The erector spinae plane (ESP) block has been used to provide opioid-sparing analgesia in lumbar spine surgery, with the dorsal rami of spinal nerves as the primary target of action [1]. However the ensuing nerve blockade with fascial plane blocks may not always be dense or complete, as evidenced by inconsistent loss of cutaneous sensation to cold or pinprick testing [2]. Here we report a modified ESP block technique that may augment analgesic efficacy and potentially eliminate the need for perioperative opioids. Patient consent was obtained for this report. A healthy 51-year-old man, weighing 91 kg, with right-sided sciatica presented for laminectomy of the L4 and L5 vertebrae (without instrumentation) via a 6 cm midline incision. General anesthesia was induced with IV propofol 200 mg, succinylcholine 140 mg, and rocuronium 50 mg, and maintained with sevoflurane in an air-oxygen mixture. The patient was turned into a prone position and we performed bilateral pre-incisional ESP blocks at the level of the L4 transverse process. Fifteen ml of a 1 : 1 mixture of 0.5% ropivacaine and 1% lidocaine was injected into the fascial plane between the erector spinae muscle and transverse process tip on each side. The needle tip was then withdrawn to a position immediately superficial to the posterior investing fascia of the erector spinae muscle, where an additional 10 ml of local anesthetic was injected (Figs. 1A and 1B). IV acetaminophen 1 g, ketorolac 30 mg, and dexamethasone 10 mg were administered as co-analgesics. There was no hemodynamic response to surgical stimuli (skin incision, muscle dissection, and resection of spinous processes and laminae down to the level of the pars interarticularis) and consequently no opioids were administered intraoperatively. Surgical wound infiltration with local anesthetic was not performed. Upon emergence, the patient reported no pain at the surgical site, and required no additional analgesia during his 30-minute stay in the post-anesthetic care unit, or in the phase 2 recovery unit. Cutaneous sensory testing was unfortunately not possible due to the wound dressing. He was discharged home the same day with a prescription for ibuprofen 800 mg 6–8-hourly and oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg 6–8-hourly as needed. On telephone follow-up on postoperative days 1 and 2, he reported only mild discomfort that did not necessitate the use of any analgesic medication.

Fig. 1.

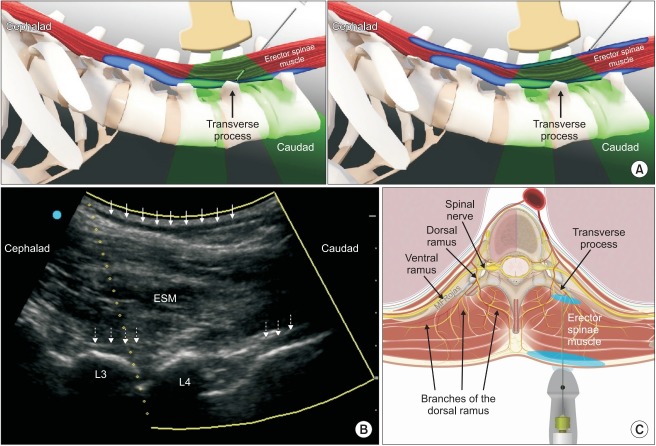

(A) In the conventional erector spinae plane (ESP) block, local anesthetic is injected into the musculofascial plane deep to the erector spinae muscle (left panel). In the modified dual-injection ESP block, a second injection of local anesthetic is made into the musculofascial plane superficial to the erector spinae muscle as a needle is withdrawn towards the skin (right panel) (Image used with permission from Twin Oaks Anesthesia Services, LLC). (B) Longitudinal parasagittal ultrasonographic view of the erector spinae muscle (ESM) overlying the articular and transverse processes of the L3 and L4 vertebrae. A dark hypoechoic layer of local anesthetic (solid arrows) can be seen spreading superficial to the hyperechoic posterior investing fascia of ESM. Another layer of local anesthetic (dotted arrows) is visible deep to ESM and superficial to the hyperechoic bony surfaces of the vertebral column. (C) The branches of the dorsal rami of spinal nerves innervate the vertebrae and paraspinal tissues. By depositing local anesthetic (blue shaded areas) into two separate fascial planes superficial and deep to the erector spinae muscle, the branches of the dorsal rami are blocked at both proximal and distal locations (Image adapted and used with permission from Maria Fernanda Rojas Gomez).

In our experience, cutaneous sensory loss is not always discernable following ESP blocks, and anesthetized patients may still respond to the initial skin incision. We postulate that this is due to the variability inherent in local anesthetic spread to the different tissue planes and paraspinal compartments. The onset time of conduction blockade may be an additional contributing factor, particularly if dilute long-acting local anesthetics are used. As we have demonstrated here, the quality of analgesia provided in spine surgery may be significantly augmented by a dual-injection technique into the fascial planes superficial as well as deep to the erector spinae muscle. This blocks the nerve branches of the dorsal rami at two separate locations (proximal as well as distal) along their anatomical course (Fig. 1C), which helps ensure adequate conduction blockade. The superficial injection mimics the subcutaneous local anesthetic wound infiltration often performed by surgeons at closure, but with the advantage that this can be done prior to incision with consequent intraoperative opioid-sparing and preventive analgesic effects. We used a mixture of ropivacaine and lidocaine to achieve a faster onset of action [3] and ensure adequate blockade at commencement of surgery, thus avoiding the need for intraoperative analgesic supplementation with opioids. This simple modification to the ESP block is easily accomplished in the same needle pass and carries little additional risk as long as the total dose of local anesthetic remains within maximum recommended limits. The prolonged duration of analgesia is more difficult to explain, but we hypothesize that it is due to a combination of dexamethasone-induced prolongation of conduction blockade [4], as well as preventive and multimodal analgesic mechanisms [5].

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Jonathan Kline (Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing – original draft) Ki Jinn Chin (Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing – review & editing)

References

- 1.Melvin JP, Schrot RJ, Chu GM, Chin KJ. Low thoracic erector spinae plane block for perioperative analgesia in lumbosacral spine surgery: a case series. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:1057–65. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunigo T, Murouchi T, Yamamoto S, Yamakage M. Injection volume and anesthetic effect in serratus plane block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:737–40. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, Ripart J, Boyer JC, Dehour L, Mahamat A, et al. A comparison of the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of bupivacaine, ropivacaine (with epinephrine) and their equal volume mixtures with lidocaine used for femoral and sciatic nerve blocks: a double-blind randomized study. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:641–9. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819237f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pehora C, Pearson AM, Kaushal A, Crawford MW, Johnston B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011770.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly DJ, Ahmad M, Brull SJ. Preemptive analgesia I: physiological pathways and pharmacological modalities. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:1000–10. doi: 10.1007/BF03016591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]