Abstract

Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing is considered as a key to improve access to medicines especially for developing countries. The aim of this scoping review is to determine the most important components affecting pharmaceutical strategic purchasing. Here, we employed a comprehensive search strategy across PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCO, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar for the terms related to medicines strategic purchasing. Among 13 included studies, 7 (53.85%) and 6 (46.15%) studies belonged to the developing and developed countries, respectively. Six main variables were emphasized as the effective variables on medicines strategic purchasing, including purchasing interventions, target group and service users, providers and suppliers of interventions, methods and motivations, price, and finally structure and organization. It seems that the insurance organizations of developing countries can achieve strategic purchasing only through the modification of the pharmaceutical pricing system and payment systems. Furthermore, they should pay attention to the real needs of target groups (demand) and modify the structure and organization as well as purchasing the most effective medicines from the best pharmaceutical providers.

Keywords: Medicines, pharmaceutical, resource allocation, strategic purchasing

Introduction

Medicine is considered to be an imperative part of health systems and seen as an important bridge between patients and health care professionals.1 In addition, pharmaceuticals are a significant part of health expenditures in the developing countries.2 The main concerns of practitioners and policy makers in the health care system are efficient supply and distribution of essential medicines and reliable coverage of insurance agencies, as the main purchasers and recourse allocation agencies. According to the international organizations such as the World Bank and the World Health Organization, the possible way to overcome such concerns is the strategic purchase of pharmaceuticals.3

Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing is to provide the most cost-effective medicines for the neediest people through the best supplier and with the most reasonable price and payment structure.4 For this purpose, all structures of purchasing and resource allocation should ensure the access of pharmaceutical consumers.

As poor and vulnerable groups of people face many challenges and obstacles on the way to achieve the essential medicines, policies such as pharmaceutical subsidies for the target population and the legal use of medicines can be useful to combat the challenges.5

In addition, the realization of the medicines strategic purchasing requires explaining the appropriate indicators to select the most desirable and highest quality medicines. Also, effective contracting with pharmaceutical suppliers provides the most appropriate, effective, and highest quality medicines for the target population on the right time and without delay.6

Besides the foregoing, medicines strategic purchasing requires insurance organizations to provide and reimburse pharmaceuticals with a suitable, logical, realistic, and affordable price.3 Furthermore, to increase the purchasing functionality, they should be able to use competitive advantages and bargaining ability to agree on the lowest acceptable price.7

Finally, financial incentives, regulatory measures such as design and choosing the best methods of payment or penalties for noncompliance, determining the most important area of intervention, and modification of the cash flow process are of the issues which should be noted on the medicines strategic purchasing.6 For example, in some organizations, patients pay the entire cost of purchased pharmaceuticals to the pharmacies at first and then the resource allocating and purchaser organization will seek repayment of all or a proportion (eg, India), while in other cases the organizations pay directly to the provider (eg, Tanzania). Obviously, the second pattern is more consistent with the principles of strategic purchasing and also can increase the access to medicines especially among the poor people.8

In addition, various studies show that the pharmaceutical strategic purchasing is one of the key policy tools to achieve the goals of universal health coverage, promotes the equitable access, increases financial protection, enforces the competitive markets, increases the purchasing power of health services buyers, etc.9,10 Accordingly, in many countries especially in developing ones with a more resource shortage, strategic purchasing has been emphasized as a key to increase access to medicines.4

Considering the importance of establishing strategic purchasing in the developing countries’ health system, the present study aimed to determine the most important effective factors on pharmaceutical strategic purchasing through a scoping review of studies between 2000 and 2018 to help policy makers and health care system decision makers to establish a clear way in pharmaceutical strategic purchasing.

Materials and Methods

The Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review method was followed as a framework.11 A comprehensive systematic scoping review was performed to explain the effective components of medicines strategic purchasing in the world. In the first stage of this review, the research question was identified based on the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) elements. This particular question includes all the health systems which use any kinds of pharmaceutical purchasing methods (Population), components and factors that affect pharmaceutical strategic purchasing and lead to this method of purchasing as a final outcome in a health system (Concept), and all health systems which use pharmaceutical strategic purchasing (Context).

In the stage of searching for relevant studies (second stage), the target population was all studies related to resource allocation, purchasing, and medicines strategic purchasing in the health sector in different countries of the world. For this purpose, all related studies regarding from 2000 (the publication year of the World Health Report about the use of strategic purchase) were retrieved through the exact research strategy (Table 1).

Table 1.

The search strategy of the research.

| Search strategy | |

|---|---|

|

Search engines and databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCO, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect (2000-2018) | |

| Limits: Language (only resources with at least an abstract in English) | |

| Date: up to April 20, 2018 | |

| Strategy: #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| #1 | “Resource allocation” OR “Resource allocating” OR Strategic |

| #2 | Purchas* |

| #3 | Pharmaceutical OR Pharmaceuticals OR Medicine OR Medicines OR Drug OR Drugs |

So, the original keyword content appropriate to the purpose of the research was selected in English at first based on the comments of the research team and the used keywords in available researches in this field and then above databases were searched.

It was decided that all articles with at least English abstract indexed in 1 of the above-mentioned databases were identified. It should be noted, as it is not possible to filter the search results just by the abstracts or titles in the Google Scholar, in addition for minimizing the search biases, manual search through the results was conducted, so most of the Google Scholar search results did not meet the search criteria.12

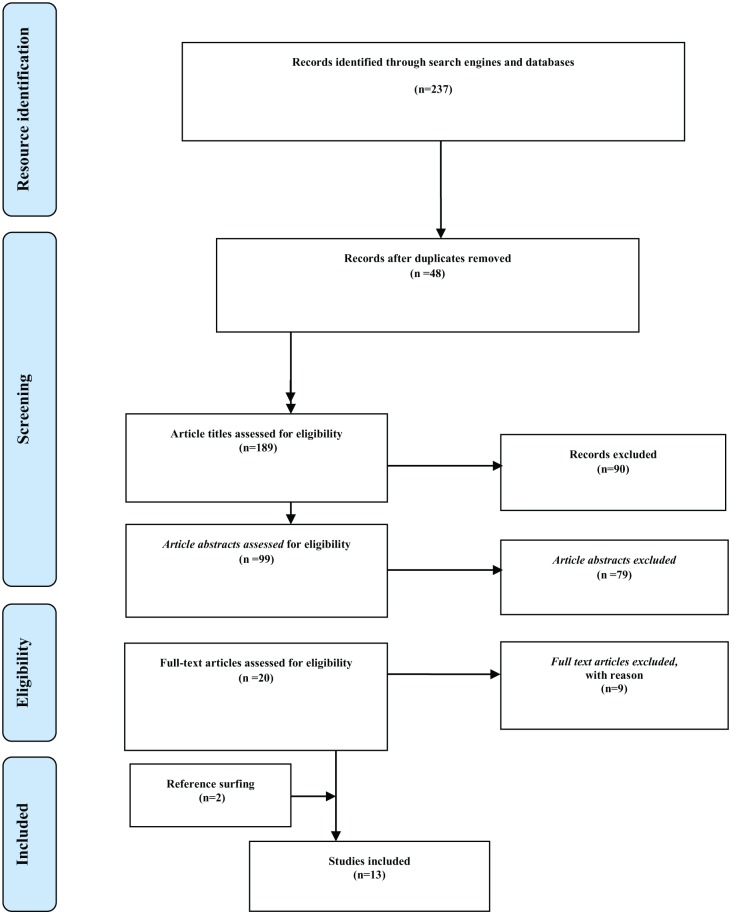

In stage 3, the selection of relevant studies was carried out (Figure 1). It is necessary to mention that all of the research processes and selection of papers were conducted by 2 researchers independently and third researcher was used to reach consensus if necessary. Meanwhile, the protocols, review studies, and studies regarding the strategic purchase of cases except medications were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the scoping review process.

Finally, the quality of final selected articles were evaluated by Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool, as a guide it effectively covers the essential areas for critical appraisal of articles,13 and then all papers were confirmed by the research team.

In stage 4, the data-charting form was used to extract data from each study (Appendix 1). Then, the collected data were collated and classified according to the thematic analysis in the last stage.

Results

The findings resulted from the analysis of 13 investigated studies were summarized in Table 2. Among these studies, 7 (53.85%) and 6 (46.15%) studies belonged to the developing and developed countries, respectively. Furthermore, 11 out of 13 retrieved documents were presented through qualitative or review methods, and 1 study conducted in a quantitative design and 1 in a format of mixed method study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected studies on pharmaceutical strategic purchasing.

| Author(s) | Title | Time | Place | Study aim | Study type | Study tools | Study samples | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawson et al14 | Strategic purchasing, supply management practices and buyer performance improvement: an empirical study of UK manufacturing organisations | 2009 | The United Kingdom | Examine the effect of strategic purchasing on the supply management practices of socialization, supplier integration, and supplier responsiveness, together with relationship performance | An Internet-based survey | A web-based questionnaire | 111 UK manufacturing firms | Long-term supplier relationships can lead to the creation of relational rents. Suggestions for the strategic purchasing research are made |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Spending wisely: buying health services for the poor | 2005 | World Bank | Presenting a conceptual framework for pharmaceutical purchasing in developing countries | Comprehensive study | Data collection forms | Reports and indexes related to pharmaceutical systems in developing countries | Demand side and supply side interventions, price, and incentives as pharmaceutical strategic purchasing factors |

| Haupt15 | Vertical integration and strategic sourcing in the biopharmaceutical industry | 2005 | The United States | Presenting a conceptual framework for pharmaceutical purchasing in developed countries | Comprehensive study and document analysis | Data collection forms | Reports and indexes related to pharmaceutical systems in developed countries | Cost-effectiveness, accurate amount, selecting the best supplier, on-time delivery system, real price, operational costs, etc. |

| Kirytopoulos et al16 | Supplier selection in pharmaceutical industry: an analytic network process approach | 2008 | Greece | A comprehensive method for selection of the best pharmaceutical supplier | Comprehensive study and network analysis | Flowchart and ranking matrix | Related documents and expert’s judgment | Presenting the most important inputs and best selection of pharmaceutical suppliers |

| Sermet et al17 | Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France | 2010 | France | Comparing the undergoing pharmaceutical reforms in France | Stakeholder analysis and trend study | Data collection forms and topic guides | Related documents and pharmaceutical experts | Cost saving on medicines, existence of basic benefit package, and pharmaceutical strategic purchasing for the effectiveness of the reforms |

| Pazirandeh18 | Sourcing in global health supply chains for developing countries: literature review and a decision making framework | 2011 | Sweden | Presenting a decision-making framework for vaccine procurement | Exploratory analysis via a comprehensive review | Data extraction form | All the related journals | Quality of vaccines, logistics, price, and product characteristics as the main variables |

| Arney et al19 | Strategic contracting practices to improve procurement of health commodities | 2014 | The United States | This study offers an overview of Department of Veterans Affair (VA and Department of Defense (DOD) procurement and contracting practices and focuses on 1 strategic procurement and contracting practice that developing countries may benefit from adopting—framework agreements | Literature review protocol | Semi-structured literature reviews and interviews | Key characteristics of these strategic practices as well as case studies of their use by other national governments and multilateral agencies are reviewed | Enabling legislation and strengthened technical capacity to develop and manage long-term contracts could facilitate the use of framework contracts in sub-Saharan Africa, with improved supply security and cost savings. |

| Bastani et al1 | Resource allocation and purchasing arrangements to improve accessibility of medicines: evidence from Iran | 2015 | Iran | Customizing the World Bank model for pharmaceutical strategic purchasing | Qualitative document analysis | Topic guide | 20 national experts | Recognizing 3 elements of demand side interventions, supply side interventions, price, and incentives |

| Mehralian and Bastani4 | Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing: a key to improve access to medicines | 2015 | Iran | Description of strategic purchasing model as a key to increase access | Editorial | Library data | Related texts | Emphasizing on 5 elements of what to buy, for whom we buy, from whom we buy, in which price and incentives |

| Bastani et al3 | Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing requirements in Iran: price interventions and the related effective factors | 2016 | Iran | Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing implementation (price) requirements in Iran | Qualitative study (framework analysis) | Topic guide | 32 experts in pharmaceutical and insurance scopes | Diagnosing 4 categories of variables: structural, legal, economical, and international |

| Bastani et al6 | Requirements and incentives for implementation of pharmaceutical strategic purchasing in Iranian health system: a qualitative study | 2016 | Iran | Requirements and incentives for implementing pharmaceutical strategic purchasing in Iran | Qualitative study (framework analysis) | Topic guide | 32 experts in pharmaceutical and insurance scopes | Three main themes—“Payment Mechanisms to Service Providers,” “Insurance Reimbursement Mechanisms,” and “Rules and Regulations”—were identified |

| Ogbuabor and Onwujekwe20 | Scaling-up strategic purchasing: analysis of health system governance imperatives for strategic purchasing in a free maternal and child healthcare programme in Enugu State, Nigeria | 2018 | Nigeria | The study provides evidence of the governance requirements to scale up strategic purchasing in free health care policies in Nigeria and other low-resource settings facing similar approaches | Qualitative study | Pre-tested, in-depth, semi-structured interview guide | 44 participants of government officials and health facility staff as gatekeepers | The key findings show that supportive governance practices in purchasing included systems to verify questionable provider claims, pay providers directly for services, compel providers to procure medicines centrally, and track transfer of funds to providers |

| Patcharanarumol et al21 | Strategic purchasing and health system efficiency: a comparison of 2 financing schemes in Thailand | 2018 | Thailand | Comparing the strategic purchasing practices of Thailand’s 2 tax-financed health insurance schemes, the Universal Coverage Scheme, and the Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme by analyzing the relationships between the purchaser and government, providers, and members | A mixed method research | Secondary data were collected from Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) and Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS), and interview topic guides for qualitative phase | The qualitative methods involved review of key documents and in-depth interviews and small group discussion with key informants | The governance of the purchaser organization, the design of the purchasing arrangements including incentives and use of information, and the institutional capacities to implement purchasing functions are essential for effective strategic purchasing which can improve health system efficiency as a whole |

As it mentioned in Table 2, most of the qualitative studies used data collection forms and topic guides, both were 4 out of 11 (36.36%) similarly.

Other findings showed that 6 main variables were emphasized as the effective variables on strategic purchase of medicines, including purchased interventions, target group and service users, providers and suppliers of interventions, methods and motivations, price, and structure and organization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Components affecting pharmaceutical strategic purchasing.

| Main components | Subcomponents | References | Reference evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purchased interventions | Procurement of the most cost-effective medicines | Bastani et al1 | Reimbursing new medicines by insurance based on cost-effectiveness studies as well as budget impact analysis |

| Mehralian and Bastani4 | Regarding cost-effectiveness, safety, quality, and price, which medicine should be bought? | ||

| Pharmaceutical strategic selection on behalf of the poor | Mehralian and Bastani4 | Specifying the groups that have a greater need for medicines | |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Many factors influence whether poor people can obtain affordable essential medicines of standard quality | ||

| Target groups and users of services (demand side) | Subsidiary for the selected groups | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Government or donor agencies provide subsidies for health services, including pharmaceuticals |

| Bastani et al1 | Correction of medicine subsidy mechanism for patients with special disease | ||

| Rational use of medicines | Bastani et al1 | Promoting strategies to encourage rational use and prescription of medicines | |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Promoting rational medicine use | ||

| Pazirandeh18 | Considerable prescribing freedom and choice of physician among patients—quality and efficiency of prescribing include programs to enhance generic prescribing and dispensing to reduce antibacterial and anxiolytic/hypnotic | ||

| Providers and suppliers of interventions (supply side) | Selecting the most reliable supplier | Kirytopoulos et al16 | A qualified and reliable supplier is a key element in reducing material costs and achieving on-time deliveries; supplier selection is increasingly recognized as a critical decision in supply chain management |

| Gilson et al22 | This requires a strategic segmentation of the selected suppliers, setting the level of relationship in need for each supplier group and identifying the required criteria in need of development | ||

| Selecting the best supplier in the public or private sector | Kirytopoulos et al16 | A basis for evaluation of potential and existing suppliers, provides a unified procedure for all companies to fully exploit the results within a supply chain, deepens the knowledge about each supplier, and acts as an improvement tool for suppliers | |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | The private sector is the main player in the pharmaceutical sector of developing countries. The private sector has the largest number of manufacturers, wholesalers, and community pharmacies, and the value of private medicine sales is larger than the public | ||

| Active competition between suppliers on quality, price, and delivery | Kirytopoulos et al16 | Assists the decision-making process and gives the basic data for running suppliers’ reward projects | |

| Gilson et al22 | Quality has been noted to be a strategic criterion for sourcing vaccines | ||

| Arney et al19 | The purchase of medicines and medical supplies by government facilities, followed by just-in-time (often next-day) delivery from a distribution center directly to the purchasing facility | ||

| Relating essential list of medicines with rappolicy of pharmaceutical procurement | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Implementation of a national medicine policy | |

| Bastani et al1 | Defining a uniform pharmacopeia for all insurance companies | ||

| Methods and incentives (payment method) | Decreasing supply induced demand | Bastani et al1 | Reducing the induced demand of service providers |

| Mehralian and Bastani4 | Paying attention to the nature of pharmaceutical market that has congenital information asymmetries | ||

| Payment mechanisms | Bastani et al1 | Payment system must enhance the efficiency of the health care system, reduce the cost, and lead to quality achievement | |

| Mehralian and Bastani4 | Apply appropriate incentives, especially in a payment system, regulatory mechanisms, and penalties | ||

| Ogbuabor and Onwujekwe20 | Most policy makers and providers stated that unclear procedure and delayed reimbursement procedure constrained provider payment | ||

| Behavioral incentives | Bastani et al6 | This approach is rooted in the treatment-oriented attitude of our insurers whose focus is on reimbursement; if they become more health-oriented and focus on prevention, this problem will resolve by itself | |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Behavioral changes may be stimulated through the use of financial incentives, penalties, or other regulatory measures | ||

| Rules and regulations | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Regulation is a key instrument employed by governments to align the behavior of the players in the pharmaceutical sector with their public policy objectives | |

| Bargaining power | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Bargaining for medicines’ price and quality and setting restrictions on medicine use | |

| Bastani et al6 | Effective contracts with the best and most eligible service providers | ||

| Lawson et al14 and Gilson et al22 | Note the overall objective of supplier selection to be risk reduction in purchasing, maximizing total purchase value, and building long-term relationships between buyers and suppliers and bargaining global sources | ||

| Pharmaceutical circulation funds | Arney et al19 | Budget allocation and integration in the pharmaceutical sector | |

| Price | Pricing methods | Bastani et al3 | Efficiency and cost indexes and effect of exchange rate fluctuations in the total cost of the pharmaceuticals |

| Haupt15 | Biopharmaceutical companies are focusing on operational efficiency more than ever before due to cost pressures, generic competition, complex pricing, regulations, and globalization | ||

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Designing payment mechanisms and control of prices | ||

| Arney et al19 | Under the rubric of centralized management and decentralized purchasing, a variety of federal pricing arrangements, among other mechanisms, help the DOD and VA control medicine costs | ||

| Cost-price structures and affordability of prices | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Increased access to medicines depends on an efficient resource allocation and purchasing system, including rational selection and use of medicines, adequate and sustainable financing, affordable prices, and reliable health care and medicine supply systems | |

| Bastani et al3 | Patient’s ability of cooperation in the payment of the medicine | ||

| Mehralian and Bastani4 | Increasing the affordability of medicines requires that purchases be made at the lowest prices for the same standard quality | ||

| Gilson et al22 | Availability of the supply, associated risks, price, quality, service, delivery, and management compatibility | ||

| Pazirandeh18 | Possible future initiatives could include adopting more stringent criteria for categorizing new medicines as innovative as well as further reductions in the prices of generics | ||

| Competitive prices | Bastani et al3 and Sermet et al17 | Competitive pharmaceutical prices | |

| Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Resource allocation and purchasing (RAP) arrangements may harvest the benefits from competition | ||

| Real prices | Bastani et al3 | Actual pharmaceutical prices | |

| Agreeable prices | Bastani et al3 | Granting the power of negotiation and bargaining to insurance organizations (negotiable prices) | |

| Arney et al19 | VA schedules are essentially catalogs of pharmaceutical products at prices available to all government agencies | ||

| Structure and organization | Hierarchy | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Outsourcing and vertical integration decisions, including their financial, organizational, and strategic effects on the organization |

| Patcharanarumol et al21 | The governance of the purchaser organization, the design of the purchasing arrangements including incentives and use of information, and the institutional capacities to implement purchasing functions are essential for effective strategic purchasing which can improve health system efficiency as a whole | ||

| Priority | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | The health sector reform process in developing countries often entails a combination of measures such as strengthening the district health services and giving autonomous status to major hospitals and public central supply agencies | |

| Levison23 | There is a relationship and priority between the supplier integration, supplier responsiveness, and strategic purchasing | ||

| Decentralization | Preker and Langenbrunner7 | Health services in developing countries are increasingly decentralized, thereby separating stewardship and governance. Decentralization of control over pharmaceutical budgets, however, has been particularly slow | |

| Organizational chart | Haupt15 | It is critical for a company to optimize the sizing of a manufacturing facility to achieve maximum capacity utilization while avoiding or minimizing nonproductive, idle capacity |

As it derives from Table 3, 8 articles (61.54%) pointed to the subcomponents of the main component of “price.” These subcomponents include pricing method, cost-price structures, and affordability of prices, competitive prices, real prices, and agreeable prices.

The second most referred main component belonged to “methods and incentives” with 7 articles (53.85%) and 6 subcomponents, namely, decreasing supply induced demand, payment mechanisms, behavioral incentives, rules and regulations, bargaining power, and pharmaceutical circulation funds.

Discussion

In summary, it seems that 6 categories of components—“target group and service users” (the demand side), “purchased interventions,” “providers and suppliers of interventions” (the supply side), “methods and motivations” (payment terms), “price,” and “structure and organization”—have been effective on the strategic purchase of medicines in different countries. This final categorization was similar to conceptual World Bank framework and another study.

Granting pharmaceutical subsidies to particular population groups and rational use of medicines are considered as the proposed sub-variables in the field of “target group and service users” or “demand-side interventions.” Gilson believes that governments are obliged to subsidize medicines that these subsidies can be used for some target groups as discount or exemption from the payment.22 Other studies also mention that the success of discount project and subsidies subject is dependent on the existence of appropriate financing systems to compensate the lost revenue from the sale of medicines.6 For example, 1 study showed that community-based financing projects increase moral hazard and limit the granting of subsides to the poor people.21 These results emphasize the importance of granting subsides, with attention to some considerations about the way to assign subsidies to medicines, how to choose its appropriate financing method as well as how to select target groups.

Based on the present study, all purchasing structures and resource allocation consider the rational use of medicines to an optimized use of limited resources.7 Different studies have mentioned different forms of irrational use of medicines, including prescribing too much medicines, multi-treatments, excessive intake of antibiotics, misplaced injections, small amount use of effective and appropriate products such as oral rehydration, and use of dangerous medicines.24

Problems caused by the irrational use of medicines increase significantly in the case of oneness of prescribing and dispensing functions in time of economic pressures, information asymmetry, lack of education, poor monitoring and response, increased expectations of the people and sick persons, and motivation of earning more profit.7 It is obvious that irrational use of medicines as an important issue, that can face the demand for medicines with problem, is more pronounced in developing countries facing with economic pressures, stewardship and regulatory challenges, and lack of control levers of inner and outer motivations. Other evidences show that the poor tend to self-medication more than rich people. This tendency reduces the potential benefits arising from the use of medicines, and imposes a macroeconomic burden to the health system and can greatly worsen medicine resistance in the community.25 For this issue, it is necessary to reinforce the rational use of medicines and improve public awareness about the effects of indiscriminate use of medications on the people’s health and the health care system.

Other findings indicated that financing the most effective medicines and selecting the strategic medicines for the poor are considered as the most important sub-variables discussed in “purchased interventions.” In this regard, the evidence from Tanzanian insurance organizations represents the existence of pharmaceutical policy projects for using the selective contracts to purchase generic medicines available on the list of basic medicines of the World Health Organization. The relationship between above principles and payment system to physicians of the countries can lead to choosing the best and the most cost-effective interventions and essential medicines.26

Therefore, it is essential to take steps toward institutionalization of pharmaceutical economic methods in selection of the best, the most effective, and the most affordable medications. In this regard, the implementation of electronic prescribing is suggested to help the physician in prescribing medicines covered by insurance plan and pharmacopeia of the related insurance organization. This technology results in access to information about the insurance coverage at the place of care and creates an instant electronic relationship between physician office, pharmacy, and health insurances.27,28

The sub-variables of “providers and suppliers of interventions” were identified in this research, including choosing the most reliable supplier of pharmaceuticals; choosing the best pharmaceutical provider in the public or private sector; promoting active competition between pharmaceutical drug providers on the quality, price, and volume of medicines; and making the basic medicine list and the rational policy of providing and purchasing medicines.

In this regard, the evidences also emphasize on this point that the selection process of the medicine suppliers is very important, so the active competition between public and private sectors on the price and volume of intended pharmaceuticals, in addition to decrease in prices and increase in the obtained value from money, has a great importance in this context.7

Other findings of this research imply that reducing the induced demand of pharmaceutical providers, payment system, bargaining, cash flow of medicines, behavioral motivations, and monitoring are considered as the most important sub-variables of the methods and incentives (payment method). Various evidences show that the nature of pharmaceutical market combined with inconsistency and combination of relatively competitive retail market and also low competition in the production and wholesale are associated with the risk of severe induced demand by the service providers.7

In addition, the various studies showed that behavioral changes have been known as an effective component for strategic purchasing that is possible through using financial incentives, penalties, and regulatory affairs and modifying the payment system in this market.29 All these studies emphasize on the necessity of creating a proper competition in pharmaceutical market to reduce market failures and to achieve the competitive price. The importance of the payment term is as far as some evidences indicating the impact and the positive correlation of payment system to physicians with dose of drugs. This issue in the countries like Korea, where physicians combined prescribing and distribution rules, is intensified.8

In this regard, evidence shows that 3 general payment methods to providers cause the creation of different motivations for prescribing medicines. For example, “budget” method of payment allocates the medicines budget in a linear or allocated form to medicines and other consuming products. In fact, budget payment is a form of credit allocation to the medicines depends on conditions.

In addition, “fee for service” is the base of private insurances and individual purchase. This method could increase the number of services and medicines consumption.

Regarding the “per capita” method which is not so common in the developing countries, people seek treatment sooner and therefore need less medications. However, under prescription would be occurred to reduce the medicine expenditures and increase the remained fund for the health professionals in this method.

The other studies show that in addition to the payment methods, cash flow is also effective on the prescription and consumption of medicines. For example, in India, patient pays the medicine cost directly to the pharmacy and then follows to return all or a part of his money from the buyer organization, whereas in Tanzania, the buyer organization pays directly to the provider.8 These differences can be followed by different motivations; for example, it could lead to corruptions, forging, and overreporting by the providers to receive more fund from the buyer organization.

Finally, the results indicated that medicines pricing methods, cost-price structure, and competitive, real, and negotiated prices are known as the most important sub-variables of price.

In this regard, the evidence shows that the increased ability to purchase medicines needs medicines purchased with the lowest price and the standard quality. To achieve this goal, there is no way only to use the competition benefits, replacing brand medicines with the generic ones and achieving the agreed prices.7 For example, in the Philippines, favorable price of basic medicines is obtained by negotiation with local producers,30 or in Tanzania, only the distributor of medicines can adjust medical bills based on the price list of generic medicines.8

On the other hand, evidence indicates that the price can be adjusted as the real cost (total amount), total amount plus percentage or fixed rate, and/or a fixed rate, for example, per prescription or per item that in case of using each item, we will face different options of behavioral requirements.31

In addition, evidence of various countries indicates that the lack of guidelines for price and the lack of a control mechanism, even in case of the proper use of medicines pricing, can lead to a lot of variations in the amount received from the buyers.3,32 So, attention to price adjustment strategies, reforming the pricing mechanisms, and control of price volatility to achieve competitive, agreed, payable, and real prices will help as an important underpin to perform strategic purchasing.

Finally, the present results showed that hierarchy, priorities, organizational structure (decentralization), and organizational chart are proposed as the most important sub-variables of “structure and organization” in the strategic purchase of medicines.

In this regard, it was said that the organizational structures are the frameworks where purchasing and allocation of pharmaceutical resources are done, so efficacy of purchasing and allocating of resources depends on the characteristics and responsibilities for decision making and the level of risk.7 In other words, many governments in developing countries have approved the national pharmaceuticals rules and policies to ensure the efficacy, safety, and rational use with a comprehensive approach, and this issue includes competitive bidding, management control, distribution strategy, educational activities for rational use of medicines, licensing, and other regulatory requirements.23 Creation of decentralized structures in the purchase of medicines was another item which is pointed in developing countries in terms of organizational structure and its effectiveness in the purchase of medicines.7

This article was conducted by a protocol reviewed by a research team with expertise in reviews. To ensure a broad search of the literature, the search strategy included 8 electronic databases. Each article was reviewed by 2 independent reviewers. We did not contact any researchers or experts for additional information we may have missed. Scoping reviews are not intended to assess the quality of the literature analyzed. Thus, the conclusions of this review are based on the existence of studies rather than their intrinsic quality. Nevertheless, this scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of the existing research on the pharmaceutical strategic purchasing. Due to the diversity of studies in different countries, the accurate comparison would be very complicated. For concentrating on the objective of the study and preventing diversity, the keywords were limited by expert opinions. So it could be mentioned as a limitation of study. Another limitation is lack of research study on pharmaceutical purchasing in the underdeveloped countries. The current scoping review provides foundations for further discourse and research on components related to the effects of pharmaceutical strategic purchasing on the health care system. Finally, it is proposed that more scientific research on the impact of pharmaceutical purchasing strategy on health and health care should be performed especially in underdeveloped countries in the near future.

Conclusions

According to the results, it seems that the insurance organizations affiliated with the developing countries can achieve the strategic purchase only through the modification of the medicine pricing system, modification of payment systems, attention to the real needs of target groups (demand) and modifying the structure and organization, as well as attention to the purchase of the most effective medicines from the best pharmaceutical providers.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

A draft chart of data extraction.

| General Information | |

|---|---|

| Title of the manuscript | |

| Article No | Language |

| Year of the publication | First author |

| Place (Country) | Corresponding |

| Type of article | Journal name |

| Article Characteristics | |

| Aims of the study | |

| Study approach | Study design |

| Methodology | |

| Sampling Method | Study Environment |

| Data collection | Study Population |

| Data Analysis | Sample Size |

| Results | |

| Main results | |

| Conclusion | |

| Recommendations | |

| Limitations | |

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: PB- Design of the study, reviewing the literature, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript. AG- Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article. SV- Drafting of the manuscript, acquisition of data. MS- Developing the search strategy, acquisition of data, participate in design of study, drafting of the manuscript, final revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Bastani P, Mehralian G, Dinarvand R. Resource allocation and purchasing arrangements to improve accessibility of medicines: evidence from Iran. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abachizade K, Bastani P, Abolhalaj M. A comprehensive analysis of drug system money map in Islamic Republic of Iran. J Econ Sustain Dev. 2013;4:158–164. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bastani P, Dinarvand R, SamadBeik M, Pourmohammadi K. Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing requirements in Iran: price interventions and the related effective factors. J Res Pharm Pract. 2016;5:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehralian G, Bastani P. Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing: a key to improve access to medicines. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14:345. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abolhalaj M, Bastani P, Ramezanian M, Tamizkar N. Production and consumption financial process of drugs in Iranian healthcare market. Dev Ctry Stud. 2013;3:187–191. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bastani P, Doshmangir L, Samadbeik M, Dinarvand R. Requirements and incentives for implementation of pharmaceutical strategic purchasing in Iranian health system: a qualitative study. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;9:163. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Preker AS, Langenbrunner J. Spending Wisely: Buying Health Services for the Poor. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumaranayake L, Mujinja P, Hongoro C, Mpembeni R. How do countries regulate the health sector? evidence from Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bastani P, Samadbeik M, Kazemifard Y. Components that affect the implementation of health services’ strategic purchasing: a comprehensive review of the literature. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Thammatacharee J, Jongudomsuk P, Sirilak S. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2014;30:1152–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, ed. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers Manual 2015. Adelaide, SA, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collins A, Coughlin D, Miller J, Kirk S. The Production of Quick Scoping Reviews and Rapid Evidence Assessments: A How to Guide (Beta version 2). London: Joint Water Evidence Group A, Defra; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nadelson S, Nadelson LS. Evidence-based practice article reviews using CASP tools: a method for teaching EBP. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11:344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawson B, Cousins PD, Handfield RB, Petersen KJ. Strategic purchasing, supply management practices and buyer performance improvement: an empirical study of UK manufacturing organisations. Int J Prod Res. 2009;47:2649–2667. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haupt LF. Vertical Integration and Strategic Sourcing in the Biopharmaceutical Industry. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirytopoulos K, Leopoulos V, Voulgaridou D. Supplier selection in pharmaceutical industry: an analytic network process approach. Benchmarking. 2008;15:494–516. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sermet C, Andrieu V, Godman B, Van Ganse E, Haycox A, Reynier JP. Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8:7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pazirandeh A. Sourcing in global health supply chains for developing countries: literature review and a decision making framework. Int J Phys Distr Log. 2011;41:364–384. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arney L, Yadav P, Miller R, Wilkerson T. Strategic contracting practices to improve procurement of health commodities. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2:295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogbuabor DC, Onwujekwe OE. Scaling-up strategic purchasing: analysis of health system governance imperatives for strategic purchasing in a free maternal and child healthcare programme in Enugu State, Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patcharanarumol W, Panichkriangkrai W, Sommanuttaweechai A, Hanson K, Wanwong Y, Tangcharoensathien V. Strategic purchasing and health system efficiency: a comparison of two financing schemes in Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilson L, Kalyalya D, Kuchler F, Lake S, Oranga H, Ouendo M. Strategies for promoting equity: experience with community financing in three African countries. Health Policy. 2001;58:37–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levison L. Policy and programming options for reducing the procurement costs of essential medicines in developing countries. Concentration Paper. Boston, MA: Department of International Health, Boston University School of Public Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bitrán R, Giedion U. Waivers and exemptions for health services in developing countries. Final Draft. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Atim C. Contribution of Mutual Health Organizations to Financing, Delivery, and Access to Health Care. Synthesis of Research in Nine West and Central African Countries. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al Serouri AW, Balabanova D, Al Hibshi S. Cost Sharing for Primary Health Care: Lessons from Yemen. Oxford: Oxfam; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmadi M, Samadbeik M, Sadoughi F. Modeling of outpatient prescribing process in Iran: a gateway toward electronic prescribing system. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samadbeik M, Ahmadi M, Hosseini Asanjan SM. A theoretical approach to electronic prescription system: lesson learned from literature review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:e8436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinson JC. Value-based purchasing for medical devices. Health Affairs. 2008;27:1523–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneider P, Diop FP, Bucyana S. Development and Implementation of Prepayment Schemes in Rwanda: Partnerships for Health Reform. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Homedes N, Ugalde A. Improving the use of pharmaceuticals through patient and community level interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:99–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bennett S, Creese AL, Monasch R. Health Insurance Schemes for People Outside Formal Sector Employment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]