 22.5 μM Na2-EDTA, 22.5 μM FeCl2 and was adjusted to pH 5.5. If necessary poplar plants were provided with distilled water.

Beech seedlings were cultivated from beech nuts collected in 2011 from the Conventwald forest stand (Forstbaumschule Stingl, Albstadt-Burgfelden, Germany) [7.960 East; 48°02′ North (Google earth); von Wilpert et al., 1996; Netzer et al., 2017] and stored for stratification at 8°C. Beech nuts were germinated as described in detail by Kreuzwieser et al. (1996). Briefly: nuts were soaked in tap water for 4 weeks at 4°C. After germination, seeds were peeled, surface sterilized and kept for 2–4 weeks at axenic conditions. Thereafter, seedlings were transferred into a sand (particle size 1–2 mm)/vermiculite (1:1) mixture in pots of 1 L size. Beech seedlings were fertilized two times a week with 100 mL of a nutrient solution adapted to the soil water of the Conventwald forest (Netzer et al., 2017). This solution contained 290 μM NH4Cl, 350 μM KNO3, 160 μM CaCl2, 170 μM MgSO4, 20 μM KH2PO4, 0.23 μM MnCl2, 0.02 μM ZnCl2, 0.2 μM H3BO3, 0.008 μM CuCl2, 0.02 μM Na2MoO4, 0.004 μM CoCl2, and 2.25 μM FeCl2 and was adjusted to pH 5.5. Beech seedlings were grown for more than 3 months in a greenhouse under long-day conditions. In addition, 2-year old beech seedlings from a commercial supplier (Eberts OHG, Tangstedt/Pbg., Germany) were used.

Measurements of 33P Uptake Applied as 33P-PO43- and 33P-ATP

For uptake measurement of 33P-Pi (Hartmann Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany), roots were excised from P. x canescens plants, which were 14 to 18-weeks old and/or 0.7–1 m in height (Herschbach et al., 2010; Honsel et al., 2012). Roots of beech seedlings were excised after removing vermiculite and peat particles. Excised roots of both species were placed into an incubation chamber (Herschbach and Rennenberg, 1991), which consisted of three compartments, i.e., an application compartment (compartment A, 50 mL), a buffer compartment (compartment B, 20 mL) and a compartment for xylem sap exudation (compartment C, 30 mL). In case of poplar, for pre-incubation the compartments were filled with ¼ Hoagland solution (compartment B and C without Pi) supplemented with 2 mM MES buffer and adjusted to pH 5.0. In case of 33P-ATP treatments, the respective (pre-) incubation solutions in compartment A did not contain phosphate and molybdate but ATP. Beech roots were pre-incubated in the beech fertilization solution supplemented with 2 mM MES buffer adjusted to pH 5.0. The pH dependency of Pi uptake was analyzed with excised poplar roots over a range of pH 3.5 to pH 7 (Hinsinger, 2001) and revealed highest values at pH 4.5 to pH 5.5, but no marked pH optimum (Supplementary Figure S1). Hence, all uptake experiments were performed at pH 5.0.

Incubation chambers were placed on aluminum plates cooled down to 15°C to simulate soil temperature. Excised roots of beech and poplar were pre-incubated for 2 h (Herschbach et al., 2010). After pre-incubation the solution of the application compartment (compartment A) was replaced by the respective solution supplemented with radiolabeled 0.25 mM 33P-phosphate (4.1∗107 to 5.3∗107 Bq mmol-1 Pi) or with 0.169 mM 33P-ATP (5.3∗107 to 1.2∗107 Bq mmol-1 ATP). 33P-ATP was applied either as γ33P-ATP or as α33P-ATP (Figure 1). Uptake of 33P from 33P-Pi and 33P-ATP was terminated after 4 h [during this time, linear uptake can be assumed (Herschbach and Rennenberg, 1991)] by washing the roots three-times with the respective unlabeled solution to remove adherent labeled compounds. Root sections of the incubation compartment were separated from the root part located in compartment B and C. 33P was determined by liquid scintillation counting after sample bleaching as previously described (Herschbach et al., 2010; Scheerer et al., 2010). Calculation of uptake rates as well as of xylem loading rates was performed according to Herschbach and Rennenberg (1991).

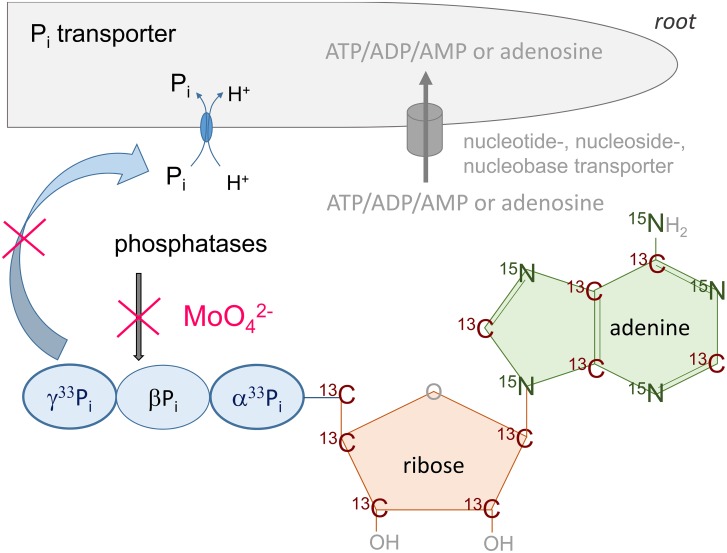

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the experimental designs with differently labeled ATP molecules. During the experiments, three differently labeled ATP molecules were applied: α33P-ATP; γ33P-ATP, 13C/15N labeled ATP (ATP 13C10H1615N5O13P3 xNa) with the 13C label in the ribose and base. The base adenine/cytidine was additionally labeled by 15N. Molybdate was applied as a common acid phosphatase inhibitor to prevent cleavage of the γPi and βPi unit of the ATP molecule (Gallagher and Leonard, 1982; Cabello-Díaz et al., 2012). Uptake of nucleotides such as ATP, ADP, AMP and/or adenosine via yet unknown transporters is indicated. Unlabelled phosphate (Pi) in the solution competed with the Pi cleaved from ATP by extracellular phosphatases, ecto-apyrases, or nucleotidases (Wu et al., 2007; Riewe et al., 2008; Tanaka et al., 2014) for the uptake via Pi uptake transporters.

Experiments of 13C and 15N Uptake Applied as Double-Labeled ATP and CTP Under Controlled Conditions

For uptake experiments with stable isotope labeled ATP/CTP (Figure 1), excised roots of poplar and beech were placed into an incubation chamber (Herschbach and Rennenberg, 1991) consisting of an application compartment (compartment A; 85 mL), a buffer compartment (compartment B) and a xylem sap exudation compartment (compartment C) (each 10 mL). Double-labeled ATP (ATP-13C1015N5, 98 atom%, Sigma Aldrich) (Figure 1) and CTP (CTP-13C915N3, 98 atom%, Sigma Aldrich) were diluted to 10 atom% or 14 atom% and were adjusted to the final concentration of 0.169 mM ATP and CTP. The soil microbial ATP concentration of active and dead microorganism, which are constituents of the rhizosphere, ranged from <1.2 μg g-1 soil (<5–10 μmol g-1 dormant microbial biomass) to >2 μg g-1 soil (>12–15 μmol g-1 active microbial biomass) (Blagodatskaya and Kuzyakov, 2013). The ATP concentration applied in the incubation solution corresponds to approximately 90 μg ATP mL-1 or to 0.169 mmol mL-1, which was in the range of several experiments performed to test physiological responses to extracellular ATP (Roux and Steinebrunner, 2007). Roots were pre-incubated with the respective solutions without phosphate and molybdate. After 2 h of pre-incubation the incubation solution of compartment A was replaced by the respective solution that contained 0.169 mM of 13C/15N labeled ATP or CTP (10 or 14 atom%). To simulate soil temperature, incubation chambers were placed on aluminum plates cooled down to 15°C for 4 h of incubation. Uptake of ATP or CTP was terminated by washing roots 3-times with the respective unlabeled solution. Root sections in the incubation compartment (compartment A) were separated from the root sections located in compartment B and C. Oven dried homogenized root samples were subjected to IRMS analysis for the determination of 13C and 15N accumulation.

Experiments of 13C and 15N Uptake Applied as Double-Labeled ATP in the Field

To test if 13C and 15N uptake rates calculated as ATP equivalents in experiments under controlled conditions were similar to 13C and 15N uptake rates equivalent to ATP in the field, ATP uptake experiments were performed in September 2017 at two field sites, namely the acidic Conventwald (Con) and calcareous Tuttlingen (Tut) forest stands. The soils of these forests differ in their properties (silicate versus limestone bedrock) (Prietzel et al., 2016) with the Tuttlingen soil containing eightfold lower plant available Pi (for detailed soil descriptions see Prietzel et al., 2016; Netzer et al., 2017). At both field sites, fine roots of six adult beech trees and of six beech saplings were carefully excavated out of the soil. Adherent soil particles from the roots were removed with distilled water and cleaned roots were dried using paper towels. Roots still attached to adult beech trees or to their offspring were incubated in an artificial soil solution at pH 5.0 that contained 29 μM NH4Cl, 35 μM KNO3, 16 μM CaCl2, 17 μM MgCl2 0.3 μM MnCl2, 22 μM NaCl, and 0.169 mM ATP. Double-labeled ATP was diluted to 10 atom% (ATP-13C1015N5, 98 atom%, Sigma Aldrich). Fine roots were cut from the trees after 4 h of incubation, rinsed with distilled water to remove adherent ATP-13C1015N5, dried in an oven (72 h, 50°C) for at least 2 days and homogenized using mortar and pestle.

Analysis of C and N Contents and of the 13C and 15N Abundance

13C and 15N incorporation into root sections after ATP-13C1015N5 and CTP-13C915N3 exposure were determined in over dried powdered root samples of 0.1–2.0 mg aliquots filled into tin capsules (Hu et al., 2017). Total carbon and nitrogen contents as well as the 15N and 13C abundances were determined using an elemental analyzer (NA 2500CE Instruments, Milan, Italy) coupled via a Conflo II interface to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Delta Plus, Thermo Finnigan MAT GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Alternatively, samples were analyzed with an elemental analyzer NA 1108, Fisons-Instruments, Rodano, Milan, Italy and a mass spectrometer (Delta C, Finnigan MAT, Bremen, Germany) coupled by a ConFlo III interface (Thermo Electron Corporation, Bremen, Germany) (Zieger et al., 2017). A working standard (glutamic acid) was calibrated against the primary standards of the United States Geological Survey 40 (USGS 40; glutamic acid δ13 CPDB = -26.39‰) and USGS 41 (glutamic acid δ13 CPDB = 37.63‰) for δ13C, and USGS 40 (glutamic acid δ15 Nair = -4.5‰) and USGS 41 (glutamic acid δ15 Nair = 47.600‰) for δ15 N. Standards were analyzed after every tenth sample to account for potential instrument drift over time as described by Dannenmann et al. (2009) and Simon et al. (2011). Accumulation of δ15N and δ13C was used to calculate N and C uptake rates in equivalents of ATP and CTP (Rennenberg et al., 1996; Gessler et al., 1998).

Data Analyses

For comparison, uptake of 33P as well as of 13C and 15N from differently labeled ATP/CTP was calculated from 33P, 15N and 13C incorporation as equivalents of ATP. This standardized calculation allows direct comparison between treatments and uncovers differences between the differently labeled ATP (Figure 1). Statistical analyses were performed with Origin®9.1 (OriginLab Corporation1). Normal distribution of the data was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; all data showed normal distribution at least by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. One Way ANOVA was applied followed by the Bonferroni and Tukey test with p < 0.5. Data are presented as single values (left to the box plots) and as box-plots showing the median (black line), the mean (open square), and the 25 and 75 percentile. Minimum and maximum values are given as error bars, whereas outliers (1%) are presented as stars.

Results

Competition of Pi Uptake by ATP

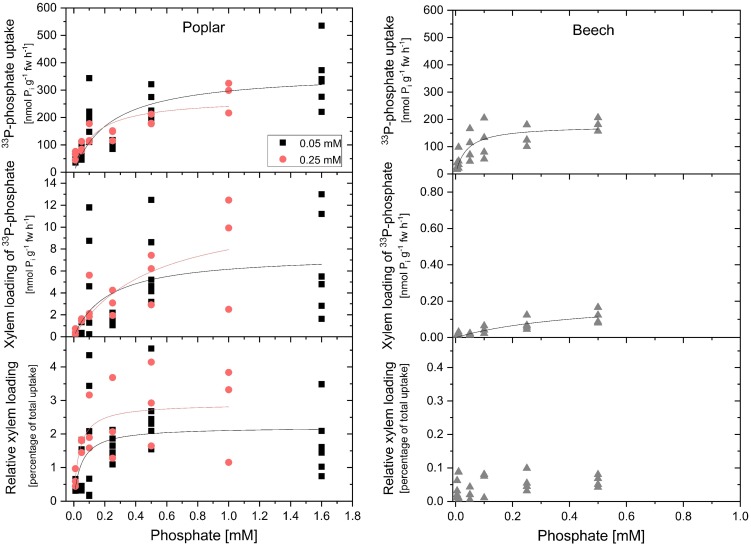

Pi uptake rates of excised roots calculated from 33P-Pi application (compare Figure 1) for both, poplar and beech, followed Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Figure 2). Growth Pi concentration only slightly affected Km and vmax values of Pi uptake of excised poplar roots. At 0.25 mM growth Pi, a marginally higher Pi affinity was indicated by a lower Km-value (126 ± 49 μM) compared to growth at 0.05 mM Pi (Km value of 238 ± 94 μM). The maximum Pi uptake rate was lower during growth at 0.25 mM Pi (271 ± 31 nmol g-1 fw h-1) compared to the growth at 0.05 mM Pi (367 ± 50 nmol g-1 fw h-1). Excised roots from beech seedlings cultivated with 0.02 mM Pi showed remarkably lower Km (39 ± 18 μM) and vmax values (178 ± 21 nmol g-1 fw h-1). The tripartite incubation chamber allowed calculation of the Pi that has been loaded into the xylem (Herschbach and Rennenberg, 1991). Growth Pi did not affect this parameter that accounts for up to 4% of total Pi taken up by excised roots for poplar (Figure 2). In contrast, the Pi loaded into the xylem of excised beech roots was extremely low and reached approximately 0.1% of total Pi taken up that was close to the limit of detection (Figure 2). Maximum rate of Pi loaded into the xylem was 13 nmol g-1 fw h-1 for poplar but only 0.17 nmol g-1 fw h-1 for beech.

FIGURE 2.

Concentration dependency of phosphate uptake, xylem loading of phosphate and the relative proportion of phosphate loaded into the xylem of excised poplar and beech roots. Concentration dependency of phosphate (Pi) uptake (upper graphs), xylem loading of phosphate (middle graphs) and the relative proportion of phosphate loaded into the xylem (bottom graphs) was performed with excised poplar (left column) and beech (right column) roots. Poplar plants were grown either with 0.05 mM Pi (black squares) or with 0.25 mM Pi (red dots). Beech seedlings were cultivated with 0.02 mM Pi. Data presented are values from individual incubations with four to six excised roots. Michaelis–Menten fits were calculated using the data analysis and graphic software Origin®9.1. The black and red curves show Michaelis–Menten fits for the respective plant sets; black: growth Pi = 0.05 mM; red: growth Pi = 0.25 mM for poplar, and gray for beech. After 2 h of pre-incubation the 4 h of incubation were started by replacing the solution of the incubation compartment with the respective incubation solution containing the Pi concentration indicated; for poplar from 0.01 mM up to 1.6 mM Pi and for beech from 5 μM up to 0.5 mM Pi. Specific activity of 33P-Pi ranged from ∼2.0∗108 Bq mmol-1 (application of 0.05 mM Pi) up to ∼5.7∗106 Bq mmol-1 (treatment of 1.6 mM Pi) for poplar and ranged from ∼1.9∗109 Bq mmol-1 (application of 0.005 mM Pi) up to ∼1.9∗107 Bq mmol-1 (treatment of 0.5 mM Pi) for excised beech roots.

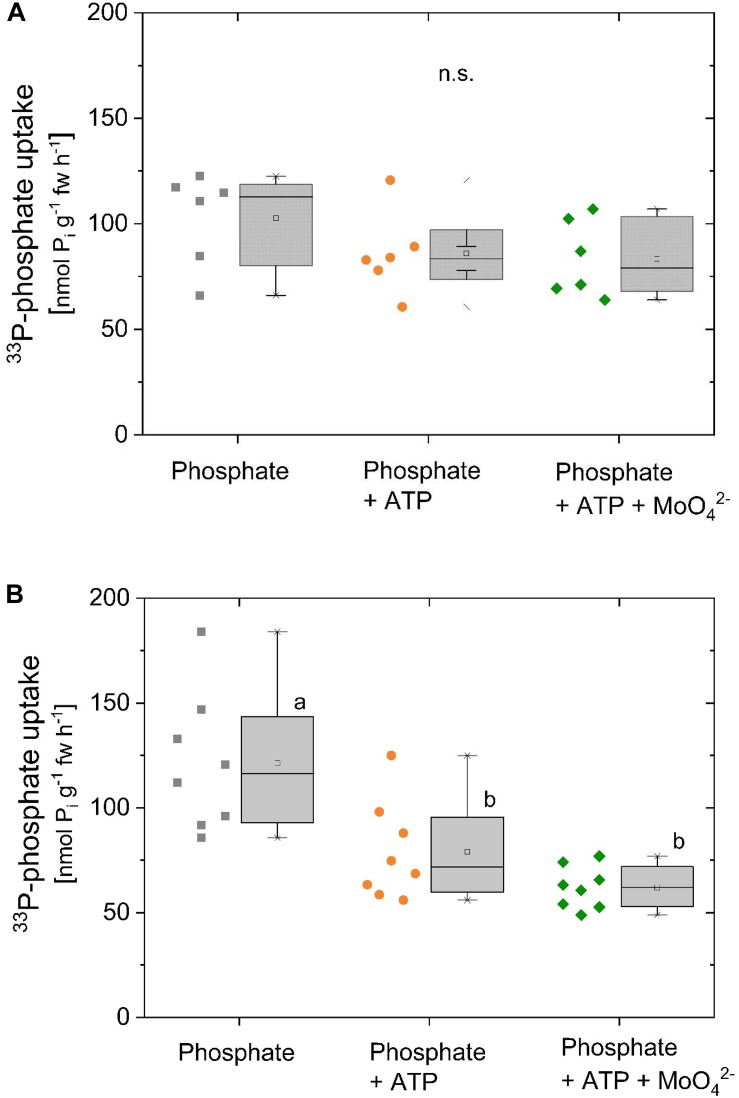

33P-Pi uptake by excised poplar roots remained unaffected by the presence of ATP (Figure 3A). Application of MoO42-, a common inhibitor of acid phosphatases, except for intracellular phosphatases, was used to prevent Pi cleavage from ATP (Gallagher and Leonard, 1982; Bozzo et al., 2002; Cabello-Díaz et al., 2012). By applying molybdate, dilution of the specific activity of 33P-Pi by unlabelled Pi cleaved from ATP was supposed to be prevented. Under these conditions, 33P-Pi uptake of excised poplar roots was also not affected if ATP was present (Figure 3A). Xylem loading of phosphate in this experiment was below 2 nmol g-1 fw h-1 (data not shown). In contrast, 33P-Pi uptake of excised beech roots significantly declined in the presence of ATP (Figure 3B). However, addition of MoO42- to prevent Pi cleavage from ATP did not recover 33P-Pi uptake by excised beech roots. Apparently, the decline in 33P-Pi uptake by excised beech roots in the presence of ATP was not a dilution effect by ATP cleavage through acid phosphatases but could be due to the cleavage through ecto-apyrases. Xylem loading of 33P-Pi was below 0.2 nmol g-1 fw h-1 (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Competition of Pi uptake by ATP of excised poplar and beech roots. Competition of Pi uptake by ATP was investigated with excised poplar (A, n = 6) and excised beech (B, n = 8) roots. (A) Roots were excised from poplar plants grown with 0.25 mM Pi (experiments were performed in October). During the incubation 0.5 mM 33P-Pi (∼2.8∗107 Bq mmol-1) was applied either solely, together with 0.338 mM ATP or together with ATP plus the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- (0.5 mM). (B) Roots were excised from beech seedlings cultivated with 0.02 mM Pi (experiments were performed in December/January). During incubation 0.25 mM 33P-Pi (∼4.5∗107 Bq mmol-1) was applied either solely, together with 0.25 mM ATP or together with ATP plus the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- (0.5 mM). Data are presented as box plots with individual data left to the box plots. Different small letters indicate significant differences between treatments at p < 0.05 analyzed by One Way ANOVA followed by the Post hoc tests Bonferroni and Tukey.

33P Uptake From γ33P-ATP

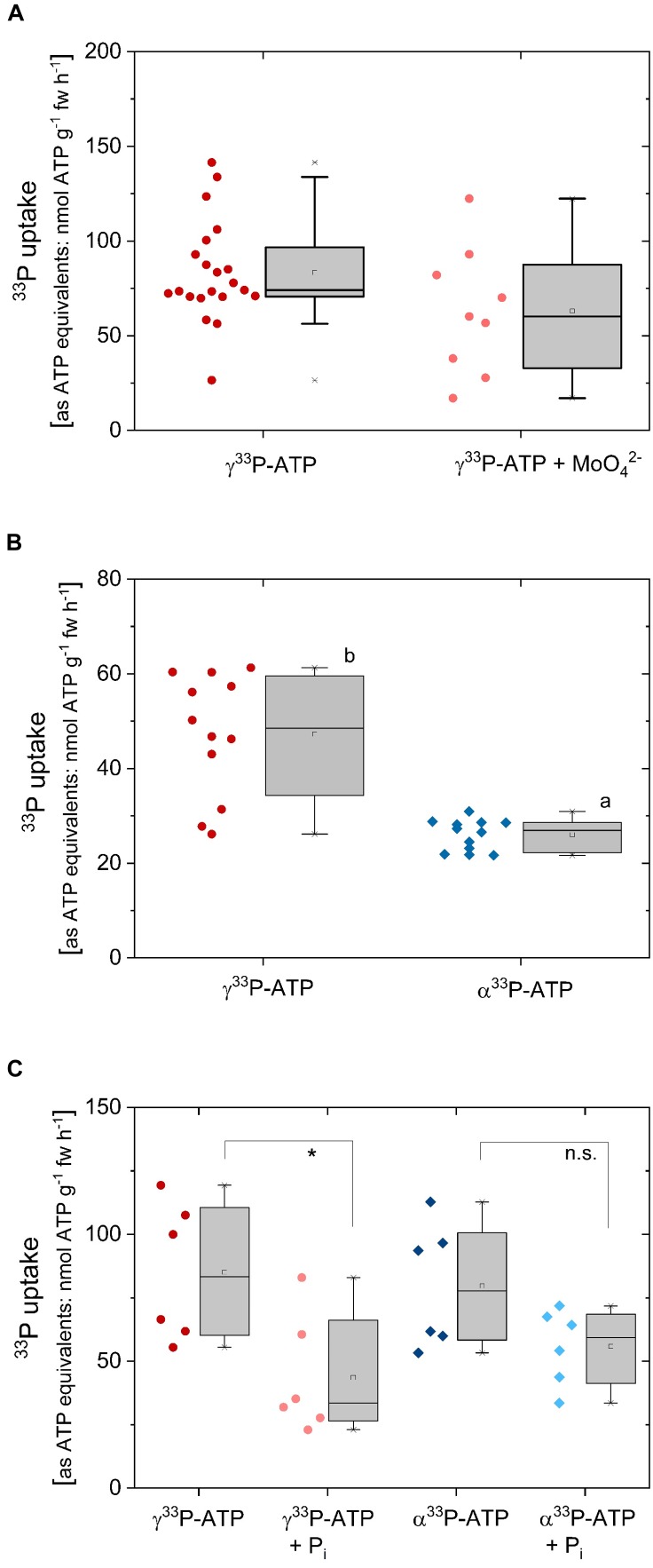

Uptake of 33P from γ33P-ATP by excised poplar roots was determined as 33P incorporation and calculated as ATP equivalents (approximately 83 ± 27 nmol ATP g-1 fw h-1) (Figure 4A). 33P from γ33P-ATP can be taken up as ATP, but also as 33P-Pi after cleavage by phosphatases. Application of the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- slightly, but not significantly, diminished 33P incorporation that amounted 63 ± 33 nmol g-1 fw h-1 in the presence of MoO42- (Figure 4A). Xylem loading of 33P from the applied γ33P-ATP was significantly lower in the presence of MoO42- and amounted 0.3 ± 0.2 nmol g-1 fw h-1 compared to 0.6 ± 0.3 nmol g-1 fw h-1 in the absence of MoO42-.

FIGURE 4.

33P uptake rates as ATP equivalents of excised poplar roots, its competition by Pi and the effect of acid phosphatase inhibition. Roots were excised from poplar plants cultivated with 0.25 mM Pi. (A) Excised poplar roots were incubated with γ33P-ATP (0.169 mM; ∼6.0∗107 Bq mmol-1) either solely of together with the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- (0.5 mM). The experiments (n = 21 biological replicates treated without molybdate and 9 biological replicates treated with molybdate) were performed during February/March. (B) Excised poplar roots were incubated with γ33P-ATP or α33P-ATP (0.169 mM; 4.2∗107 to 6.4∗107 Bq mmol-1) either solely (B, n = 12; experiments were carried out end of March/at the beginning of April) or in combination with 0.25 mM Pi for competition (C, n = 6, experiments were carried out in May). In order to be able to compare 13C and 15N uptake rates, both were calculated as ATP equivalents, i.e., 5 15N correspond to one ATP while 10 13C are equivalent to one ATP. Data are presented as box plots with individual data left to the box plots. Different small letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 between treatments analyzed by One Way ANOVA followed by the Post hoc tests Bonferroni and Tukey. The asterisk in C indicates significant differences between the treatments γ33P-ATP and γ33P-ATP plus Pi (p < 0.05). Variation of 33P uptake rates as ATP equivalents between different experiments presented here and in Figure 6A may be due to seasonal variations as observed for Pi (Netzer et al., 2018).

Another approach to test the importance of Pi cleavage for the uptake of 33P from 33P labeled ATP was tested by comparing 33P uptake from γ33P-ATP and α33P-ATP. Assuming that 33P prior its uptake must be cleaved from ATP by phosphatases, 33P uptake should be lower when the α-P instead of the end standing γ-P was labeled as 33P. Indeed, 33P uptake was significantly lower when the α-P instead of the γ33P in the ATP was labeled (Figure 4B). Hence, it can be assumed that poplar roots take up part of the 33P as Pi after cleavage from γ33P-ATP by phosphatases and/or ecto-apyrases. To test this assumption, Pi was added to the incubation solutions together with γ33P-ATP and α33P-ATP. It was expected that the non-labeled Pi diluted the 33Pi signal in excised poplar roots to a higher extent when ATP was applied as γ33P-ATP compared to the application of α33P-ATP. As expected, Pi significantly diminished the 33P incorporation into excised roots from γ33P-ATP, but not from α33P-ATP (Figure 4C). The xylem loading rate of 33P-Pi was below 1 nmol g-1 fw h-1 and was not affected by Pi supplementation (data not shown).

13C and 15N Uptake From Labeled ATP by Excised Poplar Roots

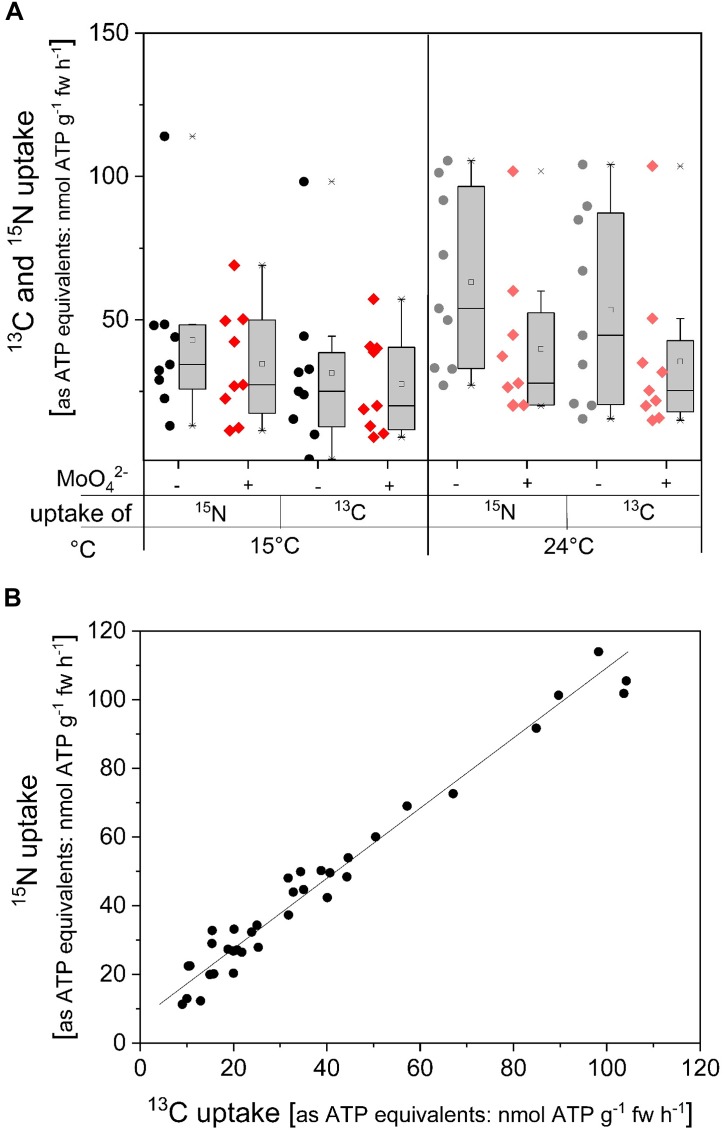

13C/15N labeled ATP was applied as another approach to investigate ATP uptake. In the 13C/15N labeled ATP, ribose was labeled only with 13C whereas adenine was labeled by both, 13C and 15N. In order to compare 13C and 15N uptake rates both were calculated as ATP equivalents, i.e., five 15N correspond for one ATP, while ten 13C are equivalent to one ATP. Incubation with doubled labeled ATP at 15°C, applied to simulate soil temperature in forest stands, resulted in similar 13C and 15N uptake rates equivalent to ATP and were not affected by the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- (Figure 5). Xylem loading of 15C and 15N in this approach was below the detection limit. At higher incubation temperature 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents were slightly increased, however, this increase was not statistically significant. Inhibition of acid phosphatases by MoO42- slightly diminished 13C and 15N uptake rates calculated as ATP equivalents, but again this decline was not statistically significant. These results indicate that at least one Pi unit needs to be cleaved before roots can take up resulting ADP, AMP and/or adenosine. The strong correlation between 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents suggest that ribose was taken up together with the adenine base (Table 1 and Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

13C and 15N uptake rates in ATP equivalents of excised poplar roots in dependency on temperature and on acid phosphatase inhibition by MoO42-. Roots were excised from poplar plants cultivated with 0.25 mM Pi. (A) Excised poplar roots were incubated with 0.169 mM ATP (14 atom% ATP-13C1015N5) at 15°C (n = 9) or at 24°C (n = 9) either solely or together with the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- (0.5 mM). Data from experiments performed in June/July are presented as box plots with individual data left to the box plots. In order to be able to compare 13C and 15N uptake rates, both were calculated as ATP equivalents, i.e., five 15N correspond to 1 ATP while 10 13C are equivalent to one ATP. Significant differences were analyzed with the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test because normal distribution of the data was not given. Nevertheless, significant differences were not found at p < 0.05. (B) Correlation between 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents of all individual incubation chambers, i.e., all samples and treatments. Correlation characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation analyses between 13C uptake (x-axis) and 15N or 33P uptake rates calculated as ATP/CTP equivalents.

| y-axis | Slope | y-intercept | P | r2 | Figure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As ATP/CTP equivalents | In the presence of: | |||||

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-ATP plus α33P-ATP | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 12 ± 7 | 0.969 | 0.938 | 6C |

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-ATP plus γ33P-ATP | 0.95 ± 0.05 | 19 ± 5 | 0.989 | 0.978 | 6C |

| 33P uptake | 13C/15N-ATP plus α33P-ATP | 1.64 ± 0.37 | 78 ± 31 | 0.817 | 0.668 | 6C |

| 33P uptake | 13C/15N-ATP plus γ33P-ATP | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 255 ± 95 | 0.514 | 0.264 | 6C |

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-ATP | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 11 ± 2 | 0.995 | 0.990 | 7C |

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-CTP | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 3.8 ± 2.7 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 7D |

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-ATP | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 0.984 | 0.968 | 5B |

| 15N uptake | 13C/15N-ATP | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 28 ± 7 | 0.936 | 0.876 | 8B |

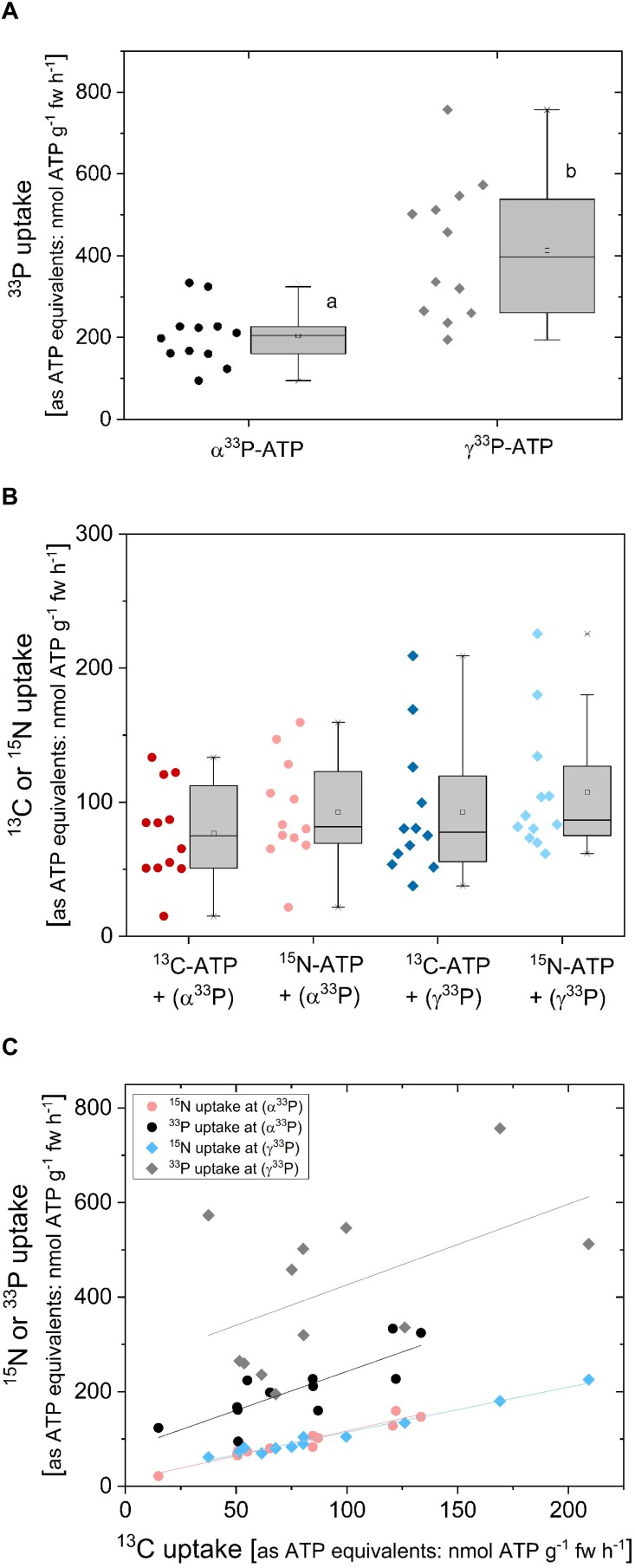

Comparison of 13C, 15N and 33P Uptake Rates Applied as Triple Labeled ATP Experiment

The correlation of 33P uptake rates with 13C and 15N uptake rates was investigated in a triple labeling approach (Figure 6) as a further approach to test for ATP uptake as an intact molecule. In this experiment, 33P-ATP was applied together with 10 atom% ATP-13C1015N5. As already observed in 33P-ATP labeling experiments (Figure 4B), 33P uptake rates equivalent to ATP were significantly lower when α33P-ATP instead of γ33P-ATP was applied (Figure 6A). The approximately 10-fold higher 33P uptake rates in this experiment (Figure 6A, carried out in November) compared to the experiment presented in Figure 4B (carried out in spring) may be due to seasonal differences, which have already been observed for Pi uptake under controlled conditions (Netzer et al., 2018). Both, 13C and 15N uptake rates equivalent to ATP were twofold lower compared to the 33P uptake rate equivalent to ATP when α33P-ATP and, approximately fourfold lower compared to the 33P uptake rate equivalent to ATP when γ33P-ATP was applied (Figure 6B). Correlation analyses were performed to elucidate the relationships between uptake rates equivalent to ATP calculated from 13C, 15N and 33P incorporation. 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents showed a strong correlation of 1.05 ± 0.09 (Table 1 and Figure 6C). 13C uptake rates shown less but still significant correlation to 33P uptake rates of 1.64 ± 0.39 (P = 0.817, r2 = 0.668, y intercept = 78 ± 31) when α33P-ATP and of 1.71 ± 0.90 (P = 0.514, r2 = 0.264, y intercept = 255 ± 95) when γ33P-ATP was applied. These results support the view of an uptake of AMP and the nucleoside adenosine by the roots.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of 33P, 13C, and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents of excised poplar roots applied as 33P and 13C/15N labeled ATP. Uptake experiments (n = 12) were carried out in late autumn, i.e., at the beginning of November by applying α33P-ATP or γ33P-ATP (∼5.3∗107 Bq mmol-1) together with 13C/15N labeled ATP (ATP-13C1015N5; 10 atom%) at the final concentration of 0.169 mM ATP. (A) 33P uptake rates were calculated in ATP equivalents. The rate of 33P loaded into the xylem was calculated from 33P incorporation and amounted to 2.5 ± 1.1 nmol g-1 fw h-1 calculated as ATP equivalents in the case of α33P-ATP and to 8.3 ± 2.3 nmol g-1fw h-1 in the case of γ33P-ATP application. This corresponds to 1.5 ± 1.4 and 2.2 ± 0.9% of the 33P that was loaded into the xylem for the α33P-ATP and γ33P-ATP application, respectively. (B) 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents either for the γ33P-ATP or α33P-ATP treatment, respectively. (C) Correlation between 33P and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents and the respective 13C uptake rates as ATP equivalents. Correlation characteristics are given in Table 1. Significant differences were marked with different small letters (p < 0.05) and were analyzed by One Way ANOVA followed by the Post hoc tests Bonferroni and Tukey.

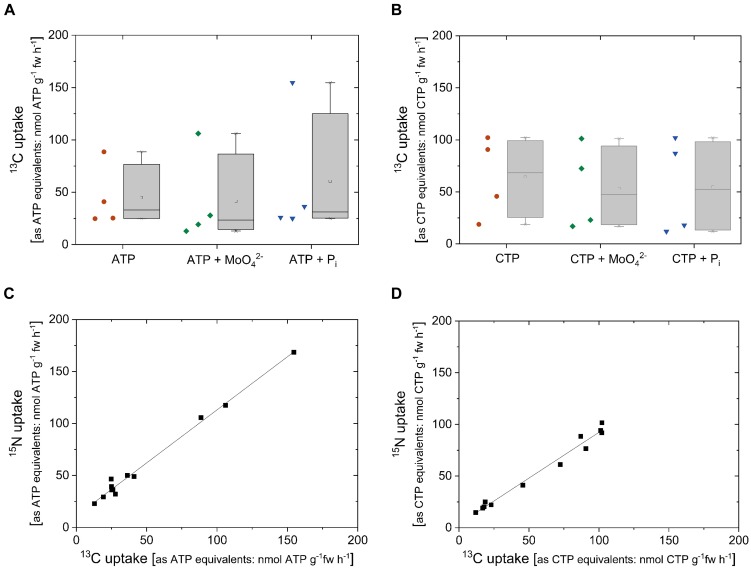

13C and 15N Uptake Rates Were Similar From 13C/15N-Labeled ATP and CTP

To address the question whether excised poplar roots can take up ribose together with the base from other nucleotides, cytosine triphosphate (CTP) was applied as CTP-13C915N3 (10 atom%, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Despite high variability, 13C uptake rates calculated as ATP (49 ± 44 nmol g-1 fw h-1, n = 12) and as CTP equivalents (57 ± 38 nmol g-1 fw h-1, n = 12) were similar. The same was found when the 15N uptake rates were calculated as ATP (61 ± 45 nmol g-1 fw h-1, n = 12) and CTP equivalents (55 ± 34 nmol g-1 fw h-1, n = 12). This result was irrespective of the addition of MoO42- as acid phosphatase inhibitor or the addition of Pi for competition (Figure 7). The relationship between 13C uptake and 15N uptake as nucleotide equivalents reached a correlation of 1.02 ± 0.03 for ATP and of 0.89 ± 0.04 for CTP (Table 1). These results show that neither the uptake of 13C nor the uptake of 15 N applied to excised poplar roots as double-labeled ATP or CTP was influenced by the acid phosphatase inhibitor molybdate or by Pi.

FIGURE 7.

13C and15N uptake rates as ATP/CTP equivalents of excised poplar roots achieved from 13C/15N labeled ATP or CTP. Excised poplar roots were taken from poplar plants grown with 0.25 mM Pi (July). 13C and 15N uptake rates calculated as ATP and CTP equivalents were analyzed by the application of 0.169 mM labeled ATP-13C1015N5 (10 atom%) or CTP-13C915N3 (10 atom%). The competition with Pi was tested by the addition of 0.25 mM Pi. The effect of acid phosphatases was investigated by the simultaneous application of nucleotides plus 0.5 mM MoO42-. Data presented are box plots for 13C uptake rates as ATP equivalents (A) and 13C uptake rates as CTP equivalents (B). Left to the box plots individual values achieved from single incubation cambers are presented (n = 4). 15N uptake rates as ATP and CTP equivalents were similar to the 13C uptake rates as ATP and CTP equivalents. Significant differences were analyzed by One Way ANOVA followed by the Post hoc tests Bonferroni and Tukey with p < 0.05 but, statistically significant differences were not found. Correlations over all treatments between 13C and 15N uptake rates are provided for ATP (C) and CTP (D). Slopes and Pearson correlation coefficients are given in Table 1.

13C, 15N, and 33P Uptake From the Respective Labeled ATP by Beech Roots

To compare the results achieved with poplar with another temperate forest tree species, uptake of 33P, 13C, and 15N from labeled ATP was investigated with excised roots from F. sylvatica seedlings. In parallel experiments, γ33P-ATP and 13C/15N double-labeled ATP (10 atom% ATP-13C1015N5) was applied (Supplementary Figure S2). 33P uptake rates equivalent to ATP after γ33P-ATP application amounted to 101 ± 31 nmol g-1 fw h-1 (Supplementary Figure S2). 33P uptake from γ33P-ATP was affected neither by Pi nor by the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42-. The latter coincide with the findings of poplar (Figure 4A). Xylem loading of 33P from γ33P-ATP was negligible in beech roots (data not shown). 13C and 15N uptake rates of beech roots equivalent to ATP (22 ± 7 and 30 ± 15 nmol g-1 fw h-1, respectively) amounted to one fourth of the 33P uptake equivalent to ATP. 13C and 15N uptake of beech roots as equivalent to ATP was also neither affected by Pi nor by the acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42-. The relationship between the 13C and 15N uptake equivalent to ATP showed a strong correlation of 1.004 ± 0.182 (Supplementary Figure S2) as also observed for poplar roots (Figure 5, 6).

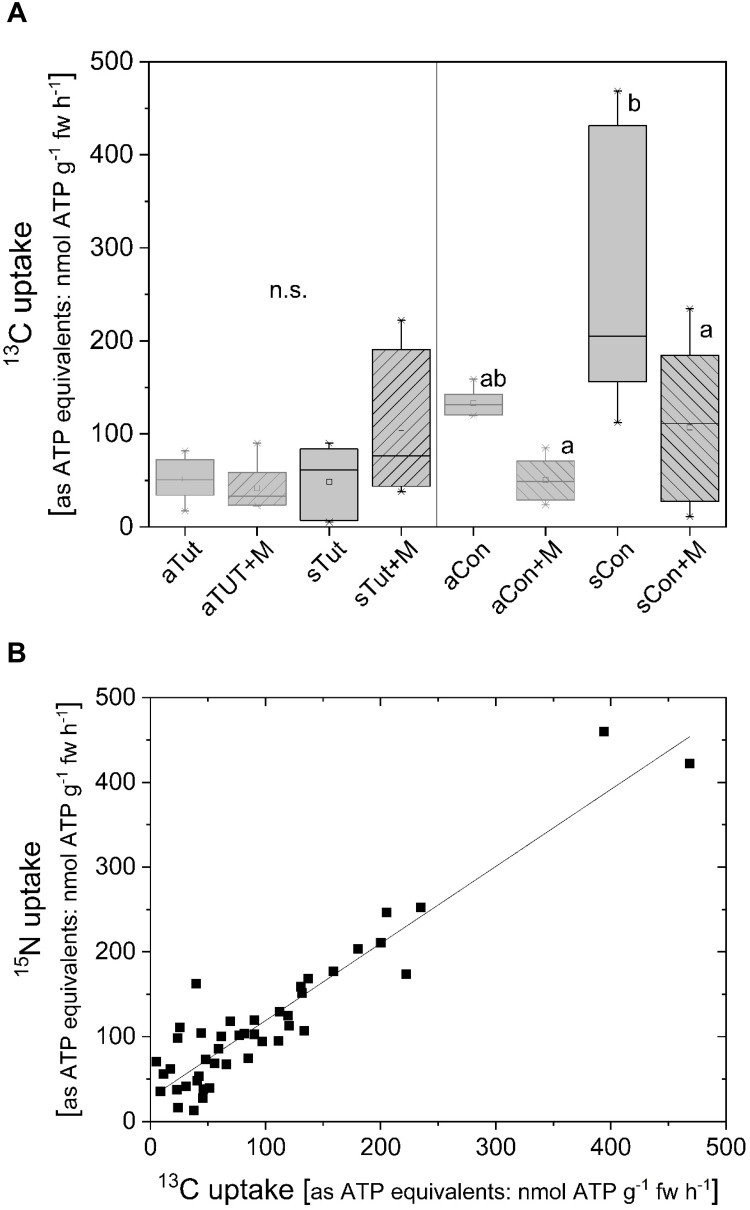

13C and 15N Uptake Rates From 13C/15N-Labeled ATP of Beech in the Field

13C and 15N uptake from double-labeled ATP was furthermore investigated at two beech forest stands characterized as low-P forests (Netzer et al., 2017). Different to the experiments under controlled condition, in the field roots of adult beech trees and their offspring were mycorrhizal and only 13C/15N double-labeled ATP could be applied to the roots still attached to trees. 13C uptake rates as ATP equivalents by beech roots of the extremely low-P forest stand Tut were comparable for adult beech trees and their offspring. Furthermore, inhibition of acid phosphatases by MoO42- did not affect 13C uptake rates equivalent to ATP (Figure 8A). In contrast, at the Con forest 13C uptake rates were higher compared to the Tut site for both, adult beech trees and their offspring (Figure 8A). At the Con forest, addition of MoO42- to inhibit acid phosphatases caused a decline in 13C uptake equivalent to ATP to the level observed for adult trees and their offspring at the Tut forest. 15N uptake as ATP equivalent was similar as calculated from the 13C uptake equivalent to ATP. Consequently, a strong correlation was found between the 13C and 15N uptake (0.91 ± 0.05, Table 1 and Figure 8B).

FIGURE 8.

13C uptake rates as ATP equivalents of beech roots still attached to adult trees and their offspring at two forest stands low in soil P. Roots of adult beech trees and their offspring at two forests, Tuttlingen (Tut, 9/21/2017) and Conventwald (Con, 9/19/2017) (Netzer et al., 2017), were excavated out of the soil and washed with distilled water. Roots still attached to the adults (n = 6) and offspring (n = 6) were incubated in an artificial soil solution (adapted to soil water composition of the respective forest site) at pH 5.0 with 0.169 mM 13C/15N labeled ATP (ATP13C10/15N5; 10 atom%). These conditions were selected for comparison reason with the experiments done under controlled conditions. Acid phosphatases were inhibited by the addition of 0.5 mM MoO42-. (A) 13C uptake rates as ATP equivalents of roots from adult beech tress from the Tut (aTut) and from the Con (aCon) forest as well as from the natural regeneration at the Tut (sTut) and Con (sCon) forest. Supplementation of molybdate (0.5 mM, MoO42-) is indicated by +M. 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents were comparable to the values received for 13C uptake. Statistically significant differences were analyzed by One Way ANOVA followed by the Post hoc tests Bonferroni and Tukey with p < 0.05. Different small letters for the Con forest indicate statistically differences at p < 0.05. At the Tut forest, statistically significant differences were not observed (n.s.). (B) The correlation between 13C and 15N uptake rates as ATP equivalents. Regression characteristics are given in Table 1.

Discussion

The present study indicates that poplar and beech roots take up P from nucleotides most probably after cleavage of Pi although uptake of ADP and/or AMP cannot be excluded. However, the present study also indicates that AMP or at least adenosine can be taken up by tree roots as a whole molecule and contributes not only to P but also to N acquisition of the trees. The common assumption for P acquisition by plants, however, is that plants can take up only Pi (Chiou and Lin, 2011). Important Porg compounds in the rhizosphere are phosphoric acid anhydrides such as ADP and ATP (Huang et al., 2017), which are hardly detectable in natural environments because of their thermodynamic instability (De Nobili et al., 1996). Nevertheless, it can be assumed that ATP is available around plant roots from dead and destroyed microbial biomass (Lareen et al., 2016) and root exudation (Tanaka et al., 2010, 2014). The latter one led to the abundance of extracellular ATP in regions of active growth and cell expansion at the root surface of Medicago truncatula (Kim et al., 2006). Around roots of different plant species, the depletion of Porg correlated with acid and alkaline phosphatase activity (Tarafdar and Jungk, 1987). Consequently, Pi becomes available for uptake after cleavage from organic bound P (Porg) by phosphatases (Smith et al., 2015; Tian and Liao, 2015; Hofmann et al., 2016). Recent studies also showed that ecto-apyrases are essential for both, rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbiosis, presumably by modulating extracellular ATP levels (Tanaka et al., 2014). Ecto-apyrases cleave Pi from ATP and ADP, but not from AMP (Thomas et al., 1999; Okuhata et al., 2011). Apparently, cleavage of Pi from ATP by secreted phosphatases (Liang et al., 2010; Plaxton and Tran, 2011; Tian and Liao, 2015; Liu et al., 2016), ecto-apyrases (Thomas et al., 1999) and extracellular nucleotidases contribute to the extracellular breakdown of ATP into ADP, AMP and/or adenosine. Together with bidirectional transport of ATP and/or one of its degradation product(s) via the plasma membrane of root cells, ATP homeostasis can be controlled in the rhizosphere. Simultaneously, these processes contribute to the acquisition of P and N for plant nutrition.

‘Pro and Contra’ of ATP, ADP, AMP and/or Adenosine Uptake

33P in γ33P-ATP can enter the root as intact ATP molecule or as Pi after cleavage by phosphatases and/or ecto-apyrases that are commonly present in the rhizosphere (see section “Discussion” above). The acid phosphatase inhibitor MoO42- did not affect 33P uptake calculated as ATP equivalents when γ33P-ATP was applied to excised non-mycorrhizal poplar or beech roots. This result indicates uptake of the intact γ33P-ATP molecule. If this assumption is correct, the labeling position of the 33P should not affect 33P uptake. However, when the αP of ATP was labeled, 33P uptake calculated as ATP equivalents was lower compared to the 33P uptake from γ33P-ATP. Both, phosphatases and ecto-apyrases can cleave the γPi and βPi unit from ATP, thereby contributing to the control of extracellular ATP abundance (Plesner, 1995; Song et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2007; Clark et al., 2010; Haferkamp et al., 2011). As MoO42- does not inhibit plasma membrane apyrases of plant roots (i.e., Gallagher and Leonard, 1982; Thomas et al., 1999), they can still cleave the γPi and βPi unit from ATP in the presence of molybdate. Hence, it can be concluded that 33Pi might be cleaved from γ33P-ATP by this group of enzymes prior its uptake by poplar roots. This conclusion is also evident from the high offset when the 33P uptake from γ33P-ATP is compared to the 13C uptake expressed as ATP equivalents (Table 1) and is further supported by competition experiments. Addition of Pi to γ33P-ATP diminished 33P uptake by poplar roots, however, not by beech roots. Either Pi diluted the 33Pi pool cleaved from γ33P-ATP by phosphatases, ecto-apyrases and/or nucleotidases excreted by the roots or Pi functions as competitive inhibitor of ATP uptake by poplar roots; vice versa, ATP did not affect Pi uptake (Figure 3). For excised beech roots, addition of Pi did not affect 33P uptake from γ33P-ATP, strongly supporting the idea of intact γ33P-ATP uptake (Supplementary Figure S2A). However, 33P-Pi uptake by excised beech roots was diminished in the presence of ATP. Together these findings support the common assumption that Pi needs to be cleaved from organic bound P prior Pi is taken up by phosphate transporters (Kavka and Polle, 2016, 2017; Versaw and Garcia, 2017), but they also support the idea of nucleotide uptake by nucleotide exchange transporters with different substrate specificity (Haferkamp et al., 2011).

The missing link for establishing nucleotide/nucleoside uptake by tree roots remains the identification of nucleotide transporters located at the root plasma membrane. Although adenine nucleotide transporters are characterized as ATP/ADP exchange carrier proteins at different cellular membranes (Leroch et al., 2008; Linka and Weber, 2010; Haferkamp et al., 2011), information about plasma membrane exchange carriers is scarce. To the best knowledge of the authors, only one report of a plasma membrane located ATP exporter has been published. This transporter is essential during pollen maturation in Arabidopsis (Rieder and Neuhaus, 2011) and coincidences with a signaling function of extracellular ATP (Roux and Steinebrunner, 2007; Tanaka et al., 2010, 2014). In contrast to ATP/ADP exchange carrier proteins, which so far have not been reported for the plasma membrane of root cells, nucleoside and nucleobase transporters have been described in a number of studies (Möhlmann et al., 2010; Cornelius et al., 2012; Girke et al., 2014; Niopek-Witz et al., 2014). Hence, after cleavage of all three Pi units from ATP by enzymes commonly occurring in the rhizosphere such as phosphatases, ecto-apyrases and/or nucleotidases, the remaining nucleoside adenosine can be taken up as complete molecule.

In the present experiments, the ribose and the base of adenosine were labeled with 13C, but only the base carried the 15N label (Figure 1). In both, excised beech and poplar roots, 13C and 15N uptake rates determined as ATP or CTP equivalents, were similar and showed a strong correlation to each other (Table 1). Hence, separate uptake of the nucleobase and the ribose unit after hydrolysis by extracellular nucleoside hydrolases (Jung et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 2014) seems highly improbable. However, the strong correlation between 13C and 15N uptake does not indicate whether ADP, AMP and/or adenosine is taken up after cleavage of the γP, βP, and αP. Rather, the offset of the 15N uptake observed in all experiments (Table 1) indicates a slightly higher 15N uptake compared to 13C that can be attributed to the cleavage into ribose and the nucleobase by nucleoside hydrolases (Jung et al., 2011). Whether the base and the ribose units from nucleosides are taken up separately (Riewe et al., 2008; Jung et al., 2011; Tanaka et al., 2014) by nucleobase (Girke et al., 2014) and sugar transporters (Williams et al., 2000) needs further studies.

Still, 13C and 15N uptake rates by excised poplar roots determined as ATP equivalents decreased, however, not statistically significant, at higher temperatures when MoO42- inhibited extracellular acid phosphatase activity indicating uptake of AMP and/or adenosine after Pi cleavage. In addition, if attached roots of adult beech trees and their natural regeneration in the Con forest were exposed to 13C/15N labeled ATP plus MoO42-, 13C and 15N uptake as ATP equivalents declined. These results indicate uptake of ADP, AMP and/or adenosine after cleavage of at least one Pi unit. It is assumed that in the experiments with excised poplar roots higher temperature increased extracellular phosphatase activity and, hence, the cleavage of γP, βP, and αP from ATP. As a result, increasing amounts of ADP, AMP and/or adenosine are available for its uptake by roots. If MoO42- inhibited extracellular acid phosphatase activity under these conditions, Pi was not cleaved from ATP and the availability of ADP, AMP and adenosine for root uptake declined; although based on the literature ecto-apyrases upon MoO42- application were not inhibited (Tanaka et al., 2011) and can still cleave Pi from ATP and ADP. Thus, the relevance of Pi cleavage from ATP by phosphatases and/or ecto-apyrases for P acquisition under field conditions will depend on soil temperature and consequently also on the season, but also on the enzyme composition of the rhizosphere.

Under field conditions, the uptake of 13C and 15N from the ATP applied furthermore depends on other factors at the forest stand. Tree roots interact with physical, chemical and biological properties of the soil in the rhizosphere (Richardson et al., 2009). Differences of 13C and 15N uptake rates from ATP between the Tut and the Con forest stands may thus be linked to different soil characteristics of the two forest stands. (i) The soils differ in pH, ranging from 5.7 to 7.5 for the calcareous Tut site and from 3.6 to 4.3 for the silicate Con forest, as well as in plant available soil Pi (Tut: 0.03 ± 0.01 μmol L-1 and Con: 0.23 ± 0.18 μmol L-1) (for detailed soil description see Prietzel et al., 2016; Netzer et al., 2017). Acid phosphatases are highly active at acidic soil conditions (i.e., Bozzo et al., 2002) that are given at the Con forest (Prietzel et al., 2016) and may be of higher importance at the Con compared to the Tut stand. (ii) In addition, the microbial activity and mycorrhizal communities differ between the two study sites (Leberecht et al., 2016a,b; Zavišić et al., 2016), most likely with the consequence of differences in phosphatase secretion (Hofmann et al., 2016). The microbial biomass in the rhizosphere consists of active as well as of inactive and dead microbes and usually is quantified in “static” approaches, mainly based on the single-stage determination of cell components such as ATP, DNA, and RNA (Blagodatskaya and Kuzyakov, 2013). Hence, substantial amounts of ATP should be present in the rhizosphere as a P and N source, which will depend on seasonal and environmental differences affecting microbial activity. (iii) Finally, differences in phosphatase, ecto-apyrase and nucleotidase profiles of the beech rhizosphere between the two forest stands can affect Pi cleavage from ATP depending on environmental conditions such as soil Pi, pH, microbial activity and the season. The lower plant available nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil of the Tut compared to the Con forest (Rennenberg and Dannenmann, 2015) coincided with the lower 13C and 15N uptake from ATP of beech offspring in the present study. Therefore, it is concluded that the processes described above are highly significant in determining the nutrient availability in forest soils.

Author Contributions

CH and HR designed the research project. CH wrote the manuscript and supervised all experiments. US performed most of the experiments. NT performed experiments on the temperature influence on 13C/15N-ATP uptake. FN performed ATP uptake experiments in the field.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oliver Itzel for technical assistance in 15C10/15N5 labeled ATP uptake experiments and plant cultivation. We thank Prof. A. Polle for support in the context of SSP 1685 and the Kompetenzzentrum Stabile Isotope (KOSI, University of Göttingen) for measuring stable isotopes in part of the 13C/15N labeled root samples.

Funding. This present research was performed in the context of the priority program SPP 1685 - Ecosystem nutrition: forest strategies for limited phosphorus resources that was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). The DFG financially supported the present work under the project numbers HE 3003/6-1 and HE 3003/6-2, which is gratefully acknowledged. The German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Freiburg in the funding program Open Access Publishing funded the article processing charge.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.00378/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bieleski R. L. (1973). Phosphate pools, phosphate transport, and phosphate availability. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 24 225–252. 10.1146/annurev.pp.24.060173.001301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blagodatskaya E., Kuzyakov Y. (2013). Active microorganisms in soil: critical review of estimation criteria and approaches. Soil Biol. Biochem. 67 192–211. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzo G. G., Raghothama K. G., Plaxton W. C. (2002). Purification and characterization of two secreted purple acid phosphatase isozymes from phosphate-starved tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) cell cultures. Eur. J. Biochem. 269 6278–6286. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünemann E. K., Augstburger S., Frossard E. (2016). Dominance of either physicochemical or biological phosphorus cycling processes in temperate forest soils of contrasting phosphate availability. Soil Biol. Biochem. 101 85–95. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Díaz J. M., Quiles F. A., Lambert R., Pineda M., Piedras P. (2012). Identification of a novel phosphatase with high affinity for nucleotides monophosphate from common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 53 54–60. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway R., Nadkarni N. (1991). Seasonal patterns of nutrient deposition in a Quercus douglasii woodland in central California. Plant Soil 137 209–222. 10.1007/BF00011199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodríguez V., Cañas R. A., de la Torre F. N., Belén Pascual M., Avila C., Cánovas F. M. (2017). Molecular fundamentals of nitrogen uptake and transport in trees. J. Exp. Bot. 68 2489–2500. 10.1093/jxb/erx037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick O. A., Derry L. A., Vitousek P. M., Huebert B. J., Hedin L. O. (1999). Changing sources of nutrients during four million years of ecosystem development. Nature 397 491–497. 10.1038/17276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. C., Liao H. (2016). Organic acid anions: an effective defensive weapon for plants against aluminum toxicity and phosphorus deficiency in acidic soils. J. Genet. Genomics 43 631–638. 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou T.-J., Lin S.-I. (2011). Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62 185–206. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark G., Wu M., Wat N., Onyirimba J., Pham T., Herz N., et al. (2010). Both the stimulation and inhibition of root hair growth induced by extracellular nucleotides in Arabidopsis are mediated by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Plant Mol. Biol. 74 423–435. 10.1007/s11103-010-9683-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius S., Traub M., Bernard C., Salzig C., Lang P., Möhlmann T. (2012). Nucleoside transport across the plasma membrane mediated by equilibrative nucleoside transporter 3 influences metabolism of Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Biol. 14 696–705. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenmann M., Simon J., Gasche R., Holst J., Naumann P. S., Kögel-Knabner I., et al. (2009). Tree girdling provides insight on the role of labile carbon in nitrogen partitioning between soil microorganisms and adult European beech. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41 1622–1631. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.04.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Nobili M., Diaz-Ravina M., Brookes P. C., Jenkinson D. S. (1996). Adenosine 5’– triphosphatemeasurements in soils containing recently added glucose. Soil Biol. Biochem. 28 1099–1104. 10.1016/0038-0717(96)00074-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S. R., Leonard R. T. (1982). Effect of vanadate, molybdate, and azide on membrane-associated ATPase and soluble phosphatase activities of corn roots. Plant Physiol. 70 1335–1340. 10.1104/pp.70.5.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler A., Rienks M., Rennenberg H. (2000). NH3 and NO2 fluxes between beech trees and the atmosphere - correlation with climatic and physiological parameters. New Phytol. 147 539–560. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler A., Rienks M., Rennenberg H. (2002). Stomatal uptake and cuticular adsorption contribute to dry deposition of NH3 and NO2 to needles of adult spruce (Picea abies) trees. New Phytol. 156 179–194. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler A., Schneider S., von Sengbusch D., Weber P., Hanemann U., Huber C., et al. (1998). Field and laboratory experiments on net uptake of nitrate and ammonium by roots of spruce (Picea abies) and beech (Fagus sylvatica) trees. New Phytol. 138 275–285. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigolashvili T., Kopriva S. (2014). Transporters in plant sulfur metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 5:442. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girke C., Daumann M., Niopek-Witz S., Möhlmann T. (2014). Nucleobase and nucleoside transport and integration into plant metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 5:443. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel M.-O., Adams F., Boy J., Guggenberger G., Mikutta R. (2017). Mobilization of glucose-6-phosphate from ferrihydrite by ligand-promoted dissolution is higher than of orthophosphate. J. Plant Nut. Soil Sci. 180 279–282. 10.1002/jpln.201600479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haferkamp I., Fernie A. R., Neuhaus H. E. (2011). Adenine nucleotide transport in plants: much more than a mitochondrial issue. Trends Plant Sci. 16 507–515. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschbach C. (2003). Whole plant regulation of sulfur nutrition of deciduous trees - Influences of the environment. Plant Biol. 5 233–244. 10.1055/s-2003-40799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herschbach C., Rennenberg H. (1991). Influence of glutathione (GSH) on sulfate influx, xylem loading and exudation in excised tobacco roots. J. Exp. Bot. 42 1021–1029. 10.1093/jxb/42.8.1021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herschbach C., Scheerer U., Rennenberg H. (2010). Redox states of glutathione and ascorbate in root tips of poplar (Populus tremula x P. alba) depend on phloem transport from the shoot to the roots. J. Exp. Bot. 61 1065–1074. 10.1093/jxb/erp371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsinger P. (2001). Bioavailability of soil inorganic P in the rhizosphere as affected by root-induced chemical changes: a review. Plant Soil 237 173–195. 10.1023/A:1013351617532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsinger P., Herrmann L., Lesueur D., Robin A., Trap J., Waithaisong K., et al. (2015). Impact of roots, microorganisms and microfauna on the fate of soil phosphorus in the rhizosphere. Annu. Plant Rev. 48 377–408. 10.1002/9781118958841.ch13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland D., Arnon D. (1950). The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K., Heuck C., Spohn M. (2016). Phosphorus resorption by young beech trees and soil phosphatase activity as dependent on phosphorus availability. Oecologia 181 369–379. 10.1007/s00442-016-3581-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honsel A., Kojima M., Haas R., Frank W., Sakakibara H., Herschbach C., et al. (2012). Sulphur limitation and early sulphur deficient responses in poplar: significance of gene expression, metabolites and plant hormones. J. Exp. Bot. 63 1873–1893. 10.1093/jxb/err365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Zhou M., Dannenmann M., Saiz G., Simon J., Bilela S., et al. (2017). Comparison of nitrogen nutrition and soil carbon status of afforested stands established in degraded soil of the Loess Plateau. China. For. Ecol. Manage. 389 46–58. 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.-M., Jia X.-X., Zhang G.-L., Shao M.-A. (2017). Soil organic phosphorus transformation during ecosystem development: a review. Plant Soil 417 17–42. 10.1007/s11104-017-3240-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansa J., Finlay R., Wallander H., Smith F. A., Smith S. E. (2011). “Role of mycorrhizal symbioses in phosphorus cycling,” in Phosphorus in Action, eds Bünemann E. K., Oberson A., Frossard E. (Heidelberg: Springer; ), 137–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L., Oburger E. (2011). “Solubilization of phosphorus by soil microorgansim,” in Phosphorus in Action, eds Bünemann E. K., Oberson A., Frossard E. (Heidelberg: Springer; ), 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jung B., Hoffmann C., Möhlmann T. (2011). Arabidopsis nucleoside hydrolases involved in intracellular and extracellular degradation of purines. Plant J. 65 703–711. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser K., Guggenberger G., Haumaier L. (2003). Organic phosphorus in soil water under a European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) stand in northeastern Bavaria, Germany: seasonal variability and changes with soil depth. Biogeochemistry 66 287–310. 10.1023/B:BIOG.0000005325.86131.5f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavka M., Polle A. (2016). Phosphate uptake kinetics and tissue specific transporter expression profiles in poplar (Populus × Canescens) at different phosphorus availabilities. BMC Plant Biol. 16:206. 10.1186/s12870-016-0892-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavka M., Polle A. (2017). Dissecting nutrient-related co-expression networks in phosphate starved poplars. PLoS One 12:e0171958. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-Y., Sivaguru M., Stacey G. (2006). Extracellular ATP in plants. Visualization, localization, and analysis of physiological significance in growth and signalling. Plant Physiol. 142 984–992. 10.1104/pp.106.085670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzwieser J., Herschbach C., Rennenberg H. (1996). Sulfate uptake and xylem loading of non-mycorrhizal excised roots of young Fagus sylvatica trees. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 34 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H., Clode P. L., Hawkins H.-J., Laliberté E., Oliveira R. S., Reddell P., et al. (2015a). Metabolic adaptations of the non-mycotrophic proteaceae to soil with low phosphorus availability. Annu. Plant Rev. 48 289–336. 10.1002/9781118958841.ch11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H., Martinoia E., Renton M. (2015b). Plants adaptations to severally phosphorus-impoverished soils. Curr. Opi. Plant Biol. 25 23–31. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H., Raven J. A., Shaver G. R., Smith S. E. (2008). Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23 95–103. 10.1016/j.tree.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F., Krüger J., Amelung W., Willbold S., Frossard E., Bünemann E. K., et al. (2017). Soil phosphorus supply controls P nutrition strategies of beech forest ecosystems in Central Europe. Biogeochemistry 136 5–29. 10.1007/s10533-017-0375-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lareen A., Burton F., Schäfer P. (2016). Plant root-microbe communication in shaping root microbiomes. Plant Mol. Biol. 90 575–587. 10.1007/s11103-015-0417-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leberecht M., Dannenmann M., Tejedor J., Simon J., Rennenberg H., Polle A. (2016a). Segregation of nitrogen use between ammonium and nitrate of ectomycorrhizas and beech trees. Plant Cell Environ. 39 2691–2700. 10.1111/pce.12820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leberecht M., Tu J., Polle A. (2016b). Acid and calcareous soils affect nitrogen nutrition and organic nitrogen uptake by beech seedlings (Fagus sylvatica L.) under drought, and their ectomycorrhizal community structure. Plant Soil 409 143–157. 10.1007/s11104-016-2956-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroch M., Neuhaus E., Kirchberger S., Zimmermann S., Melzer M., Gerhold J., et al. (2008). Identification of a novel adenine nucleotide transporter in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20 438–451. 10.1105/tpc.107.057554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Tian J., Lam H. M., Lim B. L., Yan X., Liao H. (2010). Biochemical and molecular characterization of PvPAP3, a novel purple acid phosphatase isolated from common bean enhancing extracellular ATP utilization. Plant Physiol. 152 854–865. 10.1104/pp.109.147918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linka N., Weber A. P. M. (2010). Intracellular metabolite transporters in plants. Mol. Plant 3 21–53. 10.1093/mp/ssp108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.-D., Xue Y.-B., Chen Z.-J., Liu G.-D., Tian J. (2016). Characterization of purple acid phosphatases involved in extracellular dNTP utilization in Stylosanthes. J. Exp. Bot. 67 4141–4154. 10.1093/jxb/erw190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner P., Crowley D., Rengel Z. (2011). Rhizosphere interactions between microorganisms and plants govern iron and phosphorus acquisition along the root axis e model and research methods. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43 883–894. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Möhlmann T., Bernard C., Hach S., Neuhaus H. E. (2010). Nucleoside transport and associated metabolism. Plant Biol. 12 26–34. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer F., Mueller C. W., Scheerer U., Grüner J., Kögel-Knabner I., Herschbach C., et al. (2018). Phosphorus nutrition of Populus x canescens reflects adaptation to high P-availability in the soil. Tree Physiol. 38 6–24. 10.1093/treephys/tpx126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer F., Schmid C., Herschbach C., Rennenberg H. (2017). Phosphorus-nutrition of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) during annual growth depends on tree age and P-availability in the soil. Environ. Exp. Bot. 137 194–207. 10.1093/treephys/tpx126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niopek-Witz S., Deppe J., Lemieux M. J., Möhlmann T. (2014). Biochemical characterization and structure–function relationship of two plant NCS2 proteins, the nucleobase transporters NAT3 and NAT12 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838 3025–3035. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhata R., Takishima T., Nishimura N., Ueda S., Tsuchiya T., Kanzawa N. (2011). Purification and biochemical characterization of a novel ecto-apyrase, MP67, from Mimosa pudica. Plant Physiol. 157 464–475. 10.1104/pp.111.180414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñuelas J., Poulter B., Sardans J., Ciais P., van der Velde M., Bopp L., et al. (2013). Human-induced nitrogen-phosphorus imbalance alter natural and managed ecosystems across the globe. Nat. Commun. 4:2934. 10.1038/ncomms3934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassard C., Dell B. (2010). Phosphorus nutrition of mycorrhizal trees. Tree Physiol. 30 1129–1139. 10.1093/treephys/tpq063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton W. C., Tran H. T. (2011). Metabolic adaptations of phosphate-starved plants. Plant Physiol. 156 1006–1015. 10.1104/pp.111.175281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesner L. (1995). Ecto-ATPases: identities and functions. Int. Rev. Cytol. 158 141–214. 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62487-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prietzel J., Klysubun W., Werner F. (2016). Speciation of phosphorus in temperate zone forest soils as assessed by combined wet-chemical fractionation and XANES spectroscopy. J. Plant Nut. Soil Sci. 179 168–185. 10.1002/jpln.201500472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rennenberg H., Dannenmann M. (2015). Nitrogen nutrition of trees in temperate forests - the significance of nitrogen availability in the pedosphere and atmosphere. Forests 6 2820–2835. 10.3390/f6082820 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rennenberg H., Schneider S., Weber P. (1996). Analysis of uptake and allocation of nitrogen and sulphur by trees in the field. J. Exp. Bot. 47 1491–1498. 10.1093/jxb/47.10.1491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A. E., Barea J.-M., McNeill A. M., Prigent-Combaret C. (2009). Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant Soil 321 305–339. 10.1007/s11104-009-9895-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder B., Neuhaus H. E. (2011). Identification of an Arabidopsis plasma membrane-located ATP transporter important for anther development. Plant Cell 23 1932–1944. 10.1105/tpc.111.084574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riewe D., Grosman L., Fernie A. R., Zauber H., Wucke C., Geigenberger P. (2008). A cell wall-bound adenosine nucleosidase is involved in the salvage of extracellular ATP in Solanum tuberosum. Plant Cell Physiol. 49 1572–1579. 10.1093/pcp/pcn127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux S. J., Steinebrunner I. (2007). Extracellular ATP: an unexpected role as a signaler in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 12 522–527. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer U., Haensch R., Mendel R. R., Kopriva S., Rennenberg H., Herschbach C. (2010). Sulphur flux through the sulphate assimilation pathway is differently controlled by adenosine 5’-phosphosulphate reductase under stress and in transgenic poplar plants overexpressing γ-ECS, SO, or APR. J. Exp. Bot. 61 609–622. 10.1093/jxb/erp327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Yuan L., Zhang J., Li H., Bai Z., Chen X., et al. (2011). Phosphorus dynamics: from soil to plant. Plant Physiol. 156 997–1005. 10.1104/pp.111.175232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J., Dannenmann M., Gasche R., Holst J., Mayer H., Papen H., et al. (2011). Competition for nitrogen between adult European beech and its offspring is reduced by avoidance strategy. For. Ecol. Manage. 262 105–114. 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.01.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. E., Anderson I. C., Smith F. A. (2015). Mycorrhizal associations and phosphorus acquisition: from cells to ecosystems. Annu. Plant Rev. 48 409–440. 10.1002/9781118958841.ch14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song C. J., Steinebrunner I., Wang X., Stout S. C., Roux S. J. (2006). Extracellular ATP induces the accumulation of superoxide via NADPH oxidases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140 1222–1232. 10.1104/pp.105.073072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimm B., Weisgerber H. (2008). “Populus × canescens,” in Enzyklopädie der Holzgewächse: Handbuch und Atlas der Dendrologie, eds Roloff A., Weisgerber H., Lang U. M., Stimm B. (Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; ). [Google Scholar]

- Stoelken G., Simon J., Ehlting B., Rennenberg H. (2010). The presence of amino acids affects inorganic N uptake in non-mycorrhizal seedlings of European beech (Fagus sylvatica). Tree Physiol. 30 1118–1128. 10.1093/treephys/tpq050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohm M., Jouanin L., Kunert K. J., Pruvost C., Polle A., Foyer C. H., et al. (1995). Regulation of glutathione synthesis in leaves of transgenic poplar (Populus tremula × P. alba) overexpressing glutathione synthetase. Plant J. 7 141–145. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07010141.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Choi J., Cao Y., Stacey G. (2014). Extracellular ATP acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signal in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 5:446. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Nguyen C. T., Libault M., Cheng J., Stacey G. (2011). Enzymatic activity of the soybean ecto-apyrase GS52 is essential for stimulation of nodulation. Plant Physiol. 155 1988–1998. 10.1104/pp.110.170910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T., Gilroy S., Jones A. M., Stacey G. (2010). Extracellular ATP signaling in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 20 601–608. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarafdar J. C., Jungk A. (1987). Phosphatase activity in the rhizosphere and its relation to the depletion of soil organic phosphorus. Biol. Fert. Soils 3 199–204. 10.1007/BF00640630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C., Sun Y., Naus K., Lloyd A., Roux S. (1999). Apyrase functions in plant phosphate nutrition and mobilizes phosphate from extracellular ATP. Plant Physiol. 119 543–551. 10.1104/pp.119.2.543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Liao H. (2015). The role of intracellular and secreted purple acid phosphatases in plant phosphorus scavenging and recycling. Annu. Plant Rev. 48 265–288. 10.1093/jxb/ers309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H. T., Hurley B. A., Plaxton W. C. (2010). Feeding hungry plants: the role of purple acid phosphatases in phosphate nutrition. Plant Sci. 179 14–27. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B. L., Condron L. M. (2013). Pedogenesis, nutrient dynamics, and ecosystem development: the legacy of T.W. Walker and J.K. Syers. Plant Soil 367 1–10. 10.1007/s11104-013-1750-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C. P., Uhde-Stone C., Allan D. L. (2003). Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol. 157 423–447. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaw W. K., Garcia L. R. (2017). Intracellular transport and compartmentation of phosphate in plants. Curr. Opi. Plant Biol. 39 25–30. 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A., Vestergren J., Gröbner G., Persson P., Schleucher J., Giesler R. (2013). Soil organic phosphorus transformations in a boreal forest chronosequence. Plant Soil 367 149–162. 10.1007/s11104-013-1731-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek P. M., Porder S., Houlton B. Z., Chadwick O. A. (2010). Terrestrial phosphorus limitation: mechanisms, implications, and nitrogen-phosphorus interactions. Ecol. Appl. 20 5–15. 10.1890/08-0127.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wilpert K., Kohler M., Zirlewagen D. (1996). Die Differenzierung des Stoffhaushalts von Waldökosystemen Durch die Waldbauliche Behandlung auf Einem Gneisstandort des Mittleren Schwarzwaldes. Ergebnisse aus der Ökosystemfallstudie Conventwald. Baden-Württemberg: Mitteilungen der Forstlichen Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. W., Syers J. K. (1976). The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 15 1–19. 10.3390/ijerph14121475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. E., Lemoine R., Sauer N. (2000). Sugar transporters in higher plants – a diversity of roles and complex regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 5 283–290. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01681-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Steinebrunner I., Sun Y., Butterfield T., Torres J., Arnold D., et al. (2007). Apyrases (nucleoside triphosphate-diphosphohydrolases) play a key role in growth control in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 144 961–975. 10.1104/pp.107.097568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Wang B., Farris B., Clark G., Roux S. J. (2015). Modulation of root skewing in Arabidopsis by apyrases and extracellular ATP. Plant Cell Physiol. 56 2197–2206. 10.1093/pcp/pcv134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavišić A., Nassal P., Yang N., Heuck C., Spohn M., Marhan S., et al. (2016). Phosphorus availabilities in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests impose habitat filtering on ectomycorrhizal communities and impact tree nutrition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 98 127–137. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zieger S. L., Ammerschubert S., Polle A., Scheu S. (2017). Root-derived carbon and nitrogen from beech and ash trees differentially fuel soil animal food webs of deciduous forests. PLoS One 12:e0189502. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.