Abstract

Background:

Adult learning theories play a pivotal role in the design and implementation of education programs, including healthcare professional programs. There is a variation in the use of theories in healthcare professional education programs and this is may be in part due to a lack of understanding of the range of learning theories available and paucity of specific, in-context examples, to help educators in considering alternative theories relevant to their teaching setting. This article seeks to synthesize key learning theories applicable in the learning and teaching of healthcare professionals and to provide examples of their use in context.

Method and results:

A literature review was conducted in 2015 and 2016 using PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC academic databases. Search terms used identified a range of relevant literature about learning theories, and their utilization in different healthcare professional education programs. The findings were synthesized and presented in a table format, illustrating the learning theory, specific examples from health and medical education, and a very brief critique of the theory.

Outcome:

The literature synthesis provides a quick and easy-to-use summary of key theories and examples of their use to help healthcare professional educators access a wider range of learning theories to inform their instructional strategies, learning objectives, and evaluation approaches. This will ultimately result in educational program enhancement and improvement in student learning experiences.

Keywords: adult learning theories, social theories of learning, communities of practice, constructivist, healthcare professional education

Introduction

Educational philosophy and learning theory underpin all educational practices, because they provide the conceptual frameworks describing an individual’s acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes to achieve changes in behavior, performance, or potential.1,2

The discussion of adult learning theories leads to a discussion of the term “andragogy” (andr- meaning “man”), which is different from the term pedagogy (paid-meaning “child”), while in both terms “agogos” means “leading.” The term “andragogy” was developed by Alexander Kapp,3 a German teacher, and was later linked to the work of Knowles,4 who argued that adults are differently experienced, motivated, oriented, and in need to learn, than children. Knowles’s ideas are particularly important in professional education, because they focus on identifying and dealing with differences between what learners already know and what they learn within the experiential component of their programs.5 It is important to note that the use of the term andragogy has been criticized because some principles of andragogy are similar to that of children’s learning, which makes the learning a lifelong “continuum” with different purposes at different stages. Nevertheless, Knowles’s ideas have guided the development of teaching strategies that are suitable for adult learning.6,7

An understanding of adult learning theories (ie, andragogy) in healthcare professional education programs is important for several reasons. First, educational philosophies and theories are an essential part of evidence-based educational practice. Second, an understanding of different learning theories can help educators to select the best instructional strategies, learning objectives, assessment and evaluation approaches, based on context and environment for learning.1 Third, educators should be able to integrate learning theories, subject matter, and student understanding to improve student learning.2 Finally, being able to draw on learning theories to explain the impact of individual student differences on their learning outcomes could possibly exempt educators from taking sole responsibility for everything during the learning process.8 Educational psychology offers a variety of adult learning theories,1 and healthcare professional educators need to understand these theories and use this understanding in selecting and justifying the educational activities that they apply, so that these activities have a solid theoretical foundation based on the learning environment and setting.1

Important learning pedagogies should have a role in the education of healthcare professionals, in the undergraduate,9,10 the graduate,11,12 and in continuous professional development (CPD) programs.13,14 However, learning pedagogies are often not fully implemented in the educational design of healthcare professional education programs or in the pedagogical practice, whether undergraduate, or graduate or CPD.15–18

The objective of this article is to synthesize and summarize published work on adult learning theories and their application in healthcare professional education in a user-friendly format, illustrating specific examples of the uses of these theories in practice. It is hoped that this will enable healthcare professional educators to understand the significance of learning theories, select, and ultimately apply the most appropriate learning theory with its associated educational activities suitable for their learning environment and context.

Methods

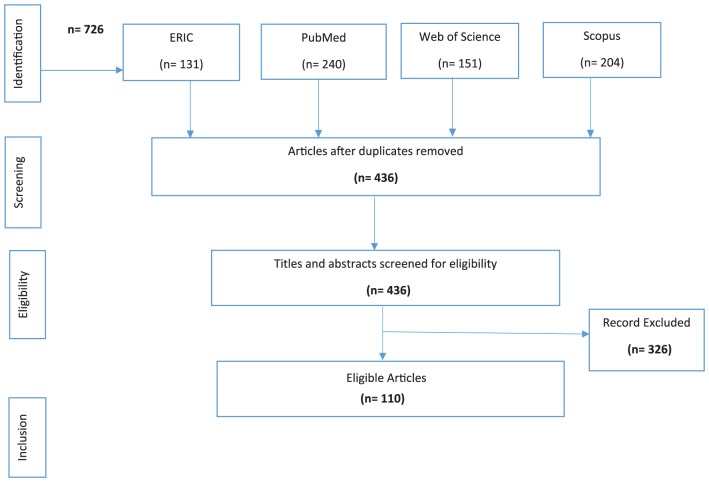

A literature search of learning theories in healthcare professional education was conducted in 2015 and updated in 2016, using the following academic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC. The search was conducted with combinations of the following search terms: education theory, educational model, learning theory, teaching method, medical education method, psychological theory, healthcare/healthcare education, healthcare professional education, and medical education. All specified search terms were used in different combinations using Boolean operators/connectors (AND/OR), as appropriate to the respective databases. Keywords were favored over MeSH terms to ensure consistency of search strategy among the different databases used, and terms were searched anywhere within the publication (no restriction to title, abstract, or body of publication). The criteria for inclusion of publications were books or articles electronically available in their entirety, published in English, from January 1999 to October 2016, concerning the identification, or categorization, or explanation learning theories, or the discussion of their application in educational practices in undergraduate, graduate, or CPD programs in any healthcare professional field. Excluded from this review were editorials, letters, opinion articles, commentaries, essays and preliminary notes, as well as duplicate publications in more than one database, theses, dissertations, and abstracts of conferences. The number of eligible articles and the process of selection are demonstrated in the four-step Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart in Figure 1. However, in Table 1, “categorization of learning theories used in health professional education programs,” which identified, compiled, and synthesized eligible articles, we included and cited articles that highlighted learning theories’ categorizations and use, but excluded those that repeated or used the same theories as those included.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Categorization of learning theories used in health professional education programs.

| Learning theory | Sub-category | Originator/s (year) | Application in healthcare professional education | Context | Criticism/limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Instrumental learning theories: focus on the learner’s individual experience | 1.1. Behavioral theories | Thorndike (1911),19 Pavlov (1927)20 and Skinner (1954)21 | Professional healthcare education: the behavioral theories are used in an undergraduate human physiology laboratory course for health students where students are provided with clear protocols to complete lab experiments, and an opportunity for immediate feedback through clicker questions to indicate how successfully the instructions were followed. The summative points are used as a positive reinforcer or punishment, using a grading scale of A, B, C, D, and F to progressively shape behavior to achieve the final target behavior of making accurate measurements, correctly reported22 | Undergraduate | Lack of clarity regarding the best method to determine the standardization of outcomes.7

Ignorance of the social aspects of learning23 |

| Pharmacy education: the behavioral theories are the basis for developing frameworks that measure clinical performance, such as the Foundation Pharmacy Framework (FPF) and the Advanced Pharmacy Framework (APF) (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013; Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2014)24 | Continuous professional development (CPD) | ||||

| 1.2. Cognitivism | Piaget and Cook (1952)25 and Bruner (1966)26 | Medical education: the cognitivist learning paradigm is useful in designing conceptual material systems, such as concept maps, which help students to recall foundational concepts and understand their complicated relationships27 | Undergraduate | Association with positivist assumption, because it considers that knowledge is abstract and symbolic, based on classroom, and not socially constructed. The theory thus underestimates the external dimensions of learning in practice settings28

Inadequate development of the attitudes of healthcare professionals, because of the focus on the acquisition of knowledge and skills without valuing learning in real practice29 |

|

| Nursing education: the cognitivist learning approach is applied in simulation-based experiences, where the learners internally control the conceived knowledge by utilizing previous knowledge and creating new knowledge30 | Undergraduate | ||||

| 1.3. Experiential learning | Kolb (1984)31 | Healthcare professional education: experiential learning theory values the practice of professional skills in real life contexts, and hence can be used to design learning strategies for constructing theoretical knowledge, and to develop competencies for professional practice10 | Undergraduate Graduate CPD |

Focusing solely on individual knowledge development and experience without considering the social context of that experience and its influence on what is learned7

In reality learning itself is much more complex and fragmented than is represented by Kolb’s31 four-phase cycle10 |

|

| Pharmacy education: experiential learning is a skill that provides lifelong learning and encourages a student’s adaptation to the practical environment. Through reflection, pharmacy practitioners reflect on both positive and negative learning experiences and make decisions based on clinical judgments32 | Undergraduate Graduate |

||||

| 2. Humanistic theories or facilitative learning theories These theories promote individual development and are more learner-centered | 2.1. Self-directed learning | Rogers (1963),33 Maslow (1968),34 and Knowles (1988)4 | Medical and healthcare professional education: self-directed learning is applied through technology-based simulations, problem-solving, and role-play experiments that focus on self-direction and self-assessment.35 This theory is useful as a facilitative learning approach to learn about dealing with unusual and difficult patient cases27 | Undergraduate Graduate |

Do not consider the influence of culture, society, and institutional structures on the learning process36

Do not consider other forms of learning, such as collaborative learning7 |

| Pharmacy education: self-directed learning paradigm is applied in CPD programs, which are designed to support lifelong learning for pharmacists14 | CPD | ||||

| 3. Transformative learning theories | Critical reflection | Mezirow (1978, 1990, 1997)37–39 | Medical education: transformative learning theories are used through critical incident analysis and group discussions, where teachers encourage learners to reflect on their assumptions and beliefs, share ideas and examine specific reflective practices27 | Undergraduate | Depends heavily on critical reflection while minimizing the role of feelings and context40

Overlook transformation through the unconscious development of thoughts and actions, while ignoring the role of long-term and implicit memory, which shapes present behavior and attitudes40 Presents a gap between engaging in critical reflection and revising a perspective, which is “the desire to change”41 Did not clarify the factors that enhance revisions of perspectives, and if they relate to the individual, or the individual’s life, the confusing issue, or the particular perspective41 |

| Pharmacy education: the adoption and integration of transformative and critical reflection teaching and learning strategies into pharmacy education, allows pharmacy students to acquire self-reflective and metacognitive skills, to provide tailored care for their patients, and to adapt to changing healthcare systems5 | Undergraduate Graduate |

||||

| 4. Social theories of learning: focus on context and community | 4.1. Zone of proximal development | Vygotsky (1978)42 | Medical education: through social theories of learning, trainee physicians learn to perform particular responsibilities in a specific manner during their practical training, by observing the behaviors and performance modeled by their preceptors, and then adopting them27,35 | Undergraduate Graduate |

Ignorance of the mental or emotional state of learners, and their differences due to genetic, brain, and learning abilities43

Do not account for the biological, neurophysiological, cultural, linguistic, and historical factors that shape a learner’s experiences43 |

| 4.2. Situated cognition | Lave and Wenger (1991)44 | ||||

| 4.3. Communities of practice (CoP) | Wenger (1998)23 | Healthcare professional education: the use of CoP theory has been explored in medical education,45 occupational therapy and physiotherapy education,46 nursing education,47 pharmacy education,48,49 and surgical medical education50 | Undergraduate Graduate CPD |

||

| 5. Motivational models | 5.1. Self-determination theory | Ryan and Deci (2000)51 | Medical education: motivational learning theories were not generally considered as drivers of curricular planning in medical schools. However, while implementing other educational strategies, student motivation was an implicit outcome. Intrinsic motivation is enhanced by meeting students’ needs, by facilitating positive relationships, and by providing students with constructive feedback52

Pharmacy education: limited literature discussed the motivations of pharmacy students and their connection with students’ academic performance or the learning environment53 |

Undergraduate Graduate |

Focus on extrinsic motivation, driven by the concept of “assessments drive learning” (Miller, 1990). In reality, assessments should be used as tools for providing feedback on performance to enhance students learning52 |

| 5.2. Expectancy valence theory | Weiner (1992)54 | ||||

| 5.3. Chain of response model | Cross (1981)55 | ||||

| 6. Reflective models | 6.1. Reflection-on-action | Schön (1987)56 | Healthcare professional education: reflective learning models are important because they encourage the development of reflective practice and learning systems, which develop a learner’s knowledge and skills57 | Undergraduate Graduate CPD |

Lack of elaboration on the psychological realities of reflection in action, failure to fully distinguish between reflection in and on action, failure to clarify what is involved in the reflective process and also failure to account for the significance of the time dimension in relation to decisions taken after the undergoing the reflective process58 |

| 6.2. Reflection-in-action | Schön (1987)56 | Medical education: structured reflection has shown its effectiveness as an instructional method to enhance students’ competence, and learning of clinical practice59 | CPD | ||

| Pharmacy education: the application of reflective theories of learning in a second-year undergraduate pharmacy curriculum allowed the integration of theory and practice, enhanced the critical thinking, problem-solving, and self-directed learning of students. The reflective models in pharmacy need to be evaluated as students progress from the classroom into the practice settings9 | Undergraduate | ||||

| 7. Constructivism | 7.1. Cognitive constructivists | Ausubel and Robinson (1969)60 and Piaget and Cook (1952)25 | Healthcare professional education: constructivist approaches to learning, combined with Kolb’s model are the foundation of the experiential learning model.61 These approaches emphasized learning by action and is outcome based62

Medical education: the constructivist learning theory has guided medical education strategies, such as group discussions, journal clubs, course portfolio development, and critical appraisal. The application of Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (ZPD) concept is represented by a teacher’s demonstration of tasks, followed by the scaffolding of a learner’s independent practice of that task27,35 Pharmacy education: pharmacy educators should prepare students to construct their own knowledge, and apply taught concepts in real situations through knowledge recontextualization61 |

Undergraduate Graduate CPD |

Tends toward epistemological relativism, which considers that absolute truth does not exist, and that it exists in relation to cultural, societal, or contextual aspects63

The quasi-religious or ideological aspect of constructivism, which results from its objective to be the human epistemology of “truth” and knowing63 Ignorance of the importance of passive learning, memorizing, and other traditional strategies63 Separates the human mind from the external world by over emphasizing the role of learning environment63 |

| 7.2. Socio-cultural constructivism | Vygotsky (1978)42 |

To ensure comprehensiveness of the search, the references cited within selected articles were manually searched, and their authors were contacted, to gather further recommendations regarding relevant literature. Also, alerts for new articles were requested from the databases, to ensure that most up-to-date references were included.

Relevant articles were identified, compiled, synthesized, and then illustrated in Table 1. The literature review was not performed as a systematic review, because the goal was to summarize learning theories used in healthcare professional education and present them in a user-friendly format. Data about learning theories categorization, their definition, limitations, and application in healthcare professional education were extracted from the selected articles and are summarized in Table 1.

In this article, the classification of Taylor and Hamdy7 was adopted, because their work presents a contemporary review of the literature about key learning theories, which has been widely cited in other studies. Furthermore, their work is based on a medical education setting, which enhances its applicability for other healthcare professional education. In this article, the work of Taylor and Hamdy7 is expanded and developed to include constructivism learning theory, because constructivism learning theory has been identified and categorized in other literature as a distinctive category.27 Examples of the application of each learning theory in healthcare professional education and a critical evaluation on each theory, as derived from previous literature, are presented in the “Results” section in a narrative and table format.

Results

Adult learning theories have been divided in the literature into the following categories: instrumental, humanistic, transformative, social, motivational, reflective, and constructivist learning theories. The theories are outlined in the following text and then presented in table format with examples from practice and links to the relevant literature. These learning theories are derived from psychological theories of learning, and their categorization is influenced by the broad constructivist views of andragogy, indicating that learning is the process of constructing new knowledge on the foundations of existing knowledge. These constructivist views explain the overlapping principles among some of these theories, so they appear as logically expanded and developed from each other.6

Instrumental learning theories

Instrumental learning theories include behavioral theories, cognitivism, and experiential learning.

Behavioral theories

Focus on a stimulus in the environment leading to an individual’s change of behavior, one consequence of which is learning. Positive consequences, or reinforcers, strengthen behavior and ultimately enhance learning, while negative consequences, or punishers, weaken it.7 Within the behaviorist paradigm, educators are responsible for controlling the learning environment, to achieve a specific response, which represents a teacher-centered approach to teaching.35

Cognitivism

Focuses on the learner’s internal environment and cognitive structures, rather than the context or external environment35. Cognitive learning theories are associated with mental and psycho- logical processes to facilitate learning by assigning meaning to events such as insight, information processing, perceptions, reflection, metacognition, and memory. This implies that learning primarily takes place in formal education through verbal or written instructions or demonstrations and includes an accumulation of knowledge that is explicit and identifiable.64

Experiential learning

Learning and knowledge construction are facilitated through interaction with the authentic environment.64 Kolb31 believed that learning and knowledge construction are facilitated through experience and described the learning cycle as having four phases: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle allows apprehension, comprehension, intention, and extension.10

Humanistic theories or facilitative learning theories (self-directed learning)

Humanism is a paradigm that emerged in the 1960s and focuses on human freedom and dignity to achieve full potential. They suggest that learning is self-directed, and that adults can plan, manage, and assess their own learning to accomplish self-actualization, self-fulfillment, self-motivation values, goals, and independence in their learning. Hence, learning can be student-centered and personalized and educators are facilitators of learning.7

Transformative learning theories (reflective learning)

Focus on transformation of meaning, context, and long-standing propositions. Learners are empowered to identify and challenge the validity of their embedded assumptions, referred to by Mezirow as “frames of reference.”5 Learning occurs when new knowledge becomes integrated into existing knowledge, and learners maintain their original “frame of reference,” but continue to challenge and change some of their perspectives “meaning schemes.”65 Transformative learning involves three stages, the first stage involves experiencing a confusing issue or problem and reflecting on previous perspectives about the event. The second is engaging in critical evaluation and self-reflection on the experience, which requires metacognitive thinking. The third stage is taking an action about the issue, based on self-reflection and previous assumptions, which leads to a transformation of meaning, context, and long-standing propositions.

Social theories of learning (zone of proximal development, situated cognition, communities of practice)

Social learning theories integrate the concept of behavior modeling with those of cognitive learning, so that the understanding of the performance of a task is strengthened. Social learning theories focus on social interaction, the person, context, community, and the desired behavior, as the main facilitators of learning. The fundamental components of social learning theories are observation and modeling, in which teachers are responsible for providing a supporting learning environment, and clarifying the expected behaviors.7,27,35

Motivational model (self-determination theory, expectancy valence theory, chain of response model)

Imply that adult learning is associated with two fundamental elements: motivation and reflection. Examples of motivational theories are self-determination theory,51 which focuses on intrinsic motivation; the expectancy valence theory,54 which incorporates the expectancy of success; and the chain of response model,55 which focuses on three internal motivating factors: self-evaluation, the attitude of the learner toward education, and the importance of goals and expectations.

Reflective models (reflection on action and reflection in action)

Schön56 suggested that there are two types of reflection: reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action. While reflection-on-action allows learners to evaluate the level of relevance or rigor of the processes after they happen, reflection-in-action allows learners to reflect while the activity is happening.66 This leads the learners to test their own knowledge, through investigation.7 Reflection helps students make meaning of complex situations and enables them to learn from experience in authentic practice. Reflective learning varies according to a student’s ability to reflect on their experiences, clinical problems, and the context of practice. A student’s reflective thinking and practice can develop over time with a supportive learning environment and encouraging educators. Learners need a structured guide for reflection, as well as constructive feedback about their reflections, from their educators.57

It is important to note that there are similarities between Mezirow’s37–39 critical reflection model, explained above under transformative learning theories, and Schön’s56 models of reflection on action in that they both reflect on old assumptions and knowledge, which then require action to change. Although the terms “reflection” and “critical reflection” are used interchangeably in the literature, not all reflection is critical. Critical reflection engages higher and more challenging levels of thought, and thus becomes an originator of transformative learning for both learners and educators, by connecting old and new knowledge to examine learning conditions more holistically.67

Constructivism (cognitive constructivists and socio-cultural constructivism)

Constructivism is an epistemology and a psychological theory of learning that explains knowledge and the meaning making processes. Ausubel and Robinson60 and Piaget and Cook25 are the main scholars among the cognitive constructivists, and Vygotsky42 was the first scholar in socio-cultural constructivism, a social theory of learning which emphasized the broader socio-historical and situated dimension of learning and development. According to constructivism, individuals construct new knowledge through the interaction between their previous skills and knowledge, the skills and knowledge gained from social interaction with peers and teachers, and social activities. Knowledge is actively constructed based on a learner’s environment, the physical and social world, which makes it relative.68 The constructivist theory approaches pedagogy and learning holistically, focusing comprehensively on the internal cognitive mechanisms that underlie the learning processes, participation, and social interaction.69

In Table 1, the originator of the theory, examples about the application of the theory in healthcare professional education (undergraduate, graduate, or CPD context), and a brief critical comment about the theory are provided.6 This literature synthesis provides an easy to use summary of key theories, which helps healthcare professional educators to have informed decisions of their instructional strategies, learning objectives, and evaluation approaches. This will subsequently result in student experiences improvement.

In Table 1, a special emphasis is placed on the application of the theory in healthcare professional education.6 For example, within the instrumental learning theories, frameworks that measure clinical performance and competence are originally derived from the behavioral theories,24 while concept maps are derived from the cognitivism.27 Within the humanistic learning theories, CPD programs are applications of self-directed learning.4,14 Reflective learning theories has shown its effectiveness in enhancing students’ competence, and learning of clinical practice,59 and constructivist learning theory has guided medical education strategies, such as group discussions, course portfolio development, and critical appraisal.27,35

Discussion

Healthcare professional educators including, but not limited to, those teaching in pharmacy, medical, nursing, dental schools/colleges are not essentially trained as educators. Burton et al49 explained that most pharmacy educators were originally trained as pharmacists, not as teachers or educators, with the majority not receiving any formal training about teaching and learning processes and fundamental educational concepts, such as learning theories. While they demonstrate proficiency in their professional roles, their teaching skills have been largely developed by experience, rather than through formal training and research. Furthermore, McAllister et al70 argue that it is important to support novice nurse educators during their transition from the clinical role into the educator role. This support could be achieved through exchanging expertise and resources with experienced nurse educators, which reduces their sense of isolation, and by conducting professional development activities, which aim to help educators meet the expected challenges. Exchanging expertise and professional development activities enhance the satisfaction of nurse educators, which results in positive learning experiences for students.

Healthcare professional educators should ideally be familiar with a range of learning theories to use the most appropriate approach for the teaching they deliver, based on the educational setting, context, learners’ characteristics, the purpose of the teaching, potential for use, and integration of existing resources.1 The significance of theoretical considerations in professional healthcare professional education was stressed by Benner et al15 who argued that theoretical knowledge is formed by practice and consequently influences practice. Unfortunately, important learning theories are not consistently implemented in the educational designs and practices of healthcare professional education programs. The reasons for this lack of consideration and implementation seem to vary between different countries and have potentially led to variable outcomes. For example, in the United Kingdom, one of the reasons for this lack of implementation is the structural arrangement of the National Health Service (NHS) and higher education organizations and their independent roles, which keep service and education providers disconnected.71 This functional disconnection in the UK health and educational services has resulted in theory, practice, and research disconnects.71 In other countries, such as Canada, the lack of discussion of educational theory, and giving it adequate consideration in pharmacy program design and pedagogical practices, has led to accreditation bodies dictating the educational agenda, and the extent to which theory appears in these accreditation standards is variable.72 This dictation of the educational agenda by accreditation bodies could also be the case in other countries, such as United Kingdom.73

In a systematic review conducted in 2015 to analyze the knowledge produced about teaching in higher education in nursing, the need to include pedagogical aspects in the training of nursing teachers was evident. This includes understanding and skillfully transitioning between the specialty and pedagogy and deepening the knowledge about the pedagogical practices.74 In another scoping review for studies conducted in the health science disciplines, including but not limited to medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, pharmacy and dentistry, clinician teachers indicated that they have no adequate educational background. They indicated their need to attend faculty development workshops that help them to identify the most common theories of learning and teaching used in graduate and graduate teaching, and the application of teaching methods.11

Gonczi75 argued that preceptors in undergraduate healthcare professional and medical education struggle to fully support their students because they were not developed as educators, yet are responsible for student learning at the practice sites. He noted that their responsibility for the student learning could become problematic if it is not associated with collaboration between the universities and the practice sites. Gonczi75 called for a university-practice site partnership to enhance student learning and preceptor development as educators and to build up the strong organizational capacity of academics and practitioners to better serve students and practitioners learning about teaching pedagogies and learning theories. In addition, Moss et al12 suggest advancing the understanding of the pedagogy of graduate programs in healthcare professional education. These investigators suggested that this can be achieved by conducting more research into the influence of pedagogy on the main components of curriculum design: content (concepts), delivery, and assessment. It is also important that educators explicitly explain the benefits of implementing graduate pedagogies in healthcare professional education programs, such as enhancing practice, and encouraging professional development.12

Conclusions

In this article, a quick and easy-to-use summary of adult learning theories categorization is provided, indicating the potential application of each theory in healthcare professional education, and highlighting the importance of connecting educational practices to learning theories. Educators in healthcare professions should consider the nature of healthcare knowledge and the philosophical perspectives that underpin healthcare professional education, to augment more commonly adopted pragmatic perspectives. This thinking will help educators to subsequently restructure curricula, instructional strategies, learning objectives, and evaluation approaches, by giving more theoretical consideration to the healthcare professional education, which will ultimately enhance student learning experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding agency: Qatar University. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr Ahmed Awaisu, Associate Professor, College of Pharmacy, Qatar University for providing his useful feedback about this quick guide for healthcare profes- sional educators about adult learning theories. This article is part of the PhD research of Banan. The PhD degree was awarded from the University of Bath, Bath, UK. The PhD was sponsored by Qatar University.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article is part of the PhD research of the corresponding author. The PhD was sponsored by Qatar University

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: AT is a PhD supervisor and contributed to conception of the work, revision of intellectual content, final approval of this version, and confirmation of integrity of the work.

ORCID iD: Banan Abdulrzaq Mukhalalati  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0049-8879

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0049-8879

References

- 1. Aliakbari F, Parvin N, Heidari M, Haghani F. Learning theories application in nursing education. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zittleman K, Sadker DM. Teachers, Schools, and Society: A Brief Introduction to Education. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kapp A. Platon’s Erziehungslehre, Als Pädagogik Für Die Einzelnen Als Staatspädagogik. Ober Dessen Praktische Philosophie. Minden, Germany: Verlag von Ferdinand Essmann; 1833. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knowles M. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lonie JM, Desai KR. Using transformative learning theory to develop metacognitive and self-reflective skills in pharmacy students: a primer for pharmacy educators. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7:669–675. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mukhalalati B. Examining the disconnect between learning theories and educational practices in the PharmD programme at Qatar University: a case study. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/84915028.pdf. Up-dated 2016.

- 7. Taylor DCM, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35:e1561–e1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wallman A. Pharmacy Internship: Students’ Learning in a Professional Practice Setting [dissertation]. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsingos-Lucas C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Schneider CR, Smith L. The effect of reflective activities on reflective thinking ability in an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34:e102–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McInerney PA, Green-Thompson LP. Teaching and learning theories, and teaching methods used in postgraduate education in the health sciences: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15:899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moss C, Grealish L, Lake S. Valuing the gap: a dialectic between theory and practice in graduate nursing education from a constructive educational approach. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30:327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson N, Davies D. Continuing professional development. In: Carter Y, ed. Medical Education and Training. From Theory to Delivery. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rouse MJ. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:517–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benner PE, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Expertise in Nursing Practice: Caring, Clinical Judgment, and Ethics. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mulder M, Roelofs EA. Critical review of vocational education training research suggestions for the research agenda. https://www.mmulder.nl/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/2012-Mulder-Roelofs-Critical-Review-of-VET-Research-and-Research-Agenda.pdf

- 17. Waterfield J. Two approaches to vocational education and training. A view from pharmacy education. J Voc Educ Train. 2011;63:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Waterfield J. Using Bourdieu’s theoretical framework to examine how the pharmacy educator views pharmacy knowledge. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79: 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thorndike EL. Animal Intelligence: Experimental Studies. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pavlov IP. Conditioned Reflexes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Skinner BF. The Science of Learning and the Art of Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Skinner BF; 1954:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kay D, Kibble J. Learning theories 101: application to everyday teaching and scholarship. Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wright D, Morgan L. An Independent Evaluation of Frameworks for Professional Development in Pharmacy. Norwich, UK: University of East Anglia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piaget J, Cook M. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. Vol. 8 New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruner JS. Toward a Theory of Instruction. Vol. 59 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arab M, Ghavami B, Lakeh MA, Esmaeilpoor S, Yaghmaie M, Hosseini-Zijoud S-M. Learning theory: narrative review. Int J Med Rev. 2015;2:291–295. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Handley K, Sturdy A, Fincham R, Clark T. Within and beyond communities of practice: making sense of learning through participation, identity and practice. J Manage Stud. 2006;43:641–653. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Noble C, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Coombes I. Curriculum for uncertainty: certainty may not be the answer. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:13a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutherford-Hemming T. Simulation methodology in nursing education and adult learning theory. Adult Learn. 2012;23:129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kolb D. Experiential Learning as the Science of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsingos C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith L. Learning styles and approaches: can reflective strategies encourage deep learning? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015;7:492–504. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rogers CR. Toward a science of the person. J Human Psychol. 1963;3:72–92. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maslow A. Some educational implications of the humanistic psychologies. Harv Educ Rev. 1968;38:685–696. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Torre DM, Daley BJ, Sebastian JL, Elnicki DM. Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. Am J Med. 2006;119:903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Merriam SB. Andragogy and self-directed learning: pillars of adult learning theory. New Direc Adult Cont Educ. 2001;2001:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mezirow J. Perspective transformation. Adult Educ. 1978;28:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mezirow J. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. In: Mezirow J, ed. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mezirow J. Transformative learning: theory to practice. New Direc Adult Cont Educ. 1997;1997:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor EW. Transformative learning theory: a neurobiological perspective of the role of emotions and unconscious ways of knowing. Int J Lifelong Educ. 2001;20:218–236. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor EW, Cranton P. A theory in progress? issues in transformative learning theory. European J Res Educ Learn Adults. 2013;4:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vygotsky L. Interaction between learning and development. Readings Develop Child. 1978;23:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sammons A. The social learning approach: the basics. http://www.psychlotron.org.uk. Up-dated 2015.

- 44. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bates J, Konkin J, Suddards C, Dobson S, Pratt D. Student perceptions of assessment and feedback in longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 2013;47:362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roberts GI. Communities of practice: exploring enablers and barriers with school health clinicians: explorer les facteurs favorables et défavorables à la participation aux communautés de pratique avec des cliniciens de la santé en milieu scolaire. Canadian J Occup Ther. 2015;82:294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roberts J. Limits to communities of practice. J Manage Stud. 2006;43:623–639. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Austin Z, Duncan-Hewitt W. Faculty, student, and practitioner development within a community of practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:55. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burton S, Boschmans S-A, Hoelson C. Self-perceived professional identity of pharmacy educators in South Africa. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaye C, Egan T, Smith-Han K. Communities of clinical practice and normalising technologies of self: learning to fit in on the surgical ward. Anthropol Med. 2010;17:59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kusurkar RA, Croiset G, Mann KV, Custers E, ten Cate O. Have motivation theories guided the development and reform of medical education curricula? a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2012;87:735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alrakaf S, Anderson C, Coulman SA, et al. An international comparison study of pharmacy students’ achievement goals and their relationship to assessment type and scores. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiner B. Human Motivation: Metaphors, Theories, and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cross KP. Adults as Learners: Increasing Participation and Facilitating Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schön DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2009;14:595–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schön D, Donald A . The reflective practitioner: In: How professionals think in action. Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mamede S, van Gog T, Moura AS, et al. Reflection as a strategy to foster medical students’ acquisition of diagnostic competence. Med Educ. 2012;46:464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ausubel DP, Robinson FG. School Learning: An Introduction to Educational Psychology. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Botma Y, Van Rensburg GH, Coetzee IM, Heyns T. A conceptual framework for educational design at modular level to promote transfer of learning. Innov Educ Teach Int. 2015;52:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu CH, Matthews R. Vygotsky’s philosophy: constructivism and its criticisms examined. Int Educ J. 2005;6:386–399. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Abdulwahed M. Towards enhancing laboratory education by the development and evaluation of the “TriLab”: a triple access mode (virtual, hands-on and remote) laboratory. https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/handle/2134/6355. Up-dated 2010.

- 65. Taylor EW. An update of transformative learning theory: a critical review of the empirical research (1999–2005). Int J Lifelong Educ. 2007;26:173–191. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thomas LB. Reflecting on practice: an exploration of the impact of targeted professional development on teacher action. https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3310494/. Up-dated 2008.

- 67. Lucas P. Critical reflection. What do we really mean? Paper presented at the 2012 Australian Collaborative Education Network National Conference; October 29-November 2, 2012; Perth, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kang LO, Brian S, Ricca B. Constructivism in pharmacy school. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2010;2:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ultanir E. An epistemological glance at the constructivist approach: constructivist learning in Dewey, Piaget, and Montessori. Int J Instruct. 2012;5:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 70. McAllister M, Oprescu F, Jones C. N2E: envisioning a process to support transition from nurse to educator. Contemporary Nurse. 2014;46:242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Allan HT, Smith P. Are pedagogies used in nurse education research evident in practice? Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30:476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Austin Z, Ensom MH. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Husband AK, Todd A, Fulton J. Integrating science and practice in pharmacy curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lazzari DD, Martini JG, Busana JDA. Teaching in higher education in nursing: an integrative literature review. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2015;36:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gonczi A. Competency-based approaches: linking theory and practice in professional education with particular reference to health education. Educ Philos Theor. 2013;45:1290–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine. 1990; 65:63–67.2302301 [Google Scholar]

- 77. Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013. Advanced Pharmacy Framework (APF)[Online]. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPS) http://www.rpharms.com/faculty-documents/rps-advanced-pharmacy-framework-guide.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2014. Foundation Pharmacy Framework (FPF)[Online]. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPS) https://www.rpharms.com/development-files/foundation-pharmacy-framework—final.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]